Abstract

This study demonstrates that nature play meaningfully supports children’s well-being, engagement, sense of belonging, and connection to nature. Over 10 weeks, Year One students (n = 25) from a metropolitan government school in Sydney Australia, participated in a Bush School program, experiencing it as a space of joy, calm, challenge, and growth. Children came to see Bush School not as a break from learning but as a different kind of learning: active, relational, and purposeful. Using a quasi-experiment mixed-methods design, including reflective journals, self-report tools, and class assessments, the study found no negative impact on reading or mathematics outcomes, addressing concerns about lost instructional time. Instead, nature play enhanced number and algebra development, self-regulation, collaboration, and motivation to learn. The findings from this study highlight the potential of nature play to complement formal education in a developmentally appropriate way. Moreover, embedding nature play into mainstream schooling provides a timely and relevant response to current challenges facing education. The study also highlights the importance of listening to children as capable meaning-makers with valuable perspectives. In an era of growing pressure on children and schools, nature play invites a shift in mindset; to slow down, trust children, and embrace the natural world as a co-teacher.

Keywords:

nature play; primary education; well-being; engagement; belonging; mathematics; student voice 1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Study Aims

Across the globe, schools are under growing pressure as traditional education models struggle to meet the rising needs of students. Concerns about student well-being and engagement are mounting, with rising reports of anxiety, school refusal, social disconnection, and disengagement from learning (; ; ). Australian primary students mirror these trends, citing social anxiety, difficulties forming peer relationships, problematic screen use, and academic stress (). Academic disengagement is also worsening, as demonstrated by widening achievement gaps. One in three students now fails to meet minimum standards in mathematics and literacy (; ), with these gaps most pronounced for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, those in rural or remote areas, and those experiencing socio-economic disadvantage (). Early vulnerabilities across physical, social, and emotional domains compound these challenges (), often leading to long-term impacts if not addressed (; ; ). Despite this, research and interventions frequently target these domains in isolation, neglecting the interrelated nature of well-being, engagement, and learning in children’s everyday lives. Together, these overlapping concerns are prompting renewed calls for proactive school-based intervention (). The cost of late intervention in Australia has been estimated at AUD 15.2 billion per year, underscoring the urgency of preventative, early approaches that support children’s holistic development ().

At the same time, broader socio-cultural shifts are reshaping childhood itself. ’s () hurried child remains relevant, as structured routines, performance pressure, and diminished playtime accelerate developmental timelines. These shifts appear to be associated with rising levels of childhood anxiety and social-emotional challenges (; ). A key concern is the decline in outdoor play and increasing disconnection from nature. This is driven by factors such as urbanization, safety concerns, reduced access to nature, and screen time (; ; ; ; ; ; ). In a national survey of 618 Australian children aged 8–12, 50% reported being restricted from outdoor play altogether (), reflecting a broader shift toward structured, sedentary, and screen-dominated childhoods (; ; ).

These patterns are mirrored in schools, where early formal instruction and increasing academic demands frequently displace developmentally appropriate play (; ; ). Furthermore, the pressure to meet performance and policy targets places strain on teacher–student relationships, which are crucial to both well-being and learning, while also limiting the capacity for play-based, child-responsive pedagogy (). Post-COVID-19 responses have intensified these dynamics. They prioritize teacher-led instruction and academic catch-up (), despite promising evidence supporting more flexible, slower approaches trialed during lockdowns (). As a result, schools are being described as sites of “systemic play deprivation” (). This is particularly notable in the Australian context, where outdoor learning remains underutilized in primary schools despite its recognized developmental value ().

Together, these challenges point to the need for integrated, developmentally appropriate, and outdoor nature play approaches that support children’s holistic development. While the benefits of nature-based learning are increasingly recognized, few studies have examined its role in the early years of formal schooling. Nor have many explored how it supports holistic development and learning in an integrated way. Fewer still draw on children’s own perspectives to understand these outcomes, limiting our understanding of how nature play is experienced and its benefits from their point of view.

In response to these intersecting challenges, this study aimed to investigate how nature play might support children’s holistic development. It draws on data from a structured 10-week nature play intervention (Bush School) with Year One students (N = 50) attending a metropolitan government school in Sydney, Australia. The intervention consisted of two-hour weekly sessions in a natural outdoor setting. The broader project employed a quasi-experiment mixed-methods design with a waitlist control group (n = 25). This paper focuses on the intervention group’s experience (n = 25), using both qualitative and quantitative data to explore children’s perspectives and outcomes. This approach allows for convergence and complementarity between the two strands (). The research was guided by two questions:

- What effect does a 10-week nature play intervention have on Year One students’ academic performance, well-being, school engagement, and connection to nature?

- What do children say about nature play and its impact on their lives?

This paper presents an in-depth exploration of the intervention group’s lived experience and outcomes through a child-centered, mixed-methods approach, integrating data from children, parents, and teachers alongside quantitative self-reports. Although the broader study included a waitlist control group enabling comparative analysis, these results are reported in a separate manuscript currently under review. Consequently, this paper emphasizes a rich, contextualized understanding of how participants directly involved in the nature play intervention perceive and experience its impact. These insights complement those derived from statistical group comparisons.

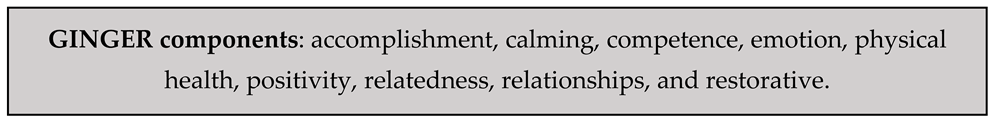

Importantly, the study was conducted in a school already implementing a play-based learning (PBL) program, Walker Learning. This Australian program combines play, project-based learning, and explicit instruction (). This provided a unique opportunity to investigate the added value of nature play beyond established PBL approaches. Findings are presented through the GINGER model, a child-centered nature-inclusive framework describing primary students’ holistic development across four domains: well-being, engagement, sense of belonging, and nature pedagogies.

1.2. Why Nature Play Matters Now

Amid these growing pressures on childhood and schooling, this section considers the unique role of nature play. While play in schools is well established as a cornerstone of development supporting social, emotional, physical, cognitive, and creative growth (), nature play offers additional, distinct benefits. Nature play refers to unstructured, outdoor experiences where children interact with natural elements, such as mud, sticks, water, and trees (). It combines the developmental advantages of play with the restorative, embodied, and sensory affordances of the natural world. Although not a new concept, nature play is newly important in an era of disconnection from the natural world, intensified academic pressures, and diminished opportunities for outdoor experiences (). Its potential to support learning and well-being in an integrated—rather than compartmentalized—way is especially relevant, given the increasing complexity of children’s needs.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have long practiced place-based, experiential learning on Country (), and Western theorists such as Rousseau, Fröebel, and McMillan saw nature as central to learning, supporting freedom, curiosity, moral development, and socialization (). Contemporary research reinforces its relevance. Nature play has been linked to improved resilience, creativity, physical, social, and emotional development, positive mental health, academic performance, and environmental stewardship (; ; ; , ; ; ; ; ). Children themselves describe nature play as joyful, calming, and energizing (), qualities that support well-being, intrinsic motivation, and readiness to learn. Despite growing evidence of its benefits, the aforementioned outdoor learning remains underrepresented in Australian primary schools (). Additionally, research involving younger children, particularly those under eight, who are in the early years of formal schooling, is limited (). This is significant given that early experiences are foundational to lifelong development.

Yet, as previously noted, access to nature play is declining, particularly in urban settings, due to safety concerns, loss of green space, and increasing adult supervision of children’s lives (; ). Schools are uniquely positioned to help reverse this trend. Countries like Finland, Scotland, and Wales have embedded nature play into education policy with positive outcomes for learning and well-being (; ). In contrast, Australian uptake remains limited, despite strong community support and a growing body of evidence (; ; ), despite community support (; ; ; ). This gap between evidence and practice represents a missed opportunity, particularly in a system characterized by long instructional hours () that could be balanced with nature-based approaches to support holistic development.

1.3. Children as Active Meaning-Makers

Building on the rationale for nature play, this study shifts focus to the voices of those most affected, children themselves. Grounded in a participatory, rights-based framework, it adopts a mixed-methods, child-centered design that positions children not merely as participants, but as active meaning-makers whose perspectives are crucial for understanding and informing issues that affect their lives (). This approach reflects broader international commitments to children’s rights, most notably Article 12 of the () Convention on the Rights of the Child United Nations, which upholds children’s rights to express views on matters affecting them ().

Including children in shaping the programs and policies that affect them is increasingly recognized as both just and necessary (; ). Yet, educational research remains dominated by adult perspectives, often treating children as passive subjects (), and marginalizing their views (; ). This is despite evidence that children are willing and capable of contributing meaningfully; adults simply need to listen and respond (). To support this shift in perspective, the study’s methods were designed to reduce adult-child power imbalances (), acknowledging that such imbalances could never be entirely eliminated. Children were offered multiple modes of expression, including a self-report questionnaire, journals (that could include drawings and photographs), informal conversations, and embodied action. While this approach did not replicate ’ () Mosaic approach, it shared their core belief in children’s competence to interpret and express their experiences.

These methods align with growing calls for more authentic child-centered research that captures children’s perspectives on outdoor experiences (). This matters for two reasons. First, children offer unique insights that adults may overlook, helping to “explain, describe, illustrate and enlighten” () nature play in ways adult observations alone cannot, thereby enriching the analysis. As () explain, “viewing these experiences through their eyes draws attention to the details that play an important role in driving their curiosity and potential to develop a love of learning” (p. 375). Second, as the primary beneficiaries of nature play, children’s voices are essential to shaping practices that truly support their holistic development.

1.4. The GINGER Model: Understanding Children’s Holistic Development in Nature Play

To help analyze the findings, this study introduces the GINGER model (Growth, Identity, Nurturing nature, Genuine connection, Experientia, and Reciprocity), a holistic lens for understanding primary school students’ experiences of nature play. The model is grounded in the principle that well-being, engagement, belonging, and nature connectedness are not discrete outcomes, but interwoven throughlines that manifest in children’s everyday interactions, emotions, and behaviors. Developed specifically for this study, the GINGER model offers a novel lens through which to interpret children’s narratives and observable behaviors in nature-based settings. Existing frameworks describe components of nature-based learning (for example, well-being, connection to nature), but they often treat these outcomes in isolation. GINGER, by contrast, offers an integrated, child-centered structure that captures the complex interplay of developmental, relational, and ecological factors.

The GINGER model can be positioned alongside holistic education frameworks such as the Australian positive education PROSPER model (). PROSPER represents pathways supporting well-being: positivity, relationships, outcomes, strengths, purpose, engagement, and resilience. While there is some conceptual overlap with GINGER, PROSPER does not explicitly address the role of nature or ecological connection. Meanwhile, outdoor learning research in primary education has primarily focused on building an evidence base to support its inclusion into mainstream schools rather than offering an integrated development framework. GINGER addresses this gap by uniting well-being, engagement, learning, ecological connection, and experiential education within a single, integrated model. In doing so, it extends current approaches in positive education and outdoor learning. The model integrates well-being, engagement, learning, and sense of belonging through a developmental, child-centered, ecological lens while incorporating nature pedagogies. An account of the model’s multi-stage development, including its theoretical grounding, empirical validation, and cultural consultation with an Aboriginal Elder, is currently under review.

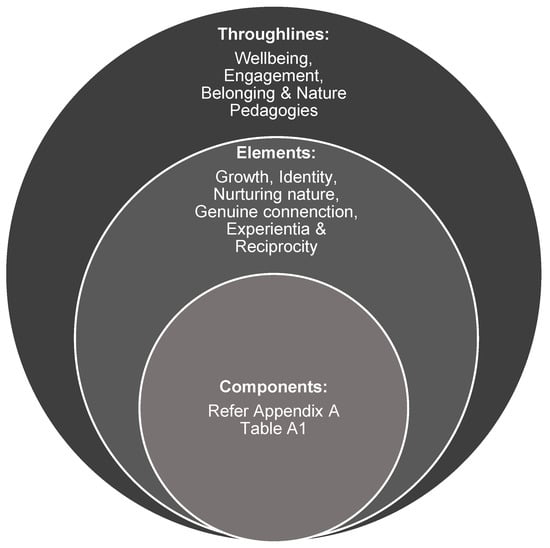

Organized into three nested levels (Figure 1), the GINGER model comprises: (1) broad developmental domains (throughlines), (2) six elements (the GINGER acronym), and (3) observable components used to guide the analysis (see Appendix A, Table A1). Each element is briefly defined as follows:

Figure 1.

The nested levels of the GINGER model: throughlines, elements, and components.

- Growth: Conditions that foster progress in learning, development, and physical health.

- Identity: Personal characteristics, beliefs, and values shaping children’s experiences.

- Nurturing Nature: The sensory and emotional support offered by natural environments.

- Genuine Connection: Relationships with peers, educators, family, and place.

- Experientia: Derived from the Latin for “knowledge gained through practice and repeated trials” (). In GINGER, it refers to the learning through child-led, unstructured, and embodied play in nature.

- Reciprocity: Mutual respect and care between humans and the more-than-human world.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The study prioritized children in a mainstream primary education setting who are often underrepresented in research (). It employed a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive understanding of children’s experiences with nature play. This systematic data collection addressed common limitations in nature play research, including reliance on qualitative data with children under 12, unclear intervention dosage, and replicability issues (; ; ). It also used a developmentally appropriate, self-report instrument specifically developed for this project ().

To ensure methodological rigor and conceptual clarity, research questions, data collection methods, and the GINGER model were aligned through a structured mapping process (see Appendix A, Table A2). A coding matrix was used to connect each research question with its objective, appropriate data sources, and relevant GINGER elements and components. Methodological choices were refined through iterative review to ensure data sources could speak to the theoretical dimensions of GINGER without limiting their inductive potential for analysis. For example, children’s journals were selected for their capacity to reflect elements such as identity and genuine connections, while still allowing for emergent themes grounded in children’s lived experiences.

2.2. Participants

Fifty Year One students (mean age 6.87 years; SD = 0.34) attending a metropolitan government primary school in Sydney, Australia, participated in the study. Although participants were drawn from three Year One classrooms, these classrooms contributed students to both the intervention and control groups, albeit not in equal proportions. To account for this imbalance and potential classroom-level effects, the classroom was included as a fixed effect in statistical analyses. Group placement was assigned on a first-come, first-served basis across three cross-class groups.

Twenty-five students were assigned to the intervention group (13 boys, 12 girls) and 25 to a waitlist control group (8 boys, 17 girls). Eligibility required completion of Kindergarten (first year of school) at the participating school. Recruitment was via self-nomination, aiming for gender balance and inclusion of children with identified needs. Four teachers (two classroom, two Bush School educators) and parents of intervention children (n = 25) also participated. The school’s family occupation and education index (FOEI) was ≤3, indicating predominantly high socio-economic status and lower student need relative to the state average (). The school did not have a nature-based education program, and its playground was mostly hard surfaces. That said, some natural features were present, including large rocks for sitting and trees, but these were not typically part of children’s active play. For the purposes of this article, analysis is limited to the intervention group, as explained in the introduction.

Although the school is situated in a metropolitan area, parent demographic data indicated that 88% of children in the intervention group lived near a natural setting. Reported types of nearby nature included the beach/ocean (41%), bushland (31%), and parks (28%). Most children were reported to visit natural environments regularly, with 69% doing so once a week and 12% daily. Common nature-based activities included swimming (33%), bushwalking (26%), and climbing (14%). These contextual features suggest that, while many children had routine access to outdoor environments outside of school, the intervention provided a novel opportunity for nature play within the school context.

The intervention group was largely homogeneous in cultural and linguistic background. No participants identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. Sixty percent of children were identified as solely Australian, while the remaining 40% reported multiple national affiliations, including Australian/European (16%), and smaller proportions identifying as Australian/Asian, Australian/North American, Australian/Asian/European, Asian, North American, and European (each 4%). English was the most commonly spoken language (83%), followed by Russian (7%), Cantonese (4%), Spanish (3%), and Greek (3%). While this reflects some cultural variation, the intervention group overall represented a relatively cohesive, high socio-economic demographic, providing insights into how nature play may be experienced in a mainstream urban primary education setting.

2.3. Intervention

The Bush School intervention involved ten weekly, two-hour sessions off-site during Term 2 of 2024 (end April to early July). Each Thursday, children travelled by bus from school before the school day and returned by recess. Sessions combined child-led, unstructured nature play with structured elements such as storytelling, songs, bushcraft activities, and bushwalks. While flexible to children’s interests, sessions generally followed a consistent format: (1) opening circle with Acknowledgement of Country (10 min); (2) unstructured nature play, where children explored natural play areas such as a climbing tree, chalk/ochre rocks, mud kitchen, balancing plank and logs, cubby building, bug hunting, and general free play (45 min); (3) bushwalk and/or storytelling around a symbolic campfire (20 min); (4) optional bush craft or extended play (35 min); and (5) closing circle for reflection and gratitude (10 min).

2.4. Ethics and Consent

Ethical approval was granted by Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (ID number, H15600 and the New South Wales Department of Education (State Education Research and Partnerships (SERAP), reference number, 2021431)). Teachers and parents provided written consent to participate in the study. Parents also provided written consent for their child’s participation, while children gave written consent and ongoing assent. All participants could withdraw at any time. Participant confidentiality was maintained through the use of pseudonyms.

2.5. Measures

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected at multiple time points to comprehensively capture children’s experiences (see Table 1 for a detailed overview). Children’s self-reported experiences of nature play were assessed via the Play, Nature, Engagement, and Well-being—Bush School (PNEW–B) questionnaire, an expanded version of the original Play, Nature, Engagement and Well-being (PNEW) instrument (see Appendix B, Table A3). Both used a three-point Likert scale (never, some of the time, all the time), allowing children to respond independently. The PNEW was administered to intervention and control groups at baseline, post-intervention, and at 4-month follow-up, while the PNEW–B was used exclusively with the intervention group post-intervention and follow-up. Academic data were collected through routine school assessments, administered and shared by teachers.

Table 1.

Data collection.

Children documented their Bush School experiences through journals, including reflections, drawings, and photographs. The lead researcher recorded informal conversations and detailed observations during sessions, supported by photographs for context. Teacher perspectives were collected through semi-structured interviews and reflective journals. Bush School educators agreed to write a reflective journal. Unfortunately, one was lost it, so it was not included in the analysis. Another Bush School educator later provided a retrospective written reflection, which was included. Parents completed online surveys both before and after the program, comprising closed and open-ended questions about the intervention’s impact. These qualitative data sources were integrated during analysis to triangulate findings and deepen understanding of children’s nature play experiences.

2.6. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized PNEW and PNEW–B questionnaire responses. Longitudinal PNEW items were analyzed using mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression with fixed effects for gender, classroom, and time, and a random effect for participants. Although only data from the intervention group are reported, the classroom was included as a fixed effect to account for the nested structure of students within three different Year One classrooms. Post-intervention and follow-up PNEW–B responses were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with mean differences, 95% confidence intervals in the change in item and gender (follow-up—immediate). Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 30), with data complete at all time points.

Qualitative data analysis was conducted in two phases. First, inductive thematic analysis () using NVivo (Version 14.23.4) was applied to children’s journals, researcher field notes, and teacher interviews to foreground participant voices and identify themes grounded in lived experience. Parent surveys were analyzed using framework analysis (), with open coding supplemented by structured survey categories. In the second phase, all qualitative data were deductively coded using the GINGER model. Themes falling outside the model were retained to preserve authenticity and richness. Quantitative and qualitative findings were integrated using spiral analysis (), enabling iterative synthesis across data strands. Children’s perspectives remained central, while adult data were used to contextualize and enrich interpretations. A joint display was developed to map these findings against the GINGER model.

2.7. Data Management and Confidentiality

Data were securely managed following institutional and ethical protocols. Quantitative data were initially managed in REDCap (Version 15.0.33), de-identified, and subsequently transferred to a secure university server for long-term storage. REDCap entries were deleted thereafter. Qualitative data (scanned journals, interview transcripts, and open-ended survey responses) were anonymized and stored securely on the same server. Photographic and audio data were deleted from recording devices following upload. All participants were assigned pseudonyms, and withdrawal rights were upheld throughout.

3. Results

This section presents findings related to addressing the study’s research questions: the effects of the 10-week nature play intervention on Year One students’ academic performance, well-being, school engagement, and connection to nature, as well as children’s perspectives on nature play and its impact. Drawing on a mixed-methods approach, the analysis integrates quantitative data (Likert scale responses, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, with gender-specific mean differences; see Appendix C, Table A4 and Table A5) and qualitative insights (student, teacher, parent, and researcher observations). Findings are organized using the GINGER model, which encompasses well-being, school engagement, sense of belonging, and nature pedagogies. While a sense of belonging and nature pedagogies were not explicitly outlined in the research questions, they emerged as salient dimensions shaping students’ lived experiences. Each section identifies relevant GINGER components to frame the results.

3.1. Academic Performance

Quantitative results showed a significant improvement in mathematics results following the intervention, while reading scores showed modest, non-significant gains (see Table 2). Between-group comparisons using Mann–Whitney U tests revealed no significant difference in reading scores between intervention and control groups (U = 315.00, p = 0.960), suggesting that reading improvements may reflect maturation or other external factors. However, a significant difference was found in mathematics scores, favoring the intervention group (U = 225.00, p = 0.005, r = 0.28), indicating the Bush School intervention contributed to mathematical learning gains beyond maturation effects.

Table 2.

Reading and mathematics Wilcoxon signed-rank test scores for the intervention group.

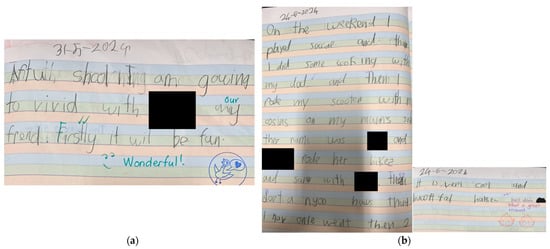

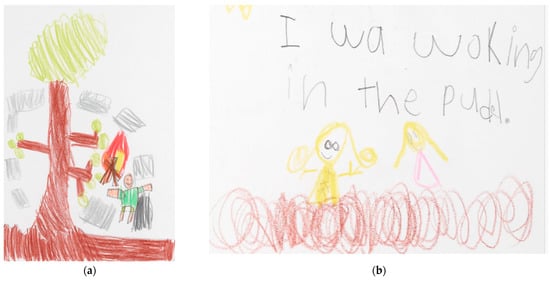

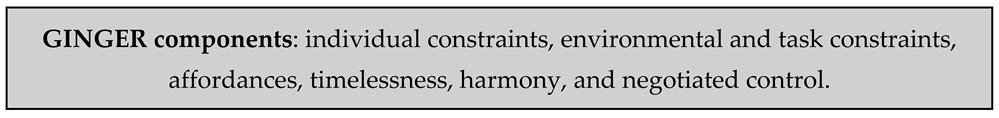

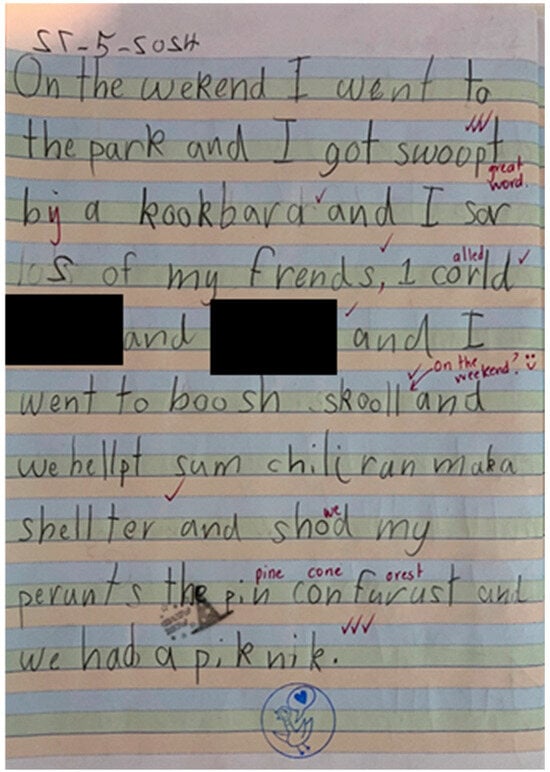

Writing outcomes were not a formal focus of the intervention and were not systematically assessed, making it difficult to draw conclusions about causal impact. However, teacher-reported observations during the intervention period suggested that some students showed noticeable changes in writing. One teacher commented, for instance, that a student who “will not do writing, but wrote in his journal about his morning at Bush School.” Another student was observed writing at greater length and with more detail than before participating in Bush School (see Figure 2). While these examples cannot be attributed definitively to the intervention and may partly reflect individual variation or developmental progression, they were significant enough to be spontaneously noted by teachers. Importantly, no slippage in core academic areas (reading, writing, and mathematics) was reported by the teachers during the study. As one teacher reflected, “Leaving for those couple of hours per week and not having… traditional teaching time. They certainly were still learning.”

Figure 2.

Writing development from one child. (a) Writing sample from 31 May 2024; (b) Writing sample from 24 June 2024.

Student data shed light on these findings. First, children wrote and drew kinesthetic activities associated with mathematical understanding: “At Bush School, I went on a measuring thing and it went up and it went down” (see Figure 3). Teachers reinforced the idea of embodied learning: “They used their bodies as the weight and they soon worked out that they needed to move themselves to make the log balance.” Second, students recognized purpose in Bush School experiences. Agreement with “Bush School is important as it helps me learn” all the time increased from 64% post-intervention to 76% at follow-up. Girls showed a significant increase (MD = 0.62, p = 0.024, 95% CI [0.28, 0.97]), while boys’ ratings remained stable.

Figure 3.

Excerpt from a student Bush School journal showing balancing on the balance log.

3.2. Well-Being

Students expressed accomplishment and competence through self-directed discovery: “I made a cubby.” “I found a water spider.” “I got to the balancing log and I balanced it!” These achievements were often accompanied by persistence and mastery, even after setbacks: “I jumped on rocks. I slipped on the last one. It hurt”. Teachers highlighted students’ perseverance: “On the sixth [try] he did it and was so proud.” Bush School also prompted physical well-being through climbing, jumping, and balancing: “I played in the climbing tree really high branch and I jumped off it.”

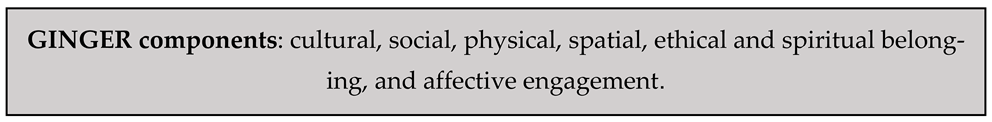

Students also expressed a deep emotional connection to Bush School, including joy and meaning in their journals: “I love Bush School so much.” “Playing on nature. It gave me a good feeling.” “Bush School reminds me of my grannie’s farm,” and drawings (see Figure 4). Adults reinforced this: “I have never seen a child so happy,” “It’s my child’s favorite day.” Quantitative data further confirmed these insights. “Being at Bush School makes me happy” all the time remained high (84% post-intervention, 80% at follow-up; MD = −0.04, p = 1.000). “I like playing in nature at Bush School” all the time rose from 68% to 88%, with increases for boys (MD = 0.45, 95% CI [0.11, 0.79]) and girls (MD = 0.54, 95% CI [0.23, 0.84]). Conversely, “Being at school makes me happy” dropped from 56% to 48% post-intervention, then rebounded to 80% at follow-up (MD = 0.36, p = 0.033), with a stronger effect for girls (MD = 0.54, 95% CI [0.03 to 1.04]).

Figure 4.

Excerpts from student Bush School journals depicting happiness. (a) Happy in the meeting area; (b) Happy in mud. Note: Text reads “I was walking in the puddle”.

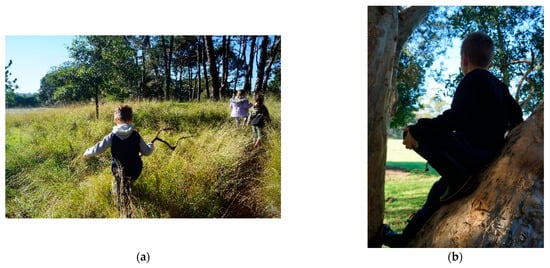

Bush School was also described as calming and restorative. Students confirmed: “All kids should go to Bush School because it makes you feel happy and helps you concentrate better in class,” and “I breathe the air, and it makes me feel calm.” One student reflected, “Nature gives you a break from technology. Nature helps your brain, and technology ruins your brain,” while another added, “You need a mix of technology and nature.” Parents described their children were “more settled” and “content to explore and be present.” While teachers reported that the natural environment “resets the kids’ body clock… so they are ready to learn and ready to engage,” contrasting with “the manic sort of anxiousness… that you see sometimes at school.” Photos from Bush School showing this emotional state (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(a,b) Students calmly exploring nature.

Students spoke of relatedness and relationships, often through shared play: “Bush School helps you make friends because you do more playing than you do at school, and you get to meet other kids not in your class,” and “Building shelters helped us make friends because you had to work together.” Some found the environment more socially inclusive and safer: “A bigger space.” “Not too many people.” “The mean people didn’t go to Bush School.” Others preferred the school’s larger social pool: “There are more children at school so more children to choose to play with.” Girls reported a temporary decline in “I have lots of friends at school” post-intervention (MD = −0.52, 95% CI [−0.97, −0.08]), rebounding at follow-up (MD = 0.52, 95% CI [0.10, 0.93]).

3.3. School Engagement

Students demonstrated agentic engagement through self-directed activity and problem-solving: “I built a base. First we got sticks. Then we crossed them together. Next we put the leaf on. After that we put mud on.” Teachers and parents confirmed increased interest and independence: “The students are more engaged in what they’re doing.” “My child is more engaged/interested in school on Bush School day.” “They know what to do with very little adult intervention.”

Teachers described marked improvements in behavioral engagement: “At school he will not sit down and listen… At Bush School he always sat when he was supposed to, always came back to the group when called, was 100% engaged…the change over the 10 weeks, it’s been massive.” Parents echoed this: “She has difficulty focusing when having to do lessons sitting down so this was a welcome change.” These perceptions of improved focus and engagement were partially supported by quantitative data. For example, responses to the item “I find it easier to concentrate in class after being at Bush School” showed no significant overall change from post-intervention to follow-up (MD = −0.16, p = 0.480). However, a gender pattern emerged: boys showed a greater decline (MD = −0.54, 95% CI [–1.15, 0.06]) compared to girls (MD = 0.10, 95% CI [−0.44, 0.65]), with a marginal gender difference (p = 0.060). A similar pattern was observed in responses to “I find it easier to try my best after recess.” Although there was no significant group-level change from pre- to post-intervention (MD = −0.12, p = 0.541) or from post to follow-up (MD = 0.08, p = 0.807), a significant gender difference was found in the pre-post period (p = 0.033). Girls reported a small, non-significant improvement (MD = 0.24, 95% CI [−0.34, 0.82]), while boys showed a greater, though also non-significant, decline (MD = −0.54, 95% CI [–1.18, 0.11]).

Bush School also supported autonomy: “I like Bush School because you get to climb in the climbing tree.” Students described nature as responsive: “Trees grow branches which are just right for us to lie in or climb.” However, quantitative data revealed a slight decline in perceived autonomy (“I feel free to choose what activities I do at Bush School”) at follow-up (MD = −0.36, p = 0.020), particularly for girls (MD = −0.46, 95% CI [−0.83, −0.08]). Descriptive data, adding nuance with “I feel free to choose what activities I do at Bush School” all the time dropped from 76% to 44%, while those choosing some of the time rose from 24% to 52%. A similar pattern appeared at school: the proportion selecting “I feel free to choose what activities I do at school” all the time fell from 40% to 0%, while never increased from 12% to 24%. Yet, agreement with “I do things at school because I have to, not because I want to” remained stable, suggesting children may have developed a more nuanced understanding of agency rather than experiencing a loss of freedom.

Furthermore, this autonomy grew over time. Initially, some students sought adult support: “Instead of using trial and error…they immediately asked me to do it.” Over time, independence grew: “They know what to do with very little adult intervention,” “conflicts were solved quickly and by the students.” Parents reported increased confidence, risk-taking, and maturity: “I have seen an increased confident in [child’s] willingness to take risks,” “now she doesn’t look to others before she tries,” and “[Child] has shown more responsibility and maturity.”

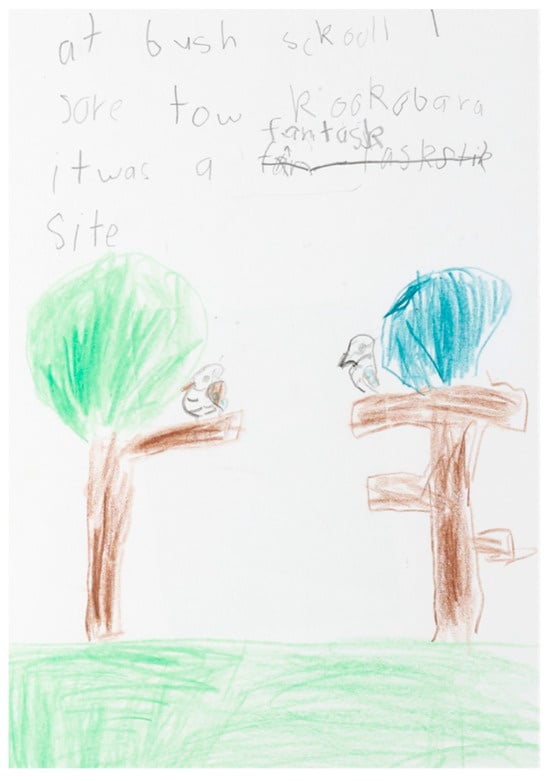

Students also described flow through joy and awe: “I did charcoal…I loved it,” and “I saw two kookaburras. It was fantastic sight” (Figure 6). Teachers linked flow with positivity and engagement: “What they’re doing makes them happy, so they engage more,” and “He could have spent the next hour in the puddle.” Quantitative data suggest emerging gendered patterns. Girls reported increased interest in Bush School activities (“I find the things I do at Bush School really interesting;” MD = 0.62, 95% CI [0.25, 0.98]), and boys showed increased flow at school post-intervention (“At school I get so involved in activities I forget about everything else;” MD = 0.61, 95% CI [−0.08, 1.30]). In both cases, while individual changes were not statistically significant, gender differences were: p = 0.005 for interest, and p = 0.049 for flow.

Figure 6.

Excerpts from student journals showing a fantastic sight. Note: Text reads “At Bush School I saw two kookaburras. It was a fantastic sight”.

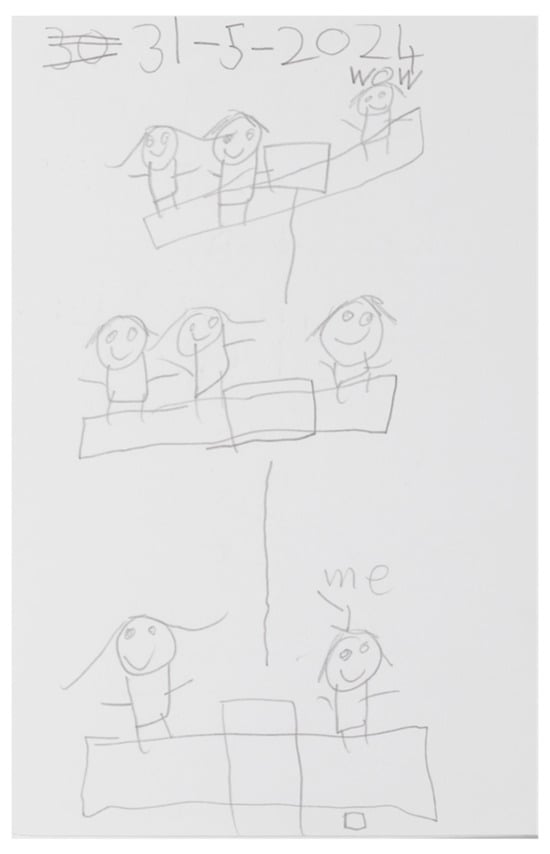

3.4. Sense of Belonging

Students described collective identity and shared experience in both written text: “We saw a huge fish,” “We went on a bushwalk,” and drawing (see Figure 7). Teachers noted: “They’re becoming a little family.” “They spent quality time together doing things they wouldn’t ordinarily do in a classroom.” Parents also noticed deeper friendships: “He seems to have a closer bond with the Bush School kids.” “She is building her social skills.” “My child is more willing to take healthy risks socially.”

Figure 7.

Excerpts from a student journal showing togetherness at Bush School. (a) Drawing of chalk/ochre-making with friends; (b) In the climbing tree with friends; (c) Sitting on logs, talking and eating with friends; (d) Climbing trees and building with others.

Quantitative data for “I feel like I belong in this school” all the time showed a decrease post-intervention (80% to 64%), followed by a modest rebound at follow-up (68%). This decline was significant among girls (MD = −0.45, 95% CI [−0.83, −0.07]), with a partial but non-significant recovery at follow-up (MD = 0.32, CI [−0.16, 0.80]). Boys showed no significant change. Similar patterns were observed for “I work well with other kids in my class,” which declined post-intervention (MD = −0.24, p = 0.1830), with the proportion of all the time responses dropping from 48% to 20%. While this could suggest regression, qualitative findings indicate growing self-awareness around social interactions. For instance, students described making friends through shared tasks: “I helped make a shelter.” “Bush School helps you make friends because you do more playing than you do at school, and you get to meet other kids not in your class.” Some found the Bush School environment socially supportive (“The mean people didn’t go to Bush School.” “A bigger space.” And “Not too many people.”) while others appreciated the broader peer network of the school (“There are more children at school, so more children to choose to play with”).

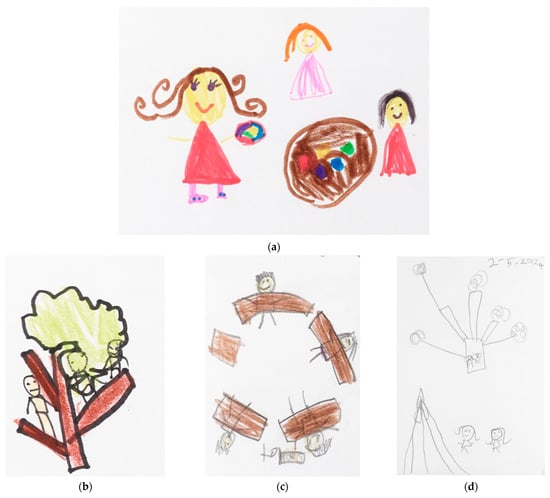

Sensory descriptions and drawings reflected children’s physical connection to place: “It smelled like dirt,” “It felt like wood,” “At Bush School I saw a magpie” (Figure 8). Teachers highlighted students using all senses in learning: “Students were using sight, smell, touch, and hearing to engage in learning,” and described how comfort grew with repeated visits: “They know what they’re doing as they become more comfortable in their space.”

Figure 8.

Excerpt from a student journal showing connection to animals. (a) Magpie in front of a cubby that the children had built. Note. Child said the magpie had come to play; (b) Magpies near the chalk/ochre rock. Note. The children shared that the magpies like them and are not scared of them, so they try to join in their play.

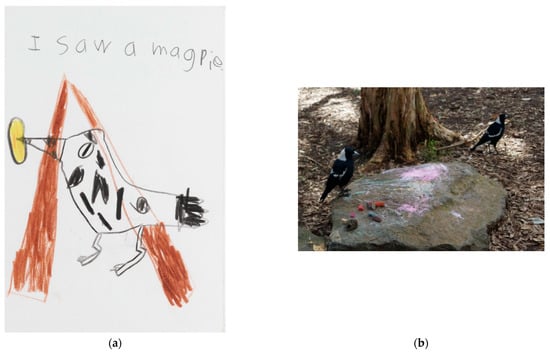

Students also described spatial and spiritual belonging: “Nature gives us places to hide.” “I was safe.” “Nature likes kids to be kids. We can hide, and adults cannot see us.” “If you’re sad you go to the hang out tree and it will give you ideas.” Another expressed empathy for the natural world: “Then I talked to the trees. They were feeling sad because people were being mean. It hurt their feelings.” Gifts like paperbark blankets and clay bowls (see Figure 9) reflected care for the more-than-human world.

Figure 9.

Photos of different presents the children gave to the trees. (a) Children giving trees presents; (b) A clay figurine gift; (c) Paperbark blanket gift; (d) Gift of a clay bowl and decoration. Note: The children asked for the tree’s permission before painting her.

Students, teachers, and parents described students forming stronger teacher–student relationships through shared time in nature. Students noticed teachers being more playful: “[Teachers], and [Deputy Principal] came to Bush School… It was very exciting and fun,” and described them doing unexpected things like walking through puddles or rolling logs (see Figure 10). Teachers and parents: “You just have a different connection with them,” “We laugh together.” “[My child’s] confidence…with her teacher and peers has exponentially increased.” Quantitative data supported these positive connections. The proportion of students reporting “I like talking to the teachers at my school” all the time doubled from 24% to 48%, with boys showing a significant increase at follow-up (MD = 0.67, 95% CI [0.17, 1.17]). Similarly, responses to “Teachers at my school are there for me when I need them” rose from 64% to 76% post-intervention and remained high at follow-up (72%), although these changes were not statistically significant.

Figure 10.

Teachers doing different things. (a) Teachers and students rolling a log together to move it; (b) Teacher walking through a puddle.

3.5. Nature Pedagogies

Bush School provided open-ended, physical, and creative opportunities: “Nature has lots of things that you cannot do with other toys, like you can climb trees. You cannot climb Lego!” They embraced loose parts play, turning bamboo into horns (see Figure 11), and sticks into imaginative characters: “A crazy stick family.” “the two characters even held hands (the two arm sticks touching).” Quantitative data supported this: “I can play lots of different things at Bush School” all the time increased from 76% post-intervention to 80% at follow-up, compared to 52% to 56% at school.

Figure 11.

Students repurposing bamboo as horns.

Environmental constraints like cold, mud, and rain became sites of growth: “We made leaves so that if it’s raining it will give us shelter.” Adults celebrated this transformation:

“[Child] didn’t like getting dirty at first but by the end… didn’t care anymore.”

“It is good for parents to see that their children can cope in the rain and cold!”

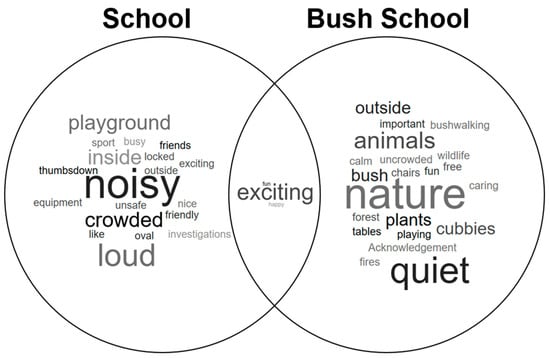

Timelessness (expressed as slowing down) also emerged: “We slowed down at Bush School and could do more things” (see Figure 12). “It made us happy slowing down.” Teachers reinforced this: “Bush School has its own pace.” “There are no time constraints… urgency and rush.” One described the experience as a “luxury… to let the children spend half an hour building a cubby.” “[Teacher] having a chat with [student] on a log… They were chatting for quite a while” (see Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Excerpts from student journals showing what they did when they slowed down. (a) “When we slowed down we saw more things”; (b) Transcription: “We went to the lake and spotted some bird tracks”.

Figure 13.

Timelessness at Bush School: moments for teacher–student connection.

Students described nature as responsive and sacred: “We went to see an eel but we were a little loud and it hid.” “Trees became like friends.” “I learnt trees can communicate with me if I listen carefully and I’m kind to them.” “The trees are the stars of nature… the heart of nature.” “Everything in nature has feelings like us, even the sky.” This aligned with an ethical sensibility: “It’s important to look after nature.” “Nature is everything.” “I think adults need to know that nature is responsible for the start of the earth, so it is important to all of us.” These insights are attributed to attending Bush School: “Bush School helped us connect with nature.” “You learn to help and play with nature.” “It helped me by seeing animals are more than just little slimy things.” Additionally, respect for Country was evident through acknowledgement practices and ethical guidance: “Only take treasures that are lying on the ground.”

3.6. Additional Insights

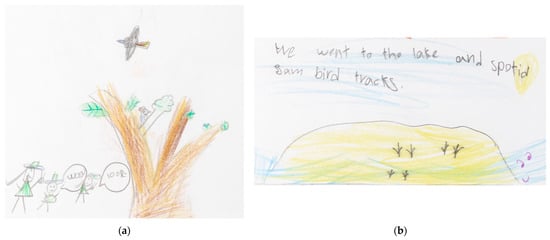

While most data aligned with the components of the GINGER model, three notable themes emerged that extended beyond its framing. These insights enrich our understanding of the layered complexity of children’s experiences during Bush School and provide important context for interpreting the broader findings. First, children perceived Bush School as distinct from school. While school was described as “noisy” and having “more people,” Bush School was characterized by “quiet,” “trees”, and “nature.” Still, both settings were seen as “exciting,” “happy,” and “fun” (see Figure 14). However, overall, children appeared to prefer Bush School: the number of children who reported “I like Bush School” all the time increased from 84% to 92%, while “I like school more than Bush School” declined from 52% to 36%.

Figure 14.

Student descriptions of school and Bush School: Word cloud Venn diagram showing affective and environmental contrasts.

The impact of Bush School also extended beyond the school gate. One child, for example, led her family back to the Bush School site (see Figure 15). Her mother shared this moment with pride, a response that highlights the potential for nature play to ripple into home life, reinforcing agency, knowledge, and connection to place. This suggests that the learning children experienced was not only memorable but meaningful enough to prompt re-engagement and sharing beyond the classroom. Such moments signal the potential of outdoor learning to cultivate lasting ties between school, family, and place.

Figure 15.

A student recounts their weekend visit to Bush School with their family. Note: Transcription of text: “On the weekend I went to the park and I got swooped by a kookaburra and I saw two of my friends called [redacted] and [redacted] and I went to Bush School and we helped some children make a shelter and showed my parents the pine forest and we had a picnic”.

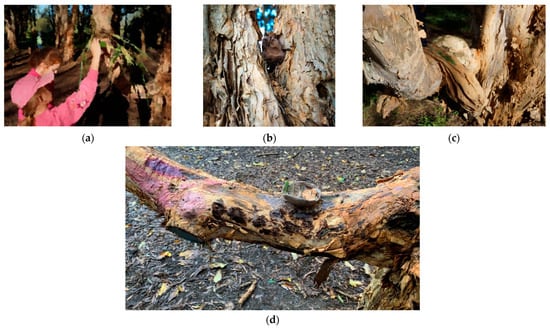

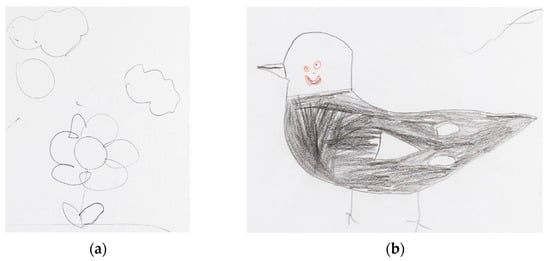

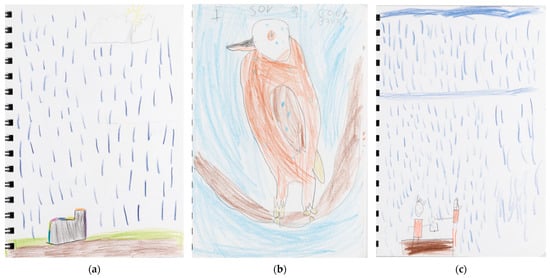

Finally, children’s perceptions of nature evolved. Early drawings often depicted idealized versions of nature (for instance, stylized flowers, animals with human features, and disproportionate representation; see Figure 16). Over time, as children encountered wildlife and discomforts like rain and mud, their representations become more realistic (see Figure 17). Quantitative data mirrored this trajectory: the percentage of children who felt “Being in nature makes me very happy” all the time shifted from 88% to 72% before rebounding to 88%. A similar pattern was observed for “Spending time in nature is important to me” (72% to 64% to 68%). These fluctuations may reflect a shift from romanticized ideals toward more nuanced, lived understandings of nature developed through direct experience.

Figure 16.

Excerpts from student journals showing drawings of nature at the start of Bush School. (a) Drawing of a flower; (b) A bird with a human face.

Figure 17.

Excerpts from student journals showing drawings of nature after Bush School. (a) Cubby in the rain; (b) “I saw a kookaburra”; (c) Playing in the rain at Bush School.

4. Discussion

This discussion explores the significance of nature play through the study’s findings, framed by the four throughlines of the GINGER model: well-being, engagement, belonging, and nature pedagogies. While well-being, engagement, and belonging emerged as student-reported and observed outcomes, nature pedagogies provided a distinctive perspective, revealing how the design and conditions of nature play shaped these developmental gains. Beyond GINGER, additional insights include nature’s unique contributions within PBL, the interplay between Bush School and conventional schooling, emerging gender patterns, and implications for academic performance.

4.1. Well-Being: Beyond Comfort to Developmental Challenge

Nature play supported children’s well-being not only through happiness but through emotionally rich experiences encompassing calm, challenge, and wonder. Student journal entries and teacher reports indicated that many students found Bush School calming and a buffer against anxiety and technology. This evidence aligns with theories of nature’s restorative effects (; ) and evidence emphasizing green time as a protective factor in child well-being (). Furthermore, the benefits gained through passive and active engagement with nature support the dual benefits of nature engagement for children ().

Importantly, this study highlights that well-being includes encounters with manageable adversity. Children openly shared experiences of being cold, wet, or physically hurt, yet choosing to persist. Rather than diminishing well-being, these instances appeared to foster emotional resilience and adaptive coping strategies. The notion of nature providing developmentally appropriate adversity (i.e., exposure to manageable challenge within a supportive context) emerged as an interpretative theme warranting further investigation. This finding challenges prevailing societal norms that seek to overprotect children from discomfort, suggesting that nature play offers a vital space for experiential learning about emotional regulation and persistence.

4.2. Engagement: Embodied, Multisensory, and Autonomous

Nature play fostered deep, sustained engagement by offering autonomy, competence, and multisensory exploration. Observational and qualitative data show that children actively shaped their play based on intrinsic interests and developmental needs, reflecting key tenets of self-determination theory (), which posits autonomy and competence as core to motivation. The observed joy and focus in self-directed activities like cubby building and imaginative play provided evidence of conscious agency and mastery (). The teacher-reported feedback loop, where joy enhanced engagement and vice versa, supports ’s () emphasis on student agency, meaningful activity, and competence as drivers of sustained engagement.

Furthermore, the multisensory nature of outdoor environments appeared to catalyze learning beyond cognition, engaging vision, hearing, touch, smell, and kinesthetic awareness simultaneously. ’s () presence network, which describes engagement as a cyclical process of sensing and acting, is particularly salient here. The interplay of distal (vision and hearing), proximal (touch, taste, and smell), and embodied (kinesthetic movement, body awareness, and intuition) sensory modalities created a rich, lived learning context grounded children in their physical experience, consistent with embodied cognition theories (; ).

Children’s descriptions of slowing down and observed deep absorption in activities resonate with ’s () concept of flow, a state of intense engagement where time appears to slow. This immersive quality also aligns with the idea of slow being, which refers to a form of participation that is unhurried, allowing space for reflection, presence, and meaning-making (). It also connects with the principles of slow pedagogy, an approach that values the present moment and prioritizes children’s meaning-making by taking the time to listen, understand, and be playful (). These unhurried modes of reflective participation may offer an antidote to the “hurried child” phenomenon (). The combined qualitative and observational data suggest that, freed from external pressures and the clock-driven school day, children engaged deeply with peers, teachers, and the more-than-human world, fostering developmental growth and countering stress.

Gendered differences also emerged in engagement trajectories. Quantitative data showed that girls demonstrated a significant increase in interest in Bush School activities over time, suggesting growing emotional investment and intrinsic motivation. However, this was accompanied by a significant decline in girls’ perceived autonomy at follow-up. This contrast raises important questions about the interaction between structure, freedom, and gendered perceptions of control, particularly when children move between the Bush School and PBL environments.

Qualitative data reveal a complex and somewhat contradictory picture of this dynamic. Early in the intervention, structural constraints, such as limited space and adult-imposed schedules, restricted children’s ability to choose what, when, and where to engage in activities, which likely limited autonomy. Notably, the amount of free time in each session increased over the course of Bush School, suggesting increased opportunities for self-direction. This is reflected in journal entries expressing strong agency. For example, one girl wrote, “I like Bush School because you get to climb in the climbing tree and because you get to investigate.” This suggests that, over time, some girls experienced moments of agency, even as overall perceptions of autonomy among girls declined. Nevertheless, the disconnect between these qualitative expressions and the quantitative decline in perceived autonomy points to a possible anomaly or unresolved tension, suggesting that factors beyond structural constraints (such as social dynamics, gendered expectations, or internalized notions of compliance) may have influenced girls’ perceived autonomy.

Cognitive and behavioral patterns also varied. Quantitative data showed that boys showed a greater decline in classroom concentration post-intervention (p = 0.060) but reported increased cognitive absorption (p = 0.049), though this was not significant within-group. In contrast, effort-related engagement following recess showed a gender difference (p = 0.033): boys declined slightly while girls increased. This suggests divergent responses to transitioning between outdoor and indoor learning. These findings raise questions about how children may respond differently to transitions between outdoor and indoor environments, with nature play affecting their focus and motivation in gendered ways.

These findings suggest that autonomy and engagement may be negotiated differently across gender, a pattern not widely reported in the nature-based learning literature, where most studies focus on the broader benefits for all children. While emerging research in forest school and outdoor learning contexts has begun to explore gendered patterns (for example, ; , few studies examine how autonomy is subjectively experienced over time, or how it may diverge from observed or reported agency. (), for instance, argues that outdoor settings can invertedly reinforce gender norms, which may shape how autonomy is enacted or perceived. In this light, the divergence between girls’ growing emotional investment and their declining sense of autonomy may reflect broader social or psychological processes. These dynamics align with research from classroom contexts showing that boys and girls respond differently to autonomy support (, suggesting potential relevance beyond the outdoor learning.

Given the school’s existing PBL approach, these findings are particularly noteworthy. They suggest that nature play may offer additive benefits beyond indoor PBL, particularly in how it supports emotional engagement and embodied autonomy. However, they also point to the fragility of these gains when children return to more structured environments, where implicit norms and contextual factors may dampen perceived agency. Further research is warranted to clarify how different learning environments interact with children’s autonomy, motivation, and gendered experiences over time. Comparative studies involving both structured and unstructured outdoor programs could offer deeper insight into how varying levels of environmental freedom shape children’s engagement and sense of self.

4.3. Belonging: Affective and Reciprocal

Outdoor nature play in early childhood has long been recognized as fostering the development of social skills through authentic, affectively rich interactions (for instance, ; ; ). In this study, nature play supported children’s relatedness, reciprocity, and inclusive participation. Qualitative data showed that some children’s social worlds shifted within the Bush School context. New friendships, cooperative behaviors, and shared goals tended to emerge more readily during child-directed play than under adult direction. These patterns echo findings from outdoor adventure education programs, which similarly leverage nature-based contexts to disrupt existing social dynamics and foster trust, interdependence, and group identity (). While such research focuses on adolescents and the role of environmental challenge (; ; ), this study shifts attention to primary-aged students. In this context, the introduction of a novel natural setting appeared to open new social pathways by creating a shared, embodied experience of place and community.

To deepen understanding of these observed dynamics, this study draws on insights from positive psychology. While early childhood and adventure education research often highlight the social outcomes of outdoor experiences, integrating a positive psychology lens helps to illuminate how these connections are formed and sustained. Specifically, the interactions observed at Bush School reflected what ’s () describe as high-quality connections; brief, meaningful exchanges that build psychological safety and emotional uplift. Similarly, ’s () theory of positivity resonance highlights the role of shared positive emotion, mutual care, and behavioral synchrony in deepening social bonds. These micro-moments, while fleeting, accumulated over time, strengthening students’ emotional connection to each other and to the natural world.

These relational shifts seemed to be enabled by the unique social affordances of nature play. Nature play provided a less structured, less evaluative context than the classroom, allowing children to be seen and known in new ways. This aligns with ’s () argument that the psychological need for relatedness is foundational to motivation and well-being. Teachers reported notable social transformations, observing that children previously considered disruptive or withdrawn became leaders and collaborators outdoors, effectively “rebooting” their social identities. These shifts correspond with ’s () ideas of meshed architecture and social cognition, which emphasize the interplay of pragmatic skill (knowing how to respond to others in interactive terms) and affective attunement (awareness of others’ attitudes and emotional states) in social interactions.

To complement these qualitative insights, quantitative data provided a nuanced picture of how children’s sense of belonging evolved over time. Interestingly, the data revealed gender differences, with a temporary dip in girls’ reported school belonging and friendship networks, which recovered by follow-up. In contrast, boys demonstrated more stable belonging measures throughout. This pattern may reflect what () term delayed engagement effects or could indicate the emotional and social adjustments required when navigating between the fluid dynamics of Bush School and the structured classroom. The dip in girls’ belonging might also represent active identity work, with students renegotiating peer norms, roles, and emotional security as they gained independence and explored new social configurations in nature. Rather than reflecting social withdrawal, this reorganization of friendship dynamics may indicate relational transformation. In this way, belonging transcended mere inclusion to encompass embodied recognition, reciprocity, and co-authorship of social meaning. This broader conceptualization aligns with calls by () to move beyond reductive models of relationality and reconceptualize belonging and social interaction as central to human flourishing.

Teachers’ interpretive frames appeared to play a critical role in shaping these dynamics. When educators embraced playful, emotionally available roles, relinquishing control and reducing performance pressure, children responded with increased confidence, cooperation, and care. This is consistent with ’s () findings that outdoor learning is shaped by how teachers perceive and respond to student behavior. () similarly found that underachieving children often demonstrated greater cooperation, pro-social behavior, and task engagement outdoors. The reciprocal transformation of adult pedagogical stance and child behavior suggests that nature play as a relational ecology reshapes the entire learning community. Interestingly, boys reported a significant increase in positive relationships with teachers over time, suggesting that nature play may have reframed classroom relationships through shared trust and informal connections.

4.4. Nature Pedagogies: Designing Conditions for Development

The conditions and design of nature play emerged in this study, revealing how environmental features supported distinct developmental, sensory, and learning outcomes beyond those offered by the classroom PBL program. Observed data showed that Bush School provided responsive, co-constructed affordances that children continuously interpreted and reinvented. This aligns with research suggesting that natural settings shape not just what children play, but how play unfolds, emotionally, socially, and imaginatively, due to their open-ended, dynamic qualities (; ; ; ).

Observed interactions reflected ’s () theory of affordances and ’s () loose parts theory. Natural elements (sticks, rocks, trees, uneven ground) offered personalized invitations for climbing, balancing, hiding, and imaginary play, adaptable to each child’s interests and developmental trajectory. These elements functioned not simply as tools for manipulation but became social and emotional artefacts mediating relationships, narratives, and co-constructed worlds. () argues that natural elements expand play beyond function by stimulating sensory variety and imaginative engagement, a perspective supported by our observations. These affordances were not static or generic, but evolving possibilities enabling children to “take what they need” ().

Within this context, control was not imposed but negotiated between children, materials, and the environment. The qualities of nature play appeared to amplify autonomy, collaboration, and emotional expression, supporting new ways of being, relating, and learning. While classroom PBL fostered agency within structured routines, the Bush School environment invited deeper improvisation and shared inquiry. These findings suggest that nature pedagogies are not merely an extension of PBL, but a distinct developmental context with unique opportunities for holistic growth.

Importantly, the teachers adjusted their pedagogical practices in response to their observations during Bush School. They actively integrated elements from the Bush School into classroom routines by incorporating natural materials and extending the existing PBL program to operate seamlessly across both indoor and outdoor environments. This integration reflects a shift in teachers’ perspectives on children’s capacities and confirmation of the value of child-led exploration, autonomy, and sensory engagement. For practitioners, these insights highlight the potential to enrich traditional classroom pedagogy by embedding nature pedagogies, which may foster deeper student engagement, creativity, and well-being.

4.5. Nature Play and School as Complementary

Rather than diverting from academic learning, nature functioned as a parallel pedagogical space, extending and recontextualizing curriculum-linked concepts through embodied, authentic, and relational experience. Teachers reported that they intentionally structured lessons to build on ideas and skills developed during Bush School, fostering continuity between indoor and outdoor learning environments. However, they also recognized that certain elements of the Bush School experience, such as unstructured exploration and immersion in a natural setting, were not fully replicable within the classroom. Thus, teachers viewed, Bush School as a unique and distinct learning context that complemented, rather than replaced, classroom pedagogy.

Children, likewise, viewed Bush School and classroom learning as distinct yet complementary. They described Bush School as “quiet,” “calm,” and “peaceful,” contrasting it with the “noisy” and “crowded” classroom, yet valued both as sources of fun and happiness. This dual appreciation challenges the traditional divide between play and formal schooling, supporting evidence from the literature that play strengthens cognitive functions central to learning (; ). This study extends that work by showing that nature play can generate developmental gains beyond those seen in classroom PBL alone. These findings position nature as a co-teacher in academic, social, and emotional learning.

The main distinction lay in the type of context and depth of engagement observed. Interest-driven experiences in nature enhanced autonomy, competence, and relatedness; the motivational triad central to academic engagement (; ; ). Teachers noted students returned to class more emotionally regulated and socially attuned. These observations align with ’s () concept of “refueling in flight” (p. 1). Crucially, children also appeared to transfer outdoor dispositions (such as empathy, collaboration, and resilience) into more cooperative and focused classroom participation.

Academic benefits were strongest in mathematics. Teachers and students described how Bush School activities offered embodied opportunities to explore concepts like mass and measurement. These benefits support ’s () finding that guided play enhances mathematics learning over free play or direct instruction. Affordances like balancing on logs, lifting heavy objects, and building shelters provided embodied opportunities to explore abstract concepts. This reflects ’s () concept of horizontal expertise, where learning flows fluidly across contexts, roles, and tasks. The relational quality of nature play may have further contributed, as positive teacher–student relationships are linked to improved mathematics performance and belonging (). At Bush School, children learnt within a supportive, reciprocal environment that appeared to reinforce both academic engagement and emotional safety.

Nature’s pedagogical power lay in her openness to both guided and emergent learning. As () argue, nature recontextualizes curriculum content, offering “many pathways to learning” (p. 385). In this study, evidence suggests that those pathways were not only cognitive but also sensory, emotional, and social. These multiple modes of engagement and expression diversified learning, making it more accessible and meaningful for different learners. This responsiveness is especially relevant for equity and differentiation in diverse classrooms and supports broader calls to honor multiple ways of knowing and being.

Finally, learning extended beyond school boundaries. One child led their family back to the Bush School site, proudly sharing stories and activities tied to place. Parents recalled children bringing discoveries home. These accounts indicate that learning was not only retained but recontextualized. Such examples illustrate how nature play fosters transcontextual meaning-making, affirming children as knowledge holders and co-constructors across formal and informal settings. This continuity affirms the depth of learning that occurs when curriculum is not just taught but lived.

4.6. Beyond Romantic Views of Nature

While nature play is often framed as calming or idyllic, this study revealed a more complex, pedagogically rich reality. Nature was not simply a gentle backdrop for emotional regulation. It was also muddy, cold, unpredictable, and often challenging. Yet, these conditions were not deterrents to learning. Instead, they created opportunities for discomfort, risk-taking, and resilience. This reframes nature as an active co-participant in learning, offering unpredictable and demanding encounters.

Teachers and students described nature as relational and responsive. Encounters with animals and landscapes sparked ethical reflection. For example, fascination with an eel promoted discussions about care and coexistence. This echoes ’s () idea of learning “shared space” with the more-than-human world through embodied experiences (p. 384). Over time, repeated interactions shifted children from observers to ecological participants (), becoming emotionally and ethically entangled with nature.

This was especially visible in the way children related to trees. One child shared, “I talked to the trees. They were feeling sad because people were being mean. It hurt their feelings”. Another said, “If you’re sad, you go to the hangout tree, and it will give you ideas.” The ‘hangout tree’ became a powerful symbol (both a physical location and an emotional companion), offering emotional anchoring, inspiration, and solace. These narratives reflect ’s () enchanted animism, a playful, responsive form of noticing that fosters immersion and wonder, helping children “listen to the Earth more attentively” (p. 233).

These experiences resonate with relational ecological frameworks. () describe learning as reciprocal co-shaping between children and the more-than-human world, while () frames “children–forest encounters” (p. 55) as mutually agentic. () calls these moments “glowing”, charged with meaning and world-making. In this study, children’s spontaneous storytelling, symbolic play, and acts of care suggest that nature was not only pedagogical but ontological in shaping how they saw themselves in relation to the world. This reflects () view of children not merely in nature but of nature.

Repeated visits to the same bush site deepened these relationships. What began as a novelty evolved into attachment, memory, and meaning. This progression mirrors Indigenous relational logics, which reject a human–nature binary. As the () expresses, “We belong to the land and it belongs to us. We sing to the land, sing about the land. We are that land. It sings to us.” While not representing Indigenous knowledge systems, its findings align with such ways of knowing, as seen through children’s own vernacular.

4.7. Strengths and Limitations

Findings from this study provided rich detail on the impact of a 10-week nature play intervention on Year One students’ academic performance, well-being, school engagement, and connection to nature. Conducted in a real-world school context, the study generated authentic data on how nature play supports holistic development in the early years of primary school. In doing so, it addresses several key gaps in the literature, namely the underrepresentation of children under eight in outdoor learning research (), the limited uptake of outdoor learning in Australian primary schools (), and the tendency to examine well-being, engagement, and learning as separate domains rather than as interconnected aspects of children’s lived experience. These combined insights offer practical value to schools, nature play providers, various fields of psychology, and policymakers in shaping educational provisions during the foundational years of schooling.

While the study offers important contributions, several limitations should be acknowledged. The quasi-experimental design limits causal inference, and the use of self-selected groups introduces potential selection bias. Although appropriate statistical techniques were used (such as multi-level modelling with mixed-effects ordinal logistic to account for the nested structure of the data, and Wilcoxon tests for non-parametric comparisons), some confounding variables could not be fully controlled. Factors such as classroom dynamics or students’ prior/additional exposure to nature could not be fully controlled. The study also took place in a single metropolitan school with a small, demographically homogenous sample, further limiting the generalizability of findings to more diverse educational contexts.

The intervention was implemented within a school already aligned with progressive pedagogies, which may have influenced both delivery and reception. Although children’s voices were central, adult interpretation still shaped the framing of findings. The student self-report tools (PNEW and PNEW–B) were developmentally appropriate, but the potential for social desirability bias (particularly given the intervention’s positive framing and the lead researcher’s presence) highlights the need for more independent data collection in future studies. The 10-week duration with a 4-month follow-up offered some insight into trends, but was insufficient to assess long-term impact. Future research should incorporate longer-term tracking of outcomes and explore more autonomous ways of capturing children’s lived experiences.

4.8. Recommendations

Despite these limitations, the findings highlight important implications for practice, policy, and research. We recommend the following: For schools:

- Embed nature play into early primary curricula as a core pedagogical approach, not merely an enrichment activity.

- Treat outdoor learning as integral to academic development, well-being, engagement, and sense of belonging.

- Include nature play as a pedagogical bridge across key transition points, for example, from preschool to primary school.

For policymakers:

- Prioritize nature play through targeted policy and investment.

- Fund the creation of accessible, safe, natural spaces in school environments.

- Provide professional development for educators to embed nature pedagogies confidently and effectively.

- Recognize and support nature play’s broad developmental benefits, ensuring equity of access across all school contexts.

For researchers:

- Expand research through longitudinal mixed-methods studies in diverse educational settings.

- Center children’s voices through child-led methods such as interviews or digital storytelling.

- Investigate demographic variables (for example, gender, socio-economic status) to understand how nature play is experienced across different groups.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that nature play meaningfully supports children’s well-being, engagement, belonging, and connection to nature. Over ten weeks, students experienced Bush School as a space of joy, calm, curiosity, and growth, describing it not as a break from learning, but as a different kind of learning. The mixed-methods quasi-experiment found no negative impact on literacy or numeracy, countering concerns about lost instructional time. Instead, nature play complements formal education by self-regulation, collaboration, and interest. While context-specific, these findings point to broader opportunities: embedding nature play in mainstream schools offers a developmentally appropriate response to current educational challenges. The study also highlights the importance of listening to children as insightful participants capable of making meaning with insights that deepen our understanding of matters that affect them. In a time of mounting pressures on children and schools, nature play offers more than a method; it offers a shift in mindset, to trust, slow down, and recognize the more-than-human world as a co-teacher, guiding children’s growth and learning in powerful, transformative ways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, A.H.; Methodology, A.H.; Validation, A.H. and S.H.; Formal analysis, A.H.; Investigation A.H.; Resources, A.H.; Data curation, A.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.H.; Writing—review and editing, S.H. and T.G.; Visualisation, A.H.; Supervision, S.H. and T.G.; Project administration, A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The school participating in this study received funding from Centennial Parklands Foundation’s Education Access Pass Program that covered transport and program costs. The lead author is a doctoral student and is supported by the Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) fee offset scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Western Sydney University. Project ID number: H15600, on 14 August 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article are not readily available due to privacy restrictions and ethical considerations regarding minors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the students, teachers, parents, and wider community of the school that participated in the study. Their generosity in supporting this project is greatly appreciated as are the contributions of Greater Sydney Parklands. Thanks is also extended to the reviewers for their constructive and thoughtful feedback that helped improve the quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACARA | Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| PBL | Play-based learning |

| PNEW | Play, Nature, Engagement and Well-being questionnaire |

| PNEW–B | Play, Nature, Engagement, and Well-being—Bush School questionnaire |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Alignment of the GINGER elements to components of the throughlines.

Table A1.

Alignment of the GINGER elements to components of the throughlines.