Abstract

There is currently concern about the decrease in physical activity participation among university students. To address this issue, different pedagogical approaches have been developed to improve participants’ motivation, with gamification standing out among them. Gamification integrates game design elements into learning environments to increase responsibility, motivation, and engagement in physical activities in different educational stages through intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, although evidence is limited and diverse. Therefore, this study investigates how gamification affects the motivational profile of university students in the context of physical activity. The study was conducted with university students of Physical Activity and Sports Sciences (n = 72), using an experimental design that included a gamified group (GG) and a control group (CG) without gamification. A questionnaire was used to measure motivation before and after the intervention. The results showed a significant increase in intrinsic motivation and a decrease in amotivation in the gamified group, while no significant changes were observed in the control group. However, there were increases in extrinsic motivation in both groups. These findings suggest that gamification can be effective in improving intrinsic motivation and reducing amotivation in university students for physical activity as well as enhancing extrinsic motivation considering the rewards used.

1. Introduction

Several factors have led to a decrease in physical activity levels within the daily routine of students. These factors range from inadequate nutrition, sedentary lifestyle, lack of time, distorted perception of body image, and social pressure to meet aesthetic standards [1], which can trigger behaviors that hinder participation in physical activities. Likewise, a significant number of students show high levels of amotivation (Am) and lack of interest in physical practice [2,3]. This lack of motivation, both intrinsic and extrinsic, can have harmful consequences on students’ participation and learning process [4,5,6,7], resulting in a negative impact on their learning experience.

With the aim of fostering an improvement in students’ motivation towards their current education, various pedagogical models and active approaches have emerged, aiming to stimulate students’ interest and participation in physical activities [8]. These innovative methodologies not only seek to increase student engagement but also to enrich their learning experience in the field of physical education and sports.

A theory that provides a valuable perspective for understanding motivation in the educational context is the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) developed by Ryan and Deci [5]. This theory posits that human motivation exists on a continuum from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation, with a particular emphasis on the fulfillment of four basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, relatedness, and novelty. When these needs are met, individuals tend to exhibit higher levels of intrinsic motivation, which in turn leads to greater engagement, persistence in activities, improved performance, and overall well-being. In the realm of physical education, cultivating an environment that supports these needs can be essential for addressing the observed levels of amotivation and promoting active and committed participation among students [5]. This aligns with the implementation of pedagogical models and active approaches aimed not only at increasing motivation but also at enriching students’ learning experiences.

One of the approaches that has gained considerable prominence is gamification, which involves enhancing participants’ experiences by implementing game elements [9]. Gamification originated in areas outside education, such as marketing, health systems, and environmental protection, in order to improve interest and participation [10]. Later, it was observed that in the education system, this could be a tool to study that could improve learning, commitment, and participation [11,12]. Indeed, various types of gamifications have been increasing in popularity in various education settings due to the integration of effective technologically advanced mobile devices, virtual reality, and social networks [13]. Effective implementation of gamification can increase student motivation, active learning, and enjoyable and immersive educational situation [14]. Specifically, in the area of education, gamification can be a tool with great affinity for teaching physical activity practice due to its highly playful component that can promote greater motivation of students [15,16]. Moreover, gamification strategies lead to setting specific objectives in PE classrooms, making a way to achieve problem solving, decision making, and strategic thinking, which are cognitive skills essential for sports practice [17]. In the university physical activity context, authors who implemented gamified interventions observed increased responsibility and consequently higher participation [18] as well as higher intrinsic motivation (IM) and extrinsic motivation related to higher qualification in the subject [19]. In the same vein, Ferriz-Valero et al. [20] observed that a gamified proposal seemed to improve students’ IM and Am. However, in another research, Ferriz-Valero et al. [21] used the ClassCraft application during their gamified proposal, which quantified an increase in external regulation (ER) of students, while IM remained stable. Similarly, Arufe Giráldez [22] implemented university gamification based on “Fortnite”, and Flores-Aguilar et al. [23] generated significant increases in motivation and commitment to physical activity.

In the same way, like research carried out with university students, there is an increasing amount of literature looking into the use of gamified approaches in high school education, especially in physical education classes. According to Quintero González et al. [24], the use of gamified learning methods in secondary education increased students’ motivation, promoted teamwork, and developed a stronger dedication among students. This aligns with research conducted by Fernandez-Rio et al. [3,25] demonstrating that a gamified approach resulted in higher levels of internal motivation in secondary and primary school students, which is especially beneficial for those starting with lower levels of motivation. Similarly to the findings of Ferriz-Valero et al. [20] in university groups, Soriano-Pascual et al. [26] reported that using different gamification methods such as incentives and obstacles successfully enhanced motivation and reduced disruptive conduct in high school students. These results, in conjunction with those of Martín-Moya et al. [27], who observed increased levels of motivation and dedication among high school students, indicate a similar trend in the effects of gamification in both university and secondary education settings.

In another context, Grech et al. [28] implemented a gamified proposal in an adult sample (>18 years), where they noted that there was no difference in intrinsic motivation when performing physical activity. However, despite the lack of psychological effects, the use of gamification resulted in greater performance, with a greater number of steps taken. This suggests that the implementation of a gamified proposal does not always achieve motivational improvements.

Despite this wealth of research, information regarding the effect of gamification on the motivational profile of university students in the field of physical activity is limited and diverse. Additionally, some of the previously cited articles show limitations, such as lack of a control group [19], lack of probabilistic sampling [19], and failure to specify the type of motivational regulation from which changes were obtained [18,22].

Therefore, this present research aimed to observe how gamification, among university students in subjects focused on physical activity, can affect the motivational profile.

- Hypotheses

H1.

The use of a gamified program among university students will increase IM compared to the CG.

H2.

The use of a gamified program among university students will not change extrinsic motivation compared to the CG.

H3.

The use of a gamified program among university students will decrease Am compared to the CG.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This research was based on the collaboration of students enrolled in a university academic degree in Physical Activity and Sports Sciences. These students agreed to participate in the research by formalizing an informed consent and were previously instructed about the possible implications and inherent benefits of the study. It is worth noting that these participants gave their approval for the publication of their data and were ensured anonymity.

The final sample was formed from a significant number of individuals enrolled in the Bachelor’s Degree program in Physical Activity and Sports Sciences. The average age of these participants is estimated at approximately 21.8 years, with a standard deviation of 3.59. The selection of the sample was guided by exclusion criteria related to adherence to specific principles, including active participation throughout the research process and completion of the proposed measurement instruments. Although a total of 102 students expressed interest in participating in the study, the rigorous application of the criteria led to a final sample composed of 72 individuals. It is important to highlight that all participants, in a gesture of voluntary commitment, formalized their informed consent in accordance with the principles established in the 1975 Helsinki Declaration. This ethical action allowed the study to be approved by the ethics committee of University of Alicante (UA2022-05-24).

2.2. Study Design

The research was conducted during the academic year 2022, in the Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Activity and Sports Sciences, specifically in the subject of Physical Activity in the Natural Environment. The study was based on a natural quasi-experimental design that included both a gamified group (GG, n = 35) and a control group (CG, n = 37) as well as pre- and post-intervention measures [29]. To test the proposed hypotheses, participants were assigned to the CG and the GG through cluster-randomized sampling.

The CG was used as a reference point without gamification, following the methodology of [29]. In this way, possible effects attributable to the educational institution itself were controlled, as the same content was taught with the same methodology and by the same teacher (principal researcher). The first group’s class was scheduled from 15:00 to 17:00, while the second group had their class from 17:00 to 19:00. Designs previously used in similar studies were taken into account [17,30,31].

2.3. Intervention

According to Hastie and Casey (2014), a comprehensive intervention needs to include: (a) a thorough description of the unit’s curriculum components; (b) a thorough validation of the intervention model; and (c) a thorough description of the program’s environment. We will now describe these sections in as precise a manner as we can.

The intervention program was carried out by a teacher familiar with the students (principal researcher). The principal researcher was trained in implementing gamified pedagogical approaches through the use of new information and communication technologies. The researcher responsible for the intervention was the same throughout, limiting the bias that would have resulted from the intervention of multiple professionals. The intervention program took place during a subject in the degree, which lasted for 5 weeks, with a duration of 30 h (Table 1).

Table 1.

Scheduled development for the subject classes.

To ensure a comprehensive and comparative evaluation of the effects of the gamified intervention on student motivation, a questionnaire was used before starting the intervention and at its conclusion.

A teaching plan was created based on the contents covered during the sessions, which included climbing, orienteering, and swimming. These contents are covered because they are programmed as essential components of the university subject of Physical Activity in the Natural Environment. After the activities were completed, students were notified of the qualification obtained in the activities to be evaluated. Both the GG and CG underwent similar content; however, the difference lay in how it was implemented, through a gamified Information and Communication Technology (ICT) tool called ClassCraft (Classcraft Studios Inc., New York, NY, USA) used only with the GG group. This tool was the primary distinguishing factor between the two groups. ClassCraft presents itself as a gamified collaborative educational proposal where teachers can create student and class codes for personal accounts that are not transferrable allowing participants to customize their own avatars. Three different roles were available: Warrior, Healer, or Mage, each possessing unique abilities that promoted interaction and teamwork among clan members.

Each player character has their own strengths, weaknesses, and abilities. Warriors, who play a more offensive role, tend to lose health quickly but can absorb damage to others and heal themselves. Healers are often chosen by students who enjoy helping others and can restore health for themselves and their team members. Finally, mages grant action points to team members and are often chosen by students who rarely lose health, as mages have less health than other characters.

Teams were formed on their own, leaving the decision to students. The only condition was that they had to be coeducational and have at least three members, representing all characters in the game. All participants signed what was known as the Hero Pact. By signing this pact, they agreed to abide by the rules of the game and all decisions made by the “Grandmaster” (principal researcher). The evaluation and redirection of behaviors took a gamified approach, where different points were assigned: experience points (XP), health points (HP), power points (PP), action points (AP), and gold pieces (GP). These points acted as tools for reinforcement (Table 2) or punishment (Table 3) based on Skinner’s philosophy (1974). For instance, when a character lost their HP or AP in the game, it was seen as a form of punishment, while gaining XP upon completion of tasks was taken as positive reinforcement for behavior exhibited during gameplay. GP allowed customization for characters, while XP facilitated leveling up through points acquired via positive actions and appropriate tasks completed during gameplay. HP, which is crucial for survival in the game, could drop as a result of negative actions taken by the player and could then be reinstated by the healers within the team. AP and PP were used as fuel to trigger powers that had been obtained through leveling up or special items acquired during play. If a character loses all of their HP, in order to continue in the gamified proposal, he had to participate in a penalty to be able to keep their character alive (1 HP).

Table 2.

Reinforces quest to improve character statistics.

Table 3.

Punishment goals to modify student behaviors.

The platform of ClassCraft promoted social gamification. The participation of individual students was aimed at achieving a certain common result by group cooperation, which was more favorable than individual work. Among the features that the tool offered were presenting problems as bosses at the end of the level, with their defeat leading to completion and victory and creating random events that caused uncertainty for students. Every character had their own strengths and weaknesses, along with unique powers; this setup encouraged diversity among roles and strategies in gameplay.

Additionally, the use of ClassCraft allowed for the successful integration of both the Mechanics–Dynamics–Aesthetics (MDA) model and the Points–Badges–Leaderboards (PBL) model, thus enhancing the learning experience. The MDA model was inherently integrated within the platform and was actualized through the formation of student clans, further reinforcing this gamified approach. This particular framework facilitated an exploration and comprehension of mechanical, dynamic, and aesthetic dimensions of actions within the educational game. Points, badges, leaderboards, rewards, challenges, and levels can be used in PE gamification to motivate students and create a more game-like atmosphere [32] (Table 4).

Table 4.

List of MDA model elements.

The mechanical elements took the lead in describing the processes and actions available in the game, ensuring that learners were well informed on a granular level about what they could and could not do on the platform. In contrast, dynamics sketched out the interplay among these operations, nurturing cooperation while also sowing seeds of healthy competition between clans. The aesthetics or tools of the MDA waded into the emotional quagmire, aiming to elicit responses from students based on their engagement with the game [33,34].

The PBL model’s application was clearly demonstrated through rewarding each student’s avatar with tangible rewards, translating these accomplishments into actual benefits within the game. The rewards, badges, and rankings only made sense and had an impact when the challenges were at the right level of complexity, which implied addressing tasks appropriately. The intrinsic link between the challenge and the reward made sure that gamification was not just fun but also taught students while motivating them [35].

2.4. Measurement Instruments

Perceived Locus of Causality Scale (PLOC-U): This questionnaire aims to measure student motivational regulation [36]. It consists of 20 items (Table 5). The 20 items are grouped into five factors (four items per factor) that measure IM, identified regulation (IdR), introjected regulation (IntR), ER, and Am. The Cronbach’s alpha values were IM (α = 0.62), IdR (α = 0.61), IntR (α = 0.80), ER (α = 0.81), and Am (α = 0.60) [36].

Table 5.

Perceived Locus of Causality Scale (PLOC-U).

2.5. Data Analysis

To perform the quantitative analysis, SPSS 24.0 software was used. Descriptive statistics of each variable were examined, presenting the mean and standard deviation. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data, revealing a non-normal distribution for all variables (p < 0.05). The Mann–Whitney U test was applied to identify differences between groups at the beginning and after the intervention between the GG and CG. Likewise, the Wilcoxon test was used to analyze changes within each group due to the intervention. A 95% confidence interval was calculated for differences, with the significance level set at p < 0.05. Using Microsoft Excel, the effect size (ES) was determined, classifying results as small (0.1–0.3), medium (>0.3–0.5), and large (>0.5) [37,38].

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Data

At the beginning of the study, baseline data were collected to ensure comparability between the gamified group (GG) and the control group (CG). The results showed no significant differences between GG and GC in any of the motivational regulations. This was determined using the Mann–Whitney U test, as summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison between gamified group (GG) and control group (CG) at pre-test using the Mann–Whitney U test (Av ± SD).

The initial analysis confirmed that the two groups were statistically equivalent at baseline, providing a sound basis for further comparisons.

3.2. Interaction Effect Test

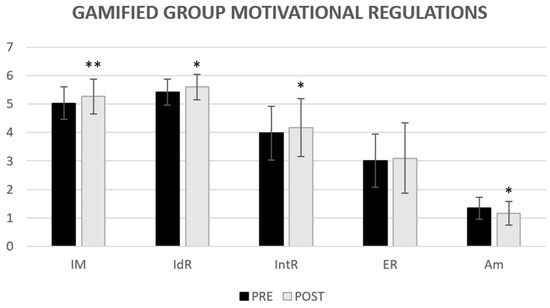

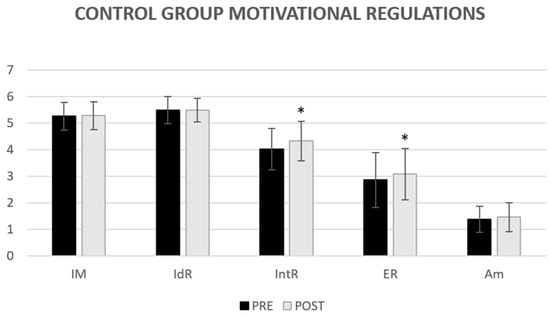

To evaluate the effectiveness of the implemented gamification intervention, the changes in motivational regulations in the group were compared using the Wilcoxon test (Table 7). The trends revealed in the results were that IM (Z = −2.793; p < 0.01; ES = 0.431), IdR (Z = −2.547; p = 0.011; ES = 0.393), and IntR (Z = −2.025; p = 0.043; ES = 0.312) in GG were significantly increased, while Am (Z = −2.593; p = 0.010; ES = 0.400) was significantly lowered (Figure 1). While analyzing the results, changes in CG including IntR (Z = 3.142; p < 0.01; ES = 0.574) and ER (Z = −2.035; p = 0.042; ES = 0.372) were been observed where CG showed a significant increase in both regulations (Figure 2).

Table 7.

Longitudinal comparison intra-group using the Wilcoxon test (Av ± SD posttest).

Figure 1.

Descriptive data of the motivational regulations for GG showing the changes produced between the pre- and posttest. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.001. IM = Intrinsic Motivation; IdR = Identified Regulation; IntR = Introjected Regulation; ER = External Regulation; Am = Amotivation.

Figure 2.

Descriptive data of the motivational regulations for CG, showing the changes produced between the pre- and post-test. *: p < 0.05. IM = Intrinsic Motivation; IdR = Identified Regulation; IntR = Introjected Regulation; ER = External Regulation; Am = Amotivation.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze the effects of a gamification intervention on physical activity and exercise science in university students, focusing on different motivational mechanisms.

The results supported hypothesis 1 (H1), as a significant increase in IM was observed in GG, while no changes were observed in CG. In a university context, Pérez-López et al. [18] found that responsibility and participation in university sports activities increased after the implementation of a gamification intervention. This suggests that gamification can create a more engaging and stimulating environment, influencing students’ IM by giving them more autonomy and involvement.

Similarly, a study by Castañeda-Vázquez et al. [19] discussed how gamification led to higher IM and improved academic performance. Similarly, Feliz-Valero et al. [20] improved students’ IM and reduced Am through a gamification approach. This suggests that implementing gaming elements in educational settings may be effective in promoting IM and alleviating students’ lack of motivation.

In secondary education, there are studies that show a link between gamification and improved IM in a physical activity context. In the study by Sotos-Martínez et al. [30], improvements in basic psychological needs and IM were found, suggesting that gamification can meet students’ psychological needs and promote greater motivation for physical activity. Similarly, studies by Fernández-Río et al. [3] and Real Pérez et al. [39] found significant improvements in IM.

These findings support the idea that gamification can be an effective strategy to improve students’ IM in the context of university physical education.

The results obtained did not support hypothesis 2 (H2), as increases in IdR and IntR occurred in GG, while increases in IntR and ER occurred in CG. Therefore, there were extrinsic motivation changes in both groups, although the changes occurred in different variables, showing different changes between both groups.

Previous research has found a relationship between the implementation of a gamified approach and higher extrinsic motivation and academic performance, as evidenced by the study of Castañeda-Vázquez et al. [19]. Similarly, Ferriz-Valero et al. [21], using the ClassCraft application in a gamified approach, found an increase in students’ ER, while IM remained stable. According to the authors, these results may be due to the implementation of extrinsic rewards outside the game itself, leading to a perception of extrinsic nature. Nevertheless, one article showed limitations in their methodology, lack of control group [19], and lack of probabilistic sampling [19]. Additionally, this increase in extrinsic motivation (IdR and IntR) in the GG may be due to the qualification information obtained from the activities performed. This information could be taken as an external stimulus to gamification. Thus, the increases in IdR and IntR in the GG observed in the present study may be due to the implementation of a PBL model with external rewards to the gamification itself (evaluation information), influencing students’ perception of the rewards received and therefore affecting their kind of motivation [21].

On the other hand, an unexpected finding appeared: increases in IntR and ER in the CG. These changes can be explained due to an external factor in the implementation of the gamified proposal, such as informing the students of the qualification obtained in the activities performed. So, these extrinsic motivational changes (IntR and ER improvements) may be due to the educational stage of the students, where they perceive that the obtained qualifications can have a greater impact on their future job prospects [21]. Furthermore, each group attended the intervention sessions at different time: the GG participates as their first subject and the CG participates after taking part in another subject. This different schedule may have influenced student motivation due to increased fatigue or decreased attention. Therefore, university students in CG may associate perceived motivation with an extrinsic characteristic, as obtaining a good qualification is the primary objective, which could be increased for changing the timetable for the sessions.

Therefore, the GG seemed to evade qualifications and enjoyed the process of participation in gamification more, leading to greater changes in self-determined motivation [5,40]. This suggests that external rewards and incentive systems can influence students’ extrinsic motivation, although it is important to consider how these elements can coexist with intrinsic motivation to optimize the learning process.

Finally, the results obtained support hypothesis 3 (H3), where a decrease in Am was observed in the GG students. In this line, Ferriz-Valero et al. [20] observed a significant improvement in intrinsic motivation and a corresponding reduction in amotivation among university students after implementing a gamified approach. This finding supports the theory of Ryan and Deci [5], who argued that as intrinsic motivation increases, amotivation tends to decrease. Research in other educational stages, conducted by Dolera-Montoya et al. [41] in primary school students and by Sotos-Martínez et al. [30] in secondary school students, also found a decrease in amotivation and an increase in intrinsic motivation after the implementation of gamified interventions at their respective educational levels.

These findings suggest that gamification strategies can be effective in reducing amotivation across different educational stages, highlighting their potential to promote greater engagement and participation of students in the learning process. Nevertheless, in order to obtain a deeper understanding of the effect of gamification on university students, more empirical studies are required to validate the observed results and extend the current findings since this methodology could promote more motivating teaching with active students.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be recognized. First, the sample size was relatively small (n = 72), consisting only of university students from the Physical Activity and Sports Sciences program. Therefore, this sample may not be representative of the wider university student population with reference to other subjects or university degrees, thus affecting the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the sample was collected from a single educational institution, which can make it difficult to extrapolate the sample to other educational institutions and other countries or contexts. Another possible limitation may be related to the novel effect of the gamified intervention, which was able to highlight the positive data obtained. Furthermore, the information obtained in the evaluation activities can be a limitation seen as an external input to the gamification itself. Finally, the different schedule for GG and CG could have affected the results obtained in the CG, as they were exhausted after another previous class. Granted, when studying university students’ behavior, we not only tested their motivation in the context of the experiment but also other contributors to the given educational environment.

Secondly, previous studies on the subject have certain limitations that may compromise the results obtained in these studies, including lack of a control group or lack of specification regarding the type of motivational regulation from which the changes were obtained. This absence of detailed differentiation in motivational types can obscure the nuanced understanding of how gamification affects various aspects of motivation. These limitations may have modified the results of the articles and thus the knowledge base for this article.

4.2. Future Research Directions

From our experiment, it can be seen that the effect of gamification on the motivational profile of university students is a good method of investigation due to the lack of studies and the limitations that previous research shows as well as the differences in results between the studies. It may be feasible to observe how gamification can affect the basic psychological needs of students, supporting the present results. Likewise, a qualitative research approach may be interesting for contrasting the results of the present study. It would be interesting to investigate the effects of a long-term gamified intervention in order to see the long-term effect of this teaching methodology on this population. Another line of future research could be based on comparing the impact of the different elements of gamification on motivation of students. Thus, it is proposed to extend options for its application by gradually increasing the scale and introducing the general innovative educational environment of the university in future experiments. Finally, and in order to be more extrapolatable, it would be interesting to observe if there are differences in the effect produced by gamification in university students according to gender and cultural factors.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this research highlights gamification as a viable strategy to increase the motivation of university students in the field of physical activity. Most articles, both in university and secondary education, have demonstrated an increase in student motivation when implementing gamified proposals, just like the present research.

The findings show a significant increase in intrinsic motivation and a reduction in amotivation in the experimental group, suggesting that the integration of gaming elements can create a more engaging and rewarding learning environment. Additionally, changes in extrinsic motivation were identified, and the introjected relationships were also identified in detail, emphasizing the need to carefully consider the implementation of incentives in gamified interventions and the educational stage in which gamification is implemented since it seems that the greater the formative stage, the greater the importance of tangible rewards and extrinsic motivation. The need for additional research is indicated since more information is needed related to the possible positive effects of gamified pedagogical proposals in motivation on subjects related to physical activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.-D.M. and A.F-V.; methodology, A.F.-V.; software, V.J.S.-M.; validation, M.S.-D.M.; formal analysis, V.J.S.-M.; investigation, V.J.S.-M.; resources, V.J.S.-M. and S.B.-M.; data curation, A.F.-V. and S.B.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.J.S.-M.; writing—review and editing, V.J.S.-M., A.F.-V. and S.B.-M.; visualization, V.J.S.-M. and A.F.-V.; supervision, A.F.-V. and S.B.-M.; project administration, S.B.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Alicante (UA-2022-05-24).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

This work contributes to the development of Victor Javier Sotos-Martínez’s doctoral thesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ssewanyana, D.; Abubakar, A.; van Baar, A.; Mwangala, P.N.; Newton, C.R. Perspectives on Underlying Factors for Unhealthy Diet and Sedentary Lifestyle of Adolescents at a Kenyan Coastal Setting. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniszewski, E.; Henrique, J.; de Oliveira, A.J.; Alvernaz, A.; Vianna, J.A. (A)Motivation in Physical Education Classes and Satisfaction of Competence, Autonomy and Relatedness. J. Phys. Educ. 2019, 30, e3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Rio, J.; de las Heras, E.; González, T.; Trillo, V.; Palomares, J. Gamification and Physical Education. Viability and Preliminary Views from Students and Teachers. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2020, 25, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J. A Classroom-Based Intervention to Help Teachers Decrease Students’ Amotivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 40, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berghe, L.; Tallir, I.B.; Cardon, G.; Aelterman, N.; Haerens, L. Student (Dis)Engagement and Need-Supportive Teaching Behavior: A Multi-Informant and Multilevel Approach. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2015, 37, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tanahi, N.; Soliman, M.; Abdel Hady, H.; Alfrehat, R.; Faid, R.; Abdelmoneim, M.; Torki, M.; Hamoudah, N. The Effectiveness of Gamification in Physical Education: A Systematic Review. IJEMST 2024, 12, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Outside-School Physical Activity Participation and Motivation in Physical Education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 84, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huotari, K.; Hamari, J. Defining gamification: A service marketing perspective. In Proceedings of the 16th International Academic MindTrek Conference on—MindTrek ’12, Tampere, Finland, 3–5 October 2012; ACM Press: Tampere, Finland, 2012; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Dichev, C.; Dicheva, D. Gamifying Education: What Is Known, What Is Believed and What Remains Uncertain: A Critical Review. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicheva, D.; Dichev, C.; Agre, G.; Angelova, G. Gamification in Education: A Systematic Mapping Study. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Cerero, J.; Mena-Guacas, A.F.; Reyes-Rebollo, M.M. Impact of Gamified Teaching on University Student Learning. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, K.; Sugantha Priya, M.; Saranya, S.; Gomathi, R.; Sam, D. E-Learning as a Desirable Form of Education in the Era of Society 5.0. In Advances in Distance Learning in Times of Pandemic; Rosak Szyrocka, J., Zywiolek, J., Nayyar, A., Naved, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, P.; Gokhale, P.; Satish, Y.M.; Tigadi, B. An Empirical Study on the Impact of Learning Theory on Gamification-Based Training Programs. Organ. Manag. J. 2022, 19, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, S.; Ryan, R.M. Glued to Games: How Video Games Draw Us in and Hold Us Spellbound; Greewood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 2011; ISBN 2-01-320653-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ferriz-Valero, A.; Agulló-Pomares, G.; Tortosa-Martínez, J. Benefits of Gamified Learning in Physical Education Students: A Systematic Review. Apunts 2023, 153, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintas, A.; Bustamante, J.C.; Pradas, F.; Castellar, C. Psychological Effects of Gamified Didactics with Exergames in Physical Education at Primary Schools: Results from a Natural Experiment. Comput. Educ. 2020, 152, 103874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, I.J.; Rivera García, E.; Trigueros Cervantes, C. “La profecía de los elegidos”: Un ejemplo de gamificación aplicado a la docencia universitaria / “The Prophecy of the Chosen Ones”: An Example of Gamification Applied to University Teaching. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. FÍSica Deporte 2017, 17, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Vázquez, C.; Espejo-Garcés, T.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Fernández-Revelles, A.B. Physical Education´s Teacher Training Program through Gaming, Ict and Continuous Assessment. Rev. Euroam. Cienc. Deporte 2019, 8, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriz-Valero, A.; García-Martínez, S.; García-Jaen, M.; Østerlie, O.; Sellés, S. Gamificación: Metodologías Activas En Educación Física En Docencia Universitaria. In Investigación e innovación en la Enseñanza Superior. Nuevos contextos, Nuevas Ideas; Editorial Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; pp. 1116–1126. ISBN 978-84-17667-23-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ferriz-Valero, A.; Østerlie, O.; García-Martínez, S.; García-Jaén, M. Gamification in Physical Education: Evaluation of Impact on Motivation and Academic Performance within Higher Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arufe-Giráldez, V. Fortnite EF, Un Nuevo Juego Deportivo Para El Aula de Educación Física. Propuesta de Innovación y Gamificación Basada En El Videojuego Fortnite. Sport. Sci. Tech. J. Sch. Sport Phys. Educ. Psychomot. 2019, 5, 323–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Aguilar, G.; Fernandez-Rio, J.; Prat-Grau, M. Gamificating Physical Education Pedagogy. College Students’ Feelings. Rev. Int. Med. Cienc. Act. Fis. Deporte 2021, 21, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero González, L.E.; Jiménez Jiménez, F.; Area Moreira, M. Beyond the Textbook. Gamification through ITC as an Innovative Alternative in Physical Education. Retos 2018, 34, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Rio, J.; Zumajo-Flores, M.; Flores-Aguilar, G. Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs and Intention to Be Physically Active after a Gamified Intervention Programme. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2022, 28, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Pascual, M.; Ferriz-Valero, A.; García-Martínez, S.; Baena-Morales, S. Gamification as a Pedagogical Model to Increase Motivation and Decrease Disruptive Behaviour in Physical Education. Children 2022, 9, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Moya, R.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J.; Chiva-Bartoll, O.; Capella-Peris, C. Achievement Motivation for Learning in Physical Education Students: Diverhealth. Interam. J. Psychol. (IJP) 2018, 52, 270–280. [Google Scholar]

- Grech, E.M.; Briguglio, M.; Said, E. A Field Experiment on Gamification of Physical Activity—Effects on Motivation and Steps. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2024, 184, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.T.; Stanley, J.C. Diseños Experimentales y Cuasiexperimentales en la Investigacion Social; Amorrortu: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sotos-Martínez, V.J.; Ferriz-Valero, A.; García-Martínez, S.; Tortosa-Martínez, J. The Effects of Gamification on the Motivation and Basic Psychological Needs of Secondary School Physical Education Students. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2022, 29, 160–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Martínez, V.J.; Tortosa-Martínez, J.; Baena-Morales, S.; Ferriz-Valero, A. Boosting Student’s Motivation through Gamification in Physical Education. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz, R.; Branquinho, L.; Sortwell, A.; Teixeira, J.E.; Forte, P.; Marinho, D.A. Teaching Models in Physical Education: Current and Future Perspectives. Montenegrin J. Sports Sci. Med. 2023, 19, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttfield-Addison, P.; Manning, J.; Nugent, T. A Better Recipe for Game Jams: Using the Mechanics Dynamics Aesthetics Framework for Planning. In Proceedings of the GJH&GC′16: Proceedings of the International Conference on Game Jams, Hackathons, and Game Creation Events, San Francisco, SA, USA, 13 March 2016; pp. 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Cristea, A.I.; Hadzidedic, S.; Dervishalidovic, N. Contextual Gamification of Social Interaction—Towards Increasing Motivation in Social e-Learning. In Advances in Web-Based Learning—ICWL 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y. Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards; Octalysis Media: Fremont, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-85-7811-079-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez De Miguel, M.; Lizaso, I.; Hermosilla, D.; Alcover, C.; Goudas, M.; Arranz-Freijó, E. Preliminary Validation of the Perceived Locus of Causality Scale for Academic Motivation in the Context of University Studies (PLOC-U). Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 87, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for The Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-85-7811-079-6. [Google Scholar]

- Coolican, H. Research Methods and Statistics in Psychology; Hooder: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Real-Pérez, M.; SánchezOliva, D.; Padilla-Moledo, C. Africa Project «La Leyenda de Faro»: Effects of a Methodology Based on Gamification on Situational Motivation about the Content of Corporal Expression in Secondary Education. Retos 2021, 42, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Martínez, V.J.; Tortosa-Martínez, J.; Baena-Morales, S.; Ferriz-Valero, A. It’s Game Time: Improving Basic Psychological Needs and Promoting Positive Behaviours through Gamification in Physical Education. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2023, 30, 1356336X231217404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolera-Montoya, S.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Jimenez-Parra, J.F.; Manzano-Sanchez, D. Improvement of the Classroom Climate through a Plan of Gamified Coexistence with Physical Activity: Study of Its Effectiveness in Primary Education. Multidiscip. J. Educ. 2021, 14, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).