A Qualitative Systematic Literature Review on Phonological Awareness in Preschoolers Supported by Information and Communication Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

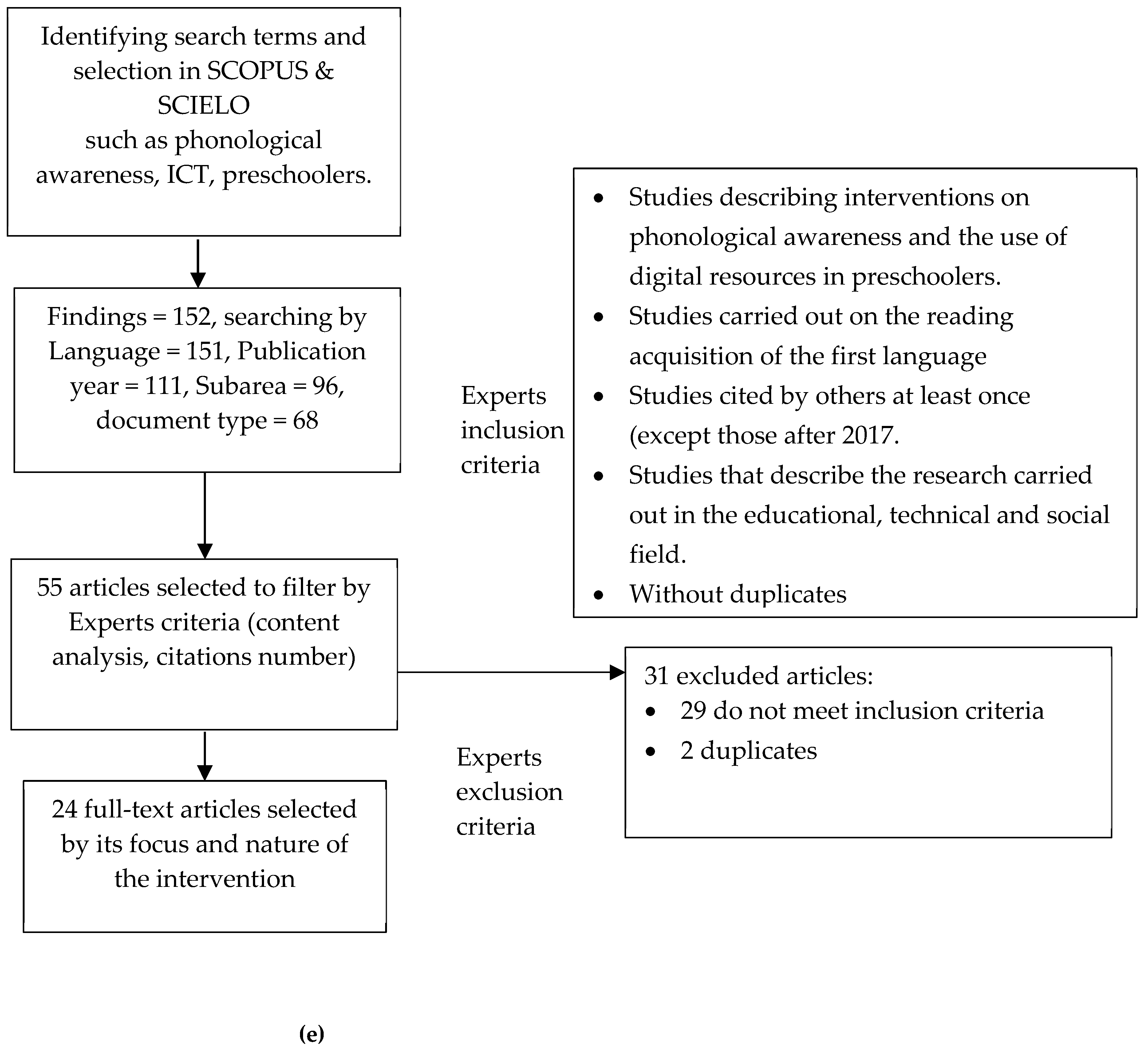

2. Methods

2.1. Search and Selection of Terms

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Studies reported in English, Spanish, and Portuguese languages only

- Updated electronic documents from the last ten years, between 2010 and 2020

- Studies available in full text, indexed articles, and online version

- Studies describing phonological awareness interventions and the use of digital resources in preschoolers

- Studies evaluating interventions carried out on the reading acquisition in first language

- Studies describing the research carried out in the educational, technical, and social field

- Studies cited by others at least once, except those after 2017 considering the existing period for publications’ acknowledgement

- Studies evaluating interventions carried out on the reading acquisition in second language

- Studies describing the research carried out in the health and physiological field.

- Theses, conference papers and abstracts available online.

- Studies not relevant to the research question.

2.3. Searching Process

2.3.1. Sub-String 1

2.3.2. Sub-String 2

2.3.3. Sub-String 3

2.3.4. Sub-String 4

2.4. Reporting Study Collection

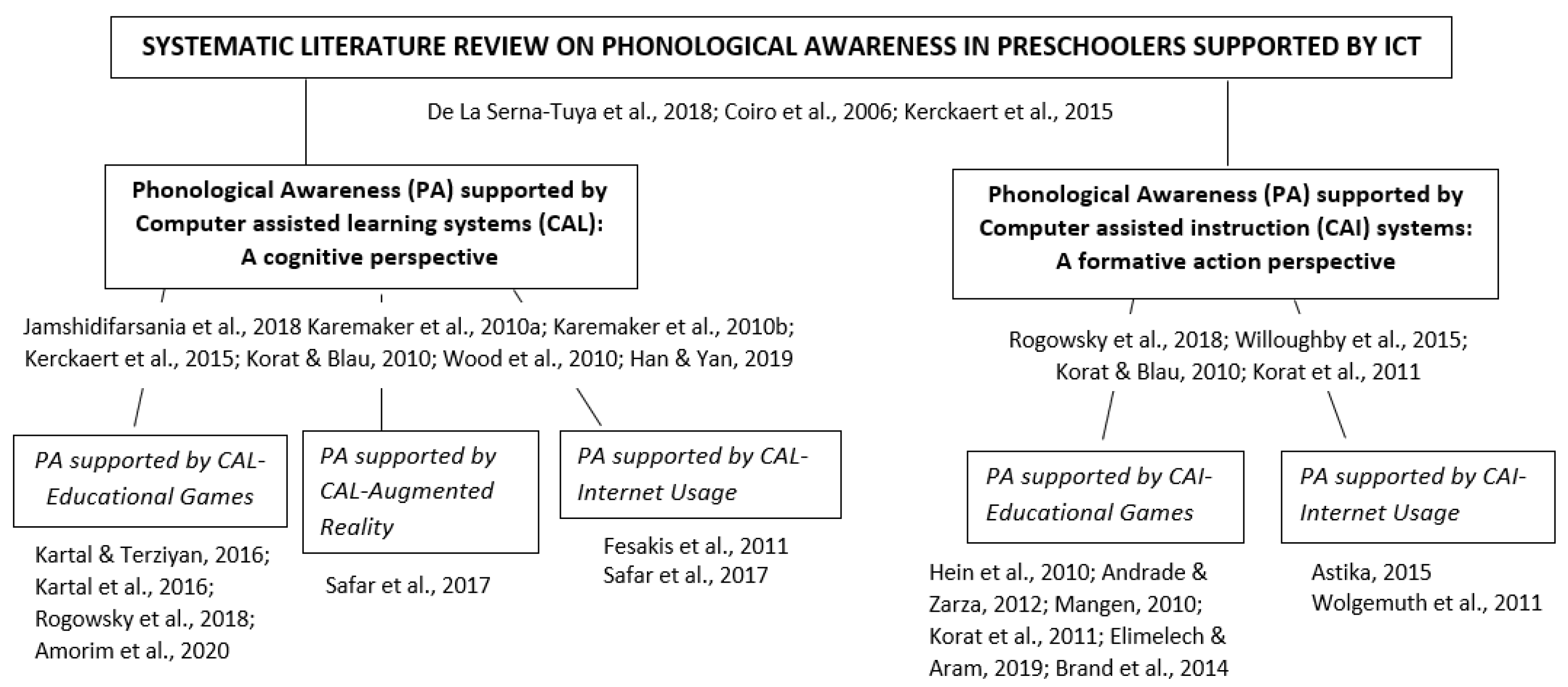

3. Results: Appraisal Narrative Synthesis

- Section 3.3. Category 1. Phonological Awareness supported by Computer assisted learning systems (CAL)—A cognitive perspective

- Section 3.4. Category 2: Phonological Awareness supported by Computer assisted instruction (CAI) systems—A formative action perspective.

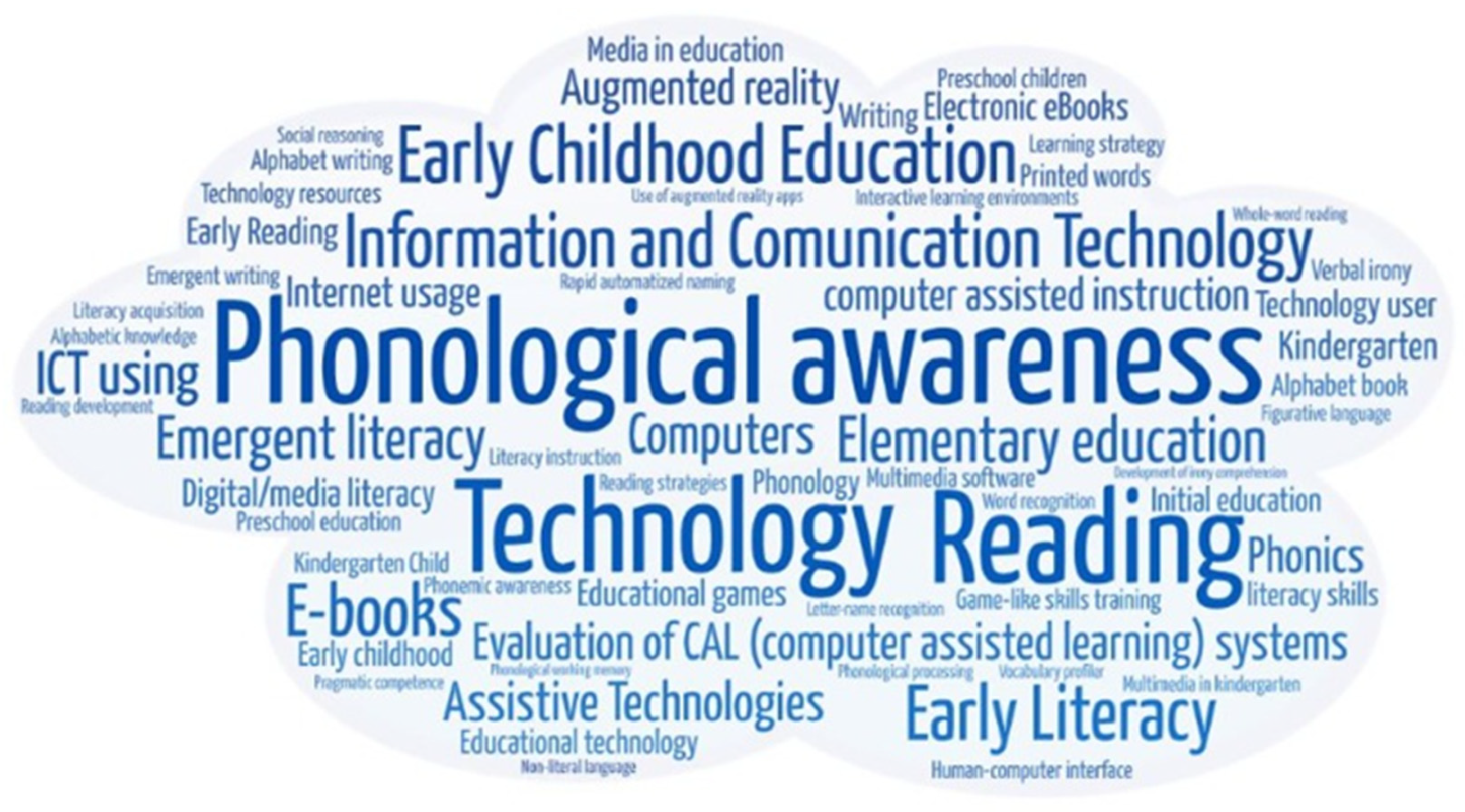

3.1. From a Word Cloud to Common Themes

3.2. CAL and CAI Considerations

3.3. A New Perspective of CAL and CAI

3.4. Category 1. Phonological Awareness Supported by Computer Assisted Learning Systems (CAL)—A Cognitive Perspective

- CAL-Educational Games

- CAL-Augmented Reality

- CAL-Internet Usage

3.4.1. Subcategory: Phonological Awareness Supported by CAL-Educational Games

3.4.2. Subcategory: Phonological Awareness Supported by CAL-Augmented Reality

3.4.3. Subcategory: Phonological Awareness Supported by CAL-Internet Usage

3.5. Category 2. Phonological Awareness Supported by Computer Assisted Instruction (CAI) Systems—A Formative Action Perspective

- CAI-Educational Games

- CAI-Internet Usage

3.5.1. Subcategory Phonological Awareness Supported by CAI-Educational Games

3.5.2. Subcategory Phonological Awareness Supported by CAI-Internet Usage

4. Conclusions and Limitations

- Category 2. Phonological Awareness supported by Computer assisted instruction (CAI) systems—A formative action perspective. In this category 11 research works denote similar advances: [17,18,23,25,34,36,41,42,43,44,45]. Notice that the works [17,34] are listed in both categories indicating their importance for the phonological awareness, having also 17 and 3 citations respectively in recent years.

- Subcategories emerge from the SRL and enrich the discussion supported on CAL and CAI systems: 1. Subcategories of Phonological Awareness supported by CAL/CAI Educational Games. 2. Subcategories of Phonological Awareness supported by CAL/CAI Internet Usage. 3. A subcategory of Phonological Awareness supported by CAL/AR.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. PRISMA 2020 Checklist

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | yes |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. | yes |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | yes |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | yes |

| METHODS | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | yes |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | yes |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. | yes |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | yes |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | yes |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | yes |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | yes | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | n/a |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. | n/a |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | yes |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | yes | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | yes | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | yes | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | n/a | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | n/a | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | n/a |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | n/a |

| RESULTS | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | yes |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | yes | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present its characteristics. | yes |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. | n/a |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | n/a |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | n/a |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | n/a | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | n/a | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | n/a | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | n/a |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | n/a |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | yes |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | yes | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | yes | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | yes | |

| OTHER INFORMATION | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | n/a |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | n/a | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | n/a | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | yes |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | yes |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | yes |

Appendix B. Search Terms Definitions

- <phonological awareness>: Phonological awareness (PA) is the understanding of different ways that oral language can be divided into smaller components and manipulated [42], i.e., having capabilities such as isolating, identifying, segmenting, blending, deleting, adding, or substituting the sounds of the smaller units of language such as word, syllable, onset, rime and individual phonemes.

- <children or preschoolers>: Children who are no longer babies but are not yet old enough to go to school are sometimes referred to as preschoolers Taken from. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/es/diccionario/ingles/preschooler (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <digital resources>: can be defined as materials that have been conceived and created digitally or by converting analogue materials to a digital format.Taken from https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/Digital%20resources%20CRDP.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <ICT support>: Information and communications technology (or technologies) support, is the infrastructure and components that enable modern computing. Although there is no single, universal definition of ICT, the term is generally accepted to mean all devices, networking components, applications and systems that combined allow people and organizations (i.e., businesses, nonprofit agencies, governments and criminal enterprises) to interact in the digital world.Taken from: https://www.techtarget.com/searchcio/definition/ICT-information-and-communications-technology-or-technologies (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <conventional digital resources>: the authors proposed this term definition as those digital resources commonly used by learners in the last decade.

- <assessment syllabic awareness>: it is meant by the Phonological Awareness Assessment which objective is recognise a word in a sentence showing the ability to segment a sentence, recognise a rhyme, identify words that have the same ending sounds, recognise a syllable to separate or blend words the way that they are pronounced.Taken from: https://www.readingrockets.org/article/phonological-awareness-assessment (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <kid(s)>: Young people who are no longer children are sometimes referred to as kids. Taken from https://www.collinsdictionary.com/es/diccionario/ingles/kid (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <educational technology>: Educational technology refers to technology that usually helps facilitate collaboration in an active learning environment. Taken from https://tophat.com/glossary/e/educational-technology/ (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <emergent digital resources>: the authors proposed this term definition as those digital resources rarely used by learners in the last three years.

- <disorders>: to disturb the order of.Taken from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/disorder (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <assessment phonemic awareness>: An informal assessment of phonemic awareness, including what the assessment measures, when is should be assessed, examples of questions, and the age or grade at which the assessment should be mastered.Taken from: https://www.readingrockets.org/article/phonemic-awareness-assessment (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <digital resource support>: The term ‘digital learning resource’ is used here to refer to materials included in the context of a course that support the learner’s achievement of the described learning goals.Taken from: https://flexiblelearning.auckland.ac.nz/learning_technologies_online/6/1/html/course_files/1_1.html (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <ICT support>: Information and communications technology (or technologies) support, is the infrastructure and components that enable modern computing. Although there is no single, universal definition of ICT, the term is generally accepted to mean all devices, networking components, applications and systems that combined allow people and organizations (i.e., businesses, nonprofit agencies, governments, and criminal enterprises) to interact in the digital world.Taken from: https://www.techtarget.com/searchcio/definition/ICT-information-and-communications-technology-or-technologies (accessed on 14 April 2022)

- <dyslexia>: Dyslexia is a general term for primary reading disorder. Diagnosis is based on intellectual, educational, speech and language, medical, and psychologic evaluations. Treatment is primarily educational management, consisting of instruction in word recognition and component skills.Taken from: https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/learning-and-developmental-disorders/dyslexia (accessed on 14 April 2022)

References

- Corriveau, K.H.; Goswami, U.; Thomson, J.M. Auditory Processing and Early Literacy Skills in a Preschool and Kindergarten Population. J. Learn. Disabil. 2010, 43, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cara, B.; Goswami, U. Phonological neighbourhood density: Effects in a rhyme awareness task in five-year-old children. J. Child Lang. 2003, 30, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, U.; Bryant, P.E. Phonological Skills and Learning to Read; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Más de la Mitad de los Niños y Adolescentes en el Mundo no Está Aprendiendo; Instituto de Estadística, 2017; Available online: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs46-more-than-half-children-not-learning-2017-sp.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Llorente, A. 4 Cifras Sobre la Alfabetización en América Latina Que Quizá te Sorprendan; BBC News Mundo, 2018; Available online: www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-45453102 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Pufpaff, L. A developmental continuum of phonological sensitivity skills. Psychol. Sch. 2009, 46, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, S. The Development of Phonological Awareness in Young Children: Examining the Effectiveness of a Phonological Program; University of Nebraska: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Katzir, T.; Schiff, R.; Kim, Y. The effects of orthographic consistency on reading development: A within and between cross-linguistic study of fluency and accuracy among fourth grade English- and Hebrew-speaking children. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiman, R. Learning to spell: Phonology and beyond. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2017, 34, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautala, J.; Heikkilä, R.; Nieminen, L.; Rantanen, V.; Latvala, J.-M.; Richardson, U. Identification of Reading Difficulties by a Digital Game-Based Assessment Technology. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2020, 58, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Serna-Tuya, A.S.; González-Calleros, J.M.; Rangel, Y.N. Las Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en el preescolar: Una revisión bibliográfica. Campus Virtuales 2018, 7, 19–31. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/6369898.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Cheung, A.C.; Slavin, R.E. Effects of educational technology applications on reading outcomes for struggling readers: A best-evidence synthesis. Read. Res. Q. 2013, 48, 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, M.; Fletcher, B.; Falenchuk, O.; Brunsek, A.; McMullen, E.; Shah, P.S. Child-staff ratios in early childhood education and care settings and child outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12, e0170256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.A.; Habib, M.; Onnis, L. Technology-Based Tools for English Literacy Intervention: Examining Intervention Grain Size and Individual Differences. Front. Psychol. 2019, 1, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karemaker, A.M.; Pitchford, N.J.; O’Malley, C. Does whole-word multimedia software support literacy acquisition? Read. Writ. 2010, 23, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karemaker, A.; Pitchford, N.J.; O’Malley, C. Enhanced recognition of written words and enjoyment of reading in struggling beginner readers through whole-word multimedia software. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowsky, B.A.; Terwilliger, C.C.; Young, C.A.; Kribbs, E.E. Playful learning with technology: The effect of computer assisted instruction on literacy and numeracy skills of preschoolers. Int. J. Play 2018, 16, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elimelech, A.; Aram, D. Using a Digital Spelling Game for Promoting Alphabetic Knowledge of Preschoolers: The Contribution of Auditory and Visual Supports. Read. Res. Q. 2019, 55, 235–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, J. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care; CRD, University of York: York, UK, 2009; Available online: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Galvan, J.L.; Galvan, M.C. Writing Literature Reviews: A Guide for Students of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 7th ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halabi-Echeverry, A. Comprehensive RSL Worksheet. NextPort vCoE Online Course. 2019. Available online: www.nextport.com.co (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Hein, J.M.; Teixeira, M.C.T.V.; Seabra, A.G.; De Macedo, E.C. Avaliação da eficácia do software “alfabetização fônica” para alunos com deficiência mental. Rev. Bras. De Educ. Espec. 2010, 16, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, J.; Rayner, K. Reading in alphabetic writing systems: Evidence from cognitive neuroscience. In Neuroscience in Education: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly; Oxford Scholarship Online: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, D.; Evans, M.A.; Nowak, S. Do ABC eBooks boost engagement and learning in pre-schoolers? An experimental study comparing eBooks with paper ABC and storybook controls. Comput. Educ. 2015, 82, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerckaert, S.; Vanderlinde, R.; Van Braak, J. The role of ICT in early childhood education: Scale development and research on ICT use and influencing factors. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 23, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.; Pillinger, C.; Jackson, E. Understanding the nature and impact of young readers’ literacy interactions with talking books and during adult reading support. Comput. Educ. 2010, 54, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safar, A.H.; Al-Jafar, A.A.; Al-Yousefi, Z.H. The effectiveness of using augmented reality apps in teaching the English alphabet to kindergarten children: A case study in the state of Kuwait. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, T.; Plaisant, C.; Vuillemot, R. The Story of One: Humanity Scholarship with Visualization and text Analysis (Tech Report HCIL-2008-33); University of Maryland, Human-Computer Interaction Lab: College Park, MD, USA, 2008; Available online: http://www.cs.umd.edu/hcil/trs/2008-33/2008-33.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- McNaught, C.; Lam, P. Using Wordle as a Supplementary Research Tool. Qual. Rep. 2010, 15, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartelli, A. The Implementation of Practices with ICT as a New Teaching-Learning Paradigm. In Encyclopedia of Information Communication Technology; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiro, J.; Klein, R.A.; Walpole, S. Critically evaluating educational technologies for literacy learning: Current trends and new paradigms. In International Handbook of Literacy and Technology; McKenna, M., Labbo, L., Kieffer, R., Reinking, D., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidifarsania, H.; Garbayab, S.; Limc, T.; Blazevica, P.; Ritchie, J.R. Technology-Based Reading Intervention Programs for Elementary Grades: An Analytical Review. Comput. Educ. 2018, 1, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korat, O.; Blau, H. Repeated reading of CD-ROM storybook as a support for emergent literacy: A developmental perspective in two SES groups. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2010, 43, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yan, H. Book or screen? a preliminary study on preschool children’s reading and ICT using behaviours. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 667–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korat, O.; Shamir, A.; Arbiv, L. E-books as support for emergent writing with and without adult assistance. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2011, 16, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, G.; Terziyan, T. Development and evaluation of game-like phonological awareness software for kindergarteners: JerenAli. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2016, 53, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, G.; Babür, N.; Erçetin, G. Training for phonological awareness in an orthographically transparent language in two different modalities. Read. Writ. Q. 2016, 32, 550–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, A.N.; Jeon, L.; Abel, Y.; Felisberto, E.F.; Barbosa, L.N.F.; Dias, N.M. Using Escribo Play Video Games to Improve Phonological Awareness, Early Reading, and Writing in Preschool. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesakis, G.; Sofroniou, C.; Mavroudi, E. Using the Internet for Communicative Learning Activities in Kindergarten: The Case of the “Shapes Planet”. Early Child. Educ. J. 2011, 38, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.S.; Zarza, F.V. Las lenguas indígenas y las tecnologías de información y comunicación. Rev. Int. Linguística Iberoam. 2012, 10, 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mangen, A. Point and click: Theoretical and phenomenological reflections on the digitization of early childhood education. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2010, 11, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.T.; Marchand, J.; Lilly, E.; Child, M. Home-School Literacy Bags for Twenty-first Century Preschoolers. Early Child. Educ. J. 2014, 42, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astika, G. Profiling the vocabulary of news texts as capacity building for language teachers. Indones. J. Appl. Linguist. 2015, 4, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wolgemuth, J.; Savage, R.; Helmer, J.; Lea, T.; Harper, H.; Chalkiti, K.; Bottrell, C.; Abrami, P. Using computer-based instruction to improve Indigenous early literacy in Northern Australia: A quasi-experimental study. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2011, 27, 727–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interventions | Population | Outcomes | Comparisons | Exclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major terms <phonological awareness> | <children or preschoolers> | <digital resources or ICT support> | <conventional digital resources> | <learning disabilities> |

| Smaller terms | ||||

| assessment syllabic awareness | kids | educational technology | emergent digital resources | disorders |

| assessment phonemic awareness | ICT support | digital resource support | dyslexia |

| Findings | Language | Pub Year | Subarea | Doctype | Title-Abs-Key (Scopus Output) | Citations Expert Criteria 1 | Yes and/Yes but Expert Criteria 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SubString 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| SubString 2 | 59 | 59 | 44 | 36 | 29 | 23 | 21 | 7 |

| SubString 3 | 52 | 52 | 46 | 39 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 6 |

| SubString 4 | 38 | 37 | 18 | 18 | 14 | 11 | 11 | 9 |

| Total | 152 | 151 | 111 | 96 | 68 | 59 | 55 | 24 |

| Author, Year | Tittle | Journal | Technological Resources | Database N° Citations | Keywords | Category * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hein, J.M.; Teixeira, M.C.T.V.; Seabra, A.G. & de Macedo, E.C. (2010) | Avaliação da eficácia do software “alfabetização fônica” para alunos com deficiência mental | Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 16(1), 65–82 | Educational Software | Scopus 1 | Intellectual disability; Phonological awareness; Reading Technology | CAI |

| Karemaker, A.M.; Pitchford, N.J. & O’Malley, C. (2010a) | Does whole-word multimedia software support literacy acquisition? | Reading and Writing. 23(1), 31–51 | Multimedia Software | Scopus 11 | ICT; Intervention; Literacy acquisition; Multimedia software; Whole word reading | CAL |

| Karemaker, A.; Pitchford, N.J. & O’Malley, C. (2010b) | Enhanced recognition of written words and enjoyment of reading in struggling beginner readers through whole-word multimedia software | Computers and Education, 54(1) 199–208 | Multimedia Software | Scopus 26 | Evaluation of CAL systems; Improving classroom teaching | CAL |

| Korat, O. & Blau, H. (2010) | Repeated reading of CD-ROM storybook as a support for emergent literacy: A developmental perspective in two SES groups | Journal of Educational Computing Research, 43(4), 445–466 | CD-ROM | Scopus 17 | __ | CAL-CAI |

| Mangen, A. (2010) | Point and click: Theoretical and phenomenological reflections on the digitization of early childhood education | Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 11(4), 415–431 | Computer Games | Scopus 14 | Nursery School; Early Childhood Education; Kindergarten | CAL |

| Wood, C.; Pillinger, C. & Jackson, E. (2010) | Understanding the nature and impact of young readers’ literacy interactions with talking books and during adult reading support | Computers and Education, 54(1), 199–208 | e-Book | Scopus 26 | Applications in subject areas; Elementary education; Evaluation of CAL systems; Interactional style; Reading strategies | CAL |

| Fesakis G.; Sofroniou C. & Mavroudi E. (2011) | Using the Internet for Communicative Learning Activities in Kindergarten: The Case of the “Shapes Planet” | Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 38(5), 385–392 | Website | Scopus 8 | Educational design; Geometry education; Information and Communication Technologies (ICT); Internet; Kindergarten | CAL |

| Korat, O.; Shamir, A. & Arbiv, L. (2011) | E-books as support for emergent writing with and without adult assistance | Education and Information Technologies, 16(3), 301–318 | e-Book | Scopus 16 | E-books-/Emergent writing-/Letter-name recognition-/Phonological awareness-/ | CAI |

| Wolgemuth, J.; Savage, R.; Helmer, J.; Lea, T.; Harper, H.; Chalkiti, K.; Bottrell, C. & Abrami, P. (2011) | Using computer-based instruction to improve Indigenous early literacy in Northern Australia: A quasi-experimental study | Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(4), 727–750 | Website | Scopus 19 | --- | CAI |

| Andrade, E.S. & Zarza, F.V. (2012) | Las lenguas indígenas y las tecnologías de información y comunicación | Revista Internacional de Lingüística Iberoamericana, 10(1), 149–165 | Educational Software | Scopus 1 | Applied linguistics; Indigenous languages; Information and communication technologies; Modernization; Purepecha | CAI |

| Coiro, J.; Klein, R.A. & Walpole, S. (2013) | Critically evaluating educational technologies for literacy learning: Current trends and new paradigms | International Handbook of Literacy and Technology, 2(1), 145–161 | Educational Technologies | Scopus 3 | General | |

| Brand, S.T.; Marchand, J.; Lilly, E. & Child, M. (2014) | Home-School Literacy Bags for Twenty-first Century Pre-schoolers | Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(3), 163–170 | Scopus 3 | Emergent literacy; School-family connections; Technology | CAI | |

| Astika, G. (2015) | Profiling the vocabulary of news texts as capacity building for language teachers | Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 123–134. | Website | Scopus 1 | Capacity building; Learning strategy; Vocabulary profiler | CAI |

| Kerckaert S.; Vanderlinde R. & Van Braak J. (2015) | The role of ICT in early childhood education: Scale development and research on ICT use and influencing factors | European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 23 (2), 183–199 | ICT | Scopus 26 | Early childhood education-ICT-professional development-scale development-technology use | General |

| Willoughby, D., Evans, M.A. & Nowak, S. (2015) | Do ABC eBooks boost engagement and learning in pre-schoolers? An experimental study comparing eBooks with paper ABC and storybook controls | Computers and Education, 82(1), 107–117 | e-Books. | Scopus 32 | Alphabet books; Alphabetic knowledge; Electronic eBooks; Emergent literacy; Literacy instruction | CAI |

| Kartal, G. & Terziyan, T. (2016) | Development and evaluation of game-like phonological awareness software for kindergarteners: JerenAli | Journal of Educational Computing Research, 53(4), 519–539 | Game-like software | Scopus 7 | Early Reading; game like skills training; multimedia in kindergarten; phonological awareness | CAL |

| Kartal, G.; Babür, N. & Erçetin, G. (2016) | Training for Phonological Awareness in an Orthographically Transparent Language in Two Different Modalities | Reading and Writing Quarterly, 32(6), 550–579 | Game-like software | Scopus 1 | __ | CAL |

| Safar A.H.; Al-Jafar A.A. & Al-Yousefi Z.H (2017) | The effectiveness of using augmented reality apps in teaching the English alphabet to kindergarten children: A case study in the state of Kuwait | Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(2), 417–440 | Augmented Reality | Scopus 18 | Augmented reality; Educational effectiveness; Information and communication technology (ICT); Kindergarten children; Use of augmented reality apps | CAL |

| De La Serna-Tuya A.S.; González-Calleros J.M. & Rangel Y.N. (2018) | Las Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación en el preescolar: Una revisión bibliográfica (Spanish only) | Campus Virtuales, 7(1), 19–31 | ICT | Scopus 4 | Family; Initial education; Literature review; Mediation; Methodology; Preschool education; Technology resources | General |

| Rogowsky, B.A.; Terwilliger, C.C.; Young, C.A. & Kribbs, E.E. (2018) | Playful learning with technology: the effect of computer-assisted instruction on literacy and numeracy skills of pre-schoolers | International Journal of Play, 7(1), 60–80 | Game-like software in tablets | Scopus 3 | Computer-assisted instruction; Early childhood education; literacy skills; numeracy skills; technology | CAL-CAI |

| Han, Y. & Yan, H. (2019) | Book or screen? a preliminary study on preschool children’s reading and ICT using behaviours | Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 56(1), 667–668 | e-Books | Scopus 0 | ICT using/parent–child information behaviour/Preschool children/reading | CAL |

| Jamshidifarsani, H.; Garbaya, S., Lim, T.; Blazevic, P. & Ritchie, J.M. (2019) | Technology-based reading intervention programs for elementary grades: An analytical review | Computers and Education, 128, 427–451 | ICT | Scopus 10 | Elementary education; Evaluation of CAL systems; Human-computer interface; Interactive learning environments; Media in education | CAL |

| Amorim, A.N.; Jeon, L.; Abel, Y.; Felisberto, E.F.; Barbosa, L.N.F. & Dias, N.M. (2020) | Using Escribo Play Video Games to Improve Phonological Awareness, Early Reading, and Writing in Preschool | Educational Researcher, 49(3), 188–197 | Escribo Play Video Game | Scopus 0 | Correlational analysis; early childhood; early literacy; educational games; educational technology; effect size; experimental design; instructional technologies; language comprehension; development; multisite studies; phonological awareness; reading | CAL |

| Elimelech, A. & Aram, D. (2020) | Using a Digital Spelling Game for Promoting Alphabetic Knowledge of Preschoolers: The Contribution of Auditory and Visual Supports | Reading Research Quarterly, 55 (2), 235–250 | Orthographic-Specific Game | Scopus 1 | Early childhood; ANOVAs; Assistive Technologies; Computers; Developmental Theories; Digital media literacy; Early Literacy; Literary Theory; Phonics; phonemic awareness; phonological awareness; Writing | CAI |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Otoya, F.A.; Raposo-Rivas, M.; Halabi-Echeverry, A.X. A Qualitative Systematic Literature Review on Phonological Awareness in Preschoolers Supported by Information and Communication Technologies. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060382

Fernández-Otoya FA, Raposo-Rivas M, Halabi-Echeverry AX. A Qualitative Systematic Literature Review on Phonological Awareness in Preschoolers Supported by Information and Communication Technologies. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(6):382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060382

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Otoya, Fiorela A., Manuela Raposo-Rivas, and Ana X. Halabi-Echeverry. 2022. "A Qualitative Systematic Literature Review on Phonological Awareness in Preschoolers Supported by Information and Communication Technologies" Education Sciences 12, no. 6: 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060382

APA StyleFernández-Otoya, F. A., Raposo-Rivas, M., & Halabi-Echeverry, A. X. (2022). A Qualitative Systematic Literature Review on Phonological Awareness in Preschoolers Supported by Information and Communication Technologies. Education Sciences, 12(6), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12060382