Abstract

The concept of teacher wellbeing, the importance of considering teacher wellbeing, concerns for developing digital wellbeing and concerns for using digital technologies to support teaching practices have all been previously studied. The idea that uses of digital technologies can support teacher wellbeing (or not) and ways that uses might do this have not been studied to the same extent. Indeed, it can be argued that this topic requires a complete and focused area of study in its own right. This methodologically focused paper takes an initial step in this direction, exploring existing research and backgrounds to wellbeing, teacher wellbeing, digital wellbeing and uses of digital technologies to support teachers’ practices. The paper reviews conceptions of digital technologies supporting teacher wellbeing and offers a newly developed outline conceptual model and framework for this research field. The framework is tested, identifying influencing factors from evidence presented in a number of existing relevant case studies where digital technologies have been used to support teacher practices. The efficacy of the proposed framework is assessed, and the paper concludes by offering a proposed research instrument and strategy to advance knowledge in this area.

1. Introduction

Teacher wellbeing is highlighted as a topic of concern in education. While using digital technologies is highlighted as an important need for teachers, the link between uses of digital technologies and how they might positively support teacher wellbeing has received limited research attention to date. Acknowledging these two important concerns (teacher wellbeing, and using digital technologies to support teaching and learning), it is crucial that we consider how to gather research evidence about uses of digital technologies that might positively support teacher wellbeing. This paper takes a step in that direction in this newly formulated area of research.

This is a conceptual paper, where the study detailed uses an inductive approach to initially develop an outline model and framework of features and factors that can influence teacher wellbeing when teachers use digital technologies. The framework is then developed further to derive a structured data collection instrument.

The paper begins by providing an overview and rationale for undertaking this focus and development, an overview of relevant literature on wellbeing, and how this is related to literature on teacher wellbeing, digital wellbeing, effective uses of digital technologies for teaching and learning, digital literacy, and digital agency. Features and factors that could influence teacher wellbeing when teachers use digital technologies, drawing on findings from the literature review, are identified and formulated as a framework. The efficacy of the proposed framework is assessed, by relating its features to a selected range of existing case studies that report teacher uses of digital technologies in specific but different contexts and situations. The findings of this efficacy review support a proposed data collection instrument that can be used to gather evidence about teacher wellbeing when teachers are using digital technologies.

The idea of digital technologies having a positive influence on teacher wellbeing is often overshadowed in the literature by reports of negative influences. For example, cyberbullying of teachers by students and parents has been reported in the media [1], as have problems associated with email overload [2]. At a policy level, it is often the negative influences of increasing uses of digital technologies on children and young people’s wellbeing that have been considered fundamentally. For example, in a briefing paper [3] for the House of Lords in the United Kingdom (UK), negative effects were highlighted through a stated focus on “issues of: cyberbullying; the use of social media; and screen time” (p. 1).

In a research overview, Mackin [4], looking at the effects from an adolescent perspective, highlights other potentially negative effects on learning that have been raised in a range of previous studies: mental health problems, ‘shallower engagement with written material’, shortening of attention spans, reducing reliance on memory, and sleep disruption (p. S138-9). Anderson and Rainie [5] share and categorise other concerns from a range of respondents as “digital deficits; digital addiction; digital distrust/divisiveness; digital duress; and digital dangers” (p. 3). These issues may certainly be identified by teachers, but they might also be fundamentally associated with certain approaches to and management of teaching. Indeed, Harding et al. [6], from their study of 3215 12-13-year-old students and 1182 teachers, pointed to this, in concluding that teacher wellbeing affected by student wellbeing and distress could “be partially explained by teacher presenteeism and quality of teacher-student relationships” (p. 460). In contrast, the effects of digital technologies on learning can be positive, and according to Mackin [4], there is as yet insufficient evidence about impacts on mental processes. However, ways that digital technologies are used can affect mental processes; as Howard-Jones [7] says in his report on the impact of digital technologies on human wellbeing, “it is how specific applications are created and used (by who, when and what for) that determine their impact” (p. 7). Although this report [7] is not specifically focused on teachers and their practices, the author does recommend that “[m]ore research is needed in a number of areas, to help evaluate the risks and potential benefits for healthy development presented by the new technologies and their applications” (p. 8).

In exploring teacher uses of digital technologies and how teachers’ activities and actions might be leading to teacher wellbeing outcomes, there are a number of salient background concepts and practices to consider. Some background concepts are specifically associated with digital technologies while others are concerned with teacher wellbeing at a wider level. The concept of teacher wellbeing and the importance of teacher wellbeing on a wider level have both been studied in some depth (for example, [8,9]). Concerns about appropriate uses of technologies by teachers in their teaching practices have also been studied in some depth, while practices that teachers can usefully adopt and implement have been explored through conceptions of digital literacy. A range of studies have focused on the digital literacy of teachers (for example, [10,11]), others on the digital agency of teachers (for example, [12,13]), yet others on digital wellbeing that includes teachers (for example, [14,15]) and finally others on uses of technologies by teachers to support effective and specific teaching and learning outcomes (for example, [16,17]).

However, the concept and ways that outcomes of uses of digital technologies might support teacher wellbeing (or not) have not been studied to the same extent. One article that has explored this concept offers an innovative technology adoption development perspective [18] and provides a conceptual framework in order to study teacher wellbeing in this context. Looking at evidence of outcomes on teacher wellbeing when digital technologies are used is not the approach taken by these authors, but one study that has focused on evidence of outcomes [19] explores the effect of home-school communication on teacher wellbeing, as it is recognised that relationships with parents can have both positive and negative effects on teacher wellbeing. The study gathered evidence from 400 parents and 80 teachers in Finland. The authors identified three categories of communication between schools and homes, where effects on teacher wellbeing could arise. The most commonly used was ‘study-related matters’ (n = 188) that included items such as ‘homework, test dates, evaluation, and absences’. This was followed by ‘behavioral issues’ (n = 58) that included items such as ‘continuous misbehavior and infrequent misbehavior’, and lastly ‘sensitive issues’ (n = 51) that included items such as ‘conflicts and health matters’ (p. 5). The study found that, overall, “parents and teachers expressed the need for more balanced and encouraging feedback on pupils. It appears from our results that there is too much emphasis still on a child’s weaknesses” (p. 6). Whilst this study highlights the need to select digital technologies and their uses appropriately and that the management of the communication can be critical, and whilst ways to support more positive relationships that would lead to more positive teacher wellbeing are suggested, the study does not identify any specific outcomes relating to features or factors that have influenced teachers in their reported wellbeing.

Recent events, brought about by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, where many teachers have been asked to support their pupils and students through online practices, have opened up ideas for uses of digital technologies to many teachers who had not used these previously [20,21]. The outcomes of this shift in terms of teacher wellbeing are not yet known in detail, but it is clear that such practices can support teacher wellbeing in terms of general health; online practices can support social distancing [22]. In contrast to some extent, a recent University College London (UCL) review of research literature [23] suggested that schools have not been shown in the past to have had major impacts on the spread of viral infections and that schools could for economic and social reasons be opened earlier than had been suggested by others. More recently, researchers (including those at Imperial College London) have questioned findings and recommendations from an alternative scientific perspective [24], contending whether comparing previous viral epidemics and pandemics offers a reliable perspective about possible impacts of this current pandemic. While our children and youth may be more resistant on the whole to the most severe symptoms arising from infection [25], our older populations (which include teachers) will certainly be at greater risk. Classrooms are restricted spaces; they are areas where individuals may well have difficulty in maintaining sufficient social distance (particularly where younger children are involved). Additionally, airborne spread may well be supported by airflow patterns that are set up through movements within these spaces. To address this dilemma, there are schools that have continued to maintain teaching and learning in difficult circumstances, using digital technology to its best effect—to support communication as well as to support viable teacher and pupil interactions, providing a basis for continued teaching and learning.

Therefore, what evidence do we have that digital technology can support teacher wellbeing, and in what situations is this happening, or not? This paper provides an initial overview and then takes a strategic approach to its exploration. The paper is not intended to provide detailed quantitative insight; it offers a strategic perspective for future action.

2. A Literature Review

In this section, literature in a number of related, pertinent areas is reviewed. The areas considered are wellbeing, teacher wellbeing, digital wellbeing, effective uses of digital technologies for teaching and learning, digital literacy, and digital agency. The reviews will highlight features and factors that influence teacher wellbeing when using digital technologies, and these will be drawn together as a framework in the section following (Section 3).

2.1. Wellbeing

The self-determination theory, proposed in the seminal paper of Ryan and Deci [26], provides a conceptual basis for considering wellbeing in a wide sense. Within that paper, the authors identified three important needs—competence, relatedness and autonomy—which, as they said “appear to be essential for facilitating optimal functioning of the natural propensities for growth and integration, as well as for constructive social development and personal well-being” (p. 68). In this paper, the focus is on the ways that digital technologies may affect teacher wellbeing. Taking Ryan and Deci’s three needs into consideration in a teacher practice context, the reviewed literature areas that follow relate to these needs and describe teacher wellbeing, digital wellbeing, effective uses of digital technologies for teaching and learning, digital literacy, and digital agency, all areas that offer varied perspectives. These areas certainly relate to Ryan and Deci’s three needs, but the relationship is not necessarily simple to map, as overlaps arise between and across these areas. However, within the review that follows, it is possible to see that teacher wellbeing is related to all three needs of competence, relatedness and autonomy; digital wellbeing is related more to competence and autonomy, and effective uses of digital technologies for teaching and learning are related similarly; digital literacy is related to all three needs, while digital agency is similarly related.

Exploring the concept of wellbeing through another lens, Dodge et al. [27] provide an overview of previous research and seek to clarify the definition of wellbeing. They propose that wellbeing is “the balance point between an individual’s resource pool and the challenges faced” (p. 230). These authors consider the resource pool and challenges faced to both be arising from psychological, social and physical sources. It will be clear in the review that follows that these sources also relate to the areas of teacher wellbeing, digital wellbeing, effective uses of digital technologies for teaching and learning, digital literacy, and digital agency. This relationship also provides a foundation for the development and creation of the data collection instrument offered in the last section of this paper.

In terms of measuring wellbeing, Longo, Coyne and Joseph [28] identified fourteen constructs from previous wellbeing models that they used within their measurement instrument. These were happiness, vitality, calmness, optimism, involvement, self-awareness, self-acceptance, self-worth, competence, development, purpose, significance, congruence and connection. In this paper, it is this form of constructs that seek to be identified, but focusing on those that relate to a specific group of individuals—teachers using digital technologies—rather than to a wider population and contexts.

2.2. Teacher Wellbeing

Research reviewed in this sub-section clearly indicates that teacher wellbeing can be affected by psychological, social and physical sources [27], across all three needs of competence, relatedness and autonomy [26]. Savill-Smith [8], from research and reports on teacher wellbeing, identified key issues and factors that influence positive or negative wellbeing outcomes. In her research, factors were explored particularly through a lens focused on physical, lifestyle, psychological and mental health issues. Of the 3019 educational professionals involved in the participant sample, 72% described themselves as stressed (increasing to 84% for senior leaders), 74% considered the inability to switch off and relax to be the major contributing factor to a negative work/life balance, 78% experienced behavioural, psychological or physical symptoms due to their work, and 51% of school teachers attributed work symptoms to pupil/student behavioural issues (p. 6). In this context, within the report [8], four groups of features were identified as contextual and important, all of which could relate to uses of digital technologies by educational professionals. These four groups of factors were: work/life balance, symptoms experienced, work issues, and mental health issues. The groups of features and individual features are:

- Work/life balance—factors which contributed a great deal or somewhat to a negative work–life balance: inability to switch off and relax; working long hours on weekdays; not finding time to be with my family/friends; working over the weekends; working during holidays; family commitments preventing me from doing a good job at work.

- Symptoms experienced linked to possible signs of mental health issues—self-defined or suggested by someone else: anxiety; depression; exhaustion; acute stress.

- Work issues that symptoms were related to: excessive workload; work/life balance; pupils’/students’ behaviour; low income; unreasonable demands from a manager; rapid pace of change (e.g., National Curriculum); problems with pupils’/students’ parents; bullying by colleagues; redundancy/restructure; lack of opportunities to work independently; lack of trust from managers; discrimination; retirement.

- Ways in which mental health problems experienced at work were alleviated: physical exercise; meditation/mindfulness; alcohol; therapy/counselling; self-medication; drugs.

Garland et al. [9] found similar evidence of influences and levels of effect from their research. These researchers gathered evidence from 2400 school staff via a mobile application (app) and from 684 school staff via an open-ended survey. They found that major causes of stress were related to workload and work–life balance (62%), accountability in terms of performance, test scores and inspections (49%), administrative tasks (42%), pastoral concerns related to mental health and safeguarding (39%), relationships with colleagues (25%), relationships with the senior leadership team (23%), and relationships with parents (17%) (p. 6). Related to these causes, the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) in England stated in a recent report on teacher wellbeing in schools and further education colleges [29] the more positive drivers, that teachers “love their profession, overwhelmingly enjoy teaching, are generally very positive about their workplace and colleagues, and enjoy building relationships with pupils and seeing them flourish” but that these are balanced against negative drivers, “high workloads, lack of work–life balance, a perceived lack of resources and, in some cases, a perceived lack of support from senior managers, especially in managing pupils’ behaviour. They sometimes feel the profession does not receive the respect it deserves” (p. 5). Discussions with teachers indicate that this latter feature can arise from parental as well as senior manager comments, linking back to the results of a study cited earlier [19].

However, the relationship between job conditions and teacher wellbeing is not necessarily consistent across countries. For example, Verhoeven et al. [30] compared factors affecting Dutch teachers (304 from seven secondary schools) with a wider European sample (1878 from upper secondary school in 10 countries). They found that job conditions for Dutch teachers did differ from the wider European sample in terms of involving “less physical exertion and environmental risks” (p. 473). Additionally, Dutch teachers reported they were “more depersonalised” and more “satisfied than teachers of the European reference group”, and “had fewer somatic complaints and reported higher levels of personal accomplishment” (p. 473).

From the data presented in the literature reviewed above, it is clear that teacher wellbeing is not only an issue that needs to be explored deeply, but it is an issue that warrants research that can look for ways to address the challenges that teachers face. As Kidger et al. [31] concluded from their study of 555 teachers in 8 schools, “[i]nterventions aimed at improving their mental health might focus on reducing work related stress, and increasing the support available to them” (p. 76).

The specific features that affect teacher wellbeing need also to be considered in terms of a wider motivational context. This wider motivational context was highlighted in the Savill-Smith report [8]; whilst education professionals stated that they enjoyed different aspects of their work, they also indicated that a vitally important concern for them was to make a difference to the lives of young people. Helping young people to achieve their potential, as well as the quality of interactions they had with their learners, were additional and important underlying concerns (p. 22). Interventions that can enhance these positive reasons for teachers being involved in their work and that can help to alleviate problems that they experience will clearly support more positive teacher wellbeing. While Ofsted in England identified in their report [29] a similar list of influences on teacher wellbeing as those reported by Savill-Smith [8], their recommendations to school leaders did not mention the possible positive influences on teacher wellbeing that might be associated with appropriate uses of digital technologies (some of which are shown from analyses reported in Section 3 of this paper).

2.3. Digital Wellbeing

When teachers use digital technologies, digital wellbeing becomes a more focal element within the arena of wider teaching wellbeing. JISC [32] defines digital wellbeing as “a term used to describe the impact of technologies and digital services on people’s mental, physical, social and emotional health” (n.p.). In this context, digital wellbeing can clearly be affected by psychological, social and physical sources [27], but research reviewed indicates that these appear most strongly to relate to needs of competence and autonomy [26]. Research into digital wellbeing has focused largely on students rather than on teachers; digital wellbeing of teachers is a field that has received fairly recent attention (for example, [33]). From the Digital Wellbeing Educators project website [33], the focus described is more concerned with ways that educators can use a range of digital tools. Specifically, seven digital tools are highlighted. These are course creation tools/e-learning authoring tools (to create courses, simulations, or other educational experiences), presentation software/animation tools (to display information in the form of a slide show), webinar/meeting tools (to interact with each other), screencasting, audio and capture tools (to share their screens directly from their browser and make the video available online so that other viewers can stream the video directly), collaboration and file sharing tools (to help people involved in a common task achieve their goals), bookmarking and curation tools (to collaboratively underline, highlight and annotate an electronic text, in addition to providing a mechanism to write additional comments on the margins of the electronic document), and project management tools (to assist an individual or team to effectively organise work and manage projects and tasks).

2.4. Effective Uses of Digital Technologies for Teaching and Learning

A more specific concern of teachers, going beyond digital wellbeing, is that they use digital technologies effectively for teaching and learning. The research literature indicates that these practices are affected by psychological, social and physical sources [27], that they again relate strongly to needs of competence and autonomy [26]. The discourse that encourages uses of digital technologies to support teaching practices and student learning has been prominent in the research literature for over forty years (and summarised through, for example, the meta-analyses of Tamim et al. [34]). Teacher uses of technologies to support effective and specific teaching and learning outcomes have been encouraged and exemplified in both research and policy documents. In terms of policy documentation, the Victoria Curriculum and Assessment Authority (VCAA) in Australia is an example that provides guidance for teachers on accessing and using a range of online resources [35]. The VCAA website offers guidance to teachers about using digital school planning resources, about safe and responsible use, and offers resources concerned with developing professional learning for teachers to build digital capabilities. The website provides access to an online video content platform, educational resources from around the world, a blogging community, virtual conferencing, educational software that adds value to teaching and learning, and core software including the Microsoft Office Suite, software for video, image and music creation, and software to support thinking skills, literacy, mathematics and science. The Education Endowment Foundation [36], on the other hand, takes a different approach in its guidance, highlighting four recommended ways to consider using digital technologies effectively for teaching and learning. These are considering how uses will improve teaching and learning before using them, improving the quality of explanations and modelling, improving the impact of pupil practice, and playing a role in improving assessment and feedback.

2.5. Digital Literacy

Whilst the discourse around digital literacy is sometimes concerned more with competence and confidence, the concepts of digital literacy and digital agency are clearly related in the research literature to ideas about how digital technologies can be used to effectively support teaching and learning. From the literature on digital literacy, it can be seen that digital literacy practices can be affected by psychological, social and physical sources [27], and that they relate to the three needs of competence, relatedness and autonomy [26]. Conceptions of digital literacy of teachers (for example, [37,38]) often describe and identify a set of skills. This set of skills is considered fundamental to having what is regarded as digital literacy. BBC Bitesize [37], for example, states these as how to find sources of information through digital media and how to access them, sorting information for relevance, evaluating information for reliability, credibility and authority, managing information in a legal and safe way, and creating original content. DigComp [38] states these in more detail, through a Digital Competence Framework (in its second version) for all citizens:

- Information and data literacy: browsing, searching and filtering data, information and digital content; evaluating data, information and digital content; managing data, information and digital content.

- Communication and collaboration: interacting through digital technologies; sharing through digital technologies; engaging in citizenship through digital technologies; collaborating through digital technologies; netiquette; managing digital identity.

- Digital content creation: developing digital content; integrating and re-elaborating digital content; copyright and licences; programming.

- Safety: protecting devices; protecting personal data and privacy; protecting health and well-being; protecting the environment.

- Problem solving: solving technical problems; identifying needs and technological responses; creatively using digital technologies; identifying digital competence gaps.

2.6. Digital Agency

Digital agency goes beyond the discourse on digital literacy. The details in the European Commission DigComp framework are related to this more recently termed concept of digital agency of teachers (for example, [39]). In digital agency, the core concern is that the teacher is as much a producer as a consumer with regard to using digital technologies. The literature indicates that digital agency can be affected by psychological, social and physical sources [27], and across all three needs of competence, relatedness and autonomy [26]. The concept of digital agency is described through three intersecting elements. The first, digital competence, is defined as the ability to safely and effectively navigate the digital world. The second, digital confidence, is defined as the ability to expertly use a variety of popular computer applications and software to handle information and communication technology (ICT) in different contexts—for learning, for interacting with family and friends and for societal participation such as accessing government services or purchasing goods and services online. This second element includes a sub-element of digital autonomy, which is defined as knowing the informed basis of one’s choices and actions. The third intersecting element, digital accountability, concerns digital responsibility for oneself and for others regarding one’s digital actions, knowledge of the digital world and its ethical issues, understanding concerns and ensuring security and privacy, and understanding the impact of our digital activities.

2.7. Teacher Wellbeing Arising from Uses of Digital Technologies

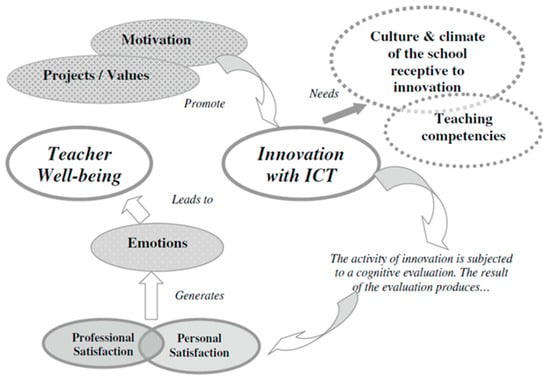

Going back to the overview concept being explored in this paper, in terms of teacher wellbeing arising from uses of digital technologies, there is currently a very limited and focused research literature available. Some recent research and development projects have focused more specifically on the development of teacher wellbeing as an outcome. For example, Rymmin, Kunnari and Fonseca D’Andréa [40], in a review of a teacher education programme with Finnish and Brazilian teachers, stated that “teachers consciously constructed networked expertise and socio-psychological wellbeing by applying digital solutions creatively, and this had a positive impact on their pedagogical practices” (n.p.). One way to summarise and model teacher wellbeing that is influenced by uses of innovative digital technologies has been proposed by De Pablos-Pons et al. [18]. Figure 1 shows the outline of their theoretical model.

Figure 1.

Model relating teacher wellbeing with innovative uses of digital technologies (Source: De Pablos et al. [41]).

However, as they stated, the aim of the study was to “empirically validate the theoretical model” focusing on “the teacher well-being of those teachers who use good practice or innovations with ICT in primary and secondary schools” ([41], p.2760). In the context of innovative use, the authors, from their own literature review, identified seven critical factors concerned with driving a wellbeing balance for teachers when they use digital technologies in this way:

- Background motivations to use the digital technologies.

- Project and values that are identified or foreseen.

- Influence of the culture and climate of the school.

- Teaching competencies.

- Personal satisfaction.

- Professional satisfaction.

- Emotions generated.

The literature reviewed in the previous sub-sections of this paper shows that there is a potentially wide range of factors and features that can influence teacher wellbeing when teachers use digital technologies to support teaching and learning practices. Clearly, these factors can have a positive or negative effect or indeed a neutral effect on teacher wellbeing. How might these factors and features be initially modelled and framed to support future research in this area?

3. Materials and Methods: Approach and Methodology

The aim of the study presented in this paper is to derive a data collection instrument that can gather evidence about how teachers, using digital technologies, perceive the effects of use on their wellbeing. The inductive approach that is taken follows three sequential steps:

- From the range of literature reviewed, and drawing out the features and factors from that literature that are shown to affect teacher wellbeing when using digital technologies (both positively and negatively), two initial outcomes can be developed. Firstly, an outline conceptual model can be created that identifies key features to be considered when researching teacher wellbeing arising from uses of digital technologies. Secondly, a conceptual framework can be detailed that lists pertinent influencing factors within each of the features of the model (shown in Section 3.1).

- To assess the efficacy of the framework, previous studies that have gathered evidence about how teachers use digital technologies in a variety of settings and contexts are re-analysed using document analysis. This re-analysis involved examination and interpretation of the documents through a specific lens—the individual features listed in the framework (shown in Section 3.2). Whilst it is recognised that a qualitative data analysis program could have been used to undertake this re-analysis, the author chose to adopt a manual method, as the wider context of the case study was important in fully identifying and describing the evidence that supported each feature.

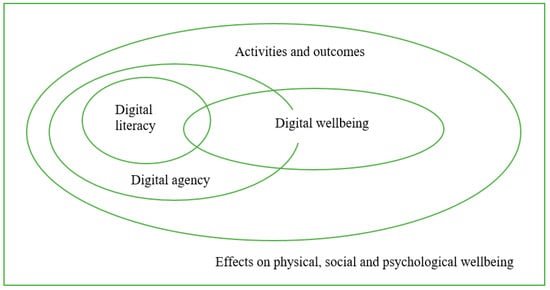

3.1. A Conceptual Model and Framework

A conceptual model that matches and accommodates the categories of features arising from the current literature review is shown in Figure 2. It is clear that this is not a simplistic field to explore; it is complex, as shown by the general relationships and overlaps in Figure 2. This paper does not explore the detail of these overlaps and relationships, which would be a focus of a separate paper and study. It is also acknowledged that other possible models might be drawn and might accommodate other features that would emerge and become identified in the future. Whilst it is worth noting the complexity of this field through the diagrammatic representation in Figure 2, it is the features and factors across this model that will be extracted in order to propose a framework that will lead to the development of an instrument to gather evidence about ways that digital technologies might be affecting teacher wellbeing.

Figure 2.

A conceptual model that identifies key features affecting teacher wellbeing when using digital technologies.

The proposed framework developed from the model offered in Figure 2 is shown in Table 1. The factors in this framework are derived from those identified within the literature review, detailed within the previous section and sub-sections of this paper. In Table 1, the factors that are taken from the literature are all phrased in ways to indicate how these might support teacher wellbeing if present, or not if absent. For the final instrument, these factors are constructed in ways offering the potential to gather evidence that could have either positive, neutral or negative influence on teacher wellbeing when teachers are using digital technologies.

Table 1.

A conceptual framework detailing factors influencing positive teacher wellbeing when using digital technologies.

The list of factors in the framework will be used in the next section of this paper (but will be referred to by the codes in the right-hand column of Table 1) in order to consider how a number of cases (where digital technologies were used and reported to lead to a number of positive teacher outcomes that could be related to wellbeing) can be re-analysed to check the framework efficacy. This approach is taken to explore the use of a more structured identification of the specific factors that might influence enhanced teacher wellbeing.

3.2. Exploring the Framework Efficacy through Case Re-analyses

The author has undertaken previous studies that have gathered evidence about how teachers use digital technologies in a variety of settings and contexts. These studies have gathered evidence identifying reasons why and how teachers perceive both benefits and challenges [27], and how they consider this balance in their views and perspectives about the value of using digital technology, to them as teachers. In this section, a number of those reported cases are re-analysed by the author of this paper. Document analysis, as described for example by Bowen [42], was the methodology adopted for this re-analysis. This methodology entails examination and interpretation of the documents through specific lenses (in this case, the individual features listed in Table 1). In each case within the sub-sections following, the background and outcomes are described and then specific details from the cases that evidence influence on the factors in the framework are listed. The author re-read the case studies and identified, for each factor in Table 1, how the teacher reported this (or not), and the evidence they gave in order to demonstrate this feature having an effect upon their wellbeing. These details of evidence are shown in tables within each of the sub-sections that follow.

The selection of these case studies was made on the basis of the original purpose of the case study (identifying why and how teachers perceive and recognise benefits and challenges of using digital technologies), the forms of evidence gathered (qualitative short cases), covering a range of different settings (phases across compulsory education), varied digital technologies (the resources used and for what subject or educational purposes) and different contexts (in-class and online in different countries). From this re-analysis approach, it is possible to see whether individual factors can be identified as being influential in these instances. Using the outcomes of this re-analysis, the efficacy of the framework is assessed. As negative features have been identified in many previous studies, the efficacy focused more on identifying positive features. However, instruments developed and shown in Section 5 will focus on the collection of evidence that is negative, neutral and positive.

3.2.1. Using an Interactive (SMART) Board

A teacher in a German secondary school (gymnasium) had access to a mobile SMART panel with Notebook and document camera, and a mobile SMART kapp iQ panel, able to be connected to the teacher’s laptop and to a school virtual learning environment (VLE). The teacher was familiar with the use of interactive whiteboards, but in her school, this was the first time she had had opportunity to use an interactive whiteboard for a number of years. She used the interactive boards in her teaching room with all her classes (in mathematics and English). She felt the use of the interactive boards was supporting her teaching practices, as well as pupil learning. Her use was frequent; she used at least one of the interactive boards in all lessons. The full case study is reported elsewhere [43], and the re-analysis identified ways that the digital technologies are likely to have influenced teacher wellbeing, shown in Table 2. Likely factors not identified are not included in this table, or in the tables in subsequent sub-sections.

Table 2.

Likely influencing factors in case 1.

It should be noted that a feature arising from this case study was not already identified in the proposed framework—reducing reliance on tools considered unhealthy. This feature has been added into the framework in Table 2, and in subsequent tables.

3.2.2. Using a Software Learning Resource, Learning by Questions (LbQ)

LbQ is a software resource bank which provides questions that cover entire areas of the curriculum for specific age groups (in mathematics, literacy and science). The questions are grouped according to levels of difficulty and their applicability to real-life problems. The levels allow pupils to move from more general understanding to reasoning and finally to problem-solving. The full case study is reported elsewhere [44], and this re-analysis identified ways that the digital technologies are likely to have influenced teacher wellbeing, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Likely influencing factors in case 2.

3.2.3. Engaging with Parents through Uses of Digital Technologies

This case explores uses of digital technologies to support parental engagement in a primary school in Northern Ireland. The full case study is reported elsewhere [45], and the re-analysis identified ways that the digital technologies are likely to have influenced teacher wellbeing, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Likely influencing factors in case 3.

3.2.4. Using and Contributing to an Online Resource Bank, NewsDesk

NewsDesk is a resource available to all schools in Northern Ireland. A C2k guidance document [46] states that:

“NewsDesk gives pupils an opportunity to engage with current news stories in a digital environment. They can be active users with opportunities to comment on stories and submit their own topical writing to a ready-made audience. NewsDesk also gives pupils opportunities to practise talking and listening and reading and writing skills that they have learned in the classroom” (p. 2).

The full case study [47] explores uses of this resource in a primary school in Northern Ireland; it is one element of a resource prepared for publication in Northern Ireland. From the re-analysis, likely ways that the digital technology has influenced teacher wellbeing are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Likely influencing factors in case 4.

3.2.5. Using Online Teaching and Learning during School Lockdown

This case describes how a teacher moved her own practice and that of her colleagues from face-to-face teaching to online teaching during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. The teacher works in a secondary school in Germany—a gymnasium. When the school was closed due to lockdown, the teacher set up online classrooms for each of her classes, online classrooms for the majority of the other classes in the school, as well as an online staff room. The online classrooms allowed pupils to be involved in online lessons. In this way, using online teaching was found to support teacher wellbeing during the coronavirus pandemic. The full case study [48] has been re-analysed, identifying ways that the digital technology influenced teacher wellbeing, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Likely influencing factors in case 5.

It is clear from details in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 that factors identified as influencing teacher wellbeing across these five cases are different in each case, but with some common factors arising. Certain factors are more commonly identified, in two or more cases. Implications of these similarities and differences are discussed in the next section of this paper. What has been shown from the re-analyses of five cases is that the framework in Table 1 provides a means to identify influencing factors. However, means to identify positive, neutral and negative influences need to be developed, and a proposed means to do this will be shown in Section 5.

4. Discussion

Considering the maximum number of ways that a technology could influence wellbeing of a teacher across all five cases in the previous section, and within each of the five categories identified in Table 2, this would total: 35 for digital literacy; 20 for digital agency; 40 for digital wellbeing; 45 for activities and outcomes; and 110 for effects on physical, social and psychological wellbeing. The actual number and percentage of positive features that were identified from the analysis of the five cases were: 26 out of 35 (74%) for digital literacy; 14 out of 20 (70%) for digital agency; 39 out of 40 (98%) for digital wellbeing; 34 out of 45 (76%) for activities and outcomes; and 13 out of 110 (12%) for effects on physical, social and psychological wellbeing. Across these five cases, the most influential category identified in supporting positively was digital wellbeing, followed by activities and outcomes, digital literacy and digital agency, with limited influence being shown on physical, social and psychological wellbeing. It should be noted, however, that this outcome could at least in part have arisen from the fact that data gathering from the case studies did not ask specific questions about this latter area or indeed about some of the elements in other categories. If data are to be gathered about the influences as a whole on teacher wellbeing, then clearly a wide range of questions needs to be asked if the potential influences (negative and neutral as well as positive) are to be fully considered.

To view similarities and differences across the identified positive factors in all cases, an overview grid (shown in Table 7) has been created. The right-hand column totals the number of instances that the factor was identified across the five cases. The factors are ordered from the highest number of instances (5 in total) to the lowest (1 in total). Again, it should be noted that factors other than those identified might have been involved, but when the cases were created, specific questions relating to these other factors were not asked of the teachers.

Table 7.

Likely influencing factors across all 5 cases.

The factors where influence was not identified (gaining 0 responses across all five cases), and perhaps where more emphasis needs to be placed on subsequent studies in this field were: feeling more able to switch off and relax; reducing long weekday hours; finding more time to be with family and friends; reducing weekend working; reducing holiday working; reducing anxiety; reducing depression; reducing workload; offering a better work/life balance; reducing unreasonable manager demands; reducing colleague bullying; offering more opportunity to work independently; reducing discrimination; enabling more physical exercise; and reducing reliance on ways to alleviate stress.

From Table 7, it can be seen that it was certainly possible to identify factors influencing more positive teacher wellbeing in each case, given the details known within the cases analysed. The original set of factors listed in the left-hand column of Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 and in the left-hand column of Table 7 appears to cover related outcomes of teacher wellbeing for each of the range of different digital technologies used. Relevant identification holds for each of the cases, which focus on different schools, different contexts, different digital technologies and different actors involved (pupils, teachers, principals and parents). Certain factors have been identified as those likely to influence a wide range of cases (across all five cases in this paper), while some have not been identified at all. However, given the sources to which these factors were related, this does not mean that any of these are not important or irrelevant. What might be inferred at this stage is that those with higher total ratings are those that might be relevant to many different situations.

Overall, the conceptual framework shown in Table 1 identifies features and factors of teacher wellbeing that are driven by psychological, social and physical concerns [27]. In order to retain this range and possible balance for any case situation, the full set of features and factors that are known at any one time should be considered when undertaking research that gathers evidence about effects of digital technologies on teacher wellbeing; furthermore, instruments should allow for negative and neutral influences to be gathered as well as positive influences. When asking teachers about their experiences, these features and factors can certainly be framed or phrased using existing research tools and approaches in ways that enable the identification of negative and neutral influences as well as positive influences. This balance of negative, neutral and positive influences can effectively be gathered and accommodated within adopted data collection and analysis methods, chosen according to study contexts (with an example provided in the next section of this paper). Additionally, it should be noted that background studies contributing to this conceptual framework (particularly [8,9]) did identify negative influences as part of their data collection and analysis methods.

5. Conclusions

From the analysis and discussion presented in the previous section, it is vitally important that a full range of features and factors are used when gathering data to explore whether and how digital technologies influence teacher wellbeing (and exactly in what ways and to what extent). Questions to ask teachers, drawn from the conceptual framework and the analysis of its applicability to a range of case scenarios is shown in Table 8, in the form of a data gathering instrument. Some redundant (repeated) factors have been eliminated from the factors listed, and the list has been reordered to group questions into categories (shown in the lettered headers A-E of Table 8), aligned with commonly encountered topics associated with data gathering when these are undertaken in case study situations. In this data gathering instrument (Table 8), each feature is introduced with a general question that relates to the focus of that feature, followed by specific factors that are presented with a range of response options in Likert-style form in order to gather negative, neutral and positive perceptions, and finally, each feature ends with an open-ended question.

Table 8.

Questions related to factors influencing teacher wellbeing.

It should be noted that the data collection instrument shown in Table 8 is not a scale measurement tool. The study was not undertaken in a way that would allow the development and assessment of the use of a scale development tool, using a scale development approach. It might also be argued that the questions in Table 8, identifying factors affecting teacher wellbeing when using digital technologies, can only gather evidence that would be considered to be too ‘subjective’. Indeed, Veerhoven [49] discusses distinctions between subjective and objective evidence in detail and indicates the importance of considering evidence that can combine both the subjective with the objective where possible. If this data collection instrument is used in a case study scenario, it is argued that it is important that the ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions, which Yin [50] so rightly emphasised as being critical to understanding any case, are asked additionally. It is through the understanding and detail that arises from answers to these ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions that can lead to examples of ways to support teachers positively.

In summary, digital technologies have more commonly been identified in the past as having negative influence on teachers and their wellbeing. Whilst examples of such negative influence clearly exist, it is also important for us to identify where positive influences on teacher wellbeing may be arising, in order for us to support teachers more effectively in the future—in terms of their needs, in times when demands on their time and on their expertise do not seem to be diminishing. We owe it to the teacher profession to understand much more exactly when, how and why positive teacher wellbeing can be supported through effective uses of digital technologies. Given the current situation from 2020 and ideas of different possible future scenarios of how educational provision may be developed to address contemporary challenges, it is particularly important that this area of research focuses on four different alternatives. These four alternatives should cover contexts where teacher wellbeing arises from uses of digital technologies firstly in a purely face-to-face classroom environment, secondly in a purely online environment, thirdly through a blended model where face-to-face and online happen at different scheduled times, and fourthly through a hybrid model where face-to-face and online are happening concurrently. A deeper understanding of how teacher wellbeing in each context can be supported is likely to match the needs for our future in education.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the EN(ni) Innovation Forum in Northern Ireland and SMART Technologies for their interest in this work; without their involvement, the focus on this emerging area of research would not have been identified.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ecclesiastical: Parents and Students Using Social Media to Harass Teachers. Available online: https://www.ecclesiastical.com/documents/teacher-cyber-bullying.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- BBC News: Teachers Tired of Pointless Emails. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/education-46959295 (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Winchester, N. Technology: Health and Wellbeing of Children and Young People-Debate on 17 January 2019; House of Lords: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mackin, S. Searching for digital technology’s effects on well-being. Nature 2018, 563, S138–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.; Rainie, L. Concerns about the Future of People’s Wellbeing; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S.; Morris, R.; Gunnell, D.; Ford, T.; Hollingworth, W.; Tilling, K.; Evans, R.; Bell, S.; Grey, J.; Brockman, R.; et al. Is teachers’ mental health and wellbeing associated with students’ mental health and wellbeing? J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 253, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Jones, P. The Impact of Digital Technologies on Human Well-Being; Nominet Trust: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Savill-Smith, C. Teacher Wellbeing Index 2019; Education Support: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, L.; Linehan, T.; Merrett, N.; Smith, J.; Payne, C. Ten Steps towards School Staff Wellbeing; Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gilster, P. Digital Literacy; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Belshaw, D. The Essential Elements of Digital Literacies. Available online: http://dougbelshaw.com/ebooks/digilit/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Aagaard, T.; Lund, A. Digital Agency in Higher Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brevik, L.; Guðmundsdóttir, G.; Lund, A.; Strømme, T. Transformative agency in teacher education: Fostering professional digital competence. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, S. The Potential and Challenges of Digital Well-Being Interventions: Positive Technology Research and Design in Light of the Bitter-Sweet Ambivalence of Change. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JISC: Jisc Digital Capabilities Framework—The Six Elements Defined. Available online: http://repository.jisc.ac.uk/7278/1/BDCP-DC-Framework-Individual-6E-110319.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- ICF Consulting Services. Literature Review on the Impact of Digital Technology on Learning and Teaching; The Scottish Government: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, T.; Higgins, C.; Loveless, A. Report 14: Teachers Learning with Digital Technologies: A Review of Research and Projects; Futurelab: Bristol, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Pablos-Pons, J.; Colás-Bravo, P.; González-Ramírez, T.; Martínez-Vara del Rey, C.C. Teacher well-being and innovation with information and communication technologies; proposal for a structural model. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 2755–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusimäki, A.-M.; Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L.; Tirri, K. The Role of Digital School-Home Communication in Teacher Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DFE: Adapting Teaching Practice for Remote Education. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/adapting-teaching-practice-for-remote-education (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Duffield, S.; O’Hare, D. Teacher Resilience during Coronavirus School Closures. Available online: https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/www.bps.org.uk/files/Member%20Networks/Divisions/DECP/Teacher%20resilience%20during%20coronavirus%20school%20closures.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Kehoe, R. Learning will Change with COVID-19’s Social Distancing. Available online: https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/learning-change-covid-19-social-distancing (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Viner, R.M.; Russell, S.J.; Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Ward, J.; Stansfield, C.; Mytton, O.; Bonell, C.; Booy, R. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: A rapid systematic review. Lancet 2020, 4, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, N.; Laydon, D.; Nedjati Gilani, G.; Imai, N.; Ainslie, K.; Baguelin, M.; Bhatia, S.; Boonyasiri, A.; Cucunuba Perez, Z.U.L.M.A.; Cuomo-Dannenburg, G.; et al. Report 9: Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to Reduce COVID-19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand. Available online: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/mrc-gida/2020-03-16-COVID19-Report-9.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- ONS: Deaths Registered Weekly in England and Wales, Provisional-Week Ending 22 May 2020. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregisteredweeklyinenglandandwalesprovisional/weekending22may2020#deaths-registered-by-age-group (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, Y.; Coyne, I.; Joseph, S. The scales of general well-being (SGWB). Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 109, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofsted: Teacher Well-Being at Work in Schools and Further Education Providers, July 2019, Reference Number 190034. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/819314/Teacher_well-being_report_110719F.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Verhoeven, C.; Kraaij, V.; Joekes, K.; Maes, S. Job Conditions and Wellness/Health Outcomes in Dutch Secondary School Teachers. Psychol. Health 2003, 18, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidger, J.; Brockman, R.; Tilling, K.; Campbell, R.; Ford, T.; Araya, R.; King, M.; Gunnell, D. Teachers’ wellbeing and depressive symptoms, and associated risk factors: A large cross sectional study in English secondary schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 192, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JISC: Digital Wellbeing. Available online: https://digitalcapability.jisc.ac.uk/what-is-digital-capability/digital-wellbeing/ (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Digital Wellbeing Educators: Categories. Available online: http://www.digital-wellbeing.eu/categories/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Tamim, R.M.; Bernard, R.M.; Borokhovsi, E.; Abrami, P.C.; Schmid, R.F. What Forty Years of Research Says About the Impact of Technology on Learning: A Second-Order Meta-Analysis and Validation Study. Rev. Educ. Res. 2011, 81, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State Government of Victoria Australia: Using Digital Technologies to Support Learning and Teaching. Available online: https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/principals/spag/curriculum/Pages/techsupport.aspx (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Education Endowment Foundation: Using Digital Technology to Improve Learning. Available online: https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/tools/guidance-reports/using-digital-technology-to-improve-learning/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- BBC: Digital Literacy. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zxs2xsg/revision/1 (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- European Commission: Science Hub-The Digital Competence Framework 2.0. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/digcomp/digital-competence-framework (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Passey, D.; Shonfeld, M.; Appleby, L.; Judge, M.; Saito, T.; Smits, A. Digital agency-empowering equity in and through education. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2008, 23, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymmin, E.; Kunnari, I.; Fonseca D’Andréa, A. Teacher Education Programme for Brazilian Teachers. Available online: https://uasjournal.fi/koulutus-oppiminen/digital-solutions-in-teacher-education-enhance-wellbeing-and-expertise/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- De Pablos, J.; Colás, P.; González, T. Bienestar docente e innovación con tecnologías de la información y la comunicación. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2011, 29, 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, G.A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qual. Res. J. 2009, 9, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passey, D. Collaboration, Visibility, Inclusivity and Efficiencies: A Case study of a Secondary School in Germany Using Interactive Whiteboards; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Passey, D. Learning by Questions (LbQ): Outcomes from Uses in Schools in Northern Ireland— Working Paper; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Innovation Forum (ENNI). Advancing and Enhancing Parental Engagement with Schools through Digital Applications—Leadership Guidance: Purpose, Planning and Managing, Controlling Expectations and Evaluating; Innovation Forum (ENNI): Belfast, Northern Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CCEA. C2k NewsDesk Guidance: Using C2k NewsDesk as a Digital Tool to Inspire and Engage Pupils; CCEA: Belfast, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Passey, D. NewsDesk: Uses and Outcomes in NI schools; Innovation Forum (ENNI): Belfast, Northern Ireland, manuscript in preparation.

- Google. Aufbruch Ausgabe Nr. 20: Lernen und Arbeiten; Google: Dublin, Ireland, 2020; pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Veerhoven, R. Subjective measures of well-being. In Human Well-Being: Concept and Measurement; MacGillivray, M., Ed.; MacMillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2007; pp. 214–239. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).