Abstract

Accelerating demand for energy and its consumption has become a credible threat to the sustainable ecosystem due to the exploitation of scarce natural resources and environmental hazards. The adoption of renewable energy sources for sustainable development has been gaining traction among researchers and practitioners alike. Considering its hot climate, Pakistan has a huge potential to meet its energy requirements by tapping into renewable energy resources, especially through the use of solar photovoltaic (SPV) technologies. However, the adoption rate of this technology remains still quite scant among consumers. In this regard, the present research explores the factors that affect households’ purchase intention of SPV technology in Pakistan. The study has developed a comprehensive research framework by decomposing the technology acceptance model (DTAM) into second-order sub-constructs. Afterward, Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to analyze the data by decomposing perceived usefulness (PU) into social, economic, and environmental usefulness and perceived ease of use (PEOU) into discomfort and insecurity and to assess their cumulative effects on consumer attitude. Moreover, the moderating role of policy and propaganda was also investigated. Empirical results assert that PU and PEOU positively and significantly shape the consumer attitude toward SPV adoption. Subsequently, consumer attitude has a positive and significant impact on the actual purchase intention of SPV technology. Furthermore, the moderating role of governmental policy and propaganda between the consumer attitude and actual purchase intention was also confirmed. The policy implications of these results are discussed. Finally, the limitations and future directions of the research are also elaborated.

1. Introduction

Escalating energy demand and increased consumption over the past few decades imply that sustainable energy production for environmental preservation will remain one of the significant challenges, especially for the developing world (Akbar et al. 2020a). Energy plays a pivotal role in fueling the growth and economic development of countries. A country cannot flourish without an appropriate portfolio of energy resources. Electricity is considered a critical component of the country’s economy (Irfan et al. 2019). World inhabitants are increasing rapidly, and their materialistic lifestyles will further mount the energy demand (International Energy Agency 2019) as the residential sector is the largest consumer of energy resources (Ali et al. 2019a). Excessive use of hydrocarbons as well as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of conservative sources of energy has augmented the application of renewable energy sources universally. The importance of the adoption of rooftop panels is evident from the fact that household appliances are the major contributors toward carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and accounts for 70% of the overall emissions worldwide (Ali et al. 2019a).

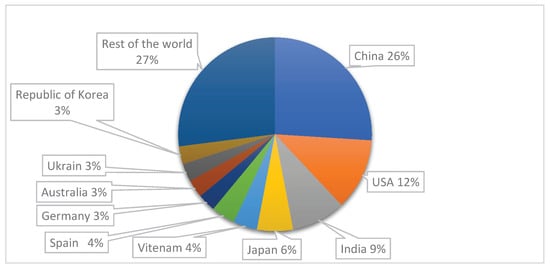

The adoption of solar panels at the household level can help mitigate excessive CO2 emissions. Various factors, such as technology acceptance, government policies, investment, and favorable regulations for renewable energy technologies are increasing the demand for sustainable sources of energy (Akbar et al. 2020b). Households are now looking for affordable, eco-friendly energy sources that will keep the environment clean. Even though renewable and green energy has become a center of attention and a crucial topic of research and discussion worldwide, the adoption rate is still low. The slow acceptance of renewable energy is not only witnessed in emerging economies but also in the industrialized world (Zahari and Esa 2018). Different types of green energy sources include wind, hydroelectric, solar, geothermal, and bio-energy. Among them, roof-mounted solar panels are the most acknowledged ones at the household level worldwide. According to renewable global status report 2020, Solar PV energy grew by 12% and added 115 GW only in 2019. The global total Solar PV production reached 627 GW till 2019, with the highest proportion from China with a capacity of 204.7 followed by the USA, India, Japan, Vietnam, Spain, Germany, Australia, Ukraine, and the Republic of Korea. Out of 627 GW, these 10 countries are responsible for 67% of the production while the rest of the world produces only 27% (see Figure 1) (REN21 2020).

Figure 1.

The worldwide scenario of solar PV technology (REN21 2020).

Among the list of top 10 ecologically affected countries, only one was the developed nation rest of them are developing nations. For example, countries such as the Philippines, Haiti, and Pakistan are the most affected by climate change and continuously rank among the adversely affected economies in the global index (Eckstein 2019). Similar to many developing economies, Pakistan is also an energy-deprived nation where the gap between demand and supply remains substantial during peak summer hours. Additionally, the unmet demand for Pakistan was almost 4700–7000 Mega Watt in 2017 (Valasai et al. 2017). Households are the dominant energy consumers in Pakistan and also a significant recipient of subsidies, which burdens the national economy. Pakistan is blessed with several renewable energy alternatives. However, to meet energy demand, in 2006, Pakistan introduced its renewable energy adoption policy to add sustainable resources in its energy mix (Wang et al. 2020). However, unfortunately, after 14 years Pakistan still relies on unsustainable energy resources, and 80% of the energy is produced from crude oil and hydel plants contributed 11%, coal 6%, LPG 1% while the contribution from the solar PV technology is 0% (Zafar et al. 2018). Conversely, owing to its geographical location, Pakistan lies in the Sun Belt and receives extensive sunshine throughout the year. To cope up with the mounting demand for energy and preserve the environment, rooftop photovoltaic (PV) is the most viable energy option in the country. Moreover, the significance of solar system adoption in Pakistan is evident from the study of Qureshi et al. (2017) who contend that the total demand for electricity in the country can be fulfilled by installing 20% of solar panels efficiently on 1% of the land of Baluchistan province. This highlights the significant potential of solar PV technology in Pakistan to fulfill its electricity demand.

Nevertheless, chronic electricity shortage can also be tackled through the installation of solar photovoltaic (PV) at the household level. Despite its huge potential, the acceptance rate of solar PV is still low in Pakistan and needs to be used effectively. Moreover, several researchers from developed countries have focused on the SPV adoption from the consumers’ perspective, yet the studies in developing countries in this domain are comparatively rare. However researchers in Pakistan have merely explored the SPV adoption from the economic viability perspective (Khalid and Junaidi 2013), barriers and policy (Khattak et al. 2006; Khalil and Zaidi 2014), the role of communication channels (Qureshi et al. 2017; Khalil et al. 2018) but none of the study has focused on households intention to use solar PV systems. Dewan and Kraemer (Dewan and Kraemer 2000) argue that research findings of developed countries cannot be implemented in developing countries due to different social, economic, and political settings. Hence, there is a need to explore household intentions to use PV solar panels in Pakistan.

Solar PV panels’ adoption is at the nascent stage in Pakistan, and the adoption rate is quite slow. Therefore, understanding the factors that affect consumers’ intention to adopt novel technologies such as solar PV is essential. In technology acceptance and renewable energy resources, Davis (1989) proposed the technology acceptance model (TAM), which explains and predicts an individual’s acceptance of new and novel technologies. TAM consists of two core variables perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU), which affect consumers’ motivation and perception to adopt new technology. PU refers to the degree to which individuals perceive any technology can enhance their wellness. PEOU refers to the degree to which an individual believes that using the new technology would be effortless (Davis 1989). These definitions do not completely explicit the complex nature of the PU and PEOU. Besides, these constructs were considered a one-dimensional concept by previous studies (Rose and Fogarty 2000; Ahmad et al. 2017; Rahman et al. 2017). Therefore, some of the studies have indicated that there is a need to check PU and PEOU from diverse perspectives (Bock et al. 2005; Hamari et al. 2016; Hawlitschek et al. 2016; Rahman et al. 2017; Acheampong et al. 2017; Martens et al. 2017). However, no study systematically developed a critical model for discovering the multi-dimensional nature of PU and PEOU. Furthermore, scholars have also suggested that the inclusion of relevant variables in the technology acceptance model can increase its explanatory power within a specific context (Chin and Lin 2016; Ching-Ter et al. 2017; Gbongli et al. 2019). Keeping this in mind, this study employs TAM a multi-dimensional second-order construct by decomposing PU and PEOU into various sub-constructs.

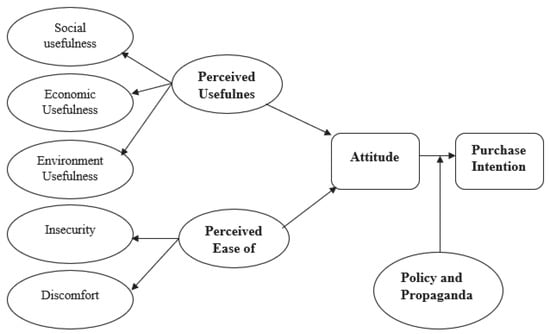

PU consists of three sub-constructs, i.e., social usefulness (contributing to society), economical usefulness (reducing cost), and environmental usefulness (saving the environment and natural resources) (Garay et al. 2019). PEOU consists of insecurity (distrust or fear that technology will fail to perform) and discomfort (perceived lack of control or inconvenience while using technology) (Rahman et al. 2017; Acheampong et al. 2017; Martens et al. 2017), which are applicable in the context of solar PV. Based on these second-order constructs, this study provides a decomposed technology acceptance model (DTAM) in the solar PV context, which can render a comprehensive understanding of consumers’ behavior in Pakistan.

Thirdly, there has been very little research and various analogies to understand the behavioral attitude-intention relationship. Even in developing nations such as Pakistan, consumers know the benefits of advanced energy-efficient technologies such as PV technology but do not want to purchase it. One of the reasons is the non-serious government policies and support. Previous studies in the solar PV domain also lack an explanation of how government policies can affect an individual’s intention to adopt solar PV technology. However, it is found that favorable policies, government support, and propaganda affect consumer behavior regarding green energy consumption, especially in developing countries. Moreover, a recent study asserts that the perspective of the government should be considered while examining the adoption of solar PV technology (Ahmad et al. 2017). Hence, the present study also explores the moderating role of policy and propaganda (PP) in the relationship between attitude and intention to use solar PV. Policy and Propaganda is defined as “the facilitation of the conditions which translates into how available the resources (external factors) which are needed for the behavior are to be carried out”. Besides, to narrow down this theoretical and contextual gap, our research develops a comprehensive conceptual model by decomposing TAM and incorporating moderation of PP to better explain the consumer behavior regarding solar PV technology.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 consists of a literature review and hypotheses are developed based on previous studies. Section 3 explains the methodology of the study, while data analysis and findings are discussed in Section 4. The reasons for the results are discussed in Section 5, and the ultimate conclusions and policy implications of the study are elaborated in Section 6.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Extant literature has proposed a variety of models to investigate factors affecting the adoption of innovative technologies. These models include the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Hill et al. 1977), the theory of reasoned action (TPB) (Ajzen and Madden 1986), and the technology acceptance model (Davis 1989). TAM originated from the psychological theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior (Marangunić and Granić 2015). TAM is mainly used to explicate the general determinants of technology acceptance, which illustrates consumer’s behavior across a broad range of innovative technologies. This study focuses on the technology acceptance model (TAM) as the logical framework. The purpose of using TAM is mainly because of the nature of the study, as solar PV is a relatively new technology in Pakistan. TAM traditionally involves two constructs “Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) and Perceived Usefulness (PU)”. PEOU is the extent to which novelty in technology is considered to be easy to understand and use while PU is the degree to which a person believes that particular technology would increase his or her utility (Davis 1989).

PU and PEOU only partially explain the effects of consumer intention. This drawback represents prospects for future research to provide a comprehensive and improved model, thus reflects the feasibility of the current study. Therefore, this study employs TAM as a decomposition model, i.e., perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are decomposed into the multi-dimensional constructs and operationalized in higher order. PU is a complex construct and can have a different composition for different technologies and respondents, e.g., usefulness for a user would be different in green IT adoption than for solar PV technology. Consequently, few researchers have suggested examining PU in line with the underlying technologies. Keeping this in mind, we decompose PU into three sub-constructs, i.e., social, economic, and environmental (Garay et al. 2019). Consumers can use solar PV as a symbol of green energy consumption or as a socially responsible behavior by saving resources for others. Besides, cost reduction in energy consumption can also be perceived as a useful aspect of technology for households. Moreover, due to environmental hazards caused by the non-renewable sources of energy, consumers are shifting their preferences from unsustainable energy consumption to sustainable and green consumption. These factors, put together, make solar PV a favorable source of energy for the consumers. Moreover, using technology without considerable effort enhances the probability of adopting that technology.

In this regard, the perceived ease of use positively affects consumer behavior to use new technology. However, the fundamental technology acceptance model lacks an explanation of the factors that influence perceived ease of use. For better understanding, several research efforts have been made in different contexts by extending PEOU. However, none of the studies has checked PEOU as a second-order construct, which can better explain the phenomena of solar PV adoption. Therefore, the present research decomposes PEOU into diverse sub-factors. i.e., Insecurity and Discomfort (Rose and Fogarty 2000; Rahman et al. 2017; Martens et al. 2017). Insecurity refers to being distrustful of a particular technology and perception that technology will not work appropriately. In comparison, discomfort refers to a perceived lack of control over technology or feeling uncomfortable in the adoption of new technologies (Parasuraman 2000).

This model focuses on an attitudinal explanation of intention to use a specific technology. Attitude refers to the consumers’ favorable or unfavorable assessment of a particular behavior (Ajzen 1991). It is the combination of beliefs regarding a specific behavior that drives an individual to perform or not to perform a particular task (Ali et al. 2019b). The intention is something defined as a planned beginning with the inclination to do something in the near future (Bratman 1990). Further constructs from TAM were always considered to be drivers for the adoption intention of the technology (Zahari and Esa 2018). As Demand for renewable energy technology is growing in developing countries, hence it is imperative to investigate consumers’ attitudes toward and intention to use renewable energy (Alam and Rashid 2012). Some empirical studies which have used the modified TAM model are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Modified TAM model.

2.1. Hypotheses Development

The consumer’s attitude to adopting new technology is a good indicator of their purchase intention. Attitude plays an imperative role in the adoption of renewable energy resources (Heras-Saizarbitoria et al. 2013). The relationship between attitude and intention is also verified by the study by Rose and Fogarty (Ahmad et al. 2017). They postulate that consumer’s attitudes influence intention to use solar PV technology. PU and PEOU influence this attitude. Alam and Rashid (2012) conjecture that consumers are more likely to use renewable energy resources if these are simple, easy to install, and easy to use, especially without any help from technical experts. Similarly, Stephenson and Ioannou (2010) argue that renewable energy sources will be socially accepted if individuals find them identical to their living standards and user-friendly. Researchers also revealed the significant effects of PU on attitude to use novel technologies and renewable energy resources. Likewise, Wojuola and Alant (2017) show that PU and PEOU are significant factors to measure the purchase intention of Nigerian consumers to use new technologies. The findings were also verified by the work by Yoon (2018) who revealed that PU and PEOU affect green technology acceptance. Moreover, the research conducted in the context of Malaysia also referred to the positive effects of PU and PEOU on the attitude to adopt renewable energy resources (Kardooni et al. 2016).

As discussed above, the theoretical model is based on TAM. Based on the existing literature, the hypotheses regarding the core TAM relationships have been formulated as follows;

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Consumer’s perceived usefulness of solar PV technology significantly and positively affects attitude toward using solar PV technology.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Consumer’s perceived ease of use of solar PV technology significantly and positively affects attitude toward using solar PV technology.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Consumer’s attitude toward using solar PV technology significantly and positively affects their intention.

2.2. Moderating Role of Policy and Propaganda (PP)

As per the NATO definition of Policy and Propaganda (PP), “any information, ideas, doctrines, or special appeals disseminated to influence the opinion, emotions, attitudes, or behavior of any specified group to benefit the sponsor either directly or indirectly”. From a behavioral perspective, Policy and Propaganda is defined as “the facilitation of the conditions which translates into how available the resources (external factors) which are needed for the behavior are to be carried out”. In addition, consumer behavior is not only influenced by the internal factors but also by some external factors such as local cultures, conditional factors, and different social and government policies. These factors are mostly known as contextual factors that influence consumer intention and the decision-making process (Song et al. 2019a; Saeed et al. 2013). In developed regions, the strong policy for renewable energy resources can increase the adoption rate for consumers by the government authorities. Therefore, the policy and propaganda from the government can play a very critical role in the adoption of solar PV technology in the developing world. Likewise, the government subsidy policy of 2013 on energy-efficient home appliances has boomed the sale of these energy-efficient products in China (Wang et al. 2017b).

The aforementioned literature shows that there is a dire need to empirically investigate the government role (external factors) on efficient home appliance adoption in developing countries such as Pakistan. As per the little knowledge of researchers, the present study is a pioneer research to test the causal effect of policy and propaganda in the adoption of home appliance (photovoltaic) in Pakistan. Secondly, as per the recommendation of Baron and Kenny (1986), the moderator can be incorporated in the conceptual framework once the prior results were inconsistent among the exogenous and endogenous variables. The prior studies have reported the inconsistent results among the relationship of attitude and purchase intention and provided an opportunity for the researchers to re-test that inconsistent relationship of attitude and purchase intention. Thirdly, the present study proposes policy and propaganda as a moderator among the relationship of attitude and purchase intention by taking from the contingency theory. In contingency theory, the relationship among the exogenous and endogenous variables is contingent or independent on another third variable. Consequently, the policy and propaganda were introduced as a moderator to better understand and avoid misleading conclusions related to contingency relationships (attitude and purchase intention). Fourthly, public awareness campaigns such as public service messages, public education, and energy-efficient labels have changed consumers’ knowledge, attitude, and awareness level regarding energy-efficient products. Researchers have also found that PP can influence the adoption of different energy products such as energy-efficient home appliances (Yang and Zhao 2015), energy-efficient automobiles (Wang et al. 2017a) but recently Song et al. (2019b) have argued that policy and propaganda moderates the consumption behavior regarding the adoption of energy-efficient home appliances. Furthermore, a recent study from Malaysia has found that government support in the form of policy and propaganda is needed to trigger the acceptance of solar PV technology (Ahmad et al. 2017). Relying on the literature the following hypothesis is formulated;

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Policy and Propaganda moderate the relationship between attitude and purchase intention of consumers toward using solar PV technology.

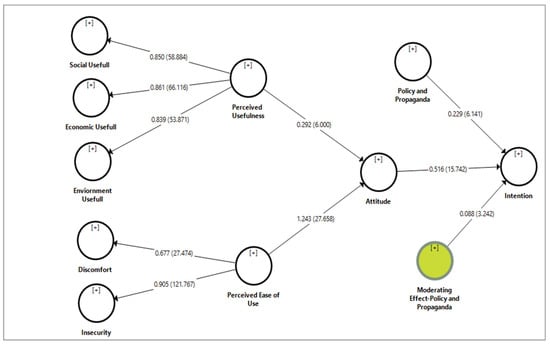

Based on the above discussion a conceptual framework for DTAM is developed, indicating positive effects of PU and PEOU on consumer’s attitudes which affect purchase intention regarding solar PV technology in Pakistan. Moreover, Policy and Propaganda moderates the relationship between consumer attitude and purchase intention (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual Framework.

3. Materials and Methods

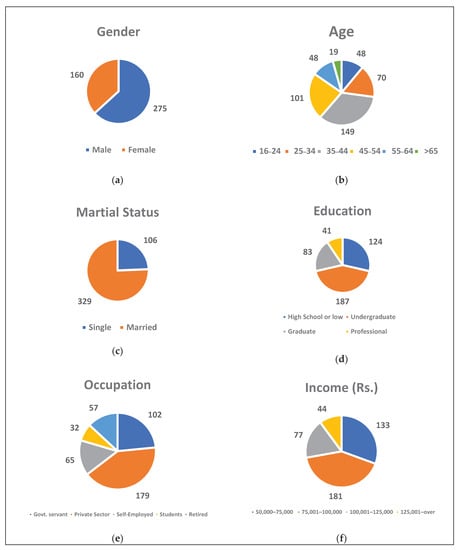

Pakistan was chosen as a case for this study due to two main facts. First, the country’s energy infrastructure heavily depends on the costly non-renewable sources of energy, and the use of renewable energy is quite meager. Second, Pakistan is among the hardest hit countries by climate change therefore it is imperative to reduce carbon emissions for a sustainable ecosystem. The sampling population of the study is comprised of a broad spectrum of households of four metropolitan cities of Punjab (Lahore, Multan, Faisalabad, and Sargodha). One of the main reasons for selecting these cities is the increasing demand for green products in metropolitan cities (Ali et al. 2019b). The data was collected through a self-administered questionnaire, which was divided into two sections. Demographic information such as gender, age, education, etc. was represented (in Figure 3 and Table A1). Similarly, the exogenous and endogenous constructs that were adopted from the previous literature are provided in Appendix A. Three items of social dimension were adapted from (Hamari et al. 2016; Garay et al. 2019); three items of economic dimension was adapted from (Garay et al. 2019); three items of environment dimension were adapted from (Ed Collom 2007; Hamari et al. 2016). Likewise, three items of insecurity and three items of discomfort were adapted from (Parasuraman 2000); four questions of attitude were adopted from (Ahmad et al. 2017); five items of purchase intention were measured from (Paul et al. 2016); three items of policy and propaganda was adapted from (Song et al. 2019a). Each item was measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = ‘strongly agree”. Non-probability sampling is more appropriate when it is problematic to access the complete sample frame (Danish et al. 2019) as this sampling technique is more suitable for theoretical generalizability (Calder et al. 1981). So purposive sampling was used to select the sample. Price is considered a key determinant in pro-environmental consumption behavior (Issock Issock et al. 2018) which makes consumers’ income a crucial factor while buying green technologies or in our case solar PV technology (Ali et al. 2019b). Therefore, middle-class residents, with an income level of around 300 $ (PKR 50,000), were chosen for a sample (Adil 2017). The sampling size was determined by the suggestion of Churchill and Iacobucci (2006), who states that the sample size should range between 200–500 in behavioral studies. Therefore, 700 questionnaires were distributed to get an appropriate sample size as Nulty (2008) found that response rate in behavioral studies is between 40% to 60%. Out of these 700 questionnaires, a total of 489 questionnaires were returned and after screening around 435 were found usable. Hence our response rate is 62.14% which is consistent with the study of Mellahi and Harris (2016) who found that response rate in subcontinent to be around 52.68%.

Figure 3.

Demographics Profiles of Respondents ((a) Gender; (b) Age; (c) Marital Status; (d) Education Level; (e) Occupation; (f) Income).

4. Empirical Strategy and Results

Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a second-generation multivariate statistical tool to measure structural relationships (Hair et al. 2014). SEM has several advantages over first-generation models in terms of efficiency, accuracy, and covariance (Richter et al. 2016; Malhotra et al. 2006). According to Zahid and Din (2019) It includes a series of empirical tests such as factor analysis, discriminant analysis, and regression or path analysis through which the structural relationship of observed and latent variables can be examined (Chin and Marcoulides 1998). Its ability to measure relationships of exogenous and endogenous variables simultaneously makes it popular in social sciences and behavioral studies (Cheah et al. 2019). SEM is distinguished into two types, i.e., variance-based (VB-SEM or PLS-SEM) and covariance-based (CB-SEM) (Chin and Newsted 1999; Ali et al. 2019a). PLS-SEM is considered to be a Silver Bullet or Holy Grail due to its proficiency in measuring complex relationships in the model (Hair et al. 2011). That is why most researchers prefer PLS-SEM over CB-SEM because it is a more sophisticated technique to unleash complex social phenomena. Moreover, Ramli et al. (2018) reported that PLS-SEM is more useful in exploratory studies and generate instruments which improve the accuracy of the empirical outcomes. As these’ empirical attributes are desirable to examine the hypothesis of this therefore we employ PLS-SEM for data analysis by using Smart PLS 3.0 software (Ringle et al. 2015). PLS-SEM followed a dual-stage assessment approach, which includes the assessment of the measurement model as well as the evaluation of the structural model. The measurement model’s evaluation includes validity and constructs reliability tests, while the assessment of the structural model includes testing the significance level of the hypotheses.

4.1. Measurement Model-Based Assessment

The measurement model is assessed through construct reliability and validity tests. Construct reliability includes items’ reliability, which was measured by outer loadings. Whereas, the internal consistency and reliability were measured through the composite reliability analysis. Validity tests include convergent validity measured through average variance extracted (AVE) and discriminant validity measured through Heterotrait–Monotrait ratios (HTMT) (Akbar et al. 2019). All outer loadings meet the recommended value of 0.5 (Hair et al. 2014). Moreover, composite reliability is well above the threshold value of 0.7 and AVE also exceeds the cut-off value of 0.5 (Anderson and Gerbing 1988) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Measurement model-based assessment.

HTMT is the most robust tool for assessing discriminant validity because the results Fornell–Larcker criteria are still under debate (Hair et al. 2014). So HTMT criteria were employed for discriminant validity assessment. Gold et al. (2001) suggest that if HTMT value is above 0.90, there are specific issues of validity, while Kline (2015) indicates that if values are higher than 0.85, then there are issues of discriminant validity. Table 3 shows that all values are lower than 0.85, which satisfies the discriminant validity criteria.

Table 3.

Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT).

4.2. Structural Model-Based Assessment

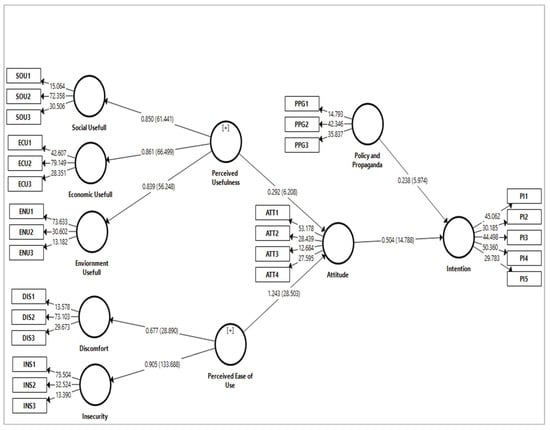

Below is the pictorial demonstration of SEM-based analysis.

A structural model was performed in the second stage after completing the first step, i.e., measurement model assessment. Structural model assessment includes path coefficients (β values), t values, coefficient of determination (R2), effect size (f2), and predictive relevance (Q2). β values were measured by the bootstrapping method (5000 re-sample). Empirical results indicate the acceptance of all four hypotheses (Table 4 and Table 5, Figure 4). The results show that Perceived usefulness (β = 0.292, t = 6.208 > 1.64, p < 0.05), perceived ease of use (β = 1.243, t = 28.503 > 1.64, p < 0.05) has significant impact on consumer attitude. Consumer attitude (β = 0.504, t = 14.788 > 1.64, p < 0.05) has a significant impact on consumer’s purchase intention to buy solar PV technology. Similarly, policy and propaganda moderates the association between consumer attitude and purchase intention (β = 0.088, t = 3.242 > 1.64, p < 0.05). The coefficient of determination indicates the total variation in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables in a given model. The R2 value for the model is 0.402. This reflects that the model has substantial explanatory power as Cohen (1988) suggested that an R2 value of greater than 0.40 is considered quite substantial. Effect size f2 represents the impact of exogenous variables on endogenous variables (Hair et al. 2014; Akbar et al. 2019). According to Cohen (1988), the values of f2 under 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 depict a small, medium, and large effect respectively. Table 5 shows that all the variables have different effect sizes varying from medium to large. Besides, the value of Q2 is greater than 0 (Q2 = 0.345) which demonstrates that the model has predictive relevance.

Table 4.

Structural model Assessment.

Table 5.

Structural Model Assessment (Moderation).

Figure 4.

SEM results (Bootstrap).

4.3. The Moderating Role of Policy and Propaganda

The moderating effect of policy and propaganda is measured by the interaction term between the consumer attitude and purchase intention (see Figure 5 and Table 5), which is found to be significant in the model (β = 0.088, t = 3.242 > 1.64, p < 0.05). The results show that the value of R2 gets changed after incorporating the moderating variables into the proposed model. The R2 value has increased from 0.402 to 0.412. It indicates that together PEOU, PU, and PP can explain 41.2% of the variation in the endogenous variable (Consumer purchase intention). This outcome implies that the model explains additional variation in the purchase intention after including policy and propaganda, although difference is not substantial but enough to cause variations in the purchase intention of the sample consumers.

Figure 5.

Moderating effects of Policy and Propaganda.

5. Discussion

Heightened energy consumption and resulting environmental hazards coupled with the reduction in natural resources urge the need to exploit renewable energy resources for sustainable economic development. Policymakers and academicians are showing interest in the adoption of solar PV technology due to its low cost, efficiency, and sustainable energy generation features. Pakistan is one of the countries that are enriched with this energy resource but still the adoption rate of solar PV technology remains slow. Therefore, we use a decomposed technology acceptance model for a comprehensive understanding of consumer’s intentions to adopt solar PV technology in Pakistan. By using PLS-SEM, the study has unveiled that PU and PEOU positively influence consumer attitudes which ultimately influence consumers’ intention to adopt solar PV technology. Moreover, it was also found that PP moderates the relationship between attitude and purchase intention of solar PV technology.

As hypothesized, the results revealed that a relationship exists among the exogenous and endogenous variables in the present study, Therefore, all the null hypotheses have been rejected. In addition, the empirical results confirm that PU affects consumer attitude toward the adoption of solar PV technology. It means that households in Pakistan are more likely to adopt solar PV technology if they found it useful in terms of environmental protection, socially acceptable, and more economical than alternate energy resources. The price has always been a crucial factor that affects consumers’ behavior, especially in developing countries. Consumers in Pakistan are price sensitive and search for the best value for money against any product. Moreover, another reason for this result can be that developing countries are facing multifaceted environmental issues thus consumers want an environment-friendly source of energy. The finding of this research is in line with the previous studies of green consumption in Pakistan claiming that individuals adopt those products which provide the best value for money, are environment-friendly, and resonate with their social class and peer groups (Danish et al. 2019; Ali et al. 2019b). In this regard, the public policy and awareness departments should launch advertisements that propagate solar PV technology as the best value package that does not have any harmful impact on the environment. Therefore, the social acceptance and adoption rate of such technologies will increase, and consumers will have to spend less money compared to the alternate means of energy.

PEOU refers to the extent a consumer perceives convenience while using or understanding new or novel technology. The empirical result shows that PEOU positively influences consumer attitudes to adopt solar PV technology. This outcome is in line with the studies of who said the consumers are likely to adopt green technologies when they are easy to operate. However, insecurity and discomfort are found to have a negative impact on PEOU regarding the adoption of solar PV technology. This empirical outcome conjectures that residents who feel insecurity and discomfort while using a novel technology may not involve in the adoption of such technology. Therefore, the government departments should initiate different public awareness and training programs so that people can become savvy to use such energy products. Moreover, different product manuals and installation tutorials can be handy for the installation and use of these technologies. social media mix can be used to achieve this objective (Menegaki 2012) Nevertheless, an effective warranty mechanism of solar PV products can also alleviate consumers’ negative perception of discomfort and insecurity.

Consumer attitude to use solar PV technology refers to consumers’ positive or negative beliefs and feelings about using such technologies. The results suggest that consumer attitude is a significant factor in the purchase intention to use solar PV technology in Pakistan. Despite of the limited literature available, the results are consistent with the previous studies of various countries such as Malaysia and European countries toward the adoption of green technology or renewable energy resources (Ahmad et al. 2017; Ali et al. 2019a). It implies that once a positive attitude is developed through PU and PEOU, then consumers are more likely to buy the solar PV products. Researchers have argued that consumers engage in the adoption of new technology when their decisions are influenced by some external factors such as policy and propaganda. Therefore, the study has examined the moderating role of policy and propaganda in the relationship between consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions.

Furthermore, empirical tests of moderation suggest that PP significantly moderates this relationship and a one percent increase has been reported in R2. The moderation effect is small but significant in the present study. In developing countries such as Pakistan, the government should design those effective policies that facilitate the consumer’s decision-making process, e.g., offering subsidies to the consumers who buy the solar PV technology. Moreover, tax rebates can be offered to the SPV manufacturing companies so that they can sell their products at low prices in Pakistan. With these subsidies, a reduction in tax rates and a conducive operating environment shall be rendered to these energy companies. As a result, the high adoption rate of solar PV technology will not only reduce environmental problems but also enhance the capability of the government to cope up with the mounting demand for household energy. Ultimately, SPV adoption can be very handy for both the households and the government as an economical and sustainable energy resource.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Increasing the proportion of renewable energy is the overall energy mix is an essential feature for the sustainable development of an economy. Besides, the deployment of renewable energy technologies can also help to meet the growing demand for energy in a developing economy such as Pakistan’s (Wang et al. 2020). This research employs a decomposed TAM model, moderated by the policy and propaganda to investigate consumer’s intention toward the adoption of solar PV technology in Pakistan. For this purpose, data was collected from the households of Pakistan through valid questionnaires. The results were obtained through the application of the PLS-SEM technique. Empirical results suggest that PU and PEOU positively and significantly influence the consumer’s attitude toward SPV technology. Subsequently, the consumer attitude positively influences consumer’s intentions to use SPV technology. Moreover, moderation of PP between consumer attitude and purchase intention was also confirmed. The possible reason for these results is that Pakistani consumers had faced an acute energy crisis, and there is still a demand-supply gap prevalent in the energy sector. Solar PV technology adoption can fulfill this energy gap, comparatively with less cost and an eco-friendly manner. Hence the household consumers have an intention to adopt this technology, though the adoption rate is relatively slow when compared with other developing countries in the region.

Keeping this in perspective, relevant public policy departments can design awareness programs for consumers to train them about the use of this technology and highlight its benefits. As a result, consumers will perceive solar PV to be more useful and feel comfortable to install and use this technology without hesitation. Moreover, the research and development departments need to develop user-friendly technologies to develop a favorable consumer attitude regarding SPV adoption. Notwithstanding, the role of favorable government policies is also very crucial to boost the adoption rate of SPV technologies. Although the Punjab government (the largest province of Pakistan) has decided to install solar systems in 12,000 schools across the province, the scope of such initiatives need to be expanded to all provinces. Furthermore, the government needs to subsidize PV technologies to enhance the use of cleaner energy resources for sustainable development. Nevertheless, tax reliefs for the foreign solar PV providers can attract foreign firms to start their operations in Pakistan. The increased competition will not only boost product efficiency but also ensure the availability of low-cost solar PV products for the consumers. Such initiatives can motivate consumers when they make a cost-benefit analysis to choose between various energy alternatives.

The present research has several noteworthy practical and theoretical implications yet still have a few limitations. First, social demographics play a vital role in the consumer decision-making process. Future research can check on the role of demographics as control variables to assess solar PV adoption in the context of developing economies. Second, the study focused only on household consumers. Therefore, understanding the supply side constraints can also help in the promotion of solar PV technologies. Third, the study was limited only to the intentions of the consumer toward the adoption of SPV technology. No doubt intentions are a good predictor of behavior, yet still, some researchers observed a gap between consumer intentions and actual behavior. Therefore, future studies in this domain can investigate the actual buying behavior of consumers regarding solar PV technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization & Writing the original manuscript: S.A.; Data Collection and Analysis: H.M.U.J. and S.A.; review and editing: A.A., M.D.; Supervision P.P.; Funding P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The open access of this research is funded by the SPEV project 2020 at the Faculty of Informatics and Management, University of Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Perceived usefulness (Social) | (Garay et al. 2019) |

| SOCI1 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to contribute something to society |

| SOCI2 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to help those that need fossil fuels more than me |

| SOCI3 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to do something for others |

| (Economic) | (Wang et al. 2017b; Garay et al. 2019) |

| ECON1 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to save money |

| ECON2 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to reduce costs |

| ECON3 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to obtain profits |

| (Environment) | (Hamari et al. 2016; Garay et al. 2019) |

| ENVI1 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to reduce emission of greenhouse gases |

| ENVI2 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to save natural resources |

| ENVI3 | Introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house allows me to have an ecological behavior |

| Perceived ease of use (insecurity) | (Parasuraman 2000) |

| PR1 | I am worried that solar photovoltaic technology is not providing the expected benefits |

| PR2 | I am worried that solar photovoltaic technology is not reliable and dependable |

| PR3 | I am worried about the ongoing maintenance of solar photovoltaic technology |

| Discomfort | (Parasuraman 2000) |

| PC1 | Learning how to use solar photovoltaic technology is difficult for me |

| PC2 | Solar photovoltaic technology requires a lot of knowledge |

| PC3 | I find solar photovoltaic technology difficult to use |

| Attitude | (Ahmad et al. 2017) |

| ATTI1 | I find solar electricity to be a major source of electricity in the future |

| ATTI2 | I believe it is good (or the right time) to use solar electricity in my house |

| ATTI3 | I like the idea of using a clean source of electricity in my house |

| ATTI4 | Overall I think I will enjoy solar technology as a source of electricity in my house |

| Policy and Progodanda | (Song et al. 2019b) |

| PPG1 | In the process of introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house before, I heard about relevant government incentive policy. |

| PPG2 | Policy advocacy of renewable energy will motivate me to introduce solar photovoltaic technology in my house |

| PPG3 | Domestic advertising and media propagandas advocate households to introduce solar photovoltaic technology. |

| Behavioral intention | (Paul et al. 2016) |

| BINT1 | I intend to use solar electricity for my house |

| BINT2 | I plan to have some RE technology for my house for the generation of electricity |

| BINT3 | I am planning to have solar electricity for my house in 3–4 years; 2–3 years; before 1 year |

| BINT4 | The probability of introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house is very high. |

| BINT5 | I will introducing solar photovoltaic technology in my house in a more effective way. |

Appendix B

Table A1.

Demographic Profile of respondents.

Table A1.

Demographic Profile of respondents.

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 275 | 63.2 |

| Female | 160 | 36.8 | |

| Age | 16–24 | 48 | 11.0 |

| 25–34 | 70 | 16.1 | |

| 35–44 | 149 | 34.3 | |

| 45–54 | 101 | 23.2 | |

| 55–64 | 48 | 11.0 | |

| >65 | 19 | 4.4 | |

| Martial | Single | 106 | 24.4 |

| Married | 329 | 75.6 | |

| Education | Intermediate or below | 124 | 28.5 |

| Undergraduate | 187 | 43.0 | |

| Graduate | 83 | 19.1 | |

| Professional | 41 | 9.4 | |

| Occupation | Government Sector | 102 | 23.4 |

| Private Sector | 179 | 41.2 | |

| Self-Employed | 65 | 15.0 | |

| Student | 32 | 7.3 | |

| Retired | 57 | 13.1 | |

| Income | 50,000–75,000 | 133 | 30.6 |

| Rs. | 75,001–100,000 | 181 | 41.6 |

| 100,001–125,000 | 77 | 17.7 | |

| 125,001–over | 44 | 10.1 |

References

- Acheampong, Patrick, Zhiwen Li, Henry Asante Antwi, Anthony Akai, Acheampong Otoo, and William Gyasi Mensah. 2017. Hybridizing an Extended Technology Readiness Index with Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to Predict E-Payment Adoption in Ghana. American Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 5: 172–84. [Google Scholar]

- Adil, Adnan. 2017. Our Middle Class|Opinion|Thenews.Com.Pk|Karachi. THE NEWS. Available online: https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/210660-Our-middle-class (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Ahmad, Salman, Razman bin Mat Tahar, Jack Kie Cheng, and Liu Yao. 2017. Public Acceptance of Residential Solar Photovoltaic Technology in Malaysia. PSU Research Review 1: 242–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Thomas J. Madden. 1986. Prediction of Goal-Directed Behavior: Attitudes, Intentions, and Perceived Behavioral Control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 22: 453–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, Ahsan, Irfan Ullah Alam Rehman, Muhammad Zeeshan, and Fakhr E. Alam Afridi. 2020a. Unraveling the Dynamic Nexus Between Trade Liberalization, Energy Consumption, CO2 Emissions, and Health Expenditure in Southeast Asian Countries. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy 13: 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, Ahsan, Saqib Ali, Muhammad Azeem Ahmad, Minhas Akbar, and Muhammad Danish. 2019. Understanding the Antecedents of Organic Food Consumption in Pakistan: Moderating Role of Food Neophobia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, Minhas, Ammar Hussain, Ahsan Akbar, and Irfan Ullah. 2020b. The dynamic association between healthcare spending, CO2 emissions, and human development index in OECD countries: Evidence from panel VAR model. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Akman, Ibrahim, and Alok Mishra. 2014. Green Information Technology Practices among IT Professionals: Theory of Planned Behavior Perspective. Problems of Sustainable Development 9: 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, Syed Shah, and M. Rashid. 2012. Intention to Use Renewable Energy: Mediating Role of Attitude. Energy Research Journal 3: 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Saqib, Habib Ullah, Minhas Akbar, Waheed Akhtar, and Hasan Zahid. 2019a. Determinants of Consumer Intentions to Purchase Energy-Saving Household Products in Pakistan. Sustainability 11: 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Saqib, Muhammad Danish, Faiz Muhammad Khuwaja, and Muhammad Shoaib Sajjad. 2019b. The Intention to Adopt Green IT Products in Pakistan: Driven by the Modified Theory of Consumption Values. Environments 6: 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, James C., and David W. Gerbing. 1988. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychlogical Bulletin 103: 411–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, Gee Woo, Robert W. Zmud, Young Gul Kim, and Jae Nam Lee. 2005. Behavioral Intention Formation in Knowledge Sharing: Examining the Roles of Extrinsic Motivators, Social-Psychological Forces, and Organizational Climate. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems 29: 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, Michael E. 1990. What Is Intention. In Intentions in Communication. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, Bobby J., Lynn W. Phillips, and Alice M. Tybout. 1981. Designing Research for Application. Journal of Consumer Research 8: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, Jun Hwa, Hiram Ting, T. Ramayah, Mumtaz Ali Memon, Tat Huei Cham, and Enrico Ciavolino. 2019. A Comparison of Five Reflective–Formative Estimation Approaches: Reconsideration and Recommendations for Tourism Research. Quality and Quantity 53: 1421–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Jacky, and Shu Chiang Lin. 2016. A Behavioral Model of Managerial Perspectives Regarding Technology Acceptance in Building Energy Management Systems. Sustainability 8: 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Wynne, and G. Marcoulides. 1998. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, Wynne W., and Peter R. Newsted. 1999. Structural Equation Modeling Analysis with Small Samples Using Partial Least Square. MIS Quarterly 22: 307–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ching-Ter, Chang, Jeyhun Hajiyev, and Chia Rong Su. 2017. Examining the Students’ Behavioral Intention to Use e-Learning in Azerbaijan? The General Extended Technology Acceptance Model for E-Learning Approach. Computers and Education 111: 128–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, Gilbert A., and Dawn Iacobucci. 2006. Marketing Research: Methodological Foundations. New York: Dryden Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Mahwah: Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Collom, Ed. 2007. The Motivations, Engagement, Satisfaction, Outcomes, and Demographics of Time Bank Participants: Survey Findings from a U.S. System. International Journal of Community Currency Research 11: 36–83. [Google Scholar]

- Danish, Muhammad, Saqib Ali, Muhammad Azeem Ahmad, and Hasan Zahid. 2019. The Influencing Factors on Choice Behavior Regarding Green Electronic Products: Based on the Green Perceived Value Model. Economies 7: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Fred D. 1989. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems 13: 319–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, Sanjeev, and Kenneth L. Kraemer. 2000. Information Technology and Productivity: Evidence from Country-Level Data. Management Science 46: 548–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, David, Marie-Lena Hutfils, and Maik Winges. 2019. Global Climate Risk Index 2019. Who Suffers Most From Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2017 and 1998 to 2017. Available online: https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/germanwatch.org/files/Global%20Climate%20Risk%20Index%202019_2.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2019).

- Garay, Lluís, Xavier Font, and August Corrons. 2019. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation in Tourism: An Analysis Based on the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Travel Research 58: 622–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbongli, Komlan, Yongan Xu, and Komi Mawugbe Amedjonekou. 2019. Extended Technology Acceptance Model to Predict Mobile-Based Money Acceptance and Sustainability: A Multi-Analytical Structural Equation Modeling and Neural Network Approach. Sustainability 11: 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, Andrew H., Arvind Malhotra, and H. Albert. 2001. Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems 18: 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F, Christian M Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2011. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19: 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joe F., Marko Sarstedt, Lucas Hopkins, and Volker G. Kuppelwieser. 2014. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) An Emerging Tool in Business Research. European Business Review 26: 106–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, Juho, Mimmi Sjöklint, and Antti Ukkonen. 2016. The Sharing Economy: Why People Participate in Collaborative Consumption. Jurnal Ilegal Fishing 67: 2047–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawlitschek, Florian, Timm Teubner, and Henner Gimpel. 2016. Understanding the Sharing Economy—Drivers and Impediments for Participation in Peer-to-Peer Rental. Paper presented at the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Koloa, HI, USA, January 5–8; pp. 4782–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, Iñaki, Ibon Zamanillo, and Iker Laskurain. 2013. Social Acceptance of Ocean Wave Energy: A Case Study of an OWC Shoreline Plant. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 27: 515–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Richard J., Martin Fishbein, and Icek Ajzen. 1977. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Contemporary Sociology 6: 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. 2019. World Energy Outlook. Paris: International Energy Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Irfan, Muhammad, Zhen-Yu Zhao, Munir Ahmad, and Marie Mukeshimana. 2019. Solar Energy Development in Pakistan: Barriers and Policy Recommendations. Sustainability 11: 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issock Issock, Paul Blaise, Mercy Mpinganjira, and Mornay Roberts-Lombard. 2018. Drivers of Consumer Attention to Mandatory Energy-Efficiency Labels Affixed to Home Appliances: An Emerging Market Perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 204: 672–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardooni, Roozbeh, Sumiani Binti Yusoff, and Fatimah Binti Kari. 2016. Renewable Energy Technology Acceptance in Peninsular Malaysia. Energy Policy 88: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, Hafiz Bilal, and Syed Jawad Hussain Zaidi. 2014. Energy Crisis and Potential of Solar Energy in Pakistan. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 31: 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, I. U., Abraiz Khattak, and Mati Ullah Ahsan. 2018. Solar PV Adoption for Homes (A Case of Peshawar, Pakistan). Paper presented at 2017 International Symposium on Recent Advances in Electrical Engineering (RAEE), Islamabad, Pakistan, October 24–26; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, Anjum, and Haroon Junaidi. 2013. Study of Economic Viability of Photovoltaic Electric Power for Quetta—Pakistan. Renewable Energy 50: 253–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, Nowsherwan, S. Riaz Ul Hassnain, S. Waqar Shah, and Abdul Mutlib. 2006. Identification and Removal of Barriers for Renewable Energy Technologies in Pakistan. Paper presented at 2nd International Conference on Emerging Technologies 2006, ICET 2006, Peshawar, Pakistan, November 13–14; pp. 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, Naresh K., Sung S. Kim, and Ashutosh Patil. 2006. Common Method Variance in IS Research: A Comparison of Alternative Approaches and a Reanalysis of Past Research. Managment Science 52: 1865–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangunić, Nikola, and Andrina Granić. 2015. Technology Acceptance Model: A Literature Review from 1986 to 2013. Universal Access in the Information Society 14: 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, Miriam, Oliver Roll, and Roger Elliott. 2017. Testing the Technology Readiness and Acceptance Model for Mobile Payments Across Germany and South Africa. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management 14: 1750033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellahi, Kamel, and Lloyd C. Harris. 2016. Response Rates in Business and Management Research: An Overview of Current Practice and Suggestions for Future Direction. British Journal of Management 27: 426–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegaki, Angleiki N. 2012. A Social Marketing Mix for Renewable Energy in Europe Based on Consumer Stated Preference Surveys. Renewable Energy 39: 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulty, Duncan D. 2008. The Adequacy of Response Rates to Online and Paper Surveys: What Can Be Done? Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 33: 301–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. 2000. Technology Readiness Index (Tri): A Multiple-Item Scale to Measure Readiness to Embrace New Technologies. Journal of Service Research 2: 307–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin, Ashwin Modi, and Jayesh Patel. 2016. Predicting Green Product Consumption Using Theory of Planned Behavior and Reasoned Action. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 29: 123–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, Tahir Masood, Kafait Ullah, and Maarten J. Arentsen. 2017. Factors Responsible for Solar PV Adoption at Household Level: A Case of Lahore, Pakistan. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 78: 754–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, Syed Abidur, Seyedeh Khadijeh Taghizadeh, T. Ramayah, and Mirza Mohammad Didarul Alam. 2017. Technology Acceptance among Micro-Entrepreneurs in Marginalized Social Strata: The Case of Social Innovation in Bangladesh. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 118: 236–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, Nur Ainna, Hengky Latan, and Grace T. Solovida. 2018. Determinants of Capital Structure and Firm Financial Performance—A PLS-SEM Approach: Evidence from Malaysia and Indonesia. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 71: 148–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REN21. 2020. Renewables 2020 Global Status Report. REN21 Secretariat. Available online: http://www.ren21.net/resources/publications/ (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Richter, Nicole, Gabriel Cepeda-Carrion, José Roldán, and Christian Ringle. 2016. European Management Research Using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). European Management Journal 34: 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, Christian M., Sven Wende, and Jan-Michael Becker. 2015. SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Janelle, and Gerard Joseph Fogarty. 2000. Determinants of Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use in the Technology Acceptance Model: Senior consumers’ adoption of self-service banking technologies. Academy of World Business, Marketing &Management Development Conference Proceedings 2: 122–29. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, Rashid, R. Lodhi, Ahmer Naeem, Ahsan Akbar, Amna Sami, and Fareha Dustgeer. 2013. Consumer’s attitude towards internet advertising in Pakistan. World Applied Sciences Journal 25: 623–28. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Yan, Chunan Zhao, and Ming Zhang. 2019a. Does Haze Pollution Promote the Consumption of Energy-Saving Appliances in China? An Empirical Study Based on Norm Activation Model. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 145: 220–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Yan, Shu Guo, and Ming Zhang. 2019b. Assessing Customers’ Perceived Value of the Anti-Haze Cosmetics under Haze Pollution. Science of the Total Environment 685: 753–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, Janet, and Maria Ioannou. 2010. Social Acceptance of Renewable Electricity Developments in New Zealand A Report for the Energy Efficiency and Conservation. Dunedin: University of Otago. [Google Scholar]

- Valasai, Gordhan Das, Muhammad Aslam Uqaili, Hafeez Ur Rahman Memon, Saleem Raza Samoo, Nayyar Hussain Mirjat, and Khanji Harijan. 2017. Overcoming Electricity Crisis in Pakistan: A Review of Sustainable Electricity Options. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 72: 734–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhaohua, Chenyao Zhao, Jianhua Yin, and Bin Zhang. 2017b. Purchasing Intentions of Chinese Citizens on New Energy Vehicles: How Should One Respond to Current Preferential Policy? Journal of Cleaner Production 161: 1000–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhaohua, Xiaomeng Wang, and Dongxue Guo. 2017a. Policy Implications of the Purchasing Intentions towards Energy-Efficient Appliances among China’s Urban Residents: Do Subsidies Work? Energy Policy 102: 430–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zanxin, Saqib Ali, Ahsan Akbar, and Farhan Rasool. 2020. Determining the Influencing Factors of Biogas Technology Adoption Intention in Pakistan: The Moderating Role of Social Media. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojuola, Rosemary N., and Busisiwe P. Alant. 2017. Public Perceptions about Renewable Energy Technologies in Nigeria. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 9: 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Shu, and Dingtao Zhao. 2015. Do Subsidies Work Better in Low-Income than in High-Income Families? Survey on Domestic Energy-Efficient and Renewable Energy Equipment Purchase in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 108: 841–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Cheolho. 2018. Extending the TAM for Green IT: A Normative. Computers in Human Behavior 83: 129–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Usman, Tanzeel Ur Rashid, Azhar Abbas Khosa, M. Shahid Khalil, and Muhammad Rahid. 2018. An Overview of Implemented Renewable Energy Policy of Pakistan. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 82: 654–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahari, Abdul Rahman, and Elinda Esa. 2018. Drivers and Inhibitors Adopting Renewable Energy: An Empirical Study in Malaysia. International Journal of Energy Sector Management 12: 581–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, Hasan, and Badariah Haji Din. 2019. Determinants of Intention to Adopt E-Government Services in Pakistan: An Imperative for Sustainable Development. Resources 8: 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).