Abstract

Modern traffic-monitoring systems increasingly rely on supplemental analytical data to complement video recordings, yet such data are rarely integrated into video containers without altering the original footage. This paper proposes a lightweight audio-based approach for embedding road-condition information using a Least Significant Bit (LSB) steganography framework. The method operates by serializing sensor data, encoding it into the LSB positions of synthetically generated audio, and subsequently compressing the audio track while preserving imperceptibility and video integrity. A series of controlled experiments evaluates how waveform type, sampling rate, amplitude, and frequency influence the storage efficiency and quality of WAV and FLAC stego-audio files. Additional tests examine the impact of embedding capacity and output-quality settings on compression behavior. Results reveal clear trade-offs between audio quality, data capacity, and file size, demonstrating that the proposed framework enables efficient, secure, and scalable integration of metadata into surveillance recordings. The findings establish practical guidelines for deploying LSB-based audio embedding in real traffic-monitoring environments.

1. Introduction

This section provides the context for our study. First, the motivation behind the research is presented; second, a brief system overview, the research hypotheses, and contributions are highlighted. The section is concluded with an outline of the manuscript’s structure.

1.1. Motivation

A modern surveillance system designed for visual inspection includes a network of cameras that continuously record activity on supervised traffic roads. The installed video surveillance equipment allows a real-time overview of the traffic situation. Today’s surveillance cameras are equipped with high-resolution sensors to capture fine details, which are necessary for recognizing specific objects or identifying the behavior of road users. Some camera systems include on-board data pre-processing, where filtering, segmentation, or object detection tasks can be performed. This is necessary to reduce network load and storage requirements on surveillance center servers for further data analysis. Furthermore, surveillance cameras generate a massive volume of data, so a secure and scalable storage solution and efficient compression algorithms are necessary. Compression algorithms and codecs help reduce file sizes while preserving visual information like faces, vehicle license plates, or other identifying features. In addition to storing video footage, surveillance systems are using computer vision and machine learning algorithms to transform recording into a source of information about the traffic road conditions, e.g., to detect unusual movement patterns, count vehicles or pedestrians, or automatically tag specific activities. Tagging procedures allow searching for videos according to multiple criteria, e.g., types of detected activity, not just the place and time in which they were recorded.

Equally important is maintaining the authenticity, credibility, and integrity of recorded material and rigorously enforcing privacy regulations and data protection laws. Procedures like cryptographic hashing, digital signatures, and strict chain-of-custody logging prevent unauthorized manipulation. These methods create verifiable evidence trails, ensuring that video clips remain tamper-evident and legally defensible. Access controls and encryption help protect against intentional or accidental manipulation of data content.

Apart from the video recordings, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, such as sensors and measuring instruments, collect large amounts of data in real time and provide a detailed view of the behavior of traffic participants and their status. Thanks to standardized interfaces and modular designs, these IoT devices can be rapidly updated or replaced, ensuring continuous innovation and reducing hardware obsolescence. Rigorously tested and validated Over-the-Air (OTA) updates allow system administrators to address software vulnerabilities and deploy new features without physically accessing each device. Furthermore, IoT installations must employ energy-efficient components, balancing processing power requirements for demanding tasks (e.g., video analytics or AI-driven detection) against the need to conserve power in remote or battery-operated locations.

Lastly, it is worth noting that transportation infrastructure is also a crucial component of national critical infrastructure, encompassing elements such as bridges, tunnels, highways, and traffic monitoring systems that must remain reliable and safe under all operating conditions. As these systems become increasingly digitized and interconnected, they face higher exposure to cybersecurity threats that can disrupt operations, compromise data integrity, or even endanger public safety. Ensuring an adequate level of cyber resilience is therefore essential, requiring the implementation of robust protection mechanisms, continuous monitoring, and secure data-handling practices across all components of the infrastructure. In this context, methods such as LSB (Least Significant Bit) audio steganography, although primarily intended for seamless data integration, can additionally contribute to cybersecurity by supporting mechanisms capable of detecting or preventing unauthorized data manipulation, thereby reinforcing the overall trustworthiness of traffic infrastructure monitoring systems.

1.2. The System Overview

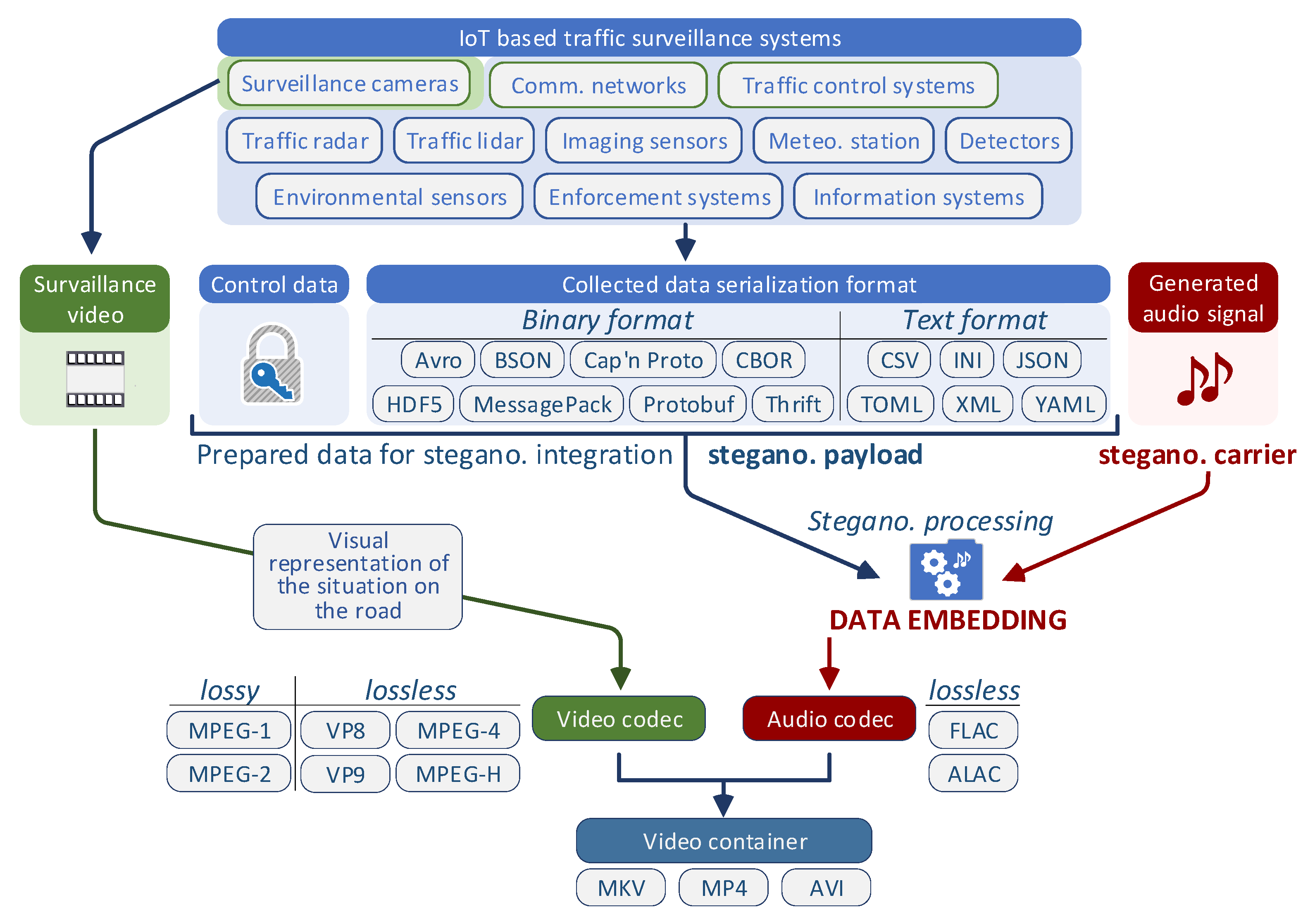

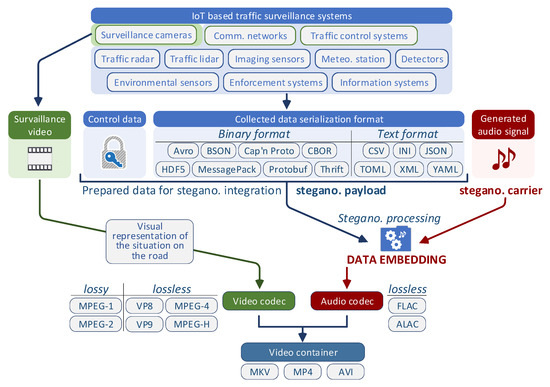

The paper presents recommendations on how to improve the road surveillance system that steganographically integrates collected road condition data into a generated audio recording (Figure 1). Measuring equipment installed on the road continuously collects data on its condition, as well as the condition of the surrounding environment. This collected data constitutes an organized set of information that can be stored in text or binary format, and its form is suitable for subsequent analysis, visualization, and export to the desired format. Thus, we focus on the process of steganographic integration of all collected road condition data into the structure of the audio recording.

Figure 1.

Steganographic integration of collected data into the traffic surveillance system records.

For our experiments, the recordings were generated and used exclusively as a carrier of steganographically integrated information. In addition to steganographic integration, the audio recordings are additionally encoded with the aim of reducing memory usage. Synthetic audio signals were generated to allow precise control over waveform shape, spectral content, amplitude, and sampling rate. This controlled environment made it possible to isolate the influence of individual audio parameters on steganographic capacity and compression efficiency. However, real surveillance audio typically contains noise, transients, and irregular spectral patterns, which may reduce embedding capacity and introduce additional perceptual constraints.

To validate the proposed concept, a series of controlled experiments was designed and conducted to evaluate the impact of audio waveform type, frequency, amplitude, sampling rate, and steganographic capacity on the resulting file size and audio quality. Finally, the encoded audio track with integrated road condition information is added to the video container and, together with the original video track, forms a unique and independent source of visual and analytical information about the road condition and its surroundings.

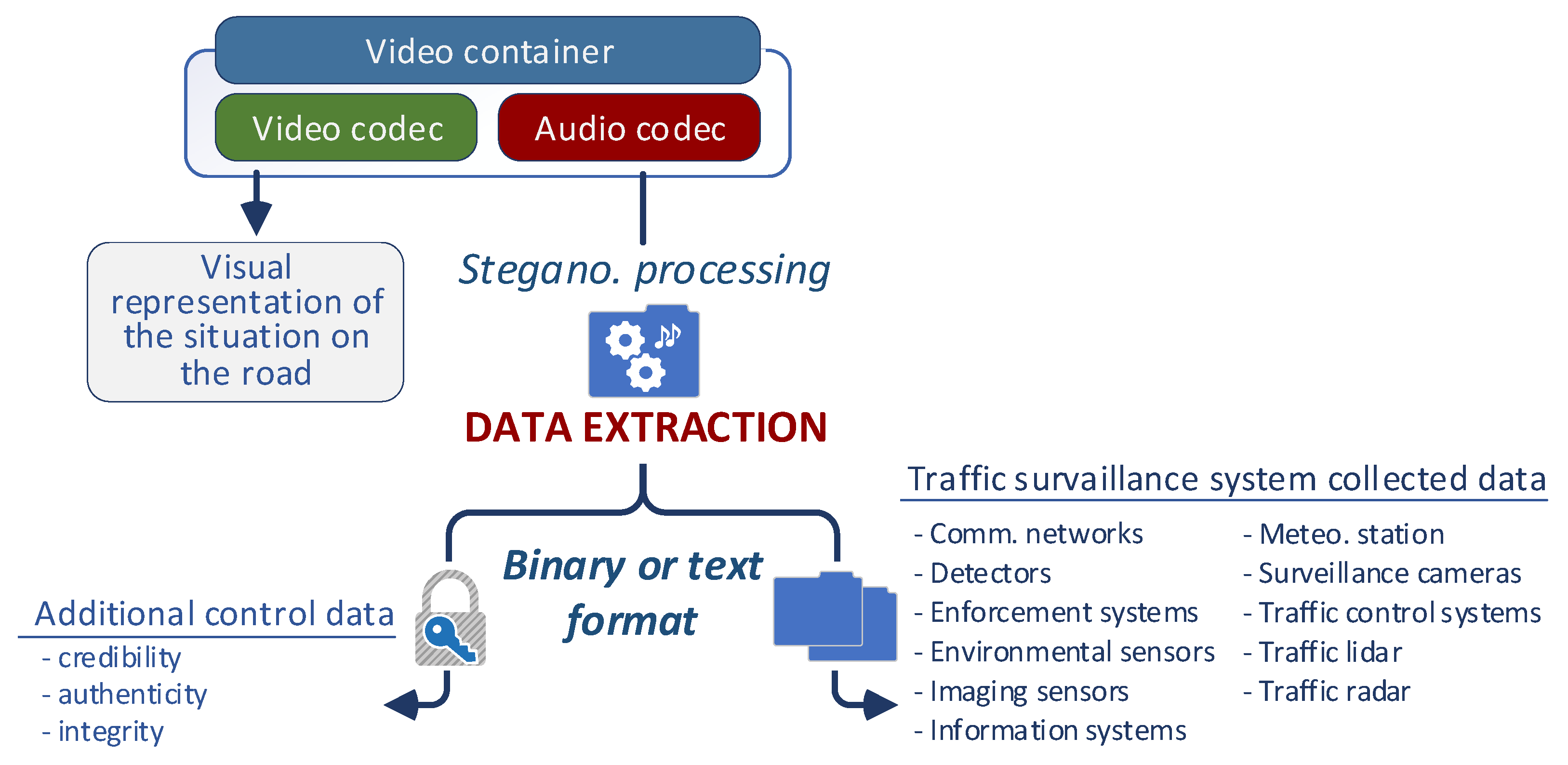

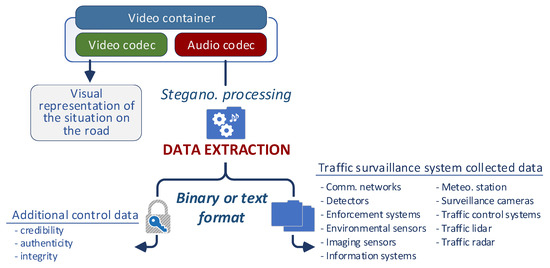

The procedure for extracting integrated data is described in Figure 2. It is important to stress that the system is designed in such a way that the video surveillance data is not manipulated in any way. The video recording remains in its original form, completely exempt from any processing or modification, regardless of its scope.

Figure 2.

Traffic surveillance system data extraction.

1.3. Research Hypotheses and Contributions

The primary aim of this research is to develop a unified and reliable source of road condition information that integrates analytical data with surveillance video while preserving the authenticity of the recorded material. The proposed approach enables secure attachment of supplementary road condition descriptors to audio streams without altering the video content, thereby improving the robustness of traffic monitoring and decision-making systems. Based on this objective, the scientific contributions of the study are reflected through the following hypotheses.

Embedding road condition data into synthetic audio signals using the LSB method preserves the audio quality of compressed FLAC output, while binary serialization formats significantly reduce storage overhead compared to equivalent text-based representations.

The choice of audio waveform and sampling rate substantially affects compression efficiency and the steganographic trade-offs between embedding capacity, resulting file size, and preserved audio quality, enabling identification of an optimal configuration that maintains data integrity.

A key scientific contribution of this work is the systematic analysis of how audio signal parameters (i.e., frequency, amplitude, and sampling rate) affect the storage efficiency of steganographically enriched audio. By quantifying these relationships, the research provides a foundation for optimizing file compression and transmission when integrating analytical data into audio streams. Furthermore, the study evaluates the influence of steganographic embedding parameters on the resulting balance between file size, data security, and audio fidelity. This analysis leads to evidence-based guidelines for selecting parameter configurations that minimize storage overhead while maintaining data integrity, confidentiality, and perceptual quality. Lastly, we want to stress that the novelty of our work does not lie in proposing a new steganographic algorithm but in performing the evaluation of LSB-based embedding for integrating analytical road-condition metadata into synthetic audio linked to surveillance video.

1.4. Structure of the Paper

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on road surveillance, audio-based monitoring, and steganography methods, highlighting the role of the LSB approach. Section 3 presents the experiment design while Section 4 discusses the results, analyzing trade-offs between file size, audio quality, and embedding capacity. Section 5 summarizes the discussion and addresses the strengths and limitations of the system. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

This chapter provides a brief overview of existing research on road surveillance systems, audio steganography algorithms, and the LSB steganography algorithm used in the paper.

2.1. Road Surveillance and Audio Steganography

Road surveillance has long relied on video systems and computer vision methods. Examples include traffic flow estimation [1] and real-time pre-event detection of accidents [2]. Although visual methods provide a high level of detail, they often suffer from limitations such as sensitivity to weather conditions or the need for high computational power.

Unlike video approaches, acoustic methods offer the advantage of independence from lighting conditions and can detect events that are not visible to cameras. Almaadeed et al. developed a method for automatic classification of audio events for surveillance purposes [3], while Szwoch and Czyzewski demonstrated the possibility of detecting vehicles based on sound intensity [4]. Further studies include intelligent acoustic sensors for traffic noise (“Traffic Ear”) [5], machine learning applied to acoustic monitoring [6], and systems for detecting emergency vehicle sirens and road noise in large cities [7]. In addition to individual methods, important contributions have been made through reviews and systematic studies. Alías and Alsina-Pagès [8] provided a comprehensive review of wireless acoustic sensor networks for environmental noise monitoring, which represents a foundation for the implementation of scalable acoustic surveillance systems in urban road networks.

To validate methods, open datasets and international challenges are increasingly being used. The DCASE Challenge 2024 provided a benchmark for acoustic-based vehicle counting by type and direction [9]. The most recent contribution is the MELAUDIS dataset [10], which enables researchers to test algorithms on a large scale of real-world data, thus promoting standardization and comparability of results.

Although previous studies have significantly advanced audio and multimodal traffic surveillance, several limitations remain. The focus is mainly on event detection and classification, but not on secure data integration and transmission. There is a lack of research exploring discrete methods of audio data encoding for further analysis, while the integration of data collected through acoustic sensors into robust communication systems remains an open question. The proposed work, therefore, introduces the use of LSB audio steganography for the integration and secure transmission of data that may be collected, for example, through acoustic road surveillance. Such an approach complements existing research [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10] by enabling reliable data exchange between distributed sensors, preserving the integrity and privacy of information, and linking acoustic methods with new techniques for hiding data in audio signals.

The application of audio steganography is the topic of a significant number of scientific papers. The development of various algorithms for audio steganography began in the mid-1990s. One of the most cited works covers a range of steganography methods in digital media [11]. It explains general techniques for hiding data in images, audio, and text, discussing trade-offs between capacity and robustness and their use in copyright protection and authentication. The paper describes the functioning of audio steganography algorithms such as LSB, Phase Coding, and Spread Spectrum (SS). D. Gruhl et al. introduce an echo-hiding audio steganography algorithm, where imperceptible echoes embed data in audio with low distortion [12]. Delforouzi and Pooyan are presenting a wavelet-based method using the integer wavelet transform to adaptively embed encrypted data with high payload and transparency [13]. Furthermore, Chen et al. are describing the quantization index modulation (QIM) algorithm and its improved version DC-QIM, which achieve near-optimal trade-offs between rate, distortion, and robustness, making them effective for copyright, covert communication, and hybrid broadcasting [14]. Dengpan et al. propose a generative adversarial network (GAN) based approach with encoder, decoder, and discriminator networks that produce high-quality steganographic audio, robust against noise and steganalysis [15].

2.2. The LSB Method

In ref. [16,17], the authors describe traditional audio steganography, which can be implemented in three primary domains: the time domain, the transform domain, and the compression domain. In ref. [16], a model for coverless steganography is proposed, utilizing GANs for direct synthesis of stego-audio signals. This approach avoids modifying an existing audio signal, thereby reducing the risk of hidden data detection.

In the time domain, the most widely used method is LSB steganography [18], where the least significant bit of an audio sample’s value is replaced with a secret bit. Other common audio steganography techniques in this domain include echo steganography [19], which exploits the masking effect of the human auditory system; spread spectrum steganography [20], where a narrowband information signal is spread over a wide frequency range; and quantization index modulation (QIM) steganography, which treats the secret message as a quantization index [21].

In ref. [22], a general model for protecting confidential information by hiding it within other innocent information (such as images or audio files) is presented. These files correspond to different types of data (text, image, or audio). Their information hiding model is based on using LSB techniques, ensuring that an attacker remains unaware of the existence of any hidden message. The experimental results of their proposed approach demonstrated a high level of security and transparency compared to previously proposed methods.

As noted above, the LSB method involves replacing the least significant bits of audio samples with the bits of secret information. Due to the small changes in signal amplitude, these modifications are almost imperceptible to the human ear, making the LSB method popular and widely used for data hiding in audio files. For this reason, the LSB method is employed in this research to carry out audio steganographic integration of collected data within an audio recording as part of a surveillance video. However, the basic LSB method can be vulnerable to various attacks due to its predictability and limited robustness. Thus, the following section analyzes existing research aimed at improving security, robustness, capacity, and minimizing distortion of the audio signal when applying the LSB method.

2.3. Enhancing the Security of the LSB Method

In ref. [23], the integration of the ChaCha20 stream cipher with the LSB method is proposed to improve the security of data hiding in audio files. By using RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) public keys for message encryption, secure communication between the sender and receiver is ensured. The evaluation results show that this method provides better security and resistance to steganalytical attacks. The LSB algorithm was applied to an audio file to hide data during transmission in ref. [24]. The algorithm used in this study proved to be one of the simplest methods for securing data through audio steganography. The method employed the LSB technique with audio files as the stego-object for final implementation in the Java programming language. Experimental results demonstrated that this method is adequate for implementing steganography, with high accuracy in the stego-objects, showing excellent quality and improved processing time. In ref. [25], a modification of the classical LSB method is proposed by using the XOR operation instead of the conventional OR operation and incorporating a secret encryption key during the insertion of the secret text into the audio file. This approach enhances the security of data transmission and makes it more difficult to detect hidden information without authorization.

2.4. Increasing the Robustness of the LSB Method

El-Khamy et al. in ref. [26] use a method for audio steganography to improve capacity, security, and robustness by utilizing two levels of integer wave transformation and modifying the wavelet and chaotic map coefficients. This scheme achieved a hiding capacity of 25% of the host image and a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 44.6 dB. Furthermore, in ref. [16], the authors propose a coverless audio steganography model for concealing secret sounds. The stego-audio is directly synthesized with their model, which is based on the WaveGAN framework. The extractor is carefully designed for reconstructing the secret sound and contains resolution blocks for learning different resolution features. Experimental results showed that current steganalysis methods have difficulty detecting the presence of the secret in the stego-sound generated by their method, as there is no cover sound.

An overview of extensive research on audio steganography based on the LSB method is provided in ref. [27]. The authors emphasize that improvements such as better preprocessing, embedding, extraction, and message validation are needed to enhance message integrity, confidentiality, and robustness. In ref. [28], an approach for hiding encrypted text files using LSB image steganography in color is presented, applying a low-complexity XOR operation on the most significant bits in 24-bit color images. The authors in ref. [29] explore the integration of biometric data and steganography, including LSB methods. The research emphasizes the importance of robust techniques for protecting sensitive information and proposes combining steganography with other security measures to increase resilience against attacks. In ref. [30], the security aspects of VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) communication are considered, including the use of the LSB method for data hiding. The research highlights the need for more robust techniques capable of withstanding various attacks and detection methods.

2.5. Increasing Capacity and Reducing Distortion

The steganography capacity can be measured from two perspectives: one is that it can reach 50% of the stego-sound in terms of sample size, while the other is that 22–37 bits can be hidden in a two-second stego-sound from the semantics. In ref. [31], a new steganography method is proposed that reduces the number of modified bits per pixel. Although the focus is on images, the approach of combining LSB and inverse LSB pairing can be adapted for audio signals to increase the data hiding capacity with minimal distortion.

The authors of [32] propose an LSB coding scheme that reduces distortion during embedding and increases the capacity for secret text. By using higher layers for LSB, distortion in the host audio signal is reduced. In ref. [33], the increase in data hiding capacity is explored using multiple LSB approaches combined with Improved Gray Quantization (IGQ). This approach allows for embedding a larger amount of secret data while maintaining sound quality. In ref. [34], the authors introduce the Josephus permutation into the LSB technique to improve randomness and security. Although the research is focused on images, the concepts can also be applied to audio steganography to reduce predictability and increase capacity.

Binny et al. in ref. [35] address the technique of embedding textual information in audio using the LSB algorithm. In the proposed method, each audio sample is converted into bits, and then the secret text is embedded into them. This approach enables efficient information hiding with minimal distortion of the audio signal. In ref. [36], the advantages of LSB encoding, such as high capacity and low complexity, are emphasized, but the issue of predictability is also noted. Due to the size and redundancy of the data, audio files are ideal for steganography as they allow the embedding of a large amount of secret information and easy transmission of the signal through various communication channels.

2.6. Identified Research Gap

Existing research on LSB-based audio steganography predominantly focuses on improving security, robustness, embedding capacity, and audio quality through the use of encryption schemes, enhanced quantization strategies, and optimized embedding algorithms. These developments aim to increase resistance to manipulation and minimize perceptual distortion, making LSB-based systems more secure and suitable for general-purpose data protection. However, the dominant research direction prioritizes strengthening LSB steganography, whereas very few studies examine scenarios in which the inherent fragility of the LSB method is not a limitation but a functional advantage.

At the same time, the available literature does not consider the use of LSB audio steganography within integrated traffic surveillance ecosystems, where audio tracks serve as auxiliary carriers of analytical metadata linked to recorded video. In such environments, characterized by constrained computational resources, high data throughput, and strict requirements on the authenticity of recorded material, LSB offers several unique advantages: extremely low computational overhead, high data capacity, and sensitivity to manipulation that can serve as an indicator of tampering.

Despite these favorable properties, no existing work systematically investigates how LSB audio steganography behaves when used not for secure concealment, but for integrating analytical road condition data into synthetic audio signals linked to surveillance video, particularly in the context of intelligent transportation systems. The literature does not address how audio waveform characteristics, sampling rates, compression algorithms, or embedded data structures influence storage efficiency, data integrity, and perceptual quality when LSB is applied for metadata augmentation rather than covert communication.

3. Experiment Description

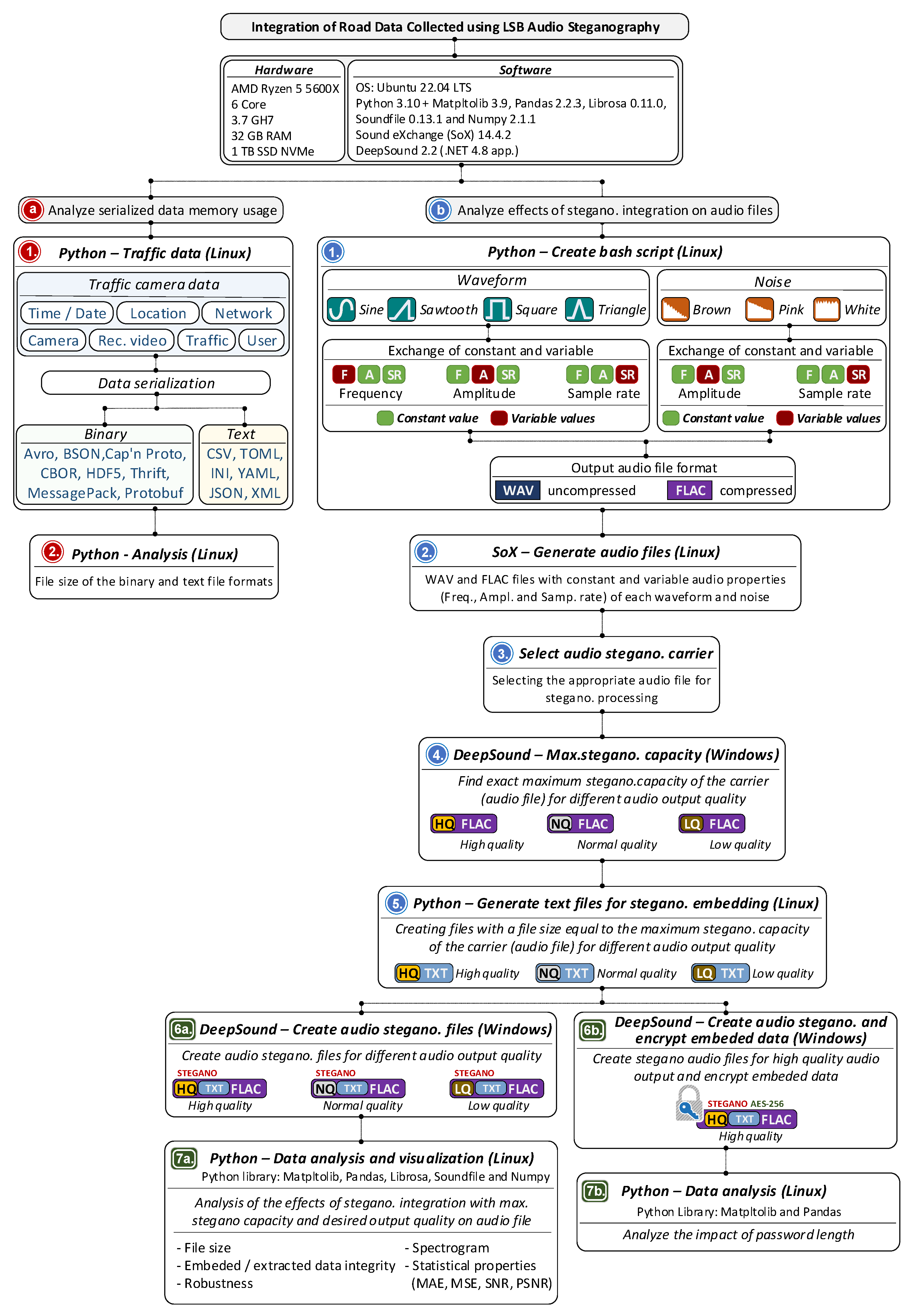

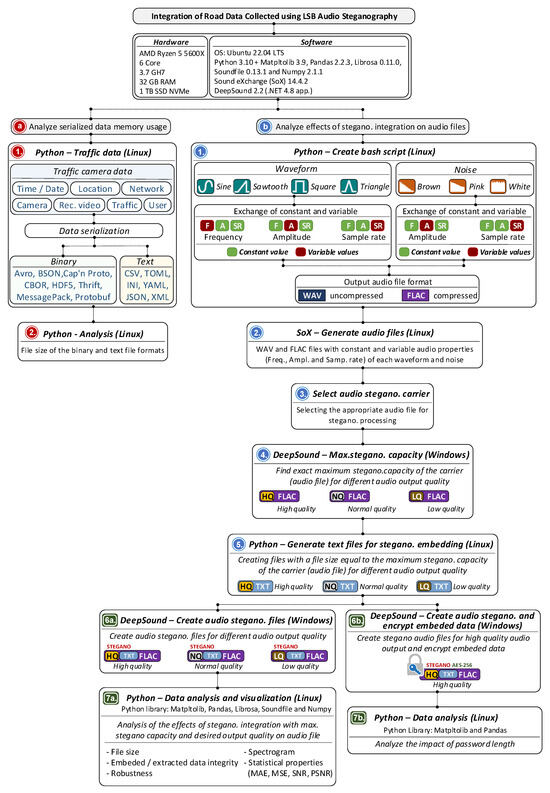

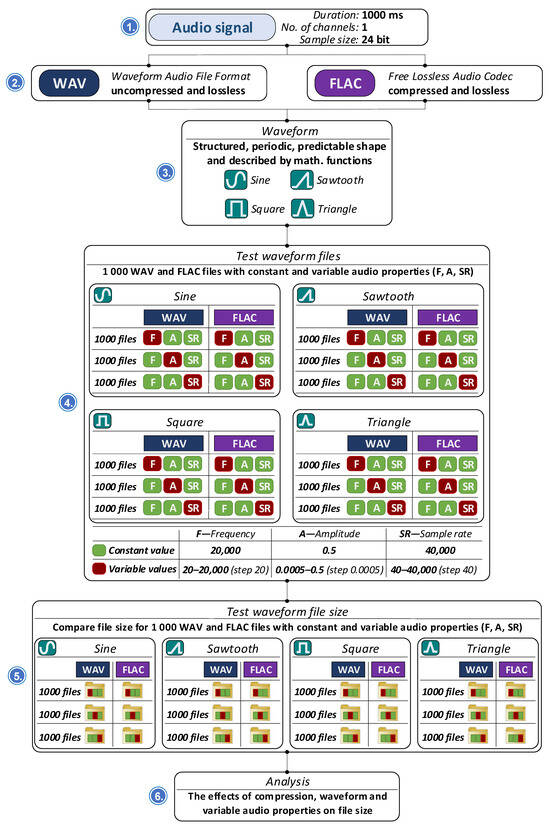

To evaluate the effectiveness of the steganographic integration system within audio recordings, a comprehensive series of tests was conducted, focusing on various aspects of data storage, audio processing, and compression behavior. Figure 3 summarizes the experiment workflow, with added information about the hardware and software used.

Figure 3.

Summary of the experiment workflow.

The initial phase of testing examined memory consumption associated with different frequently used data formats. Specifically, eight recordings were analyzed in binary format and six in textual format, with the primary objective of comparing memory usage between these two methods of data representation and storage. Subsequent tests shifted focus toward analyzing the memory footprint of the audio files themselves, which served as carriers of the steganographically integrated data. These tests explored how different parameters influence the final size of audio files, particularly in two widely used formats: WAV (uncompressed) [37] and FLAC (compressed) [38]. The influence of waveform type was assessed using standard signal forms, including sine, triangle, square, and sawtooth waveforms. In parallel, the impact of various noise types (namely, white, pink, and brown) on file size was investigated under identical format conditions. Further experimentation addressed the effects of steganographic embedding under a range of controlled conditions. One aspect of this analysis considered the scenario in which the full steganographic capacity of an audio file was utilized, while maintaining a defined level of audio quality.

As seen from Figure 3, the research encompassed an assessment of the memory footprint of serialized road-condition data, the selection of an appropriate audio format for steganographic embedding, and an examination of the effects of steganographic processing on audio quality, embedding capacity, robustness, encryption characteristics, data structure, memory usage, and the speed of data integration and extraction.

3.1. Hardware and Software Environment

The experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with a Ryzen 5 5600X processor, 32 GB of RAM, and a 1 TB NVMe SSD, operating in a dual-boot configuration with two operating systems. Ubuntu 22.04 was used for generating audio and textual data, as well as for performing analytical and visualization procedures, whereas Windows 11 Pro served as the environment for steganographic processing using the DeepSound 2.2 [39] application. Supplementary tools included Sound eXchange (SoX) 14.4.2 [40] for audio signal generation and Python 3.10 [41], accompanied by the Matplotlib 3.9 [42], Pandas 2.2.3. [43], Librosa 0.11.0. [44], SoundFile 0.13.0. [45], and NumPy 2.1.1. [46] libraries.

3.2. LSB-Based Audio Steganography Algorithm

Audio steganography is a technique that embeds additional information into an audio signal in a way that remains imperceptible to human listeners. The most widely adopted approach in this domain is LSB substitution, in which selected low-order bits of audio samples are replaced with the bits of a hidden message. Because such modifications introduce only minimal changes to the waveform, the audio remains fully functional while carrying supplemental data. LSB-based steganography is straightforward to implement, requires minimal computational resources, and in its basic form offers a high embedding capacity relative to more complex techniques. However, it is also known to be sensitive to compression and sample-level modifications, making it less robust than advanced steganographic schemes unless complemented with cryptographic protection or controlled processing conditions.

In the context of traffic surveillance, the LSB approach enables sensor-derived analytical information, such as traffic flow statistics, environmental readings, and metadata [47], to be embedded directly into an audio stream associated with a video recording. This provides a unified and temporally synchronized medium for both visual and analytical content without altering the original video track. Embedding data within audio also reduces transmission overhead, as no additional channels are required, and enhances privacy by concealing sensitive information within a carrier.

3.2.1. Embedding Procedure

As depicted in Figure 3 and discussed in Section 3.1, the implementation used in this study relies on an existing software tool, DeepSound, released in 2024. The application offers a graphical interface, supports AES-256 encryption of the embedded payload [48], and provides clear feedback on the available steganographic capacity of the selected audio file across three output-quality levels (low, medium, and high). The underlying DeepSound algorithmic principles are consistent with classical LSB-based methods extensively described in the literature [49,50], and available documentation confirms that the tool indeed implements LSB substitution [51]. Since the internal implementation of DeepSound is not publicly documented, the embedding and extraction processes are described using the classical LSB substitution model, which can be formally expressed by standard time-domain LSB equations, as given in Equations (1) and (2) [52] for the embedding and the extraction procedures, respectively.

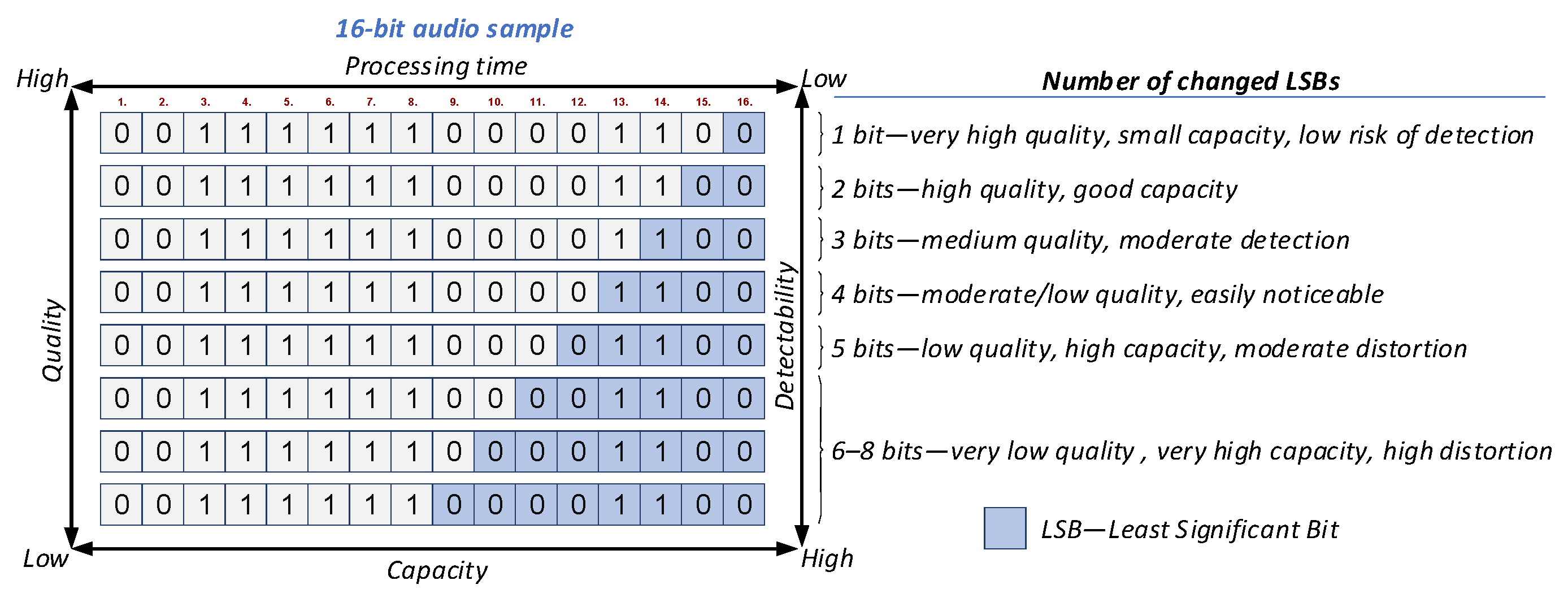

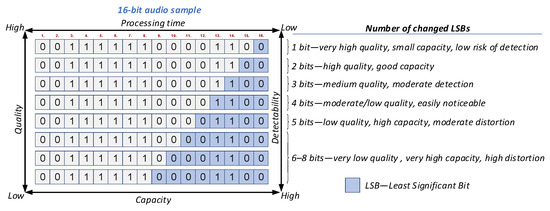

Increasing the number of modified LSBs expands the available embedding capacity but also increases perceptual distortion, processing time, and detectability of the hidden message, a well-known trade-off in audio steganography research [53]. In practice, the number of modified LSBs depends on the selected output quality: high-quality output modifies only a small fraction of LSBs, preserving audio fidelity, whereas low-quality output modifies a larger number of LSBs, increasing the available embedding capacity at the cost of greater distortion (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of changing a larger number of LSBs on stegano-processed audio.

In general, the embedding procedure can be mathematically described as follows:

where is the stegano. processed audio sample, is the original audio sample, is the -th bit of a message, and is the number of the changing LSBs. Because the internal implementation of DeepSound is not publicly available and was not modified for this study, the embedding logic is described here using a generic LSB workflow and follows these steps:

- Conversion of the message into a binary sequence.

- Conversion of sound signal to uncompressed WAV format.

- Reading the audio samples and identifying the LSB positions to be modified.

- Replacing the selected least significant bits with the message bits according to the chosen output quality level.

- Constructing the stego-audio signal.

- Audio signal conversion from WAV to FLAC format.

3.2.2. Extraction Procedure

For extraction, the modified LSB positions are read and reconstructed back into the original binary message. This procedure can be mathematically described by Equation (2). During extraction, the stego-audio signal is processed sample by sample, and the least significant bits corresponding to the embedding positions are isolated to recover the embedded bit sequence. The extracted bits are then concatenated and decoded to reconstruct the original serialized payload. Since the extraction process relies solely on deterministic bit-level operations, it is computationally lightweight and does not require access to the original (cover) audio signal.

3.2.3. Embedding Capacity

The steganographic tool used in this study, DeepSound, automatically determines the embedding capacity of an audio file, which depends primarily on the sampling rate and the selected output-quality level [39]. A higher sampling rate increases the available capacity, while lower output quality also allows more data to be embedded. Conversely, high output quality reduces capacity because fewer LSB values are modified during embedding [49,50].

After selecting an audio file and the desired output quality, the application reports the available steganographic capacity. According to the developers, the tool uses approximately one-half of the WAV file size for embedding at low quality, one-quarter at medium quality, and one-eighth at high quality [51]. Table 1 summarizes the measured capacities across different sampling rates and output-quality settings.

Table 1.

Embedding capacity as a function of sampling rate and output quality.

To ensure precise utilization of the available embedding capacity, a Python script was developed to generate a text file containing exactly the number of random characters corresponding to the maximum capacity of each audio file. This procedure enabled all 1000 FLAC files, spanning sampling rates from 40 Hz to 40,000 Hz, to embed a payload whose size exactly matched their individual maximum steganographic capacity.

3.2.4. Memory Footprint of the Stego-Processed Audio File

The memory footprint of a steganographically processed audio file is not a simple sum of the original audio size and the size of the embedded payload. Instead, the resulting file is significantly larger due to the interaction between LSB modifications and subsequent FLAC recompression. Table 2 illustrates this effect using an example FLAC file generated at a 40,000 Hz sampling rate (original size: 6380 B), showing its final size after partial and full utilization of the available steganographic capacity across three output-quality levels.

Table 2.

Stego-audio file size as a function of output quality and percentage of used embedding capacity.

The results clearly indicate that higher output quality results in a smaller stego-audio file, since fewer LSBs are modified and the signal retains higher compressibility. Conversely, lower output quality increases the number of altered samples, reduces compression efficiency, and leads to a substantially larger final file size.

3.2.5. Supported Formats for Embedding and Extraction

The steganographic application used in this study supports multiple audio formats for both embedding and extraction. In the experiments, FLAC was selected as the primary format because it provides lossless compression while maintaining full compatibility with the LSB embedding procedure. Before embedding, a FLAC file is internally decoded to an uncompressed WAV representation, the steganographic integration is performed on the PCM samples, and the resulting stego-audio is then re-encoded back into FLAC.

In addition to WAV and FLAC, the tool also supports WMA, MP3, and APE formats, allowing flexibility in selecting the desired audio carrier. Importantly, the application supports embedding of arbitrary file types, not only text-based messages but also images, audio, video, executables, and other binary data, thereby enabling broad applicability in scenarios where heterogeneous metadata must be securely integrated into an audio signal.

3.2.6. Security

The DeepSound application employs AES-256 encryption [48] to protect the embedded steganographic payload, providing a widely accepted and highly secure standard for safeguarding sensitive data. In this study, the effect of password length on the memory footprint of the stego-processed files was also examined (see Section 4.5). The results show that password length has no measurable impact on the final file size, indicating that encryption overhead does not influence the storage characteristics of the generated stego-audio files.

3.2.7. Speed of Steganographic Embedding and Extraction

Steganographic embedding and extraction were performed on one-second audio files containing between 11 and 59,897 bytes of embedded data. Both procedures demonstrated consistently high processing speeds. To evaluate performance more systematically, several sets of audio files were generated according to the specifications shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Execution time of steganographic embedding and extraction.

A low output-quality setting was used to maximize the amount of embedded data, enabling evaluation of performance under high-capacity conditions. The results show that both embedding and extraction procedures are computationally efficient: extraction time remained approximately constant (~1 s), while embedding time increased moderately with file size. It should be noted that overall performance was influenced by the high throughput of the NVMe SSD used in the experiments (sequential read speed 1224.46 MB/s and write speed 1001.26 MB/s), which significantly reduces I/O latency during file processing.

3.2.8. Robustness

Although the selected LSB-based algorithm proved practical and straightforward to implement, its robustness is extremely limited. In the robustness test, a high-quality stego-audio file containing the maximum embedding capacity was used as the reference sample. Multiple copies of this file were then generated, each modified by adding a very short silent segment either at the beginning or at the end of the audio signal (ranging from 1/10 to 1/10,000 of a second). In all tested cases, the embedded data became inaccessible, demonstrating that even minimal alterations to the audio content destroy the steganographic payload.

While this represents a clear weakness in terms of robustness, such sensitivity can also serve as an inherent tamper-detection mechanism, as any modification of the audio signal results in immediate data loss. The algorithm itself is comparatively easy to detect when more than two LSBs are altered, for example, through statistical analyses such as correlation coefficients or chi-square tests, which further confirms its low level of concealment.

3.3. Data Memory Usage with Respect to Binary or Text Format

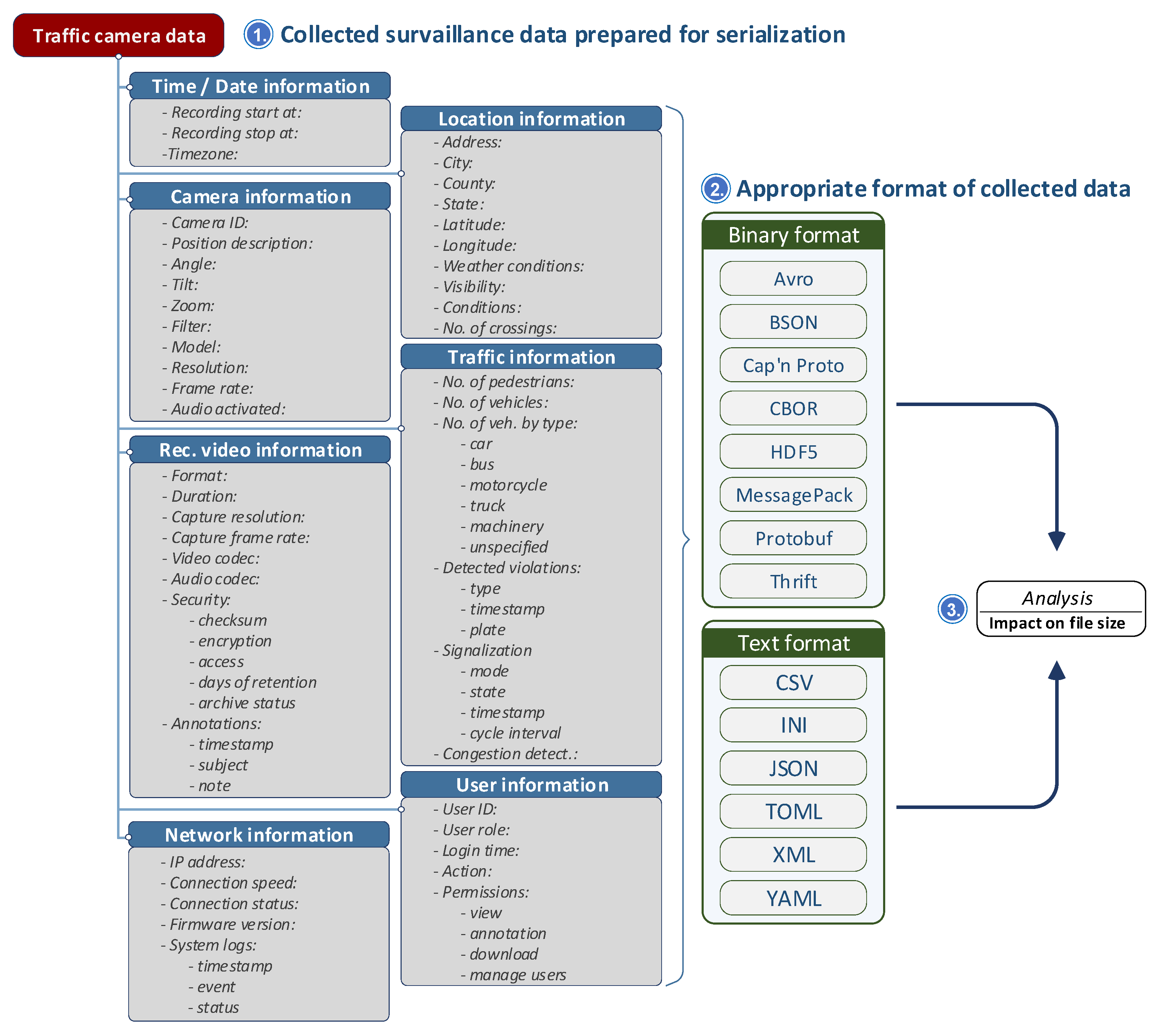

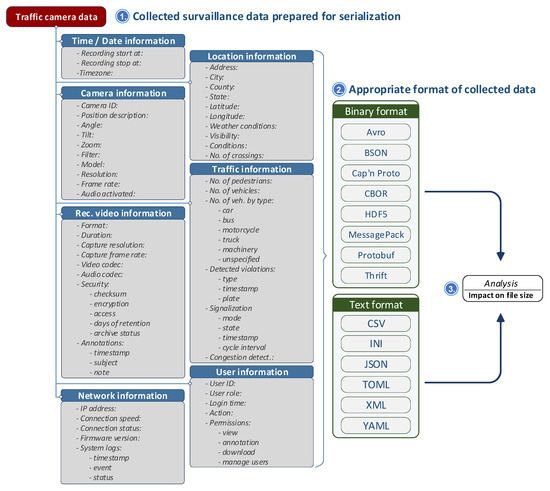

The data collected by an IoT surveillance system is crucial for monitoring and analyzing road conditions. To make this data more manageable and accessible, it is often divided into several categories, such as location, date/time, camera, recorded video, network, traffic, and user information. Figure 5 depicts the process that we implemented to determine the file sizes of specific file types carrying the surveillance data.

Figure 5.

The surveillance data and possible file formats.

This structured approach allows for easy retrieval and analysis of the data, ensuring that each data point is properly categorized for future reference or action. The information can be stored in either text or binary files, depending on the requirements of the system and the nature of the data. Text files are human-readable, which makes them easy to inspect and debug. Different text file formats are used today such as: CSV (Comma-Separated Values) [54], INI (Initialization File) [55], JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) [56], TOML (Tom’s Obvious, Minimal Language) [57], XML (eXtensible Markup Language) [58] and YAML (YAML Ain’t Markup Language) [59]. Binary files are more compact and efficient in terms of storage and processing speed. These include: Avro [60], BSON (Binary JSON) [61], Cap’n Proto [62], CBOR (Concise Binary Object Representation) [63], HDF5 (Hierarchical Data Format version 5) [64], MessagePack [65], Protobuf (Protocol Buffers) [66], and Thrift [67].

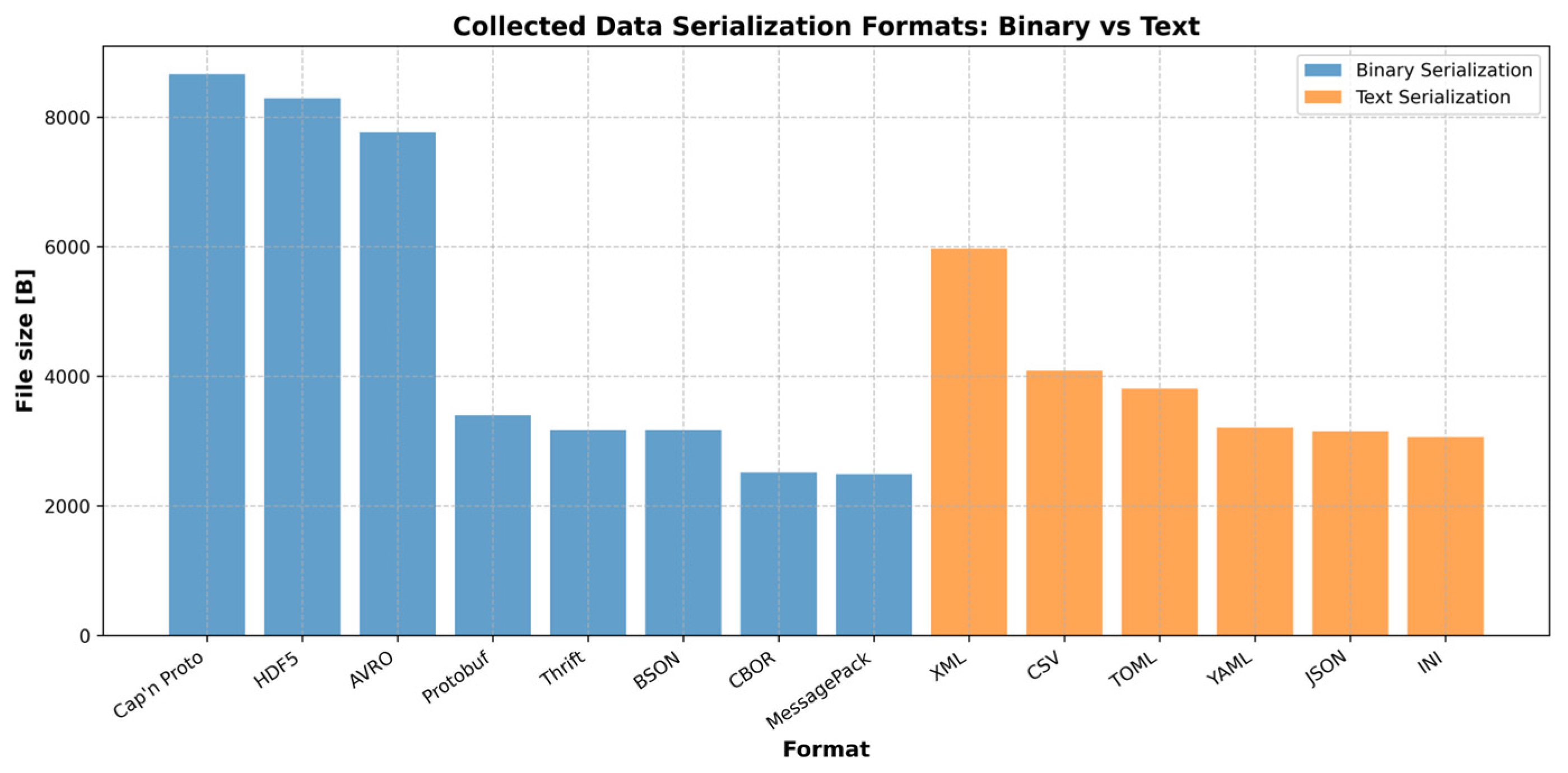

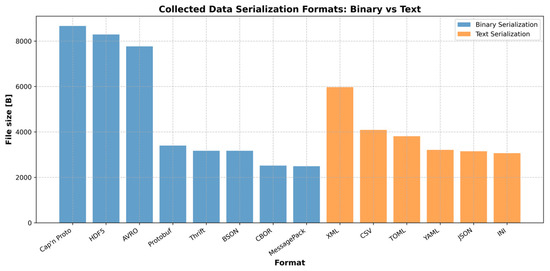

When it comes to selecting the best format for the smallest file size, binary formats generally outperform text formats due to their more efficient encoding. Figure 6 illustrates the memory usage in bytes for each text and binary data format listed. Among the binary formats, MessagePack, CBOR, and Avro are particularly known for their compactness and performance in terms of file size. For textual data, JSON is relatively compact, but CSV is often the smallest in terms of file size for simple tabular data. However, the exact file size will depend on the specific data being stored and the level of compression applied. In general, binary formats are preferred for systems that prioritize efficiency and space, while text formats are chosen when human readability or compatibility with existing systems is more important.

Figure 6.

The file size of the binary and text file formats.

This study explores the process of managing and optimizing traffic surveillance data collected from various IoT devices. Initially, a Python dictionary was created to organize and store key traffic-related information, including location, timestamp, camera data, network status, and traffic flow. The collected data is then converted into several commonly used text and binary formats. This conversion process aims to assess the efficiency and practicality of each format in terms of both human readability and storage requirements. A comparison of the file sizes resulting from each format is performed to analyze the trade-offs between text-based and binary serialization methods.

To determine the resulting file sizes, we emulated traffic camera data, examining both binary and text-based serialization formats for size and efficiency. We then use a procedure of serializing and evaluating these formats for their impact on the final FLAC-compressed audio file sizes after steganographic embedding.

The emulated data includes information from traffic cameras, encompassing time and date (timestamp of recorded data), camera (identifier and specifications), recorded video (metadata such as duration and resolution), network (bandwidth usage and other network-related details), location (geographic coordinates of the camera), traffic (traffic volume and conditions), and user information (interactions or operator input). As shown in Figure 5, we analyzed commonly used binary and textual data formats. The collected data is serialized into each format, and the resulting files are analyzed for size efficiency. The file sizes of the binary and text formats are then compared to assess their suitability for steganographic embedding in audio files. Additionally, the effect of choosing a specific serialization format on the overall size of the FLAC-compressed audio file with embedded data is evaluated.

Based on the analysis, the results and observations reveal that binary serialization formats demonstrate efficiency, producing smaller file sizes due to their compact representation. In terms of performance, Protobuf and MessagePack achieve the smallest file sizes, making them particularly suitable for steganographic embedding. Cap’n Proto, HDF5, and BSON produce slightly larger files because of additional metadata overhead, though they remain smaller than text-based formats. Overall, binary formats are highly suitable for embedding, as their compactness minimizes the impact on the audio file size.

Text Serialization Formats produce significantly larger files because of their human-readable encoding and verbosity. XML yields the largest file sizes, largely due to verbose syntax and extensive metadata. CSV results in moderate file sizes but lacks hierarchical structure support, while JSON and INI yield relatively smaller text-file sizes, offering a balance of readability and compactness. However, these larger text-based formats are less suitable for embedding, since their size can substantially increase the overall audio file size after steganographic integration.

4. Results

This section presents the empirical results obtained through a series of controlled experiments designed to evaluate how different audio and steganographic parameters influence both file size and perceptual audio quality. The findings are organized into thematic subsections, each addressing a specific factor, ranging from waveform type and noise color to embedding capacity and password characteristics, to provide a comprehensive understanding of their individual and combined effects.

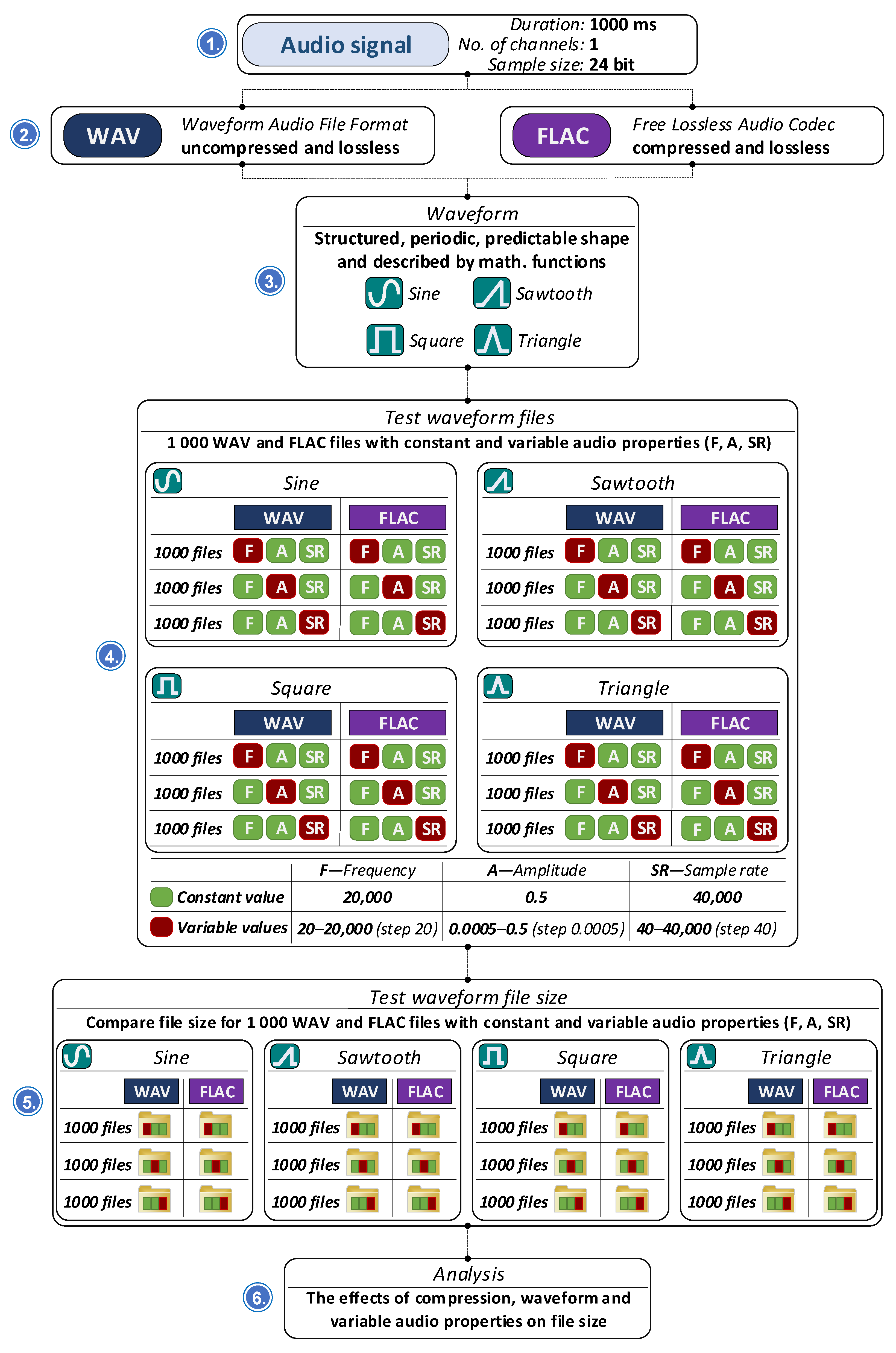

4.1. Effect of Sound Waveform on Audio File Size

We investigated whether the type of waveform [68] affects the size of audio files in WAV and FLAC formats according to the procedure described in Figure 7. To achieve this, 1000 audio signal files are generated using four fundamental waveform types: sine, sawtooth, square, and triangle. Key audio parameters, including frequency, amplitude, and sampling rate, are systematically varied to analyze their impact on file size. The generated files are examined to determine how these parameters and waveform types influence storage requirements in the uncompressed WAV format and the compressed FLAC format.

Figure 7.

Waveform signal analysis process.

Synthetic audio signals were selected because they can be generated easily and reproducibly under fully controlled conditions. Their mathematical structure is precisely defined, without unpredictable variations or complex spectral components. This makes them particularly suitable for analyzing the behavior of steganographic algorithms, as it allows systematic evaluation of how specific audio parameters (i.e., waveform type or noise profile, frequency, amplitude, sampling rate, duration, bit depth, and file size) affect the embedding process and the resulting stego-audio characteristics.

The use of synthetic signals also simplifies the measurement of steganographic impact on audio quality, waveform distortion, and memory footprint, since any deviations introduced by the embedding procedure are easier to isolate and quantify. Moreover, monotonic waveforms (e.g., pure tones) often sound artificial and uncomfortable to human listeners, reducing the likelihood that minor distortions would draw perceptual attention. In contrast, real audio recordings exhibit far more complex structures, including transients, background noise, silence segments, and dynamic spectral variations. For such content, a steganographic algorithm must preserve the original perceptual properties of the signal to remain imperceptible, which directly constrains the available embedding capacity.

This approach does, however, come with inherent limitations. The low concealment level of synthetic waveforms makes any modification easier to detect, as their spectral patterns are highly regular. Additionally, even minimal changes to the waveform can destroy the embedded data. Nevertheless, as noted earlier, this sensitivity can also be interpreted as an advantage: any deviation from the expected signal may serve as a reliable indicator of manipulation, giving the steganographic layer an auxiliary role in integrity verification.

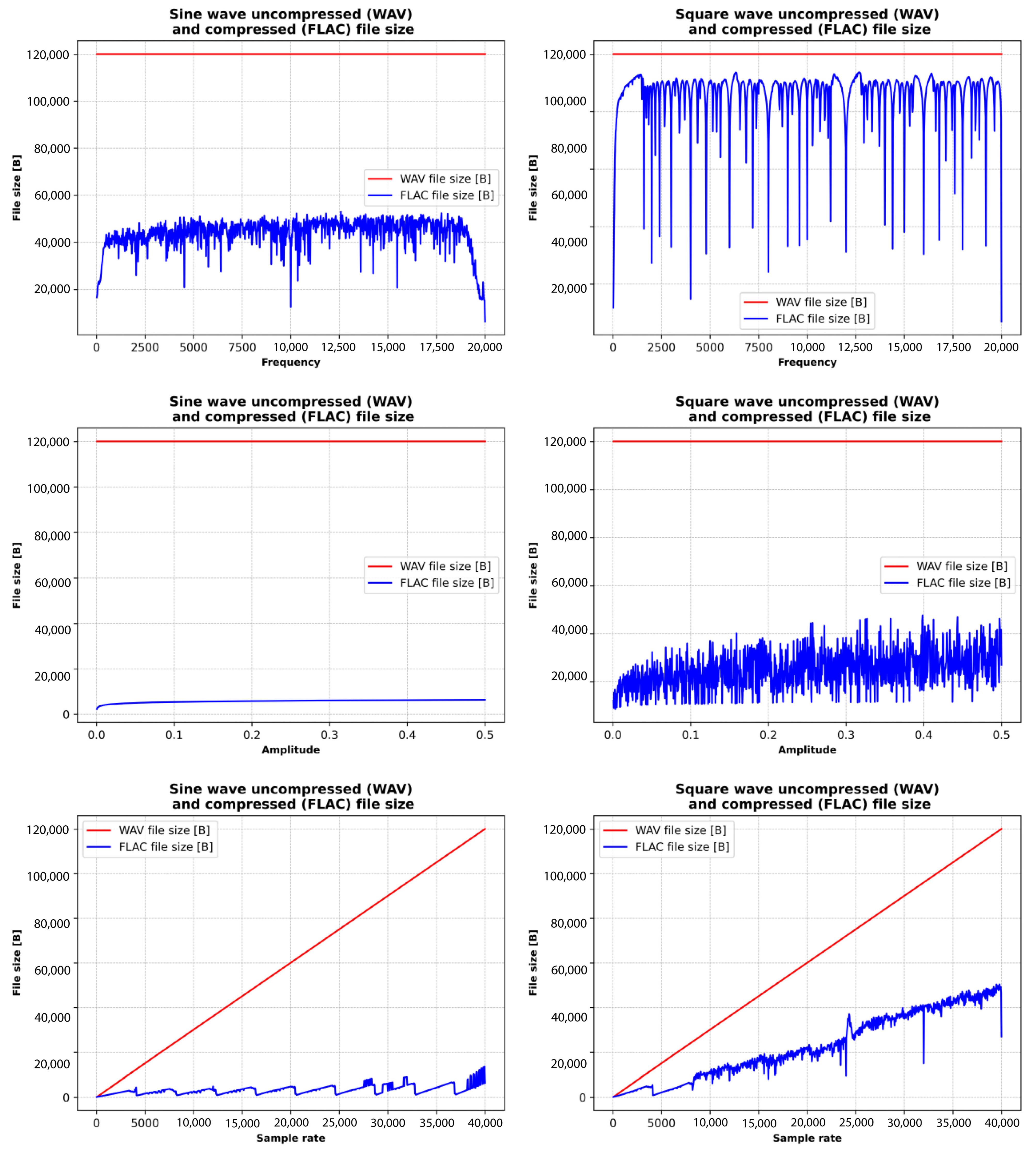

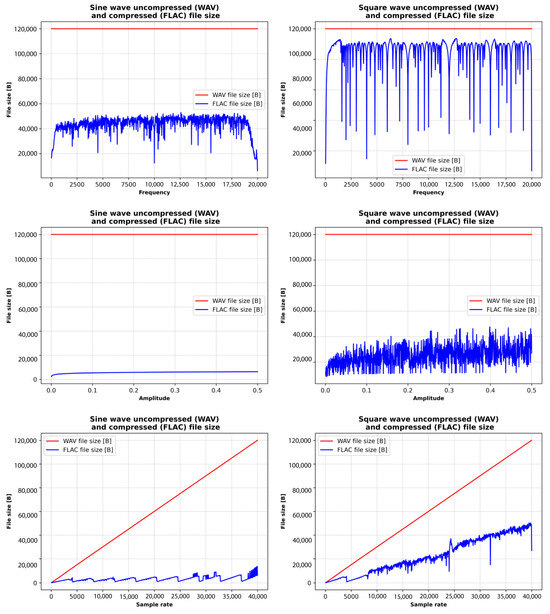

The results shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9 provide insights into the relationship between waveform properties, audio parameters, and file size, offering valuable information for applications requiring efficient audio storage and transmission without compromising quality. This analysis highlights the importance of selecting optimal audio configurations based on specific needs and file size constraints.

Figure 8.

File size considering the constant and variable properties of the sine and square waveform signal.

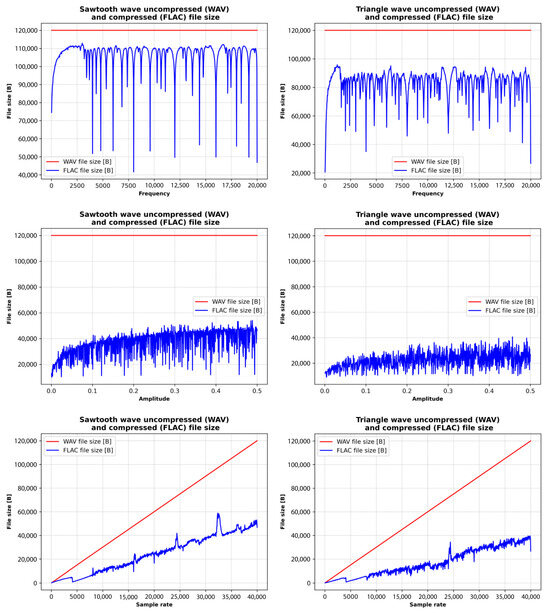

Figure 9.

File size considering the constant and variable properties of the sawtooth and triangle waveform signal.

The methodology of testing the influence of the waveform of audio recordings in WAV and FLAC format on the size of the audio file is described as follows: the audio signals used in the experiment have a duration of 1000 milliseconds (1 s), are recorded in a single channel (mono), and use a 24-bit sample size to ensure high-resolution audio quality. The waveforms generated include sine, square, sawtooth, and triangle types. Frequencies range from 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz, amplitudes range from 0.005 to 0.5, and sample rates span from 40 Hz to 40,000 Hz. For each waveform type, 1000 files are generated in both uncompressed WAV and compressed FLAC formats. These files are categorized based on the variation of one parameter within its defined interval, while the other two parameters remain constant. Some files maintain fixed frequency, amplitude, and sample rate, while others exhibit dynamic variation in these properties within the specified ranges. The analysis focuses on comparing file sizes across different waveform types and observing the effects of compression. We also examine how changes in audio signal properties such as frequency, amplitude, and sample rate affect the overall file size.

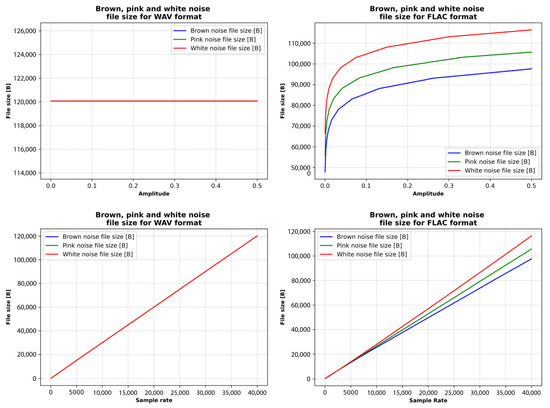

The results reveal that waveform type significantly affects file size due to the unique spectral characteristics of each waveform. Periodic waveforms like sine waves tend to produce smaller FLAC files because of their simplicity, whereas more complex waveforms, such as square and sawtooth, generate larger files. FLAC compression proves effective in reducing file sizes when compared to WAV, with greater efficiency observed in simpler waveforms and signals with constant properties. Regarding the influence of audio signal parameters, higher frequencies lead to larger file sizes due to increased spectral content. Amplitude variations have a less pronounced effect but do contribute to waveform complexity. Sample rate has the most substantial impact, with higher rates resulting in larger files in both WAV and FLAC formats. FLAC compression significantly reduces file size compared to WAV, with the compression ratio influenced by waveform complexity, and it is more efficient for simpler waveforms and constant audio properties.

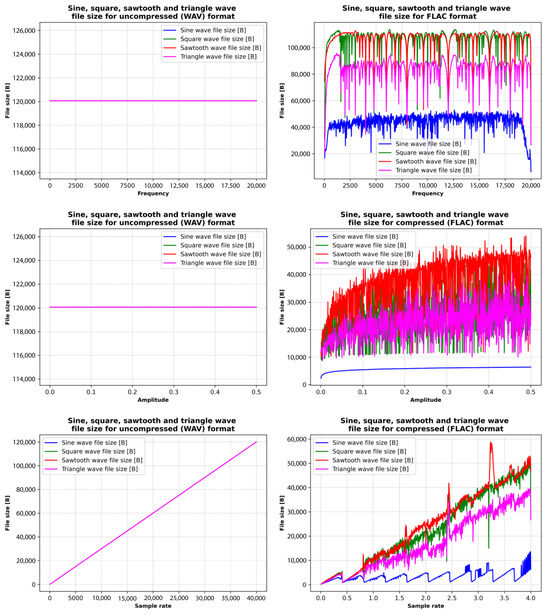

Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 illustrate the relationships between the sizes of WAV (uncompressed) and FLAC (compressed) files of sine, square, sawtooth, and triangle waves and their frequency, amplitude, and sampling rate. WAV file size remains constant at all frequencies and amplitudes, while file size grows linearly with sample rate. WAV is an uncompressed format, so its file size depends only on the sampling rate and bit depth, not the frequency or amplitude of the signal.

Figure 10.

Waveform file size considering the constant and variable properties of the WAV and FLAC file formats.

The size of a FLAC sine waveform file varies with frequency and generally increases as frequency and compression efficiency decrease. The size of FLAC files with sawtooth and triangle waveforms varies moderately, while the size of FLAC files with square waveforms shows very erratic behavior. Furthermore, the FLAC file size of sine waves varies minimally with increasing amplitude, while the file size of square, sawtooth, and triangle waves’ compression efficiency varies with increasing amplitude.

Finally, the size of the sine waves of the FLAC file increases steadily with little fluctuation, and the compression efficiency remains high. The size of FLAC files with sawtooth and triangle waveforms varies moderately, while the size of FLAC files with square waves shows very erratic behavior (as was the case with the frequency change).

The comparative analysis (Figure 10) shows that increasing the frequency and amplitude has minimal effect on the sinusoidal FLAC file size, while increasing the sample rate has little effect on the compression rate. Changing the frequency, amplitude, and sampling rate has a significant effect on the FLAC file size of sawtooth and triangle waves, while the square signal has a very erratic characteristic. The reason is that the sine waves do not have harmonics, while square, sawtooth, and triangle waves are more complex signals with harmonics (and sharp transitions), which can have a significant influence on the FLAC compression process.

4.2. Effect of Noise Color on Audio File Size

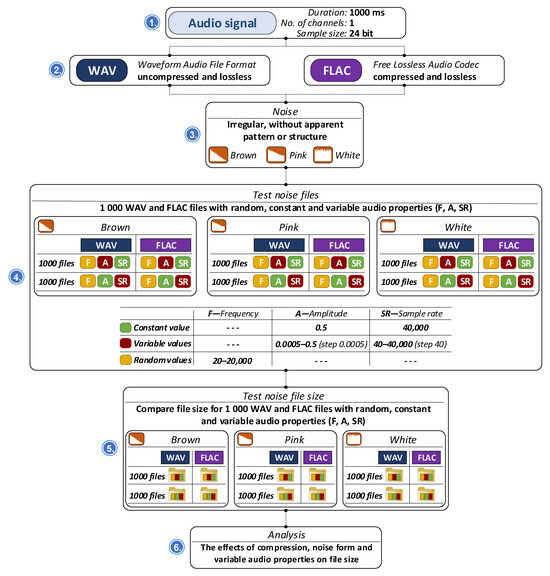

We also explored whether noise [69] affects the size of audio files in WAV and FLAC formats according to the procedure described in Figure 11. To conduct the analysis, 1000 audio signal files are generated using three types of noise signals characterized by their spectral properties: brown noise, pink noise, and white noise. These noise types differ in their frequency distribution, where the frequency is inherently random due to the nature of noise signals.

Figure 11.

Noise signal analysis process.

We systematically modified key audio parameters, such as amplitude and sampling rate, to assess their influence on file size. Given the random nature of noise, frequency remains uncontrolled, making amplitude and sampling rate the primary variables in the evaluation. The generated files are analyzed to determine the impact of noise type and audio parameters on the resulting file size in uncompressed WAV and compressed FLAC formats. Specifically, the audio signal used in the experiment has a duration of 1000 milliseconds (1 s), is single-channel (mono), and features a sample size of 24 bits per sample, ensuring high-resolution audio quality. It includes three types of noise: brown noise, pink noise, and white noise. Each signal randomly covers frequencies within the 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz range, with amplitude values ranging from 0.005 to 0.5 and sample rates ranging from 40 Hz to 40,000 Hz.

For each noise type, 1000 files are generated in both WAV and FLAC formats. These files are categorized based on their random frequency content and whether the amplitude and sample rate are constant or variable. In some cases, one parameter varies while the other remains fixed, and in others, both amplitude and sample rate vary within their respective ranges throughout the duration of the audio.

The analysis compares file sizes across different noise types and examines the impact of compression and varying audio properties. Specifically, it investigates how changing frequency, amplitude, and sample rate affect file size and evaluates the difference in size between WAV and FLAC formats.

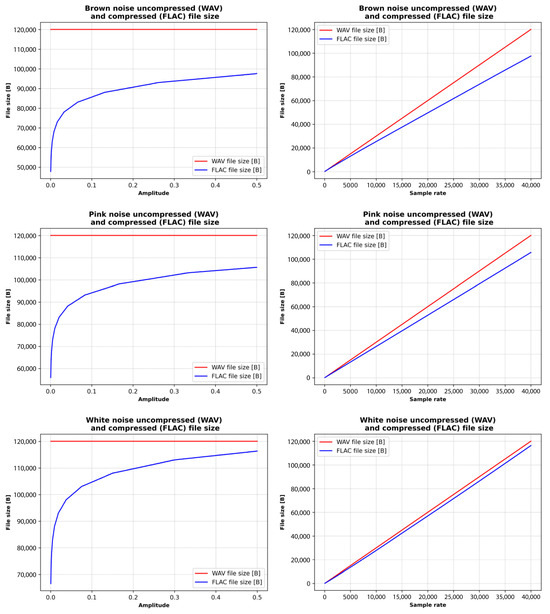

Figure 12 illustrates the relationships between the sizes of WAV (uncompressed) and FLAC (compressed) files of brown, pink, and white noise and their amplitude and sampling rate (frequencies are randomly selected in the range from 20 to 20,000 Hz). As seen from the results, the noise type significantly influences file size due to variations in spectral characteristics and randomness. White noise exhibits equal power across all frequencies, pink noise has greater power in the lower frequencies, and brown noise concentrates even more power in the lower end of the spectrum. These spectral properties impact how efficiently the files can be compressed.

Figure 12.

File size considering the constant and variable properties of the brown, pink, and white noise signal.

WAV file size remains constant at all amplitudes, while file size grows linearly with sample rate. WAV is an uncompressed format, so its file size depends only on the sampling rate and bit depth, not the frequency or amplitude of the signal. FLAC compression consistently reduces file size compared to WAV, with brown noise achieving the highest compression ratios due to its smoother spectral profile. Conversely, white noise tends to compress the least. Regarding audio signal properties, random frequency distributions cause variability in file sizes. Amplitude changes have a modest effect, with higher amplitudes slightly increasing file sizes. In contrast, sample rate has a significant impact: higher sample rates lead to substantially larger files in both WAV and FLAC formats.

Subplots in Figure 13 show that for brown, pink, and white noise types (where the FLAC file size is compared with amplitude), FLAC file size increases steeply at lower amplitudes, but the rate of increase slows as amplitude rises and exhibits a logarithmic trend. Brown noise exhibits a steep increase in file size, pink noise shows a moderate increase, while white noise experiences the steepest growth.

Figure 13.

Noise file size considering the constant and variable properties of the WAV and FLAC file formats.

The overall comparison shows that increasing the amplitude and sample rate affects the FLAC file size of brown, pink, and white noise. The FLAC file size is compared with the sample rate; the FLAC file size increases linearly. Brown noise demonstrates good compression efficiency, pink noise exhibits moderate compression efficiency, while white noise shows the weakest compression efficiency.

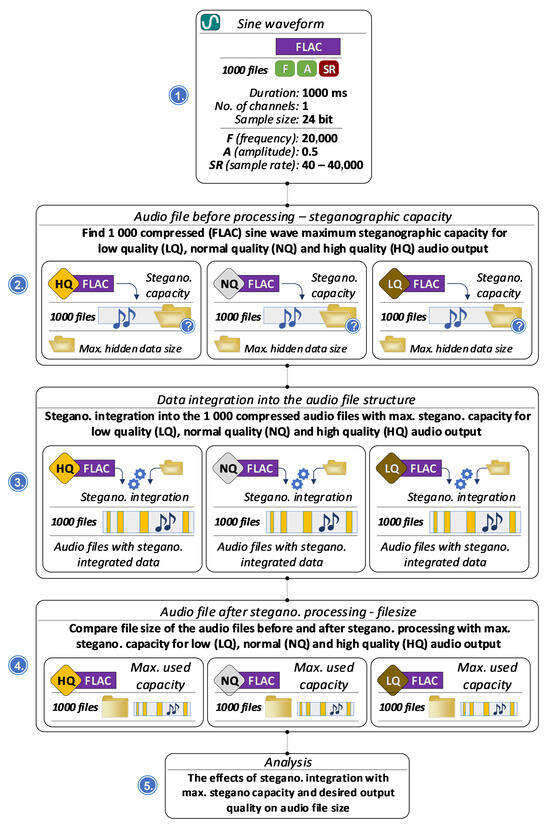

4.3. Effect of Full Embedding Capacity on File Size

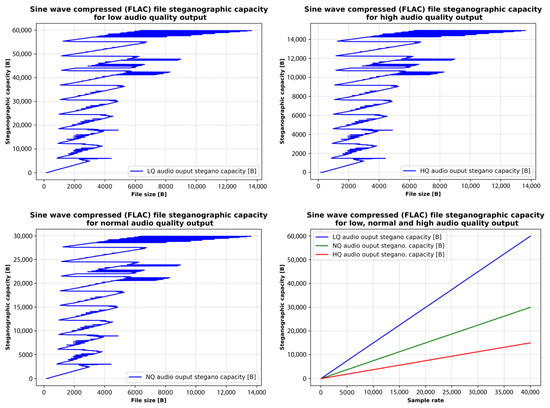

The impact of steganographic processing on the file size of 1000 FLAC sine wave audio files was evaluated according to the procedure described in Figure 14. The audio signals are generated with constant frequency and amplitude while the sampling rate is varied to explore its effect on storage requirements. Each audio file is processed using steganography, where the maximum steganographic capacity is utilized for embedding hidden data.

Figure 14.

File size analysis for the maximum used steganographic capacity.

The steganographically processed audio files are configured to produce outputs of low, normal, and high quality, reflecting different use cases and quality demands. File sizes are analyzed before and after steganographic processing to assess how the desired output quality and embedded data influence storage requirements.

Each signal has a duration of 1000 milliseconds (1 s), is single-channel (mono), and uses a 24-bit sample size. The frequency is fixed at 20,000 Hz, the amplitude is set at 0.5, and the sampling rate varies between 40 Hz and 40,000 Hz to assess its substantial influence on both file size and compression ratio.

In the steganographic embedding process, the audio files are filled to their maximum steganographic capacity, embedding as much hidden data as possible within the sine waveform. The output audio files are then categorized into three quality levels: low quality, normal quality, and high quality. All steganographic audio files are compressed using the FLAC format to analyze how embedding affects file size across the different quality levels.

The analysis focuses on the relationship between output quality and file size after steganographic processing, as well as how sampling rate and output quality together influence file size. Figure 15 illustrates that higher sampling rates, particularly those approaching 40,000 Hz, produce significantly larger files regardless of quality level, while lower sampling rates reduce file size but may also compromise the clarity and fidelity of the steganographic audio. Output quality also plays a critical role: low-quality files are the smallest due to minimal preservation of sound fidelity; normal-quality files represent a balance between sound fidelity and file size; and high-quality files are the largest, preserving the most audio detail while still embedding the maximum amount of hidden data.

Figure 15.

FLAC file size, considering the desired audio quality output and audio signal sample rate.

Finally, the addition of hidden data at maximum capacity affects FLAC compression efficiency. High-quality steganographic files, with richer audio content, are less compressible, resulting in larger file sizes even after compression. The analysis highlights a fundamental trade-off in audio steganography between steganographic capacity and audio quality, mediated by the sampling rate and resultant file size. Higher sampling rates in FLAC compressed sine files enhance the capacity for embedding hidden information due to larger file sizes, but come at the cost of increased storage requirements and potential quality degradation. Conversely, lower sampling rates conserve storage space and maintain higher audio fidelity but limit the extent of hidden data that can be securely embedded.

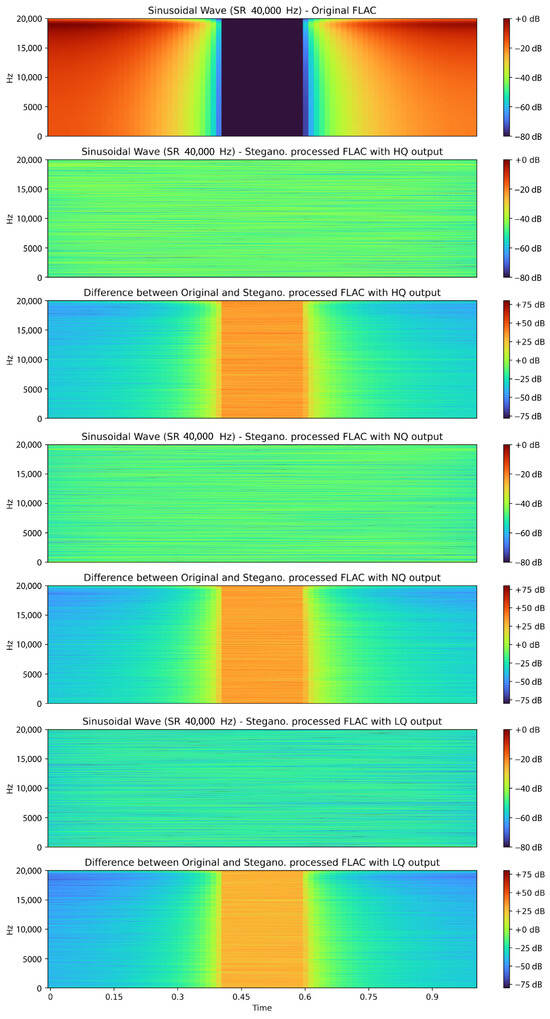

4.4. Audio Quality

To objectively evaluate the impact of steganographic embedding on the audio signal, both spectrograms (Figure 16) and statistical metrics (Table 4) were used to compare the original and stego-processed files across low-, medium-, and high-quality output settings.

Figure 16.

Spectrogram of original and steganographically processed FLAC audio files with various output qualities and 100% used stegano capacity.

Table 4.

MAE, MSE, SNR, and PSNR for different embedding capacities and output-quality levels.

The analysis includes a set of spectrograms (frequency-time representations) of the FLAC audio signal before embedding, followed by spectrograms of the stego-audio generated at each output-quality level, as well as corresponding difference spectra. The spectrogram of the original audio file exhibits a symmetric and stable frequency distribution, consistent with expectations for a synthetic or structurally defined signal. In contrast, the spectrograms of the stego-processed audio show clear deviations from the original waveform: characteristic frequency peaks disappear, spectral energy is redistributed, and the difference spectrograms reveal substantial decorrelation. These observations indicate that the embedding process significantly modifies the audio signal.

To quantify these modifications, several statistical and objective metrics commonly used in signal analysis were calculated, including Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), and Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) [70,71]. Table 4 presents these values for different levels of embedding capacity and output quality.

Lower MAE and MSE values, and higher SNR and PSNR values, reflect better preservation of the original signal. As shown in Table 4, increasing the proportion of used embedding capacity and lowering the output quality both result in higher distortion: MAE and MSE increase, while SNR and PSNR decrease. Conversely, embedding fewer data or selecting a higher output quality (i.e., modifying fewer LSBs) leads to smaller errors and higher SNR/PSNR values.

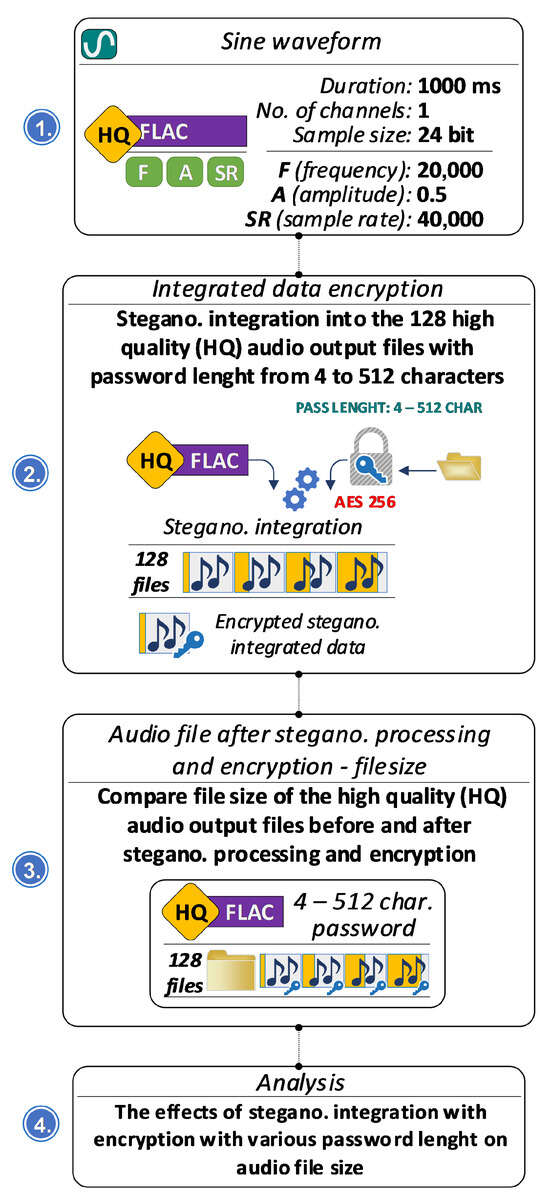

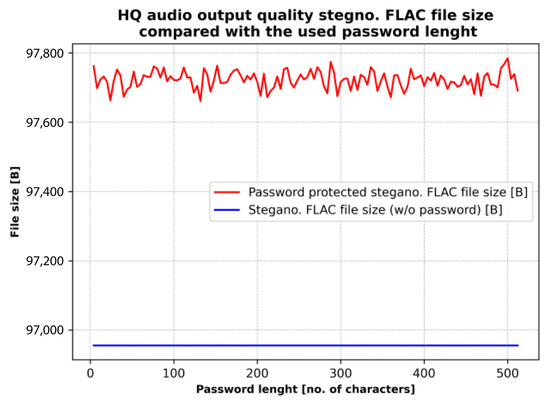

4.5. Effect of Password Length on File Size

Classical LSB embedding is not robust against steganalysis or signal manipulation. Its detectability is well documented, particularly when multiple LSBs are modified. For this reason, confidentiality of embedded data in our system is ensured through AES-256 encryption rather than through algorithmic robustness. While the presence of embedded data may be detectable, the encrypted payload remains protected, and any attempt to modify the stego-audio leads to destruction of the embedded content, providing an additional tamper-detection mechanism.

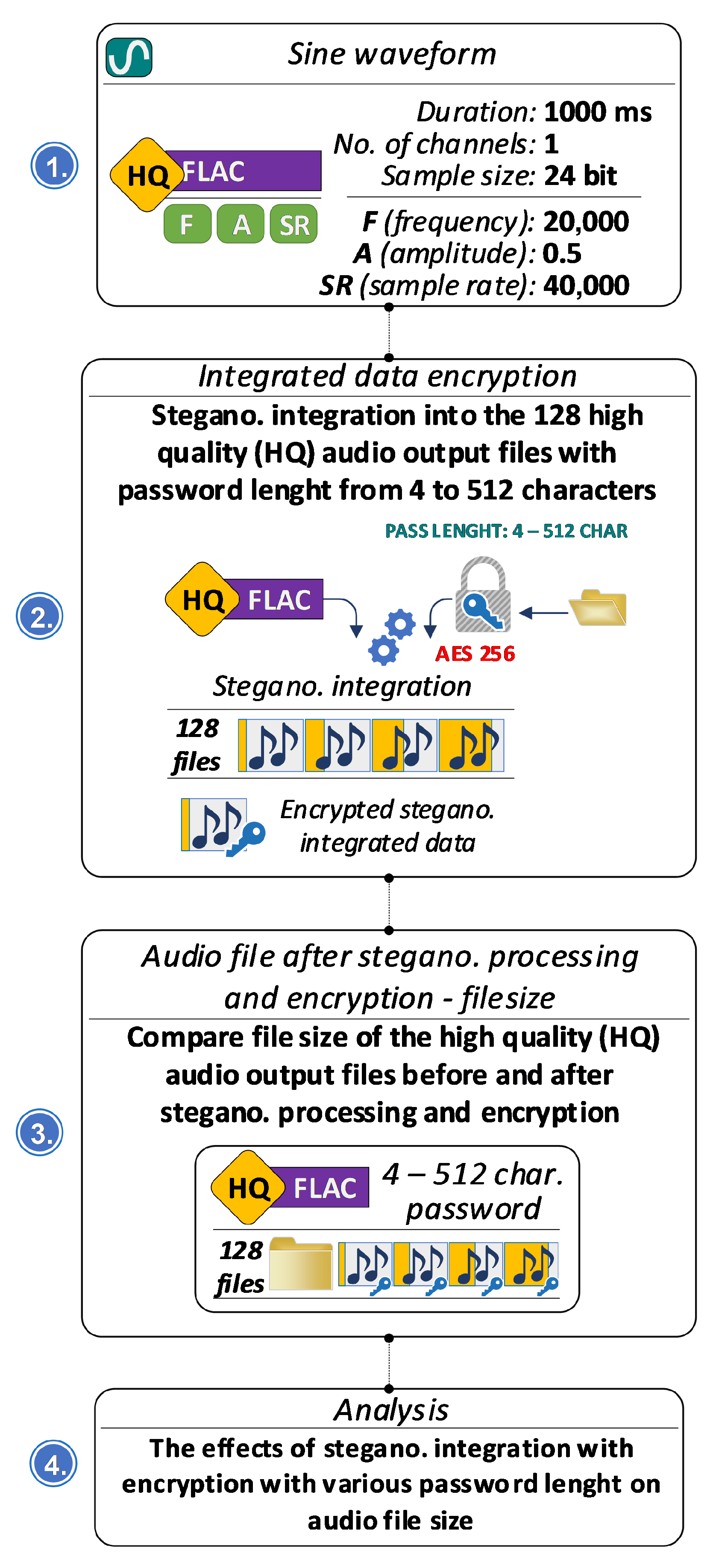

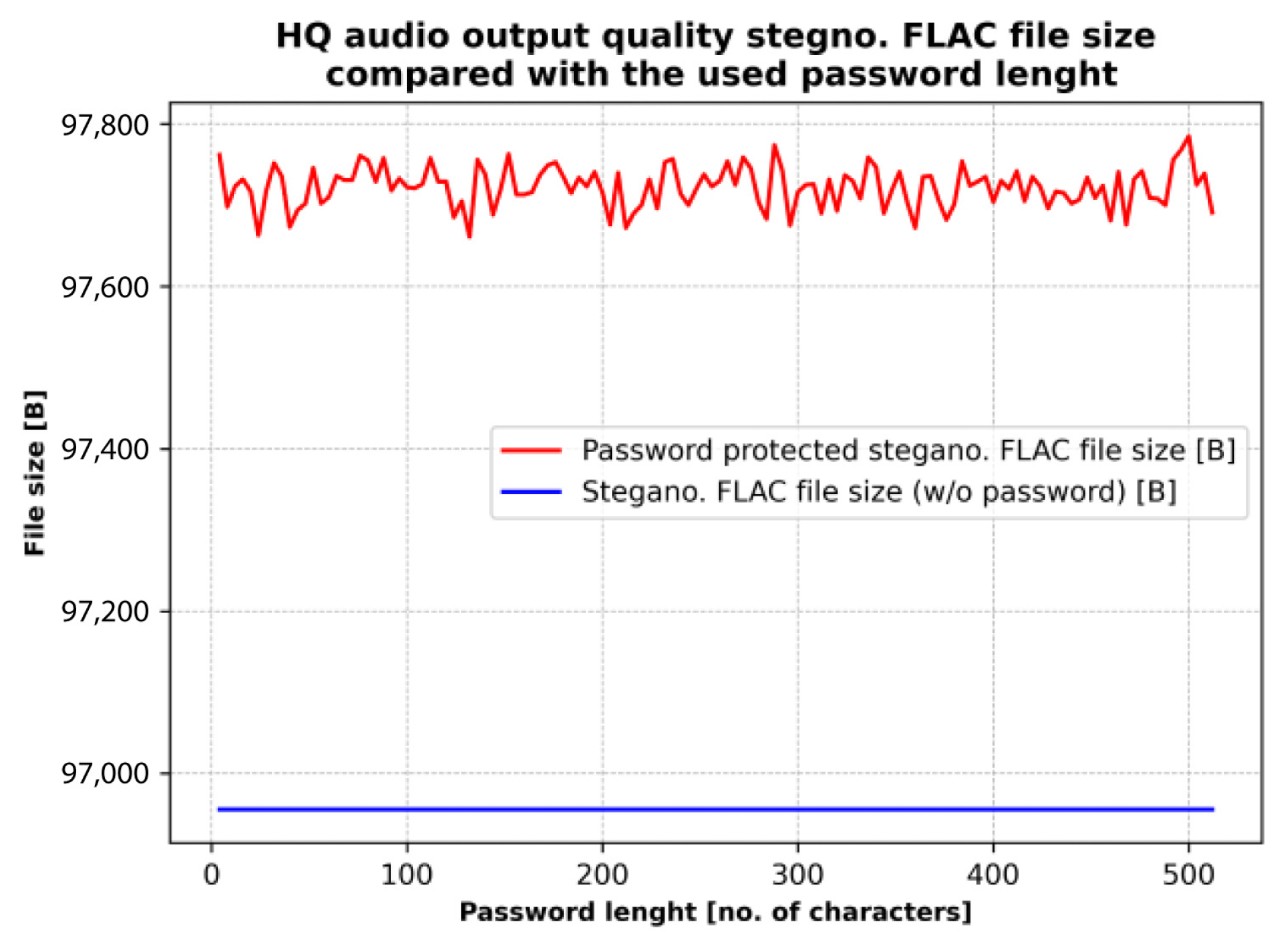

The workflow of the influence of password length analysis on the size of the stegano-processed audio file is presented in Figure 17, while Figure 18 illustrates the relationship between password length and file size. Although steganographic embedded data is not robust, its security can be significantly increased by using long passwords. A brute-force attack on a 256-character key is practically infeasible, and very long passwords also make password attacks ineffective due to the large number of possible combinations. Tests with passwords from 4 to 512 characters show that the length of the password has almost no effect on the size of the steganographically processed file: it increases by only about 700–800 bytes, while the security of the embedded data is significantly improved.

Figure 17.

Stegano-processed audio file size analysis for variable password length.

Figure 18.

Relationship between password length and stegano-processed audio file size.

5. Discussion

Based on the presented results, it can be concluded that the steganographic integration and extraction of road condition information does not alter the content of the data in any way. Furthermore, no significant degradation of the audio quality was observed in the compressed FLAC output when road condition information was steganographically embedded into the synthetic audio signal. The impact on audio file properties is smaller when the embedded data size is reduced, which indicates that binary data serialization formats are more suitable for steganographic integration.

The type of audio waveform has a direct influence on FLAC compression efficiency, and consequently on the final size of the steganographically processed audio file. In addition, a higher audio file sample rate results in a larger file size but also provides a higher steganographic capacity. Overall, the system enables the user to make trade-offs between audio quality, file size, and steganographic capacity without compromising the integrity or content of the embedded road condition information.

The proposed system offers several advantages that make it suitable for a traffic surveillance system. One of its key strengths is the preservation of the original surveillance video, which remains completely unchanged, thereby ensuring authenticity, credibility, and integrity. The embedded data is carried within a synthetically generated audio track and remains imperceptible to human hearing, thus maintaining the usability of the audio stream while securely storing additional information.

From a practical perspective, the proposed approach is feasible for deployment in traffic-monitoring systems. Embedding and extraction operations are complete in under 1–1.5 s and require minimal CPU resources, making them suitable for edge devices. The size of the stego-audio file depends on the selected output quality, which allows balancing storage and bandwidth constraints. Since only the audio stream is modified, existing video-processing pipelines remain unaffected. These characteristics indicate that the method can be integrated into real-time or near-real-time surveillance workflows. Furthermore, the system benefits from the modularity of IoT devices and the use of Over-the-Air (OTA) updates, which provide adaptability, scalability, and ease of integration into existing infrastructures.

We can also detect several limitations of our approach that need to be considered. Higher sampling rates and the use of complex waveforms significantly increase file sizes, which can lead to higher storage and bandwidth requirements. Moreover, the basic LSB steganography technique is vulnerable to detection and attacks, especially when compared to more advanced audio steganography methods that offer greater robustness and security. To improve protection, it is necessary to implement additional cryptographic mechanisms over the embedded data, ensuring higher resilience against unauthorized access or tampering. Another limitation is that regardless of the extent of modification of the steganographically processed audio track, the embedded data can be easily destroyed. While this poses a risk to data integrity, it can also serve as a valuable indicator of unintentional corruption or intentional manipulation of the audio file. In addition, users are faced with the challenge of carefully managing the trade-off between file size, audio quality, and embedding capacity to maintain system efficiency. Finally, potential legal restrictions on the use of hidden data transmission may emerge, raising regulatory challenges that could impact the system’s deployment and acceptance.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

This study demonstrated that integrating road-condition data into synthetic audio using LSB steganography can preserve the integrity of surveillance video while maintaining perceptual audio quality. The experiments highlight how audio-signal properties and serialization formats influence storage efficiency, embedding capacity, and compression behavior, providing practical guidelines for selecting suitable configurations in traffic-monitoring applications.

The findings empirically confirm H1, showing that embedding road-condition data via LSB steganography preserves the audio quality of compressed FLAC outputs, while binary serialization formats significantly reduce storage overhead compared to their text-based equivalents. The results further validate H2, demonstrating that waveform structure, sampling rate, and output-quality settings substantially affect compression efficiency and determine the steganographic trade-offs between file size, embedding capacity, and preserved signal fidelity. Despite these constraints, the method remains computationally lightweight and therefore suitable for deployment on edge devices or within real-time processing pipelines. The limited robustness of LSB, while a known weakness, also provides inherent tamper-detection properties and can be complemented with strong cryptographic protection of the embedded data.

Future work will include comparative evaluation against more advanced steganographic techniques, analysis using real surveillance audio, and the development of adaptive models that optimize parameter selection under varying operational conditions. Additional efforts will address regulatory and forensic considerations to support secure and verifiable integration of metadata within traffic-monitoring systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and I.G.; methodology, A.S. and I.G.; software, A.S.; validation, A.S., I.G., M.M. and M.P.; formal analysis, A.S. and I.G.; investigation, I.G.; resources, A.S. and I.G.; data curation, A.S. and I.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and I.G.; writing—review and editing, I.G., M.M. and M.P.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, I.G., M.M. and M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-funded and supported by the European Union through the NextGenerationEU programme under the project “EDGEWISE” (ID: 644-01/25-01/03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BSON | Binary JSON |

| CBOR | Concise Binary Object Representation |

| CSV | Comma-Separated Values |

| FLAC | Free Lossless Audio Codec |

| GANs | Generative Adversarial Networks |

| HDF5 | Hierarchical Data Format version 5 |

| INI | Initialization File |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LSB | Least Significant Bit |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| OTA | Over-the-Air |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| QIM | Quantization Index Modulation |

| RSA | Rivest–Shamir–Adleman |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| TOML | Tom’s Obvious, Minimal Language |

| VoIP | Voice over Internet Protocol |

| WAV | Waveform Audio File Format |

| WaveGAN | Wave Generative Adversarial Network |

| XML | eXtensible Markup Language |

| XOR | eXclusive OR |

| YAML | YAML Ain’t Markup Language |

References

- Fedorov, A.; Nikolskaia, K.; Ivanov, S.; Shepelev, V.; Minbaleev, A. Traffic Flow Estimation with Data from a Video Surveillance Camera. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, A.; Sarkar, S.; Maiti, J. A Real-Time Video Surveillance System for Traffic Pre-Events Detection. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 154, 106019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaadeed, N.; Asim, M.; Al-Maadeed, S.; Bouridane, A.; Beghdadi, A. Automatic Detection and Classification of Audio Events for Road Surveillance Applications. Sensors 2018, 18, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwoch, G.; Kotus, J. Acoustic Detector of Road Vehicles Based on Sound Intensity. Sensors 2021, 21, 7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarpasand, O.; Almojarkesh, A.; Morris, S.; Stephens, E.; Chalabi, A.; Almojarkesh, U.; Almojarkesh, Z.; Pope, F.D. Traffic Noise Assessment Using Intelligent Acoustic Sensors (Traffic Ear) and Vehicle Telematics Data. Sensors 2023, 23, 6964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniuk, K.; Kostek, B. Machine Learning Applied to Acoustic-Based Road Traffic Monitoring. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 207, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M.Y.; El-Hafeez, T.A.; Hassan, E. Acoustic Data Detection in Large-Scale Emergency Vehicle Sirens and Road Noise Dataset. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alías, F.; Alsina-Pagès, R.M. Review of Wireless Acoustic Sensor Networks for Environmental Noise Monitoring in Smart Cities. Hindawi J. Sens. 2019, 2019, 7634860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DCASE Challenge. Task 6: Acoustic-Based Traffic Monitoring. 2024. Available online: https://dcase.community/challenge2024/task-acoustic-based-traffic-monitoring (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Parineh, A.; Sarvi, M.; Asadi Bagloee, S. MELAUDIS: A Large-Scale Benchmark Acoustic Dataset for Intelligent Transportation Systems Research. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, W.; Gruhl, D.; Morimoto, N.; Lu, A. Techniques for data hiding. IBM Syst. J. 1996, 35, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruhl, D.; Lu, A.; Bender, W. Echo hiding. In Information Hiding; Anderson, R., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; Volume 1174. [Google Scholar]

- Delforouzi, A.; Pooyan, M. Adaptive Digital Audio Steganography Based on Integer Wavelet Transform. Circuits Syst. Signal Process 2008, 27, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wornell, G.W. Quantization index modulation: A class of provably good methods for digital watermarking and information embedding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2001, 47, 1423–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Jiang, S.; Huang, J. Heard More Than Heard: An Audio Steganography Method Based on GAN. aXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.04986. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, K.; Jia, X. A Coverless Audio Steganography Based on Generative Adversarial Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Research on the Mechanism and Key Technology of Audio Steganalysis. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Balgurgi, P.P.; Jagtap, S.K. Audio Steganography Used for Secure Data Transmission. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 699–706. [Google Scholar]

- Erfani, Y.; Siahpoush, S. Robust Audio Watermarking Using Improved TS Echo Hiding. Digit. Signal Process. 2009, 19, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, H.; Das, R.K.; Nandi, S.; Prasanna, S.M. An Overview of Digital Audio Steganography. IETE Tech. Rev. 2020, 37, 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, K.; Li, S. Audio Steganography with Less Modification to the Optimal Matching CNV-QIM path with the Minimal Hamming Distance Expected Value to a Secret. Multimed. Syst. 2021, 27, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahal, M.S.; Sen, A.A.; Basuhil, A.A. High Level Security Based Steganoraphy in Image and Audio Files. J. Theor. Applies Inf. Technol. 2016, 87, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sawant, S.; Shah, J.; Sankholkar, A.; Umredkar, Y.; Kashilkar, M.; Deshpande, K. Sound Secret Audio Crypt—LSB-Based Audio Steganography Using RSA. In Proceedings of Fifth Doctoral Symposium on Computational Intelligence: DoSCI 2024; Swaroop, A., Kansal, V., Fortino, G., Hassanien, A.E., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 1086. [Google Scholar]

- Abiew, N.A.K.; Jnr, M.D.; Brown-Acquaye, W. LSB-based Audio Steganographical Framework for Securing Data in Transit. Int. J. Res. Comput. Sci. 2021, 12, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hemanth, H.; Hrutish Ram, V.S.; Guru Raghavendran, S.; Subhashini, N. Modified LSB Algorithm Using XOR for Audio Steganography. In Sustainable Advanced Computing; Aurelia, S., Hiremath, S.S., Subramanian, K., Biswas, S.K., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2022; Volume 840, pp. 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khamy, S.E.; Korany, N.; El-Sherif, M.H. Robust Image Hiding in Audio Based on Integer Wavelet Transform and Chaotic Maps Hopping. In Proceedings of the 2017 34th National Radio Science Conference (NRSC), Alexandria, Egypt, 13–16 March 2017; pp. 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Dudhwal, H.; Boaddh, J.; Samar, J. A Review of an Extensive Survey on Audio Steganography Based on LSB Method. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Trends 2021, 7, 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Abduljaleel, I.Q.; Abduljabbar, Z.A.; Al Sibahee, M.A.; Ghrabat, M.J.J.; Ma, J.; Nyangaresi, V.O. A Lightweight Hybrid Scheme for Hiding Text Messages in Colour Images Using LSB, Lah Transform and Chaotic Techniques. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2022, 11, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAteer, I.; Ibrahim, A.; Zheng, G.; Yang, W.; Valli, C. Integration of Biometrics and Steganography: A Comprehensive Review. Technologies 2019, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, C. Steganography and Steganalysis in Voice over IP: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, A.A.; Hussain, M.; Wahab, A.W.A.; Idris, M.Y.I.; Abdullah, N.A.; Jung, K.-H. High-Capacity Image Steganography with Minimum Modified Bits Based on Data Mapping and LSB Substitution. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.K.; Javed, A.R.; Amesho, K.T.T.; Bhowmick, A.; Rahul, P.; Sannigrahi, M.; Shanmugathan, V.; Bandyopadhyay, S. A New Type of Audio Steganography with Increased Privacy Using Different Ratios of LSB Embedding. In Proceedings of the 6th Smart Cities Symposium (SCS 2022), Hybrid Conference, Sakhir, Bahrain, 6–8 December 2022; pp. 316–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinad, C.D.; Chiranjeevi, N.; Hegde, K.V.; Tripathi, S. Audio Steganography Using Multi LSB and IGS Techniques. In Security in Computing and Communications; Thampi, S.M., Wang, G., Rawat, D.B., Ko, R., Fan, C.I., Eds.; SSCC 2020 Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 1364. [Google Scholar]

- Yanuar, M.R.; MT, S.; Apriono, C.; Syawaludin, M.F. Image-to-Image Steganography with Josephus Permutation and Least Significant Bit (LSB) 3-3-2 Embedding. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binny, A.; Koilakuntla, M. Hiding Secret Information Using LSB Based Audio Steganography. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Soft Computing and Machine Intelligence, New Delhi, India, 26–27 September 2014; pp. 56–59. [Google Scholar]