1. Introduction

Date palm production is of considerable economic and ecological importance to the arid and semi-arid areas in which it operates, as well as local economies and food security [

1]. However, date palm crops can be susceptible to a range of diseases and pests—including Bayoud disease [

2], white scale [

3], or dubas bugs [

4]—that can severely reduce the crop yield and quality of fruit [

5]. Early and accurate detection of these threats is crucial to ensure the sustainability of productivity and to develop more resilient agricultural practices.

With recent advancements in deep learning, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), there has been considerable potential to automate the detection of plant disease using images and identify the type of disease once images are classified. CNNs, in particular, have shown great promise in performance in automatically capturing hierarchical features from complicated visual data, making them a useful tool for tasks including detection and diagnosis of plant diseases on leaves, fruit, or stems [

6,

7]. However, a limitation of using these models is that they operate as “black boxes”, which means there is reduced transparency in how they make decisions [

8]. Limitations with trust and deployment under real-world practice have been raised by practitioners of agriculture [

9].

To overcome these issues, attention mechanisms have been proposed as a particularly useful approach. While attention mechanisms were pioneered in natural language processing [

10], attention modules have made their way into computer vision specifically due to their ability to dynamically emphasize the most informative parts of an input image and consequently aid classification and interpretation [

11]. Within agriculture, attention has been shown to augment classification through its integration into CNNs in a variety of studies in order to better attend to patterns indicative of disease and reduce the influence of background and visual clutter [

12].

This study conducts the first systematic assessment of four widely used attention mechanisms—Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE), Efficient Channel Attention (ECA), Soft Attention, and the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM)—integrated into both a heavyweight backbone (ResNet50) and a lightweight architecture (MobileNetV2) specifically for date palm disease classification. While prior works have applied attention modules in agricultural vision tasks, they often focus on a single mechanism, a single backbone, or report accuracy without examining interpretability or cross-dataset robustness. Addressing this gap, our work provides a unified, controlled comparison that jointly evaluates predictive performance, explainability through attention-driven heatmaps, and generalization capabilities using external samples. By analyzing how distinct attention strategies influence both precision and model reasoning across architectures of different complexity, this study offers new insights into the design of reliable and interpretable AI for agricultural disease detection. Ultimately, it contributes a comprehensive benchmark and practical guidance for developing deployable, attention-enhanced models tailored to the needs of precision agriculture and the sustainable maintenance of date palm crops.

2. Related Work

Recent advancements in deep learning have allowed attention mechanisms to be incorporated into a convolutional neural network (CNN) to enhance plant disease and pest detection and classification. Two of the backbones covered in this study, ResNet50 [

13] and MobileNetV2 [

14], have been used in several studies to investigate attention-enhanced architectures.

The Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) mechanism has exhibited computation and predictive performance when integrated into both deep and lightweight models for various applications [

15]. In one study, a hybrid model (ResNet50 + ECA and DenseNet201) achieved a validation accuracy of 98.67% on a date palm disease dataset, thus showing considerable generalization performance [

16]. ECA has also been widely implemented in MobileNetV2 across multiple research studies. Specifically, an improved MobileNetV2 model leveraging ECA and Bottleneck_RepMLP with only 0.91 M parameters demonstrated 99.53% accuracy on the PlantVillage dataset, showcasing ECA performance in lightweight contexts [

17]. Another study applied ECA in a MobileNetV2–YOLOv3 pipeline for tomato gray mold detection, achieving an F1-score of 95.6% and enabling the model to identify small lesions [

18].

Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks have also been successfully integrated for channel-wise feature recalibration [

19]. Although not directly using ResNet50, SE modules were applied to a Faster R-CNN model based on ResNeXt-101 for detecting small agricultural pests, achieving a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 73.9% on the Pest24 dataset and outperforming other detectors designed for small objects, highlighting the importance of SE for localization tasks [

20]. Similarly, SE was integrated into a Mask R-CNN model for detecting anthracnose in apple fruits, producing an AP of 72.26 and exceeding baseline detectors YOLOv3 and RetinaNet, especially in challenging visual contexts such as overlap and complex patterns [

21]. SE has also been investigated in classification settings; for instance, a MobileNet-based model incorporating SE, enhanced Focal Loss, and two-stage transfer learning achieved 99.78% accuracy on PlantVillage and 99.33% on a real-world rice disease dataset, significantly outperforming other CNNs, including InceptionV3, VGG19, and MobileNetV2 [

22]. Additionally, a comparison of attention mechanisms, including SE, CBAM, and Shuffle Attention (SA), on several lightweight backbones, particularly MobileNetV2, showed that SE improved accuracy in most configurations [

12].

The Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) has also been incorporated into CNNs for plant disease detection with notable results [

23]. For instance, integrating CBAM into ResNet50 allowed classification of maize leaf diseases with 97.89% accuracy and improved robustness under noisy field conditions [

24]. In another study, CBAM was evaluated with multiple backbones, including MobileNet, to detect plant diseases in potato leaves, achieving 96.09% accuracy and a 96.99% F1-score with the MobileNet-CBAM combination [

25]. However, the performance of CBAM was reported to depend on the backbone, providing improvements in certain architectures but more limited benefits in others [

12].

Soft Attention mechanisms have also been investigated for their ability to enhance feature representation [

26]. A lightweight CNN incorporating Soft Attention was developed for the classification of tomato leaf disease, achieving 99.04% accuracy and demonstrating robustness to Gaussian noise, indicating that Soft Attention is effective in directing the network to discriminative areas in shallow architectures.

Apart from quantitative performance improvements, empirical studies have emphasized the importance of explainability in attention-based models. Grad-CAM was used to visualize regions that were important for model predictions, providing evidence that attention mechanisms help the network focus on semantically relevant areas. This, in turn, enhances trustworthiness and interpretability—two aspects that are particularly important in agricultural diagnostic applications [

12,

24,

26].

Overall, these studies elucidate that the attention mechanisms (SE, ECA, Soft Attention, and CBAM) when combined with CNN backbones (ResNet50 and MobileNetV2), illustrate enhanced feature representation, improved robustness to noise and the detection of small lesions, increased interpretability and efficiency on devices with limited resources. These features are all very useful for application in real-world agricultural usage scenarios, such as in-field detection of diseases and pests in crops such as date palms.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

The dataset implemented in this study is Palm Leaves [

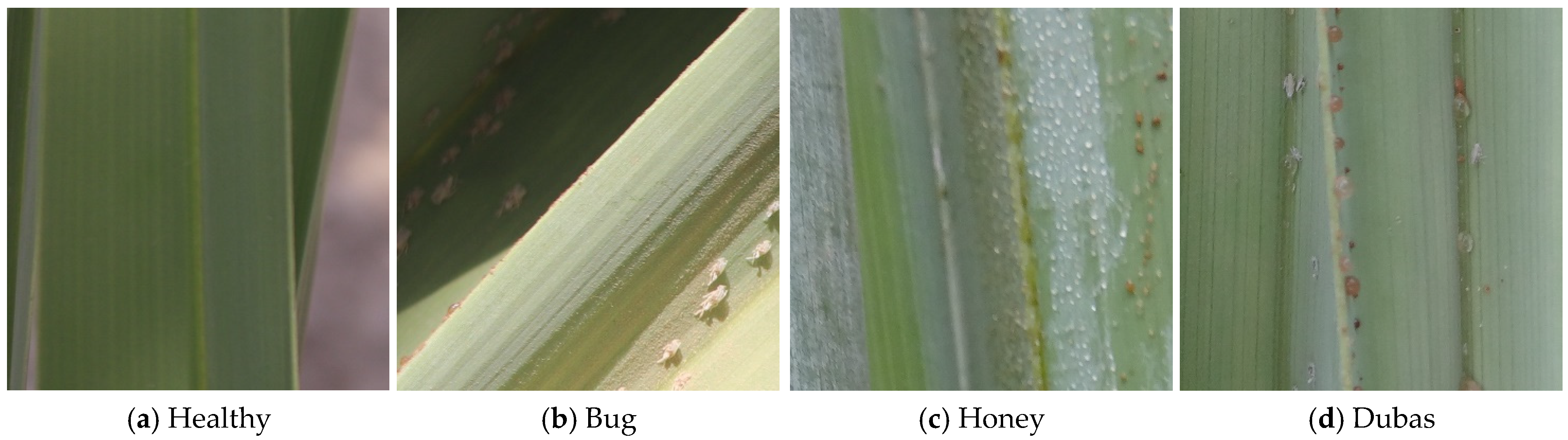

27], a collection of high-resolution images designed specifically for the classification of diseased date palm leaves. These images were sourced as part of drone-based imaging in a controlled setting in District Aoun Karbala, Iraq. The original images are 896 × 896 pixels and contain four classes:

Healthy: normal, disease-free leaves;

Bug: leaves infected by insects only;

Honey: leaves affected by honeydew secretion;

Dubas: leaves simultaneously infected by insects and honeydew.

The initial dataset consists of 3000 images, with 800 images for each class, except for the minority class Bug, with only 600 images.

Figure 1 shows representative original samples from each class of the Palm Leaves dataset, while

Table 1 presents the initial class distribution of the three subsets: train, validation, and test subsets, prior to any balancing or augmentations. The split was performed before applying any augmentation, ensuring that augmented versions of the same image were never distributed across different subsets.

To tackle the imbalance in the dataset, a data balancing approach was taken to guarantee equal representation among all subsets. Subsequently, all images underwent a resizing process to standard dimensions of 224 × 224 pixels and were normalized according to the ImageNet mean and standard deviation. In order to increase generalization and reduce overfitting, we performed data augmentation on the training set, which included random rotations, variations in zoom, and random horizontal or vertical flipping. These transformations enriched the training distribution by generating new plausible image variations while preserving disease characteristics. All augmented samples were strictly confined to the training set, while the validation and test sets remained composed exclusively of original, non-augmented images to avoid any form of data leakage. The final distribution of images across training, validation, and test sets is presented in

Table 2, following the data balancing and augmentation process.

3.2. Attention Mechanisms

Attention mechanisms in deep learning aim to selectively enhance relevant features while suppressing less informative ones, thereby improving the representational power of convolutional neural networks. In the context of computer vision, channel attention mechanisms specifically focus on modeling inter-channel dependencies to determine what to attend to across feature maps. Inspired by the human visual system, several mechanisms have been proposed to capture global or local channel-wise information and reweigh features accordingly [

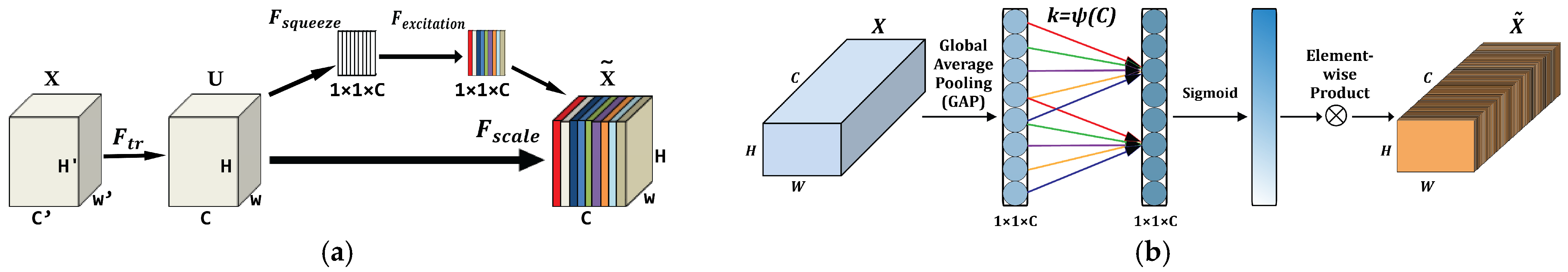

11]. In this section, we review and compare four representative channel-related attention mechanisms: the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block, the Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module, the Soft Attention (CAM-based variant), and the full CBAM framework, which sequentially integrates channel and spatial attention.

3.2.1. Squeeze-And-Excitation (SE)

The Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) is a foundational channel attention mechanism that improves a network’s representational capacity by adaptively recalibrating channel-wise feature responses [

19]. Its central idea is to model the interdependencies between channels explicitly, allowing the network to emphasize informative features and suppress less relevant ones. The module proceeds in two steps. First, the squeeze phase gathers spatial data using global average pooling (GAP). This creates a channel descriptor vector that sums up the distribution of responses across spatial locations. Second, in the excitation phase, the descriptor goes through a gating mechanism. This mechanism comprises two fully connected layers with a bottleneck design, followed by ReLU and sigmoid activations. The resulting attention vector acts as a set of channel-wise weights used to rescale the original input feature map via element-wise multiplication.

Mathematically, given an input tensor

, the attention process can be formulated as Equation (1).

where

and

are the learnable weights of the two fully connected layers,

is the reduction ratio,

denotes the ReLU function, and

the sigmoid activation.

The architecture of the SE block is illustrated in

Figure 2a, clearly showing the sequential squeeze and excitation stages. This design introduces minimal additional computational costs and has been shown to significantly improve performance across various CNN architectures, making SE a widely adopted attention module in computer vision.

3.2.2. Efficient Channel Attention (ECA)

The Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module is proposed to improve the SE block by eliminating the dimensionality reduction, which leads to potential loss in modeling the channel interactions [

15]. The SE uses a two-layer fully connected bottleneck to capture global dependencies, while ECA, on the other hand, introduces a lightweight layer to capture local cross-channel interaction without adding more complexity. Similar to SE, ECA utilizes global average pooling (GAP) to correlate the spatial dimensions to a channel-wise descriptor, and instead of using a fully connected layer, ECA uses the 1-dimensional convolution to capture dependencies between a channel and its k-nearest neighbors in channel space. The design choices of ECA meant that the original channel dimensionality is preserved and uses fewer computational resources.

Formally, given an input tensor

, ECA performs the operations in Equation (2).

Here,

denotes a 1D convolution of kernel size

applied along the channel dimension. Importantly, the kernel size

is dynamically determined based on the total number of channels

, using the function in Equation (3).

where

and

are hyperparameters, and the result is rounded to the nearest odd integer to ensure symmetric convolution.

This strategy allows ECA to capture local channel interactions efficiently, achieving a good trade-off between performance and complexity. The diagram of the ECA module is depicted in

Figure 2b, emphasizing its simplicity. ECA’s minimal parameter overhead and the ability to be combined with various CNN backbones have made it a widely adopted, scalable, and effective alternative to SE for channel attention modeling.

3.2.3. Soft Attention (CAM-Based Variant)

The Soft Attention module implemented in this study is an adaptation of the channel attention module (CAM) in the CBAM architecture [

23]. It preserves the essential idea of capturing inter-channel dependency by aggregating global average pooling (GAP) and global max pooling (GMP), which is sent to a shared transformation network to output a channel attention map.

Given an input tensor

, the module first computes two descriptors, like in Equations (4) and (5).

These descriptors are passed through a shared transformation function

, consisting of two convolutional layers with an intermediate ReLU activation, as defined in Equation (6).

Each transformed descriptor is subsequently passed through a sigmoid activation, as described in Equations (7) and (8).

The final channel attention map is obtained by summing the two activated paths, as defined in Equation (9).

Finally, the attention map is broadcast and applied to the input tensor through element-wise multiplication, as defined in Equation (10).

The structure of the module is illustrated in

Figure 2c, which accurately reflects the implementation used. Compared to the original CAM, the main difference lies in the placement of the sigmoid activation, which is applied in each branch prior to summation. This change may affect the weighting dynamics and is, therefore, analyzed separately in the experimental results.

3.2.4. Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM)

The Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) is a sequential attention module that effectively leverages channel-wise and spatial attention to improve convolutional features in a lightweight and modular way [

23]. The objective of CBAM is to improve a feature map through learning “what” and “where” to emphasize.

Given an intermediate feature tensor

, CBAM computes an attention-refined output

through two consecutive submodules as indicated in Equation (11).

where

is the channel attention map, and

is the spatial attention map.

Channel Attention Module (CAM)

The channel attention module captures inter-channel relationships using global average pooling and max pooling, followed by a shared MLP and a sigmoid activation as shown in Equation (12).

where

denotes the shared MLP (two convolutional layers with a ReLU activation in between), and

is the sigmoid function.

The input feature map is then rescaled along the channel dimension as in Equation (13).

Spatial Attention Module (SAM)

Next, the spatial attention module focuses on “where” to emphasize, by aggregating spatial information from the channel-refined feature map

. The module computes a spatial descriptor through channel-wise max and average pooling, which is then processed by a convolution and a sigmoid function, as detailed in Equation (14).

where

denotes channel-wise concatenation, and

is a convolutional layer with kernel size

.

The final refined output is in Equation (15).

This sequential combination of channel and spatial attention allows CBAM to progressively enhance feature representations. Its plug-and-play nature, minimal computational overhead, and strong empirical performance have made it a widely used attention module in deep convolutional architectures. The full structure is depicted in

Figure 2d.

Figure 2.

The module structures of the four implemented attention mechanisms. (

a) The squeeze-and-excitation (SE) module [

28], (

b) The Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module [

15], (

c) The Soft Attention module, (

d) The CBAM [

23].

Figure 2.

The module structures of the four implemented attention mechanisms. (

a) The squeeze-and-excitation (SE) module [

28], (

b) The Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) module [

15], (

c) The Soft Attention module, (

d) The CBAM [

23].

3.3. CNN Architectures

The present study adopts two convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures commonly used for the classification of date palm diseases, ResNet50 and MobileNetV2. These architectures have previously achieved strong performance across a broad range of image recognition tasks and provide complementary characteristics for both high-performance and lightweight implementations [

29].

ResNet50 is a 50-layer deep residual network that addresses the degradation problem, which can occur in deep models via identity-based shortcut connections. These residual connections improve gradient flow and allow for more effective training of deep networks [

13]. Due to its strong feature extraction ability and strong reliability during real-world classification of data, ResNet50 is a widely used backbone in deep learning.

MobileNetV2 is a lightweight and efficient CNN architecture designed for models implemented on mobile and embedded platforms [

14]. MobileNetV2 utilizes depthwise separable convolutions and inverted residual blocks containing linear bottlenecks to create a lightweight architecture that drastically reduces the number of parameters and computational costs while maintaining competitive results. The design of MobileNetV2 makes it particularly applicable to tasks that require real-time inference or that have limited computational resources.

The incorporation of both architectures enables cross-comparative analysis among various computational profiles, with ResNet50 possessing high representational capacity and MobileNetV2 focusing on efficient and scalable representation. To further enrich the learning capability of these CNNs, both architectures incorporate an attention mechanism. The integration strategy and design choices are included in the next section.

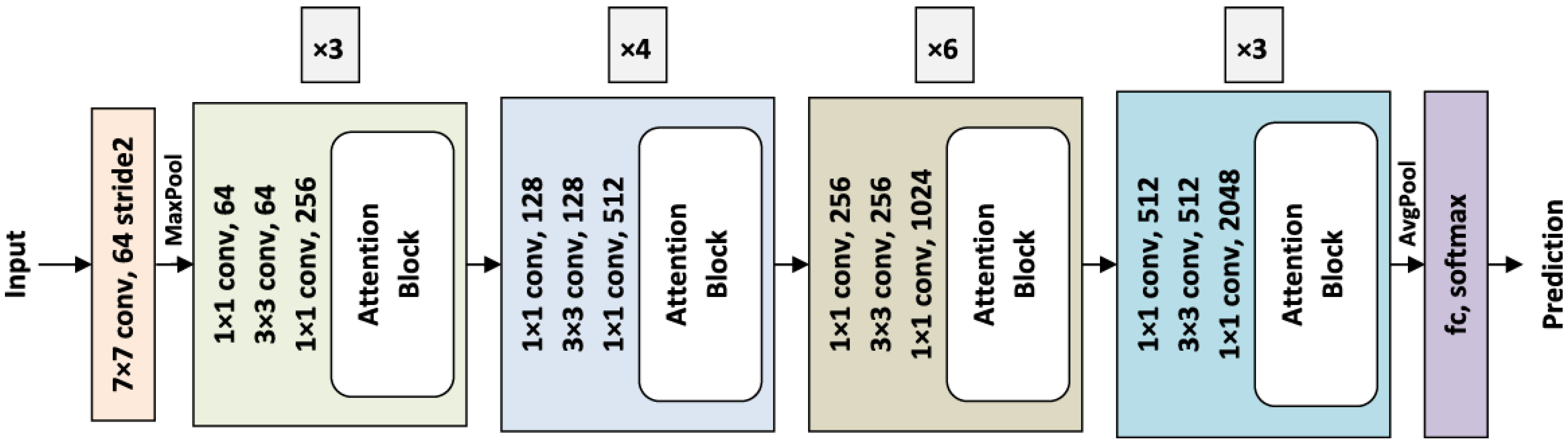

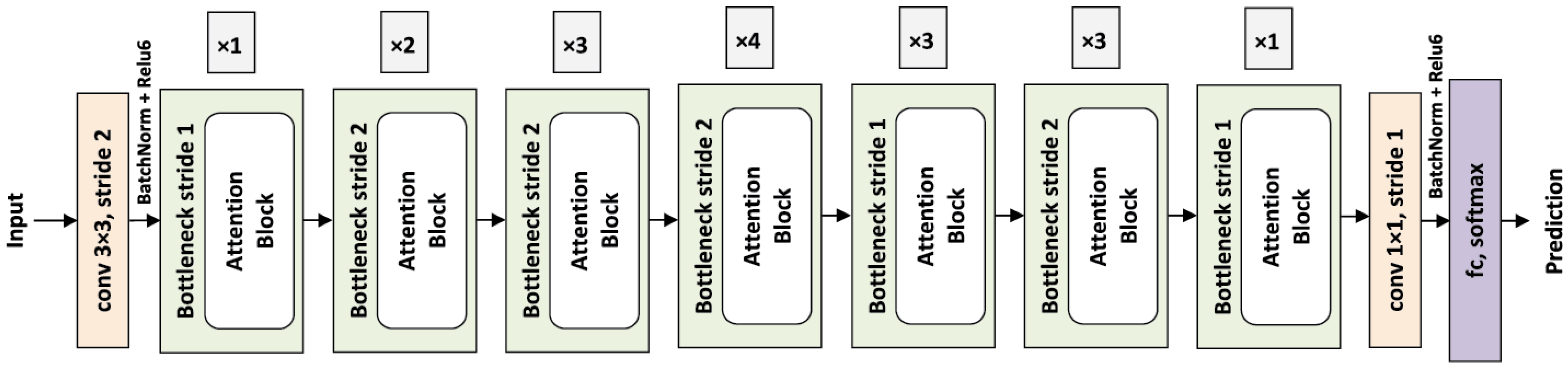

3.4. Attention Mechanism Integration Strategy

To evaluate and compare the impact of different attention mechanisms (SE, ECA, Soft Attention, and CBAM) on image classification performance, we integrated each of them into two widely used CNN architectures: ResNet50 and MobileNetV2. To ensure fairness and consistency across experiments, all attention modules were embedded using a unified strategy that preserves the architectural flow and the number of convolutional blocks in each backbone.

In the case of ResNet50, the attention mechanism was inserted within each Bottleneck block, after the final convolution and before the residual addition. More specifically, the recalibrated feature maps from the attention module are added to the identity mapping only after being refined by the inserted block. This ensures that attention is applied to the output of each residual transformation unit without modifying the overall structure or skip connections.

Figure 3 illustrates the integration strategy of the attention block within the ResNet50 architecture.

For MobileNetV2, the attention mechanism was integrated into each InvertedResidual block, just after the pointwise projection that restores the channel dimensions. This insertion occurs before the optional residual connection, maintaining MobileNetV2’s efficient design while enriching each feature transformation with channel-wise recalibration.

Figure 4 presents the integration approach of the attention block in the MobileNetV2 architecture.

To isolate the effect of the attention modules, we used the same integration pattern for all mechanisms and kept the backbone architecture unchanged outside of the added modules. The original ResNet50 and MobileNetV2 architectures, without any attention mechanism, serve as baselines for comparison. By applying the attention-enhanced versions of the same backbones, we ensured that any observed performance gain can be attributed directly to the attention mechanism rather than other architectural changes.

3.5. Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted using the free-tier Google CoLab computing environment. Due to the limitations that this environment posed (limited GPU access, timeouts, and training duration), it was imperative to take advantage of transfer learning, as this would guarantee the most immediate training and convergence of the model. Depending on system allocations, training was conducted using one of the NVIDIA Tesla K80, T4, or P100 GPUs with a maximum of 12 GB of VRAM. Google Drive was used for additional storage and checkpoints. To reduce the training time, the ResNet50 and MobileNetV2 architectures were initialized with ImageNet-pretrained weights. The original classification layers included were all replaced with fully connected heads specific to these tasks to override the original heads, and all layers were fine-tuned end-to-end to adapt the models for the date palm disease classification task.

The training was performed over a maximum of 35 epochs with an initial learning rate of 0.001. To prevent overfitting and adapt learning dynamics, we used early stopping with a patience of 6 epochs and applied a ReduceLROnPlateau scheduler that decreased the learning rate when the validation loss plateaued (patience = 3). The Adam optimizer and CrossEntropy loss function were used in all experiments.

To assess the impact of regularization, we conducted a grid search over two weight decay values: 1 × 10

−4 and 5 × 10

−4. Likewise, several dropout rates—ranging from 0.0 to 0.5—were tested. When applied, dropout was inserted at the end of the architecture and after each attention block. The final configuration for each model was selected based on the best validation performance. The training hyperparameters used are summarized in

Table 3.

The classification performance was evaluated using four standard metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score, which were computed on the test set according to Equations (16), (17), (18) and (19), respectively.

In addition, Grad-CAM heatmaps were generated for visual interpretability, highlighting spatial regions that most influenced the model’s predictions.

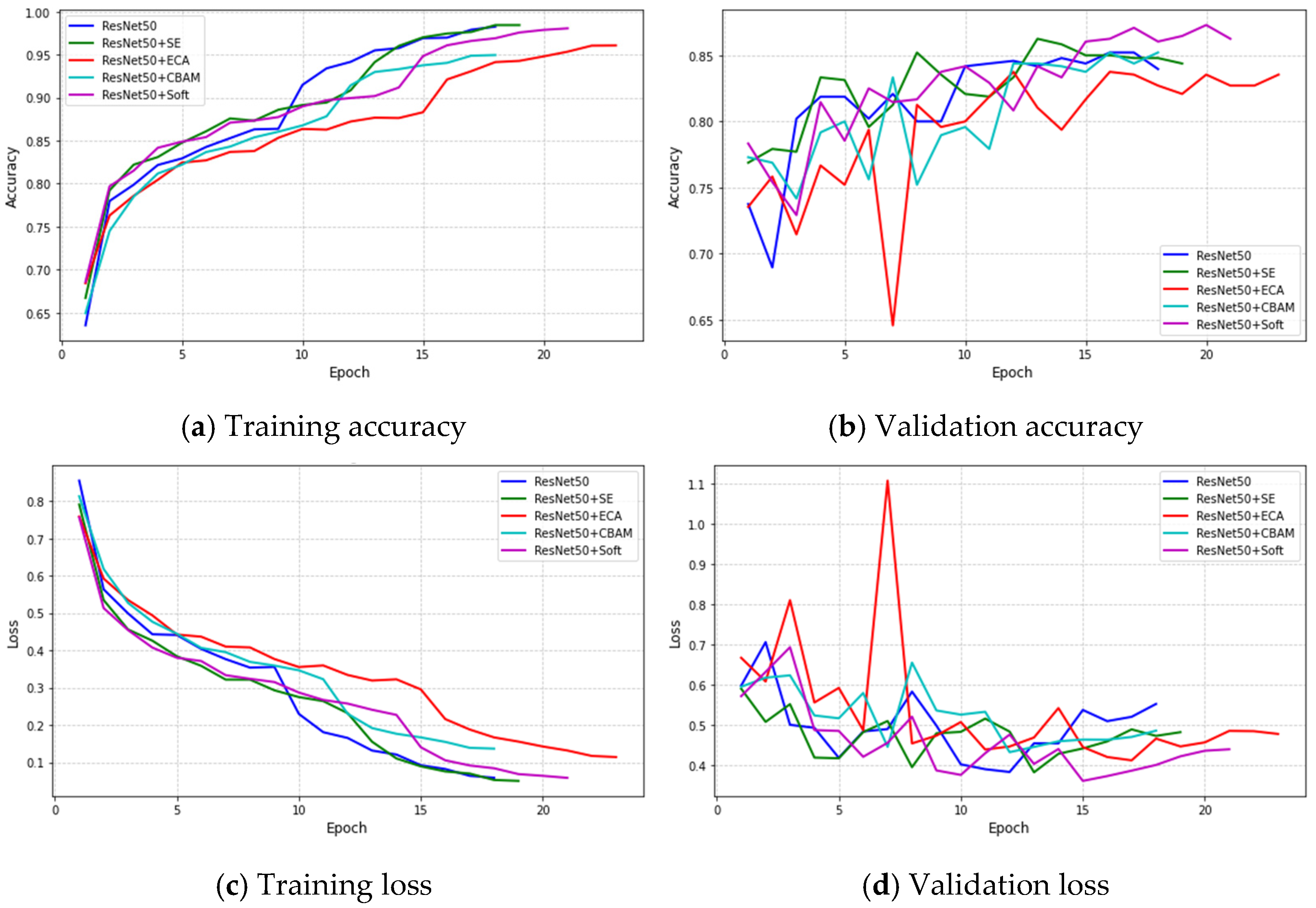

4. Results and Discussion

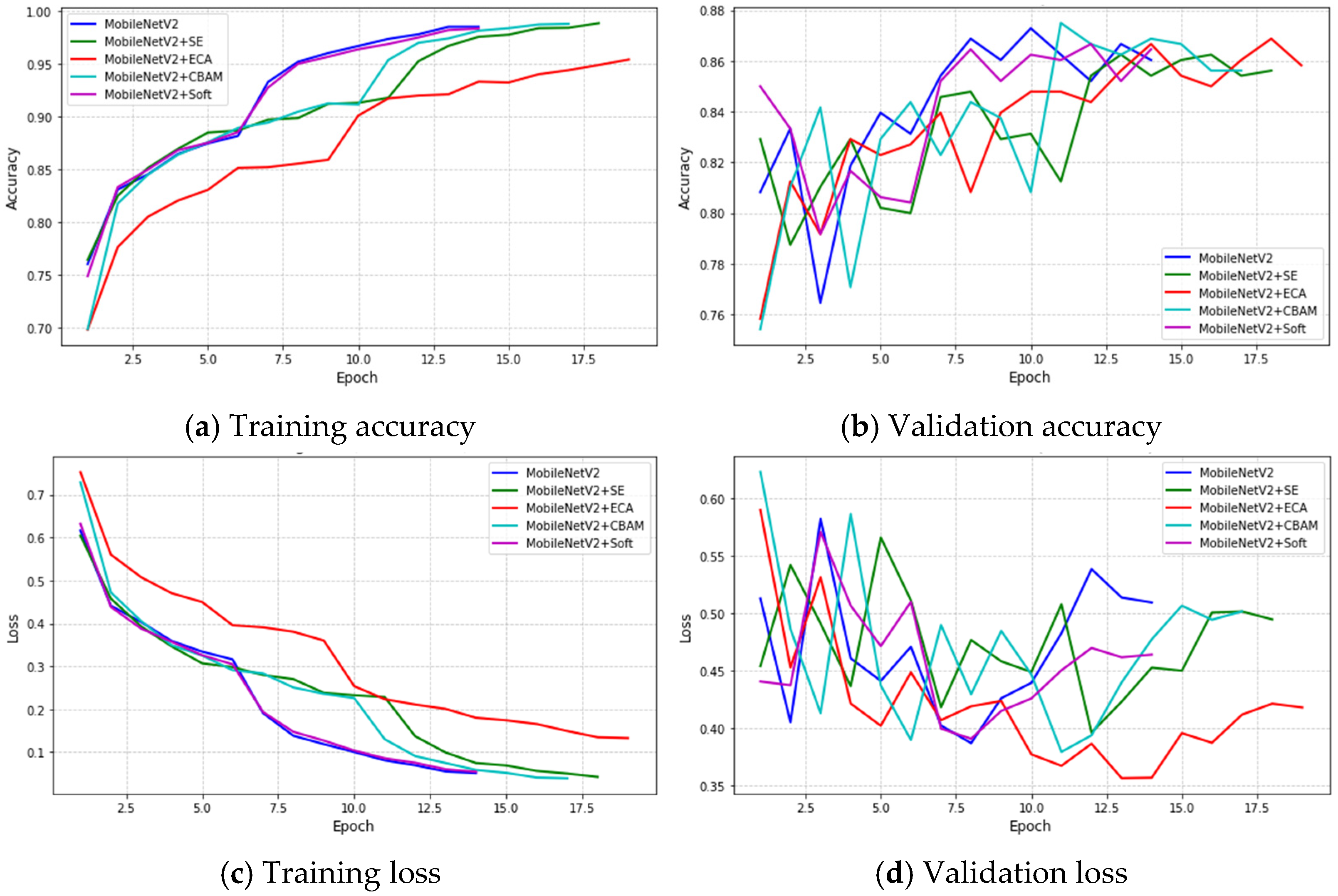

This section presents and discusses the experimental results obtained from the proposed models. First, the training and validation curves (accuracy and loss) are analyzed for each architecture, including ResNet50 and MobileNetV2, as well as their enhanced versions incorporating attention mechanisms (SE, ECA, CBAM, and Soft Attention) in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, respectively. The corresponding classification reports and confusion matrices are then compared to evaluate performance improvements. Subsequently, Grad-CAM visualizations are provided for selected images from the test set to interpret the models’ focus regions, followed by additional analyses on external images to validate the conclusions and assess the generalization capability of the proposed approaches.

4.1. Accuracy and Loss Curves Analysis

In ResNet50 models, the training accuracy shows a generally smooth upward trend towards high values before applying early stopping. The validation accuracy shows a similar trend with minimal divergence from the training accuracy curve, indicating that overfitting was controlled fairly well overall. Notably, the attention-based models reach the training accuracy earlier in the training phase than the baseline models, indicating an improvement in learning through the model for the given task during the training phase. A similar pattern is shown for the MobileNetV2-based models, with the accuracy consistently rising throughout the epochs and a minimal gap between the training and validation curves. Early stopping occurs slightly earlier for some attention-enhanced models due to faster convergence.

For models built on the ResNet50 architecture, it is observed that the training loss consistently decreases across epochs, though the validation loss effectively stabilizes after a few epochs, providing further evidence that the optimization and regularization steps, including early stopping and adaptive learning rate scheduling, were successful strategies. It is worth mentioning that minor oscillations in the validation loss are observed for some models; however, these were associated with non-severe overfitting. In the case of MobileNetV2-based models, the overall trend is similar, with both continuing to decline in training and validation loss throughout the learning process. In certain scenarios, early stopping is triggered after validation loss has not improved significantly to avoid unnecessary training and overfitting.

The analysis of the training and validation curves shows that attention mechanisms improve convergence without affecting training stability. All models display minimal overfitting and good generalization. However, a more detailed comparison of attention methods requires further evaluation using additional performance metrics, which will be presented in the next section.

4.2. Performance and Computational Efficiency of Models with Attention Mechanisms

This section presents and discusses the classification results of ResNet50 and MobileNetV2 models, both in their baseline forms and with attention mechanisms. The analysis focuses on performance metrics for the test set—accuracy, test loss, macro F1-score, micro-AUC, precision, recall, and F1-score—alongside model complexity measures including parameters, model size, FLOPs, and mean training time per epoch.

Table 4 and

Table 5 summarize these metrics for all models, providing a clear comparative overview, while

Table 6 reports the inference time for each model.

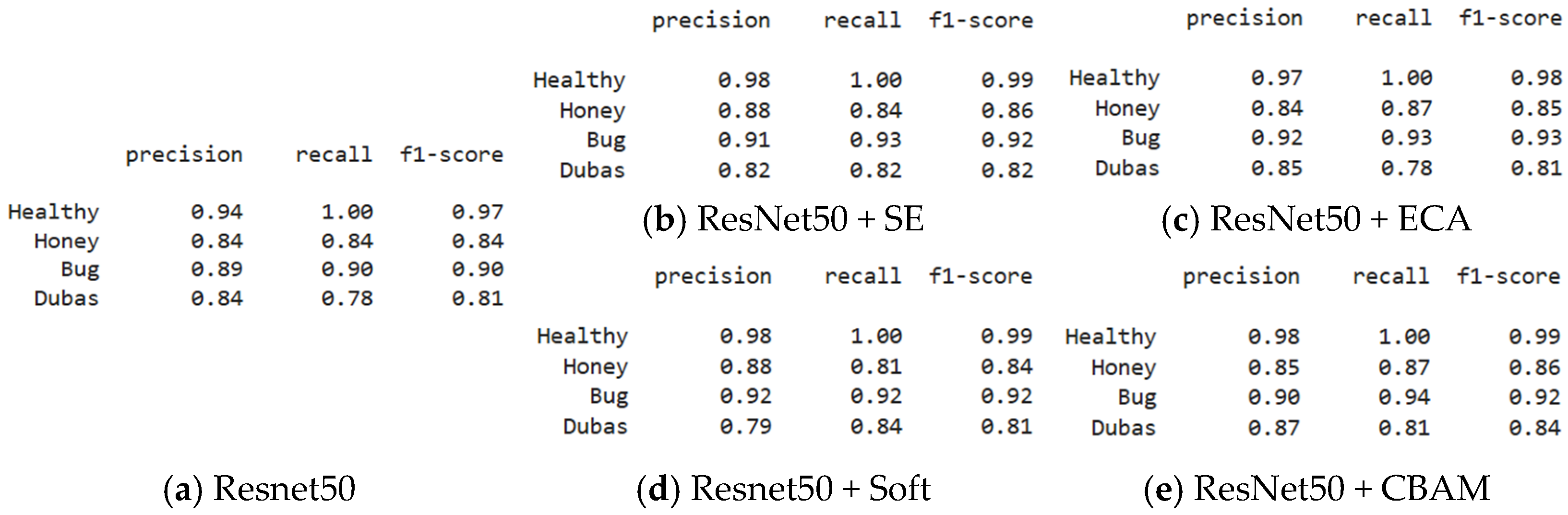

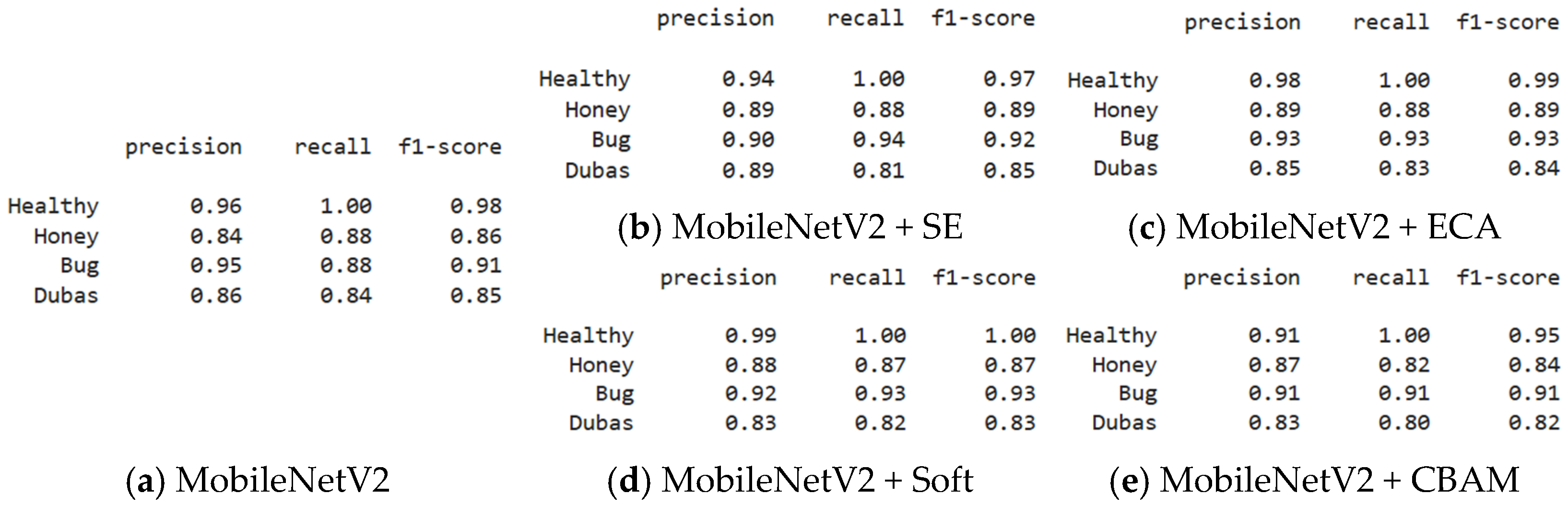

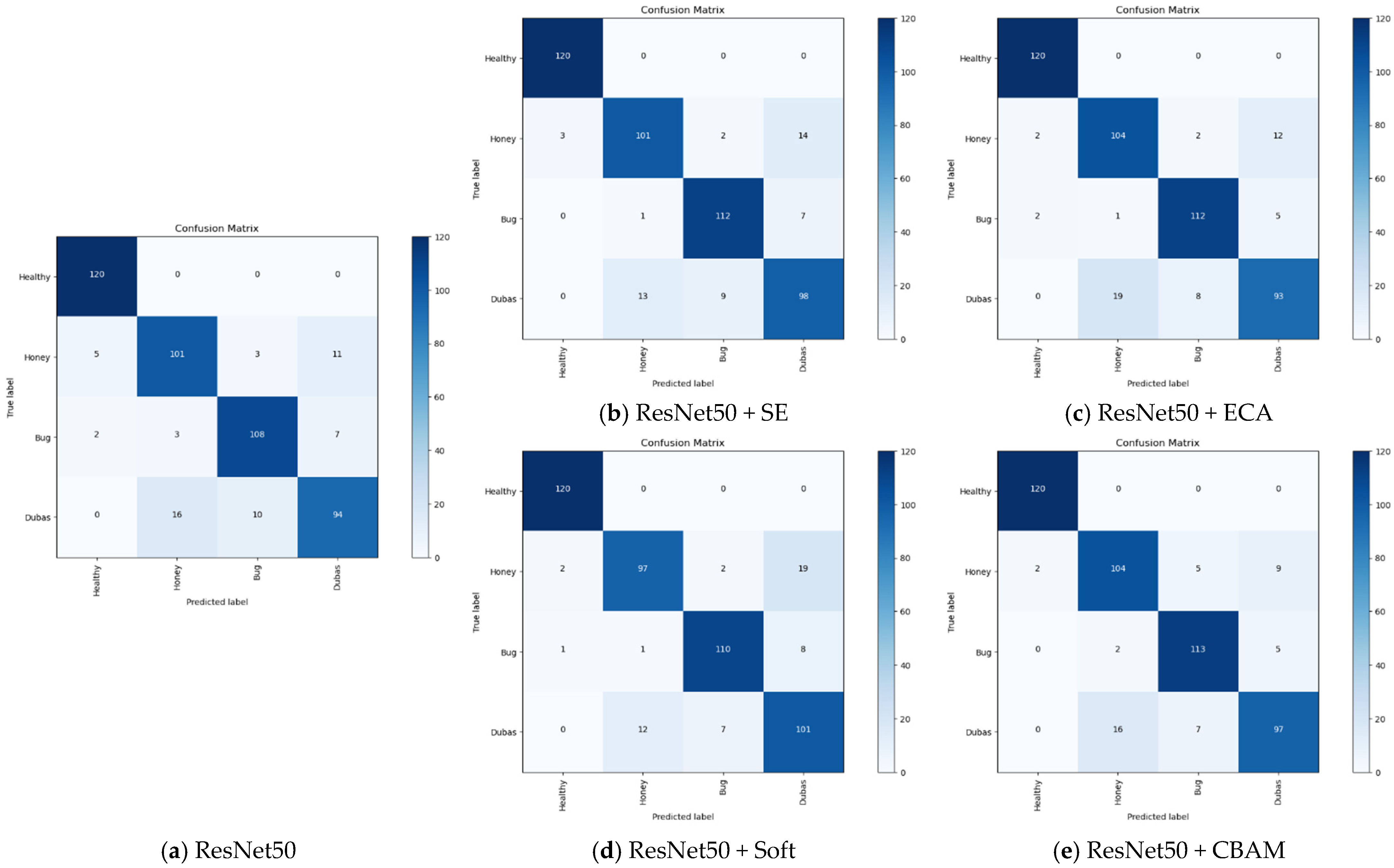

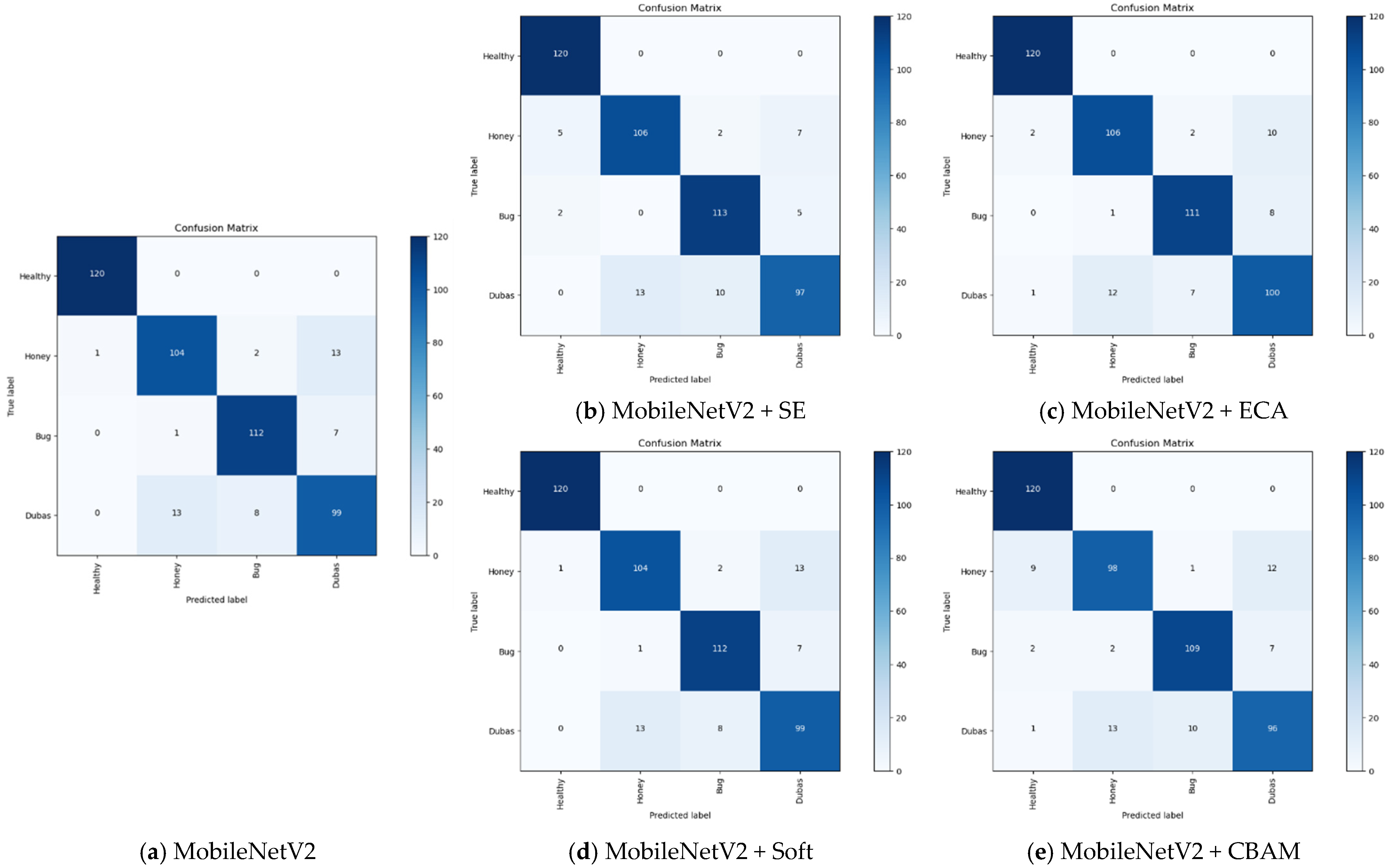

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 display the classification reports for ResNet50 and MobileNetV2, including all attention-augmented variants, while the corresponding confusion matrices are shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10.

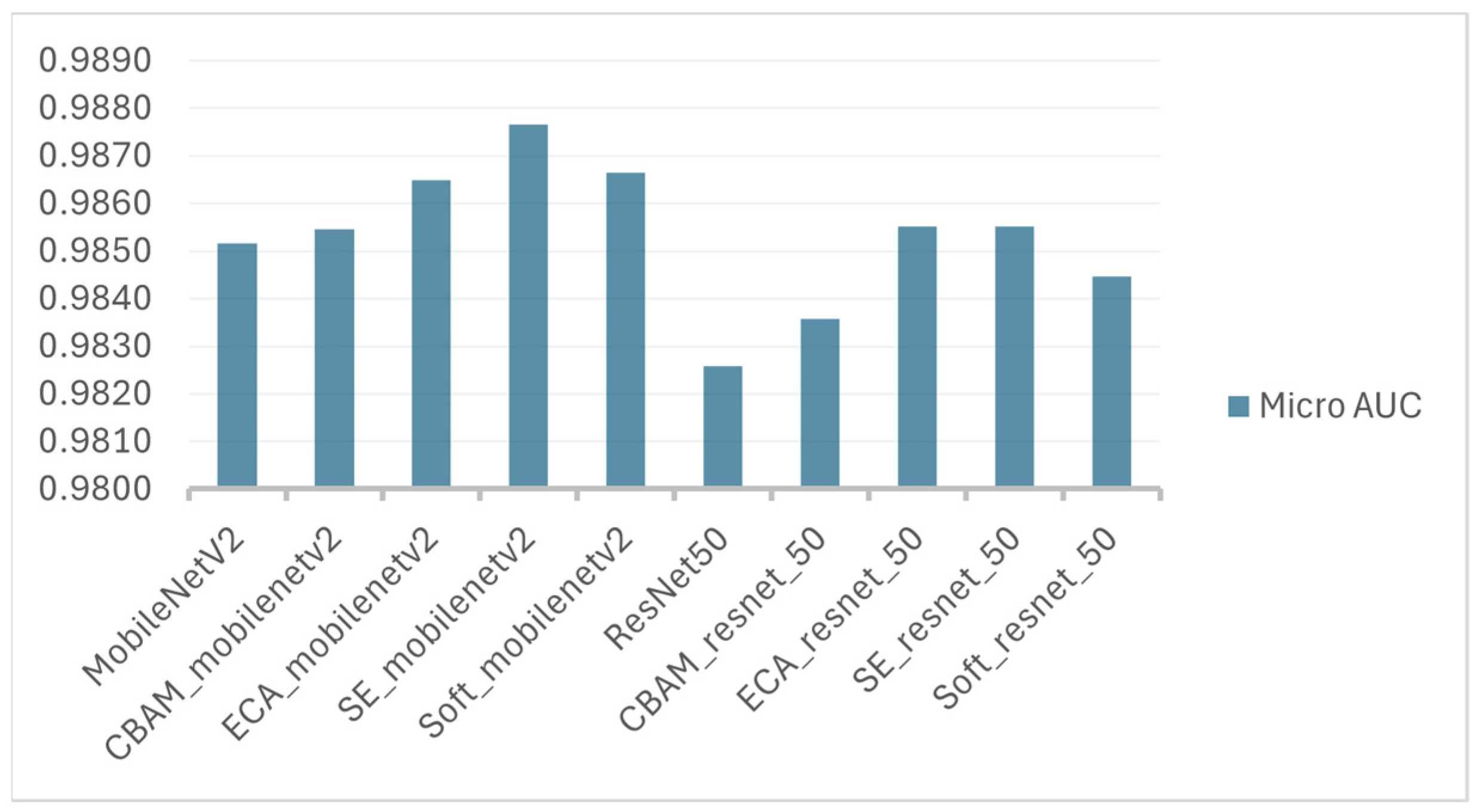

Figure 11 illustrates the micro-AUC distribution across all model configurations using a histogram, and

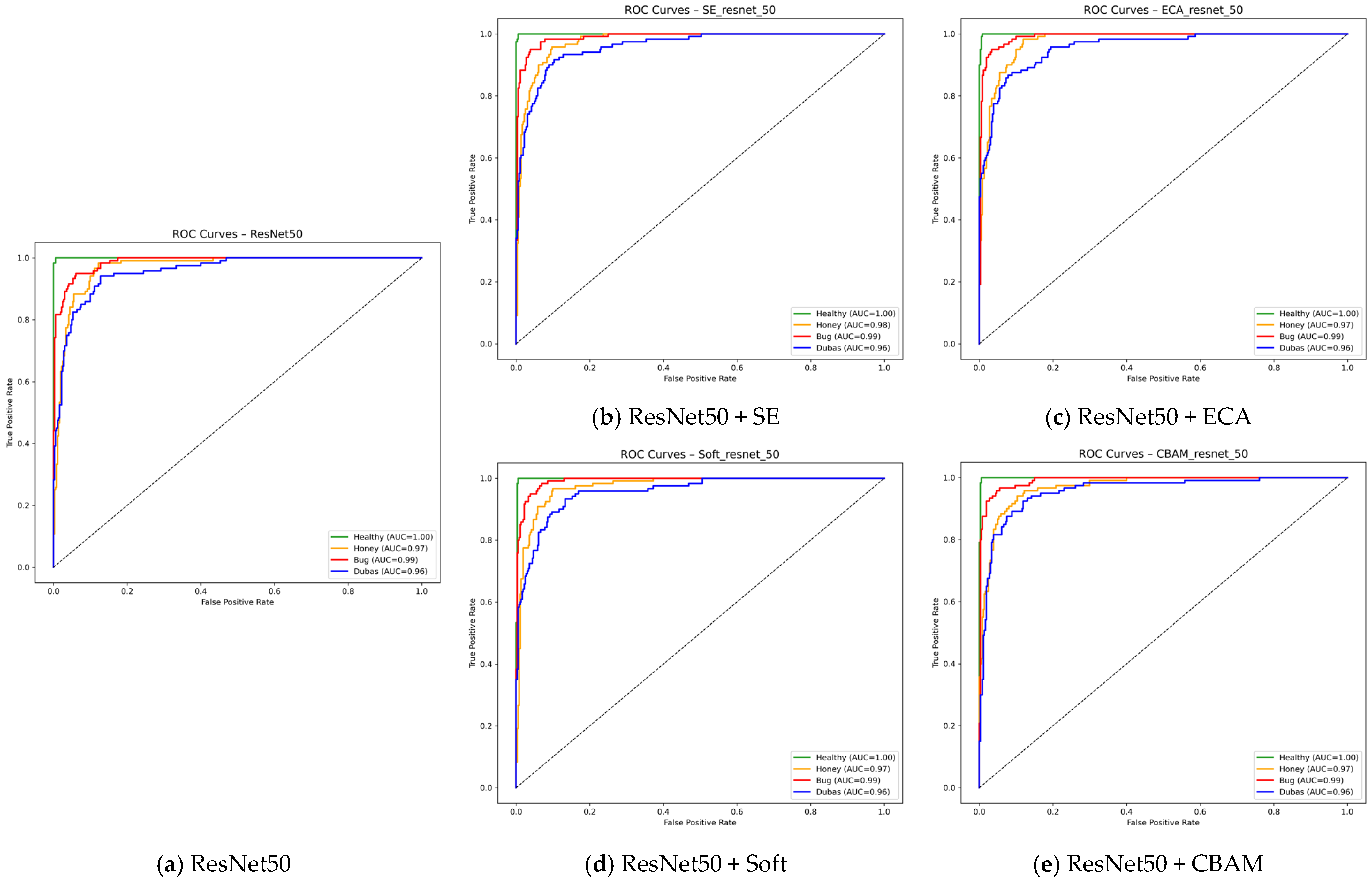

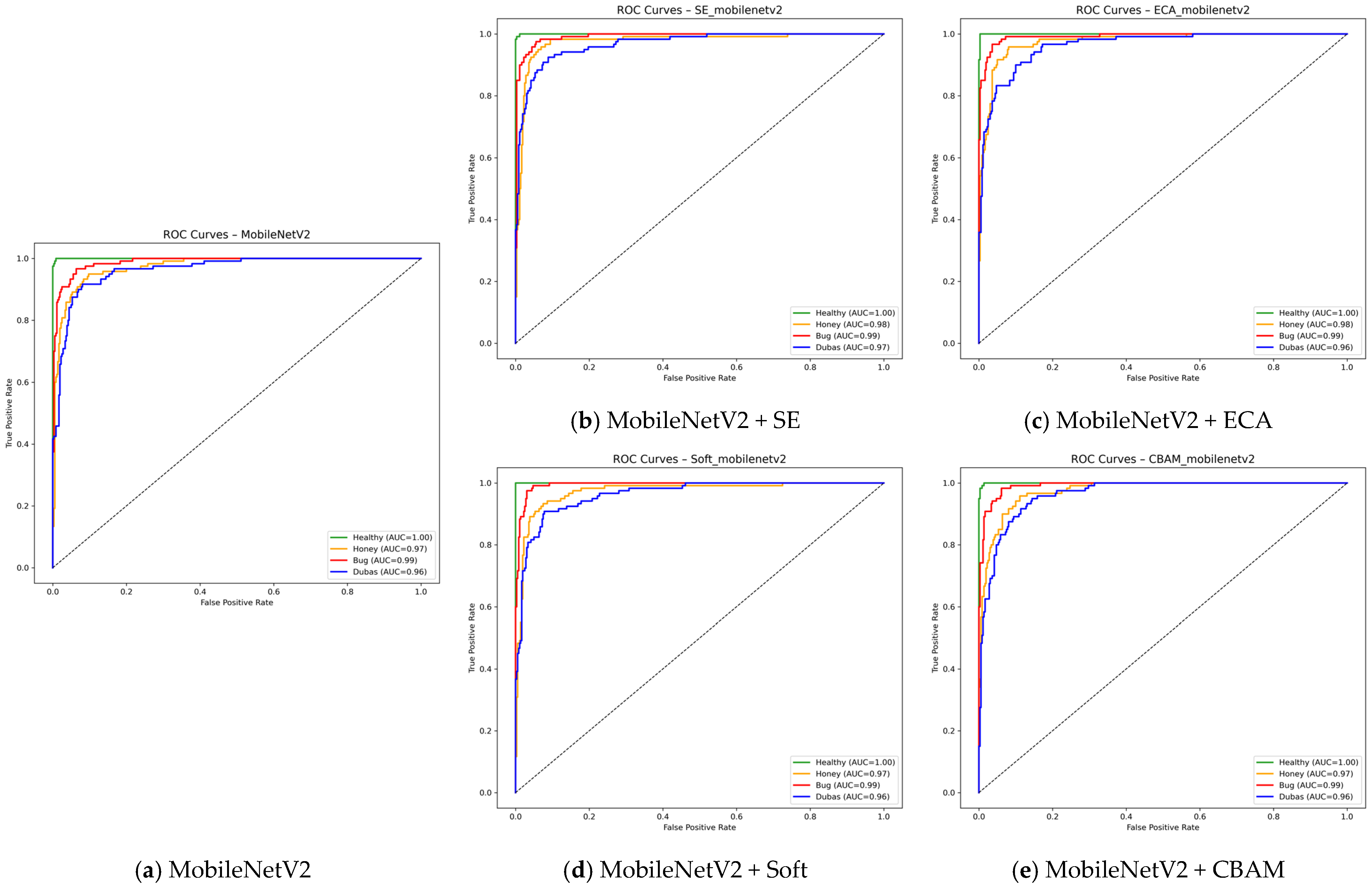

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 present the ROC curves for all models, illustrating their class-wise discrimination performance.

The baseline ResNet50 model achieved a test accuracy of 88.1%, with a particularly high F1-score for the Healthy class (0.97), but relatively lower scores for Honey (0.84) and Dubas (0.81), indicating that these classes are more difficult to classify correctly. The integration of attention modules led to noticeable improvements. Among the tested mechanisms, CBAM provided the highest performance, reaching an accuracy of 90.4%, followed closely by SE (89.8%), Soft Attention (89.2%), and ECA (89.4%). The attention-augmented models demonstrated consistent gains in per-class F1-scores in addition to global improvements. For example, the Dubas class, which exhibited weaker performance in the baseline model, reached an F1-score of 0.84 with CBAM and maintained or improved values in all other configurations. These results confirm that attention mechanisms help the model better capture subtle features, especially for visually similar or ambiguous pest classes.

In the case of MobileNetV2, the baseline model already achieved high accuracy (90.2%), indicating strong performance even without attention. However, integrating attention modules further improved its predictive ability. The best results were observed with ECA and SE, both reaching an accuracy of 91.0%, followed closely by Soft Attention (91.0%). These mechanisms also enhanced the classification quality across all classes, notably maintaining or improving recall for Honey and Dubas. However, CBAM slightly reduced the overall accuracy to 88.1%, which could be attributed to its relatively complex structure, possibly introducing overfitting or architectural incompatibility in the lightweight MobileNetV2 framework. This result highlights the importance of selecting attention modules appropriate to the network’s design complexity and capacity.

By comparing the parameters, model size, FLOPs, and mean epoch training time, it is clear that attention-augmented variants introduce only modest increases in model complexity relative to their baseline counterparts. For ResNet50, adding SE, ECA, Soft, or CBAM slightly increases parameters and model size, which is reflected in longer mean epoch times—from 117.76 s for the baseline to 128.23 s (SE), 133.72 s (ECA), 145.94 s (Soft), and 159.74 s (CBAM)—indicating that training overhead grows moderately with more sophisticated attention modules. MobileNetV2 variants exhibit a similar trend, with mean epoch times rising slightly from 52.82 s for the baseline to 55–61 s for attention-augmented models, while still maintaining the lightweight and efficient nature of the architecture. Overall, these results demonstrate that attention modules can enhance model performance while preserving computational efficiency, with training time increases remaining reasonable for both heavyweight and lightweight networks.

The micro-AUC analysis provides additional evidence on the global discriminative quality of the evaluated models. All architectures achieve high micro-AUC values (>0.98), indicating that the generated probability scores allow for clear separation between classes independently of the decision threshold. For ResNet50, the SE and ECA variants achieve the highest micro-AUC values, suggesting improved feature weighting and enhanced sensitivity to relevant spatial patterns. Similarly, MobileNetV2 benefits from the integration of SE and Soft Attention, which yields the strongest overall separability among lightweight models. Although the performance gains remain moderate (≈0.002–0.004), the consistently high micro-AUC across all networks suggests that the baseline architectures already exhibit strong discriminative power, with attention modules providing incremental but meaningful refinements. These findings are visually confirmed by the micro-AUC distribution shown in

Figure 11.

The ROC curves in

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 provide a complementary view of model discrimination and remain consistent with the overall trends previously observed. For both ResNet50 and MobileNetV2, all attention-augmented variants—SE, ECA, Soft Attention, and CBAM—tend to produce ROC curves that are smoother and shifted toward the ideal upper-left region compared to their respective baseline models. This indicates a generally improved ability to distinguish among classes, even if the relative gain varies across attention mechanisms. These ROC profiles confirm that integrating attention modules enhances the global discriminative behavior of the networks, reinforcing the conclusions drawn from the other performance analyses.

Building on the observed improvements in predictive performance offered by attention mechanisms, we further investigated their computational implications by measuring inference time per image using a dummy input of size 224 × 224 × 3 on a single GPU. For each model, we report the average inference time (ms), standard deviation, and median presented in

Table 6. While the baseline backbones exhibit their inherent efficiency (MobileNetV2 ≈ 4.7 ms/image, ResNet50 ≈ 5.4 ms/image), the type of attention module integrated emerges as the primary factor influencing inference cost. CBAM and Soft Attention introduce the largest overhead (≈12–13 ms/image), reflecting the additional computations required for spatial and channel-wise feature recalibration, whereas SE and ECA result in more moderate increases (≈8–9 ms/image). These findings underscore that attention mechanisms, rather than backbone choice alone, largely determine inference time, and suggest that lightweight modules such as ECA or SE offer a favorable trade-off between enhanced predictive performance and computational efficiency, particularly in resource-constrained deployment scenarios.

In summary, the findings confirm that channel and hybrid attention mechanisms significantly enhance the classification performance of plant disease and pest recognition across both deep and lightweight architectures. The improvements are particularly notable in challenging categories, and even relatively simple mechanisms such as ECA and SE achieve performance comparable to more complex modules like CBAM and Soft Attention, highlighting the relevance of lightweight attention designs for deployment in resource-constrained environments. Moreover, inference time analysis indicates that while baseline backbones differ modestly in computational efficiency, the choice of attention mechanism is the primary determinant of inference overhead: CBAM and Soft Attention introduce the largest increases, whereas ECA and SE maintain moderate inference times, providing a favorable balance between predictive performance and computational cost. Overall, these results support the integration of attention as a practical and efficient strategy for improving accuracy, robustness, and generalization of deep learning models in agricultural diagnostics.

4.3. Visual Interpretability Analysis

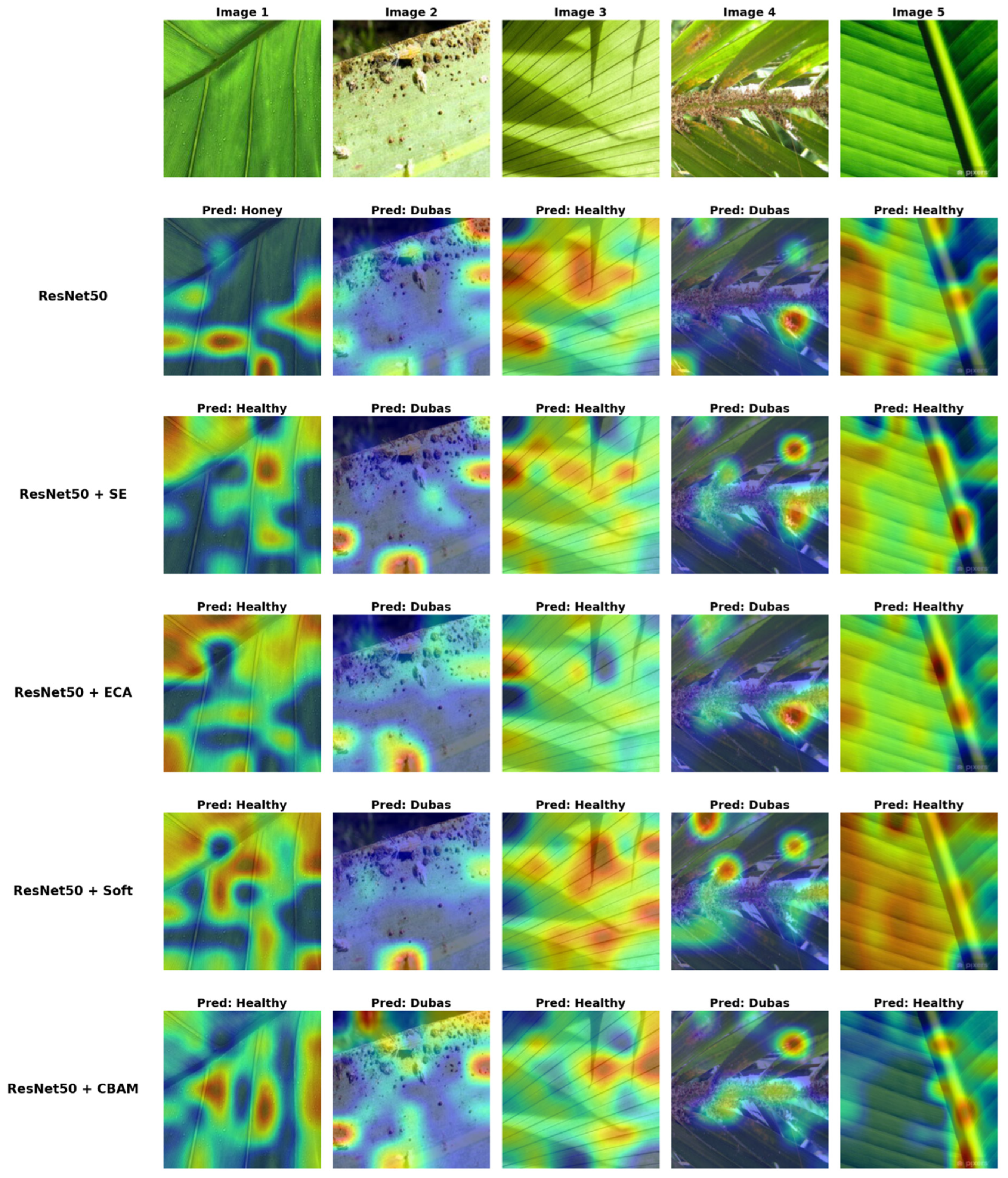

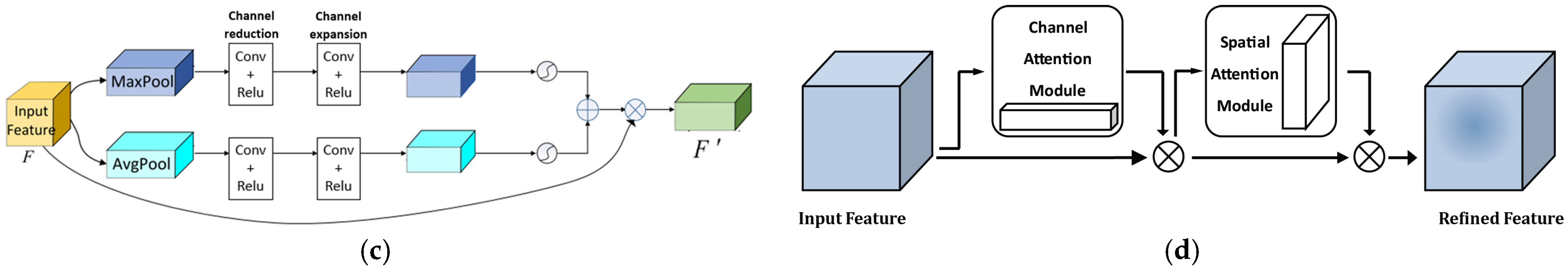

To enhance the transparency of the deep learning models and provide insight into their decision-making process, we applied the Grad-CAM technique to generate class activation maps for a selection of test samples.

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 present qualitative visualizations for two backbone architectures—MobileNetV2 and ResNet50—both in their original forms and with various attention mechanisms integrated, namely SE, ECA, Soft Attention, and CBAM. Each figure displays the original input image along with the corresponding heatmaps, highlighting the discriminative regions that guided each model’s prediction.

As illustrated for the MobileNetV2-based models in

Figure 14, the baseline model demonstrates acceptable classification performance. However, its attention maps often appear diffuse, with focus spread over broad regions of the leaf, some of which are not directly relevant to the disease symptoms. This is particularly noticeable in the second image (True: Bug), where the model misclassifies the sample as Honey. The Grad-CAM visualization reveals that attention is concentrated in the wrong region, which may have contributed to the incorrect decision.

The integration of attention mechanisms significantly improves the interpretability and focus of MobileNetV2-based models. Both SE and ECA modules help the models concentrate on more precise, pathology-relevant areas. For instance, in Honey and Dubas’ examples, the attention maps clearly highlight clusters of insects or areas of secretion that are indicative of the disease, thereby providing visual support for the model’s prediction. Interestingly, while Soft Attention also produces consistent and accurate predictions, its heatmaps are sometimes slightly more diffuse compared to SE and ECA, indicating a broader—yet still relevant—region of focus. On the other hand, the MobileNetV2 + CBAM model, despite being attention-enhanced, tends to generate more dispersed heatmaps, and in some cases appears less capable of isolating the critical regions. This may explain its comparatively lower performance (88.1% accuracy), which is even slightly below the baseline.

For the ResNet50-based models illustrated in

Figure 15, similar trends are observed. The base ResNet50 model generates heatmaps that generally align with the key regions of interest but often lack spatial precision. In certain cases, such as the last column (True: Dubas), the model misclassifies the sample as Honey, and the heatmap reveals attention spread across the leaf surface, missing the key disease indicators. The integration of attention mechanisms once again enhances the focus and interpretability of the model. SE produces the most well-localized attention maps for ResNet50. CBAM, although sometimes capturing relevant regions, generally generates more diffuse heatmaps and spreads attention across larger portions of the leaf.

While models enhanced with the ECA method also provided strong performance, some of the heatmaps were slightly wider in focus and occasionally covered areas surrounding the relevant disease features but were still focused on evidence of the actual disease in the images. Soft Attention, while providing strong performance, showed the potential for a wider focus, especially in cases indicating Honey disease. The Soft Attention heatmaps sometimes included background textures in addition to symptomatic regions.

In general, attention-based models demonstrate a favorable improvement in classification accuracy and visual interpretability. The implementation of the SE and ECA consistently produced tighter, more symptom-specific attention maps that matched expert expectations. However, while CBAM is effective with ResNet50, it seems less appropriate with lightweight backbones like MobileNetV2. Soft Attention remains competitive but focuses on larger, more ambiguous regions and does impact interpretability for some ambiguous cases. These implications highlight the importance of selecting suitable attention mechanisms not only on performance metrics, but with attention to their impact on transparency and correspondence with visual cues of plant disease.

4.4. Quantitative Interpretability Assessment

To complement the qualitative Grad-CAM analysis, we computed two quantitative interpretability metrics for all model variants: Normalized Entropy (lower values indicate more focused attention) and Focus Score (higher values reflect more concentrated activation). The results, summarized in

Table 7, confirm that attention mechanisms generally improve the spatial precision of Grad-CAM heatmaps.

For MobileNetV2, ECA achieves the best interpretability, showing the lowest entropy (0.738) and highest focus score (0.520). SE also improves focus relative to the baseline, while Soft Attention and CBAM tend to generate more dispersed heatmaps, consistent with the qualitative observations of broader or ambiguous attention regions.

For ResNet50, the SE module again yields the most localized attention, reducing entropy and increasing focus compared to the baseline. In contrast, the CBAM variant exhibits the highest entropy (0.901) and lowest focus score (0.313), indicating much more diffuse attention than initially suggested by visual inspection alone. Soft Attention similarly shows elevated entropy and reduced focusing capacity.

Overall, the quantitative results reinforce that SE and ECA provide the most compact and symptom-aligned activation maps, while CBAM and Soft Attention produce wider and less discriminative focus patterns. These findings highlight the importance of selecting attention mechanisms that enhance both predictive performance and interpretable model behavior. A visual summary of these results is provided in

Figure 16.

4.5. Generalization Assessment with Unseen Palm Leaf Samples

To further evaluate the generalization accuracy and interpretability of the models, we examined their predictions on five externally sourced palm-leaf images downloaded from publicly available online repositories. These samples were selected to reflect realistic field conditions and to introduce sources of visual ambiguity that were present in the training data. They included healthy leaf exhibiting natural water droplets that visually resemble honeydew and may induce confusion (Image 1), clearly infested leaves containing Dubas pests (Image 2), healthy leaf affected by shadow patterns cast by surrounding foliage (Image 3), and infested leaves captured at the branch level with dense clusters of Dubas distributed along both sides of the rachis (Image 4), in addition to a clean, uniformly healthy leaf used as a reference sample (Image 5). These external images were never used during training, validation, or testing and served exclusively to assess how the models behave when confronted with unseen real-world conditions. The Grad-CAM visualizations presented in

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 offer further insight into how the models exploited discriminative regions in less-constrained scenarios.

For MobileNetV2-based models, baseline predictions were generally accurate; however, they tended to employ diffuse attention patterns that looked at broad areas of the leaf rather than looking specifically at symptomatic cues, which partly explains occasional cases of misclassifications, such as confusion between honeydew-like droplets and Dubas infestations. The use of SE and ECA modules more clearly improved attention by ensuring the model was attending to localized clusters of insects, or marks in the case of insect secretions, which aligns with the quantitative gains in accuracy (91.0%). Soft Attention slightly improved predictions; however, the predictions still generally had diffuse attention patterns and the heatmaps were still slightly diffuse, confirming the tendency of Soft Attention to distribute its attention across larger areas. In contrast, CBAM produced activation maps that were often scattered throughout the predicted activation maps that could not isolate the area of interest, which was correlated with the statistics for CBAM’s reduced accuracy (88.1%) on the test set.

For ResNet50-based models, the baseline already demonstrated solid predictive ability but sometimes lacked spatial precision, particularly when distinguishing honeydew from Dubas infestations. The addition of attention mechanisms further improved localization and accuracy. SE produced the most localized and symptom-specific attention maps among the ResNet50 variants. CBAM, although achieving good classification accuracy (90.4%), tended to generate more spatially diffuse activation maps, with attention often spread across larger portions of the leaf rather than strictly focusing on symptomatic regions. ECA and Soft Attention also improved over the baseline, but their heatmaps occasionally included surrounding non-symptomatic textures, reflecting a slightly broader focus. Nevertheless, all attention-augmented ResNet50 models demonstrated enhanced transparency compared to the baseline.

In summary, the external sample analysis reinforces the quantitative findings, showing that integrating attention modules into ResNet50 and MobileNetV2 enhances both accuracy and interpretability by guiding the models toward disease-relevant visual cues. These two architectures were deliberately chosen as baselines because they represent widely adopted, stable, and computationally efficient CNN families, enabling a controlled assessment of SE, ECA, CBAM, and Soft Attention across both lightweight and deeper backbones. When viewed in the broader context of recent transformer-based solutions—such as MobileViT, EfficientNetV2, or compact vision transformers like LeViT—our results highlight that attention-enhanced CNNs remain competitive despite the growing popularity of transformer models. While transformers offer superior global context modeling, they typically require larger model sizes and longer inference times, which can limit their applicability in on-field agricultural environments. By contrast, the attention-augmented CNNs explored in this study achieve a favorable balance between accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency, making them particularly suitable for real-world, resource-constrained deployment scenarios in precision agriculture.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this research, we examined the impact of integrating attention mechanisms into state-of-the-art deep learning models applied to the detection of pests and diseases in palm trees. This involved incorporating the SE, ECA, CBAM, and Soft Attention modules into two commonly used convolutional backbones, MobileNetV2 and ResNet50, and reporting their contribution to classification accuracy and interpretability. Our findings demonstrated that attention mechanisms consistently improved model performance and transparency. SE and ECA produced the most stable and symptom-specific results, narrowly directing the model’s focus toward relevant areas of the image while also being computationally efficient. CBAM proved particularly effective with deeper architectures such as ResNet50, but it was less suited for lightweight models like MobileNetV2. Soft Attention produced competitive accuracy and a broader focus. This suggests that Soft Attention may be more robust in addressing more visually complex, diffuse symptoms. Beyond quantitative improvement, the qualitative analysis with Grad-CAM confirmed that attention-based models accomplish salient and localized activation corresponding to expert visual cues, supporting the value of attention in improving not only predictive accuracy but also the interpretability of deep learning in precision agriculture.

For future work, several directions can be explored. First, the integration of transformer-based hybrid architectures or cross-modal attention could improve the representation of the features and the reasoning contextual knowledge. Second, using a larger dataset, which could include images of various environmental and lighting conditions, may improve generalization for real-field deployment. Finally, incorporating spatio-temporal or multispectral data may enable early detection and better differentiation between visually similar symptoms. Overall, the findings of this work provide valuable insights for developing more transparent, efficient, and scalable attention-driven systems for intelligent crop health monitoring.