Abstract

Effective turn-taking is fundamental to conversational interactions, shaping the fluidity of communication across human dialogues and interactions with spoken dialogue systems (SDS). Despite its apparent simplicity, conversational turn-taking involves complex timing mechanisms influenced by various linguistic, prosodic, and multimodal cues. This review synthesises recent theoretical insights and practical advancements in understanding and modelling conversational timing dynamics, emphasising critical phenomena such as voice activity (VA), turn floor offsets (TFO), and predictive turn-taking. We first discuss foundational concepts, such as voice activity detection (VAD) and inter-pausal units (IPUs), and highlight their significance for systematically representing dialogue states. Central to the challenge of interactive systems is distinguishing moments when conversational roles shift versus when they remain with the current speaker, encapsulated by the concepts of “hold” and “shift”. The timing of these transitions, measured through Turn Floor Offsets (TFOs), aligns closely with minimal human reaction times, suggesting biological underpinnings while exhibiting cross-linguistic variability. This review further explores computational turn-taking heuristics and models, noting that simplistic strategies may reduce interruptions yet risk introducing unnatural delays. Integrating multimodal signals, prosodic, verbal, visual, and predictive mechanisms is emphasised as essential for future developments in achieving human-like conversational responsiveness.

1. Introduction

Everyday interactions depend on a shared rhythm of turn-taking that signals when to speak or pause, much like the moves in a simple game of Tic-Tac-Toe. Since speaking while also processing someone else’s words can be challenging, we rely on cues such as vocal inflection and body language to indicate whose turn it is to communicate. This review aims to investigate the mechanisms of turn-taking in conversational systems, drawing on years of study across various fields that have explored these subtle signals to develop technology that replicates this natural exchange. By aligning computers more closely with our innate communication styles, we can enhance accessibility for everyone, thereby eliminating the need for specialised training.

As a careful and engaged conversational partner, you, the reader, process each statement in the same way a listening audience takes in spoken words. Your extensive experience with interpersonal dynamics allows you to identify when to respond, recognise opportune moments to interject and understand when it is better to let others speak. You may recall instances when you unintentionally spoke over someone, or perhaps did so on purpose, waiting for a pause to express your viewpoint. You also know the excitement of sharing an interesting discovery or presenting information that might capture another person’s interest. A simple question can shift your role from speaker to listener, and slight changes in vocal tone can help you maintain or smoothly yield the conversational lead. You are aware of the usual greeting patterns, those brief “How are you?” exchanges guiding our interactions, whether reconnecting with someone familiar or meeting a new person for the first time. By your fiftieth birthday, you have likely processed nearly 100,000 h of spoken conversation [1], averaging about 16,000 spoken words daily [2]. These countless interactions have sharpened your ability to smoothly transition between being a speaker and a listener, providing a strong basis for exploring how conversation fundamentally influences social interaction.

During verbal interactions, conversation partners typically manage speaking and listening in a synchronised process referred to as turn-taking. This dynamic arises not only among humans but also across a variety of animal species [3,4]. Notably, humans begin to develop turn-taking competencies early in infancy: “proto-conversations,” where caregivers and infants alternate vocalisations, emerge long before any formal language structures are in place [5,6]. These basic patterns are remarkably consistent across different linguistic and cultural settings, suggesting an underlying reliance on predictive abilities [7,8,9]. Such abilities enable rapid exchange, frequently within a window of about 200 ms [10,11], which is notably faster than the time generally required to formulate a complete utterance [10].

While humans navigate transitions in conversations almost effortlessly, many current conversational systems still struggle to handle smooth turn-taking. Common issues include poorly timed responses, such as delayed acknowledgments or premature interruptions, as well as failures to recognise when a speaker’s turn begins. These problems can result in overlaps or unfilled pauses, which can frustrate users and lead to miscommunication. For instance, if a virtual assistant interrupts a user mid-sentence, it can disrupt their train of thought; conversely, if the assistant waits too long to respond, the interaction may feel awkward. As artificial intelligence (AI) and social robotics continue to develop, the ability to facilitate seamless spoken interactions has become increasingly important. Recent advances in text-based conversational agents, such as GPT-4 [12] and LLaMA [13], have made significant progress in generating coherent, contextually relevant dialogues. However, transitioning to spoken interaction presents additional challenges. The desire to engage in verbal interaction with sophisticated language models is growing, yet ensuring natural, real-time turn-taking remains an unresolved research issue. Existing studies on turn-taking have explored various aspects, including the detection of turn-end signals, the management of interruptions, and the generation of turn-taking signals. However, several critical gaps still exist. Many current approaches struggle to develop general turn-taking models that can effectively adapt to different interaction styles while remaining robust in human–computer dialogues. Additionally, real-time response timing remains an area of ongoing investigation, requiring models beyond merely minimising pauses and overlaps to capture the nuances of fluid conversation. Further, there is a need for deeper integration of pragmatic understandings, such as recognising the contextual appropriateness of speaking at a given moment, within computational frameworks. Moreover, advancements in predictive modelling, particularly leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs), have opened new possibilities for more sophisticated conversational overlaps beyond simple backchanneling. These limitations in the current research landscape provide the motivation for this review.

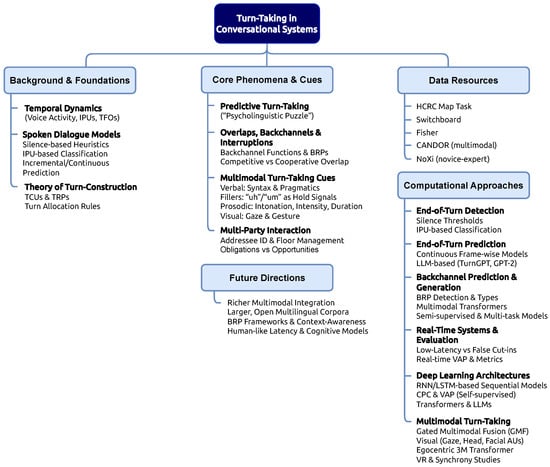

In this review, we integrate insights from human communication research, evaluate contemporary approaches to managing turn-taking in conversational technologies and human–robot interactions, and discuss avenues for ongoing inquiry. At first glance, turn-taking may appear so self-evident that it scarcely merits close study. Yet the next section demonstrates how the seemingly effortless flow of conversation depends on subtle coordination strategies that are easily overlooked without specialised attention. To better organise and contextualise the broad literature on conversational turn-taking, we present a fine-grained survey architecture that categorises existing work into five interlocking domains: (1) Background & Foundations (temporal dynamics, classic dialogue models, and turn-construction theory); (2) Core Phenomena & Cues (predictive timing, overlaps/backchannels, multimodal signals, and multi-party floor management); (3) Data Resources (key corpora such as HCRC Map Task, Switchboard, Fisher, CANDOR, and NoXi); (4) Computational Approaches (from end-of-turn detection and incremental prediction through backchannel modeling, real-time evaluation, foundational deep-learning architectures, and multimodal fusion); and (5) Future Directions (richer multimodal integration, open multilingual corpora, context-aware backchannel frameworks, and human-like latency models). This hierarchical organisation is illustrated in Figure 1. This review article follows a structured organisation to thoroughly explore turn-taking mechanisms in conversational systems. The paper begins with an overview of foundational linguistic concepts related to turn-taking, highlighting its historical and theoretical underpinnings. Next, we will discuss the cues that facilitate turn-taking across multiple modalities, including speech, gestures, and gaze.

Figure 1.

Fine-grained mind-map of turn-taking research in conversational systems, showing how theoretical foundations, observed phenomena, data sets, algorithmic approaches, and future challenges interrelate.

Following this, the article delves into four primary aspects of turn-taking research in conversational systems that have garnered significant attention:

- What signals are involved in the coordination of turn-taking in dialogue?

- How can the system identify appropriate places and times to generate a backchannel?

- How can real-time turn-taking be optimised to adapt to human–agent interaction scenarios and evaluated through a user study involving real-world interactions?

- The handling of multi-party and situated interactions, including scenarios with multiple potential addressees or the manipulation of physical objects, will also be addressed.

Finally, the review identifies promising directions for future research, emphasising gaps such as the need for richer multimodal integration, expanded real-world testing, and cross-linguistic studies. While most computational modelling research in this field has been conducted on English data, this review will include some notable exceptions. If the language of study is not explicitly mentioned, it should be assumed to be English. In this review, we define “recent advances” as research on computational modelling of turn-taking published from late 2021 to the time of publication. This time window reflects the emergence of neural, self-supervised, and multimodal approaches that have reshaped the field in recent years. Foundational studies, including classical work in linguistics, phonetics, and conversation analysis prior to 2021, were used primarily to contextualise or motivate contemporary modelling approaches. Our analysis and synthesis of methods in Section 4, therefore, focus exclusively on developments within this time period.

- Key Terms

- Transition-Relevance Place (TRP) refers to a moment in conversation where a speaker change can appropriately occur.

- Predictive turn-taking describes the use of cues that precede a TRP to anticipate turn completion and plan response timing.

- Voice Activity Projection (VAP) denotes models that forecast near-future speech activity to coordinate responses or backchannels in real time.

2. Background

A defining characteristic of human social interaction is the rapid alternation between speaker and listener roles, commonly referred to as turn-taking. This mechanism is a fundamental aspect of language use, observed universally across cultures, shaping the interactional environment in which children acquire language and in which language itself is believed to have evolved. Additionally, turn-taking is not exclusive to humans; it has been documented in both vocal and gestural communication among various non-human species [14,15,16]. In human conversation, the precise timing of turn exchanges raises intriguing questions about the underlying processes. Speakers typically alternate with minimal pauses on average, nearly matching the human response threshold of 200 ms and with minimal overlap (usually less than 5% of the total speech) [10]. This seamless exchange is particularly remarkable given that individual turns can vary unpredictably in length and content, the number of participants may fluctuate, and longer turns (as when narrating a story) must occasionally be accommodated. For example, during a casual conversation among friends, one speaker might briefly share news, prompting quick responses from others. Later, the conversation shifts to storytelling, with one person speaking uninterrupted for several minutes. Despite these variations, the conversational flow remains smooth, underscoring the human capacity to adjust to conversational demands dynamically. For example:

Speaker A: “Hey, did you hear about the concert next weekend?”

Speaker B: “Oh, yeah! I got my tickets yesterday.”

Speaker C: “Same here, can’t wait!”

(Later in the conversation)

Speaker A: “So, this reminds me of when I attended my first concert years ago. It was raining, and we were waiting outside for hours…” (Speaker A continues narrating uninterrupted for several minutes while others listen attentively.)

The theoretical foundation of turn-taking was initially proposed by American sociologist Harvey Sacks. However, the precise definition of a turn has varied among scholars as turn-taking theory has evolved. The foundational model of turn-taking in everyday conversation was introduced in 1974 by Sacks et al. [8], emphasising the structural organisation of dialogue without explicitly defining what constitutes a turn. This model conceptualises turn-taking as a systematic process governed by two primary components: the turn-constructional component and the turn-allocation component [8]. The turn-constructional component defines the linguistic building blocks of a turn, known as turn-constructional units (TCUs), which may consist of words, phrases, clauses, or complete sentences. The turn-allocation component, on the other hand, governs how the next speaker is selected, either explicitly through the current speaker’s selection (via direct address or gaze) or implicitly through self-selection, where the first participant to initiate speech gains the turn. If neither selection occurs, the current speaker retains the floor and continues speaking, reapplying the rules to prevent excessive silence [17,18,19,20]. The Transition-Relevance Place (TRP) marks the point at which a turn is likely to end, and the speaker’s transition becomes relevant. These TRPs align with syntactic, prosodic, and semantic boundaries, facilitating smooth exchanges [17,21,22,23]. Research has shown that TRPs often coincide with intonational phrase boundaries, reinforcing their importance in turn coordination. However, variations occur depending on conversational context, as specific discourse structures, such as storytelling or explanatory sequences, require extended turns [24]. Beyond these core components, Sacks and his colleagues identified fourteen features characterising turn-taking organisation, illustrating the intricate balance between holding, yielding, and abandoning turns during conversation. These findings underscore that turn-taking is a rule-governed yet flexible system designed to minimise silence and avoid overlapping speech, ensuring conversational coherence and efficiency. The definition of a turn has also evolved, with [25] describing it as a speaker’s continuous utterance within a conversation, concluding when the speaker-listener roles shift, all participants remain silent, or a designated signal indicates a transition. This widely accepted definition aligns with the perspective of [26], which distinguishes between the potential to assume the speaker role and the actual verbal output of the turn, despite differences in theoretical framing. A consistent thread across these perspectives highlights turn-taking as both a structural and an interactive process, essential for maintaining conversational order and efficiency.

The following section explores notable turn-taking phenomena during the initial 15 s of a telephone call between two unfamiliar speakers https://catalog.ldc.upenn.edu/LDC2004S13 (accessed on 8 December 2025). In general, most conversations begin with a greeting phase that serves as a foundational exchange. This greeting phase typically comprises mutual salutations, self-introductions, and brief acknowledgements, which are examples of adjacency pairs [8]. Unlike written exchanges, where a user explicitly sends a complete message (e.g., pressing “enter”), spoken interactions allow participants to speak simultaneously or interrupt each other’s turns. Determining when a speaker has finished an utterance can therefore be far from trivial.

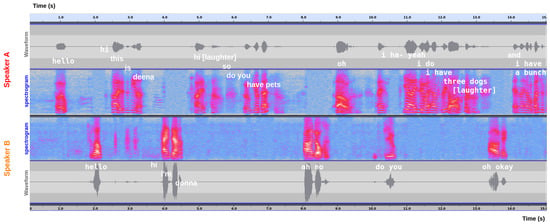

Figure 2 displays the spectrograms and corresponding waveforms of two participants, labelled Speaker A and Speaker B. Each spectrogram shows frequency distribution (vertical axis) over time (horizontal axis), with brighter regions indicating higher acoustic energy. The waveforms, aligned with each spectrogram, highlight amplitude variations of each speaker’s voice. Textual labels placed near the waveforms indicate the approximate timing and content of each utterance.

Figure 2.

Visualisation of the initial moments in a telephone conversation between two unfamiliar speakers. The top panel displays Speaker A’s waveform and spectrogram, while the bottom panel shows Speaker B’s. Brighter regions in each spectrogram indicate higher acoustic energy. The spoken words, such as greetings (“hello,” “hi”) and references to pets (“I have three dogs [laughter]”), are overlaid at their approximate time points. Vertical text placement is adjusted to enhance readability.

The conversation opens with both speakers greeting one another almost in unison (“hello,” “hello”). Immediately afterwards, Speaker A extends a more elaborate introduction (“Hi, this is Deena”), to which Speaker B responds similarly (“Hi, I’m Donna”). This is followed by A’s question (“So do you have pets?”), accompanied by a short laugh and a brief silence. During this pause, B produces a hesitant response (“ah no”), suggesting uncertainty or momentary confusion, as seen in the low-energy portion of B’s waveform. Shortly after, A provides additional information, mentioning multiple dogs (“I have three dogs [laughter]”), while B quickly reacts with an acknowledgement (“Oh okay”). The slight overlap in their waveforms indicates that B’s response starts before A fully finishes laughing.

From a technical perspective, this brief exchange highlights key challenges in spoken dialogue research. The presence of overlapping talk, evident from the partial superimposition of waveforms, raises questions about how interlocutors (human or computational) detect whether a turn is still in progress. Likewise, B’s hesitation noise (“ah”) might be interpreted by an automated system as a more substantive utterance, potentially leading to premature interruption or misinterpretation of turn boundaries. Even within the first few seconds, these subtle overlaps and micro-pauses can disrupt a naive turn-taking algorithm designed for strictly sequential exchanges.

Despite the apparent ease with which humans navigate such interactions, these early moments in a conversation exemplify how spoken dialogue systems can falter. Determining whether a hesitation marks the start of a new turn or simply a filler within an ongoing turn remains an unresolved problem. Furthermore, deciding when to respond, especially if the other speaker has not finished a word or is laughing, poses an equally complex challenge. Although humans have an intuitive grasp of these cues, computational models often lack robust methods for managing rapid turn-taking without unnatural delays or cutoffs. These observations underscore the difficulty of designing computational models that handle rapid turn-by-turn exchanges. Even within the first 10–15 s, multiple overlapping signals appear, such as laughter, hesitations, and truncated phrases. Importantly, there is no comprehensive theory that explains precisely how humans achieve these seamless exchanges, and current models often struggle to replicate this efficiency. As a result, developing robust turn-taking mechanisms remains a key objective for advancing spoken dialogue systems.

2.1. Temporal Dynamics in Turn-Taking

From the perspective of turn-taking, the precise timing of conversational contributions, specifically when individuals begin or end speaking and listening roles, is critical. Timing determines conversational fluidity and directly influences how roles transition smoothly between speakers. The foundational representation of timing information in dialogue research is encapsulated in Voice Activity (VA), a binary encoding indicating speaker activity (active/inactive). Initially conceptualised by [27], voice activity serves as a fundamental tool to examine conversational timing, effectively capturing periods during which a participant contributes vocally.

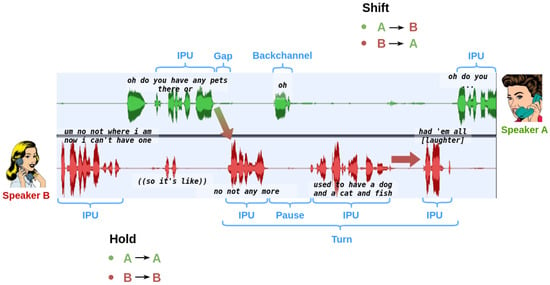

In practical applications, Voice Activity Detection (VAD) can identify periods of speech activity at varying granularities. Typically, frames of around 20 ms (corresponding to a frame rate of 50 Hz) are utilised. These frames help define Inter-Pausal Units (IPUs), speech segments from a single speaker separated by brief silences of less than 100 ms. This method omits brief intra-speaker pauses, which commonly occur between words, and focuses analysis on more significant conversational segments. Within dyadic conversations, the binary states of voice activity for two speakers combine to produce distinct dialogue states: single-speaker activity (A or B exclusively), overlapping speech (both speakers active), and mutual silence. Following [7], the dialogue state transitions are identified as gaps (silence between IPUs from different speakers), pauses (silence between two IPUs within the same speaker, in other words, silence during speaker holds), overlaps-between (overlaps at speaker transitions), and overlaps-within (overlaps starting and ending with the same speaker). A visual representation of these dialogue states and their transitions enhances clarity (as illustrated in Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Visualisation of dialogue activity states during a brief conversational exchange between two speakers (Speaker A (green) and Speaker B (red)). The annotated waveforms highlight the practical aspects of timing in turn-taking, specifically showing how subtle timing differences distinguish among turn-yielding, holding, and overlapping speech.

In natural dialogue, mutual silence frequently signals a pause in active speech, during which conversational roles either shift to a new speaker or remain with the current speaker, referred to as “shift” and “hold,” respectively. Differentiating between these scenarios represents a central challenge for interactive turn-taking systems. Analysing these moments can be enhanced by using the concept of Turn Floor Offset (TFO), defined as the interval between the end of one speaker’s utterance and the beginning of the next speaker’s utterance. Negative TFO values indicate overlapping speech transitions, whereas positive values represent gaps in speech. Studies consistently observe that TFO durations align closely with minimal human reaction times (200 ms), substantially faster than typical speech production times (600–1500 ms) [10,28]. This suggests an underlying biological mechanism, possibly arising from the mutual synchronisation of brain oscillations related to speech rhythm [29]. However, cross-linguistic variations in TFO durations, such as faster transitions in Japanese (0.01 s) compared to slower transitions in Danish (0.47 s), highlight cultural modulation of this phenomenon [30]. Additionally, serial dependencies in TFO durations indicate collaborative coordination between interlocutors rather than individual speaker behaviours [31]. These findings provide valuable guidelines for developing spoken dialogue systems (SDS). Given the dominance of single-speaker activity, SDS should prioritise minimising interruptions by responding primarily during apparent silences. A silence-based heuristic, which suggests waiting about one second before taking the floor, significantly reduces unintended interruptions, although at the risk of appearing sluggish relative to human latency. Additionally, since overlaps frequently occur, especially those signalling a speaker shift, dialogue systems could adopt a policy that treats the emergence of overlap during their speech as a user’s intent to speak, prompting the system to yield the turn promptly. Despite these considerations, overly cautious strategies may inadvertently provoke confusion or unnecessary reengagement from users, indicating the need for more sophisticated turn-taking models to effectively mimic the nuanced timing and responsiveness of human interaction [9,32].

2.2. Implementing Turn-Taking in Spoken Dialogue Systems

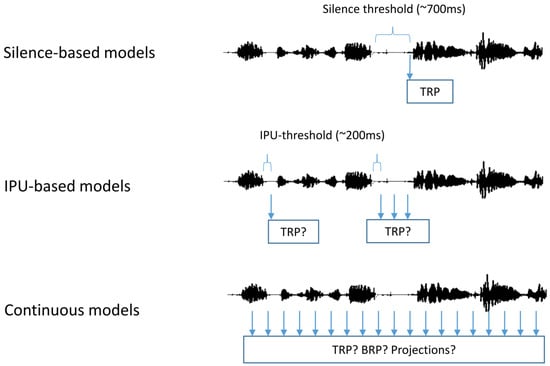

The practical implementation of turn-taking in computational models has largely overlooked the concept of predictive turn-taking. Traditionally, spoken conversational systems have been developed similarly to text-based exchanges, where responses are generated only after the preceding contribution is entirely made. In written dialogue, conversations proceed through complete messages exchanged sequentially, with participants responding only after fully receiving a message. This structured format explains why many spoken dialogue systems have traditionally used a silence-based policy to determine the end of a speaker’s turn by detecting silence exceeding a predefined threshold. This method is depicted in the upper part of Figure 4. Turn-taking models typically differ in how they identify Transition-Relevance Places (TRPs), or points at which speakers can appropriately exchange turns [8]. However, silence-based models are not well-suited to accurately predict TRPs, as silence alone does not always indicate turn completion. Natural conversation frequently contains pauses that are not necessarily turn-ending signals but can indicate hesitation, emphasis, or the planning of further speech. Consequently, silence-based models often misinterpret natural pauses as TRPs, leading to unnatural interruptions or overly delayed responses. IPU-based models improve upon this by analysing inter-pausal units (IPUs), which are short speech segments separated by brief silences, typically around 200 ms. These models classify each IPU boundary as either an actual TRP or a continuation of the current speaker’s turn, as shown in the middle row of Figure 4. Nevertheless, even IPU-based models remain limited by their reliance on predetermined heuristics to identify potential transition points, restricting their ability to predict future TRPs or suitable moments for backchannel responses. The most advanced turn-taking models are incremental or continuous models that actively analyse speech and silence in real time, independently identifying potential TRPs, as depicted at the bottom of Figure 4. By operating continuously, these models are capable of predicting upcoming TRPs even during ongoing speech, enabling smoother conversational transitions and timely backchanneling.

Figure 4.

Illustrations of three turn-taking models. (Top): A silence-based model employs Voice Activity Detection (VAD) to detect the end of the user’s utterance, then uses a predefined silence threshold to decide when to take the turn. (Middle): An IPU-based model identifies Inter-Pausal Units (IPUs) as potential turn-taking points via VAD, analysing cues in the user’s speech, such as pause length, to determine if the turn is yielded. (Bottom): A continuous model processes speech and silence in real time to predict Transition-Relevance Places (TRPs) during both pauses and ongoing speech. This model can also detect backchannel-relevant places (BRPs) and make projections. Source: [9].

2.3. Predictive Turn-Taking

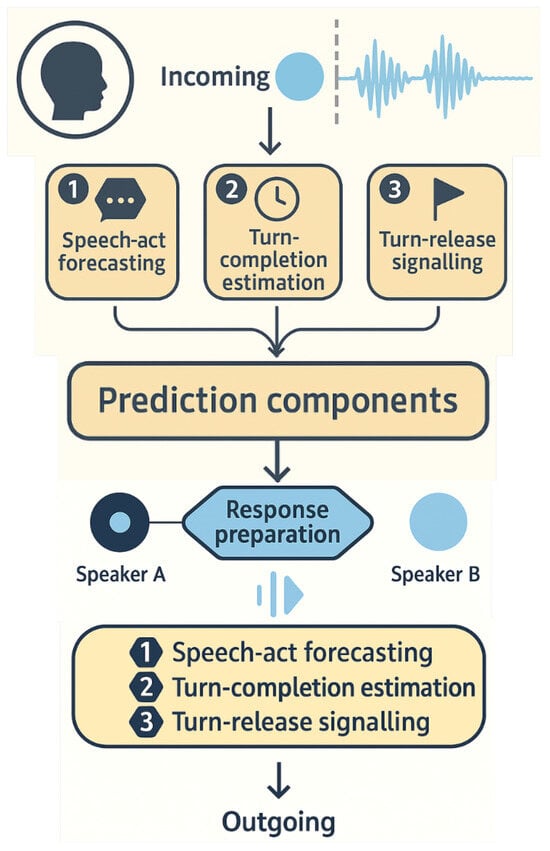

One prominent question in research on conversational turn-taking is the so-called “psycholinguistic puzzle” [10], which highlights the paradox that people often respond to each other in approximately 200 ms. Yet, psycholinguistic estimates place the time needed to formulate and articulate an utterance at 600 ms or more [10]. If listeners waited passively until the speaker’s final word to begin preparing their responses, achieving such rapid turn transitions would be nearly impossible, [10,11,33]. Instead, mounting evidence indicates that dialogue participants engage in continuous processing: the listener actively anticipates turn completions, formulates potential replies, and monitors cues such as syntax, semantics, and speech envelope patterns to initiate the next turn [15,34,35]. This aligns with findings that unaddressed listeners sometimes look to the next speaker even before the current turn finishes [36], suggesting they have predicted not only when the turn will end but also the likely content of the utterance. By planning mid-turn responses, listeners effectively overcome the constraint that articulation can take hundreds of ms to begin. Therefore, a more nuanced view combines predictive mechanisms that allow the listener to guess when the speaker is concluding and reactive cues at the end of the turn, confirming that the utterance is complete [7,10]. This dual perspective helps explain how humans resolve the core of the “psycholinguistic puzzle,” enabling turn-taking at conversational speeds that far outstrip the essential speech production times [11,15], as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Human speech production during spoken dialogue interactions. While listening to the ongoing speech of the speaker, the listener plans, prepares, and detects a suitable transition point to execute their response.

2.4. Overlaps, Backchannels and Interruptions

Backchanneling plays a crucial role in human conversation, enabling listeners to provide real-time feedback without interrupting the flow. Initially conceptualised by [37], backchannels are brief, non-intrusive responses such as “uh-huh,” “mm-hm,” or “yeah,” which serve to indicate active listening and engagement without signalling an intention to take the turn. Beyond verbal affirmations, nonverbal cues such as nodding, facial expressions, and gaze shifts also serve as backchannel responses, reinforcing the listener’s attentiveness. These feedback mechanisms contribute to the smooth progression of discourse by ensuring speakers feel acknowledged and encouraged to continue their turn. As a result, backchanneling has become a significant area of study in spoken dialogue systems (SDS) and human–robot interaction (HRI), where accurately modelling such responses is essential for achieving natural and fluid conversations. Backchannels differ from traditional turn-taking mechanisms in that they do not claim the conversational floor; instead, they operate within a separate communicative track. Ref. [38] categorises these as occurring in “Track 2,” running parallel to the primary discourse in “Track 1.” This distinction is particularly important in SDS and HRI applications, as failing to identify backchannels correctly can lead to misinterpretations, resulting in a system either interrupting the speaker or failing to provide appropriate feedback. Furthermore, determining what precisely constitutes a backchannel is not always straightforward, as backchannels exist on a spectrum ranging from simple acknowledgements (e.g., “uh-huh”) to more extended interjections (e.g., “interesting,” “yeah right”) that may overlap with discourse markers [39]. Because backchannels frequently occur during overlapping speech, they likely account for a substantial portion of the observed overlap in natural dialogues. However, distinguishing between cooperative and competitive overlaps remains an ongoing challenge in SDS and HRI system development.

Overlapping speech occurs frequently in conversation, but not all overlap constitutes a communication breakdown. Ref. [40] argues that overlap should not merely be seen as “failed” turn-taking, as it often facilitates conversational fluency. Ref. [41] distinguishes between competitive and cooperative overlaps, where competitive overlaps reflect an attempt to seize the conversational floor, while cooperative overlaps serve as collaborative mechanisms that enhance dialogue continuity. Among cooperative overlaps, backchannels (continuers) such as “uh-huh” and “mm-hm” hold a unique position, as they signal continued attention rather than an attempt to take the turn. Other cooperative overlap types include terminal overlaps, where a listener predicts the end of the turn and starts speaking slightly before its completion, conditional access to turn, where a listener helps complete an utterance (e.g., recalling a forgotten name), and choral talk, where speakers jointly produce speech, such as in laughter or simultaneous greetings [42]. The acoustic and prosodic properties of backchannels help differentiate them from full-fledged turns or interruptions. Research by [41,43] has shown that competitive overlaps, instances where a listener attempts to seize the conversational floor, are often marked by increased pitch, intensity, and abrupt timing. In contrast, cooperative overlaps, including backchannels, tend to exhibit softer intensity and align with the speaker’s ongoing prosodic patterns. Similarly, competitive overlaps require resolution mechanisms, as participants must decide who retains the conversational floor. Ref. [41] found that most competitive overlaps resolve within one or two syllables, with one speaker ultimately yielding. Unlike competitive overlaps, interruptions introduce an additional layer of complexity. While overlaps can be objectively identified in a corpus, interruptions require interpretation, as they involve a participant violating the speaker’s right to speak [44]. Notably, interruptions can occur without any overlap, such as when a speaker pauses mid-turn but has not yielded the floor, and another participant begins speaking [45]. This distinction is particularly relevant for SDS design, as dialogue systems must avoid prematurely taking the turn when a pause does not indicate a Transition-Relevance Place (TRP). Ref. [45] further found that interruptions, whether overlapping or non-overlapping, often feature higher intensity, pitch, and speech rate, characteristics that can help distinguish them from backchannels.

One major challenge in computational backchanneling models is accurately timing responses. Ref. [46] introduced the concept of backchannel-relevant places (BRPs), which refer to specific moments during a conversation when a speaker expects minimal listener feedback without relinquishing their speaking turn. Unlike Transition-Relevance Places (TRPs), which indicate points for speakers to exchange turns, BRPs identify times suitable for brief listener responses, like “uh-huh” or “mm-hmm,” without interrupting the main speaker. Computationally identifying BRPs involves analysing speech features like pitch, loudness (intensity), and rhythm. Ref. [47] observed that backchannels in Japanese conversations typically follow approximately 200 ms after low-pitch segments, a pattern also identified in English dialogues by [48], who found rising pitch and increased intensity preceding these minimal responses. Beyond these descriptive findings, several real-time frameworks now exist for automatic BRP detection (see Section 4.2), including Voice Activity Projection variants fine-tuned for “continuer” versus “assessment” backchannels [49], transformer-based audio–visual fusion models [50], and temporal-attention classifiers robust to unbalanced data [51]. Besides prosodic cues, accurately predicting when backchannels should occur is essential. Traditional dialogue systems usually respond only after explicitly detecting that the current speaker has stopped speaking. However, research by [11] highlights the importance of predictive processing, suggesting listeners actively anticipate when a turn might end and the type of response required. This view aligns with the entrainment hypothesis from [29], which suggests that synchronisation between brain activity and speech rhythms helps listeners anticipate speech timing. Incorporating predictive mechanisms into spoken dialogue systems (SDS) and human–robot interactions (HRI) can make these interactions feel smoother and more natural. Despite advances, backchanneling models still face significant challenges. One major issue is the ambiguity of backchannels, which can change meaning depending on prosody and conversational context. Ref. [52] illustrated how differences in intonation can alter the meaning of responses; for example, an elongated “yeah…” with a falling pitch might indicate uncertainty rather than agreement. Similarly, ref. [53] highlighted that the word “okay” might serve multiple functions, such as a simple acknowledgement or a discourse marker, depending on the situation. Such ambiguity requires more sophisticated, context-aware models for reliable detection and generation. Another critical challenge is integrating multimodal signals. While most current models primarily handle verbal backchannels, non-verbal cues such as nodding, facial expressions, and posture changes significantly influence natural human communication. Research indicates that combining verbal and visual feedback enhances interaction quality [54]; yet synchronising these signals in real-time remains technically challenging due to variations in human response timing [55]. The incorporation of gaze-based methods for eliciting backchannels, as discussed by [54], presents a significant opportunity to enhance interaction quality in SDS and HRI contexts.

2.5. Multi-Party Interaction

Multi-party turn-taking presents a complex challenge in spoken dialogue systems (SDS) and human–robot interaction (HRI) because it requires managing multiple interlocutors simultaneously, unlike in dyadic conversations, where turn-taking transitions involve only two participants: the speaker and the listener. Multi-party interactions require mechanisms to regulate turn allocation, participation roles, and interruptions effectively [56]. These interactions introduce several layers of complexity, including dynamic shifts in speaker roles, overlapping speech, competition for the floor, and the need for efficient coordination mechanisms to maintain coherence and engagement among multiple participants [57].

In dyadic exchanges, turn-taking is often regulated through a combination of verbal, prosodic, and non-verbal cues such as intonation shifts, syntactic completion, eye gaze, and pauses [48]. However, additional mechanisms are required to manage turn allocation in multi-party settings. Speakers must determine not only when to yield their turn but also whom to address next, making the selection of the next speaker a critical component of conversation regulation [58]. One of the primary strategies for resolving this challenge is gaze coordination, in which speakers typically establish eye contact with the intended next speaker before yielding the turn [59]. In HRI, gaze tracking enables conversational agents to anticipate turn transitions and select the appropriate interlocutor based on mutual visual engagement. Moreover, head pose tracking has been recognised as a more robust alternative to gaze tracking, particularly in environments where precise eye-tracking systems are infeasible [60]. Studies have demonstrated that head orientation is a strong indicator of attention direction and turn allocation, particularly in multi-party human–robot discussions [61,62]. When combined with verbal and prosodic cues, head movement data enhances dialogue systems’ ability to infer turn-taking intentions accurately.

Obligations vs. Opportunities in Multi-Party Turn-Taking

In multi-party interactions, turn-taking is not simply a matter of either yielding or holding the floor. Conversational agents must distinguish between two types of situations: obligations, instances in which the system is directly addressed and required to respond, and opportunities, instances in which the system can choose to contribute but is not obligated to do so [56]. Recognising these distinctions enables dialogue systems to engage more naturally in multi-party discussions, allowing them to adapt dynamically to the conversation context. For instance, a study on turn-taking in human–robot collaborative games found that the presence of multiple participants necessitated a system to make informed decisions about when to take a turn, based on the nature of the utterance, user engagement, and task relevance [57]. By leveraging probabilistic models, systems can score turn-taking opportunities and obligations, balancing responsiveness with conversational fluidity.

2.6. Datasets

A practical initial approach to reveal significant insights regarding turn-taking is to utilise an extensive database of recordings of individuals participating in spoken dialogue. These resources enable researchers to rapidly isolate and scrutinise specific conversation segments, extracting data pertinent to their investigative goals. Although a dataset that fully encompasses the range of human spoken communication would be ideal, such a comprehensive collection remains unfeasible in practice. Consequently, this section highlights publicly accessible and highly utilised datasets that focus on turn-taking, backchanneling, multi-party interaction, and multimodal turn-taking, which have significantly influenced the study of conversational dynamics. These datasets were chosen for their availability, established use among researchers, and overall contribution to the field of conversation analysis.

2.6.1. HCRC Map Task Corpus

The HCRC Map Task Corpus [63] is a unique dataset of unscripted, task-oriented dialogues designed to study spontaneous speech and the process of achieving communicative goals. It involves 128 dialogues (approximately 15 h) between pairs of participants collaborating to reproduce a route on a map. The corpus systematically manipulates the familiarity of speakers (familiar/unfamiliar) and the presence or absence of eye contact. The landmark names used in the task were chosen to facilitate phonological studies. While split-screen video recordings were made, digital audio recordings and verbatim orthographic transcriptions with detailed markup of spoken phenomena, such as filled pauses and interruptions, were the primary data modalities. The Map Task is highly relevant for examining how turn-taking is organised in a goal-oriented setting and how different contextual factors (familiarity, visual interaction) influence dialogue. It can also offer insights into the role of verbal feedback, similar to backchanneling, in guiding the task. It focuses on dyadic interaction within a specific communicative task. Its strengths include the controlled elicitation and the systematic variation of social cues. However, its task-specific nature might limit the generalizability to entirely natural conversations, and the participant pool was primarily comprised Scottish English speakers. The corpus was initially available on CD-ROM and may be accessible through academic repositories.

2.6.2. Switchboard Corpus

The SWITCHBOARD Corpus [64] is a foundational resource for research in speech processing, particularly in speaker authentication and extensive vocabulary speech recognition. It comprises a vast collection of spontaneous conversational speech and text automatically captured over telephone lines. The corpus includes approximately 2500 conversations from 500 speakers representing various dialect regions across the U.S., amounting to over 250 h of speech and nearly 3 million words of text. A key feature of this corpus is the time-aligned, word-for-word transcription that accompanies each recording. The data acquisition process was automated, which helped ensure consistency and reduce the risk of experimenter bias. Additionally, demographic information about the speakers, such as age, gender, education, and dialect, is stored in a database linked to the call details (including the date, time, and length of the conversation). SWITCHBOARD is particularly relevant for studying dynamics such as turn-taking in telephone conversations, the linguistic realisation of backchanneling, and variations in speech related to turn management among different speakers. Its size and diverse speaker population are significant strengths, making it a cornerstone for training and testing speech algorithms. However, the corpus has some limitations, including the constraints of telephone bandwidth, which can affect audio quality, and the absence of direct multimodal information, such as video or facial cues. The SWITCHBOARD corpus is publicly available through the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

2.6.3. Fisher Corpus

The Fisher Corpus [65], designed under the DARPA EARS initiative, focuses on English conversational telephone speech. Its primary goal was to provide a large volume of transcribed telephone speech to advance automatic speech recognition (ASR) technology. The collection aimed for 2000 h of conversational speech from many subjects, with individual calls lasting no more than ten minutes. A distinguishing characteristic is its platform-driven collection protocol, in which the system initiated most calls and participants spoke on assigned topics selected at random to encourage a broad vocabulary. The corpus aimed to represent subjects across various demographic categories, including gender, age, dialect, and English fluency. Fisher is relevant for studying turn-taking in the context of specific topics and a diverse speaker base over the telephone. While not its primary focus, the linguistic patterns of backchanneling within these conversations could also be investigated. It focuses on dyadic interaction. The corpus’s strength lies in its large size and demographic diversity, designed to maximise inter-speaker variation. However, it shares the bandwidth limitations of telephone speech and lacks multimodal data. The Fisher Corpus was collected by the Linguistic Data Consortium (LDC), and access is typically granted through them.

2.6.4. CANDOR Corpus

The CANDOR (Conversation: A Naturalistic Dataset of Online Recordings) corpus [66] represents a significant advancement in conversational interaction datasets by offering a sizeable multimodal collection of naturalistic conversations recorded over video chat. It encompasses 1656 conversations from 1456 unique participants, resulting in over 7 million words and 850+ h of audio and video. A unique aspect includes moment-to-moment vocal, facial, and semantic expression measures derived through a sophisticated computational pipeline. This includes textual analysis of semantic novelty, acoustic analysis of loudness and intensity, and visual analysis of facial expressions (e.g., happiness) and head movements (e.g., nods, shakes). The corpus also features detailed post-conversation survey data capturing participants’ perceptions and feelings. Conversations were unscripted, conducted between strangers, and took place during 2020, offering a unique snapshot of discourse during a tumultuous year. CANDOR is highly pertinent to turn-taking (analysing gaps, overlaps, and turn duration with various algorithms), backchanneling (analysing frequency and potential functions using computational models), and multimodal turn-taking by integrating visual cues with spoken turns. It provides a rich, multimodal view of natural conversation. It explores the interplay between low-level, mid-level, and high-level conversational features, including psychological well-being and perceptions of conversational skill. Challenges include potential selection bias from voluntary participation and limitations in generalising findings beyond English speakers in the US context. The corpus is publicly available, promoting interdisciplinary collaboration.

2.6.5. NoXi Database

The NoXi (natural dyadic novice–expert interactions) Database [67] is a novel multimodal and multilingual corpus of screen-mediated novice-expert interactions focused on information exchange and retrieval. It contains over 25 h of recordings of dyadic interactions in seven languages (mainly English, French, and German) across 58 diverse topics. The dataset features synchronised audio (room and close-talk microphones), video, depth data, and tracking data for skeleton, facial landmarks, head pose, and action units. A key distinguishing feature is the emphasis on unexpected situations, including controlled and spontaneous conversational interruptions. The corpus includes rich continuous and discrete annotations of low-level social signals (gestures, smiles, head movements), functional descriptors (turn-taking, dialogue acts), and interaction descriptors (engagement, interest). It also provides voice activity detection, communicative state, and turn transition annotations. NoXi offers a valuable resource for studying turn-taking (with explicit annotations), backchanneling (through engagement cues and social signals), and especially multimodal turn-taking in a mediated communication setting. The inclusion of novice-expert dynamics and interruptions provides unique research opportunities. Its strengths lie in its multimodality, multilingualism, focus on a specific interaction type with a knowledge differential, and detailed annotations. Limitations include the screen-mediated setting and the particular context of information retrieval, which might influence conversational patterns. The NoXi Database is freely available through a dedicated web interface for research and non-commercial use.

Having outlined the core corpora and the functionalities they offer (such as dyadic versus multiparty interactions and audio-only versus multimodal formats), we will next analyse the interactional cues that these datasets are designed to highlight. This includes examining textual, acoustic, prosodic, and visual signals that influence turn projections and Transition-Relevance Places (TRPs) during conversations.

3. Analysing Dialogue Content: Cues for Effective Turn-Taking

Building on the foundational concepts of turn-taking discussed earlier in Section 2, this section explores the specific cues that shape conversational dynamics. Understanding turn-taking requires analysing the overall patterns of speaker transitions and considering the signals that guide them in real time. In natural dialogue, interlocutors use a range of signals, including gaze direction, gestures, prosody, and linguistic features (syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic elements), to coordinate transitions [68]. These cues provide critical information that helps listeners anticipate when to remain passive and when to respond appropriately. Although turn-final cues offer a systematic way to identify Transition-Relevant Places (TRPs), they do not capture the full complexity of turn-taking, which involves predictive mechanisms. This predictive aspect is vital in spoken dialogue systems (SDS), where agents must decide when to speak and how to generate appropriate cues for smooth interaction. Computational modelling of these cues is challenging, as it is difficult to distinguish between cues that correlate with turn transitions and those that actively trigger responses. Consequently, researchers advocate supplementing corpus-based analyses with controlled experiments to identify causal relationships better. Even cues that human listeners do not consciously notice can be valuable for SDS design, underscoring the importance of understanding and generating effective turn-taking signals. In what follows, we begin with verbal/textual signals, then move to fillers and acoustic patterns, discuss prosody, and finally turn to visual modalities, reflecting a progression from more abstract, high-level cues down to the most elemental, frame-wise information.

3.1. Text and Verbal Cues: Syntax, Semantics, and Pragmatics

Understanding verbal cues in spoken dialogue systems (SDS) requires a focus on the lexical content, what is actually said, rather than how it is delivered. This process begins by converting the speech signal into text using methods like automatic speech recognition (ASR) or manual transcription. Once the speech is transcribed, linguistic analysis can concentrate on important features such as syntax, semantics, and pragmatics, which are essential for managing turn-taking and response timing in conversations.

3.1.1. Syntactic & Pragmatic Completeness

A central idea in linguistic turn-taking is the concept of completeness, which helps determine when a speaker’s turn is ready for transition. [17] differentiate between syntactic completeness, whether an utterance forms a well-structured linguistic unit, and pragmatic completeness, which assesses whether an utterance functions as a full conversational action in context. Syntactic completeness emerges gradually during speech: an utterance is treated as complete when, in its discourse environment, it can be understood as a full clause whose predicate is either explicitly stated or straightforwardly inferred [17] (p. 143). This interpretation also permits short acknowledgements and feedback tokens (e.g., “mm-hm”) to count as complete when they perform an interactionally meaningful role. However, while syntactic completeness is necessary to mark a Transition-Relevance Place (TRP), it is not enough on its own to trigger a turn shift. Consider the following example, where syntactic completeness is marked by “/”:

- A: I booked/the tickets/

- B: Oh/for/which event/

- A: The concert/

In this exchange, “I booked” is not syntactically complete because it lacks a predicate, whereas “the concert” is complete because it conveys a full response. Pragmatic completeness, however, depends on whether the utterance accomplishes the relevant conversational action. For instance, the phrase “for which event” may be syntactically complete yet remains pragmatically incomplete if further elaboration is expected.

3.1.2. Projectability and Turn Coordination

Syntactic and pragmatic completeness contribute to projectability, which refers to how listeners anticipate when an utterance will be completed. Ref. [8] argue that turn-taking relies on predictive mechanisms, where listeners estimate the completion of a turn rather than waiting for explicit signals at the end. This predictive ability explains how speakers often begin to respond within ms (200 ms) of a turn ending, even before the previous turn is fully completed [10]. Projectability also plays a role in collaborative speech behaviours, such as choral speech and sentence completions, where listeners actively participate in constructing an utterance [42]. For example, if a speaker says, “I would like to order a …”, the listener can predict that a noun (e.g., “coffee” or “sandwich”) will follow, allowing them to delay their response appropriately. Similarly, in question–answer exchanges, the syntactic structure of a question provides clues about when and how the listener should respond, making syntax a key factor in turn regulation.

Despite the significance of syntactic and pragmatic cues, incorporating them into spoken dialogue systems (SDS) remains a formidable challenge. Early turn-taking models often relied on fixed syntactic heuristics, such as examining the final two syntactic category labels (i.e., part-of-speech tags, which classify words into grammatical categories such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives) [48,69] to determine whether an utterance is complete. For example, an utterance ending in a noun is more likely to be deemed complete, whereas one that terminates with a conjunction or determiner is less so. However, such methods fall short of capturing the inherent unpredictability of spontaneous speech, which frequently includes hesitations, self-repairs, and unfinished phrases. Recent advances in deep learning have enabled dynamic processing of linguistic structures, significantly enhancing turn-taking prediction. For instance, ref. [70] employed long short-term memory (LSTM) networks to analyse word sequences, syntactic category patterns, and phonetic features, demonstrating that lexical cues are critical for improving turn prediction accuracy. More recently, transformer-based models have further shifted the paradigm in turn-taking research. Ref. [71] introduced a transformer-based architecture that outperformed LSTM models in detecting Transition-Relevant Places (TRPs) by leveraging self-attention to capture long-range dependencies within dialogue contexts. Moreover, contemporary studies have integrated contextual embeddings from large-scale language models like BERT and GPT-3 to further refine turn-taking predictions [72,73]. These context-aware models dynamically interpret linguistic cues relative to preceding dialogue, making them more effective than traditional rule-based methods.

3.2. Fillers or Filled Pauses

Filled pauses, commonly known as fillers like “uh” and “um,” are prevalent in spontaneous speech and are typically linked to moments of hesitation or uncertainty in the speaker [74]. Research indicates that the use of these fillers may correlate with increased cognitive load, suggesting that speakers employ them more frequently when processing complex information [75]. From a turn-taking perspective, fillers serve as crucial cues for listeners, signalling that the speaker intends to maintain their turn and has not yet completed their thought [76,77]. This turn-holding function is essential for the smooth flow of conversation, as it helps prevent interruptions and ensures that speakers can convey their messages effectively. The intentionality behind the production of fillers has been a subject of debate. Ref. [77] propose that speakers use “uh” and “um” deliberately to indicate minor or significant delays in speech, respectively. Their analysis suggests that “uh” signals a brief pause, while “um” denotes a more prolonged hesitation. However, ref. [78] challenges this view, presenting acoustic data that show no significant difference in the duration of pauses following “uh” versus “um,” implying that these fillers may not have distinct meanings. Further studies have explored the linguistic status of filled pauses. Ref. [79] conducted experiments demonstrating that filled pauses can form part of more extensive linguistic representations, affecting sentence acceptability judgments and recall accuracy. This finding supports the notion that fillers function as integral components of language rather than mere disfluencies. Additionally, the prosodic features of fillers, such as intonation and duration, contribute to their communicative function. Research indicates that variations in pitch and length of filled pauses can convey different levels of speaker uncertainty or serve to manage the flow of conversation [80]. Understanding these nuances is crucial for developing spoken dialogue systems that can interpret and generate natural-sounding speech.

3.3. Speech and the Acoustic Domain

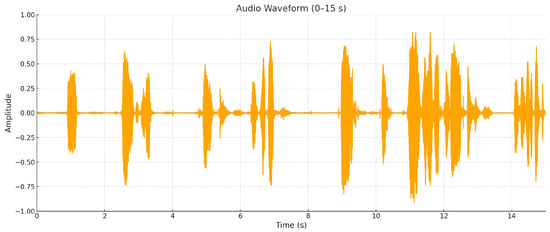

In spoken dialogue systems, the acoustic domain is fundamental, as it encompasses all the information conveyed by speech signals. Speech originates from a speaker and propagates as sound waves, pressure fluctuations in the air, captured by microphones or processed by the auditory system in human ears. These pressure variations are recorded as intensity values, sampled at specific rates (Hertz), and can be visualised as waveforms (as depicted in Figure 6).

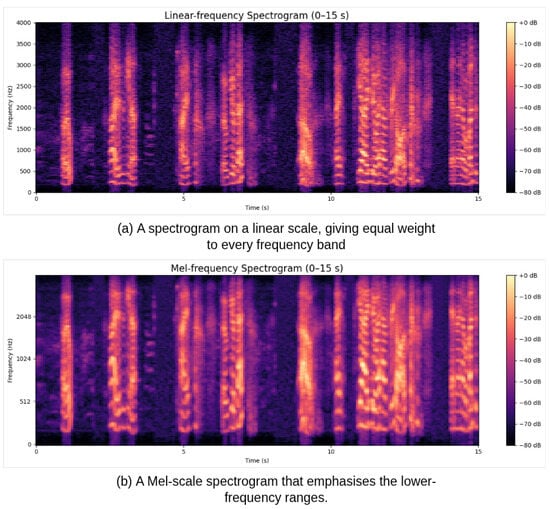

Spectrogram and Mel-Spectrogram

A spectrogram provides a two-dimensional visualisation of an audio signal, showing how energy is distributed across frequency (y-axis) over time (x-axis), as illustrated in Figure 7. It serves as a compact representation of both temporal and spectral information, making it a valuable basis for analysing acoustic cues relevant to turn-taking, such as pitch movement, intensity variation, and pauses. In practice, a spectrogram is computed by analysing short segments of the waveform to reveal frequency content over time, while a Mel-spectrogram further adjusts the frequency scale to approximate human auditory perception, emphasising the lower frequencies to which humans are most sensitive [81]. In this review, spectrograms are referenced only to contextualise acoustic feature representations used in turn-taking models, rather than to detail the underlying signal-processing procedures.

3.4. Prosody

The management of conversational dynamics and turn-taking is significantly impacted by prosody, which encompasses non-verbal aspects of speech such as intonation, loudness, and duration [33]. It conveys prominence, resolves syntactic ambiguities, expresses attitudes and emotions, signals uncertainty, and facilitates topic shifts. Research indicates that a stable level of intonation, commonly found in the midrange of the speaker’s fundamental frequency, serves as a signal to maintain the speaking turn in both English and Japanese. At the same time, pitch variations, either rising or falling, frequently suggest the intention of relinquishing the turn [48,82]. Furthermore, research indicates that speakers typically diminish their vocal intensity as they approach turn boundaries, whereas pauses within a turn typically display higher intensity [48,83]. Ref. [84] determined that prolonged pronunciation of the final syllable or the stressed syllable in a concluding clause functions as a turn-yielding signal in English, a conclusion supported by [82].

Additional insights into prosodic behaviour have arisen from studies comparing turn-taking across various languages and contexts. In Swedish, falling pitch consistently indicates turn-yielding, whereas rising pitch does not reliably associate with either maintaining or relinquishing the turn [85,86]. Moreover, analyses of American English dialogues have demonstrated that factors like final lengthening are not limited to turn endings; in fact, this lengthening is occasionally more pronounced within ongoing turns [48].

3.4.1. Intonation and Turn-Taking

Intonation is one of the most thoroughly examined prosodic elements in turn-taking. The pitch contour of an utterance, or the fundamental frequency (F0), functions as a crucial indicator of a speaker’s intention to maintain or cede the conversational turn. Investigations in various languages, such as English [48,82,84], German [87], Japanese [83], and Swedish [85], indicate that sustaining a level intonation characterised by a stable pitch within the speaker’s natural range serves as a cue for turn-holding. Conversely, falling or rising intonation is typically linked to turn-yielding, indicating that the speaker is prepared to relinquish the conversational floor [48,82,83]. Language-specific distinctions are present: in Swedish, a falling pitch signals the conclusion of a turn, whereas a rising pitch does not consistently correlate with either turn-holding or turn-shifting behaviour [85,86], suggesting that intonational patterns may not function uniformly across linguistic contexts. At the physiological level, F0 corresponds to the rate of vocal cord vibration and influences the perceived pitch of speech. This frequency corresponds to the lowest formant resonance and serves as the foundation for harmonic structures in speech production. Notably, male speakers typically exhibit a lower fundamental frequency (F0) than females, resulting in a lower overall pitch range. Despite the complexity of pitch extraction techniques, computational methods such as the Praat software toolkit [88] provide a standardised approach for analysing and extracting pitch contours, facilitating the integration of intonation-based features into spoken dialogue systems.

3.4.2. Intensity and Turn Regulation

Speech intensity, often called loudness or amplitude, is a key prosodic feature that plays a significant role in managing conversations. It reflects the acoustic energy present in speech and can be measured from spectrograms or raw waveform signals. This measurement corresponds to the waveform’s amplitude values or the combined frequency magnitudes in each frame of the spectrogram. In simpler terms, speech at a lower volume results in lower intensity, while higher volume produces greater intensity. Research by [48] has demonstrated that speakers typically lower their vocal intensity when approaching a turn boundary, making it a strong prosodic cue for signalling turn transitions. Conversely, within-turn pauses often exhibit sustained or even increased intensity, reinforcing the speaker’s intent to maintain control of the conversational floor. These findings highlight the critical role of intensity variations in shaping TRPs and influencing listener expectations regarding speaker transitions.

Similar patterns have been observed in Japanese conversational studies, where diminishing speech energy is strongly associated with turn shifts, while stable intensity levels are indicative of turn-holding behaviour [83]. These cross-linguistic findings underscore the universal role of intensity fluctuations in regulating conversational dynamics, making it an essential feature in spoken dialogue systems (SDS). Given that intensity can be continuously and reliably extracted in real time, it has the potential to enhance SDS’s predictive capabilities for identifying turn boundaries and managing speaker transitions more effectively.

3.4.3. Speech Rate and Duration as Turn-Taking Cues

The rate of speech and segment duration also serve as critical factors in managing turn coordination, influencing whether a speaker intends to maintain or relinquish the conversational floor. Research suggests that modifications in speech duration, such as extending the final syllable or stressing the terminal clause, can function as turn-yielding cues in English, a phenomenon first identified by [84] and later corroborated by [82]. However, ref. [48] offered a more complex perspective, demonstrating that final lengthening is not exclusively a turn-final phenomenon but occurs across all phrase boundaries. Notably, they found that lengthening is more pronounced in turn-medial inter-pausal units (IPUs) than in turn-final ones, suggesting that duration-based cues may not operate uniformly across all contexts. The role of speech rate and duration in turn-taking is further complicated by cross-linguistic variability. In Japanese task-oriented dialogue, ref. [83] observed that extended duration correlates with turn-holding rather than turn-yielding, contradicting earlier findings in English. Similarly, ref. [48] found that in Swedish, final lengthening does not reliably predict turn transitions, highlighting the need for a language-specific approach to modelling duration-based turn cues.

In spoken dialogue systems (SDS), accurately estimating the rate of speech and the duration of phonetic units, such as phonemes, syllables, or words, is essential to determine when to complete turns in conversation. SDS architectures typically break incoming audio into frames (e.g., 20 ms windows at 50 Hz) and identify phonetic boundaries. However, these boundaries do not always align perfectly with the acoustic minima, so robust feature extraction requires complex segmentation. Unlike human listeners, who can easily adapt to different speaking styles, SDS must normalise raw duration measures against individual speaker tempo averages to facilitate comparisons across various users. This normalisation reduces inter-speaker variation (e.g., some speakers may naturally articulate five syllables per second, while others might produce four). However, this step introduces additional computational overhead and latency. Real-time systems must therefore strike a balance between the window length required for reliable rate estimation and the need to respond quickly to cues indicating the end of a turn. Additionally, duration-based signals can exhibit language-specific patterns: English speakers often use final-syllable lengthening as a cue to yield their turn, while in Japanese, extended duration typically indicates a desire to hold the turn. In Swedish, there is minimal correlation between final lengthening and turn transitions. These variations highlight the importance of developing adaptive SDS models that learn speaker- and language-specific duration norms. Such models would ensure that speech rate and duration features meaningfully contribute to predicting turn-taking across contexts.

3.4.4. Prosody in Computational Models of Turn-Taking

Integrating prosody into spoken dialogue systems (SDS) is essential for attaining natural turn coordination. In contrast to humans, SDS face constraints in forecasting speaker transitions in real time, mainly due to processing delays and inaccuracies in automatic speech recognition (ASR) [7]. Given that prosodic features can be continuously extracted with high reliability, they may function as significant inputs for enhancing turn prediction in conversational agents.

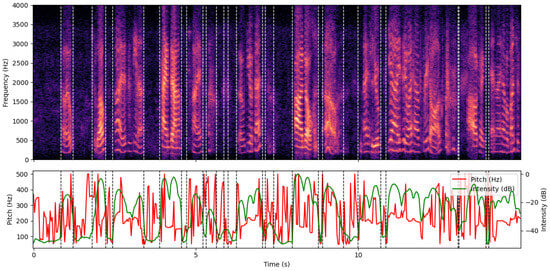

Numerous computational models have analysed the predictive efficacy of prosodic features in relation to verbal cues. Ref. [83] employed a decision tree to examine syntax–prosody interactions in Japanese task-oriented dialogue, revealing that although individual prosodic features exhibited inferior predictive capability compared to syntactic cues, the exclusion of all prosodic features markedly diminished model efficacy. Ref. [48] employed multiple logistic regression on American English dialogue and determined that textual completion was the most significant predictor of turn shifts, followed by voice quality, speaking rate, intensity, pitch level, and IPU duration. Nevertheless, upon evaluating all features, intonation did not significantly improve overall model performance, suggesting that prosody alone may be insufficient for predicting turn shifts. A visualisation of the Mel-spectrogram, along with prosodic features such as intonation and intensity, is shown in Figure 8. This figure illustrates the Mel-scale spectrogram of the first 15 s of speech, with the speaker’s F0 contour shown in red and the RMS intensity contour in green. Vertical dashed lines indicate the boundaries of individual utterance segments, clearly marking when the speaker is active. This combined view illustrates how prosodic dynamics, changes in pitch and loudness, correspond to spectral energy peaks, underscoring their significance as cues for real-time turn prediction.

3.5. Visual Cues

Non-verbal cues, such as gaze and gestures, are essential for regulating conversation turn-taking, complementing verbal signals to ensure smooth transitions between speakers. In human-human interaction, gaze direction and gesture patterns offer valuable insight into the timing and structure of conversational exchanges, serving as turn-holding and turn-yielding mechanisms. Integrating these non-verbal cues into spoken dialogue systems (SDS) and human–robot interaction (HRI) enhances the naturalness and fluidity of machine-generated communication, making them more responsive to human-like conversational behaviour.

3.5.1. Gaze

Gaze serves as both a communicative and a regulatory mechanism in turn-taking. Early studies by [68,89] demonstrated that speakers tend to avert their gaze at the beginning of a turn and redirect it toward the listener as they near a Transition-Relevance Place (TRP), signalling an imminent speaker change. Similarly, listeners are more likely to maintain eye contact while the speaker holds the floor, shifting their gaze at the point of transition to indicate readiness to take over [90,91]. Recent research has confirmed that gaze patterns vary across different types of turn-taking scenarios. When speakers yield the floor, they are more likely to direct their gaze toward the listener, reinforcing their intention to hand off the turn. Conversely, in turn-holding situations, speakers tend to sustain gaze aversion, indicating that they intend to continue speaking [54]. This distinction becomes even more critical in multi-party conversations, where gaze helps allocate turns and resolve floor competition. For example, ref. [92] found that participants who successfully claimed the floor achieved mutual gaze with the outgoing speaker before initiating speech, whereas those who failed to secure a turn exhibited misaligned gaze behaviour. Computational models of gaze behaviour have been integrated into embodied conversational agents (ECAs) to enhance the realism of system interactions. Early rule-based models relied on predefined gaze shifts at turn beginnings and completions, while more advanced machine learning approaches dynamically predict gaze behaviour based on contextual cues [93]. Transformer-based models now incorporate gaze alongside verbal and prosodic features, refining turn-taking predictions and improving the responsiveness of conversational agents [94].

3.5.2. Gesture

Gestures, particularly hand movements, act as another crucial modality for regulating conversational flow. Research indicates that speakers use gestures to reinforce, clarify, or anticipate speech content, offering an additional channel of communication beyond verbal language. Ref. [84] observed that specific hand movements, such as outward-directed gestures or static hand positioning, serve as turn-holding cues, discouraging interruptions by signalling the speaker’s intent to continue. In contrast, gesture cessation before speech completion can serve as a turn-yielding signal, facilitating smoother transitions [95].

- Hand Gestures and Predictive Turn-taking

Beyond turn-holding and yielding functions, hand gestures provide predictive information about upcoming speech content, allowing interlocutors to anticipate conversational structure [96]. Studies have found that representational gestures, which depict semantic content related to speech, frequently precede their verbal counterparts, giving listeners an early indication of meaning before it is explicitly stated. Ref. [97] analysed gesture timing relative to speech and found that gesture strokes the most meaningful segment of a gesture, typically occurring 200–600 ms before their corresponding lexical affiliate, reinforcing their predictive role in the conversation.

- Gesture Timing and Turn Coordination

The synchronisation of gesture timing with speech is strategically aligned with Transition-Relevance Places (TRPs). When speakers intend to relinquish the floor, gestures tend to terminate before the end of the speech, serving as a preliminary cue for the next speaker to take over. Conversely, when speakers intend to retain the floor, gestures may extend beyond speech, reinforcing continued engagement [95]. Gesture-speech asynchrony has also been linked to response latency in dialogue. Questions with gestures often receive faster responses, suggesting that listeners utilise gesture-based information to anticipate upcoming turns. These findings highlight the role of gestures in processing conversational structure, reducing gaps and overlaps by providing additional cues for turn coordination [97].

The multimodal nature of human communication underscores the need to integrate gaze and gesture cues into dialogue systems. While gaze direction helps regulate turn allocation and speaker transitions, gestures contribute to semantic reinforcement and predictive timing. The combination of these visual and non-verbal signals enhances turn-taking accuracy in human–robot interaction (HRI), making artificial conversational agents more natural and intuitive.

4. Computational Models for Natural Turn-Taking in Human–Robot Interaction

To achieve natural interactions between humans and robots, dialogue systems must effectively mimic human conversational behaviours, particularly in managing timing and coordination during turn-taking. This section discusses key components for realising such natural interactions, including the significance of predictive models, multimodal integration, and strategies for handling overlaps and interruptions. Highlighting recent advancements and ongoing challenges, the following subsections outline approaches and considerations that can significantly enhance the responsiveness, efficiency, and overall human-like quality of interactive dialogue systems. In the remainder of this review, we focus on recent computational approaches to turn-taking in spoken dialogue systems and human–robot interaction. Unless otherwise noted, we include work that (i) was published between late 2021 to the time of publication, and (ii) proposes or evaluates models that function in spoken interactions for tasks such as detecting or predicting the end of a turn, timing and selecting types of backchannels, managing real-time system behaviour, or overseeing multi-party conversations. Earlier models will only be referenced when they serve as direct precursors to these recent neural, self-supervised, or multimodal approaches.

4.1. Turn-Taking Detection and Prediction Models

The arguably most studied aspect of turn-taking in conversational systems is determining when the user’s turn ends, and the system can begin speaking (i.e., the detection of TRPs). A related aspect is determining when the system should provide a backchannel (i.e., as discussed in an earlier section). This section will examine recent efforts to develop models of turn-taking, highlighting the methodologies, key findings, and datasets used in these studies. Since a review article has already addressed earlier work in this area, this review will focus on more recent developments. Significant progress has been made in the field in recent years, particularly with the introduction of large language models. This serves as the motivation for this review.

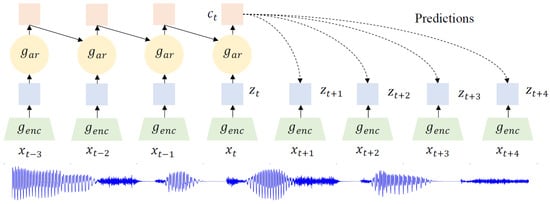

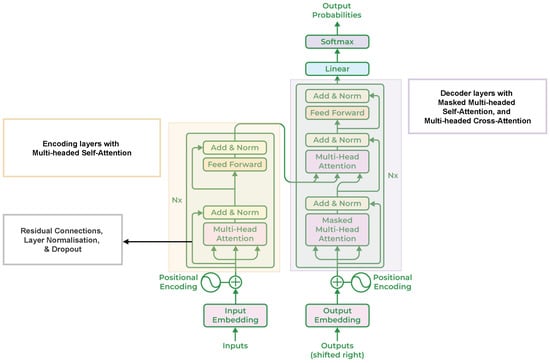

There are three broad categories of turn-taking models commonly discussed in the literature. The first, and simplest, is the silence-based approach, in which a Transition-Relevance Place (TRP) is assumed once a pause exceeds a predetermined duration. This method is frequently adopted as a baseline for comparing more advanced models. A second family of approaches relies on Inter-Pausal Units (IPUs), typically segmented using an external Voice Activity Detection (VAD) system. Here, the task is to determine whether the end of an IPU corresponds to a TRP or whether the current speaker is likely to continue. IPU-driven methods have been widely studied across different conversational settings and model architectures [56,69,72,98,99,100,101,102]. These systems generally extract a feature set—such as lexical, syntactic, prosodic, and contextual cues—from the full IPU or its final portion, and then classify the boundary as a hold or a shift. Early work predominantly used decision-tree or random-forest-based classifiers [98,99], as well as SVMs [48,56,69,103], while more recent research has favoured modern machine-learning models [72,100,101,102,104,105].