Optimization of Compressor Preheating to Increase Efficiency, Comfort, and Lifespan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Compressor Preheating

1.2. Preheating Approaches

1.3. Preheating Problems

1.4. Contribution

- Development of an approach to define the modulation frequency that balances efficiency optimization and the mitigation of audible noise;

- Development of a technique to decrease the preheating time, thus increasing customers’ comfort and efficiency of preheating;

- Development of an algorithm that makes the load on the inverter and motor phases more even and increases the lifespan of the device;

- Experimental verification of the developed algorithms and evaluation of their contributions to the resulting efficiency.

2. Theoretical Basis

2.1. Construction of Scroll Compressor

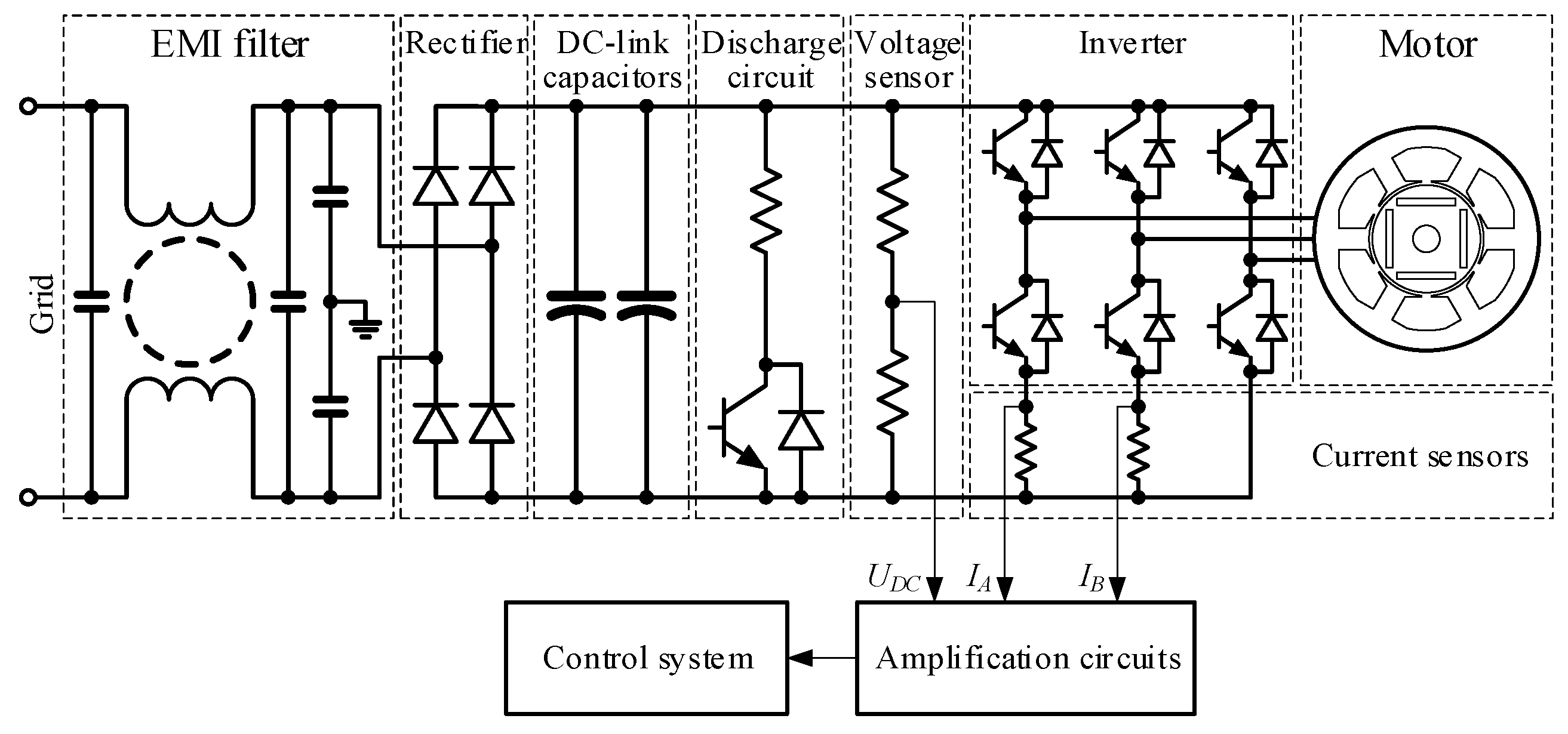

2.2. Structure of Motor Drive

2.3. Control Scheme

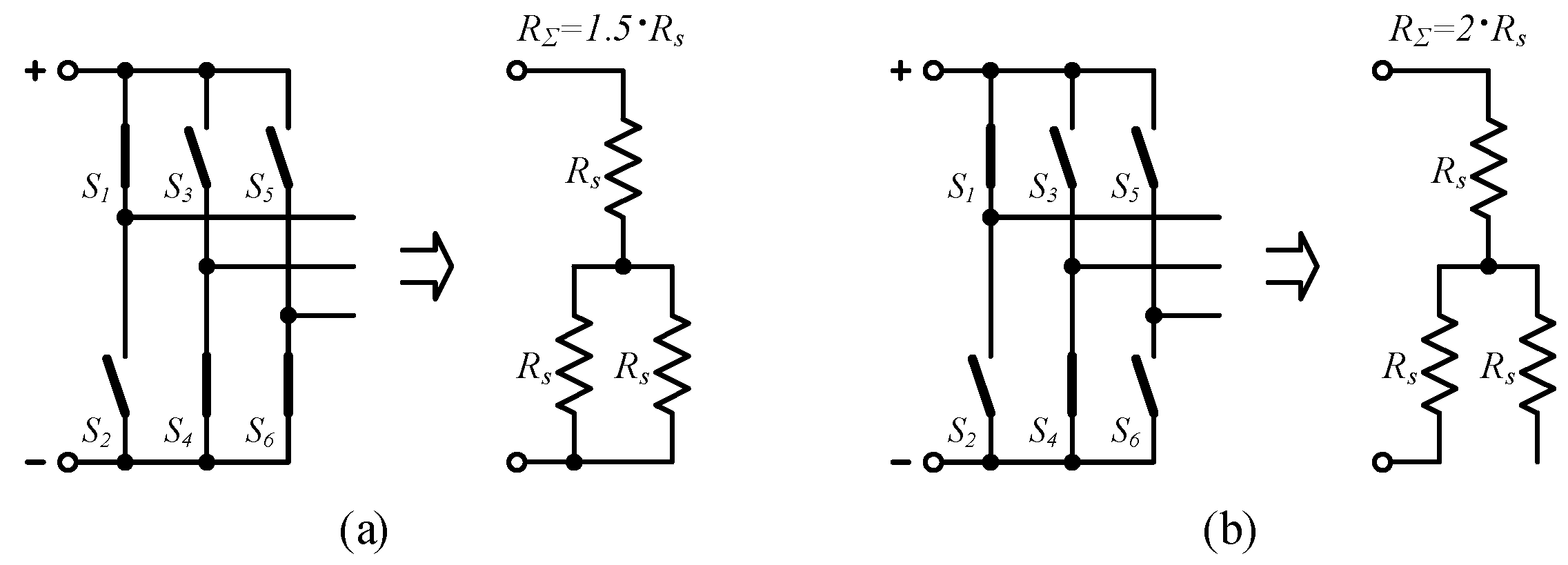

2.4. Preheating by Injection of DC Current

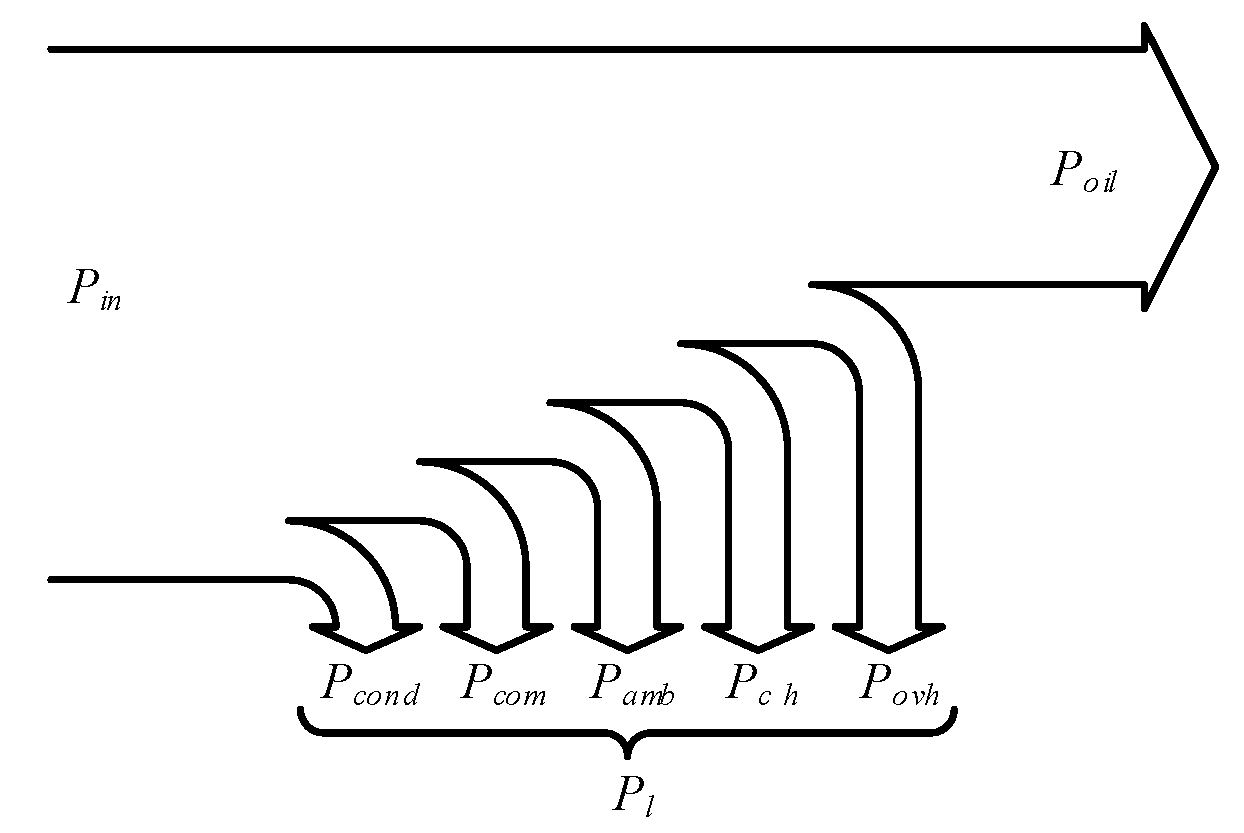

2.5. Parameters of Preheating

3. Proposed Improvements

3.1. Optimization Directions

3.2. Decrease in Preheating Time

3.3. Optimization of Modulation Frequency

3.4. Enhancing the Lifespan

4. Materials and Methods

5. Experimental Results

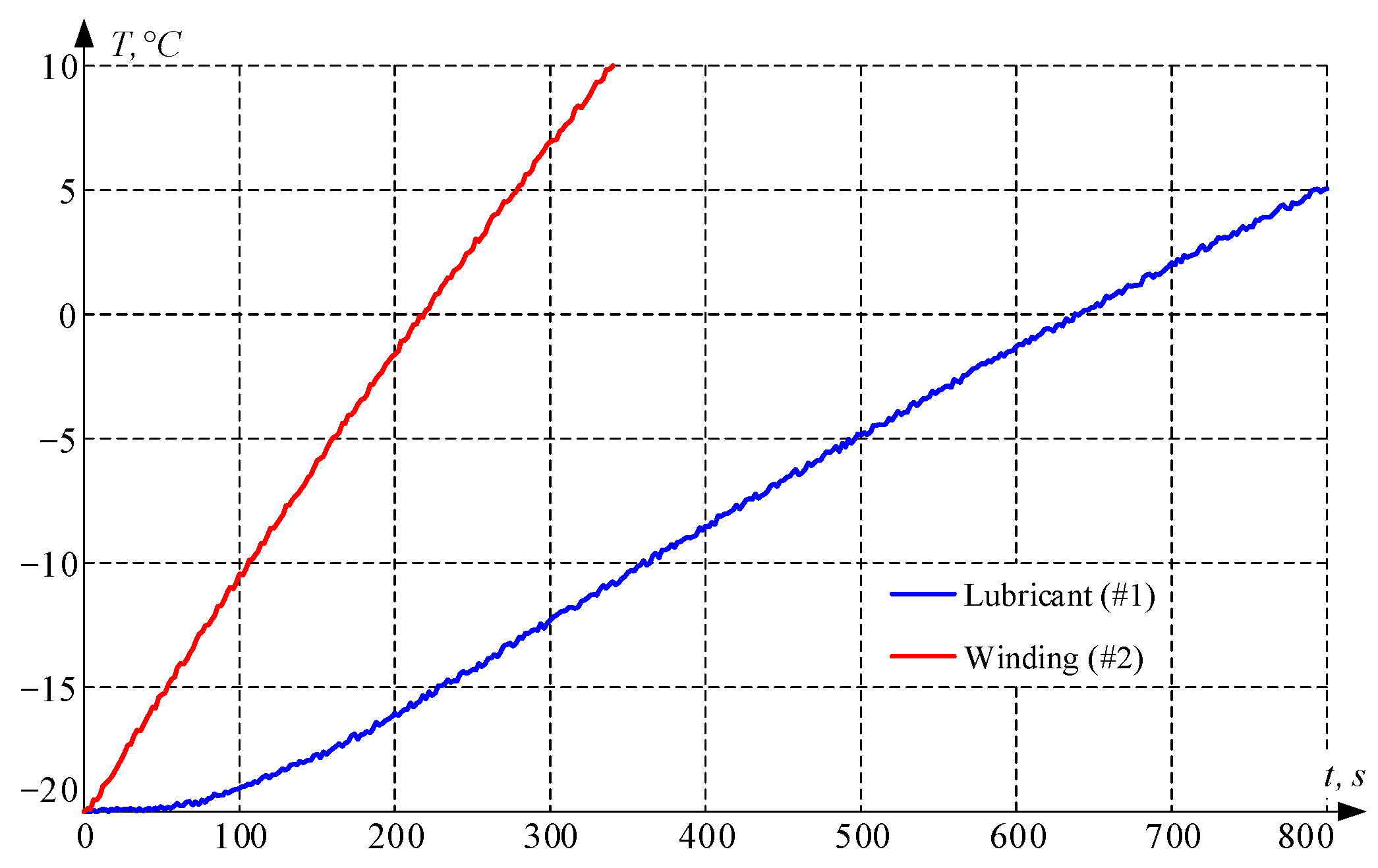

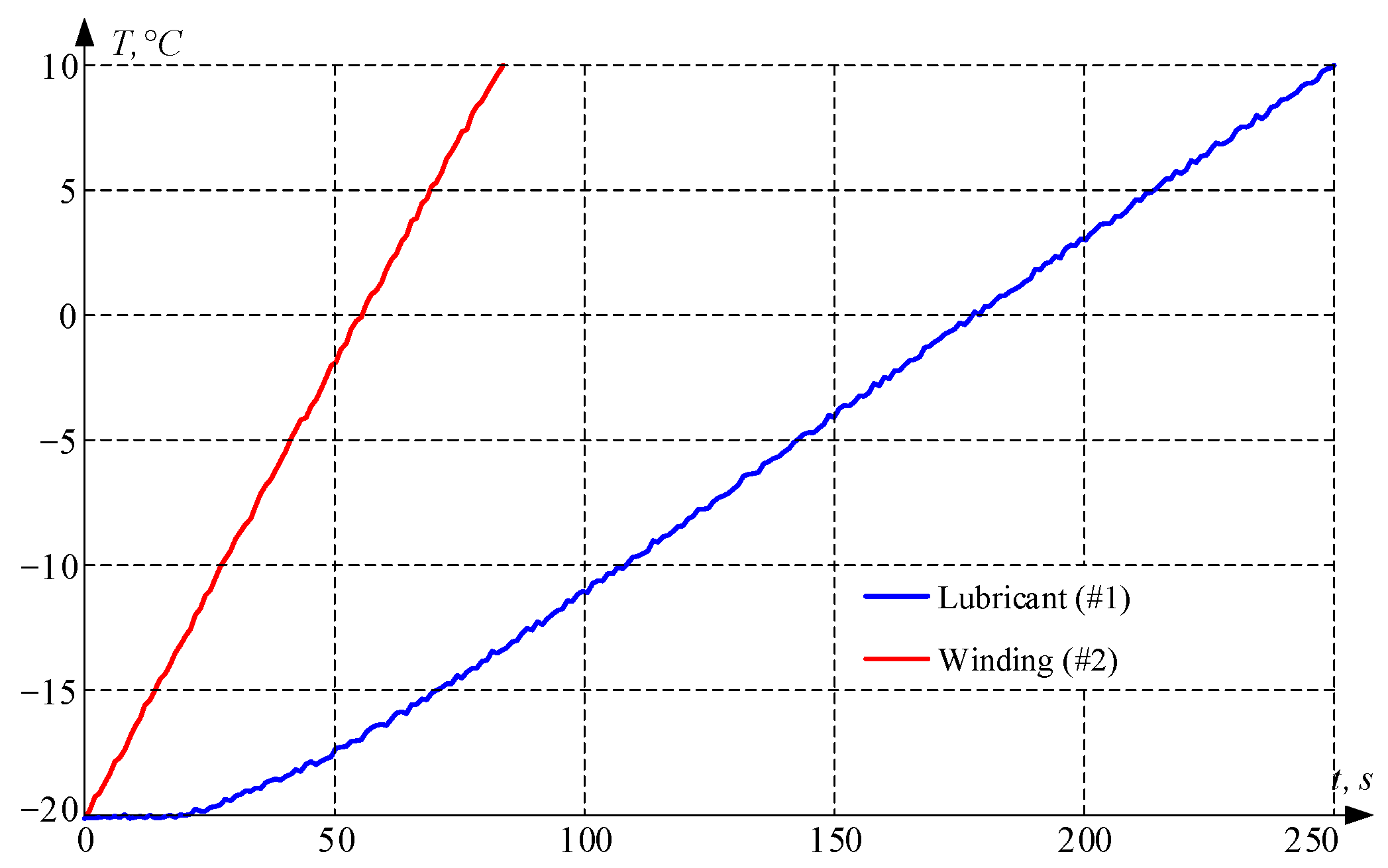

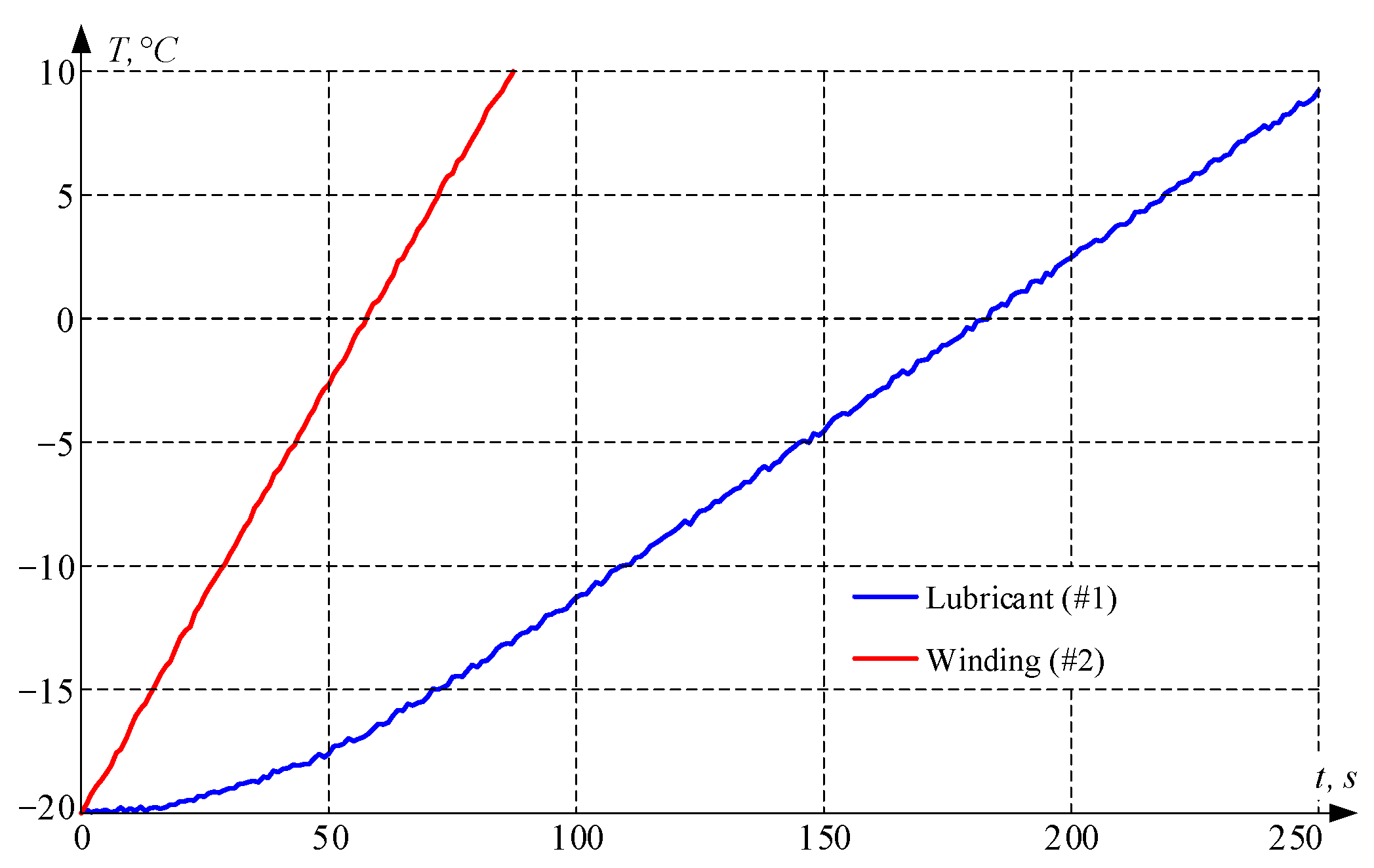

5.1. Evaluation of Preheating Before Optimization

5.2. Optimization of Preheating Time

5.3. Optimization of Modulation Frequency

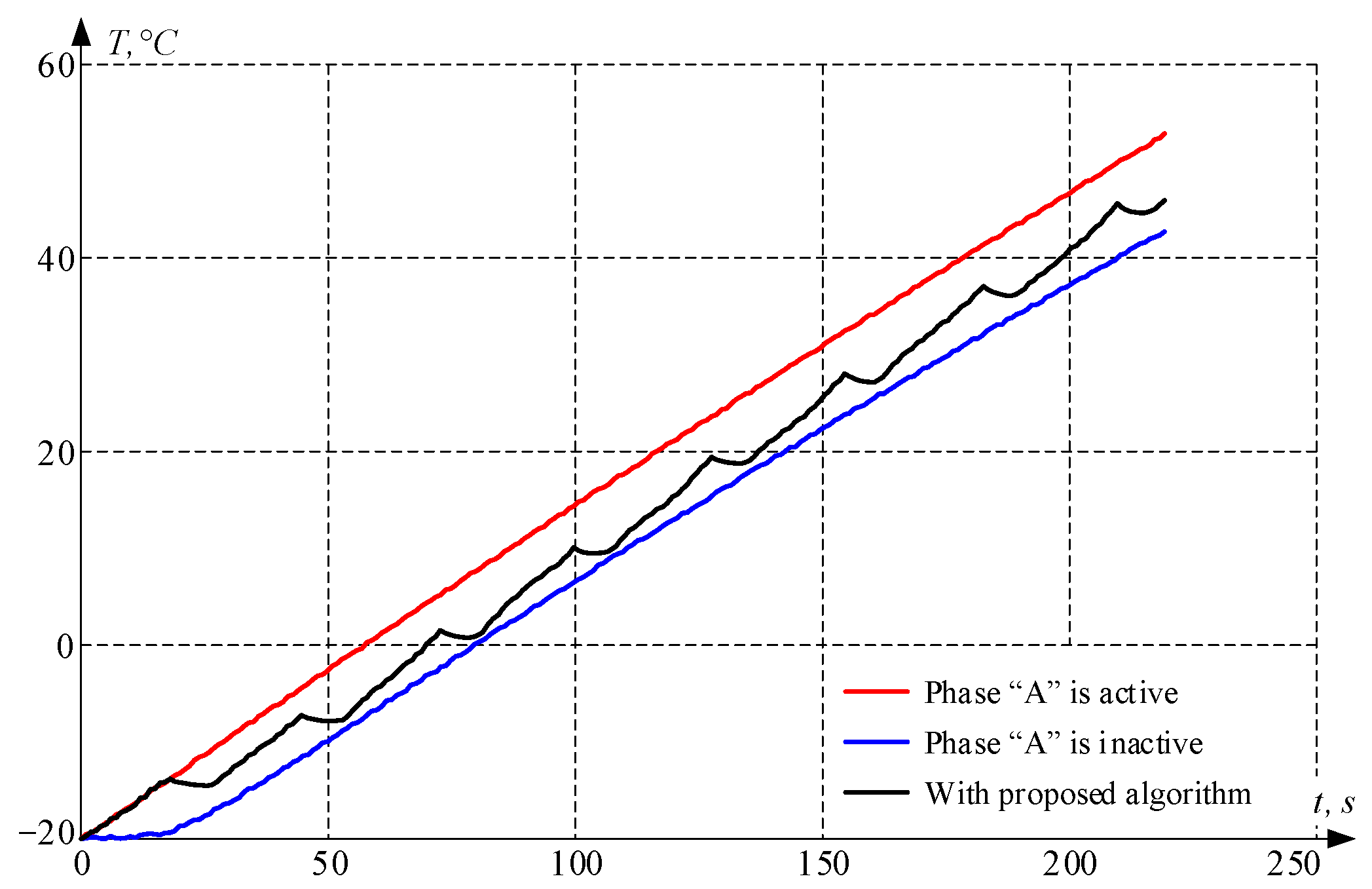

5.4. Improvement in Load Distribution

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Setz, B.; Graef, S.; Ivanova, D.; Tiessen, A.; Aiello, M. A comparison of open-source home automation systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 167332–167352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidova, G.; Usoltchev, A.; Poliakov, N.; Lukichev, D.; Lukin, A.; Anuchin, A. Optimal Selection of High-Frequency Solid-State Transformer Topology for Dual Active Bridge Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE 10th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, Chengdu, China, 17–20 May 2024; pp. 3851–3856. [Google Scholar]

- Household Appliances—Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/household-appliances/worldwide (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Garrido-Zafra, J.; Gil-de-Castro, A.R.; Fernandez, R.S.; Linan-Reyes, M.; Garcia-Torres, F.; Moreno-Munoz, A. IoT cloud-based power quality extended functionality for grid-interactive appliance controllers. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 3909–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lee, K.-W.; Kwak, S. Dual motor drive for HVAC applications based on a multifunctional bidirectional energy conversion system. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2015, 30, 1556–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutar, P.; Sarkar, S.A.; Tagare, A.; Pawar, A. A Review on IoT-Enabled Smart Homes Using AI. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies, Himachal Pradesh, India, 24–28 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Plumed, E.; Lope, I.; Acero, J.; Burdío, J.M. Domestic induction heating system with standard primary inductor for reduced-size and high distance cookware. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 7562–7571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-Y. Establishing a cybersecurity home monitoring system for the elderly. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 4838–4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.D.; Freijedo, F.D.; Wijekoon, T.; Liserre, M. A multiport partial power converter for smart home applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 8824–8833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevoloso, C.; Foti, S.; Scaglione, G.; Di Tommaso, A.O.; De Caro, S.; Testa, A.; Miceli, R. On the Inadequacy of IEC 60034-2-3 and IEC 60034-30-2 Standards for Power Losses, Efficiency and Energy Class Evaluation in PWM Multilevel Inverter-Driven PMSM. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2025, 6, 962–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goman, V.; Oshurbekov, S.; Kazakbaev, V.; Prakht, V.; Dmitrievskii, V. Energy Efficiency Analysis of Fixed-Speed Pump Drives with Various Types of Motors. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Dianov, A.; Demidova, G.; Prakht, V.; Wang, Y.; Han, S. Model predictive torque control of six-phase switched reluctance motors based on improved voltage vector strategy. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 7650–7661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, M.R.; Carichner, D. Motor conversion for reduced energy consumption: Compressor applications use more energy than applications with newer technologies. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag. 2015, 21, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, J.; Hoyt, W.; Zwanziger, P.; Finley, B. Motor and drive-system efficiency regulations: Review of regulations in the United States and Europe. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag. 2017, 23, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-W.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, B.T.; Kwon, B.I. A Novel Starting Method of the Surface Permanent-Magnet BLDC Motors Without Position Sensor for Reciprocating Compressor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2008, 44, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, A.; Muetze, A. A Research Overview on Household Refrigerator Hermetic Reciprocating Compressor Drives. In Proceedings of the IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 20–24 October 2024; pp. 6175–6180. [Google Scholar]

- Dianov, A. Stoppage noise reduction of reciprocating compressors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 4376–4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hui, H. Model Predictive Control-Based Active/Reactive Power Regulation of Inverter Air Conditioners for Improving Voltage Quality of Distribution Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Zhao, N.; Gao, R.; Wang, G.; Zhang, G.; Xu, D. Torque ripple compensation with anti-overvoltage for electrolytic capacitorless PMSM compressor drives. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 6148–6159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, H.; Ding, Y.; Chen, T.; Rahman, S.; Song, Y. Dynamic and stability analysis of the power system with the control loop of inverter air conditioners. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 2725–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusche, S. Energy Optimised Control of the Dehumidification Process in HVAC Systems. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies, Prague, Czech Republic, 29 June–2 July 2020; pp. 994–999. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.-W.; Park, S.; Jeong, S. A Seamless Transition Control of Sensorless PMSM Compressor Drives for Improving Efficiency Based on a Dual-Mode Operation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2015, 30, 1446–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gong, C.; Chen, F.; Lv, L. Power Optimal Matching and Humidity Intelligent Control of Ring Main Unit Dehumidification System. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 491–496. [Google Scholar]

- Batek, A.; Aliprantis, D. Improving Home Appliance Energy Use Scheduling: Insights from a Remodeled, Energy Efficient Home. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 6–9 September 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, R.; Sun, W.; Xiang, J. Ensemble difference mode decomposition based on transmission path elimination technology for rotating machinery fault diagnosis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2024, 212, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, D.; Liu, E.; Zhang, B.; Zio, E.; Yang, T.; Xiang, J. Threshold-varying assessment for prognostics and health management. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidova, G.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Lukichev, D.; Anuchin, A. Reviewing Fault Diagnosis Methods in Electric Drives: Power Subsystem and Electrical Machine. In Proceedings of the IEEE 24th International Conference of Young Professionals in Electron Devices and Materials, Novosibirsk, Russia, 29 June–3 July 2023; pp. 1680–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.N.; Kütt, L.; Lehtonen, M.; Millar, R.J.; Püvi, V.; Rassõlkin, A.; Demidova, G.L. Travel activity based stochastic modelling of load and charging state of electric vehicles. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fang, B.; Dianov, A.; Xiang, J. Numerical model-aided intelligent diagnosis method to detect faults in induction motors. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 32194–32208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, H.P.; Bannister, K.E. Practical Lubrication for Industrial Facilities, Practical Lubrication for Industrial Facilities; River Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L.; Qu, M.; Ma, Z.; Xiang, J.; Tan, D.; Xu, F. Recursive variational mode transform for weak fault feature recognition in rotor-bearing systems. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 26398–26411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, S.G. Compressor Lubrication-The Key to Performance. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, London, UK, 7–9 September 2015; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2015; Volume 90, p. 12001. [Google Scholar]

- Jastrzebski, R.P.; Kepsu, D.; Putkonen, A.; Martikainen, I.; Zhuravlev, A.; Madanzadeh, S. Competitive Technology Analysis of a Double Stage Kinetic Compressor for 0.5 MW Heat Pumps for Industrial and Residential Heating. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference, Hartford, CT, USA, 17–20 May 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, R.; Maynus, R. Crucial for Rotating Machines: Types and Properties of Lubricants and Proper Lubrication Methods. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag. 2016, 22, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokarakonda, S.; Treeck, C.; Rawal, R.; Thomas, S. Energy performance of room air-conditioners and ceiling fans in mixed-mode buildings. Energies 2023, 16, 6807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumeru, K.; Pramudantoro, T.P.; Setyawan, A.; Muliawan, R.; Tohir, T.; Sukri, T.F. Effect of compressor-discharge-cooler heat-exchanger length using condensate water on the performance of a split-type air conditioner using R32 as working fluid. Energies 2022, 15, 8024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, K.W.; Lee, J.H. Sensorless Vector Controlled Drive for Reciprocating Compressor. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power Electronics Specialists Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 17–21 June 2007; pp. 580–586. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry, R.; Maynus, R. Lubrication—Crucial for Rotating Machines. In Proceedings of the Petroleum and Chemical Industry Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 24–26 September 2012; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Song, Q.; Chen, Q. Friction-excited oscillation of air conditioner rotary compressors: Measurements and numerical simulations. Lubricants 2022, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Pang, L.; Liu, M.; Yu, S.; Mao, X. Control strategy for helicopter thermal management system based on liquid cooling and vapor compression refrigeration. Energies 2020, 13, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Xiong, S.; Wen, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y. Experimental study on R290 performance of an integrated thermal management system for electric vehicle. Energies 2025, 18, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, J.B.; Glogowski, M.J. Additives contents in PAG and synthetic motor base oils and their effect on electrostatic phenomena in a rotating shaft-oil-lip seal system. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2013, 20, 1561–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wu, M.; Lei, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. An improved model predictive current control for PMSM drives based on current track circle. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 3782–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Singh Dhupia, J.; Tang, L.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J. An enhanced partial transfer fault diagnosis network aided by dual-force boundary refinement and inverse-forward adaptive alignment. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 3821–3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Yoon, M.S.; Al-Qahtani, T.; Nam, Y. Feasibility study on variable-speed air conditioner under hot climate based on real-scale experiment and energy simulation. Energies 2019, 12, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrievskii, V.; Prakht, V.; Kazakbaev, V.; Anuchin, A. Comparison of interior permanent magnet and synchronous homopolar motors for a mining dump truck traction drive operated in wide constant power speed range. Mathematics 2022, 10, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lou, F.; Qi, X.; Shen, Y. Enhancing heating performance of low-temperature air source heat pumps using compressor casing thermal storage. Energies 2020, 13, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, T.; Yao, M.; Lei, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. Improved finite-control-set model predictive control with virtual vectors for PMSHM drives. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 1885–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, M.; Kong, D. Overall Energy Efficiency of Lubricant-Injected Rotary Screw Compressors and Aftercoolers. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference, Wuhan, China, 27–31 March 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Valenti, G.; Murgia, S.; Costanzo, I.; Scarnera, M.; Battistella, F. Experimental determination of the performances during the cold start-up of an air compressor unit for electric and electrified heavy-duty vehicles. Energies 2021, 14, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, G.; Murgia, S.; Costanzo, I.; Ravidà, A.; Piscopiello, G.P. Experimental Investigation on the Extreme Cold Start-Up of an Air Compressor for Electric Heavy Vehicles. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, London, UK, 9–11 September 2019; Volume 604, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.; Warsinger, D. Energy savings of retrofitting residential buildings with variable air volume systems across different climates. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 30, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, H.; Long, T.; Xu, Y.; Bi, R.; Hu, B.; Zhang, G.; Wang, G. A Novel Modulation Algorithm for Efficient Heating of Air Conditioning Compressor. In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th International Electrical and Energy Conference, Harbin, China, 10–12 May 2024; pp. 3451–3456. [Google Scholar]

- Amirpour, S.; Soltanipour, S.; Thiringer, T.; Katta, P. Adaptive Determination of Optimum Switching Frequency in SiC-PWM-Based Motor Drives: A Speed-Dependent Core Loss Correction Approach. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2025, 6, 883–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A. Compressor Acoustic Profile Improvement in Preheating Mode. In Proceedings of the XIX International Scientific Technical Conference Alternating Current Electric Drives (ACED), Ekaterinburg, Russia, 23–25 May 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, A.; Monir, S.; Day, R.J.; Vagapov, Y.; Dianov, A. A Test Rig for Thermal Analysis of Heat Sinks for Power Electronic Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE East-West Design & Test Symposium, Batumi, Georgia, 22–25 September 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Dianov, A.; Kang, J.-W. Decreasing noise pollution of the automotive compressor in preheating mode. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 3093–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.; Yoon, S.W.; Park, S.; Kim, M.; Lim, J.; Jeon, J.; Han, H. Multiphysics Simulation Analysis and Design of Integrated Inverter Power Module for Electric Compressor Used in 48-V Mild Hybrid Vehicles. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Topics Power Electron. 2019, 7, 1668–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Wang, S.; Lee, K. 3-D Optimal Design of Induction Motor Used in High-Pressure Scroll Compressor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45, 2076–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, T.; Bogh, D.; Krukowski, J. Synchronous motors to compressors: Properties and behavior of reciprocating types of driven mechanical equipment. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag. 2014, 20, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.K.; Lee, B.C.; Kiem, M.K.; Kim, S.C. Structure Design of a Scroll Compressor Using CAE Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Compressor Engineering Conference, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 17–20 July 2006; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dianov, A. A Novel Phase Loss Detection Method for Low-Cost Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 6660–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidova, G.; Privalov, D.; Semenov, D.; Lukichev, D.; Liu, Z.; Anuchin, A. Fault Detection in Electric Drives Based on LSTM Autoencoder Model Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE 25th International Conference of Young Professionals in Electron Devices and Materials, Altai, Russia, 28 June–2 July 2024; pp. 1670–1675. [Google Scholar]

- Dianov, A.; Anuchin, A. Phase loss detection using voltage signals and motor models: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 26488–26502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ding, J.; Sun, X.; Lei, G.; Dianov, A.; Demidova, G.; Prakht, V. Compensation control of PMSMs based on a high-order sliding mode observer with inertia identification. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 5084–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassõlkin, A.; Rjabtšikov, V.; Kuts, V.; Vaimann, T.; Kallaste, A.; Asad, B.; Partyshev, A. Interface Development for Digital Twin of an Electric Motor Based on Empirical Performance Model. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 15635–15643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukin, A.; Demidova, G.; Rassõlkin, A.; Lukichev, D.; Vaimann, T.; Anuchin, A. Small Magnus Wind Turbine: Modeling Approaches. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Ding, D.; Li, B.; Wang, G.; Xu, D. PR Internal Mode Extended State Observer-Based Iterative Learning Control for Thrust Ripple Suppression of PMLSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 10095–10105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ding, D.; Wang, G.; Ding, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, D. Adaptive Step-Size Predictive PLL Based Rotor Position Estimation Method for Sensorless IPMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 6136–6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnikov, D.; Chub, A.; Kosenko, R.; Sidorov, V.; Lindvest, A. Implementation of global maximum power point tracking in photovoltaic microconverters: A survey of challenges and opportunities. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 2259–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, X.; Su, Z.; Zha, X.; Dianov, A.; Prakht, V.; Demidova, G.; Ma, J. Model-free predictive control for harmonic suppression of PMSMs based on adaptive resonant controller. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 40, 3104–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Li, W.; Zhao, M.; Shi, J. SiC MOSFETs: The inevitable trend for 800V electric vehicle air conditioning compressors. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 2620–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adsani, A.S.; AlSharidah, M.E.; Beik, O. BLDC motor drives: A single hall sensor method and a 160° commutation strategy. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2021, 36, 2025–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhou, H.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Xu, D. Current sensor fault-tolerant control for encoderless IPMSM drives based on current space vector error reconstruction. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 8, 3658–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Xiao, D.; Li, L.; Xu, D. Pseudorandom-Frequency Sinusoidal Injection for Position Sensorless IPMSM Drives Considering Sample and Hold Effect. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 9929–9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuchin, A.; Gulyaeva, M.; Zharkov, A.; Lashkevich, M.; Hao, C.; Dianov, A. Increasing Current Loop Performance Using Variable Accuracy Feedback for GaN Inverters. In Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on Power Electronics (Ee), Novi Sad, Serbia, 27–30 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, A.; Niedermayer, J.M.; Akinsolu, M.O.; Vagapov, Y.; Monir, S.; Dianov, A. Numerical Optimisation of Air-Cooled Heat Sink Geometry to Improve Temperature Gradient of Power Semiconductor Modules. In Proceedings of the XV International Symposium on Industrial Electronics and Applications, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 6–8 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Li, T.; Tian, X.; Zhu, J. Fault-tolerant operation of a six-phase permanent magnet synchronous hub motor based on model predictive current control with virtual voltage vectors. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A.; Sun, X.; Kang, J.-W.; Demidova, G.; Prakht, V.; Tarlavin, N.; Xiang, J. Recommendations and typical errors on usage of wirewound resistors in design of power converters. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2025, 6, 669–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.T.; Yoon, T.H. Sensorless IPMSM based drive for reciprocating compressor. In Proceedings of the 13th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, Poznan, Poland, 1–3 September 2008; pp. 1002–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Fang, J.; Han, B.; Zheng, S. Adaptive compensation method for high-speed surface PMSM sensorless drives of EMF-based position estimation error. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 1438–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A. Instant Closing of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Control Systems at Open-Loop Start. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A.; Anuchin, A. Design of constraints for seeking maximum torque per ampere techniques in an interior permanent magnet synchronous motor control. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A. Improved field-weakening control of PM motors for home appliances excluding speed loop windup. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A. Optimized Field-Weakening Strategy for Control of PM Synchronous Motors. In Proceedings of the 29th International Workshop on Electric Drives: Advances in Power Electronics for Electric Drives, Moscow, Russia, 26–29 January 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 226:2003; Acoustics—Normal Equal-Loudness-Level Contours. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Brown, I.P.; Critchley, M.W.; Yin, J.; Memory, S.B.; Sizov, G.Y.; Elbel, S.W. Design and evaluation of interior permanent-magnet compressor motors for commercial transcritical CO2 (R-744) heat pump water heaters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 51, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakht, V.; Ibrahim, M.N.; Kazakbaev, V. Energy Efficiency Improvement of Electric Machines without Rare-Earth Magnets. Energies 2023, 16, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahns, T.M.; Sarlioglu, B. The incredible shrinking motor drive: Accelerating the transition to integrated motor drives. IEEE Power Electron. Mag. 2020, 7, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolam, R.C.; Roque, J.P.C.; Vagapov, Y.; Dianov, A. Prototype testing of rim driven fan technology for high-speed aircraft electrical propulsion. In Proceedings of the 59th International Universities Power Engineering Conference, Cardiff, UK, 2–6 September 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Anuchin, A.; Shpak, D.; Kotelnikova, A.; Dmitriev, A.; Bogdanov, A.; Demidova, G. Encoderless Rotor Position Estimation of a Switched Reluctance Drive Operated Under Model Predictive Control. In Proceedings of the IEEE 61th International Scientific Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering of Riga Technical University, Riga, Latvia, 5–7 November 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Cai, F.; Yang, Z.; Tian, X. Finite position control of interior permanent magnet synchronous motors at low speed. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 7729–7738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardell, J.D.; Kumar, P. Adjustable-Speed Drive Motor Protection Applications and Issues. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2014, 50, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lörsch, A.; Schmilinsky, M.; Vagapov, Y.; Bolam, R.C.; Dianov, A. Practical Learning of DSP-Based Motor Control for Engineering Students. In Proceedings of the 59th International Universities Power Engineering Conference, Cardiff, UK, 2–6 September 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, M.; Rassõlkin, A.; Vaimann, T.; Kallaste, A. Overview on Digital Twin for Autonomous Electrical Vehicles Propulsion Drive System. Sustainability 2022, 14, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, A.; Anuchin, A. Fast Square Root Calculation for Control Systems of Power Electronics. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems, Hamamatsu, Japan, 24–27 November 2020; pp. 438–443. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Symbol | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compressor type | - | - | Scroll |

| Power | Pc | W | 3600 |

| Supply voltage | Us | V/Hz | 220/60 |

| Life time | TL | cycles | 230,000 |

| Operating ambient temperature | Ta | °C | −20~55 |

| Lubricant type | - | - | POE |

| Oil charge @ 20 °C | Voil | cc | 1250 |

| Oil temperature at start | Ts min | °C | 5 |

| Oil density @ 20 °C | ρoil | kg/m3 | 940 |

| Oil heat capacity | coil | J/(kg∙K) | 1800 |

| Parameters | Symbol | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pole pairs number | p | - | 3 |

| Rated power | Pm | W | 3600 |

| Rated current | Ir | A | 18 |

| Maximum current * | Imax | A | 30 |

| Maximum winding temperature | Tw max | °C | 115 |

| Stator resistance | Rs | Ω | 0.46 |

| d-axis inductance | Ld | mH | 4.9 |

| q-axis inductance | Lq | mH | 6.4 |

| Rotor flux linkage | ψm | V·s/rad | 0.123 |

| Frequency, kHz | 1.5 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 15 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation | |||||||||

| Very annoying | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Annoying | 1 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hearable | 0 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | |

| Not hearable | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 10 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dianov, A. Optimization of Compressor Preheating to Increase Efficiency, Comfort, and Lifespan. Technologies 2025, 13, 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120590

Dianov A. Optimization of Compressor Preheating to Increase Efficiency, Comfort, and Lifespan. Technologies. 2025; 13(12):590. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120590

Chicago/Turabian StyleDianov, Anton. 2025. "Optimization of Compressor Preheating to Increase Efficiency, Comfort, and Lifespan" Technologies 13, no. 12: 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120590

APA StyleDianov, A. (2025). Optimization of Compressor Preheating to Increase Efficiency, Comfort, and Lifespan. Technologies, 13(12), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies13120590