Abstract

This study aims to investigate the impact of green finance on corporate sector investments and their associated environmental outcomes. The authors collected cross-sectional survey data with a sample of four hundred firms selected from the five green-relevant industries in an emerging economy. The results indicate that, over the last three years, seventy percent of firms have accessed at least one green instrument. Overall, the firms under study indicate that PKR 3.4 million is being allocated to green finance, and PKR 2.7 million is spent on CAPEX. However, each million PKR is associated with a ten percent capital expenditure, which exhibits the highest adoption of the renewable energy sector, while the manufacturing sector has the lowest adoption. Regression results depict that Greenhouse gas reduction is only achievable if expenditure on R&D is ensured for environmental gains. This study indicates a declining incremental impact when green finance exceeds PKR 5.00 million, suggesting that firms’ limitations in utilizing the additional amount may be a factor. Financially constrained firms achieve stronger environmental goals, confirming that strict criteria to finance projects show more responsibility and discipline in executing projects. However, small- and medium-sized firms are confronted with barriers, such as lack of information and transaction costs. The findings of this study highlight the need for a multi-layered regulatory framework, innovation-driven incentives, and fintech integration to fully realize the potential of green finance. The outcome enables financial institutions, sustainability practitioners, and regulators to connect financial markets, national climate, and development goals.

1. Introduction

The escalating crisis of the climate change emergency, growing ecological degradation, and limited resources have catalyzed a global response to integrate financial systems with environmental goals. Green finance is playing a significant role in aligning investment patterns with global environmental objectives. In order to channel the finances of the project to attain environmental outcomes, there are market-based solutions in the form of green financial instruments like green bonds, loans, and finances for sustainable infrastructure. Green finance is gaining importance not only due to widespread discussion but also because there are now green finance rules, taxonomies, and policies in place worldwide. Studies in the field demonstrate that green finance initiatives play a significant role in influencing public and company investment plans. Significantly, Green Finance Reform and Innovation Pilot Zones in China have led to a rise in green investment among corporations by modifying how firms can access external financial resources, increasing environmental awareness among them, and placing emphasis from regulators on their activities (W. Zhang et al., 2024). According to panel data, green finance and investments in renewable energy are linked in G-20 countries. Significantly, these approaches enhance environmental performance and accelerate the transition to eco-friendly economic growth in financial markets that are not yet well-established (Ma et al., 2023).

The reforms help support new green initiatives and contribute to a noticeable decrease in carbon emissions (Cui et al., 2024). Another study also indicates that the positive impact of green finance on company environmental performance is made greater by strong rules and challenges from financial institutions (Javeed et al., 2024).

The authors, as part of their study, suggest that internal funds improve companies’ green investment strategies. At the same time, elevated levels of external leverage reduce their interest in green initiatives and environmental benefits (Bouchmel et al., 2024). Digital finance is playing a significant role in helping green finance grow. With new technological developments, people can now raise capital faster, access clearer information, and ensure greater transparency in green investments. Furthermore, a China-based study demonstrates that digital finance facilitates corporate green investment by enhancing capital movement among units within companies. It, in turn, intensifies the competition among the companies, compelling them to gain more internal control to achieve environmental outcomes. The response of different enterprises towards green finance initiatives varies depending upon their ownership structure. The state-owned enterprises are more responsive to digital green finance initiatives compared to their non-state-owned counterparts (Ding et al., 2022; Desai & Patel, 2025). Rigorous reporting and accountability builds the investors’ confidence in green investments (Martin, 2023).

The role of green finance is globally recognized for achieving environmentally sustainable goals. Al-Afeef et al. (2024) in their research study argue that there is convincing evidence from Jordan that efforts in green finance led to better long-term sustainability outcomes, characterized by reduced emissions and an enhanced environment. Evidence from regional studies in Asia and the Middle East underscores the importance of strengthening partnerships between private and public sectors, channeling investments into renewable sectors, and enhancing targeted green research and development initiatives (S. Khan et al., 2022).

2. Literature Review

In the academic field, the role of green finance can never be ignored. The focus of green finance is to align capital with environmental objectives. However, the theoretical foundations and empirical findings remain fragmented across various regions, sectors, and methodological paradigms. The purpose of this study is to clarify the role of green finance in light of environmental goals. The extensive literature has been examined within the scope of this study, and some of the most useful literature has been identified. The inconsistencies and non-generalizations uncovered justify the primary data investigation that follows.

2.1. Green Finance Policies Across Regions

Empirical studies demonstrate that green finance policies are universal and uniform across different regions. A simple example is the Chinese hydropower sector; the impact of green finance varies across regions due to differing rules and regulations. Environmental law shapes the institutions and financing types that support green financing (Yang et al., 2024; Hong et al., 2024). Therefore, green finance cannot be standardized and must be aligned with administrative capacity and regulations in mind.

Green finance can help stabilize the volatile investment behavior of firms operating in environmentally sensitive settings. This volatile investment behavior can be easily managed to achieve sustainable and enhanced governance by adopting green financial instruments. According to the research findings of Habib et al. (2023), the Shenzhen Stock Exchange listed firms clearly indicate that the adoption of such mechanisms leads to more disciplined investment behavior, robust and sustainable governance, and better environmental performance. This aligns with the broader market view; green financial instruments are often backed by reputable organizations, making them less risky during credit crunch. Such features make them more attractive to potential investors both ethically and financially.

2.2. Green Finance in Emerging Economies

Green finance is used as a major tool by developing nations in order to overcome the barriers in achieving sustainable growth. Weak financial systems and environmental dangers compel emerging economies to adopt innovative financial mechanisms to acquire both domestic and global capital. It is evident from the empirical studies that the achievement of sustainable development objectives is coupled with the adoption of green financial instruments and environmental risk assessment reports (Hunjra et al., 2023).

Green finance in isolation cannot achieve the environmental goals. Only in the presence of supportive policies can the objectives be achieved. Abbas et al. (2023) studied the renewable energy sector of China and argue that combining environmental taxes with green finance boosts investment. Geopolitical forces pose a threat to these goals, highlighting the need to integrate risk management strategies and contingency planning with green finance while devising green finance strategies. Despite the non-promising results, sector specific challenges persist, such as a lack of uniform methods to measure standardized impact, the risk of green washing, investor literacy asymmetry, and gaps in oversight. The collective efforts of society, governments and the public sector can strengthen the ecosystem. The integration of artificial intelligence and data analytics can further enhance transparency, accountability, and performance measurements (Hemanand et al., 2022).

2.3. Policy Implementation and Effectiveness

In the green finance framework, there is always tension between financing and environmental outcomes. Tao et al. (2021) in their study of Chinese A firms, state that green projects need long-term investments, limiting funding opportunities for green projects. This effect is more pronounced in smaller, non-state-owned companies that are already vulnerable to financing constraints (Li & Chen, 2024). A macro-level research study by T. Zhang and Zhao (2024) states that green finance is an economic catalyst, boosting financial activity. It is pertinent to properly integrate and coordinate green finance with supportive regulations in order to avoid pollution in case of expansion (Tao et al., 2021). It concludes that environmental gains are only achievable if they are well integrated and coordinated with supportive policies.

These dynamics are illustrated in regional programs. S. Khan et al. (2022) analyzed climate mitigation through the Asian Development Bank. The authors outlined finding a striking decline in terms of environmental outcomes among twenty-six Asian countries, suggesting that a well-structured multilateral financial system can deliver environmental benefits. T. Zhang and Zhao (2024), as part of their study, demonstrate that the complexities of green finance exist when it is integrated with calibrated policies. In response, renewable energy investments increase; however, weak institutional policies hinder this progress. Evidence from ASEAN shows that green finance effectively reduces carbon emissions; however, it slows growth, highlighting the need for nuanced policy (M. A. Khan et al., 2021).

Ali et al. (2023) studied fifteen OECD countries using cointegration and quantile methods and demonstrate that green finance, renewable energy consumption, and trade openness reduce long-run carbon footprints. Concurrently inflation can function as a countervailing force, blurring the achievement of these goals and in turn highlighting the need for stable macroeconomic stability (Li & Chen, 2024).

China’s Green Credit Policy serves as a quasi-natural experiment. T. Zhang and Zhao (2024) conclude that the policy deters long-term investment by high-pollution firms and lowers Sulfur dioxide and wastewater emissions. The policy demonstrates that the effect in large and state-owned enterprises is more pronounced. It concludes that organizational structure, ownership, and size shape the ability to leverage green credit (Xia et al., 2023).

2.4. Technology, Digital Finance, and Innovation

Technological capability mediates the link between finance and outcomes. Using a threshold model, J. Zhang et al. (2022) identify an R&D investment level above which green finance has a significantly positive impact on green development efficiency. Below that threshold, green finance can even suppress progress. In manufacturing, the authors find that green finance correlates with low carbon advancement but has weaker links to industrial structure upgrading, implying that finance alone cannot drive profound structural change without complementary industrial policies (Irfan et al., 2022).

Business cycles further complicate effectiveness. Xia et al. (2023) demonstrate that green finance strengthens energy access and stability during recessions, while its effects on energy efficiency depend on technological maturity and expansionary phases (Ali et al., 2023). A cross-country analysis by Hou, Wang, and Zhang suggests that green finance accelerates the growth of renewable energy through fixed asset investment and technological innovation, particularly in advanced financial systems and countries with strong environmental regulations (S. Zhang et al., 2021).

2.5. Carbon Efficiency and the Role of the Digital Economy

Recent studies focus on carbon intensity and efficiency. Empirical studies demonstrate that green finance integration with digital economy plays a key role in mitigating the effects of carbon emission intensity and improving carbon efficiency. These effects are strengthened by improved monitoring and transparent information availability (J. Zhang et al., 2022). The expansion of digital finance at a city level fosters growth in green technologies measured by patents. Therefore, in order to discourage negative spillover to the neighboring regions, it necessitates the development of coordinated strategies for deploying digital finance. (Xu et al., 2023).

2.6. Capital Markets and Risk Transmission

Capital market instruments create powerful signals and spillovers. Issuance of green bonds in the market for the first time gives an environmentally friendly image to the issuer, compelling the competitors to compete in the same field (Xu et al., 2023). In the absence of stable environmental policy, sustainable capital inflow is challenging. Uncertain climate policy amplifies the spillover effects over green assets, increasing volatility and financing costs (Wu & Liu, 2023).

2.7. Spatial Heterogeneity and Digital Inclusion

Wang et al. (2025) in their geographical analysis study, demonstrate that the impact of carbon reduction in various provinces of China varies, due to differences in local laws and industrial standards. Adoption of digital finance works as a double-edged sword. First it encourages green innovation and then reduces carbon emissions. This highlights the importance of incorporating digital finance as a catalyst for environmental outcomes.

2.8. Market Integration Across Green Assets

Research on Market integration broadens the researchers’ understanding. From the previous research study, it is pertinent that green debt instruments are more linked to green stocks rather than to traditional financial equities and assets. This strong relationship fosters the importance of portfolio diversification and green hedged instruments (Man et al., 2023). Yousaf and Yoon (2024) argue that studies on dynamic spillover analysis highlight a dual-directional impact among green bonds, renewable equities, and carbon pricing instruments, underscoring the significance for policymakers to consider these studies while designing policies and regulations.

2.9. Synthesis and Research Gaps

The literature points to three consistent aspects. Green finance yields desirable outcomes when accompanied by technology, strong institutional support, and a stable economy; otherwise, achieving these outcomes is challenging. Second, the digital transformation of finance opens scalable pathways for green investment; however, it introduces geographical asymmetries and implementation challenges that merit coordinated governance. Third, stable and credible policies, including targeted taxation, robust disclosure frameworks, and consistent climate strategies, are indispensable for mobilizing long-horizon capital.

A significant gap in the literature reviewed provides a solid foundation for this study. Many studies rely on secondary or aggregate data that can mask firm-level behavior. The mechanisms through which financing constraints, ownership structures, and managerial cognition interact with green finance instruments are not fully identified. There is limited firm-level evidence from emerging economies with nascent financial infrastructures, where the potential for transformational change is high, yet under-documented. These gaps motivate this study, which collects firsthand data to examine how investments and environmental outcomes are shaped by green finance tools across organizational settings.

3. Methodology

To analyze the impact of green finance on environmental outcomes and investment patterns, a quantitative approach is used. The study is designed to apply a structured plan to find statistically sound evidence-based results that can help policymakers and academic writers.

3.1. Research Design and Setting

The cross-sectional survey design is used to examine the connection between firm-level investment patterns, green finance mechanisms, and environmental outcomes. The research design took into account key variables across diverse populations. Proper econometric model is applied to obtain systematic results. A well-structured questionnaire is designed to obtain data from five relevant green sectors. The sectors include sustainable manufacturing, renewable energy, green construction, sustainable transportation, and waste management. For prior research, a pilot study is conducted for reliability and clarity.

Surveys are administered electronically to ensure national reach and efficient data handling. Firms are identified through industry databases, green finance networks, and sustainability registries. Respondents are managers, finance officers, and sustainability or EHS officers who possess direct knowledge of financing practices and environmental performance.

A minimum target of four hundred firms is set to ensure adequate power for multivariate models and the detection of moderate effect sizes at conventional significance levels. Response progress is tracked, and follow-up reminders are issued to maximize participation.

3.2. Sampling Frame, Sample Size Justification, and Data Collection Protocol

The sampling strategy aligns with national sustainability priorities. Four hundred companies are selected from five priority areas that together account for more than 70% of national greenhouse gas emissions and more than 60% of potential green capital expenditure. These areas are renewable energy, green construction, manufacturing, transportation, and waste management. Stratification encompasses firm size, ranging from micro to large, and ownership structure, including private domestic, foreign-owned, public-listed, and state-owned entities, reflecting the dominance of small and medium enterprises in terms of count and the leadership of large firms in green investment.

A total of one thousand and fifty firms were contacted, of which four hundred provided complete responses. The response rate of thirty-eight percent is consistent with South Asian survey norms. Nonresponse bias is assessed through stratified follow-ups and comparisons between early and late responders, with the results indicating that it is negligible. Missing data is low, at less than five percent, and is concentrated on environmental outcome items for smaller firms. These cases are managed through listwise deletion after verifying randomness and through sensitivity checks with alternative imputation methods.

3.3. Measures and Variable Construction

All variables are coded numerically. Where applicable, items are adapted from international standards such as the Global Reporting Initiative and the Carbon Disclosure Project to enhance comparability and rigor.

3.3.1. Green Finance Utilization

This independent construct is measured using a composite index that captures the value, proportion, and type of green instruments accessed over the past three years. Instruments include green bonds, green loans, and sustainability-linked credit facilities.

3.3.2. Investment Patterns

Dependent measures include annual capital expenditure on green projects, the share of total investment allocated to environmentally sustainable initiatives, and the diversity of green projects such as renewable generation, energy efficiency upgrades, and pollution control.

3.3.3. Environmental Outcomes

Environmental performance is measured using firm-level indicators, including annual carbon emissions in tons, water use in cubic meters, waste generation in tons, and energy intensity, defined as the energy consumed per unit of output. Respondents are requested to report figures that are consistent with third-party audits or verifiable internal records.

3.3.4. Control Variables

Firm-level controls include size, measured by the number of employees, firm age, industry sector, market capitalization (where available), research and development expenditure, and ownership structure, categorized as public or private, and domestic or foreign-owned. Contextual controls for macroeconomic and regulatory conditions are incorporated through country and region indicators as appropriate.

3.4. Empirical Specification and Estimation

Multiple linear regression models are used to test the main relationships between green finance utilization and the continuous dependent variables. The baseline model is

where denotes an investment pattern or environmental outcome for firm , GFi is the green finance utilization index, Xik are control variables, and εi is the error term.

To evaluate improvements in categorical environmental outcomes, such as a high rating of emissions reduction, logistic regression is employed, with odds ratios and confidence intervals reported.

Where applicable, monetary variables with a right skew, such as financial value and green capital expenditure, are analyzed on both level and log scales. Results are presented with heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors, as recommended by the HC3 method. Model fit is summarized using adjusted R-squared for linear models and pseudo-R-squared for logistic models. Additional reporting includes RMSE as a helpful information criterion.

3.5. Subgroup Analysis and Heterogeneity

To assess variation in effects, stratified analyses are performed by sector, firm size, and ownership. Interaction terms are introduced to test the moderating effect of an interaction. Examples include the interaction of green finance with firm size and with research and development intensity to capture capability contingent effects. Subsample regressions distinguish between large firms and small and medium enterprises, as well as between asset-intensive activities and service-oriented activities.

3.6. Mediation Analysis

Given the conceptual role of green capital expenditure as a transmission channel from finance to environmental outcomes, a formal mediation test is conducted. Indirect effects are estimated using percentile bootstraps with 1000 replications and bias-corrected confidence intervals. This complements the main regressions and directly addresses the mediation hypothesis.

3.7. Robustness and Diagnostics

A comprehensive robustness plan addresses sampling variability, model specification, and unobserved heterogeneity.

- a.

- Bootstrap inference

Main regressions are bootstrapped with one thousand replications to obtain non-parametric confidence intervals. Results are compared with HC3 robust standard errors.

- b.

- Alternative specifications

Right skew in finance and capital variables is addressed with log transformations. Industry fixed effects capture unobserved sector heterogeneity. Results are checked under alternative functional forms and with prioritization at conventional percentiles.

- c.

- Heterogeneity checks

Interaction models and sub-sample analyses assess whether effects are more pronounced in large capital-intensive and state-owned firms and weaker in small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as in the service sector.

- d.

- Diagnostic tests

Heteroskedasticity is evaluated and corrected using HC3 inference. Multicollinearity is assessed through variance inflation factors, which remain below the conventional threshold of two. Model specification is examined with the Ramsey RESET test, which indicates no serious misspecification.

- e.

- Endogeneity considerations

Potential endogeneity is explored using an instrumental variable related to prior exposure to environmental regulation. Results are compared with the main ordinary least squares estimates to gauge sensitivity.

- f.

- Data validation

A random subset of approximately twenty-three percent of firm-level environmental reports is cross-checked against sustainability reports and third-party disclosures. The findings of this study support the validity of outcome measures.

3.8. Ethical Considerations and Data Integration

Respondents provide informed consent. Anonymity and confidentiality are assured. To mitigate common method bias, the questionnaire separates predictors and outcomes and randomizes the order of items. Primary survey responses are merged with public firm attributes using a unique firm identifier. Where variables overlap, audited disclosures are prioritized. Consistency checks and outlier screens are applied before analysis.

3.9. Hypotheses of the Study

To empirically test the framework, the following hypotheses are examined.

H1.

Green finance utilization is positively associated with green capital expenditure.

H2.

Green finance utilization is positively associated with improved environmental outcomes.

H3.

The effect of green finance on environmental outcomes is mediated by green capital expenditure.

H4.

Research and development intensity strengthens the positive relationship between green finance utilization and green capital expenditure.

H5.

Firm size positively moderates the relationship between green finance utilization and green capital expenditure.

H6.

The elasticity of green capital investment with respect to green finance utilization differs across industry sectors.

4. Results and Descriptive Analysis

This section presents a structured quantitative portrait of the survey dataset for the four hundred firms, covering Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. Each table is embedded within the narrative and is immediately followed by interpretive commentary that links the descriptive evidence to the overarching inquiry on green finance, investment patterns, and environmental outcomes in Pakistan.

Table 1.

Industry distribution of surveyed firms.

Table 2.

Green finance uptake by industry (number of firms).

Table 3.

Green finance adoption by ownership type and firm size.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of core quantitative variables.

Table 5.

Pearson correlation matrix of financial and environmental metrics.

Green construction, energy development, and manufacturing contain around 66 percent of samples, showing the current focus of Pakistan’s sustainable industry. Waste management practices and transportation are smaller in percentage but show that data exhibit a service-oriented environment and capital-intensive business infrastructures.

Results show that in the last three years around 69 percent of firms have had access to about one green finance instrument. In this scenario the highest proportional uptake was taken by renewable energy, which is consistent with global trends. The waste management industry reported 57 percent response to green financial practices. The disparities among various industries show a trend in credit allocation policies.

Large private companies mostly applied the green finance practices, while large state-owned enterprises have lesser adoption in this case. Similarly, medium size foreign-owned firms have better allocation for green financial practices and small state-owned companies have lesser allocation for the same purpose.

The financial variables with high value transactions elevate the mean above the median and exhibit right skewness. Similarly, environmental output shows a wide dispersion. Subsequent regressions support the use of heteroscedasticity consistent with estimators in that quartile range showing sensational variability.

Correlations between the value of green finance and any environmental indicator are weak (<0.05), suggesting no direct one-to-one relationship in the short run. By contrast, strong positive associations exist among environmental variables themselves, particularly between GHG emissions and water use (r = 0.71), confirming their joint production in industrial processes. The near-zero correlation between green CAPEX spending and environmental burdens suggests that expenditure alone does not guarantee immediate ecological benefits, motivating a deeper causal analysis.

4.1. Multivariate Determinants of Green Capital Expenditure

Table 6 presents a baseline ordinary least squares (OLS) model in which green capital expenditure (Green CAPEX) is regressed on the monetary value of green finance received and a binary adoption indicator. All monetary variables are scaled in millions of Pakistani rupees (PKR) to improve coefficient legibility.

Table 6.

Baseline OLS model of green CAPEX (n = 400).

Neither the magnitude of green finance nor simple adoption shows a statistically significant influence on current-period Green CAPEX. The negative coefficient on the finance value suggests a diminishing marginal propensity to invest as borrowing increases; however, the wide confidence interval cautions against drawing definitive inferences. The negative adjusted R2 confirms that essential explanatory variables are still missing, motivating the extended specification presented next.

4.2. Interaction Effects and Control Variables

Table 7 augments the baseline by adding firm size, R&D intensity, and the interaction of green finance value with size, thereby testing whether larger organizations convert borrowing into investment more effectively.

Table 7.

Expanded OLS with interaction and controls.

The inclusion of structural variables increases the explanatory power to 8.2 percent. Firm size emerges as a strong positive driver of investment, and the significant interaction term shows that larger firms overcome the diminishing-return problem observed earlier. Research and development spending is likewise associated with greater green capital allocation, foreshadowing its mediating role in environmental outcomes.

4.3. Sectoral Elasticities

The sectoral elasticities presented in Table 8 show the elasticity of investment finance by sector, mentioning the sub-samples regression for renewable energy and manufacturing.

Table 8.

Sector-specific elasticity of green CAPEX to finance value.

In the above table, renewable energy enterprises show statistically significant and positive elasticity. Manufacturing companies show negative estimates.

4.4. Environmental Impact Modeling

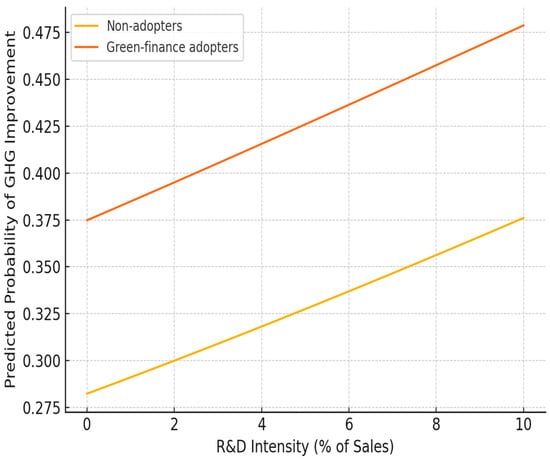

The logistic regression results shown in Table 9 show the probability of CHG emissions improvement on the basis of trend rating as a function of structural, financials and investment controls.

Table 9.

Logistic regression on probability of GHG improvement.

The expenditure rise on research and development shows the improvement of emissions and that the variable of green finance is significant when the R&D capabilities are improved. This pattern shows that ecological benefit is primarily delivered when the environment is favorable.

4.5. Finance Penetration Quintiles

The following analysis ranks firms into quintiles by the ratio of green finance to total borrowing. Table 10 compares mean environmental indicators across quintiles.

Table 10.

Environmental metrics by green finance penetration quintiles.

From lowest to highest the penetration quintiles show a monotonic decline in all three environmental burdens. According to the statistical results (ANOVA) the trend is significant only for energy intensity as the p values is less than 0.05; here. The slow improvement points are consistent with exposure to green projects leading to enhanced environmental outcomes.

4.6. Barriers and Outcomes

Table 11 revisits the barrier categories first introduced descriptively, now adding mean finance values and CAPEX allocations to ascertain whether perceived obstacles correlate with capital scarcity.

Table 11.

Finance and investment by primary barrier.

Firms citing eligibility hurdles actually receive the highest average finance and invest the most considerable sums, implying that stricter criteria accompany large, complex projects rather than deterring them. Conversely, the “low-benefit” group secures the least funding, validating behavioral finance theories that managerial perception can self-limit access, even in the absence of structural barriers.

4.7. Robustness Diagnostics

Table 12 summarizes heteroskedasticity tests, variance-inflation factors (VIFs), and Ramsey RESET diagnostics for the expanded OLS model (Table 7).

Table 12.

Model diagnostics summary (Table 7 specification).

Heteroskedasticity is confirmed. All reported standard errors are HC3-robust. VIF values dismiss concerns about multicollinearity, while the RESET statistic indicates that no neglected non-linear terms are present beyond those already included.

4.8. Comparative Goodness of Fit

Table 13 compares three model specifications—baseline, expanded, and an alternate fixed-effects model using industry dummies—in terms of adjusted R2 and root-mean-square error (RMSE).

Table 13.

Goodness-of-Fit Comparison Across CAPEX Models.

Introducing industry fixed effects marginally improves the explanatory power to 10.4 percent and reduces the prediction error, reinforcing the earlier evidence of sectoral heterogeneity. Nevertheless, the modest magnitudes confirm the high degree of idiosyncrasy in investment decisions at the firm level.

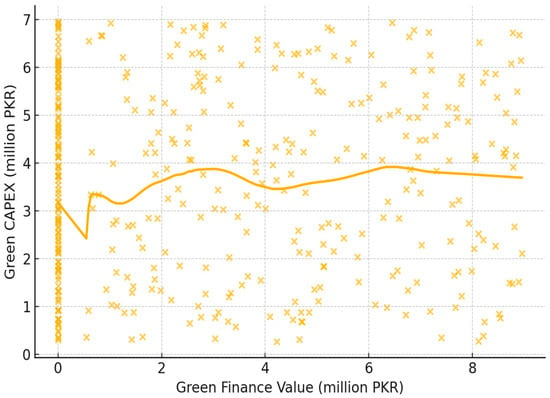

4.9. Visual Evidence

Figure 1 (scatterplot with LOWESS smoother) illustrates the non-linear investment response identified econometrically. Figure 1 plots the predicted probabilities of GHG improvement against R&D intensity, stratified by the status of green finance adoption.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of GHG improvement by R&D intensity and finance adoption. (see embedded figure in electronic article).

Figure 1 confirms the concave pattern: rapid CAPEX escalation at low borrowing levels tapering off beyond PKR 5 million. Figure 2 reveals that adopters achieve markedly higher improvement probabilities only once R&D intensity exceeds roughly 4 percent of sales, visually corroborating the logistic interaction effects discussed in Table 9.

Figure 2.

Scatter of green CAPEX vs. green finance value with LOWESS curve (see embedded figure in electronic article).

4.10. Integrated Discussion

The tables depicted above in Section 3 and Figure 1 and Figure 2 collectively provide advanced insight into Pakistan’s corporate green finance dynamics:

- Firms with higher financial penetration are reaping the benefits of environmental gains (Table 10), indicating learning effects and compliance over time.

- Perception is one of the key obstacles and attitudinal barriers that is interlinked with low funding and investment (Table 11), thus highlighting the psychological perspective on adopting sustainable finance.

4.11. Policy Implications

- Credit regulations do not apply uniformly across all industries; instead, customized credit regulations are adopted. Industries respond differently to economic shifts (Table 8). Regulators tailor policies that address sector-specific risks and achieve desired outcomes.

- To overcome the perception of low benefit, adopting innovative programs can lead to real-life success stories (Table 11).

- Introducing multi-layered eligibility criteria for graduate entry encourages high-potential small firms to benefit from opportunities while maintaining environmental standards.

From Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13, it is concluded that green finance is not an isolated entity; it does not operate in a vacuum. Green finance is linked with sector policies, capacity absorption, and environmental outcomes. These results demonstrate that green finance works better when the ecosystem is supportive in terms of resources, sectoral differences considerations, and learning environment. This synergy sets the stage for our article to complete the mixed-methods approach.

5. Discussion

The findings of this research study demonstrate how green finance effectively redirects firm investment to achieve environmental benefits in emerging economies. There is a global consensus on this perspective that green finance is dependent on three factors: policy design, institutional framework, and supportive financial market characteristics.

The findings of the current study are consistent with the findings of W. Zhang et al. (2024). The authors argue that green finance policies can boost investments to achieve environmental benefits when combined with improved and supportive financing policies and regulations (Chen et al., 2024).

The researchers Mohsin et al. (2023) position green finance as a market-based and policy-driven tool that can achieve both economic and environmental benefits in terms of long-term sustainability (W. Zhang et al., 2024). This synergy, highlighted by Mohsin et al. (2023) illustrates the need for designing policies that integrate both financial and regulatory frameworks, working in coordination to achieve sustainable environmental goals.

The current study reveals that in financially unstable economies like Pakistan, despite companies’ desire to grow sustainably, they are unable to achieve this goal due to the existence of a weak financial system.

Cui et al. (2024) examine behavioral mechanisms that provide a similar solution to the Pakistani context, arguing that compliance-driven strategies have not yet been adopted. They suggest that green financing can spur green investment in polluting firms. It can be achieved by offering behavioral incentives (Bouchmel et al., 2024).

Recent studies have positioned fintech as a key driver for green investments. Javeed et al. (2024) argue that it democratizes access to green financial instruments and steers financial institutions towards corporate environmental outcomes (Cui et al., 2024). With the growing digital finance sector, Pakistan has significant potential to boost the scale and efficiency of its green finance investment. Ding and authors argue that digital finance acts as a catalyst in market competition, increasing capital inflows and enhancing the distribution of green finance (Javeed et al., 2024).

The study’s outcomes are consistent with the existing evidence that firms using digital finance consistently invests in green investments; however, this still depends on the specific context. Moreover, Ma and co-authors demonstrate that the green finance effects are more pronounced in those situations where there is stable and strong institutional support (Ding et al., 2022). The study demonstrates that alone, green finance cannot achieve the desired outcomes. It must be coupled with environmental and institutional support.

Innovation serves as a backbone and a key driver. Desai and Patel (2025) position innovation as a catalyst in strengthening the impact of green finance. Firms that steer investments in R&D attain long-term, sustainable environmental goals compared to those that limit such investments (Desai & Patel, 2025).

In summary, the study demonstrates that green finance alone cannot achieve the best environmental performance outcomes. Green finance, when combined with supportive government policies, robust institutional frameworks, easy access to funding, and technological advancements, can more effectively achieve green goals. The same factors are necessary in developing countries like Pakistan for improved green performance.

6. Conclusions

Based on institutional theory, a resource-based view, and environmental causality, this study investigates the impact of firm-level investment techniques and green outcomes in an emerging economy like Pakistan’s. A sample of four hundred firms from five relevant green sectors is cross-sectionally taken. To strengthen methodological rigor, this study performed various tests to validate the hypothesis and conducted bootstrapping with different combinations, as well as robustness checks.

The study’s findings demonstrate that green finance alone cannot achieve the green performance goals, nor does it guarantee green capital expenditures. The impact is tied to synergies such as the size of the organization, environmental support policies, capacity absorption capabilities, research and development expenditure intensity, and geographical differences. Firms with an innovative approach, larger size, and digital finance capabilities can easily convert green investments into desirable environmental benefits.

The methodological rigor includes cross-validation tests, bootstrapping, and robustness checks to strengthen the credibility of the findings. The results reflect the limitations, underscoring the shortcomings of green finance when not integrated with fintech and effective regulations.

Consequently, green investment, unless coupled with the factors discussed in detail, has no significant impact on environmental outcomes. Green investment alone cannot achieve the desirable green outcomes.

Therefore, policymakers and financial institutions must consider innovation, digital finance, geographical differences, industry elasticity, and regulations when designing policies. These insights provide a foundation for future green finance measures and motivate longitudinal and mixed-methods studies in Pakistan and other developing economies.

The root cause of the greater variability of green investment is the distinct context, as explained. Keeping the similarities in mind, such as the shared pattern of learning, the role of innovation, and sectoral diffidence, demonstrates that Pakistan has greater potential to converge with the best international green practices, if financial support, digital infrastructure, and regulatory consistency are ensured. Positioning Pakistan’s experience within this comparative frame not only validates the robustness of the results but also illustrates how green finance functions in lower-capacity contexts, making the case relevant for other developing economies facing similar structural constraints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization was carried out by L.R. and S.U.; methodology was developed by U.H. and I.S.; software development was handled by U.H.; validation was performed by S.K. and L.R.; investigation was conducted by I.S.; resources were also provided by I.S.; data curation was managed by L.R.; the original draft was prepared by S.U.; review and editing were completed by U.H.; visualization was undertaken by S.K.; project administration was managed by S.K.; and supervision was provided by S.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Institutional Review Board (EIRB) of The University of Swat, Pakistan, on 14 March 2025, under the Notification No. UoS/ORIC/2025/09.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Access is constrained by Institutional Ethics Research Committee regulations.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Microsoft Word’s Spelling and Grammar correct tool and the Pro version of Grammarly for the purposes of assisting with grammar correction of the manuscript and for refining academic language. The authors have reviewed and edited the manuscript and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbas, J., Wang, L., Belgacem, S. B., Pawar, P. S., Najam, H., & Abbas, J. (2023). Investment in renewable energy and electricity output: Role of green finance, environmental tax, and geopolitical risk: Empirical evidence from China. Energy, 276, 126683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Afeef, M. A. M., Kalyebara, B., Abuoliem, N., Yousef, A. N. B., & Alafeef, M. A. M. I. (2024). Green finance and its impact on achieving sustainable development. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 12(3), 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M., Seraj, M., Turuc, F., Tursoy, T., & Uktamov, K. (2023). Green-finance investment and climate-change mitigation in OECD-15 European countries: RALS and QARDL evidence. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26, 27409–27429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchmel, I., Ftiti, Z., Louhich, W., & Omri, A. (2024). Financing sources, green investment, and environmental performance: Cross-country evidence. Journal of Environmental Management, 353, 120230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H., Li, Q., & Geng, Z. (2024). Spatial-econometric analysis of green finance and environmental performance: Evidence from Chinese cities. Energy Policy, 180, 113123. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X., Said, R. M., Rahim, N. A., & Ni, M. (2024). Can green finance lead to green investment? Evidence from heavily polluting industries. International Review of Financial Analysis, 90, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R., & Patel, S. (2025). Analysing the research development in green finance: Performance analysis and directions for future research. FIIB Business Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q., Huang, J., & Chen, J. (2022). Does digital finance matter for corporate green investment? Evidence from heavily polluting industries in China. Energy Economics, 112, 106476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A., Khan, M. A., & Oláh, J. (2023). Does green finance support to reduce the investment sensitivity of environmental firms? Journal of Business Economics and Management, 24(1), 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemanand, D., Mishra, N., Premalatha, G., Mavaluru, D., Vajpayee, A., Kushwaha, S., & Sahile, K. (2022). Applications of intelligent model to analyze the green finance for environmental development in the context of artificial intelligence. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022, 2977824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W., Luo, J., & Du, Y. (2024). Impact of green finance on hydropower investments: A perspective of environmental law. Finance Research Letters, 69, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjra, A. I., Hassan, M. K., Zaied, Y. B., & Managi, S. (2023). Nexus between green finance, environmental degradation, and sustainable development: Evidence from developing countries. Resources Policy, 83, 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M., Razzaq, A., Sharif, A., & Yang, X. (2022). Influence mechanism between green finance and green innovation: Exploring regional policy intervention effects in China. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 182, 121882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S., Latief, R., Cai, X., & Ong, T. (2024). Digital finance and corporate green investment: A perspective from institutional investors and environmental regulations. Journal of Cleaner Production, 435, 141367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., Riaz, H., Ahmed, M., & Saeed, A. (2021). Does green finance really deliver what is expected? An empirical perspective. Borsa Istanbul Review, 22(3), 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Akbar, A., Nasim, I., Hedvicaková, M., & Bashir, F. (2022). Green finance development and environmental sustainability: A panel data analysis. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 1039705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., & Chen, P. (2024). Sustainable finance meets fintech: Amplifying green credit’s benefits for banks. Sustainability, 16(18), 7901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M., Xiao, Z., Liu, M., & Huang, X. (2023). Combining the role of green finance and environmental sustainability on green economic growth: Evidence from G-20 economies. Renewable Energy, 205, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Y., Zhang, S., & Liu, J. (2023). Dynamic connectedness, asymmetric risk spillovers, and hedging performance of China’s green bonds. Finance Research Letters, 56, 104083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V. (2023). Green finance: Regulation and instruments. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 12(1), 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M., Iqbal, N., & Iram, R. (2023). The nexus between green finance and sustainable green economic growth. Energy Research Letters, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L., Chen, L., & Li, K. (2021). Corporate financialization, financing constraints, and environmental investment. Sustainability, 13, 14040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Shan, J., Zhang, Y., Fan, W., Zhang, H., & Ning, J. (2025). The carbon emission reduction effect of digital finance: A spatio-temporal heterogeneity perspective. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 27(5), 11845–11883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R., & Liu, B.-Y. (2023). Do climate policy uncertainty and investor sentiment drive the dynamic spillovers among green finance markets? Journal of Environmental Management, 347, 119008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L., Liu, Y., & Yang, X. (2023). The response of green finance toward the sustainable environment: The role of renewable-energy development and institutional quality. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 59249–59261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., Liu, Y., Zhang, B., & Xiang, B. (2023). Impact of green finance on low-carbon development of the manufacturing industry: Evidence from China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 50772–50782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Yang, B., & Xin, Z. (2024). Green finance development, environmental attention and investment in hydroelectric power: From the perspective of environmental protection law. Finance Research Letters, 69, 106167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A., & Yoon, D. (2024). Dynamic spillovers among green bonds, renewable-energy stocks, and carbon markets. Energy Economics, 122, 107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Li, F., & Ding, X. (2022). Will green finance promote green development? The threshold effect of R & D investment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29, 60232–60243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S., Wu, Z., Wang, Y., & Hao, Y. (2021). Fostering green development with green finance: An empirical study on the environmental effect of the green-credit policy in China. Journal of Environmental Management, 296, 113159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., & Zhao, F. (2024). A study on the relationships among green finance, environmental pollution and economic development. Energy Strategy Reviews, 46, 101290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Ke, J., Ding, Y., & Chen, S. (2024). Greening through finance: Green finance policies and firms’ green investment. Energy Economics, 118, 107401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).