Abstract

Using a time-frequency and quantile connectedness approach, our study examines the complex return spillovers dynamics between BRICS Plus stock markets, the volatility index (VIX), and the global geopolitical risk index (GPRD). By employing advanced models such as TVP-VAR, quantile connectedness, and spectral decomposition, we demonstrate how these markets interact across different market conditions and periods. Our results indicate that the VIX consistently acts as the dominant net transmitter of shocks, especially during periods of heightened uncertainty such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian-Ukraine conflict, and the Trump-era U.S.-China trade tensions. In contrast, the GPRD functions predominantly as a net receiver of shocks, indicating its potential role as a hedge during geopolitical crises. BRICS Plus markets exhibit heterogeneous behavior: Brazil, South Africa, and Russia frequently emerge as net transmitters, while China, India, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE primarily act as net receivers. Spillovers are strongest at the extremes of the return distribution and are mainly driven by short-term dynamics, underscoring the importance of high-frequency reactions over persistent long-term effects. These findings highlight the asymmetric, nonlinear, and state-dependent nature of global financial contagion, offering important insights for risk management, asset allocation, and macroprudential policy design in emerging market contexts.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global financial sphere has witnessed increased volatility due to a sequence of economic crises, political instability, and growing geopolitical tensions (Snene Manzli & Jeribi, 2024a, 2024b). Recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the ongoing Russian-Ukraine conflict, the Israeli-Palestinian war, and the rising U.S.-China trade war have exacerbated this situation and created significant uncertainty among financial investors worldwide (Jeribi & Snene Manzli, 2020; Snene Manzli & Jeribi, 2024a, 2024b; Goyal & Soni, 2024; Ju et al., 2024; Klomp, 2025). In light of this, emerging markets, especially those of the BRICS Plus grouping (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and other significant emerging economies), have increased their financial and trade integration with international markets (Desogus & Casu, 2024). Growth prospects and increased capital inflows have resulted from this integration, but these economies have become more vulnerable to external shocks, cross-market contagion, heightened volatility, and increased risk transmission mechanisms (Panda & Thiripalraju, 2018; Ganguly & Bhunia, 2022).

As global uncertainties become more frequent and severe, investors and regulators are increasingly seeking tools to predict and manage market volatility. In this regard, global risk indicators such as the Volatility Index (VIX) and the Geopolitical Risk Index (GPRD) have emerged as key barometers of market sentiment and systemic risk (Maddodi & Kunte, 2024; Gong et al., 2025). Understanding how these variables affect the BRICS Plus stock markets is important not only for international portfolio diversification and risk management but also for developing timely and effective policies. This is especially essential considering the growing importance of these economies on global growth and financial stability (Lissovolik & Vinokurov, 2019; Vyas-Doorgapersad, 2022; Obajinmi & Garba, 2025).

The VIX, also known as investors’ “fear gauge,” measures market expectations of short-term volatility based on the price of the S&P500 index (Gürsoy, 2020). It is widely recognized as a proxy for global investor sentiment and risk aversion, especially during times of increased market uncertainty (Whaley, 2000; Sarwar, 2012). When volatility expectations evolve, the VIX spikes through heightened fear among market participants, and it frequently leads to capital reallocation away from riskier assets (Zhang & Giouvris, 2022). As a result, the VIX not only reflects emotion in U.S. markets, but it also has a considerable impact on worldwide markets, particularly in financially linked economies (Zhang & Giouvris, 2022). For instance, Gürsoy (2020) examined the relationship between the VIX and the BRICS stock markets. Using a causality test, the findings highlight the heterogeneous impact of the VIX on BRICS stock markets, revealing that changes in this index exert a significant influence only on the Russian and South African stock markets. These findings suggest that some BRICS markets are more sensitive to global investor sentiment than others, a result that carries important implications for portfolio risk management and financial integration in emerging markets. Sarwar (2012) investigated the relationships between the VIX and stock market returns in the BRIC countries. The study shows a strong and significant negative correlation between changes in the VIX and stock returns in Brazil and China, suggesting that the VIX serves as an effective proxy for global investor fear in these markets. As for India, this negative correlation was only detected during a short period, suggesting a weaker or more time-sensitive relationship. In contrast, Russia demonstrated no significant relationship with the VIX. In addition, asymmetric effects were detected for Brazil and China, with the VIX responding more to negative than to positive stock market movements, reinforcing its role as a gauge of fear rather than optimism. Using a cross-quantilogram approach, S. J. H. Shahzad et al. (2022) examined the hedging ability of Bitcoin, gold, and U.S. VIX futures against downside risks in BRICS stock markets. Their findings revealed that, among all assets, VIX futures emerged as the strongest hedging and diversification instruments in Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa, particularly during times of turmoil.

On the other hand, the GPRD, developed by Caldara and Iacoviello (2022), assesses geopolitical tensions based on the frequency of newspaper articles referencing geopolitical risks (GPR), including war threats, acts of terrorism, and diplomatic tensions. Unlike the VIX, which is market-based, the GPR captures larger adverse political events and conflict-related uncertainties that can harm global economic activities, investment strategies, trade flows, and investor confidence (Caldara & Iacoviello, 2022; Salisu et al., 2022a). The index has gained significant attention during recent global disturbances, including the COVID-19 pandemic (Shaik et al., 2023), the Russian-Ukraine conflict (U. Shahzad et al., 2023; Shaik et al., 2023), and the escalating U.S.-China trade war (L. Liu et al., 2025). These events have surged the demand for accurate measures of geopolitical instability and their financial implications (Khatib et al., 2025).

Salisu et al. (2022a) investigated the impact of global GPR on stock returns in advanced economies, namely G7 and Switzerland. Their findings indicate that GPR is a significant predictor of stock returns in these countries. Interestingly, they discovered that stock markets react more negatively to the threat of geopolitical events (such as war or terrorism) than to the actual occurrence of such events. Moreover, their results indicate that the model applied in their study outperforms others that exclude GPR, suggesting the value of incorporating geopolitical risk into return forecasting approaches. Using a Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregression (TVP-VAR) model, Feng et al. (2023) investigated how GPR affects volatility spillovers among major global stock markets, particularly those of the G7 and BRICS countries. They discover that volatility spillovers between markets tend to rise during major global events like wars, financial crises, and the COVID-19 pandemic. They also state that the influence of GPR on total spillovers and connectedness varies over time. Using NARDL and QARDL models, Asomaning (2023) examined the impact of GPR on the foreign exchange reserves of BRICS countries. Based on the NARDL model, the study reveals that GPR has asymmetric effects on foreign exchange reserves in these countries, especially in the long run. The QARDL model reveals that these effects vary across different quantiles. For instance, over the long term, GPR significantly influences reserves at higher quantiles in Brazil and lower quantiles in China and South Africa, but shows no significant effect in Russia and India, whereas in the short run, GPR has an impact only at lower quantiles in South Africa.

Despite the growing research on financial integration and the vulnerability of BRICS markets to shocks, empirical evidence remains limited regarding how these markets, particularly those within the expanded BRICS Plus framework, respond to shifting global financial and GPR. In fact, most existing research either treats the VIX and GPR as static explanatory variables or ignores their time-varying impact throughout different phases of crisis. In this regard, our study fills this literature vacuum by investigating the time-varying connectedness between BRICS Plus stock indices, the VIX, and the GPRD using a multidimensional analytical approach. In particular, we apply the TVP-VAR model, the quantile connectedness approach, and spectral decomposition techniques.

The TVP-VAR model, developed by Primiceri (2005), is particularly suitable for detecting the changing nature of interconnectedness and spillovers in the presence of non-linear, non-stationary, and regime-switching shocks, characteristics that are mostly relevant during periods of turmoil. The quantile connectedness approach, as developed by Ando et al. (2022), allows for the examination of risk spillovers across different market situations, including extreme tails. Meanwhile, spectral decomposition, also known as the time-frequency connectedness developed by Baruník and Křehlík (2018), enables the differentiation between short, medium, and long-term elements of connectedness, providing a detailed perspective of shock transmission across different frequencies.

By including these approaches, our research adds to a better understanding of how BRICS Plus markets deal with global uncertainty. It also offers timely insights for investors and policymakers dealing with increasingly volatile and complex market settings.

The purpose of this study is twofold. First, it seeks to assess the dynamic, tail-dependent, and frequency-specific spillovers between BRICS Plus stock markets and global risk indicators (namely, VIX and GPRD). Second, it aims to identify the most vulnerable and resilient markets within the BRICS Plus network during times of increased uncertainty. The findings are projected to improve the understanding of global risk transmission processes and provide practical recommendations for international portfolio diversification and policy formulation.

2. Literature Review

Examining spillovers and connectedness in financial markets has garnered significant attention recently, particularly in the context of increasing economic integration and the spread of systemic risk. Early research by Diebold and Yilmaz (2009, 2012) and Diebold and Yılmaz (2014) established the basis for measuring return and volatility spillovers using variance decomposition techniques. Their approach has since developed to include time-varying structures, notably the TVP-VAR model, which enables dynamic estimation of connectedness without applying a rolling window framework (Antonakakis et al., 2020).

In the context of developing markets, BRICS nations have been intensively examined for their growing financial significance globally. For instance, Billah et al. (2022) investigated return and volatility spillovers between energy and BRIC stock markets. They state that different crises, including COVID-19, intensified connectedness and return and volatility spillovers among these markets. Using a quantile regression methodology, Mensi et al. (2014) assessed the dependence structure between BRICS stock markets and global stock and commodities, highlighting the role of financial crises in shaping cross-market dependency dynamics. Ahmad et al. (2018) investigated the financial connectedness among the BRICS countries and three global bond market indices (represented by the U.S., EMU, and Japan) by focusing on how returns and volatility spillovers move across these markets. Their findings reveal that, among the BRICS bond markets, Russia and South Africa operate as net transmitters of shocks, causing important risk to the network, while India and China display weaker connectedness, providing better hedging and diversification possibilities. Their results also demonstrate that China is strongly tied to the U.S., which emerges as the most important transmitter of shocks to BRICS. Globally, their findings highlight the heterogeneity of BRICS bond markets and suggest that India and China are the most beneficial choices for risk management strategies.

Using the TVP-VAR approach, Dahir et al. (2020) examined the dynamic volatility connectedness between the BRICS stock markets and Bitcoin. Their findings indicate that the cryptocurrency acts mostly as a recipient of volatility, poorly contributing to the overall volatility of stock markets in BRICS countries. Instead, market price risk from these stock returns is found to be the main driver of volatility, suggesting limited systemic risk from Bitcoin to BRICS stocks. Using Diebold and Yilmaz’s (2012) volatility spillover index, Panda et al. (2021) analyzed how regional and developed stock markets interact with BRICS stock markets using daily USD-based data during three periods: pre-crisis, during the global financial crisis, and post-crisis. Their results reveal that volatility transmission doubled during the crisis and decreased by half post-crisis.

By applying quantile and asymmetric connectedness approaches, Nyakurukwa and Seetharam (2023) examined the return spillover among BRICS stock markets. Their findings reveal strong interdependence, especially during extreme market situations, both positive and negative. Moreover, by separating the impacts of positive and negative returns, the authors discovered that positive spillovers are more relevant, suggesting that BRICS stock markets are more correlated during bullish periods than during bearish ones. Mensi et al. (2025) examined how different types of oil shocks can affect BRICS stock markets using a novel R2 decomposed connectedness framework that separates immediate (contemporaneous) from delayed (lagged) spillovers. Their results demonstrate that the strength and nature of these spillovers vary over time and are influenced by major global events, such as COVID-19.

Moving on, the VIX has often been integrated in studies on global market interconnectedness thanks to its role as a tool for measuring investors’ fear. For instance, Sarwar and Khan (2017) investigated the impact of the VIX on stock returns in different emerging markets during the global financial crisis. Their findings illustrate that high VIX values cause both immediate and delayed decreases in emerging market returns, with the strongest effects occurring during the financial crisis. Additionally, they reveal that VIX-driven uncertainty has a bigger negative impact on emerging market returns than the influence of the markets’ past returns. Similarly, Sarwar (2012) reported asymmetric spillovers from the VIX to emerging markets (namely, BRIC countries), suggesting its predictive ability during times of crises and its role as a gauge of fear. G. Sharma et al. (2019) investigate how the volatility indices (VIXs) of the BRICS nations are informationally linked. Their empirical results reveal a long-run equilibrium correlation among some country pairs, suggesting that their expected volatility moves together over time. Their study also reveals strong time-dependent associations, meaning that volatility in one BRICS market can impact others over time. Applying a TVP-VAR connectedness approach, Gökgöz et al. (2024) assessed the time-varying volatility spillover among BRICS stock markets and various asset price implied volatility indices (including VIX). Their results indicate that volatility connectedness is dynamic and intensifies during Black Swan events.

Utilizing a Quantile-on-Quantile spillover analysis, Altinkeski et al. (2024) explored the interaction between global stock market returns and the perceived market uncertainty, measured by the VIX. By examining weekly data across various developed and emerging markets, their study demonstrates how different levels (quantiles) of VIX impact stock returns. Moreover, their key findings reveal that indirect spillovers between the VIX and stock returns (i.e., spillovers across different quantile levels) are stronger than direct ones (same quantile levels). Specifically, they state that high stock returns are associated with low VIX levels, while low returns align with high VIX levels, confirming the VIX’s role as a “fear gauge.” Using a quantile connectedness approach, Kruel and Ceretta (2025) analyzed connectedness and return spillovers between crude oil, the VIX, the S&P 500, and six Latin American stock markets. Their results show that the S&P 500 consistently transmits shocks, while crude oil mainly acts as a shock receiver. Moreover, the findings show that return spillovers intensify during extreme market conditions, with the VIX acting as a strong shock transmitter in bullish times.

More recently, the increasing significance of GPR as a driver of market behavior has resulted in the emergence of indices such as the GPRD. Caldara and Iacoviello (2022) created this news-based index that quantifies GPR from historical text data. Subsequent studies, such as NguyenHuu and Örsal (2024) and Bajaj et al. (2023), state that geopolitical risk significantly and negatively impacts financial stability, particularly in emerging markets.

In this regard, Nasouri (2025) analyzed the impact of GPR on stock market returns and volatility in both developing and developed countries. The results reveal that the impact of GPR varies across different regions. For instance, American markets may benefit from heightened geopolitical threats while emerging markets tend to experience higher volatility and financial disorder, especially during extreme situations. Using a two-step GMM approach, Adel and Naili (2024) examine the effect of GPR on bank profitability in emerging economies across the Middle East and Africa. Their results indicate that Middle Eastern banks are significantly affected by GPR, with those that anticipate or adapt to such risks performing better. In contrast, the effect of GPR on African banks’ profitability is weak and insignificant. Using the GARCH-MIDAS methodology, Salisu et al. (2022b) explored the impact of GPR on stock market volatility in emerging economies. Their results show that these markets’ volatility rises in response to GPR. Their study also highlights that incorporating GPR in volatility models provides significant benefits for investors in managing risk.

Using the GARCH (1,1) approach, A. Sharma (2024) examined the impact of GPR related to the Russian-Ukraine conflict on stock market volatility in BRICS countries. The results show a sharp increase in volatility in Russia’s index at the beginning of the conflict, suggesting immediate sensitivity to the war. However, other BRICS markets remained relatively stable, indicating a swift adjustment to the geopolitical crisis. Based on a Quantile-on-Quantile regression model, Yeboah et al. (2025) explored the influence of GPR on exchange rate dynamics in Sub-Saharan African emerging economies. Their findings demonstrate that the sensitivity of exchange rates to geopolitical risk varies across countries and market conditions.

Despite the growing attention to both the VIX and the GPRD, few studies have jointly analyzed their impact on stock markets, with most research concentrating on developed economies (see, for instance, Bossman et al., 2023). When it comes to emerging stock markets, particularly BRICS Plus countries, no previous research has jointly examined the impact of both indices (VIX and GPRD) on these markets. In this regard, our study tries to fill this gap in the literature by being the first to examine the dynamic connectedness and directional spillovers between BRICS Plus markets, the VIX, and the GPRD.

3. Data and Empirical Methodology

3.1. Data and Descriptive Statistics Summary

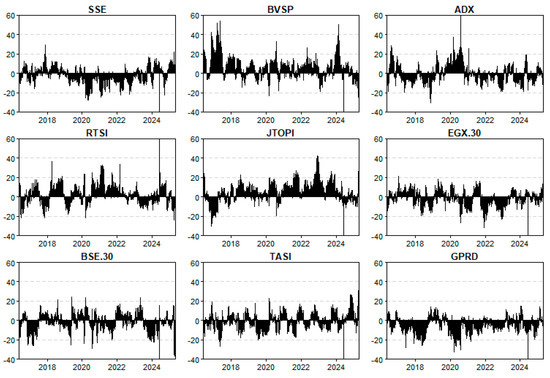

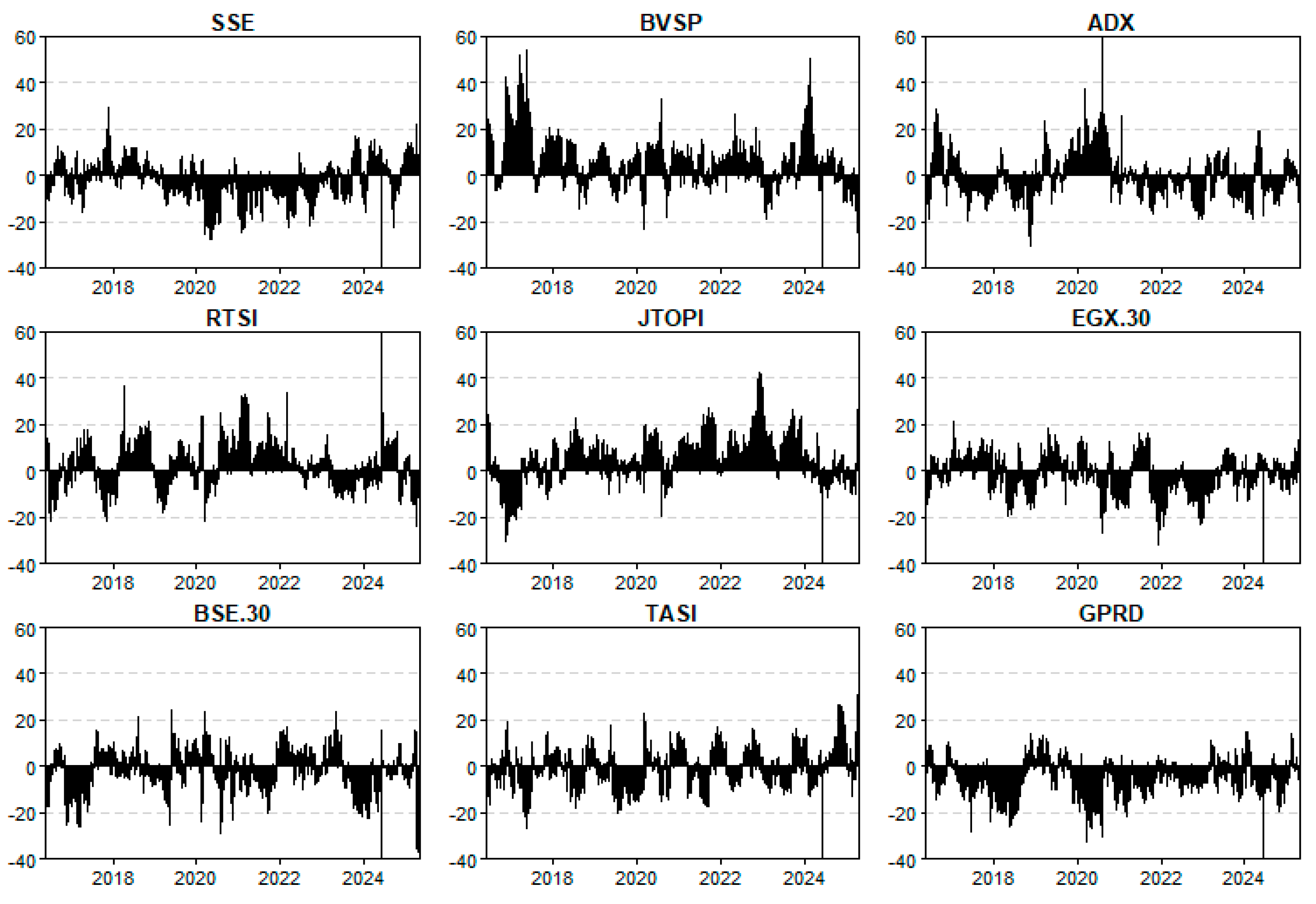

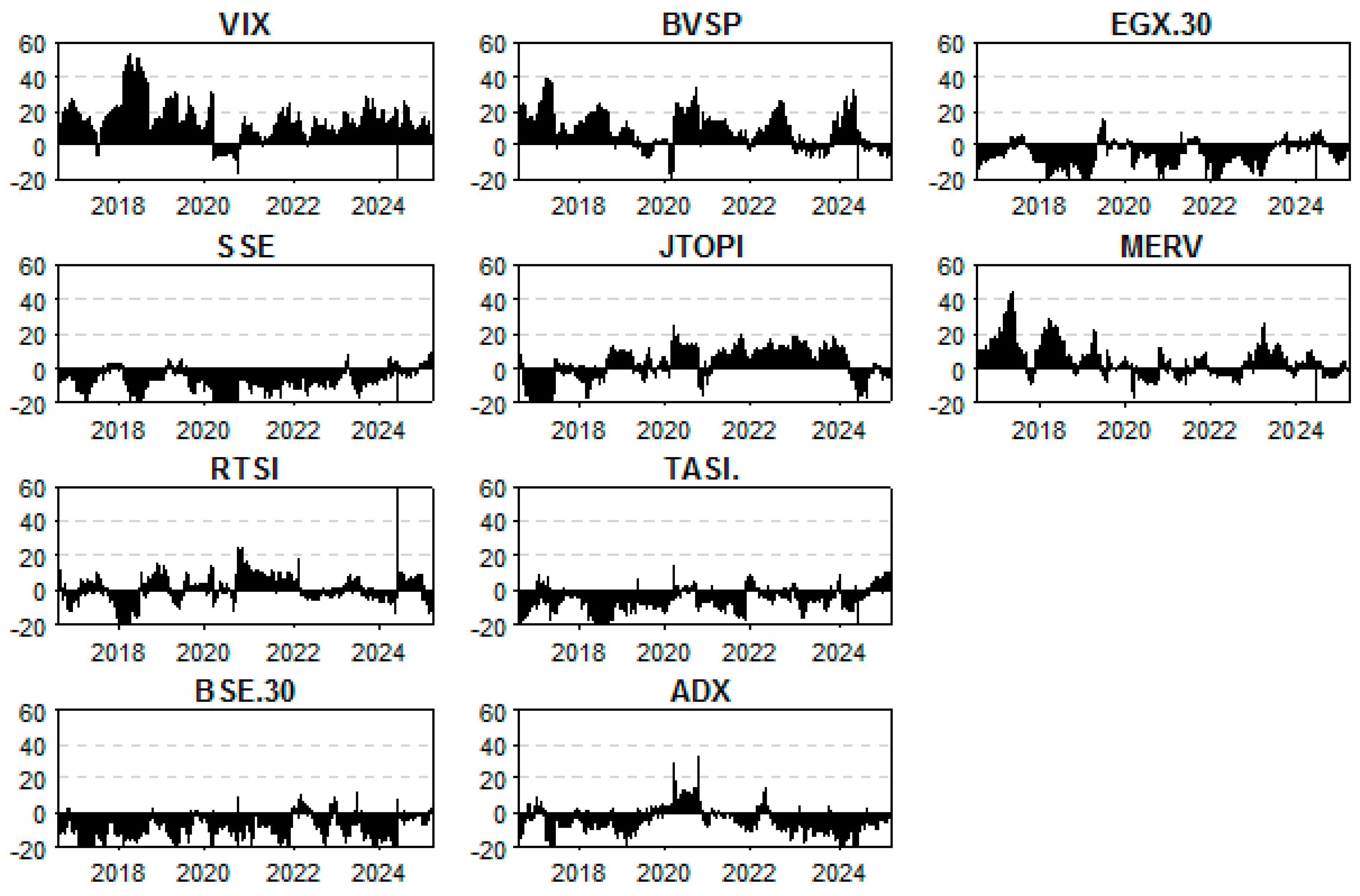

Our study covers daily data from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2024 related to the stock indices of BRICS+ members (namely, Brazil (BVSP), Russia (RTSI), India (BSE.30), China (SSE), South Africa (JTOPI), and invited members: Egypt (EGX.30), the United Arab Emirates (ADX), and Saudi Arabia (TASI)), the volatility index VIX, and the geopolitical risk index GPRD. Daily returns are converted into logarithmic returns, calculated as , with representing the closing price of an asset at time t. All price sequences were obtained from DataStream1.

The descriptive statistics summary of the return series is provided in Table 1. It shows that the mean returns of all assets are close to zero, with a few appearing significant at the 5% or 1% levels, such as BSE.30, EGX.30, and ADX. This situation suggests limited average daily movements but with statistical relevance in certain markets. The standard deviation coefficients vary substantially, indicating differences in market volatility, with the VIX and SSE being the most volatile and EGX.30 being the least volatile asset.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Most of the return series is skewed to the left, as indicated by the statistically significant negative skewness values, except for the VIX and RTSI, which display a positive skewness. The excess kurtosis (Ex.K.) values are high across all return series, especially for RTSI, suggesting the presence of fat tails (leptokurtic) and extreme events in return distributions. These findings are further supported by the Jarque–Bera test, which indicate that the return series is far from being normally distributed.

The ERS (Elliott, Rothenberg, and Stock) unit root test suggests strong stationarity for all returns, with significant negative values at the 1% level of significance. This indicates that the return series are mean-reverting and appropriate for further time-series analysis. Moreover, the return and squared return Ljung–Box statistics are all highly significant, suggesting the presence of autocorrelation and ARCH effects in the return series, which justifies our choice for models that account for time-varying volatility.

Table 2 presents the Kendall correlation of the return series. It reveals a significant negative association between the VIX and all other indices, consistent with its role as a fear gauge that typically moves inversely with stock markets. Particularly, the VIX and BVSP showed the strongest negative association, followed by JTOPI and RTSI. Moreover, positive and statistically significant correlations are observed mostly among the emerging stock market indices, with the highest association between BSE.30 and JTOPI. This situation suggests the presence of market co-movement between these assets or a common exposure to global or regional shocks among them. Even though the correlations appear to be moderate, they highlight the connectedness of these markets and justify further investigation into their dynamic relationships. As for the GPRD, it showed varied insignificant negative and positive correlations with the rest of the assets.

Table 2.

Kendall correlation matrix between assets.

3.2. Empirical Methodology

In this study, we applied an empirical methodology that follows a structured and multi-layered approach to capture the complexity of interconnectedness among different financial markets. We start by implementing a TVP-VAR model, which allows for dynamic estimation of connectedness measures without requiring rolling windows, thereby preserving the full sample and accounting for potential structural changes over time. Building on this, we apply the Quantile Connectedness framework to explore the heterogeneity of spillovers across different market conditions, particularly under extreme bearish and bullish regimes. This step is important for uncovering asymmetric transmission effects that may be overlooked by mean-based approaches. Finally, we extend the analysis to the frequency domain using the Time-Frequency Connectedness method, which decomposes spillovers across short-, medium-, and long-term horizons. This multi-layered approach offers a comprehensive understanding of market interdependencies, offering both time-sensitive and regime-dependent insights that are essential for risk management, portfolio allocation, and policy formulation in increasingly interconnected financial systems.

The three methodological layers are designed to provide a complementary view of market connectedness. The TVP-VAR captures time-varying dynamic interdependence among markets, serving as the baseline framework. Quantile Connectedness builds on this by revealing asymmetric and nonlinear spillovers across different market conditions (bearish, normal, bullish). Finally, Time-Frequency Decomposition distinguishes short-term, transitory effects from long-term, persistent spillovers, allowing for insights into how shocks propagate across horizons. Together, these steps integrate dynamics across time, market states, and frequency, offering a multidimensional understanding of financial contagion.

We use a quantile and frequency connectedness approach to investigate the quantile spillover dynamics across several financial markets. This technique enables us to examine the transmission process using both quantiles (q) and frequencies (ω). As developed by Ando et al. (2022), Bouri et al. (2021), and Chatziantoniou et al. (2021), the quantile connectedness approach serves as the foundation for our investigation:

where and represent vectors of endogenous variables, q is a quantile in the [0, 1] range, and p is the lag length. is the conditional mean vector, is a matrix of QVAR coefficients, and is an error term with a corresponding covariance matrix.

To proceed with this, Equation (1) is converted into the QVMA (∞) form by applying Wold’s theorem as follows:

The following procedure is to compute the Generalized Forecast Error Variance Decomposition (GFEVD) across a prediction horizon H. The decomposition clarifies how much of the forecast error variance of series (i) is due to shocks in series (j):

In this case, normalization is necessary since rows do not total to one. In turn, this form enables us to calculate important measures of connectedness.

Starting with the Net Pairwise Directional Connectedness (NPDC) that identifies spillover paths by showing which variable is the “influencer” and which is more “influenced” within a network. The NPDC is calculated as follows:

When > 0 ( < 0), this suggests that the series j (i) has a greater impact on the series i (j).

Next, we present the directional connectedness by indicating whether an asset is primarily transmitting risk (TO) or receiving it (FROM) and is calculated as:

The Total Net Directional Connectedness (NET) that represents the difference between TO and FROM connectedness is calculated to illustrate whether an asset is a net “shock transmitter” or a net “shock receiver” to the network:

A positive (negative) value suggests that the series i is a net transmitter (net receiver) of shocks.

Finally, the Total Connectedness Index (TCI) that tells how tightly all the variables are linked and is computed as follows:

For the frequency-domain study, we investigate the frequency response function using Stiassny’s spectral decomposition approach.

The spectral density is computed using a Fourier transform of the QVMA(∞) form. The frequency-domain GFEVD, normalised in the same manner as the time-domain GFEVD and is expressed as:

By averaging over specified frequency bands, we can generate frequency-based connectivity metrics. Our analysis considers two frequency bands: d1 = (π/5, π) for short-term (1 to 5 days) and d2 = (0, π/5) for long-term dynamics (6 days and beyond). These frequency-based measurements, like time-domain measures, give a complete perspective of the spillover impacts in the short and long run.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. TVP-VAR at the Median Quantile

4.1.1. BRICS Plus and the VIX2

Following Diebold and Yilmaz’s (2012) approach, we present the dynamic connectedness among the VIX and eight emerging stock market indices in Table 3. The diagonal components represent own-variance shares, while the off-diagonal components indicate the directional spillovers transmitted across markets. The “FROM” column shows the total spillovers received by each market from the rest of the system, whereas the “TO” row captures the spillovers transmitted from one market to others. The TCI stands at 33.01%, indicating a moderate level of return transmission between assets.

Table 3.

Dynamic Connectedness.

The VIX emerges as a major net transmitter of shocks, with a net spillover of 14.14%, suggesting its important role in transmitting volatility across global markets. In the same manner, BVSP and JTOPI also appear as net transmitters of shocks, while markets like SSE, BSE.30, ADX, and EGX.30 are net receivers of shocks, suggesting their sensitivity to external events.

Specifically, Brazil and South Africa emerge as net transmitters of shocks due to their high financial openness, strong commodity dependence, and larger shares of foreign institutional investors. These structural features make them more sensitive to external volatility, positioning them as key channels through which global shocks propagate to other emerging markets. Conversely, China and India act predominantly as net receivers. Their more regulated capital accounts, deeper domestic investor bases, and policy frameworks provide insulation from short-term external shocks, which explains their tendency to absorb rather than transmit volatility. The Middle Eastern members—Saudi Arabia and the UAE—demonstrate policy-driven stability and energy-linked buffers, which moderate spillover transmission. While increasingly integrated with global capital markets, these features help limit the propagation of global shocks, positioning them between pure transmitters and receivers.

The Normalized Pairwise Net spillover (NPT) values further confirm that the VIX and BVSP are the most influential assets within the network, with VIX being the most significant shock transmitter to all markets, especially to RTSI and BVSP.

The “Inc.Own” row shows the total of own and cross-market contributions to forecast error variance, highlighting the importance of own-market impacts in return variability, particularly for the VIX (114.14%) and BVSP (106.62%). Nonetheless, significant cross-market linkages have been discovered, suggesting the importance of connectedness dynamics in understanding regional and global risk transmission.

It is important to note that the Generalized Forecast Error Variance Decomposition (GFEVD) measures correlation-based directional influences rather than strict causality. Following the frameworks of Diebold and Yilmaz (2012) and Diebold and Yılmaz (2014) and the time-varying extension by Antonakakis et al. (2020), GFEVD is widely used in the connectedness literature to quantify dynamic interdependence and information transmission across financial markets. As emphasized by Baruník and Křehlík (2018), this approach provides valuable insights into systemic risk propagation, indicating which markets act as net transmitters or receivers of shocks, without implying causal relationships in the Granger sense. Accordingly, our results should be interpreted as reflecting directional spillovers and information flow, consistent with prior studies (e.g., Bouri et al., 2021; Ando et al., 2022), which adopt similar interpretations to capture transmission mechanisms in dynamic settings.

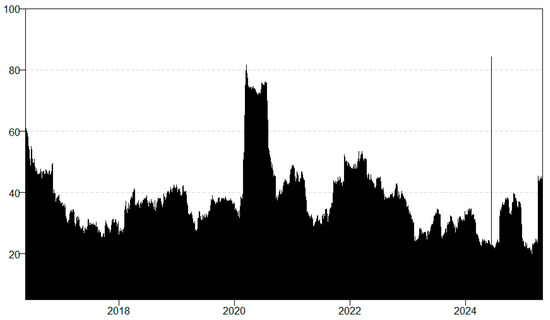

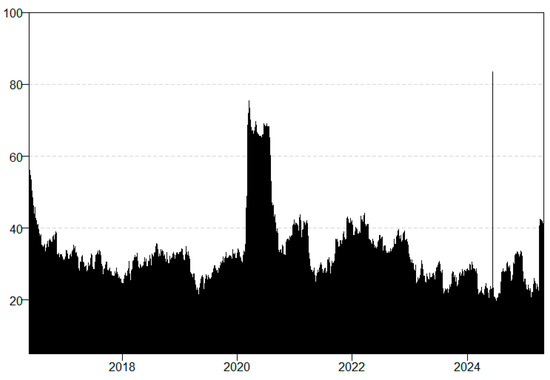

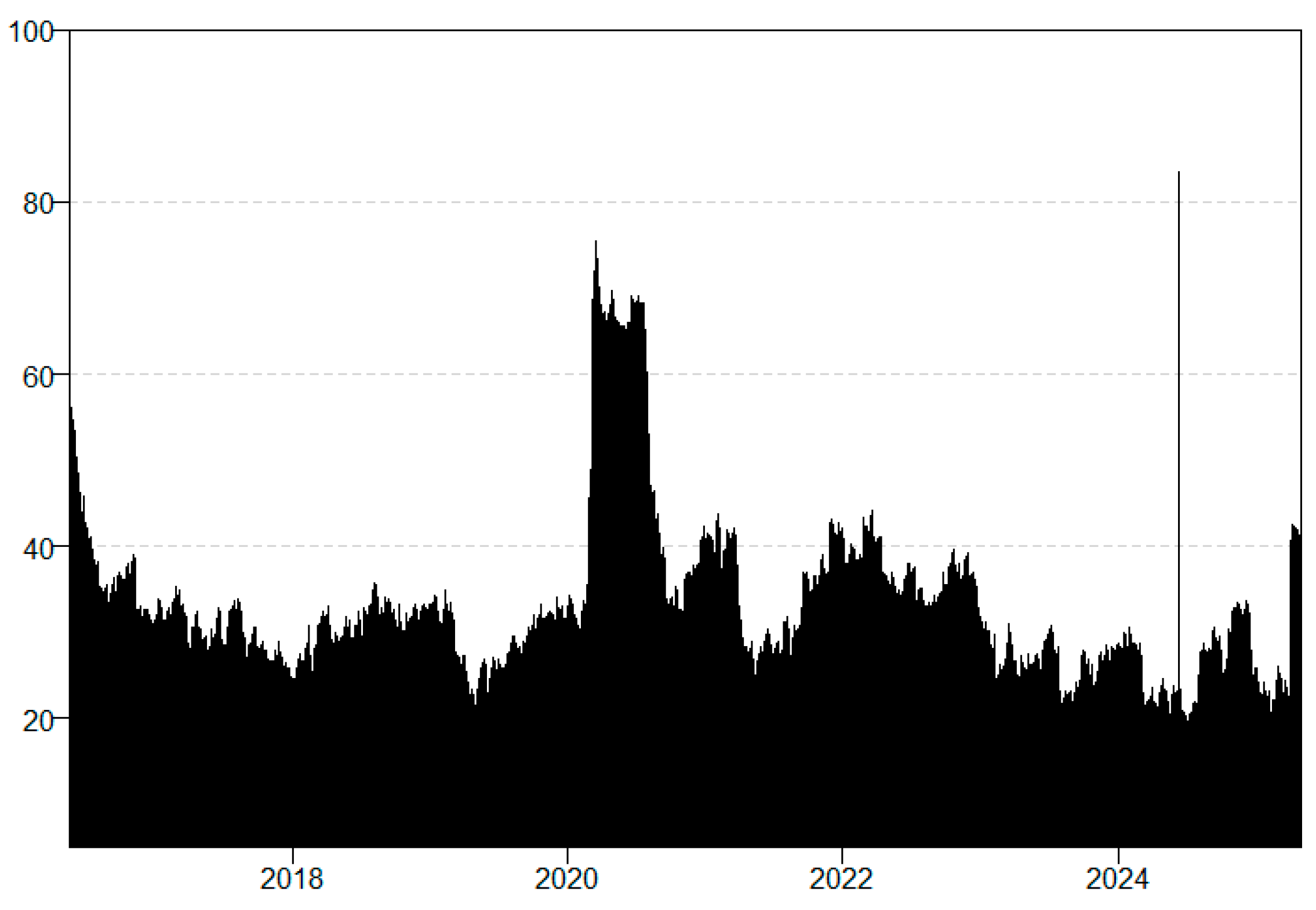

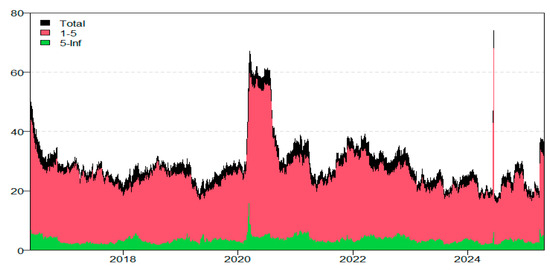

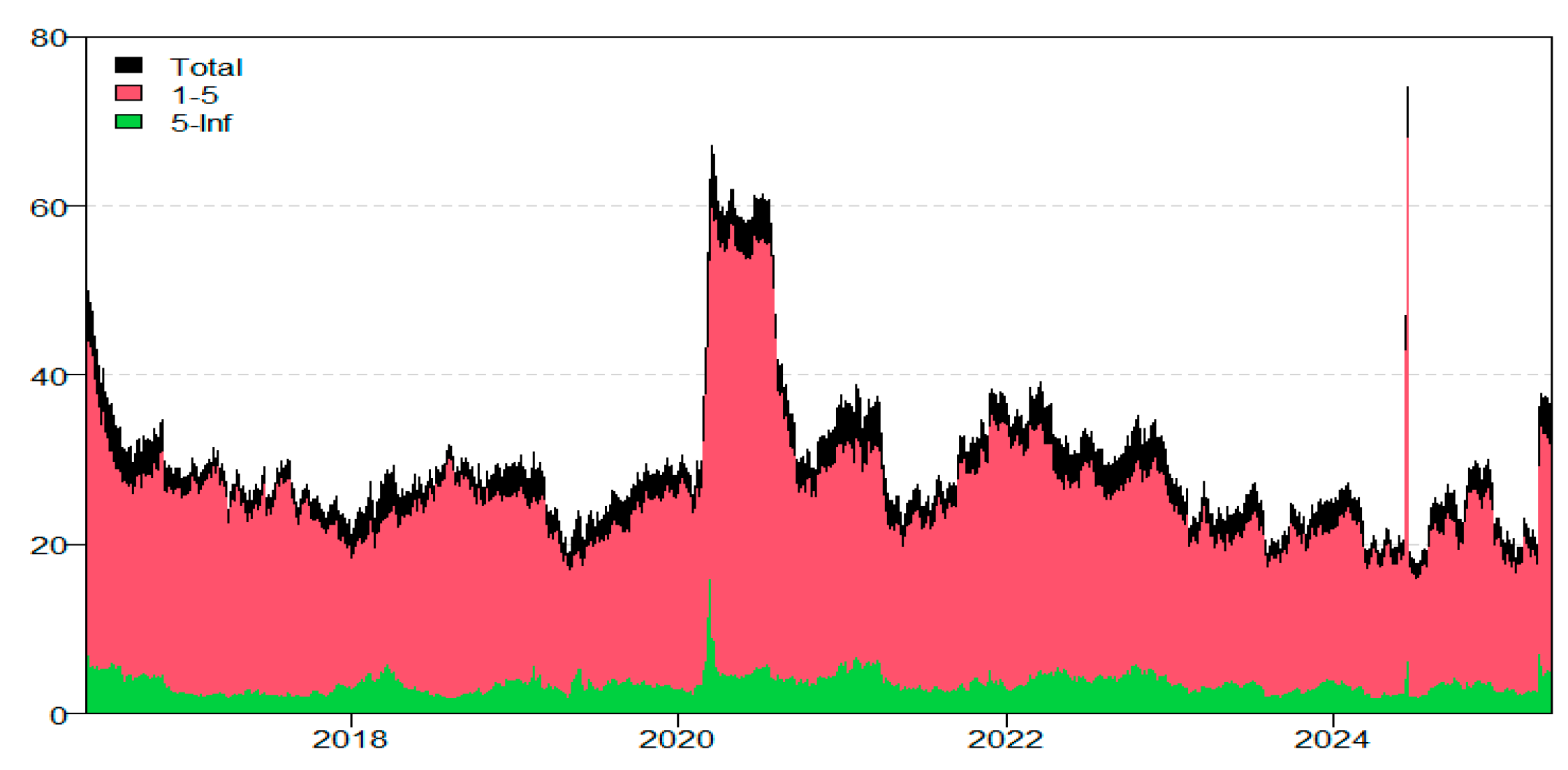

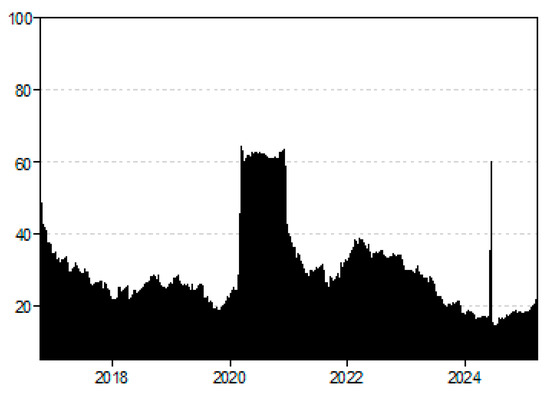

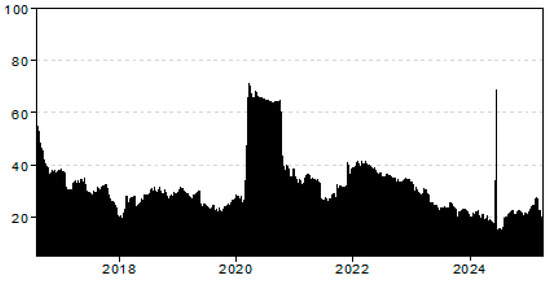

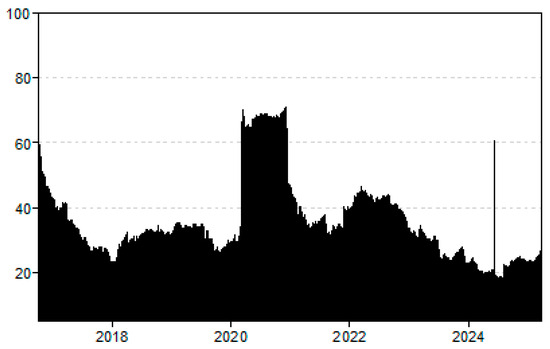

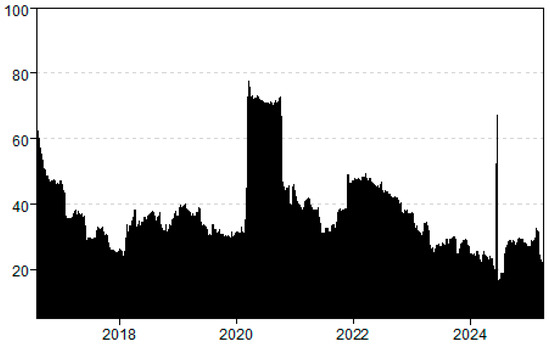

Figure 1 illustrates the total dynamic connectedness for the period ranging from 2017 to 2024. This metric, developed from the TVP-VAR approach, measures the total degree of interconnectedness among financial assets. The figure demonstrates substantial fluctuations in connectedness, with significant peaks observed around 2020, aligning with the financial disturbances triggered by the COVID-19 health crisis (Snene Manzli & Jeribi, 2024a, 2024b). These surges indicate elevated levels of market integration and shock propagation across assets during periods of distress. The gradual increase in connectedness as we approach 2024 signals rising systemic risk and stronger co-movements between assets, which might be driven by geopolitical tensions (Snene Manzli & Jeribi, 2024a, 2024b) or changes in global macroeconomic circumstances. The dynamic character of total connectedness emphasizes the international markets’ sensitivity to different shocks, as disturbances in one market rapidly spread across interconnected financial assets. This behavior underscores the significance of tracking cross-market linkages to forecast systemic vulnerabilities and design effective risk management strategies.

Figure 1.

Total dynamic connectedness.

Figure 1.

Total dynamic connectedness.

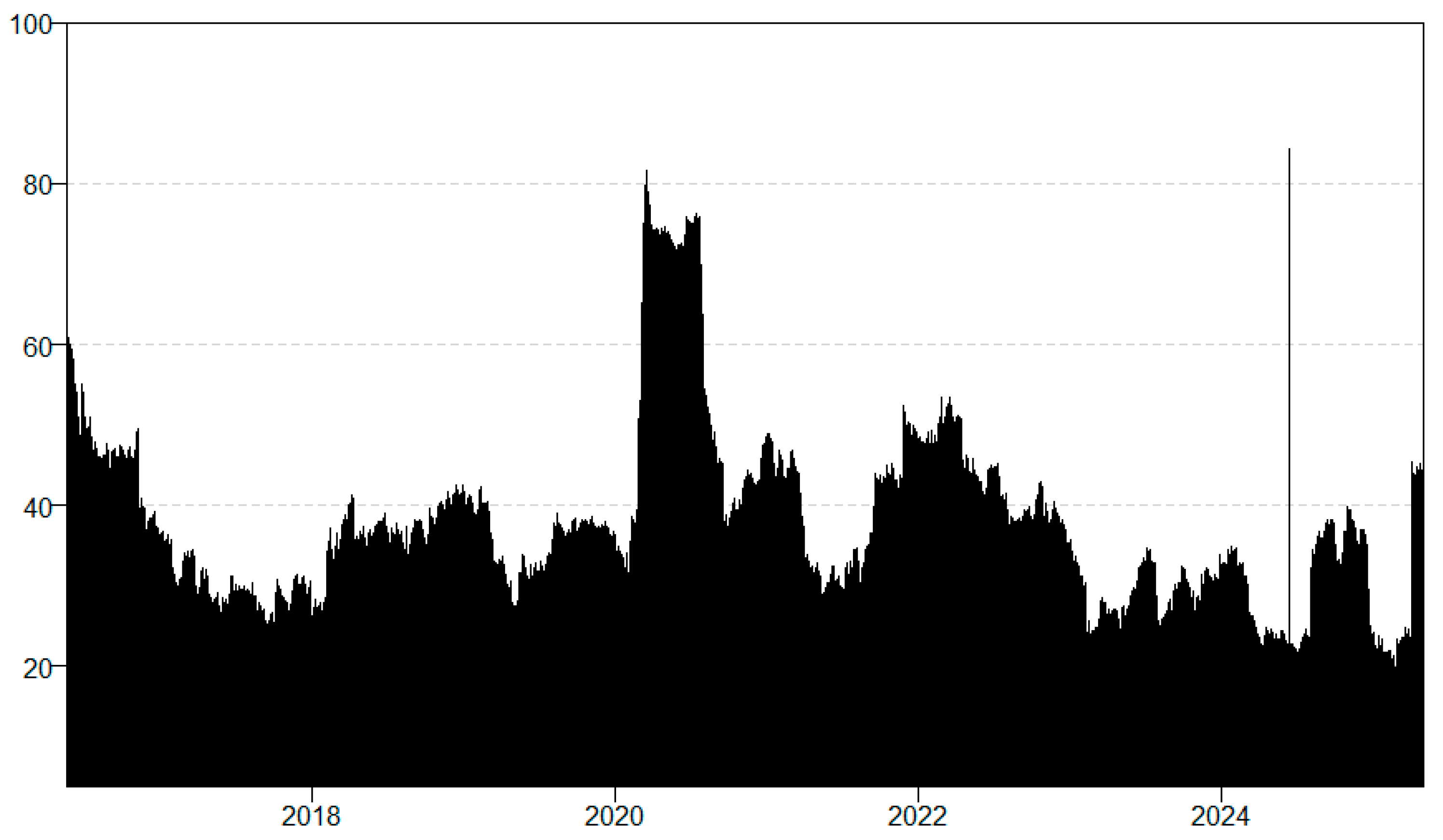

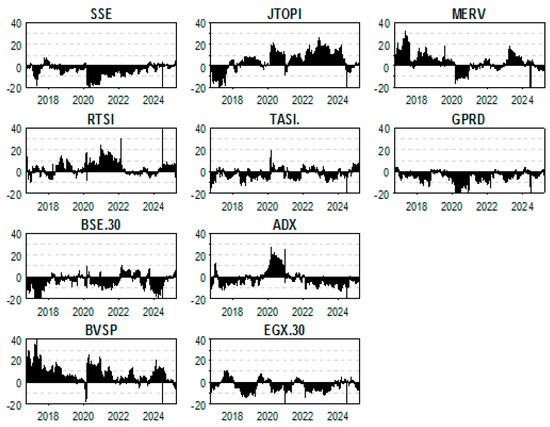

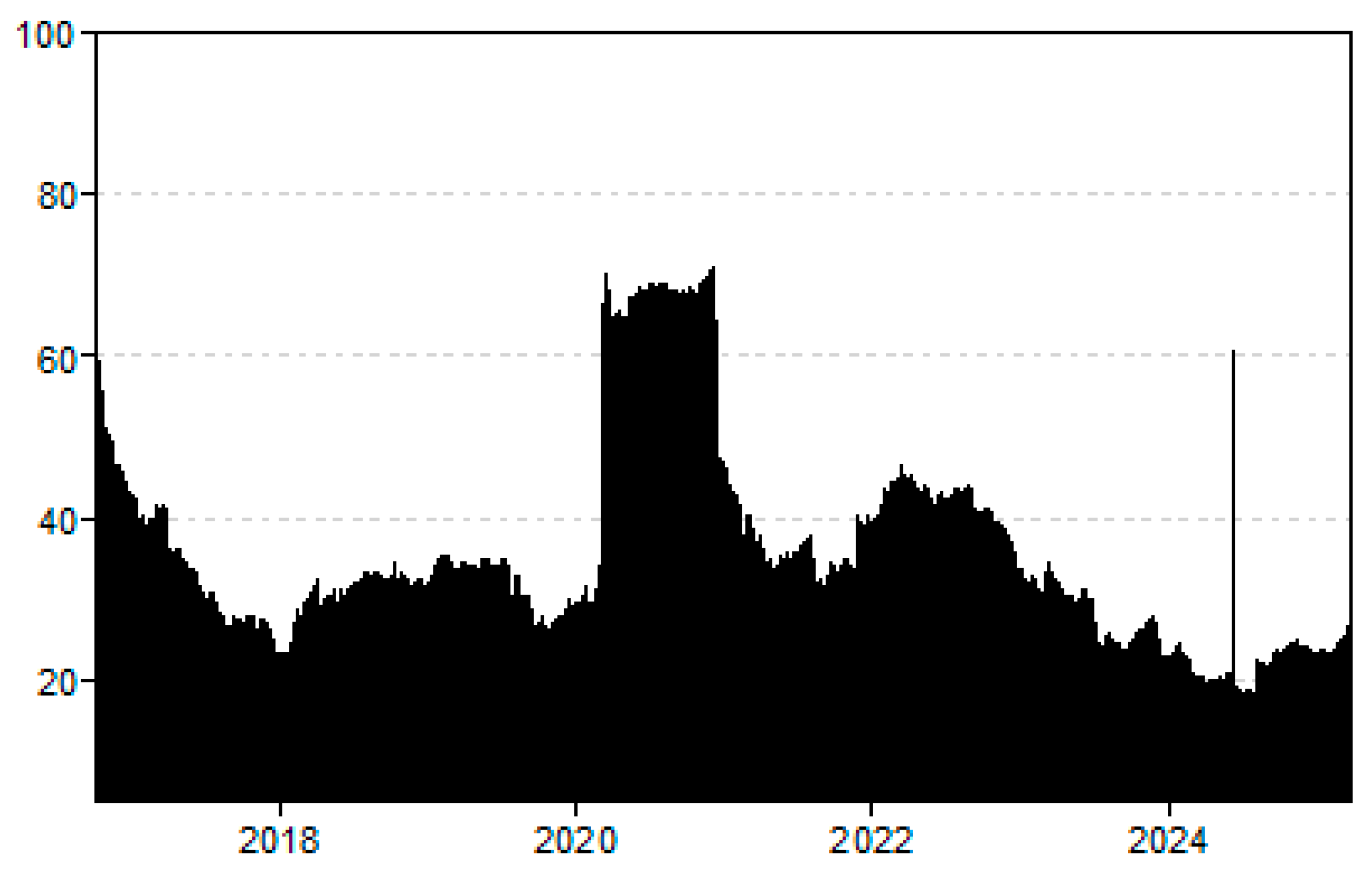

Figure 2 illustrates the total net dynamic connectedness for the nine financial indices, specifically the VIX, BSE.30, TASI, SSE, BVSP, ADX, RTSI, JTOPI, and EGX.30. According to Wang et al. (2022), Rizvi et al. (2022), and Snene Manzli and Jeribi (2024a, 2024b), negative values on this plot indicate that the assets are shock receivers. In fact, this figure demonstrates the directional influence of each index on the system, differentiating between net transmitters and net receivers of shocks. Indices such as the VIX, which is recognized as a worldwide risk indicator, show strong net transmission impacts, especially during times of market turmoil. This can be illustrated by its strong fluctuations, suggesting that volatility shocks originating from the VIX often permeate through other global markets. This was particularly noticeable during the U.S.-China trade war (2018–2019), which was extended under the Trump administration (T. Liu & Woo, 2018), and during the COVID-19 health crisis. In fact, the Trump effect, significantly marked by severe policy changes and the imposition of aggressive tariffs (York, 2025), created frequent volatility spikes in the VIX. These volatility shocks did not remain confined to U.S. markets but spilled over significantly to other global stock markets, underscoring the VIX’s role as a central transmitter of global risk. Moreover, this dominant transmitter position of the VIX continued throughout the second phase of Trump’s presidency, as markets remained highly sensitive to trade negotiations, foreign policy conflicts, and the broader uncertainty caused by unusual political leadership (York, 2025). Comparably, the BVSP and ADX show a high degree of net connectedness, which may be related to both external market forces and regional economic instability. Conversely, some indices, such as JTOPI and EGX.30, exhibit comparatively lower net transmission levels, suggesting a more passive or insulated role in the global connectedness structure. The coordinated increases in several indices around 2020 demonstrate how economic shocks spread quickly across national borders during global crises. This interdependence shows that local market disruptions are not isolated but rather are a part of a larger financial network that increases risk exposure when economic uncertainty is high. The diversity in net connectedness further suggests that some markets are the main channels through which shocks spread, while others are more related to the global transmission network. These insights, which identify which markets act as boosters or dampeners of global financial instability, are essential for understanding systemic risk and for developing strategies for portfolio diversification.

Figure 2.

Net total dynamic connectedness.

Figure 2.

Net total dynamic connectedness.

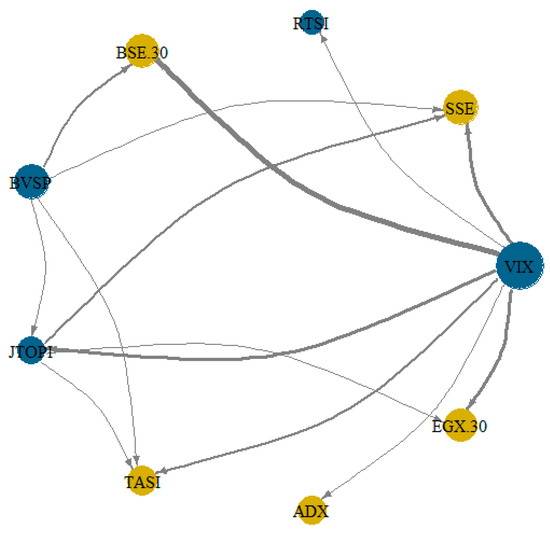

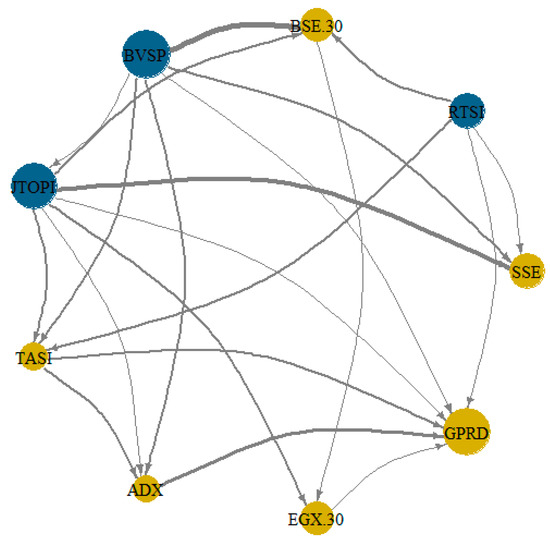

Figure 3 illustrates the net pairwise directional connectedness between the different assets. This figure provides a visual network of shock transmissions between assets by identifying whether the asset is a net shock transmitter (blue nodes) or a net shock receiver (yellow nodes). This can also be identified by the number, thickness, and direction of arrows originating from or received by each node. This plot identifies the Chinese (SSE) and the Saudi Arabian (TASI) stocks as key net receivers of shocks, followed by the India (BSE.30), Egypt (EGX.30), and United Arab Emirates (ADX) stocks. As for the rest of the indices, they are considered net shock transmitters, with the VIX being the most important shock transmitter among the whole system.

Figure 3.

Network plot of net pairwise connectedness3.

Figure 3.

Network plot of net pairwise connectedness3.

4.1.2. BRICS Plus and the GPRD (See Note 2)

From Figure 4, we can see that the total dynamic connectedness between the BRICS Plus stock indices and the GPRD are similar to those previously observed between the BRICS Plus stocks and the VIX. This similarity suggests that both GPR and global financial uncertainty exhibit a similar impact on BRICS Plus markets, highlighting their shared sensitivity to global instability.

Figure 4.

Total dynamic connectedness.

Figure 4.

Total dynamic connectedness.

The net total dynamic connectedness between the BRICS Plus stock market indices and the GPRD is presented in Figure 5. This plot shows that the BRICS Plus stock indices exhibit fluctuating spillover effects over time. In particular, the GPRD, which captures global political risk, displays an opposite pattern of connectivity dynamics compared to the VIX. It acted mostly as a net shock receiver, suggesting its possible use as a hedge against the BRICS Plus stocks (Wang et al., 2022; Rizvi et al., 2022; Snene Manzli & Jeribi, 2024a, 2024b). This evolution suggests that these emerging markets respond differently to GPR when compared to financial market volatility, supporting the findings of A. Sharma (2024), who discovered that geopolitical risk has a limited impact on BRICS markets. Moreover, Figure 5 illustrates that connectedness regarding each stock and the rest of the system peaks around major global events, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, reinforcing the vulnerability of these emerging and developing markets to external systemic shocks.

Figure 5.

Net total dynamic connectedness.

Figure 5.

Net total dynamic connectedness.

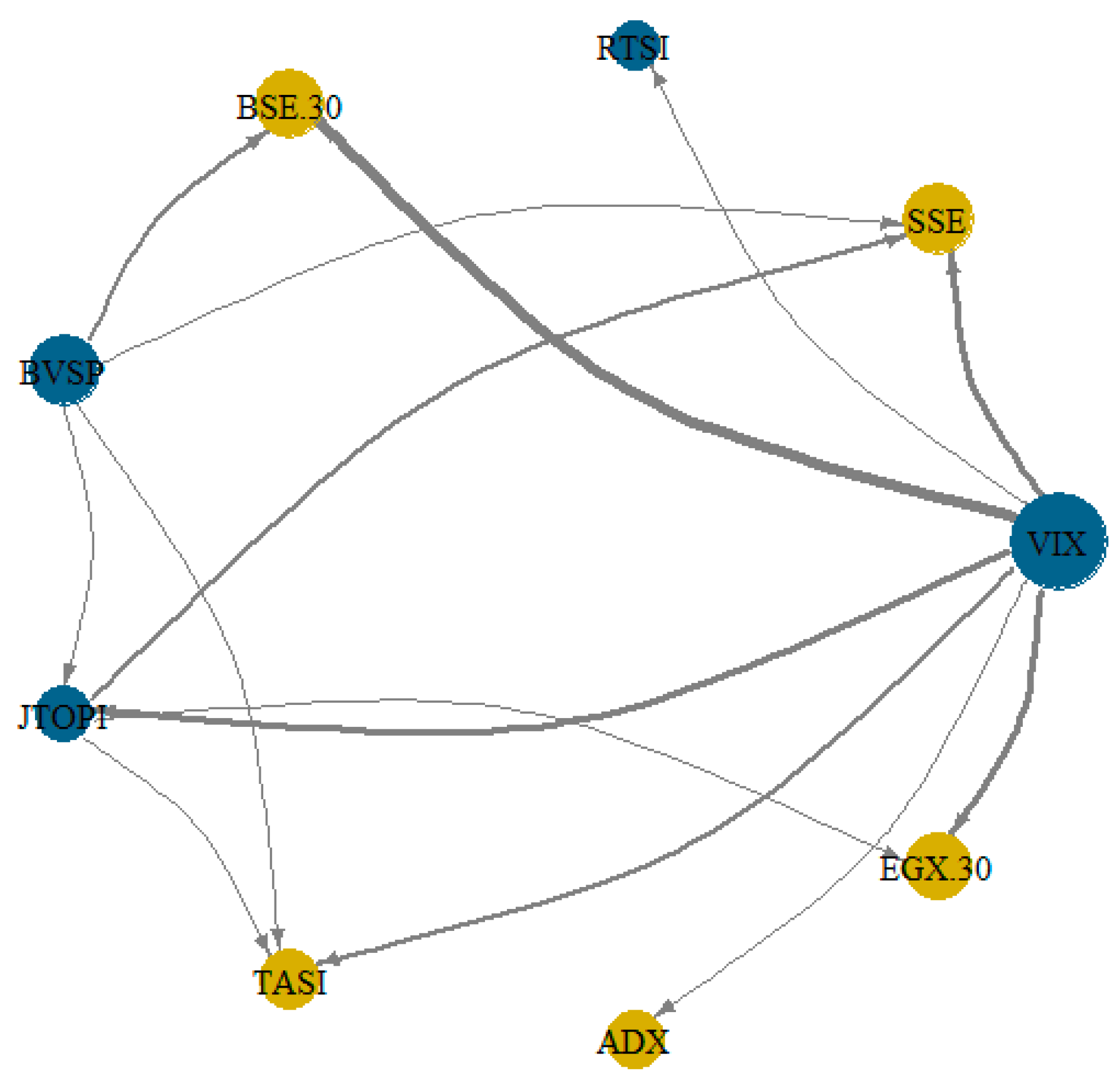

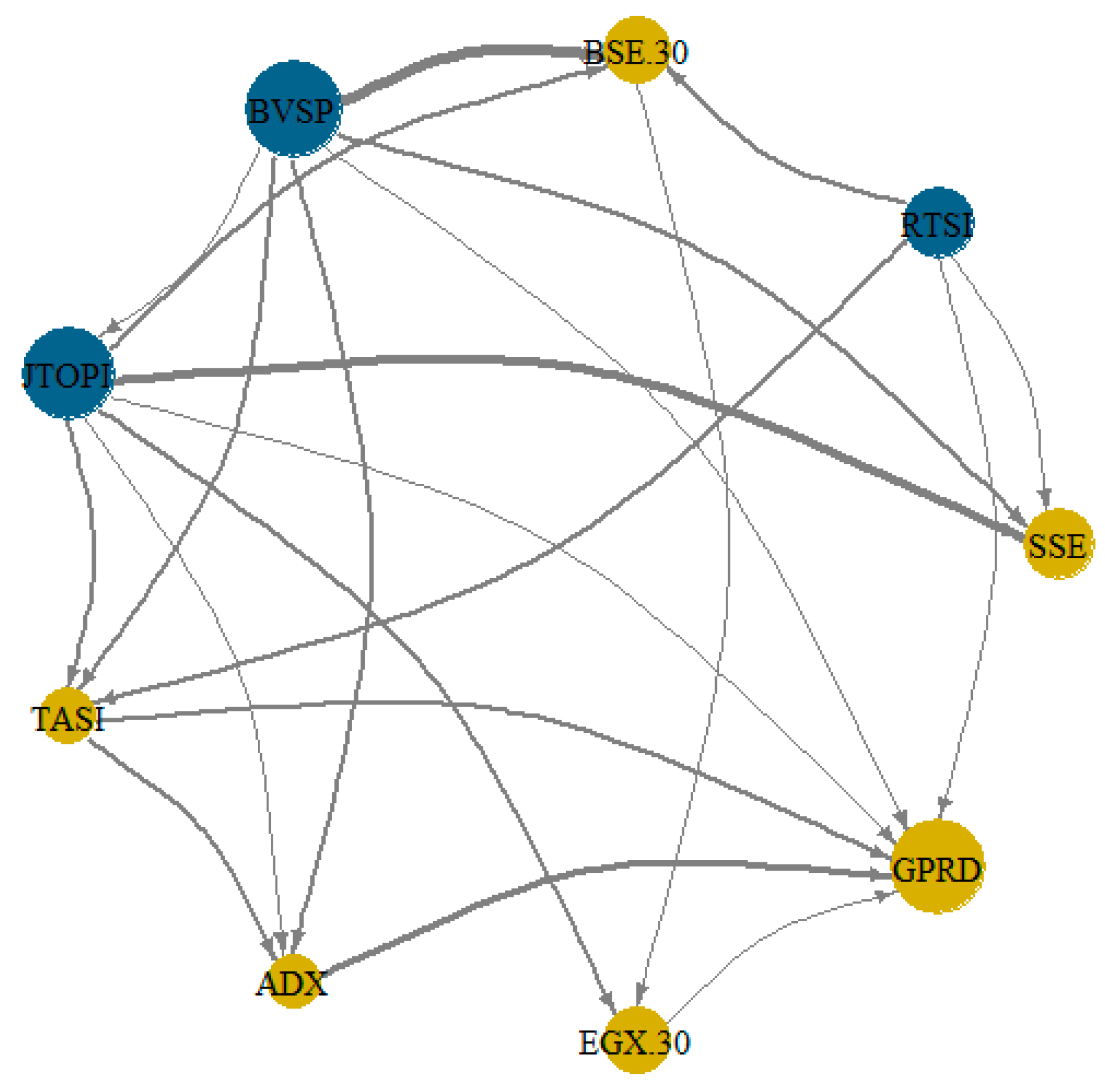

In the same way, Figure 6 presents the net pairwise directional connectedness between the BRICS Plus stock market indices and the GPRD. This network plot illustrates the complex interconnectedness between emerging stock market indices, with link thickness representing spillover intensity and node colors distinguishing between net receivers (yellow) and net transmitters (blue). The outcomes show that Brazil (BVSP), South Africa (JTOPI), and Russia (RTSI) emerge as significant shock transmitters within the global financial network. These markets exhibit considerable influence on other indices, as evidenced by the relatively thick connections emanating from them. Conversely, India (BSE.30), China (SSE), Saudi Arabia (TASI), the United Arab Emirates (ADX), and Egypt (EGX.30) predominantly function as shock receivers, suggesting greater vulnerability to external financial conditions. As for the GPRD, it is considered the most important shock receiver from the global system, supporting its hedging ability against the BRICS Plus stocks during times of crisis. This result is in line with Salisu et al. (2022b), who suggest that incorporating GPR within a system provides significant benefits for investors in managing risk (see Note 2).

Figure 6.

Network plot of net pairwise connectedness.

Figure 6.

Network plot of net pairwise connectedness.

4.2. Quantile Connectedness Results

4.2.1. Total and Net Dynamic Connectedness Between BRICS Plus and VIX Across Different Quantiles

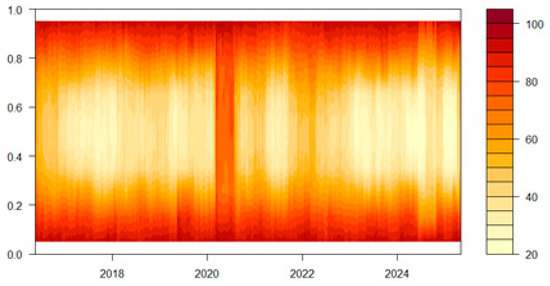

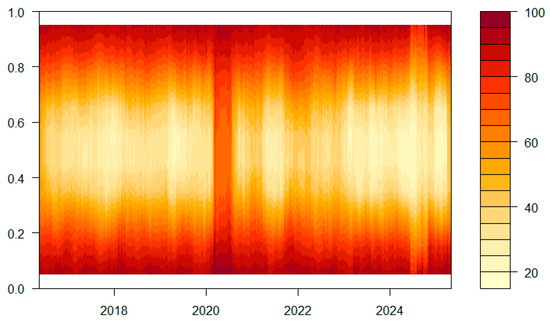

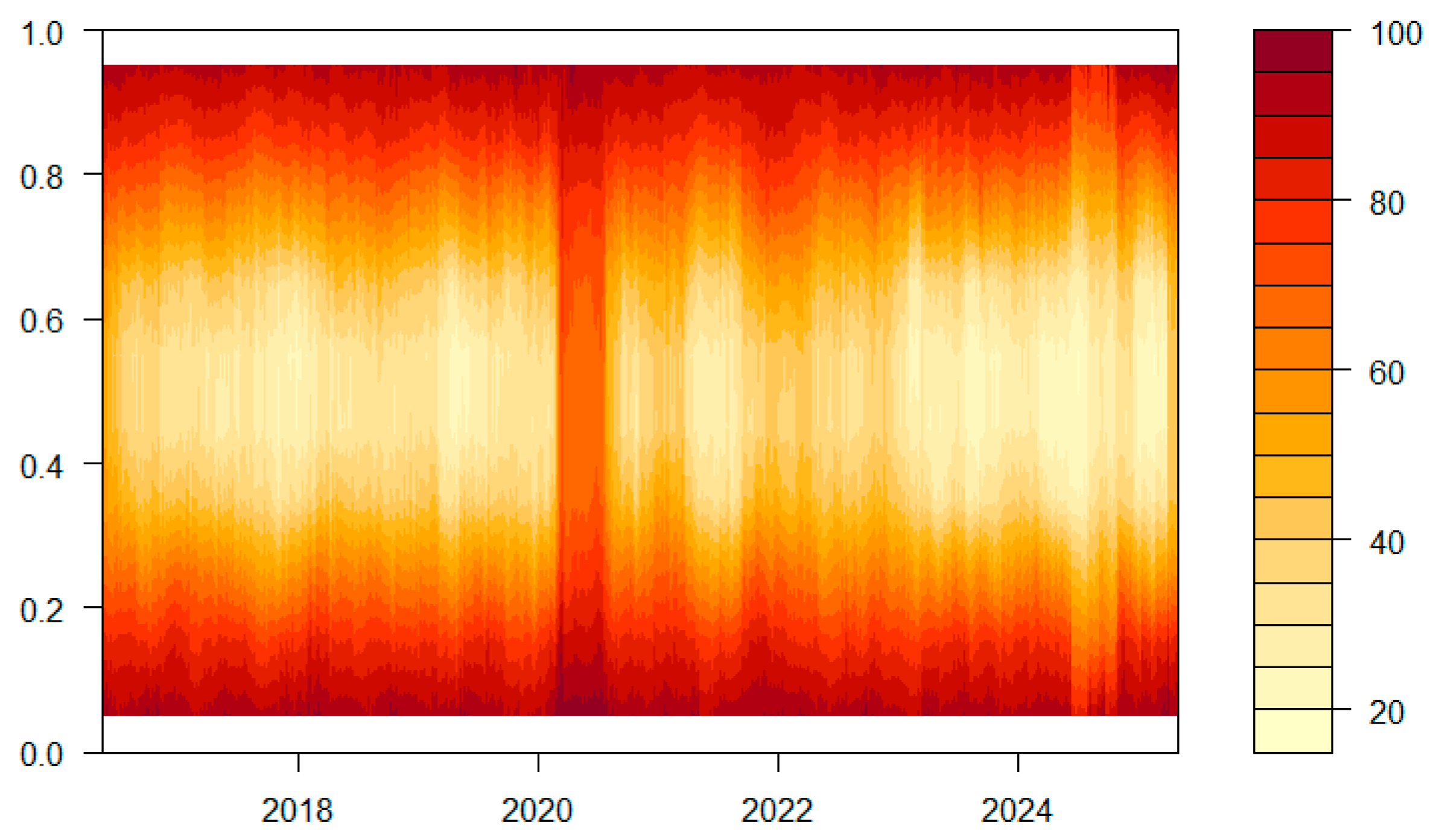

To provide a better understanding of market dynamics, we now analyze connectedness across different quantiles. Starting with the heatmap of the total dynamic connectedness among the BRICS Plus stock market indices and the VIX, which is presented in Figure 7. The horizontal on this figure represents time, while the vertical axis represents quantiles ranging from 0.05 to 0.95 with increments of 1%. Warmer shades on the graph indicate higher levels of connectedness, whereas lighter shades indicate lower levels of connectedness. The results show strong connectedness at both extreme negative (below the 20% quantile) and extreme positive shocks (above the 80% quantile), suggesting a symmetrical pattern. Moreover, the fluctuations in the 50% quantile, which represents the network’s average, show that connectedness remained low before the pandemic, but surged during the COVID-19 outbreak and the Russian-Ukraine conflict, with a decreasing intensity since the beginning of 2023. This underscores how major events intensify market linkages (Snene Manzli & Jeribi, 2024a, 2024b).

Figure 7.

Total dynamic connectedness among the BRICS Plus stocks and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 7.

Total dynamic connectedness among the BRICS Plus stocks and VIX across different quantiles.

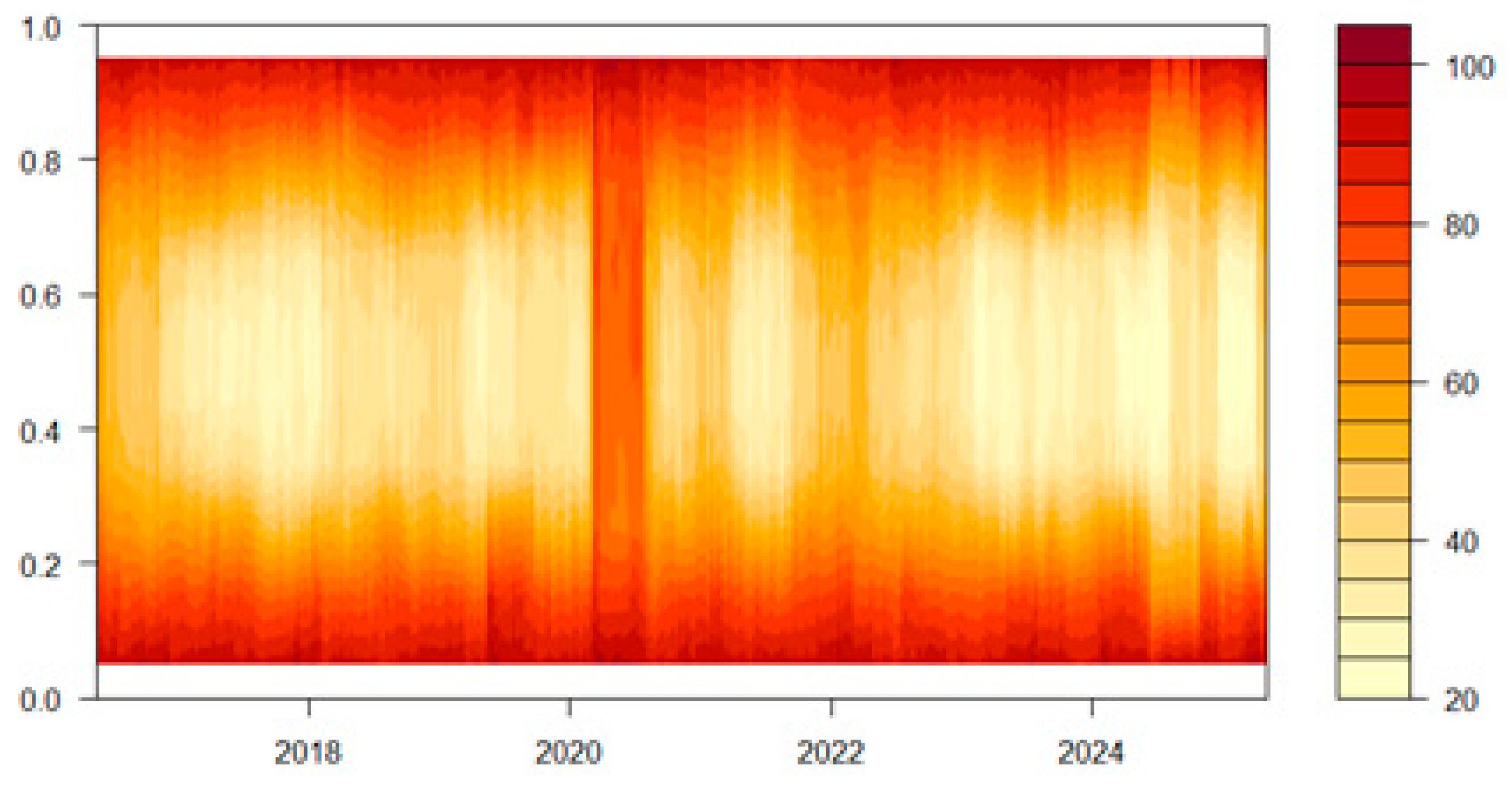

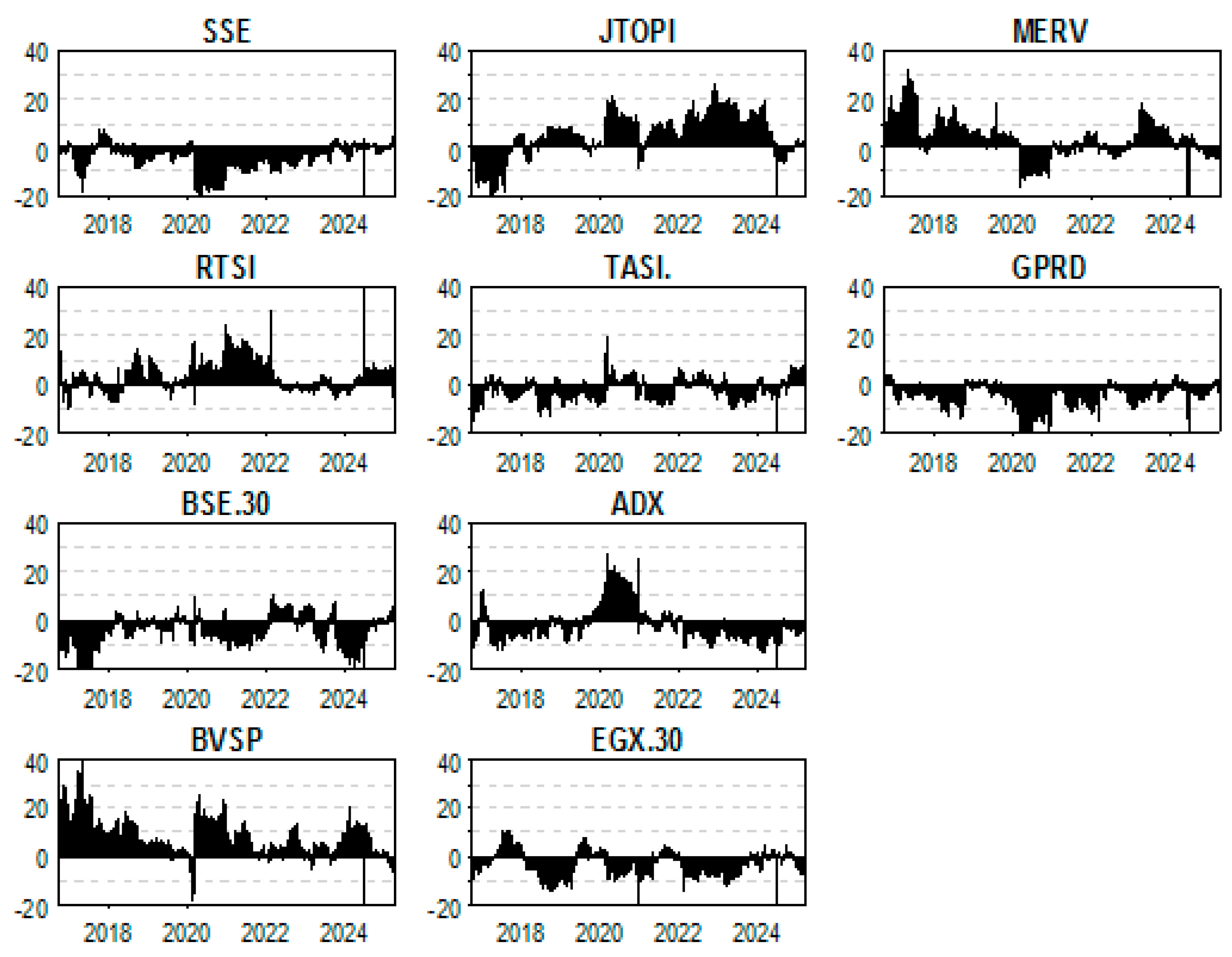

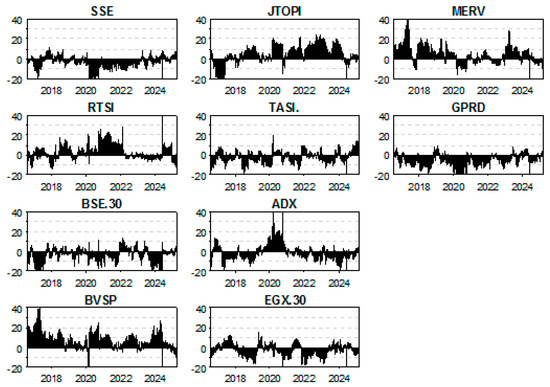

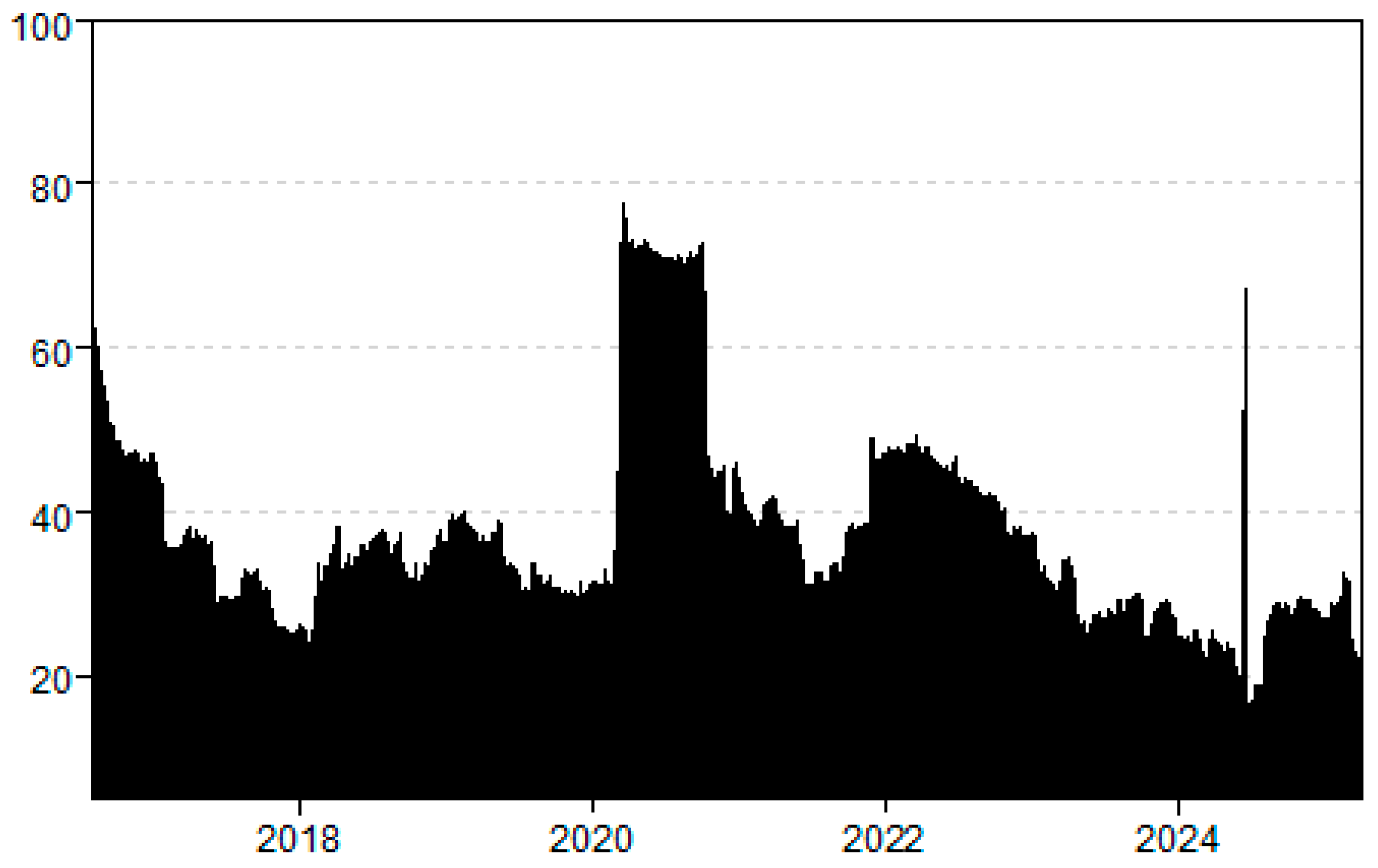

Subsequently, we demonstrate the total net directional connectedness of the different indices along with the VIX across different quantiles in Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16. The main objective through these figures is to comprehend how investors may react to various market scenarios, whether bearish (low quantile), steady (middle quantile), or bullish (high quantile). Red color shades in these figures (corresponding to higher quantiles) indicate that the asset acts as a net transmitter of shocks, while blue color shades (corresponding to lower quantiles) suggest that the asset acts as a net receiver of shocks.

Figure 8 represents the heatmap of the VIX, and it demonstrates substantial variations in the VIX’s role as a transmitter or receiver across time and different market scenarios (different quantiles). During times of financial turmoil, such as the pre-pandemic instability around 2018 and the global market turbulence in 2020, the VIX predominantly acts as a net transmitter of shocks, indicated by intensified red zones across multiple quantiles. This supports the VIX’s performance as a fear gauge, where increased volatility in global financial markets propagates through its influence (Sarwar, 2012; Sarwar & Khan, 2017; Gürsoy, 2020). Moreover, Figure 8 also captures quantile-specific behavior. During extreme market conditions represented by higher quantiles, the VIX’s net transmission is considered strong and more persistent than its net recipient role, suggesting that its influence on other indices intensifies during extreme positive news. Conversely, when observing the lower quantiles, we can see that the VIX shifts to a net receiver role, depicted by patches of blue. This highlights the sensitivity of the VIX to market stress levels, where its connectedness structure fluctuates based on the magnitude of market disruptions. In addition, alternating red and blue patterns indicate cyclic behavior, reflecting shifts between net transmitting and net receiving as market conditions evolve. These outcomes indicate the importance of quantile-based analysis in examining non-linear dependencies and reveal the conditional nature of the VIX’s market influence, particularly during times of heightened market instability.

Figure 8.

Total net directional connectedness for the VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 8.

Total net directional connectedness for the VIX across different quantiles.

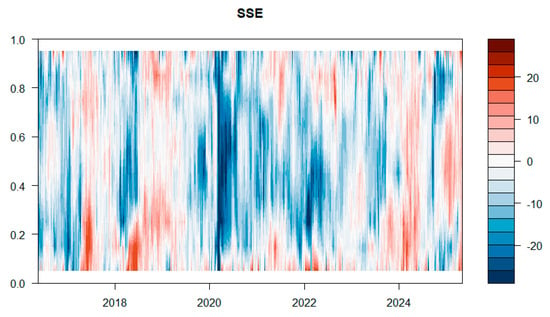

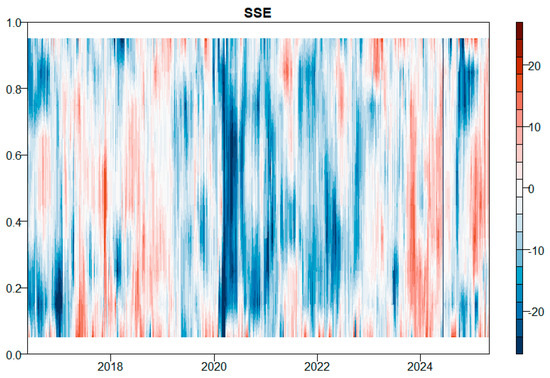

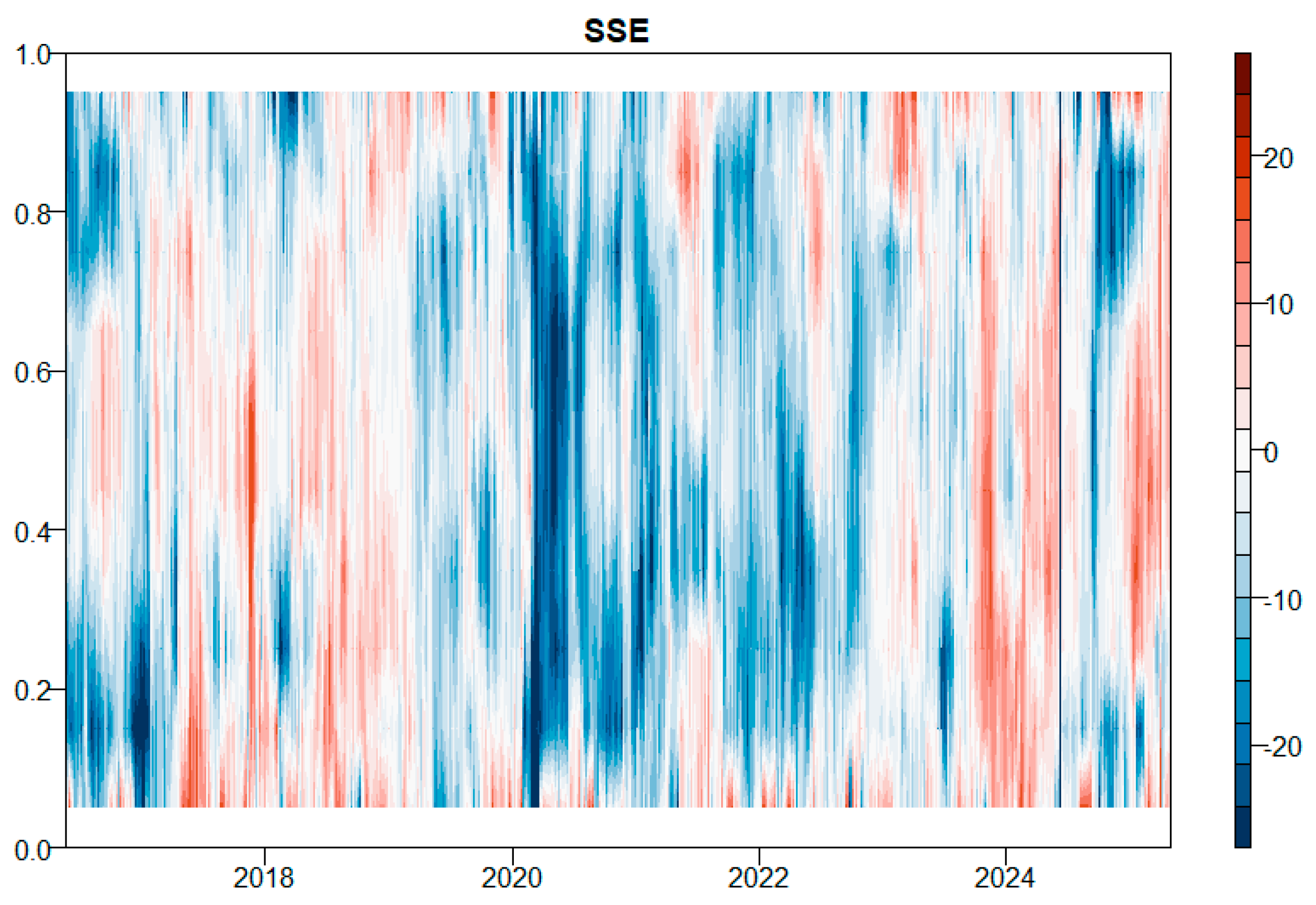

Regarding the BRICS Plus stock market indices, the results show that the Chinese stock (SSE) (Figure 9) mostly acts as a net receiver of shocks, especially during the periods related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian-Ukraine conflict, as indicated by the pronounced blue regions at the median quantile. This indicates that during times of financial turmoil, the Chinese stock market can absorb volatility spillovers from other markets. Conversely, during extreme bearish and bullish market conditions (presented in the lower and upper quantiles), the SSE often acts mostly as a net transmitter of shocks, as indicated by dominant red regions. This implies that it actively transmits shocks to the rest of the markets during extreme market conditions.

Figure 9.

Total net directional connectedness for the Chinese stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 9.

Total net directional connectedness for the Chinese stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

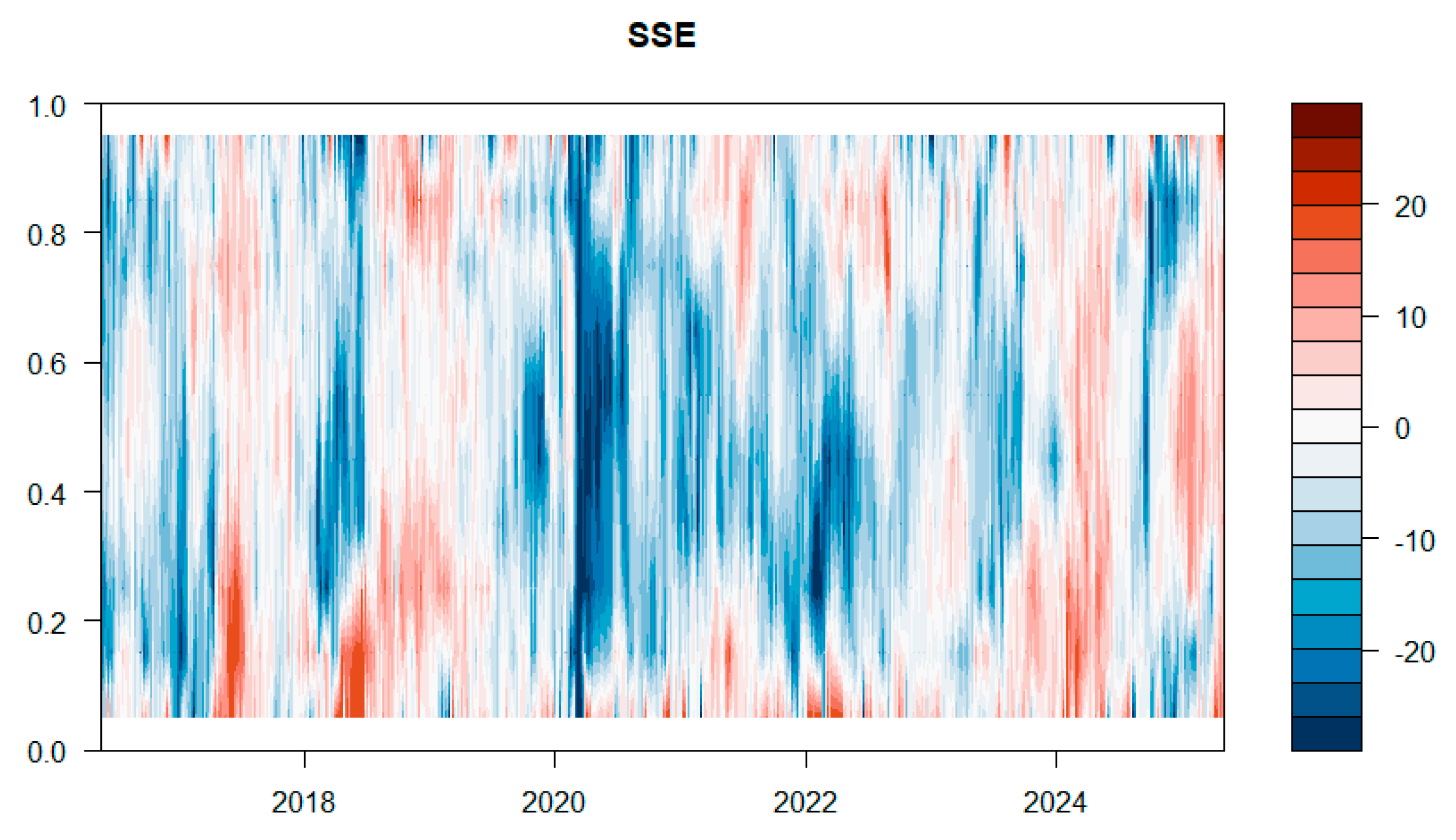

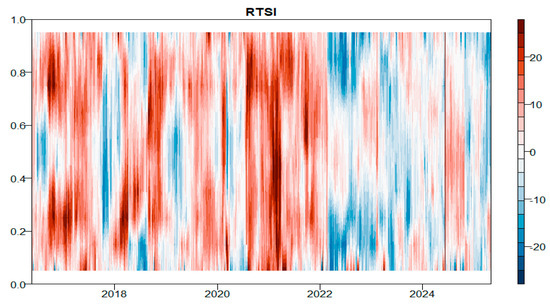

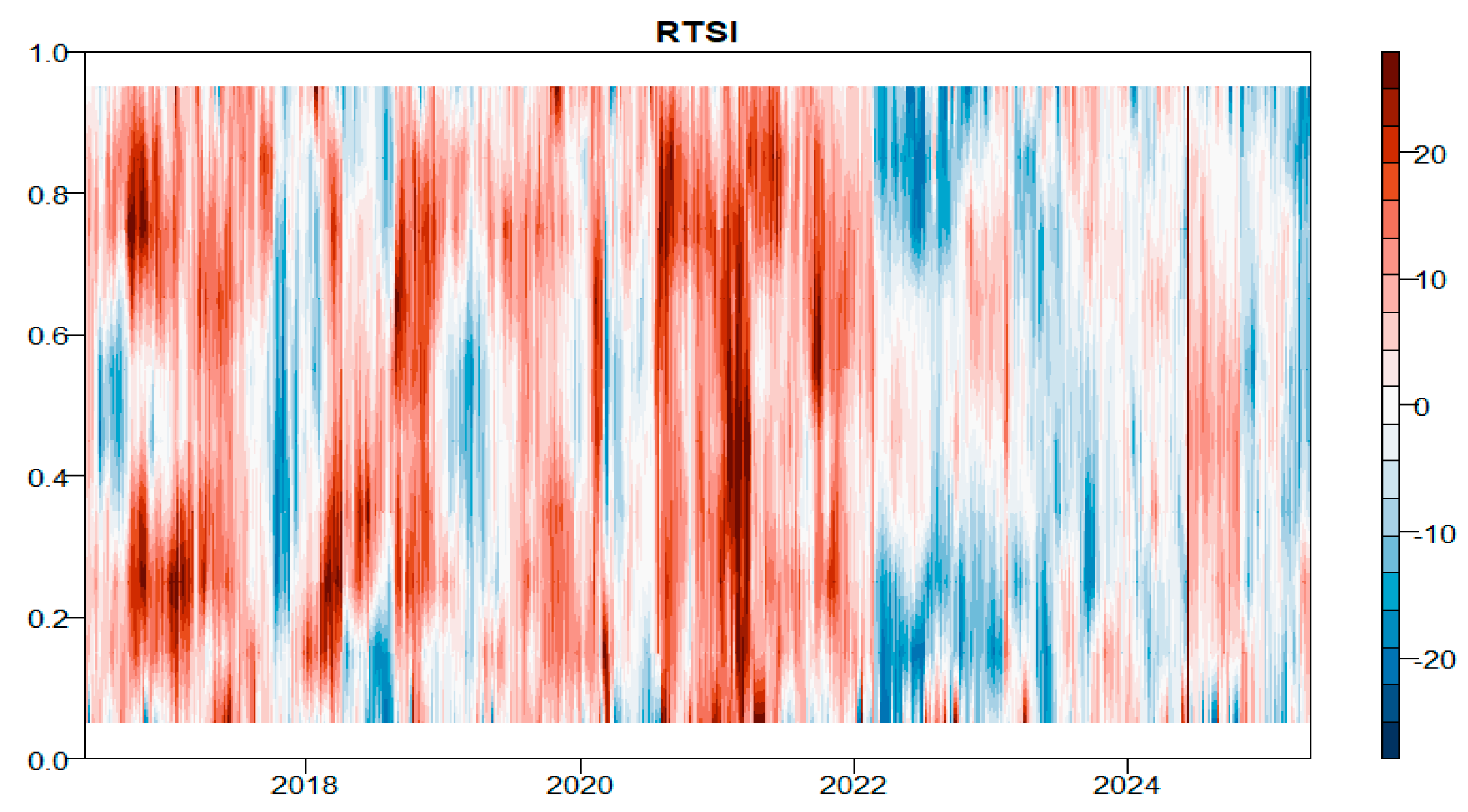

Figure 10 shows that the Russian (RTSI) stock index acts mostly as a major net transmitter of shocks, especially during the period ranging from 2019 to 2022, where red shades dominate the median and extreme quantiles. However, during the period marked by the geopolitical crisis, particularly the 2022 Russian-Ukraine conflict, the RTSI shifts to a net shock receiver, especially in the lower and upper quantiles, as indicated by the dark blue regions. The index’s transition to a major shock receiver during the war, especially given its affiliation with a country directly involved in the conflict, underscores its resilience and potential utility as a hedging instrument during market downturns.

Figure 10.

Total net directional connectedness for the Russian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 10.

Total net directional connectedness for the Russian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

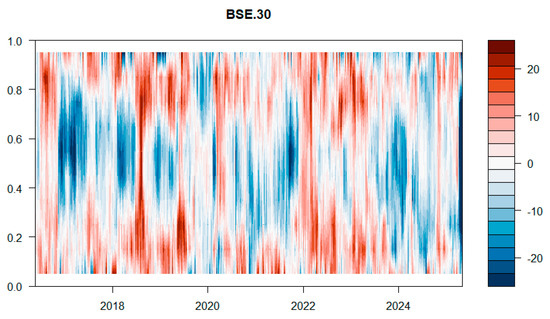

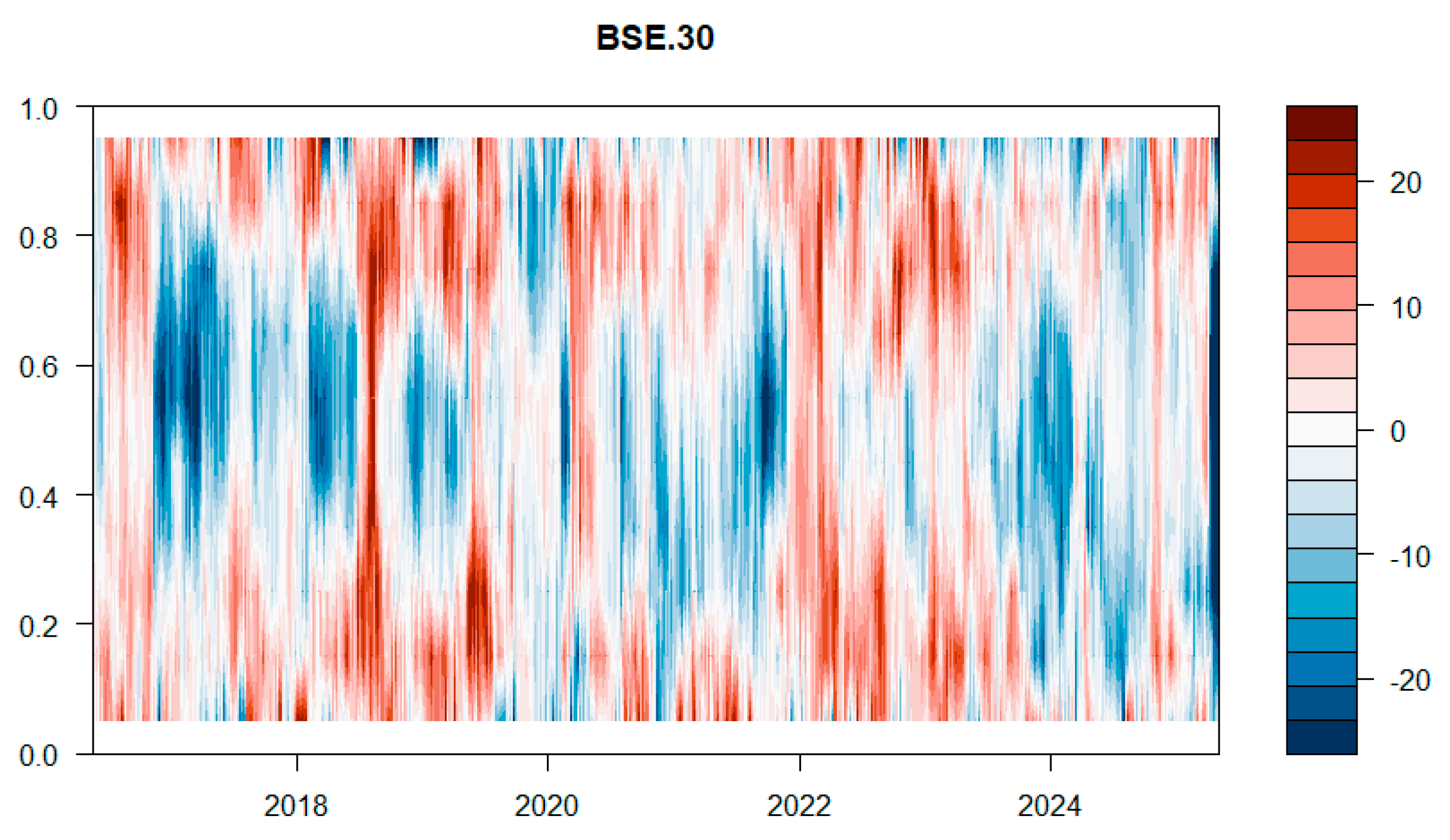

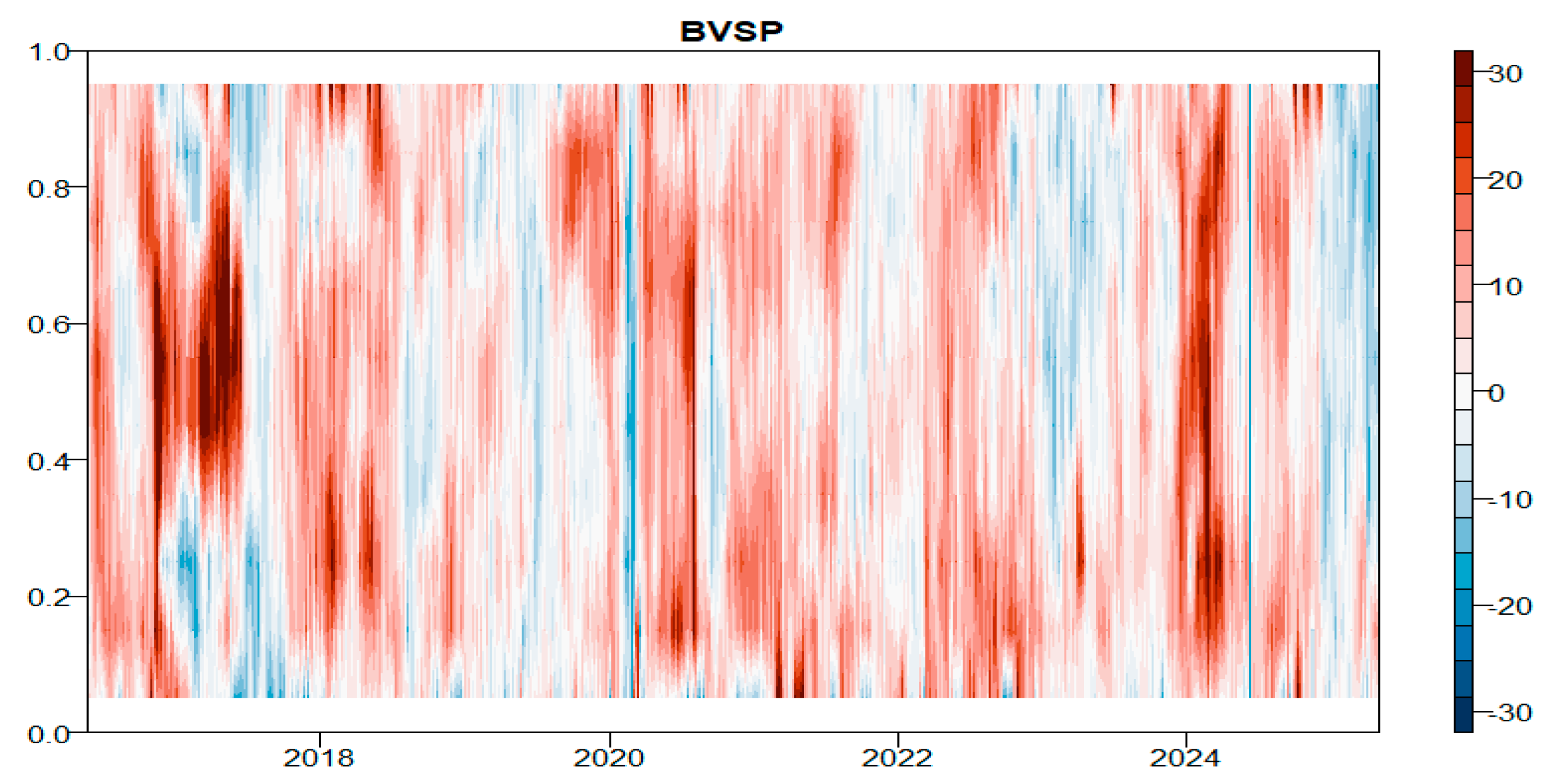

Regarding the Indian stock index (BSE.30), Figure 11 reveals changeable and dynamic behavior regarding this stock, shifting between net shock receiver (blue regions) and net shock transmitter (red regions) across time and quantiles. These fluctuations indicate that the BSE.30 index does not consistently hold a dominant role in volatility transmission, but instead it varies between being a net transmitter and receiver depending on the different market conditions. For instance, periods of heightened instability, particularly the pre-pandemic uncertainty around 2018, the COVID-19 health crisis, and the 2022 Russian-Ukraine conflict, are characterized by deeper and more persistent red shades, especially at extreme positive and negative quantiles. This figure highlights the index’s increased effect during extreme market situations. Moreover, the detected quantile-specific spillover intensification implies that as market volatility rises, so does the BSE.30’s shock transmission role, potentially reflecting the sensitivity of India’s financial system to global risks.

Figure 11.

Total net directional connectedness for the Indian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 11.

Total net directional connectedness for the Indian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

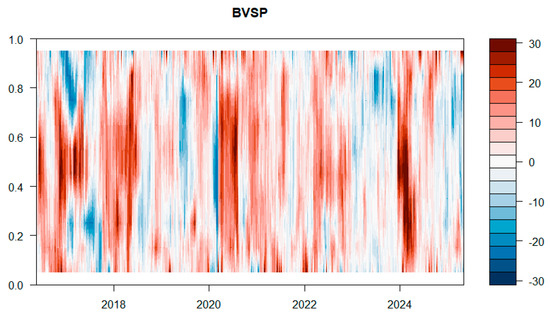

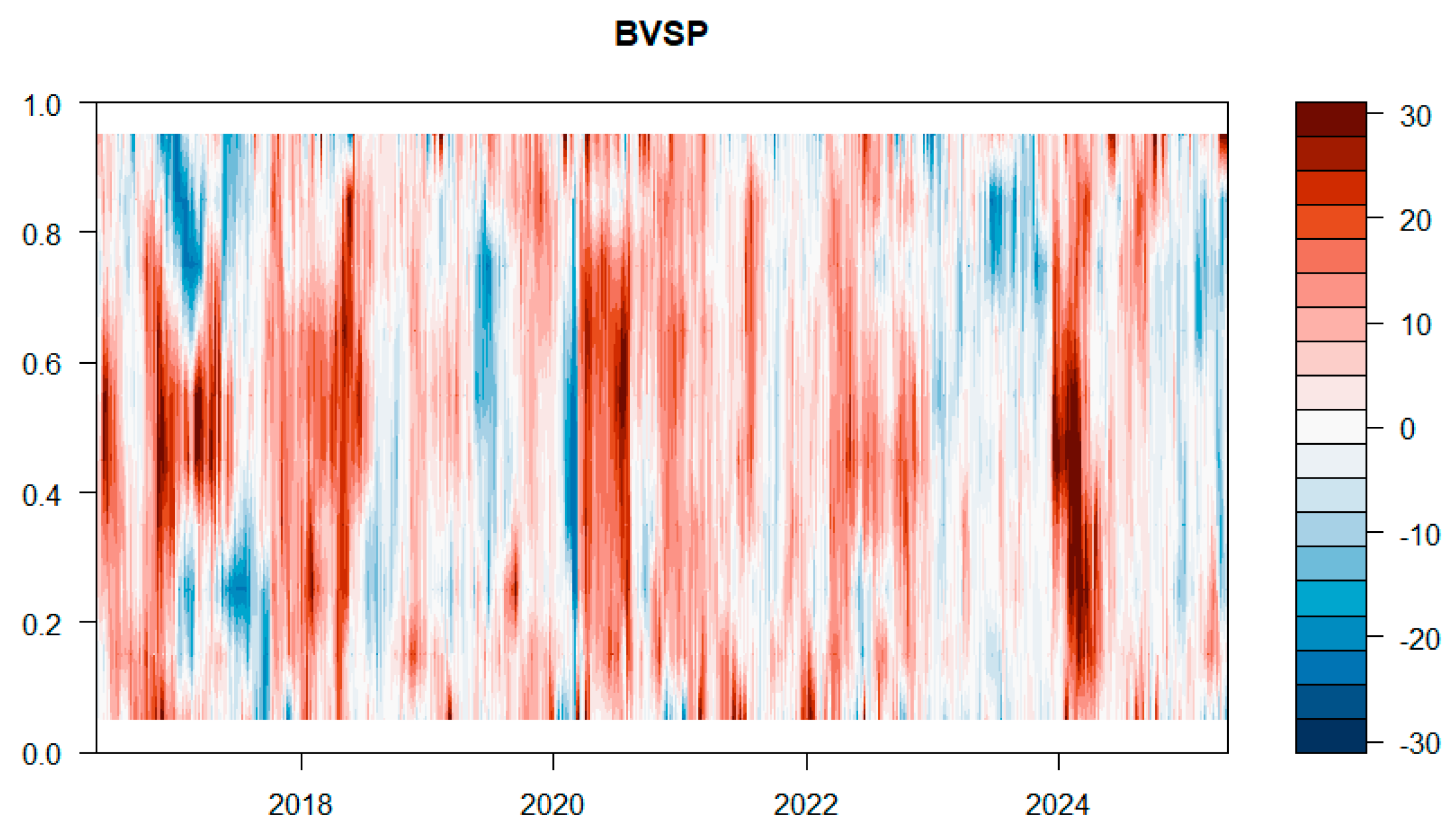

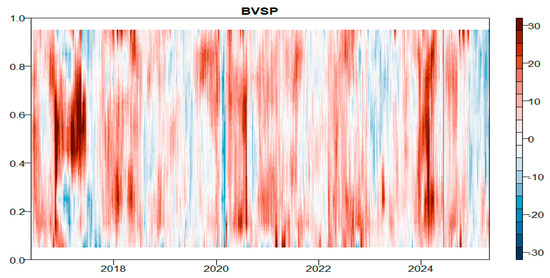

Moreover, the BVSP index (Figure 12) exhibits a significant dominance of red-colored regions from 2018 to 2024, indicating its strong capacity as a net shock transmitter during the entire period. This behavior is also evident in higher and lower quantiles, where the red zones are both intense and continuous, reflecting the significant impact of extreme market situations on Brazil’s behavior. Nevertheless, brief occurrences of blue regions at the lower and higher quantiles, particularly during periods of stability, indicate occasional phases where the BVSP acts as a net receiver of volatility, suggesting a conditional and state-dependent impact based on the overall market scenario.

Figure 12.

Total net directional connectedness for the Brazilian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 12.

Total net directional connectedness for the Brazilian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

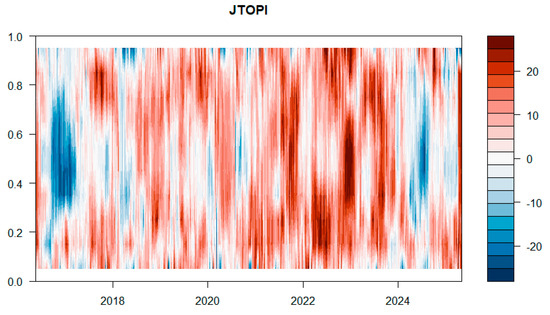

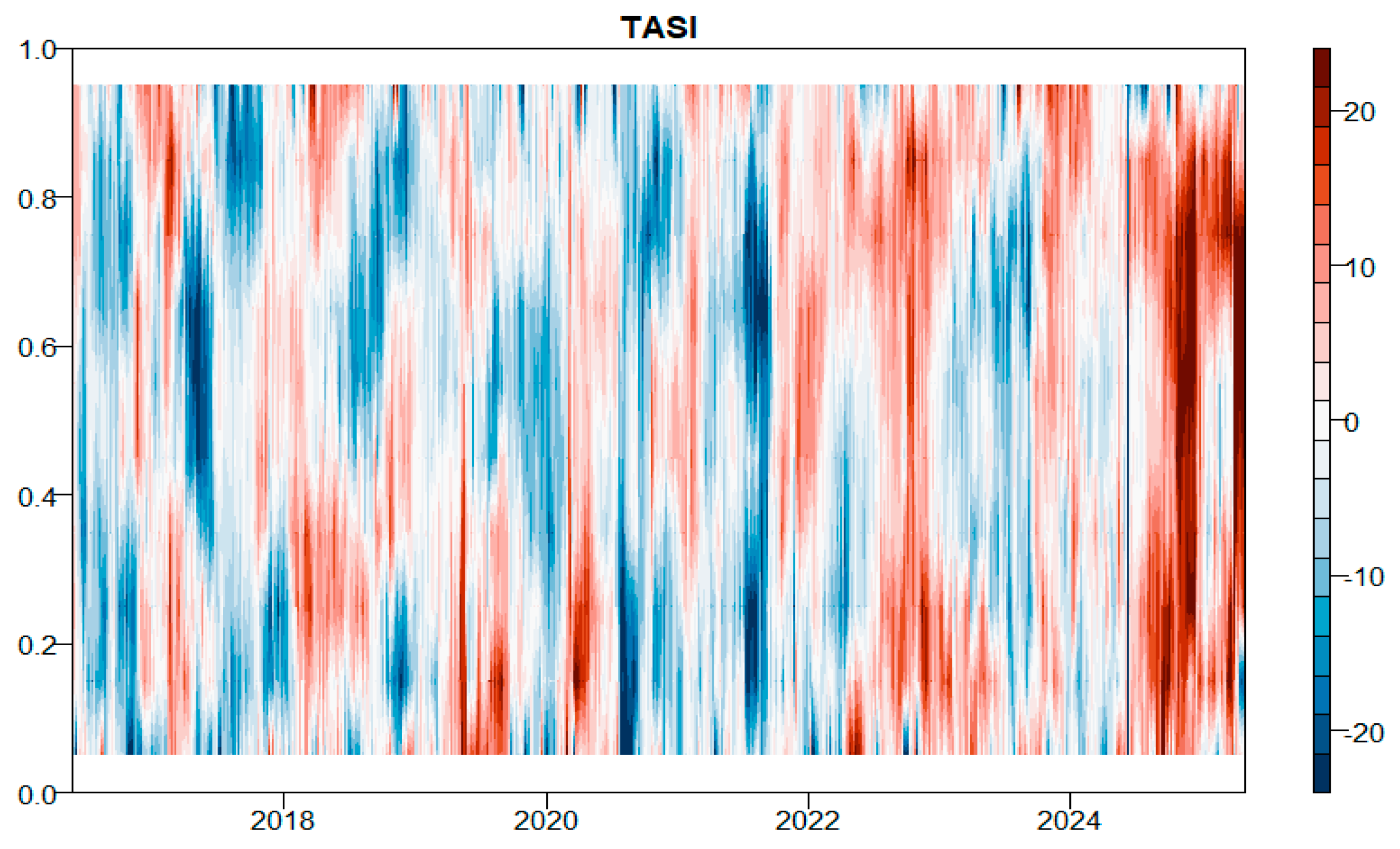

Figure 13 shows that the South African (JTOPI) stock index primarily acts as a strong net transmitter of shocks, which aligns with the dominance of the red color shades before, during, and after periods of financial stress, such as before and during COVID-19, the Russian-Ukraine conflict, and the SVB collapse. This situation highlights the risky and unstable behavior of the JTOPI stock index during periods of calm and crises.

Figure 13.

Total net directional connectedness for the South African stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 13.

Total net directional connectedness for the South African stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

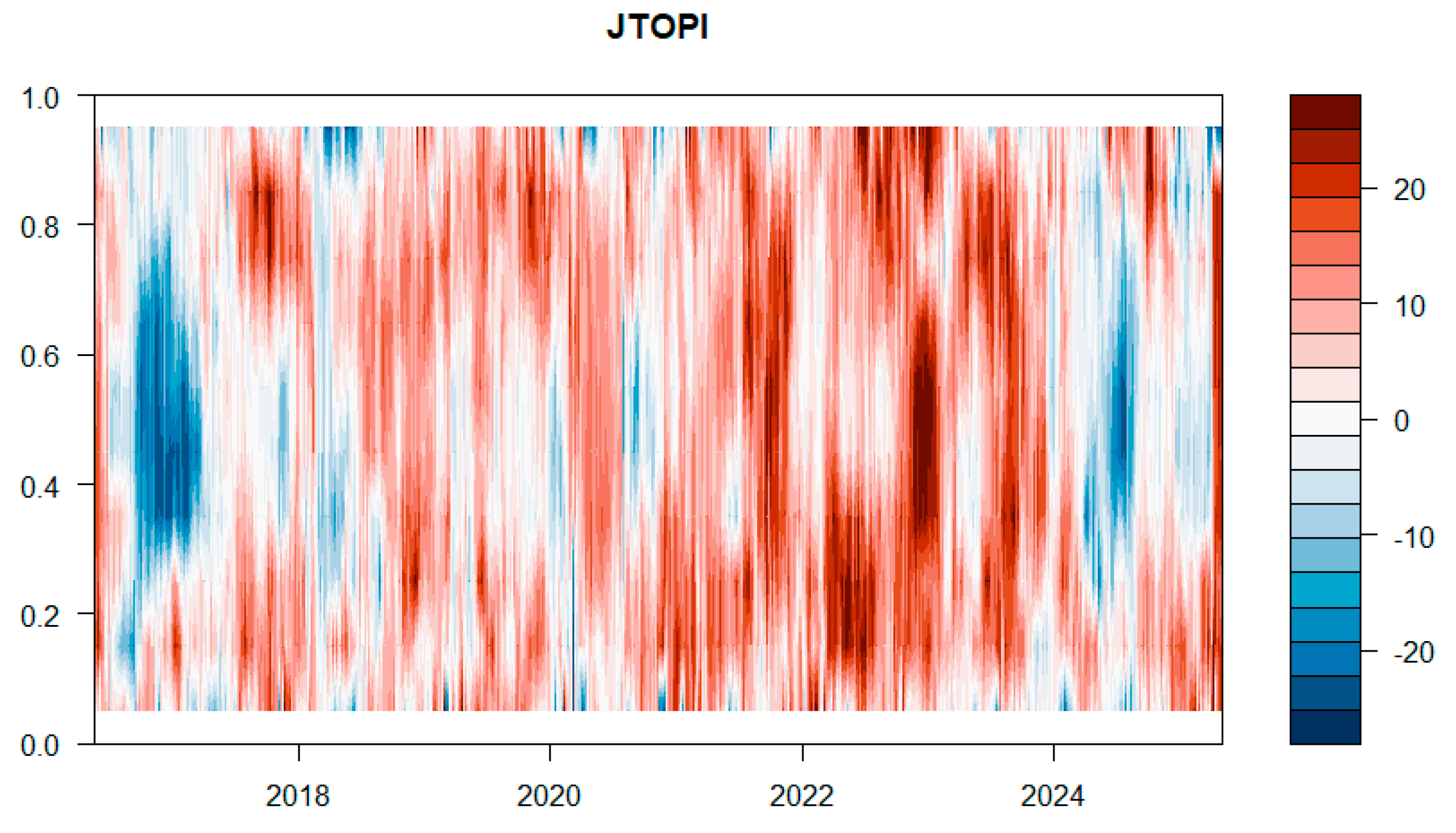

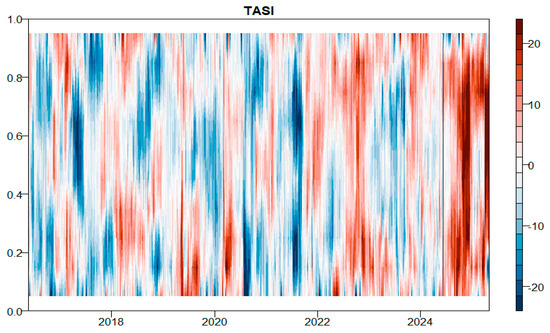

As for the Saudi Arabian (TASI) stock index (Figure 14), it shifts between a net transmitter and a net receiver of shocks during the entire period, depending on market conditions, and this situation is observed at the upper, median, and lower quantiles. During periods of market turmoil, we can see that TASI acts as a strong net transmitter of shocks, especially in higher quantiles, which can be explained by its sensitivity to oil price movements and regional economic uncertainties. However, in more stable periods, TASI shifts to a net recipient of shocks, highlighting its dual nature based on market conditions.

Figure 14.

Total net directional connectedness for the Saudi Arabian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 14.

Total net directional connectedness for the Saudi Arabian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

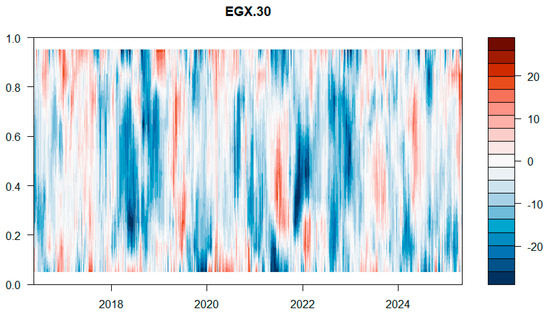

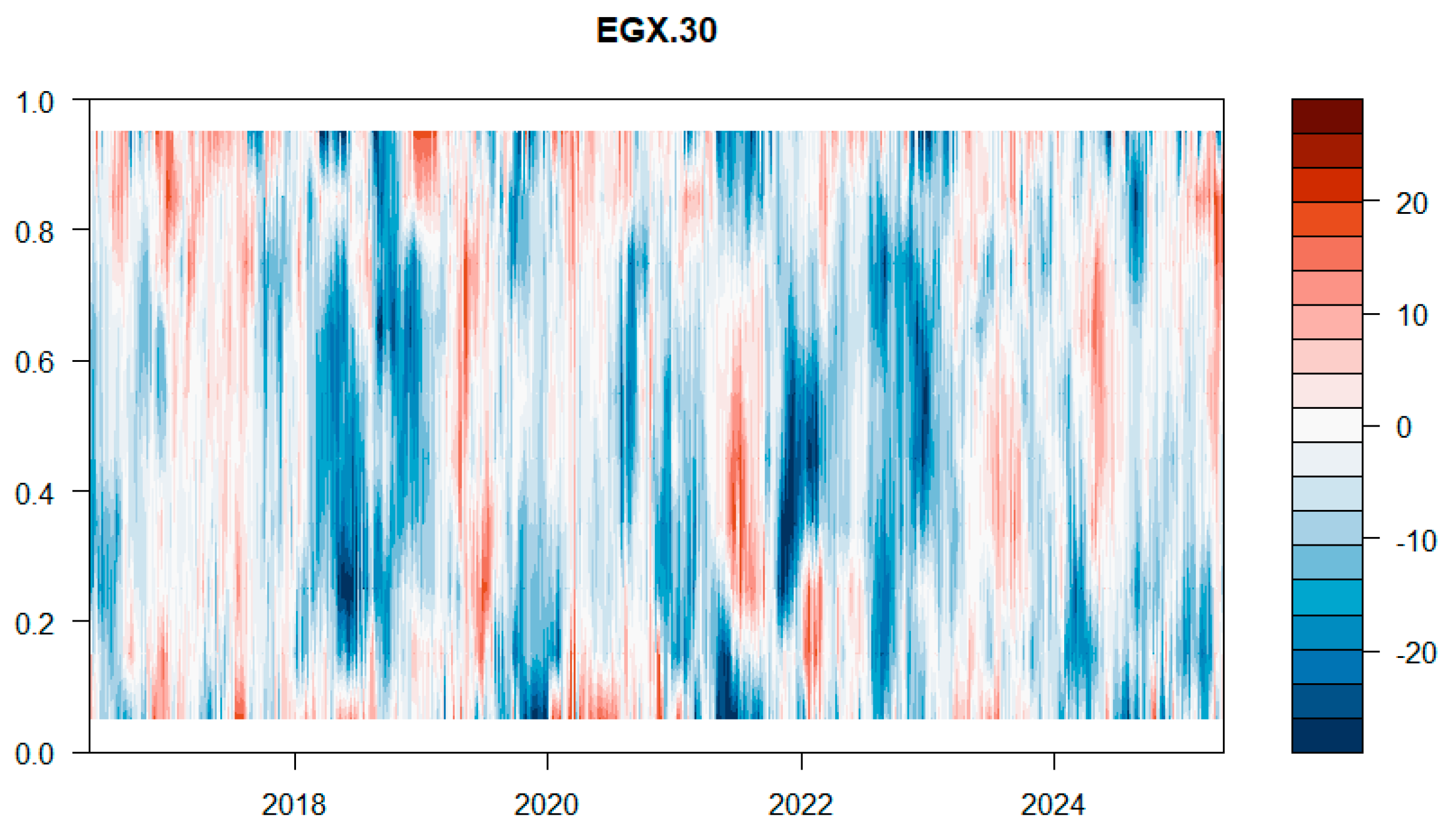

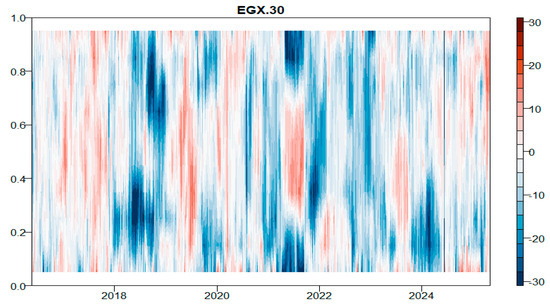

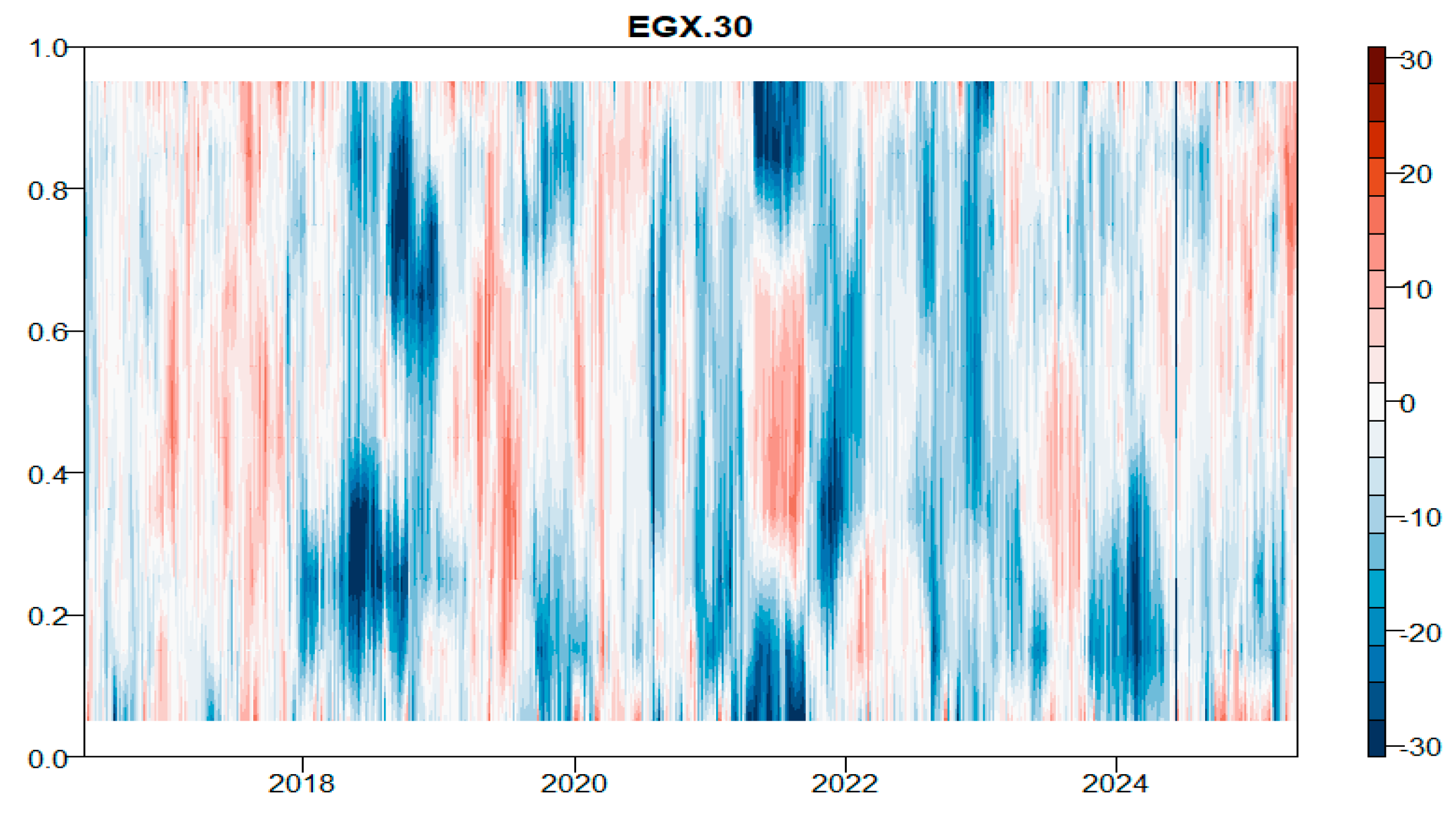

The Egyptian (EGX.30) stock index (Figure 15) primarily acts as a net receiver of shock, given the dominance of the blue color regions during the entire period and across different quantiles. In addition, the index’s net transmission behavior is considered limited and of brief duration.

Figure 15.

Total net directional connectedness for the Egyptian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 15.

Total net directional connectedness for the Egyptian stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

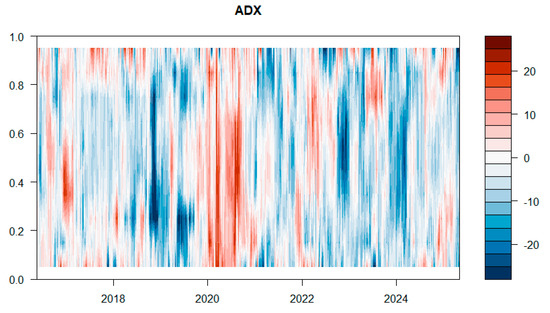

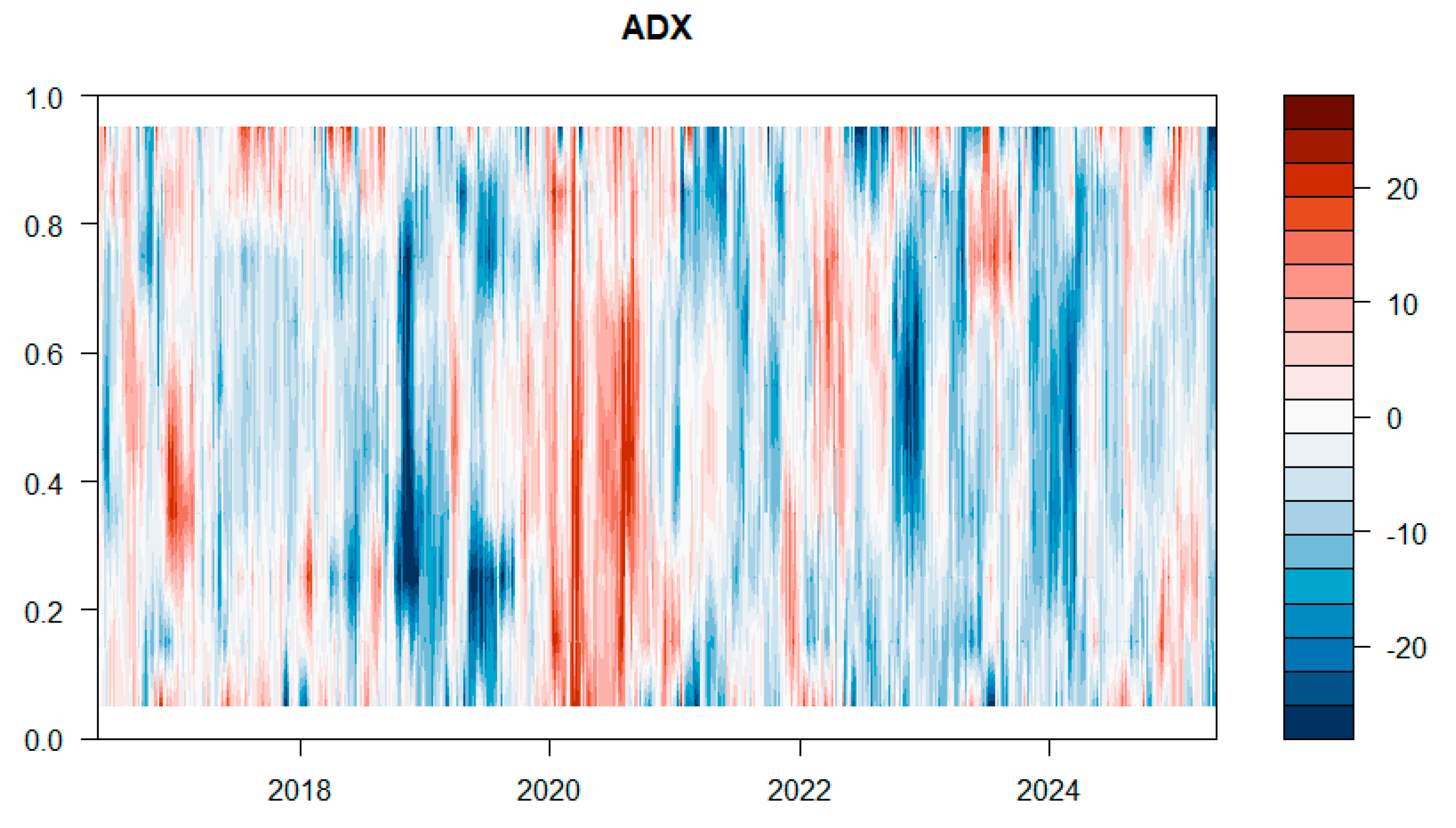

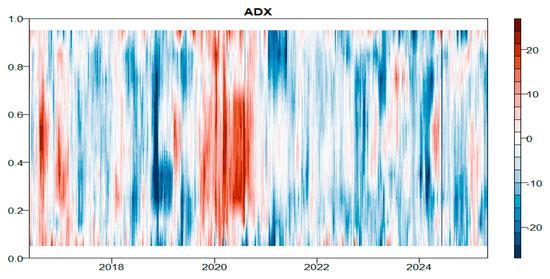

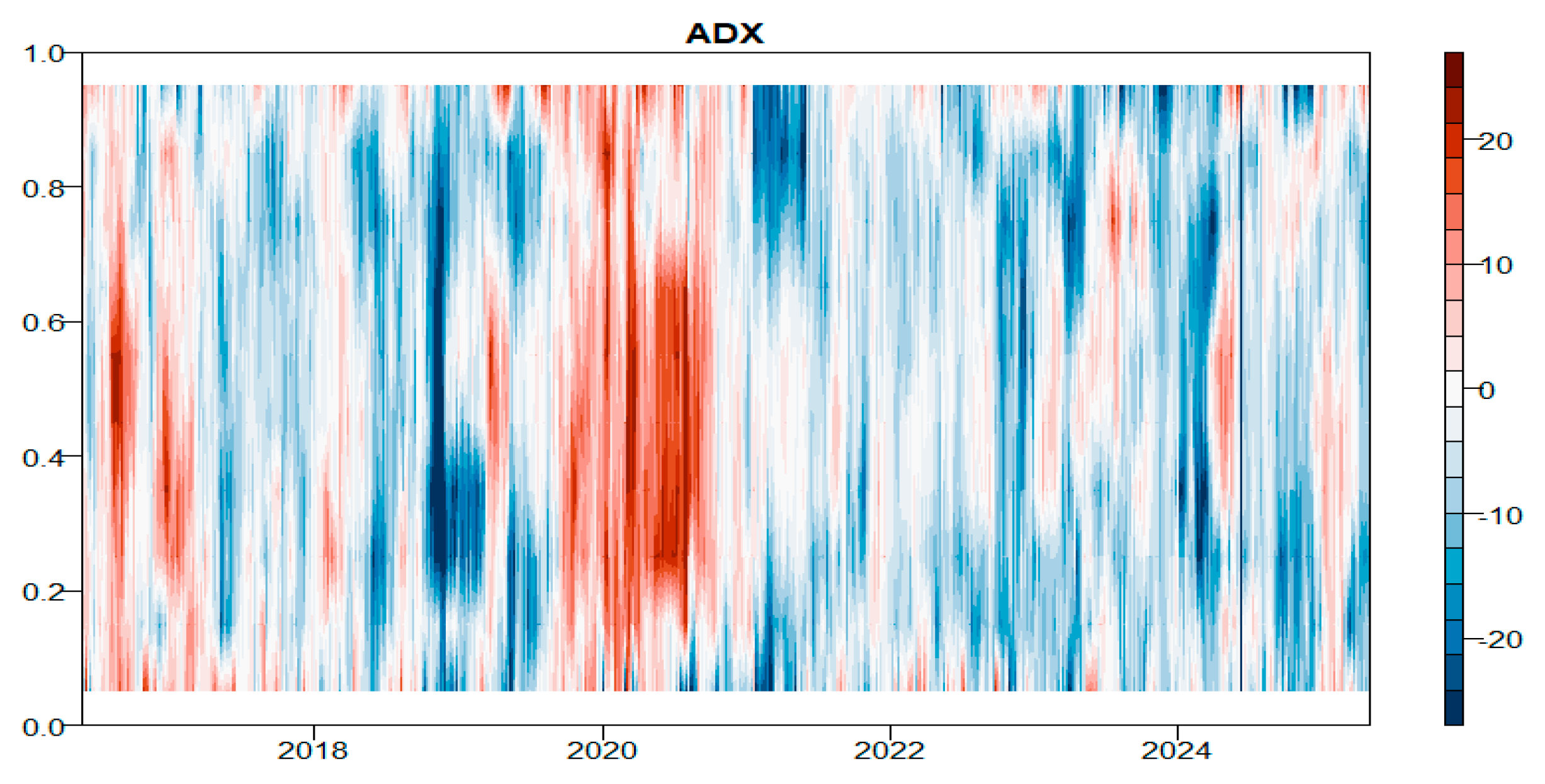

As for United Arab Emirates (ADX) stock (Figure 16), it displays a more resilient and balanced connectedness profile compared to its regional peers. While it acts as a net transmitter during crises, its spillover effects are less extreme and even considered weak, which may be due to the UAE’s diversified economic structure. In lower quantiles, ADX demonstrates neutral or even net receiver behavior. The index’s mid-quantile behavior further indicates a moderating effect, where it neither strongly transmits nor receives shocks, suggesting its ability as a stabilizing tool in regional markets.

Figure 16.

Total net directional connectedness for the United Arab Emirates stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

Figure 16.

Total net directional connectedness for the United Arab Emirates stock index and VIX across different quantiles.

4.2.2. Total and Net Dynamic Connectedness Between BRICS Plus and GPRD Across Different Quantiles

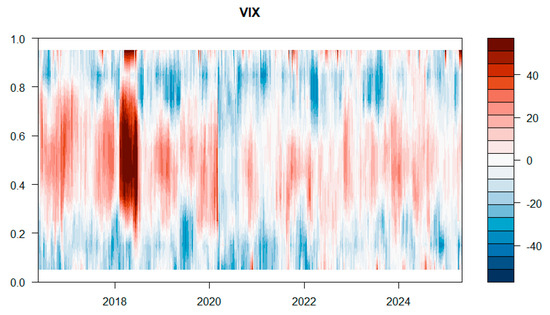

Figure 17 illustrates the total dynamic connectedness between the BRICS Plus stock indices and the GPRD. The outcome illustrates meaningful patterns in the distribution of market connectedness across different quantiles. For instance, the middle quantiles (between 0.4 and 0.6) consistently demonstrate low connectedness, as shown by the light color band, which suggests that median levels of market connections remain low throughout most of the sample period. In contrast, extreme quantiles (both upper and lower quantiles) exhibit significantly stronger connectedness, indicating that extreme shocks significantly impact the market distribution.

Figure 17.

Total dynamic connectedness among the BRICS Plus stocks and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 17.

Total dynamic connectedness among the BRICS Plus stocks and GPRD across different quantiles.

Moreover, a pronounced vertical band of strong connectedness appears around early 2020, corresponding to the COVID-19 outbreak. During this period, connectedness intensified across nearly all quantiles, reflecting the significant impact and aggressive nature of the pandemic on global markets. Following this health crisis, connectedness weakened in 2021 across multiple quantiles, signifying a return to more normalized market conditions, while it re-increased again at the start of 2022, coinciding with the start of the Russian-Ukraine conflict. These situations underscore how major events intensify market connectedness (Snene Manzli & Jeribi, 2024a, 2024b).

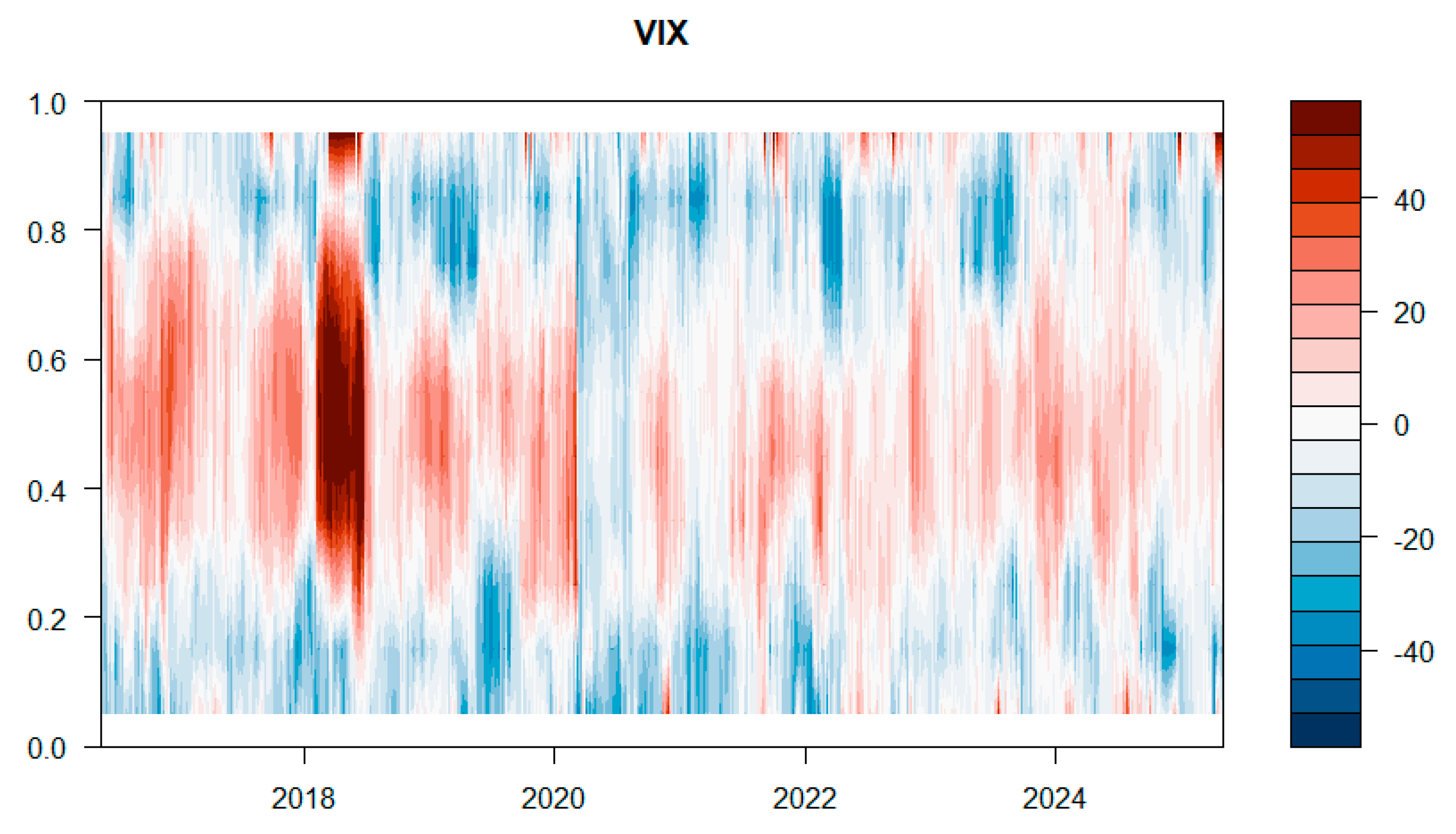

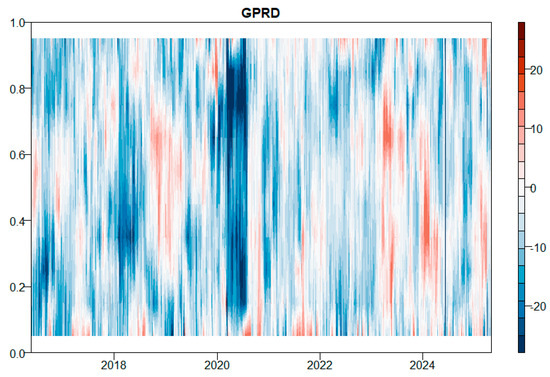

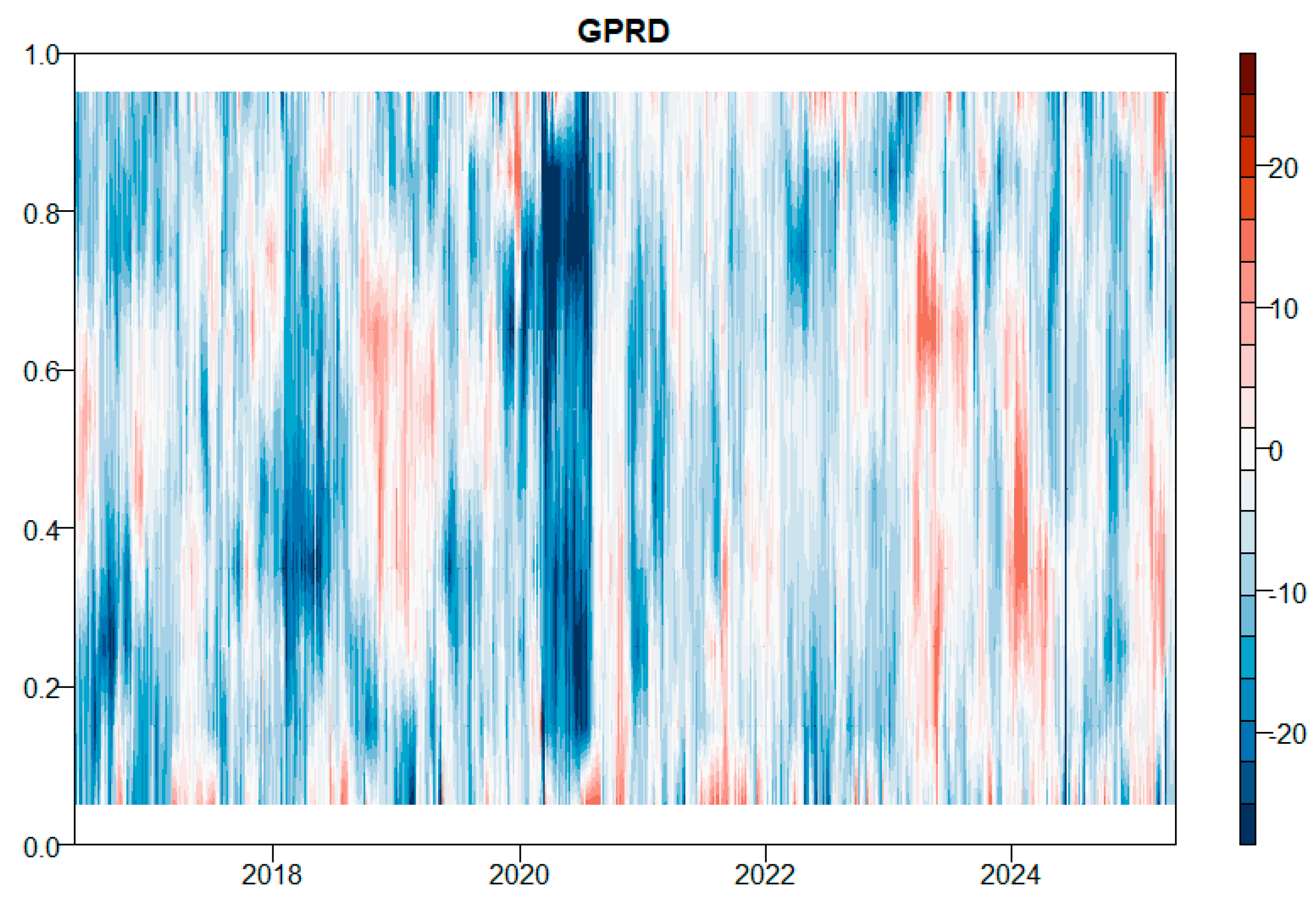

In the same way, we next demonstrate the total net directional connectedness of the different indices along with the GPRD across different quantiles in Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25 and Figure 26. As stated above, red shades in these figures indicate that the asset acts as a net transmitter of shocks, while blue shades suggest that the asset acts as a net receiver of shocks.

In contrast to the VIX, Figure 18 demonstrates that the GPRD acts mostly as a net receiver of shocks, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the index maintained this behavior for the rest of the period but with lower degrees (lighter blue shades), particularly during the war and other crises. These findings are in line with those of Shaik et al. (2023), U. Shahzad et al. (2023), and L. Liu et al. (2025), who supported the importance of this index during recent global disturbances, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian-Ukraine conflict, and the escalating U.S.-China trade war.

Figure 18.

Total net directional connectedness for the GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 18.

Total net directional connectedness for the GPRD across different quantiles.

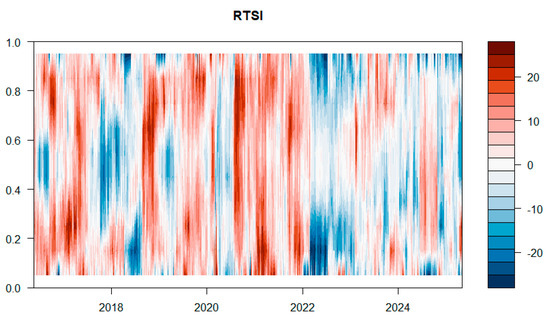

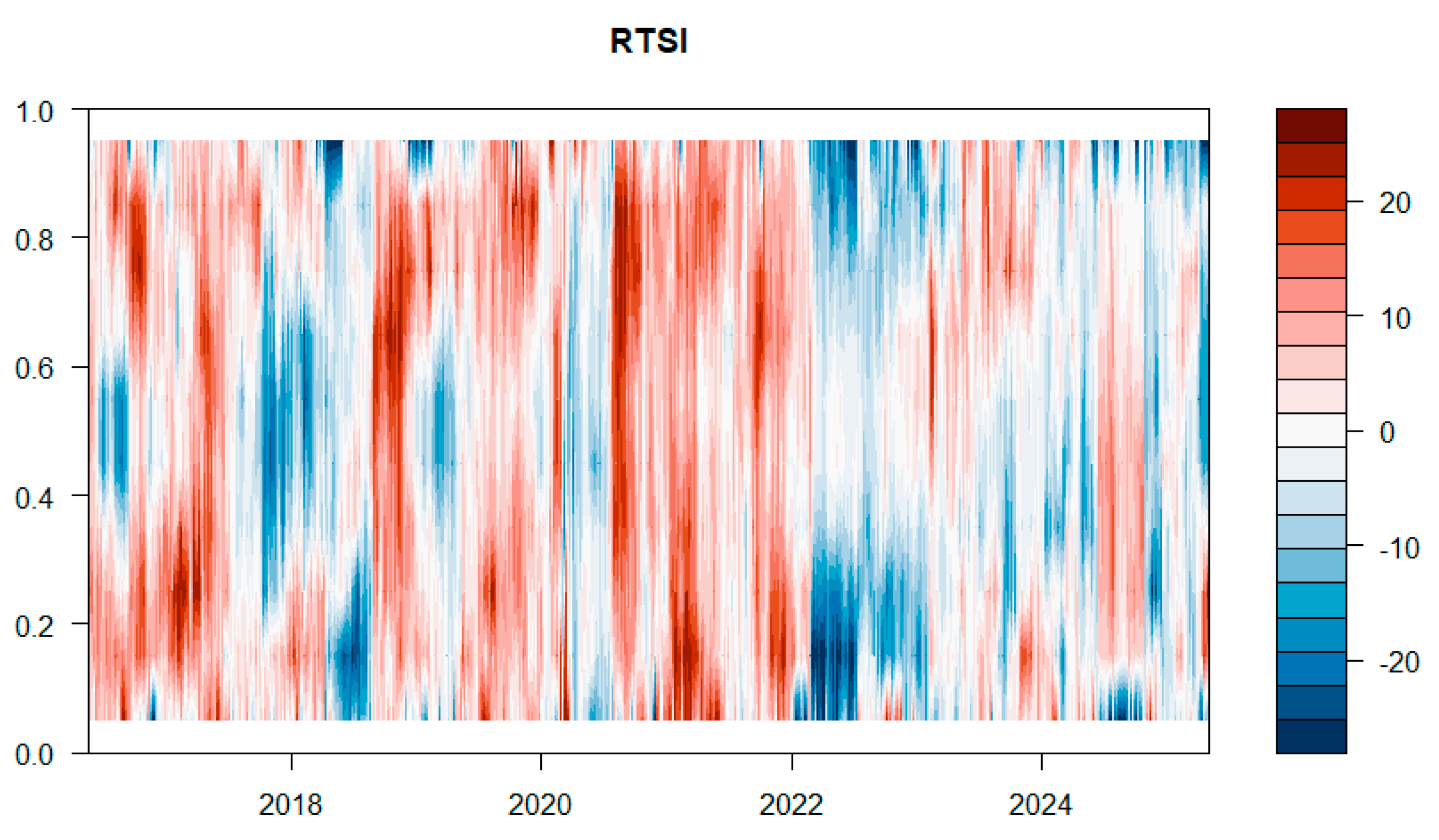

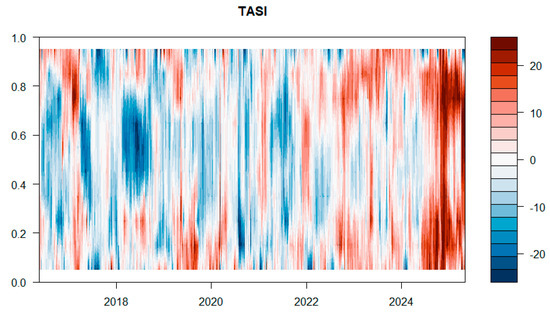

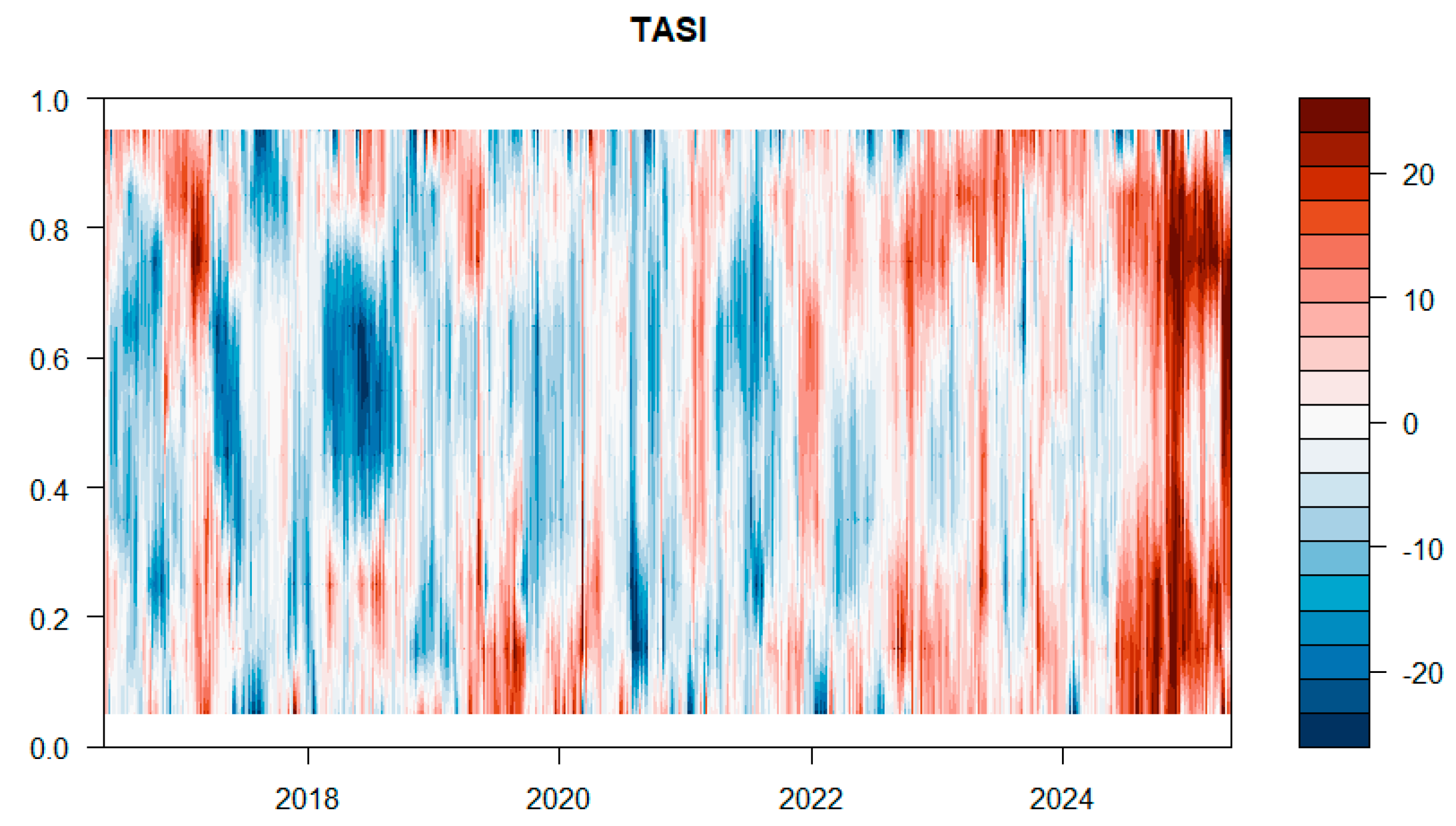

Regarding the results of the total net directional connectedness of the BRICS Plus stock market indices, which are represented in Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25 and Figure 26, they are considered similar to those observed above in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16.

Figure 19.

Total net directional connectedness for the Egyptian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 19.

Total net directional connectedness for the Egyptian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 20.

Total net directional connectedness for the United Arab Emirates stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 20.

Total net directional connectedness for the United Arab Emirates stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 21.

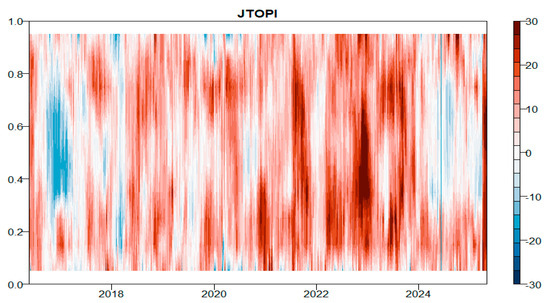

Total net directional connectedness for the Saudi Arabian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 21.

Total net directional connectedness for the Saudi Arabian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

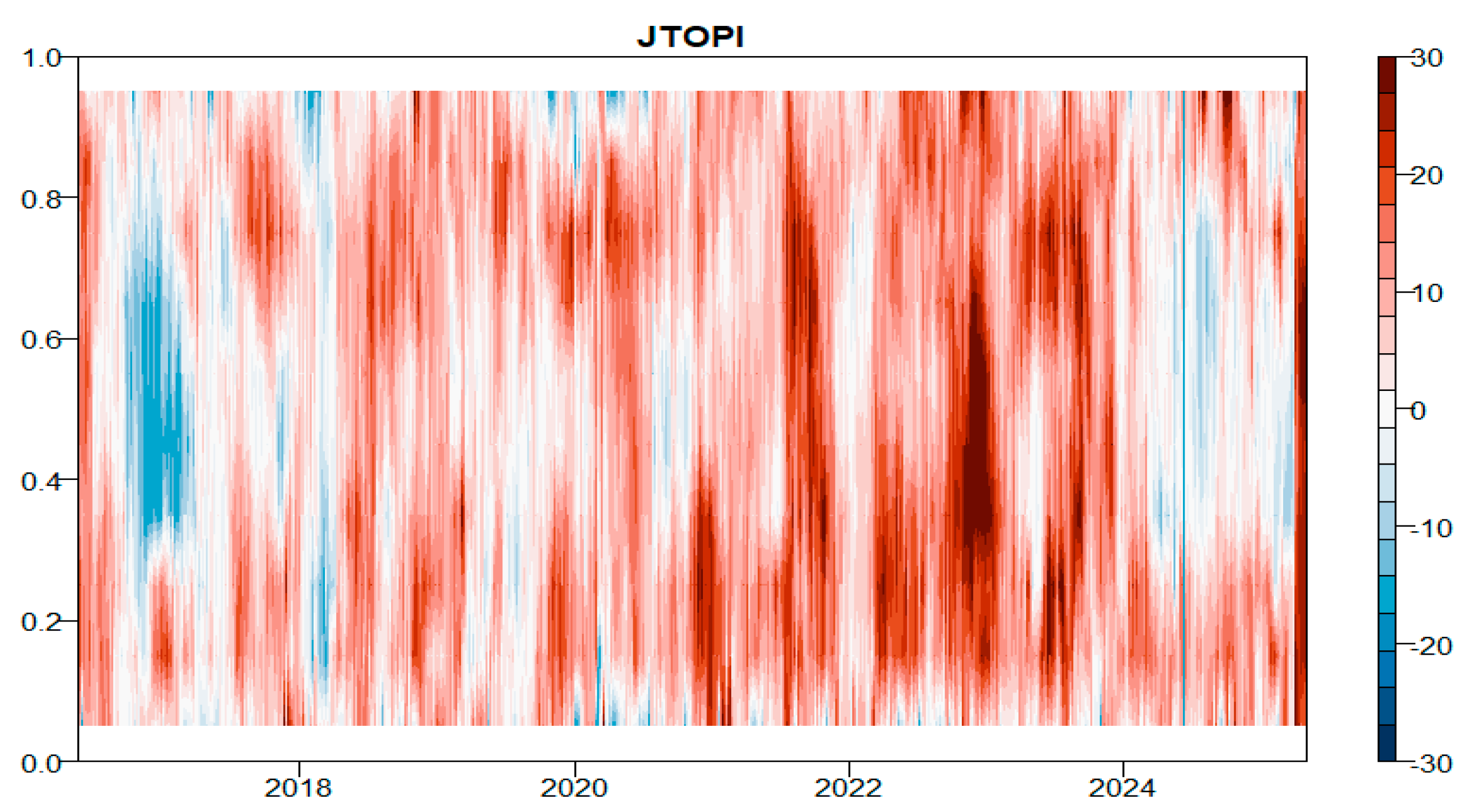

Figure 22.

Total net directional connectedness for the South African stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 22.

Total net directional connectedness for the South African stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

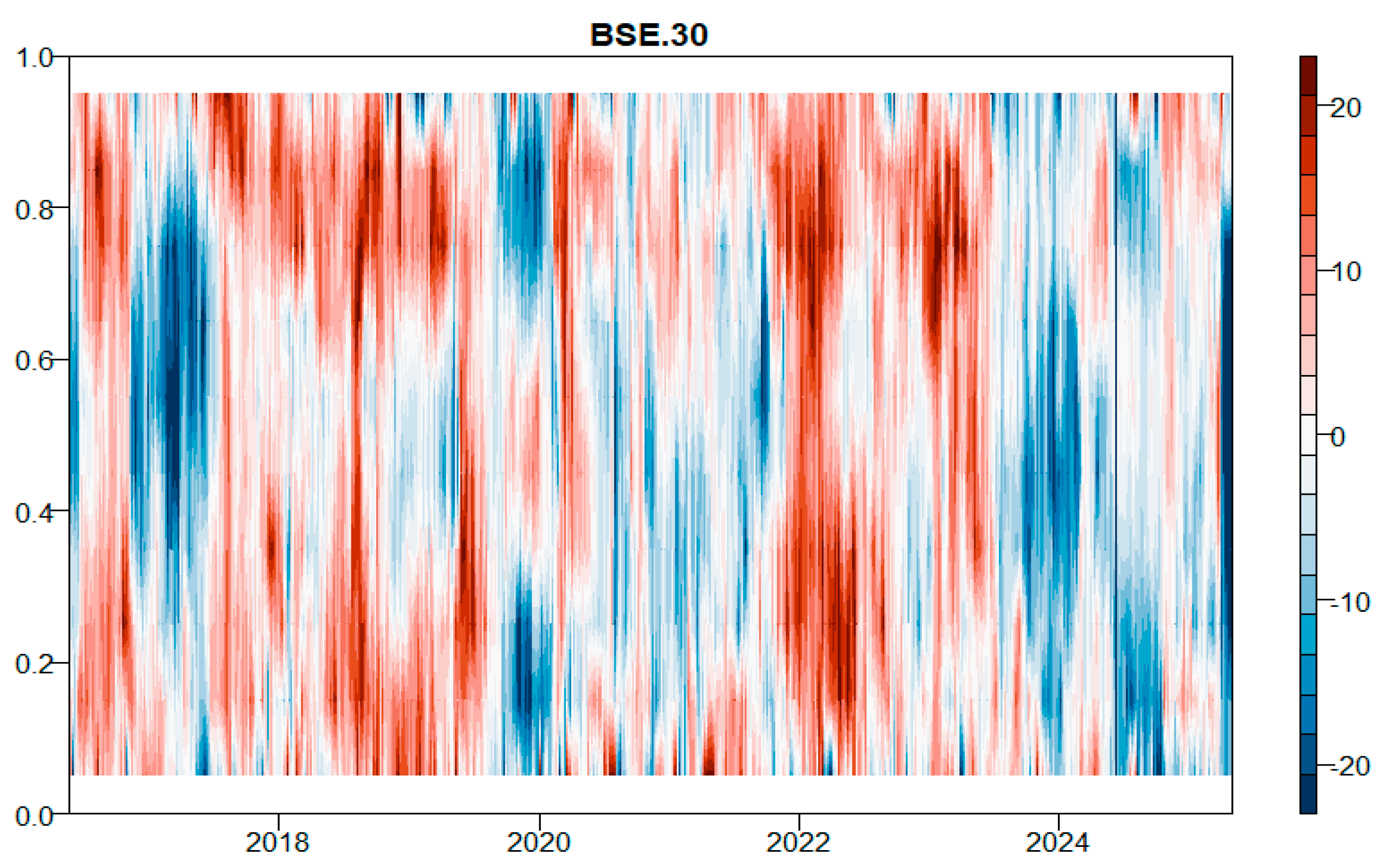

Figure 23.

Total net directional connectedness for the Brazilian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 23.

Total net directional connectedness for the Brazilian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 24.

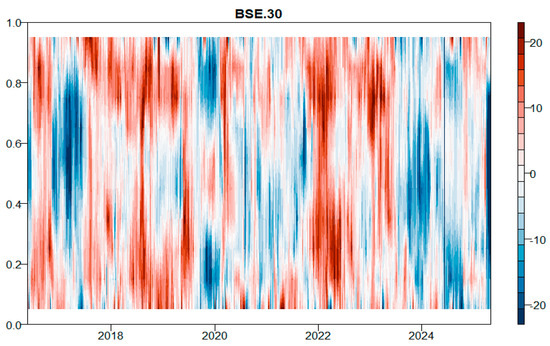

Total net directional connectedness for the Indian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 24.

Total net directional connectedness for the Indian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 25.

Total net directional connectedness for the Russian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 25.

Total net directional connectedness for the Russian stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 26.

Total net directional connectedness for the Chinese stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

Figure 26.

Total net directional connectedness for the Chinese stock index and GPRD across different quantiles.

4.3. Time Frequency Connectedness

4.3.1. Time-Frequency Connectedness Between BRICS Plus and VIX

The growing global integration of financial markets has highlighted the significance of understanding cross-market connections and shock transmission mechanisms. While there is significant research on market interdependence, traditional techniques sometimes ignore the multi-frequency character of these linkages. Financial market association occurs throughout a range of time periods, from instantaneous short-term reactions to long-term adjustments, with potentially differing consequences for portfolio diversification and systemic risk evaluations.

We address this gap by employing a spectral decomposition of the GFEVD within the framework of Diebold and Yilmaz (2012), extended to the frequency domain as proposed by Baruník and Křehlík (2018). This technique gives us the opportunity to disentangle market-connectedness patterns across different frequency bands, offering a more nuanced understanding of how financial shocks spread across markets and time horizons.

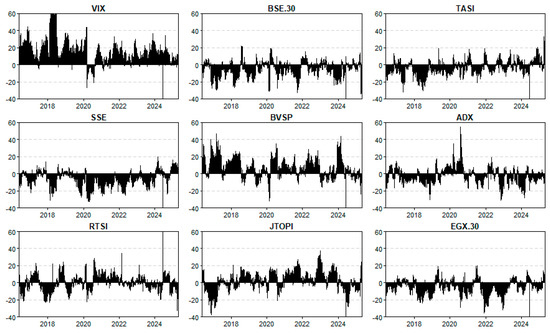

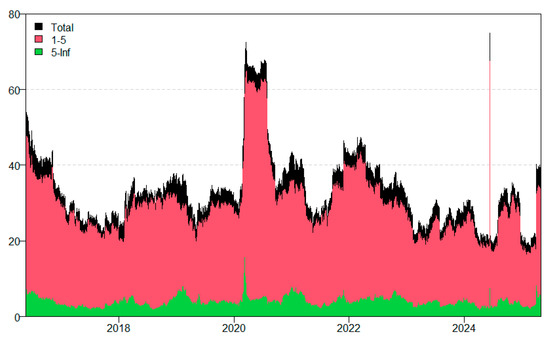

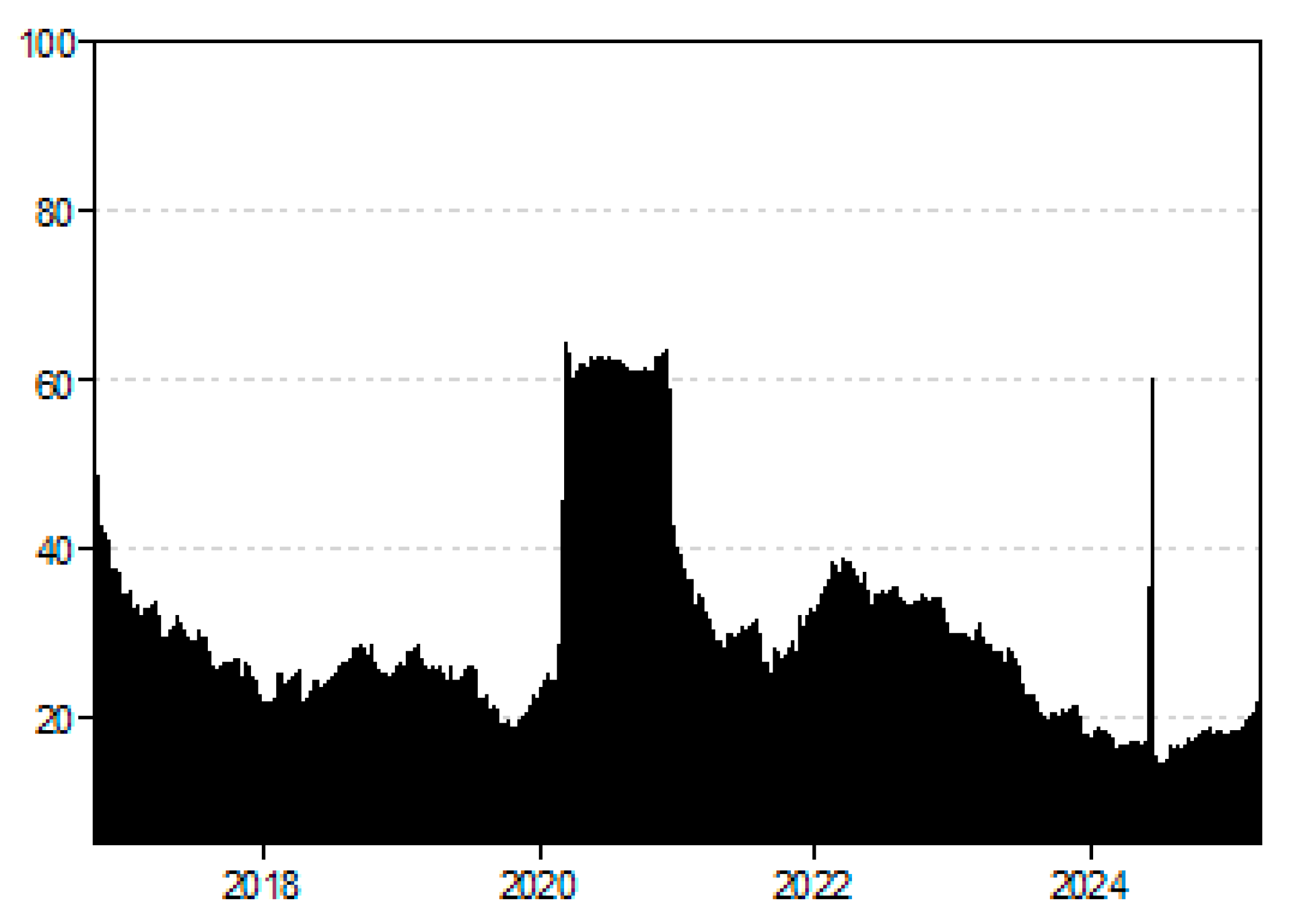

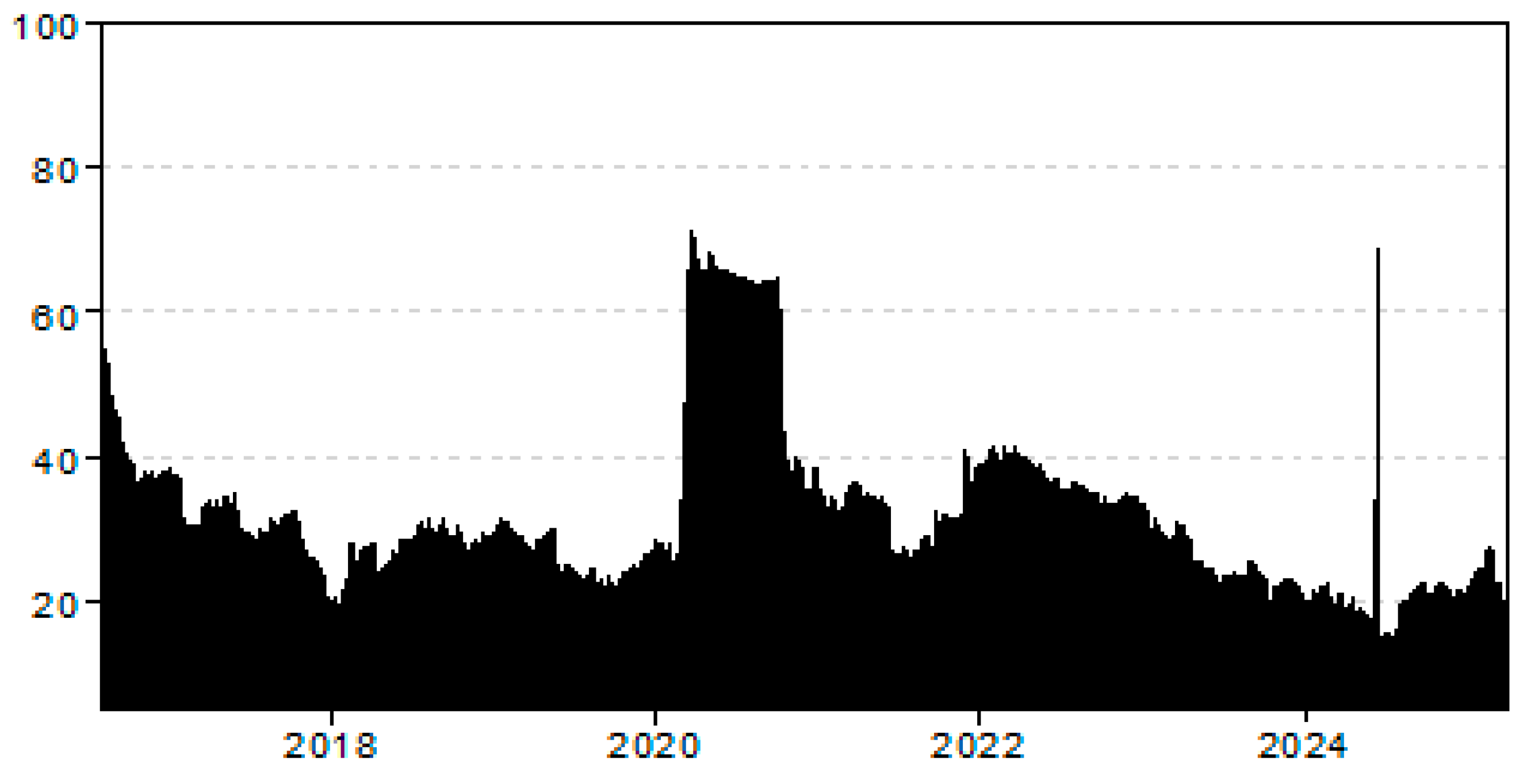

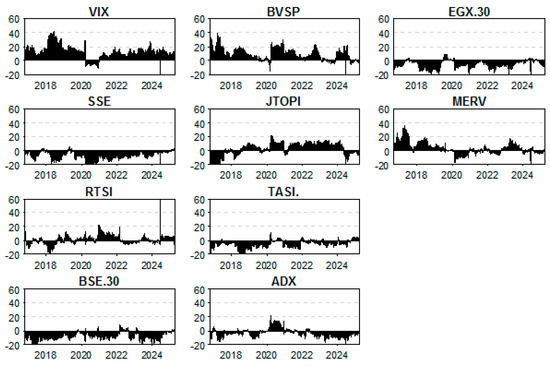

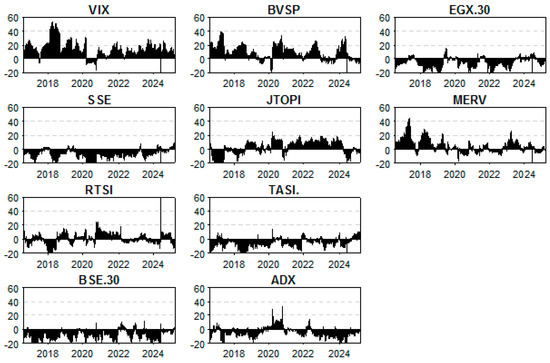

Figure 27 depicts time-frequency total connectivity, which provides important insights into market interactions over multiple periods. The black line displays the total connectedness, which fluctuates significantly across the sample period from about 20% to 70%, while the colorful sections break it down into frequency components. Short-term connectedness, illustrated by the red area (1–5 frequency band), clearly dominates the total market connections, constituting the majority of spillover effects between markets. This highlights that most financial contagion spreads via shorter-term transmission paths. In contrast, long-term connectedness, provided in green (5-inf frequency band), represents a smaller portion of the total connectedness. It does, however, exhibit occasional surges that are most likely caused by fundamental or structural issues that resulted in stronger lasting linkages between markets.

Figure 27.

Time frequency total connectedness.

Figure 27.

Time frequency total connectedness.

The most significant increase in total connectedness emerged during the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020, when the index peaked at around 70%. During this crisis period, both short-term and long-term connectedness rose, with the short-term component expanding more dramatically, illustrating the in-time panic reactions and volatility transmission across global markets. After this peak, the total connectedness progressively reduced but remained higher than pre-pandemic levels through 2022, suggesting that the pandemic’s impacts on market integration were long-lasting. Throughout the entire time series, short-term connectedness shows more pronounced volatility and responsiveness to market occurrences, while long-term connectedness maintains relative stability, capturing the enduring structural relationships between financial markets. This situation effectively demonstrates how markets are connected across different time horizons, with short-term mechanisms playing the most important role in propagating shocks across the global financial system.

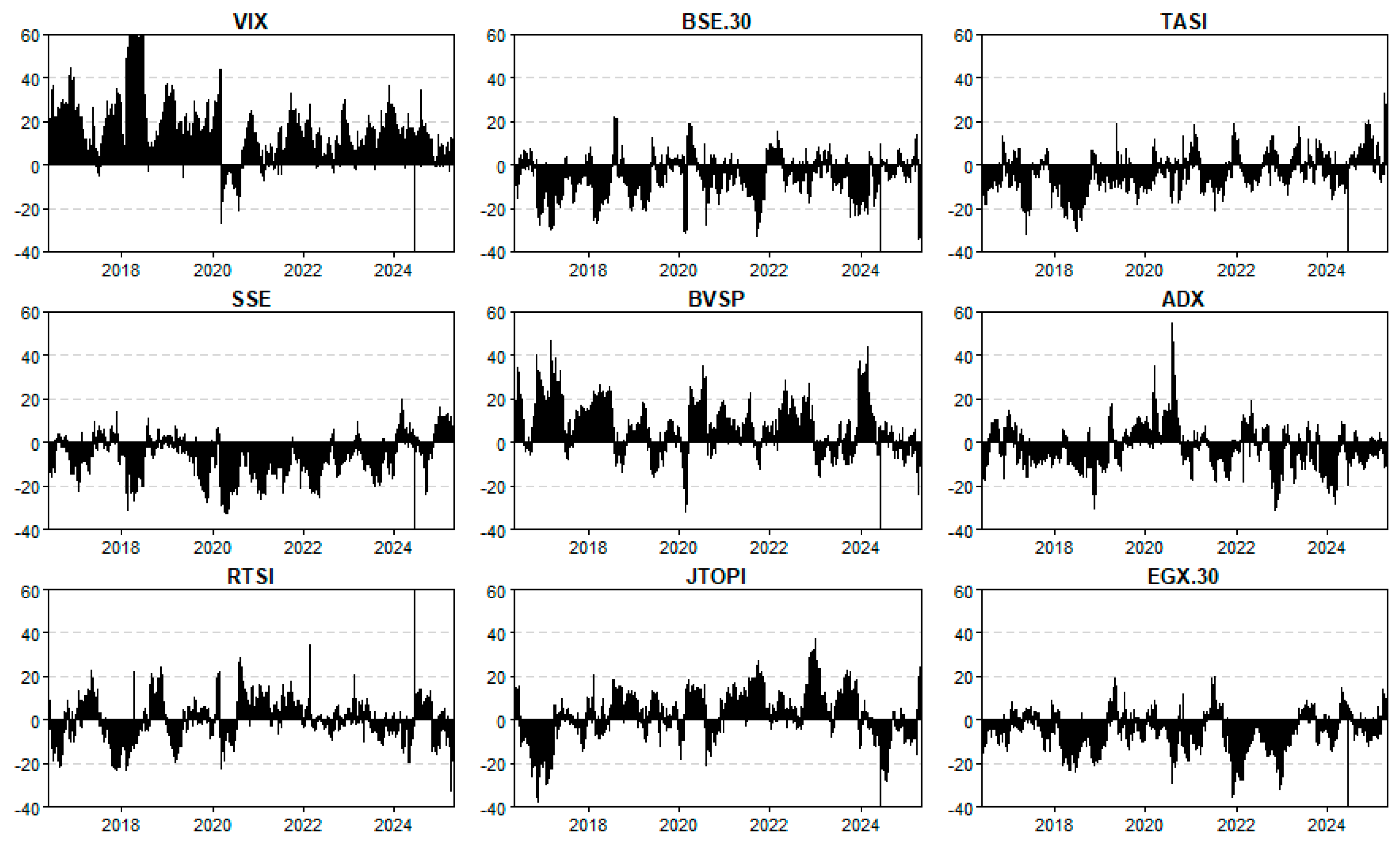

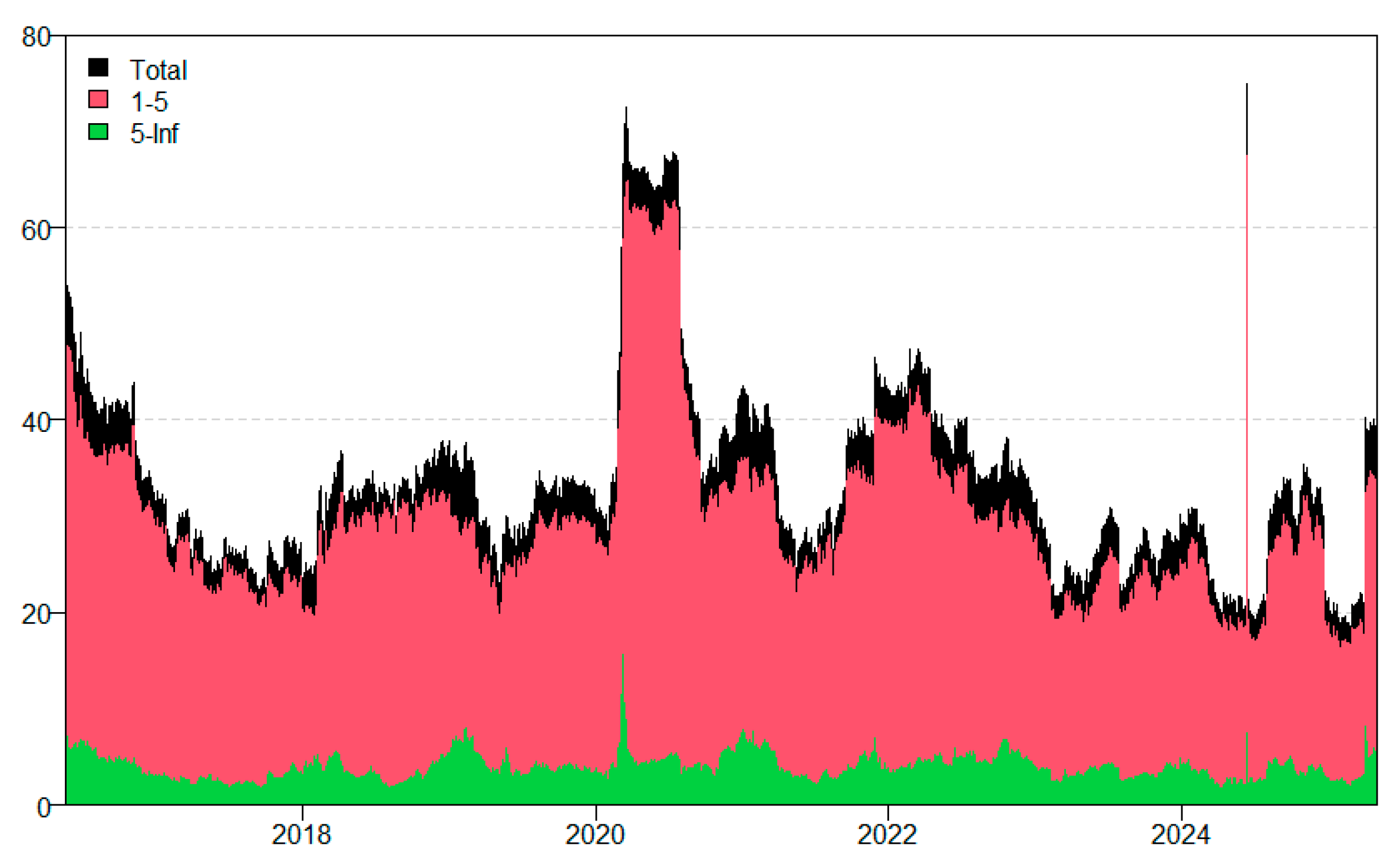

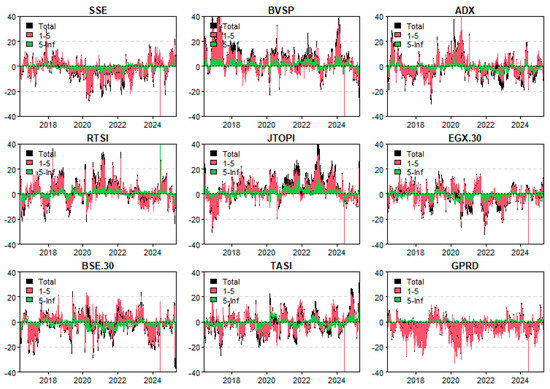

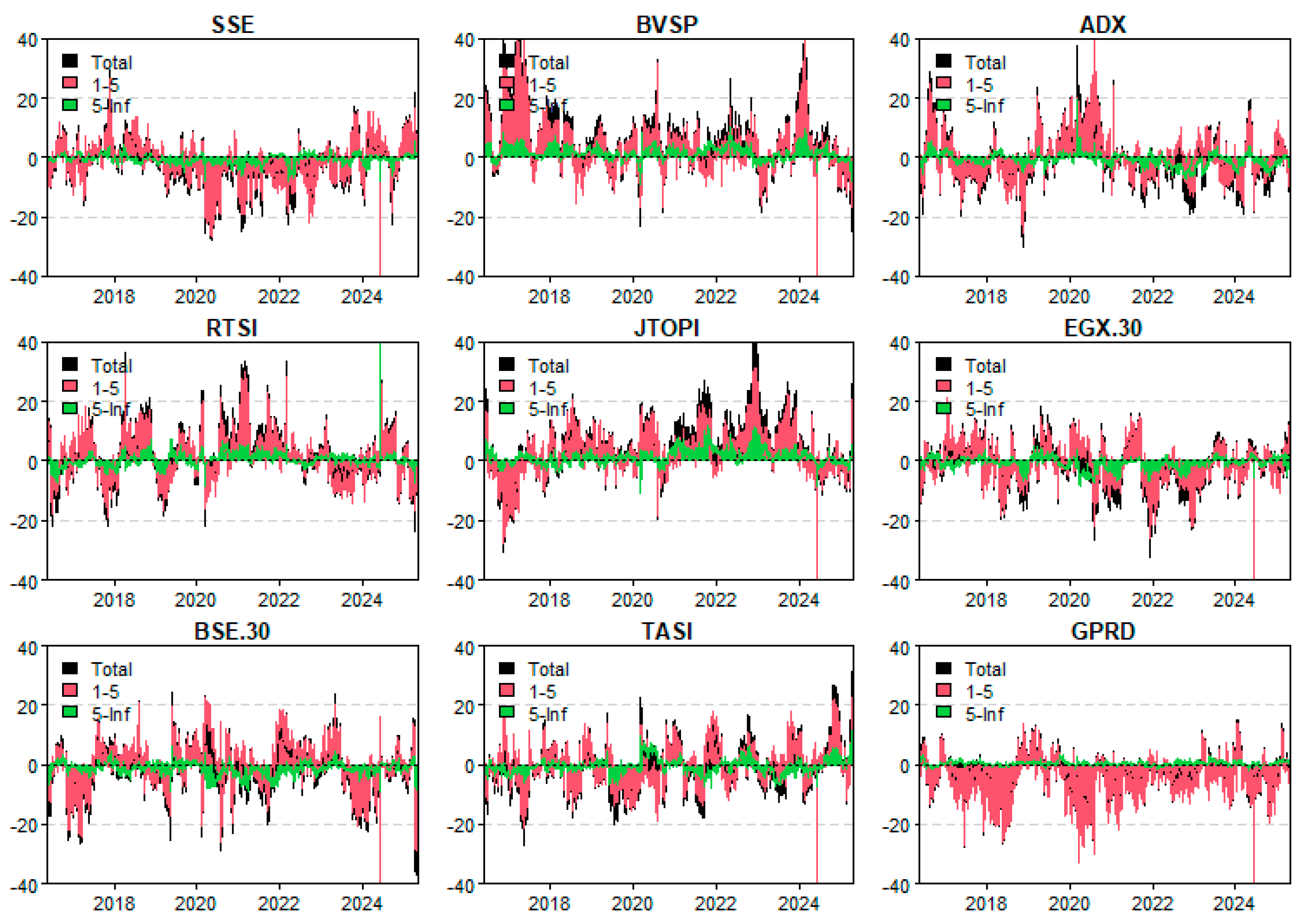

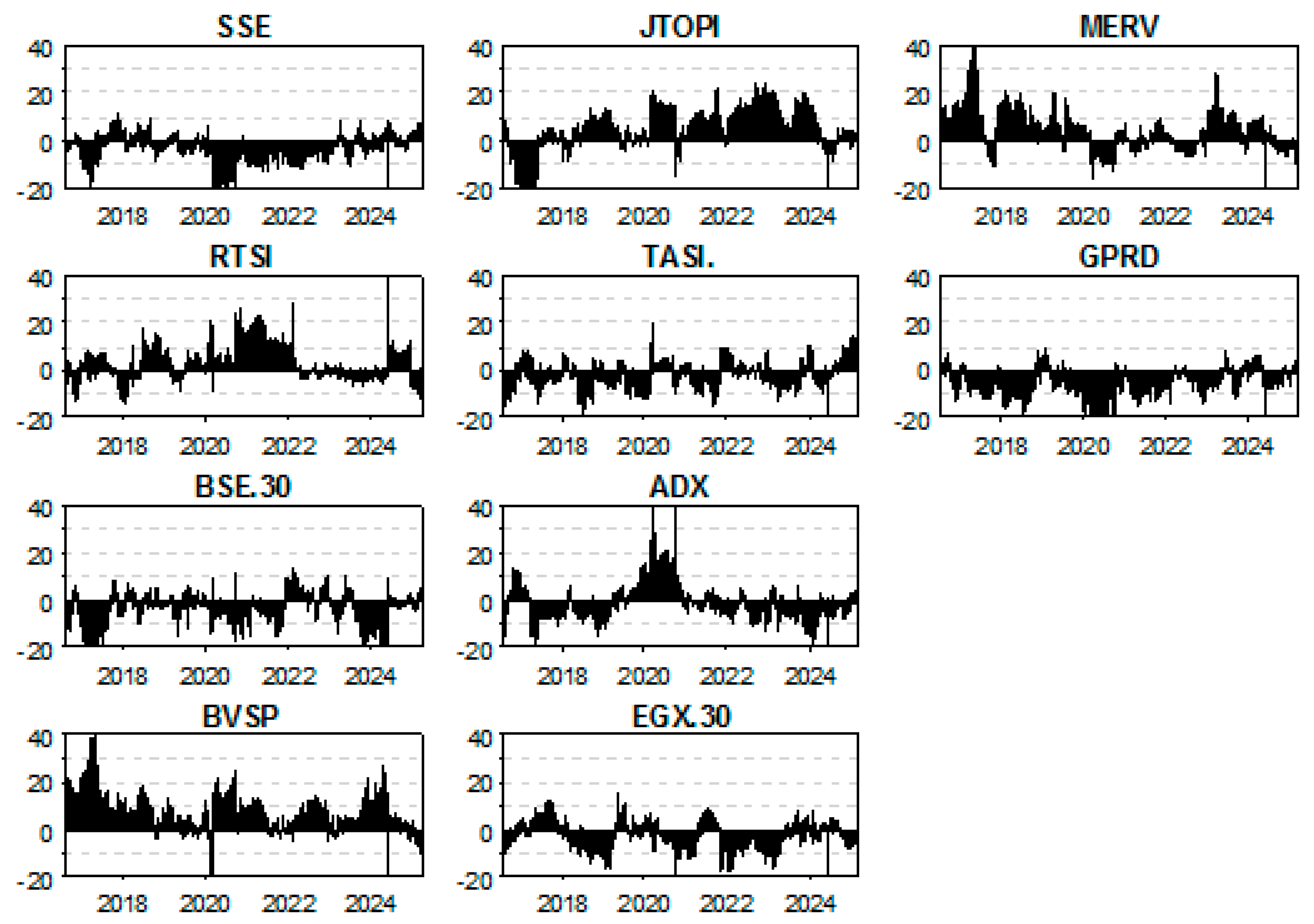

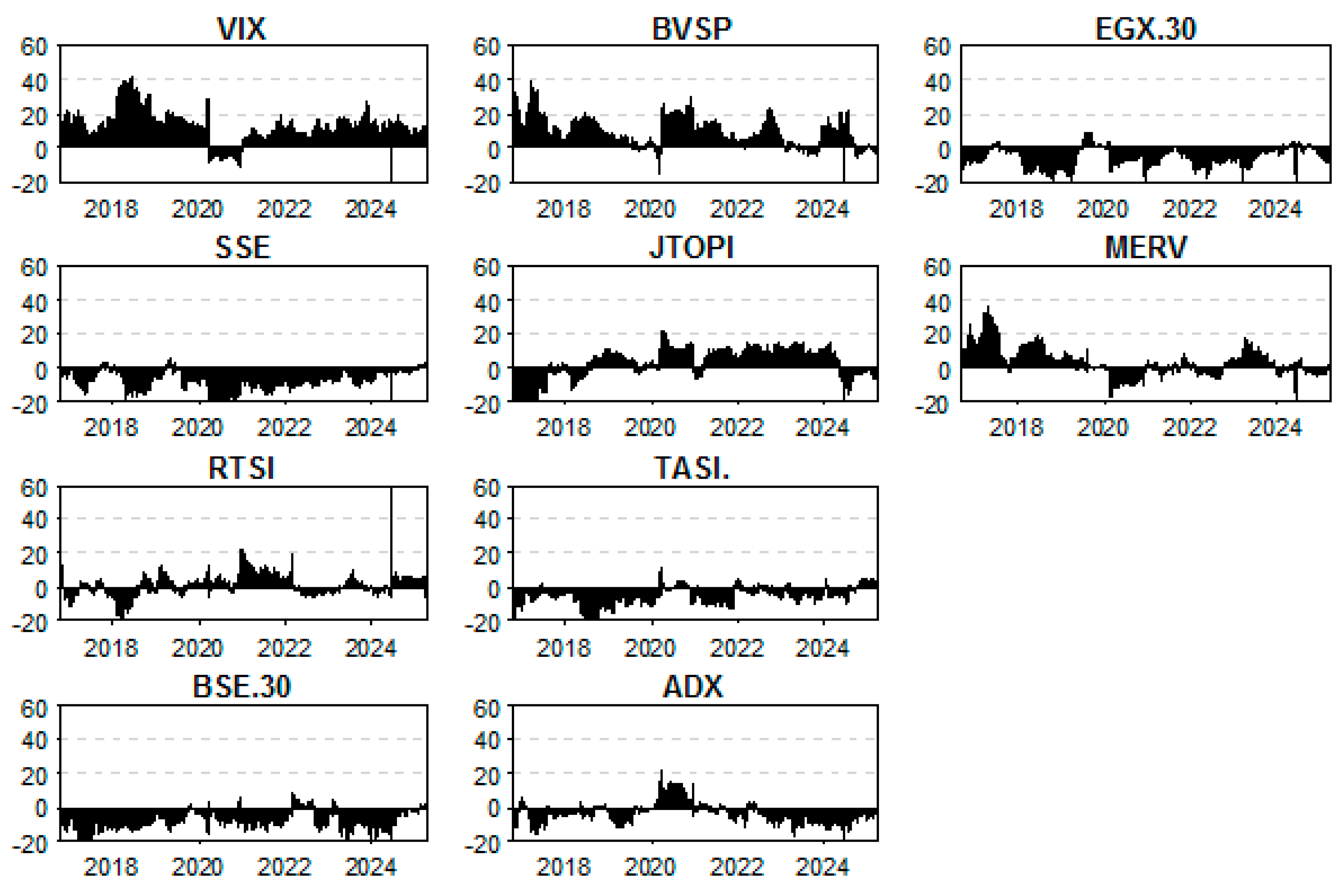

Figure 28 provides a comprehensive view of the total time frequency net connectedness regarding the different stock indices, revealing distinct patterns in how financial shocks propagate through the international financial system. Each section illustrates the net connectedness for a specific market index, decomposed into short-term (red) and long-term (green) frequency components, with the black line representing total net connectedness. The VIX stands out as the most prominent net transmitter of shocks during periods of market stress, particularly during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, confirming its role as a global “fear gauge” that influences other markets during uncertainty. This is illustrated by the pronounced positive values in its net connectedness, especially in the short-term frequency band, indicating that shocks originating from the VIX quickly spread to other markets. These findings corroborate the above-observed ones, detected in Figure 8, regarding the net transmission of shocks behavior of the VIX. Emerging stock markets such as BSE-30 (India) and BVSP (Brazil) exhibit a fluctuating shock transmission and reception behavior. The BSE-30 fluctuates between being a net receiver and transmitter over different periods, while BVSP shows stronger transmission abilities during certain market phases. Moreover, Commodity-sensitive markets such as RTSI (Russia) display pronounced volatility in their net connectedness, reflecting their sensitivity to commodity price fluctuations, particularly oil prices. Meanwhile, SSE (China), JTOPI (South Africa), ADX (UAE), TASI (Saudi Arabia), and EGX-30 (Egypt) predominantly function as net receivers of shocks, as indicated by their negative net connectedness values, revealing their relative vulnerability to external financial situations. Across all markets, short-term connectedness (red) typically shows greater volatility and more extreme values than long-term connectedness (green), suggesting that immediate market reactions are more powerful in transmitting shocks than persistent structural relationships. In addition, the importance of short-term in comparison to long-term connectedness also varies across different market occurrences, with short-term spillovers becoming particularly dominant during times of turmoil4.

Figure 28.

Time frequency total net connectedness.

Figure 28.

Time frequency total net connectedness.

The results in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 demonstrate that, on average, total connectedness among the VIX and BRICS Plus stock indices is moderate (TCI ≈ 33–37%), with the VIX consistently acting as the most prominent net transmitter of shocks (high TO, low FROM, positive Net Spillover). Short-run connectedness (1–5 days) dominates, accounting for most spillovers (TCI ≈ 29–32%), while long-run spillovers (beyond 5 days) are minimal (TCI ≈ 3–4%), indicating that market interactions are primarily short-lived and driven by immediate reactions rather than persistent long-term impacts. Particularly, the VIX has the greatest effect over all horizons, whereas indexes such as ADX, EGX 30, and TASI are better insulated, absorbing rather than transmitting shocks. These patterns demonstrate the importance of short-term dynamics in understanding return connectivity, as well as the significance of shocks in altering the spillover landscape across markets.

Table 4.

Total average connectedness.

Table 5.

Averaged return connectedness in the short run (1–5 traded days).

Table 6.

Averaged return connectedness in the long run (5-infinite traded days).

4.3.2. Time-Frequency Connectedness Between BRICS Plus and GPRD

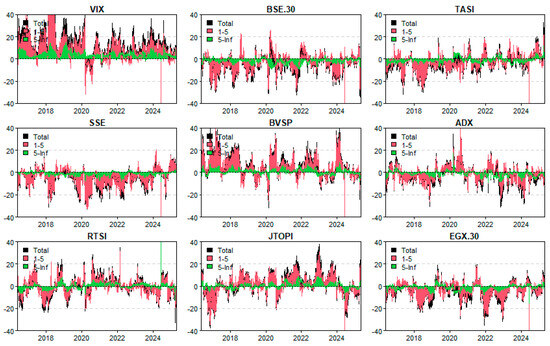

Figure 29 illustrates the time-frequency total connectedness between the BRICS Plus stock market indices and the GPRD. The graphical outcome demonstrates that market connectedness fluctuates widely, with total connectedness ranging from 20% to 70% over time. Short-term connectedness (1–5 days) is predominant, causing most spillover effects and contagion across markets. Long-term connectedness (5+ days) plays a smaller but occasionally important role, especially during periods of turmoil. In the same manner, the sharpest spike occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, when total connectedness surged to about 70%, mainly due to short-term panic-driven transmission.

Figure 29.

Time frequency total connectedness.

Figure 29.

Time frequency total connectedness.

Following that, connectedness was reduced but stayed higher than pre-pandemic levels, showing lasting effects on global market integration. Overall, the results show that short-term connectedness between the BRICS Plus stock market indices and the GPR index is the primary driver of shock transmission, while long-term connectedness reflects a more stable relationship.

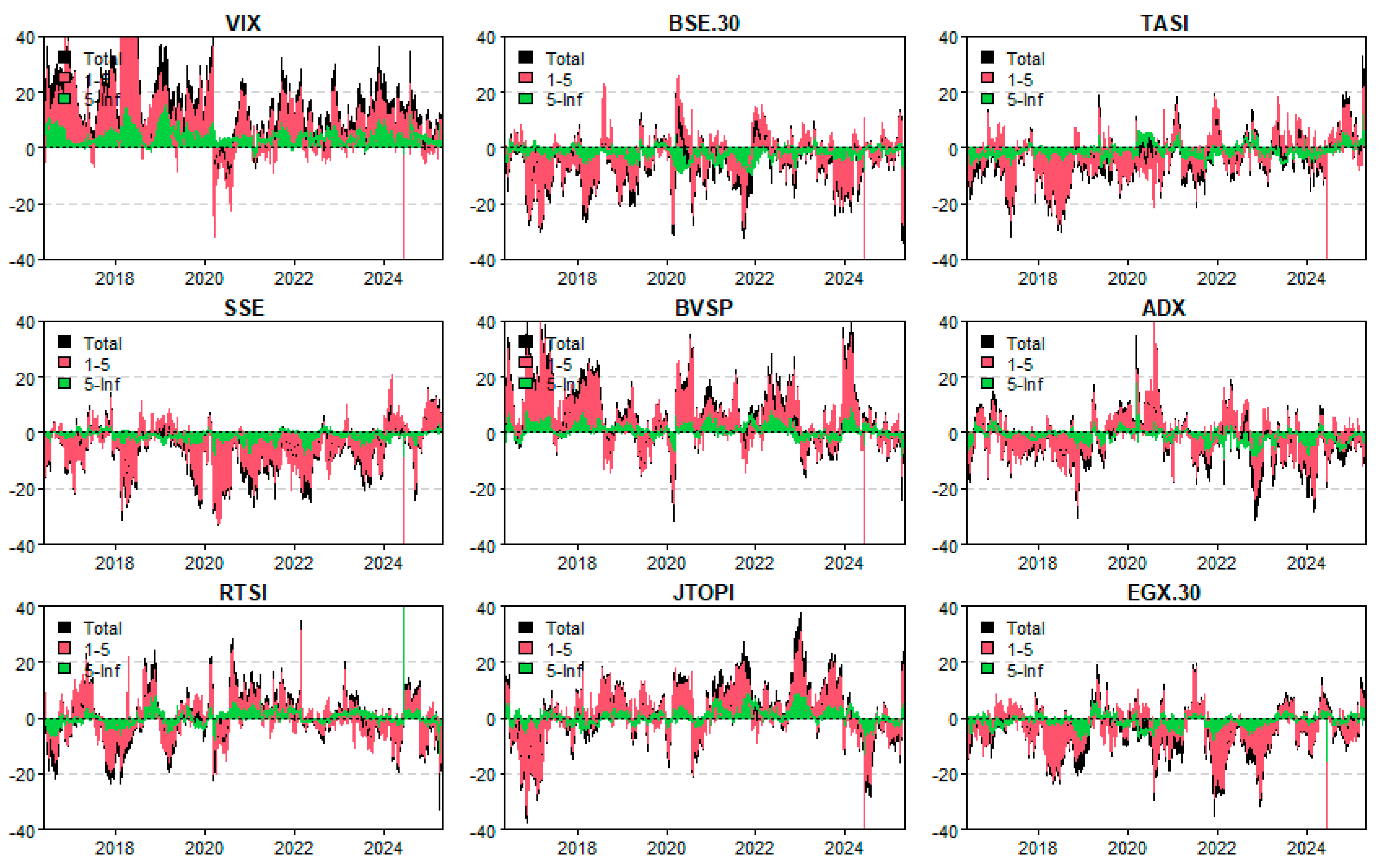

The time-frequency total net connectedness analysis results in Figure 30 reveals important patterns regarding the dynamics of shock transmission between the different assets. The total net connectedness, represented by the black line, illustrates the overall role of each market as a net transmitter or receiver over time. Short-term connectedness, shown in red (1–5 days), dominates across most indices, indicating that the majority of spillovers occur through rapid, short-term channels. In contrast, the long-term component, depicted in green (5+ days), stays relatively small and stable, capturing the slower structural spillover effects between markets over the long run.

Figure 30.

Time frequency total net connectedness.

Figure 30.

Time frequency total net connectedness.

A notable aspect is that several indices show increases in both total and short-term net connection during substantial crises, indicating intensive global shock transmission. This surge is particularly evident in markets that display larger fluctuations and stronger net transmitter roles during periods of crises. Meanwhile, some indices, especially the GPRD, stand out for their consistently negative net connectedness, suggesting a persistent role as a net receiver of shocks. Other markets, including ADX, TASI, and EGX.30, show more moderate and balanced behavior, shifting between transmitter and receiver roles depending on market conditions.

Overall, this decomposition indicates that short-term dynamics are the primary drivers of net spillovers across these markets, while long-term connectedness plays a smaller and steadier role. The outcomes also underscore how major global events amplify connectedness, with short-term reactions remaining the most dominant force over the sample period.

The total average connectedness (Table 7) reveals that JTOPI, BSE 30, and RTSI are the most exposed, showing the highest “FROM” spillovers (38.7%, 35.6%, and 32.7%, respectively), suggesting that they are more influenced by shocks from others while the GPRD is the most independent and the lowest is FROM (18.7%). In the short run (Table 8), connectedness is generally higher across markets, with JTOPI and BSE 30 again standing out as major shock receivers, whereas in the long run (Table 9), the connectedness sharply drops, indicating that most return spillovers are short-lived. Overall, the TCI is much stronger in the short run (25.7%) compared to the long run (3.2%), emphasizing that these markets react quickly but decouple over time.

Table 7.

Total average connectedness.

Table 8.

Averaged return connectedness in the short run (1–5 traded days).

Table 9.

Averaged return connectedness in the long run (5-infinite traded days).

5. Conclusions

By applying a suite of advanced methodologies, including the TVP-VAR model, quantile connectedness analysis, and time-frequency connectedness techniques, our study investigated the dynamic connectedness between BRICS Plus stock markets and global risk indicators, namely, the VIX and the GPRD. Our results offer valuable insights into how volatility and geopolitical risks propagate through emerging financial markets, particularly during times of turmoil.

The findings demonstrate that market connectedness among BRICS Plus stock indices and global risk proxies are highly dynamic, asymmetric, and quantile- and frequency-dependent. The VIX consistently emerges as the most dominant net transmitter of shocks, especially during periods of financial turmoil such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian-Ukraine conflict, and the U.S.-China trade tensions under the Trump administration. This reinforces its role as a global “fear gauge” and underscores the vulnerability of BRICS Plus markets to shocks originating from this index. In contrast, the GPRD functions mostly as a net receiver of shocks, particularly in lower and median quantiles and during times of crisis. This suggests that GPR may act as a potential hedge against emerging market volatility under certain conditions.

In terms of geographical heterogeneity, our results indicate that Brazil (BVSP), South Africa (JTOPI), and Russia (RTSI) often operate as shock transmitters, while China (SSE), India (BSE 30), the UAE (ADX), Saudi Arabia (TASI), and Egypt (EGX 30) frequently serve as shock receivers, particularly in median and lower quantiles. This divergence reveals an asymmetric spillover structure, shaped by structural, economic, and geopolitical differences across the BRICS Plus economies.

The quantile-based connectedness framework further reveals that extreme market conditions, both bullish and bearish, intensify shock transmission, revealing nonlinear and state-dependent interdependencies. Notably, the VIX and several BRICS Plus indices change their roles across quantiles, with most spillovers occurring during the tails of the distribution. This implies that during episodes of financial panic, market co-movements and systemic risks rise considerably.

Our time-frequency analysis adds another layer of nuance by showing that the short-term connectedness (1–5 days) overwhelmingly dominates the transmission process. This suggests that financial contagion primarily unfolds over short time horizons, consistent with panic-driven behavior and immediate reactions to global events. Long-term connectedness is comparatively subdued but still significant during certain periods, such as during the peak of the COVID-19 crisis, indicating persistent structural linkages.

Together, these findings underscore the systemic vulnerability of emerging markets to global financial and geopolitical disturbances and highlight the importance of the short-term dynamics in driving spillovers. Furthermore, the policy relevance of our findings has been clarified. The consistent role of the VIX as a transmitter reinforces its importance as a leading indicator of global financial stress, which policymakers and investors can monitor to anticipate potential contagion episodes. In contrast, the GPRD’s receiver role suggests that it can function as an early-warning tool for geopolitical uncertainty, reflecting the way markets internalize rather than propagate geopolitical risk. These insights have meaningful implications for investors, portfolio managers, and policymakers, particularly in terms of risk management, asset allocation, and macroprudential oversight. Investors should monitor high-frequency linkages and consider short-term hedging instruments while policymakers need to strengthen regulatory resilience to buffer against externally driven shocks.

Despite the robustness of the adopted methodologies, this study has several limitations. It focuses solely on BRICS Plus stock indices, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other markets. The analysis also considers only two risk indicators (VIX and GPRD), omitting other potential sources of uncertainty. Furthermore, the models used are data-driven and do not account for underlying macroeconomic structures or policy responses, nor do they capture sectoral or firm-level heterogeneity. Potential extensions of this research could include expanding the scope to benchmark emerging and developed markets for comparative analysis, as well as incorporating additional macroeconomic indicators. Future studies might also consider robustness checks by integrating other risk factors, such as crude oil prices, the VIX, and global geopolitical risk indices, into the connectedness framework. These directions hold promise for enriching the understanding of systemic risk transmission while addressing concerns related to confounding effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K. and A.J.; methodology, S.F.; software, A.J.; validation, C.K., N.A. and S.F.; formal analysis, N.A.; investigation, C.K.; resources, A.J.; data curation, A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F.; writing—review and editing, N.A.; visualization, S.F.; supervision, S.F.; project administration, N.A.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support received for this research. This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2504).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BRICS | Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa |

| GFEVD | Generalized Forecast Error Variance Decomposition |

| GPR | Geopolitical Risk |

| GPRD | Geopolitical Risk Index |

| H | Covariance matrix of residuals |

| NET | Total Net Directional Connectedness |

| NPDC | Net Pairwise Directional Connectedness |

| NPT | Normalized Pairwise Net spillover |

| TCI | Total Connectedness Index |

| TVP-VAR | Time-Varying Parameter Vector Autoregression |

| VIX | Volatility Index |

| Φt | Time-varying coefficient matrix in TVP-VAR model |

| Τ | Quantile level in Quantile Connectedness (e.g., 0.05, 0.50, 0.95) |

Appendix A. Robustness Tests Using Different Rolling Windows (200 and 150 Days)

Appendix A.1. Results for the BRICS Plus Countries and the GPRD

Appendix A.1.1. Results Using Rolling Windows = 200 Days

Figure A1.

Dynamic total connectedness.

Figure A1.

Dynamic total connectedness.

Figure A2.

Dynamic total net connectedness.

Figure A2.

Dynamic total net connectedness.

Table A1.

Connectedness measures.

Table A1.

Connectedness measures.

| SSE | RTSI | BSE.30 | BVSP | JTOPI | TASI. | ADX | EGX.30 | MERV | GPRD | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSE | 79.45 | 2.29 | 3.19 | 2.42 | 6.06 | 1.54 | 1.07 | 1.49 | 1.53 | 0.95 | 20.55 |

| RTSI | 1.55 | 69.39 | 3.99 | 6.01 | 7.29 | 2.82 | 2.24 | 1.71 | 4.39 | 0.60 | 30.61 |

| BSE.30 | 2.55 | 4.72 | 65.39 | 5.39 | 8.41 | 4.09 | 2.82 | 2.20 | 3.40 | 1.02 | 34.61 |

| BVSP | 1.55 | 5.34 | 3.35 | 67.14 | 5.98 | 2.22 | 1.93 | 1.54 | 10.44 | 0.51 | 32.86 |

| JTOPI | 4.41 | 6.98 | 7.28 | 6.76 | 61.63 | 3.38 | 2.35 | 2.37 | 4.12 | 0.73 | 38.37 |

| TASI. | 1.70 | 3.92 | 4.15 | 3.14 | 4.48 | 72.34 | 5.06 | 2.56 | 2.10 | 0.55 | 27.66 |

| ADX | 0.98 | 2.63 | 2.85 | 2.94 | 3.06 | 5.91 | 77.26 | 2.11 | 1.53 | 0.74 | 22.74 |

| EGX.30 | 1.38 | 2.28 | 2.79 | 2.04 | 3.32 | 2.82 | 2.52 | 80.24 | 1.81 | 0.80 | 19.76 |

| MERV | 0.92 | 4.55 | 1.86 | 11.06 | 3.60 | 1.75 | 1.27 | 1.75 | 72.67 | 0.58 | 27.33 |

| GPRD | 1.31 | 1.20 | 1.17 | 0.89 | 1.22 | 0.93 | 2.09 | 1.10 | 1.44 | 88.64 | 11.36 |

| TO | 16.35 | 33.91 | 30.62 | 40.65 | 43.45 | 25.46 | 21.35 | 16.83 | 30.76 | 6.48 | 265.85 |

| Inc.Own | 95.80 | 103.31 | 96.01 | 107.79 | 105.07 | 97.80 | 98.61 | 97.07 | 103.43 | 95.12 | cTCI/TCI |

| NET | −4.20 | 3.31 | −3.99 | 7.79 | 5.07 | −2.20 | −1.39 | −2.93 | 3.43 | −4.88 | 29.54/26.59 |

| NPT | 2.00 | 7.00 | 5.00 | 9.00 | 7.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 7.00 | 0.00 |

Appendix A.1.2. Results Using Rolling Windows = 150 Days

Table A2.

Connectedness measures.

Table A2.

Connectedness measures.

| SSE | RTSI | BSE.30 | BVSP | JTOPI | TASI. | ADX | EGX.30 | MERV | GPRD | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSE | 78.42 | 2.38 | 3.16 | 2.50 | 5.94 | 1.63 | 1.20 | 1.71 | 1.74 | 1.32 | 21.58 |

| RTSI | 1.72 | 67.89 | 3.96 | 5.92 | 7.45 | 3.03 | 2.49 | 1.87 | 4.74 | 0.95 | 32.11 |

| BSE.30 | 2.58 | 4.75 | 64.13 | 5.41 | 8.16 | 4.31 | 2.95 | 2.61 | 3.69 | 1.40 | 35.87 |

| BVSP | 1.65 | 5.50 | 3.36 | 66.07 | 5.92 | 2.31 | 2.05 | 1.75 | 10.56 | 0.82 | 33.93 |

| JTOPI | 4.33 | 7.17 | 7.17 | 6.74 | 60.98 | 3.48 | 2.39 | 2.49 | 4.27 | 0.97 | 39.02 |

| TASI. | 1.91 | 4.09 | 4.24 | 3.15 | 4.51 | 70.85 | 4.99 | 2.94 | 2.51 | 0.81 | 29.15 |

| ADX | 1.19 | 2.83 | 2.88 | 3.03 | 3.10 | 5.83 | 75.93 | 2.33 | 1.79 | 1.08 | 24.07 |

| EGX.30 | 1.70 | 2.40 | 3.17 | 2.28 | 3.31 | 3.04 | 2.74 | 78.14 | 2.15 | 1.08 | 21.86 |

| MERV | 1.12 | 4.68 | 2.11 | 11.02 | 3.76 | 2.01 | 1.48 | 2.19 | 70.88 | 0.75 | 29.12 |

| GPRD | 1.67 | 1.64 | 1.53 | 1.36 | 1.52 | 1.40 | 2.41 | 1.43 | 1.78 | 85.26 | 14.74 |

| TO | 17.88 | 35.44 | 31.57 | 41.41 | 43.68 | 27.03 | 22.69 | 19.33 | 33.23 | 9.18 | 281.45 |

| Inc.Own | 96.29 | 103.33 | 95.71 | 107.48 | 104.66 | 97.88 | 98.62 | 97.47 | 104.11 | 94.44 | cTCI/TCI |

| NET | −3.71 | 3.33 | −4.29 | 7.48 | 4.66 | −2.12 | −1.38 | −2.53 | 4.11 | −5.56 | 31.27/28.15 |

| NPT | 2.00 | 6.00 | 3.00 | 9.00 | 7.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 7.00 | 0.00 |

Figure A3.

Dynamic total connectedness.

Figure A3.

Dynamic total connectedness.

Figure A4.

Dynamic total net connectedness.

Figure A4.

Dynamic total net connectedness.

Appendix A.2. Results for the BRICS Plus Countries and the VIX

Appendix A.2.1. Results Using Rolling Windows = 200 Days

Figure A5.

Dynamic total connectedness.

Figure A5.

Dynamic total connectedness.

Figure A6.

Dynamic total net conenctedenss.

Figure A6.

Dynamic total net conenctedenss.

Table A3.

Total connectedness measures.

Table A3.

Total connectedness measures.

| VIX | SSE | RTSI | BSE.30 | BVSP | JTOPI | TASI. | ADX | EGX.30 | MERV | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIX | 61.93 | 1.03 | 4.48 | 3.43 | 9.53 | 6.52 | 2.10 | 2.68 | 1.62 | 6.69 | 38.07 |

| SSE | 2.92 | 77.39 | 2.27 | 2.90 | 2.71 | 5.54 | 1.49 | 1.25 | 1.62 | 1.91 | 22.61 |

| RTSI | 5.27 | 1.49 | 65.84 | 3.55 | 5.61 | 6.76 | 2.81 | 2.41 | 1.67 | 4.57 | 34.16 |

| BSE.30 | 7.26 | 2.22 | 4.15 | 61.21 | 5.26 | 7.14 | 4.06 | 2.83 | 2.33 | 3.55 | 38.79 |

| BVSP | 9.48 | 1.52 | 4.85 | 3.16 | 60.24 | 5.43 | 2.16 | 1.84 | 1.57 | 9.75 | 39.76 |

| JTOPI | 8.40 | 3.73 | 6.34 | 6.17 | 6.56 | 56.59 | 3.11 | 2.34 | 2.26 | 4.49 | 43.41 |

| TASI. | 3.52 | 1.59 | 3.84 | 3.97 | 3.41 | 4.24 | 69.38 | 4.65 | 2.72 | 2.67 | 30.62 |

| ADX | 3.57 | 1.14 | 2.73 | 2.71 | 2.92 | 2.95 | 5.57 | 74.34 | 2.29 | 1.77 | 25.66 |