Abstract

Preventable medication harm in oncology is often driven by drug-related adverse events (AEs) that trigger order changes such as holds, dose reductions, delays, rechallenges, and enhanced monitoring. Much of the evidence needed to make these decisions lives in unstructured clinical texts, where large language models (LLMs), a type of artificial intelligence (AI), now offer extraction and reasoning capabilities. In this narrative review, we synthesize empirical studies evaluating LLMs and related NLP systems applied to clinical text for oncology AEs, focusing on three decision-linked tasks: (i) AE detection from clinical documentation, (ii) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) grade assignment, and (iii) grade-aligned actions. We also consider how these findings can inform pharmacist-facing recommendations for order-level safety. We conducted a narrative review of English-language studies indexed in PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, and Embase. Eligible studies used LLMs on clinical narratives and/or authoritative guidance as model inputs or reference standards; non-text modalities and non-empirical articles were excluded. Nineteen studies met inclusion criteria. LLMs showed the potential to detect oncology AEs from routine notes and often outperformed diagnosis codes for surveillance and cohort construction. CTCAE grading was feasible but less stable than detection; performance improved when outputs were constrained to CTCAE terms/grades, temporally anchored, and aggregated at the patient level. Direct evaluation of grade-aligned actions was uncommon; most studies reported proxies (e.g., steroid initiation or drug discontinuation) rather than formal grade-to-action correctness. While prospective, real-world impact reporting remained sparse, several studies quantified scale advantages and time savings, supporting an initial role as high-recall triage with pharmacist adjudication. Overall, the evidence supports near-term, pharmacist-in-the-loop use of AI for AE surveillance and review, with CTCAE-structured, citation-backed outputs delivered into the pharmacist’s electronic health record order-verification workspace as reviewable artifacts. Future work must standardize reporting and CTCAE/version usage, and measure grade-to-action correctness prospectively, to advance toward order-level decision support.

1. Introduction

Preventable medication harm remains a central safety challenge in oncology, where polypharmacy, narrow therapeutic indices, organ dysfunction, and evolving protocols increase the risk of error [1,2,3]. Oncology pharmacists are expected to function as medication-safety leaders and the safeguard before order execution, with explicit responsibilities for independent verification of doses, routes, schedules, and system-level error prevention [1,4].

Within this landscape, drug-related adverse events (AEs) drive a large share of clinically important order changes (hold, dose reduction, delay, rechallenge, enhanced monitoring). AEs are common in cancer populations. Systematic reviews and cohort studies report high rates of treatment-related toxicities, particularly with oral oncolytics and supportive therapies, underscoring the need for proactive pharmacist triage [2]. On the toxicity side, oncology standardizes severity using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), which maps signs, symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities to graded levels that trigger specific clinical actions [5]. Newer modalities add domain-specific frameworks: immune effector cell therapies require consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) from the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, while immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) care relies on guideline-based management of immune-related AEs (irAEs) [6,7,8,9,10].

These safety decisions rely predominantly on text, such as clinic and infusion notes, telephone encounters, discharge summaries, and narrative reports. Manually processing these narratives at scale, however, is inherently difficult [11]. Multiple overviews estimate that a large proportion of clinically relevant EHR information is unstructured and resides in narrative text, motivating text-centric methods for surveillance and decision support [12]. In oncology specifically, investigators have shown that Artificial Intelligence (AI)-based automation, such as Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques, could identify irAEs from clinical narratives and improve mapping to structured labels, demonstrating the feasibility of AE surveillance [13,14,15].

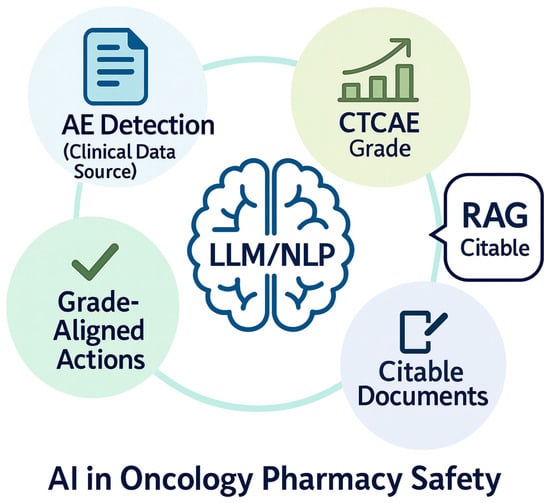

Over the last several years, more advanced AI approaches such as large language models (LLMs) have expanded what is possible for extraction and reasoning from clinical text, but they are fallible in high-stakes settings without safeguards [16,17,18,19]. LLMs can produce factually incorrect or unfaithful statements (“hallucinations”) and omissions, reinforcing the need for designs that foreground provenance and constrain outputs [20]. One consistently supported mitigation is retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), which conditions generation on retrieved, citable documents and has been shown to improve factual specificity on knowledge-intensive tasks [21]. Global public-health bodies likewise urge caution and governance when deploying LLMs in healthcare workflows [22]. Figure 1 illustrates an AI (LLM/NLP) workflow oriented to oncology pharmacy, emphasizing AE detection from clinical text, CTCAE grade assignment, and grade-aligned actions supported by retrieval and citation.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the role of large language models (LLMs) and natural language processing (NLP) in enhancing oncology pharmacy safety. The figure depicts three interrelated domains: (1) Adverse Event (AE) detection from clinical notes, enabling early identification of safety risks; (2) CTCAE grade assignment, mapping toxicity severity using standardized criteria; and (3) Grade-aligned actions such as holding, restarting, dose-adjusting, or monitoring treatment based on toxicity grading, supported by retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to surface citable evidence from trusted guidelines and references in real time.

Our narrative review focuses on oncology-pharmacy safety use cases where LLMs could support verification and propose candidate actions at medication order review: (i) AE detection from clinical documentation, (ii) CTCAE grade assignment, and (iii) grade-aligned actions (hold/reduce/delay/rechallenge/monitor). These three focal tasks in this review directly align with established oncology pharmacy responsibilities and safety checks. The American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society (ASCO–ONS) (ASCO–ONS) antineoplastic therapy administration standards require independent verification, documentation, and escalation processes that place pharmacists at the safety gate for order review and changes, across settings and routes of administration [1,23]. Professional guidance from Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Association HOPA likewise defines pharmacists’ core roles in therapy selection, ongoing medication management, and monitoring/management of adverse effects, underscoring pharmacist leadership in toxicity surveillance and actioning [24]. Empirical safety work shows that pharmacist-designed verification tools embedded in computerized provider order entry (CPOE), such as an electronic chemotherapy order-verification (ECOV) checklist fit naturally into sequential pharmacist evaluation. These tools have been shown to increase capture of reportable medication errors (i.e., “good catches”), reinforcing the value of structured, review-ready outputs for adjudication [25]. Historical and contemporary evidence further demonstrates that oncology medication errors are common and clinically significant without robust verification, motivating pharmacist-centered surveillance and decision support [26,27,28]. Finally, the CTCAE framework (and American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy or ASTCT grading for cellular therapies) is the prevailing standard for toxicity severity and management, justifying our emphasis on CTCAE-aligned, provenance-backed outputs rather than unconstrained free-text [6,29].

In this narrative review, we synthesize empirical studies from 2018 onward that utilize LLM techniques on text data in oncology settings. Our review comprises retrospective analyses, prospective vignette/simulation work, and prospective real-world deployments. Our objective is to describe how these systems are being used for oncology-pharmacy safety decisions (AE detection, CTCAE grading, and grade-aligned actions), to assess the strength and limits of the reported evidence, and to clarify the data and design conditions under which they appear reliable enough for pharmacist-in-the-loop use. In doing so, we make three contributions: we consolidate what is known about model performance across detection, grading, and actioning; we identify practice-relevant gaps (especially limited reporting of grade-to-action correctness and prospective impact); and we translate the evidence into pharmacist-centered recommendations and integration patterns aimed at order-level safety. Please refer to Table 1 for the acronyms and the Glossary of terms to better understand our study.

Table 1.

Glossary of terms and acronyms with full meaning.

2. Methodology

2.1. Scope of Review (Inclusion and Exclusion)

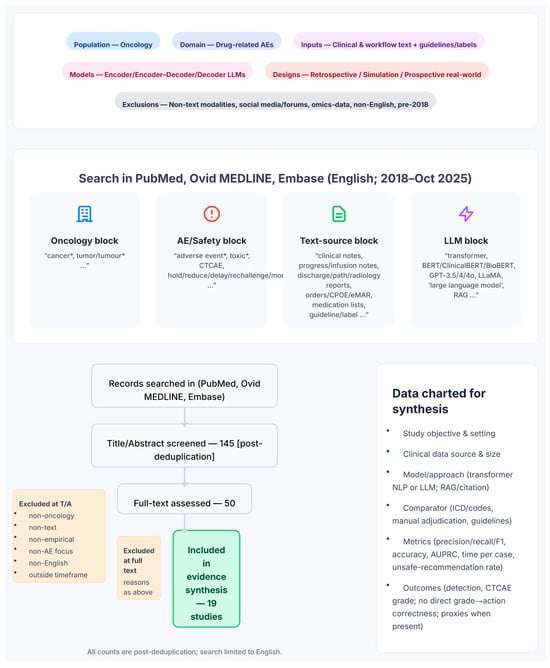

This narrative review focuses on oncology-pharmacy safety decisions for the oncology patient population, limited to one domain: drug-related AEs. In contrast to systematic reviews, which employ stringent inclusion criteria and aim to comprehensively encompass all relevant literature, our narrative review utilizes a more flexible and interpretive approach [30,31]. We include empirical studies that applied LLMs (encoder-only transformers, encoder–decoder models, and decoder-only/generative LLMs) as well as techniques such as citation-enforced RAG [21,32]. Studies that utilized only NLP methods without incorporating transformers/LLMs were excluded from the analysis. The included studies focus on various aspects of AE extraction, ranging from methodology development for AE detection to CTCAE grade assignment or grade-aligned actions (hold, reduce, delay, rechallenge, or monitor). Included inputs for the LLMs comprise clinical narratives and workflow text (physician/clinic/infusion notes, telephone encounters, discharge summaries, pathology/radiology reports, orders/CPOE/electronic medication administration record or eMAR, medication lists) as well as authoritative reference text such as guidelines or labels. Non-text modalities (e.g., imaging, waveforms, omics) along with social media/forums and bulk pharmacovigilance narratives are excluded from this study. We include empirical evaluations, which encompass retrospective analyses, prospective vignette/simulation studies, and prospective real-world deployments. Our review includes only articles written in the English language from 2018 to October 2025 (the transformer/LLM era), encompassing peer-reviewed articles, abstracts, and preprints [32,33]. The methodology for this review, including the search strategy, study selection process, and data extraction protocol, is visually summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodology for our narrative review. The infographic provides a visual summary of the search strategy, study selection process, and data extraction protocol. A systematic search of PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, and Embase (from January 2018 to October 2025) was conducted using queries constructed from four conceptual blocks (oncology, AE/safety, text source, and LLM terms). The study selection funnel illustrates the screening process, starting from 145 records assessed at the title/abstract level down to the 19 studies included in the final evidence synthesis. The key data points charted from each study are outlined, and the review’s overall scope and exclusion criteria are defined.

2.2. Article Selection, Literature Search, and Review

We performed a structured search of PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, and Embase (2018–October 2025) using four Boolean blocks combined with AND and OR in the Title/Abstract section. Those four Boolean blocks included an oncology block (e.g., cancer, tumor), a safety block focused on adverse events (e.g., adverse event, toxicity, CTCAE), a text-source block (e.g., clinical notes, discharge/pathology/radiology reports, authoritative guidelines/labels), and an LLM block (transformer/LLM terms spanning encoder-only, encoder–decoder, generative models and RAG, with common model names and synonyms). A typical Title/Abstract Boolean structure was: (cancer OR oncology OR malignant) AND (“large language model*” OR LLM* OR “language model*” OR “generative AI” OR “generative model*” OR “GPT-4” OR “GPT-3” OR ChatGPT OR BERT OR Longformer OR LLaMA OR “Med-PaLM” OR Gemini OR Claude OR RAG OR “retrieval-augmented”) AND (guideline* OR NCCN OR ASCO OR ESMO OR “tumor board” OR “electronic health record*” OR EHR OR “clinical note*” OR “discharge summar*” OR “progress note*” OR “triage note*” OR “pathology report*” OR “radiology report*”) AND (“adverse event*” OR toxicity OR toxicities OR AE OR AEs OR CTCAE OR “Common Terminology Criteria”). All three databases were last accessed on 10 October 2025. Searches were limited to articles that were published in English (However, the data analyzed in those articles may originate from other languages, such as Japanese.); duplicates across databases were removed. Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and, for potentially eligible records, full-text articles and extracted data using a structured form, resolving disagreements by discussion. This yielded 145 records based on title/abstract for manual review. Fifty records passing this stage underwent full-text manual review for final selection. The final evidence set comprises 19 studies, which serve as the sole basis for synthesis and discussion in this review.

3. Results

Overview of Selected Articles

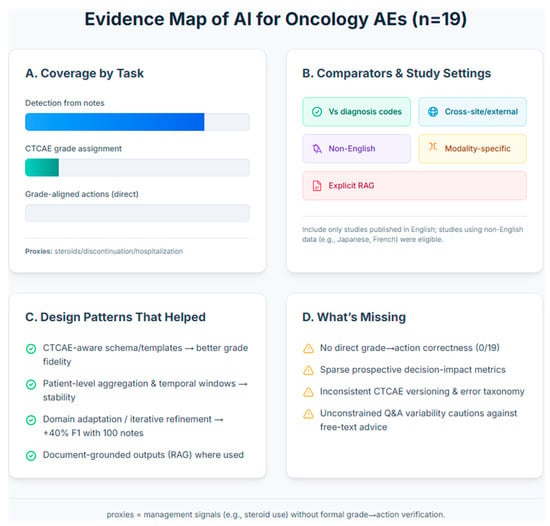

The final evidence set comprises 19 empirical studies (Table 2). These studies are oncology-focused and evaluate LLMs on text data for drug-related AEs. Across the set, most studies focused on AE detection from clinical narratives (clinic/infusion progress notes, follow-ups, often with discharge, pathology, or radiology reports), while a smaller subset evaluated CTCAE grade assignment. No study directly evaluated grade-aligned actions against CTCAE or local policy. However, a few studies reported proximal management signals (e.g., steroid initiation) rather than verifying hold/reduce/delay/rechallenge/monitor. Inputs were predominantly EHR narratives, with several studies using CTCAE/guideline excerpts or expert adjudication as the reference standard; some systems incorporated citation-oriented retrieval, CTCAE-aware prompting, and structured output schemas. Model approaches spanned encoder transformers (e.g., BERT-family classifiers) and generative LLMs, with study designs ranging from retrospective cohorts to prospective vignette/simulation and limited prospective real-world evaluations. Reported endpoints centered on precision/recall/F1 for detection and accuracy for grading; decision-impact metrics (e.g., time per case, acceptance/override, unsafe-recommendation rate) were inconsistently reported, and grade-to-action correctness was not measured. Figure 3 shows the evidence map summary.

Table 2.

Summary of 19 articles. For the acronyms, please see Table 1.

Figure 3.

Evidence Map of AI for AE assessment in oncology. This infographic summarizes the landscape of 19 studies on AI-based assessment of oncology AEs from text data. The evidence shows a strong focus on AE detection from clinical notes, with significantly less attention on assigning CTCAE grades Panel (A). The research landscape is characterized by limited cross-site validation and minimal use of explicit RAG techniques Panel (B). Key successful design patterns include using CTCAE-aware schemas for better grade fidelity and patient-level data aggregation for stability Panel (C). Major gaps remain in validating grade-to-action correctness, measuring prospective decision impact, and standardizing error taxonomies across studies Panel (D).

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of the Selected Articles

4.1.1. What’s Most Mature: AE Detection from Clinical Narratives

Across the evidence set, the most consistent signal is that transformer/LLM pipelines can identify oncology adverse events from routine clinical text with usable accuracy, often exceeding diagnosis codes for surveillance or cohort-building in multiple cohorts. Multi-institutional work with GPT-3.5/4/4o achieved patient-level micro-F1 ≈ 0.56–0.59 across two centers (VUMC, UCSF), with organ-category micro-F1 ≈ 0.61–0.66 after simple aggregation, demonstrating evidence of cross-site generalizability for irAE phenotyping from notes [36]. LLM-assisted “augmented curation” outperformed diagnosis codes for immune-related AEs and captured steroid use as an action proxy (F1 ≈ 0.84; steroid use ≈82%) [35]. In a broader irAE pipeline comparison, the LLM approach reported higher sensitivity/PPV/NPV than ICD coding and compressed chart-review time from ~9 weeks to ~10 min for ~9000 patients, underscoring scalability for safety surveillance [51]. A separate prospective comparison versus ICD demonstrated a mean sensitivity of ≈95% (specificity ≈ 94%) at the encounter level but low PPV (~15%), arguing that LLM outputs are best used as triage cues rather than final labels [52].

In practical terms, these AE-detection systems all tackle a similar problem: turning free-text oncology documentation into patient- or encounter-level flags that one or more CTCAE-defined toxicities are present in a clinically relevant time window around treatment. Most pipelines utilize oncology progress notes, discharge summaries, radiology or nursing documentation, and use LLM-based classification or extraction to map those narratives to binary or multi-label AE indicators, sometimes with simple rules layered on top. Reference standards are typically manual chart review or curated irAE/toxicity cohorts, and several groups explicitly compare against diagnosis-code–only baselines, showing that note-based models consistently recover hidden true events at acceptable precision. This convergence across immune-checkpoint inhibitors, radiotherapy toxicities, and broader oncology AEs is what makes detection from clinical narratives the most empirically mature use case in this literature, even though downstream grading and treatment-action recommendations still require human oversight.

Collectively, these results support a “detect-to-triage-to-adjudicate” role for LLMs in oncology pharmacovigilance. High recall surfaces candidate cases, while pharmacists (or trained abstractors) adjudicate details, an operational pattern that several groups explicitly highlight in their “Clinical Impact/Advancements” statements [35,36,51,52].

4.1.2. From Detection to Grading: CTCAE Alignment Is Feasible but Harder

Moving from “did an AE occur?” to “how bad is it?” consistently reduces performance, yet multiple studies show that CTCAE-aware templates or task-specific training make the step tractable. In radiation-oncology notes and reports, a classifier achieved macro-F1 ≈ 0.92/0.82/0.73 across progressively more challenging esophagitis grading tasks (note-, series-, patient-level), providing one of the clearest demonstrations of automatic CTCAE severity extraction from routine text [39]. A GPT-4–based classifier obtained ~82–86% accuracy for general chemotherapy-related toxicity classes, but performance fell for fine-grained grades (0–4), a pattern consistent with the narrative that coarse category mapping is easier than exact grade calls [38]. Predictive modeling over longitudinal oncology notes also reached macro-AUPRC ≈ 0.58 for common symptomatic toxicities (nausea/vomiting, fatigue/malaise), outperforming an open-source baseline and suggesting value for early-warning workflows that feed pharmacist review [48]. Together, these studies indicate that grade mapping is feasible, but reliability depends on anchoring to CTCAE language, careful time-windowing, and (often) specialty-specific corpora [38,39,48].

4.1.3. Toward Grade-Aligned Actions: Early Signals, Limited Direct Evaluation

Far fewer studies evaluate actions (hold/reduce/delay/rechallenge/monitor) directly, but several provide proximal evidence. An augmented-curation pipeline quantified steroid initiation for irAEs, linking detection to a management action [35]. A large irAE cohort reported real-world management actions (e.g., steroid percentages) alongside detection metrics, illustrating how LLM pipelines can instrument downstream care [51]. Another prospective comparison highlighted that, although recall was high, precision was modest, reinforcing the need for structured, review-ready outputs (e.g., explicit grade and action candidates with provenance) before order changes are made [52]. In sum, action correctness is under-reported across the literature; most studies stop at detection or grade, with only a few quantifying grade-to-action or using action proxies (steroids). This gap motivates the recommendations we present later.

4.1.4. Modality-Specific Toxicity Use Cases (CAR-T, Radiotherapy, Antibody–Drug Conjugates)

LLM-based systems are already probing modality-specific safety needs. In cellular therapy, GPT-4 extracted CAR-T–related AEs with ~64% manual-validation accuracy and identified clusters (e.g., encephalopathy/neurologic) at a ~13-day post-infusion mean, promising for post-CAR-T monitoring despite remaining headroom [43]. For late radiation toxicities, a teacher–student LLM pipeline reached overall accuracies ~84% after per-symptom refinement, supporting longitudinal survivorship surveillance [42]. In antibody–drug conjugate safety (trastuzumab deruxtecan), a BERT-based note classifier plus clinical review surfaced interstitial lung disease events (n = 16) and linked them to management outcomes, illustrating combined algorithmic and clinician workflows for high-risk drug AEs [40].

4.1.5. Non-English and Cross-System Generalizability

Several studies demonstrate feasibility beyond English and across disparate care settings. Japanese pharmacy and hospital notes supported ADE NER and normalization with patient-level precision ≈0.88, recall 1.00 (F1 ≈ 0.93) for a capecitabine-induced hand–foot syndrome use case, and broader symptomatic AE detection with exact-match F1 ≈ 0.72–0.86 [44,46]. Two large studies emphasized cross-site performance: ClinicalBERT transferred between institutional corpora with F-score ~0.74–0.78 and achieved ~0.87 within-dataset [50], while organ-category irAE performance replicated across VUMC/UCSF cohorts [36]. Notably, where the text comes from matters, detectability of certain AEs varied by note source (e.g., oncology vs. pharmacy notes), a pragmatic insight for deployment planning [46,47].

Overall, the studies above, particularly on non-English datasets, are valuable stress tests, but they also highlight limits on generalizability. Models trained on a single language and site-specific documentation style (e.g., templated radiology reports, local abbreviations, or institution-specific note structures) may overfit to those patterns and perform less well when applied to English notes, different EHR vendors, or community settings. Such shifts can introduce hidden bias in adverse event detection if certain toxicities are described differently or under-documented in new environments. Future work should therefore report cross-language and cross-system validation, or explicitly use adaptation (e.g., translation, local fine-tuning) before deploying these systems for safety-critical oncology pharmacy decisions.

4.1.6. Guardrails and Design Patterns That Helped

Across studies, three patterns recur when performance and usability improved:

- (a)

- Task-specific schemas or CTCAE-aware prompting. Making the model “speak CTCAE” via templates or label spaces improved grade fidelity and interpretability [38,39].

- (b)

- Patient-level aggregation and temporal anchoring. Aggregating sentence- or note-level signals to the patient timeline (and constraining to clinically plausible windows) stabilized performance across sites [36].

- (c)

- Retrieval/citation and domain adaptation. Systems that incorporated citation-style retrieval or modest domain-adaptation (e.g., small in-domain labels) reported sizeable gains, for instance, +40% F1 with 100 annotated notes versus zero-shot [44] and improved precision for post-RT symptoms after per-symptom refinement [42].

By contrast, generic Q&A without constraints showed omissions and variability for safety content: GPT-4 answered AE questions correctly only ~53% of the time, with 76% answer variability on repeats, underscoring the need for structured outputs, retrieval, and verification in clinical safety contexts [45]. Even in stronger pipelines, recall-heavy behavior can depress PPV (e.g., PPV ≈ 15% in a high-sensitivity irAE screen), again arguing for pharmacist triage before action [52].

4.1.7. Scale, Workload, and “Fit for Use”

Several groups quantified workflow impact or scale: one pipeline processed ~9000 patients in ~10 min, turning an otherwise infeasible manual review into a tractable queue for human adjudication [51]. Others framed their contribution as registry or real-world evidence enablement. For example, studies demonstrate capturing post-treatment symptom recurrence and complications with recall ~100% (local recurrence) and F1 ≈ 0.80 (pneumothorax) for key events [41], or prospective monitoring where early-warning predictions can focus team attention [43,48]. Importantly, multiple studies emphasize that the intended use matters: systems with high recall and explainable outputs are “fit” for surveillance and triage, whereas grade-to-action automation requires CTCAE-anchored structure, tighter precision, and explicit provenance [35,39,52].

4.1.8. What Remains Under-Reported

Two gaps cut across the literature. First, grade-aligned action correctness is measured infrequently; steroids serve as a proxy in a few irAE cohorts, but comprehensive evaluation of hold/reduce/delay/rechallenge/monitor recommendations is rare [35,51]. Second, unsafe-recommendation taxonomies and versioning of CTCAE/guidelines are inconsistently reported, limiting reproducibility and auditability [multiple studies’ “Clinical Impact/Advancements” notes]. Addressing these will be central to moving from surveillance to order-level decision support.

5. Future Directions

5.1. Start with Surveillance and Triage

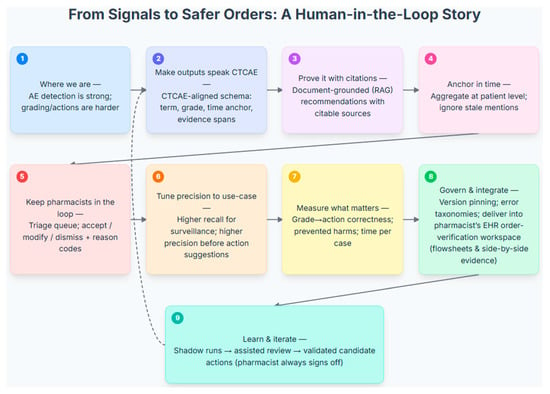

Consistent with the scope defined in the Introduction, the most reliable use of LLMs today is AE detection from routine oncology narratives, with more variable performance for CTCAE grading and limited evaluation of grade-aligned actions. Accordingly, initial deployment should position the model as a surveillance/triage service that sweeps clinic, infusion, and follow-up notes to surface high-recall AE candidates. Outputs should be delivered into the pharmacist’s EHR order-verification workspace as review items rather than as order-changing directives, leveraging sensitivity without compromising safety or accountability. Figure 4 illustrates various aspects of future directions and recommendations, as well as their interconnections from signals to safer orders with a human-in-loop.

Figure 4.

A Human-in-the-Loop Workflow for Processing Adverse Event Signals into Actionable Clinical Recommendations. This figure illustrates a nine-step, human-in-the-loop workflow that translates AE signals into safe, pharmacist-verified clinical actions. The process begins by structuring raw AE data into a clinically relevant format by aligning it with a CTCAE schema, grounding recommendations in citable sources (RAG), and aggregating timely patient-level data (Steps 1–4). A pharmacist provides essential oversight by reviewing, modifying, or dismissing all system-generated suggestions in a dedicated triage queue (Step 5). The system’s precision is tuned to the clinical use-case, and its performance is measured by the correctness of grade-to-action mapping, prevented harms, and time per case (Steps 6–7). Designed for robust deployment, the model integrates into the pharmacist’s EHR workspace (Step 8) and is underpinned by an iterative learning model. A continuous feedback loop (Step 9 to 2) allows the system to learn from pharmacist decisions, while the clinician always retains final sign-off authority.

5.2. Make Outputs Speak CTCAE

For efficient review and documentation, model outputs should follow a CTCAE-aligned schema: toxicity term, proposed grade, temporal anchor (onset/resolution), and the specific evidence span(s) supporting the call. Constraining results to this structure converts free-text claims into reviewable objects, reduces ambiguity, and shortens the path from “possible AE” to a pharmacist determination of actionability during order-verification.

5.3. Prove Recommendations with Citations

Whenever grade-aligned suggestions are offered (hold, reduce, delay, rechallenge, monitor), recommendations should be document-grounded. Retrieval-augmented prompts should display the exact supporting note excerpt. Additionally, where relevant, they should show the corresponding CTCAE passage or versioned local policy (with date/source), providing the provenance required for clinical trust. The model assembles and cites the evidence; pharmacists retain judgment and final sign-off.

5.4. Anchor in Time and at the Patient Level

AE interpretation is inherently temporal. Systems should aggregate sentence- and note-level signals to the patient level, suppress stale/problem-list mentions, and constrain evidence to clinically plausible windows (e.g., cycle-aligned day ranges, steroid taper periods). Temporal anchoring reduces false positives from historical or duplicate statements and clarifies whether the toxicity is active. Pharmacist review then confirms clinical relevance before any order change is considered.

5.5. Keep Pharmacists in the Loop by Design

A pharmacist-in-the-loop workflow should be explicit and embedded in routine order verification, not treated as an optional safety check. Model outputs should enter a dedicated pharmacist review queue within the EHR order-verification workspace, where each item presents a structured summary of the suspected AE episode (drug/regimen, CTCAE term and grade, temporal window, and supporting evidence spans) and any candidate actions (hold/reduce/delay/rechallenge/monitor). Pharmacists review these items and can accept, modify, or dismiss suggestions, with high-risk scenarios (e.g., grade ≥ 3 toxicities or narrow-therapeutic-index agents) always requiring pharmacist confirmation before any order change.

Each decision should be accompanied by concise reason codes (e.g., not active, wrong grade, not drug-related, insufficient evidence, conflicts with local protocol). This preserves a human safety gate, generates supervision signals for iterative model improvement, and creates an auditable link between model outputs and order-level decisions. Mapping reason codes to a compact error taxonomy (wrong fact, misapplied rule, temporal error, hallucination) enables targeted updates and governance. In this design, the model compiles and structures the evidence, but the pharmacist remains the operating control and final sign-off authority for therapy decisions.

5.6. Tune Precision to the Intended Use

Operating points shape workload and trust. High recall with modest PPV is appropriate for surveillance queues, whereas “ready-to-recommend” suggestions require higher precision. Thresholds should be co-determined with pharmacists and periodically recalibrated using acceptance/override rates and observed error types, with thresholds tailored by AE category (e.g., stricter for high-risk toxicities) to align model behavior with the intended role in order verification.

5.7. Measure Decision Impact, Not Detection Alone

Prospective evaluations should report endpoints that reflect decision quality and safety: grade-to-action correctness against a specified CTCAE version or local policy; prevented harms (e.g., averted grade ≥ 3 progression before administration); and operational metrics (pharmacist time per case, alert burden, acceptance/override, secondary review requests). These measures demonstrate improvement beyond detection accuracy and are essential for practice adoption.

5.8. Standardize Versioning and Error Taxonomies

Reproducibility requires consistent reporting and version pinning (CTCAE, prompts, model weights, retrieval corpora). Implementations should specify the CTCAE version and any guideline/label versions/dates, describe the reference-standard process (e.g., expert adjudication procedures and agreement), and classify unsafe recommendations with a compact taxonomy (wrong fact, misapplied rule, temporal error, hallucination). Standardization enables meaningful comparison, governance, and audit.

5.9. Build Pharmacist-Centric Benchmarks

To align development with pharmacy work, curate de-identified benchmarks containing CTCAE-labeled spans, patient-level AE episodes with temporal boundaries, and action labels (hold/reduce/delay/rechallenge/monitor), stratified by note type. Such datasets allow evaluation of what ultimately determines order-level decisions, not just detection or grade.

5.10. Integrate and Govern Before You Automate

Delivering outputs into the pharmacist’s EHR order-verification workspace as structured artifacts (e.g., flowsheet rows or AE entries) with side-by-side evidence. Governance should include version pinning for CTCAE and local guidance, change logs for prompts/models/sources, and fail-safe defaults (no action suggested when confidence or provenance is inadequate). Rollouts should progress from silent mode to assisted review, and only then to limited candidate-action pilots, always retaining pharmacist sign-off.

5.11. Test Generalizability and Equity

Validate systems across institutions, note styles, and populations (including non-English notes where relevant), with routine monitoring for performance disparities by age, sex, race/ethnicity, language, regimen, and care setting. Pharmacist feedback should guide targeted adaptation when subgroup gaps are detected. The objective is not only high average performance but reliability across patient groups and care settings, consistent with the pharmacist-centered goals defined in the Introduction.

6. Conclusions

This review of 19 empirical studies demonstrates that AI on text data has the potential for adverse-event surveillance in oncology and can help to reduce the effort required to surface clinically relevant signals from narrative notes. Detection is the most mature capability; CTCAE grading is achievable when the task is constrained to structured outputs and temporally anchored. These findings align closely with contemporary oncology pharmacy workflow: AI compiles the evidence, and the pharmacist verifies and determines the course of action before any order change. Thus, for practice, the safest and most impactful role for LLM-based systems is as pharmacist-in-the-loop tools that surface candidate AEs, provide CTCAE-aligned summaries with citations, and support triage rather than autonomous order changes. The field now needs prospective and multi-center evaluations that report grade-to-action correctness, prevented harms, time-per-case, and pharmacist acceptance/override, along with consistent CTCAE versioning and transparent governance. With these guardrails, LLMs can help oncology pharmacists act faster and more consistently, while keeping therapy decisions under human control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.Z.; methodology, M.M.Z. and S.B.; software, M.M.Z.; validation, S.B., A.M., W.B.R. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, M.M.Z.; investigation, M.M.Z. and S.B.; data curation, M.M.Z. and Y.Z.; original draft preparation, M.M.Z.; writing, review and editing, M.M.Z., W.B.R., A.M., S.B. and Y.Z.; visualization, M.M.Z., Y.Z. and W.B.R.; supervision, M.M.Z. and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors used ChatGPT, an AI-based language tool, to assist with editing part of the manuscript for clarity and readability.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Siegel, R.D.; LeFebvre, K.B.; Temin, S.; Evers, A.; Barbarotta, L.; Bowman, R.M.; Chan, A.; Dougherty, D.W.; Ganio, M.; Hunter, B.; et al. Antineoplastic Therapy Administration Safety Standards for Adult and Pediatric Oncology: ASCO-ONS Standards. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2024, 20, 1314–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingart, S.N.; Zhang, L.; Sweeney, M.; Hassett, M. Chemotherapy medication errors. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, e191–e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashed, A.; Zhang, S.; Chiang, C.-W.; Zitu, M.; Otterson, G.A.; Presley, C.J.; Kendra, K.; Patel, S.H.; Johns, A.; Li, M.; et al. Comparative assessment of manual chart review and ICD claims data in evaluating immuno-therapy-related adverse events. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII 2021, 70, 2761–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hematology/Oncology Pharmacy Association. (n.d.). HOPA Issue Brief on Hematology/Oncology Pharmacists [Issue Brief]. Available online: https://www.hoparx.org/documents/78/HOPA_About_Hem_Onc_Pharmacist_Issue_Brief_FINAL1.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Shah, S. Common terminology criteria for adverse events. Natl. Cancer Inst. USA 2022, 784, 785. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.W.; Santomasso, B.D.; Locke, F.L.; Ghobadi, A.; Turtle, C.J.; Brudno, J.N.; Maus, M.V.; Park, J.H.; Mead, E.; Pavletic, S.; et al. ASTCT Consensus Grading for Cytokine Release Syndrome and Neurologic Toxicity Associated with Immune Effector Cells. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. J. Am. Soc. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019, 25, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.K.; Turtle, C.J. Assessment and management of cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity following CD19 CAR-T cell therapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Santomasso, B.D.; Lacchetti, C.; Adkins, S.; Anadkat, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Check-point Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 4073–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Lacchetti, C.; Schneider, B.J.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Gardner, J.M.; Ginex, P.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1714–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzanov, I.; Diab, A.; Abdallah, K.; Bingham, C.O., 3rd; Brogdon, C.; Dadu, R.; Hamad, L.; Kim, S.; Lacouture, M.E.; LeBoeuf, N.R.; et al. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: Consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-C.; Wu, C.-M.; Chien, T.-N.; Kao, L.-J.; Li, C.; Chu, C.-M. Integrating Structured and Unstructured EHR Data for Predicting Mortality by Machine Learning and Latent Dirichlet Allocation Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro-Calduch, E.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Krishnamurthy, R.S.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. Technological progress in electronic health record system optimization: Systematic review of systematic literature reviews. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 152, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitu, M.; Gatti-Mays, M.; Johnson, K.; Zhang, S.; Shendre, A.; Elsaid, M.; Li, L. Detection of Patient-Level Immunotherapy-Related Adverse Events (irAEs) from Clinical Narratives of Electronic Health Records: A High-Sensitivity Artificial Intelligence Model. Pragmatic Obs. Res. 2024, 15, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Belouali, A.; Shah, N.J.; Atkins, M.B.; Madhavan, S. Automated Identification of Patients With Immune-Related Adverse Events From Clinical Notes Using Word Embedding and Machine Learning. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2021, 5, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitu, M.; Li, L.; Elsaid, M.I.; Gatti-Mays, M.E.; Manne, A.; Shendre, A. Comparative assessment of manual chart review and patient-level adverse drug event identification using artificial intelligence in evaluating immunotherapy-related adverse events (irAEs). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, e13583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannantuono, G.M.; Bracken-Clarke, D.; Floudas, C.S.; Roselli, M.; Gulley, J.L.; Karzai, F. Applications of large lan-guage models in cancer care: Current evidence and future perspectives. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1268915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Mou, W.; Chen, R. Can the ChatGPT and other large language models with internet-connected database solve the questions and concerns of patient with prostate cancer and help democratize medical knowledge? J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, V.; Klang, E.; Sklair-Levy, M.; Cohen, I.; Zippel, D.B.; Lahat, N.B.; Konen, E.; Barash, Y. Large language model (ChatGPT) as a support tool for breast tumor board. NPJ Breast Cancer 2023, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitu, M.; Le, T.D.; Duong, T.; Haddadan, S.; Garcia, M.; Amorrortu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Rollison, D.E.; Thieu, T. Large language models in cancer: Potentials, risks, and safeguards. BJR Artif. Intell. 2024, 2, ubae019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.V. Accuracy, consistency, and hallucination of large language models when analyzing unstructured clinical notes in electronic medical records. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2425953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozuka, R.; Johno, H.; Amakawa, A.; Sato, J.; Muto, M.; Seki, S.; Komaba, A.; Onishi, H. Application of NotebookLM, a large language model with retrieval-augmented generation, for lung cancer staging. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2024, 43, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskó, B.; Topol, E.J. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuss, M.N.; Gilmore, T.R.; Belderson, K.M.; Billett, A.L.; Conti-Kalchik, T.; Harvey, B.E.; Hendricks, C.; LeFebvre, K.B.; Mangu, P.B.; McNiff, K.; et al. 2016 Updated American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society Chemotherapy Administration Safety Standards, Including Standards for Pedi-atric Oncology. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackler, E.; Segal, E.M.; Muluneh, B.; Jeffers, K.; Carmichael, J. 2018 Hematology/Oncology Pharmacist Association Best Practices for the Management of Oral Oncolytic Therapy: Pharmacy Practice Standard. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, e346–e355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wat, S.K.; Wesolowski, B.; Cierniak, K.; Roberts, P. Assessing the impact of an electronic chemotherapy order ver-ification checklist on pharmacist reported errors in oncology infusion centers of a health-system. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 31, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranchon, F.; Salles, G.; Späth, H.-M.; Schwiertz, V.; Vantard, N.; Parat, S.; Broussais, F.; You, B.; Tartas, S.; Souquet, P.J.; et al. Chemotherapeutic errors in hospitalised cancer patients: Attributable damage and extra costs. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichtig, K.; Dürr, P.; Dörje, F.; Fromm, M.F. Medication Errors During Treatment with New Oral Anticancer Agents: Consequences for Clinical Practice Based on the AMBORA Study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 110, 1075–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentie, A.M.; Huluka, S.A.; Gebremariam, G.T.; Gebretekle, G.B.; Abebe, E.; Fenta, T.G. Impact of pharmacist-led interventions on medication-related problems among patients treated for cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 2024, 20, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennisi, M.; Jain, T.; Santomasso, B.D.; Mead, E.; Wudhikarn, K.; Silverberg, M.L.; Batlevi, Y.; Shouval, R.; Devlin, S.M.; Batlevi, C.; et al. Comparing CAR T-cell toxicity grading systems: Application of the ASTCT grading system and implications for management. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zitu, M.; Owen, D.; Manne, A.; Wei, P.; Li, L. Large Language Models for Adverse Drug Events: A Clinical Per-spective. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Lin, H.; Jiang, J.; Jinia, A.J.; Jee, J.; Pichotta, K.; Waters, M.; Rose, D.; Schultz, N.; Chalise, S.; et al. Large language model trained on clinical oncology data predicts cancer progression. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.04805 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Bakouny, Z.; Ahmed, N.; Fong, C.; Rahman, A.; Perea-Chamblee, T.; Pichotta, K.; Waters, M.; Fu, C.; Jeng, M.Y.; Lee, M.; et al. Use of a large language model (LLM) for pan-cancer automated detection of anti-cancer therapy toxicities and translational toxicity research. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, H.; Venkateswaran, S.; Del Santo, A.; Yoo, U.; Silvert, E.; Rao, K.; Raghunathan, B.; Kottschade, L.A.; Block, M.S.; Chandler, G.S.; et al. Identification and characterization of immune checkpoint in-hibitor-induced toxicities from electronic health records using natural language processing. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2024, 8, e2300151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, C.A.; Wang, M.; Venkateswaran, S.; Bergmann, E.A.; Hiles, L.; Xu, Y.; Chandler, G.S.; Brondfield, S.; Silverstein, J.; Wright, F.; et al. irAE-GPT: Leveraging large language models to identify immune-related adverse events in electronic health records and clinical trial datasets. medRxiv 2025. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnette, H.; Pabani, A.; von Itzstein, M.S.; Switzer, B.; Fan, R.; Ye, F.; Puzanov, I.; Naidoo, J.; Ascierto, P.A.; Gerber, D.E.; et al. Use of artificial intelligence chatbots in clinical management of immune-related adverse events. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e008599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Sarrias, O.; Martínez Del Prado, M.P.; Sala Gonzalez, M.Á.; Azcuna Sagarduy, J.; Casado Cuesta, P.; Figaredo Berjano, C.; Galve-Calvo, E.; López de San Vicente Hernández, B.; López-Santillán, M.; Nuño Escolástico, M.; et al. Leveraging large language models for precision monitoring of chemotherapy-induced toxicities: A pilot study with expert comparisons and future direc-tions. Cancers 2024, 16, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Guevara, M.; Ramirez, N.; Murray, A.; Warner, J.L.; Aerts, H.J.W.L.; Miller, T.A.; Savova, G.K.; Mak, R.H.; Bitterman, D.S. Natural language processing to automatically extract the presence and severity of esophagitis in notes of patients undergoing radiotherapy. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2023, 7, e2300048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumsri, S.; O’SUllivan, C.; Goldberg, H.; Venkateswaran, S.; Silvert, E.; Wagner, T.; Poppe, R.; Genevray, M.; Mohindra, R.; Sanglier, T. Utilizing natural language processing to examine adverse events in HER2+ breast cancer patients. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geevarghese, R.; Solomon, S.B.; Alexander, E.S.; Marinelli, B.; Chatterjee, S.; Jain, P.; Cadley, J.; Hollingsworth, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Ziv, E. Utility of a large language model for extraction of clinical findings from healthcare data following lung ablation: A feasibility study. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2024, 36, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem, A.I.; Khanmohammadi, R.; Verdecchia, K.; Hall, R.; AElshaikh, M.; Movsas, B.; Bagher-Ebadian, H.; Chetty, I.; Ghassemi, M.M.; Thind, K. Late Radiotherapy-related Toxicity Extraction From Clinical Notes Using Large Language Models for Definitively Treated Prostate Cancer Patients, 107th Annual Meeting of the American Radium Society, ARS 2025. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 48, S1–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, J.; Miao, B.; Suresh, A.; Williams, C.; Zack, T.; Wolf, J.L.; Butte, A. Constructing adverse event timelines for patients receiving CAR-T therapy using large language models. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. S16), 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman Bernardim Andrade, G.; Nishiyama, T.; Fujimaki, T.; Yada, S.; Wakamiya, S.; Takagi, M.; Kato, M.; Miyashiro, I.; Aramaki, E. Assessing domain adaptation in adverse drug event extraction on real-world breast cancer records. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2024, 191, 105539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundal, J.; Teplinsky, E. Results of the COMPARE-GPT study: Comparison of medication package inserts and GPT-4 cancer drug information. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e13646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Kawazoe, Y.; Shimamoto, K.; Seki, T.; Imai, S.; Kizaki, H.; Shinohara, E.; Yada, S.; Wakamiya, S.; Aramaki, E.; et al. Elucidating Celecoxib’s Preventive Effect in Capecitabine-Induced Hand-Foot Syndrome Using Medical Natural Language Processing. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2025, 9, e2500096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, M.; Shimamoto, K.; Kawazoe, Y.; Shinohara, E.; Yada, S.; Wakamiya, S.; Imai, S.; Kizaki, H.; Hori, S.; Aramaki, E. Natural Language Processing-Based Approach to Detect Common Adverse Events of Anticancer Agents from Unstructured Clinical Notes: A Time-to-Event Analysis. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2025, 329, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienne, R.; Filori, Q.; Susplugas, V.; Crochet, H.; Verlingue, L. Prediction of nausea or vomiting, and fatigue ormalaise in cancer care. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, Y.; Watabe, S.; Yokoyama, S.; Sayama, K.; Kizaki, H.; Tsuchiya, M.; Imai, S.; Someya, M.; Taniguchi, R.; Yada, S.; et al. Identifying Adverse Events in Outpatients With Prostate Cancer Using Pharmaceutical Care Records in Community Pharmacies: Application of Named Entity Recognition. JMIR Cancer 2025, 11, e69663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitu, M.M.; Zhang, S.; Owen, D.H.; Chiang, C.; Li, L. Generalizability of machine learning methods in detecting adverse drug events from clinical narratives in electronic medical records. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1218679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, M.S.; Barman, H.; Venkateswaran, S.; Del Santo, A.G.; Yoo, U.; Silvert, E.; Chandler, G.S.; Wagner, T.; Mohindra, R. The role of natural language processing techniques versus conventional methods to gain ICI safety insights from unstructured EHR data. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2023, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, V.H.; Heemelaar, J.C.; Hadzic, I.; Raghu, V.K.; Wu, C.-Y.; Zubiri, L.; Ghamari, A.; LeBoeuf, N.R.; Abu-Shawer, O.; Kehl, K.L.; et al. Enhancing Precision in Detecting Severe Immune-Related Adverse Events: Compara-tive Analysis of Large Language Models and International Classification of Disease Codes in Patient Records. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 4134–4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).