Abstract

This paper sets out to investigate the modal uses of the lexeme hɒ3 ‘good’ in the Jidong Shaoxing variety of Wu and to reconstruct its grammaticalization pathway. Modal meanings of hɒ3 include circumstantial possibility, deontic possibility and necessity, and epistemic possibility. These meanings can be summarized as ‘can’, ‘may’, and ‘should’, respectively. The modal meanings of hɒ3 are derived from its meaning of ‘fit to’ rather than ‘good’. We propose here that hɒ3 first extended to express circumstantial possibility, and then further extended to denote deontic modality and participant-internal possibility in two separate directions: (i) circumstantial possibility > deontic modality, and (ii) circumstantial possibility > participant-internal possibility. The epistemic use of hɒ3 is proposed as the final stage of the lexeme’s modal extension.

Keywords:

good; circumstantial possibility; deontic; epistemic; Shaoxing Wu; grammaticalization; extension 1. Introduction

Modality is a semantic domain concerning how languages code possibility and necessity. Languages may adopt different strategies to express modality, such as auxiliary verbs, morphological devices of mood, modal affixes, lexical means, modal adverbs and adjectives, modal tags, modal particles, and modal case (). While Sinitic languages are well known for lacking morphological mood, modality is expressed by auxiliary verbs, adverbs, and potential constructions, as well as particles. Among these devices, auxiliary verbs are the most common means of expressing possibility and necessity in Sinitic languages ().

Modal auxiliaries in Standard Mandarin can be divided into necessity and possibility modal verbs. Possibility modal verbs include hui⁴ 会 ‘can < know, comprehend’, ke3yi3 可以 ‘can, may < fit so as to’, and neng2 能 ‘can < capable’, while necessity modal verbs include dei3 得 ‘must < obtain’, gai1 该 ‘should < owe’, and yao⁴ 要 ‘need, must’. According to a survey by (), these are common modal verbs in Sinitic languages. Different Sinitic languages or dialects have developed various lexical sources into modal auxiliaries, for example, kuan⁴⁴ 管 ‘can < manage, supply’ in Fangcheng Central Plains Mandarin (), iəɯ22fɐʔ⁵ 有法 ‘can < have methods’ and ua⁵1 话 ‘can < say’ in Liujiang Jinde Hakka (), tɕʰieʔ⁵⁻33teʔ⁵⁻33loʔ2⁻⁵3 吃得落 ‘can < can eat’ in Shaoxing Wu (), and hao 好 ‘can < good’ in Jieyang Min () and Hakka (; ; ). In fact, hao ‘good’ has been adapted as a modal auxiliary in a contiguous area around the Yangtze River Delta. This phenomenon might be considered as a micro-areal phenomenon.

This paper will offer a case study on the modal uses of hɒ3 好 ‘good’ in the Jidong variety of Shaoxing Wu. First, a detailed synchronic description of the modal uses of hɒ3 ‘good’ in Jidong Shaoxing is given. This is followed by a diachronic reconstruction of the pathway of grammaticalization from ‘good’ to ‘can, may, should’ of hɒ3. Observation of hɒ3′s distribution indicates that its modal uses are derived from the auxiliary use of its meaning ‘fit to’ rather than directly from its meaning ‘good’. We find that in a grammatical sentence containing hɒ3, the situation expressed by the matrix VP is often enabled by an external or an internal condition. It is from this circumstantial possibility that the participant-internal possibility of hɒ3 is derived. Our finding contributes some new evidence in support of ’s () findings that circumstantial possibility may develop into participant-internal possibility and deontic possibility may extend to deontic necessity. The bidirectional developments ‘circumstantial ↔ participant-internal’ and ‘deontic possibility ↔ deontic necessity’ hold (). We also propose that the epistemic use of hɒ3 is derived from the uses of both circumstantial and participant-internal possibility. The semantic connection between the deontic and epistemic uses of hɒ3 is not obvious in Jidong Shaoxing, unlike the well-known deontic–epistemic polysemy of English must ().

Section 2 discusses the modality types distinguished in this paper. Section 3 presents background information and basic linguistic features of the target language. Section 4 introduces the polysemy of the lexeme hɒ3. Section 5 sets out to illustrate the modal uses of hɒ3. Section 6 aims to reconstruct the grammaticalization pathway of hɒ3 and offers a comparison with the diachrony of hao3 ‘good’ in the history of Chinese. Section 7 is a general conclusion.

2. Modality Types and Terminology

The domain of modality can be organized in several ways. Deontic, dynamic, and epistemic are the most broadly accepted concepts. () contrasts root modality, which comprises both dynamic and deontic, and epistemic modality. () oppose epistemic and non-epistemic (later revised as situational ()), with the latter subdivided into participant-internal and participant-external. () proposes an opposition of event modality (deontic and dynamic) and propositional modality (epistemic and evidential). () suggests volitive modal categories opposed to non-volitive modal categories. Given that a reorganization of our understandings of modality is not an aim of the current paper, here we adopt subcategories of modality solely on the basis of their relevance in describing the polysemy of hɒ3. Relevant modal concepts include:

- Circumstantial possibility

- Circumstantial possibility refers to a proposition enabled by certain external circumstances (). It can also be interpreted as a possibility allowed by external conditions, as in (1).

- (1)

- You can get to University City by taking subway line 9.

- Permission and weak obligation

- Both permission and obligation belong to deontic modality, also known as deontic possibility and necessity. Deontic modality refers to possibility or necessity determined by certain social norms, expectations, or a speaker’s desire or command (see ; ). Permission denotes that a participant is allowed to complete an action (), as in (2), while weak obligation means that a participant was advised to complete an action (). In English, weak obligation is usually expressed by should and ought, as in (3).

- (2)

- You may leave now.

- (3)

- You should leave now.

- Participant-internal possibility

- Participant-internal possibility refers to “a kind of possibility […] internal to a participant engaged in the state of affairs” and it covers dynamic possibility, ability, and capacity (), as in (4).

- (4)

- She can lift that heavy stone.

- Epistemic possibility

- Epistemic possibility refers to a speaker’s degree of certainty about a proposition (); see (5). Epistemic modality is generally relevant to knowledge, belief, and related notions.

- (5)

- The bus may be late (due to the snow).

3. Jidong Shaoxing and Some Basic Features

3.1. Variety under Investigation

Shaoxing 绍兴话 is a Northern Wu dialect of Sinitic belonging to the Linshao subdivision 临绍小片 of the Taihu division 太湖片 (). The variety under investigation, Jidong 稽东, is spoken in Jidong Town in the southern suburb of Shaoxing Prefecture and is classified as belonging to the Southern Suburb variety of Shaoxing ().

The data presented in this paper were collected with four native speakers from 2022 to 2023. Our consultants represented three generations within the same family. They were Mr. Huang Tangfu 黄汤富 (born in 1955), Mrs. Huang Xingqin 黄杏琴 (born in 1957), Mr. Huang Yongjiang 黄永江 (born in 1977), and the second author Mr. Huang Xiao 黄骁 (born in 2002). Mr. Huang Yongjiang speaks an innovative variety of Jidong Shaoxing, while the other three speak a conservative variety.

Our corpus included both spontaneous and elicited data. Spontaneous data illustrated in this paper were either extracted from a corpus of six hours of audio material or taken from unrecorded daily conversations which were not part of the corpus. Elicited data comprised about 130 sentences. Elicited data presented in this paper will be indicated as ‘elicitation’, while the data with unmarked sources were either from our corpus or the unrecorded daily conversations. It is worth mentioning that when performing elicitation we did not simply ask for translations from Standard Mandarin to Jidong Shaoxing. Instead, taking semantic nuances of modals into consideration, we provided different contexts as stimuli for our consultants.

3.2. Basic Features

Shaoxing possesses eight tones: Tone 1/33/, Tone 2/13/, Tone 3/435/, Tone 4/213/, Tone 5/52/, Tone 6/231/, Tone 7/4/, and Tone 8/23/. Tones 7 and 8 are two checked tones. Any syllable bearing Tone 7 or 8 ends with a glottal stop/ʔ/. We will hereafter refer to the tones with a superscript of the number by which the tone is named. Note that tone sandhi is not represented in our transcription. Shaoxing is basically a VO language, especially in dependent clauses and when an object appears with a complex modifier, as shown in (6). Wu languages are characterized by topic prominence () and constructions with topicalized objects are commonly observed in Shaoxing, as in (7). A topicalized object can occupy either a sentence initial position (7) or can follow the subject and precede the verb. As an analytic language, Shaoxing grammatical relations are realized by prepositions or word order. See example (6) for an example of a dative argument marked by the dative preposition pə⁷ ‘to’.

| (6) | 我拨侬讲讲□前头做生活种事体。 | |||||||||||||

| ŋo⁴ | pə⁷ | noŋ⁴ | kɒŋ3kɒŋ3 | ŋa⁴ | ʑjᴇ̃2də2 | tso⁵ | saŋ1ɦwo⁸ | tsoŋ3 | zɿ⁶tʰi3. | |||||

| 1sg | dat | 2sg | tell.dlm | 1pl | beforetime | do | life | clf | thing | |||||

| ‘I’ll tell you something about how (I) made a living before.’ | ||||||||||||||

| (7) | 榧子摘落来要囥得好。 | |||||||||||||

| fi3tsɿ3 | tsa⁷-lə⁸lᴇ2 | ʔjɒ⁵ | kʰɒŋ⁵-tə⁷-hɒ3. | |||||||||||

| Torreya | pick-fall.come | need | store-vcomp-good | |||||||||||

| ‘After picking the Torreya nuts, (they) must be well stored.’ | ||||||||||||||

() provides a detailed description of the Shaoxing grammatical system, though it focuses on the Keqiao 柯桥 variety, i.e., the Western Suburb variety, which is slightly different from the variety under investigation here.

3.3. Modal Auxiliaries and Potential Constructions

We summarize the distributional features of auxiliary verbs in Jidong Shaoxing following () and (). In Jidong Shaoxing, auxiliary verbs form a closed class of words. They are free elements taking verbal or clausal complements in the form of [AUX VP] which feature reduced verbal behaviors. Auxiliary verbs in Jidong Shaoxing cannot take any aspectual marking as verbs do.

In an auxiliary construction, the strategy V (NEG) V is applied to the auxiliary verb to form a polar question. An auxiliary verb can stand alone to answer a polar question. See the example below for a polar question formed with the auxiliary ɦwᴇ⁶ 会 ‘can’ and a positive response.

Some common Sinitic auxiliary verbs are used in Jidong Shaoxing. ɦwᴇ⁶ ‘can < know’ is used to express possibility, as in (8); ʔjɒ⁵ 要 ‘must, should < need’ is used to code necessity; and ɕjaŋ3 想 ‘want’ and kʰiŋ3 肯 ‘be willing’ are used to express willingness. While neng2 and ke3yi3 are used to denote possibility and permission in Standard Mandarin, these meanings are expressed by potential constructions and hɒ3 ‘can < good’ in Jidong Shaoxing.1 For this, see Table 1 and also ().

| (8) | 侬游水会会游{个□}?会{个□}。 | |||||||

| noŋ⁴ | ljɤ2sɿ3 | ɦwᴇ⁶ | ɦwᴇ⁶ | ljɤ2 | ɡɒ? | ɦwᴇ⁶ | ɡo⁸. | |

| 2sg | swim | can | can | swim | aff.prt | can | aff.prt | |

| ‘Can you swim? (Yes, I) can.’ (Elicitation) | ||||||||

Table 1.

Modal auxiliary verbs in Jidong Shaoxing.

Sinitic languages often adopt potential constructions to express possibility in the form of [V-POT-COMP], with [V-NEG-COMP] as the negated form (). In the negated form, the potential marker and the negator are considered as infixes (; ). In Jidong Shaoxing, potential constructions, V-tə⁷-COMP, are also commonly used to express possibility and are relevant to the modal uses of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing. When denoting ‘cannot’, it is a negated potential construction that is used rather than the negated hɒ3 ‘can’, fə⁸ hɒ3 ‘not good’. The most generalized potential construction is V-tə⁷-lᴇ2 ‘V-pot-come’, with V-və⁸-lᴇ2 ‘V-neg-come’ as the negated form. Both (9a) and (9b) can denote ‘cannot run’, with dɒ2-və⁸-lᴇ2 ‘run-neg-come’ having an additional meaning of prohibition.

| (9) | a. | 逃不动 | b. | 逃不来 |

| dɒ2-və⁸-doŋ⁴ | dɒ2-və⁸-lᴇ2 | |||

| run-neg-move | run-neg-come | |||

| ‘cannot run’ (Elicitation) | ‘cannot run’ (Elicitation) |

See Section 5 for more details.

4. Polysemy of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing

In Jidong Shaoxing, the lexeme hɒ3 好 is a polysemous and multi-functional word. hɒ3 can serve as an adjective/adjectival verb ‘good, fitting, ready, done, ok’, as an auxiliary verb ‘fit to, easy to, can, may, should’, as a resultative verb complement denoting a completed action, as an adverb ‘quite’, and as a complementizer introducing a purposive clause. The mentioned uses of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing are also attested in Standard Mandarin (), except that hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing possesses more modal uses than hao3 does in Standard Mandarin.

As an adjective, the basic meaning of hɒ3 is ‘good’. Adjectives in Jidong Shaoxing function like intransitive verbs in a way, a common feature for East and Southeast Asian languages. No copula is needed when forming an adjectival predicate, and some adjectives can bear aspectual marking as intransitives do. The two features that distinguish adjectives from intransitive verbs are that (i) adjectives can modify nouns directly and (ii) adverbs can be derived from them. Examples (10) and (11) illustrate the attributive and the predicative uses of hɒ3 ‘good’, respectively. Example (12) shows its derivational use as an adverb, achieved via reduplication and the use of the adverbializer tɕjɒ⁵.

The meaning ‘good’ can imply the meaning ‘suitable’. In (13), hɒ3 denotes ‘suitable’ or ‘better’.

In (14), marked by the currently relevant state marker dzᴇ, hɒ3 denotes ‘ready, done’. hɒ3 in (15) serves as a resultative complement turning the verb tɕʰiə⁷ ‘eat’ into a telic verb phrase expressing a completed action.

| (10) | 破剪刀覅用哉,用个把好剪刀。 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| pʰa⁵ | tɕjᴇ̃3tɒ¹ | fjɒ3 | ɦjoŋ⁶ | dzᴇ, | ɦjoŋ⁶ | ɡə⁸ | po3 | hɒ3 | tɕjᴇ̃3tɒ¹. | ||||||||||||||

| broken | scissor | neg.imp | use | crs | use | s_prox | clf | good | scissor | ||||||||||||||

| ‘Don’t use the broken scissors. Use this good pair.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (11) | □个香榧是好{个□}。 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ŋa⁴ | ɡə⁸ | ɕiaŋ¹fi3 | zᴇ⁴ | hɒ3 | ɡo⁸. | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1pl | poss | Torreya | indeed | good | aff.prt | ||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Our Torreya nuts are indeed good.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (12) | 米好好□来□,侬弄渠作啥? | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| mi⁴ | hɒ3hɒ3 | tɕjɒ⁵ | lᴇ2doŋ, | noŋ⁴ | loŋ⁶ | ɦi⁴ | tsə⁵ | so⁵? | |||||||||||||||

| rice | well | adv | be.at | 2sg | do | 3sg | do | what | |||||||||||||||

| ‘The rice was fine there. How come you messed it up?’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (13) | 渠脸盘大,还是留长头发好。 | |||||||

| ɦi⁴ | ljᴇ̃⁴bə̃2 | do⁶, | ɦwæ2zə⁸ | ljə2 | dzaŋ2 | də2fa⁷ | hɒ3. | |

| 3sg | face | big | still | keep | long | hair | good | |

| ‘She has a big face and long hair suits her.’ | ||||||||

| (14) | 饭好哉。 | ||||

| væ⁶ | hɒ3 | dzᴇ. | |||

| meal | good | crs | |||

| ‘The meal is ready.’ | |||||

| (15) | 饭吃好哉。 | ||||

| væ⁶ | tɕʰjə⁷-hɒ3 | dzᴇ. | |||

| meal | eat-good | crs | |||

| ‘(I) finished (my) meal.’ | |||||

As an auxiliary, hɒ3 takes verbal or clausal complements and can denote ‘fit to, be easy to, can, may, should’. hɒ3 in (16) denotes ‘be easy to’, while (17) is ambiguous and can be interpreted as either ‘fit to’ or as ‘can’. See Section 5 for more examples of the modal uses of hɒ3.

In terms of syntactic position, the auxiliary hɒ3 might sometimes be considered as an adverb. This is especially true in an example like (16) where the meaning ‘be easy to’ could be interpreted as ‘easily’ modifying the verb tso⁵ ‘do’. However, auxiliaries and adverbs are characterized by different syntactic behaviors. As mentioned in Section 3.3, when transforming a declarative sentence with an auxiliary into a polar question, the strategy V (NEG) V is applied to the auxiliary instead of to the main verb, as in (18).

Compare (19) with (16) and (18). The adverb ŋᴇ2 ‘very’ in (19a) occupies the same preverbal position as hɒ3 does in (16). To transform (19a) into a polar question, one must apply the strategy V (NEG) V to the predicative adjective næ2 ‘difficult’, as in (19b). Yet, this strategy can never be used with an adverb. The form ŋᴇ2 (və⁸) ŋᴇ2 ‘lit: very not very’ in (19c) is ungrammatical.

| (16) | 个道题□坐好做□。 | |||||||||||||||

| ɡə⁸ | dɒ⁴ | di2 | mə⁸ | zo⁴ | hɒ3 | tso⁵ | jə⁸. | |||||||||

| s_prox | clf | question | top | sit/extremely | good | do | prt | |||||||||

| ‘This problem is extremely easy to solve.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (17) | 雄花粉埲拢过个半个月好打药水□。 | |||||||||||||||

| ɦjoŋ2hwo1fɘŋ1 | boŋ⁴-loŋ⁴ | ku⁵ | ɡə⁸ | pə̃⁵ | ɡə⁸ | ɦjo⁸ | hɒ3 | |||||||||

| male.flower.pollen | shake-gather | pass | clf | half | clf | month | good | |||||||||

| taŋ3 | ɦja⁸sɿ3 | ɦa. | ||||||||||||||

| beat | pesticide | prt | ||||||||||||||

| ‘A half month after (female Torreya trees) are pollinated manually (with) male pollen, i. it’s the right time for spraying pesticide.’ ii. one can spray pesticide.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (18) | 个道题好(不)好做□? | |||||||

| ɡə⁸ | dɒ⁴ | di2 | hɒ3 | (və⁸) | hɒ3 | tso⁵ | ɦa? | |

| s_prox | clf | question | good | neg | good | do | prt | |

| ‘Is this problem easy to solve?’ (Elicitation) | ||||||||

| (19) | a. | 个道题呆难□。 | |||||||

| ɡə⁸ | dɒ⁴ | di2 | ŋᴇ2 | næ2 | da. | ||||

| s_prox | clf | question | very | difficult | prt | ||||

| ‘This problem is very difficult.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||

| b. | 个道题难(不)难□? | ||||||||

| ɡə⁸ | dɒ⁴ | di2 | næ2 | (və⁸) | næ2 | ɦa? | |||

| s_prox | clf | question | difficult | neg | difficult | prt | |||

| ‘Is this problem difficult?’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||

| c. | *个道题呆(不)呆难□? | ||||||||

| *ɡə⁸ | dɒ⁴ | di2 | ŋᴇ2 | (və⁸) | ŋᴇ2 | næ2 | ɦa? | ||

| s_prox | clf | question | very | neg | very | difficult | prt | ||

| Attempted: ‘Is this problem very difficult?’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||

Beyond its uses as an auxiliary, hɒ3 also has more grammaticalized uses. Namely, hɒ3 is used as a complementizer to introduce a purposive clause equivalent to the English counterpart ‘so as to’. This function may be closely related to the auxiliary use of hɒ3. In the example below, the first clause ‘take away the quilt’ is uttered in a context in which this action will allow the speaker to put a sheet on the bed. The two clauses are linked by hɒ3.

| (20) | 棉被驮还,好让我铺床单方便些。 | ||||||||

| mjᴇ̃2bi⁴ | do2-ɦwæ2, | hɒ3 | ȵjaŋ⁶ | ŋo⁴ | pʰu1 | dzɒŋ2tæ1 | fɒŋ1bjᴇ̃⁶ | sə⁷. | |

| quilt | take-away | good | let | 1sg | lay | sheet | convenient | a.bit | |

| ‘Take away the quilt so as to let me easily put the sheet on.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||

Finally, like Standard Mandarin, hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing can serve as an adverb meaning ‘quite’, i.e., a degree intensifier. This use of hɒ3 is quite limited. The most common case is that hɒ3 modifies the adjective ljaŋ⁴ ‘several’, as in the following example.

| (21) | 头歇儿车路里有好两个人轧死哉□。 | ||||||||

| də⁴ɕjᴇ̃ | tɕʰjo1lu⁶ | li⁴ | ɦjə⁴ | hɒ3 | ljaŋ⁴ | ɡə⁸ | ȵiŋ2 | za⁸-sa⁷ | |

| just.now | road | inside | there.be | good | several | clf | person | crush-die | |

| dzᴇ | mə⁸. | ||||||||

| crs | prt | ||||||||

| ‘There were easily several people that were crushed to death on the road.’ | |||||||||

As can be observed from the examples given above, the modal uses of hɒ3 ‘good’ account for a number of its auxiliary uses. The nuances of its modal meanings will be elaborated in the next section.

5. Modal Uses of hɒ3

Like English can and may or Standard Mandarin neng2 ‘can’ and ke3yi3 ‘may’, the modal meaning of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing is largely dependent on context. This section presents the different types of modality that hɒ3 can express. In a nutshell, hɒ3 can denote circumstantial and physical possibility, permission, weak obligation, and epistemic possibility, but cannot denote mental ability or learned skills.

5.1. Circumstantial Possibility

Circumstantial possibility is the most common modal use of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing and denotes that an action is enabled under certain conditions external to the participant. This use can be easily observed in narratives involving production or treatment processes. Example (22) is one such case. This example concerns how to process Torreya nuts. The procedure of cleaning, expressed with the modal hɒ3 in (22i), can only be carried out after the peels of the Torreya nuts completely rot off, i.e., the peel’s rotting off is the enabling condition for cleaning. Cleaning is, in turn, the enabling condition for the drying process (22ii), which is also realized with the modal hɒ3. Both hɒ3 in (22) denote circumstantial possibility and can be interpreted as ‘can’. Note that ɦwᴇ⁶ in (22), used along with hɒ3, is an adverbial use denoting ‘only then’ and corresponding to the adverb cai2 才 ‘only then’ in Standard Mandarin. This adverbial use of ɦwᴇ⁶ differs from its auxiliary use in (24). See also (29) for another instance of the adverbial use.

We have mentioned above that hɒ3 cannot be used to express mental or learned ability. Thus, the clause (23ii) ‘I can speak French’ does not express the ability of speaking French but denotes that it is possible to speak French under circumstances in which speaking English is unnecessary. To express mental ability or learned skills, one must use the modal verb ɦwᴇ⁶ ‘can’, as in Standard Mandarin. See examples (24) and (8).

In (25), a circumstantial condition is not overtly mentioned, but the sentence implies that there are several ways to get to University City. Taking Line 9 is one possible option.

Example (26) is a topic–comment construction. The sentence-initial noun ka⁷ŋ2 pᴇ⁵ ‘turtle shell’ is not the agent of the VP hɒ3 tso⁵ ɦja⁸ ‘can make medicine’ but the material. Therefore, even though the possibility expressed in (26) is related to the intrinsic property of turtle shells, we still consider this case to be one of circumstantial possibility, as it is the medicinal value of turtle shells that allows them to be made into medicine.

Interestingly, the have-construction, [ɦjə⁴HAVE + NPi + hɒ3GOOD + VP + ∅i], is often used to express possibility.2 In this construction, the VP should be a transitive verb with an absent object. The absent object is co-referential with the NP following the verb ɦjə⁴ ‘have’. See also (30a-ii) and (38) for the same construction denoting permission and dynamic possibility, respectively. The example below is semantically analogous to example (26). The quantity of raw rice determines how much steamed rice one can have.

It should be noted that hɒ3 demonstrates asymmetrical semantic extension in Jidong Shaoxing. The negated hɒ3 does not denote impossibility or prohibition but denotes ‘not suitable’ (see (31)–(33) and further discussion in Section 6). Rather, the opposite of a modal proposition formed by hɒ3 has to be expressed by a negated potential construction [V-NEG-COMP] in which lᴇ2 ‘come’ is the most frequent lexeme occupying the complement position, as mentioned in Section 3.3. Compare the two clauses in (28). Both (28a) and (28b) can be produced after the clause ‘the shop is contaminated with the coronavirus’, with (28a) as a clause of contrast and (28b) as a clause of consequence. The impossibility of using the shared bicycles in (28b) cannot be realized by simply negating the modal hɒ3, but must be expressed by the negated potential construction dʑi2-və⁸-lᴇ2 ‘cannot ride’.

| (22) | 烂□过十日会好戽,戽过会好晒。 | ||||||||

| (i) | læ⁶ | doŋ | ku⁵ | zə⁸ | ȵjə⁸ | ɦwᴇ⁶ | hɒ3 | ɸu⁵, | |

| rot | dur | pass | ten | day | only.then | good | wash | ||

| (ii) | ɸu⁵-ku⁵ | ɦwᴇ⁶ | hɒ3 | sa⁵. | |||||

| wash-pass | only.then | good | dry.in.the.sun | ||||||

| ‘(Let the peels of the Torreya nuts) rot for ten days and only then (you) can wash (the Torreya nuts). Only after washing (them), can (you) dry them in the sun.’ | |||||||||

| (23) | □听不懂英语有啥要紧□,我好话法语个□。 | ||||||||||||

| (i) | ɦja⁴ | tʰiŋ⁵-və⁸-toŋ3 | ʔiŋ1ȵy⁴ | ɦjə⁴ | so⁵ | ʔjɒ⁵tɕiŋ3 | nə⁸, | ||||||

| 3pl | listen-neg-understand | English | have | what | importance | prt | |||||||

| (ii) | ŋo⁴ | hɒ3 | ɦwo⁶ | fa⁷ȵy⁴ | ɡə⁸ | jæ. | |||||||

| 1sg | good | speak | French | aff | prt | ||||||||

| ‘It doesn’t matter if they can’t understand English. I can speak French.’ | |||||||||||||

| (24) | 我会话法语个□。 | ||||||||||||

| ŋo⁴ | ɦwᴇ⁶ | ɦwo⁶ | fa⁷ȵy⁴ | ɡə⁸ | jæ. | ||||||||

| 1sg | can | speak | French | aff | prt | ||||||||

| ‘I can speak French.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||||||

| (25) | 侬□大学城好坐9号线{个□}。 | ||||||

| noŋ⁴ | ta⁵ | da⁶ɦjo⁸dzɘŋ2 | hɒ3 | zo⁴ | tɕjə3ɦɒ⁶ɕjᴇ̃⁵ | ɡo. | |

| 2sg | all | university.city | good | sit | number.nine.line | aff.prt | |

| ‘You can take Line 9 to go to University City.’ | |||||||

| (26) | 甲鱼背好做药个□。 | ||||||

| ka⁷ŋ2 | pᴇ⁵ | hɒ3 | tso⁵ | ɦja⁸ | ɡə⁸ | jæ. | |

| soft.shell.turtle | back | good | do | medicine | aff | prt | |

| ‘Turtle shells can be made into (Chinese traditional) medicine.’ | |||||||

| (27) | 三升米有五碗好烧。 | |||||||

| sæ1 | sɘŋ1 | mi⁴ | ɦjə⁴ | ŋ⁴ | ʔwə̃3 | hɒ3 | sɒ1. | |

| three | cup | rice | have | five | bowl | good | cook | |

| ‘Three cups of raw rice can be made into five bowls of steamed rice.’ | ||||||||

| (28) | 后头爿店个个毛病惹牢□, | ||||||||||

| ɦə⁴də2 | bæ⁶ | tjᴇ̃⁵ | ɡə⁸ | ɡə⁸ | mɒ2biŋ⁶ | ȵja⁴-lɒ2 | lə⁸, | ||||

| back | clf | shop | s_prox | clf | illness | attract-tight | prt | ||||

| a. | 前头个共享单车话道照样好用□。 | ||||||||||

| ʑjᴇ̃2də2 | ɡə⁸ | goŋ⁶ɕjaŋ3 | tæ1tɕʰjo1 | ɦwo⁶dɒ⁴ | tsɒ⁵ɦjaŋ⁶ | hɒ3 | ɦjoŋ⁶ | la. | |||

| front | mod | shared | bicycle | unexpectedly | as.usual | good | use | prt | |||

| ‘Even though the shop is contaminated with the coronavirus, the shared bicycles in front of it are still available for use.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | 前头个共享单车也骑不来哉。 | ||||||||||

| ʑjᴇ̃2də2 | ɡə⁸ | goŋ⁶ɕjaŋ3 | tæ1tɕʰjo1 | ɦa⁴ | dʑi2-və⁸-lᴇ2 | dzᴇ. | |||||

| front | mod | shared | bicycle | also | ride-neg-come | crs | |||||

| ‘The shop is contaminated with the coronavirus, (so) the shared bicycles in front of (the shop) aren’t available for use any more.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||||

5.2. Permission and Weak Obligation

In Jidong Shaoxing, hɒ3 can express both permission and weak obligation, both of which belong to deontic modality. Semantically, these modal types correspond to ‘may’ and ‘should, ought to’, respectively. Like circumstantial possibility (), the enabling conditions of these two modality types are also participant-external except that permission and weak obligation are determined by speakers or social or ethical norms.

5.2.1. Permission

Example (29) demonstrates hɒ3 used to express legal marriage ages in China. (30q) is a polar question asking for one’s permission in which the reduplicated form hɒ3 hɒ3 is the contracted form of V (NEG) V when forming a polar question (see also (8) and (19)). A positive answer to (30q) is given in (30a-i). In (30a-ii), the possessive construction is used to denote permission. tɕjə⁵ is the contraction of the adverb tsə⁷ ‘only’ and the possessive verb ɦjə⁴ ‘have’.3

As mentioned in Section 3.3 and Section 5.1, the negated hɒ3 may not be used to denote ‘cannot, may not, should not’. To express prohibition, one must adopt the negated potential construction [V-NEG-lᴇ2] ‘cannot, may not’. Compare (31) with (29).

Similarly, to deny the request in (30q), the negated potential construction tɕʰjə⁷-və⁸-lᴇ2 ‘may not eat’ is used, as shown in (32).

| (29) | 男个要廿二岁,女个廿岁会好结婚□。 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| nə̃2 | ɡə⁸ | ʔjɒ⁵ | ȵjæ⁶ȵi⁶ | sᴇ⁵, | ȵy⁴ | ɡə⁸ | ȵjæ⁶ | sᴇ⁵ | |||||||||||||||

| male | nmlz | need | twenty-two | year | female | nmlz | twenty | year | |||||||||||||||

| ɦwᴇ⁶ | hɒ3 | tɕjə⁷hwɘŋ1 | lᴇ. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| only.then | good | marry | prt | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ‘Men can only get married when they attain 22 years of age and the legal age of marriage for women is 20.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (30) | q- | 个颗糖我好好吃? | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ɡə⁸ | kʰo1 | dɒŋ2 | ŋo⁴ | hɒ3 | hɒ3 | tɕʰjə⁷? | |||||||||||||||||

| s_prox | clf | candy | 1sg | good | good | eat | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘May I eat this candy?’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| a- | 吃是好吃,介{只有}一颗好吃。 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| (i) | tɕʰjə⁷ | zə⁸ | hɒ3 | tɕʰjə⁷, | (ii) | ka⁷ | tɕjə⁵ | ʔjə⁷ | kʰo1 | hɒ3 | tɕʰjə⁷. | ||||||||||||

| eat | cop | good | eat | but | only.have | one | clf | good | eat | ||||||||||||||

| ‘Yes, definitely you may, but you can only eat one.’ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| (31) | 男个年龄不到廿二岁,婚结不来□。 | |||||||

| nə̃2 | ɡə⁸ | ȵjᴇ̃2liŋ2 | fə⁷ | tɒ⁵ | ȵjæ⁶ȵi⁶ | sᴇ⁵, | hwɘŋ1 | |

| male | nmlz | age | neg | attain | twenty-two | year | marriage | |

| tɕjə⁷-və⁸-lᴇ2 | lᴇ. | |||||||

| marry-neg-come | prt | |||||||

| ‘Men cannot get married (legally), if they haven’t attained 22 years of age.’ (Elicitation) | ||||||||

| (32) | a- | 吃不来{个□},看牙齿烂光。 | ||||

| tɕʰjə⁷-və⁸-lᴇ2 | ɡo⁸, | kʰə̃⁵ | ŋo2tsʰɿ3 | læ⁶-kwɒŋ1. | ||

| eat-neg-come | aff.prt | look | tooth | rot-finish | ||

| ‘No, you may not. Beware of rotten teeth.’ | ||||||

The semantic asymmetry between hɒ3 ‘can’ and fə⁸ hɒ3 ‘not good, not suitable’ makes Jidong Shaoxing stand out among other Wu dialects in which not good is observed to denote ‘may not, cannot’, such as Shanghainese (; ) and Xianju Wu 仙居话.4 Compare the two sentences from Jidong Shaoxing and Xianju given in (33). To express ‘one may not smoke indoors’, the negated potential construction tɕʰjə⁷-və⁸-lᴇ2 ‘cannot eat’ is used in Jidong Shaoxing, while fao⁴2 ‘cannot’, which is the fusion of the negator fəʔ2 and hao32⁴ ‘can < good’, is used in Xianju.

| (33) | Jidong Shaoxing | ||||

| a. | 里头香烟吃不来{个□}。 | ||||

| li⁴də2 | ɕjaŋ1ʔjᴇ̃1 | tɕʰjə⁷-və⁸-lᴇ2 | ɡo. | ||

| inside | cigarette | eat-neg-come | aff.prt | ||

| ‘(One) may not smoke indoors.’ (Elicitation) | |||||

| Xianju Wu 仙居吴语 | |||||

| b. | 间里{不好}吃香烟。 | ||||

| ka33⁴li32⁴ | fao⁴2 | tɕʰoʔ⁵ | ɕia⁵⁵ie⁴2. | ||

| room.inside | neg.good | eat | cigarette | ||

| ‘(One) may not smoke indoors.’ (Elicitation) (Pan Xueyuqing pers. comm.) | |||||

5.2.2. Weak Obligation

We have seen permission granted (either by a social norm or a speaker) with the modal hɒ3 ‘good’ in previous examples. When expressing weak obligation with hɒ3, it is often the case that a speaker offers his or her advice or imposes his or her desire in a delicate way on the participant. Example (34) is a case of giving advice or a command. In this sentence, the topicalized object ‘clutch’ precedes the verb and follows the subject.

By way of contrast, the following two examples are more optative. However, if example (35) is a combination of the speaker’s advice and wish, the case of (36) certainly only involves the speaker’s wish, for a meteorological phenomenon is not an intervenable event.

| (34) | 侬只离合器好抬起来哉,再闹落去部车都要拨侬闹破哉。 | |||||||||

| noŋ⁴ | tsə⁷ | li2ɦə⁸tɕʰi⁵ | hɒ3 | dᴇ2-tɕʰi3lᴇ2 | dzᴇ, | tsᴇ⁵ | nɒ⁶-lə⁸tɕʰi⁵ | bu⁶ | tɕʰjo1 | |

| 2sg | clf | clutch | good | lift-rise.come | crs | still | do-fall.down | clf | car | |

| tu1 | ʔjɒ⁵ | pə⁷ | noŋ⁴ | nɒ⁶-pʰa⁵ | dzᴇ. | |||||

| all | prosp | pass | 2sg | do-break | crs | |||||

| ‘You should let go of the clutch. Otherwise, you’ll wreck the car.’ | ||||||||||

| (35) | 侬头发好剪剪哉。 | |||||||||||||||

| noŋ⁴ | də2fa⁷ | hɒ3 | tɕjᴇ̃3tɕjᴇ̃3 | dzᴇ. | ||||||||||||

| 2sg | hair | good | cut.dlm | crs | ||||||||||||

| ‘You should get a haircut.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (36) | 雨落□介许多日数哉,好停停哉□。 | |||||||||||||||

| ɦy⁴ | lo⁸ | lə⁸ | ka⁵ | ɕy3to1 | ȵjə⁸su⁵ | dzᴇ, | hɒ3 | diŋ2diŋ2 | dzᴇ | jə⁸. | ||||||

| rain | fall | prf | so | many | day | crs | good | stop.dlm | crs | prt | ||||||

| ‘It has been raining for so many days. It should stop.’ | ||||||||||||||||

5.3. Participant-Internal Possibility

Participant-internal possibilities expressed by hɒ3 are basically restricted to dynamic abilities or possibilities. We reiterate that the domain of mental ability or learned skills excludes the use of hɒ3. Unlike the uses of hɒ3 illustrated in Section 5.1 and Section 5.2, the possibilities expressed by hɒ3 in (37) and (38) are not enabled by external or circumstantial factors but are determined by participants’ inherent physical strength.

| (37) | 我一只肩胛两百斤担好挑。 | ||||||||||||||||

| ŋo⁴ | ʔjə⁷ | tsə⁷ | tɕjᴇ̃1ka⁷ | ljaŋ⁴pa⁷ | tɕiŋ1 | tæ⁵ | hɒ3 | tʰjɒ1. | |||||||||

| 1sg | one | clf | shoulder | two.hundred | a.half.kilo | load | good | carry | |||||||||

| ‘I can carry a load of one hundred kilos on one shoulder.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| (38) | 侬小辰光脚筋骨好□,我跟□爷爷柴山里走一埭,侬好走两三埭□。 | ||||||||||||||||

| noŋ⁴ | ɕjɒ3 | zɘŋ2kwɒŋ1 | tɕja⁷tɕiŋ1kwə⁷ | hɒ3 | lᴇ, | ŋo⁴ | kiŋ1 | na⁴ | |||||||||

| 2sg | small | moment | leg.muscles.bones | good | prt | 1sg | and | 2sg.poss.kin | |||||||||

| ɦja2ɦja2 | za2 | sæ1 | li⁴ | tsə3 | ʔjə⁷ | da⁶, | noŋ⁴ | ||||||||||

| grandfather | firewood | hill | inside | walk | one | vclf | 2sg | ||||||||||

| hɒ3 | tsə3 | ljaŋ⁴ | sæ1 | da⁶ | lᴇ. | ||||||||||||

| good | walk | two | three | vclf | prt | ||||||||||||

| ‘You were of good leg strength when you were little. Within the time me and your grandfather managed to arrive at the hill (to fetch some firewood), you could make several trips.’ | |||||||||||||||||

Example (39) shows the have-construction used to express physical ability.

Nevertheless, we do observe some marginal examples beyond the domain of physical ability. In (40), the participants ‘leaves’ are also the subject and are inanimate and cannot initiate an action, but ‘floating on the surface (of the water)’ is relevant to their inherent physical property of being light.

| (39) | □卯做苦力,介几十斤石头,背牢有好两十里路好走□。 | ||||||||

| ɦæ2mɒ⁶ | tso⁵ | kʰu3ljə⁸, | ka⁵ | tɕi3 | zə⁸ | tɕiŋ1 | za⁸də2 | pᴇ⁵-lɒ2 | |

| before | do | labor | so | several | ten | a.half.kilo | stone | carry-tight | |

| ɦjə⁴ | hɒ3 | ljaŋ⁴ | zə⁸ | li⁴ | lu⁶ | hɒ3 | tsə3 | lᴇ. | |

| have | good | several | ten | a.half.kilometer | road | good | walk | prt | |

| ‘I could walk quite a dozen kilometers with a dozen kilos of stones carried on my back, when I was doing hard labor long before.’ | |||||||||

| (40) | 树叶爿轻飘飘{个□},水高顶好浮个□。 | ||||||||

| zɿ⁶ɦjə⁸bæ⁶ | tɕʰiŋ1-pʰjɒ1pʰjɒ1 | ɡo⁸, | sɿ3 | kɒ1tɘŋ3 | hɒ3 | və2 | ɡə⁸ | la. | |

| leaf | light-viv | aff.prt | water | surface | good | float | aff | prt | |

| ‘Leaves are very light and can float on the surface of the water.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||

Note that () claims that hɒ3 is only used in the modal have-construction to express dynamic possibility in Keqiao Shaoxing.

5.4. Epistemic Possibility

Finally, hɒ3 can also be used to express presumption in Jidong Shaoxing. Presumption also falls under epistemic possibility since a speaker often makes a presumption based on previous knowledge. As shown in (41), a proposition is made with the knowledge that cherry blossoms usually bloom in late March and early April.

The proposition below in (42) can be produced in several contexts, such as a context based on daily routine or one’s experiential estimation. Certainly, this sentence possesses a deontic interpretation in certain contexts, such as if the speaker were giving an instruction or order.

Example (43) is based on known information which is mentioned in the if-clause. The NP ɦjə⁴ (sə⁷) su⁵ ‘have (some) numbers’ in this sentence is metaphorically used to denote ‘be sure about something’ or ‘know something exactly’.

In sum, the lexeme hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing has lost its lexical meaning of ‘good’ when used as a modal auxiliary, as can be seen in all the examples illustrated in Section 5. It can denote circumstantial possibility, deontic modality (permission and weak obligation), dynamic physical ability, and epistemic possibility. Like many modal auxiliaries across languages of the world (see for the entries ‘C-possibility’, ‘D-possibility’, ‘D-necessity’, Pi-possibility, and ‘E-possibility’), hɒ3 can be interpreted as ‘can’, ‘may’, or ‘should’ in different contexts. Despite its polysemy as a modal auxiliary, we do observe cases where hɒ3 cannot be used even within the modality types hɒ3 denotes. The restrictions on hɒ3 might be related to its source meaning ‘fit to’ and its circumstantial uses, which will be elaborated in the next section.

| (41) | 辰山植物园个樱花好开□哉。 | |||||||

| dzɘŋ2sæ1 | dzə⁸və⁸ɦjə̃2 | ɡə⁸ | ʔiŋ1hwo1 | hɒ3 | kʰᴇ1 | doŋ | dzᴇ. | |

| ChenshanPLACENAME | botanical.garden | mod | cherry.blossom | good | bloom | prf | crs | |

| ‘The cherry blossoms in the Botanical Garden of Chenshan may have bloomed.’ | ||||||||

| (42) | 车好来□哉。 | ||||

| tɕʰjo1 | hɒ3 | lᴇ2 | doŋ | dzᴇ. | |

| car | good | come | prf | crs | |

| ‘The car/bus should be on the way.’ | |||||

| (43) | 是话下卯再碰着介种事体,□个对付侬也好有些数哉{个□}。 | ||||||||

| zᴇ⁴ɦwo⁶ | ɦo⁴mɒ⁶ | tsᴇ⁵ | baŋ⁶-dza⁸ | ka⁵ | tsoŋ3 | zɿ⁶tʰi3, | na⁸ɡə⁸ | tᴇ⁵fu⁵ | |

| if | next.time | again | run.into-attach | so | kind | thing | how | deal | |

| noŋ⁴ | ɦa⁴ | hɒ3 | ɦjə⁴ | sə⁷ | su⁵ | dzᴇ | ɡo⁸. | ||

| 2sg | also | good | have | some | number | crs | aff.prt | ||

| ‘Next time you encounter a similar situation, you may know how to handle it.’ | |||||||||

6. Reconstruction

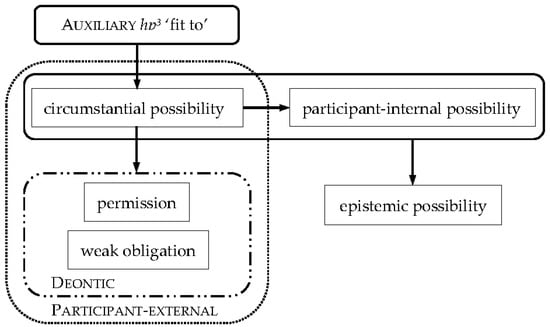

We have shown in Section 4 the polysemy of the lexeme hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing, but from which meaning is the modal hɒ3 derived? We propose that the modal meaning of hɒ3 is basically derived from the meaning ‘fit to’ but not from the primary meaning ‘good’. To be exact, the hɒ3 of ‘fit to’ has extended to denote first circumstantial and then deontic possibility and necessity. It is from circumstantial possibility that hɒ3 has extended to express participant-internal possibility. Finally, hɒ3 has extended to denote epistemic possibility. For this, see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Extension pathways of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing.

We propose that the extension of hɒ3 from a non-modal auxiliary to a modal auxiliary is motivated by contextual reanalysis and is a result of grammaticalization. Even though the ‘fit’ hɒ3 and the modal hɒ3 are both auxiliaries, the modal hɒ3 is more desemanticized than the ‘fit’ hɒ3, with desemanticization being one of the four parameters for identifying grammaticalization ().

The following subsections will explain the semantic extension of hɒ3 stage by stage.

6.1. ‘Fit to’ > Circumstantial Possibility > Deontic Modality

We identify the auxiliary use of hɒ3 ‘fit to’ as the source meaning of its modal uses, since the auxiliary uses of hɒ3 provide the primary syntactic context for its further extension, or grammaticalization, to modal auxiliaries, that is, [AUX VP]. Note that the meaning ‘fit to’ derives from the meaning ‘good’, as ‘good’ can imply the meaning ‘suitable, fit to’. See example (13).

Ambiguity between the meaning ‘fit to’ and the modal meaning ‘can, may, should’ can be easily observed in Jidong Shaoxing. This kind of ambiguous context is labelled “bridging context”5 by () and “critical context” by (). We adopt ’s () context-induced grammaticalization model to illustrate the process from ‘fit to’ to ‘can, may, should’ for hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing. Ambiguous contexts play an important role in the process of semantic change and grammaticalization “giving rise to an inference in favor of a new meaning” (). They are the environments where the mechanism of reanalysis takes effect. That is to say, a bridging context of ‘fit to’-‘can’ provides a breeding environment where the modal meaning of hɒ3 can be inferred. A complete process for the emergence of a new meaning is proposed to comprise four stages: (i) initial stage, (ii) bridging context, (iii) switch context, and (iv) conventionalization ().

In the initial stage, ‘fit to’ is the only reading of hɒ3. Although in most cases hɒ3 ‘fit to’ can also be interpreted as ‘can, may, should’, especially in positive sentences, the exclusive meaning of ‘fit to’ is well preserved in the negated form of hɒ3, i.e., [NEG hɒ3 VP]. As illustrated in (44), the VP fə⁷ da hɒ3 tsʰə̃1 can only be interpreted as ‘not suitable to wear’. While a Mandarin native speaker or a speaker of other Wu dialects would probably not be convinced by our claim that the negated hɒ3 cannot be interpreted as ‘cannot, may not’, as we have mentioned above, the negated hɒ3 has not yet developed any modal meaning in Jidong Shaoxing. See (31)–(33) above. The meaning of ‘cannot, may not, should not’ can only be expressed by a negated potential construction.

| Initial Stage | |||||||||

| (44) | 是话下卯十二月里哉,侬个双鞋介薄横不大好穿哉。 | ||||||||

| zᴇ⁴ɦwo⁶ | ɦo⁴mɒ⁶ | zə⁸ȵi⁶ɦjo⁸ | li⁴ | dzᴇ, | noŋ⁴ | ɡə⁸ | ɕjɒŋ1 | ||

| if | later | December | inside | crs | 2sg | poss | clf | ||

| ɦa2 | ka⁵ | bo⁸ | ʔwaŋ3 | fə⁷ | da | hɒ3 | tsʰə̃1 | dzᴇ. | |

| shoe | so | thin | after.all | neg | very | good | wear | crs | |

| ‘Your shoes are so thin and by December they won’t be suitable to wear after all.’ | |||||||||

The asymmetrical semantic extension of hɒ3 ‘can’ and fə⁷ hɒ3 ‘not suitable’ in Jidong Shaoxing helps us to locate the lexical source of the modal hɒ3. The asymmetry can be explained by the principle of persistence (), which refers to lexical traces being retained in a grammaticalized form in the process of grammaticalization.

In a bridging context, hɒ3 is ambiguous and can be interpreted either as ‘fit to’ or as ‘can’. It is in such contexts that the lexeme hɒ3 ‘fit to’ is reanalyzed as ‘can’. This reanalysis can be seen in example (45), where the clause ‘he’s not here’ provides a suitable condition for the speaker to say something, and for hɒ3 to be reanalyzed as ‘can’.

| Bridging Context | ||||||||

| (45) | 渠人{无有}□,我有两句说话好话哉。 | |||||||

| ɦi⁴ | ȵiŋ2 | ʔȵjə3 | mə⁸, | ŋo⁴ | ɦjə⁴ | liaŋ⁴ | tɕy⁵ | |

| 3sg | person | neg.have | prt | 1sg | have | several | clf | |

| ɕjo⁷ɦwo⁶ | hɒ3 | ɦwo⁶ | dzᴇ⁶. | |||||

| speech | good | say | crs | |||||

| ‘Since he’s not here, I have something that is suitable to say.’ ‘Since he’s not here, I have something that can be uttered.’ | ||||||||

In a switch context, the new modal meaning of hɒ3 is the only interpretation. However, as pointed out by (), in this stage the target meaning still needs to be supported by a context. In (46), in the context that ʔjɒ⁵ tso⁵ ɡə⁸ tu1 tso⁵-hɒ3 dzᴇ⁶ ‘(I) finish all that should be done’, the hɒ3 in the following clause liŋ⁶ŋa⁶ zɿ⁶tʰi3 ʔȵjə3 so⁵ hɒ3 tso⁵ ɡo⁸ can only be interpreted as a modal verb and the clause denotes ‘there’s nothing else that (I) can do’. Without this context, the clause liŋ⁶ŋa⁶ zɿ⁶tʰi3 ʔȵjə3 so⁵ hɒ3 tso⁵ ɡo⁸ can also be interpreted as ‘there’s nothing else that fits (me) to do’. Undoubtedly, it is the specific context that helps to rule out the source meaning ‘fit to’.

| Switch Context | ||||||||

| (46) | 要做个都做好哉,另外事体{无有}啥好做{个□}。 | |||||||

| ʔjɒ⁵ | tso⁵ | ɡə⁸ | tu1 | tso⁵-hɒ3 | dzᴇ⁶, | liŋ⁶ŋa⁶ | zɿ⁶tʰi3 | |

| need | do | nmlz | all | do-good | crs | other | thing | |

| ʔȵjə3 | so⁵ | hɒ3 | tso⁵ | ɡo⁸. | ||||

| neg.have | what | good | do | nmlz.prt | ||||

| ‘(I) finish all that should be done, there’s nothing else that (I) can do.’ | ||||||||

At the stage of conventionalization, the modal meaning of hɒ3 becomes independent of the source meaning ‘fit to’ which means that its modal meaning does not need to be supported by a specific context. In (47), the ‘can’ meaning of hɒ3 is the only interpretation.

We must admit that, as a modal verb, hɒ3 has attained a certain degree of conventionalization, as demonstrated in (47). However, there are still constraints and restrictions closely related to the source uses of hɒ3 which can be explained by the principles of persistence and layering (). Ambiguity between ‘fit to’ and ‘can’ emerges when hɒ3 denotes circumstantial possibility. In addition to contextual information, the syntactic units and semantic components of a sentence are also important in interpretating the meaning of hɒ3. Compare examples (48) and (49) of circumstantial possibility below. Each component of the sentence adds to its interpretation. In (48), the verb ti3tsa⁵ ‘pay a debt in kind’ implies that the items used to pay a debt are of a certain value, thereby implying that items of a certain value ‘fit to’ and ‘can’ be used to pay a debt. In contrast, (49) is a simple statement that lettuce, a common vegetable, can be served after a simple preparation. The meaning ‘fit to’ is not compatible with this particular sentence.

Unlike in cases of circumstantial possibility, when denoting deontic permission, weak obligation, participant-internal possibility, and epistemic possibility, hɒ3 can hardly be interpreted as ‘fit to’. One more example of permission (deontic possibility) is given below. Interpretating hɒ3 as ‘fit to’ in (50) is impossible. See (55) and (58) for examples of participant-internal possibility and epistemic possibility, respectively.

The ambiguity between ‘fit to’ and circumstantial ‘can’ is the major reason we have proposed in Figure 1 that, within the participant-external modality expressed by hɒ3, it is from circumstantial possibility that hɒ3 extends to express deontic modality. Our hypothesis conforms to general principles of grammaticalization. The fact that hɒ3 exhibits a high frequency of ambiguity when denoting circumstantial possibility suggests the hɒ3 of circumstantial possibility is less desemanticized and thus less grammaticalized. Cross-linguistically, it is also attested that circumstantial possibility can extend to express deontic possibility, such as ‘get to’ in English () and Chinese de2/dei3 得 ‘obtain’ (). See also hao3 ‘good’ in the history of Chinese, as discussed in Section 6.5.

| Conventionalization | |||||||||

| (47) | □头卯好走另外埭路个□。 | ||||||||

| ŋa⁴ | də⁴mɒ⁶ | hɒ3 | tsə3 | liŋ⁶ŋa⁶ | da⁶ | lu⁶ | ɡə⁸ | jæ. | |

| 1pl | just.now | good | walk | other | clf | road | aff | prt | |

| ‘We could take the other road just now.’ | |||||||||

| (48) | 值铜钿个东西好抵债个□。 | |||||||||||||||||

| dzə⁸ | doŋ2djᴇ̃2 | ɡə⁸ | toŋ1ɕi1 | hɒ3 | ti3tsa⁵ | ɡə⁸ | jə⁸. | |||||||||||

| worth | money | rel | thing | good | repay | aff | prt | |||||||||||

| ’Anything of value is suitable for repaying the debt. ‘Anything of value can (be used to) repay my debt.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| (49) | 生菜水里汆一记就好吃哉。 | |||||||||||||||||

| saŋ1tsʰᴇ⁵ | sɿ3 | li⁴ | tsʰə̃1 | ʔjə⁷ | tɕi⁵ | ʑjə⁶ | hɒ3 | tɕʰjə⁷ | dzᴇ. | |||||||||

| lettuce | water | inside | blanch | one | vclf | then | good | eat | crs | |||||||||

| ‘Just blanch in boiling water, and the lettuce can be eaten then.’ | ||||||||||||||||||

| (50) | 小人□个好不懂礼貌□? | ||||||

| ɕjɒ3ȵiŋ2 | na⁸ɡə⁸ | hɒ3 | fə⁷ | toŋ3 | li⁴mɒ⁶ | ȵiŋ? | |

| child | how | good | neg | know | politeness | prt | |

| ‘How could it be that children do not know about being polite?’ | |||||||

Like circumstantial possibility, permission is a kind of possibility determined by external conditions. The example below gives a case that can be understood either as circumstantial possibility or as permission. On the one hand, kids are usually thought to have fewer obligations and more leisure time than adults do. Under such circumstances, kids can have fun and hang out as they wish. On the other hand, (51) can also be read as giving permission, in that kids may play at will since they are free from many social obligations.

The stage of permission is probably an intermediate stage in hɒ3′s extension from circumstantial possibility to weak obligation (see for English must and German müssen) since we do not observe any ambiguous contexts of circumstantial possibility and weak obligation. Yet, ambiguity between permission and weak obligation is readily attested. Example (52) can be interpreted in two ways. If doing chores is the agreed daily routine prior to homework, hɒ3 denotes permission. However, if doing chores is the choice of the participant and there is still homework to do, hɒ3 is interpretable as weak obligation.

In the example below, a father impatiently urges his child to do homework. The permission meaning of the clause hɒ3 tso⁵ tso⁷ȵjə⁸ is ruled out by the context and can only be understood as ‘(you) should do your homework’.

| (51) | □大姑娘好随便搞{个□},□大人随便搞不来个□。 | |||||||

| na⁴ | do⁶ku1ȵjaŋ2 | hɒ3 | dzᴇ2bjᴇ̃⁶ | kɒ3 | ɡo⁸, | ŋa⁴ | do⁶ȵiŋ2 | |

| 2pl | girl | good | at.will | play | aff.prt | 1pl | adult | |

| dzᴇ2bjᴇ̃⁶ | kɒ3-və⁸-lᴇ2 | ɡə⁸ | jæ. | |||||

| at.will | play-neg-come | aff | prt | |||||

| ‘You little girls can/may hang out and have fun as you wish, but as adults we can’t play at will.’ (Elicitation) | ||||||||

| (52) | 是介{无有}事体哉,侬好做作业去哉。 | ||||||

| zᴇ⁴ka⁵ | ʔȵjə3 | zɿ⁶tʰi3 | dzᴇ, | noŋ⁴ | hɒ3 | tso⁵ | |

| apart.from.this | neg.have | thing | crs | 2sg | good | do | |

| tso⁷ȵjə⁸ | tɕʰi⁵ | dzᴇ. | |||||

| homework | go | crs | |||||

| ‘Apart from this, there are no chores. You may/should do your homework.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||

| (53) | 有有搞撑□□?好做作业哉□! | |||||||||

| ɦjə⁴ | ɦjə⁴ | kɒ3-tsʰaŋ⁵ | lᴇ | ɒ? | hɒ3 | tso⁵ | tso⁷ȵjə⁸ | dzᴇ | jə⁸! | |

| have | have | play-enough | prt | prt | good | do | homework | crs | prs | |

| ‘Are you done with (the games)? (You) should do your homework.’ | ||||||||||

6.2. Circumstantial Possibility > Participant-Internal Possibility

Under the framework of context-induced grammaticalization, we propose that it is from circumstantial possibility that participant-internal possibility is derived. As claimed by (), “circumstantial possibility with animate agents usually presupposes ability”. As in (54), the action of crossing the ditch is enabled by two conditions. One is the width of the ditch, and the other is the physical ability of the participant. The former is the enabling circumstantial condition, while the latter is a determining inherent ability.

Example (55) is a have-construction used to express possibility. The possibility of earning money is enabled by the condition that the participant, my father, does woodworking. In fact, the have-construction tsoŋ3 ɦjə⁴ ljaŋ⁴ kʰwᴇ⁵ hɒ3 tsʰɘŋ⁵ can denote circumstantial possibility even if the context is not considered. Namely, there’s always some money that one can earn. Given that it is the same referent who does woodworking and earns money, the meaning of circumstantial possibility can be ruled out. Example (56) offers a case where participant-internal possibility is the only interpretation.

| (54) | □道沟{只有}一些末儿劳什,一记过之好跨过去个□。 | ||||||

| haŋ⁵ | da⁶ | kjə1 | tɕjə⁵ | ʔjə⁷sə⁷ma⁸-ŋ | lɒ2zə⁸, | ʔjə⁷ | |

| dist | clf | ditch | only.have | a.little-dim | thing | one | |

| tɕi⁵-ku⁵tsɿ1 | hɒ3 | kʰo1-ku⁵tɕʰi⁵ | ɡə⁸ | la. | |||

| vclf-dim | good | stride-pass.over | aff | prt | |||

| ‘That ditch is such a little thing. (I) can cross over by taking just one jump.’ | |||||||

| (55) | □老爹做做木匠,总有两块钱好趁。 | ||||||||||||||||

| ŋa⁴ | lɒ⁴tja1 | tso⁵tso⁵ | mə⁸ɦjaŋ⁶, | tsoŋ3 | ɦjə⁴ | ljaŋ⁴ | |||||||||||

| 1sg.poss.kin | dad | do.dlm | carpenter | somehow | have | several | |||||||||||

| kʰwᴇ⁵ | hɒ3 | tsʰɘŋ⁵. | |||||||||||||||

| clf | good | earn | |||||||||||||||

| ‘My father does some woodworking on and off and (he) can somehow make some money (out of it).’ | |||||||||||||||||

| (56) | 我眼睛是不好,介我好听个□。 | ||||||||||||||||

| ŋo⁴ | ŋjæ⁴tɕiŋ1 | zᴇ⁴ | fə⁷ | hɒ3, | ka⁷ | ŋo⁴ | hɒ3 | tʰiŋ⁵ | ɡə⁸ | ja. | |||||||

| 1sg | eye | indeed | neg | good | but | 1sg | good | hear | aff | prt | |||||||

| ‘My eyes aren’t good, but (even so) I can hear.’ | |||||||||||||||||

When denoting participant-internal possibility, there exist restrictions for hɒ3 that may be related to both circumstantial possibility and its lexical meaning.

In Jidong Shaoxing, potential constructions are commonly used to express participant-internal possibility (see also ). In this domain, the distribution of potential constructions and hɒ3 partially overlap. hɒ3 can be replaced by a potential construction in most cases, except for modal have-constructions, which exclusively use hɒ3. For example, the second clause of (56), reproduced below, can also be realized by a potential construction.

When denoting participant-internal possibility, potential constructions are more generalized and neutral, while hɒ3 is most often observed in one of two specific contexts. The first often involves an enabling condition, external or internal, as in (54). In the second, hɒ3 expresses a possible option. This is the case in (56), a sentence produced in the context of a concert. Here, the ability to hear provides an option for enjoying a concert, even though one’s eyesight is not good. These two types of contexts contain traces of hɒ3′s use denoting circumstantial possibility, i.e., possibility enabled by external circumstances. The example below shows a case where hɒ3 cannot be used to express inherent ability. To answer the question ‘Can you hear (me)?’, only the potential construction can be used, as in (58ai). hɒ3 can neither be used to form the question ‘Can you hear (me)?’ nor be used to answer the question, as in (58aii).

| (57) | 介我听得见个□。 | ||||

| ka⁷ | ŋo⁴ | tʰiŋ⁵-tə⁷-ȵjᴇ̃⁶ | ɡə⁸ | ja. | |

| but | 1sg | hear-pot-see | aff | prt | |

| ‘but (even so) I can hear.’ | |||||

| (58) | q- | 侬耳朵好不好□?听不听得见□? | |||||||||||

| noŋ⁴ | ȵi⁴to | hɒ3 | və⁸ | hɒ3 | lᴇ? | tʰiŋ⁵ | və⁸ | tʰiŋ⁵-tə⁷-ȵjᴇ̃⁶ | lᴇ? | ||||

| 2sg | ear | good | neg | good | prt | hear | neg | hear-pot-see | prt | ||||

| ‘Did you get your hearing back? Can you hear (me)?’ | |||||||||||||

| ai- | 听得见{个□}。 | ||||||||||||

| tʰiŋ⁵-tə⁷-ȵjᴇ̃⁶ | ɡo⁸. | ||||||||||||

| hear-pot-see | aff.prt | ||||||||||||

| ‘(Yes, I) can.’ | |||||||||||||

| aii- | *好听{个□}。 | ||||||||||||

| *hɒ3 | tʰiŋ⁵ | ɡo⁸. | |||||||||||

| good | hear | aff.prt | |||||||||||

| Attempted: ‘Yes, I can.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||||||

In addition, we observe that hɒ3 is not compatible with the [V-tə⁷-COMP] potential construction. A pair of contrastive sentences is given in (59) to better illustrate this restriction on the use of hɒ3. The context of (59a) entirely suits hɒ3 in that the possibility of seeing clearly is allowed or enabled by wearing glasses. However, since the possibility of seeing clearly is expressed by the potential construction kʰə̃⁵-tə⁷-ȵjᴇ̃⁶ ‘can see clearly’, using hɒ3 here is ungrammatical. To produce a grammatical sentence with hɒ3 in such a context, the potential construction cannot be used, as in (59b).

This restriction might be related to the source meaning of hɒ3, ‘fit to’. As the meaning ‘fit to’ implies possibility, a possible explanation is that hɒ3 does not co-occur with a potential construction to avoid semantic redundancy. An analogy would be an awkward and redundant English construction, ‘fit to be able to’. This trace persists when hɒ3 is used as a modal auxiliary.6

| (59) | a. | 渠近视,要戴眼镜会(*好)看得见。 | |||||||

| ɦi⁴ | dʑiŋ⁴zɿ⁶, | ʔjɒ⁵ | ta⁵ | ŋjæ⁴tɕiŋ⁵ | ɦwᴇ⁶ | (*hɒ3) | kʰə̃⁵-tə⁷-ȵjᴇ̃⁶. | ||

| 3sg | short-sighted | need | wear | glasses | only.then | good | look-pot-see | ||

| ‘He’s short-sighted. (He) must wear glasses and only then he can see clearly.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||

| b. | 渠近视个□,要戴眼镜□,好看个□。 | ||||||||

| ɦi⁴ | dʑiŋ⁴zɿ⁶ | ɡə⁸ | jæ, | ʔjɒ⁵ | ta⁵ | ŋjæ⁴tɕiŋ⁵ | mə⁸, | ||

| 3sg | short-sighted | aff | prt | need | wear | glasses | prt | ||

| hɒ3 | kʰə̃⁵ | ɡə⁸ | jə⁸. | ||||||

| good | look | aff | prt | ||||||

| ‘He’s short-sighted and he can see only if he wears glasses.’ | |||||||||

The development of circumstantial possibility into participant-internal possibility was neglected in the early literature on modality, with the reverse pathway, participant-internal possibility > circumstantial possibility, generally being accepted by scholars (; ; ). With the addition of linguistic evidence from Southeast Asian languages, the proposed diachronic development from participant-internal possibility to circumstantial possibility was then revised (). () further confirms the pathway from circumstantial possibility to participant-internal possibility with the development of the Thai verb dây ‘emerge’ and the Japanese idek- ‘appear’. A view of bidirectional development between participant-internal and circumstantial possibility has now become mainstream ().

6.3. Circumstantial and Participant-Internal Possibility > Epistemic Possibility

We propose that in Jidong Shaoxing, the epistemic use of hɒ3 is the extension of both circumstantial and participant-internal possibility, contexts for both of which can be observed separately. Example (60) is understood as a case of epistemic possibility when the speaker makes a guess before fetching the clothes laid out in the sun. hɒ3 in this sentence can be interpreted as circumstantial ‘can’ if being in the sun long enough is considered as an enabling condition for drying the clothes.

Example (61) is a case of participant-internal–epistemic polysemy. Example (62) gives an ambiguous case of circumstantial, participant-internal, as well as epistemic interpretations.

Cross-linguistically, deontic–epistemic polysemy is well attested and studied. English must is a well-known example (). Even though hɒ3 can be used to express both deontic and epistemic meanings, we do not posit an evolutional relation between the two meanings in Jidong Shaoxing, as polygrammaticalization () may also be possible. The main reason for this conclusion is that a bridging context of deontic–epistemic polysemy is rarely observed among conservative speakers. The three conservative speakers in this study considered the sentence in (63) to suggest permission or weak obligation, while only the innovative speaker involved in this study claimed that the sentence can express both deontic and epistemic meanings.

For this study, we also tested quite a few deontic expressions formed by hɒ3 in epistemic contexts. The tests turned out to be failures with the three conservative speakers. One of the examples is given below. The clause hɒ3 tɕjə⁷hwɘŋ1 dzᴇ jə⁸ ‘(he) should get married’ expressed by hɒ3 in (64ii) is a speaker’s advice. Using it to answer the question ‘Is he married?’ in (65q) to express one’s presumption was ungrammatical for our conservative speakers but caused no problems for the innovative speaker, as shown in (65ai). Instead, the conservative speakers used ʔiŋ1kᴇ1 ‘should’ to form a presumption as an answer to the question, as in (65aii).

| Circumstantial–Epistemic | |||||||||

| (60) | 晒起□两件衣裳好燥□哉。 | ||||||||

| sa⁵-tɕʰi3 | doŋ | ljaŋ⁴ | dʑjᴇ̃⁶ | ʔi1ʑjɒŋ2 | hɒ3 | sɒ⁵ | doŋ | dzᴇ. | |

| dry.in.the.sun-inc | dur | several | clf | clothes | good | dry | prf | crs | |

| ‘The clothes in the sun may have dried.’ | |||||||||

| Participant-internal–Epistemic | |||||||||||||||||

| (61) | 渠一百斤都挑得来□,八十斤咸般也好挑个□。 | ||||||||||||||||

| ɦi⁴ | ʔjə⁷pa⁷ | tɕiŋ1 | tu1 | tʰjɒ1-tə⁷-lᴇ2 | lᴇ, | pa⁷zə⁸ | tɕiŋ1 | ||||||||||

| 3sg | one.hundred | a.half.kilo | all | carry-pot-come | prt | eighty | a.half.kilo | ||||||||||

| ɦæ2pæ1 | ɦa⁴ | hɒ3 | tʰjɒ1 | ɡə⁸ | jə⁸. | ||||||||||||

| certainly | also | good | carry | aff | prt | ||||||||||||

| ‘(Since) he can lift 50 kilos, he can/may certainly lift 40 kilos.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| Circumstantial–Participant-internal–Epistemic | |||||||||||||||||

| (62) | 毕业哉个说话,渠好做个老师{个□}。 | ||||||||||||||||

| pjə⁷ȵjə⁸ | dzᴇ | ɡə⁸ɕjo⁷ɦwo⁶, | ɦi⁴ | hɒ3 | tso⁵ | ɡə⁸ | lɒ⁴sɿ1 | ɡo⁸. | |||||||||

| graduation | crs | if | 3sg | good | do | clf | teacher | aff.prt | |||||||||

| ‘He can/may be a teacher after graduation.’ | |||||||||||||||||

| (63) | 五点钟哉,渠好去哉。 | ||||||

| ŋ⁴ | tjᴇ̃3tɕjoŋ1 | dzᴇ, | ɦi⁴ | hɒ3 | tɕʰi⁵ | dzᴇ. | |

| five | o’clock | crs | 3sg | good | go | crs | |

| ‘It’s five o’clock (and time to get off). He may/should leave.’ ‘It’s five o’clock (and time to get off). #He may probably be gone.’ | |||||||

| (64) | 渠年纪也不小□哉,好结婚哉□。 | |||||||||||||||

| (i) | ɦi⁴ | ȵjᴇ̃2tɕi⁵ | ɦa⁴ | fə⁷ | ɕjɒ3 | doŋ | dzᴇ. | |||||||||

| 3sg | age | also | neg | small | prf | crs | ||||||||||

| (ii) | hɒ3 | tɕjə⁷hwɘŋ1 | dzᴇ | jə⁸. | ||||||||||||

| good | marry | crs | prt | |||||||||||||

| ‘He’s not young. (He) should get married.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (65) | q- | 渠婚有有结□□? | ||||||||||||||

| ɦi⁴ | hwɘŋ1 | ɦjə⁴ | ɦjə⁴ | tɕjə⁷ | lᴇ | ɦa? | ||||||||||

| 3sg | marriage | have | have | marry | prt | prt | ||||||||||

| ‘Is he married?’ | ||||||||||||||||

| ai- | #渠好结婚□哉{个□}。 | |||||||||||||||

| #ɦi⁴ | hɒ3 | tɕjə⁷hwɘŋ1 | doŋ | dzᴇ | ɡo⁸. | |||||||||||

| 3sg | good | marry | prf | crs | aff.prt | |||||||||||

| ‘He may probably be married.’ (Elicitation) | ||||||||||||||||

| aii- | 渠应该结婚□哉{个□}。 | |||||||||||||||

| ɦi⁴ | ʔiŋ1kᴇ1 | tɕjə⁷hwɘŋ1 | doŋ | dzᴇ | ɡo⁸. | |||||||||||

| 3sg | should | marry | prf | crs | aff.prt | |||||||||||

| ‘He may probably be married.’ | ||||||||||||||||

Epistemic possibility is probably the latest layer of the semantic and functional extension of hɒ3. There are two main pieces of evidence in support of this hypothesis.

First, when denoting epistemic possibility, the use of hɒ3 is still dependent not only on its circumstantial possibility use, but in many cases, on the source meaning ‘fit to’. This means that there needs to be a certain enabling condition for a grammatical proposition of epistemic possibility realized with hɒ3, whose surface meaning corresponds to ‘may’ but whose underlying meaning is ‘it is the right or proper moment for’. Example (66) is one such grammatical example where hɒ3 is used to express a presumption based on the speaker’s judgement and knowledge. Here, the sentence was produced during the airtime of a frequently watched television program. Similarly, example (60) can also be read ‘it’s the right time for the clothes to have dried’.

In comparison, although (67) is similarly an expression of probability based on one’s judgement, the use of hɒ3 would be ungrammatical. As mentioned above, hɒ3′s epistemic use is still restricted by its source uses. Looking awful is neither an enabling condition for falling ill, nor reflective of the moment for falling ill. Rather, it is a sign of being ill.

| (66) | 介光折电视好开始□哉。 | ||||||

| ka⁵kwɒŋ1 | tsə⁷ | djᴇ̃⁶zɿ⁶ | hɒ3 | kʰᴇ1sɿ3 | doŋ | dzᴇ. | |

| now | clf | TV | good | begin | prf | crs | |

| ‘The TV show may have been on.’ | |||||||

| (67) | 渠人介难看,*好生毛病□哉□。 | |||||||||

| ɦi⁴ | ȵiŋ2 | ka⁵ | næ2kʰə̃⁵, | *hɒ3 | saŋ1 | mɒ2biŋ⁶ | doŋ | dzᴇ | ɒ. | |

| 3sg | person | so | out.of.sorts | good | have | sickness | prf | crs | prt | |

| ‘He looks awful and may be sick.’ (Elicitation) | ||||||||||

Second, different speakers show different degrees of tolerance for using hɒ3 to express epistemic possibility. The cases of (63) and (65) have already provided a glimpse into this situation. Examples (68) and (69a) were only accepted by our innovative consultant. Sometimes it is difficult to determine whether or not the epistemic meaning of hɒ3 can be accepted. We reproduce example (42) in (69b) to highlight cases of arbitrariness. The only difference between (69a) and (69b) is the subject. Our conservative consultants could only accept (69b), and when replacing the subject ‘car’ with the third person pronoun the sentence turns out to be ungrammatical.

Restrictions on using the epistemic hɒ3 reflect the fact that hɒ3 is in the process of functional extension or grammaticalization. As can be observed from the examples above, the generalization of the epistemic hɒ3 varies among different speakers. Still, all of this information suggests that the epistemic use of hɒ3 is its latest layer of extension.

| (68) | #渠今年好有五岁□哉。 | ||||||||||||

| #ɦi⁴ | tɕi⁴ȵjᴇ̃2 | hɒ3 | ɦjə⁴ | ŋ⁴ | sᴇ⁵ | doŋ | dzᴇ. | ||||||

| 3sg | this.year | good | have | five | year | prf | crs | ||||||

| ‘He may have been five years old this year.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||||||

| (69) | a. | #渠好来□哉。 | |||||||||||

| #ɦi⁴ | hɒ3 | lᴇ2 | doŋ | dzᴇ. | |||||||||

| 3sg | good | come | prf | crs | |||||||||

| ‘He is probably coming.’ (Elicitation) | |||||||||||||

| b. | 车好来□哉。 | ||||||||||||

| tɕʰjo1 | hɒ3 | lᴇ2 | doŋ | dzᴇ. | |||||||||

| car | good | come | prf | crs | |||||||||

| ‘The car/bus is probably coming.’ | |||||||||||||

6.4. Accelerating Factors

We have identified the auxiliary hɒ3 ‘fit to’ as the source of its modal meanings including ‘can’, ‘may’, and ‘should’. Other factors may also accelerate or generalize the extension of hɒ3.

First, hɒ3 itself can be used independently to ask for agreement, which is probably an extension from the meaning ‘good’, as in (70). Since asking for agreement presupposes permission, this use of hɒ3 can definitely promote extension to permission.

| (70) | 介我前拨侬换个,好? | |||||||

| ka⁷ | ŋo⁴ | ʑjᴇ̃2 | pə⁷ | noŋ⁴ | ɦwə̃⁶ | ɡə⁸, | hɒ3? | |

| so | 1sg | first | ben | 2sg | change | clf | good | |

| ‘I’ll change it for another one for you, OK?’ | ||||||||

Second, though rare, we do observe some contexts of ‘easy’-‘can’ polysemy, which means that ‘be easy to’ is also a possible source for ‘can’. Example (71) is a case where hɒ3 can either be interpreted as ‘be easy to’ or as the ‘can’ of circumstantial possibility, that is, either the thin and watery texture of corn porridge makes it easy to swallow, or one could drink the porridge (like drinking water). In addition, example (40) showed a case of ‘fit’-‘easy’-‘can’ polysemy, which can be interpreted as ‘(leaves) easily float on the surface of the water’.

The reason the meaning ‘be easy to’ is not identified as the source for the modal hɒ3 is that contexts suggesting ‘easy’-‘can’ polysemy are less frequent than those suggesting ‘fit’-‘can’ polysemy. Moreover, the sandhi patterns of hɒ3 are different when denoting these two different meanings. As given in the translations of (71), hɒ⁴3 haʔ⁵ denotes ‘easy to drink’, a sandhi pattern of forming a compound word, while hɒ⁴⁴ haʔ⁴ signifies ‘can drink’.

| (71) | □辰光六谷糊煞煞薄{个□},□□好呷个□。 | ||||||||

| haŋ⁵ | zɘŋ2kwɒŋ1 | lo⁸kwo⁷ | ɦu2 | sa⁷sa⁷bo⁸ | ɡo, | do⁶do⁶ | hɒ3 | ha⁷ | |

| dist | moment | corn | porridge | thin | aff.prt | ono | good | drink | |

| ɡə⁸ | la. | ||||||||

| aff | prt | ||||||||

| ‘The corn porridge (we used to eat before) was very thin. a. [hɒ⁴3 haʔ⁵]: It was easy to drink (like drinking water).’ Elicitation b. [hɒ⁴⁴ haʔ⁴]: (One) could drink (instead of chewing it, like drinking water).’ | |||||||||

Undoubtedly, these factors illustrated above contribute to the generalization of the modal uses of hɒ3. It is true that grammaticalization is unpredictable to a certain degree, but frequency of use still plays a role in expanding the possibilities a given form has for grammaticalization ().

6.5. Hao3 好 ‘Good’ in the History of Chinese

We have reconstructed the functional extension of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing in Section 6.1, Section 6.2 and Section 6.3 by adopting the model of context-induced grammaticalization proposed by (). Although our reconstruction of hɒ3 cannot be directly supported due to a lack of diachronic records of Jidong Shaoxing,7 it conforms to the evolution of hao3 好 ‘good’ (the etymon of hɒ3) in the history of Chinese. Based on Li’s work (2017), and diachronic analyses proposed by () and (), the evolution of hao3 in the history of Chinese is reorganized and adapted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evolution of hao in the history of Chinese.

According to (), (), and (), modal uses of hao3 can be first observed in Early Medieval Chinese (3rd century–6th century).8 During this time, it was used to express circumstantial possibility and could be interpreted as ‘fit to’ or ‘can’, as shown in (72). Compare this example with the Jidong Shaoxing example (26), reproduced here in (73).

The ‘fit’-‘can’ polysemy of hao3 persisted until its circumstantial possibility use began to decline in Modern Chinese, specifically during the Qing Dynasty. In contemporary Standard Mandarin, only the fossilized zhi3hao3 只好 ‘can only’ is used to denote circumstantial possibility. As shown in (74), the deletion of the adverb zhi3 ‘only’ is ungrammatical in Standard Mandarin.

| (72) | 羔有死者,皮好作裘褥,肉好做干腊,及作肉酱,味又甚美。 | |||||||||||||||

| gao1 | you3 | si3 | zhe3, | pi2 | hao3 | zuo⁴ | qiu2ru⁴ | rou⁴ | hao3 | |||||||

| lamb | have | die | nmlz | skin | good | do | fur.mattress | meat | good | |||||||

| zuo⁴ | gan1la⁴, | ji2 | zuo⁴ | rou⁴jiang⁴, | wei⁴ | you⁴ | shen⁴ | mei3. | ||||||||

| do | cured.meat | and | do | meat.sauce | flavor | also | very | pretty | ||||||||

| ‘(If) there’s a dead lamb, the fur [can be]/[fits to be] made into a mattress and the meat [can be]/[fits to be] made into cured meat and meat sauce which is extremely delicious.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| Qi Min Yao Shu · Yang Yang 齐民要术·养羊 (544ad) [Essential techniques for the welfare of the people · Raising sheep] | ||||||||||||||||

| (Cited from () and glossed and translated by S. Lü) | ||||||||||||||||

| (73) | Jidong Shaoxing | |||||||||||||||

| 甲鱼背好做药个□。 | ||||||||||||||||

| ka⁷ŋ2 | pᴇ⁵ | hɒ3 | tso⁵ | ɦja⁸ | ɡə⁸ | jæ. | ||||||||||

| soft.shell.turtle | back | good | do | medicine | aff | prt | ||||||||||

| ‘Turtle shells can be made into (Chinese traditional) medicine.’ | ||||||||||||||||

| (74) | Standard Mandarin | ||||||||

| 他腿断了,*(只)好在家休息。 | |||||||||

| ta1 | tui3 | duan⁴ | le, | *(zhi3) | hao3 | zai⁴ | jia1 | xiu1xi⁴. | |

| 3sg | leg | break | crs | only | good | at | home | rest | |

| ‘His leg is broken and he can only take a rest at home.’ | |||||||||

As indicated in Table 2, towards the end period of Late Medieval Chinese, which corresponds to the Song Dynasty (960ad–1279), a significant new meaning of hao3 emerged—the deontic meaning ‘should’. However, this use only lasted to Pre-Modern Chinese. See (75).

| (75) | 似这般汉,正好蓦头蓦面唾。 | ||||||

| si⁴ | zhe⁴ban1 | han⁴, | zheng⁴ | hao3 | mo⁴tou2mo⁴mian⁴ | tuo⁴. | |

| resemble | so | man | just | good | in.the.face | spit | |

| ‘A person like this, (one) should spit on him in the face.’ | |||||||

| Bi Yan Lu · 78 Ze 碧岩录·78则 (1125) [Blue Cliff Record · Verse 78] | |||||||

| (Cited from () and glossed and translated by S. Lü) | |||||||

A bit later than the deontic use of hao3, the interpretation of participant-internal possibility appeared in Pre-Modern Chinese during the Yuan and Ming Dynasties (1271–1644), as shown below. Note that () does not single out the meaning of participant-internal possibility for hao3.

Like the deontic use, the participant-internal possibility use of hao3 did not last long and was not further generalized.

| (76) | 您兄弟量窄,只好陪哥哥一小钟。 | ||||||

| nin2 | xiong1di⁴ | liang⁴ | zhai3, | ||||

| 2sg.hon | sibling | capacity | narrow | ||||

| zhi3 | hao3 | pei2 | ge1ge1 | yi⁴ | xiao3 | zhong⁴. | |

| only | good | accompany | brother | one | small | cup | |

| ‘I’m not good at drinking (alcohol) and I can only drink a small cup to accompany you.’ | |||||||

| Yuan Qu Xuan · Zhusha Dan 元曲选·朱砂担 (1616) [Selected Yuan Theatre Plays · A Picul of Cinnabar] | |||||||

| (Cited from () and glossed and translated by S. Lü) | |||||||

As for the meaning ‘be easy to’, the ‘easy’-‘can’ polysemy can also be observed for hao3, as in (77).

Nevertheless, as can be seen in Table 2, hao3′s meaning ‘be easy to’, considered as an evaluative meaning by (), emerged later than the meaning ‘fit to/can’, sometime between the Tang and the Five Dynasties (618–960ad) (see also ; ). This suggests that ‘be easy to’ is not the direct source for the modal uses of hao3. The meaning ‘be easy to’ for hao3 maintains an active status in Standard Mandarin.

| (77) | 嫂嫂,你如今真个不好过日子,不如跟着我一同回去住罢。 | |||||||

| sao3sao | ni3 | ru2jin1 | zhen1ge⁴ | bu⁴ | hao3 | guo⁴ | ri⁴zi | |

| sister-in-law | 2sg | now | indeed | neg | good | live | life | |

| bu⁴ru2 | gen1-zhe | wo3 | yi⁴tong2 | hui2-qu⁴ | zhu⁴ | ba. | ||

| inferior | follow-dur | 1sg | together | return-go | live | prt | ||

| ‘Sister, you [aren’t easy to]/[can’t] make a living now. It would be better to come to live with me.’ | ||||||||

| Yuan Qu Xuan · Ren Fengzi 元曲选·任风子 (1616) [Selected Yuan Theatre Plays · Ren Fengzi] | ||||||||

| (Cited from () and glossed and translated by S. Lü) | ||||||||

The evolution of hao3 in the history of Chinese parallels the extension of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing and supports our reconstruction of hɒ3. The fact that hao3 ‘good’ is used to denote weak obligation and participant-internal possibility in the history of Chinese sheds some light on the evolution of hɒ3 ‘good’ in Jidong Shaoxing. Both of these uses appeared much later than the circumstantial possibility use, suggesting that the chain ‘circumstantial possibility > participant-internal possibility’ for hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing is plausible. Furthermore, the emergence and generalization of hao3′s meaning ‘be easy to’ can also be mapped onto Jidong Shaoxing hɒ3. That ‘be easy to’ emerged later than the meaning of circumstantial possibility suggests the implausibility of identifying ‘be easy to’ as the source meaning for circumstantial ‘can’.

7. Conclusions

This paper has provided a case study on the modal uses of the lexeme hɒ3 ‘good’ in Jidong Shaoxing. The lexeme hɒ3 is a polysemous and multi-functional word. hɒ3 can serve as an adjective/adjectival verb ‘good, fitting, ready, done, ok’. Its modal uses include circumstantial ‘can’, participant-internal ‘can’, permission ‘may’, weak obligation ‘should’, and epistemic ‘can’. hɒ3 shows asymmetrical semantic extension in Jidong Shaoxing. While the positive form of hɒ3 possesses modal functions, the negated form fə⁷ hɒ3 only denotes ‘not good’ or ‘not suitable’.

We have proposed that it is from the meaning ‘fit to’ but not directly from the lexical meaning ‘good’ that the modal meanings of hɒ3 are derived. This pathway is different from the ‘good’ > deontic permission route found in some other languages (). Adopting the context-induced grammaticalization model, we have reconstructed the process of extension of hɒ3 in Jidong Shaoxing, proposing that the hɒ3 of ‘fit to’ has followed a multidirectional or polygrammaticalization pattern. This pattern contains an intermediate stage of circumstantial possibility in the development of both its deontic and participant-internal uses:

Chain 1: ‘fit to’ > circumstantial ‘can’ > deontic ‘may, should’.

Chain 2: ‘fit to’ > circumstantial ‘can’ > participant-internal ‘can’.

Within deontic modality, the hɒ3 of permission is reconstructed as the source for the hɒ3 of weak obligation, i.e., circumstantial ‘can’ > permission ‘may’ > weak obligation ‘should’.

Although the chain of circumstantial possibility > participant-internal possibility is cross-linguistically less common than the reverse, our proposition is based on linguistic facts in Jidong Shaoxing and conforms to the evolution of the etymon hao3 ‘good’ of hɒ3 in the history of Chinese. A similar pathway can be found in Chinese: ke3 可 ‘suitable’ > root possibility > ability (, ; see also ). Our findings contribute some new evidence for two proposed bidirectional developments in the modal domain: circumstantial ↔ participant-internal and deontic permission ↔ deontic necessity ().

The epistemic use of hɒ3 is proposed as the latest stage of extension in the current Jidong Shaoxing. It is from both circumstantial and participant-internal ‘can’ that the epistemic ‘can’ is developed:

Chain 3: circumstantial-participant-internal ‘can’ > epistemic ‘can, may’.

The epistemic use of hɒ3 is often restricted by the source meaning of circumstantial ‘can’ or ‘fit to’. Additionally, the degree of generalization of epistemic hɒ3 varies between different speakers.

The use of the lexeme hao ‘good’ as a modal verb can be considered a regional phenomenon. According to a preliminary cross-linguistic survey, this phenomenon is found across Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang Provinces, an area usually known as the Yangtze River Delta, which covers the entire Wu speaking area and some Jianghuai Mandarin 江淮官话 speaking areas. For Wu dialects, hao ‘good’ as a modal verb is reported in Chongming 崇明 (), Shanghainese (), Suzhou 苏州 (), Hangzhou 杭州 (), Shaoxing, Yuyao 余姚 (), Ningbo (), Xianju, Wenzhou 温州 (), and Jinhua 金华 (). For Jianghuai Mandarin, the phenomenon is attested in Nantong 南通 (), Yangzhou 扬州 (), and Nanjing 南京 (). In addition, hao as a modal auxiliary is also attested in some discontinuous areas in Guangdong and Taiwan, that is, in Jieyang Southern Min and Hakka, as mentioned at the beginning of the paper. Certainly, the modal uses of hao vary in different languages and dialects. More work needs to be carried out to figure out how the modal functions of hao extend and to what extent its modal uses can be generalized in individual languages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L.; methodology, S.L.; data analysis, S.L.; data collection, S.L. and X.H.; data transcription, X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, S.L. and X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Shanghai Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science, grant number 2022BYY005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments