Abstract

Studies of children’s narratives have shown that selecting appropriate forms to reintroduce a referent compared to retaining a referent is challenging because it requires the integration of different accessibility features. Bilingual children are more explicit than their monolingual peers when it comes to referent selection, especially in the context of reintroduction in null-argument languages. Whether different accessibility features influence referent choice in the context of reintroduction in bilingual and monolingual children remains to be investigated. Japanese narratives were elicited from Japanese–English school-age early bilinguals (n = 13) and their monolingual peers (n = 8) using a wordless picture book and video clip, and the linguistic means of referent reintroduction were analyzed in terms of recency, ambiguity, and pragmatic predictability. The analysis revealed that in terms of recency, bilinguals used more noun phrases (NPs) than null forms when the referent was highly accessible, thus exhibiting overexplicitness, whereas in terms of ambiguity, bilinguals used more NPs for less accessible referents, while monolinguals were not as explicit. Both groups were sensitive to accessibility. We argue that bilinguals are selectively redundant, suggesting that the overproduction is not due to the load of processing two languages but is a manifestation of cross-linguistic influence modulated by accessibility features. The results emphasize the importance of considering discourse features in identifying overexplicitness.

1. Introduction and Theoretical Background

1.1. Referential Choice and Information Structure in Narratives

The use of appropriate linguistic devices to establish referential cohesion or “interdependence across utterance” () is essential in narrative discourse (e.g., ; ; ; ; ). In order to realize this interdependence, marking the different degrees of mutual knowledge assumed between the speaker and listener, or information status, is essential (e.g., ; ; ; ). The most basic distinction of information status is new vs. given information, which is determined based on the availability of shared knowledge between the interlocutors (; ).

Due to the gradient nature of the level of sharedness, accessibility has been suggested as a concept that may best capture information status and its relationship between linguistic forms (; ; ); it can be defined as “the ease with which the mental representation of some potential referent can be activated in or retrieved from memory” (). During verbal interactions, it is assumed that participants create and retain non-linguistic representations of each referent or event. This process aids them in keeping track of the discourse topic and linking new referents to those already established in the mental representations of the speaker and listener ().

The varying information status of the referent is marked by different referential forms, such as noun phrases, pronouns, or null forms. The speaker selects the appropriate form of reference in each discourse context by assessing the level of accessibility of the referent in the listener’s mind (; ). Generally, less accessible referents are stated in more salient forms (noun phrases), while more accessible referents are expressed in less prominent forms (pronouns, null forms). Additionally, language-specific syntactic rules determine whether the reduced forms are, in principle, restricted to pronouns (e.g., English) or include null forms as a grammatical option (e.g., Spanish, Italian, Japanese, Korean) (; ). In other words, choosing the appropriate, language-specific forms to follow a referent in a narrative thread and managing shared and unshared information is key to the effective communication of events.

In narrative stretches, when a referent appears for the first time, full noun phrases are employed, as they provide the most salient and informative cues, effectively conveying the referent to the listener. When maintaining a referent or referring to the same character mentioned in the previous clause, non-lexical forms like pronouns or null forms are prototypically used since the referent is easily accessible and at the forefront of the listener’s mind. Regarding reintroduction, when mentioning an entity or character already introduced but temporarily set aside, both lexical and non-lexical forms may be used, depending on various discourse conditions ().

It is important to note that the difficulty of assessing the listener’s mind can vary depending on the type of discourse (; ). Whereas the listener’s accessibility of the referent can be constantly confirmed and adjusted during interaction in a conversational or narrative discourse embedded in conversational interaction (), fictional elicited narratives are “decontextualized discourse” (). That is, narratives based on pictures or other prompts are disconnected from the mutual exchange taking place, which can make it more challenging for the speaker to accurately assess the listener’s discourse model as there are less cues as to whether or not the referent was active or inactive in the latter’s mind. Thus, choosing referential expressions for successful storytelling can be a cognitively advanced skill.

1.2. The Development of Referential Choice in Child Narratives

Many studies examining how young monolingual children develop referring expressions in elicited narratives indicate that gaining proficiency in adult-like language is a gradual and prolonged journey (; ). The functions of introduction, reintroduction, and maintenance vary in evaluating the listener’s understanding of the relevant referent and are thus mastered at distinct developmental stages. Cross-linguistic research repeatedly demonstrates that young children are attuned to maintaining topics and begin to use reduced forms like pronouns or null forms for tracking referents around the age of four (; ; ; ).

Contrarily, children’s referential choices in introductory contexts do not exhibit adult-like usage (constant use of forms indicating new information) until they reach about ten years of age or older (; ; ; ; ). Research indicates that younger children generally introduce characters in discourse using markers that denote given information (e.g., NPs with definite markers in English or null forms in Japanese). These results suggest that distinguishing between new and given information in the introductory context or assessing the listener’s level of knowledge about the referent at the beginning of a story is relatively challenging for children compared to retaining a referent in discourse.

Researchers also contend that selecting the right linguistic device in the reintroduction context poses the greatest challenge and requires even more time to develop (; ; ; ). Here, the referent has been introduced into the discourse but does not directly precede the focused utterance, showcasing “characteristics of both reference introduction and maintenance” (). Therefore, reintroduction can be a complex task as speakers need to constantly monitor discourse and assess the listener’s knowledge to choose reliably interpretable referential forms despite the displacement of the referent from its prior mention. Previous studies on children acquiring German or Italian (; ) showed that preschoolers tended to use reduced forms (such as pronouns or null forms) when maintaining the main characters and full NPs for other characters, indicating that their choice is modulated by the topicality of the referent rather than by assessing the listener’s level of knowledge. By the time children reach nine to ten years old, they select more fuller NPs for referent reintroductions which are closer to the adult norm, that is, freed from the preference for the reduced form based on topicality. These selections reflect distinctions in accessibility features such as ambiguity or predictability.

1.3. Accessibility Features Modulating Referential Choice in Narrative Discourse

Within the various discourse properties that impact the accessibility of referents (refer to for an overview), an increasing number of studies indicate that certain factors can specifically influence the selection of referring expressions during reintroduction, namely, recency, ambiguity, and predictability. Recency refers to the distance or number of intervening clauses to the previous mention in the discourse, which is assumed to be an important factor for the speaker in assessing the referent’s degree of activation in the listener’s mind (; ). This factor is the most relevant in the context of reintroduction, as the introduction lacks any prior mention of the referent and in maintenance consistently refers back to the last statement. Research involving monolingual children and adults indicates that less prominent forms are selected when the reintroduced referent is close to its previous mention, owing to its heightened prominence or salience in the speaker’s memory. Conversely, more salient forms are favored when the referent reappears after a significant absence of discourse (e.g., ; ).

The existence of potential characters in the immediate discourse context, or ambiguity, also matters. When multiple characters are present in the scene, especially with overlapping features (such as gender and animacy), the speaker needs to disambiguate the referent, which requires more attention on their behalf (). This is particularly the case in reintroduction, as the referent is less accessible due to reference shift, making disambiguation a crucial process in identifying the referent after mentioning other characters. Previous studies indicate that speakers tend to choose a more reduced form when a character is the sole potential referent in a scene. Conversely, speakers tend to opt for a more explicit form when multiple characters are present, leading to the greater use of full forms (NPs) (; ).

Pragmatic predictability (; ; ) is the predictability of a referent based on verb semantics or topicality. Predictability influences referential choices during reintroduction, as the degree of inferability of referents aligns with their accessibility. Specifically, the more predictable a referent is, the more accessible it becomes (). Research indicates that referents that can be inferred from verb semantics or prior discourse are generally more prone to being expressed in reduced forms (; ).

1.4. Bilingual Development and CLI

It has been consistently observed that in both spontaneous conversational data among preschoolers and elicited narratives in school-age children, early bilinguals tend to use more overt forms (NPs or pronouns) compared to their monolingual peers, who in the same context naturally leave the referent unmentioned in languages that allow null forms (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; in conversational data in preschool children; ; ; ; ; ; in elicited narratives). This is widely known as “over-production” () or “overspecification” (). There are two representative views on why this occurs: cross-linguistic influence (CLI) and processing demands. Earlier studies analyzed overproduction as a case of interlingual influence; that is, bilinguals’ tendency to extend the use of overt forms in languages such as English, in which the use of null forms are restricted to limited contexts (; ), to the language in which null forms are the more preferred option (e.g., ; ). In particular, the Interface Hypothesis (), which states that structures requiring both syntactic and pragmatic/semantic decisions (rather than purely syntactic phenomena) are more likely to induce transfer, gained much support (e.g., ; ). Later studies (e.g., ; ) have highlighted the processing aspect of the syntax–pragmatics interface structure, arguing that the burden of incorporating multiple levels of information (e.g., knowledge of syntax and pragmatics) results in selecting overt forms or the “safer” option to avoid miscommunication rather than CLI, since overproduction is found regardless of the language pairs being acquired (e.g., null argument–null argument language pair) (e.g., ). This is not without counter-evidence, however, which points to the fact that two null argument languages can have different structures to trigger transfer (see ; for details). As () argue, the processing effort can create a linguistic context susceptible to influences from other languages.

Among the studies supporting the claims mentioned above, recent research on narratives indicates that bilingual children who acquire languages with both null and non-null arguments use more overt forms (NPs) in null argument languages than their monolingual peers, primarily in reintroduction contexts as opposed to maintenance (; ). As the literature on narrative development suggests, reintroduction requires the consideration of multiple accessibility features when choosing the referential form so that the listener can reliably interpret the referent despite displacement. This leads to the assumption that such complexity may constitute the vulnerability for CLI. The question then arises as to exactly which accessibility features induce overproduction in bilinguals. Chapter 5 of ’s () dissertation is one of the very few studies that demonstrated how accessibility features such as distance and competition can modulate referential choice among L2 learners; however, early bilinguals are yet to be investigated. Furthermore, the observed explicitness has not been examined in terms of accessibility features; specifically, it is unclear if the explicitness noted in bilingual reference production is redundant or serves a purpose. This study investigated the connection between accessibility features and referential choices in Japanese narratives produced by Japanese–English bilingual children.

1.5. Referential Expressions in Japanese

As discussed in Section 1.1, a typical Japanese reduced form of a referent is the null form or ellipsis in both narrative (; ) and conversational discourse (). The subjects and objects can be left unmentioned when the referent is recoverable from the discourse and/or physical context. No grammatical markers, such as the subject–verb agreement in Spanish or Italian, signal the referent of an unmentioned argument (), although it can be determined from certain types of predicate forms such as honorifics, passive forms (), internal state predicates (; ), or predicates of direct experience (). Overt pronouns in Japanese are used only in restricted contexts (; ). Third-person personal pronouns (e.g., kare “he”, kanojo “she”, karera “they”) are far more infrequent compared to null forms (). First- and second-person pronouns have several different forms and are selected based on sociolinguistic conditions such as the gender of the speaker and the formality of the situation (boku for male/informal, watashi for female or neutral/formal) (; ).

Although we use the term “null” in this study as a comparable concept to English null forms, researchers argue that for Japanese, especially in conversational discourse, the concept of a “zero” or “null” anaphora/pronoun does not fully explain the phenomena because nothing is “missing” (; ). The idea of something “missing” assumes a fixed argument structure, but the structure may not be determined and pragmatics and semantics play a crucial role in the interpretation of the unmentioned referent. Drawing on the theoretical framework of frame semantics () and Grice’s Cooperative Principle, () contends that ellipsis in Japanese is not equivalent to zero pronouns (absence of syntactic argument) but is “underdetermined” (p. 104). Speakers and listeners assume that the unmentioned referent (“inferable”) can be understood based on verb semantics and ongoing discourse and that explicit forms are used only when the speaker feels the need to “ensure” the identity of the specific member in the event.

When introducing referents in narrative discourse (marking new information), NPs in the subject position are generally followed by the subject marker ga. The object marker o or dative marker ni (to mark indirect objects) follows if the referent is in the object position. In contrast, null forms are generally used for referent maintenance (marking given information), although NPs with the topic/contrast marker wa (or ga, which can be used for emphasis) or object marker o or ni can appear in a subsequent mention. In the reintroduction context, NPs (with any of the particles above) and null forms are available options, depending on how the speaker perceives the shared knowledge with the listener (; ). Particles such as the inclusive marker mo can also be used if referring to an additional referent.

In English, on the other hand, argument omissions are ungrammatical in most cases, except in a few restricted contexts such as imperatives (e.g., Come here) or informal questions involving auxiliary drops (e.g., Want milk?) () or subjects of coordinate clauses (e.g., Aki came and Ø had dinner) (). Instead, pronouns account for the majority of reduced forms. When introducing a referent into a narrative, an indefinite article precedes the NP to indicate new information. Pronouns are typically used in maintenance, although other options such as the demonstrative this/that or definite article the preceding the NP are available. When reintroducing a referent, options include both pronouns and NPs marked by a definite article as well as demonstratives (; ; ).

1.6. Research Questions

Building on the previous finding that reintroduction can be particularly vulnerable to CLI, resulting in the overproduction of NPs in the bilinguals’ Japanese narratives, the current study addresses the following questions:

- (1)

- Which accessibility features (recency, ambiguity, predictability) contribute to bilingual and monolingual differences in reference choice (NP, pronoun, null), and how are they different?

- (2)

- If bilinguals use more NPs than monolinguals, are these always “redundant”? That is, are these restricted to accessible contexts?

We focused on the Japanese narratives of bilingual children because the directionality of CLI is expected to be from English to Japanese and not vice versa, which has been confirmed by previous research (e.g., ). We chose to analyze the animate characters in elicited third-person narratives in order to better capture the possible variation in children’s referential choice patterns.

If bilinguals generate more NPs than monolinguals only when the referent is more accessible—such as being more recent, ambiguous, or predictable—and not when it is less accessible (more distant, unambiguous, or unpredictable), then the findings would support the processing theory of overproduction. This suggests that bilinguals may produce unnecessary overt forms, contrary to the accessibility principle, due to a processing burden to ensure the referent is communicated without ambiguity. Conversely, if bilinguals use more NPs than monolinguals in less rather than more accessible situations, it indicates that bilinguals provide more information and are not always overly explicit, which would challenge the processing theory account.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

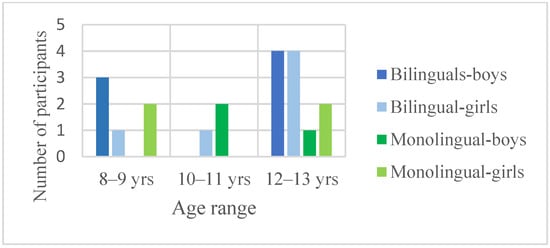

This research is part of a broader study investigating the elicited third-person narratives of Japanese–English bilingual children alongside their monolingual counterparts in each language, as detailed by (). The study included 13 Japanese–English simultaneous/early successive bilingual children (7 boys and 6 girls) aged 8 to 13 years and 7 Japanese monolingual peers (4 boys and 3 girls) within the same age range1. As shown in Figure 1, bilinguals and monolinguals were distributed in a roughly similar manner within each age range, although bilinguals were clustered more at the older range (12–13).

Among the bilingual participants, nine were simultaneous bilinguals who had been exposed to both Japanese and English from birth, while four were early successive bilinguals who first learned Japanese before being introduced to English during or prior to their elementary school years. In the current study, we group them together since there is evidence that both simultaneous and successive bilinguals show similar developmental patterns in language features acquired later in life, such as discourse-pragmatic features (e.g., ).

Figure 1.

Participant age range and gender.

As is reported in (), overall, our bilingual participants exhibited a slight dominance in Japanese. Language dominance, defined as the relative proficiency in both languages (; ), is likely a significant factor affecting multiple facets of bilinguals’ language performance, including CLI (e.g., ; ; ; ). Based on the assumption that dominance is multidimensional, we evaluated the overall dominance of the children by integrating the linguistic (language proficiency), functional (language use in different contexts), and external (input) components following (). First, the linguistic component was measured via the linguistic complexity of their oral narratives using the subordination index (SI)2, which has been considered to reliably reflect proficiency levels (; ). Our analysis demonstrated that the complexity measure aligned closely with that of their monolingual peers in Japanese but was lower in English, suggesting a relative dominance in Japanese. Second, the functional component, which refers to the distribution of the two languages across different domains in the children’s lives, was evaluated based on the responses to the language background questionnaire () or informal interviews. This was because we started using the questionnaire after we collected the first round of our data collection. We found that although some used English mainly in the home with one of their parents while others used English only in the school context, most participants used Japanese among their peers, which is considered to pose a strong influence on children’s language dominance (). Thus, the analysis also suggests that the children are likely to be dominant in Japanese. Third, for the external component, the language of the community was taken into account, as research suggests that even children in foreign language immersion contexts are generally more dominant in their community language (). Generally speaking, in Japan, Japanese plays a significant role in many aspects of children’s daily lives, including media consumption and community engagement, and the community the children were embedded in was not an exception. Thus, considering the three elements, we concluded that bilinguals tend to be more dominant in Japanese (refer to for further information).

2.2. Data Collection

We used data from () for the current analysis. Narrative data were elicited using the wordless picture book Frog, where are you? (), which consists of 24 scenes involving 8 characters, and a speechless animation video clip, The museum guard (), which is approximately 5 min long and involves Charlie Chaplin and 7 other characters. The Frog story was chosen for its frequency in narrative elicitation studies, while the Chaplin video was chosen for its comparability to the Frog story in terms of its length and the number of characters (2 main characters and 6 others). Different methods were employed to generalize the observed tendency across the various types of elicitation (book vs. video) and compensate for the small sample size of participants. They were analyzed separately in case there were crucial differences between the two types of data.

The researchers met each child individually, either at their home or at the researchers’ residences. We aimed to establish a relaxed, friendly, and natural atmosphere, enabling the children to share their stories comfortably. The children first recounted the Frog story in English, followed by the Chaplin story in the same language. After a brief break, they narrated both stories in Japanese, maintaining the original order. Before recording, they were instructed to preview the book or video to prepare for their narration. We adhered to the naïve listener condition (), meaning only the narrator could view the book or video and was encouraged to convey the story in detail, ensuring clarity for the listener. Following the approach of () and similar research, we avoided asking questions and focused on providing ample backchanneling to indicate our attentiveness and encourage them to continue speaking. Only Japanese narratives were utilized in this study analysis.

2.3. Transcription and Coding

The speech samples were transcribed and coded by trained research assistants fluent in both languages using the JCHAT format (). Quantitative analyses were conducted using CLAN (). For the previous project (), the child’s utterances with animate referents were first coded according to (1) the grammatical role: subject or object; (2) the discourse context of occurrence: introduction, reintroduction, and maintenance (); and (3) the form of the referent: noun phrase, pronoun, and null form (). Building on the coding just described, in the current study, linguistic devices children used to reintroduce the referent were further coded in terms of (1) recency (number of intervening clauses from the previous mention) (; ; ; ); (2) ambiguity (competing characters) (; ; ); and (3) pragmatic predictability of the referent (; ; ). For the current analysis, referents in both the subject and object positions were included to consider all animate characters in the intervening clause, although the majority of referents were in the subject position. We did not code the characters that appear in the adnominal position (e.g., otokonoko no petto no kaeru “the frog which is the boy’s pet”, hachi no su “the nest of the bees”) as the focus is on the character being modified.

For recency, we counted the number of intervening clauses from prior mentions, including both overt and reduced forms, following (). For example, in the following excerpt, “otokonoko (the boy)” in line 3 is one clause after the previous mention in line 1, “otokonoko”.

| Example 1: B-12 (bilingual, 9 years old) | ||||

| 1. あるところに男の子がいました。 | ||||

| arutokoroni | otokonoko | ga | imashita. | |

| once upon a time | boy | NOM | be-PAST | |

| ‘Once upon a time there was a boy.’ | ||||

| 2. ある夜、その男の子のペットのカエルがゲージから逃げ出しました。 | |||||||

| aru yoru | sono otokonoko | no | petto | no | kaeru ga | geeji kara | |

| one night | that boy | GEN | Pet | GEN | frog NOM | gage LOC | |

| nigedashiteshimaimashita. | |||||||

| escape-regrettably-PAST | |||||||

| ‘One evening, the Frog, the boy’s pet, escaped from the cage.’ | |||||||

| 3. 男の子は起きて、 | |||

| otokonoko wa | okite. | [after 1 intervening clause] | |

| Boy TOP | wake-up-TE | ||

| ‘The boy wakes up, and,’ | |||

Ambiguity was examined for whether there were multiple choices present in each scene. A boy, Frog, and dog appear in the scene in the following example. In line 4, three possible referents exist for “to fall asleep”. Therefore, it was coded as having multiple characters, which created ambiguity. If no such characters were present, they were coded as having a single character.

| Example 2: B-6 (bilingual, 9 years old) | ||||||||

| 1. 一人の男の子が犬、じゃなくてカエルを拾いました。 | ||||||||

| hitorino | otokonoko | ga | inu | janakute | kaeru | o | hiroimashita. | |

| one | boy | NOM | dog | COP-NEG-TE | frog | ACC | pick-PAST | |

| ‘A boy found a dog, no, a Frog.’ | ||||||||

| 2. 犬が瓶の中を見てます。 | |||||

| inu ga | bin no | nakaaka | o | mitemasu. | |

| dog NOM | jar GEN | inside | ACC | looking-NONPAST | |

| ‘The dog is looking into the jar.’ | |||||

| 3. やがて夜になったので | ||||

| yagate | yoru | ni natta | node | |

| eventually | night | become-PAST | therefore | |

| ‘As night came on,’ | ||||

| 4. 男の子は寝てしまいました。 | ||||

| otokonoko | wa | neteshimaimashita. | [multiple possible characters] | |

| boy | TOP | sleep-completed-PAST | ||

| ‘The boy fell asleep.’ | ||||

We also looked at the pragmatic predictability of a referent—whether it has a pragmatic/textual/semantic link to a previous mention. In Example 3, the speaker explains in line 1 that a Frog is put into a jar; in line 3, the referent for “got out” can be predicted from this information.

| Example 3: B-7(bilingual, 13 years old) | |||||||||||||

| 1. 夜に、えっと、犬と男の子がカエルを、ん、瓶の中に入れて[//]入れました。 | |||||||||||||

| yoru | ni | e:tto | inu | to | otokonoko | ga | kaeru | o | n: | bin | no | naka ni | |

| night | at | Um… | dog | and | boy | NOM | frog | ACC | Um… | jar | GEN | inside LOC | |

| irete [//] iremashita. | |||||||||||||

| put-inside-PAST | |||||||||||||

| ‘At night, uh, a dog and a boy put a Frog in a jar.’ | |||||||||||||

| 2. でもその瓶は蓋がしまってなくて、 | |||||||

| demo | sono | bin | wa | futa | ga | shimattenakute | |

| but | that | jar | TOP | lid | NOM | not-closed-and | |

| ‘But since the jar did not have a lid,’ | |||||||

| 3. カエルが出てしまいました。 | ||||

| kaeru | ga | deteshimaimashita. | [predictable from previous discourse] | |

| frog | NOM | go-out-completed-PAST | ||

| ‘the Frog got out of it.’ | ||||

The referent can also be predicted if the verb restricts the agent of the action. For example, the agent trapping the Frog semantically limits the referent to the boy, not the dog, as shown in Example 4.

| Example 4: B-8 (bilingual, 13 years old) | ||||||||||

| 1. たぶん男の子がカエルを瓶の中に閉じ込めて | ||||||||||

| tabun | otokonoko | ga | kaeru | o | bin | no | naka | ni | tojikomete | |

| Perhaps | boy | NOM | frog | ACC | jar | GEN | inside | LOC | confine-TE | |

| [predictable from verb semantics] | ||||||||||

| ‘Perhaps the boy trapped the Frog in the jar.’ | ||||||||||

2.4. Analysis

This study compares the linguistic strategies bilingual children use to reintroduce a referent with those of their monolingual peers, focusing on (a) recency, (b) ambiguity, and (c) predictability. The aim is to identify any differences in referent choices between bilinguals and monolinguals. Following the methodology of (), referential forms were categorized based on accessibility features, distinguishing between referents of high vs. low accessibility for each accessibility feature. A summary of this classification is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The classification of high and low accessibility for each accessibility feature.

Table 1.

The classification of high and low accessibility for each accessibility feature.

| Accessibility | High Accessibility | Low Accessibility |

|---|---|---|

| Referential Form | Null (>NP) | NP (>Null) |

| 1. Recency: number of intervening clauses (IC) | 1 to 2 IC | 3 or more IC |

| 2. Ambiguity: # of characters in the scene | Single character | Multiple characters |

| 3. Predictability: Semantic implication | Predictable from verb semantics/previous discourse | Unpredictable |

Regarding recency, high accessibility (High-A) refers to referents with fewer intervening clauses between the previous mention and referent. In contrast, low accessibility (Low-A) pertains to referents that feature additional intervening clauses. Following (), the occurrences of referents with one, two, and three or more intervening clauses were counted. In the current study, those with one to two intervening clauses were pooled (due to the small number of occurrences with two intervening clauses) and classified as High-A referents, while those with three or more intervening clauses were considered Low-A referents. We examined if there were different tendencies in the distribution of the referential forms.

In order to analyze the effect of ambiguity, we followed () and defined High-A as having a single possible character in the immediate discourse context. In contrast, Low-A referents were those with multiple possible characters in the same scene. Each referential form was marked as having single or multiple characters to indicate ambiguity.

Regarding predictability, referents were categorized as High-A when inferable from the verb semantics or preceding context, as described in Examples 3 and 4 in the previous section. On the other hand, they were considered Low-A if they were unpredictable from the verb semantics or context and thus required an overt referent. Each referent was coded as either predictable or unpredictable by examining the verb semantics and contextual information.

Bilingual and monolingual comparisons were conducted for each accessibility feature within both High- and Low-A referents to examine if bilinguals and monolinguals showed different referential choice patterns in different accessibility contexts. For each accessibility feature, the mean percentage of each referential form (NP, pronoun and null) used across all referents in each story were calculated to observe the referential choice patterns in each context. Generalized Linear Model (GLM) was used to test the interaction between accessibility (High vs. Low) and group (bilingual vs. monolingual) on the outcome variable (the use of NP), i.e., we examined whether the effect of accessibility (High vs. Low) on the outcome variable (the use of NP) differs between bilinguals and monolinguals. A Poisson GLM with a log link was used to model the use of NP.

3. Results

3.1. Recency

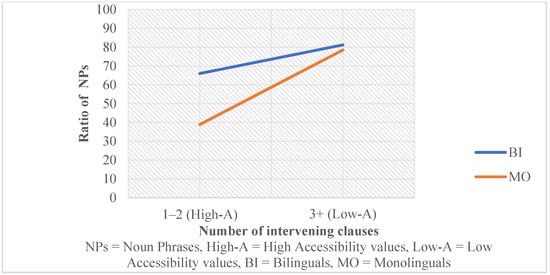

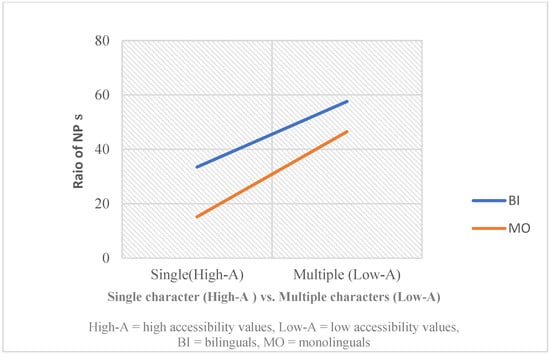

Table 2 and Table 4 illustrate the connection between the number of intervening clauses and the average percentage of each referential form used across all referents in the Frog and Chaplin stories, respectively. Figure 2 and Figure 3 provide a graphical representation of these tables. Given the scarcity of pronouns (two or fewer), they were merged with null forms for the statistical analysis. Table 3 and Table 5 present the results of the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis for the Frog and the Chaplin data, respectively.

3.1.1. Recency: Frog Story

We first report the bilingual–monolingual comparisons among referents with high vs. low accessibility for the Frog story. Within the High-A referents, bilinguals and monolinguals exhibited different referential choice patterns, where bilinguals showed a clear preference toward the use of NPs (NP 66.0% vs. null and pronoun combined 34.0%) while monolinguals preferred null forms (NP 38.9% vs. null 61.6%). More specifically, monolinguals tended to leave more than half of the referents unexpressed, assuming they were still active in the listener’s mind, whereas bilinguals preferred explicit forms despite their proximity to the prior mention. Within the Low-A referents, on the other hand, both bilinguals and monolinguals showed a comparable distribution of forms. Both groups of children used more NPs than null forms (bilinguals: NP 81.2% vs. null and pronoun combined 18.8%; monolinguals: NP 78.5% vs. null 21.5%).

When comparing between different levels of recency within each group, we observe that both groups of children showed different patterns. Bilinguals used more NPs than null forms at both levels, but usage was strongly skewed toward NPs within the Low-A referents (High-A: NP 66.0% vs. null and pronoun combined 34.0%; Low-A: NP 81.2% vs. null and pronoun combined 18.8%). Monolinguals, too, exhibited different tendencies depending on recency, showing a preference for null forms within High-A referents (NP 38.9% vs. null 61.6%) and a clear preference for NPs in Low-A referents (NP 78.5% vs. null 21.5%). Thus, the data suggest that in both bilingual and monolingual children the reference forms become more focused on NPs when the referent is distant from the previous mention.

Table 2.

The mean percentages of referring expressions used in contexts with 1–2 and 3 or more intervening clauses by bilingual and monolinguals (Frog) (frequency in parenthesis).

Table 2.

The mean percentages of referring expressions used in contexts with 1–2 and 3 or more intervening clauses by bilingual and monolinguals (Frog) (frequency in parenthesis).

| Bilingual (n = 13) | Monolingual (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | |

| 1–2 IC | 66.0% | 34.0% | 100% | 38.9% | 61.6% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (123) | (60) | (1) | (184) | (33) | (46) | (0) | (79) |

| 3+ IC | 81.2% | 18.8% | 100% | 78.5% | 21.5% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (89) | (14) | (4) | (107) | (37) | (8) | (0) | (45) |

Note. IC = number of intervening clauses, High-A = high accessibility values, Low-A = low accessibility values.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the mean percentage of NPs and the number of intervening clauses used by bilinguals and monolinguals (Frog).

In order to examine the effect of group and accessibility on the outcome variable, we compared a null model with a full model that included the two main effects and their interaction. The full model showed a significantly better fit (Χ2 = 14.478, p = 0.0023); that is, group (bilinguals vs. monolinguals), accessibility (high vs. low), and the interaction between the two account for the differences in NP use across different observations. The GLM analysis demonstrates that there is a significant group effect: that is, monolinguals are less likely (negative estimate) to use NPs than bilinguals (p = 0.01379). The effect of accessibility on NP use is not statistically significant (p = 0.1163), although the interaction between group and accessibility shows a weak significance (p = 0.08885). Thus, the data suggests a marginal effect of accessibility on group: monolinguals use more NPs under low accessibility, meaning that monolinguals are more likely to be affected by accessibility (recency) whereas bilinguals are not as sensitive to the level of accessibility.

Table 3.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Recency (Frog).

Table 3.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Recency (Frog).

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.403 | 0.090 | −4.467 | 7.942 × 10−6 ** |

| GroupB | −0.483 | 0.196 | −2.463 | 1.379 × 10−2 * |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.219 | 0.139 | 1.571 | 1.163 × 10−1 |

| GroupB × AccessibilityLow | 0.471 | 0.277 | 1.702 | 8.885 × 10−2 + |

Note. ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, + = p < 0.1

3.1.2. Recency: Chaplin Story

Overall, for the Chaplin story, the tendency resembled that of the Frog data. In the High-A referents, both bilinguals and monolinguals showed comparable patterns: they used more null forms than NPs (60.5% vs. 39.5% and 74.3% vs. 25.7%, respectively). Yet it is worth noting that bilinguals did not show as strong a preference for null forms (null and NP almost balanced) as observed in the monolingual data, thus exhibiting a slight preference for using explicit forms compared to their monolingual peers. Within the Low-A referents, the results closely resembled those from the Frog narrative. Both bilinguals and monolinguals showed similar distributions using more NPs than null forms (79.8% vs. 20.2% and 74.8% vs. 25.2%, respectively) (Table 4).

Table 4.

The mean percentages of referring expressions used in contexts with 1–2 and 3 or more intervening clauses by bilingual and monolinguals (Chaplin) (frequency in parenthesis).

Table 4.

The mean percentages of referring expressions used in contexts with 1–2 and 3 or more intervening clauses by bilingual and monolinguals (Chaplin) (frequency in parenthesis).

| Bilingual (n = 11) | Monolingual (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronouns | Total | |

| 1–2 IC | 39.5% | 60.5% | 100% | 25.7% | 74.3% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (72) | (98) | (1) | (171) | (18) | (61) | (1) | (80) |

| 3+ IC | 79.8% | 20.2% | 100% | 74.8% | 25.2% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (63) | (16) | (0) | (79) | (30) | (12) | (1) | (43) |

Note. IC = number of intervening clauses, High-A = high accessibility values, Low-A = low accessibility values.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the mean percentage of NPs and the number of intervening clauses used by bilinguals and monolinguals (Chaplin).

As was the case in the Frog data, the distribution of forms within High-A and Low-A referents showed different trends for both bilinguals (High-A: NP 39.5% vs. null and pronoun combined 60.5%; Low-A: NP 79.8% vs. null 20.2%) and monolinguals (High-A: NP 25.7% vs. null and pronoun combined 74.3%; Low-A: NP 74.8% vs. null and pronoun combined 25.2%). The data thus suggest that when the referent is less accessible in recency, the tendency to opt for NPs increases dramatically in both groups of children.

To access how group and accessibility influence the outcome, we compared a null model with a full model that included the two individual effects as well as their interaction. The full model showed a significantly better fit (Χ2 = 26.726, p = 0.000006719); that is, monolinguals and bilinguals behave differently, accessibility level affects NP use, and group and accessibility interaction might influence the effect. The GLM analysis demonstrates that both group and accessibility significantly influence referential choice (p = 0.0212 for group, p = 0.00216 for accessibility). Monolinguals use significantly fewer NPs (negative estimate) than bilinguals, and NP use is more frequent in low accessibility context than in high accessibility context in both groups. The combined effect of the two is marginal but significant (p = 0.0665), meaning that the effect of accessibility may differ between the groups: monolinguals are more likely to be affected by recency (Table 5).

Thus, the statistical analysis of both Frog and Chaplin data demonstrates that recency contributes to bilingual–monolingual differences: monolinguals’ use of NPs is more likely to be impacted by the level of recency.

Table 5.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Recency (Chaplin).

Table 5.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Recency (Chaplin).

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.859 | 0.118 | −7.290 | 3.099 × 10−13 *** |

| GroupB | −0.607 | 0.264 | −2.304 | 2.120 × 10−2 * |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.571 | 0.186 | 3.067 | 2.164 × 10−3 ** |

| GroupB × AccessibilityLow | 0.681 | 0.371 | 1.835 | 6.654 × 10−2 + |

Note. ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, + = p < 0.1

3.2. Ambiguity

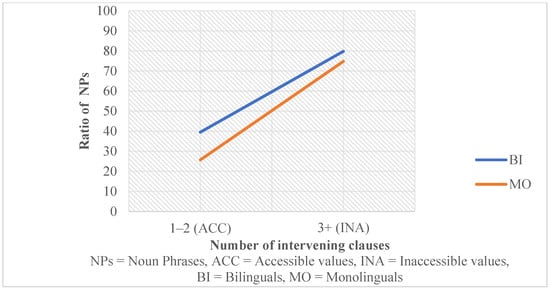

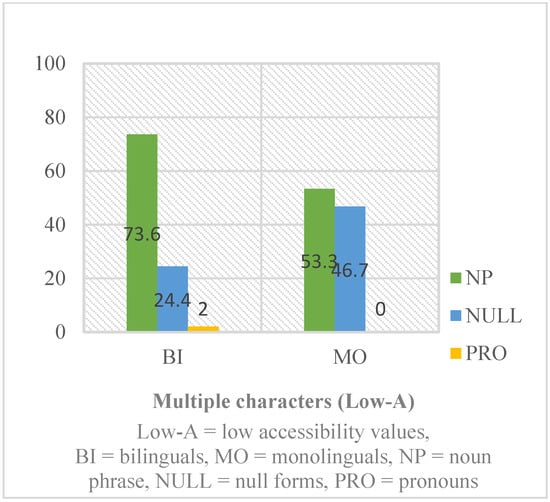

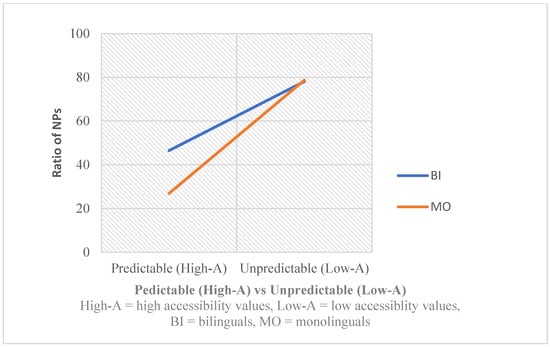

Table 6 and Table 8 illustrate the average percentages of referring expressions used by bilinguals and monolinguals within High-A (single character) and Low-A (multiple characters) referents for the Frog story and Chaplin narrative. Figure 4 graphically presents the data from Table 6, while Figure 5 displays the information from Table 7. For statistical analysis, pronouns were combined with null forms due to their low occurrence. Table 7 and Table 9 show the results of the GLM analysis for the Frog and the Chaplin data, respectively.

3.2.1. Ambiguity: Frog Story

Since there was no data available for High-A referents in the Frog narrative, we only analyzed the Low-A referents, so no comparisons were made between the different accessibility contexts.

Table 6.

The mean percentage of referring expressions used in contexts with single and multiple characters by bilinguals and monolinguals (Frog) (frequency in parenthesis).

Table 6.

The mean percentage of referring expressions used in contexts with single and multiple characters by bilinguals and monolinguals (Frog) (frequency in parenthesis).

| Bilinguals (BI) (n = 13) | Monolinguals (MO) (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | |

| Single (High-A) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Multiple | 72.4% | 27.6% | 100% | 53.3% | 46.7% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (217) | (72) | (6) | (295) | (69) | (54) | (0) | (123) |

Note. High-A = high accessibility values, Low-A = low accessibility values. No data for High-A.

Figure 4.

Mean percentage of referring expressions used in contexts with multiple characters by bilinguals and monolinguals (Frog).

Bilinguals and monolinguals displayed different patterns in their referential choice. Bilinguals used more NPs and fewer combined null forms and pronouns (72.4% vs. 27.6%) compared to their monolingual peers, whose use of both forms was roughly equally distributed (53.3% vs. 46.7%). Thus, bilinguals showed a strong preference for explicit forms when disambiguation was required.

We examined the effect of group on the outcome variable by comparing a null model with a full model that included the main effect of group. The full model showed a significantly better fit (Χ2 = 5.616, p = 0.01780); that is, monolinguals and bilinguals behave differently. The GLM analysis demonstrates that group significantly impacts referential choice (p = 0.02097): monolinguals use significantly fewer NPs (negative estimate) than bilinguals.

Table 7.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Ambiguity (Frog).

Table 7.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Ambiguity (Frog).

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.307 | 0.070 | −4.405 | 1.058 × 10−5 |

| GroupB | −0.325 | 0.141 | −2.309 | 2.097 × 10−2 |

3.2.2. Ambiguity: Chaplin Story

For the Chaplin story, within High-A referents (contexts with a single character), we observed that null forms prevailed in both the bilingual and monolingual data, accounting for 66.5% and 84.8%, respectively. That is, both bilinguals and monolinguals exhibited a similar tendency when the referent was easily retrievable. For Low-A referents (contexts with multiple competing characters), the findings revealed a comparable tendency to the Frog story: Bilinguals used more NPs and fewer null forms (57.6% vs. 42.4%) compared to monolingual children, who did not show a strong preference for either form (46.5% vs. 53.5%). The data seem to suggest that bilinguals preferred explicit forms (NPs) when disambiguation was required, whereas monolinguals did not exhibit such a preference.

A comparison of High- and Low-A referents in both bilinguals and monolinguals showed that individuals from both groups were attuned to the two distinct discourse conditions, employing more null forms when no competing characters were present. The data thus revealed that both bilinguals and monolinguals seem to differentiate different levels of accessibility (Table 8).

Table 8.

The mean percentage of referring expressions used in contexts with single and multiple characters by bilinguals and monolinguals (Chaplin) (frequency in parenthesis).

Table 8.

The mean percentage of referring expressions used in contexts with single and multiple characters by bilinguals and monolinguals (Chaplin) (frequency in parenthesis).

| Bilinguals (n = 11) | Monolinguals (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronouns | Total | NP | Null | Pronouns | Total | |

| Single | 33.5% | 66.5% | 100% | 15.2% | 84.8% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (16) | (26) | (1) | (43) | (5) | (27) | (1) | (33) |

| Multiple | 57.6% | 42.4% | 100% | 46.5% | 53.5% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (144) | (92) | (1) | (237) | (46) | (53) | (0) | (99) |

Note. High-A = high accessibility values, Low-A = low accessibility values.

Figure 5.

Relationship between the mean percentage of NPs and the number of competing characters used by bilinguals and monolinguals (Chaplin).

In order to evaluate the impact of group and accessibility on the dependent variable, we compared a null model with a full model that included the two main effects and their interaction. The full model did not provide a significantly better fit to the data (Χ2 = 4.528, p = 0.1039); that is, the differences in referential choice across different observations cannot be attributed to the group, accessibility and the interaction between the two. The GLM analysis demonstrates that neither group nor accessibility influence the tendency significantly (group: p = 0.4418, accessibility: p = 0.4066). Thus, although descriptive statistics suggest different tendencies in the two groups in different accessibility contexts, the statistical analysis demonstrates that neither accessibility (ambiguity) nor group had a significant effect on the use of NPs (Table 9).

Table 9.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Ambiguity (Chaplin).

Table 9.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Ambiguity (Chaplin).

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.802 | 0.277 | −2.893 | 3.817 × 10−3 ** |

| GroupB | −0.296 | 0.385 | −0.769 | 4.418 × 10−1 |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.243 | 0.292 | 0.830 | 4.066 × 10−1 |

Note. ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, + = p < 0.1

3.3. Predictability

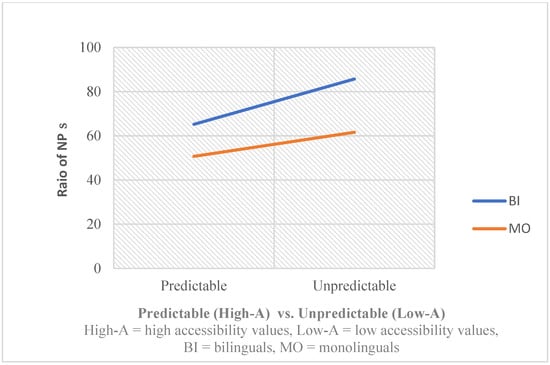

Table 10 and Table 12 list the mean percentages of referring expressions used in pragmatically predictable and unpredictable contexts by bilinguals and monolinguals in the Frog and Chaplin narratives, respectively. Figure 6 provides a graphical representation of Table 10, while Figure 7 similarly presents a graphical representation of Table 12. Additionally, pronouns and null forms were combined for the statistical analysis. Table 11 and Table 13 are the results of the GLM analysis for the Frog and the Chaplin data, respectively.

3.3.1. Predictability: Frog Story

In the predictable context (High-A), bilinguals and monolinguals showed different tendencies in the distribution of referential forms. While bilinguals used far more NPs compared to null forms (65.2% vs. 34.8%), NPs and null forms were equally distributed in the monolingual data (50.7% vs. 49.3%). In the unpredictable context (Low-A), however, both groups preferred selecting NPs (85.7% vs. 14.3% in bilinguals and 61.6% vs. 38.4% in monolinguals). The data thus suggest that bilinguals appeared to show a stronger preference for the use of NPs in both contexts. When comparing the High-A (predictable) and Low-A (unpredictable) contexts in each group, both bilinguals and monolinguals appeared to use more NPs in the Low-A context as compared to High-A context (65.2% vs. 85.7% in bilinguals and 50.7 vs. 61.6% in monolinguals). In other words, both groups of children seem to have responded to both High-A and Low-A referents.

Table 10.

The mean percentage of referring expressions used in pragmatically predictable and unpredictable contexts by bilinguals and monolinguals (Frog) (frequency in parenthesis).

Table 10.

The mean percentage of referring expressions used in pragmatically predictable and unpredictable contexts by bilinguals and monolinguals (Frog) (frequency in parenthesis).

| Bilinguals (n = 13) | Monolinguals (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | |

| Predictable | 65.2% | 34.8% | 100% | 50.7% | 49.3% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (131) | (64) | (3) | (198) | (49) | (43) | (0) | (92) |

| Unpredictable | 85.7% | 14.3% | 100% | 61.6% | 38.4% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (91) | (11) | (3) | (105) | (20) | (13) | (0) | (33) |

Note. High-A = high accessibility values, Low-A = low accessibility values.

Figure 6.

Relationship between the mean percentage of NPs and pragmatic predictability used by bilinguals and monolinguals (Frog).

The effect of group and accessibility on the outcome variable was examined by comparing a null model with a full model that included the two main effects and their combined effect. The full model showed a significantly better fit (Χ2 = 9.260, p = 0.02603, p < 0.05); that is, group (bilinguals vs. monolinguals), accessibility (high vs. low), and the interaction between the two account for the differences in NP use across different observations. The GLM analysis demonstrates that there is a significant group effect: monolinguals are less likely (negative estimate) to use NPs than bilinguals (p = 0.04058). The effect of accessibility on NP use is not statistically significant (p = 0.1768), neither was the interaction between group and accessibility (p = 0.8851). Thus, the data suggests that there is no effect of accessibility on group: monolinguals use fewer NPs regardless of accessibility.

Table 11.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Predictability (Frog).

Table 11.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Predictability (Frog).

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.366 | 0.091 | −4.048 | 5.172 × 10−5 *** |

| GroupB | −0.377 | 0.184 | −2.048 | 4.058 × 10−2 * |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.197 | 0.146 | 1.351 | 1.768 × 10−1 |

| GroupB × AccessibilityLow | 0.045 | 0.311 | 0.144 | 8.851 × 10−1 |

Note. ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, + = p < 0.1.

3.3.2. Predictability: Chaplin Story

Within the High-A referents (predictable), the two groups exhibited different tendencies. NPs and reduced forms (null and pronouns) were equally distributed in the bilingual data (46.5% vs. 53.5%), whereas the monolingual data revealed a skewed distribution toward the use of reduced forms (26.9% vs. 73.1%). Unlike monolinguals, bilinguals did not prefer null forms in High-A contexts. In Low-A contexts, where the referent was unpredictable, the Chaplin data revealed a similar trend to the Frog data. As illustrated in Table 12, both groups displayed nearly the same distribution; specifically, NPs primarily dominated the referring expressions (78.1% vs. 21.9% in bilinguals, 78.7% vs. 21.3% in monolinguals). Thus, we found that both groups of children predominantly used NPs when the referent was not easily retrievable.

The two sets of data also reveal that both bilinguals and monolinguals were sensitive to different levels of predictability, showing a prominent difference in referential choice patterns. The balance among the different forms changed drastically between the referents with high and low accessibility (49.5% vs. 78.6% NP use in bilinguals, 25.6% vs. 76.0% in monolinguals).

Table 12.

The mean percentage of referring expressions used in pragmatically predictable and unpredictable contexts by bilinguals and monolinguals (Chaplin) (frequency in parenthesis).

Table 12.

The mean percentage of referring expressions used in pragmatically predictable and unpredictable contexts by bilinguals and monolinguals (Chaplin) (frequency in parenthesis).

| Bilinguals (n = 11) | Monolinguals (n = 7) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | NP | Null | Pronoun | Total | |

| Predictable | 46.5% | 53.5% | 100% | 26.9% | 73.1% | 100% | ||

| (High-A) | (108) | (109) | (1) | (218) | (24) | (74) | (0) | (98) |

| Unpredictable | 78.1% | 21.9% | 100% | 78.7% | 21.3% | 100% | ||

| (Low-A) | (55) | (13) | (2) | (70) | (28) | (8) | (1) | (37) |

Note. High-A = high accessibility values, Low-A = low accessibility values.

Figure 7.

Relationship between the mean percentage of NPs and pragmatic predictability used by bilinguals and monolinguals (Chaplin).

We compared a null model with a full model that included the two main effects and their interaction to examine the effect of group and accessibility on the outcome variable. The full model showed a significantly better fit (Χ2 = 22.551, p = 0.00005009); that is, group (bilinguals vs. monolinguals), accessibility (high vs. low), and the interaction between the two account for the differences in NP use across different observations. The GLM analysis demonstrates that there is a significant group effect: monolinguals are less likely (negative estimate) to use NPs than bilinguals (p = 0.0007144). The effect of accessibility on NP (p = 0.06612) as well as the interaction between group and accessibility show a weak significance (p = 0.05845). Thus, the statistical analysis suggests a marginal effect of accessibility on group: monolinguals are more likely to use NPs under low accessibility, meaning that they are more likely to be affected by accessibility (predictability) (Table 13).

Table 13.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Predictability (Chaplin).

Table 13.

Results of Generalized Linear Model (GLM) analysis: Predictability (Chaplin).

| Estimate | SE | z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.702 | 0.096 | −7.299 | 2.895 × 10−13 *** |

| GroupB | −0.807 | 0.238 | −3.384 | 7.144 × 10−4 *** |

| AccessibilityLow | 0.415 | 0.226 | 1.838 | 6.612 × 10−2 *+ |

| GroupB × AccessibilityLow | 0.807 | 0.426 | 1.892 | 5.845 × 10−2 + |

Note. ** = p < 0.01, * = p < 0.05, + = p < 0.1

3.4. Individual Analysis

Since the sample size was small for both bilinguals and monolinguals, we examined individual data to see if each group of participants aligned with the overall tendency reported above. Analysis confirmed that overall the referential choice pattern of each participant aligned with the overall tendency reported, although in some contexts variations were observed. In terms of recency, there were two cases where more variation was observed: in the monolingual High-A referents in the Frog story, half of the children used more null forms than NPs while the other half used the two forms equally; in the bilingual High-A referents in the Chaplin narrative, half of the children preferred NPs while the other half preferred null forms. As for ambiguity, two cases were identified: in the monolingual Low-A referents in the Frog story, half of the children preferred NPs while the rest preferred null forms; for bilingual Low-A referents in the Chaplin narrative, the preference was again divided. Regarding predictability, variation was found in two cases: in the monolingual High-A referents in the Frog story, the data was divided, where half of the participants preferred null forms and the rest either preferred NPs or used both equally; in bilingual High-A referents in the Chaplin data, the same pattern was observed. However, no strong variation was observed between the High- and Low-A comparison in each individual; most children preferred explicit forms to reduced forms for Low-A referents.

4. Discussion

This study examined the accessibility features that influence the previously identified differences in reference choice between bilinguals and monolinguals in the context of reintroduction. It also explored whether the frequent use of noun phrases (NPs) in bilingual speech is truly “redundant”, i.e., concentrated in High-A referents.

4.1. Accessibility Features and Bilingual–Monolingual Differences in Referential Choice

From the bilingual–monolingual comparison, we found that bilinguals tended to use more NPs compared to monolinguals across all three features. The excessive use of NPs was noted under various accessibility values. Regarding recency, bilinguals preferred overt forms compared to monolinguals when the referent was highly accessible. Conversely, both groups predominantly employed overt forms when the referent was less accessible. We found a marginal combined effect of group and accessibility, meaning that monolinguals were more likely to use NPs in Low-A context. A similar tendency was observed for predictability although only in the Chaplin data. Overall, our data indicates that referential choices for both bilinguals and monolinguals are somewhat influenced by the accessibility principle, leading to the greater use of overt forms for referents with low accessibility and less overt forms for those with high accessibility. Nonetheless, monolinguals demonstrated a stronger inclination to use overt forms when the referent was less accessible, whereas bilinguals were less likely to be impacted by accessibility.

On the other hand, regarding ambiguity, different tendency was observed. Bilinguals appeared to prefer overt forms more than monolinguals when the referents were low in accessibility while both groups of children used null forms when the referents were highly accessible, although statistical analysis did not support the effect of group nor accessibility. However, it should be noted that there is a possibility that bilingual, but not monolingual, speakers adhere to the universal principle of accessibility by using more NPs with less accessible referents, whereas monolingual speakers do not necessarily exhibit this tendency. The bilingual data were comparable to the narratives of English-speaking children by (). One could argue that bilinguals’ referential choice of less accessible referents may not be overexplicit but informative; the overt forms can assist listeners in disambiguating the multiple referents in the discourse.

It is worth mentioning that the narratives of Japanese monolinguals did not exhibit strong sensitivity to ambiguity: in both Frog and Chaplin data, bilinguals’ referential choice was skewed to NPs in Low-A context whereas monolinguals did not strongly prefer overt form. The phenomena may align with the argument that monolingual Japanese speakers tend to have a high tolerance to potential ambiguity (; ). It could be argued that for Japanese speakers, explicit arguments for disambiguation are less important than in other languages such as English because referents are far more likely to be left unmentioned and thus are more often inferred from verb semantics, whereas in English, although verb semantics may also play a role, most arguments are in overt forms that can serve as clues for retrieval of the referent. Speakers trust that the listener will understand the referent in a given discourse context unless there is strong evidence to believe otherwise; therefore, they do not differentiate contexts with single vs. multiple referents. Another possibility may be that the monolingual children were yet to reach the adult norm, as discussed in Section 1.2, in which the choice is regulated by accessibility features. Considering the fact that more than half of the monolingual participants were 11 years or younger, they may have still relied on the topicality of the referent and thus did not attempt to disambiguate it (expected the listeners to infer the referent based on the story line).

4.2. How Can Bilinguals’ Overproduction Be Accounted for?

In carefully analyzing the referential choices of bilinguals and monolinguals in different accessibility contexts, we found that bilinguals were not consistently overexplicit or redundant across varying accessibility features: bilinguals’ referential choice was in most cases affected by the level of accessibility. Our results may challenge the claim that overproduction arises from the burden of integrating syntactic and pragmatic information from two languages, which is supposed to be more cognitively demanding than monolingual communication processing (e.g., ). Let us assume that the overproduction is due to the higher cognitive load caused by integrating the different levels of information from the two languages. In this case, they would have to be consistently overproductive in all discourse contexts, and adaptation between different levels of accessibility would be less likely to occur. Our findings indicate that bilinguals do not necessarily find it more challenging to integrate syntactic and pragmatic information. In some contexts, they show a greater responsiveness to accessibility, enabling them to combine multiple levels of information effectively.

From the above analysis, we conclude that bilinguals’ greater use of NPs is likely influenced by English, which, in principle, does not allow null referents and generally employs pronouns in similar discourse contexts. Since there are, in principle, no pronouns as grammatical substitutes for NPs in Japanese (see Section 1.5), NPs represent the most natural form for them to use. Our data lend support to the previous findings regarding cross-linguistic influence on the choice of reference forms among young and older bilinguals learning English alongside a null argument language (see Section 1.4).

We could further conjecture that what is being transferred from English to Japanese is the syntactic expectation from English that referents are to be made explicit. As was argued in Section 4.1, ellipsis in Japanese is not an omission of a necessary argument but a result of that which is unexpressed being inferable from verb semantics and other cues in the discourse context. Therefore, monolingual children have developed a high tolerance toward the ambiguity of referents due to the nature of the language and everyday interaction among Japanese speakers. On the other hand, bilingual children who have acquired English together with Japanese have been accustomed to making explicit what is being communicated, and that style strongly influences them. Furthermore, because the participants are school-age children, our findings may corroborate the idea put forth by (), who argues that children need to learn to be explicit—they start with a predominant use of ellipsis at preschool age and gradually learn that explicit forms may be helpful in some contexts after school age. If this is the case, we can speculate that the use of explicit forms in necessary contexts (for disambiguation) was still underdeveloped among monolingual children, whereas bilinguals who know English may have acquired this earlier. This may align with the idea of acceleration through CLI (), which is worth further investigation.

Another possible interpretation is that bilinguals use explicit communication strategies. The fact that the referential choice of bilinguals can sometimes be informative corroborates the idea that it may be interpreted as a “clarity-based strategy” (), which refers to bilinguals’ tendency to employ the more explicit option as a communication strategy to secure topic continuity and avoid communication breakdowns. This interpretation is also consistent with (), who hypothesizes that bilinguals have a higher and stricter standard/threshold for determining the informativeness of the referent when they speak in null argument language and carefully track the referent in more overt forms to avoid ambiguity in storytelling. While the monolingual Japanese children in our data tended to assume that the referent was still active in the listener’s mind even after some gaps in the reference or that it could be fully inferred from the semantics of the verb, namely, they relied more on the pragmatic context for the listener to understand the referent correctly, bilingual children constantly paid attention to the referent being explicitly mentioned and assuredly informative to avoid misunderstanding.

Our findings, however, should be interpreted with caution due to several methodological limitations. First, the small number of participants limited the validity of our arguments. In addition, the age range of participants (from 8 to 13 years) may have meant that the study included a mixture of children at different stages of development. Although both groups of participants were somewhat distributed in a similar manner among the age range, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results as there were more bilinguals in the older age range, as mentioned in Section 2.1. It would be ideal to supplement the data for each age group to analyze whether there are differences between the different developmental stages. It should also be noted that examining the reference choices of bilinguals learning Japanese and another null argument language would help to filter out the effects of CLI and other factors. Furthermore, consideration must be given to the possibility that speakers of different languages may respond to certain accessibility features differently, meaning that the results of the bilingual–monolingual comparison can vary depending on the analyzed language pairs. Combining the two sets of data (Frog and Chaplin) would have increased the statistical power of our data. However, we analyzed them separately as they were not identical in terms of the story content or elicitation style (book vs. video), and referential choice in certain contexts was sensitive to these factors.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated how various accessibility features (recency, ambiguity, and predictability) influence referential choice in the Japanese narratives of Japanese–English school-age bilinguals and monolinguals within a reintroduction context, and whether the overexplicitness observed in bilingual narratives stems from the influence of English. We found that bilinguals, like their monolingual counterparts, adjust their choices based on different levels of accessibility and are selectively overexplicit; that is, the use of NPs may not be attributed to the processing burdens related to information integration but rather is shaped by their knowledge of English as modulated by accessibility features.

Our findings enhance the understanding of CLI and overexplicitness in bilingual speech by emphasizing the importance of a discourse-pragmatic approach for analyzing explicitness in bilingual children’s referential choices. We discovered that bilingual children are sensitive to accessibility features. The findings provide a new perspective on the current model of bilingual cognitive processing, suggesting a more intricate process involving accessibility.

The current data also contribute to the understanding of narrative development, showing that both bilingual and monolingual children are sensitive to accessibility features in their elicited narratives, even during the context of reintroduction. Although decontextualized narratives are assumed to require higher sensitivity to the listener’s perspective, by school age, both bilingual and monolingual children can adjust their referential forms by taking the listener’s perspective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.-M., Y.J.Y., and Y.N., methodology, S.M.-M., Y.J.Y., and Y.N., formal analysis, S.M.-M. and Y.N., writing—original draft and preparation, S.M.-M., writing—review and editing, Y.J.Y., and Y.N., funding acquisition, S.M.-M. and Y.J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, author-ship and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI grant number [16K02701] awarded to the first and the third author. APC was funded by Rikkyo University Personal Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was authorized by the Institutional Review Board of the Graduate School of Intercultural Communication, Rikkyo University (2023-07, 30 May 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available at https://osf.io/c3vfz/overview?view_only=06fff1b4902b42fa86b08614d88bc363 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere thanks to the children and their parents for kindly participating in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Two more monolingual children participated, but the data was excluded since they told a first-person narrative, referring to the main character as boku ‘I”. |

| 2 | SI refers to the number of clauses per the number of T-units (). |

References

- Adam, C. (Director). (2012). Chaplin and co (The Museum Guard) [Video]. Anderson Digital. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, M. (2020). The effects of updating and proficiency on overspecification in American Greek children. European Journal of Psychological Research, 7(1), 26–32. Available online: https://www.idpublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Full-Paper-THE-EFFECTS-OF-UPDATING-AND-PROFICIENCY-ON-OVERSPECIFICATION-IN-AMERICAN-GREEK-CHILDREN.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Andreou, M., Torregrossa, J., & Bongartz, C. (2023). The use of null subjects by Greek-Italian bilingual children: Identifying cross-linguistic effects. In G. Fotiadou, & I. M. Tsimpli (Eds.), Individual differences in anaphora resolution: Language and cognitive effects (pp. 166–191). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, M., Torregrossa, J., & Bongartz, C. M. (2020). The sharing of reference strategies across two languages: The production and comprehension of referring expressions by Greek-Italian bilingual children. Discours. Revue de Linguistique, Psycholinguistique et Informatique. A Journal of Linguistics, Psycholinguistics and Computational Linguistics, [online], 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyri, E., & Sorace, A. (2007). Cross-linguistic influence and language dominance in older bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 10(1), 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, M. (1990). Accessing noun-phrase antecedents (RLE Linguistics B: Grammar). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, J. E. (2010). How speakers refer: The role of accessibility. Language and Linguistics Compass, 4(4), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J. E., Bennetto, L., & Diehl, J. J. (2009). Reference production in young speakers with and without autism: Effects of discourse status and processing constraints. Cognition, 110(2), 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, J. E., & Griffin, Z. M. (2007). The effect of additional characters on choice of referring expression: Everyone counts. Journal of Memory and Language, 56(4), 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, M. G. (1987). The acquisition of narratives: Learning to use language. Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsong, D., Gertken, L. M., & Amengual, M. (2012). Bilingual language profile: An easy-to-use instrument to assess bilingualism. COERLL, University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://blp.coerll.utexas.edu (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Bock, J. K., & Warren, R. K. (1985). Conceptual accessibility and syntactic structure in sentence formulation. Cognition, 21(1), 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L., & Cheek, E. (2017). Gender identity in a second language: The use of first person pronouns by male learners of Japanese. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 16(2), 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chafe, W. (1976). Givenness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics and point of view. In C. N. Li (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 25–56). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chafe, W. (1994). Discourse, consciousness, and time: The flow and displacement of conscious experience in speaking and writing. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., & Lei, J. (2012). The production of referring expressions in oral narratives of Chinese–English bilingual speakers and monolingual peers. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 29(1), 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, P. M. (1992). Referential strategies in the narratives of Japanese children. Discourse Processes, 15(4), 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, P. M. (1997). Discourse motivations for referential choice in Korean acquisition. In H. M. Sohn, & J. Haig (Eds.), Japanese/Korean linguistics 6 (pp. 639–659). CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Colozzo, P., & Whitely, C. (2014). Keeping track of characters: Factors affecting referential adequacy in children’s narratives. First Language, 34(2), 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daller, M. H., Treffers-Daller, J., & Furman, R. (2011). Transfer of conceptualization patterns in bilinguals: The construal of motion events in Turkish and German. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 14(1), 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, B., & Housen, T. (2017). A cross-linguistic perspective on syntactic complexity in L2 development: Syntactic elaboration and diversity. The Modern Language Journal, 101, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bois, J. W. (1987). The discourse basis of ergativity. Language, 63(4), 805–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillmore, C. J. (1982). Frame semantics. In Linguistic Society of Korea (Ed.), Linguistics in the morning calm (pp. 111–138). Hanshin Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gagarina, N., & Bohnacker, U. (2022). A new perspective on referentiality in elicited narratives: Introduction to the special issue. First Language, 42(2), 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givón, T. (1983). Topic continuity in discourse: An introduction. In Topic continuity in discourse: A quantitative cross-language study (pp. 1–41). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Gundel, J. K., Hedberg, N., & Zacharski, R. (1993). Cognitive status and the form of referring expressions in discourse. Language, 69(2), 274–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haznedar, B. (2010). Transfer at the syntax-pragmatics interface: Pronominal subjects in bilingual Turkish. Second Language Research, 26(3), 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, M. (2003). Children’s discourse: Person, space, and time across languages. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hickmann, M., & Hendriks, H. (1999). Cohesion and anaphora in children’s narratives: A comparison of English, French, German, and Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Child Language, 26(2), 419–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickmann, M., Hendriks, H., Roland, F., & Liang, J. (1996). The marking of new information in children’s narratives: A comparison of English, French, German and Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Child Language, 23(3), 591–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, M., Schimke, S., & Colonna, S. (2015). From early to late mastery of reference: Multifunctionality and linguistic diversity. In L. Serratrice, & S. E. M. Allen (Eds.), The acquisition of reference (pp. 181–211). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, J. (1983). Topic continuity in Japanese. In T. Givón (Ed.), Topic continuity in discourse: A quantitative cross-language study (pp. 43–93). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M. E., & Allen, S. E. (2013). The effect of individual discourse-pragmatic features on referential choice in child English. Journal of Pragmatics, 56, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashita, N. (2006). Syntactic complexity measures and their relation to oral proficiency in Japanese as a foreign language. Language Assessment Quarterly: An International Journal, 3, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1985). Language and cognitive processes from a developmental perspective. Language and Cognitive Processes, 1(1), 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]