Abstract

An important line of research within a generative, formal approach to syntax in the early 21st century has centered on exploring phenomena related to the interface between syntax and other linguistic modules in human language. In this paper, we review the notion of interfaces and how they have been viewed within formal theoretical approaches to monolingual and bilignual competence and language acquistion, noting their relevance as they relate to language acquisition and bilingualism in the context of Galicia (Spain). We review a selection of Noun Phrase (NP) structures that implicate a syntactic interface: subject position, clitic directionality, and determiner clitic allomorphy. We provide a review of the relevant literature and the theoretical issues of interest as they relate to our understanding of these syntactic interfaces, reporting on our current theoretical understandings, persistent questions, and our view of the path forward as it relates to linguistic research on the Galician language.

1. Linguistic Interfaces in the Generative Literature

In the 21st century, an important line of research within a generative, formal approach to syntax has centered on exploring phenomena related to the interface between syntax and other linguistic modules in human language. In this paper, we review a selection of syntactic structures involving the Noun Phrase (NP) in Galician, all of which implicate a syntactic interface. We attempt to illustrate the insight that a formal syntactic analysis can offer on structures unique to Galician and how those may be modeled within the bilingual grammar. We start with a review of the notion of interfaces and how they have been viewed within formal theoretical approaches (e.g., Reinhart 2006; López 2009), as well as within formal approaches to bilingual acquisition (e.g., Sorace 2011; White 2011). We note the particular relevance these are understood to have for language competence in Galicia (e.g., Pérez-Pereira 2007) as well as potential cross-linguistic interference of the type discussed in previous work on Galician bilinguals (e.g., Álvarez-Cáccamo 1983; Dubert García 2005; Ramallo 2007). Given the relative scarcity on such research in Galician, we also offer a brief discussion of relevant research on Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian speakers. We then examine two specific interface phenomena in the syntax: the importance of clitics to the preverbal field and clitic determiners within the Noun Phrase (NP). In the following, we review the relevant literature, indicating theoretical issues of interest as they relate to our understanding of the syntactic interfaces. We report on current theoretical understandings, lingering questions, and our view of the future as it relates to linguistic research on selected syntactic interfaces in the Galician language.

First, we examine the implications for our understanding of the syntactic left periphery in Galician. For preverbal constituents, we sketch out an analysis of the interaction between preverbal subject positions in Galician and their associated clitic directionality, offering critical refinements to extant analyses. We examine these structures assuming a dedicated functional syntactic position for clitics of the type originally proposed in Uriagereka (1995a) and improved upon in Raposo and Uriagereka (2005) and Gupton (2010, 2012, 2014a). Here, we examine novel introspective judgments gathered from Galician-speaking informants, but reference will also be made to experimental Galician data reported in Gupton (2010, 2014a, 2014b, 2017) and Gupton and Leal-Méndez (2013), noting how the data inform our understanding of the basic clausal structure of Galician as a predominantly SVO language. We highlight the importance of this proposal for the analysis of the preverbal field in Galician, but also its importance for crosslinguistic analysis with other structurally similar Iberian Romance languages such as Castilian Spanish, European Portuguese, Asturian, and Catalan within a microparametric approach (e.g., Kayne 2005; Lardiere 2009). We close with a review of the accounts proposed, as well as recommendations for further investigation within the formal theoretical paradigm, with particular interest in applying the novel experimental methodology in Cruschina and Mayol (2022) to improve and expand upon the findings reported in Gupton (2010, 2014a), which tested the explanatory value of two particular syntax-information structure interface proposals for Galician, namely Zubizarreta (1998) for Romance and Germanic languages, and López (2009) for Spanish and Catalan.

Additionally, we delve into work on the NP in Galician and the interfaces concerning the syntax, morphology, and phonology at play in these structures. We address what Uriagereka (1995a, 1996) labels ‘determiner clitics’ owing to the similarity between articles and clitic pronouns in Galician. We show that the phonological alternations examined are predicated on a particular syntactic relation, pace recent claims in Kastner (2024) that posit this surface-level allomorphy as simply a case of resyllabification. We build on the work in Gravely and Gupton (2020), paying particular attention to the underlying syntactic structures that do or do not feed allomorphy at both the morphological and phonological level. Although Galician is rich in dialectal variation with respect to these phonological alternations (-o, -lo, -no; cf. Dubert García 2014, 2016 and references therein), a fact that has important implications for studies of intergenerational language change (Gravely 2021a) and microparameterization (e.g., Kayne 2005), we focus on the syntactic constraints required in order for the aforementioned phonological alternations (and cliticization more generally) to arise, namely that of categorial selection and head-to-head relations.

1.1. Formal Notions of the Interfaces

Chomsky (2007) describes the interfaces as the points of contact between the computational system of human language and two critical language modules: articulatory-perceptual systems (speech production) and conceptual-intentional systems (thought, meaning, and the lexicon). This model is often conceived of in the guise of the inverted-Y model (1), as in e.g., Irurtzun (2009):

| (1) | lexicon | |

| ||

| syntax | ||

| ||

| phonological form (PF) | logical form (LF) | |

| (articulatory-perceptual system) | (conceptual-intentional system) | |

In this particular model, the articulatory-perceptual system is expanded to include speech perception. The computational system is viewed as an individual, generative grammar (I-grammar) that assembles items from the lexicon endowed with abstract semantic and formal features and functional features recursively in the syntax in an operation called merge until the lexical array is exhausted. Importantly, according to this proposal, all uninterpretable features must be deleted prior to the interface. The by-product of this process is that utterances produced by derivations that successfully value lexical/functional features form the set of possible sentences in a particular language. This grammatical configuration results from continued childhood exposure to the ambient linguistic input. Reinhart (2006) refines this view, further dividing the conceptual-intentional system into context and inference, given that in her examination of four interface phenomena, these are foundational in reference-set computation.1 Reinhart examines evidence from the first language acquisition of English showing that children experience delays in reference-set computation compared to adult speakers. Consider, for example, experimental sentences from research on Principle B effects by Chien and Wexler (1990):

| (2) | a. | Kittyi says that Sarahj should point to herself*i/j/*k. |

| b. | Kittyi says that Sarahj should point to heri/*j/k. |

According to Principle A of Chomsky’s Government and Binding theory (e.g., Chomsky 1981), anaphoric expressions like herself in (2a) must be locally bound, meaning that reflexive pronouns like herself (2a) that must refer to an antecedent have to find the source of their reference in a structurally closer position—typically within the same clause—than referential object pronouns like her (2b) do. The result of this is that herself can only refer to Sarah. According to Principle B, pronouns may not be locally bound, thus ruling out the interpretation of her in (2b) as Sarah. Chien and Wexler’s (1990) results show that young children under 5 to 6 years of age successfully acquire the syntactic constraints on pronouns, evidenced via adult-like interpretation of Principle A effects, but experience difficulties in certain situations requiring pragmatic knowledge. Questions of this type were designed to target linguistic competence related to Principle B. In this task, children were presented with brief scene-setting sentences followed by questions like (3), which were accompanied by illustrations either showing Mama Bear touching Goldilocks or Mama Bear touching herself.

| (3) | This is Mama Bear; this is Goldilocks. Is Mama Bear touching her? |

In response to the context in which Mama Bear was touching herself and not touching Goldilocks, children 5–6 years of age responded at chance levels, in that they continued to allow referential pronouns like her to be interpreted reflexively.2 Grodzinsky and Reinhart (1993) attribute this to a delay in acquiring a pragmatic principle determining possible pronoun reference. Reinhart (2006) considers additional examples finding similar issues related to stress-shift, focus calculation, and the interpretation of scalar implicatures in English, all of which are attributed to delays in the development of systems governing reference-set computation.

At first blush, 5–6 years of age may seem to be rather late for children to be experiencing delays related to interface phenomena. However, Blake (1983) found that children acquiring L1 Spanish did not fully acquire the subtler uses of the subjunctive mood until adolescence, particularly those that involved the codification of what Blake labels doubt (4a) and attitudinal comment (4b):

| (4) | a. | Dudo | que | lo | sepa | |||||

| doubt.prs.1sg | comp | cl.acc.m.sg | know.prs.sbjv.3sg | |||||||

| ‘I doubt that s/he knows it.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | No | me | gusta | que | lo | sepa | ||||

| neg | cl.dat.1sg | please.prs.3sg | comp | cl.acc.m.sg | prs.sbjv.3sg | |||||

| ‘I don’t like that s/he knows that.’ | ||||||||||

Note that the sentences in (4) involve the mental states of others, a concept that requires the development of The Theory of Mind (Premack and Woodruff 1978), which according to Mayes and Cohen (1996) develops in children between the ages of 4 and 6. Despite the fact that sentences like the examples in (4) require a more developed mind, once this development is complete, acquisition of the subjunctive-mood contexts like these may proceed. In this case, the mental states of others is what invokes subjunctive mood in a fairly categorical manner. However, not all subjunctive-mood contexts are uniform or categorical. Consider (5), from Borgonovo et al. (2015, p. 35):

| (5) | Busco | unas | tijeras | que | cortan | / | corten | alambre |

| look.for.prs.1sg | some | scissors | comp | cut.prs.3pl/ | cut.prs.sbjv.3pl | wire | ||

| ‘I’m looking for some scissors that cut wire.’ | ||||||||

The sentence in (5) is acceptable with indicative mood under the definite meaning that can be assigned by the indefinite article unas (‘some’) such that the scissors in question already exist in the real world as the speaker knows it, but she simply cannot find them. The meaning corresponding to the subjunctive mood, however, is one in which the speaker has not yet found such a pair of scissors—and may not know for sure if such scissors exist. These examples demonstrate that mood selection corresponds with distinct possible states of affairs in the real world. These additional subtleties can further complicate and potentially delay the acquisitional task, in that it may initially suggest to the acquirer the presence of mood optionality. Therefore, from a probabilistic perspective, the individual who is acquiring subjunctive mood is now confronted with a more complex task, sorting through subjunctive mood triggers in the ambient data, identifying those that uniformly require the subjunctive and those that express different realities.3 The acquisition of mood variation is further complicated by the fact that the subjunctive exhibits geographical variation. Consider the following context from Bove’s (2018, p. 108) study on mood expression in Yucatec Spanish:

| (6) | Context: Estoy muy ocupada en mi trabajo y en mi vida personal, pero hay un puesto más avanzado que quiero solicitar en el trabajo. Cuando lo solicito, mi jefe me dice que no. Aunque, en mi opinión, puedo dedicar el tiempo necesario… | ||||||||||

| ‘I am very busy with my job and in my personal life, but there is a more advanced position that I want to apply for at work. When I apply for it, my boss says no. Although, in my opinion, I can dedicate the necessary time…’ | |||||||||||

| a. | Él | no | cree | que | yo | tengo | suficiente | tiempo | |||

| he | neg | think.prs.3sg | comp | I | have.prs.1sg | sufficient | time | ||||

| b. | Él | no | cree | que | yo | tenga | suficiente | tiempo | |||

| he | neg | think.prs.3sg | comp | I | have.prs.sbjv.1sg | sufficient | time | ||||

| ‘He does not think that I have enough time.’ | |||||||||||

Lacking context, the finite matrix epistemic verb form cree ‘(he) believes’ in the candidate responses should select a subjunctive-mood clausal complement, thus rendering response (6a) ungrammatical. However, Bove notes that, in this variety of Spanish—one that has been in contact with Yucatec Mayan for over 500 years—it is the veridicality of the subordinate-clause proposition within the context of the preceding discourse that determines the appropriate mood of the subordinate-clause predicate chosen. Within the context in (6), the speaker of the sequence believes that she has the requisite time, despite her boss’s opinion to the contrary. This is what allows speakers of Yucatec Spanish to prefer response (6a) to (6b).

The subjunctive mood in Spanish involves numerous points of interaction between the syntax and other modules of the grammar, invoking morphology, semantics, and pragmatics. Perhaps not surprisingly, it is difficult to acquire for monolinguals, bilinguals, and multilinguals. Points of interaction between modules are referred to as interfaces and have been of great interest to researchers of bilingualism and multilingualism over the past two decades. Research by Sorace and Filiaci (2006) proposed the Interface Hypothesis to capture the fact that extremely advanced, near-native second-language (L2) speakers of Italian exhibited instability related to the use of subject pronouns in Italian that required the consideration and reconciliation of pragmatic information, leading to performance that was not native-like and suggestive of residual optionality with respect to subject pronoun use. This is of relevance because the L1 of these speakers (i.e., English) is not a null-subject language, allowing only very limited uses of null subjects.

Studies on heritage speakers of null-subject languages who also know a non-null-subject like English have uncovered similar tendencies of interface instability among these speaker populations (e.g., Montrul 2005a, 2005b; Rothman 2007; Pires and Rothman 2009).4 Heritage speakers are defined as individuals who start life as monolingual speakers of a home language that differs from the majority language of a particular society, but subsequently become bilinguals who are proficient in the societal language—often as a result of compulsory, state-funded education programs—in addition to proficiency in their heritage language. Although the heritage language is very often an immigrant language this is not a strict requirement. Gupton (2010, 2014a) has explored whether speakers of a minority language like Galician may be considered to be heritage speakers of Galician, despite the fact that it is spoken by the majority of individuals in Galicia. The Galician Statistical Institute’s (IGE, Instituto Galego de Estatística) 2018 report of language usage, partially summarized in Table 1, suggests an extremely high level of bilingualism: roughly 75%.

Table 1.

Self-reported language use in Galicia (IGE 2018).

Bilingualism is widespread in Galicia, and involves a language with global presence (Spanish) in a situation of diglossia with a minority language (Galician) that was rarely used in public for approximately 500 years, dating from the post-Franco years back at least to the Irmandiño Wars (1467–1469) and the ensuing centralization of administrative power by the Catholic Monarchs, Fernando and Isabel.5 Given the asymmetric nature of Galician bilingualism, Gupton (2010, 2014a) suggests that speakers of Galician should be considered heritage speakers, with an important caveat. Given the reduced linguistic input that speakers may experience based on a dynamic combination of social factors, it may be that Galician speakers exhibit the same sort of instability that multilinguals do.6 Notwithstanding, the vast majority of Galician speakers are bilingual, with a vast range of dominance and usage patterns. The Spanish Ley Orgánica de Educación (Fundamental Law of Education) states that education within the Spanish state is free and compulsory from ages 6 to 16. For many children raised monolingually in Galician, the start of public schooling is their first point of contact with Castilian Spanish, where classes are taught in Spanish as well as Galician. Given that the majority of the population is literate (2.1% illiteracy rate in Galicia in 2001 according to IGE), an inevitable outcome of compulsory public schooling, it stands to reason that the only Galician monolinguals who would be monolingual, with extremely limited experience with Spanish, are those who do so intentionally, in essence, living off-grid administratively and linguistically. Therefore, Gupton (2014a) contends that a comparison of Galician–Spanish bilingual competence with some idealized Galician monolingual competence is unrealistic and unrepresentative of reality.7 It is worth noting, however, that Loureiro-Rodríguez (2009) found that her adolescent Galician informants admired rural vernacular speech for its authenticity, suggesting that non-standard rural Galician-dominant speech, in particular the type that is less influenced by contact with Castilian Spanish, exerts covert prestige. We consider bilingual competence among Galicians to be a valid representative of the Galician norm and a valuable source of data as well as syntactic theorizing, despite the potential for the presence of optionality at the interfaces.8

Given that the interfaces have been found to be problematic for bilinguals who may experience variable levels of input, we examine the formal analysis of two structures in Galician that invoke interfaces of the syntactic module of language with other modules, such as semantics, phonology, pragmatics, or information structure. First, however, we return to the view of the interface from the perspective of the syntax.

1.2. A Syntactic View of Interfaces

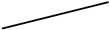

The current study is theoretically situated within a formal model of the grammar that emerged from the Government and Binding model (e.g., Chomsky 1981) of the syntax through to its current form, based on a Minimalist Program (e.g., Chomsky 1995 et sequens) that conceives of the grammar as a generative system of recursive merge, or a combination of syntactic objects, that acts on lexical items made up of formal features and functional features. The notion of multiple spell-out of the type proposed in e.g., Uriagereka (1999) marks a departure from the transformational grammar notion of syntactic movements taking place all at once to derive surface form from the underlying deep syntactic structure. These ideas figure into Phase Theory (e.g., Chomsky 2000, 2001), which views the edge of the syntactic projections vP and CP as points of derivational pause and partial spell-out. An example of an interface proposal incorporating phase theory is López (2009), which examines the syntax–information structural interface. Following his proposal, the Pragmatics component can inspect the syntactic structure at the vP phase edge in (7) and assign the Pragmatic feature [±a] (anaphoric). Later, at the CP phase edge, Pragmatics can assign a contrastive feature [±c].

Within this proposal, these [±a, ±c] features are strictly pragmatic, information structure-related features, and not lexical features. He combines these to derive a number of focus-dependent structures in Castilian Spanish and Catalan, including topical clitic left-dislocation (CLLD) and contrastive focus structures. The postulation of an independent Pragmatics module generating these features sidesteps potential problems for the Inclusiveness Condition (Chomsky 2000), which states that no new features can be introduced by the computational system, which would include the marking of syntactic objects in a derivation with diacritics related to e.g., topic or focus.9 Current views of syntax incorporating a Cartographic approach to the CP (e.g., Rizzi 1997, 2013) divide this realm into a number of specialized functional sub-projections, including Finiteness (FinP), Focus (FocP), Force (FceP), and, in some languages, recursive Topics (TopP*) appearing to the left or right of FocP. The structural hierarchy related to these positions appears in (8).

| (8) | FceP > TopP* > FocP > (TopP*) > FinP > TP > vP > VP |

Each of these functional projections is intended to capture a particular interface between the propositional content and its practical incorporation into the discourse-pragmatic context. Criterial features are proposed to exist related to these particular demands of speech, and others have been proposed to capture more finely-tuned subdivisions of topic type. Researchers like Frascarelli and Hinterhölzl (2007) have proposed these features for Italian and German, noting correspondences between intonation and information structure-related meanings in context found in corpora. Gupton (2021) analyzed experimentally-controlled data in Galician collected in voice recordings of Galician-dominant participants reading sentences preceded by a contextualized prompt to better construct the situations in which the sentences appear. Curiously, the results did not suggest specialized intonation curves by distinct information structure types in Galician, but they did reveal that constituents in the left or right peripheral positions exhibit a particular characteristic intonation: the left edge is marked by a post-tonic rise (L* + H), while the right edge is marked by a tonic fall (H + L*) or low tone (L%). This outcome suggests that marked syntactic positions are additionally—perhaps redundantly—marked prosodically in Galician, which may be a small first step in gaining insight into the characteristic prosody of Galicia that is often described as a sing-song intonation, and is found in Galician as well as Galician Spanish (e.g., Ramallo 2007).

Despite the fact that much generative theorizing has favored the view of the grammar from the perspective of an idealized monolingual, new models of bilingualism and multilingualism have appeared in recent years. López (2020) is a bold new model of code switching, based on a Minimalist view of syntax augmented by Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994, a.o.). Following this proposal, bilingual grammar consists of a single combined lexicon feeding into a single computational system in which the grammars of both languages coexist. This stands in opposition to the model proposed by MacSwan (1999, 2000), in which a bilingual has two separate lexicons that can feed into a single computational system (syntax), the output of which is sent to one of two dedicated PF output systems. It seems clear that there is still much for us to learn regarding the grammatical competence of bilinguals and multilinguals. The potential for cross-linguistic interference and/or potential residual optionality or instability related to the interface of the syntax with the phonology and the discourse (via information/focus structure) is precisely what attracts the attention of the syntactic researcher to the functional field and functional categories at the word level (NP-DP) and sentence level (CP).

As discussed previously above, studies on the acquisition of syntactic structures that differ in the mental grammar(s) of the bilingual are of particular interest to linguists, especially when (so-called) target production alternates with non-target production at the highest levels of proficiency. One particular structure that differs between Galician and Spanish is clitic directionality. Galician has split directionality, allowing finite enclisis in a variety of affirmative, declarative sentence types (9, more examples to follow below), but finite proclisis in main clauses in which a wh- element (10a), negation (10b), a negative quantifier (10c), a preverbal affective phrase (10d), or verum focus fronting (10e) precedes the verb.

| Galician | |||||||

| (9) | Xoán | (regalou=me | /*me | regalou | ) | un | libro. |

| Xoán | gift.prs.3sg=cl.dat.1sg | /cl.dat.1sg | gift.prs.3sg | a | book | ||

| ‘Xoán gave me a book.’ | (Gupton 2012, p. 274)10 | ||||||

| (10) | a. | A quen | (*Xoán) | (lle | debe | /*débe=lle) | (Xoán) o | aluguer? | |||||||||

| to who(m) (Xoán) | cl.dat.3sg | owe. prs.3sg | (Xoan) the | rent | |||||||||||||

| ‘To whom does Xoan owe rent?’ | (Gupton 2014b, p. 141)11 | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | Non | (o | fixen | /*fíxen=o). | |||||||||||||

| neg | cl.acc.3sg.m | do.pst.1sg | |||||||||||||||

| ‘I didn’t do it.’ | (Gupton 2014a, p. 205) | ||||||||||||||||

| c. | Nada | (lle | dixen | /*díxen=lle) | porque | nin | a | ||||||||||

| nothing | cl.dat.3sg | say.pst.1sg | because | neither | cl.acc.3sg.f | ||||||||||||

| lembrará. | |||||||||||||||||

| remember.fut.3sg | |||||||||||||||||

| ‘I told him nothing because he won’t remember anyway.’ | (Jaureguizar 2022) | ||||||||||||||||

| d. | Xoán | xa | (me | dixo | /*díxo=me) | o segredo. | |||||||||||

| Xoán | already | cl.dat.1sg | say.pst.3sg | the secret | |||||||||||||

| ‘Xoán already told me the secret.’ | (Gupton 2012, p. 274) | ||||||||||||||||

| e. | Algo | (lle | dixo | /*díxo=lle.) | |||||||||||||

| something | cl.dat.3sg | say.pst.3sg | |||||||||||||||

| ‘She told him something.’ | |||||||||||||||||

Castilian Spanish, however, does not have finite enclisis; rather, it has finite proclisis in main and subordinate clauses, as we can see in the Castilian analogues in (11). As we will see in (13) below, Spanish only allows enclisis with verbal infinitives.

| Castilian Spanish | ||||||||

| (11) | a. | A quién | (*Juan) | le | debe | (Juan) | el | alquiler? |

| to who(m) | (Juan) | cl.dat.3sg | owe. prs.3sg | (Juan) | the | rent | ||

| ‘To whom does Juan owe rent?’ | ||||||||

| b. | No | lo | hice. | |||||

| neg | cl.acc.3sg.m | do.pst.1sg | ||||||

| ‘I didn’t do it.’ | ||||||||

| c. | Nada | le | dije | porque | ni | la | ||

| nothing | cl.dat.3sg | say.pst.1sg | because | neither | cl.acc.3sg.f | |||

| recordará. | ||||||||

| remember.fut.3sg | ||||||||

| ‘I told him nothing because he won’t remember anyway.’ | ||||||||

| d. | Juan | ya | me | dijo | el | secreto. | ||

| Juan | already | cl.dat.1sg | say.pst.3sg | the | secret | |||

| ‘Xoán already told me the secret.’ | ||||||||

| e. | Algo | le | dijo. | |||||

| something | cl.dat.3sg | say.pst.3sg | ||||||

| ‘She told him something.’ | ||||||||

It is well documented (e.g., Dubert García 2005; Ramallo 2007; González González 2008; Enríquez-García 2017) that the difference in finite clitic directionality causes problems for Castilian Spanish–Galician bilinguals who acquire Galician in adulthood. Enríquez-García (2017) found that neofalante speakers of Galician overgenerated finite enclisis, leading to a large number of ungrammatical utterances. Another unique characteristic of Galician is that determiners exhibit behavior similar to object clitics, participating in unique phonological and syntactic dependencies within the Noun Phrase (NP).

| (12) | a. | Comemos | o | caldo | |||

| eat.prs.1pl | the | soup | |||||

| ‘We eat soup.’ | |||||||

| -> Come[mo.so.kal]do | |||||||

| -> Come[mo.lo.kal]do | |||||||

| b. | Son | boas | as | cancións | |||

| be.prs.3pl | good.f.pl | the.f.pl | songs.pl | ||||

| ‘The songs are good.’ | |||||||

| -> Son [bo.a.sas.kan]cións | |||||||

| ~> *Son [bo.a.las.kan]cións | |||||||

In (12a), there are two possible pronunciation options, one of which involves suppletion of a verb-final -s and a determiner immediately following. In (12b), however, we find that only one pronunciation is possible. If this were a simple phonological issue, we would not expect such an asymmetry in pronunciation, which strongly suggests that some sort of syntactic constraint is at play when the Noun Phrase as cancións syntactically merges with the rest of the clause in question. More specifically, this appears to involve the interface of the syntax module with the phonological module. It is worth noting that this sort of phonological phenomenon does not exist in any variety of Spanish that we know of. We are also unaware of any study on the acquisition of this characteristic of determiner clitics in Galician.

Clitic directionality and determiner clitic phonology are two notable differences between determiner systems in Castilian Spanish and Galician. Both involve a syntactic interface and both present data that might suggest to the L2 acquirer that optionality is at play, thus making them ideal structures to examine. Doing so will provide us with greater insight on the syntax of the Galician language, but its comparison with Spanish affords us an opportunity to identify how specifically these languages differ and how this is competence is represented in the grammar of the bilingual mind. In the following sections, we review the syntactic properties of determiner clitics at the word level and the clausal level in Galician, an enterprise that will allow us to identify the critical formal differences between the languages as well as potential points of difficulty and cross-linguistic interference. Before we do that, however, we want to contextualize the task at hand by briefly reviewing some of the relevant literature on the bilingual acquisition of clitic pronouns in Spanish and Galician.

Studies on the L2 acquisition of clitic pronouns in Spanish such as Duffield and White (1999) reveal that speakers of L1s like English that do not have clitic pronouns can acquire the syntactic properties of clitics in monoclausal sentences, but experience difficulty with biclausal sentences, given that some allow for restructuring (13a, b) for clitics, while others do not (14a, b).12

| (13) | a. | María | quiere | comprar=lo. | |

| Mary | want.prs.3sg | buy.inf=cl.acc.m.sg | |||

| ‘Mary wants to buy it.’ | |||||

| b. | María | lo | quiere | comprar. | |

| Mary | cl.acc.m.sg | want.prs.3sg | buy.inf | ||

| ‘Mary wants to buy it.’ | |||||

| (14) | a. | María | lo | hizo | caminar. |

| Mary | cl.acc.m.sg | make.pst.3sg | walk.inf | ||

| ‘Mary makes him walk.’ | |||||

| b. | *María | hizo | caminar=lo. | ||

| Mary | make.pst.3sg | walk.inf=cl.acc.m.sg | |||

The structure in (13a) is more similar to the English word order, and consequently this non-restructured order tends to be preferred for English L1 acquirers of L2 Spanish. This tendency causes problems for forms like (14a), which are not the product of restructuring of an underlying form like (14b).

Peace (2020) reveals that English L1 speakers tend to avoid use of Spanish L2 clitics when possible, using a tonic pronoun or omitting a clitic altogether. Although performance is largely native-like at advanced levels with accusative clitics, Peace (2020) found that instability persists in the use of dative clitics, which may have to do with the availability of dative clitic doubling in Spanish. Studies on the L2 acquisition of Italian clitics reviewed in Belletti and Guasti (2015) reveal similar results. They note that Leonini and Belletti (2004) found that their most advanced participants did not omit clitics, using them correctly 64% of the time, while opting for a tonic pronoun 30% of the time.

Smith et al. (2022), examined adult immigrant (AI) speakers of Italian living in Scotland and among heritage speakers (HS) of Italian raised in Scotland. This study focused on examining two markers of Developmental Language Disorder (DLD, Bishop 2017) among non-dominant speakers of Italian: repetition of nonce words and object clitic production. While the AI group was largely target-like (~80% accuracy), the HS group was less target-like (~35% accuracy) and exhibited a tendency to avoid clitic pronouns in production rather than to produce non-target structures. Curiously, previous studies (Arosio et al. 2014; Guasti et al. 2016) found that school-age children with DLD produce object pronouns more consistently and in a greater variety of structures than the HS participants in this study did. Results from the nonce-word repetition task, however, showed that the HS group performed similarly to the AI group, producing ~97% target-like responses. They note that this performance differs from research on DLD individuals (Bishop et al. 1996; Casalini et al. 2007; Conti-Ramsden 2003; Vernice et al. 2013), who have been found to experience difficulties with memory and phonological awareness.

Early bilingual acquirers of English and Spanish reported on in Pérez-Leroux et al. (2011) participated in an elicited repetition task and experienced difficulty with stimuli with clitic climbing sentences like (13b), with preverbal clitic pronouns. They attribute this behavior to cross-linguistic interference from English, which does not allow object pronouns to precede the verb. Heritage speakers of Spanish from Brazil who also spoke Brazilian Portuguese (BP), as reported in López Otero et al. (2023), experienced extended null objects from BP to their Spanish in situations that did not allow null clitics, such as (15).

| (15) | Nunca | pido | café, | pero | hoy | sí | pedí. |

| never | order.prs.1sg | coffee, | but | today | yes | order.pst.1sg | |

| ‘I never order coffee, but today I did.’ | (López Otero et al. 2023, p. 162) | ||||||

Studies on the L1 or L2 acquisition of Galician clitics are decidedly less numerous, but also are suggestive of learner difficulty with clitic directionality. Enríquez-García (2017) conducted sociolinguistic interviews with neofalante L2 speakers of Galician (L1 Castilian Spanish), and found that, in the resulting oral corpus, 19% of sentences produced diverged from the Galician norm with respect to clitic directionality.13 However, this number rose to 39% when considering only contexts where enclisis is predicted (Enríquez-García 2017, p. 57). Although this is one of the only studies that we are aware of on the L2 acquisition of clitic directionality in Galician, there are studies on structurally similar languages. Madeira and Xavier (2009) examined the L2 acquisition of split clitic directionality in European Portuguese (EP), which is very similar to Galician, among L1 speakers of Romance (French, Italian and Spanish) and Germanic languages (Danish, Dutch, English, and German), eliciting written production and grammaticality judgment data. On the written task, their participants displayed target-like written production of enclitic word orders from the earliest levels. Nevertheless, their participants produced obligatory proclitic word orders at chance levels among beginners. They also acknowledge that many L2 participants avoided using clitic pronouns or used tonic pronouns instead. On the grammaticality judgment task, participants showed indeterminate knowledge of the enclisis–proclisis split overall, but they performed better when judging grammatical sentences versus ungrammatical ones. Curiously, Costa et al. (2015) report that native EP-acquiring children experience target acquisition early followed by a period of overextension of non-target enclitic orders between the ages of 5 and 7. They note that variability in adult production of the enclisis–proclisis split may complicate the task, as children are exposed to a variety of complex clause types. It is unclear to what degree native Galician speakers exhibit variability in clitic placement during first language (L1) acquisition. Although we are unaware of L1 acquisition studies on clitic pronouns in Galician, Pérez-Pereira’s (2007) examination of the L1 acquisition of possessives in Castilian Spanish and Galician found that children acquiring Galician, which has a formally more complex possessive system, experienced a different developmental path in L1 acquisition as compared to children acquiring L1 Castilian Spanish. If formal complexity is associated with a different order of L1 acquisition, then we should expect delays in Galician that are similar to those experienced by children acquiring EP as an L1.

2. Sentence-Level Functional Projections in Galician

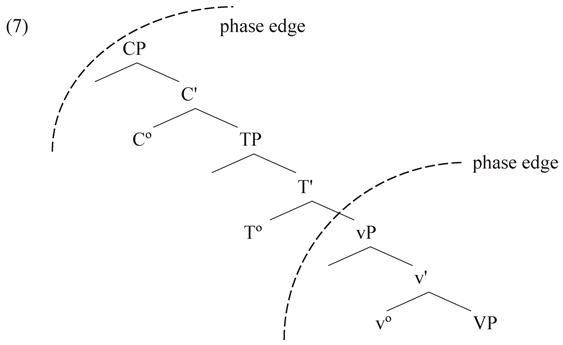

As we have briefly seen above, in order to determine the precise syntactic analysis of clitic pronouns, we have to consider a variety of preverbal constituent types.14 With respect to the sentence level, Gupton (2014a) proposes the following hierarchy of projections (16a):

| (16) | a. | FceP > TopP* > SubjP > FP(=FinP) > TP > vP > VP |

| b. | FceP > TopP* > FocP > (TopP*) > FinP > TP > vP > VP |

There are some notable differences in this hierarchy of projections as compared to the one proposed in (8, repeated as 16b) by Rizzi (1997, 2013). Based on the fact that contrastive fronted constituents exhibit clitic doubling and finite enclisis (17), Gupton concludes that Galician does not have Spanish-style focus fronting, thus eliminating the FocP projection in (16a):

| (17) | A CENORIA | o coello | comeu=na/*a comeu | (non | a mazá) |

| the carrot | the rabbit | eat.pst.3sg=cl.acc.f.sg | not | the apple | |

| ‘The rabbit ate THE CARROT (not the apple).’ | (Gupton 2014a, p. 200) | ||||

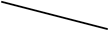

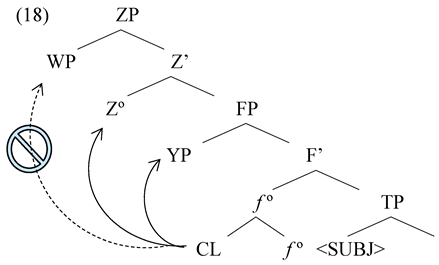

He additionally proposes that the FP projection found in Uriagereka (1995a, 1995b) and Raposo and Uriagereka (2005) is FinP, a proposal that we will return to shortly as we examine novel recomplementation data from Galician. FP plays a critical role in their analysis of clitic directionality: syntactic elements to the left of FP are understood to trigger enclitic word orders, while those in Spec, FP and to the right trigger proclitic word orders.15 According to Raposo and Uriagereka’s (2005) proposal, clitic pronouns (CL) are base generated as verbal complements for reasons related to function (for thematic role assignment within the vP, as in Baker 1988) and subsequently attracted to F° and adjoin to F = f°. Once in this configuration, a clitic must find a leftward leaning host within an immediately local domain. If a left-adjacent specifier (YP) or head (Z°) is available, this can serve as host (18). The abstract structure in (18) is understood to be operative in main clauses and subordinate clauses with wh- elements (19a), negation (19b), negative quantifiers (19c), so-called “affective” adverbial phrases (19d), and verum focus fronting (19e) in main clause contexts. In these sentences, the clitic pronoun (CL in 18) is base generated in its argument position within the VP and subsequently moves, attracted to the F head by a strong f-feature. The constituent serving as “leftward-leaning host” is proposed to occupy the (structurally) next higher specifier (YP) or the head position (Z):

| (19) | a. | A quen | (*Xoán) | lle | debe | (Xoán) | o | aluguer? |

| to who(m) | (Xoán) | cl.dat.3sg | owe. prs.3sg | (Xoan) | the | rent | ||

| ‘To whom does Xoan owe rent?’ | (Gupton 2014b, p. 141)16 | |||||||

| b. | Non | o | fixen | |||||

| neg | cl.acc.3sg.m | do.pst.1sg | ||||||

| ‘I didn’t do it.’ | (Gupton 2014a, p. 205) | |||||||

| c. | Nada | lle | dixen | porque | nin | a | ||

| nothing | cl.dat.3sg | say.pst.1sg | because | neither | cl.acc.3sg.f | |||

| lembrará. | ||||||||

| remember.fut.3sg | ||||||||

| ‘I told him nothing because he won’t remember anyway.’ | (Jaureguizar 2022) | |||||||

| d. | Xoán | xa | me | dixo | o segredo. | |||

| Xoán | already | cl.dat.1sg | say.pst.3sg | the secret | ||||

| ‘Xoán already told me the secret.’ | (Gupton 2012, p. 274) | |||||||

| e. | Algo | lle | dixo. | |||||

| something | cl.dat.3sg | say.pst.3sg | ||||||

| ‘She told him something.’ | ||||||||

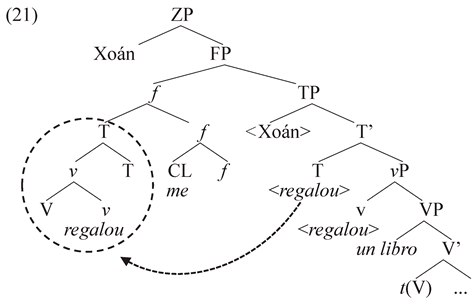

In sentences where a leftward host is unavailable, a Last Resort process named clitic swallowing takes place. Consider the structure for the Galician sentence in (20) from Gupton (2012, p. 277), where only a preverbal clitic precedes the verb. The fact that proclisis is impossible here suggests that the preverbal subject Xoán does not constitute a leftward-leaning host. In the absence of such a host, the finite verb itself moves leftward and provides a host, resulting in finite enclisis (21):

| (20) | Xoán | regalou=me | (*me regalou) | un libro. |

| Xoán | gift.prs.3sg=cl.dat.1sg | a book | ||

| ‘Xoán gave me a book.’ | (Gupton 2012, p. 274) | |||

These are proposed to be the relevant syntactic structures for sentences with finite enclisis, such as preverbal subjects (20), contrastive topics (22a), and regular CLLD topics (22b).17 Following this logic, main- and subordinate-clause proclisis results when a leftward-leaning host is available. When one is not, the verb moves to provide one, resulting in finite enclisis.

| (22) | a. | O | MEU | ÚLTIMO | LIBRO | dei=lle/*lle dei | eu | a | Paco | (non | ||

| the | my | last | book | give.pst.1sg=cl.dat.1sg | I | to | Paco | neg | ||||

| o | meu | primeiro). | ||||||||||

| the | my | first | ||||||||||

| ‘I gave MY LAST BOOK to Paco (not my first).’ | (Gupton 2012, p. 274)18 | |||||||||||

| b. | Un | bico | dába=llo/*llo daba | eu | a | esa | rapaza. | |||||

| a | kiss | give.impfv.1sg=cl.dat.3sg=cl.acc.3sg.m | I | to | that | girl | ||||||

| ‘A kiss I was giving to that girl.’ | (Gupton 2012, p. 274) | |||||||||||

Table 2, from Gupton (2014a, p. 209), summarizes clitic directionality phenomena in main clauses and subordinate clauses with a variety of preverbal constituents.

Table 2.

Summary of cliticization by clause type and preverbal element in Galician.

As we can see in Table 2, Gupton (2012, p. 275) reports a curious clitic directionality asymmetry results with preverbal subjects (20) and contrastive topics (22a), both of which trigger enclisis in main clauses, but proclisis in subordinate clauses (Cf. 23a, 23b). Regular CLLD topics, however, still result in enclisis (23c):

| (23) | a. | Xoana | díxo=me | que | Paulo | me | prestaría | o | ||||

| Xoana | say.pst.3sg=cl.dat.1sg | that | Paulo | cl.dat.1sg | lend.cond.3sg | the | ||||||

| seu | dicionario. | |||||||||||

| his | dictionary | |||||||||||

| ‘Xoana told me that Paulo would lend me his dictionary.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | Xoana díxo=me | que | O | SEU | ÚLTIMO | LIBRO | ||||||

| Xoana say.pst.3sg=cl.dat.1sg | that | the | her | last | book | |||||||

| lle | deu | a | Paco (non | o | seu | primeiro). | ||||||

| cl.dat.3sg | give.pst.1sg | to | Paco (not | the | her | first) | ||||||

| ‘Xoana told me that she gave HER LATEST BOOK to Paco (not her first).’ | ||||||||||||

| c. | Santi | dixo | que | o | poema | traducíra=o/*o traducira | ao | |||||

| Santi | say.pst.3sg | that | the | poem | translate.pstprf.3sg=cl.acc.3sg.m | to-the | ||||||

| inglés | algún | australiano. | ||||||||||

| English | some | Australian | ||||||||||

| ‘Santi said that the poem some Australian had translated it to English.’ | ||||||||||||

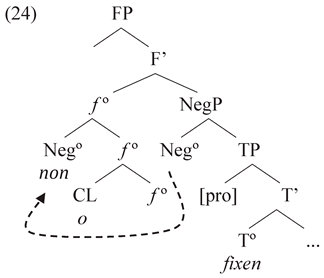

Gupton (2014a, p. 205) speculated that negation may be a clitic-like element, moving from the Neg head, and adjoining to the functional head f ° (24):

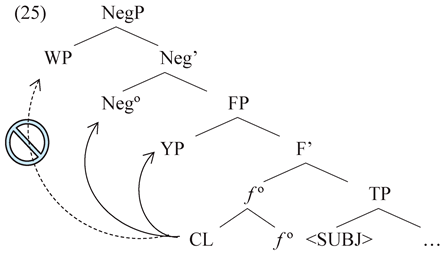

Upon reflection, however, it seems unlikely that negation is a clitic because, if it were, it too would require a left-adjacent host, contrary to fact (19b). It is clitic-like in the sense that it adjoins to another head, which goes a long way toward explaining how negation takes part in phonological reduction processes in structurally similar Romance languages like French when adjacent to verb forms (Il me a dit que… → Il m’a dit que… ‘He told me that…’); however, it is not clitic-like in Galician in that it does not require a leftward-leaning host. The predictive power of this hypothesis is largely dependent upon the explanatory power of Raposo and Uriagereka’s (2005) description of local, eligible syntactic positions for a leftward-leaning host, like we saw in (18). A possibility not examined by Gupton (2010, 2014a) is that negation should be generated to the left of FP (25):

Were negation generated in this position, it would be a possible leftward-leaning host for clitic pronouns, thus correctly generating proclitic order. We see this as welcome new insight into the structural position of negation within the syntax of Galician and will not explore it further in the current paper beyond highlighting that it is important in the sense that negation must appear to the right of a subject in preverbal position.19

Turning to preverbal subjects, we find the following positions available in Galician as proposed by Gupton (2014a):

| (26) | [TopP (SubjTop) [SubjP (SubjThetic) [FP (SubjEmbed) [f [CL + f]] [TP (Subj) [vP ( |

In (26), note that only the base-generated, postverbal position of the subject appears in strikethrough. Here, we have four possible preverbal positions: (i) Spec, TP—this position is used for preverbal subjects in sentences lacking a discourse-active FP projection to host clitic pronouns; (ii) Spec, FP—this position is used for preverbal subjects in subordinate-clause (non-root) sentences with an active FP projection hosting clitics. In such sentences, the preverbal subject serves as leftward-leaning host for clitic pronouns; and (iii) Spec, SubjP—preverbal subjects in thetic sentences. It would seem that thetic sentences should not contain clitics given that, by definition, thetic sentences do not privilege subjects or objects. However, dative clitics can appear as doubled clitics (27a) in “out of the blue” thetic sentences or as interlocutor/solidarity clitics (27b):

| (27) | a. | Dei=che | a | ti | un | libro. | ||

| give.pst.1sg=cl.2sg | to | you | a | book | ||||

| ‘I gave you a book.’ | (Freixeiro Mato 2006, p. 133) | |||||||

| b. | A | miña | filla | casou=che. | ||||

| the | my | daughter | marry.pst.3sg=cl.2sg | |||||

| My daughter got married.’20 | ||||||||

Position (iv) Spec, TopP—this position is for topicalized XP constituents in matrix or embedded sentences, both of which trigger enclitic orders.21 Following Raposo and Uriagereka (2005), this means that this position lies beyond the range of what may serve as a leftward-leaning clitic host.

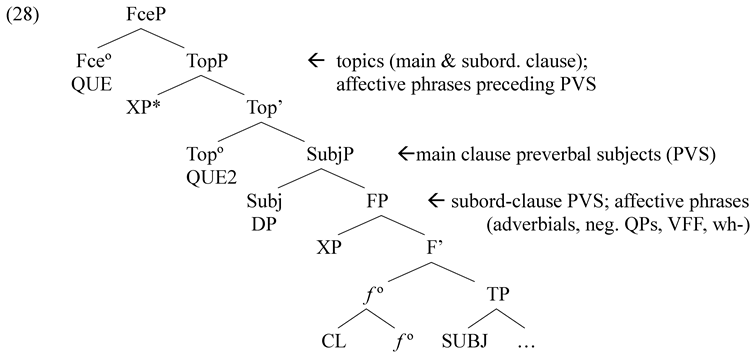

As we can see in (28), Gupton (2014a, p. 237) places a number of preverbal subject (PVS) constituents in Spec, FP, among these subordinate clause preverbal subjects and affective phrases, which includes adverbials, negative QPs, verum focus fronting (VFF) and wh-elements. Curiously, however, this model of the clausal hierarchy does not account for contrastive topics in Galician:

At the time, it came to light that Galician has a contrastive fronting mechanism that requires clitic doubling (29; cf. Gupton 2014a, p. 63), unlike Spanish, which does not allow for clitic doubling with contrastive focus fronting (30):22

| (29) | A | CENORIA | o | coello | comeu=na / | *a comeu | (non | a | mazá) | |

| the carrot | the | rabbit | eat.pst.3sg=cl.acc.3sg.f | neg | the | apple | ||||

| ‘The rabbit ate THE CARROT (not the apple).’ | ||||||||||

| (30) | LA ZANAHORIA (*la) | comió | el conejo | (no | la | manzana) | ||

| the | carrot | cl.acc.3sg.f | eat.pst.3sg | the rabbit | neg | the apple | ||

| ‘The rabbit ate THE CARROT (not the apple).’ | ||||||||

Given that preverbal subjects (20) and contrastive topics (22a) have similar clitic behavior, with finite enclisis in main clauses and proclisis in subordinate clauses (23a, 23b), we can conclude that these topic XPs do not appear as high as topical CLLD topics (22b, 23c) because CLLD topics do not trigger proclisis in either situation. Therefore, they must appear to the immediate left or right of the preverbal subject in SubjP. Consider (31) from Gupton (2014a, p. 223):

| (31) | Dubido | que | onte | Fran | a | Ana | (*que) | a | |

| doubt.prs.1sg | comp | yesterday | Fran | to | Ana | comp | cl.acc.3sg.f | ||

| chamase | |||||||||

| call.pst.sbjv.3sg | |||||||||

| ‘I doubt that yesterday Fran called Ana.’ | |||||||||

Here, a series of topics precedes the proclitic direct object pronoun. Now, bearing in mind that regular topics are accompanied by finite enclisis in main clauses as well as subordinate clauses, this is strongly suggestive that a Ana (‘to Ana’) is a contrastive topic, which would leave us with an explanation of why we have a proclitic subordinate clause in this example. To gain a more precise idea of exactly where in the clausal architecture these subjects appear, let us examine them in the lowest clause within a recomplementation structure.23 For Villa-García (2012), the lowest complementizer QUE in a recomplementation structure appears in the Fin head in jussive/optative sentences. Following the predictions of Villa-García (2012) for Spanish, jussive/optative QUE should be required when the embedded predicate appears in the subjunctive mood. The Galician data in (32, 33) confirm a similar behavior in Spanish:24

| (32) | a. | Dixéron=me | que, | se | chove, | (que) | vén | ||

| tell.pst.3pl=cl.dat.1sg | comp | if | rain.prs.3sg | comp | come.prs.3sg | ||||

| o | seu | curmán | |||||||

| the | his | cousin | |||||||

| ‘They told me that, if it rains, (that) his cousin is coming.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Dixéron=me | que, | se | chove, | *(que) veña | ||||

| tell.pst.3pl=cl.dat.1sg | comp | if | rain.prs.3sg | comp | come.prs.sbjv.3sg | ||||

| o | seu | curmán | |||||||

| the | his | cousin | |||||||

| ‘They told me that, if it rains, his cousin should come.’ | |||||||||

| (33) | a. | Dixéron=me | que, | se | chove, | (que) | o | seu | curmán | ||

| tell.pst.3pl=cl.dat.1sg | comp | if | rain.prs.3sg | comp | the | his | cousin | ||||

| cobre | o tractor | ||||||||||

| cover.prs.3sg | the tractor | ||||||||||

| ‘They told me that, if it rains, (that) his cousin is coming.’ | |||||||||||

| b. | Dixéron=me | que, | se | chove, | *(que) o | seu | curmán | ||||

| tell.pst.3pl=cl.dat.1sg | comp | if | rain.prs.3sg | comp | the | his | cousin | ||||

| cubra | o tractor. | ||||||||||

| cover.prs.sbjv.3sg | the tractor | ||||||||||

| ‘They told me that, if it rains, his cousin should come.’ | |||||||||||

Within the clausal hierarchy proposed in (28), clitics appear in F/Fin. Assuming that the jussive/optative QUE appears in the Fin head of the most deeply embedded clause, this should preclude the clitic from appearing as high as F/Fin. Therefore, the prediction is that we should find proclisis following jussive/optative QUE, a prediction that is borne out (34):

| (34) | Dixéron=me | que, | se | neva, | [FinP [Fin’ | que | o | tío | ||||

| tell.pst.3pl=cl.dat.1sg | comp | if | show.prs.3sg | comp | the | uncle | ||||||

| os | chame/*cháme=os | porque | non | queren | ||||||||

| cl.acc.3pl.m | call.prs.sbjv.3sg | because | neg | want.prs.3pl | ||||||||

| perde-lo]] | ||||||||||||

| lose.inf-cl.acc.3sg.m | ||||||||||||

| ‘They told me that, if it snows, that (my) uncle should call them because they don’t want to lose him.’ | ||||||||||||

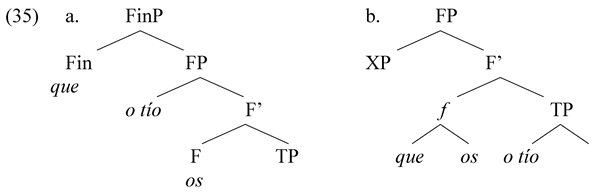

Given that the clitic pronoun appears to the right of jussive/optative QUE, which is proposed to occupy Fin, it seems that Gupton’s (2010, 2014a) suggestion that FP and FinP are one and the same functional projection appears to not be sustainable. What is more, in (34) we have an intervening preverbal subject o tío ‘(my) uncle’, which appears between the complementizer and the clitic. Gupton assumes Raposo and Uriagereka’s (2005) clitic account, by which clitic pronouns in languages like Galician and European Portuguese are attracted to the F head. In order to maintain the Raposo and Uriagereka account of F being the locus of clitics in the preverbal field, it seems preferable to propose that the FP projection appears lower than F in the clausal hierarchy (35a) rather than to assume that jussive/optative complementizers may be base generated in a position that is head-adjoined to f ° (35b):

In both structures, jussive/optative complementizer QUE is available to serve as a local, leftward-leaning host, as discussed above (18). However, it is not clear how the analysis in (35b) would account for the fact that a preverbal subject o tío (‘his uncle’) appears between the jussive/optative complementizer and the clitic pronoun. If we assume that the preverbal subject here appears in Spec, TP in (35b), it would be descriptively inadequate to propose that the clitic pronoun appears between the complementizer que and the subject (i.e., *…que os o tío chame…) because this order is not attested in Galician. In (35a), the preverbal subject can appear in Spec, FP, which is structurally between the complementizer and the clitic.

In the preceding, we have seen that Galician has a wide number of positions available for subjects in the preverbal field, which bears potential for deepening our understanding of cross-linguistic micro-variation of the type discussed in Kayne (2005) and Lardiere (2009), whose proposals suggest that crosslinguistic differences can be captured by differences of features, and how those features are distributed and/or assembled across associated syntactic projections. Moving on, how do the theoretical proposals square with the empirical data? According to the experimental results presented in Gupton (2010, 2014a, 2014b) and Gupton and Leal-Méndez (2013), Galician participants rated sentences with preverbal subjects (i.e., SV(O)) highest in response to a wide variety of contexts that manipulated information structure. These contexts adopted the basic information structure assumptions of López’s (2009) model of the syntax-information structure interface for Spanish and Catalan. Subject–verb (SV) word orders were preferred in thetic sentences and object narrow-focus contexts, while SV and verb–subject (VS) sentences were similarly preferred in response to subject narrow-focus contexts, which suggested that Zubizarreta’s (1998) account of syntax-focus structure, which predicts that narrow-focused (i.e., rheme) constituents should appear at the rightmost clausal edge, would require some reformulation for Galician.25 The design of this task, however, was based on quantitative studies of SLA from a generative perspective, employing an Acceptability Judgment Task (AJT) accompanied by a five-point Likert scale. Participants read constructed contexts and then rated three possible response/continuation sentences with different word orders (36a–c):

| (36) | Context: Xoán and Iago are friends. They are talking about the weekend. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Xoán – | Que | fas | esta | noite? | |||||||||||||||||

| what | do.prs.2sg | this | night | ||||||||||||||||||

| Xoán – | ‘What are you doing tonight?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Iago – | Por que? | Que | pasa? | ||||||||||||||||||

| why | what | happen.prs.3sg | |||||||||||||||||||

| Iago – | ‘Why? What’s up?’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | Xoán – | Carlos | vai | celebrar | o | seu | aniversario. | (SVO) | |||||||||||||

| Carlos | go.prs.3sg | celebrate.inf | the | his | birthday | ||||||||||||||||

| b. | Xoán – | Vai | celebrar | Carlos | o | seu | aniversario. | (VSO) | |||||||||||||

| go.prs.3sg | celebrate.inf | Carlos | the | his | birthday | ||||||||||||||||

| c. | Xoán – | Vai | celebrar | o | seu | aniversario | Carlos. | (VOS) | |||||||||||||

| go.prs.3sg | celebrate.inf | the | his | birthday | Carlos | ||||||||||||||||

| Xoán – | ‘Carlos is going to celebrate his birthday.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||

A methodological limitation of this task reported in Gupton (2010, 2014a, 2014b) is that participants are limited by the word orders provided, and some remarked that the sentences that they were asked to rate did not seem very natural. Given that the goal of this study was to inform the syntactic position of preverbal subjects, repeating potentially repetitive constituents in possible replies was often necessary, even when that might not have resulted in the most natural order. An additional criticism of this methodology is that it requires minimal speech production, thus calling into question whether such sentence responses appear in naturally-occurring speech. Cruschina and Mayol (2022, p. 10) propose a methodology that seeks to remedy limitations related to information structure context while encouraging natural repetition of previously mentioned information and plausibility in production at once. Consider the English examples in (37–38):

| (37) | You go to your parents’ place. You show your mum a watercolor portrait of yourself. She asks “Who drew it?”. At that point you get a phone call. Somebody got the wrong number. You hang up and, to answer your mum, you say: |

| (38) | You are watching a film with your roommate. Since she wakes up really early every day, she falls asleep and misses the ending. When you switch off the TV, she wakes up and asks you: “What did they find? I don’t think I’ll watch this movie again. I’m sure I would fall asleep again.” To reply you say: |

The authors show that this methodology can be employed with an open reply, thus better assuring the collection of production data; however, it may also be used as part of an acceptability judgment task, but with one single response option. Given the success that Cruschina and Mayol had in testing the protocol for Catalan, its potential for application for further study of Galician is enticing, and it promises to be a more reliable and more natural tool in eliciting introspective judgments in addition to speech production.

3. Word–Level Interactions

We now turn our attention to the allomorphy seen between definite determiners and 3rd-person (accusative) object clitics in Galician, a topic that has been reviewed in both traditional grammars and by formal accounts. Concerning the latter group of investigations, there has been considerable overlap regarding the most reliable source for surface phonological forms. What these authors’ analyses have in common is that the phonological component is claimed to be the locus for the observed variation.

We focus on the recent contributions to this puzzle, such as Kastner (2024, p. 3), who argues that what we see in the phonological alternation of determiners and clitics is not true allomorphy but instead “a series of phonological adjustments that Galician makes to stem codas when a clitic triggers resyllabification and turns them into onsets.” We shall not attempt to make an argument for or against true allomorphy versus the simpler posit of phonological alternations, and we use these terms interchangeably here. We believe that the resyllabification highlighted by Kastner is, indeed, an elemental aspect of the surface form of these morphemes, as we may not rely solely on the syntax and morphology to derive the given forms. However, we do contend that cliticization of all types is obligatory when possible (cf. Preminger 2019; Deal 2024. a.m.o.), and thus the syntax proper is ultimately responsible for the possible modifications made in the phonological component. That is, we may say that for all phonological alternations, the syntax feeds the phonology. Our goal in this section is to challenge a number of aspects of arguments focused solely on the phonological branch and wish to highlight the compositional module responsible for the data below. First, we contend that the most important component of this alternation lies in the syntax. Without assuming a strict understanding of the syntactic configuration that feeds cliticization (as well as determiner cliticization), it is impossible to account for why this alternation is only found in the specific structures observed in the literature and not others.26 We then briefly address what we consider to be morphological aspects of allomorphy. Assuming a Late-Insertion model of morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994), we draw on notions from Deal and Wolf (2017) regarding the syntactic nature of allomorphic variability, showing that the phonological variation found in Galician clitics and determiner clitics is heavily conditioned by the serial inside-out manner of allomorphic conditioning. Finally, we touch on what we show to be the primary aspect of the alternation that falls within the realm of the phonological component and that which deals with the most intricate system of phonological alternation seen in the resyllabified forms of both clitics and determiners. We claim that it is here where phonology plays the largest part, but only after the contributions of the syntax and the morphology have been accounted for.

Before continuing to our data and analysis, it is important to note that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to all of the variation seen with this phenomenon across all ages and geo-linguistic delineations throughout Galicia. The data and grammatical judgements under investigation in this section are those of what we deem a conservative syntactic system, i.e., a system that indeed has syntactic restrictions and is typically found to be broader in its extension than that commonly encountered in younger speakers. However, it is worth pointing out that there are also speakers of older generations with systems that lack the syntactic-based determiner cliticization patterns we describe below, which may point to the linguistic exposure within a given geographical area of a speaker as the primary cause of variation here.

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

The observations concerning clitic and determiner allomorphy have been at the heart of descriptive analyses in Galician since the earliest descriptive grammars (Lugrís Freire 1931) and have occupied an important place in the more contemporary approaches to the language (Freixeiro Mato 2006). While there is vast dialectal variation amongst speakers due to factors such as age (Louredo Rodríguez 2022) and geographical location (Dubert García 2014, 2016), we primarily focus on the most conservative patterns.27

Freixeiro Mato (2006) makes reference to these allomorphs as ‘first forms’ and ‘second forms.’ Additionally, we will make use of the term ‘third form,’ although we shall see that there resyllabification plays an important part in determiner cliticization with these forms. We summarize these forms in Table 3.

Table 3.

Galician clitic-determiner allomorphy.

A first form clitic is said not to (significantly) modify its host phonologically, e.g., when the clitic matches the declension of a verb, with most of the literature dealing with phonological reduction as in the case of (39a). The same may be considered for determiner clitics (39b):

| (39) | a. | Véxo=o | claramente | ||

| see.prs.1sg=cl.acc.m.sg clearly | |||||

| ‘I clearly see it.’ | |||||

| [be.∫oː] | |||||

| b. | Baralla | as | cartas | ||

| shuffle.prs.3sg | the.f.pl | cards | |||

| ‘She shuffles the cards.’ | |||||

| [ba.ɾa.ɟaːs] | |||||

Second forms are found under very specific contexts, all of which are enclitic in nature (although not necessarily on the verb; cf. 40c). For verbs, these forms appear when they end in /s/ or /r/ (40a), while determiners may cliticize to verbs (40b) or plural quantifiers such as todos (‘all’) and ambos (‘both’) (40c). In both instances, the lateral /l/ replaces the rhotic or sibilant phoneme:

| (40) | a. | Fixémo=lo | (*Fixemos o) | ||

| do.pst.1pl- cl.acc.m.sg | |||||

| ‘We did it.’ | |||||

| b. | Cantámo=las | mulleres | (Cantamos as mulleres) | ||

| sing.pst.1pl-the.f.pl | women | ||||

| ‘Us women sang.’ | |||||

| c. | Tódo=los | cans | (%Todos os cans) | ||

| all-the.m.pl | dogs | ||||

| ‘All of the dogs’ |

Third forms are unique in the sense that clitics and determiners do not share these forms in the same contexts or, as some may argue, at all.28 The cliticized version of these third forms appears only on verbs ending in a diphthong, which is restricted to 3rd person past tense forms (41a). However, these forms are not attested with determiners in the same manner, unlike what we saw with first and second forms above (41b):

| (41) | a. | Veu=no | na | beira | ||

| see.pst.3sg=cl.acc.m.sg | in.the | bank | ||||

| ‘She saw it along the bank.’ | ||||||

| b. | *Levou=nos | regalos | á | festa | ||

| carry.pst.3sg=cl.acc.m.pl | gifts | to.the | party | |||

| Intended: ‘She took the gifts to the party.’ | ||||||

From a purely phonological perspective, it is unclear why third form determiners would differ from those of the first or second forms, which has been an issue of much discussion in the literature on the phonological alternation outlined here (cf. Kikuchi 2006; Ulfsbjorninn 2020; Kastner 2024). What these accounts fail to take into consideration is the syntactic relation of these constituents in both pre- and post-verbal scenarios. We find the comparison between these two patterns to be an underexplored area of Galician clitics and determiners, albeit in a different manner than discussed in §2.

3.2. Returning to the Syntax

We begin by reviewing the underlying syntactic dependency that feeds the phonological alternation in direct object cliticization. While commenting on the precise syntactic mechanism that is responsible for cliticization and determiner cliticization more generally is beyond the purview of our purposes here (see Uriagereka 1996 and Gravely and Gupton 2020 for proposals), our focus will be on the structural relation that we claim is predicated on the phonological variation in clitics and determiners. The outcome of these claims will have a direct correlation with the morphological component observe in the next subsection.

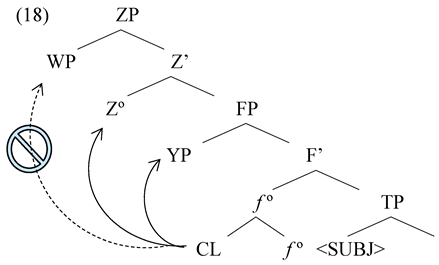

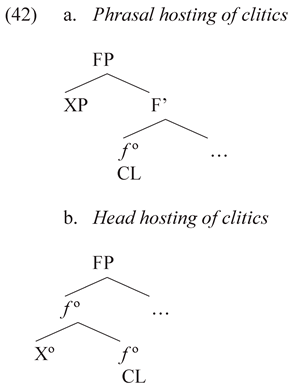

As we saw in §2, Galician clitic positioning requires a preceding constituent local enough to host it, be that the verb or another left-peripheral element (Uriagereka 1995a; Raposo and Uriagereka 2005; Gupton 2014a, a.o.). Recall that there are two structural possibilities for this relation, depicted in (42a) and (42b), where either XP or X° are understood to have undergone movement to the left of the head that hosts the clitic (cf. 10):

While both (42a) and (42b) are viable clitic hosting structures, Gravely (2021a) showed that they result in different phonological outputs. There it was claimed that the velarization in (43a) versus the resyllabification in (43b) is a direct result of the phrasal nature of the former versus the head-to-head relation of the latter:

| (43) | a. | No | chan | a | atoparon | |

| on.the | floor | cl.acc.f.sg | find.pst.3pl | |||

| ‘On the floor they found it’ | ||||||

| -> No [tʃaŋ.aː.to]paron | ||||||

| ~> *No [tʃa.naː.to]paron | ||||||

| b. | Non | o | vin | |||

| neg | cl.acc.m.sg | see.pst.1sg | ||||

| ‘I didn’t see it.’ | ||||||

| -> [no.no] vin | ||||||

| ~> *[noŋ.o] vin |

The same may be observed with the more phonologically salient second forms when a plural preverbal nominal constituent provokes proclisis:

| (44) | Todas | o | facemos |

| all.f.pl | cl.acc.m.sg | do.prs.1pl | |

| ‘We all do it.’ | |||

| -> [to.ða.so] facemos | |||

| ~> *[to.ða.lo] facemos | |||

We may refer to this as the phrase-head hosting restriction:

| (45) | Phrase-head hosting restriction |

Where both phrases and heads may serve as syntactic hosts for a clitic element, only clitics in a head-to-head relation may undergo phonological reconstruction.

For determiner cliticization, the same structural relation applies. Consider the (im)possibility of determiner cliticization below (12a,b repeated as 46a,b):

| (46) | a. | Comemos | o | caldo | |||

| eat.prs.1pl | the | soup | |||||

| ‘We eat soup.’ | |||||||

| -> Come[mo.so.kal]do | |||||||

| -> Come[mo.lo.kal]do | |||||||

| b. | Son | boas | as | cancións | |||

| be.prs.3pl | good.f.pl | the.f.pl | songs.pl | ||||

| ‘The songs are good.’ | |||||||

| -> Son [bo.a.sas.kan]cións | |||||||

| ~> *Son [bo.a.las.kan]cións | |||||||

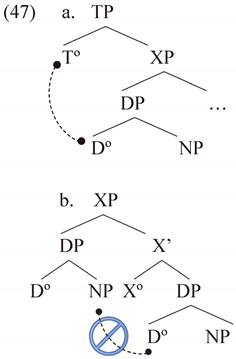

Much like the phrase/head hosting restriction for cliticization more generally, the same may be postulated for determiner cliticization. Although boas (‘good’) and as cancións (‘the songs’) are in a predicative relation semantically, their syntactic structure fails to meet the standards in (45) as schematized in (47b). The structure in (47a), however, meets these requirements and, thus, determiner cliticization is licit:

In Gravely and Gupton (2020), it was proposed that this relation was the direct result of Marantz’s (1988, 1989) notion of structural adjacency:

| (48) | Structural adjacency | |

| A head X is structurally adjacent to a head Y if: | ||

| (i) X c-commands Y | ||

| (ii) There is no head Z that | ||

| a. is c-commanded by X and | ||

| b. c-commands Y | ||

This head-to-head relation is the first requirement for the perceived phonological alternations in (determiner) cliticization.

The second aspect that takes the notion of structural adjacency and the head-to-head relation a step further is that of structural governor. This term was introduced in Uriagereka (1996) upon showing that determiner cliticization was not simply the result of phonological allomorphy but, instead, held in only a certain number of syntactic environments. Compare the (in)ability of the cliticization patterns to undergo phonological alternation in data below:

| (49) | a. | Por | o | faceres | ben | ||||

| comp | cl.acc.m.sg | do.inf.2sg | well | ||||||

| ‘For (you) doing it well’ | |||||||||

| -> [poɾ.o.fa]ceres ben | |||||||||

| ~> *[po.lo.fa]ceres ben | |||||||||

| b. | Por | o | ben | de | todos | ||||

| for | the. | m.sg | well | of | all.m.pl | ||||

| ‘For the wellbeing of everyone’ | |||||||||

| ~> *[poɾ.o.beŋ] de todos | |||||||||

| -> [po.lo.beŋ] de todos | |||||||||

Without accounting for the syntactic differences of (49a–b), the only viable claim would be that determiners have more robust cliticization patterns than syntactic clitics, a claim that has been argued against on multiple accounts (e.g., Uriagereka 1996; Gravely 2021a). However, the lack of determiner cliticization is also seen when the lexical item por (‘for’) serves as a complementizer (C°) rather than a preposition (P°):

| (50) | Por | a | nai | ir | amodiño |

| comp | the.f.sg | mother | go.inf | slow.dim | |

| ‘For mom going slowly’ | |||||

| -> [poɾ.a.naj] ir amodiño | |||||

| ~> *[po.la.naj] ir amodiño | |||||

The idea of category selection is not present in Kastner’s (2024) rejection of a syntactic account, where he argues that the syntax is unable to explain cases as in (51):

| (51) | Ver | a | Rosa |

| see.inf | dom | Rosa | |

| ‘To see Rosa’ | |||

| -> [beɾ.a.ro.sa] | |||

| ~> *[be.la.ro.sa] | |||

In fact, we believe that this explanation is readily available to the syntax if one considers the homophonous a may indeed cliticize but only as a determiner for (e.g., Vemo-la Rosa ‘We see Rosa’).29 If we consider that the differential object marker is a P° or K° (cf. Kalin 2018; Gravely 2021b), we should not expect phonological alternation at PF due to the fact that prepositions (or case-marking heads) do not cliticize to verbs. What we find here, in addition to what we show below, proves that there are both structural and categorial syntactic considerations that play a larger role than what we find in the phonology.

3.3. What Impossible Combinations Say about Syntax

For further evidence for a syntactic consideration of the phonological alternations in question, we may look at situations in which determiner cliticization is completely banned. Observe the data in (52) below:

| (52) | a. | Levantáron=nos | os | toldos | ||

| lift.pst.3pl=cl.dat.1pl | the.m.pl | column.pl | ||||

| ‘They picked up the columns for us.’ | ||||||

| -> Levantaro[no.sos] toldos | ||||||

| -> Levantaro[no.los] toldos | ||||||

| b. | Asustáron=os | as | curuxas | |||

| scare.pst.3pl=cl.acc.m.pl | the.f.pl | owl.pl | ||||

| ‘The owls scared them.’ | ||||||

| -> Asusta[ɾo.no.sas] curuxas | ||||||

| ~> *Asusta[ɾo.no.las] curuxas | ||||||

In addition to verbs and prepositions, we see that dative clitics are structural governors that may provoke allomorphy with a cliticizing accusative or determiner clitic, as well (52a). However, this phonological alternation is impermissible for a determiner attempting to cliticize onto an accusative clitic (52b). We may immediately rule out a phonological account of this restriction, as, e.g., 1st person plural morphology, contains the same (final) phonological segment as plural direct object clitics /os/ (53; cf. 52a):

| (53) | Falamos | o | tema |

| speak.prs.1pl | the.m.sg | topic | |

| ‘We talk about the topic.’ | |||

| -> Fala[mo.lo] tema | |||

Moreover, it cannot be a question of the morpho-phonology of the clitic the determiner attempts to cliticize to, as seen with the ambiguous /nos/, which can be either 1st person accusative or dative. Determiners are only banned from cliticizing in the former case (54), not the latter (52a):

| (54) | Asustou=nos | o | estrondo | |

| scare.pst.3sg=cl.acc.1pl | the.m.sg | bang | ||

| ‘The bang scared us.’ | ||||

| -> Asustou[no.so] estrondo | ||||

| ~> *Asustou[no.lo] estrondo | ||||

Finally, we see that accusative clitics play a part in determiner cliticization even when they are not found together in a linear order:

| (55) | Non | os | collemos | as | pícaras | nunca |

| neg | cl.acc.m.pl | grab.prs.1pl | the.f.pl | girls | never | |

| ‘Us girls don’t ever take them.’ | ||||||

| -> Non os colle[mo.sas] pícaras | ||||||

| ~>* Non os colle[mo.las] pícaras | ||||||

In (55), there is nothing inherently morphological or phonological that should prevent the cliticization of the determiner as to the verb in the 1st person plural. If we consider that there are restrictions within the syntax that bleed cliticization of the determiner based on the cliticization of the accusative, we may rule out both morphological and phonological explanations that fall short.

3.4. A Note on the Morphology and Phonology after Syntax

While there are considerations that extend beyond the space limitations of this paper, we first comment on some morphological and phonological determining effects based on the syntax discussed above. Before addressing the phonological component, we wish to highlight what we consider to be the instances of allomorphic spell out of the morphemes in question. We follow Deal and Wolf (2017) in assuming that morphological allomorphy may be accounted for via a direct reading of the syntax in a cyclic manner. While this does not inherently involve an inside-out serial direction, what these authors show is that within the same cyclic domain, morphemes may provoke allomorphy in either direction, inside out or vice versa. For the phenomenon in question, we maintain that the phonological alternations under investigation are indeed cases of inside-out serial allomorphy, where additional phonological alternations to the hosts may be made after Vocabulary Insertion has taken place.

The most obvious case of this is the second form highlighted above in Table 3. Descriptively, we saw in §3.1 is that the second form appears when the verb ends in /r/ or /s/. We may posit the second-form spell-out condition as below:

| (56) | a. | cl ⟷ lo/__ {T°, Ø} |

| b. | cl ⟷ lo/__ {T°, 2sg} | |

| c. | cl ⟷ lo/__ {T°, 1pl} | |

| d. | cl ⟷ lo/__ {T°, 2pl} |

We should expect similar spell-out rules for cliticized determiners (i.e., those that have vacated the DP), with the only caveat concerning our reference above to syntactic situations in which determiner cliticization is illicit (cf. 52b, 55).30 For example, in cases of determiner cliticization within PPs, we may find a spell-out rule as in (57):31

| (57) | cl ⟷ lo/__ {P°, √por} |

One may be tempted to posit the same for the third forms, claiming that /n/-insertion of these allomorphs can be simply the result of cliticization to a 3rd person past tense verb:

| (58) | cl ⟷ no/__ {T°, +pst, 3sg} |

However, with irregular past tense forms such as fixo (‘do’) and trouxo (‘bring’), this Vocabulary Item overgenerates. For Kastner (2024, pp. 8–9), this is simply a rewrite rule that requires /n/-insertion after a diphthong syllable in a specific conditioning environment. However, this, too, lacks explanatory power, as nothing about Kastner’s system prevents cases as in (59), which he claims to be hesitant to try to explain within a system of phonological resyllabification:

| (59) | *EU=no | fixen, | non | ela |

| I=cl.acc.m.sg | do.pst.1sg | neg | she | |

| ‘I did it, not her.’ | ||||