Abstract

Causal relations allow a very detailed insight into the narrative skills of children from various backgrounds; however, their contribution has not been sufficiently studied in bilingual populations. The present study examines the expression of causal relations and the linguistic forms used to encode them in narratives of bilingual children speaking Russian as the Heritage Language (HL) and Hebrew as the Societal Language (SL). Narratives were collected from 21 typically developing Russian–Hebrew bilingual children using the Frog story picture book and were coded for frequency and type of episodic components, and for causal relations focusing on enabling and motivational relations. Results showed that the number of episodic components was higher in Hebrew than in Russian. An in-depth analysis showed that more components were mentioned in the first five episodes, particularly at the onset of the story. Causal relations were similar in both languages but were differently distributed across the languages—more enabling relations in Russian stories and more motivational relations in Hebrew stories. Production of episodic components and causal relations was affected by language proficiency but not by age of onset of bilingualism (AoB). In terms of language forms, lexical chains (e.g., search~find) were the most frequent means for inferring relations. Syntactic and referential cohesion were used in dedicated episodes to convey relations in both languages. Finally, a higher number of significant correlations between narrative productivity measures, episodic components, and causal relations were found in SL/Hebrew than in HL/Russian. The study results underscore the need to understand how language-specific abilities interact with knowledge of narrative discourse construction.

1. Introduction

Narratives play a fundamental role in children’s linguistic and socio-cognitive development (; ). They lie at the core of daily conversations with adults and peers (), and they are strongly related to the development of linguistic literacy and academic skills (). As a basic form of extended discourse that emerges in early childhood, narratives provide a rich and ecologically valid way to assess language abilities beyond the sentence level in monolingual (; ) and bilingual children (; ; ).

A bulk of research on bilingual narratives has been conducted to investigate macro- and micro-levels of narrative structure and the way these levels correlate (e.g., ; ; ; ). Macrostructure refers to the universal cognitive scheme that guides narrative organization and is mainly assessed by story grammar models in terms of episodic components, such as settings, initiating events, goals, attempts, and outcomes (; ). Microstructure addresses language-specific abilities, such as lexical productivity and diversity, and morphological and syntactic complexity (; ). While using meticulous methodologies that tap into these two levels of narrative abilities, such studies often treat micro- and macrostructure measures as two separate domains, ignoring the function of forms (e.g., lexical diversity or syntactic units) as cohesive devices () for connecting events into units of discourse. Thus, it remains unclear to what extent and in which ways these two levels are interrelated in bilingual narratives.

To fill this gap in the literature, the present study focuses on a less studied narrative domain—the expression of causal relations—in bilingual children aged 5–6, speakers of Russian as Heritage Language (HL) and Hebrew as Societal Language (SL). The following excerpt from the narrative of a bilingual boy aged 5 years 11 months, in Hebrew, illustrates this domain.

- (1)

- ‘His dog barked, he made noise, and the boy told him: “Hush, don’t speak, we need to catch the frog”. And then suddenly they looked behind the tree log. They saw that froggy fell in love with a frog’.

The causally related clauses in example (1) create a meaningful unit. Barking causes noise that might scare the frog. This motivates the boy to hush the dog and to explicitly state his desire to catch the frog, which is accomplished by their attempt, i.e., looking behind the log, which enables them to find the lost frog. Language intervenes in the creation of causal chains in explicit ways using coordination (e.g., ‘and’) and referential strategies (e.g., pronouns and lexical repetition). However, causality is mainly expressed in subtle ways via lexical connectivity (e.g., barking is causally related to making noise), as reported in previous studies (; ). Through the lens of causal relations and their linguistic expression, the study aims to understand how language abilities relate to the macro-level of organizing events to create a coherent story (; ; ). Studying Heritage Speakers at the age of 5–6 is particularly interesting, since preschool children have already acquired a rich vocabulary and a complex set of morpho-syntactic structures but are still at the emergent phases of discourse construction (). Thus, the study is intended to identify unique linguistic and discourse processes in the narratives of Heritage Speakers at this early age, and to shed light on the influence of language-internal and language-external factors () on narrative production abilities in the HL and the SL.

2. Theoretical Framework

Two main approaches were adopted in studies of bilingual narratives—one that compared bilingual with monolingual performance, and one that conducted cross-language comparisons within bilinguals. The former approach allowed to unravel the effects of language—independent cognitive abilities and of language—specific knowledge on narrative production, while the latter has focused on cross-language interdependence (; ; ; ) and on various factors affecting performance in each of the languages, e.g., AoB, (). The present paper employs the latter approach of cross-language comparison as the major source of knowledge about bilingual narrative skill, with some reference to bilingual and monolingual comparisons. Section 2.1 reports on studies performed within the framework of macrostructure and microstructure analysis; Section 2.2 presents form–function approaches in the study of bilingual narratives, including studies that addressed causal relations.

2.1. Macrostructure and Microstructure in Bilingual Narratives

In the last two decades, macro- and microstructure analyses of narrative production have become the mainstream methodology for assessing narrative abilities and for disentangling typical from atypical language in bilingual children (; ; ; ; ; ). Some of these studies also investigated macro- and microstructure correlations within and across languages (e.g., ), and the influence of language proficiency and exposure on narrative skills aiming to understand the sources of strengths and weaknesses in narrative production and comprehension.

() study with young sequential Spanish–English bilinguals was among the first to analyze both bilinguals’ languages. Using two story elicitation tasks with varying complexity, they found cross-language similarity in macrostructure performance with some differences in the type of story grammar elements that children included in each language, which were attributed to possible socio-cultural differences. Measures of linguistic productivity and grammaticality were also similar in the two languages, although cross-linguistic influence from Spanish to English was noticed in the more challenging elicitation task (a picture book narrative), where children were producing longer and more complex stories that demanded higher linguistic efforts. In a more recent study with Cantonese–English preschoolers, () found differences in macrostructure across languages, which was attributed to cultural factors and exposure to literacy, but no differences were reported for microstructure. An opposite trend was found by () in a study with Spanish–English bilinguals, which reported strong cross-language correlations in the story structure score but low correlation in lexical and morpho-syntactic measures.

A series of path-breaking studies using the Multilingual Assessment Instrument for Narratives (LITMUS-MAIN, , ) targeted macro- and microstructure measures in the narratives of preschool and early school-age bilingual children speaking different language combinations ( on Russian–Hebrew; on Swedish–English; on Russian–German; on Finnish–Swedish, among others). The LITMUS-MAIN coding system targets story structure (the number of macrostructure components produced by children) and story complexity (inclusion and combination of episodic elements). Most of the studies reported a similar performance across bilinguals’ two languages in terms of story structure and story complexity (see for a comprehensive overview). Macrostructure abilities were found to be sensitive to age and language proficiency, but they were not related to the amount of input and length of exposure to both languages (e.g., ; ; ).

Age played a major role in the cross-language variability of macrostructure. In a study with Russian–German bilinguals from age 3 to 10, () found similar story structure scores across languages at preschool, but higher scores in SL/German by school age, arguing for a possible effect of literacy experiences on narrative skills. A similar trend was found for internal state terms (ISTs), used to measure inferred components of the narrative, which were similar in both languages at the younger ages, but higher in SL/German after first grade, when lexical richness increased in SL. A few exceptions showed an advantage for stories produced in HL, particularly among young sequential bilinguals with lower proficiency in their SL (e.g., ). All in all, measures of story complexity were found to be transferable between the languages and less influenced by reduced linguistic experience in one of the languages (; ; ), while ISTs and number of components might be more affected by linguistic proficiency and literacy experiences at school.

There is a wider consensus in the literature for microstructure abilities to be less comparable across languages () but results are inconsistent. A few studies found similar performance on microstructure measures in the two languages (; ), but these focused on productivity measures only (e.g., total number of words in the story). In a study that compared English–Hebrew bilinguals with TLD and DLD using LITMUS-MAIN, () found an advantage for HL/English on lexical productivity and diversity and on morpho-syntactic measures, which were not affected by length of exposure (LoE) to Hebrew, possibly due to the high prestige of English, the home language. Several studies reported on some microstructure measures being more affected by language proficiency, input, and exposure than others (). In a study with preschool Norwegian–Russian bilingual children, () found that measures of syntactic complexity and discourse connectives were similar in both languages, but language-specific lexical and morpho-syntactic measures were not, suggesting that certain linguistic abilities can be transferable across languages.

The question of whether macro- and microstructure measures are correlated within and across the languages of bilinguals yielded inconclusive results as well. While most studies with monolingual children found a clear relation between microstructure and macrostructure measures (; ), the picture that emerges in bilinguals is more complex. Some of the studies did not find any associations between these levels ( with trilingual narratives) or found them in only one of the languages (), while other studies found positive associations between linguistic measures and story quality measures (; ; ).

2.2. Form–Function Approaches in the Study of Bilingual Narratives

Following the pioneer study on the development of narrative abilities in various languages using the Frog story (), several studies of bilingual narratives adopted form–function approaches that cut across microstructure and macrostructure levels (e.g., ). This line of research examines functional domains that play a crucial role in achieving narrative coherence, such as reference (), temporality (), or evaluation (), to reveal language-particular versus language-general linguistic devices for expressing those functions (; ; ).

In a comparison of HL/Spanish and SL/Hebrew among heritage speakers of various ages, () showed that macrostructure was similar in both languages, but an analysis of form–function relations in the domains of connectivity, temporality, and reference maintenance showed that the use of morpho-syntactic forms in HL was affected by cross-linguistic differences in the systems analyzed. In structures with a similar language typology, such as null pronouns, forms and functions were similar in both languages. However, when systems differed, such as in aspectual morphology, bilinguals showed poor abilities to use forms as cohesive devices, both locally between adjacent clauses and globally between larger units in the story.

Reference has been widely investigated as a domain of form–function intersection. Various studies reported appropriate use of language specific strategies for character introduction and maintenance in languages with different referential systems, e.g., English and Italian (), while others showed that the use of referential forms is affected by language-specific constraints such as differences in marking definiteness, e.g., Hebrew and Russian (). In addition, form–function studies also showed greater similarity between the two languages of bilinguals for early acquired morphology, regardless of the length of exposure and proficiency measures (; ). This is not to say that proficiency measures do not count. In a study with young Spanish–English bilinguals, () argued that impoverished linguistic resources in the SL may have a detrimental effect on the ability to produce a well-organized account of the events and on the use of more complex forms of cohesion in the domains of reference and temporality, but less so on the ability to express evaluative functions. Similar conclusions were reached for the expression of causal relations in the stories of young sequential bilinguals in SL/Hebrew—having reached a minimal linguistic threshold seems a vital requisite to use forms as cohesive devices (). Thus, there is a combination of factors that may affect bilingual narrative production, including language typology, the forms and functions addressed, and variables such as age of exposure to SL and degree of proficiency.

The present study examines the form–function domain of causal relations, which is underrepresented in the research on monolingual and bilingual narratives. Section Causal Relations in Bilingual Narratives describes the conceptual grounds of causality embedded in the narrative and reports on recent findings with bilingual narratives. The operationalization of these concepts in the present study is detailed in Section 3.3 below.

Causal Relations in Bilingual Narratives

The expression of causal relations reflects the ability of narrators to organize the narrative content according to cognitive principles of episodic structuring, while choosing appropriate language forms as cohesive devices to create links within and between clauses (; ; ), as shown in example (1) above. Narrative events are produced more efficiently if they are represented as part of a causal chain, as proposed in the Causal Network model by () and (). Within this analytic model, goals motivate actions or attempts, attempts can physically cause an outcome or enable other actions or states that may subsequently result in another outcome. Similarly, outcomes can physically cause or enable other events, and both attempts and outcomes can bring about cognitive or emotional internal responses. To investigate the integration of macrostructure with microstructure in monolingual and particularly in bilingual narrative production, this model was originally adapted by (), (), and (, ) in studies with bilingual children at various ages, with Typical Language Development (TLD) and Developmental Language Disorder (DLD). These studies have shown unique patterns of language use to express causality in HL narratives.

In a longitudinal study with sequential bilinguals, speakers of different HLs acquiring Hebrew as a SL, () found that preschool children (ages 5–6) presented lower performance than Hebrew monolinguals on episodic components and causal relations between these components, particularly in scenes depicting complex motion events. After four years of exposure to the SL, only cohesive language (e.g., connectives) showed a different path of development in the two groups, at both preschool and school ages. Using the same picture-series stimuli, () examined the linguistic expression of episodic components and causal relations in the Hebrew narratives of Russian–Hebrew and English–Hebrew bilingual children aged 5–7 with TLD and DLD, as compared to their monolingual peers. The authors found no differences between monolingual and bilingual children with TLD in any of the study measures. However, the analysis of causal relations and their linguistic expression proved effective for disentangling typical bilingual development from language disorders (see also , ). The study showed that syntactic and referential strategies facilitated the expression of complex causal relations, thus establishing a link between microstructure and macrostructure. () showed that the fine-grained analysis of narrative skills, entailed in the analysis of causal relations, sheds light on the strengths and weaknesses of bilingual children above the more frequent story grammar approach.

Thus, unlike strictly linguistic measures of microstructure, the present study adopts a more exhaustive quantitative and qualitative methodology that considers narratives as a discourse platform integrating forms and functions as two interacting levels of knowledge. Studying two typologically different languages—Russian as HL and Hebrew as SL—will further contribute to understanding the effects of specific language features and cross-linguistic influence in bilingual narrative production. Against this background, the following research questions are proposed.

- Are episodic components and causal relations between these components comparable across HL/Russian and SL/Hebrew? Are these abilities affected by linguistic proficiency in both languages and age of exposure to SL?

- Is the production of causal relations affected by other study variables—specifically the production of episodic components and narrative microstructure measures in HL and SL?

- Which language forms are used for the expression of causal relations in HL/Russian and SL/Hebrew? Are these forms comparable across languages?

Following the studies mentioned above, we predict that proficiency profiles in each of the languages but not AoB will affect the production of episodic components (; ; ) and causal relations. Low proficiency in one of the languages may result in poor production of episodic components but may not affect the expression of causal relations, since narrators should be guided by cognitive abilities in narrative construction, paying more attention to overall coherence than struggling to retrieve specific language forms. Low proficiency in both languages of the bilingual is expected to affect the ability to express inferable causal relations because some of the core components of the episode may be missing (). High and balanced proficiency in both languages is predicted to render similar macrostructures in both languages (), but not necessarily similar expression of inferable causal relations, depending on the narrators’ ability to create cohesive links between events, beyond the mere description of content. In terms of linguistic expression, narrators in both languages are expected to use more lexical than grammatical forms for expressing causal relations. Language-specific cohesive forms are expected to occur in both languages. Narrative productivity measures (e.g., TNW) are expected to be related to the production of episodic components but not causal relations, while more complex measures (e.g., C-units) may positively correlate with both. The study is expected to reveal different profiles of emerging cohesion strategies, reflecting the interaction between linguistic and cognitive abilities while organizing discourse.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

Oral narratives were collected from 21 Russian–Hebrew typically developing bilingual children in both languages. The participants were drawn from a larger sample of children who participated in the project funded by the Israel Science Foundation (ISF 863/14). Selection criteria for current sample were age range (62–71 months, M = 67.48, SD = 3.05), typical language development, and a household where at least one parent spoke Russian at home daily and the child could hold a conversation on everyday topics in both Russian and Hebrew. Out of 21 children, 19 were born in Israel, one child was born in Russia and one in the US. All children came from families where both parents spoke Russian. Ten children reported that only Russian was spoken at home, and 11 children were said to speak both Russian and Hebrew.

To ensure typical language development, children’s language proficiency was tested in Russian and Hebrew. Since equal tests to assess language proficiency in Russian and Hebrew do not exist, the current research evaluated children’s proficiency in the two languages using standardized tests that have been previously tested in several studies (e.g., ) (see Section 3.2). Bilingual children’s linguistic performance should be tested using tests adapted for bilinguals or using monolingual tests while applying bilingual norms (e.g., ). Bilingual norms for both tests were calculated and have been tested in several publications in the lab led by the third Author. Using these bilingual criteria, raw scores were standardized using a z-score approach, and only children whose z-scores in at least one of the languages were within the age-appropriate local standards (more than −1.25SD) were included. In other words, only data from bilingual children with typical language development were included in the analyses.

In Israel, government-supported education starts at the age of three, and most children start attending kindergartens with Hebrew as the language of instruction and communication around that age. Before age three, children attend private daycare, and many parents choose a Russian-speaking daycare. In the current sample, most children (18 out of 21) were attending Hebrew-speaking kindergarten/preschool starting from age 3 years, and three children were reported to start exposure to Hebrew in an educational setting (daycare). By the time of the study, all children had been attending publicly supported preschools, where the language of instruction was Hebrew.

Children’s parents filled in parental questionnaire providing details about the child’s language history including age of exposure to SL and history of exposure to the two languages, patterns of language use at home, and parental concern regarding language development. Table 1 presents background information (age and AoB) and results of language proficiency tests (see Section 3.2) for all participants.

Table 1.

Participants’ background information.

To examine whether proficiency scores differed in Russian and Hebrew, paired sample t-tests were conducted revealing no significant difference between the languages, t(39.83) = 0.54, p = 0.59. This established a balanced and appropriate setting for comparing the narrative measures in both languages.

3.2. Materials and Procedures

Proficiency tests were administered in both languages. The Russian Language Proficiency Test for Multilingual Children () includes subtests for expressive (noun/verb naming, production of case and verb inflections) and receptive language (comprehension of grammatical constructions, nouns, and verbs). The Goralnik Screening Test for Hebrew () includes subtests for vocabulary, sentence repetition, comprehension, oral expression, pronunciation, and storytelling. Proficiency scores in each language were calculated using age-appropriate bilingual standards developed for Russian–Hebrew bilingual speakers ( for Russian; for Hebrew).

Narratives were collected in both languages, in a quiet area in the preschool using the 29-page wordless picture book, Frog, Where Are You? () that tells the story of a boy and his dog searching for their missing pet frog. Testing began with the presentation of the picture book and the instruction: “Here is a story about a boy, a frog, and a dog. I would like you to first look through the pictures, and then tell me the story as you look through the book a second time”. The children’s narratives were audio-recorded for transcription purposes. The research assistants were native speakers of the language of the session, Russian or Hebrew. All research assistants were graduate students in Education or Linguistics with training in how to communicate with young children and how to elicit narratives. Children were randomly assigned to Russian-first or Hebrew-first condition, and the sessions were held at least one week apart. As shown in the Results Section, this had no effect on the performance of the children.

All narratives were transcribed using CHAT conventions () by trained research assistants who were native speakers of Russian or Hebrew. The division into utterances was based on a C-units approach (). A C-unit consists of one main clause along with any dependent phrase(s) or clause(s). Narratives were then analyzed for microstructure in terms of total number of word tokens in the story (TNW), number of different word tokens (NDW), number of C-units, and mean length of C-unit (MLCU).

3.3. Units of Analysis

The form-function approach in the domain of causal relations was operationalized at three levels—episodic components, causal relations, and cohesive language strategies. The units of analysis at these levels are described below.

3.3.1. Episodic Components

Following the model proposed by () and replicated in () using the Frog story, a set of episodic components triggered by goal-directed actions was defined—including a setting that introduces the characters and surrounding circumstances at a certain place and time; an initiating event and a problem that trigger the episode; a goal that leads to an attempt; and an outcome that may lead or not to other actions. In addition, internal responses may occur as reactions to the events within the episode. A total of 41 episodic components were coded, within eight episodes that comprise the story. For example, Episode 1 includes two settings (boy and dog are sleeping, boy and dog wake up), an initiating event (frog escapes from jar), a problem (boy and dog see that frog has gone), a purposeful attempt (search frog inside the home), two outcomes (haven’t found frog, dog’s head got stuck inside jar), and an internal response (e.g., the boy and the dog were sad). Episodes varied in number and type of components and were coded at two levels. At level one the components are directly connected to the superordinate goal—to find the frog, while at level two they are represented at a subordinate level that is not directly connected to the main plot (e.g., the bees flying out of the beehive; the dog running away from the bees). Each component scored 1 point if it was mentioned explicitly and 0 if it was not mentioned. The percentage of components mentioned in each episode was then calculated.

3.3.2. Causal Relations

Episodic components represent individual events or states; however, their successful use depends on how important an event is to achieve the character’s goal, as well as how it relates to the causal network (). Following the causal network approach, a total of 32 causal relations (12 motivational, 15 enabling, and 5 psychological relations) were coded across clauses (). Overall, 21 relations at level 1 and 11 relations at level 2 were coded (see Section 3.3.1 above). The Frog story is a canonical multi-episodic story where a recurrent link exists between the protagonists’ goal and their attempts to find the frog until the final positive outcome, so that many causal relations can stem from the first goal (). Coding of causal relations is further illustrated in excerpt (2) taken from a story told by a girl aged 5 years 11 months, in Russian. The translated excerpt is divided into clauses marked by [square parentheses] followed by the type of episodic component in small letters. The age of the narrator (in months) and language of the session are presented between square brackets in all the examples below.

- (2)

- malčik s sobakoj prosnulis’ i uvideli čto netu v banke ljaguški. oni stali iskat’ ejo malčik v sapogax a sobačka v banke. tak banka na sobake zastrjala. tak mal’čik ejo pozval no ljaguška ne prišla [70, Russian]‘the boy and the dog woke up]SET and Ø saw that the frog was not there]PROB. they started searching for it]G+ATT the boy in the boots and the dog in the jar]ATT. and the jar was stuck on the dog]OUT. and the boy called the frog]G+ATT but the frog did not come]OUT.’

In excerpt (2), 6 causal relations were coded. The setting ‘woke up’ enables the main protagonists to discover that the frog was missing. This problem subsequently motivates three search attempts, which further enable the outcomes related to the dog (jar stuck on dog) and to the frog (frog did not come). Thus, the scores for causal relations should capture the level where the child conceptualizes the connection between the episodic components. These relations can be established by means of more general, universally driven semantic connectivity, and by language-specific grammatical and syntactic forms, as described in the next Section.

3.3.3. Linguistic Forms

Russian and Hebrew are typologically different languages, with Russian being a Slavic language from the Indo-European family, and Hebrew a Semitic language. Both languages have rich inflectional morphology but only Russian marks case (). Verbs are marked for person, number, gender, and tense in both Russian and Hebrew () but only Russian marks perfective versus imperfective aspect (). Language-specific features are further detailed in the Sections below, in presenting the three major categories of cohesive devices analyzed in the present study.

- Lexical cohesion. Most of the causal relations between two or more situations are not explicitly marked but construed in semantic connections within the domain of real-world knowledge (). In the context of stories, these real-world connections may represent goal-directed actions that enable positive or negative outcomes such as searching for the frog may lead to finding~not finding it (; ; ). Some of these connections involve a higher degree of abstract reasoning as in the situation ‘boy and dog sleeping’ enabling ‘frog escaping’—where the former implies an unconscious state of mind. Lexical chains can also represent motivational or psychological relations, such as ‘disappearing leads to searching’ or ‘bees flying out of beehive lead to dog getting scared’. In all these cases, the causal connection can be inferred in terms of an underlying script or world knowledge and is generally represented by the verb and the actors involved in the scene ().

Lexical cohesion should be similar in both languages, except for typological differences related to the verbal system. One difference lies in encoding motion events (). Russian—a satellite-framed language—encodes manner of motion through a rich collection of motion verbs, which are obligatory in most contexts (). Verbs like lezt’ ‘climb’, begat’ ‘run’, brosit’ ‘hurl’, and prygat’ ‘jump’ can be combined with path particles (satellites) as verb prefixes to provide more specific information (e.g., vy-skočila, vy-prygnula ‘out-jumped’). Moreover, Russian grammaticizes directionality by stem variation in highly frequent motion verbs, such as the pair bezhat’ ‘run in a single direction’ and begat’ ‘run around’ (). Hebrew as a verb-framed language typically encodes path in monolexemic verbs (e.g., nixnas/yoce/ole/yored ‘enters/exits/ascends/descends’), while manner of motion is optionally expressed by other means such as adverbs—which are similar in both languages. A second difference regards morphological distinctions of aspect in Russian verbs, using a system of prefixes to distinguish between perfective aspect to denote completion and imperfective aspect for incomplete, ongoing actions, e.g., lez-zalez ‘climbed’ (see ).

- Syntactic cohesion. The use of inter-clausal connectors provides a window to the ability of narrators to arrange the flow of information in discourse and to create temporal and causal links (; ). The present analysis considers two main strategies of syntactic connectivity between clauses—where a clause refers to ‘any unit that contains a predicate which expresses a single situation, i.e., an activity, an event or a state’ ():

- (a)

- Coordination: Two or more clauses linked by the conjunctions ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘but’, and semantically related by sequence, cause, location, or contrast (). In Russian and Hebrew coordinated clauses may contain an overt lexical, a pronominal, or an elided subject ().

- (b)

- Subordination: Two or more clauses connected in a tighter ‘package’ (), including complement, relative and adverbial clauses. These connectivity strategies are similar in Russian and Hebrew except for differences in the relative pronouns in relative clauses (e.g., kotoryj ‘that’), which are marked for gender, number, and case in agreement with the noun in Russian.

- Referential cohesion. The ability to clearly maintain and reintroduce the reference to the entities in the story (e.g., protagonists, locations) is crucial for the interpretation of causal relations (; ). For instance, the motivational relation between the event of ‘frog has escaped’ and ‘going to search’ is enforced by an unambiguous referential link between ‘the frog’ who has previously escaped and the search motif. Thus, in the realm of the story, the inference of causal chains will depend on the anchors created between actors, patients, and locations. In this context, forms of referential cohesion included lexical noun phrases, and pronominal and zero forms (). Russian, as well as Hebrew, allows null anaphora, but under certain conditions: in present and future and in the past 1st and 2nd person in Russian (), and in past and future 1st and 2nd person in Hebrew (). Zero pronominal subjects in the past 3rd person are not allowed in isolated clauses but may appear in same subject coordinated clauses in both languages.

Russian and Hebrew differ in the use of case marking in nouns and pronouns. In Russian, these are marked by a rich inflectional case system morphology, which conveys the relationship between the different constituents in a sentence (). For instance, the noun ljaguška ‘frog’ is marked for NOM case in the clause ljaguška vyšla ‘frog-NOM jumped’ but will appear in the ACC case in the clause oni zvali ljagušku ‘they called frog-ACC’. While Hebrew has a differential system of pronouns for case purposes, it does not have morphological case suffixes on nouns; instead, case is only marked by the prepositions et for accusative definite nouns and šel for the genitive (). Likewise, some arguments expressed by cases in Russian (e.g., malčik s sobakoj prosnulis i uvideli čto netu v banke ljaguški ‘boy.NOM with dog.INSTR woke-up. and saw that not in jar.PREP frog.GEN’) are usually expressed by prepositions (mostly bound morphemes) in Hebrew.

3.4. Reliability

Twenty percent of the narratives were randomly chosen and analyzed in Russian and Hebrew for episodic components and causal relations at both levels by two additional coders. A reliability coefficient was obtained by running Interclass Correlation (ICC) reliability analyses (). In Russian, the ICC coefficient was 0.94 for episodic components, 0.96 for level 1 relations, and 0.91 for level 2 relations. In Hebrew, the ICC coefficient was 0.79 for episodic components, 0.90 for level 1 relations, and 0.77 for level 2 relations. These values indicated excellent/good reliability.

3.5. Analysis

The analyses were conducted in R (). To answer Research Question 1, Linear Mixed Models (LMM) analysis was performed with Language (Russian/Hebrew), Proficiency in each language and their interaction as the fixed factors and Participants as the random factor. To test whether episodic components were affected by Language, and whether children’s success of production varied with respect to Episode, a LMM analysis was performed with Episode, Language, and their interaction as the fixed factors. The dependent variable was the percentage of episodic components, calculated as the number of components divided by the maximal number of components in the story. Next, to test whether causal relations were affected by Language and Proficiency, a LMM analysis was performed with Episode, Language, and their interaction as the fixed factors and Participant as the random factor. In this analysis, the dependent variable was the percentage of causal relations, calculated as the number of relations at each level divided by the maximal number of relations at that level, as per coding scheme. In all analyses, age of exposure to SL was tested as a potential covariate. lme4 package was used to run LMM analyses ().

As a basis for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of episodic components, causal relations, and language forms, a comparison of narrative microstructure measures is presented in Table 2, including total number of words in the story (TNW), number of different words (NDW), C-units, and mean length of C-unit (MLCU). All microstructure measures were calculated excluding hesitations, repetitions, and false starts. Code-switches were not excluded, but these were rare and amounted to less than 1% of the overall number of words.

Table 2.

Microstructure data by language.

Paired Samples t-tests revealed no significant differences between HL and SL for TNW, t(20) = 1.62, p = 0.12, NDW, t(20) = 0.19, p = 0.85, and C-units, t(20) = 0.74, p = 0.47, but children had a shorter MLCU in HL/Russian than in SL/Hebrew, t(20) = 2.19, p = 0.04.

To ensure that the order of narrative production in each language did not affect performance, we first compared the impact of production order (Russian-first/Hebrew-first) on the percent of the main measures and revealed no significant differences: for episodic components, t(39.99) = 0.73, p = 0.47, for relations level 1, t(37.85) = 0.58, p = 0.56, and for relations level 2, t(37.85) = 0.58, p = 0.56.

4. Results

The Results Section starts with the quantitative results (Section 4.1). As an answer to the first research question, findings regarding episodic components are presented in Section 4.1.1, followed by the causal relations analysis in Section 4.1.2. Section 4.1.3 addresses the second research question employing a correlational analysis among the study variables. Finally, qualitative results on language forms are presented in Section 4.2.

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Episodic Components

To answer the first research question, we examined the effect of Language (Russian/Hebrew), Proficiency, and Age of exposure to SL on the production of episodic components and causal relations. Table 3 shows the mean number of episodic components and their percentages out of 41 components, and the range of minimal and maximal production rates in HL/Russian and SL/Hebrew.

Table 3.

Mean, SD, min, and max of episodic components in HL and SL.

The LMM analysis revealed a significant effect of Language, χ2 = 4.55, p = 0.03, and of Proficiency, χ2 = 9.75, p = 0.002, but no interaction of Language and Proficiency, χ2 = 0.27, p = 0.60 on the production of episodic components. For Language, children produced significantly fewer episodic components in HL/Russian than SL/Hebrew. For Proficiency, higher proficiency was associated with a higher percentage of episodic components in both languages. The effect of AoB was not significant, χ2 = 0.02, p = 0.89. The final optimal model included Language and Proficiency as fixed factors. Overall, the model explained 56% of the variance of the dependent variable, and 24% were explained by the fixed factors alone. Table A1 in Appendix A shows the results of Likelihood Ratio Tests for each fixed factor.

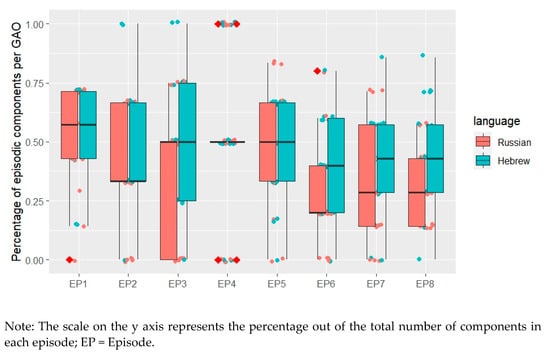

For a more in-depth analysis of episodic complexity, we examined the production of the components in each of the eight episodes identified in the narrative, as shown in Figure 1 (100% reflects the maximal number of components in each episode).

Figure 1.

Percentage of components within each episode.

The pattern in Figure 1 shows that children produced more components in the first three episodes compared to episodes 6–8, and this is true for both HL and SL. The data in Figure 1 also show that episodes 6–8 were more challenging in HL than in SL. A LMM analysis testing differences in the percentage of components within each episode in HL and SL revealed a significant effect of Episode, χ2 = 27.88, p < 0.001, and of Language, χ2 = 7.53, p = 0.006, but no interaction of Episode and Language, χ2 = 7.09, p = 0.41. For the effect of Episode, post hoc analyses with Tukey corrections revealed that Episode 1 was produced with significantly greater success than Episode 6 (p = 0.001), Episode 7 (p = 0.02), and Episode 8 (p = 0.03) in both languages. In addition, Episode 4 was produced more frequently than Episode 6 (p = 0.01) in both languages. Other differences were not significant. For the effect of Language, like the analysis above, the percentage of components per episode was lower in HL/Russian than in SL/Hebrew, and this result applies to all episodes collapsed. The optimal model included the fixed factors of Episode and Language. Overall, the model explained 19% of the variance of component production, where the fixed factors accounted for 10%. Table A2 in Appendix A lists the results of Likelihood Ratio Tests for each fixed factor.

4.1.2. Causal Relations

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimal, and maximal values) of raw frequencies and percentages of causal relations at levels 1 and 2 (separately and collapsed).

Table 4.

Causal relations level 1 and 2.

The LMM analysis for causal relations level 1 revealed a significant effect of Proficiency, χ2 = 27.88, p < 0.001, but no effect of Language, χ2 = 1.05, p = 0.31, no effect of AoB, χ2 = 0.02, p = 0.87, and no significant interactions. Similar effects were found for causal relations level 2, with a significant effect of Proficiency, χ2 = 27.88, p < 0.001, but no difference between the languages, χ2 = 1.05, p = 0.31, no effect of AoB, χ2 = 0.02, p = 0.87, and no significant interactions. For the overall number of relations (levels 1 and 2 collapsed), a significant effect of Proficiency also emerged, χ2 = 11.83, p < 0.001 (see Table A3 in Appendix A for the results of the Likelihood Ratio Tests for each model).

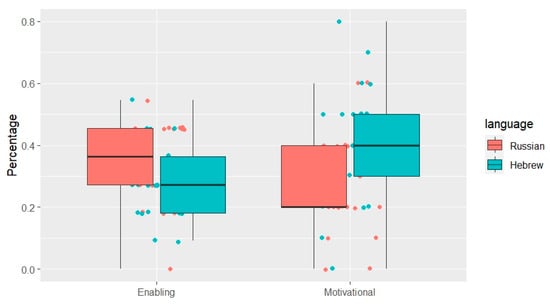

To explore which causal relation type—Enabling or Motivational (both at level 1)—was expressed more frequently in both languages the percentage of each type was calculated, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Motivational and Enabling relations in each language.

Figure 2 shows that children produced more Enabling but fewer Motivational relations in HL/Russian than in SL/Hebrew. An LMM analysis was applied to test the effect of relation type (Enabling/Motivational), Language, Proficiency, and their interactions, with Participants as a random factor. We were interested in interactions by relation type since we aimed to explore whether fixed factors impact the two relations similarly. The analysis revealed a significant interaction of Type*Language, χ2 = 9.80, p = 0.002, and a significant effect of Proficiency, χ2 = 5.66, p = 0.002 on the relations expressed. Post hoc analyses of the interaction with Tukey corrections revealed that Motivational relations were produced less frequently in HL/Russian than in SL/Hebrew (p = 0.006), but Enabling relations were not significantly different by language (p = 0.23). Table A4 in Appendix A includes all Likelihood Ratio Tests. The final model explained 36% of the variance of relations use and 21% was explained by the random factor.

4.1.3. Relations between Episodic Components, Causal Relations, and Productivity Measures

Research question 2 was addressed by running correlation analyses to test for possible relations between narrative microstructure measures, and between percentages of episodic components and of causal relations in each language. Table 5 shows the results of Pearson correlation analyses in HL and SL.

Table 5.

Correlation analyses between narrative microstructure measures, percentage of episodic components, and percentage of causal relations in HL/Russian and SL/Hebrew.

Table 5 shows different patterns of the relationship between microstructure measures, episodic components, and causal relations in the two languages. Overall, a higher number of significant correlations emerged in SL/Hebrew (18 correlations) than in HL/Russian (9 correlations). The production of episodic components was related to TNW, NDW, and MLCU in SL but not in HL. For causal relations level 1, they were related to a higher number of episodic components only in HL; and to C-units and TNW in SL. Relations level 2 were associated with three productivity measures in SL (C-units, TNW, and NDW) and only with NDW in HL. For the total percentage of relations, C-units, TNW, and NDW were associated with the production of relations only in SL.

4.2. Qualitative Results

In the following Sections, we show qualitative analyses of the linguistic structures used to express causal relations in HL/Russian and SL/Hebrew. Section 4.2.1 presents a fine-grained analysis of the structures used to mention the core episodic components at the onset of the story (within episode 1), which are crucial for inferring various enabling relations—the boy and dog sleeping (Set1) enables the frog to escape (IE); waking up (Set2) enables them to see that the frog had escaped and is no longer in the jar (Problem). Section 4.2.2 describes the role of lexical, syntactic, and referential cohesion in expressing enabling and motivational relations, by means of illustrative examples in both languages. In Table 6, language forms are presented first in HL/Russian and then in SL/Hebrew, separated by a hyphen (-). Variations of forms in the same language are separated by a slash (/). In all the examples below, gloss appears only when relevant to the linguistic domain that is presented. The translated version appears between ‘’. The symbol * indicates morphological errors and [CM] means code-mixing between the languages.

Table 6.

Linguistic forms used to express episodic components in Episode 1 in HL/Russian and SL/Hebrew in % out of number of children.

4.2.1. Linguistic Encoding of Episodic Components in Episode 1

The comparative analysis shown in this Section focuses on verbs, adverbs, prepositional phrases, syntactic strategies of inter-clausal connectivity, and morpho-syntactic forms (e.g., case markers) used to encode the episodic components at the onset of the narrative. The analysis shows the emergence of language forms to facilitate the creation of causal relations.

Table 6 shows the language forms used in the two languages to express the episode components at the onset of the story. The total number of verbs used for each component represents the frequency of production of that component. To encode SET1 more than three-quarters of the children in both languages used the specific verb spali-yašnu ‘slept’. In Russian, children adequately marked this verb mostly in the imperfective aspect to indicate a durative action (e.g., spal sleep.PAST.MASC.IMPERF). In cases where children used aspectual verbs (e.g., ‘go to sleep’), these were correctly marked in the perfective or imperfective in HL, according to their function (e.g., pošol spat’ go.PAST.MASC.PERF sleep.INF.IMPERF, legli spat’ lay-down.PAST.PL.PERF, zasnuli go-sleep.PAST.PL.PERF, pospali sleep.PAST.PL.PERF). Occasionally, an imperfective form was used with an inherently punctual verb to contrast between a continuous and a punctual action, as in the utterance kogda mal’cik ložilsja spat’ ljaguška tixon’ko ubežala ‘when the boy lay-down.PAST.MASC.IMPERF sleep.INF frog quietly escape.PAST.FEM.PERF’.

To encode the IE in HL, nearly half of the children used manner verbs combined with path morphology (e.g., vybralas ‘climbed out’), as guided by the satellite-framed typology, while in SL they used either a path or a manner of motion verb. The specific verb ‘escaped’ was less frequent in SL/Hebrew compared to Hebrew monolingual narratives at this age (). The general verb ušla/pošla-halxa ‘went-away’ was used by 33% of the children in both languages. In HL, all children marked motion verbs in the perfective form, which was appropriate for this punctual event, with various prefixes expressing path (vylezla/vyprygnul/vyšla/vybralas ‘got out/jumped out/went out’) or directionality (ubežala ‘ran away’). Imperfective forms were used by only two children who mentioned the desire of the frog to escape (e.g., xotela ujti wanted.PAST.FEM.IMPERF escape.INF). Thus, a salient event triggered a rich variety of morphological forms in Russian. The explicit manner of motion by use of adverbs was quite impressive considering the young age of the narrators, as illustrated in excerpts (3) and (4) in Russian and Hebrew, respectively.

- (3)

- kak-to noč’ju raz on leg spat’ a ljaguška tixon’ko vybralas’ iz banki. [66, Russian]‘one night he lay.PAST.MASC.PERF sleep.INF.IMPERF and frog.NOM quietly climb-out.PAST.FEM.PERF from jar.GEN’.

- (4)

- hu halax ba-adinut ba-adinut ve- az kafac me-šama ka-ze hop hop hop hop hop hop hop [71, Hebrew]‘he left.PAST.MASC softly softly and then jumped.PAST.MASC from there like this hop hop hop hop hop’.

Besides the use of adverbs, these examples show various expressive means for manner and path of motion (in Russian), and a combination of a general path verb ‘left’ with a manner of motion verb ‘jumped’ in Hebrew to encode the motion (underlined).

The ‘waking up’ event in SET2 was less frequent than the ‘sleeping’ event in SET1, as shown in the table above. In Russian, most children marked this verb in the perfective aspect to indicate punctuality (e.g., prosnulsja wake.up.PAST.PERF). To mention the problem, more than 70% of the children in both languages used the perception verb ‘see’ (uvidel čto net ljaguški see.PAST.MASC.PERF that NEG frog.GEN), which implies awareness of the missing frog.

Children used various syntactic structures in both languages for connecting purposes. The ‘sleeping’ event was embedded in a subordinated clause of time or followed by a coordinated clause to highlight the ‘escaping event’. A similar trend was found in SET2 for the purpose of foregrounding the problem that triggers the plot (e.g., a potom kogda oni vstali, uvideli čto ljaguški net ‘and then when they woke up, they saw that there was no frog’). Reference to the missing frog after the verb ‘see’ was made by use of a specific end-state verb (e.g., hu raa še ha-cfardea neelma ‘he saw that the frog disappeared’), a path or manner verb ‘went’ or ‘jumped’, which was inappropriate here; or a verbless negated state (e.g., uvideli čto netu v banke ljaguški ‘saw that there was no frog in the jar’). Less than 30% of the children mentioned the time of the events—night and morning—and even fewer children referred to the location of the frog in the jar as the source of motion or to identify its previous location. In Russian, when the location was mentioned, a proper use of case was registered (a on vylez iz korobki and he climb-out.PAST.MASC.PERF from box.GEN). All in all, the percentages of forms in both languages reflect the central role of verbs in expressing components, followed by syntactic constructions of different types, and lastly by reference to locations. It is interesting to see how adverbs of time and manner were used at this early age to enhance causal links. The role of lexical, syntactic, and referential strategies in expressing causal relations is further described in the next Section.

4.2.2. Language Forms for Expressing Enabling and Motivational Relations

This Section presents the linguistic strategies used by children as cohesive means to link episodic components via enabling and motivational relations. Lexical cohesion was central to expressing inferable causal relations throughout the story, as shown in Table 6 above, with regard to the first episode. Two excerpts produced by one child in Russian (5a) and in Hebrew (5b) illustrate this.

- (5a)

- kogda u kogda kogda kogda oni za kogda pospali značit ljagušonok ušel mi-ha mi-ha mi-ha *pumpija [CM] kogda kogda on prosnulsja značit on uvidel na ego sapogax na ego no na sapogax. potom on potom on iskal et [CM] [62, Russian].‘when they sleep.PAST.PL.PERF then froggy leave.PAST.MASC.PERF from grater [CM]. when he wake up.PAST.MASC.PERF then he saw.PAST.MASC.PERF on his boots then he search.PAST.MASC.IMPERF* the.ACC [CM].’

- (5b)

- ve ve-cfarde’a yaca. ve- axar~kax yeled yašen. axar-kax yeled hit’orer raah *mah eyn *et ha- cfarde’a. hu xipes ba- na’alayim šelo. axar~kax hu xipes ba-*pumpiyah. ve- hem himšixu lexapes [62, Hebrew]‘and frog leave.PAST.MASC and afterwards boy sleep.PAST.MASC. afterwards boy wake up.PAST.MASC saw.PAST.MASC *what (there) is-no *ACC the frog. he searched in his shoes. afterwards he searched in-the *grater. and they continue.PAST.PL search.INF.’

In both Russian and Hebrew excerpts, the child used various lexical chains for expressing enabling and motivational relations: the chains ‘left~no frog’, ‘slept~woke up’, and ‘woke up~saw’ create enabling relations, and the chains ‘saw~no frog~searched/continued to-search’ create motivational links. In these examples, lexical chains are complete in Hebrew, but less so in Russian. In Hebrew, the use of the specific verb ‘search’ following the immediately anterior antecedent ‘the frog’ implies a clear reference to the searching goal. In Russian, the lexical chain ‘saw~no frog~searched’ is broken. Even though the narrator used the verb uvidel ‘saw’ she did not mention the frog as the object of the search but she used a prepositional phrase ‘on the boots’, which can be interpreted as a searching theme. Interestingly, she finally uses the relevant lexical item iskal ‘search’ but without mentioning the searching goal.

In the Hebrew example, the enabling relation between ‘the boy and the dog sleeping’ and ‘the frog leaving’ is hindered because the events are presented in a reverse order ‘left~sleep’. In HL/Russian, the child used the perfective prefix po- with the verb pospali ‘sleep’ although it would be more appropriate to use the word zasnuli ‘fall asleep’ with the perfective (as described in the previous Section). Nonetheless, morphological errors do not seem to hamper the strength of lexical chains.

Lexical chains were required to express the enabling relation between the recurring searching attempts and the outcomes of the search—six negative outcomes (the frog was not found) and one final positive outcome at the end of the story (finding the frog). Some of the chains used in Hebrew were xipsu~lo macu ‘searched~did not find’, coek~lo baa ‘shouts~doesn’t come’, histaklu~rau ‘looked~saw’, and hecicu~rau ‘peeked~saw’. Various lexical chains were used in Russian, too, as illustrated in the following examples.

- (6)

- a potom on išjil a on ne videl ejo [71, Russian]‘and then he search.PAST.MASC.IMPERF but he not see.PAST.MASC.IMPERF her’.

- (7)

- kogda oni e e i kogda oni byli v lesu oni zvali ljaguški aval’ [CM] oni ne našli [69, Russian]‘when they and when they were in forest they call.PAST.PL.IMPERF (the) frog but they not find.PAST.PL.PERF’.

Excerpts (6) and (7) show that verbs denoting recurrent, ongoing search and negative stative outcomes (e.g., ne videl ‘didn’t see’), as well as the ongoing action ‘called’, were correctly marked in the imperfective aspect, whereas the punctual verb ‘find’ was marked in the perfective aspect.

Syntactic cohesion was less frequent than lexical cohesion in children’s narratives and it was dedicated to specific scenes in both languages. At the onset of the story (Episode 1), syntactic cohesion served for backgrounding information against plot advancing events (e.g., a kogda mal’čik spal ljaguška ushla ‘when the boy was sleeping the frog left’); this was shown in Section 4.2.1. This same subordinated structure was used in excerpt (5a) above, with the temporal conjunction kogda ‘when’, to further enhance the lexical chains ‘slept~left’ and ‘woke up~saw’, which convey the enabling relation. In excerpts (3), (6), and (7) above, the use of coordination created a tighter link between the situations ‘slept~left’ and ‘search~didn’t see’. The use of code-mixing to encode the conjunction ‘but’ in (7) further showed that syntactic cohesion is transferable across languages. Syntactic cohesion was also used by some children in other specific scenes, as illustrated in the next excerpts from Russian and Hebrew narratives, which describe the bees’ scene, where the use of coordination in (8) or subordination in (9) forms enabling and motivational links.

- (8)

- a potom sobaka vot uronila ulej-i vse muxi za nej za nej letali [68, Russian]‘and then dog.NOM dropped beehive.ACC and all flies.NOM after her were flying’.

- (9)

- ve-ha-klavlav rac ve-ha-dvorim axaro (cf. axarav] *biglal hu hipil et ha-kaveret še lahem [71, Hebrew]‘and the doggy ran and the bees after-it *because (cf. because that) he threw beehive of-them (= their beehive)’.

Two other scenes were prone to include syntactic cohesion. One was the scene with the deer picking the boy up on its antlers, which offered multiple opportunities to link action with mindful perspectives about the delusive branches. Another scene was the highpoint before the final positive outcome, when the boy asked his dog to be quiet when hearing a sound, which may hint at the imminent frog. This is illustrated in excerpts (10) and (11) in Russian and Hebrew below.

- (10)

- on zalez na olenji roga kak budto eto vetki i on podnjal ego na rogax svoix [71, Russian]‘he climbed on deer.POSS.ACC antlers.ACC as-if these (were) branches.NOM and he lifted him on his antlers’.

- (11)

- ve- az ha-kelev navax aval ha-yeled amar lo “šeqet” ki šamah ulay ha-cfarde’a šelanu. az cariyx lihiyot be-šeqet še-hem loh yefaxdu *mimenu [69, Hebrew]‘And then the-dog barked but the boy told him ‘husshh’ because there may be the-frog of-ours- (=our frog), so (one) has to-be quiet so-that they will-not be-afraid *of-us’.

In all the examples above, the syntactic conjunctions mark an explicit connection between the reasons that motivate or enable actions. These reasons or circumstances are not directly perceived in the pictures, but they make actions understandable from the perspective of the actor.

Finally, referential cohesion by means of unambiguous use of pronouns or full NPs was particularly important for expressing the search motif. Through the seven searching episodes with negative outcomes until the final positive outcome, reference to the missing frog was crucial for global coherence (e.g., they searched for the frog, but they did not find it). Out of 64 possible references to the frog in the first seven episodes, children made clear reference to the frog as the object of the search in 55% and 54% of the cases in Russian and Hebrew narratives, respectively. Full nouns were used in most cases (e.g., malčik pozval no ljaguška ne prišla boy.NOM called but frog.NOM did not come), followed by pronouns (e.g., šli ejo iskat’ no ne našli ejo ‘went her-ACC to-search but did not find her-ACC), or by null pronouns when the reference was inferred from the context (e.g., i potom oni zvali no ne bylo ‘and then they called but (she) is not’).

In the final positive outcome, more than 85% of the children in both languages used a noun to refer to the frog(s) and the rest used a pronoun. As mentioned above, lexical chains were the main strategy used to express these motivational and enabling relations throughout the searching episodes. However, when less specific verbs were used (e.g., look, shout, call), the lexical link remained unclear unless the frog was unambiguously mentioned as the object of the search (e.g., ‘shouted where is the frog’).

5. Discussion

The present study focused on the expression of causal relations in a group of preschool bilingual children, speakers of Russian as Heritage Language (HL) and Hebrew as Societal Language (SL). Causal relations allowed us to capture the ability of children to integrate between the macro-level of organizing events into coherent episodes and the micro-level of language use (; ; ). The study adopted quantitative and qualitative methods, in line with form-function, cross-linguistic approaches in narrative research. The discussion below starts with the production of episodic components and causal relations, with reference to the effects of proficiency and AoB (5.1). This is followed by a discussion on the correlations across narrative variables (5.2). Finally, Section 5.3 addresses qualitative findings on the use of linguistic forms from a cross-linguistic, discourse perspective.

5.1. Episodic Components and Causal Relations

The analysis of episodic components reflects the most rudimentary level of structuring the narrative by looking at how static, visual stimuli are reflected in language. The current results show that general language proficiency was positively related to the ability to mention episodic components in both languages, as previously reported for different heritage languages (e.g., ; ; ). To convey the story plot, children need a certain level of proficiency, which involves lexicon and morpho-syntax. However, the specific level of proficiency required to successfully convey macrostructure has been disputed (e.g., ; ). The impact of language proficiency on narrative macrostructure in bilinguals is complicated by such exposure measures, as Age of Onset of Bilingualism (AoB). It was expected that later exposure to SL would yield a better performance in HL and vice versa, but this was not corroborated in the present study. This may be attributed to the small size of the group or to their narrow age range, in the sense that AoB was not a differentiating factor between participants.

For cross-language differences and contrary to our expectations, children produced fewer episodic components in the HL than in the SL, although proficiency scores did not differ in both languages. This finding was not in line with previous studies that reported similar macrostructure across languages, particularly in balanced bilinguals (; ; ). The higher number of episodic components in SL/Hebrew may be related to richer literacy experiences and communicative interactions at preschool in SL/Hebrew than in HL/Russian, such as peer talk, pretend play, book reading, and storytelling (; ). Previous studies reported an advantage for the SL in macrostructure, but this was true for older children who gained more proficiency in the SL after the first school years (e.g., ).

It is possible that the elicitation task used in this study—the Frog story picture book—was more demanding for preschool children than the series of pictures used in MAIN since the former is longer and more complex in episodic structure (). Nonetheless, the analysis of story complexity showed that children produced nearly half of the components, which seems higher than the percentage reported for the same ages in studies using MAIN (). This suggests that longer stories provide more opportunities for children to express narrative content, or that narrating picture books resembles more communicative, pragmatic tasks for children at this age, but these claims need further support. Results also showed that the first episodes were richer in components than the last episodes, replicating findings for monolinguals at this age (see ). This may be explained by perceptual saliency, complexity of the scenes, and story length (; ).

The analysis of episodic complexity revealed differences by language, such that the number of components per episode was higher in the SL/Hebrew than in the HL/Russian, in contrast with previous studies reporting similar story complexity across languages in the narratives of young children (e.g., ). As mentioned above, better performance in Hebrew can be attributed to increasing literacy experiences in Hebrew-speaking preschool settings (), but also to how complexity was measured here. Considering the whole GAO (goal–attempt–outcome) as the maximal unit of episodic completeness might be too challenging for preschool bilinguals. Thus, further studies are needed to understand how the episode develops into larger units using various measures (e.g., MAIN measures of component combinations) with different narrative tasks. Previous studies analyzed the types of components separately, which is a good option to understand the saliency of certain components over others (see MAIN measures of component combinations in ). However, in the Frog story, recurrent goals and negative outcomes are mostly left implicit (; ), while this is not so for the stories used in MAIN, suggesting that stories differ in terms of which components are more important for global coherence.

Causal relations captured the ability of children to connect between the episodic components in creating unified discourse units, already at preschool, when processes of discourse construction are still emergent. Causal relations, like episodic components, were affected by linguistic proficiency, irrespective of a specific language, but not by AoB. However, unlike episodic components, the overall percentage of causal relations was similar across the two languages. The two recent studies of causal relations performed within bilinguals found cross-language similarity, too (; ). It has also been found that causal relations were similar in monolinguals and bilinguals after the latter reached a minimal proficiency threshold in SL (). Other studies found that performance on measures of causal relations could disentangle bilinguals with TLD from those with DLD (e.g., ). These findings together indicate that the analysis of causal relations may be complementing other macrostructure measures in a way they target narrative abilities from a broader perspective of cohesion and coherence early in development. This perspective may be less biased by knowledge of a specific language and may be supported by conceptualization abilities that transfer from one language to the other.

Further analyses that looked at types of causal relations revealed a different distribution of motivational and enabling relations by language, such that enabling relations were more frequent in HL/Russian and motivational relations were more frequent in SL/Hebrew. In this story, the expression of motivational relations demanded a specific verb of searching and a specific reference to the lost frog. It might have been more difficult for heritage speakers to retrieve these words in HL or to keep track of the search motif across the episodes. Instead, enabling relations were higher in HL than in SL, hinting at more local constraints for their expression (; ).

5.2. Relations between Narrative Measures

Correlation analyses revealed quantitative and qualitative differences across Russian and Hebrew. Total number of words and denser stories in terms of C-units and lexical diversity were associated with the production of episodic components in SL/Hebrew but not in HL/Russian. Thus, the production of episodic components in HL may be less dependent on measures of language skills within the narrative, as found in previous studies (). Looking at narratives produced by trilingual children, () found no correlations between macrostructure, NDW, NTW, or syntactic complexity. They concluded that language interaction in the brain, together with language internal and external factors may be affecting bilingual performance in complex and unpredictable ways. In line with the rationale of this study, this finding suggests that to understand the mechanisms that relate the macro- and micro-levels of narrative production, it may not be enough to perform correlations between measures at these levels but rather utilize measures that assess these two levels in interaction.

Surprisingly, correlations looked different when considering causal relations as a variable. Level 1 causal relations correlated with number of episodic components in HL, but only with syntactic complexity and lexical diversity in SL. Level 2 relations correlated only with lexical diversity in both languages. The total percentage of relations was associated with narrative microstructure measures only in SL. These findings suggest that different types of knowledge may be activated for expressing causal relations in each language. While children use higher syntactic complexity and language productivity to narrate in Hebrew, they manage to express causal relations with less varied language tools in Russian narratives. We further understand that the production of more episodic components does not necessarily lead to more causal relations—as shown for SL/Hebrew. In Russian narratives, however, narrative components—though fewer in quantity—seemed to be better linked with each other. Future studies should further investigate these discrepancies in terms of possible attrition processes in HL and home versus school language. The expression of causal relations in HL narratives may be less dependent on lexical diversity and richness but on other types of linguistic knowledge used to target cohesion. This is presented in the last Section of this discussion.

5.3. Language Forms as Cohesive Strategies—Focus on HL/Russian

The third aim of this study was to explore the use of language forms to establish causal relations. The qualitative analyses revealed general linguistic mechanisms along use of language-specific forms in the domains analyzed here—lexical, syntactic, and referential cohesion. A fine-grained analysis compared the forms used for encoding the onset of the story, revealing a rich array of language forms, and the use of specific lexicon and morpho-syntactic structures such as obligatory marking of aspectual distinctions, case markers, prepositions, and conjunctions. The presence of certain grammatical features in Russian is related to typological features of the language. This is evidence that participants are sensitive to the dominant patterns of the language, but it does not necessarily indicate that HL is stronger than SL. Since language-related measures were similar in both languages, future studies should address what these findings tell about cross-language differences versus the effects of proficiency/language dominance and other individual factors on narrative-embedded language.

In HL/Russian, children used more manner of motion verbs followed by path particles, in accordance with satellite-framed typology (), while in SL/Hebrew, children frequently used general motion verbs like halax ‘went’ and more varied path verbs to express the initiating event (e.g., yaca ‘left’, barxa ‘escaped’, neelma ‘dissapeared’, neebda ‘got lost’). The use of manner adverbs was surprising at this age, as compared to monolingual frog story samples at the same age in Hebrew (). Thus, as found in other studies with bilinguals, ‘thinking for speaking’ patterns related to motion events typology are transferred from one language to the other and affect the way children use expressive means for various narrative functions ().

Lexical cohesion was critical for inferring causal relations, facilitating semantic links between events. Causal chains were disrupted when episodic components were missing or when lexical choices were not specific enough to allow a semantic relation between the predicates. Further studies are needed to understand whether this is caused by poor lexical knowledge, retrieval deficits, or global planning difficulties. When specific words were missing, other linguistic means or clues were needed to reflect the conceptual representation of causal relations.

Syntactic and referential cohesion contributed to the expression of around half of the causal relations, in both languages. Previous studies of causal relations and narrative connectivity (, ) showed that coordination and subordination facilitated the interpretation of causal relations, unlike the use of linear, chronological markers (e.g., ‘and then’) that disrupted causal links (see also ). Subordination enhanced causal relations when framed into specific temporal relations that highlight the contrasting actions and states of mind of the main protagonists (e.g., frog escapes while boy and dog sleep). Subordination was also used to link motivations with actions and reasons with their consequences, in which case the relations had to be inferred and could not be directly perceived in the pictures. However, for most of the motivational relations coded in this study, throughout the successive attempts to search for the frog, lexical and referential rather than syntactic cohesion was required. Thus, although syntactic cohesion is the most salient means to express causal links (), it is not an essential condition for expressing causality, despite its expressive value. The study of causal relations provides a suitable context to understand the development of early acquired, multifunctional conjunctions (e.g., ‘and’) and of more specific subordinating connectors (e.g., ‘when’) in the context of discourse, in HL and SL. The qualitative analyses showed that our bilingual participants are aware of the functions of various connectors and use them for temporal and causal purposes in two different languages, as shown in previous studies (). In the present study, these analyses were performed in the direction that goes from function to form. Future studies with bilinguals should perform more exhaustive analyses of syntactic cohesion in HL.

Referential cohesion facilitates the expression of causal relations by clear anaphoric reference with pronouns, null pronouns, or lexical nouns (). Unlike lexicon and syntax, referential cohesion depends on more abstract cognitive and pragmatic abilities that guide narrators to the recurrent access to characters throughout the story, in a precise manner with respect to the identity of the character, the status of the information and the language forms to be used (). Despite the typological differences between Hebrew and Russian concerning the referential system, the ability to create referential anchors () showed similar trends in HL and SL. At preschool, clear and consistent reference was challenging due to story length and episode complexity. Future studies should raise more specific questions regarding the way reference affects causal relations beyond the creation of cohesive identity chains.

To conclude, the study showed that episodic components and causal relations behave differently—the former assesses the ability to express content categories, while the latter reflects the ability to create relations through cohesive links. The qualitative methods adopted in the study allowed the careful tracking of these narrative-embedded language skills in HL and SL. Future studies should further explore causal relations in additional language pairs. Additional cross-linguistic research will assist in isolating language-specific components of causal relations. Furthermore, by using a longitudinal design research will examine developmental patterns of causal relations.

Looking at the interaction of microstructure and macrostructure has theoretical, educational, and clinical implications. Theoretically, the expression of causal relations seems to reflect more accurately the processes that guide discourse construction from a cognitive and linguistic perspective together—pointing to universal versus language-specific skills. This adds to our understanding of the role of linguistic knowledge in storytelling and the extent to which a successful narrative depends on language-related measures in each of the languages. From a clinical view, since causal relations and the linguistic elements used to express them target several levels of knowledge, they can be used in the assessment of language disorders. Given the significance of narrative abilities in attaining decontextualized language and literacy skills, the study underscores the use of causal relations in narrative instruction and intervention planning, to enhance both macrostructural and microstructural knowledge.

Author Contributions

Coding and analysis, S.F. and J.R.K.; Formal analysis, S.F.; Writing—original draft, J.R.K.; Writing—review and editing, J.R.K., S.F. and S.A.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Israel Science Foundation 863/14.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bar Ilan University Institutional Review Board (Humanities) (approved 28 October 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results of Likelihood Ratio Tests for the analysis of episodic components.

Table A1.

Results of Likelihood Ratio Tests for the analysis of episodic components.

| AIC | BIC | logLik | Deviance | Chisq | Df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | −55.31 | −48.35 | 31.65 | −63.305 | 4.55 | 1 | 0.03 |

| AoB | −53.32 | −44.64 | 31.66 | −63.324 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.89 |

| AoB × Language | −56.24 | −45.81 | 34.12 | −68.237 | 4.93 | 2 | 0.08 |

| Proficiency | −63.06 | −54.37 | 36.53 | −73.055 | 9.75 | 1 | 0.002 |

| Language × Proficiency | −61.33 | −50.90 | 36.67 | −73.33 | 0.275 | 1 | 0.60 |

Table A2.

Results of Likelihood Ratio Tests for the analysis of episodic components per episode.

Table A2.

Results of Likelihood Ratio Tests for the analysis of episodic components per episode.

| AIC | BIC | logLik | Deviance | Chisq | Df | p | |