Abstract

In this communication, I focus on Shawi forms of address used in Peruvian State posters during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic took a heavy toll on the Peruvian Indigenous population. A recent study showed that Indigenous people had 3.18 times the risk of infection and 0.4 times the mortality risk of the general population in Peru. The Shawi have not been included among the most heavily affected. A preliminary descriptive and critical account of Peruvian State posters whereby languages such as Shawi and other Peruvian Indigenous languages (Awajun, Ashaninka, different varieties of Quechua, Shipibo, etc.) have been used to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is provided. Shawi seems to be the only language of the sample where information has been framed using first-person inclusive forms. This appears to have led to enhanced communal engagement in the suggested health-related practices. Additionally, opinions on the issue from local stakeholders are briefly discussed. While the results are derived solely from preliminary observations, my findings could serve as a basis for enhancing health communication strategies in other Indigenous contexts, utilizing linguistically informed intercultural approaches.

1. Introduction

The Indigenous Holocaust (Smith 2017) has been one of the greatest catastrophes in human history. Smith (2017) estimates that over 175 million Indigenous people have been lost between 1492 and the beginning of the twentieth century. The numbers only worsen when including the 20th century and the last couple of decades. Although the Great Invasion and the colonizing processes thereafter were the trigger of this catastrophe, several post-invasion events, i.e., imported epidemics and unfavourable post-colonial social stratification, continue to affect the remaining Indigenous population until today.

When the COVID-19 pandemic was declared on 11 March 2020, one of the primary concerns in several South American countries was the protection of Indigenous populations. For Indigenous people, this was just one of the many foreign pathogens that outsiders had introduced into their ancestral homelands. Indigenous associations and leaders immediately raised concern and put into practice a diverse set of strategies that had been useful in past events of similar typology. The studies in Espinosa and Fabiano (2022b), for instance, describe strategies followed by the Shipibo (Favaron and Bensho 2021), the Ticuna (del Águila Villacorta et al. 2022), the Shawi (Castro 2022), etc., during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unfortunately, the pandemic took a heavy toll on several Indigenous populations (see, for example, Muere por coronavirus el cacique Aritana Yawalapiti, defensor de la Amazonía 2020).1

The COVID-19 pandemic was probably one of the most challenging social phenomena in the era of globalisation. Informing citizens from all over the world, who did not necessarily share the same culture or language, about social distancing and general prevention measures became a priority. Previous research highlighted the importance of presentation styles when informing people (Sunstein and Thaler 2003, p. 1182). The way ideas are framed can thus alter people’s behaviour in predictable ways without properly modifying underlying intentions or incentives (Dorison et al. 2022; Sunstein and Thaler 2003). For instance, in a recent macro-survey with a sample of over 89 countries, it has been observed that messages that promoted social distancing rooted in choice promotion and agency were more effective as regards long-term engagement with social distancing than forceful shaming messages (Psychological Science Accelerator Self-Determination Theory Collaboration 2022). Although the sample was of considerable size, little to nothing has been said about these same dynamics outside the realm of Western, European, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies. In 2020, the Peruvian State launched a campaign to inform Indigenous citizens about the spread of the coronavirus disease and to foster social distancing, isolation, and preventive measures. The campaign deployed posters (see Figure 1) and radio-streamed messages (Ministerio de Cultura traduce información y mensajes preventivos sobre el COVID-19 en 21 lenguas originarias y variantes 2020). The Spanish version of the poster was translated into 24 Indigenous languages, which include Harakbut, Shawi, Ticuna, Yanesha, Matsigenka, Urarina, Awajún, Aimara, Murui-Muinane, Quechua (Cajamarca, Ancash, Cuzco-Collao, Chanka, Huanca, and Napo), Wampis, Asheninka, Ashaninka, Yagua, Shipibo-Konibo, Kakataibo, Jaqaru, Yine, and Ocaina.

Figure 1.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. Poster used as a basis for translations into Peruvian Indigenous languages. The title and the main text are in Spanish and literally mean: “Protect yourself against the coronavirus. Steps for a correct hand-wash. That is how you prevent respiratory, diarrheic, and other types of diseases”. All materials can be found and downloaded following this link: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/cultura/campa%C3%B1as/872-acciones-contra-el-coronavirus-lenguas-originarias (last accessed on 18 January 2024).

Even though the good intentions behind the campaign cannot be denied, the COVID-19 pandemic still took a heavy toll on the Peruvian Indigenous population. A recent study showed that Indigenous people had 3.18 times the risk of infection and 0.4 times the mortality risk of the general population in Peru (Soto-Cabezas et al. 2022). The Indigenous Shawi have not been included among the most heavily affected. According to local sabios (wise men), such as Elio Yumi Pizango, Segundo Pinedo Escobedo, and the Achinapi (teacher) Rafael Chanchari Pizuri (p.c.), the Shawi were not affected by the coronavirus pandemic. The numbers presented in the local studies, however, must be carefully re-examined, as Indigenous populations tend not to appear in the official counting, either due to an overflow of patients or simple mistrust in Western medicine (which means avoiding hospitals and Western physicians by all means) (see Espinosa and Fabiano 2022a).

In this short communication, my focus is on the posters distributed by the Peruvian State in 24 Indigenous languages, with particular attention to the Shawi version. Shawi appears to be the only language of the sample where information has been presented using first-person inclusive forms. Based on exchanges with local sabios, I suggest that this could have triggered improved engagement in the suggested practices, thus, potentially, contributing to the lesser impact in the spread of the virus in Shawi communities. In Section 2, I provide a sketch of the contemporary Shawi community, as well as their language, focusing on its clusivity system (Barraza de García 2005) and the use of inclusive forms when describing important Shawi institutions. Section 3 provides an analysis of some of the languages of the poster sample (Shawi, Awajún, Quechua varieties, Aymara, Jaqaru, and Shipibo-Konibo)2, thus providing a direct comparison with the Shawi variant. Section 4 discusses the findings in light of recent discussions (January 2024) with local stakeholders in the city of San Lorenzo del Datem del Marañón and the town of Balsapuerto in Alto Amazonas. Section 5 outlines the preliminary conclusions.

2. The Shawi, Their Language, and Its Pronouns

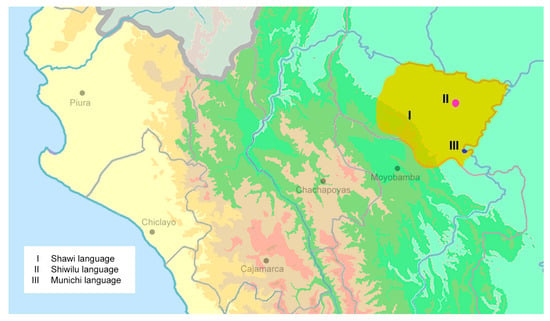

Shawi stands as the sole remaining vital language within the Kawapanan language family. Its sister language, Miquira, may have become “extinct” in the early twentieth century, while another sister language, Shiwilu, is still spoken by a few dozen elders in the towns of Jeberos, Jeberillos, and San Gabriel de Varadero, located in Alto Amazonas, Peru. Shawi remains actively used by individuals of all ages, with many being coordinated bilinguals in Spanish. According to State sources, the Shawi population is said to surpass 21,000 individuals (Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática 2009) and keeps growing. According to the independent and collaborative Native newspaper Salud con Lupa, the total Shawi population amounts to 31,284 individuals (Salud con Lupa 2021). Today, Shawi is spoken in the triangle formed by the Marañón River, the Huallaga River, and the Escalera Mountain Range (see the Map on Figure 2). As is the case with many Amazonian groups, communities are steadily growing in number and new communities are being founded close to cities outside this triangle. The farthest communities can be found on the margins of the Morona River and close to the city of Iquitos (the capital of Loreto), over 400 km away.

Figure 2.

The Shawi speaking area within Peru. Within the area, two other languages are spoken, namely, Shiwilu, also known as Jebero, and Munichi, a language isolate. Although Munichi is not a Kawapanan language, it has undergone prolonged contact dynamics with Kawapanan languages.

The Shawi belong to the Bajo Huallaga cultural complex, which encompasses different ethnic groups such as the Chamicuro (Chamekolo), Muniche, Lamista, Shiwilu, and Kukama-Kukamiria. These groups have in common the fact that they were reducidos, lit. ‘reduced’, in the times of the Jesuit Missions, before the independence of Peru. For Gow (2009), these Indigenous groups might have reemerged out of a complex social phenomenon which implies not just impending Christianisation, but also the emergence of a new type of social stratification which differentiates them, i.e., indios cristianos ‘Christian Indians’, from non-Christianised Indians, dubbed kema in Shawi (mostly used to refer to the Jivaroan Awajún) (q.v. Gow 2009). This also contributed to the emergence of an identity hoisted in missionary centres, which modern communities stem from, and which heavily relied on communitarian practices which included the even distribution of power, food, community chores, etc. The disappearance of smaller languages such as the Paranapuro or Tabaloso (Teruel n.d.) and the emergence of larger lingua francas fostered by catechism practices such as San Martín Quechua, Shawi (Rojas-Berscia 2021), or Shiwilu (see Alexander-Bakkerus 2013 for the latter) are also a result of this phenomenon.

In the case of Shawi, communitarian practices are also linguistically reflected. As is the case in many languages of the region, such as Quechuan and Aymaran (Cerrón-Palomino 2008), Shawi displays an inclusive vs. exclusive distinction in person marking strategies. This is reflected in the pronominal system of the language (Rojas-Berscia 2021, p. 91). See Table 1.

Table 1.

Shawi free pronoun system.

Free pronouns have bound counterparts as subject, object, and recipient suffixes for all moods, as well as possessor suffixes and markers for nominal predication (Rojas-Berscia 2021, pp. 74–84). This is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Shawi bound pronouns.

Beyond structural facts, Shawi speakers tend to pervasively use inclusive/exclusive forms in daily speech. This seems to work as a sociolinguistic index (q.v. Agha 2005; Silverstein 2003) of community belonging. This is reflected in the naming of Shawi institutions, which include first-person inclusive pronouns: kanpunan (lit. our (yours and mine, not theirs) language), kanpupiyapi ‘Shawi people’ (lit. our (yours and mine, not theirs) people), *Kanpuwanama’ (lit. our lord) ‘Cumpanamá (God) (Rojas-Berscia and Ghavami-Dicker 2015). In addition, if two Shawi men or women have a conversation, inclusive forms abound. If there is a mestizo (lit. ‘mixed-race’, used for Spanish descendants and not considered pejorative) or a kema (Awajún [Jivaroan]), exclusive forms abound. See the exchange below. It was extracted from a conversation between one of our main consultants, Catalino Pizango, and his nephew. They discuss the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic (all inclusive forms are marked in bold):

Nephew: Irakaware kanpuaru ihse, ihse ya’urewake, ina kaniu, nunca, nunca. Kanpua na’tanterewa ma’nin kaniu, nimara, kanpu ihsu ya’werewasu. Sha’pikaniu, nituterewa ihsu nisha, a’na kaniu. Tuhpinan, u’wairu nituterewa nisha, nisha kaniu nituterewa, pero ihsu kaniu ya’urinsu. Ku kanpua nituterewa na’sha pi’pirarin kanpuantawe pi’pirinsu ku nituterewa. Ihse ya’urewasu, mamapeirusa, tatama’shurusa, ma’shurusa, pa’yanpita, hasta kanpuanta pa’yanewa. Nahpurinpinin inamare, kemasu unpuinta. Mahsu, este, ihsu kaniu pihpirarin unpuinta kankantera, ¿pa’yanan, ku pa’yananun?

“Since well before, where we live, we never knew about that disease. Who knows what it might be. Where we live, we know about yellow fever, we know about yellow fever, another disease. We only know about bronchitis, we know about different diseases, but we do not know anything about this disease. Here, where we live, grandpas and grandmas were scared. Even we got scared, it is true. But you, regarding this disease, how do you feel? Were you scared?”

Catalino: Tewenchachin, kanpuwasu, piyapinpua, shawinpua3, ihse ihse ninewasu wa’yanusa takirawachina, se’terewa.

“It’s true. We, given that we are people, that we are Shawi. When the mestizo died, we were sad.”

Nephew: Tewechachin, nuhten, ahpi.

“That’s true, uncle.”

Catalino: Kanpuanta tenewa. Kanpuasu ta’kiarewa.

“We also said: “We will disappear””.

Nephew: Ku ninanuke pa’newa nihtun, kanpuaru natanterewa ninanuke na’kun wa’yanusa chiminawi.

“We did not go to the city. We know that many mestizos are dying in the city”.

The conversation was recorded in late 2021, in the community of Canoapuerto. Canoapuerto is a piedmont community that can only be reached by foot (~1 h) or, more recently, by motorcar (~15 min) from the town of Balsapuerto, if the weather allows.

As regards the use of these forms, even when resorting to the local variety of Spanish, the use of first-person plural inclusive/exclusive forms emerges. For example, it is very frequent to hear phrases such as Nosotros shawi ‘Us Shawi’ or Nosotros porque somos shawi ‘Us, because we are Shawi’, in interactions between Shawi community dwellers and mestizos. In these cases, the Shawi resort to Spanish periphrases to express what in Shawi would otherwise be straightforwardly conveyed with exclusive pronominal marking, namely, kiya, as a free pronoun, or -kui as a bound form. Local mestizos also comment on this style, emphasising on how “redundant” it sounds. Beyond the mere anecdotal effect of its use, this phenomenon could be considered a discursive tradition in Shawi textual elaboration.

3. COVID-19 among Indigenous Peruvians and Forms of Address in Peruvian State Posters

In 2020, the Peruvian State, through its Ministries of Culture and Health, launched a campaign to prevent the spread of COVID-19 among Indigenous communities. The campaign consisted of translating a poster and radio messages that would reach most Indigenous communities. The messages, in the end, were only translated into 24 different languages (Acciones contra el coronavirus | Lenguas Originarias 2021). After engaging in informal discussions with linguists Yolanda Payano Iturrizaga, who specializes in Jaqaru translation, and Leo Almonacid Leya, an expert in Ashaninka translation, it became evident that translators are typically provided with a Spanish model to translate into Indigenous languages when assigned such tasks. However, they noted a lack of further information provided beyond this initial instruction.

According to the Sistema de Notificación de la Vigilancia Epidemiológica, CDC (lit. Notification System of Epidemiologic Vigilance), by September 2021, the Indigenous group with the largest number of cases was the Awajún (Jivaroan), with 7490 cases4, followed by the Kichwa, with 3390 cases, the Ashaninka, with 2028 cases, and the Shipibo Konibo, with 1252 cases. The Shawi only registered 352 cases (Salud con Lupa 2021). As regards deaths by ethnic group, the Awajún were the most affected with 46 losses, followed by the Ashaninka (21), the Kichwa (18), and the Achuar (7). Although the number of human losses seems to be low, the lack of access to healthcare services must be considered. According to Salud con Lupa, less than 1% of the 1690 healthcare establishments in Indigenous communities have a hospitalisation facility. The situation only worsens when knowing that the Peruvian State itself promoted the displacement and non-compliance of distance measures among Indigenous populations, when distributing a monetary voucher for financial help in times of crisis that the Indigenous population could only have access to if travelling to major towns or cities (Espinosa and Fabiano 2022a, 2022b). Moreover, the campaign launched by the Peruvian State mostly relied on written language. The radio alternative, in that regard, seemed to have been a better solution given that literacy in Spanish/Indigenous language is very low among Indigenous populations in Peru. However, based on my own experience in the field, radio is not necessarily the preferred means of communication in contemporary Indigenous communities either. Not everybody has access to a radio signal receiver. The use of mobile phones and social media is increasingly popular. This seems to have allowed the written posters to be distributed faster. They could have been read aloud by local authorities, such as apus (in the Bajo Huallaga) or líderes (in the Selva Central). Despite this overall dire situation, the Shawi seem not to have been heavily affected during the pandemic.

The Peruvian State posters analysed here include Andean languages such as Quechua, Aymara, and Jaqaru; Central Amazonian languages such as Shipibo (Panoan) and Ashaninka (Arawak); and Bajo Huallaga languages such as Shawi and Awajún (Jivaroan). These languages were chosen based on two criteria: (1) the existence of strong communitarian traditions among their speakers, and (2) access to linguistic knowledge from consultants. In this regard, languages such as Murui-Muinane or Kakataibo were not considered in this preliminary discussion.

In the case of Quechuan varieties such as Chanka, the second person imperative is used: Harkaku-y, lit. protect-imp.2. The same holds for qati-y, follow-imp.2, and qayaymu-y, call-imp.2 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster translated into Chanka Quechua.

In the case of Napo Kichwa, an Amazonian variety, the same strategy is used. The second person imperative is used for the titles, e.g., washa-y, protect-imp.2, kati-y, follow-imp.2, and kaya-y, call-imp.2. Even in the translation of the famous hashtag #yomequedoencasa, lit. ‘I stay home’, the imperative has been used, kipari-y, stay-imp.2 (see Figure 4), thus meaning ‘stay home!’.

Figure 4.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster translated into Napo Kichwa.

As regards Huanca Quechua, a central Quechuan variety, the pattern holds. The strategy was to translate the Spanish original literally, e.g., amachaku-y, protect-imp.2, lula-y, do-imp.2, and aya-y, call-imp.2 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster translated into Huanca Quechua.

This translation strategy is followed in all remaining varieties of Quechua from the campaign, i.e., Cajamarca Quechua, Ancash Quechua, and Cuzco-Collao Quechua.

In the case of Central Amazonian languages, such as Shipibo-Konibo and Ashaninka, the pattern seems to be the same. In Shipibo, for example, the (second person) imperative -we (Faust 1973, p. 11) has been used, e.g., koirame-we, take.care-imp.2, chiban-we, follow-imp.2, bane-we, return-imp.2, and kena-we, call-imp.2 (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster translated into Shipibo-Konibo.

In Ashaninka, the leave-taking formula pamabentakotyaro, meaning “take care” (Mihas 2015, p. 149), is used (see Figure 7). Given that Ashaninka does not have a specific morphological means of marking canonical second-person imperatives (Mihas 2015, p. 499) and intonation patterns (preferred means for the conveyance of commands) are not marked in written form, we need to be guided by person-marking, e.g., po-jate-ro, 2-go-3nm.o, and pi-n-kajem-e, 2-irr-call-irr. What is interpreted as imperative is always conveyed using the irrealis in the language (Mihas 2015, p. 499).

Figure 7.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster translated into Ashaninka.

The Aru languages, also called Aymaran languages (Cerrón-Palomino 2000), display a similar pattern. In the case of Jaqaru (Hardman 1983), the verb used in the title is jakat-ma-ta-m-txi, leaveimp.2-prohib.2-imp.2-neg, where an unusual chain of imperatives occurs. Second person imperatives are also used in the other cases: nur-ma, do-imp.2, jarwaq-ma, stay-imp.2, and ar-ma, call-imp.2 (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster translated into Jaqaru.

For Aymara, the same strategies were followed. The second person imperative -ma (Hardman 2001) was used, e.g., jark’aqas-ma, protect-imp.2, uta-n-kak-ma, house-loc-be-imp.2, and jaws-ma, call-imp.2 (see Laime Ajacopa et al. 2021, for translations of the roots) (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster translated into Aymara.

In the case of Awajún, a Jivaroan/Chicham language of the Upper Amazon, the same translation strategies hold. The imperative suffix -ta is used (Overall 2017), e.g., kuwitam-jama-ta, take.care-2p.o-imp.2, umík-ta, accomplish-imp.2, and untsumka-ta, call-imp.2 (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster translated into Awajún.

The Shawi case is of particular interest, as the translation strategy sees no parallel (see Figure 11). The title literally reads: “A new disease, coronavirus, is entering us, take care of each other”; see yakunt-a-r-in-pua, enter-prog-real-3min.s-1incl.aug.o, and ni kiwite-ke-na, recip take.care-imp-pl. This trend, unlike the other languages, is also followed in the hand-wash strategies poster, which literally reads: “how to wash our hands (not yours)”; see imira-ne-npua, hand-inalien-1incl.aug.poss. However, for the instruction in the main poster, the second person imperative is used: nunte-ke, follow-imp.2. The same occurs in the hashtag, kiparite-ke pei-ke, stay-imp.2 house-loc.

Figure 11.

©Peruvian Ministry of Health. General poster and hand-wash poster extract translated into Shawi.

As regards the main titles, in Table 3, I summarise my observations.

Table 3.

Summary of different person-marking strategies in the titles of the Peruvian State posters to prevent COVID-19 spread in Indigenous communities.

It would be farfetched to claim that the Shawi poster translations lie behind the fostering of health-related practices, or that there is a direct correlation between their use and the results observed after COVID-19 receded. It could be, however, that this strategy, together with an array of ancestral practices aimed at dealing with the arrival of foreign pathogens in the Shawi area (Castro 2022), partially explains why the Shawi were not severely affected by COVID-19. In the following section, I explore some local opinions on this specific topic.

4. Discussion

In the previous sections, I highlighted how Shawi communitarian practices are linguistically reflected through the pervasive use of inclusive/exclusive forms in discourse. This strategy is also present in the poster from the Ministry of Health aimed at preventing the spread of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020. Surprisingly, in the case of other Indigenous groups, the social practices of which find many parallels with those of the Shawi, the same strategy was not used in the translations into their Indigenous languages.

In a conversation with two Shawi women, Mady Huazanga Sánchez and Rebeca Pinedo Escobedo, on January 13th 2024, in the city of San Lorenzo del Datem del Marañón, regarding this campaign, they assert the following:

Mady Huazanga Sánchez: “Yo te dije porque yo he escuchado en awajún, y como si fuera en awajún no le importara nada. Como dice en awajún, “si quieres lava tu mano”, pero en shawi no es es así. En shawi dice “vamos a lavar juntos todos”, “vamos a lavar nuestro mano”. Es lavada del mano dicen, pero en awajún no dicen así. En awajún dice “lava tu mano”. Eso quiere decir. Está hablando con una sola persona […] porque está diciendo “lava tu mano”, pero en cambio en shawi abarca todo lo que es en general.”

Rebeca Pinedo Escobedo: “En general”

Mady Huazanga Sánchez: “Eso es lo que yo entiendo”

Rebeca Pinedo Escobedo: “Sí, es cierto lo que dice ella, este, porque porque nosotros hemos vivido en nuestra zona, por ejemplo. Hemos vivido donde que dice ese esa pancarta lo que dice lavemos las manos. Nosotros como shawis hemos este hemos practicado ese lavada de mano, ya, pero, eh, no hemos, este, no hemos hecho al 100%. Por ejemplo, mantener el distanciamiento, ¿no? No hemos hecho nosotros normal, hemos visitado entre familia, entre la comunidad, pero sí hemos tomado vegetales de la zona. Ya, pero, así como dices, lavemos las manos es como dice ella. Se refiere en general, pero, eh, como dice ella, en awajún es, es como si estaría diciendo a una sola persona: “lávate las manos”, pero en shawi es general.”

Translation

Mady Huazanga Sánchez: “I tell you because I have heard in Awajún, as if they did not care at all in Awajún. As is said in Awajún, “if you want, wash your hands”, but in Shawi it is not this way. In Shawi it says, “let’s wash our hands all together”, “let’s wash our hands”. They call it handwash, but in Awajún it is not this way. In Awajún they say, “wash your hand”. That is what it means. You are talking to one single person […] because you are saying “wash your hand”, but in Shawi it is more general.”

Rebeca Pinedo Escobedo: “In general.”

Mady Huazanga Sánchez: “That’s what I understand.”

Rebeca Pinedo Escobedo: “Yes, what she is saying is true, because we have experienced that in our area. For example, we have experienced (lit. lived) what is said in that poster, that we must wash our hands. We, as Shawi, we have put into practice that handwash, but we have not done it a 100%. For example, keeping social distancing, right? We acted normally, we visited family, inside the community, but we had local herbs. Ok, but, as you say, washing our hands was as she says. It means “in general”, but, as she says, in Awajún, it is as if they referred to a single person, “wash your hands”, but in Shawi it is general.

This conversation was recorded during an exchange the author had with Mady Huazanga Sánchez and Rebeca Pinedo Escobedo on contemporary Shawi societal practices. The participants were talking about customs, traditions, the use of the Shawi language, and recent issues they had to deal with. It was in that context that the COVID-19 pandemic was raised, and the author asked for their opinion about the messages portrayed in the translations. It was unexpected that Mady Huazanga Sánchez had some knowledge of Awajún. Based on her knowledge of the two languages (Shawi and Awajún) and as a L1-speaker of Shawi, she compared the Awajún and the Shawi posters. For her, the Awajún poster message indexed individual action. The Shawi one, conversely, addressed communal action, e.g., vamos a lavar todos juntos, i.e., “let us wash all together”. This was confirmed by Rebeca Pinedo Escobedo. She was honest in admitting that social distancing measures were not always complied with, but she agreed with the “general” character of the Shawi addressing strategy, i.e., engaging with the totality of the community.

As such, it seems that the strategy deployed by the Shawi translator had a different effect. In most cases, the State’s messages were framed in a way that portrayed the State as an authority that was prompting individual action or making them go somewhere to do something. In the Shawi case, the State was portrayed as a member of the Shawi community (prompting communal action) through the use of the first-person inclusive. The message is exactly the same, but the way it can be received by the community, as well as all potential effects thereafter, seem to be different. This goes hand-in-hand with what has been found in previous studies on the effect of message presentation/framing when informing people (Psychological Science Accelerator Self-Determination Theory Collaboration 2022; Sunstein and Thaler 2003). This might be even more prominent in the poster title, as it is the first thing to be read from afar. As is argued for in other studies in this Special Issue, the choice of pronouns of address has a significant impact in engagement with the public (den Hartog et al. 2024; Sánchez Carrasco, van Hoften, and Schoenmakers, this issue). In the case of the posters, the use of first-person inclusive bound pronouns seems to have fostered better engagement with the public.

In a conversation with achinapi Rafael Chanchari Pizuri (Figure 12) in the city of Lamas on 27 January 2024, he commented on the use of these pronouns. Chanchari Pizuri (p.c.) mentioned that he has been involved in the translation and interpretation of State messages during the pandemic. He emphasised the importance of the understanding of Indigenous cosmovisions and the careful use of these pieces of knowledge to convey State messages. He added that translations could not be carried out literally from Spanish moulds. This could inevitably trigger misunderstandings.

Figure 12.

Achinapi Rafael Chanchari Pizuri discussing Shawi traditions.

These ideas seem not to be exclusive to the Shawi area. I also had the chance to exchange ideas with Leo Almonacid Leya, an Ashaninka linguist, leader, and translator. He explained that translations practices are not so well established among Indigenous translators and the State, namely, “Te dan el formato para traducir. Así funciona”, lit. trans. “You are given a format you have to translate. That is how it works.” Translators are expected to translate literally what the State provides them. The Shawi case is special, as it seems that the translator took some liberties that eventually allowed the State to better engage with the community. For Almonacid Leya, in reference to the Shawi translation, “eso de realizar afiches colectivos, eso sí es interesante”, lit. trans. “the fact of making collective posters [here referring to the use of inclusive pronouns], that is indeed interesting.” Posters that encourage communal responsibility and action among these Indigenous groups appear to be more interculturally appropriate.

I hope that these observations and discussions prompt pluricultural States to be better informed when it comes to policies aimed at dialoguing with non-WEIRD groups. Although intentions in this case were far from negative, speedy monocultural measures could potentially trigger opposite effects. The presentation and framing of messages need always be interculturally informed.

5. Final Ideas

The use of Shawi first-person inclusive pronominal marking in State posters during the COVID-19 pandemic seems to have had a different effect when compared to the literal translations using second-person imperative marking in posters in other languages. This was discussed by local Shawi stakeholders, who experienced this message as a call to act all together. The question of whether a relationship exists between this practice and the relatively “minor” impact of COVID-19 on Shawi communities remains unsolved.

Based on our initial observations and the opinions of our collaborators, the State introduced itself as a Shawi, i.e., as a member of the Shawi community, by means of the use of typical Shawi discourse strategies common to the local communitarian practices. According to the stakeholders I interviewed, the use of inclusive pronouns in the titles seems to have triggered more engagement among the Shawi towards the State-imposed measures during the pandemic. It is difficult to assert that this lies behind the low number of infections/deaths among the Shawi. I preferably lean more towards this as an additional variable which, together with local ancestral practices learnt from previous epidemics, allowed the Shawi to be better protected at the time of the arrival of the virus. This, however, stems from observations and more studies need to be conducted to understand the engagement with State messages in radio streaming and television advertisements. Thorough descriptive studies on forms of address strategies in South American languages embedded in long-term ethnographic observation are needed. This is a necessary first step towards proper intercultural dialogue. Finally, future local studies in the fields of epidemiology and ethnopharmacology would be fruitful in shedding some light on the Shawi way of dealing with foreign epidemics.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The interview analysed in this study belongs to the research project Language variation and change in the Upper Amazon: a new koiné which was approved by the Ethics Assessment Committee Humanities (EACH) of the Faculty of Arts and the Faculty of Philosophy, Theology and Religious Studies of Radboud University Nijmegen (2023-5105, 9 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Aritana Yawalapiti, commonly known as Cacique Aritana, was a prominent figure in the fight against the exploitation of the Amazon. Furthermore, he was among the last speakers of the Yawalapiti language. |

| 2 | While conducting an analysis of the entire sample of languages would have been ideal, it was not feasible to find consultants for every language. The analysis presented in this short communication relies on the author’s firsthand knowledge of these languages and the assistance provided by speakers of the languages from the selected sample. |

| 3 | For example, in this case, if the interlocutor were a non-Shawi who can understand Shawi, the nephew would have used the exclusive nominal form Shawi-kui lit. ‘we the Shawi, not you’. |

| 4 | Note that Awajún, according to Ethnologue (Eberhard et al. 2024), is spoken by 53,400 individuals. If these numbers are taken categorically, this means that 14,026% of the Awajún-speaking population got infected. |

References

- Acciones Contra el Coronavirus | Lenguas Originarias. 2021. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/cultura/campa%C3%B1as/872-acciones-contra-el-coronavirus-lenguas-originarias (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Agha, Asif. 2005. Voice, Footing, Enregisterment. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15: 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander-Bakkerus, Astrid. 2013. Vocabulario enla lengua castellano, la del ynga y xebera. STUF—Language Typology and Universals 66: 229–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barraza de García, Yris. 2005. El sistema verbal en la lengua shawi. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, Meredith. 2022. Las epidemias y la llegada de la COVID-19 al pueblo shawi: Apuntes de una conversación con Rafael Chanchari Pizuri. In Las enfermedades que llegan de lejos: Los pueblos amazónicos del Perú frente a las epidemias del pasado y a la COVID-19. Edited by Oscar Espinosa and Emanuele Fabiano. Lima: Fondo Editorial Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, pp. 185–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. 2000. Lingüística aimara. Cuzco: Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos Bartolomé de Las Casas (CBC). [Google Scholar]

- Cerrón-Palomino, Rodolfo. 2008. Quechumara: Estructuras paralelas del quechua y el aimara. La Paz: Plural Editores. [Google Scholar]

- del Águila Villacorta, Margarita, Manuel Martín Brañas, and Marlene Valentín Dosantos. 2022. Nuestros abuelos quemaban la casa de la abeja brava: Percepciones y estrategias frente a la COVID-19 en el pueblo ticuna. In Las enfermedades que llegan de lejos: Los pueblos amazónicos del Perú frente a las epidemias del pasado y a la COVID-19. Edited by Oscar Espinosa and Emanuele Fabiano. Lima: Fondo Editorial Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- den Hartog, Maria, Sanne Bras, and Gert-Jan Schoenmakers. 2024. The Impact of Pronouns of Address in Job Ads from Different Industries and Companies. Languages 9: 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorison, Charles A., Jennifer S. Lerner, Blake H. Heller, Alexander J. Rothman, Ichiro I. Kawachi, Ke Wang, Vaughan W. Rees, Brian P. Gill, Nancy Gibbs, Charles R. Ebersole, and et al. 2022. In COVID-19 Health Messaging, Loss Framing Increases Anxiety with Little-to-No Concomitant Benefits: Experimental Evidence from 84 Countries. Affective Science 3: 577–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig. 2024. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 27th ed. SIL International. Available online: http://www.ethnologue.com (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Espinosa, Oscar, and Emanuele Fabiano. 2022a. La pandemia de la COVID-19 y la experiencia indígena ante las epidemias. In Las enfermedades que llegan de lejos: Los pueblos amazónicos del Perú frente a las epidemias del pasado y a la COVID-19. Lima: Fondo Editorial Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, Oscar, and Emanuele Fabiano, eds. 2022b. Las enfermedades que llegan de lejos: Los pueblos amazónicos del Perú frente a las epidemias del pasado y a la COVID-19. Lima: Fondo Editorial Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Faust, Norma. 1973. Lecciones para el aprendizaje del idioma Shipibo—Conibo. Ministerio de Educación e Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. [Google Scholar]

- Favaron, Pedro, and Chonon Bensho. 2021. Benshoanon: El proceso curativo de la medicina tradicional del pueblo indígena shipibo-konibo. Maguaré 35: 159–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, Peter. 2009. Christians: A Transforming Concept in Peruvian Amazonia. In Native Christians: Modes and Effects of Christianity among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas. Edited by Aparecida Vilaça and Robin M. Wright. Aldershot: Asggate, pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hardman, Martha James. 1983. Jaqaru, compendio de estructura fonológica y morfológica. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos e Instituto Indigenista Interamericano. [Google Scholar]

- Hardman, Martha James. 2001. Aymara. München: LINCOM Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. 2009. Censos nacionales 2007: XI de población y VI de vivienda: Vol. Resumen ejecutivo: Resultados definitivos de las comunidades indígenas. Lima: Dirección Nacional de Censos y Encuestas: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). [Google Scholar]

- Laime Ajacopa, Teofilo, Virginia Lucero Mamani, and Mabel Arteaga Vino. 2021. Paytani arupirwa: Diccionario bilingüe aymara—Castellano, castellano—Aymara, 2nd ed. La Paz: Plural Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Mihas, Elena. 2015. A Grammar of Alto Perené (Arawak). Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Cultura traduce información y mensajes preventivos sobre el COVID-19 en 21 lenguas originarias y variantes. 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/cultura/noticias/112067-ministerio-de-cultura-traduce-informacion-y-mensajes-preventivos-sobre-el-covid-19-en-21-lenguas-originarias-y-variantes (accessed on 8 April 2020).

- Muere por coronavirus el cacique Aritana Yawalapiti, defensor de la Amazonía. 2020. France 24. Available online: https://www.france24.com/es/20200805-brasil-muerte-cacique-yawalapiti-indigenas-bolsonaro (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Overall, Simon E. 2017. A Grammar of Aguaruna. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Science Accelerator Self-Determination Theory Collaboration. 2022. A global experiment on motivating social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119: e2111091119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Berscia, Luis Miguel. 2021. Pre-Historical Language Contact in Peruvian Amazonia: A Dynamic Approach to Shawi (Kawapanan). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Berscia, Luis Miguel, and Sâm Ghavami-Dicker. 2015. Teonimia en el Alto Amazonas, el caso de Kanpunama. Escritura y Pensamiento 18: 117–46. [Google Scholar]

- Salud con Lupa. 2021. Una herramienta para explorar los pueblos de la Amazonía. Salud con lupa. Available online: https://saludconlupa.com/series/el-otro-peru/datos/ (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Silverstein, Michael. 2003. Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. Language & Communication 23: 193–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, David Michael. 2017. Counting the Dead: Estimating the Loss of Life in the Indigenous Holocaust, 1492–Present. In Representations and Realities: Proceedings of the Twelfth Native American Symposium 2017. Edited by Mark B. Spencer. Durant: South Eastern Oklahoma State University, pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Cabezas, M. Gabriela, Mary F. Reyes, Anderson N. Soriano, Jean Pierre Velásquez Rodríguez, Luis Ordoñez Ibargüen, Kevin S. Martel, Noemi Flores Jaime, and Cesar V. Munayco. 2022. COVID-19 among Amazonian indigenous in Peru: Mortality, incidence, and clinical characteristics. Journal of Public Health 44: e359–e365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, Cass R., and Richard H. Thaler. 2003. Libertarian Paternalism Is Not an Oxymoron. The University of Chicago Law Review 70: 1159–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teruel, Luis S. J. n.d. Gramatica de la lengua tabalosa del Peru.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).