Language Perceptions of New Mexico: A Focus on the NM Borderland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To what extend does the north/south and rural/urban divides observed in previous work also appear in the current data set?

- How do southern New Mexicans perceive their language, and to what extent does this vary across the state?

- What language do participants use to divide language groups (i.e., words, prosody, food, descriptions of people, etc.)?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Folk Linguistics and Perceptual Dialectology

Since its introduction, the use of folk linguistics in academic work has been met with some backlash from the sociolinguistic community (see Niedzielski and Preston 2000 for a detailed description). However, there has been consistent support for this subfield for decades. For example, Albury (2017) argues that folk linguistics can make significant contributions to critical sociolinguistics because it gives a voice and legitimizes communities and underrepresented language. Like the current study, Martinez (2003) uses folk linguistics to highlight the changes in language that occur along the United States–Mexico border. He argues for this methodology by stating that it ‘can shed light on how those on the border construct dialect perceptions and the social values that underpin these constructions’ (Martinez 2003, p. 39).‘we should be interested not only in (a) what goes on (language), but also in (b) how people react to what goes on (they are persuaded, they are put off, etc.) and in (c) what people say goes on (talk concerning language). It will not do to dismiss these secondary and tertiary modes of conduct merely as sources of error.’

2.2. Perception Mapping

2.3. The Research Area: Southern New Mexico

New Mexican Spanish and the border with Mexico are and have been an integral part of the identity of the state of New Mexico, especially in the southern part of the state. According to the United States Census Bureau (2019), just over a quarter of New Mexico residents speak Spanish at home, and language mixing or Spanglish can be frequently observed throughout the state. Spanish has been adapted into the English of this area so strongly that it would be impossible to communicate without it. Historically, Waltermire (2017, p. 179) identifies three major factors shaping New Mexico’s English and Spanish use: (1) relative isolation from other Spanish speaking populations; (2) the gradual settlement of English speakers beginning in the mid 1800s; and (3) waves of immigrants during the second half of the twentieth century. New Mexico is the fifth largest state by area, but it has a small population of just over two million residents (United States Census Bureau 2019). New Mexico shares state borders with Arizona, Colorado, and Texas to the west, north, and east, respectively, and importantly, it shares an international border with Mexico to the south.“the reality of New Mexican Spanish is much more complete and quite different from a magical association with Spain. That reality is accurately reflected in the everyday labels that speakers of New Mexican Spanish ordinarily employ to describe their ethnic and linguistic identity: somo mexicanos ‘we are Mexican’ hablamos mexicano ‘we speak Mexican’”.

3. Methods

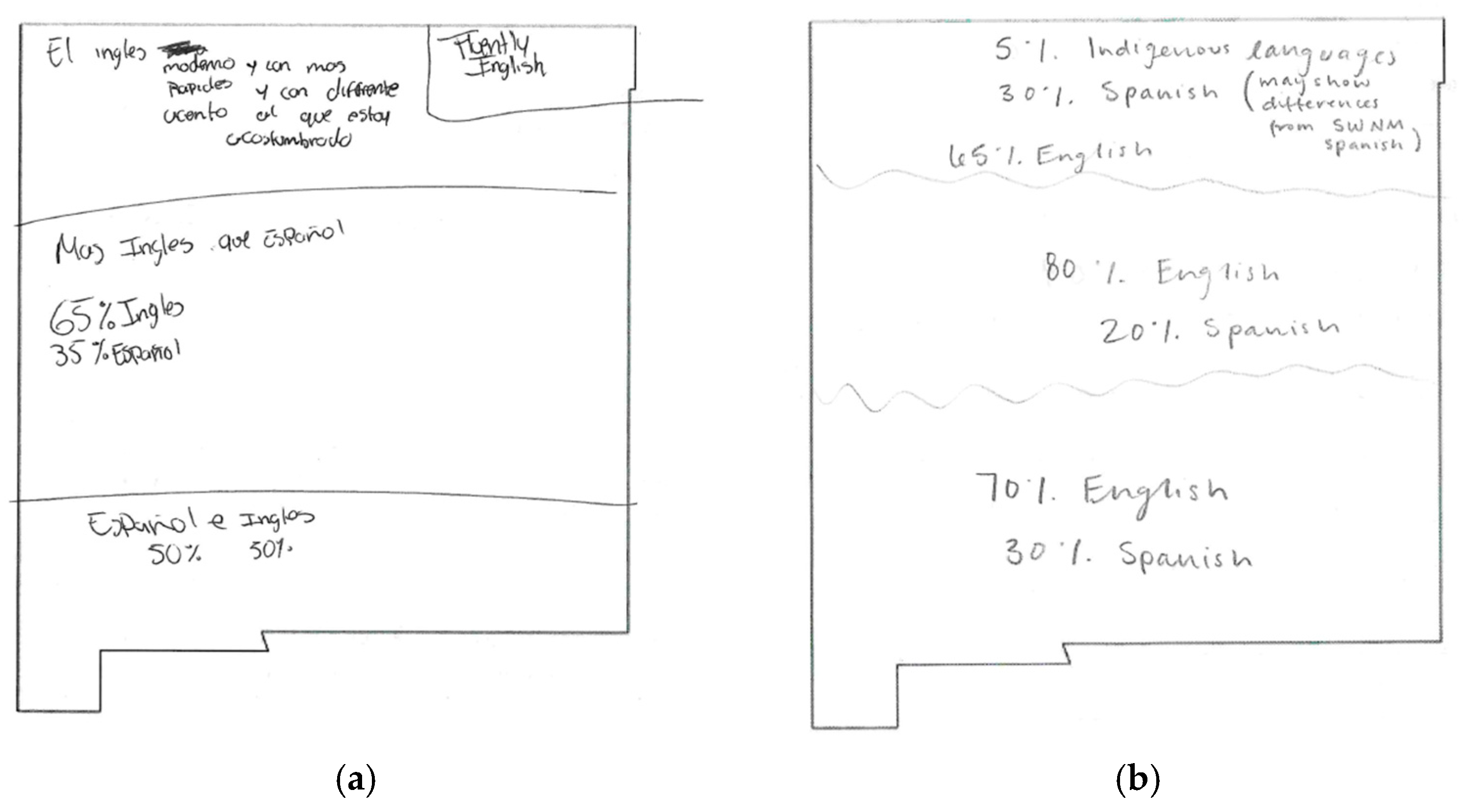

4. Discussion of Results

4.1. North/South Divide and Further Devisions

4.2. The Role of Borders

- (1)

- ‘Dropping sounds, midwestern along CO border; Chicano and country along the southern border, ‘Texas talk’ along border with TX’.

4.3. Rural/Urban Divide

- (2)

- Albuquerque: loud, aggressive, fast;Santa Fe: slow calm Spanish;Las Cruces: Spanish slang;Socorro: slang, western;Carlsbad: country English;Hatch: country Spanish.

- (3)

- ‘I like Las Cruces. I like the diversity in languages. I like that people speak Spanglish like I do.’

4.4. Languages: Use, Judgements, and Mixing

4.5. Lexical Categories

- (4)

- ‘English is professional along the Colorado border to the north, “ghetto” in Albuquerque, and people are well spoken again along the Mexican border’.

- (5)

- North: outgoing, active, proper, polite, harshversusSouth: small town talk.

- (6)

- North: spoiled, drama, ‘oh si’versusSouth: traviesos ‘mischievous’, chismosos ‘gossipy’, ooooo que la ‘uh oh’.

- (7)

- Cantadito en el norte y en el sur hay un español mexicano sin acento.‘Sing songy in the north and in the south there is a Mexican Spanish without an accent’.

- (8)

- ‘Proper English next to Colorado, Ghetto English in Albuquerque, Country Spanish in middle, Spanish in south, Spanglish on TX border’.

5. Conclusions

- RQ 1.

- To what extent do the north/south and rural/urban divides observed in previous work also appear in the current data set?

- RQ 2.

- How do southern New Mexicans perceive their language, and to what extent does this vary across the state?

- RQ 3.

- What language do participants use to divide language groups (i.e., words, prosody, food, descriptions of people, etc.)?

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adank, Patti, Andrew J. Stewart, Louise Connell, and Jeffrey Wood. 2013. Accent imitation positively affects language attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albury, Nathan. 2017. How folk linguistic methods can support critical sociolinguistics. Lingua 199: 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraz, Gabriela. 2002. Miami Cuban perceptions of varieties of Spanish. In Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology. Edited by Daniel Long and Dennis Preston. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, vol. 2, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, Erica J. 2003. Folk Linguistic Perceptions and the Mapping of Dialect Boundaries. American Speech 78: 307–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, Garland D., and Neddy Vigil. 2008. The Spanish Language of New Mexico and Southern Colorado: A Linguistic Atlas. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholtz, Mary, Bermudez Nancy, Fung Victor, Edwards Lisa, and Vargas Rosalva. 2007. Hella Nor Cal or Totally So Cal?: The Perceptual Dialectology of California. Journal of English Linguistics 35: 325–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callesano, Salvatore. 2020. Perceptual Dialectology, Mediatization, and Ididoms: Exploring Communities in Miami. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Jack K., and Peter Trudgill. 1998. Dialectology, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros, Mark, Rodriguez-Gonzalez Eva, Bellamy Kate, Parafita Couto, and Maria Carmen. 2023. Gender strategies in the perception and production of mixed nominal constructions by New Mexico Spanish-English bilinguals. Isogloss Open Journal of Romance Linguistics 9: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, Jennifer. 2013. Styles, Stereotypes, and the South: Constructing Identities at the Linguistic Border. American Speech 88: 144–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cukor-Avila, Patricia, Lisa Jeon, Patricia C. Rector, Chetan Tiwari, and Zak Shelton. 2012. Texas—It’s like a Whole Nuther Country: Mapping Texans’ Perceptions of Dialect Variation in the Lone Star State. Paper presented at Twentieth Annual Symposium about Language and Society, London, UK, August 28–31; Austin: Texas Linguistics Forum, pp. 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Betsy. 2011. ‘Seattletonian’ to ‘Faux Hick’: Perceptions of English in Washington State. American Speech 86: 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Betsy. 2013. “Everybody sounds the same”: Otherwise Overlooked Ideology in Perceptual Dialectology. American Speech 88: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridland, Valerie, and Kathryn Bartlett. 2006. Correctness, Pleasantness, and Degree of Difference Ratings across Regions. American Speech 81: 358–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, Peter, Nikolas Coupland, and Angie Williams. 2003. Investigating Language Attitudes: Social Meanings of Dialect, Ethnicity, and Performance. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garzon, Daniel. 2017. Exploring Miamian’s Perceptions of Linguistic Variation in MiamiDade County and the State of Florida. Master’s thesis, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Peter, and Rodney White. 1986. Mental Maps. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenigswald, Henry. 1966. A Proposal for the Study of Folk-Linguistics. Edited by William Bright. Sociolinguistics. The Hague: Mouton, pp. 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Glenn. 2003. Perceptions of dialect in a changing society: Folk linguistics along the Texas-Mexican border. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7: 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzielski, Nancy A., and Dennis R. Preston. 2000. Folk Linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Dennis. 1982. Perceptual dialectology: Mental maps of United States dialects from a Hawaiian perspective. Hawaii Working Papers in Linguistics 14: 5–49. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Dennis. 1986. Five visions of America. Language in Society 15: 221–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, Dennis. 1989. Perceptual Dialectology. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Dennis. 1999. Handbook of Perceptual Dialectology. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Dennis. 2018. Changing research on the changing perceptions of Southern US English. American Speech: A Quarterly of Linguistic Usage 93: 471–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. 2019. New Mexico State. Available online: https://data.census.gov/profile/New_Mexico?g=040XX00US35 (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Waltermire, Mark. 2017. At the dialectal crossroads: The Spanish of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Dialectologia 19: 177–97. [Google Scholar]

- Waltermire, Mark. 2023. Dispelling Myths about Northern New Mexican Spanish. Paper presented at 12th Annual Languages, Linguistics, and Literature (LLL) Symposium, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM, USA, November 8. [Google Scholar]

- Waltermire, Mark, and Mayra Valtierrez. 2019. Spontaneous Loanwords and the Question of Lexical Proficiency among Spanish-English Bilinguals. Hispania 102: 409–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Damián Vergara, and Christian Koops. 2020/2015. Norteños sing their words and Sueños Mexicanos: Bilingualism and attitudes in the perceptual dialectology of New Mexico. International Journal of the Linguistic Association of the Southwest 34: 168–88, Special issue: Festschrift in honor of Garland Bills. ed. by Daniel Villa. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Damian V., and Ricardo Martínez. 2011. Diversity in definition: Integrating history and studentattitudes in understanding heritage learners of Spanish in New Mexico. Heritage Language Journal 8: 115–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bove, K.P. Language Perceptions of New Mexico: A Focus on the NM Borderland. Languages 2024, 9, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050161

Bove KP. Language Perceptions of New Mexico: A Focus on the NM Borderland. Languages. 2024; 9(5):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050161

Chicago/Turabian StyleBove, Kathryn P. 2024. "Language Perceptions of New Mexico: A Focus on the NM Borderland" Languages 9, no. 5: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050161

APA StyleBove, K. P. (2024). Language Perceptions of New Mexico: A Focus on the NM Borderland. Languages, 9(5), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages9050161