Abstract

Streaming platforms have transformed series distribution and accessibility, with Spanish-language shows gaining immense popularity, notably “La casa de papel” (Money Heist). This series features a diverse cast of characters whose linguistic diversity extends to the use of taboo language. Previous studies have shown that linguistic immersion, such as staying abroad, significantly impacts knowledge of this kind of language. This paper aims to explore to what extent these and other individual differences affect the comprehension of swear words in TV series. To this end, 33 learners of Spanish at B2 level were asked to translate 14 taboo expressions from the series. They also completed a questionnaire on the exposure to authentic language use through extended stays abroad and TV series as well as their attitudes towards the use of taboo words. The results show that students’ positive attitudes towards taboo expressions and their multilingual status were associated with significantly better comprehension of taboo expressions. Furthermore, students with stay-abroad experience, watching the series in Spanish (with or without captions) and with higher proficiency levels in Spanish were found to perform better on the comprehension test, although no significant effects were found. Pedagogical implications and further directions for research are discussed in light of these findings.

1. Introduction

Although the importance of language socialization in foreign language acquisition is widely recognized (Duff 2019), textbooks, teaching materials, and more generally, the teaching practice have been slow in addressing socio-cultural meaning in a wider variety of genres and registers. This is especially the case for taboo language, which has received little attention in comparison to the extensive focus on more conventional linguistic elements. Indeed, being heavily stigmatized, taboo language has long been a marginal object of study in linguistics. Only recently have taboo language and related phenomena such as swearing, insults, euphemism, dysphemism, etc., become the focus of systematic research and thorough redefinitions (see Casas Gómez 2023; Pizarro Pedraza 2018 for an overview). In short, taboo language refers to forbidden or dispreferred words or expressions that name concepts belonging to problematic areas of reality such as sexuality, death, illness, religion, etc. (Allan and Burridge 1991, p. 12). It is often associated with non-referential functions (insults like the noun shithead, or swear words like the interjection shit! are examples of taboo language), but it also includes words and expressions used to refer to taboo concepts, like the noun shit to refer specifically to feces. The particular areas that are tabooed are culturally dependent and thus extremely variable among and within societies, depending on specific cultural norms and linguistic ideologies (Andersson and Trudgill 1992, p. 49). Moreover, the use of taboo language is also subject to a complex interplay of social and contextual factors. In sociolinguistic studies, aspects such as the gender or the age of the speaker, but also the reticence to speak about taboo topics, have an effect on the overall taboo use and on the particular preferences for certain taboo expressions (Pizarro Pedraza 2022).

L1 speakers acquire taboo words early in childhood through episodes of negative conditioning: when a child utters a taboo word and is reprimanded for it, they learn that some words have the special characteristic of being forbidden in particular situations (Jay 2009, p. 158). Several studies have shown that, for bilinguals, taboo words learned earlier in life (namely, in the L1 or in their dominant language) have “higher levels of emotional resonance” (Gonzalez-Reigosa 1976; Harris et al. 2003 in Dewaele 2005, p. 477) than those learned later. Multilinguals actually prefer to swear in their L1, and they only report swearing in the Ln (L2, L3…) when they frequently communicate in that language (Dewaele 2004), which is in fact an indication of a higher pragmatic competence (Fraser 2010, p. 15).

Studies on the acquisition of taboo language within and outside the boundaries of formal language teaching and learning have investigated the impact of factors such as a study-abroad experience, the individual’s overall language proficiency or the acquisition context, among others (see Dewaele 2005). De Cock and Suñer (2018) found that a stay abroad does influence the comprehension of metaphors associated with sexual taboo, highlighting the role of cultural exposure in understanding sensitive linguistic nuances. However, this effect was not observed in the comprehension of expressions from other (more general) topic domains, as reported by Suñer (2019), which suggests that learners mobilize different knowledge resources and deploy qualitatively different strategies for processing taboo language when compared to more formal registers.

Another interesting dimension that emerges when examining taboo language acquisition is the impact of the reticence to discuss taboo topics. Suñer and De Cock (2023) found that a stronger reticence to discuss sexual topics is associated with poorer comprehension of sexual taboo language. Additionally, individuals with study-abroad experience expressed a higher level of acceptability regarding the use of sexual taboo expressions.

It is worth noting that students of Spanish frequently lack knowledge about taboo variants and their degree of offensiveness within specific contexts. Pizarro Pedraza and González Melón (2018) point out that this knowledge gap underscores the need for a more comprehensive approach to teaching and addressing taboo language within the Spanish language curriculum. Learning how to swear appropriately can avoid communicative incidents, because the inappropriate use of swear words can cause embarrassment (Dewaele 2016) or worse, have a negative impact on the social perception of the speaker. Moreover, swear words can display a wide array of pragmatic functions (Beers-Fägersten 2012, p. 20) and can communicate emotional content in a way that no other linguistic element can (Finkelstein 2018). Despite its importance, Mayo Martín’s 2017 study reveals that taboo language is rarely covered in Spanish textbooks, and when it is, it typically occurs only at the advanced C1 level. This becomes even more intriguing when we consider that, as per the CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference, Council of Europe 2001), learners at the B1 level should experience greater exposure to language registers beyond the more neutral ones, including taboo expressions such as swear words (De Cock and Suñer 2018). Overall, several authors plead for a socio-culturally sensitive approach to incorporating informal registers, including taboo language, into language education, be it in the classroom context or outside (Finn 2017). This approach encompasses addressing taboo language at an earlier stage within language textbooks, considering the influence of study-abroad experiences and overall language proficiency, and acknowledging the intricate relationship between reticence, comprehension, and familiarity with various forms of taboo language.

The changes in the autonomous consumption of cultural productions in Spanish are a particularly interesting situation to examine. Thanks to streaming platforms, the distribution of and access to series in languages other than English has been facilitated. Viewers who otherwise rarely watched Spanish series now do so, some with great frequency, as pointed out by Alm’s (2023b) study and as observed in our own classrooms. Particularly during the lockdown, learners combined formal Spanish courses with watching TV series, leading to heightened social engagement with the language in a period marked by social isolation (Alm 2023a). That is the case of highly popular Spanish TV series, such as “La casa de papel” (Money Heist), which have great potential for enhancing learners’ exposure to these informal registers. The mentioned series is an excellent source of variation: The characters present a variety of vernaculars (related to level of education, geography, ethnicity, etc.) mostly from European Spanish, but there is also a very central character that is Argentinian. Linguistic variation is, furthermore, interestingly depicted in the use of taboo language, where we find a rich variety of insults and expletives that reflect the sociolinguistic features of the characters.

This exposure to cultural products in Spanish can be considered a form of ‘internationalization at home’, that is, activities that help students acquire international experience and develop intercultural skills. Whereas much research has been devoted to the impact of subtitling those TV series on (out-of-class) language learning (Liao et al. 2020 for a translational perspective and the special issue edited by Peters and Muñoz 2020 on multimodal input and language learning), little is known about the potential of watching series or of the subtitles for learning informal registers in the foreign language. This is particularly interesting for taboo language, because it is not always maintained in the subtitle and may be omitted or toned-down for technical, ideological or client-related reasons (Ávila-Cabrera 2023, 2024). The effects of these variations for taboo language acquisition are yet to be explored.

In order to explore this situation, the present study aims to investigate the primary predictors affecting students’ comprehension of swear words within the context of learning Spanish as a foreign language through their autonomous access to Spanish TV series, among others. In light of the conclusions drawn from previous research, we hypothesize the following:

H1.

The conditions while watching the TV series outside of the classroom (audio language and captions) significantly influence students’ comprehension of taboo expressions.

H2.

Proficiency level in Spanish as a foreign language and experience gained through studying abroad are key factors in predicting students’ comprehension of taboo expressions.

H3.

Individual social factors, such as the gender of the student, play a role in influencing learners’ comprehension of taboo expressions.

H4.

Learners’ attitudes towards the use of taboo expressions, including context-related and sociolinguistic aspects, have a significant impact on their comprehension of such expressions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

The study was conducted with 33 students (22 female, 10 male, 1 no response regarding gender) enrolled in the BA programs of translation and interpreting (n = 18) or modern languages (n = 15) with French as L1 and Spanish as their Ln at the authors’ universities. Their language proficiency level averaged B2 according to the CEFR after M = 4.7 years of learning Spanish. The sample was best suited for investigating the comprehension of swear words, since the B2 level is considered the threshold for expanding the linguistic repertoire towards a wider variety of genres and registers (cf. De Cock and Suñer 2018). Twelve participants (36%) had spent a stay abroad in a Spanish-speaking country for 3 months or more.

2.2. Instruments

To investigate the comprehension of taboo words and the affecting factors, we developed a comprehension test and questionnaire1 using the framework provided by De Cock and Suñer (2018); Suñer and De Cock (2023). In order to complement our previous studies, for this study we decided to focus on taboo language in non-referential functions, such as insults and swear words. Since these are extremely abundant in Spanish (see, for instance, Luque et al. 2017), we applied a bottom-up approach in order to select our items. Due to its popularity among our students and to the interesting linguistic characteristics mentioned above, we decided to use “La casa de papel” as a corpus. This allowed us to restrict the choice of items to one single source, which would not only grant access to the full context of the taboo words, but also some coherence in linguistic patterns. We used an existing taboo word database built for an MA thesis (Lacroix 2021). The criteria for the selection of items were frequency and heterogeneity: we chose very common taboo words (rather than idiosyncrasies), that would also reflect variation at formal (independent clauses, noun phrases), functional (insults, expletives) and dialectal levels (European Spanish, Argentinian). In the end, the comprehension test included 14 items2 presented within extracts from “La casa de papel”, in the form of short sentences, in order to provide some context for the taboo expression. The sentences were followed by the name of the character that uttered them. Participants were asked to indicate the meaning of the taboo word in question in French and explain the reasons according to which they did not manage to explain the meaning, if this was the case, as shown in this excerpt.

Ya sé que nos ha estado escuchando, pedazo de cabrón [Coronel Luis Tamayo]

Sens: ______________________________________________________________________

Au cas où vous n’avez pas répondu à la question, veuillez indiquer pourquoi:

☐ je ne connais pas le mot/l’expression.

☐ je crois connaître le mot/l’expression mais je ne sais pas l’expliquer.

Engl.

I know you’ve been listening to us, you piece of asshole. [Colonel Luis Tamayo]

Meaning: ___________________________________________________________________

In case you haven’t answered the question, please indicate why:

☐ I don’t know the word/expression.

☐ I believe I know the word/expression, but I can’t explain it.

Prior to completing the 14 items of the comprehension test, participants were provided with a written example to ensure clarity on the expected responses, thereby enhancing the measure’s reliability. The questionnaire contained further questions regarding participants’ linguistic biography (L1(s), other languages, years of learning Spanish, self-assessed Spanish proficiency level, stay-abroad experience), the exposure to the series (seasons watched, when, whether they watched the series in Spanish and the language of the subtitles, if applicable). Also, participants used a 6-point Likert-scale (strongly disagree—strongly agree) to rate a series of statements: Attitudes towards contextual constraints in the use of swear words (1. I feel uncomfortable when my conversation partners use swear words, 2. I believe the use of swear words in a public context is acceptable, 3. I think swear words enhance expressive capability in certain contexts) and attitudes towards the use of swear words based on sociolinguistic features of the user (1. I believe that individuals with a lower socioeconomic status use swear words more frequently, 2. I believe that individuals with lower educational levels use swear words more frequently, 3. I believe that women use swear words less frequently than men). Finally, participants also reported on their own use of swear words depending on the context (private, public, etc.).

2.3. Procedure

The study was conducted within the context of two courses, one focused on Spanish pragmatics for Linguistics students, and another about Spanish culture for Translation and Interpreting students. Prior to their participation, all individuals received a consent letter, which they were requested to sign before proceeding to undertake the comprehension test and the questionnaire. This letter provided a brief overview of the research’s purpose, the procedure, and the nature of the data to be collected, and assured participants of the strict confidentiality and anonymity of all data, which would be used solely for scientific purposes. Additionally, participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point in time, both in writing through the consent letter and verbally by the researchers.

Once the consent letter was signed, participants proceeded to complete the comprehension test and the questionnaire. Since written sentences without any audiovisual content were included in the comprehension test, we used a print version. This also helped minimize the potential for participants to access online dictionaries during the process and thus biasing the results. To further guarantee their anonymity and ensure their comfort when dealing with taboo expressions, participants were instructed to use pseudonyms on the questionnaire instead of their real names.

After the comprehension test and the questionnaire were handed out, a short debriefing took place, during which participants had the opportunity to discuss their experiences with the professor. The entire study, including signing the consent letter, completing the assessments, and debriefing, took approximately 30 min.

2.4. Data Analysis

To evaluate the correctness of learners’ responses to the comprehension test, three independent raters were brought in who were trained in advance on the coding. For each item in the comprehension test, several options were considered correct so as to avoid a strong dichotomy and narrow interpretation. For example, for the following taboo expression “¿Hace falta que te diga que no hay tiempo? ¡Vamos, carajo!” [Palermo] (Engl. Do I need to tell you that there’s no time? Let’s fucking go! [Palermo]), we accepted “merde”, “putain” and “bordel” (literally shit, whore and brothel) as correct responses, whereas “mec”, “batard” and “enculé” (literally dude, bastard and fucked in the ass) were considered to be false. Raters achieved consensus on 85% of the responses, signifying a strong agreement, as per Krippendorff’s Alpha (α = 0.735). In cases of disagreement, thorough discussions were conducted until a consensus on the final coding was reached.

To test the four hypotheses, we conducted a binary logistic regression with random effects (GLMM). The dependent variable was the response to the items (correct | false), and the fixed factors were gender (M | F | X), L1 background (only French | other than only French), stay-abroad experience (yes | no), language proficiency level (high | low), captions (in Spanish with or without captions | in another language than Spanish with or without captions), the time when learners watched the series (simplified: not | < 1 year | > 1 year), the use of swear words (never use | only in private | also in public), attitudes on sociolinguistic variables (grouped median of three scales), and the attitudes on contextual factors (grouped median of three scales).3 An exploratory data analysis revealed a high variability in the proportion of correct responses across the items of the comprehension test. Consequently, we entered the item into the model as a random effect.

Using the forward stepwise regression approach based on Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) model selection, we determined the most appropriate fixed effects model (including main effects and their interactions) from a range of potential models that describe the relationship between all variables initially included in our data. The selected best-fit model accounted for 57.6% of the variation of the correct responses, correctly predicted 83.9% of the cases, incorporated all variables except for the time where learners watched the series and included the two-way interactions gender*L1 background, stay abroad experience*attitudes on sociolinguistic variables, and language proficiency level*captions. The estimated marginal means were used for interpreting the results instead of the descriptive means, since they better represented the average of the response variable based on the best-fit model selected.

3. Results

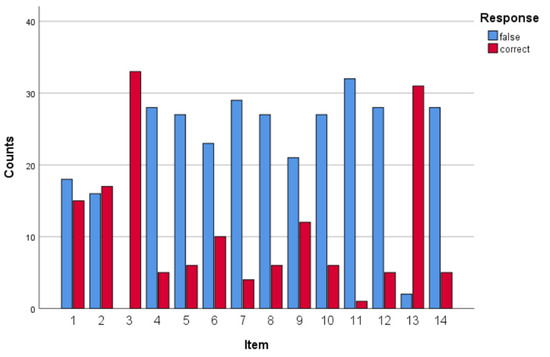

We first analyzed our data by examining the descriptive statistics on a per-item basis, as presented in Figure 1. This analysis unveiled a considerable degree of variability among different items. Notably, we observed a higher proportion of correct responses for items 3 and 13, which centered on expressions with a direct equivalent in French, such as “hijo de puta/fils de pute” (son of a bitch), or those easily accessible through English, such as “joder” (fuck) (“merde”). In contrast, a higher proportion of incorrect responses was noted for items such as 11 and 12, which encompassed forms typically associated with Argentinian Spanish, like “carajo” or “boludo”, which the students seemed to be less familiar with. Interestingly, it was observed that students knew the referential use of the target expressions in item 14 (e.g., “cojones”—balls—“Qué cojones hacen aquí esos blindados”—‘What the hell are those armored guys doing here’) and item 6 (e.g., “hostias”, Engl. blows), but struggled with the non-referential use of these expressions.

Figure 1.

Absolute counts for correct and false answers by item (1 to 14).

In the next step, we conducted a binary logistic regression with random effects (GLMM) based on the best-fit model selected for the main effects and their interactions, as outlined in Section 2.4. Since we used incorrect responses (0) as our baseline in order to predict correct responses (1) as a target, higher Estimated Marginal Means (EMMs) indicated a higher probability of answering correctly and thus a higher understanding of Spanish taboo words. For each hypothesis, we will present the results based on the descriptive and inferential statistics, respectively.

The results indicate that the language in which participants watched the TV series had an influence on the comprehension of taboo expressions (Hypothesis 1), with Spanish with or without captions demonstrating a facilitative effect (Spanish with or without captions EMM = 0.431, SE (Standard Error) = 0.209 vs. other languages EMM = 0.308, SE = 0.230). Nevertheless, the logistic regression analysis revealed that the different proportion of correct responses between the two levels of the variable was not statistically significant (F(1, 305) = 0.186, p = 0.666).

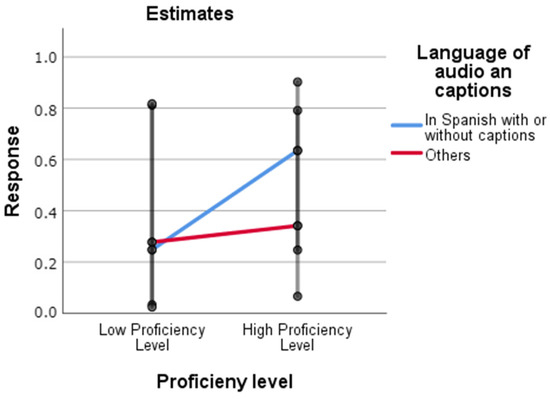

Regarding the effect of variables related to language learning on the comprehension of taboo expressions (Hypothesis 2), we found that the proficiency level in Spanish as a foreign language and experience gained through studying abroad affected students’ comprehension of taboo expressions. As for proficiency, students with a higher level (EMM = 0.487, SE = 0.216) scored better than those with a lower level (M = 0.262, SE = 0.160). Moreover, a stay-abroad experience was associated with a higher proportion of correct responses in interpreting taboo words (stay abroad M = 0.475, no stay abroad M = 0.766). However, these results did not reach significance (stay-abroad experience: F(1, 305) = 3.045, p = 0.082, language proficiency level: F(1, 305) = 1.658, p = 0.199). Furthermore, the analysis of the interaction between the proficiency level in Spanish (high vs. low) and the language in which they watched the series (Spanish vs. other languages) revealed that learners with higher proficiency levels that watched the series in Spanish with or without subtitles performed better (M = 0.635, SE = 0.197) than those who watched it in another language (M = 0.341, SE = 0.227). This difference did not exist for learners with a lower level, independently of the language in which they watched the series (Spanish M = 0.752 or other M = 0.723) (see Figure 2). The binary logistic regression, however, found these differences to be statistically nonsignificant (F(1, 305) = 0.708, p = 0.401).

Figure 2.

Estimated marginal means of responses (0 false; 1 correct) by language of audio and captions and proficiency level (high vs. low).

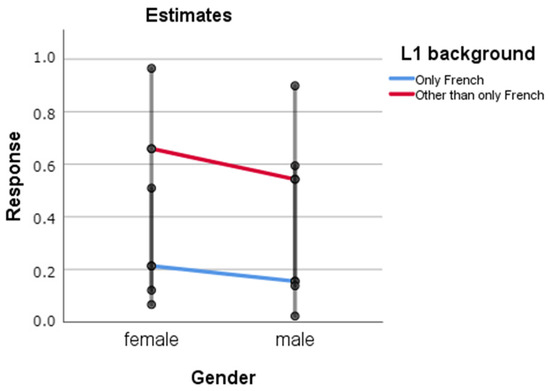

We also investigated whether individual factors, such as gender and L1 background, influenced the performance of the students (Hypothesis 3). The results indicate that gender had only a minimal effect, as female students exhibited a higher proportion of correct responses (EMM = 0.420, SE = 0.208) compared to male students (EMM = 0.318, SE = 0.192). Consequently, this difference was found to be statistically nonsignificant (F(1, 305) = 0.708, p = 0.401). Regarding the students’ L1 background, learners who had L1 languages other than only French (Spanish n = 1, Polish n = 2, and Romanian n = 1) were associated with a higher proportion of correct responses (EMM = 0.602, SE = 0.227) compared to those who had only French as L1 (EMM = 0.182, SE = 0.110). The binary logistic regression revealed a significant fixed effect of L1 background on the outcome variable (F(1, 305) = 5.946, p = 0.015). If we look into the interaction effects between both individual factors, we can observe a similar effect of the L1 background both in male and female students (see Figure 3). No significant fixed effect was found for this interaction (F(1, 305) = 0.003, p = 0.957).

Figure 3.

Estimated marginal means of response (0 false; 1 correct) by gender and learners’ background L1.

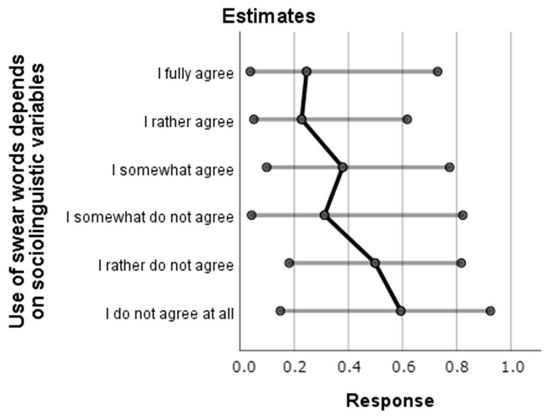

The results are also consistent with our last hypothesis (Hypothesis 4), in the sense that learners’ attitudes towards the use of taboo expressions, including context-related and sociolinguistic aspects, influence the comprehension of taboo expressions. On the one hand, as to the attitudes towards the effect of the context, those students that agreed on the role of the conversational context outperformed those that somewhat agreed or did not agree at all. In other words, an increased awareness of the context-dependent use of taboo expressions went along with an increased proportion of correct responses (Rather agree and fully agree EMM = 0.566, SE = 0.243, somewhat in between M = 0.464, SE = 0.222, I do not agree and I rather do not agree M = 0.148, SE = 0.099). The fixed effect was found to be significant (F(2, 305) = 3.947, p = 0.020), with the level somewhat in between having 16.181 times the odds of having a correct answer compared to the level I do not agree and I rather do not agree (β = 2.784, p = 0.000, 95% CI 3.630, 72.126). On the other hand, attitudes toward the impact of sociolinguistic aspects on taboo use exhibited a consistent pattern overall: The more individuals agreed with the influence of sociolinguistic variables (such as lower socioeconomic status or lower education level) on the frequency of taboo use, the fewer correct responses they produced (see Figure 4). However, no significant fixed effect was found for this factor (F(5, 305) = 3.947, p = 0.244).

Figure 4.

Estimated marginal means of response (0 false; 1 correct) by attitudes towards the influence of sociolinguistic variables on swear word use.

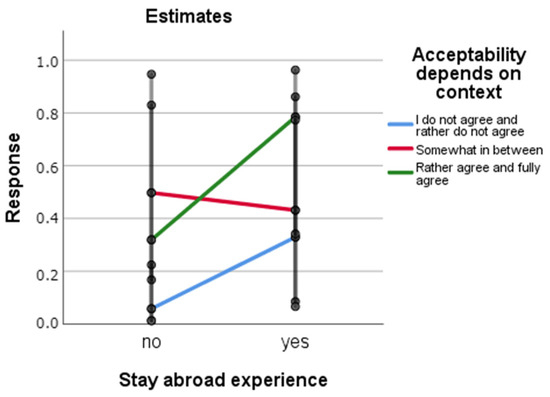

Finally, we looked into the interaction between the attitudes towards the context and the stay-abroad experience. The results reveal two different patterns between those with and without stay-abroad experience with regard to their opinion on the context-relatedness of using taboo expressions: Students with stronger opinions on the context-relatedness of using taboo expressions (cf. Rather agree and fully agree and I do not agree and I rather do not agree) had a remarkably higher proportion of correct responses if they had stay-abroad experience compared to those without stay-abroad experience. However, the stay-abroad experience did not affect the proportion of correct responses of students with less strong opinions (cf. somewhat in between) (see Figure 5). The binary logistic regression revealed no significant fixed effect for the interaction (F(2, 305) = 2.864, p = 0.059).

Figure 5.

Estimated marginal means of response (0 false; 1 correct) by stay-abroad experience and the attitudes towards the influence of contextual variables on swear word use.

4. Discussion

It is worth starting this discussion with a general comment on the overall responsiveness of the learners. Irrespective of whether participants responded correctly or not, they actively engaged in creating coherence from the stimuli presented in the test and employed a diverse range of strategies to deal with cross-linguistic variation. In many cases, participants sought direct equivalents, whenever possible. For instance, for “hijo de puta” (French: “fils de pute”, English: “son of a bitch”), participants readily found direct L1 equivalents. For target expressions where a direct equivalent was unavailable, participants delved into their repertoire of taboo words in their L1 and incorporated elements of the target expression. For instance, in the case of “me cago en Dios” (‘I shit on God’), participants generated various adaptations based on God (“Dieu”) and/or shit (“merde”, “chier”), such as “nom de Dieu”, “Bon dieu de merde”, “bordel de merde”, “ça me fait chier”, “A Dieu”, “j’emmerde Dieu”, “je n’en ai rien à foutre de Dieu”, “je chie sur Dieu”, “je me chie dessus”, among others. As was mentioned before, the correctness of these responses—in the sense of pragmatic equivalence with the examples in the item in a very broad way—was assessed by three independent evaluators.

There are a variety of factors that can play a role in the acquisition of a foreign language, and some may take a particular direction when learning taboo words. The goal of this study was precisely to gain a better understanding about what may significantly help our students understand taboo words. In light of the findings from research into both language acquisition and linguistic taboo, we proposed a number of hypotheses.

Based on the results of this study, we could not confirm the first two hypotheses: although the results went in the expected directions according to previous studies, we found no significant effect on the comprehension of taboo words for the conditions while watching the series (namely, the language in which they watched the series and the presence of subtitles) (Hypothesis 1). Although one might think that watching the series in Spanish might help in learning taboos (and that seems to be the case, but not significantly), it is not enough in itself, and that might be for several reasons. First, watching the series without performing any concrete exercises may not be enough to activate knowledge about taboo words. Second, it is possible that the lack of written support hinders the expected beneficial effect of exposure to the spoken language, even if they watched it with subtitles. It is important to note that, although in Spanish subtitles in Spain, the tendency is to faithfully reproduce taboos (Ávila-Cabrera 2023), sometimes they may be omitted due to condensation or other reasons such as self-censorship or specific requests from the client (Ávila-Cabrera 2024). In other languages, though, the situation is quite different and taboo language tends to be avoided in the subtitles, which leads to a lack of written support. For instance, in a study about subtitling of the series in Arabic, the authors found that several of the taboo words studied here (what we consider non-referential) were typically omitted in the subtitles (Essayahi and Aloune 2022). Although we cannot know for certain, it is a possibility that some taboos were not maintained in the subtitles that our students read, especially when they chose languages other than Spanish. This might explain our results, according to which participants watching the series with captions other than Spanish performed worse on the comprehension test. However, further investigation about the overall maintenance of taboos in the subtitles of the series through a controlled experiment would help substantiate this interpretation.

Moreover, we did not find a significant effect of students’ proficiency in Spanish or the experience gained through a stay abroad on the responses (Hypothesis 2), even though both variables did increase the proportion of correct results. The lack of significance might push further a reflection that was brought up in the introduction: in previous studies, a stay abroad had significant effects on the interpretation of sexual metaphors (De Cock and Suñer 2018), but not on other, more formal registers (Suñer 2019), which was interpreted as a difference in the knowledge resources and strategies that students mobilize for processing taboo language as compared to more formal registers. Here, although we found that the stay-abroad experience helps, it does not reach significance when interpreting taboo language. It is worth reiterating that the items in this study were all non-referential (insults, expletives), which very often convey pragmatic rather than conceptual meanings and have, therefore, an added layer of difficulty for which—it seems—the students’ proficiency level or a short stay abroad might not be significantly helpful. This is not surprising if we consider that taboo words are not mentioned in Spanish teaching materials until the most advanced levels (C1), as studied by Mayo Martín (2017), despite the recommendations of the CEFR. Students at the levels included in this study have possibly been very rarely exposed to taboo words in the classroom, and a short stay abroad has not provided enough exposure to make a statistical difference. The fact that the participants with a higher proficiency level and having spent a stay abroad outperformed their counterparts (although not significantly) seems to point to a logical positive evolution further down their learning path. Therefore, we encourage future research to include students at MA level so as to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how both of those variables interact.

As for our Hypotheses 3 and 4, we did find significant results: the linguistic background, namely the L1 of the student, and their attitudes towards the acceptability of taboo words, depending on the context, reached statistical significance and can be, therefore, confidently discussed as having had an effect on the correctness of the answers in our study.

Despite the similarities between French and Spanish, being an L1 speaker of French does not help for the comprehension of taboo words in Spanish. The four students who had an L1 other than only French had Spanish (n = 1), Polish (n = 2) and Romanian (n = 1). The knowledge of L1 Spanish requires no further comment, since it is expected that their comprehension of taboos in their own language would be better than for the rest of the students. However, the other two languages are either not connected to Spanish (in the case of Polish) or have a less direct connection (in the case of Romanian, which is a Romance language). In this context, guessing the meaning of unknown words can be modulated by cross-linguistic differences between the L1 and the L2 (or other Ln) and result in positive or negative lexical transfer (cf. Agustín-Llach 2020). This could explain why, in some cases in our study, participants sought equivalents and/or cognates, even when they were not readily available. For instance, in the case of “coño” (English: pussy), participants mistakenly attempted to find a translation like French “con” (English: fool) based on formal similarities with “coño”,4 which resulted in an inaccurate rendering. In this case, the fact of having an L1 other than French seemed to help to avoid the mistake, possibly because they did not fall into the trap of the false cognates. From a pedagogical point of view, this underlines the importance of taking the cognitive impact of the L1 into account when teaching taboo words. Exercises based on the contrastive analysis of taboo words in context and their semantic and pragmatic meanings in the L1 and the L2 may facilitate the emergence of particularly difficult taboo words for certain learners.

As for Hypothesis 4, it is well-established that the use of taboo language is subject to linguistic ideologies that vary through societies (Andersson and Trudgill 1992, p. 49; Allan and Burridge 2006, pp. 105, 239). In this sense, the acceptability of taboo language use in particular contexts varies among different speakers. This has been studied in the context of the L1, where it is observed, for instance, that speakers who consider themselves more prudish, in the sense that they consider talking about sexuality a private matter, have a tendency to use more indirect expressions when referring to sexual concepts (Pizarro Pedraza 2022). In the context of the L2, a stronger reticence to discuss sexual topics is also associated with poorer comprehension of sexual taboo language (Suñer and De Cock 2023). In this study, we found similar results: learners that have more positive attitudes towards taboo words (they do not find it disagreeable when others use taboo words, they accept them in public contexts, and they think that taboo words contribute to expressiveness in certain contexts) seem to learn them more easily than those who reject them. Logically, learners that reject taboos may put less effort into adding them to their repertoire or downright resist adding them to their repertoire. This suggests that, when teaching taboo words, it is important to take these attitudes into account and explain the actual frequency of taboo words in Spanish, their pragmatic functions, and their expressive capacities, as well as to clarify that their non-referential use does not necessarily imply talking about taboo topics. The effects of reticence affect the production of taboo words by L1 speakers, but in no way do they limit their comprehension of the semantic or pragmatic meanings of taboo words. This is not the case with the L2 learners: reticence towards taboos also affects their comprehension since they lack the natural exposure of L1 speakers, and this may lead to important misunderstandings. By teaching taboo words, the goal is not to instruct our learners that they should use them, but that they should be able to interpret them in context. In fact, the same taboo word (for instance, “cabrón”, ‘fucker’) may be used as praise or as an insult. Being able to fully understand the meaning of such an utterance is, therefore, crucial in order to avoid critical incidents in their interactions that may originate from the context-dependent pragmatic meaning of particular taboo words.

5. Conclusions

This study had the goal of contributing to a better understanding of the individual factors that affect students’ comprehension of swear words within the context of learning Spanish as a foreign language, particularly through Spanish TV series. Although most predictors had an influence in the expected direction, only two reached significance: participants with an L1 other than only French and those with positive attitudes towards the use of taboo words performed significantly better in interpreting the items in the study.

The interpretation of the results leads to a number of pedagogical reflections: it is important to recognize that a sufficient understanding and appropriate use of swear words can be a valuable tool for preventing critical incidents in intercultural contexts. Therefore, in order to further promote language development and social engagement with language (Alm 2023a), it would be recommendable to actively include real examples of their use in context from early on in the students’ learning path, with a focus on the pragmatic interpretation of the swear words. Moreover, in light of the results, particular attention should be paid to the potential cognitive effect of the L1 on the acquisition of taboo words: explicit reflection through contrastive exercises might help learners understand the connections between taboo word repertoires in the L1 and the L2, the existence of potential false friends and the pragmatic equivalents in the foreign language.

Additionally, once again, attitudes towards taboo words have been shown to have an important effect on their understanding and production. As much as possible, it should be taken into account that learners that are reticent towards taboo words may face more difficulties in acquiring them, among others, due to lack of exposure. For this group, who will not learn taboo words out of their own motivation, it is particularly important to give them enough tools to interpret their meanings in context, without necessarily encouraging their use.

The exploratory nature of this study has shown both limitations and promising results that call for a more controlled experiment, in order to better analyze aspects such as the effect on taboo word acquisition of the maintenance, omission or manipulation of taboo words in subtitles. Moreover, when examining the impact of series on language development, it would be worthwhile to differentiate between students specializing in translation versus those studying linguistics and literature. Although we did not include this factor in the model, the two groups of students seem to show different resources when looking for equivalents of taboo words. Indeed, the kind of skills that are taught in linguistics and translation may affect the way in which the L2 teaching is approached. Additionally, it would be beneficial to explore the effects of other TV series, such as “Chicas del cable”, on other pragmatic phenomena. For instance, this could include an investigation into how this series, set in the strongly hierarchical contexts of a telephone company, influences politeness strategies, particularly in hierarchical situations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/languages9030074/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, review and editing, visualization: A.P.P., F.S. and B.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institut Langage et Communication at the Université catholique de Louvain (Reference CE-ILC/2023/11, date of approval: 6 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Geneviève Maubille and Julie Schwarz for their help in the earlier stages of the response evaluation process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The questionnaire and the test are available in the Supplementary. |

| 2 | The 14 items are “pedazo de cabrón” ‘piece of asshole’, “gilipollas” ‘jerk’, “hijos de puta” ‘sons of a bitch’, “capullo” ‘moron’, “boludo” ‘moron’, “coño” ‘fuck’, “joder” ‘fuck’, “hostias” ’fuck’, “me cago en Dios” ‘Jesus Fucking Christ’, “carajo” ‘fuck’, “la concha de tu madre” ‘motherfucker’, “la madre que los parió” ‘sons of a bitch’, “puto” ‘fucking’ and “(qué) cojones” ‘(what) the hell’. Most of these items are polysemous and may have several equivalents in English. The translations provided here correspond to the contexts given to the students and are just illustrative. |

| 3 | For the attitudes about the sociolinguistic variables, the statements were formulated based on stereotypes related to taboo language (women use it less, while people with a lower education level and people with lower socioeconomic status use it more). The responses to the particular questions about sociolinguistic variables showed significant collinearity in the sense that students who showed (dis)agreement with one of the statements tended to show the same opinion for the other two statements, pointing to a certain coherence in the attitudes towards the stereotypes. Due to this collinearity, we decided to group the original 6-point scale on three different answers. |

| 4 | Although “con” and “coño” both evolved from the latin cunnus (vulva), the meaning of “con” nowadays has lost the connection to the historical meaning and is not a synchronic equivalent of “coño”. |

References

- Agustín-Llach, María Pilar. 2020. Semantic and Conceptual Transfer in FL: Multicultural and Multilingual Competences. In Vocabulary in Curriculum Planning: Needs, Strategies and Tools. Edited by Marina Dodigovic and María Pilar Agustín-Llach. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 165–80. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, Keith, and Kate Burridge. 1991. Euphemism and Dysphemism. Language Used as Shield and Weapon. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, Keith, and Kate Burridge. 2006. Forbidden Words. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, Antonie. 2023a. Engaging with L2 Netflix: Two in(tra)formal learning trajectories. In Language Learning and Leisure: Informal Language Learning in the Digital Age. Edited by Denyze Toffoli, Geoffrey Socket and Meril Kusyk. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 379–408. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, Antonie. 2023b. Lockdown with La Casa de Papel: From Social Isolation to Social Engagement with Language. In Technology-Enhanced Language Teaching and Learning: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Edited by Karim Sadeghi, Michael Thomas and Farah Ghaderi. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 121–35. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, Lars-Gunnar, and Peter Trudgill. 1992. Bad Language. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Cabrera, José Javier. 2023. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood: Analysis of dubbed and subtitled insults into European Spanish. Journal of Pragmatics 217: 188–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Cabrera, José Javier. 2024. Taboo. ENTI (Encyclopedia of Translation and Interpreting). AIETI. Available online: https://www.aieti.eu/enti/taboo_ENG (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Beers-Fägersten, Kristy. 2012. Who’s Swearing Now?: The Social Aspects of Conversational Swearing. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Casas Gómez, Miguel. 2023. La expresión del tabú: Conceptualizaciones y etapas en la evolución lingüística del fenómeno. LinRed XX. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Cock, Barbara, and Ferran Suñer. 2018. The influence of conceptual differences on processing taboo metaphors in the foreign language. In Linguistic Taboo Revisited. Novel Insights from Cognitive Perspectives. Edited by Andrea Pizarro Pedraza. Cognitive Linguistics Research Series (CLR); Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 379–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2004. Blistering barnacles! What language do multilinguals swear in? Estudios de Sociolingüística 5: 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2005. The effect of type of acquisition context on perception and self-reported use of swearwords in L2, L3, L4 and L5. In Investigations in Instructed Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Alex Housen and Michel Pierrard. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 531–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, Jean-Marc. 2016. Thirty shades of offensiveness: L1 and LX English users’ understanding, perception and self-reported use of negative emotion-laden words. Journal of Pragmatics 94: 112–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, Patricia A. 2019. Social Dimensions and Processes in Second Language Acquisition: Multilingual Socialization in Transnational Contexts. The Modern Language Journal 103: 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essayahi, Moulay Lahssan Baya, and Ahlam Bachiri Aloune. 2022. Aproximación a la traducción del lenguaje tabú y ofensivo al árabe. Estudio y análisis de la serie ‘La casa de papel’. Hikma 21: 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, Shlomit Ritz. 2018. Swearing as emotion acts: Lessons from Tourette syndrome. In Linguistic Taboo Revisited: Novel Insights from Cognitive Perspectives. Edited by Andrea Pizarro Pedraza. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 311–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, Eileen. 2017. Swearing: The good, the bad & the ugly. ORTESOL Journal 34: 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Bruce. 2010. Pragmatic competence: The case of hedging. In New Approaches to Hedging. Edited by Gunther Kaltenböck, Wiltrud Mihatsch and Stefan Schneider. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Reigosa, Fernando. 1976. The anxiety arousing effect of taboo words in bilinguals. In Cross-cultural anxiety. Edited by Charles D. Spielberger and Rogelio Diaz-Guerrero. Washington, DC: Hemisphere, pp. 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Timothy. 2009. The Utility and Ubiquity of Taboo words. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2: 153–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacroix, Rénald. 2021. Usos del lenguaje malsonante en la serie La casa de papel: Análisis de la evolución de las categorías y funciones del uso emocional de las expresiones malsonantes. Unpublished Master’s thesis, UC Louvain, Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. Available online: https://dial-uclouvain-be.proxy.bib.uclouvain.be:2443/memoire/ucl/object/thesis:31881 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Liao, Sixin, Jan Louis Kruger, and Stephen Doherty. 2020. The impact of monolingual and bilingual subtitles on visual attention, cognitive load, and comprehension. The Journal of Specialised Translation 33: 70–98. [Google Scholar]

- Luque, Juan de Dios, Antonio Pamies, and Francisco José Manón. 2017. Diccionario del insulto. Barcelona: Ediciones Península. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, Paula Mayo. 2017. Estudio sobre expresiones metafóricas tabú de uso frecuente para su aplicación a la enseñanza de español como lengua extranjera. E-eleando 5. Available online: https://ebuah.uah.es/dspace/bitstream/handle/10017/34639/estudio_mayo_eleando_2017_N5.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Peters, Elke, and Carmen Muñoz. 2020. Introduction to Special Issue Language Learning from Multimodal Input. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 42: 489–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro Pedraza, Andrea, ed. 2018. Linguistic Taboo Revisited. Novel Insights from Cognitive Perspectives. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, vol. 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro Pedraza, Andrea. 2022. Sociolinguistic factors in the preference for direct and indirect expression of sexual concepts. In The Routledge Handbook of Variationist Approaches to Spanish. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos. London: Routledge, pp. 582–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro Pedraza, Andrea, and Eva González Melón. 2018. El conocimiento de palabras tabú en español: una aproximación léxico-pragmática en estudiantes belgas flamencos de Lingüística Aplicada. Paper presented at the XXXVI Congreso internacional de AESLA, University of Cádiz, Puerto Real, Spain, April 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Suñer, Ferran. 2019. Exploring the Relationship between Stay-abroad Experiences, Frequency Effects, and Context Use in L2 Idiom Comprehension. Journal of Language Teaching and Research 10: 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suñer, Ferran, and Barbara De Cock. 2023. The role of reticence in language learners’ comprehension of metaphorical taboo expressions. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).