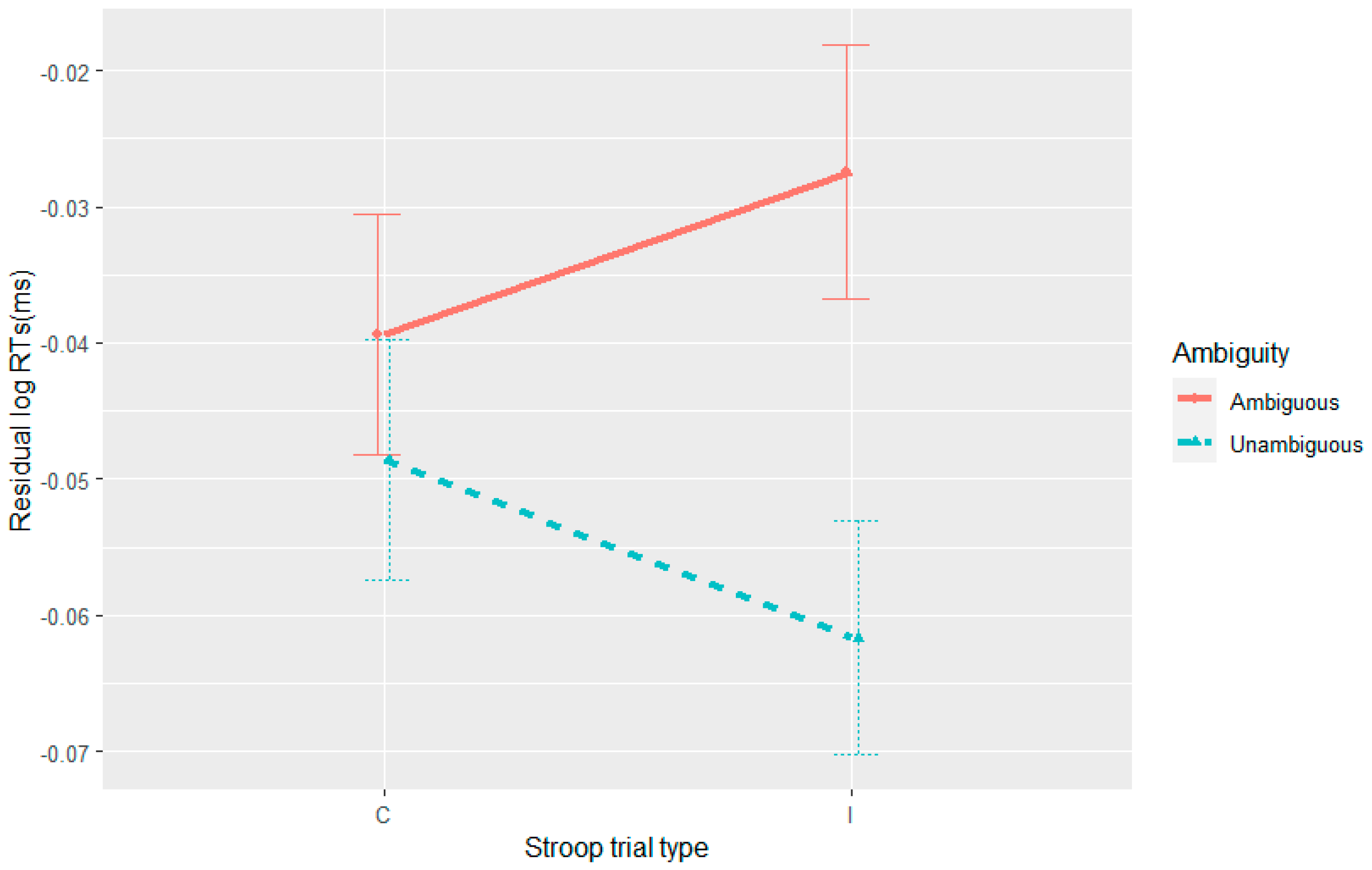

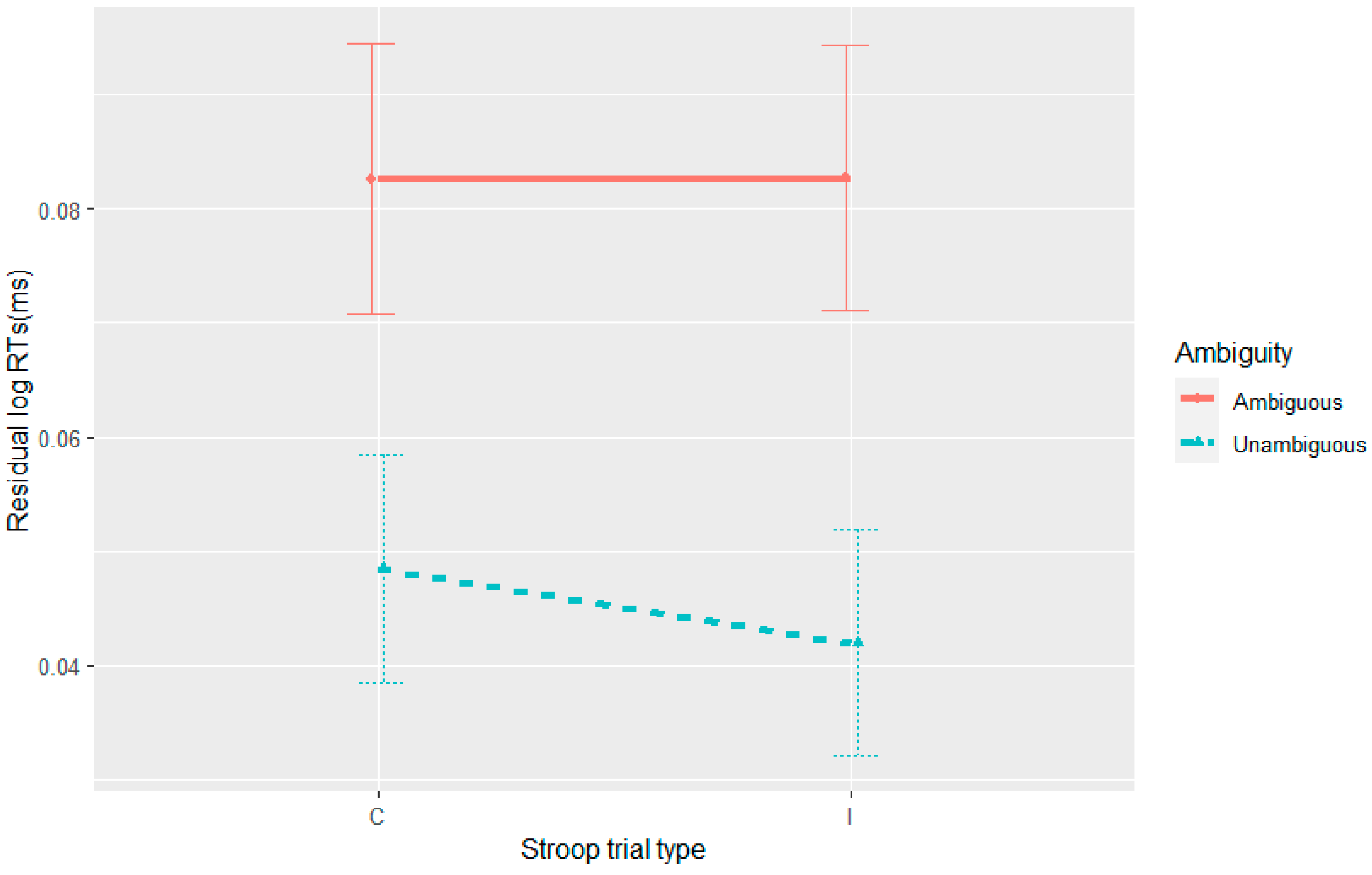

The current set of four experiments aimed to merge work on adaptation with garden-path processing over different time scales: trial and experiment. At the trial level, adaptation has been attributed to residual activation of a conflict monitoring mechanism from the preceding trial/stimulus (

Hsu and Novick 2016). At the experiment level, it has largely been assumed to be due to implicit learning by (a) mechanism(s) operating over incremental exposure to garden-path sentences (

Fine and Jaeger 2016;

Fine et al. 2013;

Prasad and Linzen 2021;

Yan and Jaeger 2020). There has been debate as to what mechanisms can learn on the longer timescale: the parser’s assignment of probability to the temporarily ambiguous parses (

Fine and Jaeger 2016;

Fine et al. 2013), the parser’s ability to revise the incorrect parse (

Yan and Jaeger 2020), task-based learning (

Prasad and Linzen 2021), or a domain-general cognitive control mechanism that assists with detecting conflict and conducting revision (

Hsu et al. 2021;

Hsu and Novick 2016;

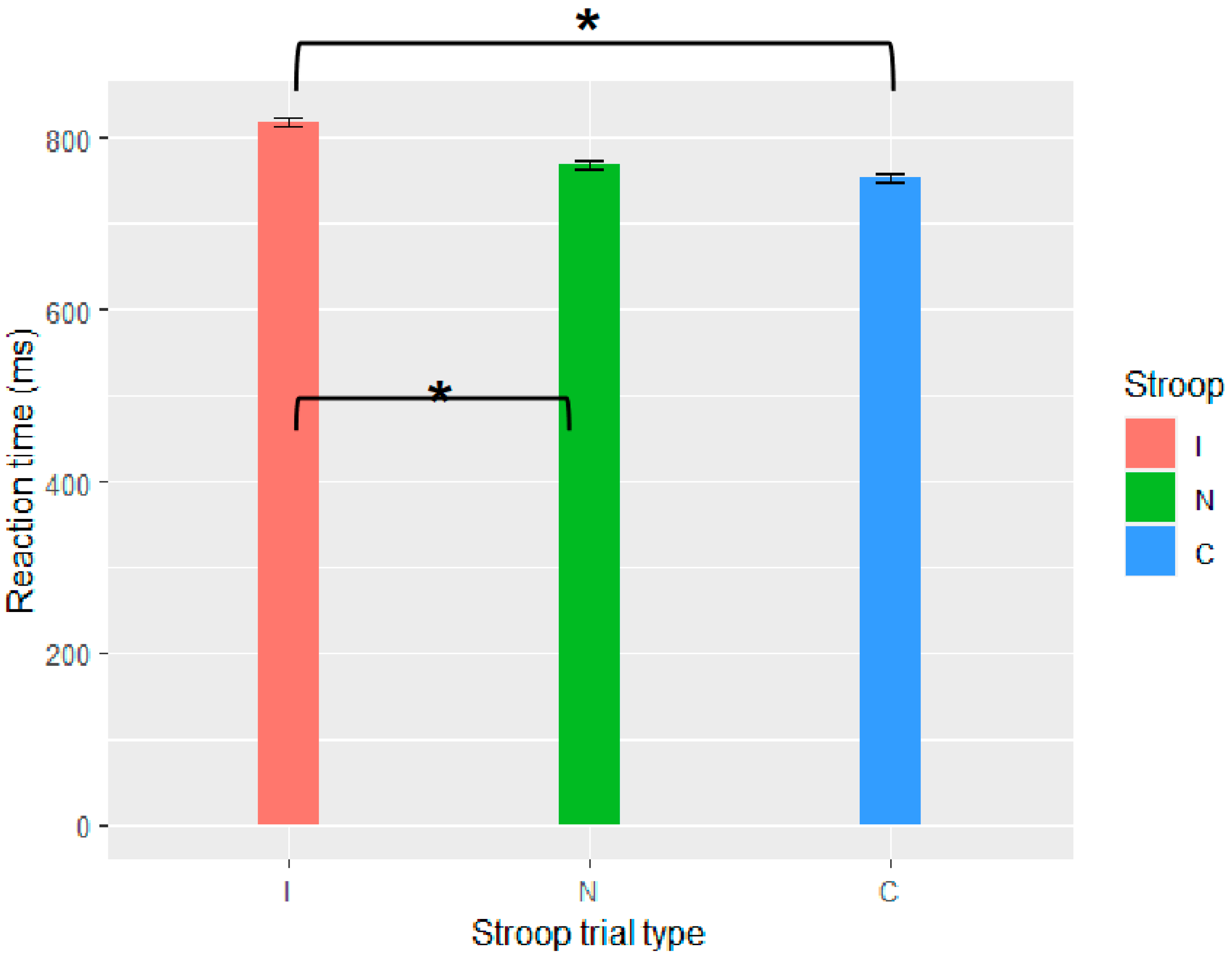

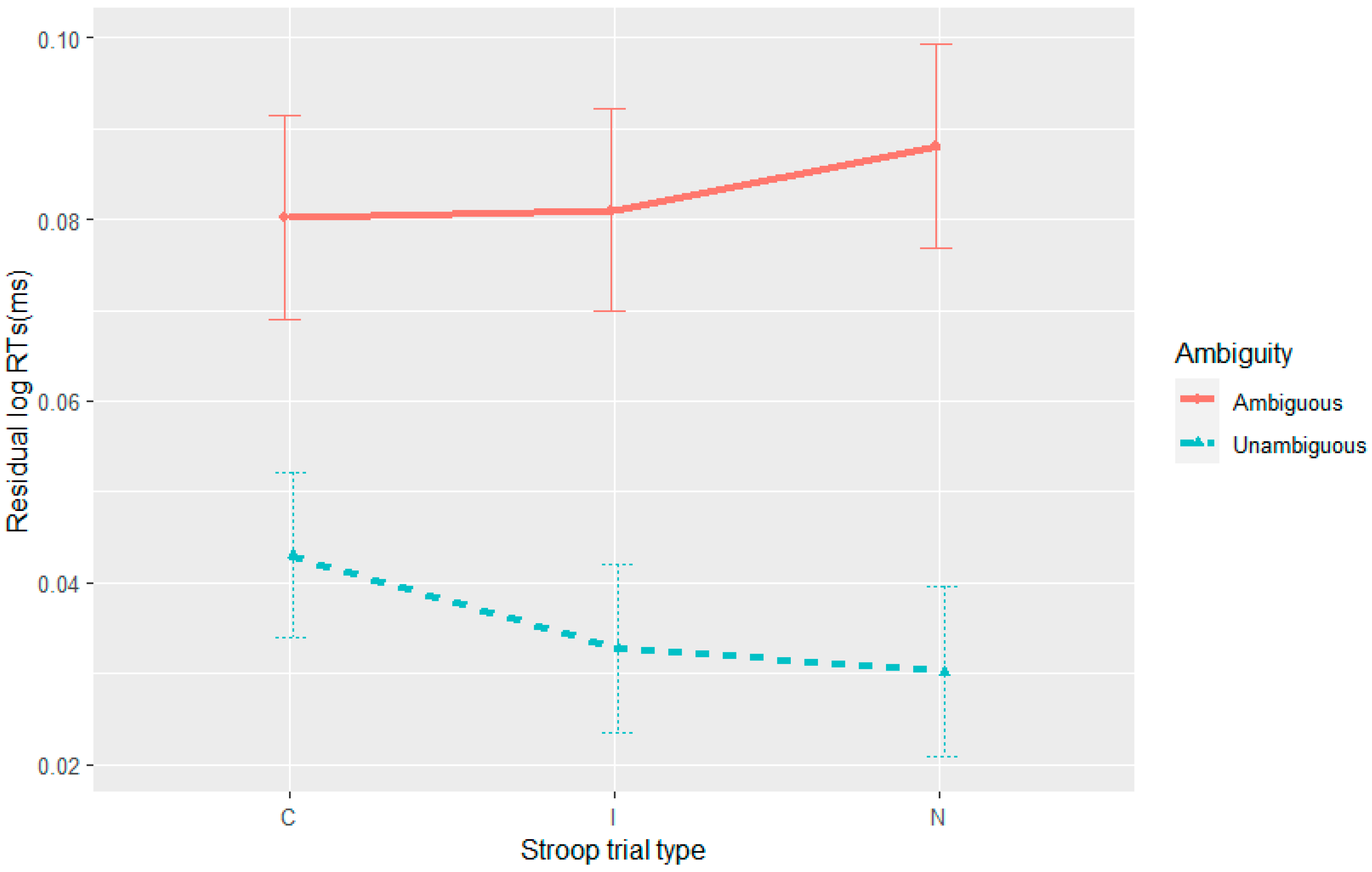

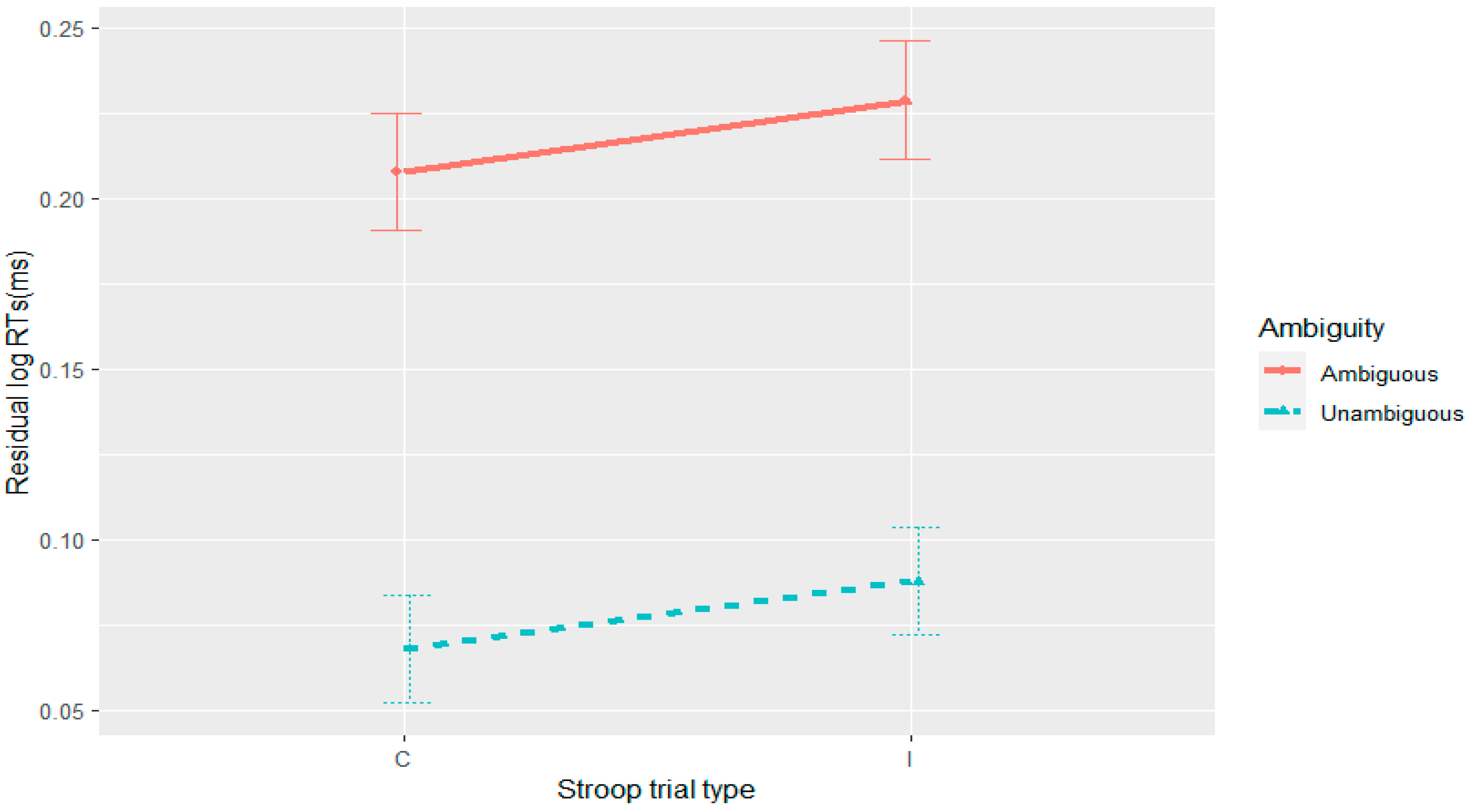

Sharer and Thothathiri 2020). The strength of a domain-general conflict monitoring mechanism comes from it being commensurate with facilitated garden-path processing, both from trial-to-trial and over longer periods of exposure. A limitation of this work is that the trial-to-trial findings depend on the visual world paradigm which does not necessarily directly measure syntactic processing. Thus, we used two reading paradigms that avoid an interaction with visual object processing—self-paced reading and standard reading under full-sentence presentation. If a domain-general conflict-based cognitive control mechanism is underlying both trial- and experiment-level adaptation effects, we predicted we would observe a reduction in the ambiguity effect at the disambiguating region when the preceding Stroop condition was incongruent, and we expected the ambiguity effect to decrease over the course of the experiment. We failed to find evidence of conflict adaptation in each of the four experiments, despite the manipulation of sentence ambiguity and Stroop congruency being successful, as evidenced by the standard Stroop and ambiguity effects. Likewise, we observed syntactic adaptation across Experiments 1–3 where it was predicted.

7.1. Conflict Adaptation

A null effect of conflict adaptation is difficult to argue for; however, there are a few arguments that seem relevant. First, these were high-powered experiments (Exp. 1,

n = 96; Exp. 2,

n = 168; Exp. 3,

n = 176; Exp. 4,

n = 122) relative to the original work demonstrating conflict adaptation in sentence processing (

n = 41 in

Kan et al. 2013;

n = 23 in

Hsu and Novick 2016;

n = 26 in

Hsu et al. 2021). Second, in Experiment 4, we used the same garden-path stimuli as

Hsu and Novick (

2016), as well as the same principles of design for the fillers, and did not observe the effect. The fourth experiment also did not result in syntactic adaptation in reading times given the design of the fillers, such that one cannot argue that conflict adaptation disappears or weakens with syntactic adaptation. This is further supported by the absence of a three-way interaction between Stroop, ambiguity, and experimental item trial in Experiments 1–3. If conflict adaptation were to weaken with syntactic adaptation, one would expect that conflict adaptation would decrease with increasing exposure to the less probable interpretation over the experiment.

Nonetheless, one could always argue that the duration from Stroop offset to disambiguation is longer in our reading experiments than in the sentence listening experiments of

Hsu and Novick (

2016; see

Table 4), and that this could account for our failure to observe conflict adaptation. Indeed, on average the shortest duration across our experiments was 3107 ms, whereas in

Hsu and Novick (

2016) this was calculated to be 2625 ms (see

Table 4). However, studies that have manipulated the ISI in Stroop-to-Stroop trial designs found the adaptation effect only disappeared in the 4000–5000 ms ISI condition (

Egner et al. 2010). Thus, in principle, our duration is within the realms where conflict adaptation has previously been observed. Even if the Stroop-to-disambiguation duration was too long to observe trial-level adaptation in our experiments, we would still expect to observe a simple relationship between Stroop performance and ambiguity resolution. Specifically, we would expect that individuals with a more efficient conflict monitoring mechanism would have both smaller Stroop and ambiguity effects. However, we found no significant correlation between the size of the two effects across all four experiments. In fact, the numerical relationship between Stroop and ambiguity effects was negative, opposite to what was expected. Thus, we fail to provide either the stronger (i.e., conflict adaptation) or weaker evidence (correlation between Stroop and ambiguity effects) for a domain-general cognitive control, couched within the conflict monitoring account, to facilitate garden-path processing.

Finally, with inferential statistics, the absence of evidence does not provide evidence for the lack of an effect, which led us to run a Bayesian analysis to directly test the null hypothesis. Across all four experiments, the Bayes factor provided support for the null hypothesis, both for conflict adaptation and for conflict adaptation interacting with experimental item exposure.

This support for the null hypothesis does not imply that conflict adaptation cannot be found under alternative conditions. Indeed, in the introduction we raised the possibility that the observed conflict adaptation from incongruent Stroop to garden-path processing in prior work (

Hsu et al. 2021;

Hsu and Novick 2016) does not directly arise at the level of syntactic processing but its integration with the visual scene. Thus, it is happening at the level of visual object processing. If that is the case, then those prior results would not provide evidence for a domain-general mechanism per se, as the transfer would be happening from the visual conflict in Stroop to the visual object conflict created by the visual world set-up. Indeed, in Experiment 4 we did not conceptually replicate the conflict adaptation effect when using the same goal-modifier garden-path sentences in the absence of any accompanying visual information. If this argument is on the right track, it is still possible that a common mechanism is being recruited differentially across conflicts in different representational formats. Critically, its recruitment by conflict in one representational format would have no impact on a conflict in another format. Likewise, the ability to resolve conflict in one format would not have implications for its resolution in another. This would at least require some domain-specific constraints and not be compatible with a completely domain-general mechanism.

Future work should look at additional trial-to-trial adaptation effects to better establish when they do or do not occur. Can they occur when the preceding stimulus involves another syntactic conflict (regardless of the specific structure) or are more specific conditions required, such as the same temporarily ambiguous structure or the unambiguous version of the less preferred structure? The latter two cases are also examples of syntactic priming (

Tooley and Bock 2014). Syntactic priming is the observation that a sentence is more likely to be produced with the same structure as the preceding sentence(s) or to be read faster when it has the same structure as the preceding sentence(s). In syntactic priming experiments, an initial sentence is presented (i.e., the prime) in one of several possible syntactic structures and a following sentence (i.e., the target) is either produced or comprehended by the participants. Most relevant to the current work is a recent study that found priming of the reduced relative structure in reading time measures, when the prime was a reduced relative clause compared to a MC (

Tooley 2020). Priming has been interpreted as being due to either continued activation of the primed structure and/or error signalling, that is, the updating of mental syntactic models in response to a surprising sentence structure (up-regulating the surprising structure) (

Chang et al. 2006;

Tooley 2023). Rather than conflict-monitoring mechanisms remaining active from the prime, it is argued that activation of the syntactic structure of the prime is maintained, which facilitates subsequent processing of the same structure. An alternative account is error updating. It states that in the face of a temporary ambiguity and after receiving an error signal when selecting the incorrect parse an update to parse probabilities occurs, facilitating subsequent production or comprehension of that structure (

Chang et al. 2006). In this way, the mechanism of syntactic priming would strengthen the structure’s representation and could contribute to the cumulative effects of syntactic adaptation observed over an experiment. However, in Tooley’s (

Tooley 2020) recent study the prime (reduced relative clause) and target (reduced relative clause) of the key priming effect were alike both in terms of structure and having a syntactic conflict. Further investigation into different properties of the prime stimulus would shed light on whether trial-to-trial adaptation can occur across independent syntactic conflicts (i.e., syntactic conflict) or when using a consistent structure in the absence of conflict (i.e., pure syntactic priming). The latter could be achieved by using an unambiguous RC vs. MC as prime and an ambiguous reduced relative clause as target (this work is currently underway).

Although we did not observe the expected effect of the Stroop manipulation on sentence processing, in Experiment 3 we did see an effect of Stroop on overall sentence reading times, regardless of ambiguity. This might be consistent with post-incongruent slowing (

Forster and Cho 2014;

Rey-Mermet and Meier 2017;

Verguts et al. 2011). Given this effect was not observed in the self-paced reading experiments, it reinforces the notion that Stroop effects are complex and can interact with the task at hand. As this is not directly affecting our main interest—conflict-monitoring mechanisms facilitating garden path processing—we will leave further interpretation aside.

There were also instances where Stroop affected comprehension accuracy, but these were not in line with the theoretical frameworks under discussion. Other than the ambiguity effect, the effects on accuracy are rather inconsistent across experiments. This seems to be in line with other work looking at comprehension accuracy that varies across individuals and tasks (

Caplan et al. 2013) and may stem from the additional mechanisms that are recruited in answering comprehension questions, including strategies and memory (

Meng and Bader 2021;

Paolazzi et al. 2019).

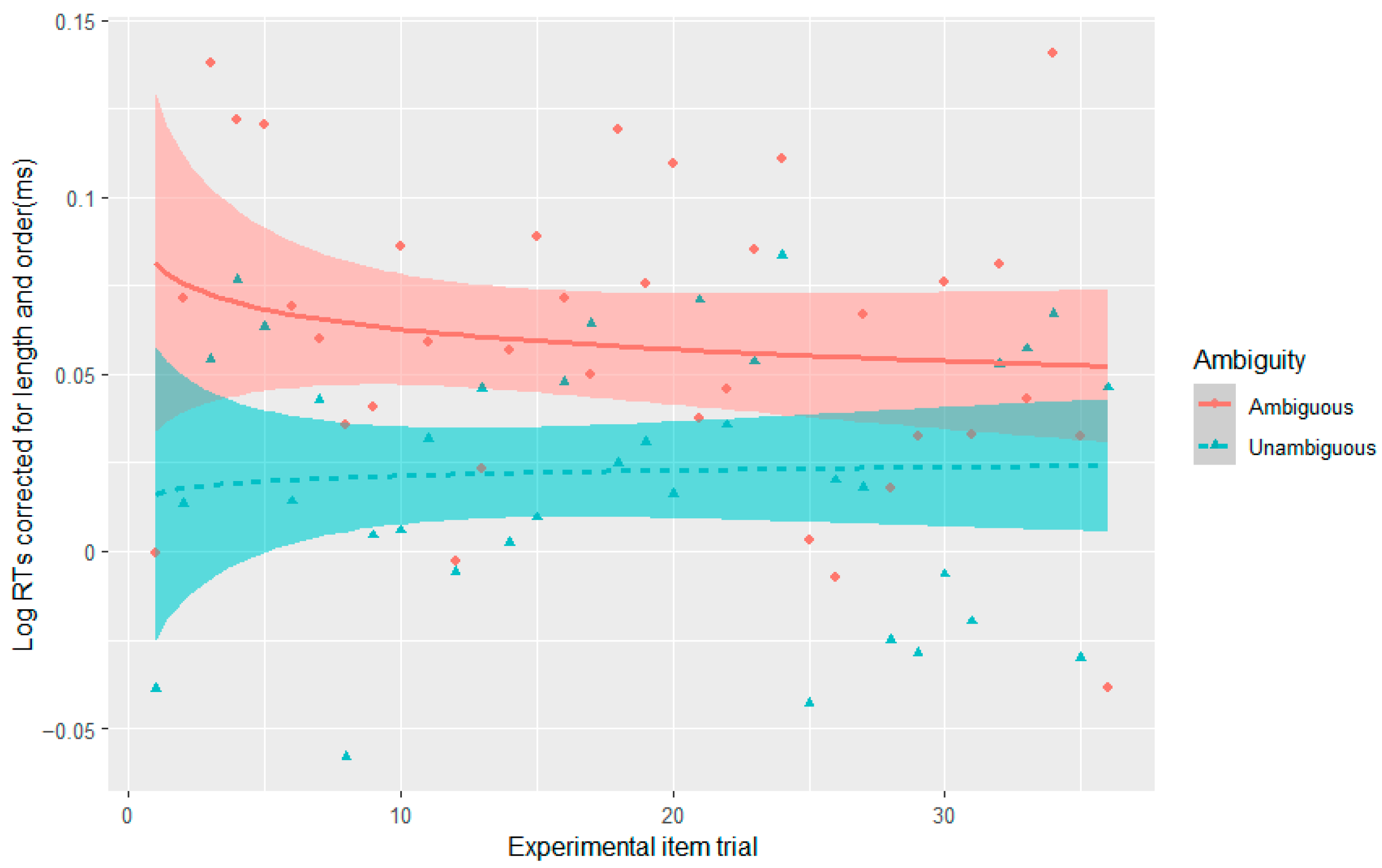

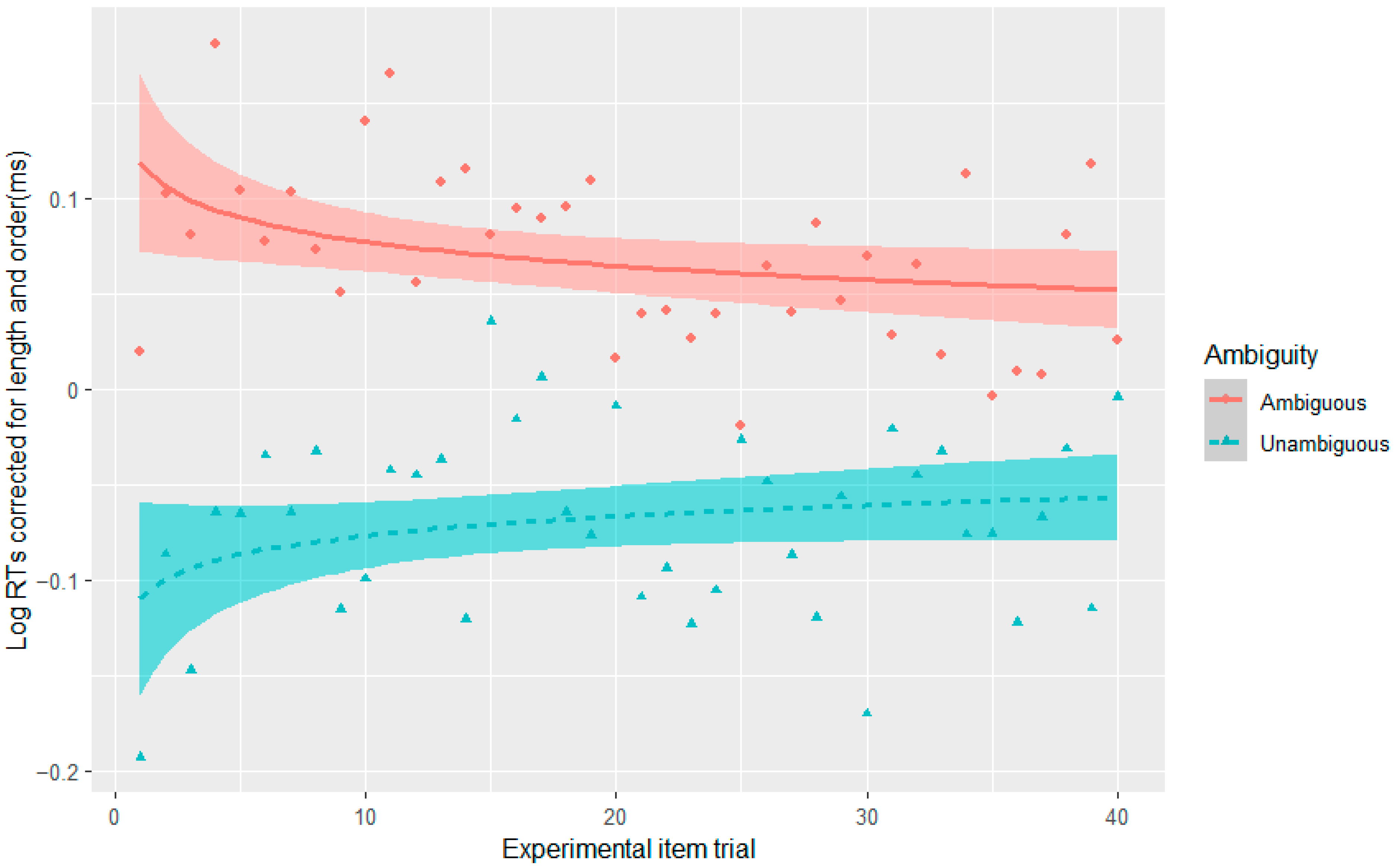

7.2. Syntactic Adaptation

Experiments 1–3 were successful in replicating syntactic adaptation to the RC-MC ambiguity. A novel observation was its appearance under full-sentence reading without any equipment (i.e., for eye-tracking), a more natural condition. This again provides evidence against an account of syntactic adaptation that is based solely on learning the self-paced reading task and its interaction with sentence difficulty (

Prasad and Linzen 2021). Failure to find conflict adaptation or a correlation between the Stroop and ambiguity effects also makes it unlikely that the syntactic adaptation effects are due to reanalysis improving via a domain-general cognitive control mechanism, as outlined by the conflict monitoring theory. At the very least, the evidence from the current experiments is not easily compatible with a higher-level reanalysis mechanism without some domain-specific constraints. Given that syntactic adaptation was localised to the disambiguating region and not observed in comprehension accuracy, the observed syntactic adaptation effects appear most compatible with either the parser changing expectations for the RC parse via probability updating or/and its reanalysis mechanisms improving in efficiency (

Yan and Jaeger 2020).

In Experiment 4, we did not observe syntactic adaptation with the goal-modifier ambiguity in reading times. Given that there is a recurrent reanalysis in Experiment 4, this null result is at odds with a facilitated reanalysis account of the syntactic adaptation in reading times that were observed in Experiments 1–3. An expectation-based account can, however, provide an argument for the absence of syntactic adaptation in reading times in Experiment 4. Unlike Experiments 1–3, in Experiment 4 the ambiguity appeared in all the fillers and was always resolved to the more probable (goal) parse. This resulted in the goal-modifier ambiguity being resolved to a modifier interpretation 50% of the time and the goal interpretation the other 50%. While in Experiments 1–3 the RC-MC ambiguous verb was resolved towards the RC interpretation 100% of the time, other studies (

Fine et al. 2013) have observed syntactic adaptation with the RC-MC ambiguity when the RC parse only occurred 50% of the time. As mentioned in the Introduction, a likely prerequisite for a detectable change in expectation for the less preferred parse is a sufficiently big change in its probability of occurrence in the natural environment to that in the experiment. Based on the verbs from

Fine et al. (

2013), the probability of an RC parse is only 0.008 in nature, such that a 0.5 occurrence in the experiment is a dramatic change (

Fine et al. 2013). While our PP modifier can also be argued to be contained in a (reduced) relative clause, we would need to assume that the frequency of those RCs in nature is closer to 0.5 than those containing verbs that are ambiguous between the past participle/past tense. If so, the probability of a PP modifier interpretation in Experiment 4 may not have sufficiently differed from its occurrence in the natural environment to observe an impact on parsing expectations. In sum, it is possible that syntactic adaptation is not only dependent on the probability that the less preferred parse appears in the experiment but also on how much that probability differs from the natural environment, which has been previously suggested (

Fine and Jaeger 2016). To test this, future work should study whether the goal-modifier ambiguity can demonstrate syntactic adaptation when the proportion of ambiguous goal-modifier PPs that are disambiguated to a modifier PP is increased to 100%, the best-case scenario.

The difference in probability of a parse in nature vs. the experiment has likewise been used to explain why the penalty for the more frequent MC parse in the RC-MC ambiguity is difficult to replicate in syntactic adaptation studies (

Yan and Jaeger 2020). The difference in probability is just much smaller for the MC parse (0.7 vs. 0.5) than it is for the RC parse (0.008 vs. 0.5). This raises a caveat to interpreting our syntactic adaptation effects from Experiments 1–3 as being commensurate with a change in expectation for the two parses. We did not assess adaptation away from the preferred parse (i.e., a penalty to the processing time of the MC interpretation), which would provide the strongest evidence for a change to parsing expectations, a finding that is inconsistently observed in previous work (

Dempsey et al. 2020;

Harrington Stack et al. 2018;

Prasad and Linzen 2021;

Yan and Jaeger 2020).

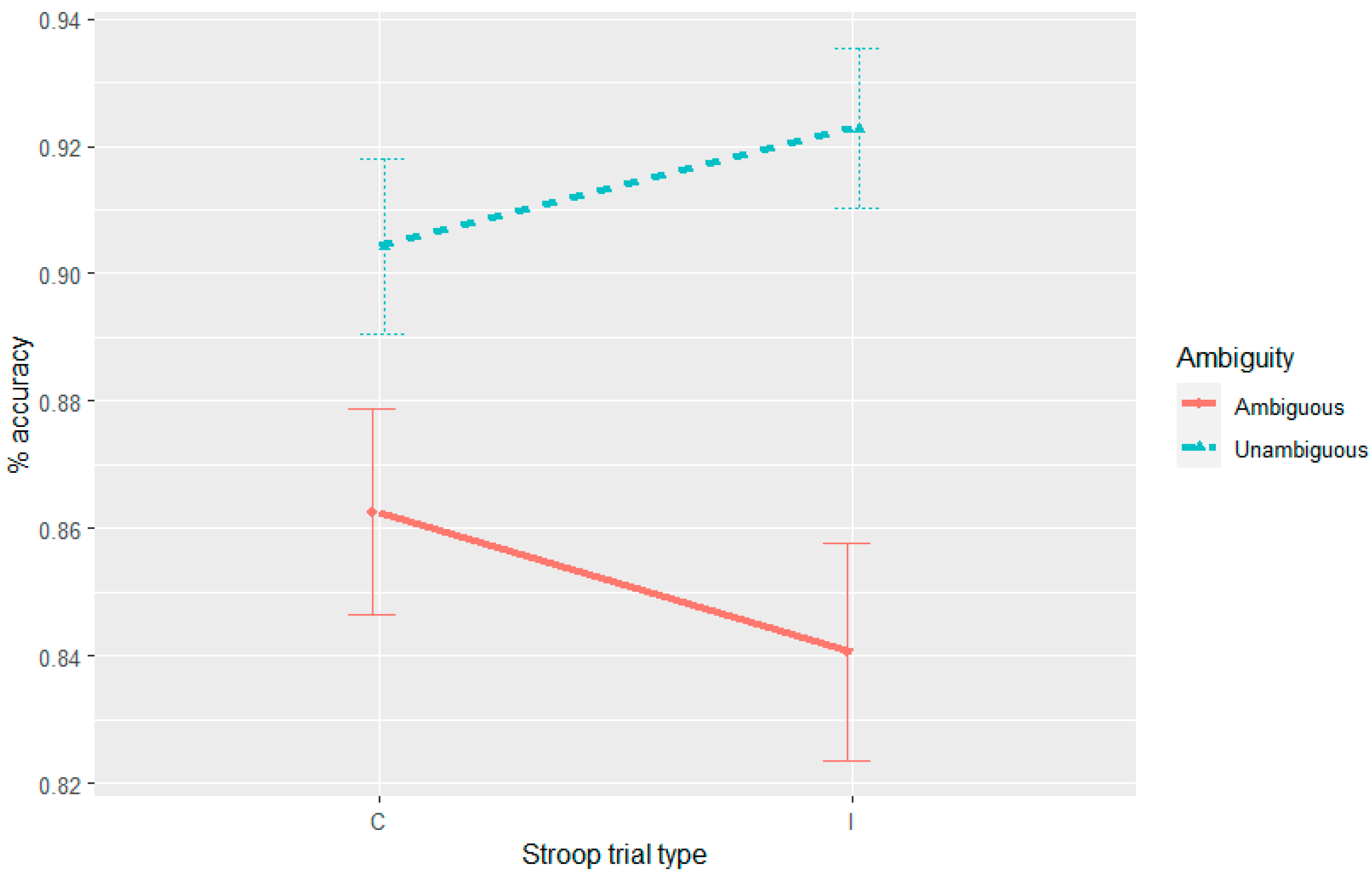

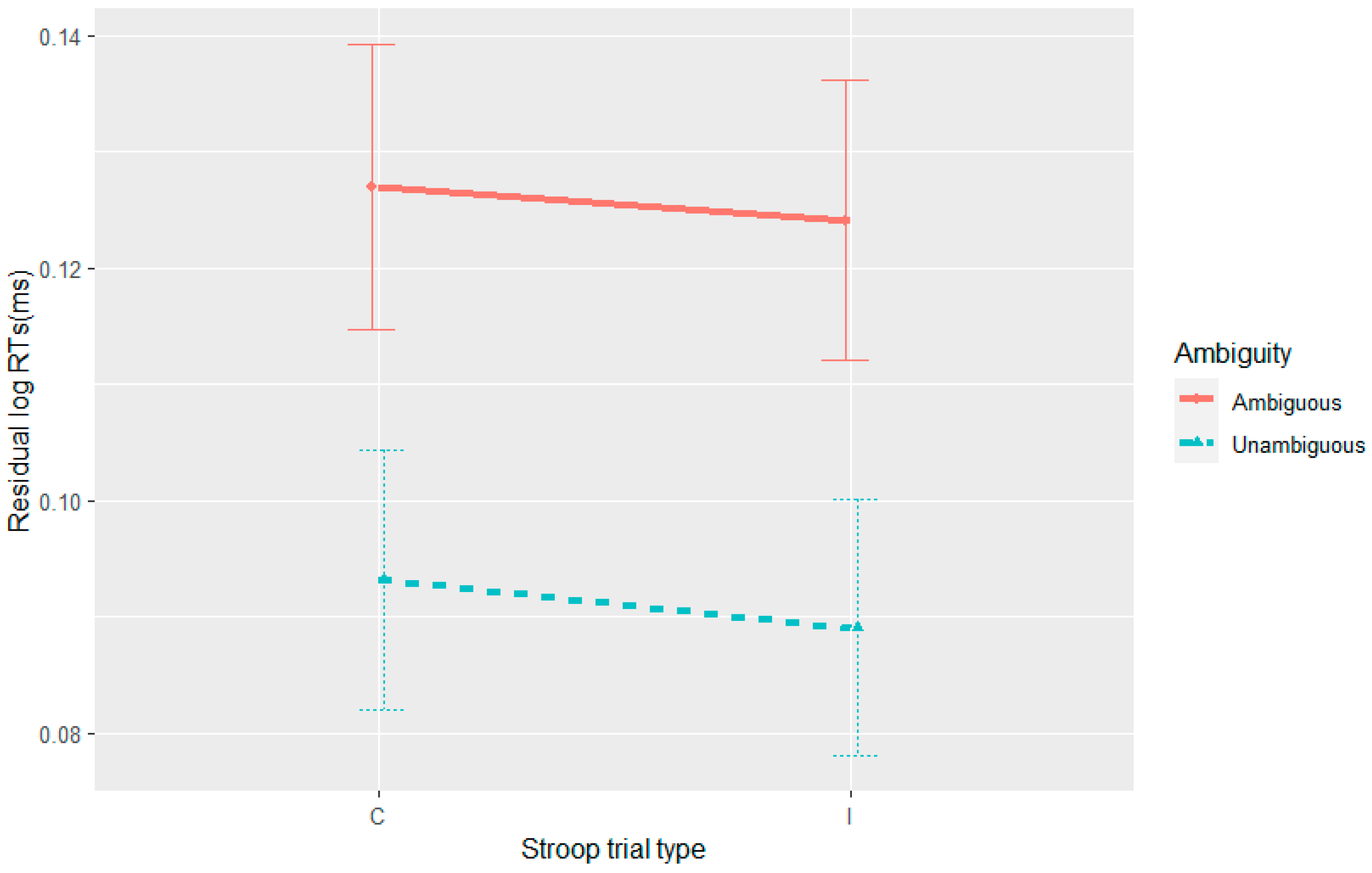

Further complicating the picture is the observation of syntactic adaptation in accuracy in Experiment 4, albeit one that was modulated by the Stroop manipulation where accuracy to the unambiguous sentences progressively decreased on post-incongruent trials. Thus, the nature of this three-way interaction is not consistent with any of the theories outlined here.

While the work here and elsewhere (

Yan and Jaeger 2020) demonstrates syntactic adaptation is not specific to the self-paced reading task, it may be dependent on other aspects of the experimental environment. Other work on syntactic adaptation fails to show transfer effects from a more natural reading of paragraphs to an experimental single-sentence presentation (

Atkinson 2016). Thus, a factor that may facilitate syntactic adaptation is the presentation of sentences in isolation, which may put an attentional emphasis on the syntactic structure. Further work is needed to understand exactly what is required for adaptation to occur and whether or when it can transfer to the wild.