Abstract

To deepen on the study of the concept of neologicity, an exhaustive review of the literature was carried out. Once the different parameters related to this concept were isolated, we realized that some of them were also used to determine the communicative function of neologisms. For this reason, first, we correlated the objective criteria to classify neologisms as prototypical of the denominative or the stylistic function with the parameters related to the neological quality. Second, we defined new criteria, both linguistic and chronological, to broaden the scope of our analysis. Afterwards, all the criteria were applied to a corpus of neologisms from newspaper articles and journalistic blogs in Spanish written by women and men. The results confirmed that neologisms with stylistic features tend to be more neological than denominative neologisms. Consequently, they are usually less frequent lexical units used in general or informal contexts. In addition, they tend to be the result of unproductive word formation rules that might contain subjective linguistic components and also tend to be more recent.

1. Introduction

To answer the question “are stylistic neologisms more neological?”, we must consider that a neologism, which is defined around the concept of novelty (Guerrero Ramos 1995, p. 10; Sablayrolles 2003), does not only respond to an objective novelty, depending on whether the creation is more or less recent, but also to a subjective novelty, in relation to the perception of novelty or neologicity of the speakers (Rey 1976, pp. 12–13).

Regarding the concept of novelty, among the different acceptations of the adjective nuevo -va ‘new’ (Freixa 2010a, p. 8), we highlight the following from the Diccionario de la lengua española (DLE) of the Royal Spanish Academy (Real Academia Española 2014):

1. Newly made or manufactured.2. Perceived or experienced for the first time.3. Distinct or different from what was previously learned.9. Said of a thing: That it is little or hardly deteriorated by use, as opposed to old.

Based on these acceptations, it can be intuited that considering a word as new or neological involves different aspects related to the fact that it may be recent (acceptation 1); that it may be unknown to a certain speaker, although it may not be a newly formed word (acceptation 2); that it does not follow the rules of word formation or it uses a different code (acceptation 3); or that, being a little-used word, even if it may not be recent, it is perceived as such (acceptation 9). Therefore, different parameters are involved in the perception of novelty. Moreover, the neologism quality or neologicity has been defined as a non-discrete but gradual category (Lavale-Ortiz 2019; Estopà 2015, pp. 125, 136; Sánchez Manzanares 2013, p. 120; Antunes 2012, p. 217), according to the precepts of cognitive linguistics (Cuenca and Hilferty 1999; Croft and Cruse 2004; Ibarretxe and Valenzuela 2012).

Thus, we believe that, in general, neologisms with more stylistic features will be considered more neological than those neologisms with a merely referential function. At this point, we consider that “the intention […] guides the communicative activity and decisively influences linguistic choices” (Escandell-Vidal 2014, p. 89). According to this statement, if a stylistic and expressive will exists, the communicative function will not be limited to identifying the referent of a given word but will aim to attract the receiver’s attention, having an impact on the linguistic form of the neologism (Cañete-González and Llopart-Saumell 2021, p. 256; Llopart-Saumell forthcoming) and the context of use (Llopart-Saumell 2021).

Neologisms that, besides having a referential communicative function, are used with a stylistic or expressive function and whose motivation goes beyond designating a certain element of reality usually have a series of features that allow them to be identified. These are features related to discursive factors as well as morphosemantic, pragmatic, and use factors. Additionally, these are often ephemeral units used at a given moment since most of them do not become part of the lexicon of the speakers. Given that their motivation is to stand out and attract the reader’s or listener’s attention, they are usually the result of original and therefore unproductive combinations. For this reason, the receiver, from a cognitive point of view, will have to make a greater effort to properly interpret the meaning of the new word based on the intention of the sender expressed in the statement. Although some of these units may eventually spread through the language, and even if they may go through a period of great propagation among the members of a linguistic community, since there is a subjective will (sometimes due to a trend or a certain event), they will usually fall into disuse.

After a thorough review of the literature devoted to the communicative function of neologisms and, more specifically, to denominative neologisms and stylistic ones, Llopart-Saumell (2016) studies in detail the concepts and general notions underlying this dichotomy. This thorough theoretical analysis provides us with the clues to identify a set of factors closely involved in the study of this dichotomy. Finally, it designs a methodology made up of a set of criteria that should be applied to a corpus of neologisms to identify the prototypical characteristics of these two categories objectively. In fact, an empirical study (Llopart-Saumell 2019) proves that neologisms with prototypical functional, sociolinguistic, and discursive features of stylistic function are usually perceived with greater coincidence among participants (96.5%) than denominative function prototypical neologisms (79.9%)1. Another perception study also shows that in connoted categories (such as informal register, personal nature, subjective opinion, and ideological load), the coincidence among participants is higher than in non-connoted categories (that is, formal register, general nature, objective opinion, and neutral load): 77.42% versus 37.93%, respectively. For this reason, it is safe to say that connoted features are easier to verify than non-marked or neutral features. In this sense, marked or connoted elements can be identified within the neologism itself or in its context of use. To the contrary, non-marked or non-connoted features do not stand out and are, therefore, more difficult to identify with certainty (Llopart-Saumell 2021).

According to this initial hypothesis, the general objective of this work is to correlate the concept of neologicity with the communicative function of neologisms since the literature review points out that they share some of the parameters used to characterize them. For this purpose, first, we relate the criteria used to identify the prototypical neologisms of the denominative and the stylistic function established by Cañete-González and Llopart-Saumell (2021) with the parameters of neologicity isolated in the literature review. Second, we suggest new objective parameters, both linguistic and chronological, to broaden the scope of our analysis. Once the methodological design is defined, all these criteria are applied to a bank of 389 neologisms obtained from texts in Spanish using the lexicographic exclusion criterion (Rey 1976; Observatori de Neologia 2004a). More precisely, it is a corpus of newspapers and journalistic blogs written by women and men. At this point, it is worth mentioning that the works around the study of neologisms based on the social gender variable show that men use more neologisms than women (Cañete-González 2016) and that these new units are also more prototypical of the stylistic function (Cañete-González and Llopart-Saumell 2021). Finally, we analyze whether the neologisms used by men are more neological than those used by women, as well as the role of the textual genre.

2. Theoretical Framework

A neologism is a complex object of study because it is unstable and arguable (Cabré 2015, p. 71). To be precise, a neologism is a lexical unit that is characterized by not being previously recorded in a given language (Rey 1976, p. 17), which implies that novelty is its main feature (Guerrero Ramos 1995, p. 10; Sablayrolles 2003). However, the feeling of novelty depends on the perception of the speaker (Rey 1976). In fact, Rey (1976, pp. 12–13) differentiates objective novelty, in relation to the first documentation, from functional novelty or novelty judgment, in which pragmatic and sociological factors, among others, intervene. Thus, neologicity is related both to objective data, such as first appearance, and to subjective feelings, some of which are also objectifiable and measurable (Freixa 2010b, pp. 28–29).

Hence, the perception of novelty depends on several factors, which can be grouped into chronological (Estopà 2015), temporal (Rey 1976; Lavale-Ortiz 2019), or diachronic (Sánchez Manzanares 2013); use (Vega and Llopart-Saumell 2017); documentation (Vega and Llopart-Saumell 2017); linguistics (Estopà 2015) or morphosemantics; pragmatics (Sablayrolles 2000; Estopà 2015); cognitive (Schmid 2008; Estopà 2015; Hohenhaus 2006; Sanmartín 2016); sociolinguistics (Sablayrolles 2000); and enunciative (Sablayrolles 2000) or discursives (Sablayrolles 2000; Llopart-Saumell 2022).

Regarding the chronological or temporal factor, it considers the moment of appearance of a word. In other words, it is an objective novelty based on the date of first documentation (Rey 1976; Sablayrolles 2000; Estornell 2009; Freixa 2010a; Sánchez Manzanares 2013; Bernal 2015, p. 49; Lavale-Ortiz 2019). In principle, the more recent a unit is, the more neological it is, given that a neologism is a recently created word (Bouzidi 2010, p. 29; Estopà 2015, pp. 142–43). Still, the duration of the neological feeling is variable.

In terms of use, the frequency of use (Bouzidi 2010, pp. 29, 33; Antunes 2012, p. 217) or of occurrence (Freixa 2010a) constitutes an element of reinforcement or erosion of neologicity (Bouzidi 2010, p. 33). Specifically, the frequency of exposure (Schmid 2008, p. 19) that a speaker receives to a word has a certain effect on the cognitive system (Bybee 1985; de Vaan et al. 2007; Knobel et al. 2008). In this sense, a less-used unit will be perceived as more novel because speakers will not be familiar with it. Now, the unit may present a high number of occurrences, but if these occurrences take place during a specific period and then the unit falls into disuse, speakers may perceive it as novel because they do not remember it. On the contrary, the diffusion (Sablayrolles 2000; Vega and Llopart-Saumell 2017) and stability of use (Antunes 2012, p. 217; Estopà 2015) of a word, which are calculated by the number of occurrences and years of documentation (Estopà 2009), respectively, decrease the perception of neologicity.

The documentation or lexicographic parameter is closely related to use since, depending on the success of the lexical unit, it may or may not be included in the dictionary. This process is known as dictionarization (Bouzidi 2010; Bernal et al. 2020a, 2020b; Freixa and Torner 2020). Hence, it is useful to consult different types of dictionaries, text corpora, databases (Estopà 2009; Vega and Llopart-Saumell 2017), and even general lexicographic sources in other languages (Estopà 2015; Freixa 2022). In general, neologisms documented in different works have lost their quality of neologism because they tend to be frequent, stable, and necessary words from a practical point of view. Moreover, if the equivalents of a neologism are already recorded in the main dictionaries of other languages, it also indicates that a denominative need is fulfilled, which is why it is more likely that this lexical unit will become part of the lexical stock of the linguistic community in question, even if it is not currently recorded in the reference dictionaries of a given language.

As for pragmatic aspects, it is important to take into consideration the field of use (Estopà 2015), whether it is general or specialized. For this reason, it is convenient to observe in which discipline or register a word is considered new (Bouzidi 2010, p. 30). On the one hand, if the unit belongs to a general field, it may be more familiar to most speakers. However, if it is part of a professional or specialty field, these units may be used by professionals and specialists in the sector. These types of lexical units are known as receiver neologisms (Guerrero Ramos 2016): they are words perceived as new to the general public (due to a lack of knowledge of the subject matter) but widely used by specialists in the field, and, in some cases, they are the result of a process of determinologization (Bouzidi 2010; Guerrero Ramos 2016; Humbert-Droz 2023). On the other hand, a neologism that is not limited to a specific subject matter may not present a strictly denominative function and could be perceived as more neological if it is used by a very specific social group (young people, for example) or in an informal register. The channel of use, particularly texts from the internet, is also relevant (Estopà 2015). Neologisms circulating through the press and social media show greater propagation, as both platforms constitute a focus for the dissemination of current events (Cañete-González et al. 2019; Iglesias Martín 2017; Maldonado Magnere and Aránguiz 2022). Consequently, these units could be more familiar to speakers and, therefore, less neological.

Linguistic factors present different relevant parameters. First, the language code has an impact on the perception of neologicity (Estopà 2015; Bernal 2015). Loanwords, since they do not belong to the language code, meaning to the internal adequacy criterion (Bernal 2015), are more easily identified as new, recent, or neological units. Certainly, units belonging to a linguistic code different from one’s own are more easily detectable as new words because they are opaquer if the language they come from is not known and they stand out in the text. Therefore, neological feeling is directly related to the process of word formation (Bernal 2015; Sablayrolles 2000). It is observed, for example, that formal resources such as derivation, compounding, and syntagmation go more unnoticed (Bernal 2015; Sablayrolles 2000), whereas loanwords and neologisms formed by blending are easily detectable by participants (Sablayrolles 2000; Díaz Hormigo 2007). In fact, not only the frequency has an impact on perception but also the productivity and frequency of the linguistic elements that form a given complex lexical unit (Estopà 2015; Bernal 2015; Schmid 2008, p. 12): the more productive an affix is, the more difficult it is for a speaker to differentiate new words from existing ones (Bernal 2015).

In turn, Boulanger (2010) pointed out that if the word does not circulate, is infrequent, and is not semantically transparent, even if it is not a recent word, it is perceived as newer (Estopà 2015). In this sense, the predictability and transparency of a word constitute two linguistic features that influence the perception of neologicity (Schmid 2008, p. 13), because they facilitate the possibility of understanding it without having seen or used it before (Estopà 2015). Besides recognizing the components of the lexical unit, it is also necessary to identify the semantic relationship between these components to interpret the unit (Schmid 2008, p. 12). For this purpose, we consider that new words are the result of new combinations of linguistic components already known by speakers because they are part of their language system (Algeo 1980; Aitchison 1994, p. 147). If, from the elements that compose the neologism, the speaker can deduce its basic meaning because the unit is transparent and follows the rules of word formation, the word, even if it is recent or novel, can be understood more quickly (Schmid 2008, p. 13) and, therefore, not be identified as new. On the contrary, if the neologism presents semantic opacity (Schmid 2008; Freixa 2010b; Bernal 2015; Estopà 2015), is a non-productive form, or does not follow the rules of word formation, the speaker will have more difficulty understanding it (Schmid 2008, p. 13) and will identify it more easily as novel. The more familiar the speaker is with the elements that form the word and the way these linguistic elements combine together, the more easily the lexical unit will be decoded and correctly interpreted.

On the other hand, complex, infrequent, and opaque forms challenge the listener because they are humorous or creative and draw the listener’s attention. Although they imply a greater cognitive effort, they are stored or memorized more quickly (Schmid 2008, pp. 15, 25) and cause stronger emotional effects on the receiver, regarding valence and arousal, than neologisms with the same pattern that can be considered non-transgressive since they are the result of productive and predictable word formation rules (Llopart-Saumell forthcoming). In fact, neological feeling has been related to the concept of oddity or strangeness, understood as a transgression or deviation from the rules of word formation (Hohenhaus 2006; Freixa 2010b; Renouf 2013; Bernal 2015, p. 49) to create noticeable, surprising, and unexpected words (Bernal 2015). However, a dividing line cannot be clearly drawn between norms and exploitations because they represent two opposite poles of the same axis rather than two clearly separated categories (Hanks 2013). It is known that word formation rules (WFRs) follow some restrictions conditioning their productivity (Gaeta 2015, p. 859). In this sense, six domain-specific restrictions can be distinguished: phonological, morphological, syntactic, lexical, semantic, and pragmatic (Gaeta 2015). Indeed, words’ oddity is intuitive but not entirely subjective (Freixa 2015).

Cognitive aspects must also be taken into consideration (Schmid 2008) since the referent also has implications when perceiving a word as new. Concretely, if it is a new concept, the conceptualization of that referent might not be completed (Bouzidi 2010, p. 29; Antunes 2012, p. 217; Sanmartín 2016, p. 192). Therefore, this word could be considered more neological because, among the members of the linguistic community, a concept associated with this unit has not yet been formed (Schmid 2008, p. 2).

Regarding sociolinguistic factors, there are different variables that have an impact on the perception of novelty, such as age, education level, social class, profession, place of birth and residence, languages spoken, interests, etc. A speaker’s vocabulary increases as they approach adulthood, meaning that words that a child may consider new are not actually novel, recent, or rarely used, but they do not form part of their mental lexicon (Aitchison 1994). Education also has an impact on vocabulary because, at different educational stages, lexicon is acquired in different subjects, such as geography, economics, literature, mathematics, chemistry, etc. One’s profession also has an impact on vocabulary. Depending on the field (commercial, industrial, educational, etc.), new terms acquired related to work are not shared by non-specialist speakers but by other colleagues in the profession. The geographical area is another factor to be considered due to the diatopic variables used by the inhabitants of a particular territory. The fact of speaking more than one language can also influence the perception of novelty, especially in relation to loanwords or calques from languages we are familiar with. The particular interests of a speaker can also increase the vocabulary on a particular topic, e.g., gardening, soccer, gastronomy, etc.

Finally, the discursive or enunciative context also offers hints about the neologicity of certain units. For a new word, context and cotext2 provide relevant information to understand the meaning of the unit and reduce ambiguity (Schmid 2008, p. 4). In contrast, when a word is used more frequently, ambiguity and context dependency decrease (Schmid 2008).

Therefore, based on the factors defined by several authors to study the perception of the novelty of a new lexical unit, we aim to establish objective criteria to be applied, first, to a corpus of neological units and, second, to relate the communicative function to the neologism quality of a unit.

3. Methodology

3.1. Corpus

Three Spanish newspapers were selected for this study: ABC, El País, and La Vanguardia, from which we extracted articles published by women and men during the last 10 years. A selection was made, on the one hand, of press articles published in digital format in the sections considered most productive from a neological point of view, such as Culture, Sports, Economy, International, and Opinion, and, on the other hand, of blogs published on the web pages of each of the newspapers mentioned above.

Regarding newspapers, the corpus included 220 articles, of which 100 were written by women and 120 by men. The articles belonged to different sections of the newspapers, which were distributed in the following way (see Table 1):

Table 1.

Corpus of journalistic texts.

As for the corpus of journalistic blogs, 139 articles were included: 69 were written by women and 70 by men. In this case, sections were not considered since most blogs were classified by author and not by topic.

After defining the textual corpus, a manual extraction was made to identify the neological units according to the lexicographic criterion, meaning that the candidate was considered a neologism if it was not documented in the exclusion corpora—in this case, the Diccionario de uso del español de América y España ([VOXUSO] VOX 2002) and the Diccionario de la lengua española (DLE). Manual rather than automatic extraction was chosen as it allowed us to detect all types of neologisms without leaving out units undetected by automatic extraction, such as semantic, syntactic, or syntagmatic neologisms.3 A total of 118 units were collected from newspaper articles: 59 were detected in texts written by women and 59 in texts written by men. Furthermore, a total of 271 units were found in newspaper blogs: 148 appeared in texts written by men and 123 in texts written by women.

3.2. Methodology of Analysis

First, a bibliographic review on the concept of neologicity was carried out to identify factors that, according to the literature, have an influence over the perception of novelty in a lexical unit. This review allowed us to identify parameters related to use, such as frequency (number of occurrences), stability (number of years or time periods of documentation), circulation (documentation in different works), and others related to the field of use, such as subject matter (general or specific) and register (informal or formal). All these parameters are also employed to determine the communicative function of a neologism (that is, whether a new word conveys prototypical features of the denominative function or of the stylistic one), which counts with a methodological design made up of five different criteria:

- 1.

- World knowledge criterion: According to the literature, denominative neologisms exhibit a mainly referential function since their aim is to give a name to a new concept of the world around us, while stylistic neologisms have a function that goes beyond the referential one (of an expressive type), because they provide a new perspective or nuance of an already known element and show an affective or subjective reaction. Therefore, consulting encyclopedic or specialized sources guarantees that the units documented in these works belong to the shared knowledge of the world. In order to apply this criterion, we searched for neologisms in two specialized multilingual databases (the Cercaterm of Termcat and the Grand dictionnaire terminologique (GDT) of the Office québécois de la langue française) and an encyclopedic source (the Spanish Wikipedia).

- 2.

- Use criterion: It allows us to observe whether a neologism has been established in the language and whether it has already become part of the lexical stock of a linguistic community, even if it is not registered in the main reference dictionaries of Spanish. To apply this criterion, four sources were taken into account: the OBNEO database (BOBNEO) and three textual corpora—Google Scholar, the Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual (CREA), and the Corpus Diacrónico del Español (CORDE). The appearance of the neologism in two or more sources indicates that the neologism has a medium–high frequency of use. Meanwhile, if it is only documented in one or none of the four sources, we can affirm that the frequency is low or null.

- 3.

- Stability criterion: For this criterion, both the number of occurrences of a neologism and the number of years in which it has been documented are taken into account. Thus, this criterion considers that a neologism can be very frequent in a short period of time because of a trend or current events without stabilizing over time. On the contrary, a neologism may have a low but stable frequency over the years. To calculate this, we used BOBNEO data. On the one hand, we counted the number of years in which the neologism appeared documented in the corpus and, on the other hand, the number of occurrences it presented. Specifically, a unit was considered unstable or ephemeral if it was a hapax (a single occurrence in a single year) or if it presented between 2 and 4 occurrences during 2 or 4 years.

- 4.

- Discursive position criterion: We observe the position of the neologism within the discourse. On the one hand, we evaluate whether it appears in the title or the body of the text, since the title has an appellative function to attract the reader’s attention and encourage them to read the text. On the other hand, we observe whether it appears in an opinion section or a column, since in this section, writers have greater freedom and can adopt their style. If these features are present, it is considered that it has more possibilities of carrying a stylistic function.

- 5.

- Discursive context criterion: For this criterion, we observe whether the context, meaning the sentence in which the neologism is included, contains pseudo-literary language elements (such as an adjective placed before a noun and rhetorical figures), colloquialisms (units marked in the dictionary as colloquial, vulgar, slang, etc.), or sender deixis (texts written in the first person singular or plural and verbs of sentiment). Therefore, we take into account that journalistic texts must present certain characteristics found in the style guides of newspapers; if these rules are transgressed, we understand that the function of the text goes beyond informing or providing new information. In these cases, there is probably a different communicative intention, such as convincing, moving, etc.

As shown in Table 2, a relationship was established between the neologicity parameters detected in the literature review and the criteria established by Cañete-González and Llopart-Saumell (2021) to study the communicative function of neologisms since, as mentioned above, the aim of this work is to establish a possible relationship between the communicative function and the neological quality.

Table 2.

Communicative function of neologisms (Cañete-González and Llopart-Saumell 2021: adapted from Llopart-Saumell 2016) and neologicity parameters.

Out of these criteria, and as Llopart-Saumell (2016) points out, the world knowledge criterion, the use criterion, and the stability criterion indicate that a neologism has a rather denominative prototypical function, while the criteria of discursive position and discursive context show a neologism with a more stylistic prototypical function. In this sense, prototypical neologisms of the denominative function tend to belong to a specific and, consequently, formal field of use and show moderate or high circulation, frequency, and stability of use. Meanwhile, prototypical neologisms of the stylistic function tend to belong to an informal and general field of use and show low circulation, frequency, and stability of use.

After establishing this relationship, it became clear that the linguistic and chronological parameters were not considered among the criteria established to study the communicative function of neologisms (see Table 2); therefore, objective criteria were implemented to complement our analysis (see Table 3 and Table 4). Regarding the linguistic parameters, three criteria were defined: (6) morphosemantic and morphopragmatic aspects criterion, which can be studied systematically and has been related to expressivity (Llopart-Saumell 2016); (7) productivity criterion, related to the creation of units of the same word family; and (8) predictability criterion, related to the transgression of word formation rules.

Table 3.

Linguistic parameter analysis.

Table 4.

Chronological criterion.

For the morphosemantic and morphopragmatic aspects criterion, we took into account those linguistic features closely related to the informal register and the linguistic code (Estopà 2015; Bernal 2015). In particular, we considered the use of intensifying gradational prefixes (such as archi- ‘archi-’, extra- ‘extra-’, hiper- ‘hyper-’, infra- ‘infra-’, semi- ‘semi-’, super- ‘super-’, ultra- ‘ultra-’), affixes with semantic change (such as -ismo ‘-ism’, -ista ‘-ist’, and pseudo- ‘pseudo-’), intensifying combination forms (such as macro- ‘macro-’, mega- ‘mega-’, micro- ‘micro-’, mini- ‘mini-’, -oide ‘-oid’), hybrid forms (combining lexical bases from different languages), value elements (such as units containing vulgar, popular, colloquial, or slang words), and proper names (such as anthroponyms, place names, and others). The productivity criterion considered the existence of lexical units from the same word family as the neologism since neologisms that are the result of frequent combinations of linguistic elements are perceived as more familiar and, consequently, less neological by speakers (Schmid 2008). And last, the criterion of predictability was related to the infringement of the rules of word formation, which are the result of unproductive combinations of linguistic elements (Hohenhaus 2006; Freixa 2010b; Renouf 2013; Bernal 2015). Out of these, the first and last criteria would be more related to the stylistic function and, therefore, more neological, while the second would indicate a tendency towards the denominative features and be less neological.

One last criterion was also established, the temporal criterion (9), where the indicator is the date of first documentation. This date allows us to determine how recent a unit is. To establish a date, we used the Factiva database, which contains a large number of Spanish texts (among other languages) from newspapers since 1994; as we are studying lexicographical neologisms, we believe it will be enough, although some lexical units might be older than that.

The temporal criterion is related to how recent a unit is. For this reason, we can state that recent lexical units can be perceived as more neological. However, according to the literature, the relationship between this feature and the communicative function of neologisms has not been established yet. However, once our analysis is completed, a possible correlation might be found regarding the denominative and stylistic functions of neologisms.

Having established the parameters of analysis, the criteria were applied to the corpus of neologisms of women and men. Finally, an in-depth study of the quality of neologisms was carried out by associating the communicative function identified in the different neologisms with the concept of neologicity to confirm or refute the hypothesis that neologisms with more features of stylistic function also tend to present more features related to the neologism’s quality.

4. Results and Discussion

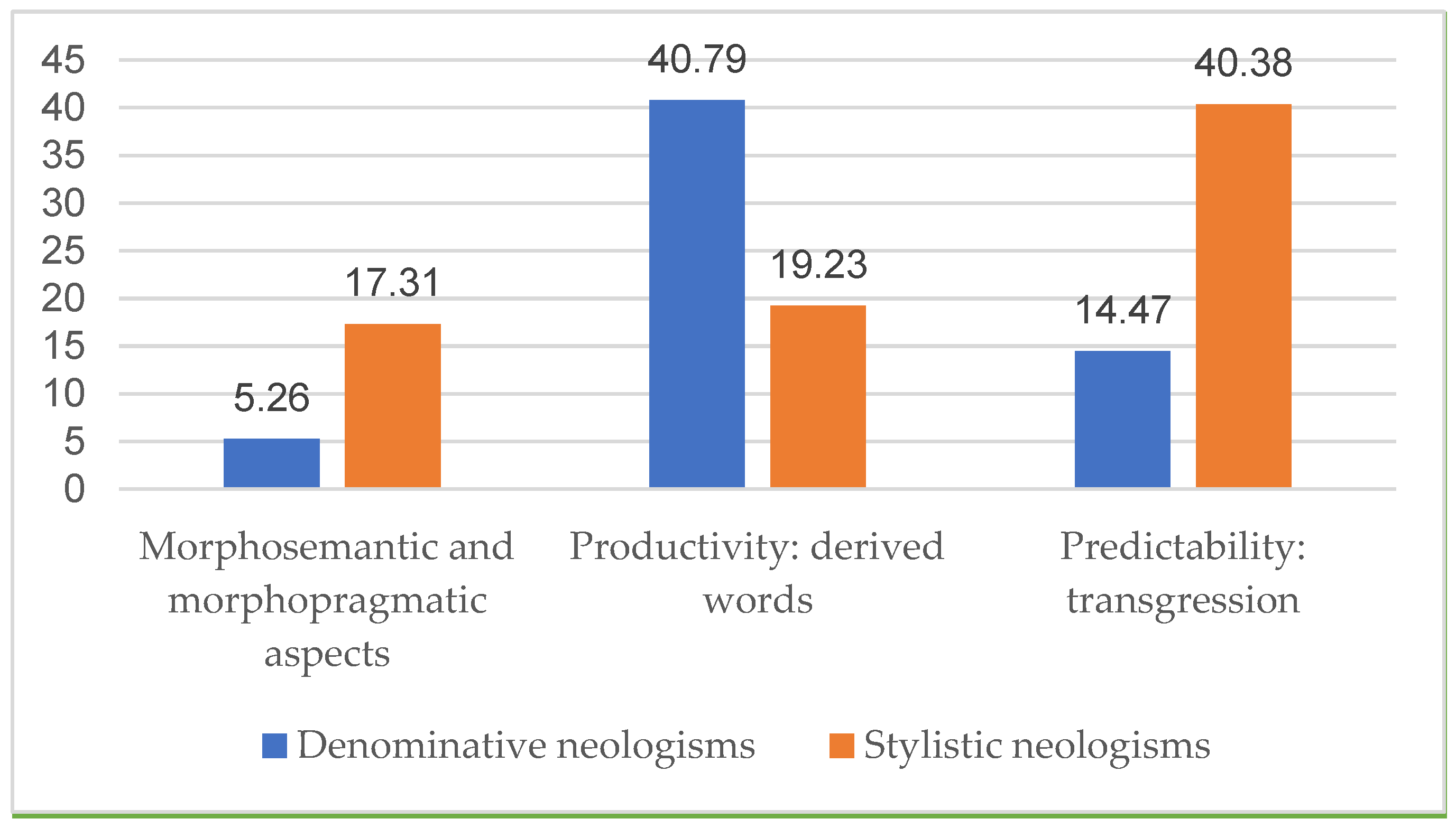

During the first stage of our analysis, all the criteria of the methodological design were applied to the 389 neologisms in the corpus. According to the criteria to study the communicative function of neologisms (Cañete-González and Llopart-Saumell 2021) (see Table 2), 152 neologisms (39.07% of the total) were classified as prototypical of the denominative function and 52 as prototypical of the stylistic function (13.37%). In this sense, the criteria of the communicative function of neologisms enable the identification of units with prototypical features of the denominative and the stylistic functions. However, some neologisms present features that are not prototypical of either function since they do not meet sufficient criteria. Thus, as shown in Figure 1, the selected morphosemantic and morphopragmatic aspects represent a small part of the total number of neologisms; however, the results show that they are more present in stylistic neologisms (17.31%) than in denominative neologisms (5.26%). It would be interesting, in the future, to extract some more linguistic elements in order to deepen this analysis. Conversely, neologisms that have led to the creation of lexical units from the same word family are much more frequent among denominative neologisms (40.79%) than among stylistic neologisms (19.23%). In other words, it is more likely that new derived words are generated when they are related to a neologism with a denominative function, due to its stability, the non-transgression of formation rules, or the specialized nature of the neologism, among other reasons. Finally, the transgression of word formation rules is lower among the prototypically denominative neologisms (14.47%) than among the neologisms considered stylistic (40.38%).

Figure 1.

Linguistic parameters.

Concerning the predictability criterion, that is, the transgression of the rules of word formation, neologisms such as autodeportación ‘self-deportation’, autoindulto ‘self-pardon’, desanular ‘uncancel’, and reanular ‘recancel’ were found. In the first two cases, the combination form auto- ‘self-’ is attached to a lexical base that implies an action performed by a third party and not one that can be done by oneself (deportar ‘to deport’ and indultar ‘to indult’), whereas in the last two cases, the transgression occurs by joining a negation or inverse-action prefix and a repetition prefix to a lexical base that implies an irreversible activity. In addition, the author is aware that he has created a new word and warns the reader, as shown in example 3, in which the writer adds a comment about the use of neologisms in between brackets:

- (1)

- El discurso más radical de Mitt Romney, que abogaba por una “autodeportación” le valió a este la nominación republicana, pero también la espantada del electorado hispano en las presidenciales. (Mitt Romney’s most radical speech, advocating for “autodeportación” ‘self- + deportation’, earned him the Republican nomination, but also the Hispanic electorate’s shock at the presidential election) (ABC, 14 April 2014).

- (2)

- No puedo compartir algunas de esas críticas. La Ley de Amnistía de 1977 no fue un autoindulto o una autoamnistía equiparable a los que en otros países se otorgaron a sí mismos genocidas y dictadores. (I cannot agree with some of these criticisms. The 1977 Amnesty Law was not an autoindulto ‘self- + pardon’ or a self-amnesty comparable to those that genocides and dictators conceded to themselves in other countries) (El País, 6 March 2012).

- (3)

- En el momento de escribir estas líneas Turelló vuelve a amarrar la concejalía (la número 15 de CiU) tras una chapuza judicial notable en la línea de confundir Digo y Diego, pero el PP ha vuelto a recurrir para ver si puede recuperar alguno de los votos nulos que se desanularon y reanularon (compañeros de edición, me sabe mal, pero nuestro sistema judicial me empuja a la neología). (As I write these lines, Turelló has once again taken the city council (number 15 of the CiU) after a significant judicial lapse by confusing Digo and Diego, but the PP tries to see if it can recover some of the invalid votes that desanularon ‘un- + cancelled’ and reanularon ‘re- + cancelled’ (fellow editors, I do not like them, but our judicial system pushes me towards neology)) (La Vanguardia, 27 June 2011).

For the neologisms presented in examples 1–3, we observe that semantic restrictions are transgressed, as occurs with the English verbs ‘unswim’ or ‘unkill’ (Gaeta 2015, p. 871). The resulting neologisms could be considered unacceptable because they deviate from the expected forms of the rules of word formation according to the meaning of the linguistic components and world knowledge (Gaeta 2015). These neologisms were classified as prototypical of the stylistic function since they are both transgressive and ephemeral. In the case of the productivity criterion, which analyzes the existence of lexical units from the same word family, in some cases, we found one word from the same family of the neologism; for example, reanulación ‘recancellation’ (reanular ‘to recancel’). In other cases, up to four or five words were found; for example, mutualizable ‘mutualizable’, desmutualizar ‘demutualize’, desmutualización ‘demutualization’, desmutualizarse ‘self-demutualize’, and mutualizar ‘mutualize’ (mutualización ‘mutualization’); or freakada ‘freakade’, freakear ‘to freak’, freaky ‘freaky’, and freakismo ‘freakism’ (‘freak’). It is important to remember that these words were searched for both on the Google search engine and the BOBNEO database.

In relation to the morphosemantic and morphopragmatic aspects, firstly, the use of intensifying gradational prefixes was observed, since they usually present a valuing intention (Observatori de Neologia 2004b, pp. 110–11) and, therefore, a more expressive and stylistic one, such as extra-, infra-, semi-, super-, or ultra-. However, only the prefixes super- and ultra- contain some examples classified as stylistic, which are superfamoso ‘superfamous’, which contains a subjective value, and ultraoficialista ‘ultraofficial’, which is an infrequent lexical unit:

- (4)

- Para los que tengáis menos de 30 años, o más de treinta y hayáis vivido recluidos en un convento, El guardaespaldas va, más o menos, de una cantante superfamosa –Whitney Houston- a la que empieza a acosar un loco y tiene que contratar a un guardaespaldas –Kevin Costner- para que le proteja las idem y vaya que si lo hace, por delante y por detrás, zis-zas. (For those of you who are under 30, or over 30 and have lived secluded in a convent, The Bodyguard is, more or less, about a superfamosa ‘super- + famous’ singer, Whitney Houston, who is being stalked by a madman and has to hire a bodyguard, Kevin Costner, to protect her, and sure he does, front and back, zis-zas) (El País, 26 February 2011).

- (5)

- Florencio Randazzo, el candidato ultraoficialista que goza de mayor sintonía con Cristina Fernández, a la que «Coqui» le dedicó el triunfó, tampoco dejó escapar el micrófono. «Esperamos que el pueblo de Chaco nos siga acompañando en las elecciones generales», dijo. (Florencio Randazzo, the ultraoficialista ‘ultra- + official’ candidate closest to Cristina Fernández, to whom “Coqui” dedicated his triumph, did not miss the opportunity to say a few words. “We hope that the people of Chaco will continue supporting us in the general elections,” he said) (ABC, 25 May 2015).

Secondly, the use of affixes with pragmatic change such as -ismo ‘-ism’ and -ista ‘-ist’ was observed. In these cases, affixes are attached to bases from common and familiar language (Bernal and Sinner 2013, p. 488), such as in the case of buenista ‘do-gooders’ or chandalismo ‘tracksuit + -ism’:

- (6)

- Ejemplos: descalificar, y es un caso, a la persona de Arcadi Oliveres pretendiendo refutar así sus opiniones, o hacer lo mismo con los jóvenes indignados por ser jóvenes y, además, nacidos con la flor en el culo (perdón); o con los indignados maduros, por ser nostálgicos del 68 (y no haber hecho ninguna revolución), o con los indignados de todas las edades, por ser radicales o soñadores o buenistas (según convenga a cada refutación). (Examples: disqualifying, and it is a case, Arcadi Oliveres, pretending to refute his opinions, or doing the same with the young outraged for being young and, moreover, a lucky motherfucker (sorry); or with the mature indignant ones, for being nostalgic of ‘68 (and not having made any revolution), or with the indignant of all ages, for being radicals or dreamers or buenistas ‘do- + gooders’ (depending on each refutation)) (La Vanguardia, 27 June 2011).

- (7)

- Entonces, los Juegos se pintaban con la imaginación y el atrevimiento de la Fura dels Baus y su inolvidable espectáculo de apertura. Por ellos corría Cobi, la inesperada mascota diseñada por Javier Mariscal, hasta ahora todavía la más rentable para el COI de la historia de los Juegos modernos. De la imaginación y el atrevimiento creativo, al chandalismo ruso de mosaicos de Bosco subcontratados sin coste aparente. Del ansia de futuro del 92, pura juventud, al vértigo diario del sobrevuelo de malas sorpresas. (Then, the Olympics were brightened by the imagination and boldness of Fura dels Baus and their unforgettable opening show. They had Cobi, the unexpected mascot designed by Javier Mariscal, so far still the most profitable for the IOC in the history of the modern Olympic Games. From imagination and creative boldness to Bosco’s Russian mosaic chandalismo ‘tile tracksuits’ subcontracted without apparent cost. From the eagerness for the future of ‘92, complete youth, to the daily vertigo of enduring bad surprises) (ABC, 23 July 2012).

Thirdly, although some intensifying combination forms were identified, such as micro- ‘micro-’, none of the neologisms were classified as stylistic. Regarding the hybrid forms formed by more than one language, in which two different codes are mixed, especially with loans from English, we can find some examples such as orquesta-big band ‘big band orchestra’, an infrequent and original lexical unit:

- (8)

- En todas las piezas, largas y dotadas de unas modélicas y evansianas arquitecturas, la orquesta-big band demostró las razones de su consideración como una de las más competentes en su género. (In all the pieces, long and endowed with exemplary and Evanesian architectures, the orquesta-big band ‘big band + orchestra’ demonstrated the reasons to be considered one of the most competent in its genre.) (La Vanguardia, 21 October 2011).

Finally, valuing elements in the structure and form of neologisms were observed, such as bases considered colloquial, popular, etc. Such is the case of reventar ‘to burst’ in a revientacalderas ‘to go all out’, or vampiro ‘vampire’ in vampiro digital ‘digital vampire’. In addition, neologisms derived from proper names were identified, including anthroponyms, toponyms, registered trademarks and organizations of different kinds, and possible but transgressive forms (Barrera et al. 2002), such as anti-Tinell ‘anti-Tinell’:

- (9)

- El sino de Rafaelillo es la guerra. Hasta anunciándose con Domecq le tocó una prenda… Después de no puntuar con un potable “Telonero”—en el que intercaló pases de mayor abandono con otros más intensos—, salió a revientacalderas en el cuarto: portagayola de susto y tres largas cambiadas. (Rafaelillo’s destiny is war. Even announcing himself with Domecq, he was touched by a garment…. After failing to score with a drinkable “Telonero”—in which he interspersed passes of greater abandon with others that were more intense—he went all out with a bang in the fourth: portagayola de susto and three long exchanged passes) (ABC, 13 September 2012).

- (10)

- Pero Townshend reserva su artillería pesada para Apple, calificada como “un vampiro digital”. Confiesa que, como artista, se siente incómodo con el mundo musical rediseñado por Apple. (But Townshend reserves his heavy artillery for Apple, described as “a vampiro digital ‘digital + vampire’”. He confesses that, as an artist, he feels uncomfortable with the music world redesigned by Apple) (El País, 11 July 2011).

- (11)

- La experiencia del pacto extremeño es importante porque consagra al PP como un partido atrapalotodo, un all catch party capaz de negociar sin dogmatismos con cualquiera que no se sitúe fuera de las reglas de juego. Es el “anti-Tinell”, la ruptura más brusca y extrema del cordón sanitario contra la derecha. (The Extremadura pact experience is important because it consecrates the PP as an all-catch party, an all-catch party capable of negotiating without dogmatism with anyone who is not outside the rules of the game. It is the “anti-Tinell” ‘anti- + Tinell’, the most abrupt and extreme violation of the cordon sanitaire against the right) (ABC, 7 June 2011).

In terms of the temporal or chronological criterion, while the average first documentation of the prototypical neologisms of the denominative function corresponds to the year 1998, among the prototypical neologisms of the stylistic function, the average date is 2005. Thus, while among the denominative neologisms we find ‘archienemigo ‘archenemy’ (1994), ‘dream team’ (1995), propalestino ‘pro-Palestinian’ (1996), chavismo ‘chavism’ (1998), autopublicación ‘self-publishing’ (1999), british ‘Britsh’ (2001), or retuitear ‘retweet’ (2009), among the stylistic ones there are superfamoso ‘superfamous’ (1996), atrapalotodo ‘all-catch’ (1998), hijoputismo ‘motherfuckerism’ (2002), ultraoficialista ‘ultraofficial’ (2004), levantacopas ‘cup lifters’ (2009), tocaballs ‘ball-buster’ (2009), or conversación–trampa ‘conversation-trap’ (2016).

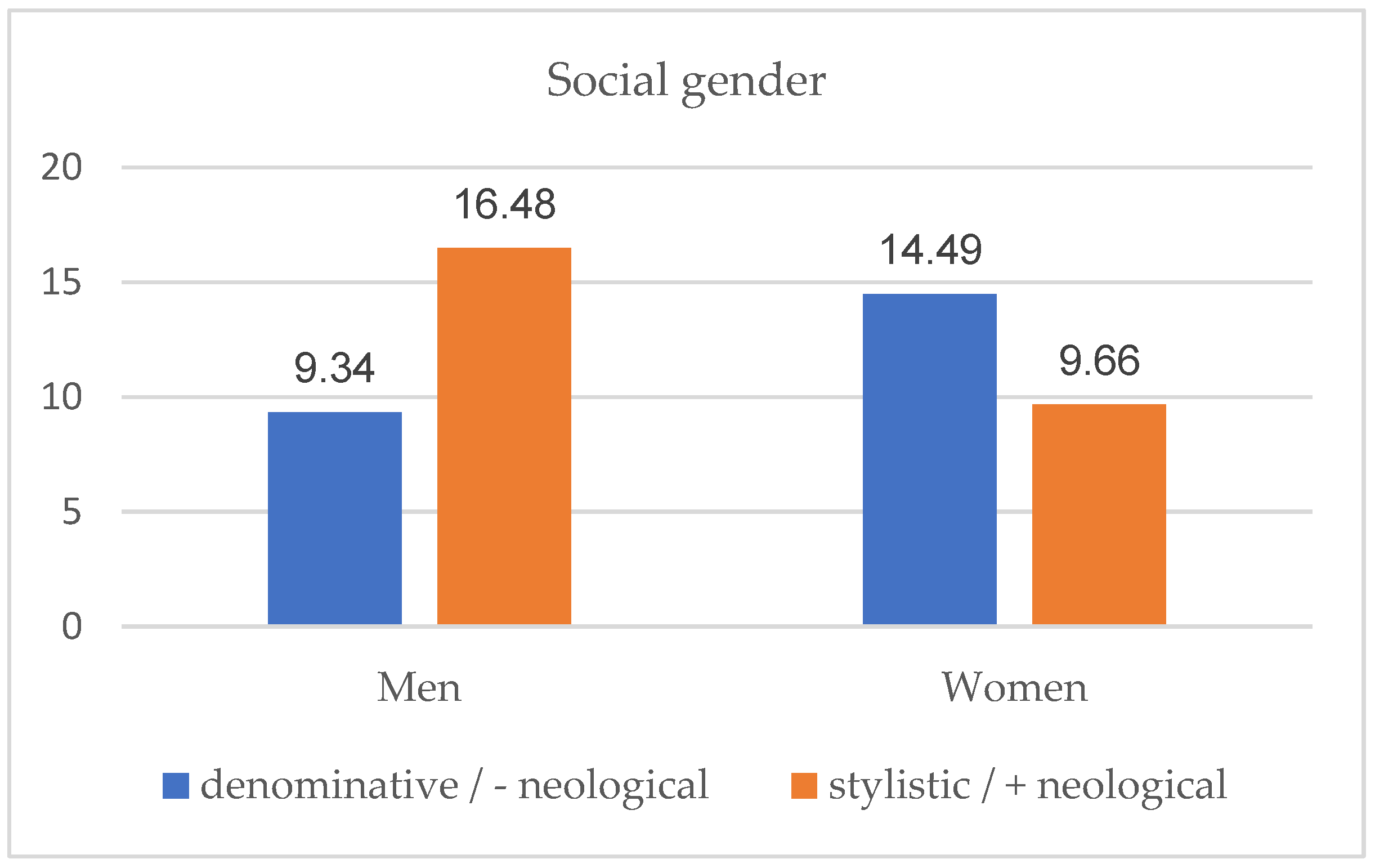

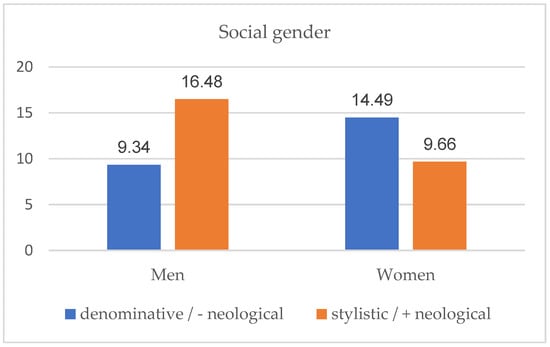

Having established the relationship between the denominative and stylistic functions and the most and least neologisms, the results were analyzed based on social gender. As shown in Figure 2, the percentage of neologisms more prototypical of the stylistic function (and, therefore, more neological) is higher for men, with 30 units, than for women, with 20 units (16.48% versus 9.66%, respectively).4 In contrast, the neologisms used by women seem to be more denominative, with 30 units versus the 17 used by men, and, therefore, less neological (14.49% in the case of women versus 9.34% in the case of men).

Figure 2.

Social gender.

On the one hand, in the case of denominative and less neological neologisms, units such as ciberguerra ‘cyberwar’, gadget ‘gadget’, and recapitalizar ‘recapitalize’ were identified. In the case of stylistic and more neological neologisms, units such as conversación-trampa ‘conversation–trap’, hijoputismo ‘motherfuckerism’, levantacopas ‘cup lifters’, and tocaballs ‘ball-buster’ were detected. Contexts are included in order to understand the meaning.

- (12)

- Tras debatirlo en un momento en el que me levanté de la mesa, a la vuelta me encontré con una conversación-trampa, en la que se inquerían los unos a los otros por sus planes de ampliar la familia, hasta que finalmente anuncié que nosotros sí, que nuestra operación suicida en busca del tercero parecía haber tenido éxito. (After discussing it at a moment when I got up from the table, on my way back I found myself in a conversation-trap, in which they would inquire about each other’s plans to expand the family, until I finally announced that we did, that our suicide operation for the third one seemed to have succeeded) (El País, 1 March 2011).

- (13)

- “Nos conocemos del mundo del espectáculo”, explicó Rubén, un bajista heavy de 26 años, “pero nunca nos habíamos visto en persona”. Rubén también se describió a sí mismo de una forma peculiar: “La gente dice que soy bueno, pero realmente tiendo al hijoputismo”. (“We know each other from the entertainment world”, explained Rubén, a 26-year-old heavy bass player, “but we had never met in person”. Rubén also described himself in a peculiar way: “People say I’m good, but I really have a tendency toward hijoputism.”) (ABC, 9 May 2018.)

- (14)

- Los títulos los suelen ganar las estrellas y eso es precisamente lo que hicieron Lin y Fernandao para crear el tercer gol, el de la sentencia, el que rubricó la temporada perfecta de los levantacopas. (Stars usually win titles, and that is precisely what Lin and Fernandao did to score the third goal, the one that crowned the perfect season for the levantacopas ‘cup + lifters’) (La Vanguardia, 27 June 2011).

- (15)

- Viendo ahora a ese cómico que trata de lanzar un plato de espuma de afeitar al magnate de la prensa, como en una escena de tartas de El Gordo y el Flaco, como la hija de Ruiz Mateos con Mariano Rubio, me acuerdo de Dennis Potter. Porque igual que Rupert Murdoch está por encima de cualquier magnate de la prensa actual, Dennis Potter está por encima de cualquier tocaballs. (Seeing now that comedian who tries to throw a plate with shaving foam at the press magnate, as in a scene of pies from El Gordo y el Flaco, like the daughter of Ruiz Mateos with Mariano Rubio, I remember Dennis Potter. Because just as Rupert Murdoch is above any current media magnate, Dennis Potter is above any tocaballs ‘ball-buster’) (ABC, 20 July 2011).

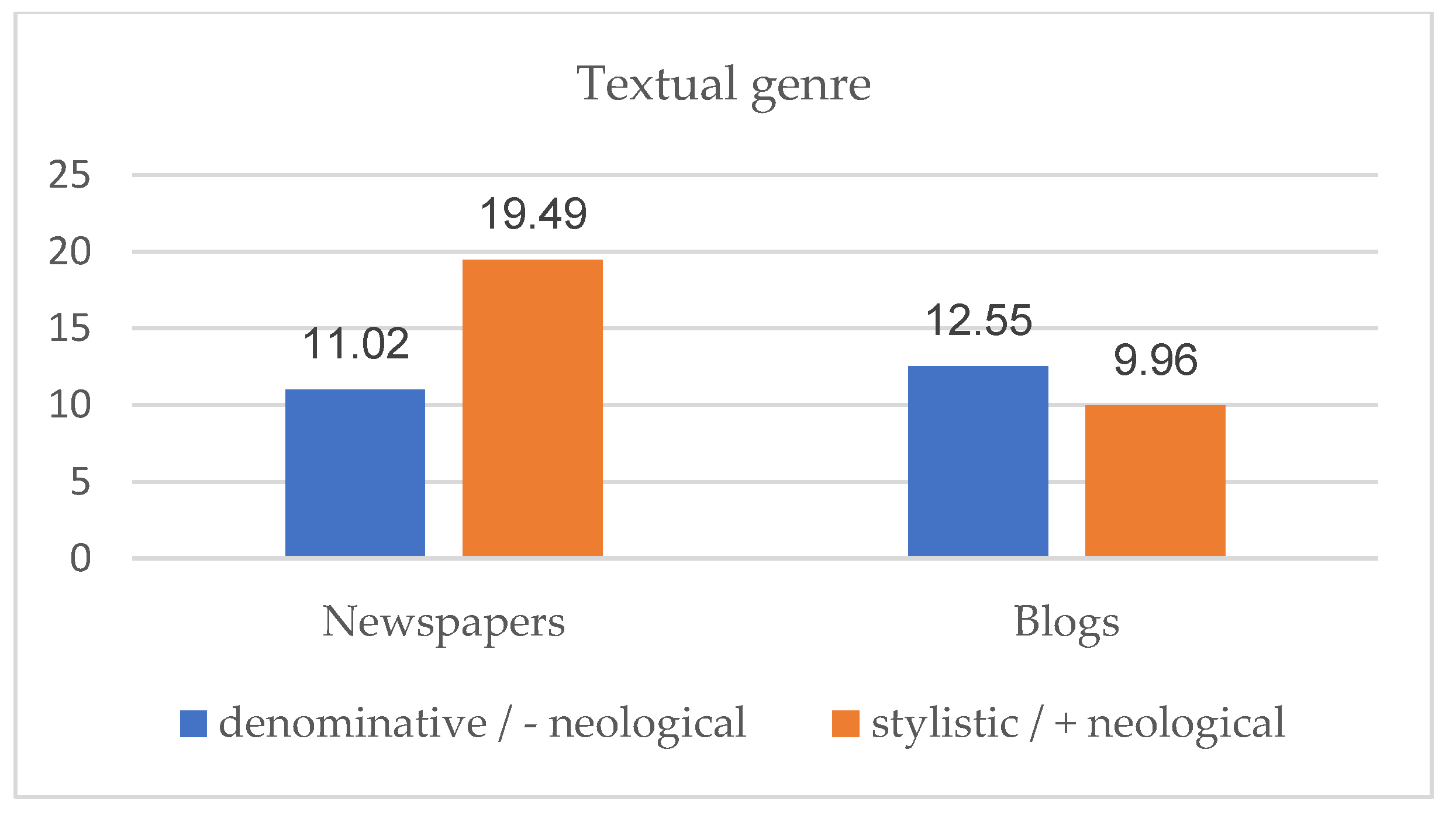

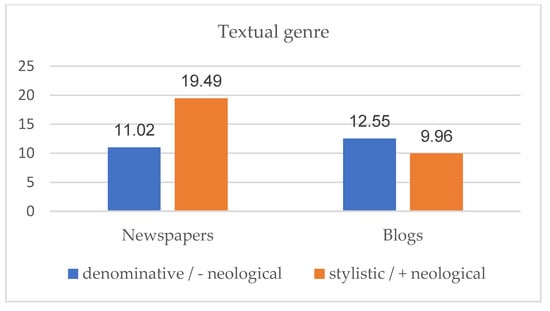

Finally, in the last stage of our analysis, we studied the results obtained in both types of texts: newspapers and blogs. As shown in Figure 3, in newspapers, there seem to be more prototypical neologisms of the stylistic function and with a more neological character (19.49%, that is, 23 units from a total of 118 newspaper neologisms) than denominative neologisms, which are less neological (11.02%, with 13 units). In the case of blogs, the difference between the denominative and the stylistic neologisms is not so noticeable (12.55% versus 9.96%, respectively, that is, 34 and 27 units, respectively, from a total of 227 blog neologisms).

Figure 3.

Textual genre.

In other words, there is not a significant difference between newspapers and blogs in the use of more denominative neologisms, which are less neological (11.02% in newspapers and 12.55% in blogs). However, the difference is more pronounced in relation to stylistic neologisms, which are more neological (19.49% in newspapers and 9.96% in blogs).

It is important to mention that these results are surprising because they contradict the initial hypothesis that the neological units used in blogs were expected to be more stylistic and more neological than those used in newspapers. This supposition was made due to the characteristics of blogs and their resemblance to opinion columns rather than newspaper articles, in which comments and personal analysis on a topic are made in a subjective manner. The greater freedom that blogs offer authors suggested that neological behavior would be different in both types of texts and that blogs would contain a greater number of neologisms as well as more innovative and transgressive units. However, the results revealed the opposite, with a greater number (approximately twice as many) of stylistic neologisms in newspapers.

5. Conclusions

The study of the factors that have an impact on the neological quality and the concept of neologicity and their relationship with the communicative function of neologisms allows us to conclude that, among the lexicographic neologisms classified as the most neological, there are units with a prototypically stylistic function. On the one hand, it seems that the units that are easier to identify as neological share a series of use traits with stylistic neologisms, such as pragmatic, linguistic, cognitive, and discursive features. For example, both tend to show low frequency, are not very stable, present original and not very productive forms, refer to non-institutionalized concepts, and are used in diverse contexts, with the highlighted ones being the most prominent. Moreover, stylistic neologisms might attract the speaker’s attention because they present specific morphosemantic and morphopragmatic aspects, both in the structure and form of the neologism and in the context and cotext.

On the other hand, denominative neologisms, since they respond to a practical need (which is to identify a certain referent), tend to present a predictable and productive form, so that they can go unnoticed by speakers, even if they are recent. They also tend to stabilize over time, causing speakers to become familiar with such neologisms earlier than with stylistic ones. They are also more likely to create other lexical units from the same word family as a result of this circulation, since “each time a word is heard and produced it leaves a slight trace in the lexicon, it increases in lexical strength” (Bybee 1985, p. 117). Indeed, the communicative intention behind a neologism has an impact on the features that determine its novelty.

Regarding social gender, the results show that men use more stylistic and neological units than women. In the 1990s, Labov (1994) and Chambers (2009) pointed out that, from the point of view of language, women tend to be more conservative and use more standard forms than men, which suggests that men are more innovative than women. Therefore, men’s more playful, expressive, and transgressive behavior may be due to their greater sense of freedom in relation to rules, since they seem to be less afraid of breaking the status quo and tend to play more with language through different resources. Thus, it is confirmed that there are differences in lexical innovation between women and men since, besides women using fewer neologisms than men and their units being less neological, the function of the neological units of both genders is also different. Finally, and in relation to textual genre, as mentioned above, the fact that more stylistic neologisms were found in newspapers than in blogs contradicts previous findings (Cañete-González 2016), in which a greater number of neologisms and innovative and transgressive units had been detected in blogs, probably due to the greater sense of freedom that authors experience with this type of text.

In the future, it would be interesting to empirically confirm, through a perception study, whether or not stylistic neologisms stand out among the neologisms identified by speakers. Moreover, it would be convenient to study in more depth the perception of neology to delimit the notion of neologism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L.-S. and P.C.-G.; methodology, E.L.-S. and P.C.-G.; resources, E.L.-S. and P.C.-G.; data curation, E.L.-S. and P.C.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L.-S. and P.C.-G.; writing—review and editing, E.L.-S. and P.C.-G.; visualization, E.L.-S. and P.C.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is part of the research project “LEXICAL, Neología y diccionario: análisis para la actualización lexicográfica del español” (ref. PID2020-118954RB-I00), funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and the Spanish State Research Agency. The translation of this paper has been funded by the Institut de Lingüística Aplicada (IULA) from Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed here comes from Cercador BOBNEO, available online at http://bobneo.upf.edu/inicio.html (accessed on 1 March 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | It must be borne in mind that the minimal and random percentage of probability of coincidence among participants is 50%, since the classification just consists of two categories. |

| 2 | Regarding these terms, according to the terminology used in discourse analysis and pragmatics, cotext refers to the verbal context, while context includes the discursive context, which comprises extralinguistic factors (Cortés and Camacho 2003, pp. 88–89). |

| 3 | Such as elefante ‘elephant’, seco ‘dry’, and memoria histórica ‘historical memory’. |

| 4 | The stylistic neologisms used by men are: all catch party, antioccidentalismo, anti-Tinell, antitotalitario, atrapalotodo, Bilardista, calle-montaña rusa, ciudad-mito, desanular, días-semanas, evansiano, festa junina, heterocrítica, hijoputismo, ítalo-helvético, levantacopas, megápolis, metagénero, neotrompetista, orquesta-big band, orteguismo, posturismo, reanular, saltino, straw poll, supersonido, vampiro digital, zarzuelístico. Those used by women are: académico-científico, anticatalán, auto-amor, autorrecordarse, ciberunidad, conversación-trampa, fake market, highlining, jruschovka, pistera, profident, señal-pitido, servicio-red, soft, superfamoso, tocaballs, ultraoficialista. |

References

- Aitchison, Jean. 1994. Words in the Mind. An Introduction to the Mental Lexicon. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Algeo, John. 1980. Where Do All the New Words Come from? American Speech 55: 264–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, Mafalda. 2012. Neologia da Imprensa do Português. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade da Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, Mariona, Marc Colell, and Judit Freixa. 2002. La formació de neologismes a partir de noms propis. In Lèxic i Neologia. Edited by M. Teresa Cabré, Judit Freixa and Elisabet Solé. Barcelona: Observatori de Neologia, Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, pp. 265–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, Elisenda. 2015. Ser o no ser: Els neologismes i la percepció dels parlants, entre la normalitat i la raresa. In Norma, ús i Actituds Lingüístiques. El Paper del Català en la Vida Quotidiana. Edited by Carsten Sinner and Katharina Wieland. Leipzig: Leipziger Universitätsverlag, pp. 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, Elisenda, and Carsten Sinner. 2013. Neología expresiva: La formación de palabras en Mafalda. In Actas del XXVI Congreso Internacional de Lingüística y Filología Románica. Edited by Emili Casanova Herrero and Cesáreo Calvo Rigual. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 479–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, Elisenda, Judit Freixa, and Sergi Torner. 2020a. Criterios para la diccionarización de neologismos: De la teoría a la práctica. Signos 53: 592–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, Elisenda, Judit Freixa, and Sergi Torner. 2020b. Néologicité et dictionnarisabilité. Deux conditions inverses? Neologica 14: 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger, Jean Claude. 2010. Sur l’existence des concepts de néologie et de néologisme. Propos sur un paradoxe lexical et historique. In Actes del I Congrés Internacional de Neologia de les Llengües Romàniques. Edited by M. Teresa Cabré, Ona Domènech, Rosa Estopà, Judit Freixa and Mercè Lorente. Barcelona: Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, pp. 31–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzidi, Boubakeur. 2010. Néologicité et temporalité dans le processus néologique. Algérie 9: 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan. 1985. Morphology: A Study in the Relation between Meaning and Form. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Cabré, M. Teresa. 2015. Bases para una teoría de los neologismos léxicos: Primeras reflexiones. In Neologia das Línguas Românicas. Edited by Ieda M. Alves and Eliane Simões Pereira. Sao Paulo: Humanitas, CAPES, pp. 70–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cañete-González, Paola. 2016. Innovación Léxica y Género en Textos Periodísticos del Español Actual. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain. Available online: https://www.tesisenred.net/handle/10803/392898 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Cañete-González, Paola, and Elisabet Llopart-Saumell. 2021. Las innovaciones léxicas de mujeres y hombres en la prensa española: Divergencias en la motivación de uso. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación 85: 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañete-González, Paola, Sabela Fernández-Silva, and Belén Villena. 2019. Estudio de los neologismos terminológicos difundidos en el diario ‘El País’ y su inclusión en el diccionario. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación 80: 135–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J. K. Jack. 2009. Sociolinguistic Theory, revised ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, Luis, and M. Matilde Camacho. 2003. ¿Qué es el Análisis del Discurso? Barcelona: EUB. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William, and D. Alan Cruse. 2004. Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, M. Josep, and Joseph Hilferty. 1999. Introducción a la Lingüística Cognitiva. Barcelona: Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- de Vaan, Laura, Robert Schreuder, and Harald Baayen. 2007. Regular morphologically complex neologisms leave detectable traces in the mental lexiconpril. The Mental Lexicon 2: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Hormigo, M. Tadea. 2007. Aproximación lingüística a la neología léxica. In Morfología: Investigación, Docencia, Aplicaciones: Actas del II Encuentro de Morfología. Edited by José Carlos Martín Camacho and M. Isabel Rodríguez Ponce. Extremadura: Universidad de Extremadura, pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Escandell-Vidal, María Victoria. 2014. La Comunicación: Lengua, Cognición y Sociedad. Madrid: Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Estopà, Rosa. 2009. Neologismes i filtres de neologicitat. In Les Paraules Noves: Criteris per Detectar i Mesurar els Neologismes. Edited by M. Teresa Cabré and Rosa Estopà. Vic: Eumo, pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Estopà, Rosa. 2015. Sobre neologismos y neologicidad: Reflexiones teóricas con repercusiones metodológicas. In Neologia das Línguas Românicas. Edited by Ieda M. Alves and Eliane Simões Pereira. São Paulo: Humanitas, CAPES, pp. 111–50. [Google Scholar]

- Estornell, María. 2009. Neologismos en la Prensa. Criterios Para Reconocer y Caracterizar las Unidades Neológicas. València: Universitat de València. [Google Scholar]

- Freixa, Judit. 2010a. La neologicidad en las unidades formadas por prefijación. Puente 12: 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Freixa, Judit. 2010b. Paraules amb rareses. Terminàlia 1: 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Freixa, Judit. 2015. La neologia en societat: «verba sequuntur». Caplletra 59: 186–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixa, Judit. 2022. Garbell: L’avaluador automàtic de neologismes catalans. Terminàlia 26: 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freixa, Judit, and Sergi Torner. 2020. Beyond frequency: On the dictionarization of new words in Spanish. Dictionaries 41: 131–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeta, Livio. 2015. Restrictions in word-formation. In Word-Formation. An International Handbook of the Languages of Europe. Edited by Peter O. Müller, Ingeborg Ohnheiser, Susan Olsen and Franz Rainer. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, vol. 2, pp. 859–75. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero Ramos, Gloria. 1995. Neologismos en el Español Actual. Madrid: Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero Ramos, Gloria. 2016. Nuevas orientaciones en la percepción de los neologismos: Neologismos de emisor y neologismos de receptor o neologismos de receptor. In La Neología en las Lenguas Románicas: Recursos, Estrategias y Nuevas Orientaciones. Edited by Joaquín García Palacios, Goedele de Sterck, Daniel Linder, Nava Maroto, Miguel Sánchez Ibáñez and Jesús Torres del Rey. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hanks, Patrick. 2013. Lexical Analysis: Norms and Exploitations. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hohenhaus, Peter. 2006. “Bouncebackability”: A web-as-corpous-based study of a new formation. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 3: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Humbert-Droz, Julie. 2023. When Terms Become Neologisms: A Contribution to the Study of Neology from the Perspective of Determinologisation. CLINA, Revista Interdisciplinaria de Traducción Interpretación y Comunicación Intercultural 9: 135–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarretxe, Iraide, and Javier Valenzuela. 2012. La Lingüística Cognitiva. Barcelona: Anthropos. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias Martín, Alberto José. 2017. Léxico e Internet: Perspectivas Sobre la Adopción y Difusión de Neologismos y Modas Lingüísticas por Medio de Internet. Bachelor’s thesis, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain. Available online: https://gredos.usal.es/bitstream/handle/10366/136264/TG_IglesiasMartínA_Léxicoeinternet.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Knobel, Mark, Matthew Finkbeiner, and Alfonso Caramazza. 2008. The many places of frequency: Evidence for a novel locus of the lexical frequency effect in word production. Cognitive Neuropsychology 25: 256–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, William. 1994. Principles of Linguistic Change. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lavale-Ortiz, Ruth M. 2019. Bases para la fundamentación teórica de la neología y el neologismo: La memoria, la atención y la categorización. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a la Comunicación 80: 201–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopart-Saumell, Elisabet. 2016. La Funció dels Neologismes: Revisió de la Dicotomia Neologisme Denominatiu i Neologisme Estilístic. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, España. Available online: http://tesisenred.net/handle/10803/398142 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Llopart-Saumell, Elisabet. 2019. Los neologismos desde una perspectiva funcional: Correlación entre percepción y datos empíricos. Signos 52: 665–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopart-Saumell, Elisabet. 2021. The perception of connotations in lexical innovations. In Approaches to New Trends in Research on Catalan Studies. Edited by Antonio Cortijo Ocaña and Jordi M. Antolí Martínez. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 157–82. [Google Scholar]

- Llopart-Saumell, Elisabet. 2022. La percepción de la neología. In La Neología del Español: Del uso al Diccionario. Edited by Elisenda Bernal, Juidit Freixa and Sergi Torner. Madrid: Iberoamericana Vervuert, pp. 105–28. [Google Scholar]

- Llopart-Saumell, Elisabet. Forthcoming. «Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist»: On the emotional effects of word-formation. In Current Perspectives on Spanish Lexical Development. Edited by Irene Checa-García and Laura Marqués-Pascual. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Maldonado Magnere, Carolina, and Vicente Martínez Aránguiz. 2022. “Este tema es buenardo”: Influencia del live streaming en la variación léxica y creación de neologismos sobre expresiones de admiración en hablantes de 16 a 34 años en Santiago de Chile. Tonos Digital: Revista de Estudios Filológicos 42: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Observatori de Neologia. 2004a. Metodologia de Treball en Neologia: Criteris, Materials i Processos (Papers de l’IULA. Sèrie Monografies). Barcelona: Institut Universitari de Lingüística Aplicada, Universitat Pompeu Fabra. [Google Scholar]

- Observatori de Neologia. 2004b. Llengua Catalana i Neologia. Barcelona: Meteora. [Google Scholar]

- Real Academia Española. 2014. Diccionario de la Lengua Española, 23rd ed. Madrid: Real Academia Española, Espasa. Available online: http://dle.rae.es/ (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Renouf, Antoniette. 2013. A finer definition of neology in English: The life-cycle of a word. In Corpus Perspectives on Patterns of Lexis. Edited by Hilde Hasselgård, Jarle Ebeling and Signe Oksefjell Ebeling. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 177–207. [Google Scholar]

- Rey, Alain. 1976. Neologisme: Un pseudo-concept? Cahiers de Lexicologie 28: 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sablayrolles, Jean-François. 2000. La Néologie en Français Contemporain: Examen du Concept et Analyse de Productions Néologiques Récentes. Paris: Honoré Champion. [Google Scholar]

- Sablayrolles, Jean-François. 2003. L’innovation Lexicale. París: Honoré Champion. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Manzanares, M. Carmen. 2013. Valor neológico y criterios lexicográficos para la sanción y censura de neologismos en el diccionario general. Sintagma 25: 111–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín, Júlia. 2016. Sobre neología y contextos de uso: Análisis pragmalingüístico de lo ecológico y de lo sostenible en normativas y páginas web de promoción turística. Ibérica 31: 175–98. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, Hans-Jörg. 2008. New words in the mind: Concept-formation and entrenchment of neologisms. Anglia 126: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, Erika, and Elisabet Llopart-Saumell. 2017. Delimitación de los conceptos de novedad y neologicidad. Rilce. Revista de Filología Hispánica 33: 1416–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [VOXUSO] VOX. 2002. Diccionario de Uso del Español de América y de España. Barcelona: SPES Editorial. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).