Abstract

This paper explores a pedagogy for language revitalization in the specific endangered language context of the Miyakoan language in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. The topic discussed on language revitalization in this paper is a matter of language teaching and learning methodology. The transmission of Miyakoan to the younger generation will be sought in the school domain. There are three guiding research questions: (1) what pedagogy might suit language revitalization, (2) how the school can accommodate this educational goal, and (3) will this educational plan raise pupils’ awareness to learn about the Miyakoan language. First, this paper will review the current direction of Indigenous languages in Japan at the macro socio-historical level. Second, the micro-educational practice will be reported and analyzed. From this micro-educational practice, the role of the school in the community is indicated to become a domain for language revitalization to raise the pupils’ awareness of the local endangered language. The findings also suggest an approach forging the ‘mainstream’ education and pedagogy for language revitalization. Since language transmission is only partially conducted at home in Miyakojima in the 21st century, heritage language education in schools will be essential for revitalizing the language and cosmology of Miyakojima.

1. Introduction

In the familiar modernist trope, Japan is remarkable as a “monolingual” and “monocultural” nation. However, the truth is, for many years, Japan has been multilingual and multicultural (Fujita-Round and Maher 2017; Gottlieb 2005; Maher and Macdonald 1995; Maher and Yashiro 1995; Sugimoto 2003; Yamamoto 2001). The most significant number of native speakers is Japanese, comprising distinct regional dialects and the thousands of Japanese speakers outside Japan in the former imperial colonies of Taiwan and Korea and the north and south of American continents living in the colonial communities of Nikkei (Japanese descendants). Apart from Japanese, there are minority languages: Japanese indigenous languages, such as Ainu and Ryukyuan languages; old immigrant languages, such as Korean and Chinese; relatively newer immigrant languages, such as Portuguese and Spanish, brought by foreign workers and immigrants; and also, Japanese sign language (Fujita-Round and Maher 2017).

1.1. Miyakoan as an Endangered Language

Japanese indigenous languages, as mentioned above, are currently in the process of disappearing from everyday life in the 21st century. Indigenous languages have been replaced interchangeably as “endangered languages” since UNESCO highlighted the urgency of preserving and documenting those minority and indigenous languages in UNESCO (2003) and the Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger by UNESCO (2009). There were eight endangered languages nominated and mapped in Japan: Ainu (Hokkaido), Hachijo (Tokyo), Amami (Kagoshima prefecture), Kunigami, Okinawa, Miyako, Yaeyama, and Yonaguni (Okinawa Prefecture). Among these eight endangered languages, six languages are from the Ryukyu Islands.

This paper focuses on the language revitalization of the Miyakoan language, one of the indigenous and Ryukyuan languages. In the UNESCO atlas, Miyakoan is recognized as “definitely endangered”. In its scale, “definitely endangered” means “children no longer learn the language as mother tongue in the home” (Austin and Sallabank 2011, p. 3). Contextualizing this definition in the case of Miyakoan, based on my fieldwork research from 2012, I would like to draw attention to the reality that (a) children in Miyakojima city (henceforth, Miyakojima) do not speak Miyakoan in the home domain anymore, (b) Japanese is likely to be dominant in the school domain and used as their mother tongue, (c) their family (parents and grandparents) and elderly people in the community may be using Miyakoan among themselves.

Thus, considering the endangerment context of the Miyakoan language transmission in the home domain, there is not likely to be an active intergenerational transmission. The receptive bilingual language use at home perhaps remains, and some children could be exposed to hearing the vernacular interaction between their parents and grandparents occasionally. Or there is a possibility of cases if the child could be babysat by grandparents, who are fluent bilingual speakers, telling the old stories in Miyakoan. Nevertheless, this type of family language transmission between grandparents and grandchildren was the norm in the past.

Language transmission at home aligns with the language development of human beings. De Houwer (2021) defines bilingual language development in three phases: (1) infancy: infants until about 2 years old, (2) toddlers and preschoolers: early childhood until about six years old, and (3) schoolchildren: middle childhood to about 11 years old (De Houwer 2021, p. 1). Since home as a language domain is not functioning actively for language transmission in Miyakojima, then preschools (3–6) and elementary schools (6–12) in these phases can be the following possible language domains for the language revitalization.

Keeping this bilingual situation of language transmission in Miyakojima, I attempted a micro-educational practice: bringing a creative pedagogy, video workshop (henceforth, VW), into the classroom at a state elementary school. This paper is a report on designing a new pedagogy for language revitalization, to raise at Japanese elementary schools and concerning school children in the third phase of bilingual language development situated on a remote island where a “definitely endangered” language is still spoken.

1.2. Demography of Miyakojima and the Miyakoan Language

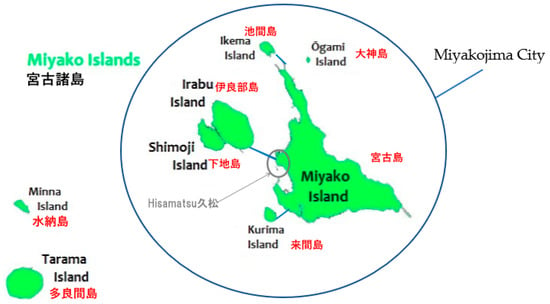

Geographically, Miyakojima consists of six islands: Ikema Island, Ogami Island, Miyako Island, Kurima Island, Shimoji Island, and Irabu Island. They are six independent islands, and in 2005, they were reorganized as a unified local government as Miyakojima City. The entire city is the size of 204 km2 and had a population total of 54,841 in April 2021 (Japan Geographic Data Center 2021). Miyako Island, on its own, is the largest in size (157 km2) and population (48,339), according to the Okinawa Prefecture (2020). However, Tarama Island and Minna Island opted to remain as Tarama Village without joining the unified Miyakojima City in 2005 (Miyakojima City Education Authority 2012, p. 562). The map of the Miyako Islands is shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The map of Miyako Islands. Source: Author added information on Creative Commons Map.

There is no unified Miyakoan language. It is, however, categorized into five major dialect groups: Miyako, Ōgami, Ikema, Irabu, and Tarama, corresponding to those five islands. Among all the dialects of the Miyakoan language, Hirara dialect is historically thought to be the standard dialect since Hirara area on Miyako Island has been the ‘socio-political center’ of Miyako Island (Aoi 2015, p. 405). In the Miyakoan language, there may be between 30 and 40 dialects based on each community of the islands (Pellard and Hayashi 2012).

1.3. Modernization and Language Policy in Japan

As a part of Japanese modernization, there are complex reasons behind the indigenous language endangerment. In this paper, I will roughly illustrate the language policy by the Japanese central government in the Meiji Period and the social discourse constructed in Okinawa Prefecture in the post-war period: one is that the language policy pressed the Japanese language into service for building the nation and the colonizing Taiwan and Korea outside Japan and the indigenous groups of Ainu and Ryukyu peoples inside Japan (Carroll 2001; Gottlieb 2005; Heinrich 2015; Otomo 2019; Twine 1991). This language standardization policy was practiced and spread through compulsory education in the school domain (Fujita-Round and Maher 2008; Heinrich 2015; Kondo 2006).

Another is that the assimilation into Japanese happened during the US Occupation Period (1945–1972). The advance was neither to the assimilation policies of the postwar US administration nor the Japanese government. However, a consensus emerged within Okinawa Prefecture based on the assumptions that the Ryukyu islands would be ceded back to Japan and that children would not achieve educational success in the future if they were not proficient in Japanese (Fujita-Round 2022a). This consensus was disseminated by a negative, school-based campaign, the Hyojungo Reiko (the movement to encourage the use of the standardized Japanese language) (Smits 1999, p. 153) led by the Okinawa Teacher’s Association and its pre-war mentality of denying any value in the local languages (Ishihara 2010). The parents’ and teachers’ assumptions motivated them to pass on the more beneficial language rather than their vernacular language for their children’s future. As a result, the vernacular languages were gradually not being transmitted in the home. Specifically, Okinawa-born in the 1950s and 1960s reported that their parents spoke to their children entirely in Japanese, discouraging them from speaking Ryukyuan languages (Ishihara et al. 2019).

According to Ishihara et al. (2019, p. 27), “if the students were found to speak the local language, they were punished by having to wear a dialect tag (hōgen fuda) around their neck.” As mentioned earlier, the indigenous Ainu and Ryukyuan peoples were assimilated through state school education, with Japanese as the medium of instruction and the humiliating dialect tag (Fujita-Round 2019, p. 174). Under the national language policy, the policy practiced in school using dialect tags impacted the language choice of speaking—not limited to Miyakoan, but all Okinawan homes and children (i.e., Miyakoan interviewees’ narratives on dialect tag experience in the video-recorded interview, ‘Hisamatsu album’ on the online archive by Fujita-Round and Hattori (2019) at 6 min 58 s (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LfVOVuj_xXg, accessed on 24 September 2022) with English subtitles).

1.4. Intergenerational Dynamics in the Family

Let me illustrate the present Miyakoan speakers from my fieldwork in 2014. In a group interview at a junior high school in Miyakojima, I asked questions to find out pupils’ reflections on the lecture on the history of Miyakojima given by a guest teacher from Tokyo. One first-grade 13-year-old pupil hesitated but said, “Why cannot I read our Miyako (Island) history in our (national) textbook?”. He meant that he had never found the history of Miyakojima embedded in the national textbook, why he was unable to study the local history of his island at school, and why the special guest from Tokyo taught their history but not his teacher. Some 41 junior high school pupils said their grandparents were Miyakoan language speakers, but all said they were not. In other words, the pupils recognized that their grandparents were bilingual speakers of Miyakoan and Japanese, but the 13-year-old themselves were not (cf. Fujita-Round (2015) on this interview results and analysis).

As seen earlier, under the national language policy, the Japanese language became the medium of education and the standard language (lingua franca) in Okinawa Prefecture. The present pupils’ grandparents were banned from speaking their vernacular language in childhood and got punished when they spoke it at school (Hammine 2020). Through schooling, the Japanese language policy transformed the Miyakoan people to use Japanese as their medium of everyday life. The home language has shifted from Miyakoan to Japanese within the family. There are intergenerational dynamics of the endangered Miyakoan language. Therefore, the bilingual acquisition degree is different according to generation and individual. Based on this dynamism, I hypothesized the bilingual use of Miyakoan and Japanese language according to roughly three generations: the first generation (the 60–90s), the grandparents of the present pupils, are active bilingual, and fluent in both Miyakoan and Japanese. The second generation (the 30–50s), the pupils’ parents, are receptive bilingual who understand Miyakoan by the first generation and are able to respond to and communicate with them but are not confident to converse fluently in Miyakoan. Therefore, the second generation may answer back to the first generation in Japanese.

Raised by the second-generation parent/s at home in Japanese, the third generation (the 10–20s) are also receptive bilinguals who understand some of the Miyakoan of first and second generations. The third generation does not speak Miyakoan fluently nor spontaneously, the same as the second generation, but may understand and use some phrasal Miyakoan and vocabulary.

In addition to the language use in the home domain, at a local community level, not at the national level, there is a fundamental societal change surrounding family language transmission. The community where I conducted the research was a lively fishing community in Miyakojima until half a century ago. In the family, the fathers used to catch fish, and the mothers used to sell them at the market and work in the field of sugarcane. There used to be many Miyakoan vocabularies for fish, sugarcane, and the names of utensils and tools for fishing and farming in everyday life. Through such everyday family conversations, those were transmitted from parents to children. However, the community was modernized. Some third-generation pupils told the researcher their dream in the future is to become a Youtuber.

My present research originally stemmed from bilingual education. In its discipline, researchers have been seeking how we should extend to understand the phenomenon of human sciences related to the social and individual acquisition of numerous languages and deliver language education to meet the present local context. In the process of going beyond the tradition of bilingualism in the 20th century, ‘multilingual turn’ is advocated by applied linguistics and sociolinguistic researchers (May 2014), the ‘ethnography and language policy’ combination to connect the bottom-up view with the top-down is raised (McCarty 2011), ‘transformative pedagogy’ and ‘new pedagogy’ for bilingual children in educational domains and schools’ action plans are voiced (Cummins 2000, 2005), and the bilingual identity and language learning is sought (Norton 2013).

Based on these current bilingualism studies, in this paper, I will explore a new pedagogy for language revitalization in the classroom, where the indigenous language used to be treated negatively, in order to reverse and revitalize Miyakoan.

2. Materials and Methods

The setting of the present study is an elementary school in Miyakojima, and the subject is focused on 11–12-year-old schoolchildren. By bringing the VW into the classroom, I will explore three research questions:

- What pedagogy might suit language revitalization.

- How the school can accommodate this educational goal.

- Will this educational plan raise pupils’ awareness to learn about the Miyakoan language?

The first question explores the new pedagogy for the Miyakoan language revitalization, and the second is to negotiate the compatibility between the new pedagogy and the mainstream school curriculum. The third question is to observe pupils’ language awareness and identity concerning the Miyakoan language. Minoura’s (2003) findings in her qualitative research showed that Japanese children who lived abroad and had intercultural experiences were gaining their self-identity between 13–15 years old. Therefore, this study also focuses on schoolchildren’s identity issues in language revitalization.

2.1. Elementary School in Miyakojima

Japanese compulsory education is a total of nine years. In addition to compulsory education, the ratio by the Japanese government shows that 95.5% of the compulsory education graduates entered senior high school in 2020 (MEXT 2020). Thus, present Japanese children generally undergo 12 years of formal education: elementary school (6–12 years old), junior high school (13–15 years old), and senior high school (16–18 years old). In the case of Miyakojima, the distribution of these schools and pupils/students is summarized below.

For education from 6 to 18 years old, there are 30 schools (plus one Special-needs school) and 6419 students in Miyakojima in 2021, as in Table 1. However, being peripheral and remote islands away from the central Japan, there is no institution for higher education in the city. Mr. Kazuhiko Kakihana, a senior officer of the Miyakojima City Hall Office, analyzed the city’s data in March 2014. There were roughly 500 graduates from senior high schools. Among those 18-year-olds from Moyakojima City, 68% chose further education (universities or technical colleges), 22% gained employment outside the island, and only 10% stayed in the city, according to the interview by the author (author’s fieldnote recorded on 13 July 2015). The number in Table 1 also shows that hundreds of local junior high school graduates opt for senior high schools outside Miyakojima.

Table 1.

The Schools of Miyakojima City (April 2021). Source: Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education (2021).

For these reasons, implementing language revitalization during compulsory education, elementary and junior high school is vital in the context of Miyakojima while the pupils are still living with the family and go to the local school in the community.

2.2. Ethnography as Methodology

The methodology of the current research employed an ethnographic and case study approach. The ethnographic approach is often referred to as ‘linguistic ethnography’, or ‘linguistic anthropology’. The former is referred to more broadly in Europe among applied linguists and sociolinguists, whereas the latter in the U.S. among sociolinguists and linguistic anthropologists. Both owe their roots to John Gumperz and Dell Hymes (McCarty 2011, p. 11; Rampton et al. 2015, p. 19). McCarty (2011, p. 10) explains “that tradition is characterized by the contextualization of cultural phenomena socially, historically, and comparatively across time and space”, so that the ethnographic approach enables one to show the relationships between language use and people in the specific context and time.

Canagarajah (2006) views language policy as working “in a top-down fashion to shape the linguistic behavior of the community according to the imperatives of policy-makers”. In contrast, ethnography “develops grounded theories about language as it is practiced in localized contexts” (Canagarajah 2006, p. 153). He pointed out that ethnography helps (1) develop hypotheses in context and (2) bring social and linguistic relationships in diverse geopolitical contexts (pp. 154–55). From this point, planning a micro-policy in the community- or school-based ethnography is beneficial to localize the plan to fit in the specific context.

Before this study, I extensively conducted fieldwork in communities in Miyakojima from 2012. I have been visiting and participating in language domains in two communities, such as the institutions (nursery schools, schools, elderly homes, and library) and individual language practices (family, community, classrooms, bookshop, book-reading club, and after-school activities). My methods in the fieldwork mainly were participant observation (fieldnotes, photographs, and video recording) and semi-structured interviews (transcriptions), and sometimes questionnaires at school (pupils’ reflection and their background data).

In addition, I extended the research method to document interviews recorded in video by a video artist who has been my research collaborator since 2015. Later, we created a 48 min-documentary film entitled “The Future of Myaakufutsu [Miyakoan language]: Vanishing Voices and Emerging Voices” in 2019 (KAKENHI Project No. 18K00695). In this way, together with the conventional ethnographic research methods, I created a documentary video ethnography of Miyakojima. In principle, a documentary film would advocate language endangerment for islanders in Miyakojima (Fujita-Round 2022b). This reaction from the islanders convinced the researcher to advance to implement video workshops with my collaborator in the school domain.

2.3. Video Workshops as an Informal and Creative Pedagogy

In Section 1.4, I articulated my hypothesis of intergenerational dynamism in Miyakojima from my longitudinal fieldwork. The new approach to pedagogy is essential to target the younger third generation who do not speak Miyakoan fluently nor understand it spontaneously. Since Miyakoan is a vernacular and spoken language, formal written text-based education is not realistic. Even more, no textbooks of the Miyakoan language were available for the school pupils. A new approach to pedagogy, different from formal language education, must be sought.

In this circumstance, I adapted the video workshops (henceforth, VW) developed by Mr. Hattori, my research collaborator, and the video artist. This art-based VW seemed compatible and could reveal ‘unspoken’ Miyakoan or cultural values that the third-generation pupils may have. It was a challenge to go beyond ‘language education’ for revitalization. It looked worthwhile to construct a pedagogy combining heritage language education and art-based creative pedagogy from my career of teaching intercultural training. The detail of the VW will be described in the later section.

To practice this new pedagogy, another key person and my long-term collaborator in the field, Mr. Kondo, agreed to coordinate the VW, who was an elementary school teacher and a senior curriculum coordinator at the time. He suggested scheduling VW once a term, resulting in three workshops as a course for the academic year within the curriculum of Sogogakushu-no-jikan (Integrated Study). The integrated study is a part of the national curriculum. Each school can choose alternative educational programs depending on the school’s needs. Despite our intention to revitalize the language and seek a new pedagogy, Mr. Kondo foresaw the VW fitting in the keywords—digital, programming, and communication—within the Integrated Study. First, these keywords did not seem to justify Mr. Hattori’s VW and my intention for language revitalization to the author. However, creating a new pedagogy was a positive challenge. As a team, we challenged this VW to open up a new ‘space’ for language revitalization, mainstream education, and communication among pupils. The researcher understood the VW as a ‘visual turn’, a new methodological turn on multilingualism (Kalaja and Melo-Pfeifer 2019, p. 4).

In this way, the VW was conducted and aimed at activating the third-generation pupil’s receptive Miyakoan language.

3. Results

The VW was conducted in the academic year of 2019 at Hisamatsu elementary school (henceforth, HES) from June 2019 to January 2020, along with the Japanese school calendar starting from April. It was planned and carried out by a team of three prominent members: the local contact, Mr. Kondo (elementary school teacher), the facilitator of VW, Mr. Hattori (video artist), and the project leader, the author (sociolinguistic researcher).

3.1. Mr. Hattori’s Video Workshops

In HES, the total number of pupils for six grades was 337 in 2019. Mr. Kondo and I selected the sixth grade (11–12 years old pupils) for the VW. There were two classes of 43 pupils in the sixth grade, about 20 pupils per class. 90 min (two 45 min lessons at elementary school) as one unit was planned for one VW session. The three workshops (six lessons) were allocated within the annual integrated study.

In the classroom, before each workshop, the desks and chairs were pushed to the back, and homeroom teachers helped us divide 20 pupils into five groups (four pupils each) according to the request of Mr. Hattori. Figure 2 shows the image of VW in the classroom: Mr. Hattori in the front, the Homeroom teacher, pupils, and Mr. Kondo at the side in the classroom photographed by the author. During the VW, other teachers, including the deputy head and head teacher in the school, freely came to observe. The homeroom teacher in each class stayed with us to support the pupil’s management and participated in the role to start the activity.

Figure 2.

Video Workshop at H elementary school (10 June 2019).

At the beginning of the VW, pupils were divided into groups, and each picked up an iPad. This was before COVID-19, so, for some pupils, it was their first time handling a tablet. The overall aim of the VW by Mr. Hattori was (1) to get familiar with the iPad for all pupils, (2) to learn the basic skills of taking a movie and editing it, and (3) to acquire communication skills through group work. He emphasized the importance of letting pupils familiarize themselves with communication skills and collaboration in a group throughout the VW, not only learning the know-how in handling the machine or making a movie as a result.

The description of the VW’s dates and theme on the day is summarized in Table 2. In the three VW sessions, he prepared a syllabus to make a movie along the steps he aimed at each session.

Table 2.

Video Workshop schedule date and theme.

The basic flow of the VW is as follows:

- (1)

- Orientation of the day, what to make, and rules for working as a group.

- (2)

- Hands-on experience filming by iPad (when the task is new, watching the model video to understand before filming).

- (3)

- Group work either inside the classroom or outside the classroom.

- (4)

- Editorial work in the classroom.

- (5)

- Films are shown at the end of the session and feedback is given.

The device and applications used for the VW are shown in Table 3 as follows:

Table 3.

Tools for Video Workshops.

3.2. The Description of Three Video Workshops

This VW was programmed initially by Mr. Katsuyuki Hattori (video artist) and Ms. Akie Komatsu (junior high school art teacher). They implemented the VW at school within the educational curriculum based in Tottori Prefecture in Japan. They made the 10th anniversary VW booklet in 2020. The booklet introduced the six VW programs of movie-making skills from basic to improvisation. They tailored the VW to the Japanese school context and constructed the ten rules for the VW class: (1) make enjoyable content for everybody, (2) treat ICT devices carefully, (3) ensure safety during filming, (4) make everybody in the group actor, director, and cameraman in the movie you make, (5) make sure to record the sound of the movie clearly and pleasantly, (6) use subtitles on the screen and sound effects to enrich the movie for an audience, (7) ask and consult with other people, friends, and teachers when you do not understand what to do, (8) keep the rights and laws in mind when you express your idea, (9) make the best movie you can make within the time you are permitted, (10) watch the movies you made with your classmates and friends!

Thus, this VW is summarized as a creative approach in nature and an art-based program for school pupils. From the professional artist’s point of view, Mr. Hattori contextualized the movie theories and skills at the pupil’s level, whereas Ms. Komatsu situated the video workshop in the national curriculum guidelines as a junior high school art teacher: they explained the connection between “to extend the potentials of artistic expression” in the national guidelines’ aim of “the effective use photography, movie, ICT, etc.” and this VW, in the unpublished VW booklet.

This time, we conducted a VW led by Mr. Hattori in a new school without Ms. Komatsu. Therefore, the HES team prepared well enough in advance. So, the VW with the flavor of language revitalization started at HES in Miyakojima.

3.2.1. Video Workshop 1: Hands-on iPad and iMovie to Do Three Short Tasks

For VW 1, following an orientation, each group was given a tablet. Mr. Hattori instructed the pupils to use the tablet, which icon to press, and start filming. Immediately after the simple explanation, the group work started.

As in Table 2, there were three tasks for the day: (1) the self-introduction movie, (2) the word chain game movie, and (3) the throwing a ball movie.

For the first task, each pupil introduced themselves in front of the camera (iPad), and the next person filmed the introduction seen in Figure 3. When it went one round, Mr. Hattori explained how to edit what they recorded on the iPad using the iMovie application. All the pupils followed his instruction without problems.

Figure 3.

Filming self-introduction in turn.

As applied to the first task, the second and third tasks were framed consequently as their familiar word chain game and throwing ball action. The second task will be analyzed in depth later in Section 4.1.

For the first and second tasks, each pupil turned to film a friend’s speech/word using the iPad. For editing, they worked as a group. It was a hands-on method. Therefore, pupils could seek help from Mr. Hattori anytime in Figure 4. For the third task, pupils saw some sample movies first and got the idea of what they would make under ”Throwing a ball movie”. It was when pupils were encouraged to go outside the classroom to film as a group and were informed to come back when they finished filming for editing. All groups went in different directions; Mr. Hattori was busy following up.

Figure 4.

Hands on and editing on iPad.

Pupils completed three short films within 90 min and watched the movies together with laughter in the classroom at the end of the session.

3.2.2. Video Workshop 2: A Big Tree Story Movie

For VW2, it was the task of creating their movie titled “There is a big tree”. It was not as easy as the previous tasks. For the short and easy tasks of VW1, pupils could follow the instruction within the shared frames, such as self-introduction, game, and ball-throwing action. This VW2 required each group of pupils to create their original story, outline, and movie scripts within the limited time before acting and filming. The group had to discuss and decide which tree in the schoolyard they would refer to and how they would like to contextualize the story in the title.

On this day, Mr. Hattori showed the sample movie more to hint at how to visualize a ‘big’ tree. He also mentioned the technique of how they could make a short tree bigger in the movie by changing the angle, for example. Then, he quickly reviewed the basic knowledge of handling the ICT device and let the group write a story on the big sheet on the classroom floor (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Writing their story of the tree.

The paper was larger drawing paper on which they could write movie scripts and memos during their brainstorming.

Each group (a) first discussed and wrote a story of ‘one big tree’ as the theme; (b) second, once Mr. Hattori approved their story, they went outside the classroom to film the story of a big tree using the actual tree in the school ground as in Figure 6; (c) third, came back to the classroom in time for editing to complete their movie. At the end of the session, the class watched their original movies.

Figure 6.

Acting and filming the story.

As the result of the VW2, two groups out of ten wrote their stories connecting to an Okinawan folktale, Kijimunaa, the spirit believed to live in the Gajumaru (Ficus microcarpa) tree and pupils acted an image of Kijimunaa in the schoolyard as in Figure 6.

3.2.3. Video Workshop 3: Animation Movie

Based on the previous two VWs, this workshop was slightly advanced. This time, an iPad application called ‘Stop Motion’ was introduced, and pupils made an animated movie. Mr. Hattori first gave an orientation and explained a theory of a ‘frame-by-frame’ movie to make an animation movie. Then, he showed sample movies and explained how to use the Stop Motion application.

In the flow of VW, (a) each group first had to decide what/whom to animate and obtain actual materials; (b) second, they subsequently recorded the object frame by frame as in Figure 7 and Figure 8; (c) third, they needed to edit all the frames patiently. When some groups discovered and inserted sound effects in the movie, it suddenly motivated the other groups. Those who struggled to record and edit the frame to make their animation movie and lost their patience were sparked by the new function. In this session, some groups could not come up with an idea at the beginning, so Mr. Hattori helped and gave them more practical advice for each group than the previous times.

Figure 7.

Acting and filming on the corridor.

Figure 8.

Making their own idea into movie.

In the next section, I will discuss my findings referring to the three research questions (henceforth, RQ): (1) what pedagogy might suit language revitalization, (2) how the school can accommodate this educational goal, and (3) will this educational plan raise pupils’ awareness to learn about the Miyakoan language.

4. Discussion

4.1. Translanguaging between Miyakoan and Japanese

For analysis, first, I will focus on the second task, ‘word chain game movie’ in VW1, to discuss the language revitalization perspective. The word chain game (Shiritori asobi) is a familiar children’s game in Japan.

It is played by taking the last syllable of a word given by someone else, and the next person must start a new word that begins with that last syllable. The syllable is “an abstract unit explaining how vowels and consonants are organized within a sound system (Crystal 2010, p. 172)”. In Japanese, each letter stands for a single syllable sound, a combination of vowels and consonants.

I will show the actual word chain game in VW1 in Table 4 as examples. Pupils in Miyakojima were familiar with the Japanese word chain game. Thus, they combined this frame of game and filming without any difficulties. In VW1, there were ten groups in total. However, due to a technical problem, seven movies were recorded on the iPad, and three movies were erased. The transcription of the word chain game by seven groups is below:

Table 4.

The transcription of the Japanese word-chain game.

In the example of Group 1, the game started with the homeroom teacher’s first name, ○○ya, the word starting with the last syllable from the previous word, in this case, /ya/, the next person found a word starting from /ya/, ’Yambarukuina [Okinawa rail (bird)]’. So, Yanbarukuina’s last syllable, /na/, was followed by ‘nasu [aubergine]’.

Among these examples, Group 7′s chain is an example of translanguaging; the language switches from one to the other without being interrupted. In this chain, the final syllable /n/ is used three times, mikan (tangerine), chikan (pervert), and chikin (chicken (a foreign loan word in Japanese)). If it is a usual word chain game, the person who used /n/ loses the game and ends the whole game, because in Japanese, /n/ is one single consonant, not a syllable as the other letters. However, Group 7 continued the game by mixing Miyakoan words, such as ‘ngyamasu [noisy/shut-up]’ and ‘nmyaachi [welcome]’, avoiding the end. In Miyakoan, there exist words starting with one single consonant /n/.

Looking at this example closely, I showed the speaker of each word according to the chain order in Table 5. There were four pupils, A, B, C, and D, in Group 7, two girls and two boys. When the homeroom teacher, T, started her word, ‘Grade 6th, Class 2′, in this chain, this boy, A, had 4 turns: (1) mijinko, (2) karasu, (3) ngyamasu, and (4) nmyaachi; 3 and 4 are Miyakoan.

Table 5.

Detailed transcription of G7 word chain.

On the day, I witnessed pupil A switched between Japanese and Miyakoan freely in the chain game. After the chain game, while other group members were editing, I asked A why he knew those two words. He answered, “my grandma always shouted at me, ‘ngyamasu [noisy/shut up]’”. So, these third-generation pupils learned the word in the family domain through a natural interaction with fluent speakers. Then, he also said, “you know ‘nmyaachi’ is written publicly, like at the airport, so I learned the word”. ‘Nmyaachi [welcome]’ is written on posters at the airport and souvenir shops. As he described ‘publicly’, it became a common phrase for tourists, as authentic Miyakoan language.

This finding indicates that the third generation can use some Miyakoan words they learned at home and in public in Miyakojima if they would like to, in a comfortable space, speak their minority language. At the beginning of the game, Mr. Hattori told the pupils, “You are very lucky to be in Miyakojima because you can use the Miyakoan language, which can start with ‘n’. It means you can continue this chain game forever, not beaten at all”. Pupil A uttered Miyakoan words because he received this strong message from the facilitator, permitting pupils to use Miyakoan in the game and encouraging them to do so. This language attitude of the senior person and instruction in the classroom created a relaxed space for pupils to mix their word-level Miyakoan.

4.2. Informal Classroom and Creative Pedagogy

Pursuing further to this ‘relaxed’ space, I can point out that Mr. Hattori intentionally made the VW informal. For example, he requested homeroom teachers to push back all the desks and chairs to visibly transform the classroom from formal to informal.

Practically, space-wise, the VW needed the open space; however, as in Figure 4 and Figure 5, Mr. Hattori did not scold the pupils even if they lay down on the floor and relaxed during the VW. It indicates that the VW produced an informal and unique atmosphere, different from everyday formal mainstream education. In other words, by constructing such an informal space, the pupils changed their attitudes toward what they would like to switch their language freely.

Another example of making the classroom unique is that at the beginning of VW1, Mr. Hattori introduced himself as ‘Mojya sensei (Mr. Curly)’ by his nickname featuring his curly hair to build a good rapport with pupils. These implicit but visible efforts by the artist made the classroom a comfortable space for pupils.

I received 42 feedback sheets from the pupils after VW1. Many commented that it was fun learning the iPad and how to make a movie. Some of them added that they learned how to communicate with a friend in VW, which was one of Mr. Hattori’s aims for the VW. The same Pupil A in Section 4.1 commented, “apart from what we learned, I found it was fun using the Miyakoan dialect (language) to avoid losing the game”. He showed a positive attitude toward Miyakoan use. One pupil commented that she was grateful to learn how to use the tablet in an “enjoyable” way, and in making a movie with her group members, she found she became “closer” to the group members. The same pupil wrote the description of the class that all her classmates were smiling while watching the movies they made at the end of the class, so seeing everybody happy made her very happy.

These children’s experience and observation in the VW explained that the classroom could become a comfortable space and, in this atmosphere, they may be able to use the minority language without being criticized by classmates and teachers.

4.3. Focused more on the Third-Generation Speaker for Language Revitalization

The relationships between language and domain are firmly connected for language speakers. Miyakoan speakers used to be punished for speaking their language at school and stopped speaking the language in the school domain, as mentioned earlier.

The limitation of my study is the educational implementation was only conducted in one school and three days within one academic year. Recognizing this limitation, I cannot theorize or show the tendencies of the VW and heritage language pedagogy from an essentialist point of view. On the other hand, in my case study, I can suggest some implications for the new pedagogy and practice.

Generally, bringing a ‘native’ speaker into the classroom for heritage language education is often the case. It is important to learn the spoken language from a fluent speaker who mastered the language. However, considering language revitalization, particularly at school, the practitioners/teachers should be aware that bringing a first-generation fluent speaker as a guest into the classroom accompanies the ideology of ‘authority’. In the past, I saw the ‘native’ speaker had a belief to help and teach his/her ’language’. The guest speaker feels responsible for transmitting their ‘beautiful’ language to the younger people. In their belief, they behaved like a ‘teacher’, following the rigid and formal education pedagogy to ‘teach’ and ‘transmit their language’ because they were educated to learn that way at ‘school’.

In my study, instead of bringing the first generation as a language resource at school, I focused more on the third-generation pupils’ potential Miyakoan and how they could release and utter their unrecognized knowledge of Miyakoan. Therefore, I aimed at a new pedagogy and excluded traditional language-teaching methods to remind pupils to ‘teach’ Miyakoan as the subject, but adapted VWs, which are entirely different from language teaching on the surface.

Excluding ‘authority’ and formal pedagogy, in my case, the formula was bringing an artist who was ‘not teaching’ the language but ‘collaborating’ with the school to construct informal pedagogy and a comfortable classroom.

Referring to RQs 1 and 2, I suggest this informal and creative pedagogy will be essential under the educational implementation for future language revitalization. Additionally, to plan heritage language education, it is advisable to consider collaboration with some specialists outside the school and make an effort to collaborate with them. Collaboration with specialists outside school can be a lesson for teachers and schools if they change the angle to see the new pedagogy. Not only teaching heritage language, but the school set this new approach goal with the school’s benefit.

4.4. Creative Pedagogy for Spoken Language Revitalization

Reminding the utterance of Miyakoan words by Pupil A saved the group from continuing the word chain game. There was another pupil’s comment from Pupil A’s group. In the comments, another pupil mentioned it was fun to know her friend used Miyakoan to continue the word chain game; she heard and recognized what the other pupil used was Miyakoan. In this way, if the third generation were placed in a situation to ‘speak’ the Miyakoan words and language, peer classmates and friends could also hear Miyakoan.

As I mentioned earlier, teachers and researchers tend to believe that first-generation, fluent speakers should speak to pupils with the same logic as native speakerism. Holiday (2006) argued that native speakerism is “a pervasive ideology within ELT (English Language Teaching), characterized by the belief that ‘native-speaker’ teachers represent a ‘Western culture’” (Holiday 2006). Thus, we need to be aware of this native-speakerism idea and not blindly rely on the first generation as the authority for the school domain.

Another point I would like to articulate again is that the Miyakoan and Ryukyuan languages are ‘spoken’ languages. In this paper, I focus on language transmission for the younger generation. In this sense, those targeted third generations are still acquiring their ‘spoken’ Japanese language and overall literacy (knowledge) at school. Cummins (2000) highlighted the distinction between conversational fluency, “basic interpersonal communicative skills (BICS)” and academic aspects in acquiring a second language, “cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP)” for the context of immigrant children. Applying this to the plan of language revitalization for Miyakoan pupils, the goal of the plan is the former, the basic interpersonal communicative skills of Miyakoan.

Like Pupil A, some third-generation individuals have basic knowledge of the Miyakoan language and a foundation in speaking and listening skills. If they are heritage language learners, language revitalization education will target listening and speaking skills. To be able to listen and speak in learning Miyakoan at school, as we discussed here, constructing the classroom as being a relaxed, informal, and comfortable space is one key aspect to consider. The visible and invisible conditions of the classroom encourage translanguaging between dominant Japanese and minority Miyakoan as well. The pedagogy for language revitalization needs to be locally adjusted depending on the educational goal, according to the school.

Heritage language education and indigenous/endangered languages’ revitalization are not recognized at the national level in Japan. McCarty et al. (2006) stated that it is not difficult to imagine the bilingual and multilingual use of the languages; however, “the problem is that education policies and practices often deny that multilingual, multicultural reality, attempting to coerce it into a single, monolingualist and monoculturalist mold” (McCarty et al. 2006, p. 81). On the other hand, there are models of new pedagogy around the world. One of the examples is ‘multiliteracies’. Reforming school education to meet with social changes, ‘multiliteracies’ encompass a new pedagogy for ‘changing realities’ and ‘designing social futures’ (Cope and Kalantzis 2000, p. 5). Their advocacy of seeking new pedagogy “to meet with the social change” overlaps on the former government report published by the Japanese ministry of education (MEXT White Paper 2011).

Not depending on the national level, but, like the VW in this paper, bringing a packaged educational program in the ‘integrated study’ at school was feasible. The question of how the school can accommodate the educational goal depends on whether the school can independently plan the syllabus on language revitalization or local studies or collaborate to implement an extra-curriculum plan with some specialists on the language or new pedagogy. Like the Hawaiian language, in 1983, a language revival program was started by educators with a core of fifty children, and now there are thousands of speakers (Maher 2017, p. 129). In this study, the role of Mr. Kondo, the senior educator and curriculum coordinator, was essential to the new educational practice.

Anderson (2017) affirms that a multiliteracies view and the critical, dialogic pedagogy help to build “awareness of the intersections between multilingualism and multimodality” (p. 251). Referring to RQ3, new pedagogy and educational practice in the classroom for language revitalization can be further developed to raise awareness of third-generation pupils.

5. Conclusions

In globalized society, each person is a potential bilingual or multilingual. Being bilingual is a nuanced and layered form of language life. Each person is a potential bilingual (Fujita-Round 2019, p. 170). This assertion holds whether a person is classified as majority/minority, indigenous or migrant, or a language learner on the road to the possession of another language.

Education transmits the majority views about language, history, and culture, and disconnects children from their heritage. In the earlier example of my interviewee, he was uncertain about the special class on his own island taught by an outsider. He had such awareness of feeling awkward about the class he attended. He was 13 years old then; if he had been younger, perhaps he would not be aware.

The first generation of the Miyakoan language was losing their identity and language, being punished at school when they spoke their vernacular language in childhood. In the same childhood period, pupils at elementary and junior high school can start revitalizing their awareness of community language through a small plan such as a VW. In this paper, when creative pedagogy was applied, the finding revealed that some third-generation individuals still knew some Miyakoan words. Admittedly, this paper has a limitation, with it being a case study of one educational plan in 2019. However, this small educational plan, a VW, did inspire pupils to re-evaluate their Miyakoan language.

The Hisamatsu community gains ‘new’ residents outside the community, from other parts of Miyakojima and Okinawan islands, and even from mainland Japan. Thus, there are not only children who have the ancestral tie to the community at the school. This ‘globalization’ brought more diverse issues to the community. These issues, as commonly presented in popular discourse, usually elicit a sympathetic response. However, the problem of language endangerment in this context cannot be solved by sympathy; it requires the direct intervention of revitalization. “Multilingualism and transnationalism are intimately tied to globalization, which affects policies related to citizenship, education, language assessment, and many other areas of 21st-century applied linguistics and society” (Duff 2015, p. 61). In this sense, the crystallization of language under the term ‘heritage’, which indicates the ancestral tie, should be questioned.

The native speakerism of the older generations should also be questioned, and the potential of new third- and fourth-generation speakers should be more valued. Being less fluent speakers, third- and fourth-generation speakers are more likely to use translanguaging, which is concerned “not only with the meaning of language and communicative practices, but also with how such meanings are generated” (Bradley et al. 2020, p. 2).

What the VW suggests is concerned with classroom and school education. Within the independent study as a part of the school curriculum, the VW played a role of an art-based program for school pupils. As the only elementary school in the community, HES will take a good role in being a domain for language revitalization of the Hisamatsu vernacular of the Miyakoan language. If the schools used to be “sites for the creation of norms and hierarchies that devalue minority groups, they could also be sites of struggle to change these norms and to create societies in which youth may develop as bilingual or multilingual speakers of heritage or Indigenous languages” (Hornberger and De Korne 2018, p. 95). The goal of language revitalization in this sense is not necessarily a matter of fluency or proficiency in the language system but paying more attention to revitalizing the language awareness of the young speakers.

Finally, the role of the researcher is questioned concerning language transmission. The Miyakoan language has shifted from the home and societal spoken language in the 19th century to the heritage language, which only remains among the grandparents’ age. It is the reality and accords with the language endangerment discourse. In reality, there is a precise gradation of bilingualism of the Miyakoan language and Japanese within the family’s three generations—children, parents, and grandparents in the 21st century. While this gradation of bilingualism stays and Miyakoan lives, researchers of endangered languages can take action to help extend the language domains on a broader scope: in the physical space of learning at home, school, and community, together with the virtual language domain on the internet in the form of visual and audio. Documenting and creating learning resources to be able to use the endangered languages should be explored further.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18K00695.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the JSPS Kakenhi guidance, and at the point of writing this paper, the consent forms of all children and parents in the photographs were submitted to the editorial board and approved.

Informed Consent Statement

Written consents were obtained from all subjects in the photographs involved in the study and their parents in addition to the school’s.

Acknowledgments

I thank all the pupils and schoolteachers of Hisamatsu Elementary School who participated in the Video Workshops in 2019, and our team, Kondo and Hattori.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, Jim. 2017. Engagement, multiliteracies, and identity. In The Routledge Handbook of Heritage Language Education. Edited by Olga E. Kagan, Maria M. Carreira and Claire Hitchens Chik. New York: Routledge, pp. 248–62. [Google Scholar]

- Aoi, Hayato. 2015. Tarama Miyako grammar. In Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. Edited by Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho Miyara and Michinori Shimoji. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 405–21. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, Peter, and Julia Sallabank. 2011. The Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Jessica, Emilee Moore, and James Simpson. 2020. Translanguaging as transformation: The collaborative construction of new linguistic realities. In Translanguaging as Transformation: The Collaborative Construction of New Linguistic Realities. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, Suresh. 2006. Ethnographic methods in language policy. In An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Methods. Edited by Thomas Ricento. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 153–69. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Tessa. 2001. Language Planning and Language Change in Japan. Richmond: Curzon. [Google Scholar]

- Cope, Bill, and Mary Kalantzis. 2000. Introduction; multiliteracies: Beginnings of an idea. In Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. Abington: Routledge, pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, David. 2010. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 2000. Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, Jim. 2005. A proposal for action: Strategies for recognizing heritage language competence as a learning resource within the mainstream classroom. The Modern Language Journal 89: 585–92. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, Annick. 2021. Bilingual Development in Childhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, Patricia A. 2015. Transnationalism, Multilingualism, and Identity. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 35: 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita-Round, Sachiyo. 2015. Nurturing Awareness of Language Inheritance at School: Educational Practices Raising Self-esteem in Miyako City, Okinawa Prefecture [Gakkokyoiku no nakade gengokeisho eno kizuki wo sodateru: Okinawaken Miyakojimashi deno jisonkanjo ni tsunageru kyoikujissen]. Educational Studies 57: 175–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita-Round, Sachiyo. 2019. Bilingualism and bilingual education in Japan. In The Routledge Handbook of Japanese Sociolinguistics. Edited by Patrick Heinrich and Yumiko Ohara. Abington: Routledge, pp. 170–83. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita-Round, Sachiyo. 2022a. Language communities of the Southern Ryukyus. In Language Communities in Japan. Edited by John C. Maher. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita-Round, Sachiyo. 2022b. Weaving the voices of speakers of endangered languages into an ethnographic documentary film: “The Future of Miyaakufutsu (Miyakoan Language): Vanishing Voices, Emerging Voices”. In Linguapax Review 2022: Cinema and Language Revitalisation. Barcelona: Linguapax International. Available online: https://www.linguapax.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Linguapax-2022-Cinema-and-language-revitalisation.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Fujita-Round, Sachiyo, and John C. Maher. 2008. Language education policy in Japan. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2nd ed. Edited by Stephen May and Nancy Hornberger. New York: Springer, pp. 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita-Round, Sachiyo, and John C. Maher. 2017. Language Policy and Political Issues in Education. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 3rd ed. Edited by Teresa McCarty and Stephen May. New York: Springer, vol. 1, pp. 491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita-Round, Sachiyo, and Katsuyuki Hattori. 2019. Hisamatsu Album. In Live Multilingually Project Online Video Archive on Youtube Page. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LfVOVuj_xXg (accessed on 24 September 2022).

- Gottlieb, Nanette. 2005. Language and Society in Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammine, Madoka. 2020. Educated Not to Speak Our Language: Language Attitudes and Newspeakerness in the Yaeyaman Language. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education 20: 379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, Patrick. 2015. Japanese language spread. In Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages: History, Structure, and Use. Edited by Patrick Heinrich, Shinsho Miyara and Michinori Shimoji. Berlin: Waler de Gruyer, pp. 593–611. [Google Scholar]

- Holiday, Adrian. 2006. Native-speakerism. ELT Journal 60: 385–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, Nancy H., and Haley De Korne. 2018. Is revitalization through education possible? In The Routledge Handbook of Language Revitalization. New York: Routledge, pp. 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Masahide. 2010. Language policies on Ryukyuan languages [Ryukyu shogo wo meguru gengo seisaku]. In Okinawa and Hawai, Islands as Contact Zone [Okinawa-Hawai―kontakuto-zon to shite no tosho]. Tokyo: Sairyusha, pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Masahide, Katsuyuki Miyahira, Gijs van der Lubbe, and Patrick Heinrich. 2019. Ryukyuan sociolinguistics. In The Routledge Handbook of Japanese Sociolinguistics. Edited by Patrick Heinrich and Yumiko Ohara. Abington: Routledge, pp. 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Geographic Data Center. 2021. Miyakojima City, Okinawa Prefecture. Population and Family Data. Available online: https://www.kokudo.or.jp/service/data/map/okinawa.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Kalaja, Paula, and Silvia Melo-Pfeifer. 2019. Introduction. In Visualising Multilingual Lives: More than Words. Edited by Paula Kalaja and Silvia Melo-Pfeifer. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, Kenichiro. 2006. Education and National Integration in Modern Age Okinawa [Kindai Okinawaniokeru Kyoiku to Kokumintogo]. Hokkaido: Hokkaido University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, John C. 2017. Multilingualism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, John C., and Gaynor Macdonald. 1995. Diversity in Japanese Culture and Language. London: Kegan Paul International. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, John C., and Kyoko Yashiro. 1995. Multilingual Japan. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- May, Stephen. 2014. The Multilingual Turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and Bilingual Education. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, Teresa L. 2011. Ethnography and Language Policy. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty, Teresa L., Mary Eunice Romero, and Ofelia Zepeda. 2006. Reimaging multilingual America: Lessons from Native American Youth. In Imagining Multilingual Schools: Languages in Education and Glocalization. Edited by Ofelia Garcia, Tove Skutnabb-Kangas and Maria E. Torres-Guzman. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- MEXT (The section for Primary and Secondary school education). 2020. The Fact of Senior High School Education Report. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/a_menu/shotou/kaikaku/20210315-mxt_kouhou02-1.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- MEXT White Paper. 2011. The Vision for Information and Communication Technology in Education: Aiming New Learning and Schools toward the 21st Century (Published 28 April 2011). Available online: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.mext.go.jp/component/a_menu/education/micro_detail/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2017/06/26/1305484_01_1.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Minoura, Yasuko. 2003. Intercultural Experiences of Childhood: Psycho-Anthropological Study on the Process of Human Identity Construction [Kodomo no Ibunkataiken: Jinkakukeiseikatei no Shinrijinruigakuteki Kenkyu]. Tokyo: Shinshisakusha. [Google Scholar]

- Miyakojima City Education Authority. 2012. The History of Miyakojima City. Miyakojima City: The Committee of the Miyakojima City History, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, Bonny. 2013. Identity and Language Learning: Extending the Conversation, 2nd ed. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education. 2021. The list of Schools in Okinawa Prefecture in 2021. Available online: https://www.pref.okinawa.jp/edu/edu/sagasu/index.html (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Okinawa Prefecture. 2020. Demography and Geography. Available online: https://www.pref.okinawa.jp/toukeika/youran/R03/R03youran02.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Otomo, Ruriko. 2019. Language policy and planning. In The Routledge Handbook of Japanese Sociolinguistics. Edited by Patrick Heinrich and Yumiko Ohara. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Pellard, Thomas, and Yuka Hayashi. 2012. Phonology of Miyakoan dialects [Miyakoshohōgen no onin]. In General Study for Research and Conservation of Endangered Dialects in Japan: Research Report on Miyako Ryukyuan. Tokyo: National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, pp. 13–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rampton, Ben, Janet Maybin, and Celia Roberts. 2015. Theory and method in linguistic ethnography. In Linguistic Ethnography: Interdisciplinary Explorations. Edited by Julia Snell, Sara Shaw and Fiona Copland. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 14–50. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, Gregory. 1999. Visions of Ryukyu: Identity and Ideology in Early Modern Thought and Politics. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘I Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto, Yoshio. 2003. An Introduction to Japanese Society, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Twine, Nanette. 1991. Language and the Modern State: The Reform of Written Japanese. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2003. Language Vitality and Endangerment. Paris: UNESCO. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/Languagevitalityandendangerment (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- UNESCO. 2009. UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger of Disappearing. Paris: UNESCO. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/en/atlasmap/language-id-2744.html (accessed on 31 December 2021).

- Yamamoto, Masayo. 2001. Language Use in Interlingual Families: A Japanese-English Sociolinguistic Study. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).