Abstract

Noun–noun concatenations can differ along two parameters. They can be compounds, i.e., single words, or constructs, i.e., constituents, and they can have modificational non-heads or referential non-heads. Of the four logical possibilities, one was argued not to exist: compounds of which the non-head is referential were considered to be principally excluded. In this article, I argue that Dutch has compounds with a referential non-head. They resemble the Dutch s-possessive in that their non-heads involve movement to a referential layer. However, unlike the possessive structures, the compounding structure contains head incorporation which results in word-hood. The article further discusses title expressions, such as Prince Charles, which are argued to be referential construct states. Together with the syntactic structure of titles plus proper names, the referential compounds further contribute evidence to the idea that a ban on N-to-D movement for certain uniquely referring roots, such as sun and Bronx, is extra-syntactic.

1. Introduction

In syntactic theory, it is a common assumption that verbs can select noun phrases as their arguments and assign case to these noun phrases. From a selectional point of view, it is, in contrast, a more puzzling situation for nouns or noun phrases themselves to form syntactic units with other nouns or noun phrases. It is therefore of interest to study what the principles are behind noun–noun concatenations. These are units in which several nouns or noun phrases form a structure, without the presence of a preposition or case morphology that would license the syntactic selection.

This article presents three types of Dutch noun–noun concatenations which all share the fact that the non-head noun is referential, i.e., the existence of a referent is implied for both nouns in the structure. These structures are a specific subtype of compounding, as illustrated in (1); title expressions, as shown in (2); and the -s possessive construction, as can be seen in (3).

| (1) | zon-s-hoogte |

| sun-s-height | |

| ‘solar altitude’ |

| (2) | professor Bolleboos |

| professor Bolleboos | |

| ‘professor Bolleboos’ |

| (3) | Marie-s hypothese |

| Mary-s hypothesis | |

| ‘Mary’s hypothesis’ |

It will be argued that for all these structures the non-head raises to a referential layer, i.e., a D-layer.

Compounds of the type zonshoogte ‘solar altitude’ are called referential compounds in the remainder of this article, which is short for compounds with a referential non-head. A previously unidentified type of compounds in Dutch is presented, i.e., compounds with referential non-heads, as illustrated in (1). They are argued to instantiate the logical combination in Borer’s (2011) classification that was assumed to be non-existent. Borer (2011), in a study of Hebrew noun–noun concatenations, can be interpreted as an overview with cross-linguistic validity. She argues that noun–noun concatenations show variation on the basis of two parameters.

The first one defines whether the concatenation forms a single word or a constituent. If a noun–noun concatenation is a single word, it forms a compound; otherwise, it is called a construct or construct state. It will be argued that this contrast also exists in Dutch. The structure in (1) is argued to be a compound. It is the only structure that involves incorporation, i.e., a movement operation that creates word-hood. The other two structures are constituents: the two nouns remain separate words in the structure. The compound in (1) contrasts with the title expression in (2), which will be argued to be a construct state. The -s possessive structure does not fall into compound–construct state opposition because it is a possessive structure, but it will become clear that it is relevant to compare referential compounding to this syntactic structure.

The second parameter in Borer’s work involves the semantics of the non-head, which could be referential or modificational. A referential non-head implies the existence of the non-head. It will thus be claimed that the syntax of zonshoogte ‘solar altitude’ in (1) is such that the existence of the referent, in this example the sun, is implied. This contrasts with modificational non-heads as in the English example wine glass or the Dutch example wijnglas ‘wine glass’, in which wine merely indicates the type of the glass. It thus modifies the meaning of the glass into a more specific meaning. The existence of wine in the context of discourse is not implied by the word wine glass. All Dutch structures in (1)–(3) are characterized by the referentiality of the non-head.

The notions head, non-head, referentiality, and modification are all defined in the next section in much more detail. Of importance at this point is that one expects four logical combinations within the domain of N–N concatenations: compounds with referential non-heads, compounds with modificational non-heads, constructs with referential non-heads, and constructs with modificational non-heads. Borer discusses three of these possibilities for Hebrew, and assumed that one logical possibility in the classification, namely, compounds with referential non-heads, is principally excluded and therefore non-existent. The discovery of a compounding type in Dutch with a referential non-head is in this sense important for the field’s understanding of what can occur in noun–noun concatenations. A more detailed background discussion is given in the next section.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the background literature on the construct–compound contrast and the contrast between modificational and referential non-heads. It clearly explains why the existence of referential noun–noun compounds is a relevant finding in the inventory of noun–noun concatenations known in the field. Section 3 contrasts the referential compound with other types of primary compounding in Dutch. Section 4 argues that the non-head of the referential compound indeed has referential properties. Section 5 shows that the referential compound is indeed a compound by contrasting the compound with the -s possessive. Section 6 presents a referential construct state in Dutch. Section 7 discusses the consequences of these data for our understanding of N-to-D movement. Section 8 concludes.

2. Background

This section defines the main concepts used in the article. More specifically, it defines compounds and constructs, heads and non-heads, and the referential and modificational nature of the non-heads. It then describes the discussion to which the present work contributes.

2.1. Compounds and Constructs and Heads and Non-Heads

Noun–noun concatenations can be compounds or constructs. Descriptively, compounds are defined in Lieber and Štekauer (2009). They adopt Bauer’s (2003, p. 40) definition according to which compounding is the formation of a new lexeme by adjoining two or more lexemes. A lexeme may be a word, root, or stem, depending on the language. English examples of compounds are kitchen towel and mountain lion.

Lieber and Štekauer (2009) point out that compounds are cross-linguistically characterized by specific phonological patterns, inseparability, and the fact that they are inflected as a unit. Compounds generally show specific phonological properties in languages. In Germanic languages, for example, compounds typically receive initial stress, i.e., stress which falls on the leftmost lexeme within the compound. Other languages may associate other specific phonological patterns to compounding, such as specific tonal patterns, vowel harmony, etc. Compounds further show syntactic inseparability. This means that compounds with an intervening modifier, such as *mountain wounded lion, would be illicit. Similarly, it would be illicit to front one part of the compound for focus marking, as in *Mountain it was a lion. Thirdly, they are inflected as a whole. For example, when pluralized, mountain lion only needs a single plural marker: mountain lions.

Theoretically, compounds are defined as structures that involve incorporation (Mithun 1984; Baker 1988; Harley 2009). Baker (1988, p. 1) defines incorporation processes ‘as processes by which one independent word comes to be “inside” another’. Within generative syntax, incorporation is technically performed by means of head movement: one head moves into the position occupied by another head, from which they continue to exist as if they were a single head together. It should come as no surprise that incorporation defines compounding: letting two (or more) lexemes exist in the structure as if they were one lexeme captures exactly what we observe in a compounding structure. It captures the inseparability and the fact that the compound is inflected as a whole. A compound also has the distribution of a single word. It is, for example, true that kitchen towel is more complex than towel, but nevertheless can have the exact same syntactic distribution as towel. It is also true that kitchen towel is psychologically experienced as one word, just like towel.

One lexeme within a compound will be dominant; this lexeme is called the head. In the syntactic trees in this paper, the notion head is also used to refer to the most atomic parts of the trees: individual morphemes are heads. Heads in this sense contrast with phrases, i.e., constituents in the tree. I regret the polysemy of the term head in this regard: for compounds and constructs, it refers to the dominant lexeme of the compound or the construct; within the tree it refers to morphemes.

The head of the compound will generally determine the meaning of the compound: a kitchen towel is a towel, a mountain lion is a lion, etc.1 We can thus conclude that towel is the head of kitchen towel and that lion is the head of mountain lion. The head will also receive the inflectional marking of the compound: the plural of kitchen towel would be kitchen towels and not *kitchens towel. The head will further determine the agreement patterns, if any. In Dutch, for example, the gender of the head noun will determine the gender of the definite article and adjectival agreement. In Germanic languages, the head of the compound is almost always the right-hand part of the compound (Williams 1981). The left-hand part is thus the compound’s non-head.

Nominal constructs or construct states are noun–noun concatenations that are characterized by a so-called abstract genitival relationship between the two nouns. That is to say, constructs are interpreted as if a genitival relation exists between the two nouns, although no overt genitival case is realized, and the construct does not contain a preposition either. An example from Hebrew is given in (4) (example taken from Siloni 1997, p. 21).

| (4) | beyt | ha-‘iš |

| house | the-man | |

| ‘the man’s house’ | ||

Constructs behave as prosodic units and they may show language-specific phonological properties. In the Hebrew example in (4), the noun bayit ‘house’ surfaces as the phonologically reduced form beyt due to the construct state, which causes a loss of stress for the head noun.

Constructs resemble compounds as both structures behave as a unit in the sentence and as both structures have a head, i.e., a dominant lexeme. In the example in (4), the head noun is beyt. The head noun determines the semantics of the unit. For this example, this means that the man’s house is a house, not a man.

Constructs differ from compounds as they show no evidence of incorporation. For Hebrew, the crucial evidence against incorporation was presented by Siloni (1997, p. 53). She pointed out that the non-head of the construct can be internally complex, involving a coordinate structure, modification, and complements, as in example (5) (example taken from Siloni (1997, p. 53), her example (63b)):

| (5) | beyt | [ha-rabi | mi-kiryat | ‘arba] | ve- | [ra‘ayat-o | ha-nixbada] |

| house | the-rabbi | from-Kiryat | Arba | and- | wife-his | the-honorable | |

| ‘the house of the rabbi of Kiryat Arba and his honorable wife’ | |||||||

In this example, the non-head is thus a phrase on its own. Nominal compounds are thus concatenations of two nouns, whereas constructs involve the concatenation of noun phrases. As expected, the nouns of these noun phrases thus do not behave as if they form a single word together. That means that the two nouns in the construct may show some degree of syntactic independence, separability, and independent inflection. How the separability and inflection manifest themselves exactly is a language-specific issue. I discuss relevant facts for Hebrew and Dutch in Section 5 in detail.

Technically, a construct can be understood as a noun phrase which hosts another noun phrase within its structure. It is usually assumed that the non-head occupies the specifier of some functional projection of the head, as illustrated in (6) (Ritter 1988, structure taken from Borer 2011, her examples (43) and (44)):

| (6) | [FP N | [… | [specifier | [NP Non-Head] | … [NP | ]]]] |

The structure in (6) can thus be read as a noun phrase in which another noun phrase is embedded.

In summary, noun–noun concatenations can be both compounds and constructs. Both structures contain a dominant lexeme, which is called the head. In compounds, the nouns become a single word through incorporation; in construct states, a noun phrase is embedded in a noun phrase. The construct thus shows more independence for its parts than the compound2.

2.2. Referentiality, Proper Names, and N-to-D Movement

Recall that the main claim is that noun–noun compounds may have referential non-heads. Having defined compounds and constructs, heads and non-heads, let us now turn to referentiality. Referentiality is defined by the entailment of existence (see Lyons 1999, Section 4.2 for a more complete and much more nuanced discussion). For example, Lyons (1999, p. 169) explains that in the sentence John met a stranger, the noun phrase a stranger is referential: it is implied that the stranger exists. When the existence of the referent is entailed, a pronoun can refer back to the referent. For example, in the sentence John met a stranger, he introduced himself as Carl Smith the pronoun he refers back to a stranger. In the sentence John didn’t meet a stranger, the noun phrase a stranger is not necessarily referential: there is a reading under which there was no such event in which John met a stranger; hence, the existence of the stranger is not implied.

The entailment of existence does not necessarily imply specificity. For example, as Lyons (1999, p. 171) points out, the sentence Smith’s murderer is insane implies that Smith was murdered and that a murderer exists.3 Due to the entailment of existence, a pronoun can refer back to the referent: Smith’s murderer is insane. He dismembered the body using an axe. The proposition does not imply specificity: it is not implied that the identity of the murderer is determined or specifically known to the hearer or listener.

Even though the entailment of existence does not imply the specificity or uniqueness in the context of the referent, the specificity of the referent will imply the existence. This is most notable for proper names, as can be concluded from example (8). In this example, a non-specific de dicto interpretation, which is illustrated in example (7), is not available.

| (7) | Marie | wil | met | een | prins | trouwen. |

| Marie | wants | with | a | prince | marry | |

| ✓ | ‘Marie has the wish to marry no matter which man, as long as he is a prince.’ (de dicto) | |||||

| ✓ | ‘Marie wants to marry a specific man and this man is a prince.’ (de re) | |||||

| (8) | Marie | wil | met | William | trouwen. |

| Marie | wants | with | William | marry | |

| * | ‘Marie has the wish to marry no matter which man, as long as he is called William.’ (de dicto) | ||||

| ✓ | ‘Marie wants to marry a specific man and this man is called William.’ (de re) | ||||

Proper names are typically interpreted as referring to a specific unique entity; this entity might be universally unique or unique in the discourse. In this example, William would be unique in the discourse, because there are, of course, many men in the world called William. Which William exactly the proper name William refers to depends on the context of discourse, universally unique entities are unique in our world. The planet Jupiter, the King of England, and France are all examples of unique entities. Their referents are not context-dependent.

The fact that proper names always have a specific de re interpretation results in the fact that the existence of the referent is implied4. There is thus a natural, typical connection between specificity and the entailment of existence. This connection is relevant in the present article. It will become clear that a referential interpretation of the non-head is available when its lexical semantics can imply (universally or contextually defined) specificity or even uniqueness.

Syntactically, a proper name is derived by means of a movement from the noun from its initial position as the head of the noun phrase to the determiner layer (Longobardi 1994). This movement expresses that the noun itself functions both as the noun and as the lexical item in the noun phrase that is responsible for the referentiality. In other words, it is simultaneously interpreted as a noun and as a determiner.

Longobardi (1994) justified this movement by discussing the Italian data in (9) (taken from his examples (28)). Examples (9)a–b are attested in Italian dialects; example (9)c is strongly ungrammatical in all dialects. What one observes in these examples is that the definite article il can be absent from the noun phrase if and only if the proper name Gianni precedes the possessive pronoun:

| (9) | a. | il | mio | Gianni | b. | Gianni | mio | c. | *mio | Gianni |

| the | my | Gianni | Gianni | my | my | Gianni | ||||

| ‘my Gianni’ | ‘my Gianni’ | ‘my Gianni’ | ||||||||

Interestingly, as can be seen in example (9)a, Italian is a language in which an article and a possessive pronoun can co-occur. It is assumed that the possessive pronoun merges in a projection called PossP (Possessor Phrase). The fact that in (9)b Gianni precedes the possessive pronoun, whereas it follows the possessive pronoun in (9)a, allows one to see that Gianni occupies a higher position in (9)b than in (9)a. This is illustrated in (10):

| (10) | a. | [DP | [D il | [PossP | [Poss | mio | [NP | [ N Gianni]]]]]] |

| b. | [DP | [D Gianni | [PossP | [Poss | mio | [NP | [ N |

These Italian data form the core argument for the view that proper name syntax is characterized by N-to-D movement. In English and Dutch, this movement empirically results in the absence of an additional determiner for proper names: the noun itself realizes the determiner layer; hence, no article or other determiner is needed.

Of course, it needs to be possible for a noun to receive the proper name interpretation once it has moved to D. Longobardi (1994) discusses the fact that empirical evidence for syntactic N-to-D movement for nouns goes hand in hand with belonging to specific lexical semantic fields. The movement is typically attested for proper names, kinship nouns, names of days and holidays, and unique entities. These nouns have the necessary semantic features to receive a uniquely referring interpretation. In summary, the proper name interpretation in (8) results in a specific interpretation. This interpretation is derived by the syntactic movement of the noun to the determiner layer, which makes the noun itself responsible for its referentiality. The movement is licensed by the lexical semantic of the noun, which makes the constituent interpretable. Notably, when stored lexical information is in conflict with the syntactic derivation, the semantics of the syntactic derivation will win. In the sentence Cat is coming, it will be assumed by the hearer that Cat is a proper name in the context (Borer 2005).

2.3. Referential Non-Heads for Constructs and Compounds?

Within generative grammar, the standard view is that referentiality is syntactically defined at the determiner layer (Longobardi 1994). As such, a syntactic structure will depend on the presence of such a layer for referentiality. Is it possible for the non-head of the construct and the compound to contain such a layer?

First consider constructs, because they constitute the simpler case. Recall that a construct can be understood as a noun phrase which hosts another noun phrase within its structure. Interestingly, the number of functional projections of the embedded noun phrase—this is the non-head—can differ, resulting in different semantic effects. More specifically, it may or may not involve a determiner layer, resulting in the noun phrase being referential or not. Example (11) shows a structure with a non-head which is a noun phrase without a determiner layer, which thus forms a NP, and which will thus be interpreted modificationally. Example (12) shows a structure with a non-head that does contain a determiner layer, which thus forms a DP. This non-head will be interpreted referentially (see Borer 2011, her examples (43) and (44)):

| (11) | [FP N | [… | [specifier | [NP Non-Head] | … [NP | ]]]] |

| (12) | [FP N | [… | [specifier | [DP Non-Head] | … [NP | ]]]] |

If the DP-layer is present, the non-head is introduced as a referent in the discourse, implying the existence of the referent and rendering it a possible antecedent for pronouns. This is the case for the man in example (13). If the determiner layer is absent, the non-head is interpreted modificationally, as in the example in (14) (example taken from Borer 2011, one of her examples in (23)). In the example in (14) the presence or existence of juice is not implied: what is implied is that the glass is of a specific type.

| (13) | beyt | ha-‘iš |

| house | the-man | |

| ‘the man’s house’ | ||

| (14) | kos | (ha-)mic |

| glass | (the-)juice | |

| ‘the juice glass’ | ||

The non-head of the construct can thus be either modificational or referential5.

Now consider again compounding structures. If we assume that noun–noun compounds involve the direct incorporation of a noun into a noun, we predict that the non-head of the compound always has modificational semantics. After all, there is no determiner layer to provide referentiality. As such, it should come as no surprise that non-heads of compounds are seen as modificational by definition. Referential non-heads for compounds are then excluded on principal grounds, as in Borer (2011), and a compound with a referential non-head could be seen as a contradiction in terminis.

This view on compounding contrasts with the extensive work on incorporation in Baker (1988, 1995, 1996). Above, we defined noun–noun compounding as structures in which a noun incorporates into a noun. Baker (1988) also discusses the incorporation of nouns into verbs6. For these incorporation types, he shows that, in some languages, non-heads may either be modificational or referential. Referential non-heads can serve as the antecedent of a following pronoun (Baker 1988, p. 79). Consider the example in (15) from the language Mapudungun from Baker (2009, his example (17))7, in which, indeed, a pronoun successfully refers back to a noun incorporated into a verb8:

| (15) | Juan | ngilla-pullka-la-y. | Iñche | ngilla-fi-ñ. |

| Juan | buy-wine-neg-ind.3sS9 | I | buy-3O-IND.1S | |

| ‘Juan didn’t buy the wine. I bought it.’ | ||||

Baker points out that the incorporated noun must have a definite interpretation because subsequent reference to it is not blocked by clausal negation. Recall that indefinite determiners under sentential negation do not necessarily imply referentiality, as in Lyon’s (1999) example John met a stranger, discussed above. Definite determiners necessarily imply referentiality, even under sentential negation: the sentence John did not meet the stranger implies the existence of the stranger due to the definiteness of the stranger. This is why the example in (15) must contain a definite determiner that guarantees the referentiality. Baker argues that the noun that incorporates into the verb was selected as an argument of the verb. This argument can contain a determiner layer, which could thus be referential.

The work on noun–verb incorporation shows that a referential non-head, i.e., a referential non-dominant lexeme within a compounding structure, is not excluded for incorporation structures at all if the noun to be incorporated can first merge with (and incorporate into) a definite determiner layer. This leads to the research question of whether referential non-heads for noun–noun compounds are indeed truly excluded. In this article, I present instances of Dutch compounds which are arguably relevant examples of compounds with referential non-heads: the noun of the non-dominant lexeme thus first incorporates into a syntactic head with referential properties, i.e., a determiner-like syntactic head before incorporating into the dominant lexeme of the compound.

Before we proceed, I would like to point out that the terminological opposition between modification and reference for compounding is perhaps not entirely accurate. It would perhaps be more correct to call the distinction between the two types of non-heads for the compounds referential versus non-referential, because they are always modificational. Modificational compounds, i.e., compounds with a non-referential non-head, achieve a semantic interpretation because features of the lexical semantics of the head and the non-head stand in coordinate, subordinate, or attributive relationships with one another (Scalise and Bisetto 2009, p. 48 building on Lieber 2004 and Bisetto and Scalise 2005). In coordinate compounds, lexical–semantic features of the head and non-head match one another. For the compound actor director, for example, the coordinate semantics (actor and director) are derived from the fact that various semantic features of the non-head and head match one another; for this example those features would be <human, professional>, <show business>, and <works in theatres, films, etc.>. For the compound apple cake, the subordinate relation (apple cake is a type of cake) is derived from the fact that at least one semantic feature of the non-head apple, viz. <can be an ingredient>, matches a semantic feature <made with ingredients> of the head cake. For attributive compounds, one feature of the non-head fulfils a feature of the head, and all other features are clearly irrelevant and are ignored. An example is the compound snail mail: the feature <very slow> of snail matches the feature <takes time> of mail (examples taken from Scalise and Bisetto 2009, pp. 48–49). These principles underlie the modificational semantics of compounding.

As far as I can tell, these principles still hold for the compounds with referential non-heads in this article. A compound such as verjaardagsfeest ‘birthday party’ is a subordinate compound in which the lexical semantic feature <cause for a festive event> of verjaardag ‘birthday’ is a match for the features <event> and <festive> of feest ‘party’. One might thus certainly still recognize the typical modificational semantics of compounding in a compound with a referential head. It is thus not true that compounds with a referential head cease to be modificational in this sense. They simply gain the extra semantic implication that the non-head is referential, i.e., that its existence is implied. This matches the proposal that will be presented in the article: the referential compounds contain one head more than the modificational compounds and may thus gain an extra semantic implication on top of the standard semantics of compounding. It would thus be more accurate to speak of referential and non-referential non-heads than of referential and modificational non-heads. However, given that the opposition reference versus modification has been established in the literature, I will continue to use these terms.

This paper starts from the theoretical assumption that morphology is syntax. The reader may have noted that Borer (2011) and Baker (2009) do not assume a separate module called morphology, which builds words. All morphosyntactic units are built in syntax in these proposals. It is the specific syntactic operation of incorporation, i.e., head movement, which yields compounds. Given that this paper is written in the framework of Distributed Morphology, this approach is adopted here: it is assumed that both constructs and compounds are built in the same structure-generating module called Syntax (Halle and Marantz 1993, 1994; Harley 2009). The adoption of this framework is not crucial to the understanding of the empirical argument that is made in this paper.

3. Referential Compounds versus Other Dutch Primary Compounding Types

As mentioned, this article argues that Dutch has noun–noun compounding of which the non-head is referential. These compounds are referred to here as referential compounds. However, this is far from the only type of primary compounding—compounding with non-phrasal non-heads—Dutch has. This section therefore briefly discusses an overview of the other types of Dutch primary compounds; thus, the referential compounding can be set apart from the other existing types.

De Belder (2017) and De Belder (to appear) identify two major Dutch primary compounding types: those of which the non-head is a bare root (De Belder 2017) and those for which the non-head merges with a classifier head (De Belder to appear). The non-head of the bare root compound can be associated with any category and never merges with an overt ‘linking element’, as can be seen in (16) (examples taken from De Belder 2017, p. 141):

| (16) | a. | speur-hond | b. | drie-luik | c. | snel-trein | d. | achter-grond |

| track-dog | three-panel | fast-train | back-ground | |||||

| ‘tracking dog’ | ‘triptych’ | ‘high-speed train’ | ‘background’ |

De Belder argues that the non-head of these compounds is a bare root, i.e., a lexeme not specified for a specific category. Given that the non-head of these compounds is thus not a noun, these compounds do not instantiate noun–noun concatenations. They are mentioned here for good measure because they are relevant to understand the empirical landscape of compounding in Dutch, but they do not help us to understand the possibilities within the domain of noun–noun concatenations. It is worth mentioning, however, that this type of compounding instantiates incorporation with a modificational non-head. It is thus relevant to the broader contrast between referential and modificational non-heads in incorporations, as was also found by Baker for noun–verb incorporations, as described in the previous section.

De Belder (to appear) argues that the non-head of the classifier type, in contrast, merges with a nominal classifying projection. It thus invariably receives a nominal interpretation and, clearly, the non-head is a noun. This type of compounding is thus a true instantiation of a noun–noun concatenation. This type is perhaps the Dutch counterpart of what Borer (2011) identified as genuine compounding in Hebrew. It is thus a compound with a modificational non-head. The type is easily recognized by the presence of a so-called linking element -s- or -en-, as illustrated in (17) (NCM = nominal compound marker, i.e., the “linking element”, examples taken from De Belder 2017, p. 140):

| (17) | a. | peer-en-boom | b. | varken-s-hok |

| pear-ncm-tree | pig-ncm-pen | |||

| ‘pear tree’ | ‘pig’s pen’ |

De Belder (to appear) argues that this ‘linking element’ realizes the functional head of nominal classification10. Furthermore, it is pointed out there that nominal classifying heads can in principle be realized by null morphemes as well, and that there is actually dialectal evidence that this indeed happens in Dutch, probably also in the standard language. The reasoning is rather complex and lengthy, so I refrain from summarizing it here as it would take us too far afield. According to the reasoning described there, the compounds in (18) could be relevant examples for compounds with nominal classifying heads realized by null morphemes.

| (18) | a. | siroop-fles | b. | klei-grond | c. | wol-draad |

| syrup-bottle | clay-soil | wool-yarn | ||||

| ‘syrup bottle’ | ‘clay soil’ | ‘wool-yarn’ |

De Belder (to appear) argues that, as a result, the classifier head in Dutch can be realized by means of ∅, -s- [s] or -en- [ǝ(n)]. Compounds of this type with a null marker are, at the surface, of course indistinguishable from compounds with a bare root as their non-head.

De Belder (to appear) discusses the well-known fact that the non-head of the classifying (i.e., modificational) compounding type selects the classifier head and its exponent. It is argued there that one can thus expect a quite regular selection between the non-head’s lexeme and its classifying exponent of choice (∅, -s- or -en-), as illustrated in (19)–(20) (see Botha (1968) and see De Belder (to appear) for a more nuanced discussion. Example (19) is taken from De Belder (to appear), her example (7)11):

| (19) | a. | kat-en-luik | b. | kat-en-voer | c. | kat-en-staart | d. | kat-en-bak |

| cat-ncm-shutter | cat-ncm-food | cat-ncm-tail | cat-ncm-box | |||||

| ‘cat flap’ | ‘cat food’ | ‘cat tail’ | ‘cat litter box’ |

| (20) | a. | ezel-s-dracht | b. | ezel-s-bruggetje |

| donkey-ncm-pregnancy | donkey-ncm-bridge.diminutive | |||

| ‘long pregnancy’ | ‘mnemonic’ | |||

| c. | ezel-s-oor | |||

| donkey-ncm-ear | ||||

| ‘dog-ear’ |

The present article, however, draws attention to the fact that sometimes non-heads occur with an -s-, even though they would typically be restricted to bare root compounding or select zero marking or -en-12 as a compounds with a nominal classifying head. I argue that when these non-heads are bare roots or when they select their typical exponent of the classifying head (here zero or -en-), they are modificational compounds; if they select the unexpected -s-, they are referential compounds. This results in the following inventory for Dutch compounds (see Table 1):

Table 1.

An inventory of Dutch primary compounding.

These three types are illustrated in the examples in (21):

| (21) | a. | kreeft-woord | b. | kreeft-en-soep | c. | Kreeft-s-keerkring |

| lobster-word | lobster-en-soup | lobster-s-tropic | ||||

| ‘palindrome’ | ‘lobster soup’ | ‘Tropic of Cancer’ | ||||

| [bare root c.] | [noun class marking c.] | [referential compound] |

Thus, referential compounds can be recognized by the appearance of an -s- where it is not immediately expected. This type has previously remained undetected in Dutch, as it was simply assumed these compounds were instances of modificational compounds with a linking element. I now discuss this in some more detail. De Belder (to appear) argues that non-heads with the semantics of kinship names and proper names, as in (22), are probably always bare root compounds:

| (22) | a. | moeder-melk | b. | moeder-taal | c. | vader-beeld |

| mother-milk | mother-language | father-image | ||||

| ‘breast milk’ | ‘mother tongue’ | ‘conception of the father figure’ | ||||

| d. | Pieter-baas | e. | Pieter-man | |||

| Peter-boss | Peter-man | |||||

| ‘black Pete’ | ‘ancient coin with the image of Saint-Peter/ | |||||

| name of a certain fish (Trachinus draco)’ | ||||||

However, as shown in (23), one does find instances of kinship names and proper names followed by an -s- in Dutch compounding:

| (23) | a. | moeder-s-kind | b. | vader-s-zijde |

| mother-s-child | father-s-side | |||

| ‘child too dependent on the mother’ | ‘father’s side of the family’ | |||

| c. | Pieter-s-zoon | |||

| Peter-s-son | ||||

| (family name) |

It is claimed in the following sections that these compounds are referential compounds.

Similarly, the Dutch roots dag ‘day’ and jaar ‘year’ typically do not select a ‘linking element’, as can be seen in (24), either because they invariably occur in bare root compounding or because they are instances of noun class marking compounds which select a zero exponent of noun class marking (I am principally unable to tell):

| (24) | a. | dag-deel | b. | jaar-beurs | c. | jaar-balans | d. | jaar-getijde |

| day-part | year-fair | year-balance.sheet | year-tide | |||||

| ‘part of the day’ | ‘trade fair’ | ‘annual balance sheet’ | ‘season’ |

However, again, one does find instances of exactly these roots selecting an -s-, as can be seen in (25):

| (25) | a. | verjaardag-s-taart | b. | nieuwjaar-s-feest |

| birthday-s-pie | new.year-s-party | |||

| ‘birthday pie’ | ‘New Year’s party’ | |||

| c. | zondag-s-kind | |||

| Sunday-s-child | ||||

| ‘child born on a Sunday and born for good luck’ | ||||

Again, the claim will be that they are referential compounds.

Then, there are noun class marking compounds of which the non-head selects -en- to realize the noun class marking, as in (36):

| (26) | a. | zon-en-bank13 | b. | kreeft-en-soep |

| sun-en-bench | lobster-en-soup | |||

| ‘tanning bed’ | ‘lobster soup’ | |||

| c. | naam-en-lijst | d. | maan-en-stelsel | |

| name-en-list | moon-en-system | |||

| ‘list of names’ | ‘moon system’ |

However, again, one does find instances of these roots selecting an -s-, as shown in (27), for which it will be claimed that they are instances of referential compounding:

| (27) | a. | zon-s-hoogte | b. | Kreeft-s-keerkring |

| sun-s-height | Cancer-s-tropic | |||

| ‘solar altitude’ | ‘Cancer Tropic’ | |||

| c. | naam-s-wijziging | d. | maan-s-verduistering | |

| name-s-change | moon-s-eclipse | |||

| ‘name change’ | ‘lunar eclipse’ |

In summary, there seems to be a type of compounding in Dutch, which is characterized by the occurrence of an -s- as its linking element. To be entirely clear, it is not claimed here that all instances of Dutch compounds with an -s- are referential compounds. As can be deduced from Table 1, the -s- can be a realization of a nominal classifying head as well.14 Notably, it is thus probably so that there are compounds which select both the -s- as modificational compounds and as referential compounds.15

4. The Referentiality of the Non-Head

As became clear in Section 2, the issue at stake in this article is the existence of compounds in Dutch which have a referential non-head. Referentiality was defined in Section 2: it means that the existence of a referent is implied. In the present section, arguments are presented in favor of the referentiality of the non-head; the next section presents arguments in favor of the compounding status.

Consider the following four arguments for the referentiality of the non-head. First, the non-heads that occur in the referential compounds seem to belong to a specific group; they are highly reminiscent of the type of lexemes Longobardi (1994) identified as typically subject to proper name syntax and semantics: proper names (Pieter ‘Pete’), kinship names (moeder ‘mother’, vader ‘vader’), names of days of the weeks (zondag ‘Sunday’) and holidays (Nieuwjaar ‘New Year’, verjaardag ‘birthday’), and unique entities (zon ‘sun’, Kreeft ‘Cancer (the constellation)’, maan ‘moon’). Longobardi (1994) derives the proper name semantics and syntax via movement of the noun to the determiner layer (N-to-D raising). This expresses that it is the noun itself that has the referential properties, rather than relying on an article or other determiner in the structure. Of course, if the noun itself receives the semantics of expressing specific referentiality, something in the noun needs to be able to express these semantics. For this reason, the particular type of proper name syntax is only attested for nouns that belong to specific semantic fields: these nouns carry the specific reference within their lexical semantics. The specific reference itself is derived through the syntactic movement to the determiner layer; however, it is licensed by the specific lexical semantics that make this movement interpretable. For the compounds under discussion, the first ingredient to become referential is thus in place: these lexemes are excellent candidates to raise to a D-layer syntactically where they can gain referential semantics.

Secondly, the referential compounding seems to imply universal uniqueness or uniqueness in the discourse context. For example, Kreeftskeerkring ‘Tropic of Cancer’ uniquely refers to the Cancer constellation. This contrasts with a modificational compound such as kreeftensoep ‘lobster soup’, which does not show the -s- and which does not imply unique reference to a lobster at all. In fact, it does not even imply the presence of lobster: one can easily find a recipe for kreeftensoep zonder kreeft ‘lobster soup without lobster’ on Google. Similarly, manenstelsel ‘moon system’ does not refer to the Earth’s unique moon, whereas maansverduistering ‘lunar eclipse’ does refer to the unique moon as we know it. For words such as naam ‘name’, vader ‘father’, zondag ‘Sunday’, and verjaardag ‘birthday’, the uniqueness is contextual rather than universal. This does not constitute a problem: it is known from research on definiteness that contextual uniqueness suffices for referentiality (Lyons 1999). The unique and specific reference implies the existence of the referent. As such, unique referentiality implies referentiality.

Thirdly, in the absence of uniqueness, the referential compound is excluded, as illustrated by the following minimal pair (28) and (29):

| (28) | zon-s-hoogte |

| sun-s-height | |

| ‘solar altitude’ |

| (29) | *ster-s-hoogte |

| star-s-height |

Admittedly, as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, it is unclear at this point whether referential compounding is a productive process in present-day Dutch. I suspect it is not and, as such, it may be independently predicted that a neologism such as *stershoogte is illicit. More generally, the use of present-day judgements may be a flawed methodology for the dataset under discussion. It is perhaps more insightful to consult corpora to determine which compounds exist. The following point illustrates this: a reviewer points out that they would not accept Poolstershoogte ‘Northstarheight’ either, a judgement with which I would agree. Interestingly, however, Poolstershoogte ‘Northstarheight’ is attested in navigational handbooks, as expected (e.g., Swart 1841, p. 119; Begemann 1842, p. 409; Hondeijker 1853, p. 121)16.

Fourthly, not only the uniqueness, but the referentiality itself is implied. Compare the following contrast. The following fully acceptable dialogue in (30) illustrates the classical, familiar non-referentiality of the non-head of a modificational compound (hondenmand ‘dog bed’):

| (30) | A: We kopen een hondenmand. |

| B: Oh, heb jij een hond? | |

| A: Nee, eigenlijk niet, we gaan de mand gebruiken voor onze kat. | |

| B: Ja, je hebt gelijk, dan ligt ze wat ruimer. | |

| ‘A: We are buying a dog bed. | |

| B: Oh, do you have a dog? | |

| A: No, actually not, we are going to use the bed for our cat. | |

| B: Yes, I see, it will be a bit more spacious for her then.’ |

For the referential compound verjaardagsfeest in example (31), however, a dialogue parallel to the one in (30) is excluded—or at least very odd—due to the fact that the existence of the birthday is actually implied:

| (31) | #A: We organiseren een verjaardagsfeest. |

| B: Oh, is er een verjaardag? | |

| A: Nee, eigenlijk niet, we organiseren het feest voor een huwelijk. | |

| B: Ja, je hebt gelijk, dat is vast goedkoper. | |

| ‘A: We are organising a birthday party. | |

| B: Oh, is there a birthday? | |

| A: No, actually not, we are organising the party for a wedding. | |

| B: Yes, I see, it’s probably cheaper.’ |

Fifthly, as an anonymous reviewer points out17, pronouns referring back to the compound’s non-head are much more acceptable for referential compounds, as illustrated in (32), than for modificational compounds, as shown in (33) (see Baker 1995, 1996, and 2009, and see Section 2 on referentiality).

| (32) | ? De | zoni-s-hoogte | is | opvallend | deze | ochtend, | ook | al is hiji18 nog maar net op. |

| the | sun-s-height | is | striking | this | morning, | even | if is heonly prt just up | |

| ‘The height of the sun is striking this morning, even if it (i.e., the sun) has only just gone up.’ | ||||||||

| (33) | *Dat zoni-en-stelsel is enorm, | ook | al | is hiji | relatief | dichtbij. |

| That sun-en-system is huge | even | if | is he | relatively | close | |

| Intended: ‘That solar system is huge, even if the sun is relatively close.’ | ||||||

I conclude that the non-heads of these compounds have unique reference. The consequence is that the long-held belief that the non-head of a compound is, by definition, non-referential may be falsified.

5. Referential Compounds versus the -s- Possessive Construction

The present section argues that the referential compound has true compounding status (and, as such, word-hood status) by comparing it to a phrase with similar properties: the Dutch -s possessive construction (see also De Belder 2009).19 It will become clear that the Dutch -s possessive construction is a constituent with properties similar to referential compounds: they both have a left-hand part that is restricted to proper names, and in both structures, an -s- realizes a determiner head.

The Dutch -s possessive resembles the English saxon genitive, but it is more restricted. In Dutch, the -s possessive construction is restricted to kinship nouns and proper names. Hence, the examples in (34) are excluded, whereas the ones in (35) are fine.

| (34) | a. | *gisteren-s | arrangementen | b. | *vrouw-s | theorie | ||

| yesterday-s | arrangements | woman-s | theory | |||||

| c. | *een | vrouw-s | theorie | d. | *de | vrouw-s | theorie20 | |

| a | woman-S | theory | the | woman-S | theory | |||

| (35) | a. | Marie-s | hypothese | b. | papa-s | auto |

| Mary-S | hypothesis | daddy-S | car | |||

| ‘Mary’s | hypothesis’ | ‘daddy’s | car’ |

When one studies the data in somewhat more detail, the generalization is that, in the Dutch -s possessive construction, only those nouns can occur as the possessor for which we know that they can occur without a determiner in argument position and for which we thus reasonably assume that they can undergo N-to-D raising in argument position following Longobardi’s (1994) analysis. Kinship nouns and proper names are of course roots that have the appropriate semantics to undergo N-to-D raising. In other words, their lexical semantics is such that they can be interpreted as referring to a unique entity (i.e., they can be interpreted as a proper name) and, accordingly, they can behave syntactically as proper names. The syntax of proper names has been argued to involve N-to-D raising: the nouns can occur without an overt determiner in argument position, because the root itself has raised to D. The determiner layer serves to introduce the referentiality of the noun phrase, nouns which entail a unique reference semantically can therefore raise to the determiner layer themselves. They realize both the noun and the determiner function simultaneously, so to speak (Longobardi 1994 and see Section 5 below for an illustration of the specific lexical semantics of proper names). It follows from Longobardi’s proposal that the proper name Marie in example (36)a and the kinship noun papa in example (36)b surface without a determiner: the nouns themselves occupy the determiner layer.

| (36) | a | Ik | ontmoette | Marie | in | Parijs. | b. | Ik | zag | papa. |

| I | met | Mary | in | Paris. | I | saw | daddy’. | |||

| ‘I met Mary in Paris.’ | ‘I saw daddy’. | |||||||||

If the noun cannot undergo N-to-D raising in argument position, the -s possessive construction is excluded. The contrast between the examples (37) and (38) shows that the noun (i.e., the root in the structurally nominal position) zon ‘sun’ requires an overt determiner in Dutch in argument position. It thus cannot achieve true proper name syntax, as Marie in (36)a, papa in (36)b, and the celestial body Venus in (39). Example (40) shows that the noun cannot occur as the possessor in the -s possessive construction. The proper names of rivers, an example of which is given in (42), illustrate the same fact. They cannot occur without an overt determiner, as shown in (42), and they do not occur as the possessor in the -s possessive either, as shown in (43) (see Section 6 for an account):

| (37) | Ik | zie | de | zon. |

| I | see | the | sun | |

| ‘I see the sun.’ | ||||

| (38) | #Ik | zie | zon.21 |

| I | see | sun |

| (39) | Ik | zie | Venus. |

| I | see | Venus | |

| ‘I see Venus.’ | |||

| (40) | *zon-s | zachte | warmte |

| sun-S | gentle | warmth |

| (41) | Ik | zie | de | Seine. |

| I | see | the | Seine | |

| ‘I see the Seine’ | ||||

| (42) | *Ik | zie | Seine. |

| I | see | Seine |

| (43) | *Seine-s | flikkerende | spiegeling |

| Seine-s | flickering | reflection |

The -s possessive construction and the referential compound show resemblances. Their non-heads are referential, and they are both marked by an -s. However, they also show significant empirical differences, showing that we are dealing with two distinct structures.

Consider the following four criteria that distinguish between the two structures. First, consider the restriction that only non-heads which can undergo N-to-D movement when occurring in argument position can occur as the possessor in -s possessive constructions. A parallel restriction does not hold for referential compounds. The referential compound allows all roots as a non-head that have a unique—albeit universal or contextual—reference. The illicit -s possessive construction in (40) thus contrasts with the licit referential compound in (44):

| (44) | zon-s-verduistering |

| sun-s-eclipse | |

| ‘solar eclipse’ |

I postpone an account for this contrast until Section 6. For now, it is important to note that the contrast exists as a criterion to distinguish between the two structures.

Secondly, the compounds qualify for word-hood in the sense that they can be lexicalized: they are stored in the native speaker’s memory and in Dutch dictionaries. In that sense, a native speaker can distinguish between stored compounds, perhaps even with an idiomatic meaning, as shown in (45), and newly formed compounds, i.e., neologisms, which are to be interpreted literally, as illustrated in the examples in (46) and (47):

| (45) | Ze | is | een | zondag-s-kind. |

| she | is | a | Sunday-s-child | |

| ‘She is born on a Sunday and thus for good luck.’ | ||||

| (46) | #Ze | is | een | maandagskind. |

| she | is | a | Monday-s-child | |

| (The speaker expresses that there is a salient connection in the discourse between the child and Mondays.) | ||||

| (47) | Ze | is | een | vrijdag-s-oma. |

| she | is | a | Friday-s-grandmother | |

| (The speaker expresses that there is a salient connection in the discourse between the grandmother and Fridays, for example, because this grandmother only visits the family on Fridays.) | ||||

I do not fully exclude a creative, humorous use of the neologism in (46), analogue to the idiomatic reading in (45) (i.e., a child that systematically fails to grasp good luck). However, the mere fact that it would be considered humorous illustrates the point that it is not lexicalized. The -s possessive construction does not qualify for word-hood in that sense: it is simply a freely generated syntactic constituent. Syntactic constituents are never experienced as ‘neologisms’, as illustrated in (48):

| (48) | moeders auto/fiets/jurk/laptop/… |

| mother’s car/bicycle/dress/laptop/… |

Thirdly, the compounds qualify for word-hood phonologically: they receive compound stress, i.e., main stress falls on the non-head, as shown in (49). The -s possessive construction, in contrast, receives the stress of a syntactic constituent, as can be seen in (50):

| (49) | a. | 'moeder-s-kind | b. | 'Kreeft-s-keerkring |

| mother-s-child | Cancer-s-tropic | |||

| ‘child too dependent on the mother’ | ‘Cancer Tropic’ |

| (50) | a. | moeder-s ’auto | b. | Marie-s | ’feestje |

| mother-S car | Mary-S | party | |||

| ‘mother’s car’ | ‘Mary’s party’ |

Fourthly, a compound, in (52), qualifies for word-hood in the sense that it cannot be interrupted by other words: an intervening adjective is excluded, as can be seen in (53). The -s possessive construction in (51), in contrast, allows for intervening adjectives:

| (51) | moeders | mooie | autootje |

| mother’s | pretty | car.DIMINUTIVE | |

| ‘mother’s pretty little car’ | |||

| (52) | Ze | was | mijn | grootmoeder | van | vader-s-zijde. |

| she | was | my | grandmother | of | father-s-side | |

| ‘She was the grandmother of my father’s side of the family.’ | ||||||

| (53) | *Ze | was | mijn | grootmoeder | van | [vader-s] arme [-zijde].22 |

| she | was | my | grandmother | of | father-s-poor-side |

I conclude that the referential compound differs from the -s possessive construction. The referential compound qualifies for word-hood and is thus truly a compound. Syntactically, this implies that it is derived through head incorporation, as shown in the tree below (54)a, which counts as the syntactic movement that defines word-hood for compounds (Mithun 1984; Harley 2009).

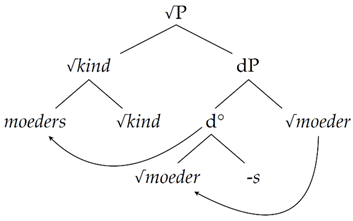

Within Distributed Morphology, the framework adopted in this article, it is usually assumed that semantic properties are derived from syntactic heads. If one thus accepts the claim in Section 4 that the non-head of the compounds under discussion is referential, this semantic property should be derived from a syntactic head. I therefore propose that the non-head incorporates into a functional head called little d°, which is characterized by nominality and uniqueness: [n, unique]. It surfaces as -s-. The compound’s non-head incorporates into the head little d°. The non-head plus -s- subsequently incorporates into the head of the compound.

The structure of this compound differs from the more general structure of compounding in Distributed Morphology by containing the d°-layer. Noun–noun compounds of which the non-head would not receive a referential interpretation, i.e., modificational compounds such as juice glass, would involve a direct incorporation of the noun into a noun. Referential compounds are thus not different from modificational compounds in general; they simply contain one functional layer more. This connects back to the discussion in Section 2 that referential compounds can still be interpreted modificationally: they contain all semantics of modificational compounds, and they simply contain one semantic aspect on top of it, which is the implication of existence of the non-head, derived by the movement to little d°.

The -s possessive construction, as in the tree below (54)b, in contrast, would not undergo head incorporation. The non-head rather moves to Spec,DP and the -s occupies the D° position. It moved there from its base position, which could either be analyzed as Spec,nP or Spec,PossP. (See Abney 1987 on the Spec,DP position for the possessor and see Alexiadou et al. 2007, p. 568 for the base position in Spec,nP for possessors. Corver 1990 proposes the -s ends in the D° head.) I adopt here the idea that the possessor starts in PossP on semantic grounds. PossP would be the position in the tree that is responsible to establish the semantic relation of possession. It would also be the base position for possessive pronouns, for example. From there, it moves to the D-layer, where it receives its referential semantics. This derivation is compatible with the more general idea that semantic components match several functional layers in the tree.

| (54) | a. | moeder-s-kind | b. | moeder-s auto |

| mother-s-child | mother-s car | |||

| ‘child too dependent on the mother’ | ‘mother’s car’ | |||

|  |

The structures of the -s possessive and the referential compound thus clearly differ in the sense that the compound involves incorporation, whereas the possessive construction is a noun phrase in which another noun phrase is embedded. However, these structures also show significant similarities. They both involve the noun-to-determiner raising that defines the syntax and semantics of the proper name and they both involve an [s] that realizes a determiner head.

6. The Referential Construct State

In this section, I argue that referential construct states also occur in Dutch: they are title expressions (see also De Belder 2009).

Title expressions are illustrated in (55)–(56). They always consist of one or more bare common nouns followed by a proper name.

| (55) | graaf | Dracula |

| count | Dracula | |

| ‘count Dracula’ | ||

| (56) | professor | doctor | Einstein |

| professor | doctor | Einstein | |

| ‘professor doctor Einstein’ | |||

The order cannot be changed, in the sense that the bare common noun needs to precede the proper name, as shown in (57):

| (57) | *Dracula | graaf |

| Dracula | count |

The construction needs to contain at least one proper name, as illustrated in (58):

| (58) | *koningin | paleis |

| queen | palace |

Proper names have specific lexical semantics, and title expressions as a whole function semantically as a proper name. This can be deduced from the following two tests. First, Dutch definite NPs allow for a generic reading, as shown in (59), except when they are proper names, as in (60). As can be seen in (61), title expressions exhibit patterns with proper names in this respect.

| (59) | De | hond | is | een | trouw | dier. |

| the | dog | is | a | loyal | animal | |

| ✓ | generic reading: ‘Every dog is a loyal animal.’ | |||||

| (60) | Albert | is | een | flamboyante | man. |

| Albert | is | a | flamboyant | man | |

| *generic reading: ‘Every Albert is a flamboyant man.’ | |||||

| (61) | Prins | Albert | is | een | flamboyante | man. |

| Prince | Albert | is | a | flamboyant | man | |

| *generic reading: ‘Every prince Albert is a flamboyant man.’ | ||||||

Secondly, the title expression exhibit patterns with the proper names as it only allows for a de re reading, as illustrated in (62) and (63) (and see Section 2 for discussion).

| (62) | Marie | wil | met | William | trouwen. |

| Marie | wants | with | William | marry | |

| * | ‘Marie has the wish to marry no matter which man, as long as he is called William.’ (de dicto) | ||||

| ✓ | ‘Marie wants to marry a specific man and this man is called William.’ (de re) | ||||

| (63) | Marie | wil | met | prins | William | trouwen. |

| Marie | wants | with | prince | William | marry | |

| * | ‘Marie has the wish to marry any man, as long as this man is called prince William.’ (de dicto) | |||||

| ✓ | ‘Marie wants to marry a specific man and this man is prince William.’ (de re) | |||||

I conclude that title expressions are DPs which consist of one or more bare common nouns followed by a proper name and the whole functions semantically as a proper name.

One could think that the bare common noun needs to belong to a specific semantic field because it commonly refers to nobility, as in example (64), clergy, as in (65), military ranks, as in (66) or professions, as in (67).

| (64) | prins | Charles |

| prince | Charles | |

| ‘prince Charles’ | ||

| (65) | priester | Damiaan |

| priest | Damian | |

| ‘father Damian’ | ||

| (66) | kapitein | Von Trapp |

| captain | Von Trapp | |

| ‘captain Von Trapp’ | ||

| (67) | professor | Curie |

| professor | Curie | |

| ‘professor Curie’ | ||

This could suggest that nouns referring to nobility, clergy, military ranks, or professions form a closed class in the lexicon which, for example, share a feature [+ title] or [+unique reference] or lexical productively. Indeed, any common noun is licit as the bare common noun in the title expression, as can be concluded from the examples in (68)–(70) 23:

| (68) | kabouter | Plop |

| gnome | Plop | |

| ‘gnome Plop’ | ||

| (69) | Vos Reinaert | |

| fox Reinaert | ||

| ‘fox Reinaert’ | ||

| (70) | boekenkast | Billy |

| book case | Billy | |

| ‘book case Billy’ | ||

Even nonce formations can occur as the bare common noun in the title expression, as illustrated in (71):

| (71) | naakstrandgemeente | Bredene |

| nude.beach.town | Bredene | |

| ‘Bredene, the town that has a nude beach’ | ||

Note that the ‘proper name’ does not need to be stored as a proper name either: the title expression is interpretable, regardless which roots realize the syntactic positions, as illustrated in example (72) (cf. Borer 2005):

| (72) | bedsofa | Vimle |

| bed.couch | Vimle | |

| ‘bed couch Vimle’ | ||

This shows that the title expression does not depend on a specific property of the lexical items involved. Structural properties license them. This raises the questions of which syntactic structure is realized by the title expression and why the whole functions as a proper name. I propose that the bare common noun is licensed by N°-to-D° movement in a construct state (see also De Belder 2009). The title interpretation is a result of this syntactic structure, which I present in more detail at the end of this section.

In Section 2, the construct state was introduced. Recall that in Hebrew, a construct state, as shown in example (73), is a DP which consists of a bare, unstressed head noun which is immediately followed by a genitival phrase that is not overtly case-marked. A variety of semantic relations can hold between them. (Cf. Borer 1984; Ritter 1991; Siloni 1997)

| (73) | beyt | ha-‘is | [Hebrew examples are taken from Siloni (1997; pp. 21–26)] |

| house | the-man | ||

| ‘the man’s house’ | |||

Title expressions and the Hebrew construct state share structural similarities. First, in both constructions, as illustrated in (74)–(75), prepositions cannot intervene between the head and the complement:

| (74) | beyt | (*sel) | ha-‘is | [Hebrew] |

| house | of | the-man |

| (75) | professor (*van) | Einstein | [Dutch] |

| professor of | Einstein |

Secondly, in both constructions an initial determiner is illicit. This is immediately clear for Hebrew, as illustrated in (76):

| (76) | (*ha)-beyt | ha-‘is | [Hebrew] |

| the-house | the-man |

For Dutch title expressions, we first need a context in which a construction with a proper name would tolerate a determiner in the first place. Such examples exist: definite determiners may merge with proper names referring to males in Belgian Dutch, as in examples (77) and (78).

| (77) | Ik | heb | de | Larousse | gezien. | [Belgian Dutch] |

| I | have | the | Larousse | seen | ||

| ‘I have seen Larousse.’ (Larousse is a family name.) | ||||||

| (78) | Ik | heb | de | Jan | gezien. | [Belgian Dutch] |

| I | have | the | John | seen | ||

| ‘I have seen John.’ | ||||||

However, in the title expression such an initial determiner is excluded, as shown in example (79), on a par with the Hebrew construct state in (76).

| (79) | *Ik | heb | de | professor | Larousse | gezien. | [Belgian Dutch] |

| I | have | the | professor | Larousse | seen |

Thirdly, in both constructions, the whole DP inherits the referential properties of the second part. This is shown in examples (80)–(81) for Hebrew: the (in)definiteness of the second part of the construct state determines the (in)definiteness of the whole construct state:

| (80) | ben | ha-melex | [Hebrew] |

| son | definite-king | (example taken from Borer 1984, p. 45) | |

| ‘the prince’ | |||

| (81) | Ben | melex | [Hebrew] |

| son | king | (example taken from Borer 1984, p. 45) | |

| ‘a prince’ | |||

For Dutch, we have seen that the entire title expression inherits the referential properties of the second part: the whole expression functions semantically as a proper name, as they resist a generic reading and a de dicto reading.

Fourthly, both structures are recursive, this is illustrated in example (82) for Hebrew and in (83) for Dutch:

| (82) | gag | beyt | ha-‘is | [Hebrew] |

| roof | house | the-man | ||

| ‘the roof of the house of the man’ | ||||

| (83) | ingenieur | doctor | doctor | professor | ererector | [Dutch] |

| engineer | doctor | doctor | professor | honorary. president | ||

| associatievoorzitter | baron | Oosterlinck | ||||

| association.president | baron | Oosterlinck | ||||

| ‘engineer doctor doctor professor honorary president association president baron Oosterlinck’ | ||||||

Fifthly, for both constructions, the presence of the complement is obligatory, as can be seen in the examples (84)–(87):

| (84) | beyt | ha-‘is | [Hebrew] |

| house | the-man | ||

| ‘the man’s house’ | |||

| (85) | *beyt | [Hebrew] |

| house |

| (86) | Ik | heb | paus | Benedictus | gezien. | [Dutch] |

| I | have | pope | Benedict | seen | ||

| ‘I have seen pope Benedict.’ | ||||||

| (87) | *Ik | heb | paus | gezien. | [Dutch] |

| I | have | pope | seen |

Sixthly, in both constructions, the head noun is de-stressed, as shown in (88)–(90).

| (88) | *bayit | ha-‘is | [Hebrew] |

| house | the-man | ||

| (bayit is the stressed form of the unstressed beyt) | |||

| (89) | *koning’in | Fabiola | [Dutch] |

| queen | Fabiola |

| (90) | koningin | Ma’thilde | [Dutch] |

| queen | Mathilde | ||

| ‘queen Mathilde’ | |||

Note that this stress pattern clearly sets apart the title expression from a compound, because compounding stress would entail stress on the left-hand part in Dutch.

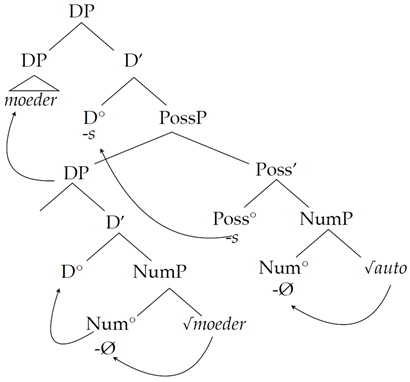

Given the fact that the second part of the construction functions as a proper name24, I assume that it undergoes N-to-D raising (Longobardi 1994), and as such acquires the referential properties of the proper name. Given the empirical similarities of the title expression to the construct state in Ritter (1991), I analyze it further on a par with Ritter’s (1991) analysis for the Hebrew construct state in the tree below example (91).

Ritter (1991) argued that the noun phrase contains functional projections, such as a Number layer and a Determiner layer, a proposal which became a standard assumption in the field. She argued that in the construct, the non-head merges in the specifier of the head noun. The functional positions are landing places for the head of the construct: by means of head movement of the noun to Number, the head acquires number; by moving the head to the determiner layer, it acquires referential meaning. This proposal is illustrated in the tree below.

In the Dutch tree below (92), the functional projections Gender, Number, and Determiner are assumed, because Dutch nouns carry gender—which is visible via gender agreement in the noun phrase—singular or plural numbers and may contain determiners. The head noun (here, professor) first moves into Gender and then into Number. This movement expresses that the head noun forms a single word with the Gender and Number projection, because head movement defines word-hood. It then moves into the determiner layer, expressing that the noun itself becomes referential. This movement thus defines proper name semantics for the head noun. The non-head (here, Ritter) merges as a noun phrase in the specifier of the head noun. I propose that it moves to gender, as we have seen above in (77), and that family names are also marked for gender in the Dutch noun phrase. I have no immediate evidence for Number in the non-head, so I do not assume it in structure. This non-head incorporates into its own determiner layer, where it receives its own proper name semantics. Crucially, the non-head (Ritter) never incorporates into the head (professor). This lack of incorporation defines the structure as a construct rather than a compound: the two nouns never truly merge into one another. In other words, they do not end up forming a single word.

| (91) | beyt | ha-‘is | [Hebrew, Ritter 1991] |

| house | the-man | ||

| ‘the man’s house’ | |||

| (92) | professor Ritter | [Dutch] | ||

| professor Ritter | ||||

| ‘professor Ritter’ | ||||

|  | |||

As can be concluded from the structures, the Dutch title expression is analyzed as a construct state, but one in which the second part undergoes N-to-D movement, blocking the insertion of a determiner. In other words, it is a referential construct state.

In the construct state, the head noun moves through the nominal inflectional domain and allows for the possibility of nominal inflection of the head noun in the form of number marking and diminutives, as can be concluded from the examples in (93)–(95):

| (93) | professoren | Kayne | en | Labov | [Dutch] |

| professors | Kayne | and | Labov | ||

| ‘professors Chomsky and Kayne’ | |||||

| (94) | prinses-je | Elizabeth | [Dutch] |

| princess | Elizabeth-diminutive | ||

| ‘little princess Elizabeth’ | |||

| (95) | prinses-je-s | Elizabeth | en | Amalia | [Dutch] |

| princess-diminutive-plural | Elizabeth | and | Amalia | ||

| ‘the little princesses Elizabeth and Amalia’ | |||||

Note that the agreement in number between the title and the proper name in the construction clearly distinguishes these constructions from compounds. In summary, Dutch has referential construct states alongside referential compounds.

7. When Is N-to-D Movement Licit?

In Section 5, I observed a contrast between the referential compound and the -s possessive. It involved the issue that some roots which qualify for unique reference do not undergo N-to-D raising when in argument position, as is the case for zon ‘sun’ in example (84). This goes hand in hand with the fact that they cannot occur as the non-head of the s-possessive either, as shown in example (85):

| (96) | #Ik | zie | zon. |

| I | see | sun |

| (97) | *zons | zachte | warmte |

| sun’s | gentle | warmth |

However, they can be the non-head of the referential compound, as can be concluded from example (86):

| (98) | zon-s-verduistering |

| sun-s-eclipse | |

| ‘solar eclipse’ |

Why are some roots unable to undergo N-to-D raising and what causes the opposition between the referential compound and the -s possessive? Borer (2005, pp. 84–85) discusses the issue that certain proper names, such as the Bronx or the Pacific Ocean, cannot occur without an article. After some discussion, Borer concludes that ‘for reasons we can only speculate on’ certain roots are banned from being proper names. She assumes that the reason is to be situated outside of syntax proper.

The present data point in the direction of Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia is a module that plays a role in the post-syntactic interpretation of the sentence in the model of Distributed Morphology, which provides input to a conceptual interface. In Distributed Morphology, the conceptual interface receives input from three different modules in order to assign a meaning to the derivation. Firstly, it interprets the output of Logical Form (LF). LF is the interface which takes the syntactic structure as its input. It interprets the morphosyntactic features, such as ‘plural’ or ‘definite’, compositionally. This ensures that all interpretable features which were present in the syntax will be interpreted. For the derivations presented in this article, LF would ensure that the presence of the head little d is interpreted and that the incorporations are interpreted as compound-forming. Secondly, the conceptual interface can access information from Encyclopedia. Encyclopedia is a learned list which matches constituents and the vocabulary items that may realize them to an interpretation. It contains the information that a VP realized as kick the bucket should be understood as ‘die’, but it has also stored the meaning of the word cat. One can understand the module as the inventory of lexical semantics. In Encyclopedia, any meaning can, in principle, be attached to any structure. However, there is one important restriction. The compositional meaning which is computed at LF on the basis of morphosyntactic features can never be overridden (McGinnis 2002).

Now, let us assume that for some roots the combination of the definite article plus the root is actually stored at Encyclopedia as the proper way to refer to the entity. For example, de zon is the conventional, lexicalized Dutch way to refer to the sun, whereas Zon is not. If zon ‘sun’ would then move to D, Encyclopedia would not be able to assign a reference to the construction. More generally, it follows that there is a rather superficial, extra-syntactic ban on the N-to-D movement. Syntax itself does not prohibit the movement. Interestingly, this makes the empirical predictions that if one can alleviate the extra-syntactic limitation, the N-to-D movement should be licit again.

Now consider the syntax of title expressions. They do not undergo N-to-D raising in argument position, as can be concluded from the pair of examples in (99)–(100)25:

| (99) | *Ik | feliciteer | professor. |

| I | congratulate | professor |

| (100) | Ik | feliciteer | de | professor. |

| I | congratulate | the | professor | |

| ‘I congratulate the professor.’ | ||||

The ban on the N-to-D movement for such roots is rather clear: they lack the typical unique reference which Encyclopedia requires to interpret the structure and there is no idiom stored to interpret the structure either. Note also that the default encyclopedic interpretation for N-to-D movement would fail: professor should not be interpreted as a proper name, because the sentence is not about a person whose proper name is Professor.26 In summary, the structure is uninterpretable.

However, in title expressions, the title itself is subject to N-to-D movement, allowing the entire title expression to pattern with proper names both syntactically and semantically (see Section 5). Crucially, when combined with a proper name, there is no ban on moving to D for a title. After all, why should there be such a ban? A title expression has the same semantics as a proper name, and it is thus fully interpretable: it has unique reference. These observations illustrate that syntax has no general ban for certain roots to move to D, the ban is interpretational.

Consider further the fact that many of the referential compounds under discussion are stored, lexicalized words. In other words, Encyclopedia has an interpretation stored that matches their structure, as illustrated in (101):

| (101) | zonsverduistering↔“solar eclipse” |

The fact that the root zon ‘sun’ would require the determiner in argument position to refer to the star so familiar to us is simply irrelevant for the interpretation of the compound at Encyclopedia. Notably, even if the compound had not been stored, the reasoning still holds. The non-head of a compound is a unique syntactic position which is arguably subject to its own interpretational rule at Encyclopedia.

More generally, it had been noted before that there is no ban on incorporating ‘proper names that require an article’ in compounds, as shown in (102) (example taken from Borer 2005, p. 84, who cites Peter Ackema for suggesting it):

| (102) | Bronx-lover |

Note that the same pattern occurs in Dutch. Dutch also has proper names that obligatorily involves a definite determiner, as can be seen in (103). The determiner disappears when the proper name is part of a compound, as shown in (104)27.

| (103) | de | Jordaan |

| the | Jordaan | |

| ‘de Jordaan’ (a specific neighborhood in Amsterdam) | ||

| (104) | Jordaan-bewoner |

| Jordaan-inhabitant | |

| ‘inhabitant of the Jordaan’ |

The information stored at Encyclopedia to interpret the noun phrase de Jordaan as a proper name thus includes the definite article. This specific rule will block the more general proper name syntax. However, this specific rule does not apply to the compound, given that it is a different structure. I conclude that it follows that the set of roots that can occur in referential compounds is a superset of the set that can occur in the -s-possessive: roots with unique reference that would otherwise require a definite article in argument position may occur in the compounds, but not in the -s possessive. More generally, the idea that the ban on N-to-D movement for roots such as sun and Bronx is extra-syntactic seems to be on the right track.

8. Conclusions

This article argued that noun–noun compounding with referential non-heads are a possibility. This was often seen as principally excluded: for noun–noun compounding, a non-head noun incorporates into a head noun; hence, there is no determiner layer for the non-head that could result in referential meaning. However, it was known that other constructs with referential non-heads do exist and that the noun in a noun–verb incorporation could be referential as well. This article has argued that, indeed, noun–noun incorporations, i.e., noun–noun compounds, can have a referential non-head. The non-head noun than first merges into a referential determiner-head and this complex head than eventually merges into the head noun.