Abstract

This work describes a case of object clitic reduplication (OCR) in restructuring sentences, in a Central Italian dialect: Perugino. OCR (not attested in the local variety of Italian spoken in Perugia) is optional and alternates with either enclisis or proclisis. It may concern direct and indirect object clitics, without person restrictions, locatives, partitives and reflexives. Only proclisis is instead possible with middle se. In sentences with more than one restructuring predicate, the clitic can occur only twice, and with some restrictions. The data suggest that middle se does not behave like (other) object clitics, including reflexive uses of se, a distinction also revealed by standard Piedmontese. The data also reveal that the boundaries of the two closely related non-standard varieties (the dialect and the local variety of Italian spoken in Perugia) are not blurred, nor are there intermediate repertoires or dialect continua. OCR is compatible with monoclausal as well as with biclausal analyses of restructuring sentences, but not with models that assume a different structure/derivation for restructuring sentences in the case of proclisis and in the case of enclisis. If a monoclausal structure is to be assumed, OCR suggests that there are (only) two clitic positions/strings in the clause. The lower position/string, however, cannot be made available only by lexical verbs.

1. Introduction

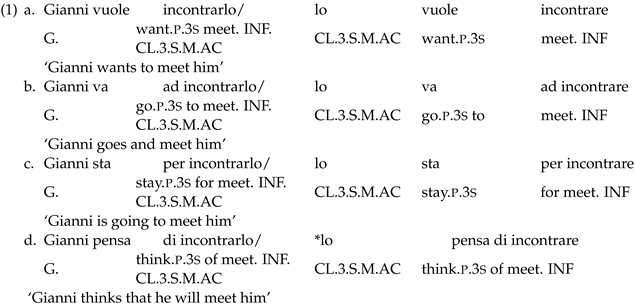

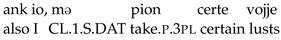

It is a well-known feature of certain Romance languages that in some clauses containing predicates which select an infinitival complement, an object clitic pronoun may appear either as enclitic to the infinitive verb or as proclitic to the finite verb, as shown in (1) from Italian:

|

The ‘climbing’ (Kayne 1975) of the clitic to the finite verb is a transparency effect which is allowed only by some (matrix) predicates (as shown by its agrammaticality in (1.d),which, after Rizzi (1976), are known as ‘restructuring’ predicates and include modal, motion and aspectual predicates.

In what follows, I will refer to these (complex) clauses containing restructuring verbs as ‘restructuring sentences’.

It is also well known from the literature that clitic climbing is not genuinely optional in non-standard registers of Italian, as northern varieties of Italian prefer enclisis, while southern varieties prefer proclisis. Dialects are even stricter than varieties of Italian, with Northern Italian dialects requiring, or strongly preferring, enclisis and (most) Southern Italian dialects requiring, or strongly preferring, proclisis (Rohlfs 1968; Benincà 1986; Monachesi 1995 a.o.).1

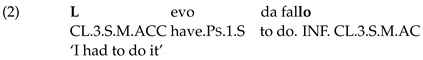

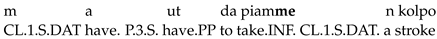

We also know from the literature (Benincà 1986; Parry 1995; Ledgeway 1996; Cardinaletti and Shlonsky 2004; Cinque 2006; Pescarini 2021 a.o.) that few varieties allow two instances of the same clitic (one attached to the modal and one to the infinitive) within one and the same restructuring context. The aim of the following lines is to describe this phenomenon—illustrated in (2) below—in one of those varieties: Perugino, a Central Italian dialect.

|

I will refer to the phenomenon illustrated in (2) as ‘Object Clitic Reduplication’(OCR). I use the term ‘reduplication’ in order to single out this particular kind of doubling among doubling phenomena, distinguishing it, provisionally, from non-identical doubling (Barbiers 2008; Poletto 2008 a.o.), where an argument is realized through two (partially) different elements, one of which at least has a phrasal status and may involve some kind of dislocation. Both OCR and non-identical doubling, which co-occur in (3), are well attested in Perugino, but in the following, I will concentrate on the former:

| (3) |  | |

| ‘You have to quit with hearty meals’ | (Spinelli 2003, p. 15) | |

In Section 2, I will attempt a description of OCR in Perugino, drawing basically on three kinds of data: (a) oral spontaneous data produced by different native speakers; (b) a written corpus consisting of the complete works of the dialectal poet Claudio Spinelli (Perugia, 1930–2002); (c) grammaticality judgments. Finally, I will delimit the phenomenon considering neighboring dialects, and examine it in comparison to what is observed in two varieties, geographically distant from Perugino, drawing on work by Parry (1995): the dialect of Cairo Montenotte and standard Piedmontese.

In Section 3, although the aim of this work is mainly descriptive, I will briefly examine OCR in relation to some comparative and theoretical issues.

In Section 4, I will draw some conclusions.

2. Object Clitic Reduplication in Perugino

2.1. Some Notes on Perugino

Perugino is a Central Italian dialect, spoken in Perugia (Umbria) and 15 surrounding districts: Tuoro, Passignano, Magione, Lisciano Niccone, Corciano, Deruta, Torgiano and parts of the territories of Castiglione del Lago, Panicale, Piegaro, Marsciano, Bettona, Valfabbrica and Bastia (Moretti 1987).

As a matter of fact (possibly due to historical and/or geographical reasons; see Mattesini 2002, on this matter), Perugino has not spread beyond its narrow boundaries, and this also applies to the other dialects spoken in Umbria, so that the dialectal landscape of Umbria is quite variegated: three main areas, plus two (Moretti 1987) or three (Mattesini 2002) ‘transitional zones’ are traditionally recognized in Umbria, with Perugino pertaining to the Northern area.2

Similarly, there is no ‘regional’ variety of Italian in Umbria, and we can only talk about a ‘local’ variety of Italian spoken in Perugia.

Assuming a distinction between the dialect and the local variety of Italian spoken in Perugia, in the following, we will be concerned with the dialect, where the feature we are dealing with, i.e., OCR, is widely attested.3 We may indeed add OCR to the features differentiating the dialect (in which OCR occurs) and the local variety of Italian (in which OCR does not occur).

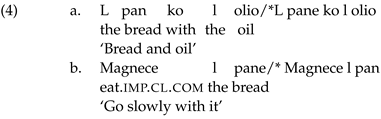

Perugino has been described mainly (though not exclusively) in terms of its phonological characteristics and lexicon, following a long-standing tradition in dialectology.4 I will not reproduce here what can be found elsewhere (Ugolini 1970; Moretti 1987; Mattesini 2002 a.o.), but will just signal a feature underlined by all the above-mentioned authors, which will be relevant for further discussion: a generalized weakness of non-tonic vowels, which singles out Perugino with respect to the other dialects spoken in Umbria, even those pertaining to the Northern area, in which non-tonic vowel weakening is far less frequent and strong.5 It is described as involving various degrees (from attenuation to total drop) and to occur word internally (with variation among speakers, e.g., tavola, tavəla, tavla, ‘table’, adapted from Mattesini 1995: xv) or, more often, as a context-dependent phenomenon:

|

The systematic lack in Perugino (as well as in the local variety of Italian) of the final syllable -re of the infinitive, attested in Italian, is considered an outcome of this tendency (Moretti 1983; Mattesini 1995):

|

OCR is not explicitly singled out in the quoted works. Moretti (1987) indeed mentions ‘pronominal redundancy’ among the morphosyntactic peculiarities of Perugino, but the two examples he reports are cases of non-identical doubling, possibly Hanging Topic constructions, as shown in (6) below:

| (6) |  | (adapted from Moretti 1987, p. 49) |

| ‘As for me as well, sometimes I have some cravings’ | ||

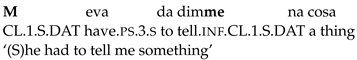

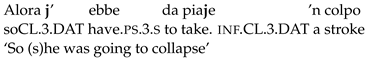

An example of OCR is mentioned incidentally elsewhere (among the constructs with ‘have’):

| (7) |  | (Moretti 1987, p. 59) |

| ‘I was going to collapse’ | ||

2.2. The Data Collection

Before moving to OCR in Perugino, let me briefly describe the data collection. As mentioned above, I basically drew on three kinds of data: (a) oral spontaneous data produced by different native speakers; (b) the complete poems of Claudio Spinelli; (c) grammaticality judgments. For the data concerning neighboring dialects, I asked for the translation of the Italian equivalent, plus some grammaticality judgments (see Section 2.4 for further details).

As for the (a) data, they were collected over time by myself, simply taking note of what I heard around me.6 I am not able to tell exactly how many informants contributed, since OCR, as mentioned, is quite widespread in the dialect, and native speakers frequently resort to the dialect when talking to each other.

As for the (b) data, I decided to rely on this as a second resort, i.e., in case they were confirmed by/confirmed spontaneous data (see Section 2.3.4). I did so for two main reasons. On the one hand, writers can introduce individual innovations (or preserve archaisms) for stylistic purposes, and nothing grants that what is found in their texts reproduces what the linguistic community shares. On the other hand, things might have changed slightly in the time elapsed since Spinelli’s poems and today.

As for the latter kind of data, i.e., grammaticality judgments, I created the relevant sentences with the help of a native speaker.

Single grammaticality judgments (e.g., those concerning dové; see Section 2.3.8) were collected orally interviewing a subpart of the speakers who produced the spontaneous data, while for the sentences with two restructuring verbs, I created a written set of sentences (see Section 2.3.7 for further details). Grammaticality judgments were not always easy to obtain, and this is not surprising given that my informants are speakers of two closely related, non-standardized varieties (the dialect and the local variety of Italian), with competence in (and use of, in many cases) the standard variety of Italian. It is well known that speakers with multilingual competence of closely related varieties might indeed have problems with grammaticality judgments. As discussed in Leivada et al. (2017), one of the problems relates to a prescriptive notion of correctness that interferes with speakers’ perceptions of their own linguistic repertoire. In some areas (see Section 2.3.8), I found either conflicting judgments among speakers or a few speakers who declared that they were not able to give the required judgment, and even a speaker who did not accept a sentence but produced a sentence of the same type in spontaneous speech (see Cornips and Poletto 2005, for a similar report). However, in other areas (see Section 2.3.5 and Section 2.3.7), judgments were indeed very clear. Since grammaticality judgments are necessary to properly describe and delimit a phenomenon, I have resorted to them, though I am aware of the potential related problems in this particular circumstance.

2.3. OCR in Perugino

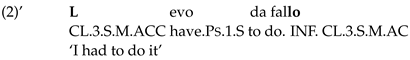

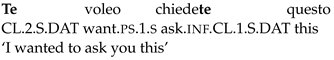

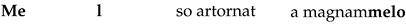

Moving to the point, as illustrated in (2), repeated below for convenience, in some clauses containing predicates which select an infinitival complement, Perugino allows an object clitic to appear as proclitic to the finite verb and as enclitic to the infinitive:

|

2.3.1. Optionality

A first characteristics of OCR is its optionality:

|

All of the cases in (8) are possible in Perugino, i.e., proclisis to the finite verb as in (8.a), enclisis to the infinitive as in (8.b) and OCR as in (8.c), and speakers do not report on any preferences nor pragmatic/discourse-related differences motivating one or the other of the three options. Option c. (i.e., OCR) seems to be determined only by a deeper entrenchment in the dialect in that precise circumstance, as some informants declared (‘The more I speak Perugino, the more I use it’ or ‘The heavier my Perugino, the more I use it’).

2.3.2. OCR and Clitic Climbing

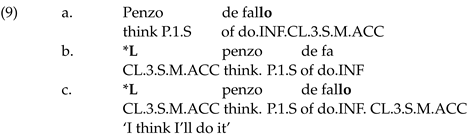

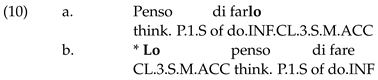

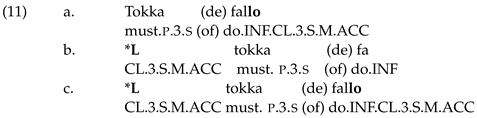

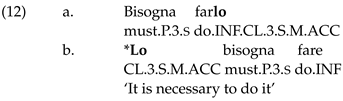

Of course, OCR is contingent on the possibility of having proclisis, i.e., it does not hold for the predicates that do not allow ‘clitic climbing’, and I did not find any dissimilarity between Italian and Perugino in relation to the members of this class of predicates:7

|

as in the Italian equivalent:

|

Similarly, we have:

|

as in the Italian equivalent:

|

2.3.3. OCR and Restructuring Predicates

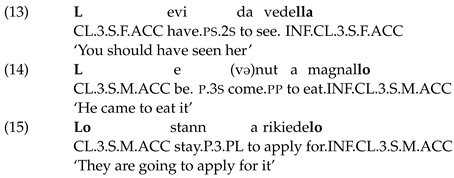

Thus, the possibility of OCR holds when a predicate allowing ‘clitic climbing’ is involved, i.e., with restructuring predicates, such as modal (13), motion (14) and aspectual (15) predicates:8

|

2.3.4. OCR and Causative and Perception Verbs

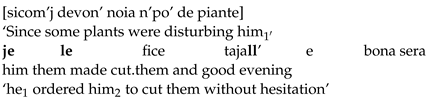

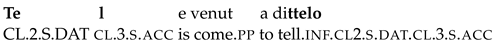

The possibility of OCR apparently holds also in contexts whose Italian equivalent requires proclisis to the inflected verb, e.g., constructions with causative or perception verbs as shown in the following examples from Spinelli (2003):

| (16) |  | (Spinelli 2003, p. 88) | |

| (17) |  | (Spinelli 2003, p. 242) |

However, (16) and (17) are the only examples of this kind that I have been able to collect, and both are literary examples. So, I do not think I am allowed to speculate on them until further evidence is available, for the reasons briefly discussed in Section 2.2.9

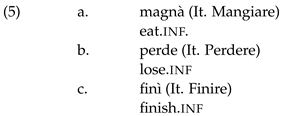

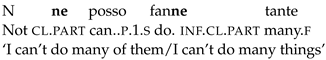

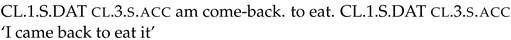

2.3.5. Clitics Involved in OCR

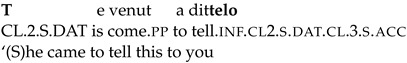

Returning to restructuring contexts, a further characteristic of OCR is that it may involve direct as well as indirect object clitics (without person restrictions), reflexives, partitives and locatives:

| (18) |  | |

| (19) |  | |

| (20) |  | (Spinelli 2003, p. 204) |

| (21) |  | |

| (22) |  | |

| (23) |  |

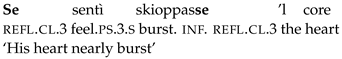

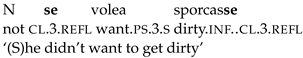

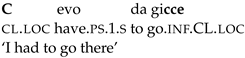

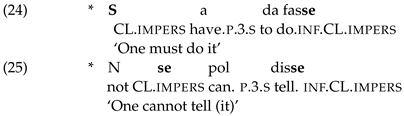

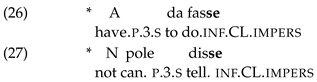

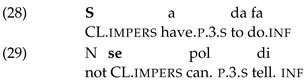

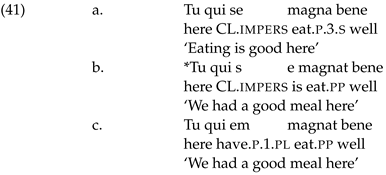

With ‘impersonal’ se, instead, OCR is judged ungrammatical:

|

Simple (non-reduplicated) enclisis is also ungrammatical:

|

The only possibility, with impersonal se, is proclisis to the finite verb:

|

2.3.6. Clustering

When clitics cluster, the entire cluster is usually (but not always) reduplicated:

| (30) |  |

| (31) |  |

| (32) |  10 10 |

| |

| (33) |  |

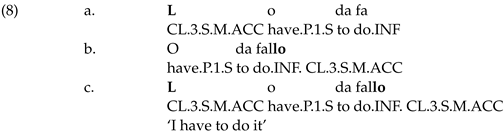

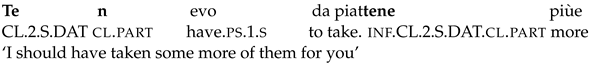

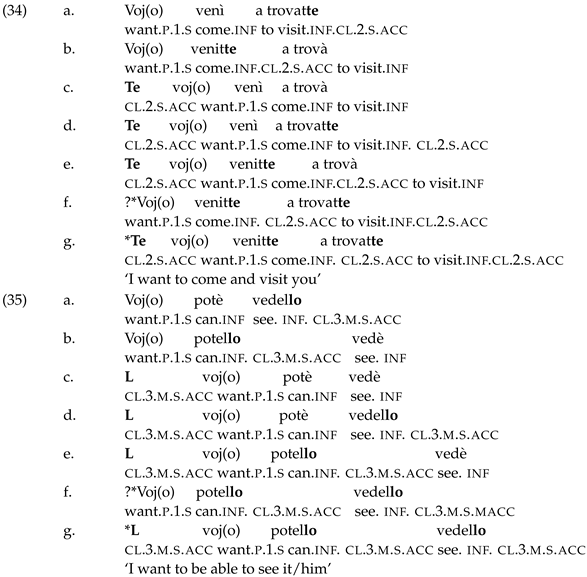

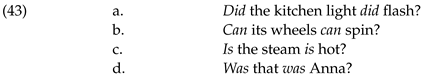

2.3.7. Sentences with Two Restructuring Verbs

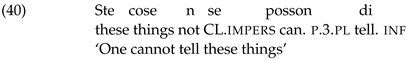

In clauses containing more than one restructuring verb, the clitic cannot appear three times (see 34.g and 35.g). The f. options (double enclisis) are judged ungrammatical by most speakers:11

|

All other options (a., b., c., d. and e.) are judged possible.12

2.3.8. An Exception?

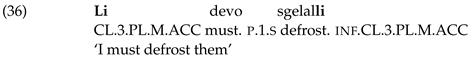

Given these general characteristics of OCR, let us return to the issue introduced in footnote 8, namely, the possibility that OCR may be not possible with some restructuring predicates.

Some speakers find OCR at odds (or not possible) with dovè (‘must’). Judgments are not very clear in this particular case, however. One of these speakers produced an example of OCR with dovè in spontaneous speech, shown in (36), while not accepting the (analogous) sentence presented for judgment:

|

I did not find an instance of OCR with dovè in Spinelli (2003), but I did not find dovè in restructuring contexts in general in Spinelli (2003). Other speakers find OCR with dovè possible.

One possibility to explain these data is that dové, for some of these speakers, is not part of the dialect, but rather the equivalent of the dialectal ‘avè da’ in the local variety of Italian. Since OCR is not possible in the local variety of Italian, they judge ungrammatical examples of OCR with dové or, as in the case of Spinelli (2003), avoid using OCR with dové (and dové in general when speaking/writing the dialect). If this is correct, then these speakers do have a distinction between the dialect and the local variety of Italian as part of their multilingual competence.13

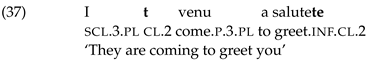

2.4. OCR in and Beyond Perugino

The results of a preliminary inquiry (with few detection points, however) suggest that OCR is not attested in the dialects around Perugino.

It is not attested in Ficulle (South–Western area), Assisi and Todi (Todi–-Scheggia transitional zone), Foligno (Southern area) and Gubbio (Northern area).

Proclisis is preferred by all the speakers.14

As mentioned in Section 1, however, OCR is not an isolated case in Romance languages, nor in the dialects of Italy. One case in point is the (fundamentally) Piedmontese dialect of Cairo Montenotte, on the Ligurian/Piedmontese border (Parry 1995):

|

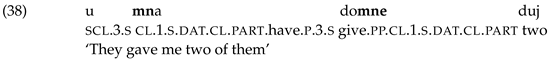

In this dialect, contrary to Perugino, a double occurrence of an object clitic can be found also in the perfect periphrasis, as shown in (38):15

|

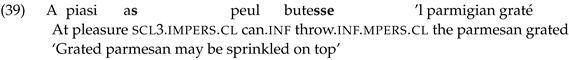

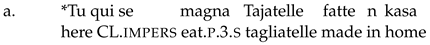

Another difference between the two dialects is that in the dialect of Cairo Montenotte, as well as, more in general, in ‘standard Piedmontese’, a similar kind of double occurrence is found with impersonal se (both in the modal and the perfect periphrasis):16

|

In standard Piedmontese, impersonal se is the only clitic reduplicated in restructuring sentences.

3. Some Comparative and Theoretical Issues

3.1. Clitic Reduplication in Perugino, Standard Piedmontese and the Variety of Cairo Montenotte

Interestingly, according to Parry (1995), the three cases illustrated in (37), (38) and (39) have an independent diachronic origin. Their co-occurrence, thus, does not entail any implicational relation, and leaves some space to consider the case in (37)—and, to a certain extent, the case in (39)—akin to the data described in Section 2.3 for Perugino, i.e., as the expression (in unrelated varieties) of a possibility made available by universal grammar.

The presence of the object clitic in enclisis to the past participle is considered by Parry (1995), following Meyer-Lübke (1900), as a means to avoid the ambiguity that arises from the fact that the third person singular subject clitic a before a vowel was al: so, al a mangià (he has eaten) and a l’a mangià (he has eaten it) were ambiguous. Hence, a l’a mangialo (he it has eaten it) could solve the problem.

As for the latter feature, shown in (39), Parry (1995) considers it connected to the fact that se in Piedmontese seems to be something different from the Italian si. More precisely, she argues (1995, pp. 148–49) that se in Piedmontese is not the complement argument of the infinitive but merely the marker of an impersonal passive construction. As a grammatical morpheme of voice, se has no closer semantic link with the embedded infinitive than with the sentence as a whole, so that it remains attached to the modal verb just as the grammatical morpheme of tense and mood. The other object clitics, instead, are required to be in enclisis to the infinitive in the modal periphrasis in Piedmontese; otherwise, they would unnecessarily interrupt the ‘subject clitic + verb’ nexus. Parry considers the conservative variety of Cairo Montenotte, with a double occurrence of the object clitic (37), to be an intermediate stage in the passage from proclisis (attested in earlier periods of Piedmontese) to enclisis, a stage also attested in 17th- and 18th-century texts in Piedmontese. As for its characterization, Parry (1995) assumes that the complement clitic originates to the right of the verb with which it is semantically associated: then, movement to the left leaves a copy in the original position.

We leave aside the Meyer-Lübke/Parry conjecture on the origin of enclisis to the past participle, since this feature does not concern Perugino.17

Subject clitics, however, are considered by Parry as a driving feature also of OCR and enclisis in the modal periphrasis. Nowadays, Perugino basically does not have subject clitics. Moretti (1987, p. 48 and fn.62) describes some crystallized forms of subject clitics enclitic to the complementizer ke or to some verbal inflections (e.g., be), plus a ‘fixed’ expression (t e ragione; s a ragione, ‘you are right; (s)he is right’) with proclitic subject clitics. Subject clitics of the enclitic kind are however widely attested in a XVI century text (I Megliacci by Mario Podiani, 1530; Ugolini 1974), so one cannot exclude that they are also connected to the origin of OCR also in Perugino. In any case, they were mostly enclitic, so the presence of a proclitic object clitic would not interrupt the subject/verb sequence.

I leave to future research, however, an inquiry on earlier stages of Perugino and on the historical emergence of OCR in this language.

3.2. On se Constructions

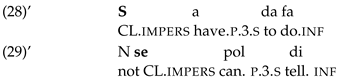

As we mentioned, data like (39) are also not attested in Perugino. As we have seen in Section 2.3.5, in Perugino, there is a clear distinction, as regards OCR, between reflexive se and what we have called ‘impersonal’ se. If we assume with D’Alessandro (2002, p. 36), that impersonal constructions are a way of introducing a generic, unspecified subject in an utterance, we might indeed consider (28) and (29), repeated below for convenience, as examples of impersonal se constructions:

|

However, some of the relevant literature on si constructions in Italian (see Manzini and Savoia 2007, for a review) distinguishes between the ‘real’ impersonal constructions (where there is no agreement with an object) and those constructions in which the verb agrees with an object, with the latter assumed to have a middle/passive reading. Assuming this distinction, I analyze se in Perugino as a middle/passive marker:

|

The ‘real’ impersonal se is not attested in Perugino, where, as in Piedmontese (Parry 1995), a construction equivalent to Italian ‘li si fa’ is not possible (see also (41.b) below).

A further distinction is proposed by Cinque (1988) within the middle/passive constructions, with some having a middle or property reading, possible only with generic time reference (and a limited class of verbs), and some having a passive reading proper. I suggest that Perugino displays the former but not the latter:

|

The fact that (41.b) is ungrammatical is part of a general lack of passive constructions in Perugino, noted by Moretti (1987, p. 59).

The fact that (41.a) is not a ‘real’ impersonal se construction is confirmed by the fact that when an object is present, the verb agrees with it:

| (42) |  | |

| kasa18 home |

In summary, there are reasons to believe that the ‘impersonal’ se construction in Perugino is a middle construction with a property reading. If so, it seems to be the case that the same kind of se characterizes Perugino and Piedmontese (as well as the variety of Cairo Montenotte).

As noted by Cinque (1988, p. 521), introducing distinctions within the class of si constructions is not incompatible with the program of unifying all uses of si. Within this program, Manzini and Savoia (2007) assume, following earlier proposals by Manzini (1983, 1986), that there is a single lexical item si, and that the range of interpretations associated with it depends on the fact that si has the semantics of a free variable. While impersonal si is bound by a (generic/universal) quantifier, for other uses, the value of the variable introduced by si is fixed by an antecedent. In passive reading, in particular, the implication is preserved that ‘the event takes place through an external agency or cause, interpreted in the way of all so-called implicit arguments, i.e., as a generic’ (Manzini and Savoia 2007, p. 165).

The point I would like to make is that this generic external agency is not to be identified with an internal argument of the verb, but rather with an external argument, so I think that Manzini and Savoia’s conclusion that si is an object clitic (Manzini and Savoia 2007, p. 174) in all its uses is not justified, if by ‘object clitic’ we mean a clitic which lexicalizes the internal argument. Nor is this conclusion needed in order to achieve the goal of a unifying treatment of all the uses of si, in my opinion: this goal is well achieved under the assumption that si is a unique lexical item with the semantics of a free variable.19

As for reflexive si, I think the conclusion that it is an object clitic should be maintained instead.

Manzini and Savoia (2007) assume that in the reflexive reading, the subject is lexicalized by an argument with referential properties independent of those of si: if so (adding perhaps a process of identification, along the lines of Chierchia 1995), the object clitic nature of reflexive si is derived.

On the basis of these considerations, I would like to suggest that clitic reduplication (and enclisis in general) in restructuring sentences in Perugino is possible only when an object clitic is involved.

This is the case of reflexive se, as we have seen in (21), but not of ‘middle’ se (as shown in (24) and (25)). If middle se in Perugino, in standard Piedmontese, and in the variety of Cairo Montenotte have the same reading, the prima facie different behavior of se in restructuring contexts in the three varieties calls for an explanation. Interestingly, both Perugino and standard Piedmontese single out middle se, though the distinction leads to seemingly mirroring ending points: in Perugino, se is not reduplicated; in standard Piedmontese, se is the only clitic which is reduplicated. There is however another possible (and more appealing, in my view) way to interpret the picture. Assuming that OCR reflects a stage of the process from proclisis to enclisis (possibly tied to the presence of subject clitics), middle se is the only clitic that (a) survives in proclisis in standard Piedmontese and (b) resists enclisis in Perugino. If so, Perugino is one step behind the variety of Cairo Montenotte (where also middle se is reduplicated) and two steps behind standard Piedmontese (where all clitics except middle se are enclitic).

3.3. OCR among Doubling Phenomena

Though with possibly different origins in the history of the three languages, and with different characterizations, the instances of clitic reduplication observed in Perugino, in the variety of Cairo Montenotte and in standard Piedmontese are a peculiar case of doubling, in which a clitic (an object clitic in Perugino; an object clitic plus a (clitic) free variable bound by an external generic agency in the case of Cairo Montenotte; a (clitic) free variable bound by an external generic agency in standard Piedmontese) is reduplicated in restructuring sentences.

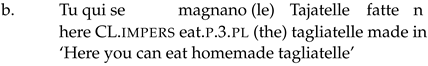

As we have seen in Section 3.1, according to Parry (1995), reduplication in restructuring contexts is explained assuming that the complement clitic originates to the right of the verb with which it is semantically associated: then, movement to the left leaves a copy in the original position.20 If so, OCR would be a case of clitic movement (or ‘climbing’ as we shall see in the next subsection), with the additional possibility of spelling out the (lower) copy as well. If so, it would be akin to data from child language, such as those reported by Radford et al. (1999, p. 324) concerning the double occurrence of the auxiliary:

|

The movement analysis is not the only possible analysis of OCR, however.21 Another possibility is that, if clitics are directly inserted where they appear (Manzini and Savoia 2007, a.o.), in OCR, two instantiations of an object clitic are merged in restructuring sentences. The movement analysis captures more directly the fact that the two instantiations are the realization of one and the same argument, a fact that under a representational view can be explained assuming, as in Manzini and Savoia (2007), that a unified interpretation of the two occurrences is realized in the interpretive component of the grammar.

Our data, however, do not shed new light on this issue, which does not concern OCR in particular, but doubling phenomena in general (see a.o. Barbiers 2008, for some discussion). Nor do our data shed light on the reasons why doubling (and this particular instance of doubling) is attested in some languages, and in Perugino in the specific case at stake here. A widely acknowledged feature of doubling is that it is more attested in non-standard varieties, which are less constrained by the ‘correctness’ norms fixed by grammarians. This could well be the case with Perugino, but cannot be an explanation: if so, the fact that other (equally non-standard) neighboring varieties do not display OCR would call for an explanation. One possible suggested reason for doubling is that for some reason, the information carried by one of the two copies/realizations is unclear, hence reduplication. In this connection, one of the features of doubling often emphasized is that the higher copy (or realization) is somehow reduced with respect to the lower one (leaving aside the cases involving left peripheral dislocations). Building on this feature, analyzing non-identical doubling in 267 Dutch dialects, Barbiers et al. (2008) propose a ‘partial copying’ account of doubling. Cardinaletti and Repetti (2004), discussing subject clitic alternations (in proclisis and enclisis) in a Northern Italian dialect, also observe a kind of reduction, and propose a phonological account of this reduction. Drawing on a similar set of data in different dialects, Manzini and Savoia (2016) instead propose that morpho-phonological alternations cannot be accounted for in terms strictly internal to the phonology or morphology, and that syntactic/semantic factors play a crucial role in determining them.

Returning to OCR in Perugino, some ‘reduction’ in the higher copy/realization seems to be involved as well. I cannot tell, at present, whether this is due to phonological reasons (the general tendency to reduce non-tonic vowels mentioned in Section 2.1) or whether other factors are involved. Leaving this issue to future research, I would like to note that if a reduction of some sort is involved in reduplication phenomena like OCR, the two occurrences are not in fact identical, and the distinction between identical and non-identical doubling is perhaps a distinction one can dispense with, especially if the reduction involves not only the phonological component. The two occurrences in OCR in Perugino, however, have an identical categorial status: as is the higher occurrence, the lower occurrence is a clitic as well, hence the examples of clitic clusters in (30)–(33).

3.4. OCR and the Structure of Restructuring Sentences

Let us now examine OCR in relation to a debated issue in the relevant literature, i.e., the nature of restructuring sentences.

Some approaches assume that the structure (or the derivation) of restructuring contexts is different when we have proclisis with respect to when we have enclisis. In this respect, OCR suggests that it is not desirable to conceive a different (and mutually excluding) structure/derivation for the two cases, since proclisis and enclisis co-occur in the same clausal type.

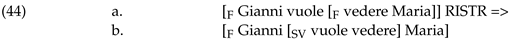

Drawing on Italian data, Rizzi’s (1976) seminal work indeed assumes a process (a rule, in the framework of the time) which he calls RISTR.

RISTR applies optionally with modal, aspectual and motion verbs, creating a complex predicate comprising the finite verb and the infinitive, hence turning a biclausal structure into a monoclausal one.

|

When a clitic is involved, proclisis is possible if RISTR has applied, while if RISTR does not apply, enclisis is found. Under these assumptions, OCR would appear as an impossible outcome, requiring RISTR to apply and not to apply at the same time.

As already noted (Cinque 2004, 2006; Cardinaletti and Shlonsky 2004), however, Rizzi (1976, fn. 18) addresses the issue of whether RISTR is a necessary (N) or a necessary and sufficient (N+S) condition for clitic climbing. If RISTR is only a necessary condition, enclisis is still possible when RISTR has applied. In addition, since in OCR we also have proclisis, RISTR must have applied. Thus, in this model, OCR entails a monoclausal configuration.

The idea that clauses containing a modal, aspectual or motion predicate and an infinitival complement are always monoclausal is developed by Cinque (2004, 2006), and assumes that ‘restructuring’ verbs are functional verbs, directly inserted in dedicated functional projections in the I domain (along a hierarchy proposed in Cinque 1999, on independent grounds):

| (45) | [CP…..[FP….[FP. Vrestr [FP…[VP V]]]]22 |

In this model, both enclisis and proclisis are possible (the choice possibly depending on factors different from the restructuring configuration; see Cinque 2006, p. 31), including the OCR option, assumed to entail a copy of the clitic in the lower position (Cinque 2006, p. 32).

Adopting Cinque’s (2004, 2006) proposal concerning the monoclausal structure of restructuring configurations, and the idea that the optionality of clitic climbing does not depend on structural differences of the clausal architecture, Pescarini (2021) assumes that this optionality (of clitic climbing) depends on the merging site of the functional verb. He proposes that (most) functional verbs entail an underspecified specification as to their merging site, while each functional verb ends up being attracted to a specific position in the I domain yielding a rigidly ordered sequence (while the lexical verb is moved to a dedicated position in the low I area).

If the functional verb is merged in V, it can incorporate the clitic (located in a position in the low I area, Z, after Ledgeway and Lombardi 2005) deriving climbing on its way to the I domain. If the functional verb is merged in I (above Z), it is not able to incorporate the clitic. In the latter case, the clitic is incorporated by the lexical verb.

It is not clear how OCR can be derived by this approach, unless assuming a mechanism allowing incorporation of the same element twice.

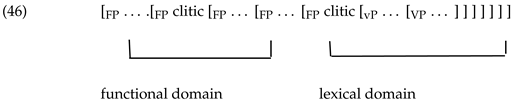

I think that if one assumes a monoclausal configuration of restructuring contexts, OCR leads to the more natural hypothesis that there should be two available object clitic positions in the clausal architecture (see also Cardinaletti and Shlonsky 2004, fn.6, for a similar claim based on the Piedmontese data discussed above).

Cardinaletti and Shlonsky (2004) argue that there are two clitic positions in Italian restructuring clauses, with one in the high portion of the IP and one in the lexical domain:

|

The position in the lexical domain is associated with (made available by) a lexical verb, and it is the same position occupied by the infinitive final [e] in Italian.

They further argue that when a clitic is manifested on an intermediate verb in a series, as in (47) below, the intermediate verb is in reality the highest functional verb in the CP, with the verb appearing on its left, vorrei in (47), being in a higher clause:

| (47) | Vorrei poterci andare |

| ‘I’d like to go there’ |

In other words, (47) has a biclausal structure shown in (48):

| (48) | Vorrei [poterci andare] |

| ‘I’d like to go there’ |

Restructuring does not go as high as volere, but stops with potere, which entails that volere is lexical in this case and selects a full CP.23

The clitic in (48) occurs in the higher clitic position in the clausal architecture.

The data reported in Section 2.3.7 (and partially reproduced in (49) below for convenience) firstly support the view that (if we assume a monoclausal structure of restructuring sentences) there are two (and only two) clitic positions:

| (49) | d. | L voj(o) potè vedello |

| e. | L voj(o) potello vedè | |

| f. | ?*Voj(o) potello vedello | |

| g. | *L voj(o) potello vedello |

I do not think, however, that these data support Cardinaletti and Shlonsky’s (2004) conclusions as regards the ‘partial restructuring’ analysis of restructuring sentences with two modal verbs. Since Perugino allows the double occurrence of a clitic in a clause, if (49) were a case of partial restructuring, (49.g) should have been possible, with one clitic in the higher clausal position of the embedding CP (L vojo), one clitic in the higher clausal position of the embedded CP (potello) and one in the clitic position in the lexical layer (vedello). Moreover, (49.f) should also have been possible, with the two clitics in the two clitic positions of the embedded CP. However, this is not the case.

I think the data suggest (again, assuming a monoclausal analysis of restructuring sentences) that there are two clitic positions even in sentences containing two restructuring verbs (hence, that there is no partial restructuring), and that the lower position is not made available by a lexical verb, but it is there independently, so that the clitic can surface on the lexical (49.d) as well as on the restructuring (49.e) infinitive but, crucially, not on both (49.f). 24

The considerations made above move us to another family of proposals on the structure of restructuring sentences. Kayne (1991) characterizes enclisis as derived by movement of the infinitive to the C domain. If this is the case, given the order finite verb-infinitive, a biclausal structure for restructuring sentences is automatically derived, and there is no need to stipulate two clitic positions to characterize OCR: the two clitics would be sitting in the clitic position made available by each clause.

A biclausal analysis of restructuring sentences is indeed assumed by Manzini and Savoia (2007). According to the authors, a unification of the event structure of the two predicates is observed in restructuring constructions. In particular, one property of modal and aspectual predicates is that their complement does not refer to an independent event; rather, the embedded and the modal/aspectual are taken to refer to a single event. Manzini and Savoia (2004, 2007) also argue for (independently motivated) clitic ‘strings’. The one immediately before I corresponds to the position(s) where clitics are usually merged, and can be replicated immediately before C and before V (as indicated by the dots in (50) below):

| (50) | [D [R [Q [P [Loc [N [C….[I….[V…. |

D, associated with definiteness, is the position where subject clitics are merged. R is associated with referentiality (specific quantification) and is a major source of reordering within the clitic string, since various kinds of clitics can be merged there. Q is the position where Italian si is merged, in its reflexives, impersonal and passive uses, while P, associated with person, is the position for 1st/2nd person (non-subject) clitics. Loc is the position for Italian ci (when strictly locative, instrumental, comitative, etc.), while N, associated with the nominal class, hosts third person clitics and partitive ne. Empirical evidence (i.e., the doubling of clitics on either side of the verb in C found in some dialects) suggests that the clitic string is repeated above C. As far as the string above V, i.e., in the argumental domain of the sentence, is concerned, the assumption is that lexical arguments are merged in (the Spec of) its relevant positions.

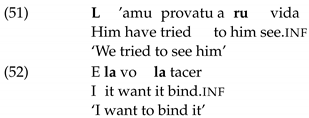

OCR is also well accounted for by a biclausal analysis of restructuring sentences together with the assumption of clitic strings, assuming that each clitic in the OCR construction occupies the relevant position in the clitic string in the I domain of each clause. Furthermore, the idea of a clitic string in the C domain could account for what we observe in some varieties with OCR, in which the clitic occurs to the left of the infinitive, such as Neapolitan (Ledgeway 1996, quoted by Cinque 2006, p. 32) in (51) or the Rhaeto-Romance variety of Fex Platta (reported by Pescarini 2021, p. 3) in (52):

|

Of course, other explanations are possible for the data in (51) and (52), compatible also with a monoclausal analysis of restructuring sentences.

So, to conclude this brief—and basically inconclusive—discussion, OCR can be accounted for by assuming a monoclausal structure as well as a biclausal structure for restructuring sentences. Since both proclisis and enclisis are presented in the same sentence, OCR is however incompatible with models that envisage a different structure or a different derivation for proclisis and enclisis.

The assumption of a monoclausal structure, given the data discussed here, leads to the natural postulation of two (and only two) clitic positions. One of these positions is certainly the clitic position (or string) in the I domain, and accounts for proclisis. A lower position is to be assumed to account for the enclitic occurrence, but this position cannot be made available by lexical verbs only.

4. Conclusions

In this work, I have described a case of object clitic reduplication (OCR) occurring in restructuring sentences in a Central Italian variety, Perugino. OCR in Perugino is optional and alternates with either enclisis or proclisis with no preference reported by the speakers. OCR is a characteristic of the dialect, not of the local variety of Italian spoken in Perugia, nor is it attested/allowed in neighboring dialects, where proclisis is preferred. OCR occurs, however, in other—geographically more distant—varieties, and a brief comparison with the variety of Cairo Montenotte and with standard Piedmontese (as described by Parry 1995) has been pursued. As I have shown, OCR concerns all object clitics in Perugino, but excludes se in its middle use. The situation of Perugino seemingly mirrors what is observed in standard Piedmontese, where only middle se is reduplicated in restructuring sentences, while in the variety of Cairo Montenotte, all clitics—including middle se—are reduplicated.

Assuming, with Parry (1995), that OCR reflects a stage in the process from proclisis to enclisis, I have suggested that the fact middle se is the only clitic that resists enclisis in Perugino and survives in proclisis in standard Piedmontese can be accounted for assuming that Perugino is one step behind Cairese and two steps behind standard Piedmontese along this process.

There are many issues that arise in connection with OCR, and the data presented here do not shed new light on most of them. One of these issues concerns the structure/derivation of restructuring sentences. In this respect, I have suggested that OCR is not compatible with those models that assume a different structure/derivation for enclisis and proclisis, since both enclisis and proclisis are attested in the same sentence in OCR. OCR can be accounted for either assuming a biclausal or a monoclausal structure for restructuring sentences. Assuming a monoclausal structure, OCR suggests that there are two positions (or series of positions) available for clitics. One of these positions (or strings) is the one in the I domain and accounts for proclisis. The lower position, as we have seen in the above discussion, cannot be made available only by lexical verbs but, as I argued, should be present independently.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Anna Cardinaletti, Sara Cerutti and Francesca Volpato for sharing with me some unpublished materials which inspired Section 2.3.7. I am grateful to all the informants who contributed the relevant data for this study. Finally, I thank two anonymous reviewers and the audience at the Linguistics Colloquia (Università degli Studi di Perugia, December 2021), the workshop The Syntax of Causative, Perception and Restructuring Verbs in Latin and Romance (Università di Pelermo, May 2022) and the 16th Cambridge Italian Dialect Syntax- Morphology Meeting for useful comments and suggestions. All errors and inconsistencies are of course my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Rohlfs (1968, p. 173) further suggests that enclisis is more attested in literary Italian, while in the ‘common language’, proclisis is more (and increasingly so) attested. For a recent inquiry on enclisis/ proclisis preferences across Italy, see Cardinaletti et al. (2022). |

| 2 | While Moretti (1987) includes Perugino, Eugubino and Castellano in the Northern area, for Mattesini (1995, 2002), the dialect spoken in Città di Castello pertains to a transitional zone, i.e., an area which ‘anticipates’ some features of other neighboring dialects, in the specific case, Romagnolo. This leaves only Perugino and Eugubino in the Northern area. |

| 3 | Moretti (1987) and Mattesini (1995, 2002) distinguish a third register: the rural variety of the dialect. Our data do not concern this variety, which is claimed to be disappearing at the time the quoted works were written. |

| 4 | See Benincà (1986) for some interesting considerations on the reasons behind such a tradition. |

| 5 | According to Ugolini (1970) and Moretti (1987), the weakness of non-tonic vowels, together with a tendency towards consonantal simplification (including the almost total absence of ‘raddoppiamento fonosintattico’), is responsible for the characteristic ‘martellato’ rhythm of Perugino. |

| 6 | Although I am not a native speaker of Perugino, I have been living in Perugia for many years. |

| 7 | An exception is perhaps the verb cerkà (It. cercare) when it means ‘try’, in that some speakers do not find l cerko de fa(llo) (‘I try to do it’) totally ungrammatical, cfr. It. *lo cerco di fare. As the reader might have noticed, I basically do not use an IPA transcription for the oral data, while for the written ones, I follow the original ‘system’ provided by Spinelli (2003). |

| 8 | It is possible that this does not necessarily mean that OCR occurs with all restructuring verbs. We will return to this issue in Section 2.3.8. |

| 9 | As an anonymous reviewer notes, in (16), only one clitic is reduplicated in the low position. With respect to (17), (s)he suggests that skioppà could be an unaccusative pronominal verb (skioppasse), and hence (17) may not be a case of true reduplication. I do not have clear data to exclude or confirm this hypothesis: it is possible that, although (17) sounds at odds for some speakers, both variants of the verb are attested inPerugino. |

| 10 | I have glossed as ‘dative’ the first-person clitic in this example, while it is rather a benefactive, typically found also in Italian in a similar construction (see D’Alessandro 2002). The meaning of (32) would be something like ‘I came back to eat it for me’. |

| 11 | These data were collected through a small written task consisting of four sentences (two with a modal and a motion verb, and two with two modal verbs) in the a./g. variants shown in (34) and (35). Five informants completed the task. For each sentence, they had to judge whether it was possible or not. For the possible sentences, they could also indicate the preferred one(s). Sentences of the g. type were judged ungrammatical in 95% of cases (19/20), while sentences of the f. type were judged ungrammatical in 70% of cases (14/20). |

| 12 | The acceptance rates vary slightly, from 100% for the b. and c. version, 95% for the a. version, to 75% for the d. and e. version. This may suggest that the contexts with only one clitic are more easily judged. Preferences are not always expressed by the participants, and when they are, they do not show a clear trend. |

| 13 | Leivada et al. (2017) discuss three features characterizing multilingual competence in closely related, non-standard varieties: blurred boundaries of grammatical variance, dialect continua and the emergence of intermediate speech repertoire, and the interference of a prescriptive notion of correctness on the speakers’ perception of their linguistic repertoire. I think that the data reported in this subsection support the idea that the speakers’ perception of their linguistic repertoire is somehow ‘disturbed’, but not that boundaries between the dialect and the local variety of Italian are blurred. Finally, variation among speakers supports the view of emerging repertoires, but they are by no means ‘intermediate’ or reflecting ‘dialect continua’: the difference solely concerns the presence vs. absence of a lexical item (dové) in the dialect. |

| 14 | Cinque (2006, pp. 31–32, and the references quoted there) places Central Italian dialects among the Romance languages where clitic climbing looks obligatory. Benincà (1986), basing her consideration on the relevant AIS maps (Jaberg and Jud 1928–1940), suggests that clitic climbing is optional in the varieties of Central Italy. My informants seem to be somehow ‘in between’ the two positions, in that they consider both enclisis and proclisis possible, but prefer proclisis. To elicit these data, I first asked for the translation of the Italian equivalent, which was given in the two versions possible in Italian (e.g., ti vengo a prendere/vengo a prenderti; voglio farlo/lo voglio fare). The translations always had proclisis. I then asked if the version with enclisis was also possible (e.g., Can you also say: ‘Vengo a pijjatte’?), and the answer was invariably ‘Yes, but ‘Te vengo a pijjà’ is better’. I then asked if the version with OCR was possible (e.g., Can you also say ‘ Te vengo a pijjatte’?) and the answer was invariably ‘No’. |

| 15 | Enclisis to the past participle is a typical feature of most Piedmontese varieties, but in ‘standard Piedmontese’, it is observed only with se. |

| 16 | As Parry (1995, fn. 1) acknowledges, standard Piedmontese is a mainly written variety based on the dialect of Turin. |

| 17 | According to Cardinaletti (2015), enclisis of a clitic to the past participle (as observed in some Piedmontese and Franco-Provençal dialects) is only outward, in that the pronoun enclitic to the past participle is not a clitic but a weak pronoun. |

| 18 | An anonymous reviewer suggests that the agrammaticality of (42.a) could be tied to the presence of a bare noun (tagliatelle), with bare nouns not present in Central Italian dialects. The ‘possible’ article in (42.b) could in fact be mandatory, and made ‘possible’ by attrition with Italian. While I agree with the observation concerning (42.b), I do not think that (42.a) is agrammatical just for the bare noun, because even:

|

| 19 | Data from L1 acquisition (as well as their analysis) provided by Belletti (2020) move in the same direction, in that children around the age of 4 use reflexive si with a passive meaning, i.e., in Belletti’s terms ‘as a route to passive’ (Belletti 2020, p. 73). |

| 20 | If middle se is to be analyzed in the terms proposed here (see also Parry 1995, pp. 148–49), the Piedmontese/Cairo Montenotte data on se are not directly explained by the idea that the clitic originates to the right of the verb with which it is, however, semantically related. |

| 21 | Nor of doubling in general, or of clitic ‘placement’ (i.e., the fact that an object clitic appears in a higher position with respect to a non-clitic object. For a movement analysis of clitic placement, see a.o. Sportiche 1996; Belletti 1999). |

| 22 | Note that the structure is different from the one in (44.b), in that in (45) but not in (44.b), the embedded and its complement(s) form a constituent (see Cinque 2004, 2006). |

| 23 | The idea that functional verbs can be functional or lexical is maintained in earlier proposals made by Cinque (e.g., Cinque 2001). Evidence comes from sentences containing a perfect periphrasis. One of the transparency effects connected to restructuring is indeed auxiliary switch (i.e., the fact that the ‘restructuring’ verb inherits the auxiliary of the (unaccusative) lexical verb). According to Cardinaletti and Shlonsky (2004), (i) is ungrammatical, contrary to (ii):

Although I find (iii) better than (i), I do not find (i) ungrammatical. See also Cinque (2006, p. 46) and Pescarini (2021).

|

| 24 | Of course, nothing can be said On the basis of the data presented here, nothing can be said on another (and independent) part of their proposal, i.e., the fact that the lower clitic position is the same position targeted by the infinitival ending [e] in Italian, since Perugino lacks not only [e] but also -r, as we have seen in Section 2.1. Interestingly, a double occurrence of an object clitic in enclisis to the infinitive has been occasionally observed outside restructuring contexts, in spoken standard Italian. One example, reported in Berretta (1986, p. 73), is quoted by Parry (1995, p. 145):

Another example was produced by an interpreter during a (broadcasted) simultaneous translation:

In both cases, speakers are involved in a formal speech and, in the latter case at least, in a cognitively highly demanding situation. I fundamentally agree with Berretta that these productions reflect the speaker uncertainty on how to organize the sentence constituents. Pushing this forward, I assume that they are production errors, i.e., ‘slips of the tongue’ in the sense of Fromkin (1973). In these non-restructuring sentences, the two clitics may be realized in the way assumed by Cardinaletti and Shlonsky (2004), i.e., with one clitic in the clitic position in the I domain (poterla in (ii)) and the other in the low position (incontrarla in (ii)). Crucially, however, (i) and (ii) are not restructuring sentences, so I do not agree with Parry (1995) who considers these structures akin to OCR. The ‘slip of the tongue’ at stake is simply, in my opinion, the simultaneous realization of the two possibilities for the clitics, which is banned in standard Italian. |

References

- Barbiers, Sief, Olaf Koeneman, and Marika Lekakou. 2008. Syntactic doubling and the structure of chains. Paper presented at 26th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, Berkeley, CA, USA, April 27–29; Edited by Charles B. Chang and Hannah J. Haynie. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Barbiers, Sief. 2008. Microvariation in syntactic doubling: An introduction. In Microvariation in Syntactic Doubling. Edited by Sief Barbiers, Olaf Koeneman, Marika Lekakou and Margreet van der Ham. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, Adriana. 1999. Italian/Romance clitics: Structure and derivation. In Clitics in the Languages of Europe. Edited by Henk van Riemsdjik. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 543–79. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana. 2020. Reflexive si as a route to passive in Italian. In Linguistic Variation: Structure and Interpretation. Edited by Ludovico Franco and Paolo Lorusso. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincà, Paola. 1986. Punti di sintassi comparata dei dialetti italiani settentrionali. In Raetia Antiqua et Moderna: W. Theodor Elwert zum 80. Geburztag. Edited by Günter Holtus and Kurt Ringger. Tübingen: Niemeyer, pp. 457–79. [Google Scholar]

- Berretta, Monica. 1986. Struttura informative e sintassi dei pronomi atoni: Condizioni che favoriscono la ‘risalita’. In Tema/Rema in italiano. Edited by Harro Stammerjohan. Tübingen: Narr, pp. 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Lori Repetti. 2004. Clitics in Northern Italian dialects: Phonology, syntax and Microvariation. University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics 14: 8–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, and Ur Shlonsky. 2004. Clitic positions and restructuring in Italian. Linguistic Inquiry 35: 519–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinaletti, Anna. 2015. Cases of apparent enclisis on past participles in Romance varieties. Isogloss 15: 179–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinaletti, Anna, Giuliana Giusti, and Gianluca Lebani. 2022. Clitic climbing across Italy: Optionality as a function of bilectalism. Paper presented at the 16th Cambridge Italian Dialect Syntax-Morphology Meeting, Naples, Italy, September 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chierchia, Gennaro. 1995. Impersonal subjects. In Quantification in Natural Languages. Edited by Emmon Bach, Eloise Jellinek, Angelika Kratz and Barbara H. Partee. Dordrect: Kluwer, pp. 107–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 1988. On Si constructions and the theory of Arb. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 521–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2001. Restructuring and the order of aspectual and root modal heads. In Current Studies in Italian Syntax. Essays Offered to Lorenzo Renzi. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Giampaolo Salvi. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 137–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2004. ‘Restructuring’ and functional structure. In The Structure of CP and IP. Edited by Luigi Rizzi. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 132–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo. 2006. Restructuring and Functional Heads: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. New York: Oxford University Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cornips, Leonie, and Cecilia Poletto. 2005. On standardising syntactic elicitation techniques (part 1). Lingua 115: 939–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, Roberta. 2002. Agreement in impersonal si constructions: A derivational analysis. Abralin 1: 35–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fromkin, Victoria. 1973. The non-anomalous nature of anomalous utterances. In Speech Errors as Linguistic Evidence. Edited by Victoria Fromkin. The Hague: Mouton, pp. 215–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jaberg, Karl, and Jakob Jud. 1928–1940. Sprach- und Sachatlas Italiens und der Südschweiz. Zoflingen: Ringier.

- Kayne, Richard S. 1975. French Syntax: The Transformational Cycle. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard S. 1991. Romance clitics, verb movement and PRO. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 647–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ledgeway, Adam, and Alessandra Lombardi. 2005. Verb Movement, Adverbs and Clitic Positions in Romance. Probus 17: 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgeway, Adam. 1996. The Grammar of Complementation in Neapolitan. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Leivada, Evelina, Elena Papadopoulou, Maria Kambanaros, and Kleanthes K. Grohmann. 2017. The Influence of Bilectalism and Non-standardization on the Perception of Native Grammatical Variants. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzini, M. Rita, and Leonardo M. Savoia. 2004. Clitics: Cooccurrence and Mutual Exclusion Patterns. In The Structure of CP and IP. Edited by Luigi Rizzi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 211–50. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, M. Rita, and Leonardo M. Savoia. 2007. A Unification of Morphology and Syntax: Investigations into Romance and Albanian Dialects. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, M. Rita, and Leonardo M. Savoia. 2016. Enclisis/proclisis alternations in Romance: Allomorphies and (re) ordering. Transactions of the Philological Society, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, M. Rita. 1983. On Restructuring and Reanalysis. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, M. Rita. 1986. On Italian si. In The Syntax of Pronominal Clitics, Syntax and Semantics Volume 18. Edited by Hagit Borer. New York: Academic Press, pp. 241–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mattesini, Enzo. 1995. Introduzione . In Luigi Catanelli Vocabolario del Dialetto Perugino. Perugia: Opera del vocabolario dialettale umbro, pp. IX–XXVI. [Google Scholar]

- Mattesini, Enzo. 2002. L’Umbria. In I Dialetti Italiani. Storia, Struttura, Uso. Edited by Manlio Cortelazzo, Carla Marcato, Nicola De Blasi and Gianrenzo P. Clivio. Torino: UTET, pp. 485–514. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lübke, Wilhelm. 1900. Grammaire des Langues Romanes. Paris: H. Welter. [Google Scholar]

- Monachesi, Paola. 1995. A Grammar of Italian Clitics. Ph.D. dissertation, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, Giovanni. 1983. Umbria, crocevia linguistico. Osservazioni sulle varianti umbre di italiano regionale (relativamente all’ambito fonologico). In Scritti Linguistici in Onore di Giovan Battista Pellegrini. Pisa: Pacini, pp. 519–31. [Google Scholar]

- Moretti, Giovanni. 1987. Umbria. Pisa: Pacini. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Mair. 1995. Some observations on the syntax of clitic pronouns in Piedmontese. In Linguistic Theory and the Romance Languages: Current Issues in Linguistic Theory. Edited by Martin Maiden and John C. Smith. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 133–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pescarini, Diego. 2021. Romance Object Clitics: Microvariation and Linguistic Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletto, Cecilia. 2008. Doubling as Splitting. In Microvariation in Syntactic Doubling. Edited by Sief Barbiers, Olaf Koeneman, Marika Lekakou and Margreet van der Ham. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, Andrew, Martin Atkinson, David Britain, Harald Clahsen, and Andrew Spencer. 1999. Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1976. Ristrutturazione. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 1: 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfs, Gerhard. 1968. Grammatica Storica Dell’italiano e dei Suoi Dialetti. Morfologia. Torino: Einaudi. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli, Claudio. 2003. Tutte le Poesie. Perugia: Guerra Edizioni. [Google Scholar]

- Sportiche, Dominique. 1996. Clitic Constructions. In Phrase Structure and the Lexicon. Edited by Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 213–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini, Francesco A. 1970. Nota introduttiva. In L. Catanelli, Raccolta di Voci Perugine. Perugia: Istituto di Filologia romanza dell’Università, Opera del vocabolario dialettale umbro, pp. ix–xxv. [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini, Francesco A. 1974. Il Perugino Mario Podiani e la sua Commedia “I Megliacci” (1530). Perugia: Istituto di Filologia romanza dell’Università, Opera del vocabolario dialettale umbro. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).