Abstract

This study explores the acquisition of the English quotative system and the innovative quotative variant be like among Chinese L2 speakers of English residing in Melbourne, Australia. The L2 speakers’ use of quotatives such as say, go, be like, and quotative zero is compared with quotatives used by native speakers of Australian English (AusE) in Perth and Sydney, as well as with a group of Polish L2 speakers in Ireland. A quantitative analysis of the Chinese L2 speakers’ sociolinguistic interviews shows that their distribution of quotatives is dramatically different from native AusE speakers, primarily because of their overall low proportion of be like and their high proportion of quotative say and zero. The L2 speakers also show neutralization (no preference) for language-internal constraints, which have traditionally shown be like to be preferred in first person contexts and for reporting inner thoughts, differing from patterns for AusE observed in Perth and in a recent study of second generation Chinese Australians in Sydney.

1. Introduction

In 2008, William Labov discussed the advent of quotative be like, marveling at the lightning speed in which “the old way of using I say or He goes was replaced by I’m like and he’s like”, as well as at its geographical reach, stating that it “has penetrated as far as Australia” (cited in Buchstaller and Van Alphen 2012, p. xi). As Labov stated, quotative be like has rapidly become a dominant feature of the English quotative system, and scholars have been delving deep into its spread and use, especially among native speakers of English.

The use of quotative be like was initially thought of as a new phenomenon witnessed among a specific group of native English speakers (i.e., teenage girls in southern California (Butters 1982)). However, various studies conducted over time on Canadian, British, Irish, and Australian English (see Tagliamonte and Hudson 1999; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004; Tagliamonte et al. 2016; Diskin and Levey 2019) have shown that, in fact, the use of be like is not limited to a certain social group or geographic location, as shown in Table 1, and its usage frequency has been on the rise to rival (or even surpass) that of more traditional quotatives, such as say.

Table 1.

Use of quotative be like in different English varieties.

Buchstaller and Van Alphen (2012) note that this sudden rise of be like may be caused by the fact that new quotative variants such as be like are mostly “lexical items that denote comparison, similarity or approximation” (p. xiv). This, they claim, is a rather obvious choice for speakers as they rarely report speech verbatim, making any form of spontaneous oral quotation “nothing more than an approximation of the original speech act” (Buchstaller and Van Alphen 2012, p. xv; see also Buchstaller 2004). As studies also show that the use and prevalence of innovative quotatives is not a phenomenon restricted to one language group or geographic location, Buchstaller and Van Alphen (2012, p. xiii) state that the spread of innovative quotative variants raises important questions as to why speakers use such forms, as well as the potential universality of strategies for reporting speech cross-linguistically (see also Güldemann 2008).

Although there is a considerable amount of literature on quotative systems in native speaker discourse, the L2 acquisition of English quotatives and innovative variants such as be like remains relatively unexplored (with the exception of Davydova and Buchstaller 2015; Diskin and Levey 2019; Corrigan 2020; Davydova 2021). In efforts to address this gap, this study explores the acquisition of the English quotative system and, in particular, the innovative quotative variant be like among 14 Chinese L2 speakers of English of various language proficiencies and differing lengths of residence in Australia.

Our analysis highlights important issues in the acquisition (and learnability) of sociolinguistic variation (otherwise known as Type 2 variation—see Adamson and Regan 1991), which has been shown to be different from the acquisition of non-variable features. Quotative be like has been reported to have high sociocognitive salience and to be a “globally available variable linguistic feature” (Davydova 2021, p. 173). Its rise has also been reported to be one of the most rapid changes to occur in the English language (Tagliamonte et al. 2016), making it a good candidate for the study of the acquisition of variation. It is used at high frequencies within L1 communities, but potentially requires a certain degree of (socio)linguistic competence in order to be used in a ‘nativelike’ way by L2 speakers (see Diskin and Levey 2019). Furthermore, it has been adopted at different rates and time points by speakers of different varieties of English. This renders the quotative be like variant a ‘moving target’ (Meyerhoff and Schleef 2014), which poses even further challenges for the L2 speaker.

In the present study, the Chinese L2 speakers’ use of the English quotative system and quotative be like is compared with data from Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) study on the quotative system of native Australian English (AusE) speakers. We acknowledge that these datasets are not identical: ours was collected six years after that of Rodriguez Louro (2013). Be like has been shown to be undergoing rapid development, often in the space of just a few years (Tagliamonte et al. 2016), rendering our datasets not directly comparable. However, the fact that our data were collected in Melbourne, on the east coast of Australia, and the data in Rodriguez Louro (2013) was collected in Perth, on the west coast of Australia, does not, we believe, pose any major methodological issues. It has been widely reported that Australian English is relatively homogenous with regard to geographic differences (see e.g., Moore 2009) and that sociolinguistic variability is more likely to stem from differences in ethnic origin (Grama et al. 2020). In that vein, we note that in the present study, by ‘native’ AusE speakers, we refer to ‘mainstream’ AusE speakers, drawing on data in Rodriguez Louro (2013) and Tagliamonte et al. (2016) of Perth-born Australians from a corpus collected in 2011 at the University of Western Australia. There are more recent studies (see Rodriguez Louro and Collard 2021) that investigate the discourse–pragmatic variation of minoritized Englishes, such as Australian Aboriginal English.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

In the past few decades, a large volume of research on the English quotative system, and innovative forms such as be like (Blythe et al. 1990; Romaine and Lange 1991; Ferrara and Bell 1995; Tagliamonte and Hudson 1999; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004; Barbieri 2005; Buchstaller 2006; Buchstaller and D’Arcy 2009; D’Arcy 2010; Rodriguez Louro 2013; Diskin and Levey 2019), has been conducted within the variationist sociolinguistic paradigm, which studies social and linguistic constraints on variability of a particular linguistic feature (Tagliamonte 2006, p. 4). To gain a more accountable and systematic view of the underlying grammar of the quotative system as used by Chinese L2 learners in Australia, this study also follows the variationist sociolinguistic framework, which requires researchers to define “the variants of a variable and the context in which they vary” (Tagliamonte 2006, p. 13), allowing researchers to investigate “precisely how and where in the grammatical system a particular linguistic variable occurs” (Tagliamonte 2006, p. 86). The present study takes a quantitative approach to investigate “multiple linguistic internal and external factors” (Poplack and Tagliamonte 2001, p. 6) that condition the L2 learners’ quotative system rather than analyzing the usage rates alone.

2.1.1. Constraints Governing Be Like’s Use

Linguistic-internal and linguistic-external constraints play an important role in the analysis of be like’s diffusion and grammaticalization. Table 2 provides a brief overview of the internal and external constraints governing be like with examples and relevant references.

Table 2.

Internal and external constraints on be like.

For internal constraints, previous research on grammatical person has found that be like favors first-person subjects (Tagliamonte and Hudson 1999) across various Englishes, while say and go are strongly linked to third-person subjects (Blythe et al. 1990; Romaine and Lange 1991; Tagliamonte and Hudson 1999). For content of the quote, more recent studies (Buchstaller and D’Arcy 2009; Tagliamonte et al. 2016; Diskin and Levey 2019) have stated that across global varieties of English, be like has generally been associated with the expression of internal dialogue or inner thoughts, rather than the reporting of direct speech, or beyond that to include non-lexicalized sounds (mimesis). Mimesis is defined by Diskin and Levey (2019) as a speaker’s “manipulation of suprasegmental phonology (e.g., loudness pitch, syllable length) and/or sound symbolism to deliberately imitate or produce highly stylized renditions of human verbal behavior” (p. 60). However, mimesis is not reported on in the present paper.

Be like has generally been associated with the present tense as it allows the narrator to provide vivid and lively descriptions that the past tense cannot effectively convey (Meehan 1991; Biber and Conrad 2009; Rodriguez Louro 2013). However, some studies (Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2007; Buchstaller and D’Arcy 2009; Rodriguez Louro 2013) have shown inconsistent patterns regarding tense constraints on be like. While Buchstaller and D’Arcy (2009) note that be like favors the past and present tense in British English, speakers of American, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand English are said to favor be like with the historical present (HP) tense, which uses morphologically present forms while referring to past situations (Rodriguez Louro 2013, p. 53; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2007). As such, tense can be a factor to consider when distinguishing be like’s use among different Englishes.

For external constraints, be like has been largely regarded, at least in earlier work from the 1990s and early 2000s, as a ‘youth phenomenon’, strongly associated with the speech of teenagers and people in their early twenties (Blythe et al. 1990; Ferrara and Bell 1995; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004). However, since the majority of the Chinese L2 participants in the present study are of a similar age (ranging from 24 to 35), we do not explore the variable of age here. Meanwhile, in terms of speaker sex, there have been conflicting findings on whether quotative be like is preferred by speakers of a certain sex. Some studies have found be like to be preferred by a certain sex, but even within the same study, the preferences were different among various age groups (Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004; Barbieri 2005; Rodriguez Louro 2013). As such, sex is considered to be an unreliable predictor of the use of be like and is not considered in the present study.

2.1.2. Be Like’s Grammaticalization

Be like’s rapid penetration into the grammar is thought to be a case of grammaticalization in progress (Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004, p. 495). Grammaticalization is a “complex multifactorial type of language change” (Diewald 2011, p. 366) and has been defined as “a process leading from lexemes to grammatical formatives” (Lehmann 2015, p. v). It involves several co-occurring processes where older patterns become encoded in a new way or new linguistic patterns emerge (Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004, p. 496).

Tagliamonte and D’Arcy (2004) argue that be like is undergoing grammaticalization, as it exists simultaneously in the grammar with other quotatives such as say, go, think, etc., while canonical grammatical functions of the lexical form like, such as like as a verb, still exist (p. 496). As be like further grammaticalizes, Tagliamonte and D’Arcy (2004) predict that its use will generalize, broadening internal constraints governing the quotative (p. 496) and expanding its use to a wider range of content (i.e., to report direct speech) or subjects (third person). Numerous studies (Tagliamonte and Hudson 1999; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004; Rodriguez Louro 2013) have also predicted that be like’s grammaticalization will follow a similar transition path across varieties of English, with its use neutralizing for linguistic-external constraints such as speaker sex or age and expanding for linguistic-internal constraints such as grammatical person, content of the quote, and tense.

2.1.3. Be Like in Australia

Rodriguez Louro (2013) analyzed the linguistic and social factors constraining the use of quotatives in AusE among Perth youth, finding that Australian be like is subject to different constraints among different age groups. For example, be like was highly preferred above all other quotatives for speakers aged 11 to 26, but especially among pre-adolescent and adolescent girls (aged 11–16). However, in the young adult age group (18–26), be like was used more frequently by males to report direct speech. Meanwhile, be like was also found to be used frequently in the HP and with first-person subjects for both age groups.

Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) results contrasted with Winter’s (2002) study, showing a crucial shift in the linguistic choices of Australian youth within just one decade. Winter’s (2002) study, which took a form-based approach, meaning that it did not consider the internal (linguistic) or external (social) constraints on be like, examined the speech of 15 and 16-year-olds living in Melbourne. The study found be like to be the least frequently used quotative, while go was the most favored quotative, followed by say and zero. Winter (2002) concluded that the Australian quotative system had expanded to include be like, but its use was still limited. The study also noted that be like was “largely conditioned to third person singular use” (Winter 2002, p. 20), which contrasts with Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) results.

Recent results from Travis and Kim (2021) show that young adults in Sydney born in the 1990s (and recorded in the 2010s) use be like 70% of the time, whereas the previous generation studied by the authors, born in the 1970s, preferred quotative go (and their parents’ generation preferred say). The young speakers in the 2010s replicated the linguistic conditioning for be like found in Rodriguez Louro (2013): be like is preferred in the HP, with first-person subjects, and to report inner thoughts. Interestingly, the linguistic constraints on person and quote type were more significant for Chinese Australians (second generation migrants of Cantonese background) than for Anglo or Italian Australians, where these linguistic constraints had neutralized. Maintaining these linguistic constraints on be like was described by Travis and Kim (2021) as “conservative”. Overall, these three previous studies of be like in AusE suggest that be like has been on the rise in the variety for quite some time and has overtaken go and say as the quotative variants of choice in AusE.

2.1.4. Be Like and L2 Learners of English

In recent years, research on quotative be like has expanded to include L2 English speakers and their acquisition of the English quotative system and innovative forms. Although some recent studies have focused on quotatives in non-native and indigenous forms of English (i.e., English used in Singapore, Hong Kong, the Philippines, and India; see D’Arcy 2013; Davydova 2015), it has been claimed by Davydova and Buchstaller (2015) that there is still very little known about the ways quotative be like is acquired by L2 learners of English.

Davydova and Buchstaller’s (2015) study on German L2 learners of English in Germany showed that high-exposure learners who had two or more visits to an English-speaking country (amounting to a cumulative seven months’ time abroad per respondent) were much more successful in acquiring be like, as compared to low-exposure speakers who had between zero and two visits abroad. The high exposure learners displayed a quotative system that closely resembled North American native speaker patterns. The data provided evidence that exposure to native English in a natural setting was a key factor, which prompted the authors to claim that extensive face-to-face contact with native English speakers is required for the acquisition of vernacular forms such as be like.

Davydova’s (2021) study further explains how be like is acquired similarly across different L2 communities (Indian and German learners of English) by virtue of its sociocognitive salience: be like spreads due to its use being above the level of conscious awareness (p. 171) and presenting a “moderate” and “tolerable” cognitive load on L2 learners (p. 190). Furthermore, Davydova (2021) finds that, despite be like spreading via diffusion, which often re-organizes original patterns, in the case of be like, there is a “generally accurate reconstruction” of the patterning of its constraints among both the Indian and German groups (p. 175). We note, however, that Davydova (2021) does not systematically compare the output of her targeted Indian and German speakers with an actual community-based variety of English that these speakers have been putatively exposed to, which is a gap that our present study attempts to fill.

Corrigan (2020) also discusses the acquisition of sociolinguistic variation and the distribution of quotative systems among Lithuanian and Polish newcomers in Armagh (Northern Ireland) but notices stark differences between all groups with only the Lithuanian group sharing the L1 preference for be like as the majority quotative at 36.6% (p. 301). The Lithuanian migrants also had a high propensity for ‘other’ quotatives at 18.4%, whereas native speakers tend to divide their quotatives across be like, say and zero (Corrigan 2020; see also Diskin and Levey 2019).

Diskin and Levey (2019) discusses the acquisition of quotative variation patterns by Polish-born L2 speakers in Dublin, Ireland, hypothesizing that a speaker’s level of English proficiency can be a major factor in acquiring native-like constraints. The results showed that there were significant differences between the upper and lower proficiency groups, which were divided based on a cumulative proficiency index (CPI), factoring in the participants’ self-rated proficiency in English, age of onset, and their preferred language to read the project information sheet and consent form (English vs. Polish). The results indicated that level of English proficiency, measured via a CPI, is a key factor in acquiring target-language patterns of quotative variation and change (Diskin and Levey 2019, p. 73).

2.2. Research Questions and Predictions

Compared to the wealth of research on quotative variation and change in native English varieties, learner Englishes is an area that has yet to be explored thoroughly. Meanwhile, even studies on native English varieties have mostly focused on North American and European varieties of English, with only a handful of studies focusing on the quotative system of AusE to date. As such, this study aims to address the gap by investigating the acquisition of quotatives, and particularly innovative forms such as be like, by Chinese L2 learners of English in Australia. This investigation is compared with a native AusE benchmark from Rodriguez Louro (2013). In doing so, the present study raises the following research questions:

- Do Chinese L2 speakers of English in Australia follow AusE patterns of distribution in the use of quotatives?

- Have Chinese L2 speakers of English in Australia acquired innovative quotative forms such as be like?

- If so, how does their use compare with native AusE speakers?

- Does the L2 speakers’ English proficiency level and length of residence play a role in their use of quotative be like?

Predictions are that Chinese L2 speakers of English will have a different overall distribution of quotatives compared to AusE speakers, as they may not have fully acquired quotative be like. Therefore, in contrast to AusE speakers and L1 speakers of other English varieties, be like will not be one of the most frequently used quotatives for the Chinese L2 group. Furthermore, as the Chinese L2 speakers will have been exposed to native AusE in their daily lives, linguistic-internal constraints, with be like being favored with the HP, first-person subjects, and internal thought (Rodriguez Louro 2013), are expected to emerge, but not be faithfully replicated, among the L2 group as compared to the native AusE (L1) group. We explain this via the hypothesis that, in this context, acquisition is occurring via diffusion (“weakening of the original pattern and loss of structural features”) rather than transmission (“a faithfully reproduced pattern”) (Labov 2007, p. 344). This is a phenomenon shown to have occurred in other contexts of L2 acquisition of L1 variation (e.g., Drummond 2011; Meyerhoff and Schleef 2014; Schleef 2017; Diskin and Levey 2019; Davydova 2021). Finally, in line with the findings of Diskin and Levey (2019), if Chinese L2 learners are found to be using quotative be like, it is predicted that it will occur more frequently among higher-proficiency L2 learners with a longer length of residence in Australia.

2.3. Data Collection and Participants

The data used in this study consist of a collection of sociolinguistic interviews recorded by the second author (a native Irish English speaker) and an AusE-speaking collaborator in 2017 with 14 Chinese L2 speakers of English residing in Australia. All of them were university students or recent graduates. Seven males and seven females took part, with sex being self-identified by the participants in a demographic questionnaire using the choices ‘male’, ‘female’ or ‘prefer not to say’. As shown in Table 3, their ages ranged from 24–35 years (mean age: 27) and their length of residence (LoR) ranged from 5 months to 7 years and 4 months (88 months), with a mean LoR of just under three years (34.43 months). Their English proficiency ranged from an IELTS band score of 6.0 (competent) to the highest of 9.0 (expert), with a mean score of 7.5.

Table 3.

Participant profile.

All the participants, with the exception of three (021M, 027M, and 032M), had a very similar educational history: they had completed high school and undergraduate studies in China before coming to Australia to pursue postgraduate degrees. For these 11 participants, their main exposure to English had been within the formal education system and none of them reported any time spent overseas before they came to Australia. Some of them had taken subjects in linguistics, English language, and/or translation as part of their undergraduate degrees in China. To move to Australia for postgraduate study requires completion of an IELTS test, often with a minimum score of 6.5 for entry to institutions such as the University of Melbourne. Meeting these minimum scores can often require extensive preparation and English study, which a number of the participants reported. The other three participants had come straight to Australia after finishing high school in China and completed their undergraduate degrees in Australia. They had among the longest LoRs and highest IELTS scores in the group and reported more opportunities to have learned and practiced English in informal settings.

The data were collected on the campus of the University of Melbourne in 2017 as part of a larger research project conducted by the second author on migrants’ acquisition of a new language or dialect when moving to a new country (see Diskin et al. 2019). To take part in the study, the participants had to be aged 18 or over, be born in China, and speak Chinese (Mandarin) as their first language. Of the fourteen participants reported on here, all of them listed “Chinese”, “standard Chinese” or “Mandarin” as their native language. Two participants added to their answers that they were speakers of Wu and Henan dialects; one self-reported as bilingual in Mandarin and Cantonese. They had to have come to Australia in 2007 or later as adults and have English proficiency equivalent to at least IELTS band 4 (limited user; IELTS n.d.).

To obtain naturally occurring speech that can “provide examples of variation for use as evidence for linguistic change” (Becker 2013, p. 107), the participants took part in a studio-recorded, semi-structured sociolinguistic interview based on questions by Llamas (1999) and Tagliamonte (2006), which lasted 30 to 50 minutes. Participants were asked questions about topics they were familiar with, involving their work, study, family, experiences in Melbourne, current living situation, travels, etc. (Appendix A) The participants were also asked about their thoughts on life in Australia, and about accents and speech. Each interview was transcribed orthographically by paid research assistants using the annotation software ELAN (2017).

As the participants were residing in Australia at the time of the interview and had mostly been exposed to AusE, Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) study of Australian youth was used as a benchmark for comparison of their use of quotatives. In line with previous literature that discusses speaker sex as a variable influencing the use of quotatives (see Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004; Barbieri 2005; Rodriguez Louro 2013), speaker sex is recorded, but not analyzed as a factor here. Age was not recorded as a factor, as most participants were in their mid-20s.

To determine if level of English proficiency was a factor constraining the use of be like, participants were divided into two proficiency groups: a lower proficiency group, who had an IELTS band score of 6.5 or lower (N = 4), and an upper proficiency group, consisting of participants who scored IELTS 7 and above (N = 10). The rationale for this cutoff point was that in the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), IELTS scores of 6 or 6.5 are B2 level and in the category of “independent user”, whereas IELTS scores of 7 and above mark the transition into the CEFR C1/C2 category of “proficient user” (Information about the IELTS Test n.d.).

As length of residence (LoR) in an English-speaking country may increase the likelihood of exposure and acquisition of be like, participants were also divided into two LoR cohorts: ≤24 months (N = 5) and ≥24 months (N = 9). As shown in Table 4, there was some, but not complete, overlap between low proficiency and short LoR and high proficiency and longer LoR.

Table 4.

Distribution of participants by LoR and proficiency.

2.4. Linguistic-Internal Constraints

To increase comparability with results from earlier research on quotative variation and change, the following linguistic-internal constraints were included in the analysis: grammatical person, content of the quote, and tense.

For grammatical person, the study distinguishes first-person from third-person contexts in line with previous research (Blythe et al. 1990; Tagliamonte and Hudson 1999; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004; Rodriguez Louro 2013) which states that be like is preferred with first-person subjects (as used in 1a) and say with third person subjects (1b). Tokens of existential ‘it’ constructions (i.e., it + be like) were also coded separately for analysis if they reported speech or thought, as in 1c, while tokens of like without a copula (‘be’) as in 1d, were classified separately as discourse marker (DM) like.

| 1. | a. | I was like, “you know what, they don’t even care about me I just, I’m just gonna say no” (032M, 21:17) |

| b. | because uh he said, “oh you couldn’t do anything if I- I- if I don’t stop” (004F, 23:11) | |

| c. | it’s so good, and you just keep eating it and some bloating as well, and it was like, “uhh” (.) <LAUGHTER> yeah (032M, 20:45) | |

| d. | like “go to the” <PUTS ON ACCENT> the kind of [like?] the, the, the thingy? That is, probably from, the southern part (032M, 24:04) |

For content of the quote, tokens that introduced reported speech (2a) and internal dialogue or inner states (2b) were differentiated, as in previous studies (e.g., Buchstaller and D’Arcy 2009; Tagliamonte et al. 2016).

| 2. | a. | and she’s like, “oh if you go outside, spent too mu- mingle too much with local students you might (.) become bad” or something like that (032M, 01:10) |

| b. | um, that was in high school, I was like, “okay I’m just gonna try it cause I heard so much about it” and I went for it, (032M, 13:47) |

Tense is considered to be one of the stronger predictors for quotative choice, despite inconsistent effects across English varieties (Buchstaller 2014, p. 110). Rodriguez Louro (2013) noted that the HP was the most frequent tense used with be like, while Winter (2002) also found that the HP “correlates strongly with quotative be like” (p. 11) in AusE. As such, the data were coded for past tense (3a), HP (3b), and present tense (3c).

| 3. | a. | I have different feelings for her now but back then, I was like (.) “he’s my first enemy” (015F, 15:57) |

| b. | and I think, in the beginning, I just, I go, “okay okay” they’re like, “dip, dip”, I was like, “okay” uh <LAUGHTER> (032M, 21:10) | |

| c. | I always- i- i- in my mind it’s like, “okay maybe I should use ‘mate’, so they think I’m quite Australian” (021M, 49:56) |

The coding process followed several steps. Firstly, all instances of reported speech or thought were coded in a thorough and careful read-through of the transcribed material. Secondly, all tokens were cross-checked with the actual recorded data to make sure the transcription was accurate, to further code the linguistic factors (i.e., grammatical person, tense, and content of the quote), and to identify zero quotatives, or instances when a quote is introduced without a quotative by using voice modulation or some other non-verbal indication that the speaker is introducing a quote, in what Buchstaller calls “unframed quotes” (2006, p. 5). It is often denoted with the “Ø” symbol in the literature, as in 4.

| 4. | I very quickly moved to Ø: “I don’t wanna do this anymore”. (Rodriguez Louro 2013, p. 50) |

A total of 216 quotative tokens were identified among the L2 speakers, which were then compared with 840 tokens from AusE speakers in Rodriguez Louro (2013). The quotative tokens were further analyzed using descriptive statistics to find the sum of all quotative tokens for each participant and for each quotative variant, and the proportion of each quotative variant used by each participant. These figures were compared with the frequency distribution of quotatives used by native AusE speakers from Rodriguez Louro (2013) and with Polish L2 English speakers in Diskin and Levey (2019) to compare acquisition among different L2 groups. Meanwhile, descriptive statistics also helped to analyze the proportion of tokens for each linguistic constraint (i.e., grammatical person, content of the quote, and tense) that was coded for in the data.

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Quotatives

The overall distribution of quotatives found in the corpus of the 14 Chinese L2 English learners was compared to Rodriguez Louro (2013), which looked at the spontaneous conversations of 47 native AusE speakers (22 women, 25 men) in Perth with ages ranging from 11 to 63. The results are shown in Table 5 and are broken down by the age groups in Rodriguez Louro (2013). (Rodriguez Louro (2013) did not code for DM like or quotative feel in her data, thus they have been marked as n/a in the table).

Table 5.

Distribution of quotatives in the Chinese L2 corpus compared to Rodriguez Louro (2013).

Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) 18–26 age group is the most comparable with the Chinese L2 participants, who were mostly in their mid-20s except for two participants (003F, 004F) who were in their 30s. Among AusE speakers, the use of be like was especially notable among younger speakers, particularly in the 11–16 and 18–26 cohorts, with the highest number of be like tokens (278; 79.4%) found among the 11–16 age group, and be like being used at the highest frequency (81.5%) among the 18–26 age group. These numbers differ dramatically from our Chinese L2 speakers, despite the similarity in age, who used be like just 7.4% of the time.

For the AusE 18–26 age group, be like (81.5%) and say (8.4%) were the two most frequently used quotative variants, followed by think (3.7%) at a distant third. In line with Buchstaller and D’Arcy (2009, p. 320), Rodriguez Louro (2013) has explained the decrease in the frequency of think in apparent time in her data by people choosing to use be like instead of think to express inner thoughts (p. 60). In other words, she claims that think is in direct competition with be like and has been overtaken by be like for reporting inner thoughts.

In the L2 corpus, think was the third most frequently used quotative, amounting to 7.4% of the total, with a noticeable lower frequency compared to second place zero (25.9%) and the most frequent quotative, say (34.3%). However, it remains to be seen whether think was in direct competition with be like for reporting inner thoughts among the L2 speakers, as the two variants had the same number of tokens (N = 16).

Half of all be like tokens (N = 8) in the L2 corpus were used to report inner thoughts (see Section 3.4.1), which could indicate that they were being used in a similar way to quotative think, which can only be used to report inner thoughts. The use of be like was also concentrated among a small number of participants (N = 4), while think was used among a slightly higher number of participants (N = 6). This makes it difficult to assess whether the L2 speakers were really using be like in favor of think (7.4%). Nonetheless, among the four participants who used be like, their frequency of think was mostly nonexistent or very low (only one participant, 030M, used it once), which could indicate that they were using be like instead of think. To shed further light on these issues, Table 6 provides a breakdown of the frequency of quotatives used by each Chinese L2 participant.

Table 6.

Comparison of quotatives used by each participant in the Chinese L2 corpus.

In Table 5 and Table 6, we note that quotatives with token numbers of less than four were grouped together under ‘other’, except for go, which is displayed separately for comparative purposes, due to its prevalence in the AusE data (Rodriguez Louro 2013). Quotative tell includes tell + that and be includes is, it is, and it isn’t. Quotatives in the ‘other’ category include semantically richer quotatives, or “graphic introducers”, which function as an evaluative device to describe elements in oral narratives (Labov 1972 cited in Tannen 1986, p. 322). Tannen (1986) defines these as any verbs other than say, tell, think, ask, go or be like (p. 322). In the present study, the ‘other’ category included the following: know (N = 1), speak (N = 1), ask (N = 3), write (N = 1), find (N = 2), pronounce (N = 2), wonder (N = 1), call (N = 2), believe (N = 2), answer (N = 2), and mean (N = 1). The presence and variety of these graphic introducers could be an outcome of the formal education settings in which the participants learned English (Section 2.3) as they tend to be more common in written rather than spoken English.

Quotative feel, as in (5), was well-represented in the L2 data at 4.2% of quotatives used. In our coding schema, quotative feel also includes the “transitional” (Macaulay 2001; Buchstaller 2008, p. 30) quotative form feel + like’.

| 5. | I can’t understand but I felt “oh, it’s so touching,” and I was very nervous and I stood up, and raised the Coke (016F, 36:18) |

Feel was not part of the native AusE quotative system documented by Rodriguez Louro (2013) and it was also not included in her miscellaneous ‘other’ category. Unlike native AusE speakers, Chinese L2 learners were, to a certain extent, using feel to report inner thoughts (perhaps in the place of be like) which could also have affected their frequency of quotative think. The reason why L2 speakers were using feel to express inner thoughts and whether it is in competition with think or be like would naturally require confirmation through further research with a larger dataset.

Overall, L1 influence is another future issue to be addressed, as recent studies such as Yang (2021) show that gǎnjué ‘feel’ and juéde ‘think’ are highly frequent in Mandarin conversation and have a stance-taking function. This may have influenced the frequency of use of feel and think as quotatives by the Chinese L2 learners in the present study. Furthermore, Mandarin Chinese does not have an equivalent of the be like quotative and tends to rely on quotatives such as shuō (说) ‘say’ (Le 2013, p. 106), biǎo shì (表示) ‘express/indicate’ (Zhang 2020, p. 24) or wèn (问) ‘ask’. This means that the acquisition of quotative be like could present more difficulties for Chinese learners of English than learners with an L1 that has a be like equivalent (see Buchstaller and Van Alphen 2012).

Chinese L2 learners were also found to be using like without a copula (‘be’) to introduce direct speech, as in (6). Here, like is a DM, functioning as an exemplifier to introduce an example (see Diskin 2017, Diskin-Holdaway 2021), but at the same time, the example introduced is what someone else has said. As such, like is functioning both as a DM and as a quotative.

| 6. | yeah, and like uh “how you going today?” (017F, 22:42) |

Diskin and Levey (2019) distinguish DM like (p. 66) as a separate quotative variant from be like in their corpus of native Irish English (IrE) speakers. They report that DM like amounted to approximately 6% of the 222 quotative tokens found in their corpus of six IrE speakers, compared to 25% for be like. In other words, DM like was used approximately once every four times be like was used among native IrE speakers. The usage rates for be like (7.4%) for the Chinese L2 corpus analyzed here are lower but are similar for DM like as compared to native IrE usage at 5.1%. The AusE data could not be directly compared with the Chinese L2 data as Rodriguez Louro (2013) did not look at DM like as a separate quotative variant, and the variant was also not included in her ‘other’ category, which included write, ask, yell, tell, read, scream, and realize.

Nonetheless, the relatively high rate of DM like among the Chinese L2 group, especially in comparison to their use of be like, may be due to the fact that DM like could be easier to acquire for non-native speakers. This is supported by the fact that even lower proficiency speakers (017F, 019F) were using it as a quotative. Furthermore, Diskin-Holdaway (2021) found that, with a different cohort of Chinese migrants residing in Ireland, their acquisition of DM like did not differ in terms of frequency as compared to the L1 (Irish English) benchmark. In the present study, since 032M, who had the longest LoR and was part of the higher proficiency cohort, was the only one to use both DM like and quotative be like frequently, we cautiously propose that the acquisition of DM like may have occurred ahead of quotative be like for these speakers.

3.2. Comparison between Chinese L2 and Polish L2 Groups

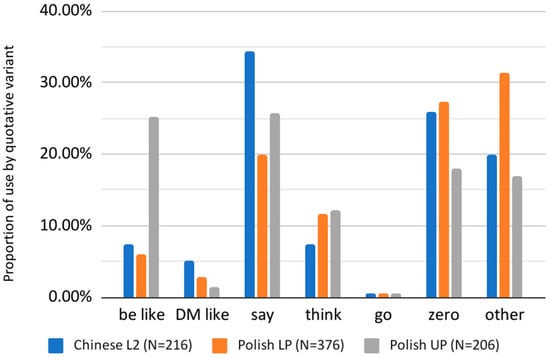

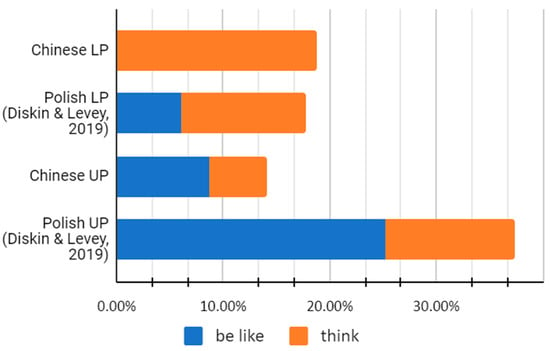

To compare quotative acquisition among different L2 groups, the Chinese L2 data were compared with Polish L2 English speakers in Ireland from Diskin and Levey (2019). As the two studies were commensurate in data collection method and participants, a comparison of quotative distribution is expected to provide a robust comparison of what kind of quotative choices L2 English learners are making when reporting speech or thought. Figure 1 shows a comparison of the most frequently used quotatives among the Chinese L2 learners and Diskin and Levey’s (2019) Polish L2 speakers, who were divided into two proficiency groups: upper (Polish UP) and lower (Polish LP).

Figure 1.

Quotative distribution among L2 groups (Chinese L2, upper and lower proficiency Polish L2 groups).

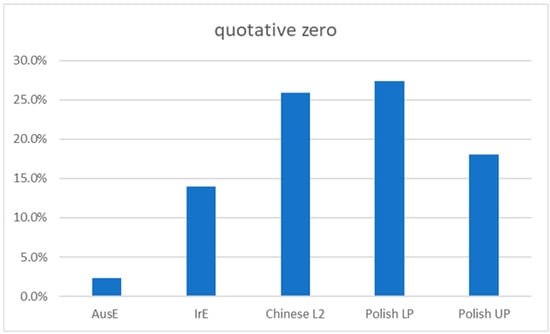

As shown in Figure 1, there was a high frequency of use for the zero quotative among all L2 groups. Similar to the Chinese L2 learners, where zero accounted for 25.9% of all quotatives, Polish L2 learners, and in particular the lower proficiency group (Polish LP), show a high proportion of the zero quotative (27%), which is in sharp contrast to the frequency of zero quotatives for native AusE speakers (2.3%; Rodriguez Louro 2013) and still higher than native IrE speakers (14%; Diskin and Levey 2019) as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Frequency of quotative zero among two NS (AusE and IrE) and three L2 (Chinese L2, Polish Lower and Upper Proficiency) groups.

Diskin and Levey (2019) explain the disproportionate representation of the zero quotative, which occurred at nearly double the rate for the Polish LP group compared to the native speaker group (IrE), as a strategy used by L2 speakers to avoid some of the difficulties of selecting a “verb in the quotative frame which typically requires speakers to attend to grammatical person and number, tense and aspect as well as (irregular) verb morphology” (p. 69). In other words, as the zero quotative, argued to be a universal quotative option (Güldemann 2008), mostly relies on voice modulation rather than syntactic aspects to differentiate speaker voices, it may be an efficient strategy for lower proficiency speakers when reporting someone else’s speech or thought.

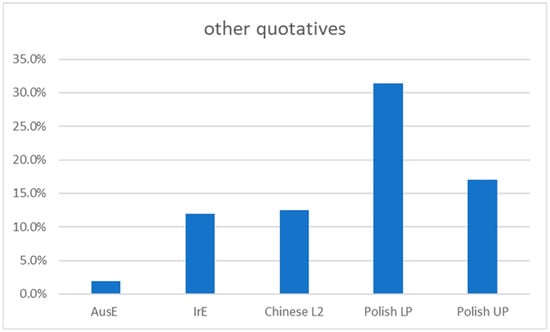

Meanwhile, the ‘other’ category accounted for 12.4% of the Chinese L2 learner corpus, which was much larger than the proportion of ‘other’ quotatives (1.9%) for native AusE speakers from Rodriguez Louro (2013). Figure 3 shows a comparison of the ‘other’ category between native speaker groups and L2 groups from Rodriguez Louro (2013) and Diskin and Levey (2019).

Figure 3.

Comparison of ‘other’ quotative frequency among two NS and three L2 groups.

It is of note that the Chinese L2 corpus had a similar frequency of ‘other’ quotatives to native IrE speakers and upper-proficiency Polish L2 English speakers in Diskin and Levey (2019). This may be because the participants in the Chinese L2 corpus were mostly highly proficient English speakers with a mean IELTS score of 7.5. Only four out of 14 participants had scores lower than IELTS band 6.5, and the lowest score was 6.0, which is still considered to be a “competent user” (IELTS n.d.). This can go some way to explaining why their patterns of use of ‘other’ quotatives resemble that of native speakers and other high proficiency L2 speakers. Further, it has already been noted in Section 3.1 that the presence of these semantically richer ‘other’ quotatives could be an outcome of the formal education settings in which the participants learned English. Conversely, the overall low rates of ‘other’ quotatives in the AusE corpus (Rodriguez Louro 2013) could be explained by the fact that the corpus has a high proportion of informal speech and narratives, where quotatives such as be like or say may be preferred.

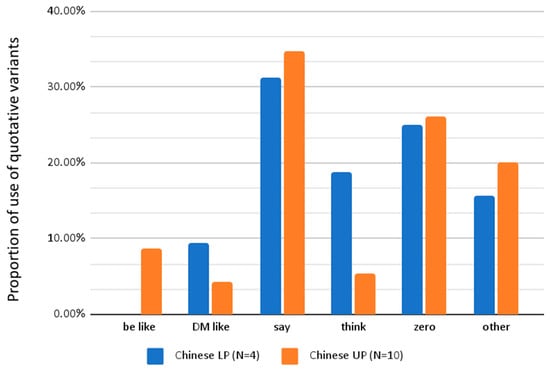

3.3. Comparison between Proficiency Levels for L2 Groups

The participants in this study were divided into upper (UP) and lower proficiency (LP) groups based on their IELTS scores (see Table 4 in Section 2.3). Figure 4 shows the distribution of the most frequently used quotative variants by participants in the L2 Chinese corpus according to their respective proficiency groups.

Figure 4.

Comparison of most frequently used quotative variants by proficiency group in the Chinese L2 corpus.

As shown in Figure 4, the two proficiency groups (LP and UP) had similar proportions of quotatives, apart from think and be like, with think being favored by the LP group and be like by the UP group (there were no tokens of be like in the LP group). As mentioned in Section 3.1, the higher frequency of think in the LP group may have been because they did not use be like to report inner thoughts. This becomes more evident when comparing the Chinese and Polish L2 groups (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison of be like and think among lower proficiency (LP) and upper proficiency (UP) speakers in the Chinese and Polish L2 corpora (Diskin and Levey 2019).

The UP groups for both Chinese and Polish L2 learners show similar proportions for the two quotatives, where be like is used slightly more than think. Meanwhile, between the two LP groups, the proportion of think is lower for the Polish LP group, which uses some be like, compared to the Chinese LP group, which does not. It is difficult to make direct comparisons, as the Chinese LP group did not produce any be like tokens; however, the results could indicate that even among L2 speakers, think could be in direct competition with be like (Rodriguez Louro 2013, p. 60), similar to the trend noticed in native English speakers.

3.4. Quotative Be Like among Chinese L2 Learners

Taking a closer look at quotative be like’s use among Chinese L2 learners, only four out of the total 14 participants produced tokens of be like (Table 7).

Table 7.

Profile of participants who used be like.

When comparing the total number of be like tokens among the four participants, the majority (N = 15) were found among males, compared to just one token produced by a female (015F). Although 032M had the highest raw number of be like tokens (N = 10), 021M had a higher proportion of be like (25%) in the quotatives he used as compared to 032M (20.4%). It is of note that these two participants were in the exceptional position of having moved to Australia straight after high school (see Section 2.3), resulting in prolonged exposure to AusE in naturalistic settings.

In terms of proficiency, Diskin and Levey (2019) points out that higher proficiency speakers are more successful in “approximating L1 patterns of be like use, as gauged from overall rates and variant use as well as the conditioning of variant choice” (p. 72). In line with Diskin and Levey’s (2019) results, none of the participants in the lower proficiency group (IELTS band 6.5 or lower) used quotative be like in their speech—all participants who used be like were in the higher proficiency group. Furthermore, in line with earlier predictions that participants who have a longer length of residence (LoR) will be more likely to use be like, all but one participant (030M) who used be like had been living in Australia for at least 32 months.

3.4.1. Linguistic-Internal Constraints

Table 8 compares the distribution of constraints for be like with those of the two most frequently used quotative variants in the data: say and zero. (We note that n/a has been used in the table for quotative zero, which cannot encode grammatical person or tense. Furthermore, five tokens of say that had an impersonal ‘you’ subject were excluded from the grammatical person category).

Table 8.

Distribution of language-internal factors conditioning the distribution of be like among Chinese L2 speakers.

Out of a total of 16 tokens of be like in the data, there was an equal or near equal distribution of use for content of the quote and grammatical person. In other words, be like was used at similar frequencies to report direct speech and inner thought, while there was also an even distribution for first person (e.g., I, we) and third person subjects (e.g., she, they) as well as existential ‘it’ (7). This tentatively suggests that the constraints on person and content of the quote were neutralized among the four Chinese L2 speakers who used be like.

| 7. | yeah, so, yeah i- it’s like, “okay we get it, this is [serious-?] it works like this you don’t need to explain like four times to us” (021M, 42:00) |

The results contrast with Rodriguez Louro (2013), which shows that among 18 to 26-year-old AusE speakers, be like is preferred with first-person subjects and to introduce direct speech (p. 66). This aligns with the preference for first-person subjects with be like found in Travis and Kim (2021) for Chinese Australians, but not for their findings for content of the quote, where they found internal dialogue to be favored with be like.

The results for tense constraints among the Chinese L2 speakers show favoring for be like with the past tense. This also contrasts with Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) data, which showed HP ranking first, followed by past and present tense among native AusE speakers aged 16 to 28. Tense was not examined in Travis and Kim (2021).

Overall, the constraints on Chinese L2 learners’ use of be like are more neutralized as compared to Rodriguez Louro (2013), with an even percentage of use of each constraint factor across the board, although very low token numbers (N = 16) preclude us from making any generalizations. This is corroborated by the neutralization of language-internal factors found for Australians of Anglo and Italian background in Travis and Kim (2021), but not by their findings for Chinese Australians, whom they described as “conservative” in their quotative behavior. Our L2 learners do not appear to be mirroring this ‘conservative’ behavior with respect to the constraints on be like, although their overall quotative use is indeed conservative in the sense that there is a broad preference for quotative say—the prototypical variant transmitted to learners in classroom environments—and quotative zero, which has been described as a universal option for reporting speech (Güldemann 2008).

With regard to constraints on quotatives say and zero, Table 8 shows that among Chinese L2 learners, a majority of say (95.9%) and zero (82.1%) quotatives were used to express direct speech, while be like was dispersed more evenly between the expression of inner thoughts (50%) and direct speech (50%). In terms of a comparison with an L1 benchmark, this behavior corroborates findings for quotative say and zero from Diskin and Levey (2019) for Irish English, but Rodriguez Louro (2013) did not examine these constraints on say and zero in AusE. Meanwhile, for grammatical person, of the total say quotatives, 70.3% was used for third person subjects, similar to L1 English speaker patterns reported in Blythe et al. (1990), Romaine and Lange (1991) and more recently in Diskin and Levey (2019). However, Tagliamonte and Hudson (1999) noted that among their British and Canadian participants, the two groups differed, with say preferring first person among Canadian English speakers and third person among British English speakers (p. 161). Overall, the Chinese L2 speakers in the present study appear to be mirroring constraints on quotative say and zero from L1 speakers of American English and Irish English.

3.5. Analysis of Individual Lower and Upper-Proficiency Speakers

The quantitative results shown above provide a broad view of the overall quotative system for Chinese L2 English learners in Australia. As speaker proficiency and length of residence (LoR) emerged as two social factors influencing the use of be like in the data, this paper will now focus on two participants for further analysis. One participant will be from the high proficiency group with longer LoR (participant 032M) and one will be from the lower proficiency group with shorter LoR (participant 019F).

3.5.1. Upper Proficiency Speaker 032M

Participant 032M stood out in the data as he had the longest LoR (88 months), which was much higher than the mean LoR (34.43 months). He was also the only participant who had attended high school in Australia and had over six years of education (two years of high school and four years of university) at Australian educational institutions. This meant he had come to Australia at an earlier age (i.e., at 17), compared to the rest of the group who had arrived in Australia past the age of 20, with the exception of 021M, who had arrived at 18.

Participant 032M was an outlier, in the sense that he produced the largest number of quotative be like tokens (N = 10) in the data, which amounted to 62.5% of all be like tokens (N = 16) produced in the corpus. Individually, be like amounted to 20.4% of 032M’s total quotative tokens. He also displayed robust usage of quotative say and zero (see Table 6). Age of onset (or perhaps more accurately: age of immersion in an English-speaking environment) was not a factor that was originally considered in the research design of this study. All participants had arrived in Australia past the age of puberty and there was little variation among participants, with only two participants arriving before the age of 20 as compared to the remaining participants who had arrived in Australia between the ages of 21 and 28. However, as 032M was exposed to native AusE at a relatively younger age compared to the other participants, and his use of be like stood out in the data, we can cautiously suggest that age of onset/exposure may be an important factor influencing the acquisition of quotatives and quotative be like in particular. Meanwhile, considering that 032M (and 021M) had a longer LoR compared to other participants, coupled with higher proficiency, more research would be needed to determine whether the age of onset, proficiency, and LoR are collinear.

Due to his long LoR and high proficiency, 032M was also unique in using quotative variants that other participants did not use, but which were found in Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) data. For example, 032M was the only participant to use quotative go, as in example (8), although this was just once.

| 8. | and I think, in the beginning, I just, I go, “okay okay” they’re like, “dip, dip,” I was like, “okay,” uh <LAUGHTER> (032M, 21:10) |

Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) findings also document the use of go among native AusE speakers, which amounted to 4.2% of the overall distribution of quotatives and 1.3% among the 18–26 age group. Participant 032M was also among the few participants who used quotative be (example 9), also reported in Rodriguez Louro (2013).

| 9. | that is “ohhhhh my god” <LAUGHTER> kind of thing, and I- I think have a little bit of that, I will have a conversation, but um (.) in terms, as for, having a relationship? it really depends on, what that situation what the circumstances, yeah (032M, 39:03) |

In Rodriguez Louro’s (2013) overall distribution of quotatives, quotative be takes up 1.4% for all age groups and 3.4% for the 18–26 age group, whereas 032M’s use of be amounted to 2.04% of his overall quotative distribution.

3.5.2. Lower Proficiency Speaker 019F

We now take a closer look at 019F from the lower proficiency group, who had scored a 6.5 on her IELTS and had been living in Australia for 22 months. In comparison with 032M, a difference in proficiency is noted, which was also noticed in her interaction with the interviewers. Throughout the interview, 019F needed some questions to be repeated or rephrased as she did not understand what the interviewers were asking. Furthermore, incorrect grammatical forms (e.g., verb inflections) emerged frequently in her speech.

In 019F’s quotative distribution, there was a near equal distribution of zero (N = 4), say (N = 4) and think (N = 4) which each amounted to 23.5% of the total number of her quotative tokens (N = 17). Although she did not use quotative be like, she used DM like (11.8%), tell (11.8%), and pronounce (5.9%). Compared to the other three participants in the lower-proficiency group, she had the highest number of total quotative tokens and was the only one to use tell (or tell + complementizer ‘that’) to report speech or thought.

Indeed, although 019F had a higher number of quotatives compared to others in the lower-proficiency group, she still reported speech or thought using indirect quotes with complementizer ‘that’, which is a common way of reporting speech or thought taught in EFL contexts (Barbieri and Eckhardt 2007). The frequent use of indirect quotation was also noted among other lower proficiency speakers, such as 018F, with most of the lower-frequency group having less than 10 quotatives per person (N = 3 for 018F; N = 5 for 017F; N = 7 for 026M).

Looking at the use of indirect quotations in more detail, it seemed 019F did not have full competence in reporting speech or thought both directly and indirectly. In 10a, she uses complementizer ‘that’ to report what someone else has said indirectly. However, in 10b, she also uses complementizer ‘that’ to report what someone has said directly. The direct speech is characterized by a shift in pitch, indicating mimicry of her teacher’s voice. Meanwhile, in 10c, she begins by using say to reconstruct a dialogue with her parents, in what appears to be a reporting of direct speech: “if you really do want to do that”. However, as she follows this with “they will support me”, the grammatical person switches from ‘you’ to ‘me,’ and the utterance turns into an indirect report of what was said.

| 10. | a. | and they told me that mm it seems like from her point of view? what we have done is on the right track. (019F, 05:47) |

| b. | but mm. they told me that <HIGHER PITCH> “why do show me that. I don’t tell you do the an- competitor analysis”. (019F, 05:09) | |

| c. | but they said “if you really do want to do that” they will support me. (019F, 27:35) |

Although example 10 does not provide a complete view of 019F’s quotative system and what she has acquired, we can infer that she does not have full mastery in reporting strategies for direct speech, and, as an alternative strategy, uses complementizer ‘that’ accompanied by voice modulation indicating direct speech. This is a strategy that has not, to the best of our knowledge, previously been documented among native speakers.

Finally, although 019F did not use quotative be like, she did use DM like to report speech or thought, as in example 11 where she is providing an example of an accent she has heard. Here, DM like is used as an ‘exemplifier’ similar to other cases of DM like found in the data.

| 11. | but some like they say “toilet?” like <HARSH VOICE> “doilet”. (019F, 36:47) |

As DM like functions as an exemplifier (see Diskin 2017), it is arguably a less challenging strategy for L2 learners (similar to the zero quotative) to report examples of what they have heard, as compared to quotative be like. DM like has also been found to be relatively unproblematically acquired by Chinese L2 learners in Ireland (Diskin-Holdaway 2021). Regardless of the circumstances of its use, the fact that both lower proficiency speakers (e.g., 017F) and participants with shorter LoR (e.g., 016F) were using DM like more frequently, indicates that it may be easier to acquire than quotative be like.

4. Discussion

The results of this study, which uses a variationist approach to explore the quotative system for Chinese L2 learners of English in Australia by comparing their distribution of quotative variants with AusE and other L2 English speakers, indicate that there are differences in the L1 and L2 quotative systems. Quotative be like was far less represented in the L2 data as compared to the L1 group from Rodriguez Louro (2013). In the L1 data in Rodriguez Louro (2013), be like took up the largest proportion (65.4%; and 81.5% among 18–26 year-olds) of total quotatives, which is likely to have affected the use of other quotative variants such as say or think. With be like’s capacity to accommodate both direct speech and inner thoughts, it is likely that the large proportion of be like may have caused the rates to decrease for say and think, which are mostly used either to report direct speech (say) or inner thoughts (think), but not both. The proportion of use of be like in Travis and Kim (2021) was also high at 70%.

For the Chinese L2 corpus, the proportion of be like was far lower (7.4%) than Rodriguez Louro (2013) and Travis and Kim (2021) and limited in use to only a few participants. This is likely to have increased the proportion of other quotative variants and is evidenced in the data by a larger and more even distribution of the top two quotatives: say (34.3%) and zero (25.9%). As the data indicate that be like’s acquisition is still limited for the L2 group; and quotative say, which is mostly used to report direct speech, accounts for a larger proportion than be like, we expected zero to be used at relatively similar proportions to report both direct speech and inner thoughts. The distribution of constraints for content of the quote (Table 8), however, showed that both zero and say were mostly used to report direct speech, while be like was used in equal proportions for inner thoughts and direct speech. This means that the top two quotatives used by the Chinese L2 group were mostly for the reporting of direct speech.

One possible explanation for this phenomenon is the high proportion of ‘other’ quotatives used by the Chinese L2 group. Quotative think was used at a higher proportion compared to the L1 group, and quotative feel, which was not found in the L1 data, was also being used at a relatively high proportion (4.2%) to express inner thoughts. These results indicate that the L2 group was using a greater proportion, but also a wider variety of quotatives to report inner thoughts (and reported speech) compared to the L1 group. While the AusE L1 group’s ‘other’ category (including tell) only accounted for 1.9% of the data and consisted of just a handful of variants such as tell and ask (Rodriguez Louro 2013, p. 58), the L2 group’s ‘other’ category was in the top three in terms of proportion (10.6%), and included semantically richer quotatives, or “graphic introducers” (Labov 1972 cited in Tannen 1986, p. 322) including speak, ask, write, pronounce, wonder and believe. This proportion of ‘other’ quotatives among the L2 speakers increases to 18% when including quotative tell and feel (Table 5), so it constitutes a sizeable proportion of the L2 dataset. Despite the ‘other’ category taking up this notable proportion, there were not enough tokens for each quotative to provide a deeper analysis, as not many ‘other’ quotatives were repeated by the same participant more than twice. A deeper understanding of the participants’ L1 quotative system and the use of Chinese quotative markers such as gǎnjué ‘feel’ (see Yang 2021) may provide further insight into how the L1 may affect the L2 acquisition of quotatives. Furthermore, the fact that 11 out of the 14 participants had been mostly exposed to English within the formal education system may explain why more semantically rich quotatives were used by the Chinese L2 participants compared to the AusE data. However, this merits further research with a larger dataset.

Meanwhile, the results also indicate that social factors, such as a speaker’s length of residence (LoR) in the L2 environment or level of proficiency were important factors implicated in the acquisition of be like. This was evident by the fact that speakers with the highest proportions of be like (021M, 032M) were also among the participants who had the longest LoR and highest IELTS test scores. As these two speakers were found to have arrived in Australia at a younger age compared to other participants in the study, and had completed their undergraduate studies in Australia, the age at which they were exposed to native AusE surfaced as another potentially important language-external factor that may influence the acquisition of vernacular forms such as be like. This trend also raises the question of exposure. Postgraduate programs in Australia typically have high numbers of international enrolments, whereas undergraduate programs have far higher proportions of ‘locals’ (in this case, native AusE speakers), so these two participants may have had more exposure to locals by virtue of having completed undergraduate studies in Australia.

When comparing two participants by proficiency level and LoR (032M and 019F), it can be proposed that an L2 speaker’s competence in reporting speech or thought both indirectly and directly may influence their acquisition of innovative quotatives such as be like. For example, 019F confused the reporting of indirect and direct thought, as shown through her use of reported speech with the complementizer ‘that’. This showed that she did not have full mastery in reporting speech or thought in ways that would be expected for native speakers. Furthermore, as 019F did not produce any tokens of be like, despite producing a larger number of quotative tokens compared to others in the lower proficiency group, it may indicate, in line with Diskin and Levey (2019), that be like is a particularly complex quotative for L2 speakers to acquire, as it requires mastery of both tense and grammatical person. Our results do not align with those of Davydova (2021), however, who argued that quotative be like presents a “moderate” and “tolerable” cognitive load on the L2 learner (p. 190), particularly when compared to the acquisition of other sociolinguistic variables, such as the velar versus alveolar realization of the suffix -ing. We note additionally that 019F was found to be using DM like (a feature not explored in Davydova 2021), although she did not have full competence in reporting strategies for direct or indirect speech. This may indicate that DM like may have a lower ‘entry barrier’ for L2 learners (see Diskin-Holdaway 2021) and could precede the acquisition of quotative be like.

On language-internal constraints governing the use of be like among Chinese L2 speakers, there were near-equal distribution patterns for content of the quote and grammatical person. Rodriguez Louro (2013, p. 68) found a preference for encoding direct speech through be like among young adults, but for internal thoughts for pre-adolescents and adolescents, indicating that this constraint was already subject to change in the early 2000s. The Chinese L2 findings are corroborated by Travis and Kim (2021), who found that, apart from Chinese Australians’ “conservative” behavior with respect to be like, their Anglo and Italian background participants, born in the 1990s, displayed neutralization of language-internal constraints.

For grammatical person in the present study, the proportions of use of be like with first and third person were equal (both 31.3%) and slightly higher for existential ‘it’ (37.5%). Previous work (e.g., Tagliamonte and Hudson 1999; Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004; Rodriguez Louro 2013) has argued that other than the neutralization of constraints another indication of be like’s entrenchment into the grammar is the higher rate of use of existential ‘it’ with be like. Tagliamonte and Hudson (1999) wrote that it + be like constructions are “incipient grammatical form[s]” (p. 170) which were not likely possible until the advent of be like (Tagliamonte and D’Arcy 2004, p. 503). Rodriguez Louro (2013) reports that the use of existential ‘it’ (albeit low at 4.7%) among her youngest cohort is “structural evidence for the entrenchment of be like” (p. 71) into the Australian quotative system. As the Chinese L2 learners who used be like were already shown to have acquired existential ‘it’, it likely means that the native AusE they were exposed to made frequent use of it + be like constructions to report speech and thought.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses a gap in research into L2 English and AusE and presents preliminary results in exploring L2 acquisition of English quotatives. There were indications that certain ‘hurdles’ may exist for L2 learners to overcome, such as competence in reporting speech or thought both directly and indirectly, in order to acquire innovative quotative variants such as be like. In addition, as lower proficiency speakers with shorter LoR were using DM like to report speech or thought, it raises questions as to whether the use of DM like may precede the acquisition of vernacular quotative variants such as be like in situations where the length of time in a native speaking country has been minimal.

The Chinese L2 speakers displayed robust use of quotative say, which is likely the most frequent quotative heard in the L2 classroom, and quotative zero, which has been reported to be a universal strategy for reporting speech (Güldemann 2008) that is less challenging, morpho-syntactically speaking, than the use of other quotatives, such as be like (Diskin and Levey 2019). Despite the sociocognitive salience of quotative be like (Davydova 2021), this does not seem to have been sufficient for it to become a productive part of the Chinese L2 participants’ quotative system. Indeed, at only 16 tokens spread across four speakers, it emerged as a very marginal variant.

Overall, the question remains of what exactly has been acquired by these L2 speakers by virtue of both their (in many cases extensive) exposure to English in formal education settings and in less formal settings by living in Australia as international students. According to Labov (2007, p. 344), diffusion, which is the process underpinning most L2 contexts, results in a weakening of the original pattern and often reallocation of constraints on sociolinguistic variables (see Drummond 2011; Meyerhoff and Schleef 2014; Schleef 2017; Diskin and Levey 2019; Davydova 2021). What we have observed is indeed evidence for diffusion, where the Chinese L2 speakers have partially acquired the L1 system. They had lower rates of be like and higher rates of ‘other’ quotatives as compared to the L1 benchmark in Rodriguez Louro (2013). They displayed a neutralization of constraints on be like for content of the quote and grammatical person that has been found in many varieties of English, albeit not AusE as reported in Rodriguez Louro (2013) or Travis and Kim (2021). Quotatives say and zero constituted an important part of their quotative strategies and they mirrored constraints on these quotatives (say preferred in third person and for direct speech; zero preferred for direct speech) found for Irish English (Diskin and Levey 2019), American English (Blythe et al. 1990; Romaine and Lange 1991) and British English, but not Canadian English (Tagliamonte and Hudson 1999). These differences in use according to the variety of English or time of recording suggest that be like is a particularly challenging variant to acquire for L2 speakers since it is itself a ‘moving target’ in the L1 (Meyerhoff and Schleef 2014).

This study is not without its limitations. Quotative markers are reported to “occur most frequently in narrative discourse” (Davydova and Buchstaller 2015, p. 441). The sociolinguistic interviews were structured to put the participants at ease in a naturalistic environment, with hopes that the speakers would feel comfortable enough to tell personal stories. However, the interviews yielded few instances of narratives, which likely explains the lower number of quotative tokens overall as compared to the native speaker data in Rodriguez Louro (2013). Indeed, we acknowledge that this study is based on small token numbers (216 overall and just 16 tokens of be like) that are rather unevenly distributed across the speakers targeted for analysis. This may have also been due to the proficiency of the speakers and their comfort in engaging in conversations in the L2, especially as the interviews were being recorded in a studio, which could have made them feel more self-conscious. As a larger number of quotative tokens would provide in-depth results, especially for quantitative analyses, future studies would benefit from either having a larger pool of participants or finding different ways to elicit more narratives from the participants to have a larger number of quotative tokens in the data.

Also, as age of onset/exposure emerged as an important potential factor in the present study, having a broader range of language-external factors, including age, work experience in an L2 environment, motivation, and willingness to communicate (see Kim et al. 2022), etc., among speakers from a range of L1 backgrounds would provide more depth to understanding how L2 speakers acquire native patterns of language variation and change, but also potentially add more understanding to patterns in their native L1 quotative systems. Indeed, there has been little to no research investigating L1 influence on L2 acquisition of quotatives. Future comparison between learners’ native L1 versus their L2 quotative systems (see Yang 2021 on Chinese L1 use of gǎnjué ‘feel’ and juéde ‘think’ as discourse markers) could shed light on which factors may hinder or assist their acquisition of certain variants, including the effect of cross-linguistic influence.

Overall, a more comprehensive look into L2 quotative systems combining the variationist approach and SLA theories would provide further insight into the mechanisms involved in the acquisition process of quotatives for L2 learners, contributing to further understanding of the development of sociolinguistic competence among L2 speakers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K.C. and C.D.-H.; methodology, J.K.C. and C.D.-H.; software, J.K.C. and C.D.-H.; formal analysis, J.K.C.; investigation, J.K.C.; resources, C.D.-H.; data curation, C.D.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.C.; writing—review and editing, J.K.C. and C.D.-H.; visualization, J.K.C.; supervision, C.D.-H.; project administration, C.D.-H.; funding acquisition, C.D.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Faculty of Arts Research Grant, THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE (“A sociolinguistic investigation of the adoption of Australian English by migrants in a superdiverse urban area”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Faculty of Arts Human Ethics Advisory Group (HEAG) of THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE (protocol code 1648323; date of approval 2 December 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study may be available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to permission not having been obtained from the participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from Debbie Loakes, Rosey Billington and Hywel Stoakes for their assistance with data collection, and Hayden Blain and Xiaofang Yao for their insights into quotatives in Chinese.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Sample of questions and themes during sociolinguistic interview (see Diskin et al. 2019)

1. Work

What was your first ever job?

What was your worst ever job?

Your best ever job?

2. Living situation

Have you ever had to share a house or flat?

Who did you share with?

Have you ever had annoying neighbors?

What did they do?

3. Family

Where are your family originally from? Do they still live there now?

Do you have any siblings? Do you get along well with them?

Is there a parent you get on better with?

Grandparents that are still alive?

4. School

Did you go to one of the schools in your neighborhood? Was it far from your house?

Who was the worst teacher at school?

5. Travels

6. Socializing

Have you gotten to know many people since moving to Melbourne?

Do you get to spend much time with your friends?

What do you normally do at the weekend?

Have you ever had a really crazy night out in Melbourne? What happened?

7. Traditions

What kind of traditions can you remember growing up with in your family?

8. Identity

Do you feel a bit more Australian now that you have been living here?

Are there any Australian habits or customs that you picked up?

9. Language

What accent would you say you had and do you like it?

Do you think older and younger people talk the same in Melbourne (pronounce things the same and use the same words)?

Have you ever been in a situation where you’ve deliberately changed the way you talk? If so, why?

Do you think Australian people speak differently to the English you may have learned in school?

10. Demographics

11. Orientation to local area

What image or description of Melbourne would you give to someone who didn’t know it?

References

- Adamson, Hugh Douglas, and Vera Regan. 1991. The Acquisition of community speech norms by Asian immigrants learning English as a second language: A Preliminary study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 13: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, Federica. 2005. Quotative use in American English: A corpus-based, cross-register comparison. Journal of English Linguistics 33: 222–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, Federica, and Suzanne E. B. Eckhardt. 2007. Applying corpus-based findings to form-focused instruction: The case of reported speech. Language Teaching Research 11: 319–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Kara. 2013. The sociolinguistic interview. In Data Collection in Sociolinguistics: Methods and Applications. Edited by Christine Mallinson, Becky Childs and Gerald Van Herk. New York: Routledge, pp. 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Biber, Douglas, and Susan Conrad. 2009. Register, Genre, and Style. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blythe, Carl, Sigrid Recktenwald, and Jenny Wang. 1990. I’m like, ‘say what?!’: A new quotative in American oral narrative. American Speech 65: 215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle. 2004. The Sociolinguistic Constraints on the Quotative System: British English and US English Compared. Ph.D. thesis, University of Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle. 2006. Diagnostics of age-graded linguistic behaviour: The case of the quotative system. Journal of Sociolinguistics 10: 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle. 2008. The localization of global linguistic variants. English World-Wide 29: 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle. 2014. Quotatives: New Trends and Sociolinguistic Implications. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle, and Alexandra D’Arcy. 2009. Localized globalization: A multi-local, multivariate investigation of quotative be like. Journal of Sociolinguistics 13: 291–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchstaller, Isabelle, and Ingrid Van Alphen, eds. 2012. Quotatives: Cross-Linguistic and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Butters, Ronald R. 1982. Editor’s note [on ‘be+ like’]. American Speech 57: 149. [Google Scholar]