2.1. Comparison of Spanish and Korean Subject Expression

Both Spanish and Korean are pronoun-dropping, or pro-drop, languages. However, each language differs notably with respect to how subjects are expressed or used.

Spanish subjects may be expressed overtly as personal pronouns, lexical noun phrases, and other types of less frequently occurring pronouns. The Spanish language also permits null subjects whereby the referent of a tensed verb is not explicitly expressed. The different subject forms permitted in Spanish are illustrated in (1).

- (1)

Es profesora (null subject)

“[He/she] is a professor”

Los estudiantes son listos (lexical noun phrase)

“The students are bright”

Ellos también son trabajadores (personal pronoun)

“They are also hard working”

Esto es diferente (demonstrative pronoun)

“This is different”

¿Quién es? (interrogative pronoun)

“Who is it?”

Alguien no era muy responsable (indefinite pronoun)

“Someone wasn’t very responsible”

In most finite contexts (i.e., subject + tensed verb), Spanish subjects are variably realized with either an overt form or as a null subject, as shown in (2). Subject dropping in Spanish varies across dialects, ranging from as little as 20% (Madrid:

Cameron 1992) to as much as 50% or higher (Santo Domingo:

Martínez-Sanz 2011). This syntactic context is of interest in the present study and has been the focus of extensive theoretical and empirical attention in the sociolinguistics and second language acquisition literature.

- (2)

Yo quiero eso

“I want that”

Ø Quiero eso

“[I] want that”

Research in the field of sociolinguistics in particular has been instrumental in identifying the factors that constrain or influence this variation between overt and null subject forms in native-speaker Spanish, and most previous studies have limited their analysis to null subjects and overt subject pronouns (although see, e.g.,

Dumont 2006;

Gudmestad et al. 2013;

Gudmestad and Geeslin 2021, who include lexical noun phrases in their analyses of third-person subject expression). The linguistic factors selected for examination pertain to aspects of the linguistic system as well as the discourse-pragmatic context in which speakers communicate.

Table 1 offers a summary of key linguistic factors that have been examined in previous research on variable subject expression in Spanish, as well as findings from studies that have investigated those factors

1. These factors have been key to explaining patterns of subject expression across varieties of native-speaker Spanish (

Carvalho et al. 2015), as well as non-native or L2 Spanish (e.g.,

Geeslin et al. 2015;

Geeslin and Gudmestad 2008b). With respect to the factors of verb person and verb number, it is important to highlight that some studies have analyzed verb persons separately (e.g., first-person vs. third-person subjects), given the differing range of variants observed across distinct verb person and number contexts, and because research has found it to be one of the most important predictive factors (e.g.,

de Prada Pérez 2015;

Geeslin and Gudmestad 2016;

Gudmestad and Edmonds n.d.;

Posio 2011;

Torres Cacoullos and Travis 2010). Given these differences, the present study focused exclusively on first-person subjects.

Although both Spanish and Korean are pro-drop languages, Korean differs from Spanish in that its word order is subject-object-verb (as opposed to subject-verb-object for Spanish), and objects along with subjects may be dropped when pragmatically appropriate (

Sohn 1999). With respect to subject expression, Korean permits a variety of forms in subject position, including null subjects (which Spanish also permits), as illustrated in (3).

| (3) | danyeo | wasseo (null subject) | | |

| | go | come.PST | | |

| | “I’m back” | | | |

| | | | | |

| | gae-ga | neomu | gwiyeob-da (lexical noun phrase) | |

| | dog-NOM | very | cute-DECL | |

| | “The dog is so cute” | | | |

| | | | | |

| | geunyeo-neun | ttogttogha-da (personal pronoun) | | |

| | she-TOP | smart.do-DECL | | |

| | “She is smart” | | | |

| | | | | |

| | igeos-eun | swiwo-yo (demonstrative pronoun) | | |

| | this-TOP | easy-POL | | |

| | “This is easy” | | | |

| | | | | |

| | nu-ga | mandeul-eosseo? (interrogative pronoun) | | |

| | who-NOM | make-PST | | |

| | “Who made it?” | | | |

| | | | | |

| | eotteon | salam | chaeg-eul | ilheo beol-yeoss-da (indefinite pronoun) |

| | Some | person | book-ACC | lose-PST-DECL |

| | “Someone lost the book” | | |

Subject dropping is fairly common in spoken and written Korean (nearly 70% in spoken language and about 50% in written language;

Kim 2000; see also

Lee 2019). According to

Sohn (

1999), this is particularly the case when the subject refers to the speaker in declarative sentences (e.g.,

danyeo wasseo “[I] am back”) and the hearer in interrogative sentences (e.g.,

da haesseo? “Are [you] all done?”). In some contexts, such as greeting, thanking, apologizing, and congratulating, subjects do not appear and may be considered ungrammatical or unacceptable if used explicitly (

Sohn 1999).

Korean also differs from Spanish in that it has a system of hierarchical personal pronouns for first- and second-person subject referents (see

Table 2). With respect to first-person subject pronouns, the plain or informal forms are generally used when speaking with children or younger adults, whereas the humble or polite forms are used when speaking with someone senior or a social equal. Second-person subject pronouns are not used to refer to addressees who occupy a higher social position than the speaker; speakers instead use nominals such as professional titles to refer to socially superior individuals (e.g.,

seonsaeng-nim “esteemed teacher,”

sajang-nim “esteemed company president;

Sohn 1999, p. 409). Speakers may also use a kinship term (e.g.,

oppa “brother [female speaker],”

halmeoni “grandmother”) or a name to refer to their addressees. That stated, speakers’ selection and use of a reference form (particularly for second-person referents) are not fixed (

Na 1988) and depend on a complex and dynamic interplay of social factors such as age, closeness, and discourse formality (

Lee 2019).

Third-person personal pronouns such as he, she, and they that are common in Indo European languages do not have an exact equivalent in Korean. Instead, the demonstrative geu is used or combined with other morphemes to refer to individuals in the third person: geu “he, it,” geu-nyeo “she,” geu-deul “they.” Demonstrative pronouns are used to refer to objects in contexts of third-person reference (igeot “this,” geugeot “that,” jeogeot “that over there”).

Subject dropping in Korean has garnered extensive attention in previous research (e.g.,

Ahn and Kwon 2012;

Huang 1984,

1989;

Im 1985;

Lee 1993;

Moon 2010), perhaps due to the prevalence of this phenomenon in spoken discourse (

Lee 2019). Fewer studies focus on overtly expressed subjects and do so from a pragmatic perspective as opposed to a formal syntactic perspective. To date the most comprehensive analysis of overt subject expression in Korean from a pragmatic point of view has been carried out by

Lee (

2019), who focused on first- and second-person subjects in spoken Korean. Her quantitative analysis showed that overt expression was infrequent (31% for first-person referents and 22% for second-person referents) and patterned distinctly by age and gender differences. Specifically, male speakers employed more first-person subjects with other male speakers than female speakers; male speakers also used more first-person subjects with younger speakers than older or same-aged speakers. Female speakers, on the other hand, employed first-person subjects at similar rates regardless of any age or gender differences. For second-person subjects, overt expression was more frequent with peers than younger or older speakers for both male and female speakers. N. Lee’s discourse analysis revealed that overt expression occurred when speakers created explicit or implicit contrast between referents (e.g., “

I am going to the office today, but

Mr. Murata is not” [explicit contrast; p. 112]; “Do [you] remember?

You ran away in front of the gate to the court” [implicit contrast). To the best of the author’s knowledge, a quantitative, variationist account of subject expression in Korean does not exist.

In sum, although both Spanish and Korean permit null subjects, each language differs with respect to the factors or constraints guiding subject omission. Furthermore, the range of subject forms used by speakers to address themselves, their listener(s), and others is distinct and does not share the same contexts of use across these languages, which is likely due to the hierarchical system of personal pronouns for first- and second-person referents and the lack of true personal pronouns for third-person referents in Korean. Based on these observations and keeping in mind that the current study focuses on first-person referents, the primary acquisitional challenge facing Korean-speaking learners in the development and use of variable first-person subject expression in Spanish includes adjusting rates of null subject use to reflect sensitivity to linguistic factors known to influence variable subject omission in native-speaker Spanish.

2.2. L2 Acquisition of Spanish Subject Expression

The development and use of Spanish subjects have garnered extensive attention in the L2 acquisition literature. Previous research on subject expression in L2 Spanish has been examined from a variety of theoretical perspectives, including generative (e.g.,

Al-Kasey and Pérez-Leroux 1998;

Isabelli 2004;

Liceras and Díaz 1998,

1999;

Lozano 2002a,

2002b;

Pérez-Leroux and Glass 1997,

1999;

Rothman and Iverson 2007a,

2007b,

2007c), discourse-pragmatic (e.g.,

Blackwell and Quesada 2012;

Quesada and Blackwell 2009), and variationist (e.g.,

Geeslin and Gudmestad 2008b,

2011,

2016;

Gudmestad and Geeslin 2010;

Gudmestad et al. 2013;

Linford 2009,

2012). The review presented in this section will focus on previous research carried out from a variationist perspective, as the present study adopted this framework for examining variable subject expression in L2 Spanish.

Variationist research on subject expression in L2 Spanish has aimed to document patterns of subject expression in learner Spanish, focusing on native English-speaking learners (e.g.,

Geeslin and Gudmestad 2008b,

2011,

2016;

Gudmestad and Geeslin 2010). This body of research adopted methodologies from quantitative sociolinguistics (

Labov 1972;

Tagliamonte 2012) and incorporated a native-speaker comparison group in their analyses to determine whether learners’ patterns of use demonstrate sensitivity to the same linguistic and extralinguistic factors or constraints observed for native speakers. For example,

Geeslin and Gudmestad (

2008b) demonstrated that advanced learners produced the same range of subject forms as native speakers during a sociolinguistic interview. Subtle differences in frequencies for some subject types were uncovered, particularly when examined against verb person, number and specificity of the referent. Specifically, the advanced learners used more null subjects than native speakers with first-person plural, second-person singular, and third-person singular referents. Additionally, the distribution of subject forms with group and non-specific referents differed between learner and native-speaker groups.

In a follow-up study,

Gudmestad and Geeslin (

2010) extended their analysis of advanced learners’ use of Spanish subjects to include verb TMA, another linguistic factor examined extensively in variationist research on subject expression in native-speaker Spanish, as well as verb form ambiguity and switch reference. They found that the distribution of subject forms produced by learners and native speakers differed significantly across categories of the verb TMA factor, and the effect of this factor was mediated by discourse redundancy. Specifically, verb TMA effects persisted in switch but not same-reference contexts. Geeslin and Gudmestad further explored the role of discourse on advanced learner subject expression in their 2011 study that focused on two discourse-level factors: referent cohesiveness and perseveration (i.e., priming). Referent cohesiveness refers to “the distance and function of the previous mention of the referent” (

Geeslin and Gudmestad 2011, p. 21). They found that subject expression was influenced by distance from the original mention of the referent, in that fewer null subjects were produced as distance increased. With respect to the perseveration variable, both learners and native speakers demonstrated the pattern for more null subjects following null subjects and more overt subjects following overt subjects.

In his cross-sectional study on native English-speaking learners of Spanish,

Linford (

2009) examined the relationship between L2 learners’ subject expression and several linguistic factors including verb person and number, referent specificity, continuity of reference (i.e., switch reference), verb semantics, clause type, as well as extralinguistic factors such as age, gender, and time spent abroad. With respect to rates of subject use, Linford found that beginning learners produced primarily null subjects (60.1%) and the rate of null subject use increased as proficiency increased (reaching 87.4% for advanced learners). Linford noted that these rates overshot native-speaker rates (

Otheguy et al. 2007), an observation that is echoed in variationist L2 research on subject expression (see also

Geeslin et al. 2015). With regard to the linguistic factors examined, learners’ use of subject forms showed more similarities with than differences from native speakers. For instance, a higher rate of overt subjects was observed with singular as opposed to plural referents and in contexts of switch reference as opposed to same-reference contexts. Linford’s analysis also uncovered an effect for speaker gender whereby female learners, similarly to female native speakers, produced overt subject pronouns at a higher rate than male learners.

To summarize, previous research on L2 Spanish subject expression carried out within the variationist tradition has established several key findings. Firstly, learners produce the same range of subject forms as native speakers, and rates of subject form use show subtle differences from native speakers. Developmental research shows that English-speaking learners’ use of null subjects increases as proficiency in the language increases, eventually overshooting native-speaker rates (

Linford 2009). Secondly, learners demonstrate nativelike sensitivity to several of the linguistic factors that explain native-speaker use in the sociolinguistics literature, but again subtle differences between learners and native speakers are reported. The preceding review illustrates an exclusive focus on English-speaking learners, whose first language does not permit subject omission with tensed verbs, as well as a general lack of examination of individual characteristics such as speaker sex and experience with the Spanish language (for an exception, see

Gudmestad and Edmonds n.d.)

2. Research on Korean learners of Spanish, whose first language permits subject omission, has begun to receive attention (e.g.,

Long 2016; see also

Long and Geeslin 2018), and the present study builds on it by exploring the role of individual learner characteristics in the acquisition of variable subject expression in L2 Spanish.

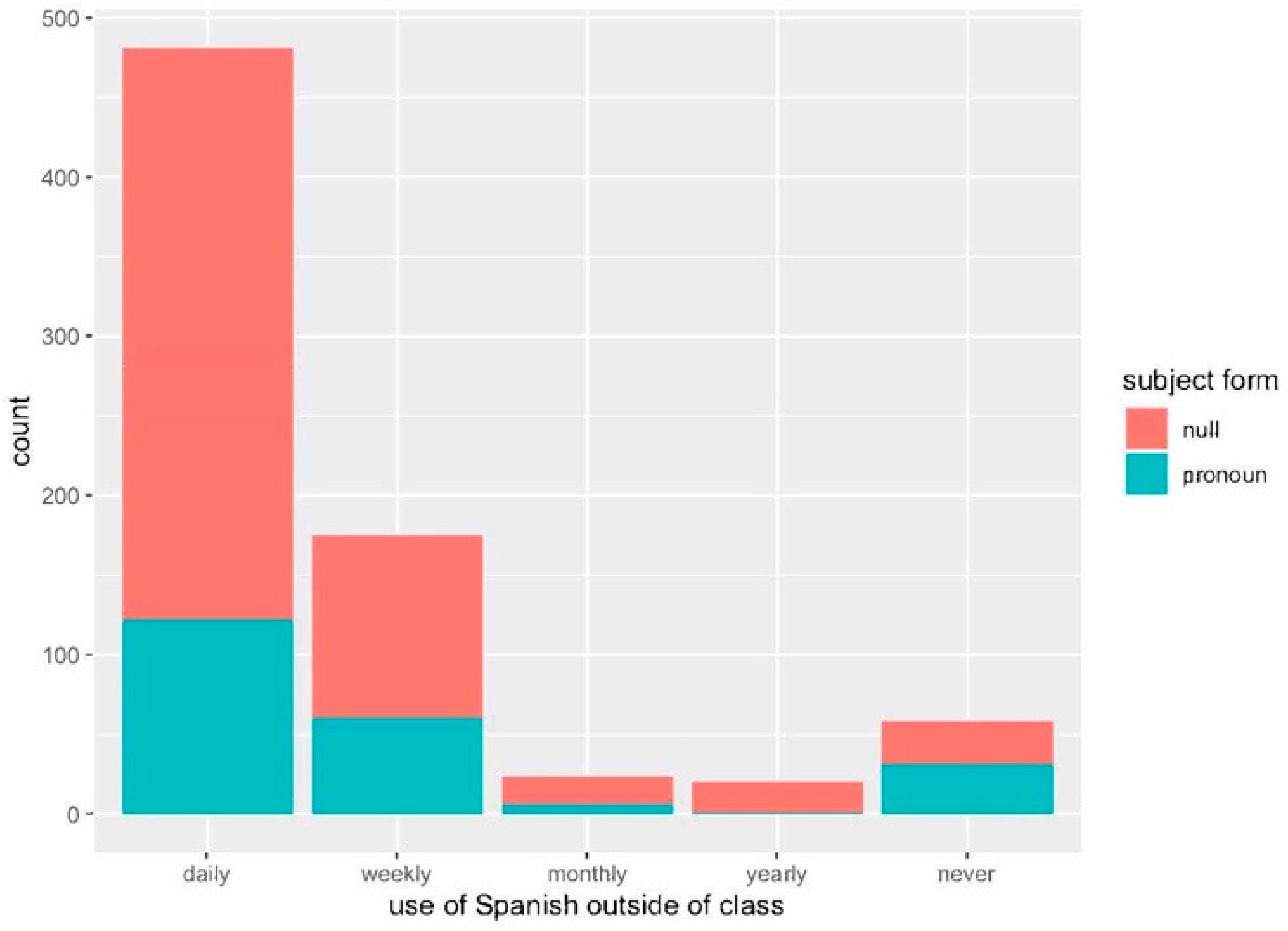

What forms do Korean-speaking learners produce in the subject position of tensed verbs for first-person referents in Spanish?

With what frequency are first-person subject forms produced, and how does this frequency change across four different levels of instruction?

What linguistic and extralinguistic factors predict first-person subject form use for Korean-speaking learners of Spanish?