1. Introduction

When discussing the crosslinguistic variability in sentence stress patterns,

Ladd (

2008, pp. 251–53) asks himself whether languages can differ “without limit and in unpredictable ways” or if the variation is constrained in some principled way. Much of the research that has explored the prosodic marking of information structure has accounted for this variability by looking at the syntactic properties of a given language (

Kügler and Calhoun 2020). We want to contribute to this discussion by focusing on morphology, which has been acknowledged to play a role (e.g.,

Büring 2010, p. 177) but has been comparatively less studied (e.g.,

Kügler and Calhoun 2020). We begin our exploration with the analysis of two indigenous languages of the Americas, Quechua and Inuktitut, which have been described as having a very limited use of intonation (

Johns 2010;

Shokeir 2009, for Inuktitut;

Sánchez 2010, for Quechua). This limited use of intonation appears to characterize also the second languages (Spanish and English, respectively) spoken by L1 Quechua and Inuktitut speakers, and may be a general characteristic of the L2 spoken by speakers of indigenous languages, at least in North America (

Newmark et al. 2016).

Without excluding other possible explanations

1, we hypothesize that these languages are at an extreme of a continuum of possible interactions across language modules. In these languages information structure is mapped onto a rich morphological layer with very limited or no prosodic marking of information structure and/or sentence type. At the other extreme of the continuum, we find languages such as English and Spanish, which lack a rich set of grammaticalized morphemes that convey discourse-level information but use intonation to a relatively large extent (

Ladd 2008;

Vallduví 1990). However, even within this latter group of languages, the division of labor between syntax and prosody varies, with English relying more on prosody and Spanish more on syntax to mark information structure.

We propose here that this crosslinguistic difference follows from a division of labor across language modules very much inspired in previous analyses of focus (e.g.,

Féry 2013;

Xu 2004), such that two extreme values of the continuum of possible interactions across them are available. At one of the extremes of the continuum, a rich set of morphological markers with scope over constituents convey sentence-level distinctions, as in (1), and discourse-level values such as focus and evidentiality (attested or reported information), as in (2). In languages such as Inuktitut and Quechua, the alignment of intonational patterns and information structure is apparently redundant. This, of course, does not preclude the existence of languages at the center of the continuum that allow for morphology and intonation to interact with syntax and information structure.

Quechua

| 2. | a. | Mariya-m | papa-ta | mikhu-rqa-n2 |

| | | Mariya-EVID.ATT.FOC | potato-ACC | eat-PST.ATT.3.S |

| | | “Mariya ate potatoes” (attested information) |

| | b. | Mariya-s | papa-ta | mikhu-sqa-n |

| | | Mariya-EVID.REP.FOC | potato-ACC | eat-PST.REP-3.S |

| | | “Mariya ate potatoes” (reported information) |

At the other extreme, a series of consistent alignments of PF and syntactic structure are required to establish major distinctions between different types of sentences, such as declaratives or yes/no questions, as in (3), as well as to determine the relevant information value of a constituent (e.g., topic or focus), as in (4) (

Ladd 2008).

| 3. | a. Poppy wrote the paper. |

| | b. Did Poppy write the paper? |

| 4. | I think Stella wrote the paper. |

| | No, POPPY wrote the paper.3 |

Given the crosslinguistic differences sketched above, our goal is to explore two research questions. First, is there a complementary distribution in the use of morphology and prosody to mark information structure and sentence type in Quechua and Inuktitut? Second, what patterns can we predict for bilingual speakers in each contact situation? In the rest of the paper, we will argue that the possible division of labor across modules may result in configurations in which syntax interacts with morphology or with intonation, resulting in the latter two being in a continuum of different levels of interface with syntax, so that in some languages intonation has a greater role, whereas in others, like Inuktitut and Quechua, morphology does (see

Section 4). To support our proposal, we will summarize the main findings of the literature on the mapping of information structure onto the morphology, syntax, or intonation (

Section 2) and present evidence regarding the marking of sentence type and focus or topic in Quechua and Inuktitut (

Section 3). In the final section, we will show that our proposal has consequences for the development of bilingual grammars, since in language contact situations, overlap between the two patterns of module interaction can occur, as allowed by our view that modular interaction takes place along a continuum. We will provide evidence from Quechua–Spanish and Inuktitut–English bilinguals that supports the view that there is bidirectionality of crosslinguistic influence such that intonational patterns emerge in non-intonational languages to distinguish sentence types. Conversely, morphemes or discourse particles emerge in intonational languages to mark discourse-level features such as focus and evidentiality.

2. Background: Morphology, Syntax, Information Structure, and Intonation

The current proposal stems from a generalization over a series of empirical observations and theoretical proposals regarding the mapping between information structure and different components of the grammar. First, several morphologically rich (polysynthetic and/or agglutinative) languages have been described as having very little intonational variation along the utterance, with tonal movements mostly restricted to utterances’ edges. Indeed, in such languages, intonation seems to be used mostly for demarcative purposes. This is not only the case of the languages under analysis here (see

Section 3), but it has also been reported for some Australian languages (

Fletcher and Evans 2002;

Ross et al. 2016). Moreover, if we look at the prosodic typology proposed by

Jun (

2014), all the languages classified as “edge-prominence languages”, listed in

Table 1 below, are agglutinative. Edge-prominence languages do not have any lexically or post-lexically specified head and mark prominence at the edge of the word or phrase. From a morphological point of view, all these languages have affixes to mark sentence types and/or information structure (e.g.,

Arnhold 2014;

Fortescue 2017a for Eskimo-Aleut languages;

Igarashi 2014;

Kubozono 2007 for Japanese;

Jeon and Nolan 2017;

Song 2005 for Korean;

Karlsson 2014, for Mongolian).

This empirical observation, which highlights a possible link between morphological and prosodic typology, prompted us to explore a long-standing theoretical debate, namely the division of labor and/or the mapping between phonology (prosody in our case) and other components of the grammar. The claim that there is a division of labor between prosody and other components of the grammar is not new. Researchers have noted, for example, that languages may use morphemes to “convey the kinds of meaning that in other languages can often be signaled intonationally” (

Ladd 2008, p. 5). Among those morphemes, Ladd briefly mentions question and focus particles. Discussions on the complementarity of particles and intonation are particularly prominent in Cantonese linguistics (see

Wakefield 2012 for a summary), and experimental studies, such as

Wakefield (

2012), revealed that the Cantonese particle

lo1, which is used to express “obviousness”, is systematically translated into English by using a high-low contour. We interpret this as further evidence of the possible complementarity between morphology and prosody in some languages at the two extremes of a continuum of modular interaction.

Since the division of labor between morphology and prosody has attracted less attention than the relation between prosody and syntax (

Kügler and Calhoun 2020), we will build our current proposal taking as a point of departure the existing literature on the relations between prosody and syntax. Thus, we turn to Vallduví’s (

Vallduví 1990; see also

Ladd 2008) idea of plasticity, which states that if a language has flexible word order, then it is less likely that prosody will be used to mark focus. When comparing focus marking in Romance (Catalan and Spanish, in particular) with Germanic languages (English), Vallduví observes that since intonational prominence is clause final in Catalan (5), focus fronting (6) is a way to give prominence to non-final constituents. Thus, if the word

ganivet ‘knife’ needs to be focalized, it can be moved to clause-initial position. English, instead, can mark focus in situ by associating a pitch accent with the focalized word.

| 5. | Hi | fiquem | el | Ganivet | al | calaix. |

| | There | put | the | Knife | in the | drawer |

| | “I put the knife in the drawer.” |

| 6. | El | GANIVET | vaig | Ficar | al calaix de dalt |

| | The | knife | I | Put | in the top drawer |

| | “I put the knife in the drawer.” |

Since Vallduví’s original proposal, many experimental studies have challenged this binary classification.

Face and D’Imperio (

2005) have proposed to treat “plasticity” as a continuum, since there is evidence that languages within the same family (in their case, Madrid Spanish and Neapolitan Italian) differ in their use of syntactic and prosodic cues to mark focus, with Spanish being closer than Italian to the word order extreme of the continuum, since Spanish uses word order or intonation to mark focus whereas Italian uses both. More recent studies have further nuanced a rigid typological division, showing that even in Catalan multiple strategies may be used to mark focus (

Feldhausen and Villalba 2020) and that varieties of the same languages differ in the extent to which they use word order or prosody to mark focus (

Feldhausen and Vanrell 2014,

2015;

Gabriel et al. 2009;

Gabriel 2010).

The proposal that languages may either resort to syntax or to prosody to mark focus continues to be present in more recent theoretical models. In particular, the analysis of focus as prosodic alignment (

Féry 2013) distinguishes the linearization of the focalized constituent (at the left or right of a prosodic domain) from the linguistic mechanisms used to signal such alignment, which may range from morpheme insertion to the use of pitch accents or deaccenting. Thus, if prosodic alignment is fulfilled by non-prosodic mechanisms in a given language, there is no need to mark focus prosodically. Crucially, this does not imply that focus cannot be marked redundantly by both prosody and morphology.

In summary, this literature reveals that languages are situated along a continuum regarding whether they resort to either syntax or prosody to mark information structure. There are clear cases at the extreme of such continuum (e.g., English resorting to intonation to mark focus) and languages that may use both (e.g., Catalan). Thus, we propose here to extend this idea regarding the weak complementarity between prosody and other components of the grammar to morphology. We suggest, then, that languages that have a rich morphology with particles or affixes that are used to mark questions, information structure or evidentiality tend to have a very limited use of intonation to mark, for example, sentence type or focus. This does not mean, though, that prosodic marking of such linguistic structures cannot be present in these languages or be introduced through language contact, as we will show later in this paper. In the next section, we will explain why this redundancy is apparently avoided in some languages by turning to Gussenhoven’s analysis of tonal events as morphemes, which will allow us to articulate why in those languages either morphology or prosody interact with syntax in the marking of information structure. The languages that we are using to illustrate our point, i.e., Inuktitut and Quechua, have both a rich morphology and a limited use of intonation, as we will see in our next section.

4. Our Proposal

We propose, then, that the crosslinguistic differences discussed above follow from differences in the division of labor across language modules at the interface between syntax, information structure, and PF or morphology along a continuum of possible modular interactions. One possible arrangement is that at the interface between syntax and information structure a series of consistent alignments of PF and syntactic structure are required to establish major distinctions between different types of sentences (declarative, interrogative, exclamative sentences) as well as to determine the relevant information value of a constituent (for instance, topic and focus values). At the sentential level, these alignments do not exclude, in principle, the possibility of multiple syntactic operations such as merge to interface with the information structure component. For instance, interrogative sentences in English may have, in addition to specific intonational patterns, do-support and wh-movement. Another possibility is that a rich set of morphological markers with scope over constituents convey sentence-level distinction and focus with a highly restricted alignment of intonational patterns and information structure, as languages such as Inuktitut and Quechua illustrate. In this proposal, we aim to account for why it is the case that some languages fall within one extreme of the continuum of possibilities for interaction across modules.

Inuktitut and Quechua raise the question of why there is such a division of labor between phonology and morphology at the intersection with information structure in them. A potential explanation can be articulated if we adapt Gussenhoven’s proposal (

Gussenhoven 2004, p. 22) that intonational contours have a morphological structure, which defines the meaning of the contour, and a phonological structure, which specifies its tones. If, in a given language, the meaning of the contour is encoded in the morphology (thus, segmentally marked), as is the case in Quechua or Inuktitut, then, such language would be less likely to encode information structure in the phonology or would encode it minimally. Conversely, a language that does not encode information structure in the morphology (e.g., focus in Germanic languages) would be more likely to encode it in the phonology. We would like to make it explicit that our proposal does not preclude the possibility of redundancy such that both intonation and morphology can be recruited to encode the same value of information structure. Rather, we propose that modularity and interaction across modules offers, in addition to redundancy, a choice between phonology and morphology. Languages such as Inuktitut and Quechua represent the morphology option.

11A complementary explanation, couched in the focus as prosodic alignment proposal (

Féry 2013) would be that since the information structure is already marked in the morphology, it would be less likely for it to be marked prosodically. We further argue that this is because morphemes (at least in these languages) are transparent, unambiguous markers of the structures under study. Intonation, instead, always has multiple layers of meaning, ranging from linguistic to paralinguistic meanings (e.g.,

Ladd 2008); or in Bolinger’s words (

Bolinger 1986, p. 13): “since no human utterance can be totally without emotion, one can never be certain where the ‘grammar’ of an utterance ends and its ‘emotion’ begins.” In both Quechua and Inuktitut prosodic variation is kept to a minimum and it is mainly deployed for demarcative purposes (for this reason, it can be classified as an edge-prominence language; Jun 2014), to signal the end of a prosodic domain (word or utterance). The prosodic marking of the edge rather than of the head, as is the case in English, may be related to the fact that the word is the domain of syntactic recursion. If, as

Fortescue (

2017a) puts it, words in Inuktitut are holophrastic (i.e., there is no clear distinction between morphology and syntax), the marking of the head/root (as opposed to the prosodic word) may make it difficult to interpret the meaning of the word, since suffixes are cumulative as concerns semantic scope.

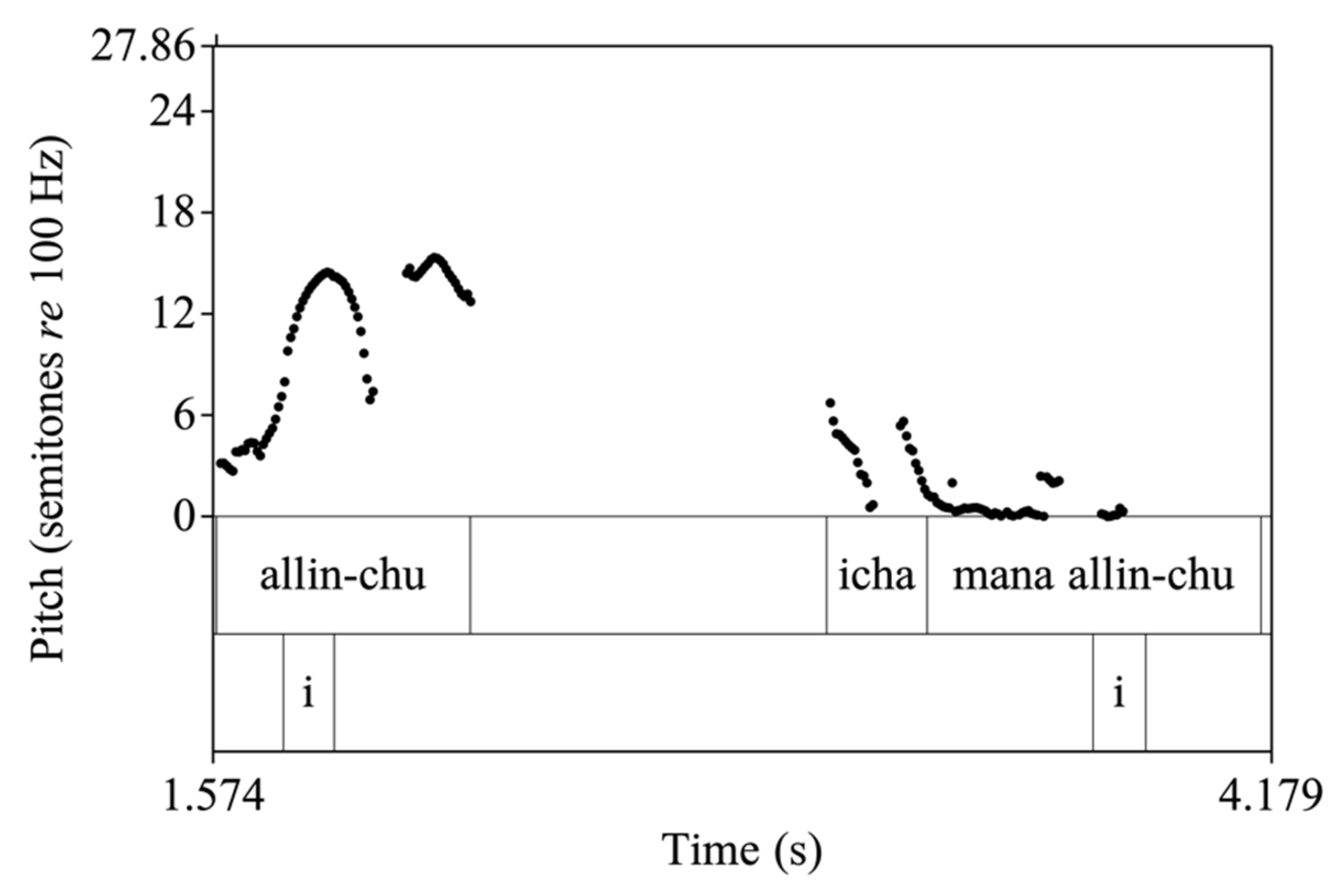

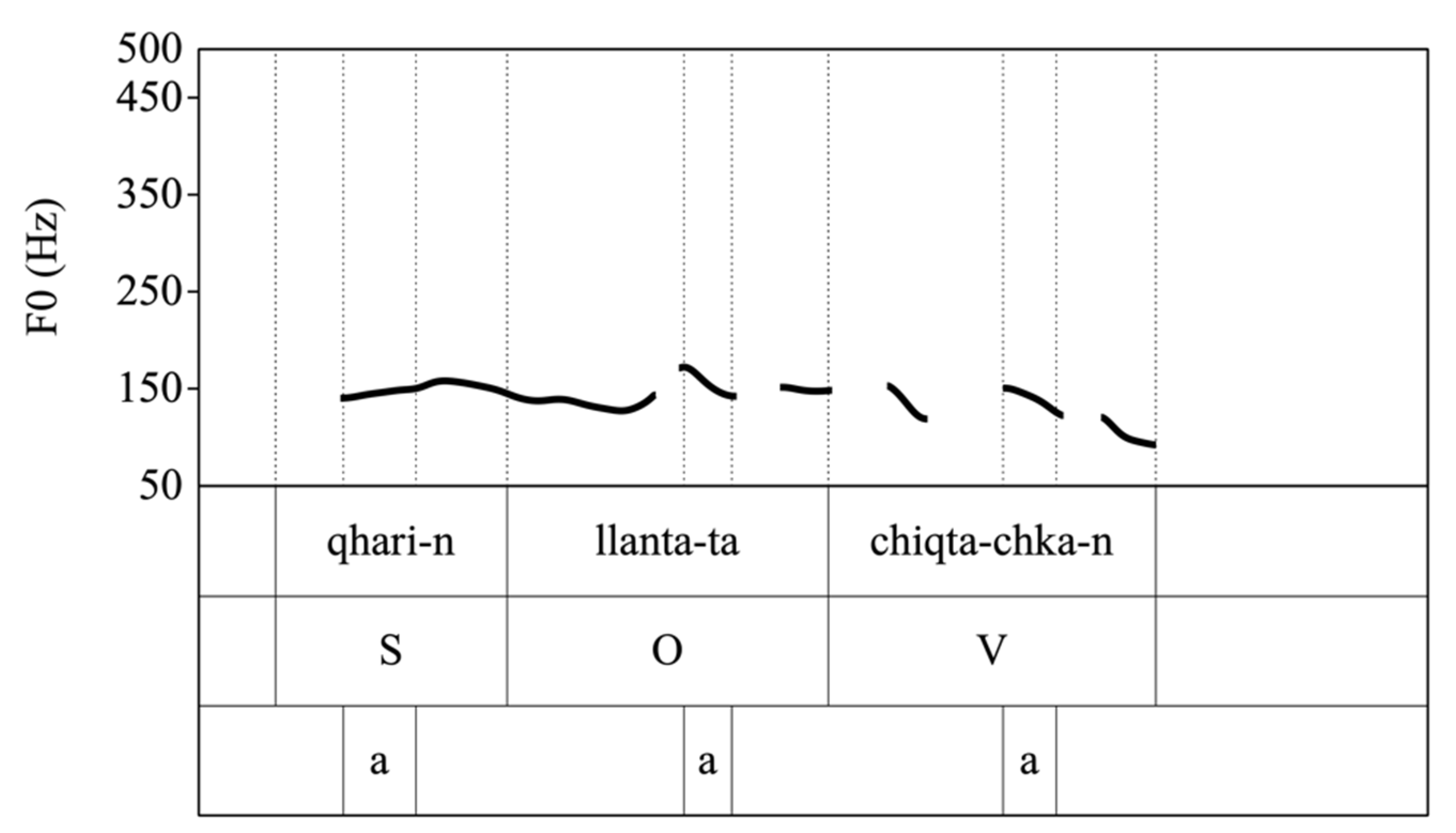

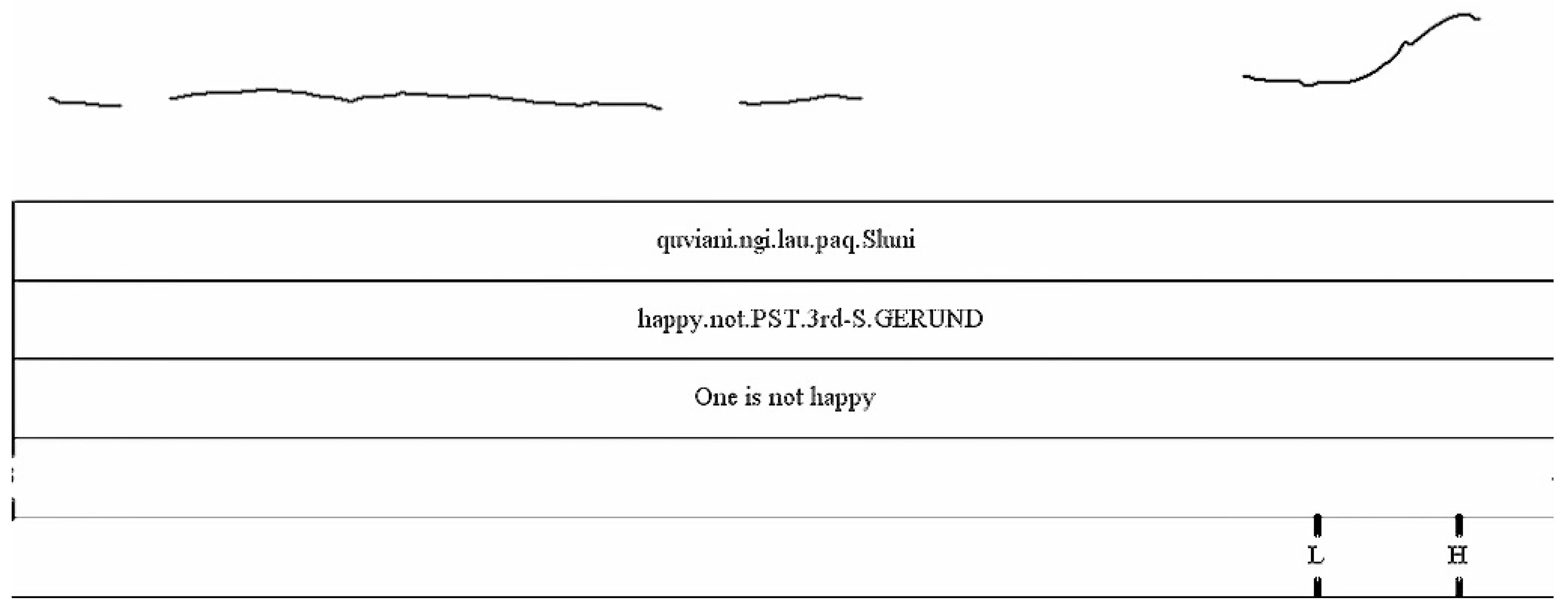

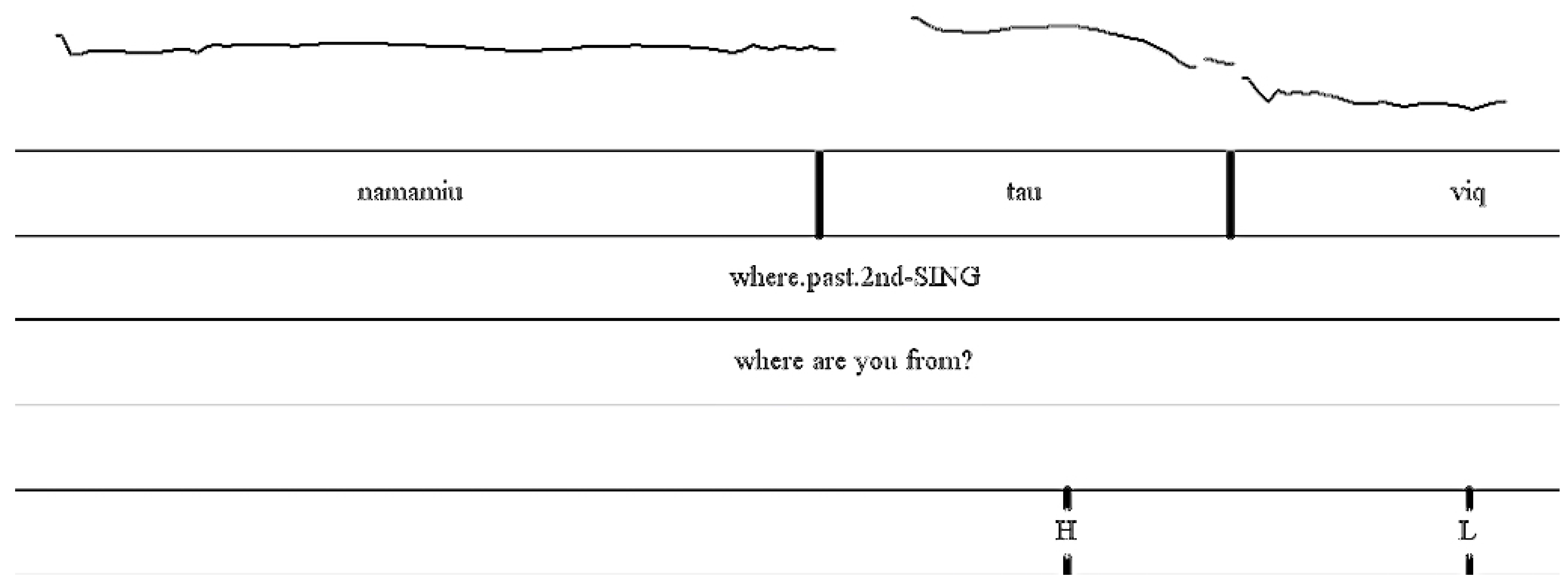

12 The fact that the domain of recursion is the prosodic word may have an additional consequence for the prosodic structure of the utterance, namely the absence of prosodic recursion. As explained in

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2, the absence of declination seems to characterize the prosody of both Quechua and Inuktitut. Indeed, peak height was relatively constant across the utterance. Although these are preliminary results based on relatively short sentences (particularly our Quechua data), we interpret this absence of declination as indicative of an absence of prosodic embedding (see

Féry 2017, pp. 78–85, for a discussion).

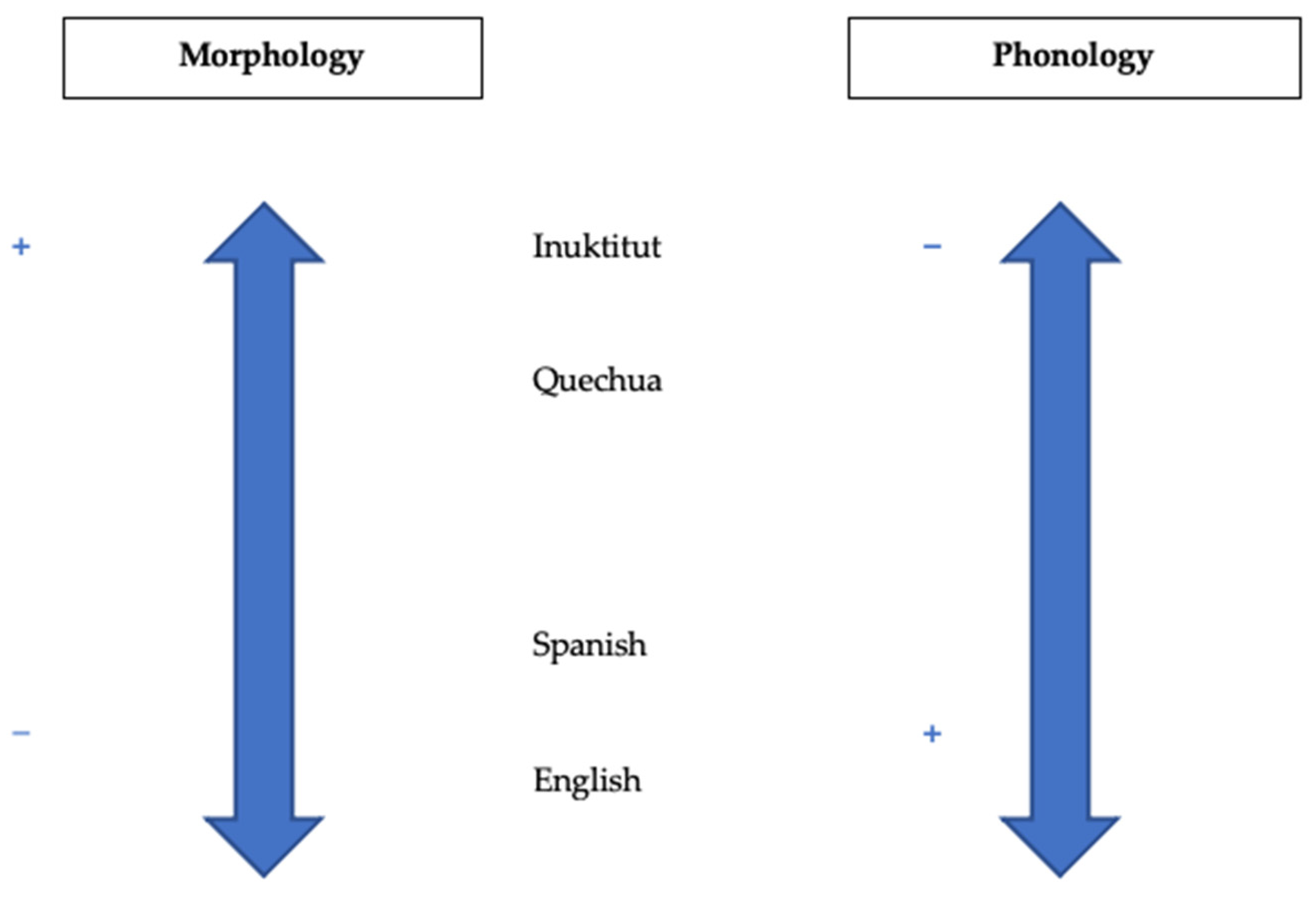

Figure 8 schematizes the inverse relationship between morphology and prosody in the languages under study:

Both options (relying on syntax and intonational patterns or on morphemes) are compatible with assigning information value to the dislocated material at the left and right peripheries as well as contrastive focus. There is, however, a significant distinction between both options: while intonational patterns do not necessarily show scope effects on the surface, morphological patterns do. In a sentence such as (21) below, contrastive focus on the constituent as well as the yes/no nature of the question are marked by the suffix -

chu, and no final rising intonation is required (the sentence meaning is closer to English “Was the load what the men tied?”):

| 21. | Runa-kuna | qipi-ta-chu | wata-sa-nku? |

| | man-PL | load-ACC-INTR/FOC | tie-PROG-3.PL |

| | “Do the men tie the load?” (Muntendam 2015) |

If a negative yes/no question is asked, then

-chu must appear on negation as in (21):

| 22. | Mana-chu | runa-kuna | qipi-ta | wata-sa-nku? |

| | NEG-FOC/INT | man-PL | load-ACC | tie-PROG-3.PL |

| | “Don’t the men tie the load?” |

In contrast with the declarative negative in (22):

| 23. | Mana | runa-kuna | qipi-ta-chu | wata-sa-nku |

| | NEG-FOC/INT | man-PL | load-ACC | tie-PROG-3.PL |

| | “The men don’t tie the load” |

5. Implications

The languages that we described in

Section 3 have been in contact for centuries with Romance and Germanic languages. According to the 2007 Census conducted by the Peruvian National Institute of Statistics (

INEI 2007), 51.4% of respondents in the Cusco region aged 3 and older declared Quechua to be their mother tongue, but in the more urbanized province of Cusco only 18.22% of residents declared it their mother tongue. In rural provinces such as Calca, the percentage is higher, 69.91%. This indicates a process of language shift in urban areas that is usually preceded by extended bilingualism. As for Inuktitut, there is a large percentage of speakers (65.3%) who claim it as their first language and this percentage is higher than any other aboriginal language in Canada (

Allen 2007), but most of the population is bilingual (

Allen 2007;

Dorais 2010;

Statistics Canada 2019). As such, we can expect bi-directional influences affecting the morpho-syntax and/or the prosody of these languages, especially given the vast literature in bilingual studies that has shown that phenomena at the interface of language components are likely to exhibit crosslinguistic influence (see

Sorace 2011 and

White 2011a,

2011b; for general overviews). Of particular relevance to our proposal is Sorace’s

Interface Hypothesis according to which bilingual grammars are more susceptible to crosslinguistic influence at the interface of core components of the grammar such as syntax and external components such as information structure. We also draw on Slabakova and colleagues’ (

Slabakova 2009;

Cho and Slabakova 2014) proposal regarding the acquisition of overt and covert features in adult second language speakers. Thus, in this section, we spell out the predictions that would derive from our proposal regarding the interactions between morphology, syntax, and prosody (

Figure 8), and we test such predictions against different findings coming from recent experimental studies.

Based on general principles established in crosslinguistic influence research (

Sorace 2011) and on our view that there is a tendency in languages at the two extremes of the continuum of modular interaction to favor a division of labor between prosody and morphology at the interface with syntax and information structure, we make the general prediction that when Quechua or Inuktitut come into contact with Spanish and English, it is possible for the morphologically rich languages to be affected by the languages with rich prosodic patterns. It is also possible for the latter to be affected by the patterns of morpheme encoding of information structure found in Inuktitut and Quechua. Thus, a bidirectional influence is possible but there is an ordering in which the stages of influence work. In terms of the influence of prosody-oriented languages on morphology-oriented languages, we propose that the prosodic marking of sentence type will be transferred to these languages before the prosodic marking of focus (see

Table 4). This is because sentence type is encoded only in the morphology of the substratum languages, whereas focus is encoded both in the morphology and the syntax making sentence type encoding an easier target than focus for a switch from morphology to prosody. In fact, one could argue that prosody can be perceived as a more reliable cue for sentence type than focus at earlier stages of acquisition (

Mac Whinney 2012). As a reliable cue, it can be successful in competing with morphology among bilinguals who are dominant in Spanish or English. Moreover, we may need to keep in mind that there are differences in the relative complexity of each structure too. For example, choosing a sentence type—at least as concerns declaratives vs. yes/no questions—involves a binary option with a relatively unambiguous meaning, accompanied either by syntactic and prosodic marking (English) and redundant prosodic marking (Spanish). Focus, however, is more complex as it requires contextual information. Furthermore, and depending on the language, focus marking can have scope over the whole sentence or over a constituent.

13 Finally, although focus constituents are enhanced by redundant prosodic cues, it is less clear how focus is marked prosodically in different Spanish varieties. These differences between sentence-type and focus properties make sentence type in Quechua and Inuktitut more likely to be subject to crosslinguistic influence from the socially dominant languages and, at the same time, more likely to be acquired earlier than constituent focus in Spanish and English in contact situations.

The literature on language contact and intonation supports this general prediction, since it has been found that sentence type and focus appear to be at different levels. There is evidence that prosodic marking of sentence type can be acquired by different types of bilinguals (

Colantoni et al. 2018;

Marasco 2020;

Zárate-Sández 2015) but prosodic marking of focus is rarely acquired (e.g.,

Ortega-Llebaria and Colantoni 2014;

Nava and Zubizarreta 2010) or exhibits a protracted and gradual acquisition (

Leal et al. 2019). There is also the issue of which prosodic markers you are “choosing”. For example, Inuktitut speakers are good at using final rises and falls but they do not use pitch at the beginning of the utterance to mark sentence types.

Furthermore, in recent studies that explore the realization of sentence types there is evidence of influence of Spanish sentence type prosody among Quechua–Spanish bilinguals. Indeed, there is unpublished research by Antje Muntendam on Quechua speakers in contact with Spanish that exhibit rising intonation patterns in yes/no questions rather than the morphological marker. On the other hand, and to the best of our knowledge, there is no current evidence of the emergence of a yes/no morpheme (whether bound or independent) in Spanish in contact with Quechua.

While influence of sentence type prosody from Spanish into Quechua has been attested and no evidence of Quechua sentence type morphology in Spanish is available, studies concentrating on the prosodic realization of focus by Quechua–Spanish bilinguals have consistently observed that prosodic contours are not transferred from Spanish into Quechua but rather the other way around. This has been reported for Cusco Quechua–Spanish bilinguals both in read (

O’Rourke 2009,

2012) and semi-spontaneous speech (

Muntendam and Torreira 2016;

van Rijswijk and Muntendam 2014). O’Rourke studied declarative sentences with broad focus and contrastive focus on the subjects in the read speech of Quechua–Spanish bilinguals from Cusco, and Spanish monolinguals from Cusco and Lima. She found that Quechua–Spanish bilinguals and some Spanish monolinguals from Cusco did not use peak alignment to mark focus, as opposed to monolinguals from Lima, and suggested that these differences may be attributed to contact with Quechua. Muntendam and colleagues (

Muntendam and Torreira 2016;

van Rijswijk and Muntendam 2014) also reported influence from Quechua in the Spanish realization of noun phrases that had either broad focus or contrastive focus on the noun or the adjective. In summary, studies show that, as concerns the marking of focus, prosodic realizations found in Quechua are transferred into Spanish.

The influence of Spanish on Quechua regarding constituent focus seems to start not by affecting Quechua prosody but by affecting Quechua morphology first. Studies on some varieties of Quechua have reported evidence of influence from Spanish into Quechua in the dropping of the morphological marking of focus. Indeed,

Muntendam’s (

2015) work on Bolivian Quechua (from Tarata) shows that Quechua speakers in contact situations exhibit lack of morphological markers of contrastive focus. A range of possibilities was found. First, some participants in the study showed morphological marking of the subject topic when the object was contrastive with canonical SOV word order, as in (24).

| 24. | Mana. Runa-s-qa | yunta | wata-sa-nku |

| | No. Man-PL-TOP | yoke | tie-PROG-3.PL |

| | “No. The men are tying the yoke” (Muntendam 2015, Speaker 1) |

A mixed pattern was found in the production of SOV in a sentence with contrastive focus on the object with a conspicuous lack of a morphological marker on the subject topic or the object, as in (25):

Finally, there are patterns that are even ‘closer’ to Spanish in examples such as (26), where there is evidence of SVO word order with broad focus and, as in the previous case, there is no morphological marking of evidentiality/focus on any constituent at the sentence level, as shown by the lack of any type of evidentiality/focus suffixes:

These data suggest that there is an intermediate stage before Spanish focus prosody can directly influence Quechua that involves the dropping of morphological markers.

Turning to the influence of Quechua morphological marking on Spanish prosody marking of information structure, research on Quechua–Spanish bilinguals shows that speakers who are dominant in Quechua tend to generate discourse markers in Spanish that have equivalent or similar information structure properties to those of existing in Quechua (

Manley 2007;

Zavala 2001). In example (27) the speaker conveys along with the sentence meaning the source of the information, which in this case is ‘hearsay’ as indicated by the word “dice” at the beginning of the sentence. In other varieties of Spanish, the equivalent sentence would be

estaban caminando, dicen ‘(they) were walking, they say’ where

dicen does not refer to people actually saying something but conveys the notion that the information is hearsay.

| 27. | Dic-e | camin-ando | est-aban. |

| | Say-3.S | walk-GER | be.ASP-PST.IMP. 3.PL |

| | “Then (they) were walking” (reportative) (Cusco) (Sánchez 2015) |

In summary, regarding sentence type, there is a directionality such that Spanish prosody affects Quechua prosody, but Quechua sentence type morphology does not influence Spanish by generating sentence-type morphemes. Regarding constituent focalization, in contact varieties where Quechua is the dominant language, we see no transfer of intonational patterns from Spanish and conservation of morphological markers. Varieties that are heavily influenced by Spanish show a lack of morphological marking on focalized constituents but no clear evidence of transfer of intonational patterns. Conversely, Spanish varieties in contact with Quechua develop discourse-related morphological markers. This is shown in

Table 5:

We take these data to suggest some form of complementarity of prosody and morphology in Quechua–Spanish bilinguals as well as an ordering in which crosslinguistic influence takes place. Of course, further research is needed to support this possibility.

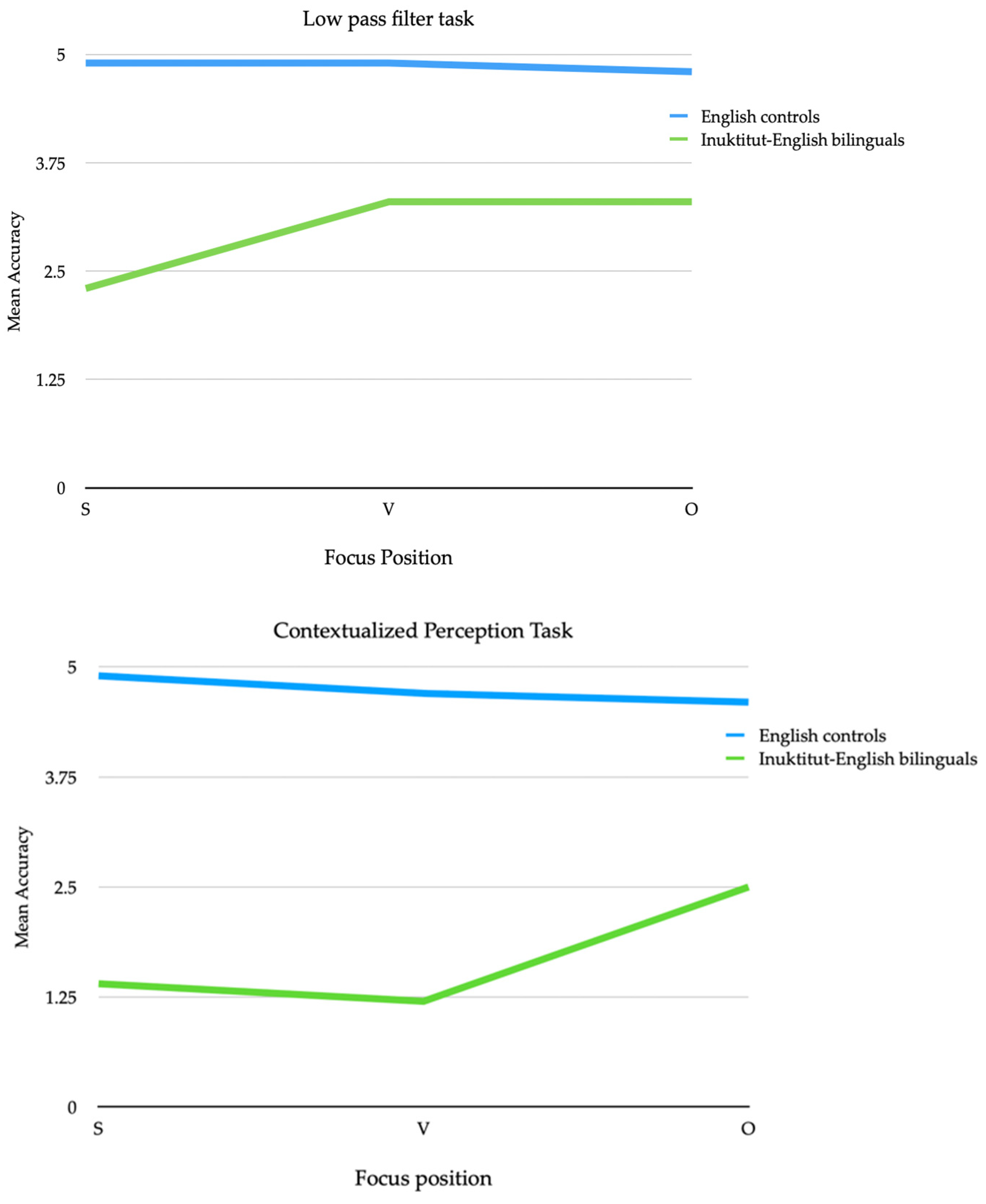

Much less is known about the consequences of language contact as concerns the realization of focus and sentence types in the case of Inuktitut–English bilinguals. As mentioned in

Section 3, research shows that, as it was the case with Cusco Quechua, bilinguals transfer prosodic patterns from Inuktitut to English, since differences were found in the perception and production of corrective focus (

Colantoni et al. 2014) when bilinguals were compared to monolinguals. Evidence of crosslinguistic influence in the realization of English statements, absolute yes/no questions, and declarative questions has also been reported recently (

Colantoni et al. 2018). This study, which included imitation of isolated sentences as well as production of the same sentence types in context, showed that Inuktitut–English bilinguals matched English monolinguals more closely in the realization of final contours than in the amount of pitch change observed in initial pitch accents. This is consistent with what was reported for their L1, since previous studies on Inuktitut and other Eskimo-Aleut languages observed that tonal movements were restricted to the last two syllables of an utterance. Finally, evidence that the Interrogative mood in Eskimo-Aleut languages may be substituted by rising contours comes from

Fortescue (

1983), who indicates that in Central Alaskan Yupik the interrogative mood morpheme is replaced by a rising contour in yes/no questions.

The general patterns reported in the literature for Quechua–Spanish and English–Inuktitut bilinguals, as well as some individual patterns described in

Muntendam’s (

2015) work, seem to correspond to different levels of realignment of the interface between information structure and syntax and morphology or phonology. This preliminary evidence supports our proposal of a complementary distribution of morphology and prosody at the interfaces in contact situations between the Quechua and Spanish and Inuktitut and English. Furthermore, it also seems to support our view, based on the higher reliability of prosody as a cue for sentence type, that transfer of sentence-type prosody is more likely to occur than transfer of constituent focus prosody. Conversely, given the lower levels of reliability of prosody as unequivocal encoding of constituent focus, and the fact that focus interpretation heavily relies on computing contextual information, one would expect that morphological or word-level marking of constituent focus would be more likely to occur among speakers who are dominant in Quechua or Inuktitut and have Spanish or English, respectively, as their non-dominant language. As such, our proposal is very much in line with Slabakova and colleagues’ (

Slabakova 2009;

Cho and Slabakova 2014) analysis of feature reassembly in second language acquisition.

14 According to their view (see

Slabakova 2009, p. 321), the easiest learning scenario is when no feature reassembly is required, i.e., when, in their framework, an inflectional morpheme in the L1 is mapped into an inflectional morpheme in the L2. Albeit not referring to inflectional morphemes, we could argue that this is a similar scenario as the one reported here when discussing sentence types. For example, questions are marked by a suffix in Quechua and are consistently prosodically marked by a higher initial pitch accent and a rising contour in Spanish. Thus, we would expect that a Quechua–Spanish bilingual would map the Quechua morphology into the Spanish prosody to signal questions. The most difficult learning situation, according to Slabakova and colleagues, is the one in which feature reassembly is required. In their view, this is represented by instances in which a feature encoded in the context in the L1 maps into a morpheme in the L2. We could argue that focalization in the languages under study here represents a similar, although not identical, scenario. That is, we saw, for example, that in Spanish focus could be signaled by syntactic and/or prosodic means, depending on the dialect. In English, if we exclude cleft constructions, focus is only marked by prosody. However, the features that are used to mark focus in both languages (e.g., higher f0 or larger f0 excursion) can also be used to express paralinguistic meanings. As such, the use of prosody may result in ambiguity. In Quechua, instead, focus is consistently marked by a suffix and possibly by syntactic movement. Thus, a bilingual would have to map a morpheme from Quechua into either syntax or prosody, taking into account contextual information. This would require some type of reassembly from morphology–syntax interaction to phonology–syntax interaction with context. We may expect, then, that Quechua–Spanish bilinguals resort to inserting a morpheme in Spanish. As we saw (see

Table 5), they tend not to use prosody to mark focus in Spanish and may insert lexical items to mark the focalized constituent and/or the source of information.

Finally, Muntendam’s data suggest that contact between morphologically rich languages, such as Quechua and Inuktitut, and intonational languages (Spanish, in particular) may also involve changes affecting aspects of the syntax such as word order. The extent to which syntax is affected needs to be explored. This is, of course, a preliminary proposal that needs to be tested by studies on bilingual acquisition of languages in the two extremes of the continuum of interfaces between information structure, syntax, and phonology, in one extreme and morphology in the other extreme.