New Perspectives on the Urban–Rural Dichotomy and Dialect Contact in the Arabic gələt Dialects in Iraq and South-West Iran

Abstract

:1. Introduction

On lacking definitions: What do ‘Bedouin’, ‘sedentary’, ‘urban’, and ‘rural’ mean in the context of the gələt and qәltu dialects?

Aims of This Paper

2. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- Rural gәlәt features as listed by Blanc and Palva:

- Use of the gahawa-syndrome (Section 3.1.3);

- Resyllabification of CaCaC-v(C) > CCvC-a(C) (Section 3.1.4);

- Retention of gender distinction in the plural of pronouns and verbs (Section 3.1.5).

- (ii)

- Further rural features suggested by the author of this paper:

- Raising (and elision) of *a in pre-tonic open syllables (Section 3.1.2);

- Imperative m.sg of final weak roots of the form ʔvCvC (Section 3.1.7).

3. Results

3.1. Rural gələt Features

3.1.1. Affrication of OA (Old Arabic) *q > g > ǧ and *k > č in the Vicinity of Front Vowels

3.1.2. Raising of OA *a in Pre-Tonic Open Syllables

3.1.3. gahawa-Syndrome

3.1.4. Resyllabification of OA CaCaC-v(C) > CCvC-a(C)

3.1.5. Retention of Gender Distinction in the Plural

3.1.6. Prefix tv- in Form V and Form VI Verbs

3.1.7. Imperative sg.m of Final Weak Roots: ʔvCvC

3.2. Reevaluating the Urban Character of MBA: A Question of Urban Features or Inherited qəltu Features?

3.2.1. Indefinite Article fadd ~ fard

3.2.2. Progressive Markers da- and gāʕid

3.2.3. Future Marker rāḥ

3.2.4. Emphatic Imperative Prefix d-

| də-xall | asōləf | xayya! |

| emp-hort | tell\ipfv.1sg | sister.dim |

3.2.5. Lack of Features: Feminine Plural Forms, Resyllabification Rules, and Form IV Verbs

3.3. Markedness of Rural Features—A Small-Scale Sociolinguistic Survey among Urban Iraqis

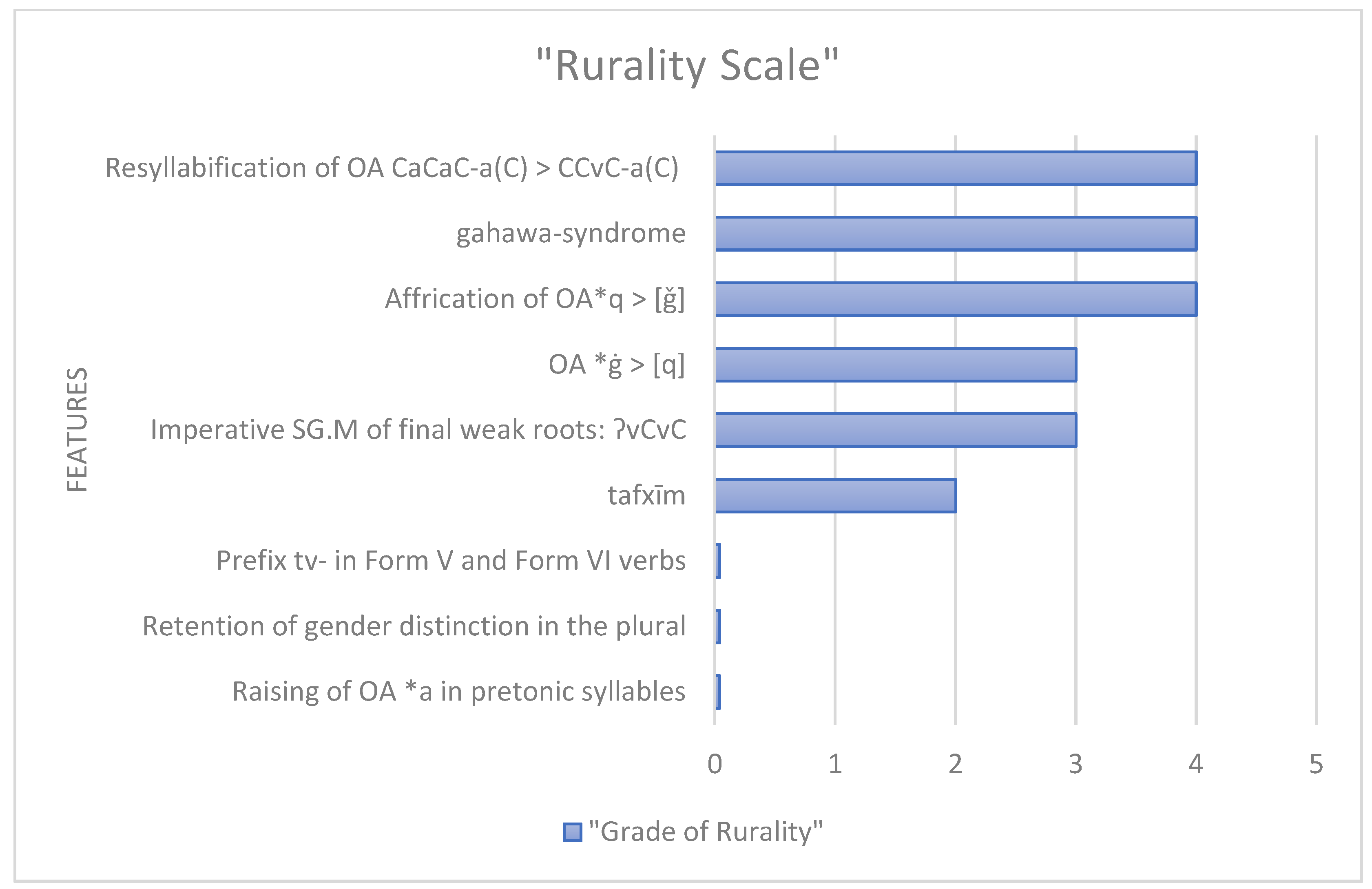

3.4. Case Study Ahvaz, Khuzestan: Urbanization of a Rural gәlәt Dialect

4. Discussion

4.1. Historical and Modern MBA and the Quest for Urban gələt

4.2. Who Speaks Urban gәlәt?

4.3. About Rural gələt and the Markedness of Rural Features

4.4. Linguistic Consequences of Urbanization

4.4.1. Loss of Features

4.4.2. Innovations

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| dim | Diminutive |

| emp | Emphatic marker |

| f | Feminine |

| hort | Hortative |

| imp | Imperative |

| ipfv | Imperfective |

| m | Masculine |

| MBA | Muslim Baghdad Arabic |

| OA | Old Arabic |

| pl | Plural |

| sg | Singular |

| 1 | I would like to express my gratefulness to my dear friends and colleagues Stephan Procházka and Ana Iriarte Díez as well as the reviewers for their valuable thoughts and critical remarks on draft versions of this article. |

| 2 | Following Haim Blanc’s classification of Mesopotamian Arabic dialects into gәlәt- and qәltu-type dialects. These terms are the 1sg pfv verb forms for ‘to say’ (cf. Blanc 1964, pp. 7–8) which indicate certain phonological and morphological characteristics of these dialect groups. |

| 3 | Compare, e.g., “rural g” (Palva 2009, p. 35) and “the voiced reflex of OA q is the most exclusive Bedouin feature” (op.cit.: 24). |

| 4 | Historically, probably all gәlәt dialects outside Arabia were Bedouin or Bedouinized dialects (cf. Blanc 1964, pp. 167–68). |

| 5 | The term ‘Šāwi-type Bedouin Arabic’ is used here to refer to a bundle of closely related dialects spoken by semi-nomads in various regions of the Fertile Crescent. Typologically similar dialects are found in many rural parts of Iraq, which is why the Šāwi and the rural Iraqi gələt-type dialects are often grouped together as ‘Syro-Mesopotamian (fringe) dialects’ or pre-ʕAnazī dialects (Palva 2006, p. 606). |

| 6 | At the time Haim Blanc wrote his book on the Arabic dialects of Baghdad, the main scientific data available on gələt dialects were limited to (Meißner 1903; Weissbach 1968) on Kwayriš, his own data from one informant from the Musayyib district, and (Van Wagoner 1944) as well as his own data on the Arabic spoken in the Amarah district. |

| 7 | The sources used for Table 1 are: (Leitner 2020) for Khuzestani Arabic; (Meißner 1903) and (Denz 1971, which is based on Meißner 1903 and Weissbach 1908) for Kwayriš, (Salonen 1980) for al-Shirqat, (Seeger 2013, 2002; Volkan Bozkurt, pers. comm.) for Khorasan, (Behnstedt 1997; Bettini 2006; Jastrow 1996; Fischer and Jastrow 1980; Procházka 2003, 2018a; 2018b; Younes and Herin n.d., EALL online) for Šāwi Arabic, and (Mahdi 1985) for Basra, (Leitner et al. 2021; Blanc 1964) for Muslim Baghdad Arabic (MBA); as well as (Palva 2009) and (Hanitsch 2019, pp. 266–71). |

| 8 | The sources are in fact contradictory on this question: while Mahdi (1985, pp. 94–106, 152–55) provides feminine plural forms for verbs and pronouns, Ingham (1982, p. 38) states that gender distinction in the plural has been given up in urban centers, such as Basra. |

| 9 | It is important to note that MBA shows interdialectal variation due to the subsequent immigration of rural people to the city; cf. Abu-Haidar (1988) on a number of phonological differences. |

| 10 | Blanc (1964, p. 204) reports that, even though the town was historically rather stable in comparison to most other towns in Lower Iraq, the population of Hilla has been Bedouin since its foundation; cf. Oppenheim 1952, pp. 185, 189, who writes that Hilla was deserted after the second Mongol invasion in the fourteenth century. |

| 11 | In several dialects, the raised vowel was elided subsequently, e.g., Khuzestani Arabic (ә)mrākәb ‘boats’ < *mərākəb < OA *marākibu. |

| 12 | |

| 13 | Ingham (1976, p. 64; 1997, p. x) discerns three main socio-economical groups in Khuzestan: the ʕarab, the ḥaḏ ̣ar, and the marsh Arabs. While the term ʕarab denotes a group of larger territorially organized tribes, who live—sometimes as semi-nomads—away from the river in the plain (bādiya) and are involved in occupations such as cereal, rice, and date cultivation, sheep herding, and water buffalo breeding, the ḥaḏ ̣ar group are riverine palm-cultivating Arabs of mixed tribal descent, who live along the banks of the Shatt al-Arab and the lower parts of the river Karun. Ingham notes that while the ʕarab dialect shows “considerably more resemblance to the dialects of Arabia”, the ḥaḏ ̣ar was “more strictly Mesopotamian” (Ingham 1997, p. ix). Cf. Ingham (2009) on some ‘fringe’ Bedouin dialects in Kuwait and north west of Nasiriyah, which share features with both the southern Mesopotamian gələt group, e.g., affrication of OA *k > č and *q > ǧ, and the northern Najdi dialects. |

| 14 | Cf. Ingham (1976, p. 74), who contrasts ‘nomadic’ forms like taḥāča and ‘sedentary’ forms like tḥāča; elsewhere, Ingham describes the prefix sequence CCv- in such structures, e.g., ntaʕašša, as rural (Ingham 1973, p. 541). |

| 15 | In Khuzestani Arabic, the active participle form rāyəḥ f rāyḥa is also used to express future intent (āna rāyḥa (a)sawwī-lak ‘I will make (for) you...’). We also find Khuzestani Arabic sentences with future reference that do not feature any future particle. In such cases, future reference is usually indicated by an ipfv verb or an active participle together with a temporal adverb like ‘tomorrow’ or ‘soon’. |

| 16 | There is one instance of rāḥ and two instances of rāyeḥ used as future markers in Salonen’s texts: rāḥ teḥergu ‘it will burn him’ (Salonen 1980, pp. 13 and 33, Text 3, sentence 8), rāyeḥ yiṭlaʕ ‘he will come up’, rāyeḥ yiġrag ‘he will drown’ (Salonen 1980, pp. 14 and 34, Text 4, sentence 4). |

| 17 | Of course, this particle is less common in narratives than in conversations and the fact it does not appear in these texts from al-Shirqat might be attributed to the nature of the text genre and must not necessarily mean that it does not exist in this Arabic variety. |

| 18 | The grade of rurality of a certain feature was measured quantitatively by the number of its mentions by the interviewees as a rīfi ‘rural’ feature. This means, if a feature reaches, for example, the number 3 on the ‘Rurality Scale’, three of the five interviewees have described this feature as typical of rural dialects. |

| 19 | Participant C, in contrast, stated that the form xašš was used in Baghdad as well, but only by elderly women. |

| 20 | Cf. Hassan (2020, 2021), who uses this term for dividing the Iraqi Arabic dialects into a northern and a southern group (the latter being associated with the term šrūgi), even though he acknowledges its pejorative and derogatoriy use (Hassan 2021, p. 52). |

| 21 | Cf. Blanc (1964, p. 170): “In the fourteenth century, the Baghdad Muslims were still speaking a qəltu type dialect…”. |

| 22 | Blanc also refers to the dialect of the town of Qal’at Saleh as a representative of the urban group. The only description of this dialect, however, is an unpublished dissertation (Van Wagoner 1944) not available to the author of this paper. |

| 23 | Although we did not find evidence for the use of Feature 6 in the one source that exists for al-Shirqat, we cannot rule out that it does not exist in this variety. It is, however, also absent in the modern dialect of the city of Ahvaz. |

References

- Abd-el-Jawad, Hassan R. 1986. The Emergence of an Urban Dialect in the Jordanian Urban Centers. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 61: 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Haidar, Farida. 1988. Speech Variation in the Muslim Dialect of Baghdad: Urban vs. Rural. Zeitschrift Für Arabische Linguistik 19: 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Haidar, Farida. 2002. Negation in Iraqi Arabic. In “Sprich Doch Mit Deinen Knechten Aramäisch, Wir Verstehen Es!": 60 Beiträge Zur Semitistik. Festschrift Für Otto Jastrow Zum 60. Geburtstag. Edited by Werner Arnold and Hartmut Bobzin. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Behnstedt, Peter. 1997. Sprachatlas von Syrien. I: Kartenband. Semitica Viva 17. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Behnstedt, Peter. 2000. Sprachatlas von Syrien. II: Volkskundliche Texte. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Bettega, Simone, and Bettina Leitner. 2019. Agreement Patterns in Khuzestani Arabic. Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Des Morgenlandes 109: 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bettini, Lidia. 2006. Contes Féminins de La Haute Jézireh Syrienne. Matériaux Ethno-Linguistiques d’un Parler Nomade Oriental. Florence: Dipartimento di Linguistica. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, Haim. 1964. Communal Dialects in Baghdad. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Denz, Adolf, and Otto Edzard. 1966. Iraq-arabische Texte nach Tonbandaufnahmen aus al-Hilla, al-‘Afač und al-Baṣra. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 116: 60–96. [Google Scholar]

- Denz, Adolf. 1971. Die Verbalsyntax des neuarabischen Dialektes von Kwayriš (Irak): Mit einer einleitenden allgemeinen Tempus- und Aspektlehre. Wiesbaden: Steiner. [Google Scholar]

- Ech-charfi, Ahmed. 2020. The Expression of Rural and Urban Identities in Arabic. In The Routledge Handbook of Arabic and Identity. Edited by Reem Bassiouney and Keith Walters. London: Routledge, pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Wolfdietrich, and Otto Jastrow. 1980. Handbuch Der Arabischen Dialekte. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Grigore, George. 2019. Deontic Modality in Baghdadi Arabic. In Studies on Arabic Dialectology and Sociolinguistics: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference of AIDA Held in Marseille from May 30th to June 2nd 2017. Edited by Catherine Miller, Alexandrine Barontini, Marie-Aimée Germanos, Jairo Guerrero and Christophe Pereira. Livres de l’IREMAM. Aix-en-Provence: IREMAM, Available online: https://books.openedition.org/iremam/3917 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Häberl, Charles. 2019. Mandaic. In The Semitic Languages. Edited by John Huehnergard and Na’ama Pat-El. Milton: Routledge, pp. 679–710. [Google Scholar]

- Hanitsch, Melanie. 2019. Verbalmodifikatoren in den arabischen Dialekten: Untersuchungen zur Evolution von Aspektsystemen. Porta Linguarum Orientalium 27. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Qasim. 2016a. Concerning Some Negative Markers in South Iraqi Arabic. In Arabic Varieties: Far and Wide. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference of AIDA—Bucharest, 2015. Edited by George Grigore and Gabriel Bițună. Bucharest: Editura Universității din București, pp. 301–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Qasim. 2016b. The Grammaticalization of the Modal Particles in South Iraqi Arabic. Romano-Arabica 16: 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Qasim. 2017. On the Synonymous Repetition of Greeting Questions in South Iraqi Arabic: A Sociopragmatic Study. In The International Scientific Conference: Oriental Studies—Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow/8th December 2016. University of Belgrade, Department of Oriental Studies. Belgrad: Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrad, pp. 429–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Qasim. 2020. Reconsidering the Lexical Features of the South-Mesopotamian Dialects. Folia Orientalia LVII: 183–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Qasim. 2021. Phonological Evidence for the Division of the Gǝlǝt Dialects of Iraq into Šrūgi and Non-Šrūgi. Kervan—International Journal of Afro-Asiatic Studies 25: 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Holes, Clive. 1995. Community, Dialect and Urbanization in the Arabic-Speaking Middle East. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 58: 270–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holes, Clive. 2001. Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia. Vol. 1: Glossary. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Holes, Clive. 2016. Dialect, Culture, and Society in Eastern Arabia. Vol. 3: Phonology, Morphology, Syntax, Style. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, Bruce. 1973. Urban and Rural Arabic in Khūzistān. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 36: 523–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, Bruce. 1976. Regional and Social Factors in the Dialect Geography of Southern Iraq and Khuzistan. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 39: 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, Bruce. 1982. North East Arabian Dialects. London: Kegan Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, Bruce. 1997. Arabian Diversions: Studies on the Dialects of Arabia. Reading: Ithaca Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, Bruce. 2007. Khuzestan Arabic. In Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Leiden: Brill, vol. 2, pp. 571–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ingham, Bruce. 2009. The Dialect of the Euphrates Bedouin, a Fringe Mesopotamian Dialect. In Arabic Dialectology. In Honour of Clive Holes on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday. Edited by Enam Al-Wer and Rudolf de Jong. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Jastrow, Otto. 1996. The Shawi Dialects of the Middle Euphrates Valley. In Encyclopaedia of Islam. 376a-b. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, Thomas M. 1967. Eastern Arabian Dialect Studies. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kerswill, Paul. 2013. Koineization. In The Handbook of Language Variation and Change. Edited by J. K. Chambers and Natalie Schilling. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 519–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, Bettina, and Stephan Procházka. 2021. The Polyfunctional Lexeme /Fard/ in the Arabic Dialects of Iraq and Khuzestan: More than an Indefinite Article. Brill’s Journal of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 13: 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, Bettina, Fady German, and Stephan Procházka. 2021. Lehrbuch des Irakisch-Arabischen: Praxisnaher Einstieg in den Dialekt von Bagdad. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, Bettina. 2019. Khuzestan Arabic and the Discourse Particle ča. In Livres de l’IREMAM. Edited by Catherine Miller, Alexandrine Barontini, Marie-Aimée Germanos, Jairo Guerrero and Christophe Pereira. Aix-en-Provence: IREMAM, Available online: https://books.openedition.org/iremam/3939 (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Leitner, Bettina. 2020. The Arabic Dialect of Khuzestan (Southwest Iran): Phonology, Morphology and Texts. Vienna: University of Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi, Qasim R. 1985. The Spoken Arabic of Baṣra, Iraq: A Descriptive Study of Phonology, Morphology and Syntax. Ph.D. dissertation, Exeter University, Exeter, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Meißner, Bruno. 1903. Neuarabische Geschichten Aus Dem Iraq. Beiträge Zur Assyrologie Und Semitschen Sprachwissenschaft 5: 203. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Catherine. 2007. Arabic Urban Vernaculars: Development and Change. In Arabic in the City: Issues in Dialect Contact and Language Variation. Edited by Catherine Miller, Enam Al-Wer, Dominique Caubet and Janet C. E. Watson. London: Routledge, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nejatian, Mohammad Hossein. 2015. Ahvaz Iv. Population, 1956–2011. In Encyclopaedia Iranica Online Edition. Available online: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/ahvaz-04-population (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- Oppenheim, Max Freiherr von. 1952. Die Beduinen. Band III: Die Beduinenstämme in Nord- Und Mittelarabien Und Im Irāk. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, Max Freiherr von. 1967. Die Beduinen: 4,1: Die Arabischen Stämme in Chūzistān (Iran). Pariastämme in Arabien. Leipzig: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Palva, Heikki. 2006. Dialects: Classification. In Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Edited by Kees Versteegh. Leiden: Brill, vol. 1, pp. 604–13. [Google Scholar]

- Palva, Heikki. 2009. From qǝltu to gələt: Diachronic Notes on Linguistic Adaptation in Muslim Baghdad Arabic. In Arabic Dialectology. In Honour of Clive Holes on the Occasion of His Sixtieth Birthday. Edited by Rudolf de Jong and Enam Al-Wer. Leiden & Boston: Brill, pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pellat, Charles, and Steven Helmsley Longrigg. 2012. Al-Baṣra. In Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Edited by Peri Bearman, Thierry Bianquis, Clifford Edmund Bosworth, Emeri Johannes van Donzel and Wolfhart Heinrichs. Online. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Procházka, Stephan. 2003. The Bedouin Arabic Dialects of Urfa. In AIDA: 5th Conference Proceedings, Association Internationale de Dialectologie Arabe (AIDA): Cádiz, September 2002. Edited by Ignacio Ferrando and Juan José Sánchez Sandoval. Cadiz: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz, pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Procházka, Stephan. 2014. Feminine and Masculine Plural Pronouns in Modern Arabic Dialects. In From Tur Abdin to Hadramawt: Semitic Studies. Festschrift in Honour of Bo Isaksson on the Occasion of His Retirement. Edited by Tel Davidovich, Ablahad Lahdo and Torkel Lindquist. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 129–48. [Google Scholar]

- Procházka, Stephan. 2018a. The Arabic Dialects of Eastern Anatolia. In The Languages and Linguistics of Western Asia. Edited by Geoffrey Haig and Geoffrey Khan. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 159–89. [Google Scholar]

- Procházka, Stephan. 2018b. The Northern Fertile Crescent. In Arabic Historical Dialectology: Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Approaches. Edited by Clive Holes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 257–92. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen, Erkki. 1980. On the Arabic Dialect Spoken in Širqāṭ (Assur). Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger, Ulrich. 2002. Zwei Texte Im Dialekt Der Araber von Chorasan. In “Sprich Doch Mit Deinen Knechten Aramäisch, Wir Verstehen Es!“ 60 Beiträge Zur Semitistik. Festschrift Für Otto Jastrow Zum 60. Geburtstag. Edited by Werner Arnold and Hartmut Bobzin. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 629–46. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger, Ulrich. 2009. ‘Khalaf – Ein Arabisches Dorf in Khorasan’. In Philologisches Und Historisches Zwischen Anatolien Und Sokotra: Analecta Semitica in Memoriam Alexander Sima. Edited by Werner Arnold, Michael Jursa, Walter W. Müller and Stephan Procházka. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 307–17. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger, Ulrich. 2013. Zum Verhältnis Der Zentralasiatischen Arabischen Dialekte. In Nicht Nur Mit Engelszungen. Beiträge Zur Semitischen Dialektologie: Festschrift Für Werner Arnold Zum 60. Geburtstag. Edited by Renaud Kuty, Ulrich Seeger and Shabo Talay. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 313–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkawi, Muhammad al-. 2014. Urbanization and the Development of Gender in the Arabic Dialects. Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 14: 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taine-Cheikh, Catherine. 2004. Le(s) futur(s) en arabe. Réflexions pour une typologie. Estudios de Dialectología Norteafricana y Andalusí 8: 215–38. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wagoner, Merrill Y. 1944. A Grammar of Iraqi Arabic. Unpublished dissertation. New Haven: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, Janet C. E. 2011. Arabic Dialects (General Article). In The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Edited by Stefan Weninger. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 851–95. [Google Scholar]

- Weissbach, Franz Heinrich. 1968. Beiträge Zur Kunde Des Irak-Arabischen. Leipzig: J.C. Heinrichs’sche Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Younes, Igor, and Bruno Herin. n.d. ‘Šāwi Arabic’. In Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. Online Edition. Leiden: Brill.

- Younes, Igor. 2018. Raising and the Gahawa-Syndrome, between Inheritance and Innovation. Zeitschrift Für Arabische Linguistik 67: 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rural Features | Khuzestan | Kwayriš | al-Shirqat | Khorasan | Šāwi | Basra | Muslim Baghdad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Affrication of *q in front vowel environment | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| II. Raising of *a in pre-tonic open syllables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| III. gahawa-syndrome | Only a few remnants | Yes | Only a few remnants | Yes | Yes | Only a few remnants | No |

| IV. CaCaC-a(C) > CCvC-a(C) | Partly | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| V. Gender distinction in the plural | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes?8. | Partly |

| VI. Form V and VI prefix tv- | Partly | Partly | Yes | Arabkhane: ti- Khalaf: it- | Yes | No | No |

| VII. Imperative sg.m of weak verbs: ʔvCvC | Partly | Partly | No evidence found | Yes | Partly | No | No |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leitner, B. New Perspectives on the Urban–Rural Dichotomy and Dialect Contact in the Arabic gələt Dialects in Iraq and South-West Iran. Languages 2021, 6, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040198

Leitner B. New Perspectives on the Urban–Rural Dichotomy and Dialect Contact in the Arabic gələt Dialects in Iraq and South-West Iran. Languages. 2021; 6(4):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040198

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeitner, Bettina. 2021. "New Perspectives on the Urban–Rural Dichotomy and Dialect Contact in the Arabic gələt Dialects in Iraq and South-West Iran" Languages 6, no. 4: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040198

APA StyleLeitner, B. (2021). New Perspectives on the Urban–Rural Dichotomy and Dialect Contact in the Arabic gələt Dialects in Iraq and South-West Iran. Languages, 6(4), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040198