Abstract

The distinction between function words and content words poses a challenge to theories of the syntax–prosody interface. On the one hand, function words are “ignored” by the mapping algorithms; that is, function words are not mapped to prosodic words. On the other hand, there are numerous accounts of function words which form prosodic words and can even be analysed as heads of larger prosodic units. Furthermore, function words seem to be a driving factor for the formation of prosodic structures in that they can largely be held accountable for the non-isomorphism between syntactic and prosodic constituency. This paper discusses these challenges with a focus on a particular function word, and the first-person nominative pronoun in Swabian, a Southern German dialect. By means of two corpus studies, it is shown that the pronoun occurs in two forms, the prosodic word [i:] and the enclitic [ə]. Depending on clause position and focus structure, the forms occur in complementary distribution. Occurrences of n-insertion allow for the establishment of a recursive prosodic word structure at the level of the phonological module. The findings support a new proposal in the form of a two-tier mapping approach to the interface between syntax and prosody.

1. Introduction

For decades, the distinction between function words and content words1 has been a challenge to mapping algorithms between syntax and prosody, and to the formation of the p(honological)-structure itself.2 A majority of theories (a.o., Nespor and Vogel 1986; Selkirk 2011; Truckenbrodt 1999) assumes that function words are ignored by the mapping constraints at the interface: In contrast to content words, function words are not mapped to prosodic words per se. Instead, they are assumed to be subject to prosodic well-formedness constraints and are prosodically phrased together with content words, which they share a syntactic structure with (e.g., Ito and Mester 2009; Selkirk 1995).

At the same time, there are numerous accounts of function words which form prosodic words by themselves, or which can be held accountable for the frequent occurrences of non-isomorphism between syntactic and prosodic constituency (see, for example, Shattuck-Hufnagel and Turk 1996 for a discussion). These cases challenge the across-the-board mapping distinction between function words and content words based on syntactic word categories alone, but support a more fine-grained mapping algorithm at the interface.

This paper will focus on one of these challenging function words, the first-person singular nominative (hence: 1SgNom) pronoun in Swabian, a Southern German dialect. In contrast to Standard German, where the 1SgNom pronoun is represented by the single form ich, Swabian has two distinct pronouns, [i:] and [ə]3 (see also Bohnacker 2013; Haag-Merz 1996). The following example illustrates:

- 1.

- ... schlag ə a Süpple vor wo bloß i =s Rezept kenn... suggest I.1sg.nom a soup.dim part, where only I.1sg.nom =det recipe know‘(For the beginning,) I suggest a soup of which only I know the recipe.’(Uderzo and Goscinny 2017, p. 26)

The two forms of the 1SgNom pronoun offer interesting insights into the mapping constraints at the interface. As will be shown below by means of corpus studies in written and spoken Swabian, the two forms occur in complementary distribution and differ in their respective prosodic representations: [i:] is a full prosodic word and only occurs in clause-initial and/or focussed positions, while [ə] is an enclitic and only occurs in non-initial, non-focussed positions. The fact that a single syntactic pronoun can be represented by two different prosodic representations suggests that a differentiation between function words and content words cannot be based on syntactic structure (or semantics) alone—a claim that has also been made in previous literature, as discussed in Section 2.

As a consequence of these diverging prosodic representations, the two forms are also phrased differently at the level of the p-structure. While [i:] is a full prosodic word, the enclitic [ə] is phrased together with a preceding host in a recursive prosodic word structure. Evidence for this claim comes from (optional) Swabian n-insertion, where -n- can be inserted between two words to prevent a vowel hiatus.

- 2.

- waisch du wo=(n-)ə des habknow.2sg.prs 2sg.nom where=(n-)1sg.nom this have.1sg.prs‘Do you know where I keep this?’

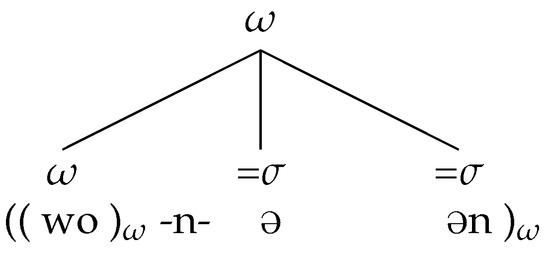

Swabian n-insertion is highly restricted at the level of a p-structure, in that it can only occur between a prosodic word and a preceding or following clitic. It can neither occur between two prosodic words, nor can it occur between two clitics. This limitation to the occurrence of n-insertion allows for deeper insights into the prosodic integration of the pronoun’s two forms. As will be discussed in more detail in Section 4, the occurrence of n-insertion allows us to infer that the enclitic [ə] is placed within the outer shell of a recursive prosodic word (), while [i:] can form the head of a recursive prosodic word itself ().

These recursive structures are not predicted by syntactic structure and the mapping algorithms at the interface between syntax and prosody, but are determined by principles native to the phonological module alone (where they are often referred to as “wellformedness constraints”). However, these principles are likewise dependent on a detailed prosodic representation of the individual forms—in the cases discussed here, this would be the information on whether the pronouns are prosodically weak or strong, which is essential for the establishment of, for example, a recursive prosodic word structure. This information should be established at the interface between the syntax and p-structure, but current mapping algorithms at the word-level only distinguish between function words and content words based on the morphosyntactic word category (D for pronouns) and do not allow for a more fine-grained representation of the variation found especially within the group of function words.

Based on the findings in previous works and on the results of the two corpus studies, this paper proposes a new, two-tier approach to the interface between syntax and prosody, where the mapping at the level of the (prosodic/syntactic) word is treated differently from the mapping of larger (prosodic/syntactic) constituents. Instead of a global mapping constraint based on syntactic terminal nodes, the mapping constraint at the word level proposed in this paper allows for a more fine-grained prosodic representation by matching each word’s individual syntactic form with its associated phonological form.

The formalisation of this new proposal will be undertaken in the framework of Lexical-Functional Grammar (LFG; Bresnan and Kaplan 1982), which assumes a constraint-based, modular structure. Modules like syntax, p(honological)-structure (including prosody), and i(nformation)-structure each have their own representations and are subject to their own principles and constraints. At the same time, there are mathematically well-defined projections between these modules which constrain the possible structures (see Bresnan et al. 2016; Dalrymple 2001 for details and formalisations of constraints).4 LFG furthermore follows a lexicalist approach with a rich lexicon, and assumes the principle of lexical integrity which states that only morphologically complete words enter the syntactic tree (Bresnan and Mchombo 1995). Morphological and phonological constraints are typically expressed in the form of finite-state relations (Beesley and Karttunen 2003; Kaplan and Kay 1994, see footnote 28 for a very short introduction).

While the formalisation of the new approach presented in Section 5 is based on LFG, the proposed solution is framework-independent and is easily adaptable to other constraint-based frameworks. For this reason, the reference to LFG is reduced to a minimum, and a discussion in more general terms is pursued throughout the paper.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 discusses different aspects of function words and how these are accounted for in theoretical approaches to the interface and p-structure in general. Section 3 analyses the Swabian 1SgNom pronoun based on two sources: One is a collection of two Asterix comics (Uderzo and Goscinny 2017) translated into the Swabian dialect, the other a corpus of spoken Swabian from a larger corpus containing a number of German dialects (Zwirner Corpus 2012). Section 4 discusses the findings from the corpus with respect to the prosodic phrasing of function words in p-structure. Based on these elaborations, Section 5 proposes a new, two-tier approach to the interface, which can account for the variation found with pronouns, but also offers perspectives for related phenomena discussed in previous literature.

2. Function Words

Function words and content words are generally distinguished in terms of meaning and “function” in a clause (cf. Fries 1940): Function words are assumed to have little meaning, but rather indicate relationships between other words, while content words are assumed to have meaning in that they describe, for example, an entity, an action, or an attribute. Other terms that have been used for these groups are “closed-class words” and “open-class words” based on whether it is possible to add new words to the group, and “grammatical words” and “lexical words”, which were born out of the traditional linguistic distinction between the grammar and the lexicon (Chomsky 1965).

However, so far, clear-cut differences between these two groups have not been established. Instead, numerous studies from different subfields conclude that function words and content words are not categorical, but rather seem to form a continuum, and that terms used to describe these groups are often misleading. For example, Zwarts (1997) discusses prepositions, which are generally grouped with the function words, but which can also carry meaning (i.e., content). Boye and Bastiaanse (2018) looked at grammatical (Aux) and lexical (V) instances of Dutch hebben “have” and showed that the distinction between the two groups based on the criteria of open and closed class and function and content word cannot be easily upheld. This is also supported by numerous works on grammaticalization phenomena (see Narrog and Heine 2011 for an overview) and by words like why and then, which are function words from a semantic perspective, but belong to the “lexical” category of adverbs from a syntactic perspective. Finally, by means of a lexical decision task and an experiment on eye fixation, Schmauder et al. (2000) showed that both groups are similarly accessed and stored in the mental lexicon, which challenges the traditional grammatical vs. lexical word distinction. Instead, these findings suggest that both function words and content words are part of the mental lexicon (see also Lange et al. 2017).

All of these (and other) studies show that although many function words and content words tend to have features specific to their group, there is also a considerable number of representatives which seem to be placed between these two groups, and which cannot be clearly categorized based on semantic or syntactic properties alone. The following section shows that this is likewise true for the prosodic representation of function words and content words.

In lack of a better class definition, this paper will use the terms “function words” and “content words” for two reasons. Firstly, the term function word is the most frequently used across all linguistic subdisciplines, and secondly, these two terms avoid the theoretical pre-assumptions that come with the grammatical/lexical word distinction, and the too-narrow definition of the open- and closed-class words. With respect to the interface between syntax and prosody, the paper adapts the classifications made in earlier works (a.o., Selkirk 2011; Truckenbrodt 1999) and associates function words with word categories like articles, pronouns, auxiliary verbs, and conjunctions, and content words with nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. However, at least for the interface between syntax and prosody, this differentiation between function words and content words based on a syntactic category will ultimately be rejected in favour of a more fine-grained representation.

2.1. The Phonological Representation of Function Words

Function words in English are mostly described as phonologically reduced (”weak”), stressless material. These reductions can be expressed, for example, via a loss of segments, reduced vowel quality, contractions, appearance of syllabic sonorants, or decreased duration (Cutler 1993; Jurafsky et al. 2001; Selkirk 1995; Sweet 1890). In contrast, content words are assumed to contain at least one “strong” syllable carrying primary stress.

However, as briefly mentioned above, the two groups cannot be clearly separated based on these criteria alone. Instead, the fact that function words are more likely to be reduced seems to correlate with their frequency and/or predictability in a given context. There are only a few hundred function words in English which consequently make up only a small part of a native speaker’s vocabulary, but most of these function words are highly frequent. Cutler and Carter (1987) looked at a corpus of 200,000 tokens of spoken English and found that 59% of the tokens were function words. With respect to the distribution of strong and weak syllables, however, they found that only 14% of the overall number of strong syllables, but 72% of the total of weak syllables occurred with function words. In short, the function words that were much more frequently found are disproportionally more likely to consist of weak syllables in comparison to content words.

More evidence for the correlation of acoustic salience and frequency/contextual predictability can be found in studies like Jurafsky et al. (2001) who showed that highly frequent function words and function words with a high probability given previous and following material are more likely to be acoustically reduced in comparison to function words with lesser frequency and/or predictability; that is, increased likelihood correlated inversely with function word duration. Interestingly, a similar study showed that the same effect can be found for highly frequent content words (Bell et al. 2009, see also references therein), and, independently of word category, phonological reduction and deletion have been shown to occur if the material is already given and/or (highly) predictable (Baumann 2006; Bennett et al. 2019; Merchant 2001; Rooth 1992; Tancredi 1992). In short, differences in the phonological realisation between the members within each of the two groups are well-established.

It can thus be concluded that while function words show a general tendency for phonological reduction, this reduction is neither universal nor is it restricted to function words. Function words can have “strong” representations, and content words can be phonologically reduced or even deleted. It is rather more likely that reduced phonological form correlates with frequency/predictability (among other factors, for example, focus structure, phonological weight or size), and not with word category per se, and that, due to their highly frequent nature, function words are disproportionately affected by this correlation. Consequently (and adding to the discussion in the previous section), there does not seem to be much evidence for a clear-cut difference between function words and content words with respect to their phonological realisations. Instead, the findings point towards a multi-factored continuous scale between prosodically strong and weak forms.

These findings are not reflected in the previous approaches to the interface between syntax and prosody. Instead, these models aim to express these mere tendencies by categorically excluding function words from being mapped to prosodic words.

2.2. Function Words at the Syntax–Prosody Interface

Very early on, function words have been excluded from mapping processes at the interface (see, for example, the Principle of the Categorial Invisibility of Function Words in Selkirk (1984)). Approaches working with edge-alignment (Chen 1987; Selkirk 1986) allow only for the association of lexical words and their phrasal projections to prosodic words and phonological phrases, and vice versa (in particular Selkirk 1995). This restriction was further refined in later research, for example in the Lexical Category Condition.

- 3.

- Lexical Category Condition (LCC): Constraints relating to syntactic and prosodic categories apply to lexical syntactic elements and their projections, but not to functional elements and their projections, or to empty syntactic elements and their projections. (Truckenbrodt 1999, p. 226)

The widely adopted Match Theory (Selkirk 2011) proposes that every syntactic clause corresponds to an intonational phrase (Match-clause, ), every XP corresponds to a phonological phrase (Match-phrase, ), and every (lexical) word corresponds to a prosodic word (Match-word, ), and vice versa.5

When taken by themselves, Match constraints predict a strong tendency for isomorphic syntactic and prosodic constituents, and recursive prosodic structures for the levels above the word (following earlier proposals by, for example, Ladd 1986; see also Wagner 2005). However, the matched structures are also subject to p-structure principles (e.g., wellformedness constraints like BinMin and StrongStart) which can enforce mismatches between syntactic and prosodic constituency.

Match Theory also incorporates the previously established distinction between function words and content words in that function words and their syntactic projections are not matched to prosodic words or phonological phrases, respectively. Evidence for this comes from mismatches between prosodic and syntactic structure—for example, cases where a function word encliticizes to the phonological unit projected by the previous XP. In the following abstract example from Selkirk (2011, p. 453), the function word (fnc) would be predicted to form a phonological phrase with the following NP if Match-phrase was applied indiscriminately to both function words and content words and their projections (as illustrated in 4a). However, as Selkirk notes, the function word is actually grouped with the previous verb (as in 4b), causing extensive non-isomorphism between syntactic and prosodic constituency.6

- 4.

- [ verb [ fnc NP ] ]

- a.

- ( verb ( fnc ( NP ) ) )

- b.

- ( verb fnc ( NP ) )

This mismatch can be explained if functional phrases are invisible to the mapping constraints; that is, functional phrases are not mapped to phonological phrases. The “unmapped” function word is then prosodically grouped according to language-specific constraints; in the case of (4), to the preceding verb.

This strict exclusion of functional projections has been questioned in Elfner (2012) (see also Elfner 2015; Ito and Mester 2013). In her work on Connemara Irish pitch accent distribution, Elfner was able to show that functional projections are indeed projecting phonological phrases if (and only if) they contain open phonological material that is not covered by another projection. She redefines Match-phrase accordingly:

- 5.

- match-phrase: Suppose there is a syntactic phrase (XP) in the syntactic representation that exhaustively dominates a set of one or more terminal nodes . Assign one violation mark if there is no phonological phrase () in the phonological representation that exhaustively dominates all, and only the phonological exponents of the terminal nodes in . (Elfner 2012, p. 134)

As a result, a number of syntactic structures can be parsed into recursive phonological phrases: [fnc [NP]], for example, will be parsed as (fnc (NP)).

The inclusion of functional phrases in the mapping contraints at the interface does, however, not extend to function words. While Elfner acknowledges that some function words (and in particular pronouns) can acquire prosodic word status, she also assumes that only “lexical” words are, by default, mapped to prosodic words (Elfner 2012, pp. 243–44), which is in line with the proposals discussed above.

Tyler (2019) takes Elfner’s proposal on functional phrases two steps further and completely departs from the notion of differentiating between content words and function words at the interface. Instead, he assumes that all terminal words are indiscriminately matched to prosodic words. This will be discussed in more detail below.

2.3. Function Words in p-structure

After the constraints governing the mapping at the interface have been discussed in the previous section, this section focusses on the principles and constraints that are concerned with the prosodic phrasing of function words at the level of p-structure itself. In her seminal paper on the prosodic structure of function words, Selkirk (1995) discusses four possibilities for function words to be phrased in prosodic structure, listed below for an abstract DP.

- 6.

- [ fnc [ lex ] ]

- a.

- as a prosodic word: ( ( fnc ) ( lex ) )

- b.

- as a free clitic: ( fnc ( lex ) )

- c.

- as an internal clitic: ( ( fnc lex ) )

- d.

- as an affixal clitic: ( ( fnc ( lex ) ) )

Depending on language-specific phonological and morphosyntactic constraints, weak function words can be represented by options (6b)–(6d). Based, for example, on phonological phenomena like aspiration, Selkirk concludes that function words which precede ‘lexical’ words (as in a DP) are grouped as free clitics (option (6b)).

With respect to the differences between phonologically weak and strong function words, Selkirk identifies this as a challenge to any interface theory. In her approach, weak object pronouns in English are categorized as affixal clitics in a nested prosodic word structure. In contrast, strong forms, as they occur in isolation, under focus, and often in the phrase-final position, are analysed as prosodic words (i.e., option 6a), which by definition violates the interface restriction that prosodic words can only be mapped onto lexical elements.

The prosodic integration of function words with preceding or following prosodic material has been further scrutinized in a number of research articles. Kabak and Schiering (2006), for example, discuss function word forms in different German dialects and how two utterance-initial function words preceding a content word should be grouped prosodically. Their data includes commonly fused forms like wenn es kommt > wenn’s kommt (‘if it comes’) and cases of consonant intrusion, for example n-insertion in High Alemannic (citing Ortmann 1998) and ʀ-insertion in Middle Frankish. Interestingly, the constraints found for ʀ-insertion are identical with the ones found for n-insertion in Swabian which will be discussed in more detail in Section 4. In both cases, the intrusive consonant cannot occur between two content words (see Kabak and Schiering 2006 for more details), or between a function word and a following content word ([ɪ] and [aphʊL] in 7b), but it can optionally appear between two function words ([vou] and [ɪ] in 7a).

| 7. | a. | dɪ fraʊ vou -ʀ- ɪ aphʊL | |

| the woman who -ʀ- I pick.up | |||

| ‘The woman who I pick up.’ | |||

| b. | *dɪ fraʊ vou ɪ -ʀ- aphʊL | (Kabak and Schiering 2006, pp. 70–71) |

Kabak and Schiering note (but dismiss) the most obvious analysis of the data, where prosodic word status would be assigned to the first function word ([vou]) in order to explain the encliticization of the second function word. Both would then be grouped in a nested prosodic word (8).

- 8.

- (((ˈfnc) fnc) (lex) )

This analysis would also be supported by the fact that there is a stress on the first of the two function words, but Kabak and Schiering (2006) reject this phrasing possibility. According to their analysis, even the strong function words do not receive prosodic word status as some of them have, for example, only lax vowels. However, it is not quite clear why this constraint does not extend to monosyllabic content words with lax vowels which are nevertheless analysed as prosodic words (e.g., German Bett ‘bed’: [bɛt]) or how this explains the function words which have weak and strong forms, or even only strong forms (e.g., German weil ‘because’).

Their other argument against assuming prosodic word status for at least some function words is rather one of theory: based on the Principle of Categorical Invisibility of Function Words (Selkirk 1984, see above), and on the impossibility of a principled categorical distinction between function words that can form prosodic words and those which cannot, they oppose the nested prosodic word analysis. Instead, Kabak and Schiering propose that the function words form a foot which is adjoined to the following prosodic word within the phonological phrase and which provides a domain for phenomena like ʀ-intrusion in Middle Frankish.

- 9.

- ( (fnc-(ʀ)-fnc) (lex) )

This proposal is rejected by Ito and Mester (2009, p. 33) who propose that function words in structures like (7) should be integrated into nested prosodic words (10), and not into phonological phrases.

- 10.

- ((fnc-(ʀ)-fnc) (lex))

Although Ito and Mester discuss contracted function words like oughta and hafta which point towards encliticization of the second (to) to the first (have/ought) function word (which would receive prosodic word status), and furthermore list a number of function words which appear to be prosodically fully formed (e.g., English: until, underneath; German: anstatt ‘instead’, angesichts ‘in view of’), they nevertheless assume that function word categories are invisible at the interface and only content words are mapped to prosodic words (lex-to-(l/r)). In the following example, ne Maschine ‘a machine’ (where ne is a reduced form of eine) is phrased into a nested prosodic word structure in (11) if the constraint lex-to-(l) applies, but is crucially parsed very differently without the constraint: In (12), the first syllable ma of Maschine is prosodically grouped into a foot with the previous article ne.

- 11.

- (ˌne. ( ma. (ˈʃi:.nə)))

- 12.

- ((ˌne.ma.) (ˈʃi:.nə)) (Ito and Mester 2009, ex 34)

Rhythmic groupings, as in example (12), have frequently been shown to apply to the organisation of prosodic structure (Bögel 2020b; Cutler 1996; Ghini 1993; Lahiri and Plank 2010; Prieto 2005; Wheeldon and Lahiri 1997) and point towards an understanding of p-structure which is less dependent on the constraints of the interface and more determined by principles and constraints that are in the domain of p-structure alone.

Such constraints are also the driving factor behind Tyler (2019)’s proposal. As briefly mentioned above, Tyler assumes that there is no fundamental difference between function words and content words at the interface, but that all words are matched to prosodic words. The approach is based on the observation that function words show very idiosyncratic behaviour with respect to the selection of their prosodic host (see previous discussion for examples).

In order to account for the idiosyncratic behavior of function words, Tyler assigns lexical subcategorization frames (Inkelas 1990) to reduced function words in order to account for their patterns of prosodic phrasing in p-structure. He adopts the proposal made by Ito and Mester (2009) and assumes that the function words are phrased into nested prosodic word structures, as specified by the subcategorization frames for clitics leaning to the left (e.g., object pronouns and the negation contraction n’t) and right-leaning clitics (e.g., prepositions and determiners).

| 13. | a. | subcategorization frame for an enclitic: [ [ ... ] fnc ] |

| b. | subcategorization frame for a proclitic: [ fnc [ ... ] ] |

These subcategorization frames are enforced by a high-ranking constraint and can, in some environments, cause substantial non-isomorphism between syntactic and prosodic phrase structure. All other terminal elements are subject to the standard Match-word constraint, including function words which do not have a subcategorization frame (i.e., which are full prosodic words).

By assigning subcategorization frames to individual function words, Tyler is able to sidestep the problem of the idiosyncratic behaviour with regard to prosodic attachment so commonly found with function words. His model can, to some extend, explain phenomena like “stranded” function words, that is, the question why enclitic and proclitic function words cannot occur in the initial or final position of a clause: their subcategorization frames cannot be fulfilled. With his discussion of right- and left-cliticisation he also provides crucial evidence that the prosodic behaviour of function words cannot be derived from syntactic structures.

There are two major issues with Tyler’s approach. Firstly, as all terminal nodes are matched to prosodic words, the reduced function words are the “marked” structure whose specific subcategorization frames override the general mapping algorithm. Given that reduced function words are the most frequent elements in a language, and that (as discussed in Section 2.1) the acoustic reduction of frequently used terms is due to the fact that a speaker does not identify the reduced item as “marked”, this assessment is hard to follow. Tyler addresses this issue by stating that the “non-uniformity of prosodic reduction” indicates that the full form is in fact the unmarked form (Tyler 2019, p. 18). It is, however, not surprising that there should be different types of reduction within the group given the variety of phonological (and syntactic) forms of function words.

Secondly, the subcategorization frames define what the environment of a specific function word looks like; the clitic status is only implied. This seems counterintuitive, as the lexical entry of an item should not define its environment, but the item’s inherent properties. It is then up to the different grammar modules (e.g., syntax or p-structure) to determine whether a specific element can occur in a particular position. For example, a nominative pronoun should not be able to occur in a position requiring a dative, and an enclitic should not be able to occur in the initial position of an intonational phrase. These constraints are not dictated by the item’s lexical entry, but are part of the respective modules’ principles and constraints.

Before discussing the Swabian data and an alternative approach to the analysis of function words in general, the following section briefly introduces relevant findings with a focus on pronouns only.

2.4. Pronouns as Function Words

As noted by Selkirk (1995), pronouns pose a challenge to the interface in that they often appear to have strong and weak forms. This challenge provides a starting ground for an analysis of function words that can explain and accomodate both weak and strong forms in a straightforward manner.

Pronouns are an interesting case with respect to information structure and prosody. In contrast to most other elements in a given clause, pronouns are per definition given material (Gundel et al. 1993), that is, it can be assumed that the denotation of a pronoun is already part of the common ground of the discourse (Krifka 2008). Given material (in Germanic languages) is often indicated by deaccentuation (e.g., Féry 2020), decreased prominence (e.g., Baumann 2006) and specific types of accentuation (e.g., Baumann and Grice 2006), all of which also correlate with the linear clause position of the given material (Féry and Kügler 2008). If a pronoun is in focus, an accent is crucially realised (Krifka 2008; Kügler 2018) and often correlates with the strong form.

However, an accent can also be realised in non-focussed contexts. Kügler (2018), for example, shows that syntactic positioning of German object pronouns before or after the infinite verb and the phonological size (i.e., whether the pronoun consists of one or two syllables) can influence the stressability of pronouns. Kügler found that bisyllabic pronouns are more likely to carry pitch accents and that this pitch accent is more prominent in comparison to monosyllabic pronouns. With regard to the syntactic positioning, pronouns preceding the infinite verb were more likely to carry full pitch accents in comparison to pronouns which were placed after the verb. These findings lead to Kügler arguing that German pronouns may be phrased as prosodic words. In this case, he suggests two possibilities for phrasing:

- 14.

- (... ((pronoun)) (verb) )The pronoun is phrased as the head of a recursive -phrase,

- 15.

- (... (pronoun) (verb) )The verb receives the main accent, and the pronoun, a less prominent/optional accent.

Zerbian and Böttcher (2019) extended the discussion on non-focussed stressed pronouns in spontaneous spoken German in a small pilot study with monolingual and bilingual speakers. They show that stressed pronouns can also be licensed by prosodic wellformedness constraints (such as headedness in intonational phrases) and by their syntactic function as complements in prepositional phrases “in which they count as lexical words in terms of phrasing” (Zerbian and Böttcher 2019, p. 2641). This implies that pronouns should be enabled by the interface constraints to be mapped as prosodic words in these positions.

Bennett et al. (2016) discuss pronouns (and their displacement) in Irish and use a slightly altered version of the Match-word constraint, which states that “prosodic words correspond to the heads from which phrases are projected in the syntax” (Bennett et al. 2016, p. 187). This implies that pronouns are matched to prosodic words, and since they (syntactically) form DPs, they should also be mapped to phonological phrases, as stated by Elfner (2012)’s version of Match-phrase. However, in their proposal they assume that Match-phrase is outranked by a binarity constraint which enforces a minimal weight on phonological phrases. As a consequence, pronouns are only matched to prosodic words at the interface and not to phonological phrases. As the main focus of their paper is on the operations performed in the phonological module, the altered Match-word constraint is unfortunately not further discussed in the context of a distinction between strong and weak forms on the one hand, and function words and content words on the other.

2.5. Research Questions and Predictions

Given the discussion of function words in general, and of pronouns in particular, this paper pursues two main questions:

- (a)

- Is a distinction between function words and content words justified during the mapping at the syntax–prosody interface? Are there alternatives that can account for the variation found especially in the group of function words (as discussed in the previous sections)?

- (b)

- How are function words phrased with the preceding and following material at p-structure? Are there any phonological or prosodic indicators which point towards a particular prosodic structure?

As discussed above, languages often feature two distinct pronoun forms: “strong” pronouns which tend to feature full vowels, longer duration, and can occur in a focussed position; and “weak” pronouns which have a reduced form and do not occur under focus. This difference in form can be assumed to correspond to a difference in prosodic structure: strong pronouns can be represented by prosodic words, while weak pronouns are realised as clitics, likely as enclitics given previous research (see, for example, the data presented in Kabak and Schiering 2006 (in addition to example (7a)), and the discussion in Lahiri and Plank 2010, especially Section 2.4.1.8).

Swabian also features two distinct 1SgNom pronoun forms, a strong form [i:] and a weak form [ə]. If this difference in form is indeed reflected in prosodic structure, then the strong form [i:] should be represented by a prosodic word and as such should be able to occur in the sentence-initial and sentence-final position (i.e., it is not depending on a preceding or following host). It should furthermore be the preferred form used to express focus. In contrast, the weak clitic form [ə] should not be able to appear in one of the edge positions of a clause (where it would lack a prosodic host) and should furthermore never be used to express focus.

Apart from this general distinction, the two forms should also differ with respect to the interaction with their prosodic environment. Of particular interest here are so-called function word clusters, where a subordinating complementizer is followed by a number of pronouns or other function words. The function words often contract or make room for phenomena like optional n-insertion (see also Kabak and Schiering 2006, for the similar ʀ-insertion]. Together with the pitch distribution in these clusters, these phonological processes facilitate insights into the prosodic phrasing mechanisms and thus provide valuable evidence for the mapping mechanisms between syntax and prosody, and the formation of the p-structure itself.

3. Material and Methods

The data presented in this paper is based on two sources: A corpus of spoken Swabian, which is part of a larger corpus containing a number of German dialects (Zwirner Corpus 2012) and a dialect translation of two Asterix comics (Uderzo and Goscinny 2017).

3.1. Asterix—Written Swabian

One part of the data consisted of written Swabian dialect versions of two Asterix comics (Uderzo and Goscinny 2017).7 The Asterix comics have been carefully translated into numerous languages and official dialect versions have been provided for almost all German major dialects. The Swabian version includes two phonological representations of the 1SgNom pronoun, i and e (=[ə]), and also shows cases of written n-insertion.

3.1.1. Method

Each sentence containing a pronoun was manually extracted and analysed in context. Two factors were taken into consideration:

- (a)

- Position: initial, medial, or final;where ‘initial’, ‘medial’ and ‘final’ refer to the linear positions of the pronouns in a sentence.

- (b)

- Information structure status: focussed8 or unfocussed;as determined by syntactic structure, focus particles, or context.

Apart from these factors, particular attention was paid to function word clusters and possible cases of n-insertion.

3.1.2. Asterix—Results

Concerning the initial position, the results were very clear: Only the strong form [i:] was used in the 152 sentences with an initial pronoun. This was independent of whether the initial element was in focus or not. The weak pronoun form [ə] was never used in the clause-initial position. In the medial position, the use of the forms is more variable: The weak form was used in 86 cases, the strong form in 59 cases. Both pronouns occurred in the final position. Table 1 summarizes the results.

Table 1.

Position of the pronoun form (Asterix).

There were six occasions where n-insertion was used (as exemplified in (16)).

- 16.

- I woes wia -n- ə dia Garnison ...I.1sg.nom know.1sg.prs how -n- I.1sg.nom that garrison ...‘I know how I (can convince) that garrison ....’(Uderzo and Goscinny 2017, p. 13)

Five of these n-insertions occurred following a complementizer (wo “where” and w “how”), and one was following the verb seh “see”. All of these insertions were thus found between a monosyllabic word with a final vowel/diphtong and the weak pronoun form [ə].

3.1.3. Asterix—Discussion

The linear distribution of these forms allows for insights into the respective prosodic representations. The clear exclusion of the weak pronoun from the clause-initial position supports the hypothesis that the weak pronoun is an enclitic and the strong form a full prosodic word. A possible alternative would be the claim that the strong form is a proclitic. However, this claim can be rejected, as both forms can be found at the end of clauses.

| 17. | a. | Dr wirkliche Häuptling ben i | |

| The real chief am I.1sg.nom | |||

| ‘I am the real chief!’ | (Uderzo and Goscinny 2017, p. 5) | ||

| b. | Glei platz ə | ||

| In.a.second explode I.1sg.nom | |||

| ‘I’ll explode in a second!’ | (Uderzo and Goscinny 2017, p. 16) |

Due to the predominant SVO/SOV structure in German, these occurrences are not numerous, but together with the findings with respect to the initial position, they allow for important conclusions. The fact that [i:] can occur in both initial and final position indicates that [i:] is not a (pro- or en)clitic, but receives prosodic word status. In contrast, the impossibility of [ə] to occur in the initial position (without a preceding host) points towards an enclitic nature.

The seemingly variable distribution in the medial positions can be explained with respect to focus. In a minority of the cases, the focus position is clearly indicated, either syntactically (as in 18) or by means of a focus particle (as in 19). In (18), the declarative V1-construction enforces prominence on the following pronoun.

- 18.

- Context: The faqir drank too much wine and has a hang-over as a consequenceHan i en Durscht!have.prs.1sg I.1sg.nom a.m.acc thirst‘I am (so) thirsty!’ (Uderzo and Goscinny 2017, p. 70)

In (19), the focussed constituent is indicated by the use of the focus particle ausgerechnet (‘of all things/people’).

- 19.

- Context: Obelix is being denied the magic potionWarom ausgrechnet i net?Why of.all.people I.1sg.nom not‘Why not me, of all people? ’ (Uderzo and Goscinny 2017, p. 27)

In both examples, (18) and (19), the use of a strong pronoun is obligatory; a weak form would render these sentences ungrammatical. But medial [i:] is not restricted to positions where focus is enforced by the use of particles or syntactic structure. It can also occur in positions where it can be exchanged with the unstressed form. However, as the data in (18) and (19) suggest, such an exchange would always result in a different prosodic structure and a slight change of meaning; that is, in these examples context determines the focus. Consider the following example, where the context is given in detail.

- 20

- Context: Impedimenta/Gutemine, the chief’s wife, and Mrs. Geriatrix/Methusalix are fighting over a carpet they found between their houses. When Impedimenta runs out of arguments as to why the carpet should belong to her, she yells:... ond außerdem ben i ’s Weib vom Chef!... and besides be.1sg.prs I.1sg.nom =the.n.nom wife of.the chief‘And besides, I am the chief’s wife!’(Uderzo and Goscinny 2017, p. 55)

By using the full form [i:], Impedimenta is contrasting her own (higher) social status to that of Mrs. Geriatrix in a kind of knock-out argument. Had she used the weak form [ə], the contrast would not have been openly expressed: Instead of stating that Impedimenta (in contrast to Mrs. Methusalix) is the wife of the chief and therefore her claims have priority, the use of the weak form would have simply stated her status (“Impedimenta is the chief’s wife”), but not the contrast to her opponent (as in “Impedimenta is the chief’s wife, and Mrs. Geriatrix is not”).

The replacement of a weak pronoun by a strong pronoun has a similar effect. In the following example, the insertion of a strong form would suggest a contrastive meaning that is not given by the context.

- 21.

- Context: During travelling, the faqir is wondering whether they are still on the right way, so he tells his companions that he will ask... ob =ə no uf am rechta Weg be... if I.1sg.nom still on the.m.dat right way be.1sg.prs‘.... if I am still on the right way.’(Uderzo and Goscinny 2017, p. 61)

Using a prominent [i:] in this structure would suggest that there are other people travelling who have already lost their way. Using the weak form does not imply this contrastive context and is thus the right form for this particular structure.

In order to gain more insight into the prosodic patterns found with respect to the pronouns in focussed and non-focussed positions and in particular, with respect to cases of function word clusters and n-insertion as in (16), these initial findings in written Swabian were complemented with an analysis of spoken Swabian.

3.2. The Zwirner Corpus—Spoken Swabian

The Zwirner corpus is a collection of interviews which documents dialectal variation in Germany in the 1950s and 1960s. The Swabian part of the corpus roughly comprises of 34 speakers; for the data presented in this paper, a random sample of 12 speakers was chosen.9 The speakers were between 31 and 75 years old and speak about daily life (in the present and the past) in their villages.10 The interviewer is the same in all interviews and a native speaker of Swabian. He only engages with the interviewed person if the speaker stops speaking, prompting them to comment on a particular topic.

3.2.1. Method

The overall duration of the spoken data used in this paper was 4 hours and 6 minutes. As the data is not annotated, the author listened to all recordings and manually extracted all sentences which contained at least one 1SgNom pronoun. In a second step, the annotation software Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2013) was used for the prosodic analysis. Based on perception and an analysis of the vowel’s spectrogram representation (in particular F2), all occurrences of the pronoun were sorted in one of three categories: [i:], [ə], or ‘undecided’ (the latter was used for the few cases where an exact distinction between [i:] and [ə] could not be made).

In a second step, the prosodic pattern associated with each pronoun was analysed. Since this is not strictly controlled experimental data, a lot of variation and non-standard constructions can be found. As a consequence, the pitch analysis had to be done case by case. Each case was analysed according to whether the pronoun took a prominent position (in form of a pitch accent, a rise in pitch, or in the cases where it remained at the same level as a previous pitch accent) or a non-prominent position (a fall in pitch, a low-level pitch that is not a pitch accent). These are very coarse-grained categories, but are in line with previous findings that Swabian has mostly rising accents (Kügler 2007). For this extremely variant data, these two categories were suitable and allowed for many insights.

3.2.2. Zwirner Corpus—Results

There were a total of 302 pronouns found in the corpus. Thirteen of these are pronouns which had been dropped by the speaker.11 Six pronoun occurrences had to be discarded, because they could not be clearly labelled as [i:] or [ə]. In the remaining 283 cases, 156 were classified as [i:] and 127 as [ə]. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Position of the pronoun form in the clause (Zwirner corpus).

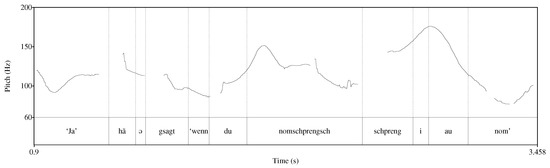

A majority of the [i:] pronouns were found in an initial position, or in a prominent medial position; one occurred in the final position. The weak form [ə] occurred in medial, mostly non-prominent positions. One weak form was found in a final position. The following example and the corresponding Figure 1 illustrate the use of a medial (falling) weak form and a prominent (rising) strong form.

Figure 1.

Pitch contour and TextGrid annotation for example (22).

- 22.

- Context: The speaker tells the story of how he and a school friend had a competition as to who would dare to jump over a box.ja hã ə gsagt wenn du nom-schprengsch schpreng i au nomyes have I.1sg.nom say.ptcp if you over-jump jump I.1sg.nom also over‘ “Yes”, I said, “if you jump over (that), I’ll jump over (that), too!” ’(Zwirner Corpus 2012, Sp 175, 667 s)12

There were also a few cases, where each pronoun form occurred with a seemingly opposing pitch pattern: 17 cases with [i:] did not receive any prominence, and four cases of [ə] featured a (small) rise.

A total of six cases of n-insertion were found. Three cases followed the complementizer wo ‘where’, and three insertions occurred after auxiliary verbs hã “have” and kã “can”.13 In contrast to the examples found in the Asterix comics, where n-insertion occurred only with [ə], it was found with both pronoun forms in the spoken data: three with [i:] and three with [ə].

3.2.3. Zwirner Corpus—Discussion

The results given in Table 2 largely confirm the hypotheses and the findings in Section 2: In a majority of the cases, [i:] occurs in an initial or a prominent position. However, there are 17 occasions, where the non-prominent realisation seemingly opposes the expected pitch pattern. When looking at these cases in more detail, the interplay between context and focus again seems to play an important role. Consider example (23), of which two more variations with this pattern can be found in the corpus.

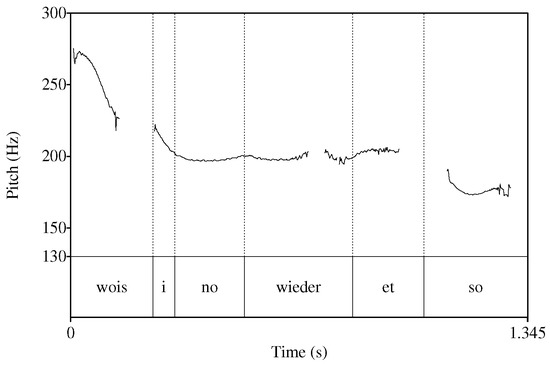

- 23.

- (des) wois i nõ wieder net so(this) know.1sg.prs I.1sg.nom now in.turn neg so‘This, in turn, I don’t know so much about.’ (Zwirner Corpus 2012, Sp 96, 293 s)

As Figure 2 shows, the pronoun is part of a fall following the contrastively stressed (Des) wois ‘(This) know’.14

Figure 2.

Pitch contour and TextGrid for example (23).

Although this is not reflected in the pitch pattern, [i:] is in focus here as well. The speaker had just described how they used to sell cherries on the market and in the neighboring villages, when the interviewer asked whether they also used the cherries to distill alcohol. The answer the speaker gives in (23) signals that she does not know anything about that topic—in contrast to her knowledge on the selling of cherries. At the same time, she signals that others might know more about this.

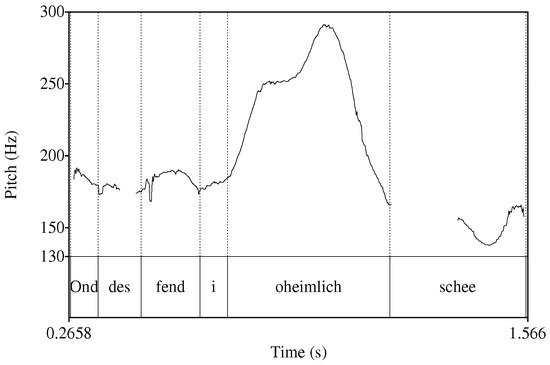

Another example of [i:] in a medial unaccented position is shown in (24) and Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Pitch contour and TextGrid, for example (24).

- 24.

- ond des fend i oheimlich scheeand this find.1sg.prs I.1sg.nom incredibly nice‘And I find this incredibly nice.’ (Zwirner Corpus 2012, Sp 174, 223 s)

In this case, the speaker laments that the girls of today’s generation no longer bond as closely as the girls did in the speaker’s generation. The companionship of the same-age girls in the villages was a central aspect of their life, also with respect to traditions. These relationships are still important today, and this is when the speaker utters the sentence in (24), emphasizing the emotions associated with these friendships. The use of [i:] here indicates that she values these bonds and traditions, but that she is also well-aware that this is no longer a desirable tradition for the current young generation (her daughter and her friends); again, [i:] expresses a contrast.

All of the examples where [i:] was found in a non-prominent position allow for a contrastive interpretation in context, but do not express the contrast in terms of pitch accents in the vicinity of another element bearing a contrastive or emphasising pitch accent as is the case in examples (23) and (24). However, a number of research works showed that while the elements bearing “secondary focus/second occurrence focus” usually do not realise a pitch accent (but see Féry and Ishihara 2009), prosodic prominence is nevertheless signaled by means of, for example, duration or intensity (see, for example, Baumann et al. 2010; Beaver et al. 2007; Féry and Ishihara 2009; Baumann 2016 for an overview).15

With respect to the distribution of prosodic prominence in a clause, Beaver and Velleman (2011) argue for a two-factor approach to explain primary and secondary prominence: (1) unpredictability of the element and (2) focus. They assume that these factors determine the placement of the most prominent pitch accent in a clause, and that elements which comprise only one of these factors are less prominent if they are in competition (i.e., they receive secondary focus). Contrastively pronounced elements are usually the most important elements in the speaker’s communication goals and are commonly the least predictable. As a consequence, the contrastive element usually receives the most distinct prosodic prominence. This idea of competition for prominence based on focus and predictability fits in well with the discussion on frequency/predictability and on givenness in Section 2.1. It is thus of no surprise that a pronoun, which in itself is given and highly predictable in the context and furthermore is able to express a certain amount of (contrastive) focus by the mere use of a specific vowel ([i:]), will not receive any prominence if it is placed in the direct vicinity of a prominently focussed element.

The other group of unexpected occurrences were four cases of [ə] which showed a rise; none of them were in a position or a context that required (contrastive) focus. In all four cases, the pronoun was preceded by an (auxiliary) verb which received a low pitch accent. It can thus be assumed that these occurrences are either a realisation of a L*+H pattern or that the pronoun happened to be in the position where a reset to the (higher) pitch level takes place or where rhythmic constraints enforce a small rise on the pronoun.

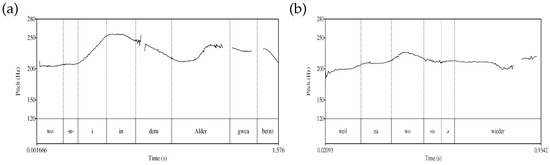

Concerning the function word clusters and n-insertions, the pitch excursion differs depending on the pronoun form. The following two typical examples both contain a subordinate clause starting with wo16, followed by n-insertion and one form of the pronoun each.

| 25. | a. | wo -n-i in dem Alder gwea ben | |

| when -n- I.1sg.nom at that age be.ptcp be.1sg.prs | |||

| ‘When I was at that age ...’ | |||

| (Zwirner Corpus 2012, Sp 96, 315 s) | |||

| b. | weil na wo -n- ə wieder | ||

| because then when -n- I.1sg.nom again | |||

| ‘Because when I again (had to work at home ...)’ | |||

| (Zwirner Corpus 2012, Sp 96, 857 s) |

While similar in their linear succession, the two figures differ in the pitch distribution on the wo-n-i/ə sequence. In Figure 4a, wo is deaccented; the main rise is on the pronoun [i:] (signalling a contrast) which allows for an analysis of the pronoun as a prosodic word. Figure 4b, in comparison, shows a rise on wo, which can be interpreted as receiving prosodic word status, and which is followed by a deaccented [ə]. Together with n-insertion, these (and similar) cases offer interesting insights into how function words are phrased at the p-structure.

Figure 4.

(a) Pitch contour for example (25a); (b) Pitch contour for example (25b).

4. The Prosodic Phrasing of Function Words: Evidence from n-Insertion

As briefly mentioned in the introduction (and parallel to Middle Frankish ʀ-insertion discussed in Section 2.3), optional n-insertion is restricted to the position between a prosodic word ending with a vowel and a following vowel-initial clitic. Crucially, this preceding word can be either a function word (e.g., the complementizer wo in example (26a)) or a content word (e.g., the finite verb seh in example (26b)). n-insertion cannot occur between two clitics (26c) or between two prosodic words (26d).

| 26. | a. | wo -n- =ə =ən17 seh |

| where -n- I.1sg.nom he.3sg.m.acc see.1sg.prs | ||

| ‘... where I see him.’ | ||

| b. | seh -n- =ə =ən | |

| see.1sg.prs -n- I.1sg.nom he.3sg.m.acc | ||

| ‘... I see him.’ | ||

| c. | *wo =ə -n- =ən seh | |

| where I.1sg.nom -n- he.3sg.m.acc see.1sg.prs | ||

| ‘... where I see him.’ | ||

| d. | *dass Kai -n- Ann sieht | |

| that Kai.3sg.f.nom -n- Ann.3sg.f.acc see.3sg.prs | ||

| ‘...that Kai sees Ann.’ |

As discussed above, the rise on wo in Figure 4b suggests that wo receives prosodic word status. The same can be assumed for the complementizer wo in (26a) and the finite verb seh “see” in example (26b). The fact that n-insertion can only occur between a prosodic word and an enclitic suggests that this particular structure is recursive and that enclitic pronominal function words are affixal clitics.18 Swabian n-insertion, then, is a segmental phenomenon which can only occur at the inner () singular boundary within a recursive prosodic word structure, as illustrated in Figure 5. These findings are in line with Selkirk (1995) (for weak English object pronouns) and Ito and Mester (2009) (for the data discussed in (10)) who come to a similar conclusion with regard to the host–clitic relationship in these structures.

Figure 5.

Recursive prosodic word structure as indicated by n-insertion.

Additional evidence for this interpretation comes from resyllabification patterns. If the preceding word ends in a consonant, then this consonant is resyllabified into the onset of the following enclitic [ə], independently of speech tempo. As resyllabification (especially in slow speech tempo) is considered to occur in the domain of the prosodic word (Kleinhenz 1998), the conclusion is that the host and clitic form a recursive prosodic word structure, and not, for example, a structure where the prosodic word and the following clitic are placed within a phonological phrase (as it would be the case with free clitics).

While this analysis fits well with the data and the findings in previous research, n-insertion did not only occur with the weak form [ə]; there were also three cases where -n- was followed by the strong pronoun [i:] (as in example (25a)). These structures seemingly oppose the claim made about n-insertion: If both wo and [i:] are prosodic words, and if -n- cannot occur between two prosodic words (see (26d)), these structures should, strictly speaking, be impossible.

However, when looking at the pitch excursion of Figure 4a which represents just such a structure, it becomes clear that the pitch distribution is very different from the one just discussed with respect to the weak pronoun [ə] (Figure 4b). In Figure 4a, [i:] receives a very prominent pitch accent; the complementizer wo is deaccented. This allows for the creation of a mirror image of the analysis above in Figure 5: In Figure 4a, [i:] forms a full prosodic word to which wo procliticizes. Under this assumption, inserted -n- occurs exactly in the position predicted by the analysis above (see also Figure 6): within the non-minimal prosodic word, and at the edge of a minimal prosodic word [+minimal, -maximal].19

Figure 6.

Recursive prosodic word structure with strong pronoun [i:].

After having established the prosodic shape of each form and the prosodic structures in which they occur, one question remains to be answered: is there a prosodic unit above the prosodic word in these structures? So far, no detailed account for the identification of phonological phrases exists for Swabian (but see Kügler 2007 for a more general account of Swabian intonation). However, the pitch contour in Figure 4a suggests that the function word cluster forms an independent phonological phrase (possibly including two more function words, in and dem), while in Figure 4b, the cluster wo-n-ə is more likely to be grouped with a following phonological phrase.

From an interface perspective, this supports the assumption put forward by Elfner (2012) that functional phrases project phonological phrases as well. Whether such a phonological phrase is then realised as part of p-structure is a completely different matter, briefly touched upon in the following section.

5. Function Words at the Interface

The results of the two corpus studies in Section 3 confirm the hypothesis that there is indeed a difference in the prosodic representation of strong and weak pronouns in Swabian. The strong form [i:] is represented by a prosodic word and can appear at both edges of a sentence or in a focussed position. The weak form [ə] is an enclitic which is dependent on a previous host and consequently can never occur in the initial sentence position, and cannot be found in a focussed position. These findings and other studies (Section 2) support the hypotheses that the prosodic distinction between function words and content words at the interface between syntax and prosody cannot be based on a syntactic category alone, that function words themselves do not form a homogenous group with respect to prosodic phrasing, and that a single morphosyntactic item can be prosodically represented by a weak form and a strong form.

Section 4 showed that prosodic phrasing at the level of p-structure is also determined by the respective prosodic representations of a function word. As the discussion of n-insertion shows, both forms of the 1SgNom pronoun can be part of a recursive prosodic structure. However, while the weak form takes the position of an affixal enclitic in , the strong form occupies the -position where it can, in principle, be a prosodic host for other clitics.

These diverse aspects with regard to the prosodic form and the prosodic phrasing of function words cannot be accounted for by the current matching constraints at the level of the word. Based on syntactic category and/or structure alone, neither the two forms of the 1SgNom pronoun, nor their role in the formation of a recursive prosodic word structure can be predicted. Instead, for a linear sequence like wo ə ən (‘where I him ...’, see (26a)) and its alternative wo i ən, the Match-word constraint would not project anything, as all elements (syntactically) are function words. In addition, the recursive prosodic words established in Figure 5 and Figure 6 cannot be predicted based on the syntactic structure of this sequence. Even when taking wellformedness constraints into account, these structures (and their differences) cannot be derived without the essential information on the prosodic form of the function word. Together with other frequently found mismatches at the level of the prosodic word and below (see Section 2), this suggests that the categorical differentiation between function words and content words at the interface between syntax and prosody cannot be upheld.

Coming to the same conclusion, Tyler (2019) instead assumed that every morphosyntactic word should be matched to a prosodic word, irrespective of the word category. In order to account for the variations found in function words, he proposes prosodic “subcategorization” frames which can overwrite the Match-word constraints. As discussed in Section 2.3, this approach is problematic from a theoretical perspective, as this would (a) mark the most frequent words of a language as the ‘marked’ construction, and (b) would put the focus on the element’s prosodic environment and not on the prosodic nature of the word itself (which is then further constrained by its environment). From an empirical perspective, this is problematic. Consider example (27), repeated from (13a).

- 27.

- subcategorization frame for an enclitic: [ [ ... ] fnc ]

Firstly, if all pronouns are matched to prosodic words by default, this constraint will never be applied. As discussed above, the recursive prosodic structure is a result of the clitic nature of the pronoun: It is a product of wellformedness constraints which accomodate an existing clitic. The structure cannot be predicted as a possible candidate for p-structure by syntactic structure and/or Match-constraints at the interface. However, if the pronoun’s clitic form is selected based on the satisfaction of the subcategorization frame, we find ourselves in a circular discussion: The recursive structure cannot be assumed unless a clitic is present, but the clitic can only be selected over the default (!) strong form if there is a recursive prosodic word structure.

Secondly, the subcategorization frames needed to express the possible environments would have to be much more complex in order to account for the prosody of function word clusters. In a function word cluster, the 1SgNom pronoun can occur in first, but also in second position in a recursive prosodic word (e.g., after an auxiliary: ((Ihm) =han =ə=’s) gsagt (Him-have-I-it-told ‘I told him that’)). More possibilities exist with other pronouns, for example, the third-person dative masculine clitic, əm “him”, which can occur in (at least) three positions within a function word cluster.

| 28. | a. | I ((helf) =əm)! | (I-help-him, ‘I am going to help him!’) |

| b. | ((I) =han =əm) gholfa! | (I-have-him-helped, ‘I (alone) helped him!’) | |

| c. | ((I) =han =’s =əm) gsagt! | (I-have-it-him-told, ‘I (alone) told him that!’) |

In addition to these variations, there are also interactions with enclitics like ’s “it”, which are drawn into the coda of the previous item. These should probably be treated as (a variant of) internal clitics (see 6), which would in turn also have to be accounted for by the subcategorization frame.

These brief examples already show that, instead of defining all possible environments, it would be much more effective to simply state the prosodic status of a word, and then constrain its appearance by means of principles native to p-structure alone.

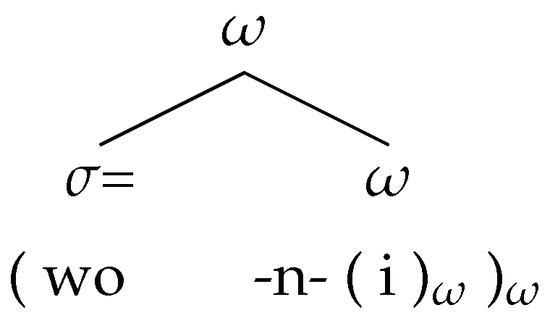

5.1. A Two-Tier Approach to the Interface

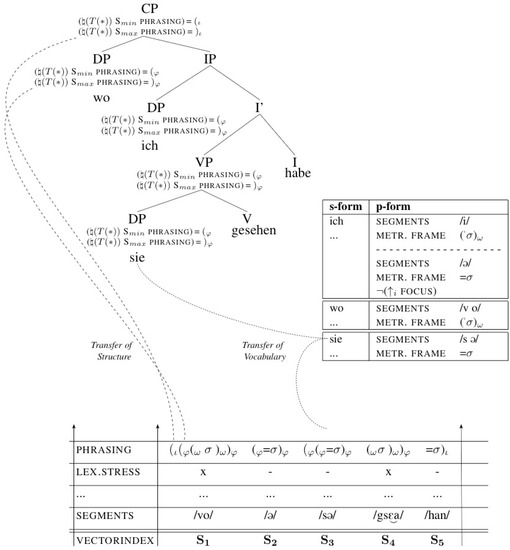

The approach presented here proposes exactly that: Instead of basing the Match-word constraint on the word category/terminal nodes alone, the constraint is removed from the interface between syntax and prosody and is applied at the level of the word and its (mental) lexical representations. The Match-word is thus separated from the constraints matching larger constituents (Match-clause and Match-phrase) and instead associates syntax and prosody on a separate tier with reference to the lexicon. The result is a two-tier mapping approach to the interface, illustrated in Figure 7: The transfer of structure maps information on syntactic and prosodic constituency at the higher levels, and the transfer of vocabulary matches phonological and morphosyntactic information at the level of (morphosyntactic/prosodic) words via the lexicon.

Figure 7.

A two-tier approach to the interface: the transfer of structure and the transfer of vocabulary.

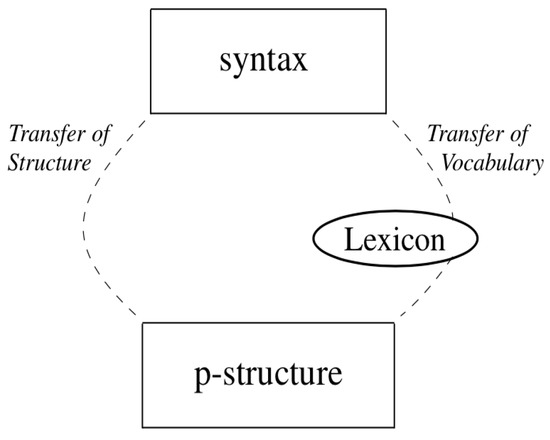

The transfer of structure is used as a collective term for Match-phrase and Match-clause, with no differentiation between functional and “lexical” phrases (cf. Elfner 2012). The transfer of vocabulary, however, is not based on syntactic word categories alone, but allows for a more fine-grained analysis by accessing the so-called “multidimensional” lexicon (see also Figure 8). Following ideas put forward by Levelt et al. (1999), each lexical element20 has several lexical dimensions, two of which are the s(yntactic)-form and the p(honological)-form. The s-form represents the morphosyntactic feature bundle which includes information on word category, person, number, gender, and so forth. The p-form contains information relevant for the phonological (and prosodic) representation, for example, the segments,21 information on lexical stress, the number of syllables, the foot structure, and the prosodic status. While the information stored with the s-form feeds into syntax, p-form information is relevant for p-structure, which supports a modular view of grammar. Figure 8 illustrates the lexical entries for the 1SgNom pronoun and the noun Schwäbin “female Swabian” (for comparison).

Figure 8.

The multidimensional lexicon.

Both s-forms are transcribed as the Standard German form ich “I” and Schwäbin “Swabian” to express the fact that the syntactic information is not a “form”, but a bundle of morphosyntactic features. The related p-forms contain information relevant for p-structure. Schwäbin, for example, consists of two syllables (with lexical stress on the first syllable) which form a trochaic foot22 and a prosodic word.

For the pronoun, however, there are two options: It can either be realised as a full prosodic word, or as an enclitic (=), where = preceding the syllable indicates that this particular form is dependent on a preceding prosodic host.23 This is similar to what Tyler (2019) proposed with respect to subcategorization frames, except that here, the lexical entry does not define what the prosodic structure surrounding the lexical item should be, but what the prosodic structure of the element itself is. Indicating that the element is a clitic makes it very flexible with respect to phrasing in comparison to a (much more constraining) subcategorization frame.

The weak pronoun form further includes a constraint that excludes it from any position in focus: ¬( focus). This LFG constraint24 prevents the p-form [ə] from being selected if there is a focus attribute present in the i-structure associated with this word.

This basic p-structure related information is part of every lexical entry. During the transfer of vocabulary, each s-form is associated with its related p-form (and vice versa), which leads to an alternative formalisation of the Match-word/ constraint:

| 29. | a. | Match-word: | Match every syntactic form with its phonological form |

| b. | Match-: | Match every phonological form with its syntactic form |

At the interface, the transfer of vocabulary (Match-word) matches the morphosyntactic (feature bundle) information with the related p-forms and makes this information available to the p-structure. In addition, information on larger constituents is made available to p-structure through the transfer of structure (Match-phrase/Match-clause).25 Taken together, both transfer processes provide the initial input to the p-structure.

Take the following example which contains n-insertion and the weak enclitics [ə] and [sə] “her”.

- 30.

- ... wo -n- ə sə gsea han... where -n- I.1sg.nom she.3sg.f.acc see.prtcp have.1sg.prs‘... where I have seen her. ’ Standard German: wo ich sie gesehen habe

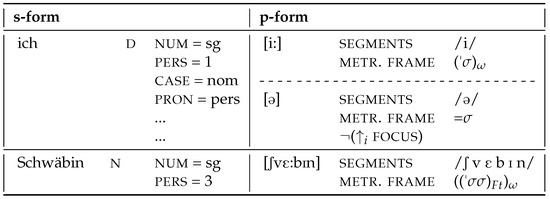

Figure 9 illustrates the two-tier approach to the interface for (30). It shows a “strict” matching approach, in that every DP and VP is matched to a -phrase. While the Match-clause/ constraint is illustrated with the CP, it was deleted for the IP in order to simplify the representation.26 The use of Standard German in the syntactic tree indicates the fact that these are really abstract representations of morphosyntactic feature bundles.

Figure 9.

A two-tier approach to the interface, for example, (30).

In this approach, p-structure is represented by the p-diagram (at the bottom of Figure 9), a compact two-dimensional representation of phonological information. The p-diagram is organised linearly into syllables. Each syllable receives a vector (S–S) which vertically encodes information/attributes associated with this syllable, e.g., (prosodic) phrasing or lexical stress.27

The transfer of vocabulary matches each s-form with its related p-form. The p-form information is encoded in the p-diagram: /vo/, for example, is a prosodic word and has lexical stress; /sə/ and /ə/ are enclitics and are not stressed. In addition, the transfer of structure associates the material contained in a particular syntactic phrase or a clause with the appropriate prosodic domain, here either a phonological phrase (Match-phrase) or an intonational phrase (Match-clause). The formal annotations in the syntactic tree can be read as follows (♮ is the projection function between syntax and p-structure): For each terminal node T under the current node (* = XP), take the minimal (min) vector (the syllable/S) and for the attribute phrasing insert a left -/-boundary; for the vector with the maximal (max) index under that node, insert a right -/-boundary. This ensures that the larger prosodic boundaries are matched with the exact edges of each syntactic constituent: wo /vo/, for example, is the first element of the clause and therefore the S for the CP and the uppermost DP. Consequently, it receives a left - and a left -boundary under its phrasing-attribute – in addition to the p-form material provided by the transfer of vocabulary. As it is also the S syllable in this DP, it furthermore receives a right -boundary (which results in a very small -phrase).

5.2. The Prosodic Phrasing of Function Words: p-Structure

Taken together, both transfer processes provide the initial input to p-structure as illustrated in Figure 9. Assuming strict modularity (Fodor 1983), the surface prosodic structure is also based on a set of principles and (wellformedness) constraints inherent to p-structure alone. This includes, among many others, rhythmic constraints, prosodic weight, type, and size constraints (e.g., binarity constraints, EqualSisters (Myrberg 2013)), changes in linear order (e.g., based on prosodic inversion (Halpern 1995) or the StrongStart constraint (Selkirk 2011)), and the application of phonological phenomena like resyllabification, deletion, or insertion. As a consequence, the final shape of prosodic structure can be very different from the original input provided by the matching constraints at the interface. For example (30), the input to p-structure based on Match constraints is shown in (31a). In contrast, the prosodic surface structure according to the analysis in this paper should resemble (31b) (whereby the placement of the -phrases and the phrasing suggested for the verbal complex need to be confirmed in further research):

Based on the findings discussed in this paper, it can be assumed that the following constraints (with the neutral names C1–C3, see Table 3 for an overview) apply within p-structure (constraints here are expressed as regular relations closed under composition (finite state transducers)).28

| 31. | a. | Interface: | ((( wo)) (=ə) ((=sə) ( gs‿ea)) =han) |

| b. | P-structure: | ((( wo) -n- =ə =sə)) ((( gs‿ea) =han))) |

Table 3.

Analysis of example (30) in the form of regular relations closed under composition.

- 32.

- C1: Following the strict layer hypothesis (a.o. Nespor and Vogel 1986; Selkirk 1995), -phrases cannot consist solely of a prosodically dependent clitic.

As a result of constraint C1, all -structures that only contain unstressed material in form of a clitic can be deleted: (=)→ =.

- 33.

- C2: Enclitics form a recursive prosodic word structure with the preceding prosodic word.

Constraint C2 enforces the creation of a recursive prosodic word structure for one or more enclitics. () =+ → (() =+).

This constraint would furthermore have to include references to possible intervening occurrences of -phrase boundaries, but since these do not seem to have an effect on the phrasing of enclitics in Swabian, they are excluded from the present discussion. Other languages, however, might be more sensitive to these boundaries and apply constraints like, for example, clitic repositioning (Bennett et al. 2016; Halpern 1995, a.o.).

- 34.

- C3: Optionally insert -n- between two vowels at a minimal, non-maximal prosodic word boundary.

This ensures that n-insertion can only occur at the position discussed above in Section 4. ((?*V) =(V?*))→ ((?*V) (-n-) =(V?*)) where ?* refers to “any other segments or none” and brackets (-n-) indicate optionality (not to be confused with prosodic bracketing here).

The formal relation between the prosodic input to p-structure and the prosodic surface representation (the output) can then be expressed in terms of composition:

- 35.

- Input ∘ C1 ∘ C2 ∘ C3 ⇒ Output

The following table gives a more detailed overview of the analysis.

The final structure in Table 3 is one possible analysis for this particular sentence and also allows for n-insertion to be placed in the predicted position. Another reasonable possibility would be to group the whole sentence into one phonological phrase, for example, based on a constraint that requires for phonological phrases to consist of two prosodic words (e.g., in form of a BinMin constraint). Although initial findings point into that direction (in particular the difference between Figure 4a,b), the data from the corpus is too scarce and has too much variation for this question to be answered in a satisfying manner.

Even though the initial default mapping of syntactic phrases to phonological phrases in Figure 9 seems excessive at first, it is nevertheless crucial to have this information available. If example (30) had contained a contrastively focussed pronoun instead, the analysis would have been very different. Example (36) compares the initial structure after Match constraints have applied with the prosodic surface structure after the application of p-structure-internal principles and constraints.

| 36. | input: | wo= ) ( ( i ) ) (( =sə ) ( gsea ) ) =han ) |

| : | wo= ( ( i ) ) ( =sə ( gsea ) =han ) | |

| : | ( ( wo= ( i ) =sə ) ) ( ( ( gsea ) ) =han ) ) ) | |

| : | ( wo= -n- ( i ) =sə) ( ( gsea ) =han ) ) ) |

Whether this prediction is correct for all parts cannot be fully answered at this point. What is, however, likely, is that the contrastively focussed pronoun forms a separate phonological phrase, as shown in Figure 4a. The potential for such a phrase has to be there from the beginning, which is ensured by a version of Match-phrase which does not differentiate between functional and “lexical” categories, but leaves the decision as to whether a potential -phrase is realised to p-structure itself. In addition, the new Match-word constraint with its much more fine-grained information allows for the focussed pronoun to be classified as a prosodic word, thus preventing the application of a constraint like C1 and allowing for the preservation of the pronoun’s associated -phrase. Based on the detailed information from the interface, the p-structure constraints can thus reliably create (or select) the prosodic surface structure as it was established in this paper.

6. Conclusions

Function words have long been a challenge for the mapping algorithms at the interface between syntax and prosody. On the one hand, most approaches (including the current Match constraints, Selkirk 2011) assume that function words are not mapped to prosodic words. On the other hand, however, numerous research works (Section 2) showed that function words can form prosodic words. This is especially true for less frequent function words or multisyllabic function words, but has also been established for function words which differentiate between a strong form and a weak form. In addition, the prosodic phrasing of function words at the level of p-structure often cannot be predicted based on syntactic structure alone; indeed, function words are often responsible for considerable mismatches between syntactic and prosodic constituency.