Abstract

Processing research on Spanish gender agreement has focused on L2 learners’ and—to a lesser extent—heritage speakers’ sensitivity to gender agreement violations. This research has been mostly carried out in the written modality, which places heritage speakers at a disadvantage as they are more frequently exposed to Spanish auditorily. This study contributes to the understanding of the differences between heritage and L2 grammars by examining the processing of gender agreement in the auditory modality and its impact on comprehension. Twenty Spanish heritage speakers and 20 intermediate L2 learners listened to stimuli containing two nouns with gender mismatches in the main clause, and an adjective in the relative clause that only agreed in gender with one of the nouns. We measured noun-adjective agreement accuracy through participants’ responses to an auditory task. Our results show that heritage speakers are more accurate than L2 learners in the auditory processing of gender agreement information for comprehension. Additionally, heritage speakers’ accuracy is modulated by their Spanish language proficiency and age of onset. Participants also exhibit higher accuracies in cases in which the adjective agrees with the first noun. We argue that this is an ambiguity resolution strategy influenced by the experimental task.

1. Introduction

Heritage speakers (HS) present a challenge for auditory processing research, due to the heterogeneity of this linguistic group. On the one hand, HS in the United States are broadly defined as individuals who grew up in a home where a non-English language was spoken, in this case Spanish, but exhibit different degrees of dominance in the majority language: English (Montrul et al. 2013). This experience with Spanish in early childhood aligns their acquisition context—to a certain extent—to that of monolingual speakers growing up in countries where Spanish is the majority language. Thus, this early exposure might grant HS certain advantages (Au et al. 2002; Montrul 2013), for example, in auditory processing as compared to learners of Spanish as a second language (L2). On the other hand, given that HS are not a homogenous linguistic group, they can display different levels of linguistic competence in production and comprehension abilities in the heritage language. In this sense, some of these speakers may align with adult L2 learners in their effectiveness processing Spanish (see Montrul et al. 2008). This highlights the importance of establishing comparisons between these two groups to better understand HS grammars and how these differ from the grammars of L2 learners, a question that carries important theoretical and practical significance.

One of the areas in which HS might have an advantage over L2 learners is in their ability to auditorily process the heritage language, given their early exposure to the phonology of this language. Auditory processing is a complex and dynamic process (Rost 2013) involving the parallel segmentation of the speech signal (bottom-up processing) and the application of context and prior knowledge (top-down processing), with listening comprehension as the ultimate goal. Vandergrift and Goh’s (2012) model explains that the comprehension process starts with the perception of speech from the sound signal through the acoustic-phonetic processor, while tapping into several knowledge sources in the parser (i.e., linguistic knowledge) and conceptualizer (i.e., discourse, pragmatic, and prior knowledge). Thus, to achieve the ultimate goal of this process, listeners must parse speech to comprehend the intended meaning. Following this model, HS with a certain level of proficiency in the heritage language might be able to automatize the processing of the incoming speech signal just like monolinguals1 do (Buck 2001). Furthermore, HS may even recognize words with less conscious attention (Vandergrift 2007) and process morpho-syntactic cues such as gender, which are acquired early during childhood (Hernández Pina 1984; Pérez-Pereira 1991; Socarrás 2011). In doing so, they will free up cognitive resources to focus on other aspects of aural processing, such as establishing syntactic relationships among features (e.g., gender agreement) to resolve discourse ambiguities. Their ability to process structures aurally may depend in part on their proficiency level in the heritage language and perhaps language dominance (see (Montrul et al. 2008) for a discussion of the impact of dominance in the written modality). In contrast, L2 learners find L2 listening comprehension one of the most difficult skills to master, conceivably due to their limited exposure to the L2 in the aural modality beyond the classroom setting (see (Bloomfield et al. 2010) for a review of variables that affect L2 listening comprehension). As a consequence, they might rely more on controlled processing of the incoming auditory signal (Segalowitz 2008). This is a mechanism to compensate for their underdeveloped abilities to perceive L2 speech, segment words, and derive a mental representation of their meaning. This lack of automaticity in auditory tasks leads to less efficient processing, which can result in an inability to process the incoming speech signal within the time limitations (Vandergrift 2007). The level of success in L2 aural processing is also modulated by level of proficiency, with more proficient L2 learners being more successful in the aural modality in general (Vandergrift 2007; Vandergrift and Goh 2012; Medina et al. 2020).

The present study examines HS and L2 learners’ auditory processing of gender agreement across relative clauses and its impact in overall sentence comprehension. Twenty HS and 20 intermediate L2 learners listened to Spanish stimuli with the structure ‘(the) NP1MASC of (the) NP2FEM that are ADJMASC’, which contained two plural nouns with gender mismatches in the main clause, and an adjective in the relative clause that only agreed in gender with one of the nouns. All stimuli were followed by a question in the auditory modality. We determined their accuracy identifying the correct noun-adjective agreement through their answers to the question in a force-choice task that contained images representing each of the nouns in the main clause.

This study makes three important contributions. First, it introduces a novel approach to previous research on gender agreement processing by examining how the parser handles incoming auditory information in the form of gender cues for the purpose of building meaningful syntactic structures (Jiang 2018). So far, gender agreement processing research has focused on investigating the use of gender cues to determine Spanish HS and L2 learners’ sensitivity to gender agreement violations (Dowens et al. 2010; Lew-Williams and Fernald 2010; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2011; Dussias et al. 2013; Montrul et al. 2008, 2013). To our knowledge, no research has examined the processing of gender cues for general sentence comprehension, which is operationalized in our study as the ability to establish the intended adjective-noun agreement relationship. Thus, the phenomenon of gender agreement across relative clauses offers an interesting avenue for processing research, as failure to auditorily process gender cues in the nouns and the adjective in sentences such as Mis amigos ven anuncios de películas que son divertidos ‘My friends watch the commercials of the movies that are fun’, renders the sentence ambiguous. As such, the adjective divertidos in the relative clause may modify either noun: anuncios or películas. Our study shows that HS are more accurate in the auditory processing of gender agreement information for general sentence comprehension than L2 learners, which allows us to better understand the differences between heritage and L2 grammars in terms of comprehension of the auditory input.

The second contribution of this study is that it investigates the factors, grammatical and otherwise, that may facilitate the auditory processing of gender agreement across relative clauses. Previous studies on gender agreement processing suggest that grammatical factors, such as noun canonicity, gender (Montrul et al. 2008, 2013) and the gender information encoded on the determiner (Lew-Williams and Fernald 2010; Dussias et al. 2013), have a facilitative effect in the processing of gender agreement. Additionally, other factors, such as language proficiency (Alarcón 2009; Dowens et al. 2010; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2011; among others) and age of onset (Montrul 2013), have also been found to play a role. However, most of these studies focus on L2 learner populations and not HS. By providing measures of all these factors among the HS population in this study, we show that proficiency and age of Spanish onset play an important role in HS’ auditory processing of gender agreement. This highlights the positive impact that an earlier exposure to auditory input in the heritage language has for processing.

The third and final contribution is that this study provides an explanation about how the auditory modality of the task may have an effect on participants’ gender agreement processing strategies. Our findings show that, overall, participants are most accurate processing gender agreement in cases in which the adjective agrees with the first noun instead of the second one. We propose that this strategy may be the result of participants’ failure to process gender agreement information auditorily. This prevents them from establishing the intended noun-adjective agreement in the sentence and, as a result, treat it as ambiguous. We will discuss how the use of this strategy for ambiguity resolution purposes may be influenced by the type of experimental task itself.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2 we present the theoretical background in terms of relative clause attachment and gender agreement in Spanish. Section 3 discusses previous studies on the processing of relative clause attachment in English and Spanish, as well as the processing of gender agreement in Spanish. Section 4 introduces our research questions, hypotheses, and predictions. Section 5 provides an explanation of the methods followed in the experiment design. In Section 6 we present our results and discuss their implications in Section 7. Section 8 discusses some of the limitations of the study and avenues for future research. Section 9 concludes this paper.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Relative Clause Attachment

Relative clauses are clausal modifiers that relate to one or more constituents in the sentence, typically noun phrases. Noun phrases are the antecedents or “heads” of the relative construction and are directly modified by the content of the relative clause. Take for instance a predicate adjective relative clause such as (1):

- (1)

- My friends watch the commercials of the movies that are fun.

In (1) the predicate adjective fun in the relative clause can modify both antecedents, the higher noun phrase the commercials and the lower noun phrase the movies. From a sentence processing point of view, the relative clause in (1) is ambiguous because both noun phrases are compatible with the content of the relative clause. However, several off-line and on-line studies have revealed that native speakers display distinct attachment preferences for these types of relative clauses depending on their language. For instance, in sentences like (1) native speakers of English prefer the interpretation where the relative clause modifies the closest noun phrase (Frazier 1987), i.e., the movies. This preference is referred to as low attachment as this noun phrase is further down the syntactic tree. Although low attachment was thought to be universal at one time, Cuetos and Mitchell (1988) observed that native speakers of Spanish prefer the interpretation where the relative clause modifies the farthest noun phrase, i.e., the commercials in (1). This preference is referred to as high attachment.

Since Cuetos and Mitchell’s (1988) seminal work on relative clause attachment preferences in Spanish and English, subsequent work has found more evidence for cross-linguistic differences in language processing. In general, languages have been found to be either high attachment, e.g., Spanish, Dutch (Brysbaert and Mitchell 1996), German (Hemforth et al. 2000), and French (Baccino et al. 2000); or low attachment, e.g., English, Romanian (Ehrlich 1999), and Basque (Gutierrez-Ziardegi et al. 2004).

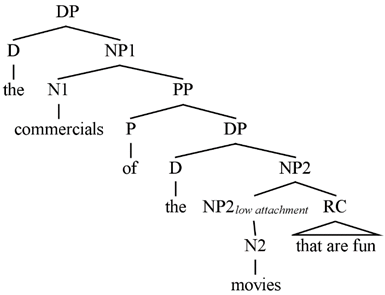

The preference for low or high attachment in languages has been argued to follow from two different parsing principles: Recency and Predicate Proximity (Gibson et al. 1996). The Recency principle, which favors low attachment in languages like English, reflects the parser’s effort to minimize the processing cost by attaching the relative clause to the closest noun phrase in the structure. Recency interacts with a second parsing principle called Predicate Proximity. Predicate Proximity, which is the active parsing strategy in languages like Spanish, favors attachment of the relative clause to the noun phrase that is closest to the head of the predicate phrase, i.e., the highest noun phrase. Gibson et al. (1996) argue that Predicate Proximity outranks Recency in high attachment languages, or in situations where the computational resources are short. These two parsing strategies are illustrated in the distinct syntactic structures in (2) and (3) and are based on the sample relative clause in (1).

- (2)

- Recency

- (3)

- Predicate Proximity

Attachment preferences in ambiguous relative clauses are not only influenced by structural factors, but other factors, grammatical and otherwise, have been found to play a role as well. These include the animacy of the nouns (e.g., stronger low attachment preference if both nouns match in animacy, see Desmet et al. 2002), type of preposition (e.g., of vs. with, see De Vincenzi and Job 1993; Felser et al. 2003a, 2003b), prosody (Schafer 1996; Fodor 1998), the frequency of exposure to each attachment pattern—the so-called Tuning Hypothesis (Cuetos et al. 1996; Mitchell and Cuetos 1991), and differences in working memory (e.g., stronger high attachment preference in participants with lower working memory, see (Mendelsohn and Pearlmutter 1999)2.

2.2. Spanish Gender Agreement across Relative Clauses

Spanish nouns are generally classified into two gender classes in the lexicon: masculine and feminine. Most prototypical nouns have canonical endings. Such endings are -o for masculine (e.g., libro ‘book’) and -a (e.g., silla ‘chair’) for feminine. However, other Spanish nouns end in the non-canonical form -e (e.g., peine ‘comb.MASC’, noche ‘night.FEM) or a consonant (e.g., sol ‘sun.MASC’, flor ‘flower.FEM’)3. Non-canonical nouns can be either masculine or feminine, but their gender information cannot be determined just by looking at their endings. One can only infer the gender of these nouns through their agreement with determiners and adjectives. Thus, grammatical gender is a lexical property of nouns. All nouns are arbitrarily assigned gender in the lexicon, which is represented by the formal feature [±f] (Carroll 1989; Carstens 2000). This feature is responsible for spelling out the gender of the noun. Feminine nouns such as mesa ‘table’ carry the feature [+f] and masculine nouns like cielo ‘sky’ carry the feature [-f].

Gender agreement, on the other hand, is a syntactic operation whereby a probe, i.e., the determiner or adjective, with an unvalued gender feature searches the syntactic structure looking for a goal with a valued gender feature with which to agree, i.e., the noun. Thus, the definite determiner el and the adjective oscuro ‘dark’ in (4) agree in gender with the masculine noun cielo ‘sky’. In (5), the definite determiner la and the adjective redonda ‘round’ agree in gender with the feminine noun mesa ‘table’.

- (4)

El cielo oscuro [-f] [-f] [-f] the.MASC sky.MASC dark.MASC ‘The dark sky’ - (5)

La mesa redonda [+f] [+f] [+f] the.FEM table.FEM round.FEM ‘The round table’

In terms of gender agreement processing, a structure such as (6) is not very problematic. Failure to process gender agreement between the adjective roja ‘red’ and the noun phrase la mesa ‘the table’ does not affect the general interpretation and understanding of this simple relative clause.

- (6)

- La mesa]FEM que era [roja]FEM‘The table that was red’

However, processing gender agreement in relative clauses with complex noun phrases as antecedents like (7a-b) is a more challenging task. In these cases, gender information provides valuable cues to help determine the antecedent that the relative clause is modifying. Thus, to process gender agreement in relative clauses such as (7a-b) one has to first process gender cues in determiners (in the case of non-canonical nouns), nouns and adjectives, and then identify the referent, i.e., the noun phrase, that agrees in gender with the adjective in the relative clause. Take for instance the unambiguous sentences in (7a-b). The sentence in (7a) forces gender agreement of the adjective with the higher masculine noun. On the other hand, the sentence in (7b) forces gender agreement of the adjective with the lower feminine noun.

- (7)

a. Mis amigos ven anuncios de películas que son divertidos. my friends watch commercials.MASC of movies.FEM that are fun.MASC b. Mis amigos ven anuncios de películas que son divertidas my friends watch commercials.MASC of movies.FEM that are fun.FEM ‘My friends watch (the) commercials of (the) movies that are fun’

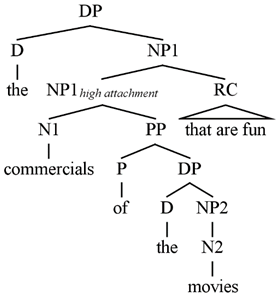

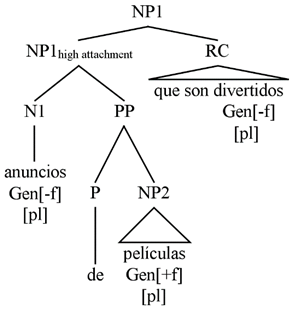

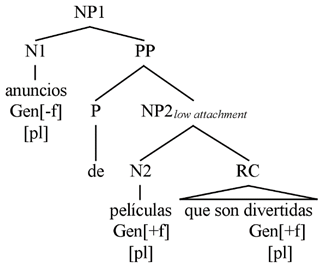

Recall that in Section 2.1, we discussed two different principles for sentence parsing: Recency and Predicate Proximity. If we apply these two principles to cases of forced agreement like the Spanish examples in (7a-b), we can predict that accurate processing of gender agreement between the adjective and the noun in (7a) will force listeners to apply the Predicate Proximity strategy (i.e., high attachment), whereas the agreement in (7b) will force the application of Recency (i.e., low attachment). These two parsing strategies are reflected in the syntactic structures in (8) and (9), respectively.

- (8)

- (9)

If we turn our attention to processing these structures in an auditory modality, the focus of the present study, there are several factors that can affect the processing of gender agreement cues in (7a-b). As we will discuss in more detail in Section 3, it could very well be that listeners fail to process gender agreement cues due to a higher demand in the computational resources triggered by the auditory task (Gibson et al. 1996) and/or lack of proficiency in Spanish (Alarcón 2009; Dowens et al. 2010; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2011; among others). This processing failure would render the sentences in (7a-b) completely ambiguous as both nouns would be coreferential with the adjective in the relative clause. In these cases, listeners would have to rely on other disambiguation strategies such as hierarchical structure (favoring high attachment in Spanish), prosody (Schafer 1996; Fodor 1998), or frequency of exposure to an attachment pattern (Cuetos et al. 1996; Mitchell and Cuetos 1991).

3. Previous Studies

To our knowledge, no research has studied the auditory processing of gender agreement across relative clauses in Spanish HS and L2 learner populations. Previous studies on HS and L2 learners have either examined the processing of gender agreement or the processing of ambiguous relative clauses as separate phenomena. For this reason, in the following subsections, we will provide a separate discussion of the studies carried out along these two lines of research.

3.1. Studies on Relative Clause Attachment Processing in English and Spanish

Most of the studies carried out on bilingual and L2 relative clause attachment processing to date have used offline (e.g., written questionnaires) and online (e.g., self-paced reading tasks) testing measures. However, only a few studies have examined the processing of relative clauses in the auditory modality. In the paragraphs that follow, we will first discuss the findings from the only study in the auditory modality by Felser et al. (2003b), even though its focus is on L2 learners and not HS. We will then move on to discussing Fernández (2003), the only study to our knowledge that examines the processing of ambiguous relative clauses in early bilingual populations. Lastly, we will review the larger body of L2 studies, which are all in the written modality. This will help us understand our comparison group and provide relevant context to introduce the factors that might affect HS’ attachment preferences.

Felser et al. (2003b) investigated the attachment preferences in ambiguous relative clauses by children and adult monolingual English speakers using an auditory questionnaire and an on-line self-paced listening task. Participants in this study listened to sentences which were temporarily ambiguous and contained a relative clause modifying the highest or the lowest noun phrase. The two noun phrases were linked either by the preposition of or the preposition with and the disambiguation occurred in the auxiliary (was vs. were). The stimuli were followed by an auditory comprehension question such as “Who was feeling tired?” to measure participant response accuracy. We provide illustrative examples of their stimuli in (10a-b).

- (10)

- The doctor recognized the nurse of the pupils who was/were feeling very tired.

- The doctor recognized the pupils with the nurse who was/were feeling very tired.

Felser et al. (2003b) found that adult native speakers of English had shorter reaction times and higher response accuracies in sentences forcing high attachment with the preposition of and in sentences forcing low attachment with the preposition with. The authors take their findings to suggest that adult native speakers of English are sensitive to the semantic properties of prepositions joining the two noun phrases and that this information helps them with relative clause disambiguation. Children, on the other hand, did not show this sensitivity. In fact, they found that children’s strategies differed depending on their verbal working memory capacity. Children with lower working memory applied the Recency (i.e., low attachment) strategy to disambiguate relative clauses. On the contrary, children with higher working memory relied on Predicate Proximity (i.e., high attachment), which is based on the hierarchical structure of sentences.

Let us look at work on relative clause attachment in early bilingual populations, which is the focus of this study. Fernández (2003) compared early Spanish/English bilinguals’ attachment preferences to monolinguals of both languages in both offline questionnaires and online self-paced reading tasks. Crucially, in both studies, bilinguals were divided by language dominance, which was determined by a series of questionnaires and self-ratings. In the online task, Fernández found no particular attachment preference, either across groups or across languages. In offline tasks, on the other hand, a main effect for language dominance was found. “English dominant bilinguals showed overall attachment preferences closer to those of English monolinguals, while Spanish-dominant bilinguals showed overall preferences closer to those of Spanish monolinguals” (Fernández 2003, pp. 213–14). It is worth noting that, in these studies, the age of acquisition of participants considered to be early bilinguals was set at 15 years or earlier, which entails that her group of participants may have included HS and L2 learners. As mentioned in the introduction, there is good reason to distinguish between these two types of groups (namely the age of acquisition, degree of exposure and level of proficiency and/or dominance in the target language).

Turning our attention back to L2 research, Felser et al. (2003a) examined the attachment preferences in ambiguous relative clauses by L1 Greek-L2 English and L1 German-L2 English learners in a series of offline and online (i.e., self-paced reading) tasks. The experimental stimuli used in these tasks were the same as the ones described in Felser et al. (2003b). Interestingly, they found that both experimental groups exhibited the same strong low attachment preference as in Felser et al. (2003b) for antecedents linked by the preposition with. However, no attachment preference was found for antecedents linked by the genitive preposition of. Felser et al. (2003a) argue that in these cases, attachment decisions made by L2 learners are completely random. The authors take these results to indicate that, regardless of their proficiency in English, neither of the L2 learner groups processed ambiguous relative clauses with genitive antecedents in a native-like manner. Recall that the English preference for these types of cases would be low attachment, whereas the preference for Greek and German would be high attachment. They conclude that although L2 learners are able to use lexical-semantic information during processing—as evidenced by their sensitivity to prepositions—they found no evidence that they were applying “the Recency strategy for genitive antecedents or transferred the predicate proximity strategy from their L1” (Felser et al. 2003a, p. 478).

Another study by Dussias (2003) examined relative clause ambiguity resolution strategies with genitive antecedents in proficient L2 learners of Spanish and English. Dussias (2003) found evidence for a unified processing strategy across languages, in this case based on language of immersion rather than language dominance. The study showed that while L1 English-L2 Spanish highly proficient learners exhibited low attachment in both languages in offline tasks, L1 Spanish-L2 English learners living in the U.S. also showed a low attachment preference, even for Spanish. A follow up study, Dussias and Sagarra (2007), provided further evidence that immersion plays a role in attachment preferences. In their study they found that L1 Spanish-L2 English learners with limited exposure to an English environment showed a high attachment preference in Spanish, akin to the monolingual control group. On the contrary, L1 Spanish-L2 English learners with extensive exposure to an English environment showed low attachment for Spanish sentences, similar to English monolingual speakers. Dussias and Sagarra conclude that their findings provide support for the Tuning Hypothesis, which states that frequency of exposure can affect individual attachment preferences in a language.

Along these lines, in a self-paced reading study Jegerski (2010) found that L1 English-L2 Spanish speakers who had lived in Mexico for many years processed Spanish relative clauses with genitive antecedents like Spanish monolinguals. This finding is consistent with the ones in Dussias (2003) and Dussias and Sagarra (2007) because Spanish was the language of immersion of the participants in her study. It is worth pointing out the copious research on relative clause processing in L2 in relation to the Shallow Structure Hypothesis (Clahsen and Felser 2006; Felser et al. 2003a; Jegerski 2010; among others). The Shallow Structure Hypothesis states that “the syntactic representations adult L2 learners compute for comprehension are shallower and less detailed than those of native speakers” (Clahsen and Felser 2006, p. 32). In its current form, this hypothesis can only account for L2 processing and makes no predictions for HS. Given that the current study focuses mainly on HS, the discussion about the implications of the Shallow Structure Hypothesis in our results is somewhat remote to our own focus.

To sum up, previous studies suggest that attachment preferences may be modulated by linguistic factors, such as the type of preposition (Felser et al. 2003a, 2003b) or language dominance (Fernández 2003); as well as extra-linguistic factors, such as the frequency of exposure to an attachment pattern (Dussias 2003; Dussias and Sagarra 2007; Jegerski 2010). The findings in Felser et al. (2003a, 2003b) highlight the importance of controlling for type of preposition in our stimuli. The preposition con ‘with’ has been reported to trigger attachment biases (i.e., low attachment), whereas the preposition de ‘of’ is more neutral, as it does not seem to trigger any attachment biases. Given that our goal is to study the processing of gender agreement to resolve potential attachment ambiguities in the auditory modality, we want the attachment decisions of our participants to be modulated solely by gender cues and not by some unwanted effect caused by the type of preposition. In addition, language dominance and frequency of exposure to an attachment pattern are important factors to consider in HS populations. We know that, in general, HS have more opportunities of exposure to the heritage language in the auditory modality than L2 learners do, which may result in a higher frequency of exposure to the attachment pattern of the heritage language (i.e., high attachment in the case of Spanish). This may explain HS’ processing behavior in auditory tasks and shed light on the structure of their mental grammars.

It is also important to note that all the studies discussed above, except for the study in Felser et al. (2003b), were self-paced reading studies. As we will discuss in the following subsection, self-paced reading studies favor L2 learners (Montrul et al. 2008, 2013), which places HS at a disadvantage as they are more frequently exposed to Spanish auditorily. Examining gender agreement processing in the auditory modality, which may favor HS, will allow us to better understand their ability to use gender agreement information for general comprehension and disambiguation purposes. Bearing this in mind, in the following subsection we will provide a summary of previous studies on the processing of gender agreement in Spanish.

3.2. Studies on Gender Agreement Processing in Spanish

Gender agreement processing involves constructing complex and, at times, discontinuous dependencies between different constituents in a structure (e.g., determiners, nouns, and adjectives) to create meaning. For this reason, the processing of gender agreement in a language like Spanish often presents a challenge to L2 learners and HS. Nonetheless, it is possible that HS could be more accurate processing gender agreement than L2 learners due to an earlier exposure to the Spanish language. In the following paragraphs, we will provide an overview of the recent studies on the processing of gender agreement by HS and L2 learners of Spanish.

We will start by discussing Montrul et al. (2008, 2013), which are—to our knowledge—the only studies that have examined Spanish HS’ gender agreement processing in nominal phrases. Montrul et al. (2008) and Montrul et al. (2013), investigating gender agreement knowledge in HS and L2 learners of Spanish both in written and oral tasks, found advantages for L2 learners in written, but not in oral tasks, where HS had a more noticeable advantage. The authors also observed that both groups made more gender agreement errors with feminine than with masculine nouns and more errors with non-canonical than with canonical nouns. The authors conclude that the type of task can explain the differences found between L2 learners and HS. The fact that HS acquire language early on in a predominantly aural context favors their performance in oral tasks, whereas written tasks, which require the use of more metalinguistic knowledge, favor L2 learners who received classroom instruction.

Regarding L2 research, an ERP study by Dowens et al. (2010) found electrophysiological evidence (i.e., P600 effects) during processing of gender agreement violations in advanced L2 learners of Spanish. This suggests that even when grammatical gender is absent in their L1, proficient L2 learners of Spanish show the same electrophysiological response as monolinguals. Dowens et al. also found that immersion experience in the L2 was correlated with a higher sensitivity to gender agreement violations. Alarcón (2009), Keating (2009), and Sagarra and Herschensohn (2011) found similar results using a number of on-line tasks (a matching task, an eye-tracking, and a moving window reading task, respectively). They found that sensitivity to gender agreement violations develops steadily in the L2 and may be detected in intermediate and advanced learners of Spanish.

In an auditory study examining L1 English-L2 Spanish processing of gender in determiners employing a looking-while-listening technique, Lew-Williams and Fernald (2010) found that the presence of a congruent gender-marked determiner immediately preceding a noun sped up lexical processing in monolinguals but not in L2 learners of Spanish.

A subsequent auditory study with L2 learners of Spanish by Dussias et al. (2013) employing the same looking-while-listening technique as in Lew-Williams and Fernald (2010), found that learners’ sensitivity to gender marking on the determiner was subject to proficiency effects. Higher proficiency L2 learners showed native-like patterns in using the gender cues in the determiner to speed up processing regardless of the gender of the determiner. This effect, however, was not found in lower proficiency L2 learners.

In short, previous studies have observed that there are several grammatical factors that may facilitate gender agreement processing, such as the default gender, noun canonicity (Montrul et al. 2008, 2013), and gender marking on the determiner (Lew-Williams and Fernald 2010; Dussias et al. 2013). Although these studies are mostly based on L2 research, the factors that facilitate gender agreement processing that stem from this research are still of importance for studies on HS populations. Moreover, note that all these studies focus on investigating L2 learners’, and to a lesser extent, HS’ use of gender cues to determine their sensitivity to gender agreement violations (Dowens et al. 2010; Lew-Williams and Fernald 2010; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2011; Dussias et al. 2013; Montrul et al. 2008, 2013). However, gender agreement violations rarely affect the comprehension of Spanish noun phrases. For instance, even if speakers process the gender agreement violation el casa ‘the.MASC house.FEM’, which contains a gender mismatch between the determiner and the feminine noun, they should still be able to understand the meaning of the noun phrase. On the contrary, the phenomenon of gender agreement across relative clauses offers an interesting avenue for processing research, as failure to auditorily process gender cues in sentences such as Mis amigos ven anuncios de películas que son divertidos ‘My friends watch the commercials of the movies that are fun’, renders the sentence ambiguous. In other words, if a speaker fails to process that the masculine adjective divertidos in the relative clause establishes a gender agreement relationship with the masculine noun anuncios instead of películas, the sentence may become completely ambiguous to them. Consequently, they may not be able to comprehend the intended meaning of the sentence because the adjective can potentially modify either noun.

Moreover, several studies (Alarcón 2009; Keating 2009; Dowens et al. 2010; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2011) have observed that proficiency plays an important role in gender agreement processing. However, most of these studies focus on L2 learner populations and not HS. As discussed in our introduction, HS also exhibit different degrees of proficiency and as such, it would be interesting to establish whether the effect of proficiency on gender agreement processing reported for L2 learners is also attested for HS. Finally, none of the studies reviewed in this section included measures of gender agreement processing in the auditory modality. As Montrul et al. (2008, 2013) point out, HS may have an advantage over L2 learners in oral tasks. Therefore, it would be instructive to see whether this advantage is also reflected in the auditory modality, which will allow us to better understand heritage grammars.

4. Research Questions, Hypotheses and Predictions

This study presents a novel approach to gender agreement processing by focusing on participants’ use of grammatical information (i.e., gender cues) to identify potentially competing referents in a sentence in the auditory modality. With this in mind, these are our goals: (i) to investigate to what extent HS and L2 learners are able to process gender cues in the auditory modality to determine whether the adjective in the relative clause agrees with the first noun (i.e., high attachment) or the second one (i.e., low attachment); (ii) to shed light on the grammatical factors (i.e., gender, noun canonicity and attachment type) that may facilitate this processing; and (iii) to explore whether external factors, such as Spanish proficiency, age of Spanish onset and language dominance—in the case of HS—play a role in their overall auditory processing accuracy. The study is guided by the following research questions:

- Do Spanish HS have an advantage over L2 learners on the processing of gender cues in the auditory modality to establish the intended adjective-noun agreement relationship?

- Does type of attachment (high vs. low), gender (masculine, feminine) and canonicity (canonical /non-canonical noun with gender-marked determiner) have a facilitative effect in the auditory processing of gender agreement in relative clauses?

- Do proficiency and age of Spanish onset play a role in the auditory processing of gender agreement by HS and L2 learners?

- Does heritage language dominance play a role in the auditory processing of gender agreement?

Most gender agreement processing studies discussed in Section 3 have focused on investigating HS’ and L2 learners’ use of gender cues to determine their sensitivity to gender agreement violations (Dowens et al. 2010; Lew-Williams and Fernald 2010; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2011; Dussias et al. 2013; Montrul et al. 2008, 2013). To our knowledge, no study to date has focused on the processing of gender cues for general sentence comprehension. In our study, comprehension is operationalized as the ability to establish the intended adjective-noun agreement relationship. Additionally, most research discussed in Section 3 has investigated this phenomenon in the written modality (e.g., self-paced reading tasks and questionnaires). However, the oral production results by Montrul et al. (2008, 2013) suggest that HS may display an advantage over L2 learners in the processing of gender agreement in this modality. If we extrapolate these results to the auditory modality, we can predict that HS may display an advantage over L2 learners on the auditory processing of gender cues to establish the intended adjective-noun agreement relationship. This follows from the fact that the auditory modality aligns with the way HS predominantly acquired Spanish early on.

Regarding our second research question, we anticipate that HS and L2 learners will be more accurate in the processing of the masculine (i.e., default) gender as reported in Montrul et al. (2008, 2013). In terms of canonicity, following Montrul et al. (2008, 2013) we hypothesize that HS and L2 learners will display higher accuracy rates processing gender agreement with canonical nouns than non-canonical ones. However, in the case of non-canonical nouns, L2 studies by Lew-Williams and Fernald (2010) and Dussias et al. (2013) have reported that the gender information encoded in the determiner facilitates processing. Thus, we hypothesize that we will also observe a facilitative effect of this factor in our L2 learners and, possibly, in our HS as well. As for the type of attachment, it is possible that if our participants fail to process gender agreement accurately, they will treat the sentences as ambiguous and not show any particular preference towards high or low attachment (see Felser et al. 2003a). On the contrary, any consistent attachment preference on our participants’ part, could be attributed to a particular processing strategy, the frequency of exposure to the Spanish attachment pattern (Dussias 2003; Jegerski 2010)—high attachment in the case of HS—or other potential factors.

Based on previous L2 studies (Alarcón 2009; Keating 2009; Dowens et al. 2010; Sagarra and Herschensohn 2011), which observed proficiency effects in gender agreement processing accuracy, we hypothesize that more proficient L2 learners—and possibly also HS—will be more accurate in their auditory processing of gender agreement across relative clauses. Similarly, we also hypothesize that earlier exposure to Spanish (i.e., age of Spanish onset), as reported in Montrul et al. (2008, 2013), will confer an advantage to HS over L2 learners in their gender agreement processing.

Finally, given the scarce empirical research carried out on the effects of language dominance on the processing of gender agreement in HS, it is difficult to draw definitive predictions. However, the few studies available (Montrul et al. 2008, 2013), suggest that the factors that determine language dominance, such as early language experience, age, and context of acquisition may play a role in HS’ processing of gender agreement. Based on these findings, we can predict that less Spanish dominant HS will be less accurate processing gender agreement than their more Spanish dominant counterparts.

In the following section, we describe the experiment that we conducted to investigate our research questions, predictions, and hypotheses.

5. Methods

5.1. Participants

Two groups participated in this study: a group of 20 HS of Spanish and a group of 20 L2 learners of Spanish who were raised monolingually in English. All participants were undergraduate students in a large American university and their age-range was between 19 and 28 years old. All received monetary compensation for their participation. Given that all participants came from upper-intermediate Spanish language courses, we included a short language history questionnaire to determine the degree of exposure to the target language during childhood, schooling, and study abroad contexts. This questionnaire also allowed us to filter HS from L2 learners. None of the L2 learners reported having any exposure to Spanish during childhood or in study abroad contexts; and all had less than two years of exposure to the language during high school. The average age of Spanish onset for the L2 group was 18.36 years (SD = 2.08). Additionally, none of the participants in the L2 and HS groups reported learning or speaking languages other than English and Spanish. Those participants that reported having a certain degree of exposure to Spanish during childhood were considered potential HS and were automatically administered the Bilingual Language Profile (BLP) questionnaire (Birdsong et al. 2012).

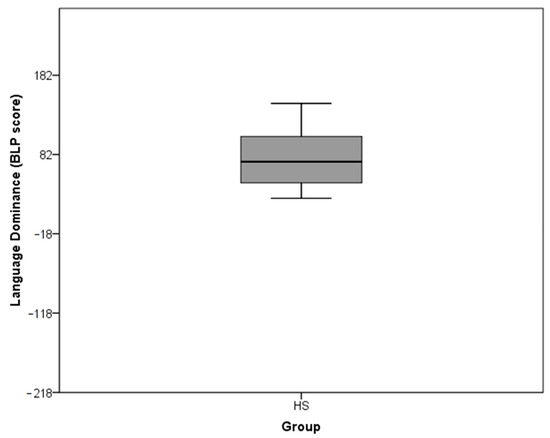

The BLP assesses the participants’ language dominance through self-reports and outputs a continuous dominance score and a general bilingual profile considering the following modules: language history, language use, language proficiency, and language attitudes. Taken together, these modules provide an estimation of language usage patterns. HS often have a closer relationship with the heritage language than L2 learners do, and as such, more opportunities to use it outside of the academic setting. It is important to point out that an individual’s relationship with language is not static and may change over time. However, an assessment of HS’ language use and experience through a continuous dominance score, may shed light on their linguistic choices and heritage language processing at the time of our study. The responses of the BLP generate a language score for each module and a global score for each language, the maximum global score being 218. These scores are converted to a scale score with the Spanish score subtracted from the English score. Thus, a more positive or negative score reflects English or Spanish dominance. The scores for the HS group ranged from 24.8 (slightly English dominant) to 146.47 (English dominant). The large range in dominance scores highlights the heterogeneity of this group regarding their Spanish and English language use and experience. Although all participants are mostly English dominant—which is expected given that most of them reported commonly using English at university or in the workplace, as well as with friends—they also reported speaking Spanish frequently in the household and with their family. Figure 1 provides the distribution of the dominance scores for the HS group.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the language dominance scores for the heritage speakers (HS) group according to the Bilingual Language Profile (BLP).

The demographic results of the Bilingual Language Profile (BLP) revealed that 15 HS were born in the United States to Spanish-speaking parents from Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela. Five HS were born in Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela, but reported having emigrated to the United States before the age of four. The average age of Spanish onset for the HS group was 2.05 years (SD = 2.42). Additionally, all participants in this group reported being schooled in English before the age of five. As is often the case with HS, our participants experienced different degrees of input and output in Spanish at home throughout their lives, but for most of them it remained quite stable. Most HS reported having a strong emotional bond with their heritage language, which was reflected in their overall positive attitudes towards Spanish.

Regarding self-reported proficiency, Table 1 provides a summary of HS’ average scores for both languages in the BLP questionnaire. The average score shown in this table combines the self-reported proficiency scores for speaking, understanding, reading, and writing on a scale of zero (not very well at all) to six (very well).

Table 1.

HS’ average self-reported proficiency scores for Spanish and English.

Overall, HS’ self-reported proficiency in English was higher than that of Spanish. However, HS’ self-reported proficiency in the heritage language should be taken with a grain of salt, as this group often has the tendency to undervalue their heritage language skills (Benmamoun et al. 2010). Given this, we included another measure to determine target language proficiency in the HS and L2 learner groups: a 50-question proficiency test. As described in Duffield and White (1999), the first 30 questions of this proficiency test come from the reading/vocabulary section of the MLA Cooperative Foreign Language Test (Educational Testing Service, Princeton, NJ) and the remaining 20 questions come from the cloze test section of the Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera (DELE) (Embajada de España, Washington, DC)4. Although we acknowledge that this test may be biased toward the Peninsular variety of Spanish, and its written and explicit nature may not provide a very accurate indication of HS’ proficiency (Valdés 1995), we decided to include it for its comparability with many other studies with HS who have also used this test (Montrul et al. 2008, 2013; Montrul and Perpiñán 2011; Montrul and Ionin 2012; among others). For ease of reference and comparability, we will henceforth refer to this test as the DELE. As Table 2 shows, the average DELE score for L2 learners was 34.63 (SD = 5.06). On the other hand, the average DELE score for HS was 38 (SD = 5.36). Additionally, the original HS group had two participants that we did not include in this study as their DELE scores were more than ten points lower than the averages reported for the L2 learner and HS groups.

Table 2.

Mean score and standard deviation on the Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera (DELE) proficiency test by Group.

A one-way ANOVA compared L2 learners and HS according to their DELE scores and revealed a significant effect for Group (F(1,38) = 4.954, p = 0.032). In other words, HS’ average DELE scores were significantly higher than those of L2 learners.

5.2. Experimental Materials

The experimental materials consisted of 32 adjective relative clauses in Spanish containing two plural nouns in the main clause with gender mismatches and only one possible adjective–noun agreement. All relative clauses had the general structure presented in (11) with the same preposition (i.e., de ‘of’) linking the two nouns in the main clause followed by copulas (i.e., ser or estar ‘to be’) in the relative clause.

- (11)

Nosotros arreglamos [puertas]NP1 de [apartamentos]NP2 que están viejas. we fix doors.FEM of apartments.MASC that are old.FEM ‘We fix the doors of the apartments that are old’

In addition, half of the stimuli forced gender agreement of the adjective with the first noun (i.e., high attachment) and the other half with the second noun (i.e., low attachment). We also controlled for noun-animacy by only including inanimate nouns as some evidence suggests that animacy features affect attachment (see Desmet et al. 2002). Additionally, half of the stimuli had masculine noun-adjective agreement and the other half feminine. We also designed our materials to test for factors such as canonicity, including canonical nouns (e.g., ‘-o’[MASC] / ‘-a’[FEM]) in half on the stimuli; and non-canonical nouns with a gender-marked determiner (e.g., los[MASC] países ‘the countries’/las[FEM] ciudades ‘the cities’) in the other half5. All adjectives in the relative clause portion of each stimulus had canonical gender markings. All the nouns and adjectives used in the stimuli either were cognates or were taken from beginner and intermediate Spanish-language textbooks6 so that all participants would be familiar with the words used in the target stimuli, thus avoiding any lexical knowledge confounding effects (Mecartty 2000; Matthews 2018). Following Fernández (2003), we controlled for semantic plausibility by making sure that the adjectives in the relative clause could semantically refer to either noun if we were to take gender markings out of the equation. In addition, we controlled for prosodic factors including number of sentence syllables (Quinn et al. 2000) and word prominence (Jun and Bishop 2015). Quinn et al. (2000) observed that having an unequal number of syllables in each stimulus could potentially trigger attachment biases. For this reason, all of our stimuli were 20 syllables in length with no words separating the copula from the adjective in the relative clause portion. Similarly, Jun and Bishop (2015) reported that word prominence could also trigger attachment biases. Taking this into consideration, and in order to minimize human error (i.e., a human speaker inadvertently giving away the correct attachment by uttering one of the target nouns more prominently), we used a female synthetic voice speaking the Mexican-Spanish variant using the Read Aloud function of Microsoft Word. The synthetic voice read each sentence at a normal reading pace and we recorded each stimulus in separate audio files. For written versions of our target stimuli, we refer the reader to Appendix A.

Most importantly, two consultants who were first- and second-generation HS of Venezuelan and Mexican descent, respectively, evaluated all sentences for semantic plausibility. This ensured that participants would have to rely only on gender agreement processing to identify the right referent in the sentence. They also checked that all of our stimuli included vocabulary that was part of their respective varieties of Spanish.

The experimental materials also included 48 aural distractors. The sentences in (12) and (13) exemplify the structure of the distractors used in the study. All contained a subject noun phrase comprised of two nouns and linked by the genitive preposition de ‘of’ followed by a copula verb and an adjective describing one of the nouns. These were very similar to the target stimuli with some crucial differences: none of them contained relative clauses, and nouns could be animate or inanimate. All the distractors were aurally recorded using the same procedure described in the previous paragraph.

- (12)

El libro de la chica es verde the book of.GEN the girl is green ‘The girl’s book is green’ - (13)

El perro del hombre es viejo the dog of.GEN.the man is old ‘The man’s dog is old’

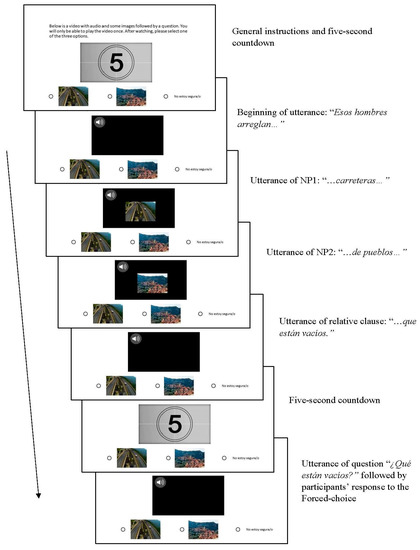

5.3. Task

The task used for the study was a forced-choice task where participants listened to each auditory stimulus only once. We embedded each stimulus in a video, which we presented on a computer screen with a five-second countdown prior to the audio playing. The video displayed a picture that represented each of the target nouns as the female synthesizer uttered them. After another five-second countdown, the synthesizer uttered a question. For example, a sentence like (11) would be followed by the question ¿Qué están viejas? ‘What are old?’. Subsequently, we asked participants to choose between two images that represented each noun in the main clause. This allowed us to determine which of the two nouns they considered as the referent of the adjective. For half of the questions the correct picture appeared on the right side of the screen, and for the other half on the left side. We also included a third option “I am not sure”7 to account for those cases in which participants could not identify a noun referent for the adjective in the relative clause. See Figure A1 in Appendix B for a detailed illustration of the procedure described in this paragraph.

We used the same task for the aural distractors, albeit with questions that were completely unrelated to the phenomenon under investigation. For instance, a sentence like (12) would be followed by the question ¿De qué color era el libro de la chica? ‘What was the color of the girl’s book?’; and a sentence like (13) with ¿Cuántos perros tiene el hombre? ‘How many dogs does the man have?’, respectively. We presented participants with the same number of answer choices as in the target stimuli and a picture accompanied each choice. None of the experimental materials displayed on the screen contained any written words except for the instructions on how to complete the task.

5.4. Procedure

We distributed the study to the participants in an online survey format using Qualtrics. However, given the length of the experimental session, all participants carried out the study in a testing room at the university in order to maximize completion rates. Because the testing room had a limited capacity, we scheduled participants in advance and tested them over three days. After signing the consent forms at the testing site, a research assistant provided them with a set of headphones and asked them to sit in front of a computer to complete the study.

Ten late learners of English who were raised monolingually in Spanish8 attended the first day of testing and completed a modified version of the survey, which did not include the DELE or the BLP. We included these late learners to control for potential problems during testing and ensure that all of our experimental materials resulted in the right attachment type (i.e., high/low) based on gender agreement between the adjective and the noun. All of them completed the task in around 30 minutes with a 99.1% response accuracy. This shows that they were all able to establish the type of attachment accurately based on the gender agreement information that they had processed in the auditory modality.

On the second and third days, we scheduled the rest of the participants, who where students in upper-intermediate Spanish language courses. All participants completed short demographic and language history questionnaires. These questionnaires were designed to filter those participants that reported speaking Spanish at home at an early age. While HS completed the BLP and the DELE, L2 learners were only asked to complete the DELE and not the BLP. After completing these questionnaires, participants were given detailed instructions on how to perform the forced-choice task, followed by five aural practice trials containing three distractors and two target stimuli. During this time, no direct feedback was provided to participants, but they were allowed to resort to the research assistant for help with general questions and troubleshooting. This helped them become familiar with the nature of the task. These practice trials were separate from the 80 auditory stimuli presented in the experimental materials and were not considered for the study. After completing the practice block, they moved on to the forced-choice task, which included the experimental materials. We pseudo-randomized all materials so that at least one or two distractors separated each target stimuli. While the HS group took a bit longer to finish the study, both groups completed it in under an hour.

5.5. Analysis

For the analysis, we measured participant accuracy in the forced-choice task with a score of one for correct, and a score of zero for incorrect responses. Given that the “I am not sure” responses were very few—only six responses of this type were observed in the L2 learners group and five in the HS group—we coded these responses with a score of zero as well. This yielded a total of 1248 observations for the statistical analysis. Initially, we conducted several stepwise regression models in R to find the subset of factors that resulted in the best performing statistical model. For each model, we set response-accuracy as the dependent variable and Group (HS, L2 learners), Attachment (high, low), Gender (masculine, feminine) and Canonicity (canonical /non-canonical noun with gender-marked determiner) as fixed factors. We also included Age of Spanish onset and Proficiency (i.e., DELE scores) as continuous factors. The models that we ran included the fixed factors as independent or the interactions between them. To identify the model that best fitted the data, we chose the most reliable models with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)9 values and compared them using the ANOVA function in R. Subsequently, we conducted a mixed-effects linear regression model using the glmer function in R (Bates et al. 2012) with the best performing model, which included Group, Attachment, Canonicity, Proficiency, and Age of Spanish onset as independent fixed factors. Because gender was the least contributive predictor, we removed this variable from the regression model as it did not make a statistically significant contribution to how well the model predicted the outcome variable.

We also carried out within-group mixed-effects linear regression models for the HS and L2 learner groups. These models used the same variables as the between-group model just described with one exception: the model for HS included Dominance (i.e., BLP scores) as an additional continuous factor. All models included Participant and Item as random intercepts. This minimized the effect of undue influence of particular individual speakers and unexpected or potential unbalancing of our experimental stimuli10.

6. Results

Before we move to discuss the inferential statistics to shed light on the research questions in Section 4, let us discuss some general descriptive patterns that can be observed in our data.

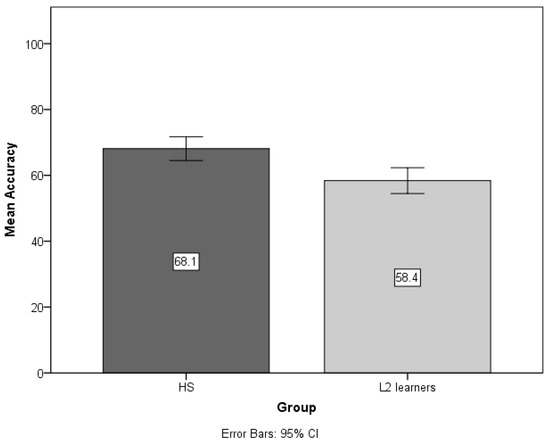

Figure 2 displays the overall mean accuracy of gender agreement processing for each group. This figure shows differences in gender agreement processing accuracy between HS and L2 learners. Descriptively speaking, HS (M = 68.1%) outperformed L2 learners (M = 58.4%) in their gender agreement processing accuracy in the auditory modality.

Figure 2.

Mean accuracy of gender agreement processing by group.

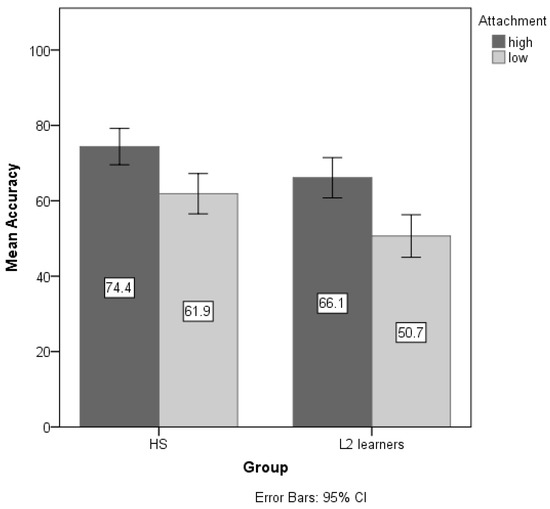

Let us now examine the grammatical factors that may have a facilitative effect in the auditory processing of gender agreement. A closer examination of the mean accuracy by attachment type for each group in Figure 3, revealed that both groups were consistently more accurate auditorily processing gender agreement in high attachment cases (HS M = 74.4%; L2 learners M = 66.1%) than in the low attachment ones (HS M = 61.9%; L2 learners M = 50.7%).

Figure 3.

Mean accuracy of gender-agreement processing by attachment type for each group.

With regard to the overall mean accuracy by noun canonicity, participants were slightly more accurate processing gender agreement when the adjective in the relative clause agreed with the determiner of a non-canonical noun (M = 67%) than when it agreed with a canonical noun without a determiner (M = 59.8%). In terms of gender, participants were almost equally accurate processing both genders: the feminine (M = 64.7%) and the masculine (M = 62%).

In light of these quantitative differences, we carried out a between-group mixed-effects linear regression model to test our hypotheses with regard to the effect of the auditory modality by group; the grammatical factors that facilitate gender agreement processing in the auditory modality; and the effect of proficiency and age of Spanish onset on the outcome variable. As mentioned in the analysis section, the best fitted model, summarized in Table 3, does not include the factor gender as it was the least contributive predictor.

Table 3.

Between-group mixed-effects model of the factors contributing to gender-agreement accuracy in the auditory modality.

The results in Table 3 show that Proficiency was a significant predictor of gender agreement processing accuracy in our data. This result suggests that, overall, as Spanish proficiency increases so do the odds of accurately processing gender agreement auditorily. The logistic regression model also reported that Group was a significant predictor of the outcome variable. In other words, the odds of auditorily processing gender agreement accurately were significantly higher for HS than L2 learners. This result points to the fact that HS are more accurate than L2 learners in the auditory processing of gender cues to determine whether the adjective in the relative clause agrees with the first (i.e., high attachment) or the second noun (i.e., low attachment). Additionally, Attachment was the only significant grammatical factor that explained gender agreement processing accuracy. This particular result is in line with our initial observation of the descriptive data, as participants were more accurate in cases of high attachment than low attachment. On the contrary, Canonicity and Age of Spanish onset were not significant, which means that they were the least contributive predictors of our outcome variable in between-group comparisons. To provide a more in-depth analysis of the impact of the predictor variables for each group, we carried two additional within-group mixed-effects linear regression models. Table 4 reports the within-group analysis for the HS group. Note that the analysis for this group includes Dominance as an additional factor.

Table 4.

Within-group mixed-effects model of the factors contributing to HS’ gender-agreement accuracy in the auditory modality.

Once more, the large effect size found for Proficiency in Table 4 shows that this variable was a significant predictor of gender agreement processing accuracy in the HS group as well. On the contrary, Dominance—the newly integrated factor in this analysis—was not a significant predictor of HS’ gender processing accuracy. That is, the degree of Spanish dominance in our HS participants did not have an effect on the outcome variable. In contrast, Age of Spanish onset was a significant predictor of HS’ accuracy in the task. This is very interesting, as we did not find this factor to be significant in the between-group analysis reported in Table 3. This result suggests that an earlier exposure to the Spanish language by HS increased the odds of accurately processing gender agreement auditorily. Moreover, as in the between-group analysis, Attachment was a significant predictor of accuracy in this group as well. Canonicity was not significant for the HS group. Table 5 presents the within-group analysis for the L2 learners group.

Table 5.

Within-group mixed-effects model of the factors contributing to L2 learners’ gender-agreement accuracy in the auditory modality.

Except for Attachment, none of the factors in the within-group mixed-effects model for L2 learners were significant predictors of their accuracy processing gender agreement auditorily. Contrary to what we observed for HS, Proficiency and Age of Spanish onset were not significant predictors within the L2 learners group11.

To summarize, our best fitted mixed-effects linear regression analyses were the ones that contained main effects without interactions. The between-group analysis revealed that Spanish language proficiency was a good predictor of accuracy processing gender agreement auditorily overall. We also observed a significant effect for Group, which suggests that, overall, HS are more accurate than L2 learners in their use of gender agreement information for general sentence comprehension purposes. The within-group analysis for HS also indicated that Spanish language Proficiency and Age of Spanish onset were significant predictors of the odds of accurately processing gender agreement. This result contrasts sharply with what was observed for the L2 learners, as neither of these two factors turned out to be significant for this group. In terms of grammatical factors, Attachment was the only significant predictor that explained gender agreement processing accuracy in both groups, as participants were more accurate in cases of high attachment than low attachment. Bearing these results in mind, let us move to discussing their implications in terms of our research questions, hypotheses, and predictions.

7. Discussion

Recall that our first research question investigated whether Spanish HS had an advantage over L2 learners on the processing of gender agreement in the auditory modality for sentence comprehension. The significant difference found between both groups in our task indicates that HS are more accurate than L2 learners in the auditory processing of gender cues to determine whether the adjective in the relative clause agrees with the first or the second noun in the main clause. This is an important finding because it allows us to better understand the differences between heritage and L2 grammars in terms of comprehension of the auditory input. More precisely, this finding indicates that not only are HS more accurate processing incoming auditory input in the form of gender cues, but that they also exhibit advantages in their use of this information to establish the intended adjective-noun agreement relationship.

Our second research question investigated the grammatical factors that may facilitate HS and L2 learner’s auditory processing of gender agreement across relative clauses. Recall that the factors under scrutiny were gender (masculine, feminine), canonicity (canonical noun/non-canonical noun with a gender-marked determiner) and attachment type (high vs. low). Starting with gender, we failed to replicate the findings in Montrul et al. (2008, 2013). Recall that Montrul et al. reported that HS and L2 learners were more accurate processing gender agreement with masculine nouns and determiners in the written and oral modalities. This, however, was not the case among the participants in our study, as we found that gender was the least contributive predictor to our statistical model. We take this finding to suggest that, at least in the auditory modality, gender did not have any facilitative effect on processing, as our participants did not show any kind of gender bias overall. Similarly, noun canonicity did not have a facilitative effect in the processing of gender agreement in the auditory modality. However, based on the findings in Dussias et al. (2013), we hypothesized that the gender-marked determiner with non-canonical nouns could potentially help participants with processing. Once more, this hypothesis was not borne out by our data.

We did, however, find an interesting pattern with regard to attachment type that merits an extensive discussion in the following paragraphs. Overall, participants were more accurate processing gender agreement in the auditory modality in cases of high attachment than low attachment. If we combine this finding with the different accuracy rates in HS and L2 learners’ auditory processing of gender agreement, we can conclude that the preference for high attachment displayed across participants is not random. In the following paragraphs, we will evaluate to what extent this attachment preference can be attributed to previously suggested factors, such as age of Spanish onset (i.e., early exposure in Montrul 2013) and/or task effects (Montrul et al. 2008, 2013).

If we examine participants’ higher accuracy on the high attachment cases under the lens of age of Spanish onset, we can attribute HS’ higher performance to their earlier exposure—mostly auditory—to the heritage language. Recall that the Predicate Proximity strategy (i.e., high attachment) is the preferred processing strategy for ambiguous relative clauses in Spanish (Cuetos and Mitchell 1988). Therefore, when HS fail to process gender agreement auditorily across relative clauses, they lack crucial information (i.e., gender cues) to disambiguate these types of clauses. Furthermore, they cannot rely on non-structural information such as thematic roles for disambiguation (see Felser et al. 2003a, 2003b), as all of our auditory stimuli included noun phrases linked by the genitive preposition de ‘of’. In these types of constructions, the current thematic processing domain is the overall complex NP and, as a consequence, constructions such as anuncios de películas ‘the commercials of the movies’ are likely to be treated as single chunks. This makes disambiguation based on thematic roles even more difficult. Based on Felser et al. (2003a), our participants’ attachment preferences in these cases should be completely random. However, this prediction is not borne out, as HS display higher accuracy rates in the high attachment cases. Thus, we can assume that HS may be applying the preferred processing strategy for ambiguous sentences in Spanish—Predicate Proximity—which is based on the hierarchical structure of sentences. This would be in line with the Tuning Hypothesis proposed in Cuetos et al. (1996) and Mitchell and Cuetos (1991), which states that frequency of exposure to a language can affect HS’ processing strategies so that they pattern with those of the language of exposure, in this case Spanish. However, neither age of Spanish onset nor the Tuning Hypothesis can successfully account for L2 learners’ higher performance in the high attachment cases. Recall that for this group, age of onset was not a significant predictor of their odds of processing gender agreement accurately. Thus, their performance cannot be attributed to an earlier exposure to Spanish, which is expected given that most of these participants learned the language later in life. For this reason, we would like to discuss the type of task as a possible explanation to the high attachment pattern observed across groups.

Considering that L2 learners have a very different context of acquisition of Spanish than HS, it is surprising that we still find the same high attachment preference that we find among HS. This finding suggests that they are relying on the Predicate Proximity strategy rather than Recency—the attested attachment preference for English, their L1. Although this pattern aligns with the high attachment preference in Spanish, it is unlikely that these learners have adopted the processing strategy of their L2. These learners receive limited input in the L2 and mostly in a classroom setting. Additionally, research shows that the processing of relative clauses presents a challenge for L2 learners and that these structures are one of the last to be learned (Gass 1979; Doughty 1991; among others). However, the high attachment pattern that we observe in L2 learners cannot be random, and it is likely to indicate a task effect. Thus, when our HS and L2 learners fail to process the morpho-syntactic features involved in gender agreement, the sentence becomes completely ambiguous to them, which makes them rely on ambiguity resolution strategies influenced by the experimental task. Recall that in the auditory processing model that we are adopting here (Vandergrift and Goh 2012), processing starts with perception of the auditory signal. Based on this, it is likely that in our auditory task, HS and L2 learners start by processing the beginning of the acoustic signal as they perceive it—in this case the first noun phrase—and hold it in the phonological loop for further processing. Since auditory processing is not linear, while participants are trying to process the rest of the incoming input, they are also using their knowledge sources (e.g., linguistic knowledge) to further process the beginning of the input. It is possible that the grammatical cues on the second NP may not be processed successfully given the limited cognitive processing resources available. On the contrary, the adjective inside of the predicate (i.e., the relative clause) is the last thing they hear in the aural signal, which gives it a better chance for processing. The adjective now becomes a much better candidate for attachment to the first noun than to the second one. Thus, we can assume that the type of task presented to HS and L2 learners in this study seems to favor the Predicate Proximity strategy in the event of an ambiguity triggered by a morpho-syntactic processing failure. This is another important contribution of our study since no research has examined the auditory processing of gender agreement cues to identify potentially competing referents in a sentence.

Our third research question investigated whether proficiency and age of Spanish onset played a role in the auditory processing of gender agreement by HS and L2 learners. The main effects found for proficiency and age of Spanish onset in our analysis indicate that these two factors play an important role in gender agreement processing accuracies in HS but not in L2 learners. This highlights the positive impact that an earlier exposure to a predominantly auditory input in the heritage language has in processing (i.e., ability to automatically process aural input). If we connect this finding to the large effect size found for Group in the between-group analysis, we may even interpret this result as suggestive evidence that the auditory modality confers an advantage to HS over L2 learners on the processing of gender agreement. As the findings in Montrul et al. (2008, 2013) suggest, the oral modality confers an advantage to HS over L2 learners on their processing of gender agreement, thus, it is possible that the auditory modality confers this advantage as well. However, this will require further research comparing between-group performances in the written and the auditory modality in order to draw more definitive conclusions.

Lastly, HS’ language dominance was not a significant predictor of their accuracy processing gender agreement in the auditory modality. Thus, with regard to our fourth research question, we reject our original prediction regarding the role of dominance. That is, in our HS population sample, we did not find enough evidence to support that more Spanish dominant HS had an advantage over less Spanish dominant ones.

8. Limitations and Future Research

The data from this study come from a larger research project investigating the auditory processing of syntactic dependencies among bilinguals and L2 learners. Thus, in future studies we aim to increase our participant pool and test HS and L2 learners’ attachment preferences in ambiguous relative clauses in both of their languages. We also aim to compare the processing of gender agreement in the written and the auditory modality in these two groups. This will allow us to establish whether the auditory modality confers an advantage to HS over L2 learners.

Future research should also explore the impact of phonological working memory on participants´ processing of gender agreement across relative clauses. Recall that Felser et al. (2003b) found a relationship between children’s attachment preferences and differences in working memory. Children with lower working memory relied on the low attachment (i.e., Recency) strategy for disambiguation, while those with higher working memory relied on the high attachment (i.e., Predicate Proximity) one. Although we did not include measures of working memory in our study, we find it unlikely that the consistent high attachment preference found among our participants can be explained by differences in working memory. If working memory effects were at play in our study, then we would have to assume that all of our participants had similar working memory capacities as they all exhibited the same attachment preference.

9. Conclusions

This study has presented a novel approach to research on processing of gender agreement by focusing on the use of gender agreement information to identify potentially competing referents in a sentence in the auditory modality. Our study has made three important contributions. First, it allows us to better understand the differences between heritage and L2 grammars in terms of comprehension of the auditory input. More precisely, our findings indicate that not only are HS more accurate processing incoming auditory input in the form of gender cues, but that they also exhibit advantages in their use of this information to determine whether the adjective agrees with the first noun (i.e., high attachment) or the second one (i.e., low attachment). Second, we found that Spanish language proficiency and age of Spanish onset were significant predictors of gender agreement accuracy in HS but not in L2 learners. This highlights the positive impact that an earlier exposure to auditory input in the heritage language has for processing. Finally, the consistent higher accuracy rates that we find in cases of high attachment across both groups points to an ambiguity resolution strategy that may be influenced by the experimental task itself. In other words, when participants fail to process gender agreement information, they treat these sentences as ambiguous, which favors the use of the Predicate Proximity strategy (i.e., high attachment) for ambiguity resolution purposes. The implication from these findings is that the research methodology and the task modality matter when it comes to drawing conclusions about how the processing of syntactic dependencies impacts comprehension, and also help us understand the mental grammars of HS and L2 learners who differ in their language acquisition context and language experiences.

Author Contributions