Abstract

Studies have found that aspects of grammar that lie at the syntax–pragmatics interface, such as the use of pronominal subjects in null-subject languages, are likely to undergo cross-linguistic influence in bilingual speakers. This study contributes to our understanding of the role of Spanish immersion academic instruction on the comprehension of null subjects in English-dominant, Spanish-heritage children living in the United States. Two groups of bilingual children aged 4 to 7 (those attending a Spanish immersion school and those not) completed an acceptability judgment task in both English and Spanish. English monolingual children and monolingually raised Spanish children of the same ages also completed the task in their respective languages. The findings revealed that children in the Spanish immersion school performed on par with their monolingual peers in Spanish, but accepted significantly more ungrammatical null subjects in English than the other groups. These results suggest that immersion schooling plays a role in extending the English null subject stage in bilingual children due to competing input and cross-linguistic influence.

1. Introduction

Heritage bilingual children have been shown to undergo differential language development patterns and to display divergent outcomes to monolingual children and to dominant bilinguals in non-heritage contexts. Heritage speakers are raised in homes where a non-majority language is spoken (Valdés 2000). As they acquire and use their languages for different purposes, in different contexts and with different people, heritage language children are rarely equally proficient in both languages because input and domains of use play a significant role in bilingual linguistic development (Grosjean 1998; Polinsky 2007; Paradis 2011; Gathercole 2016; Montrul 2016). This study is concerned with the effect of input in the form of academic instruction on the development of grammar in Spanish heritage children living in the United States. Specifically, we address bilingual children’s understanding of pronominal subjects, an area of grammar that lies at the syntax–pragmatics interface, in both English, the dominant language of the society, and Spanish, the heritage language. Our aim is to understand the impact of immersion schooling, an environment that provides greater and richer input availability of the heritage language, on the acceptability of null subjects in Spanish for heritage speakers, and to explore any differences between bilingual and monolingual children’s acceptability of null subjects in English.

Evidence that quantity of input influences the progress of bilingual development is robust (Montrul 2004a; Montrol and Potowski 2007; Polinsky 2007; Kupisch and Pierantozzi 2010). School-aged heritage bilingual children generally have less exposure to the heritage language, limited to the home and immediate community, and therefore experience reduced input (Paradis 2011). However, fewer studies have been done on input quality (Paradis and Navarro 2003; Pires and Rothman 2009; Gathercole 2016), which is also a variable factor. Input quality refers to variation in the form of multiple dialects, differing proficiency levels, and domains of use. This study addresses differences in input quality and quantity by comparing heritage children educated in Spanish at an immersion school with those educated at English only schools.

“Variation in the form and use of a structure in the input could lead to optionality in the learner’s use and processing of that structure and/or influence a learner’s underlying linguistic representation for that structure, leading to non-convergence with the monolingual grammar” (Paradis 2011, p. 68). This non-convergence with the monolingual grammar is described by researchers as a disruption of the language acquisition process in children leading to bilingual speakers who are not like two monolinguals in one (Grosjean 1998). While a variety of explanations have been offered to account for the divergence of heritage language grammars such as incomplete acquisition (Montrul 2004a; Montrul 2016; Polinsky 2007; Rothman 2009) or differential acquisition (Kupisch and Rothman 2016), in this paper, we will refer to Putnam and Sánchez’s (2013) notion of feature reassembly for heritage speakers (adapted from (Lardiere 2008) proposal) because of its focus on activation and uptake, which is especially relevant in the context of immersion education (Kupisch and Rothman 2016). Putnam and Sánchez (2013) propose a model in which heritage language acquisition should be regarded as a process rather than as a result. Rather than reduced input of the heritage language or dominance of the majority language determining the outcome of this process, they posit that what fluctuates are a bilingual’s levels of activation of the lexicon and the strength of the association among functional, semantic, and phonological features. Heritage speakers undergo a continuing process of feature transfer or reassembly drawing from features in both languages. Crucially, this model provides support for the notion that in acquisition, activation for comprehension and production purposes is required to retain associations among functional, semantic and phonological features. Levels of activation vary throughout a bilingual’s life so that the variability and divergences heritage speakers display, usually in their minority language, stem from lower levels of morphosyntactic activation (language output). The result is the formation of a new system formed by elements of both of their languages and dependent on language activation and use (Yager et al. 2015).

Putnam and Sánchez’s (2013) model provides an ideal framework within which to investigate how increased levels of activation of the heritage language in the form of immersion education can have an impact on the acquisition of null subjects in both the heritage and dominant languages of a child. A large body of literature has found variation in the use of pronominal subjects by bilingual children in both production (Paradis and Navarro 2003; Hacohen and Schaeffer 2007; Haznedar 2010; Liceras et al. 2012; Austin et al. 2017) and comprehension (Argyri and Sorace 2007; Serratrice 2007; Sorace et al. 2009), demonstrating that this is an area of grammar that merits attention in heritage language acquisition. Immersion education provides an environment with greater opportunity for activation and use of the heritage language and, therefore, may have an effect on children’s acquisition of null subjects in both of their languages.

In what follows, we address pronominal subjects in English and Spanish, and the syntax–pragmatics interface, as well as previous research on early monolingual and bilingual acquisition of null subjects. Next, we look at the literature on the effect of input and academic instruction on heritage language maintenance. Subsequent sections include a description of the study, presentation of the results, and a discussion of the findings with implications for education and future research.

2. Null Subjects

Though there is general consensus that bilingual first-language acquisition entails the development of independent and parallel syntactic systems (Meisel 1989; Genesee et al. 1995), quite a few studies have found that some particular aspects of grammar, those that lie at the syntax–pragmatics interface, have been found to be likely to undergo cross-linguistic influence in language contact situations (Hulk and Müller 2000; Müller and Hulk 2001; Montrul 2004a; Sorace 2004; Rothman 2009; Sorace et al. 2009; Paradis and Navarro 2003; Austin et al. 2017). Pronominal subjects fall at this syntax–pragmatics interface because of their reliance upon both syntactic knowledge and discourse-pragmatic knowledge (Sorace and Serratrice 2009). There are differences between pronominal subjects across languages like English and Spanish, which have led researchers to test hypotheses about the syntax–pragmatics interface, as will be discussed further in Section 2.2.

2.1. Pronominal Subject Realization

English is a non-null-subject language in which null subjects are never allowed in declarative clauses, regardless of the discourse-pragmatic context (Chomsky 1981; Barbosa 2011), as seen in sentences 1 (a) and 1 (b) below:

- 1.

- (a) Teresa told us that she went to a party.(b) Teresa told us that went to a party.

Spanish, on the other hand, is an agreement-based null-subject language in which a subject’s number and person can be identified in the verb’s inflection or in the context without always needing a subject pronoun (Rizzi 1986; Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1998; RAE and ASALE 2009; Camacho 2013), and in which null and overt pronoun distribution is guided by a series of pragmatic constraints including topic shift and topic continuity (Frascarelli 2007)1. Topic continuity is the reference to a previously introduced topic as seen in sentence 2 (a) below and topic shift is the introduction of a new topic in discourse as in the example in 2 (b) below in which the expressed pronoun ella (she) is used to denote a new or different referent in the discourse:

- 2.

- (a) Teresa llegó al aeropuerto tarde. (pro) Estaba cansada‘Teresa arrived at the airport late. She was tired’.(b) Teresa y Juan llegaron al aeropuerto tarde. Ella estaba cansada.‘Teresa and Juan arrived at the airport late. She was tired’.

In general, Spanish speakers of all dialects favor null subjects in topic continuity contexts and overt subjects in topic shift contexts (Flores-Ferrán 2007; Rothman 2009; Camacho 2013). In Spanish, one of the primary functions of overt subjects is “to remove referential ambiguity when new referents are introduced into the discourse. Conversely, once a discourse referent has been established, it becomes pragmatically odd to use overt subject pronouns to refer to the same referent” (Rothman 2009, p. 954).

The notion of the null subject parameter (also known as the pro-drop parameter) is derived from The Principles and Parameters model of UG in which we find the extended projection principle (EPP), a condition on sentence formation indicating that all sentences must have a syntactic subject (Chomsky 1981). Languages with null subjects, like Spanish, satisfy the EPP by means of verbal agreement morphology that allows for the licensing (a condition on the syntactic representation) and identification (a condition on the interpretation) of a null pronoun as a subject (Rizzi 1986); for a review see (Barbosa 2011). In languages with a negative setting of the pro-drop parameter, like English, this principle must be satisfied by overt pronouns because they lack the appropriate type of verbal agreement morphology with pronominal features to satisfy the EPP requirement (Camacho 2013). Spanish identifies null subjects by recovering the person and number values encoded in its verbal morphology, while English must resort to a full pronoun instead. While there are many more extensive analyses of the pro-drop parameter, for the purposes of this paper, we will assume these to be the main differences between Spanish and English grammars regarding the licensing and identification of subjects.

2.2. Syntax–Pragmatics Interface

Pronominal subjects fall at the syntax–pragmatics interface, a proposal first put forward in acquisition literature by (Hulk and Müller 2000; Müller and Hulk 2001) regarding object drop to explain why cross-linguistic transfer seems to occur across some grammatical domains but not others. The suggestion is that cross-linguistic influence is likely to occur at a point in the linguistic system where the discourse-pragmatic context influences the possibilities of syntactic structure. Furthermore, cross-linguistic influence occurs when there is overlap at the surface level between two languages for a certain structure, even though the underlying syntactic analyses for this overlap structure are actually different in each language. When a bilingual child is presented with competing evidence for what the underlying representation for the overlap structure should be, he or she may take longer than a monolingual child to acquire that structure. Furthermore, the language with less options for a particular phenomenon influences the more complex language. This has been referred to as an interface delay in which bilinguals’ non target-like performance is due to the possibility that properties in the narrow syntax are acquired before those conditioned by the syntax–pragmatics interface (Sorace and Filiaci 2006; Rothman 2009).

These hypotheses were initially tested by researchers with young preschool children and were subsequently extended to older children by numerous other studies, providing evidence that as bilingual children get older, the use of syntactically correct but pragmatically inappropriate forms can be common (Serratrice 2007; Argyri and Sorace 2007; Sorace et al. 2009). Much of this evidence comes from the variability between null and overt subjects across different languages, which has proven to be fertile ground for testing hypotheses about the syntax–pragmatics interface. For a Spanish–English bilingual, the less complex syntactic properties of English may be more easily acquired and may influence the acquisition of those in Spanish, which are conditioned by the syntax–pragmatics interface. In what follows, we will provide a review of pronominal subject acquisition at the syntax–pragmatics interface in both monolingual and bilingual children learning an overt subject language together with a null subject language.

3. Early Acquisition of Subject Pronouns

3.1. Early Pronoun Acquisition in Monolingual Children

Studies in monolingual child language have long noted the existence of a missing subject stage, a period of omitted subjects in the acquisition of languages that require overt subjects, which converges with adult-like patterns at around age 3;5 (Hyams 1986; Orfitelli and Hyams 2008, 2012; Bloom 1990; Valian 1991; among others). The same stage also exists in pro-drop languages, but it has been observed that children begin to produce null and overt pronouns in pragmatically felicitous ways very early on, by age 3 (Grinstead 2000; Montrul 2004b; Serratrice 2005; Austin et al. 2017). This temporary period of missing subjects coincides with the gradual acquisition of the inflectional system (Grinstead 2000) and also co-occurs with root infinitives (Grinstead 2004; Orfitelli and Hyams 2008; Grinstead et al. 2009) and copula omission (Liceras et al. 2012). There is debate as to whether subject omission in monolingual child language is attributable to a difference between child and adult grammars (Hyams 1986; Hyams and Jaeggli 1988; Hyams and Wexler 1993; Rizzi 2005) or if it is the result of immature processing capabilities (Bloom 1990; Valian 1991), but here we will focus on the grammatical approach as the data of this study best support these accounts.

(Hyams 1986; Hyams and Jaeggli 1988; Hyams and Wexler 1993) all consider children of non-null-subject languages, like English, to have an incomplete grammar of their adult versions and therefore provide variants of a competence-deficit hypothesis for the null subject phenomenon2. (Hyams 1986, 2011) proposes that this phenomenon reflects an initial setting of the null subject parameter, as found in the Principles and Parameters model of UG. Infants begin with parameters that are preset at a universal value that is correct for some languages but not for others. As children mature, these parameters are set and reset at the appropriate values for their target language. Similarly, (Müller and Hulk 2001) point to the notion of a minimal default grammar, as originally posited by (Roeper 1999), as the initial setting in UG and the point of departure for L1 acquisition. They propose that certain properties are part of the universal, initial representation in the grammar of a child and that as children receive input from their specific language, they adapt to the syntactic rules associated with it. However, bilingual children confronted with conflicting input from two partially overlapping languages, may persist longer at a universal stage because they cannot map universal strategies onto language-specific rules as quickly as monolinguals.

3.2. Early Pronoun Acquisition in Bilingual Children

These developmental patterns have led researchers to investigate pronoun acquisition in bilingual children learning an overt-subject language like English together with a null-subject language such as Spanish (Paradis and Navarro 2003; Liceras et al. 2012; Austin et al. 2017), Italian (Serratrice 2006 2007; Sorace et al. 2009), Greek (Argyri and Sorace 2007), Hebrew (Hacohen and Schaeffer 2007), and Turkish (Haznedar 2010), all providing robust evidence for cross-linguistic transfer. (Sorace et al. 2009) propose that the language with the most economical syntax–pragmatics interface system (like English) is thought to influence the language with a more complex interface system (like Spanish) where null subjects are used alongside overt subjects, and where their distribution is regulated by subtle discourse-pragmatic constraints. Indeed, most studies have found this to be the case and the result is an overuse of overt pronouns in the null-subject language and the infelicitous application of the discourse-pragmatic principles guiding overt subject use (Paradis and Navarro 2003; Hacohen and Schaeffer 2007; Haznedar 2010). Data from comprehension and grammaticality judgment experiments also provide evidence that bilingual children tend to accept overt pronouns in the null-subject language in contexts in which monolinguals prefer a null subject, especially when they are dominant in the overt subject language (Argyri and Sorace 2007; Serratrice 2007; Sorace et al. 2009). In these studies, dominance may play a role because bilingual children who have greater exposure to English than their other null subject language experience a quantitative predominance of overt pronouns in the input.

According to (Liceras et al. 2012), who investigate the directionality of cross-linguistic influence, the transfer of null subjects from a null-subject language to an overt one is highly unlikely. This is because the overt language does not provide input that could be misanalyzed by a bilingual child as mirroring the structure of the null-subject language since in English, for example, null subjects with inflected verbs only occur in imperative clauses. Additionally, overt subjects are the key overlapping structure in both languages and, following the theories formulated in (Hulk and Müller 2000; Müller and Hulk 2001), this would predict that the more complex language (Spanish) would not influence the simpler one (English). However, the results of (Austin et al. 2017) indicate that it is in fact possible for there to be cross-linguistic influence from a null-subject language to an overt one, dependent upon sociolinguistic conditions and language dominance. In this study, the production data of bilingual English–Spanish preschool-aged children demonstrated target-like distribution of pragmatically appropriate null and overt subjects in Spanish, but a high rate of non-target null subjects in English. The researchers explain this phenomenon as transfer from the children’s dominant language, which was Spanish.

4. Input: Quality and Quantity

Keeping in mind the great variability that exists in heritage language grammars, input received from formal instruction, spoken and written, in the heritage language has been found to be a distinguishing factor in bilingual speakers with different proficiencies. (Montrol and Potowski 2007) investigated gender-marking and agreement in English–Spanish bilingual children aged 6 to 11 attending a dual immersion school in Chicago. They found that, though the heritage children performed differently to monolingual Spanish children, there was no evidence of language loss with increased age, suggesting that schooling in the heritage language enables both language acquisition and maintenance. (Kupisch and Pierantozzi 2010) also studied children aged 6 to 11 attending dual immersion schools, but in this case, they worked with heritage speakers of Italian living in Hamburg, Germany. Their findings echoed those of (Montrol and Potowski 2007), in which there was no decline in linguistic abilities with increased age, suggesting that schooling in the heritage language can prevent language loss. Both studies acknowledged that there is still more research to be done to understand the long-term effects (into adulthood) of immersion education.

Based on these findings, (Kupisch and Rothman 2016) propose three different dimensions in which schooling might explain differential outcomes amongst heritage speakers and possible improved performance in the heritage language. The first is that some properties of the standard variety of a language, like a more sophisticated register, are only taught through formal instruction at school, though they are not necessarily mastered after instruction even in the case of monolinguals living in monolingual societies. The second is having the heritage language not as the object of learning but rather as the medium of instruction because learners become familiarized with and learn how to handle scholarly instructions in this language. Finally, formal school settings provide significantly more opportunity to use the heritage language and its different registers more authentically with a greater variety of people, especially peers of the same age.

5. The Present Study

Considering the evidence that points to the differential acquisition of referential subjects in null-subject languages, that fall at the syntax–pragmatics interface in language contact situations, this study aims to contribute to the understanding of the role of input factors, specifically academic instruction, in the bilingual language development of heritage children. Studies have found that dual-immersion or ‘two-way’ immersion schools are conducive to both language acquisition and maintenance for bilingual heritage speakers who might otherwise experience attrition in their heritage language (Potowski 2007; Montrol and Potowski 2007; Kupisch and Rothman 2016). Therefore, we seek to discover how increased activation of the heritage language through immersion schooling may play a part in the development of the properties at the syntax–pragmatics interface, specifically null subject acceptability, in young heritage bilinguals.

We have specifically chosen to carry out this study with children aged four to seven because previous studies on null and overt subjects in bilingual acquisition have investigated younger children not yet in school (Paradis and Navarro 2003; Hacohen and Schaeffer 2007; Haznedar 2010) or older ages (Argyri and Sorace 2007; Sorace et al. 2009). This four to seven period is just after the null subject stage tapers off in monolingual children (Grinstead 2000; Orfitelli and Hyams 2008; Orfitelli and Hyams 2012) and while bilingual children between the ages of 6 and 10 have been found to perform at ceiling in English, regardless of language of dominance (Argyri and Sorace 2007; Sorace et al. 2009), it is unclear how null and overt subjects develop and progress between these two sets of ages in Spanish.

5.1. Research Questions

To evaluate the impact of instruction, we posit two research questions that guide this study. The first investigates to what extent increased levels of activation of two languages, in the form of immersion education, affect null and overt subject acceptance in +/− topic shift contexts. We hypothesize that immersion education should result in higher acceptability of null subjects in Spanish when compared to English monolingual education and should have no effect on acceptability in English. In an immersion school, children are exposed to a greater number and variety of native Spanish speakers and have more opportunity for uptake of the subtle pragmatic constraints governing null subjects in Spanish. Therefore, we expect that heritage children who attend a Spanish immersion school will perform more target-like in Spanish when compared to the heritage speakers who attend an English only school due to increased activation of the heritage language. We expect that, in English, the bilingual children should be as accurate as the monolinguals and that there will be no difference between the two groups, in line with previous studies (Argyri and Sorace 2007; Sorace et al. 2009).

The second research question asks whether heritage bilingual children experience cross-linguistic influence on null subject properties and if so, what the directionality is. We hypothesize that the overt subject language will have a greater influence over the null subject language (Liceras et al. 2012). We anticipate that the English school children will accept more overt subjects in Spanish than the immersion children due to cross-linguistic influence from English, but that both groups will accept more overt subjects than expected in a monolingual context. In English, we expect that both groups will perform on par with English monolingual peers, due to this being the dominant language of the society.

5.2. Participants

Four groups of children aged 4;0 to 7;6 participated in this research. The first was a group of heritage speakers (n = 21, mean age = 5;2) recruited at a Spanish immersion school in New Jersey who had attended the school for at least one academic year (immersion group). The second was a group of heritage speakers (n = 20, mean age = 5;5) who attended English monolingual preschools and elementary schools around New Jersey, recruited through personal contacts as well as through the immersion school’s after school classes and summer camps (non-immersion group). Finally, a group of monolingual English speakers (n = 17, mean age = 5;8) attending English monolingual schools in New Jersey was recruited through personal contacts (EM group) and a group of monolingually raised Spanish speakers (n = 18, mean age = 5;5) was recruited from a summer camp in Madrid, Spain (SM group)3. All subjects, and their parents, gave their informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board (protocol #17-632Mc).

The heritage speakers all had either one or two parents who spoke Spanish in the home and according to responses from parents on a language background questionnaire, had high exposure to Spanish in the form of books and movies at home, classes and camps, relationships with Spanish-speaking relatives, and travel to Spanish-speaking countries. All the heritage speakers were born in the United States or arrived before the age of two and were exposed to both languages before the age of three. It should be noted that some heritage speakers in the non-immersion group had been exposed to immersion environments throughout their lives either when traveling to visit relatives in the family’s home country or when attending a few weeks of Spanish camp over the summer. However, this was not considered to be the same as receiving full-time education in the heritage language. All the English monolingual children had little to no exposure to Spanish. Some children received 30 min per week of Spanish instruction at school, but had no functional competence in the language. All the monolingually raised Spanish children had received some English instruction in school from the age of three (approximately 1 h per day) but were raised in homes where only Spanish was spoken and attended Spanish schools. Two of the Spanish children had been exposed to English from birth through an English-speaking family member, but their main home language was Spanish.

For more details about parent responses on the language background questionnaire, see Table 1 below. The numbers in the table were calculated as percentages of the total responses so that, for example, in both bilingual groups, 100% of parents reported that Spanish maintenance was important and 93% reported that English was spoken with siblings. Parents were asked country of origin on the language background questionnaire so that children acquiring a Caribbean variety of Spanish were not included (specifically in this sample, these were children with parents from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic). Studies have found that these Spanish speakers tend to produce more overt pronouns than speakers of other dialects (Hochberg 1986; Camacho 2008). Care was also taken to ensure that the sample of children in the immersion school did not have teachers speaking Caribbean Spanish, rather these children had teachers from Peru and Uruguay. Children included in the study had parents from a variety of Spanish-speaking countries, primarily from Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. Eighteen additional heritage children were also tested but not included in the final sample due to parents citing very low Spanish exposure in the home and low proficiency scores, or exposure to a Caribbean variety of Spanish in the home.

Table 1.

Heritage children’s exposure to Spanish according to parent responses on the language background questionnaire.

The Spanish immersion school is located in New Jersey and offers programs for children aged 2;6 to first grade. The preschool programs for ages 2;6 to 4 are 100% immersion taught by a staff of native teachers of Spanish from Latin American countries. For children in pre-kindergarten through first grade, one hour of English literacy is provided every day by a native English teacher but all other subjects and activities, including recess and lunchtime, are led in Spanish. From our classroom observations, the children are consistently encouraged and reminded to interact in Spanish with their teachers and classmates but revert to English with their peers during playtime and spontaneous interactions. Roughly 50% of the students are heritage speakers of Spanish and the other 50% are children who come from English monolingual families.

5.3. Materials and Procedure

Children’s oral proficiency in each language, specifically morphosyntax, was assessed using the Bilingual English Spanish Assessment, BESA (Peña et al. 2014). The morphosyntax sections of the BESA were chosen knowing that in monolingual child language, development of overt pronouns coincides with acquisition of the inflectional system (Grinstead 2000). Parents were asked to complete a language background questionnaire for each child, which included information such as age of first exposure and current language use. For inclusion, children needed to obtain a minimum score of 50% on the BESA in both English and Spanish (see Table 2 for mean scores by group in both languages).

Table 2.

Bilingual English Spanish Assessment (BESA) proficiency scores out of 100 by group.

An offline acceptability judgment task was chosen for this study because such tasks have proven successful in assessing even very young children’s understanding of grammatical features i.e., (Orfitelli and Hyams 2012). Two versions of the task were created, one in Spanish and one in English, and both were delivered via a PowerPoint presentation presented on a 13-inch screen laptop. They were untimed. Of the bilingual children, half received the English task first and half the Spanish task first. The experimenter spoke to the participants in the language in which the experiment was being carried out. Monolinguals were administered the task in either English or Spanish only.

The structure of the acceptability judgment task, adapted from (Sorace et al. 2009), is as follows. It consisted of a series of short video clips showing four Disney character puppets (Mickey Mouse, Minnie Mouse, Donald Duck, and Goofy) with eight experimental items4 and four fillers5. In the experimental items, either Mickey or Goofy performed an action, which was commented upon either by himself ([−topic shift] (−TS) condition) or by the other character that had witnessed the action but was not involved in it ([+topic shift] (+TS) condition). There were four items in each condition. Then, the participants watched Minnie and Donald each say a subordinate clause one after the other. One character would begin the subordinate clause with a null subject and the other with an overt subject (he/él). The order in which the grammatical/ungrammatical sentences and felicitous/infelicitous sentences were presented by Minnie and Donald was counterbalanced throughout. Mickey and Goofy were selected as the characters performing the actions because they are of the same gender and, thus, the subject pronoun could refer ambiguously to either of them. The present perfect tense was used for the Spanish task though it is not the most widely used among Latin American and heritage speakers. However, this did not seem to have any effect on the children’s understanding of the phrases and experimental items. The following examples illustrate the types of sentences used in the Spanish task 3(a) and 3(b) and in the English task 3(c) and 3(d):

3.

- (a)

- −topic shift condition (−TS)Mickey criesMickey: ‘¡He llorado!’‘I have cried!’Minnie: Mickey dijo que ha llorado.‘Mickey said that (he) has cried’.Donald: #Mickey dijo que él ha llorado.#‘Mickey said that he has cried’.

- (b)

- +topic shift condition (+TS)Mickey eatsGoofy: ‘¡Mickey ha comido!’‘Mickey has eaten!’Minnie: #Goofy dijo que ha comido.#‘Goofy said that (he) has eaten’.Donald: Goofy dijo que él ha comido.‘Goofy said that he has eaten’.

- (c)

- −topic shift condition (−TS)Mickey jumpsMickey: ‘I jumped!’Minnie: *Mickey said that jumped.Donald: Mickey said that he jumped.

- (d)

- +topic shift condition (+TS)Goofy coughs.Mickey: ‘Goofy coughed!’Minnie: Mickey said that he coughed.Donald: *Mickey said that coughed.

After listening to the comments of all the characters, the children (who had been told that the characters were learning English or Spanish) were asked to decide which of the final two characters (Minnie Mouse or Donald) spoke ‘better’ English or Spanish. Their responses were audio recorded and coded for null and overt subject expression acceptability in –topic shift (−TS) conditions and +topic shift (+TS) conditions. See Appendix A for a list of experimental stimuli. The filler items had a similar structure to the experimental ones, but the characters in the second video uttered true or false statements rather than ungrammatical ones with the aim of checking that the participants had understood the task and were focusing on the sentences presented to them.

It is important to note the differences between the task in English and in Spanish. In English, children were asked to accept grammatical sentences with overt subjects or ungrammatical sentences with null subject pronouns, but in Spanish, children had to assess the context to choose pragmatically appropriate or inappropriate pronominal forms. To succeed in the English task, participants had to make choices based solely on their syntactic knowledge of English as a non-pro-drop language where null subjects are not allowed in subordinate clauses. However, in Spanish, children needed to integrate their syntactic knowledge of Spanish as a pro-drop language with their knowledge of the pragmatic constraints that guide the distribution of null and overt subject pronouns in topic shift or topic continuity circumstances (Sorace et al. 2009)6.

6. Results

The data were analyzed in R version 3.3.2 (R Development Core Team 2012) using generalized linear mixed effects models (GLMM) to examine personal pronoun use (null, overt) as a function of group (monolingual, immersion, non-immersion), topic (+/− topic shift), and age. Given the categorical nature of the participants’ responses (null, overt), the data were modeled using GLMMs with a binomial linking function. The predictors ‘group’ and topic were dummy coded with immersion participants and + topic shift set as the reference levels. Main effects and higher-order interactions were tested using nested model comparisons so as to be able to choose the most parsimonious model that adequately fit the data. Age was centered with the mean age (5;4) set at 0. The analyses for the English and the Spanish data are reported separately.

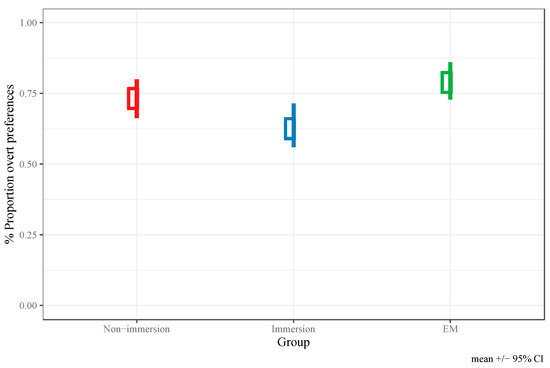

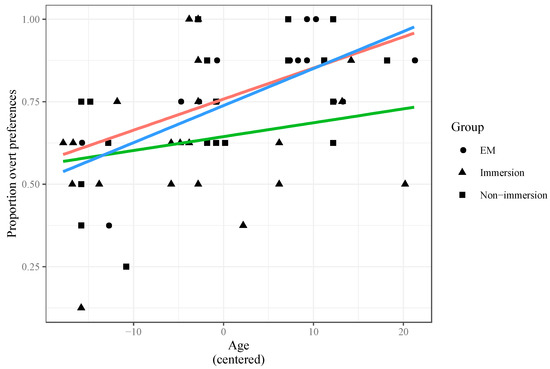

6.1. Pronominal Preferences in English

The analysis yielded a main effect of group (χ2(2) = 9.30, p < 0.02). The English monolingual (EM) group responded with an overt pronoun significantly more than the immersion group (β = 0.68; SE = 0.30; z = 2.25; p < 0.02). The non-immersion group performed similarly to the English monolinguals and responded with an overt pronoun significantly more than the immersion group (β = 0.57; SE = 0.28; z = 2.02; p < 0.04) (see Figure 1). There was no effect of topic in English (χ2(1) = 1.06, p = 0.30), but there was a main effect of age (χ2(1) = 11.36, p < 0.001). There were no higher-order interactions, but there was a trend towards a simple effect of age on the linear slope of the immersion group (β = 0.05; SE = 0.03; z = 1.75; p = 0.08), thus the model containing the interaction was retained. As seen in Figure 2, across all groups as children’s ages increased, they accepted more overt subjects in line with a more adult-like grammar. However, the effect of age was smaller for the immersion group. Table 3 shows the full model output.

Figure 1.

Proportion of overt pronoun responses in English as a function of group.

Figure 2.

Proportion of overt responses in English as a function of age (centered) and group.

Table 3.

Coefficients in English.

The responses to distractor items were checked to ensure that children were indeed paying attention to the task. In English, all three groups performed similarly. The immersion group had a mean score of 0.88 and SD = 0.33, and the non-immersion group had a mean score of 0.85, SD = 0.36. The EM group had a mean score of 0.90, SD = 0.29.

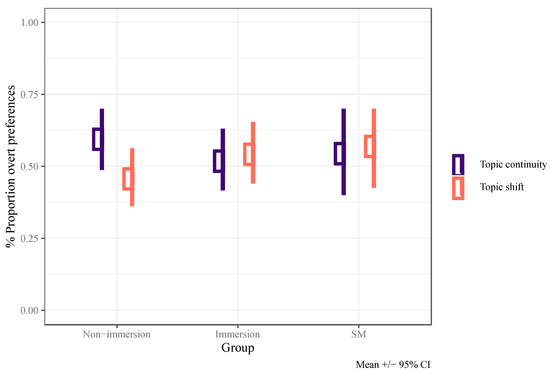

6.2. Pronominal Preferences in Spanish

The same GLMM was used for the Spanish responses of both bilingual groups and the SM group. The predictors ‘group’ and topic were dummy coded with immersion participants and + topic shift set as the reference levels. Main effects and higher-order interactions were tested using nested model comparisons. Age was centered with the mean age (5;4) set at 0. Figure 3 reports the mean of overt and null pronoun choices in Spanish. To recall, in topic shift conditions, expected responses were overt subjects and in topic continuity conditions, expected responses were null subjects. All three groups of children performed at chance level and there was no effect of group (χ2(2) = 0.22, p = 0.89), no effect of topic (χ2(1) = 0.63, p = 0.42), and no effect of age (χ2(1) = 0.90, p = 0.34). Again, responses to distractor items were checked in Spanish to ensure that children were indeed paying attention to the task. The immersion group mean score was 0.83 and SD = 0.38, the non-immersion group had a mean score of 0.83, SD = 0.38, and the SM group had a mean score of 0.92, SD = 0.28. Table 4 reports the full model output.

Figure 3.

Proportion of overt pronoun responses in Spanish in topic shift and topic continuity conditions.

Table 4.

Coefficients in Spanish.

6.3. Comparison of Spanish and English

Table 5 reports the mean expected responses by group and language (pragmatically felicitous in Spanish and grammatically correct in English).

Table 5.

Total of mean expected responses by group.

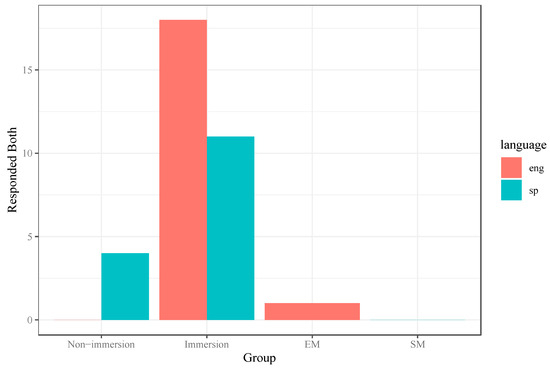

Interestingly, seven children in the immersion group responded by asserting that both the null and overt options presented to them sounded the same so that neither Disney character had ‘said it better’ regardless of having been asked to choose one character. There were 18 instances of this in English and 11 in Spanish (see Figure 4). While it occurred one time in the EM group (by one child) and four times in the non-immersion group (by one child), it was minimal in comparison to the immersion group. It never occurred in the SM group. These responses seem, at least anecdotally, to indicate that increased quantity and quality of input in the heritage language has an effect on the comprehension strategies of bilingual children in both of their languages.

Figure 4.

Number of times that children responded that both null and overt sounded correct.

Additionally, some bilingual children in both groups were asked to explain why the character they chose had ‘said it better,’ in both English in Spanish. Most were unable to explain their reasoning, most likely due to their young age since studies have shown that the ability to make explicit metalinguistic judgments may develop later in childhood (i.e., Cairns et al. 2006). However, seven children aged 6 and older in both groups were able to correctly explain their choices, but only in English, indicating that they had chosen the overt subject option because it sounded wrong to say the sentences in English without the pronoun. This demonstrates a level of metalinguistic awareness in the dominant language that, as yet, children could not express in the heritage language. This distinction between languages in ability to express metalinguistic awareness may not only be attributable to language dominance, but also to the more subtle pragmatic differences in the options presented in the Spanish task versus the more salient ungrammaticality of the task utterances in English. In the SM group, only one child aged seven was able to explain his choices and accurately describe the pragmatic use of the overt pronoun in the task in Spanish, while all the younger children aged four to six were unable to do so.

7. Discussion

In this study, four groups of children (English monolingual, monolingually raised Spanish, heritage bilingual attending a Spanish immersion school, and heritage bilingual children attending an English monolingual school) completed an acceptability judgment task to assess their understanding of null subjects in both English, the dominant societal language, and Spanish, the heritage language. The findings revealed that the bilingual children in the immersion school accepted significantly more ungrammatical null subjects in English than the other groups, but that there were no differences in Spanish between the heritage groups or as compared to monolingually raised Spanish speakers who all performed at chance level. Additionally, in English, as children’s ages increased so did their acceptance of overt subjects in English, but for the immersion group, the effect of age was smaller. These results establish an effect of increased input and activation in the form of immersion education on the English of heritage children, but not their Spanish, and are the first of this kind in child acquisition literature.

The findings raise a number of important questions about the original hypotheses of the study and more generally about the developmental and environmental mechanisms that might be responsible for the patterns observed. Some aspects of the results, in particular, have potential implications for theories of bilingual development and models of bilingual education.

Contrary to the predictions that would have supported hypothesis 1, immersion schooling had no significant effect on the acceptability of null subjects in Spanish, but it did have a significant effect on the children’s responses in English. While there was no difference in Spanish between the bilingual groups or between the non-immersion group and the monolingual group, the immersion group accepted ungrammatical null subjects at a rate of 37% in English as compared to the monolingual group who accepted null subjects at a rate of 21%. Therefore, the prediction that English-dominant bilinguals would behave on par with English monolinguals was not borne out in the group of children attending the Spanish immersion school. Additionally, the data presented do not support our prediction for hypothesis 2 regarding the directionality of cross-linguistic effects from English to Spanish because in Spanish, both groups of bilingual children behaved just as their monolingually raised counterparts by accepting a roughly equal amount of null and overt subjects regardless of the pragmatic context of topic shift or topic continuity.

In Spanish, the overall pattern of results gives us the opportunity to re-evaluate previous studies on production. While Spanish monolingual (Grinstead 2000) and Spanish-dominant children (Austin et al. 2017) seem to produce null and overt subjects in target-like ways by age five, the data presented here suggest that, in comprehension, the discourse conditions governing the distribution of subject pronouns may be acquired later as has also been shown in previous studies of judgments from Spanish-speaking monolingual children in Mexico (Shin and Cairns 2012). All the groups of children accepted an almost equal amount of null and overt subjects in both (−TS) and (+TS) conditions, indicating their understanding that both are grammatical, possible, and viable, but their uncertainty as to the pragmatic conditions under which they may be used. It could be argued that this performance at chance level could be due to task effects, but one must keep in mind that in English, all the children performed well above chance level and in Spanish, the seven-year-old (and oldest child) in the SM group was able to accurately describe the use of overt pronouns in the task. Thus, in Spanish, the bilingual children’s comprehension of null and overt subjects is developing at the same pace as those raised monolingually in Spanish. In English, the pattern of results suggests that though the bilingual children in the immersion school accept more null subjects than their monolingual peers, they exhibit a tendency towards an overt subject grammar. They show a preference for overt pronouns in English that is not revealed in their Spanish. Therefore, in contrast to the literature from production data (Paradis and Navarro 2003; Haznedar 2010) and comprehension data (Argyri and Sorace 2007; Serratrice 2007; Sorace et al. 2009), the results of this study do not provide evidence of cross-linguistic influence from the overt subject language into the null subject language in this age range.

This leads to the question of directionality of cross-linguistic effects. Despite English being the dominant societal language and the dominant language of the children tested, the bilingual children in the Spanish immersion school did not show evidence of cross-linguistic influence from English to Spanish. If this were the case, one would have expected an over-acceptance of overt pronouns in Spanish, but this was not so. Rather, to the contrary, the children accepted a higher amount of non-target-like null pronouns in English. These findings can be contrasted with those of (Austin et al. 2017) in which children dominant in Spanish and in the process of acquiring English as a second language overproduced non-target-like null pronouns in English. While the results of the previous study can be explained as evidence of cross-linguistic influence from Spanish, the dominant language, to English, the current study shows a subset of English dominant bilingual children who behave in a similar way.

Given that the children were English dominant, this finding is better explained as a prolonging of the null subject stage due to bilingual input, as posited by (Müller and Hulk 2001), rather than ascribing it to cross-linguistic influence from Spanish. The data support the theories put forth by (Hyams 1986) as well as (Hyams and Jaeggli 1988; Hyams and Wexler 1993) that children of non-null subject languages, like English, have a grammar that diverges from their adult versions. The null subject stage, in which overt subjects take time to appear and are then used inconsistently, reflects an initial setting or universal value of the null subject parameter. The optionality observed during this stage can be expressed as flexibility in licensing null subjects in child grammar that later becomes more rigid in adult grammars. Though various studies have found that the directionality of influence goes from the overt subject language to the null subject language, regardless of language dominance for a review, see (Sorace and Serratrice 2009), and that (Liceras et al. 2012) proposed it would be very unlikely for a null subject language to influence an overt subject language because overt subjects are the key overlapping structure, it is very possible that for the children in the immersion school with greater activation of Spanish, cross-linguistic effects from English are not yet visible at the ages tested in this study.

The age group in this study, four to seven, was specifically chosen because previous studies on null and overt subject acquisition in bilingual children have investigated younger ages (Paradis and Navarro 2003; Hacohen and Schaeffer 2007; Haznedar 2010) or older ages (Argyri and Sorace 2007; Sorace et al. 2009). While the findings of (Argyri and Sorace 2007; Sorace et al. 2009) show that bilingual children between the ages of 6 and 10 perform at ceiling in English, regardless of language of dominance, the results of this study demonstrate that the range between four and seven is a transition period for bilingual children. It is the period just after the null subject stage tapers off in monolingual children, but we can see that for those with increased activation of both languages through immersion education, this is a variable timeframe. Both bilingual groups showed a correlation between increasing age and overt subject acceptance in English during this period, though the effect of age was slightly smaller for the children in the immersion school. It is also important to note that in monolingual acquisition, children’s grammars converge with adult-like grammars between ages three and four with the appearance of verbal morphology (Orfitelli and Hyams 2008). However, by the time of this study, the children had acquired verbal morphology and were no longer in the root infinitive stage as determined by the administered morphological proficiency test (there was an overall mean score across all groups of 89.09 in English). Therefore, the age range of four to seven provides an intriguing window into this transition period for bilingual children when they have acquired verbal morphology but appear to continue to accept null subjects in English.

Finally, the primary aim of this study was to explore the role of input of the heritage language, in the form of academic instruction. The results from the children attending a Spanish immersion school, provide us with some interesting insights into how increased quality and quantity of the heritage language can influence the development of both the dominant and heritage language. Children in a language immersion school find themselves spending much more time in their bilingual mode (Grosjean 1998), in which both of their languages and language processing mechanisms are activated in the same environment because they interact with their teachers in Spanish, but with their peers primarily in English. The bilingual children attending an English monolingual school spend the majority of their time in either two monolingual modes (English at school and Spanish at home) or a primarily monolingual mode, at school, and a bilingual mode at home. Thus, they are also exposed to a greater amount of input in English than those in a Spanish immersion school. This phenomenon leads to a language development that is much more similar to the English monolingual children, as can be seen in the similarity of results between these two groups in the English task and in the similarity of their correlation between age and overt subject acceptance in English.

Additionally, as in the model of (Putnam and Sánchez 2013), intake is essential to explain what is acquired. They define intake as the operation the mind participates in while interpreting, extracting, and storing language features, which serve as the fundamental building blocks of grammar. Immersion academic instruction leads to heightened levels of both activation and intake of two languages in the same environment, which may be the contributing factor to the extended null subject stage in English visible in the results of this study. In bilingual children who are confronted with input from two partially overlapping languages like English, in which only overt subjects are allowed, and Spanish, where both null and overt subjects are viable, this early universal stage appears to persist longer and is amplified by immersion schooling. Furthermore, the anecdotal results of the repeated responses that “both [the overt and null options] sound the same” provide more evidence that immersion education plays a part in the development of children’s comprehension strategies in both of their languages. One explanation could be that these children, faced with ongoing conflicting input from two languages both at home and at school, still have not categorized the grammatical constraints of the overt subject in each language. For these children, both null and overt subjects are viable in the Spanish input they receive, as evidenced from their acceptability results in Spanish, but they still have not determined the pragmatic constraints that guide their use. Therefore, in this age range, both options are possible in both (−TS) and (+TS) conditions. If null and overt subjects are acceptable in both discourse-pragmatic conditions, then, at least some children, do not yet distinguish between the null and the overt pronoun and they sound the same.

Limitations

It is important to acknowledge that this study inherently faces some limitations. Firstly, a number of the older children in the English task were able to provide a metalinguistic explanation for their adult-like judgments, but in the Spanish task this was not so (with the exception of one child aged seven in the Spanish-dominant group). Thus, it is not possible to know if their judgments were based solely on the felicitous use of the null or overt subject, or if other factors, such as intonation, accent, or variety of Spanish, may have come into play as they were asked to decide which character spoke better Spanish. Additionally, while parents completed a detailed language background questionnaire about the children’s historical and daily language use, not enough could be known about the children’s input in terms of null and overt subjects. It may very well be that the bilingual children received more ungrammatical null subjects in their English input due to having bilingual parents and parents with English as a second language since previous studies have found that these populations (native speakers of a null subject language under attrition and second language speakers) tend to produce more pragmatically inappropriate pronouns than monolinguals (Paradis and Navarro 2003; for a review, see Sorace and Serratrice 2009). It is therefore reasonable to assume that children of parents who are themselves bilingual, and children who have bilingual teachers in an immersion school, may experience input that is not exactly comparable with the input received by monolingual peers in the same country. Finally, some differences in heritage language exposure, as noted on the language background questionnaires, existed between the immersion and non-immersion groups that may account for their similar performance on the Spanish task. Seventy-one percent of children in the immersion school had only one Spanish speaking parent, as compared to 55% of the non-immersion children. Twenty-four percent of parents in the immersion group reported having traveled to Spanish speaking countries, compared to 80% in the non-immersion group. It is possible that this greater exposure to Spanish in the non-immersion group may compensate for the amount and quality of Spanish the immersion group is exposed to in the academic context, particularly for those children who had only been in the program for one year.

8. Conclusions

The findings presented here shed new light on the comprehension of pronominal subjects in the bilingual acquisition of English and Spanish. This study sought to investigate the role of immersion education on the development of null subject comprehension in heritage speakers of Spanish living in the United States and found that indeed this environment has an effect. Because of language dominance, the results of the bilingual children’s English can be better explained as a prolonging of the null subject stage due to bilingual input and increased activation, rather than as evidence of cross-linguistic effects from Spanish. This knowledge has implications for bilingual education and mainstream monolingual education for bilingual children. In monolingual schools, simultaneous bilingual children perform on par in English with their monolingual peers and the second language bears no effect on their English language development. However, in the early stages of bilingualism in an immersion school, school teachers should be aware of differences that may exist not only in the grammar of the heritage language, but also in the dominant language. One can presume, based on evidence from the literature (Sorace et al. 2009) and the correlation found here between age and overt subject acceptance, that later in childhood these English dominant bilinguals will converge with English monolinguals in their acceptability of null subjects in English, but this age range is outside the scope of this study and should be investigated in future research. This study provides evidence that bilingual children follow a different path of acquisition, but it is crucial to highlight that immersion education is not detrimental to the development of the majority language and, in fact, much research demonstrates that these programs lead to superior performance on academic measures in the long run (Serafini et al. 2020). The results of this study, rather, add to our understanding of the directionality of cross linguistic influence and effect of input on both the dominant and non-dominant languages of heritage speakers.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the Spanish immersion school in New Jersey for their kindness, enthusiasm and willingness to help with this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Spanish stimuli:

−topic shift condition (−TS)

- Mickey criesMickey: ‘¡He llorado!’‘I have cried!’Minnie: Mickey dijo que ha llorado.‘Mickey said that (he) has cried’.Donald: Mickey dijo que él ha llorado.‘Mickey said that he has cried’.

- Mickey laughs.Mickey: ‘¡He reído!’‘I have laughed!’Minnie: Mickey dijo que él ha reído.‘Mickey said that he has laughed’.Donald: Mickey dijo que ha reído.‘Mickey said that (he) has laughed’.

- Goofy falls.Goofy: ‘¡Me he caído!’‘I have fallen!’Minnie: Goofy dijo que se ha caído.‘Goofy said that (he) has fallen’.Donald: Goofy dijo que él se ha caído.‘Goofy said that he has fallen’.

- Goofy jumps.Goofy: ‘¡He saltado!’‘I have jumped!’Minnie: Goofy dijo que ha saltado.‘Goofy said that (he) has jumped’.Donald: Goofy dijo que él ha saltado.‘Goofy said that he has jumped’.

+topic shift condition (+TS)

- Mickey eatsGoofy: ‘¡Mickey ha comido!’‘Mickey has eaten!’Minnie: Goofy dijo que ha comido.‘Goofy said that (he) has eaten’.Donald: Goofy dijo que él ha comido.‘Goofy said that he has eaten’.

- Goofy coughsMickey: ‘¡Goofy ha tosido!’‘Goofy has coughed!’Minnie: Mickey dijo que él ha tosido.‘Mickey said that he has coughed’.Donald: Mickey dijo que ha tosido.‘Mickey said that (he) has coughed’.

- Goofy singsMickey: ‘¡Goofy ha cantado!’‘Goofy has sung!’Minnie: Mickey dijo que ha cantado.‘Mickey said that (he) has sung’.Donald: Mickey dijo que él ha cantado.‘Mickey said that he has sung’.

- Mickey sneezes.Goofy: ‘¡Mickey ha estornudado!’‘Mickey has sneezed!’Minnie: Goofy dijo que él ha estornudado.‘Goofy said that he has sneezed’.Donald: Goofy dijo que ha estornudado.‘Goofy said that (he) has sneezed’.

Distractor items:

- Goofy: ¡Que flores más lindas hay aquí!What pretty flowers are here!Minnie: Goofy dijo que flores más lindas.Goofy said what pretty flowers.Donald: Goofy dijo que flores más feas.Goofy said what ugly flowers.

- Goofy: ¡Aquí hace mucho calor!It’s hot here!Minnie: Goofy dijo que hace mucho frío.Goofy said that it’s very cold.Donald: Goofy dijo que hace mucho calor.Goofy said that it’s very hot.

- Mickey: ¡My color favorito es el azul!My favorite color is blue!Minnie: Mickey dijo que su color favorito es el azul.Mickey said that his favorite color is blue.Donald: Mickey dijo que su color favorito es el rojo.Mickey said that his favorite color is red.

- Mickey: ¡Cómo me gusta comer pastel!How I love eating cake!Minnie: Mickey dijo que le gusta comer broccoli.Mickey said that he likes eating broccoli.Donald: Mickey dijo que le gusta comer pastel.Mickey said that he likes eating cake.

English stimuli:

−topic shift condition (−TS)

- Mickey jumpsMickey: ‘I jumped!’Minnie: Mickey said that jumped.Donald: Mickey said that he jumped.

- Mickey laughs.Mickey: ‘I laughed!’Minnie: Mickey said that laughed.Donald: Mickey said that he laughed.

- Goofy falls.Goofy: ‘I fell!’Minnie: Goofy said that he fell.Donald: Goofy said that fell.

- Goofy cries.Goofy: ‘I cried!’Minnie: Goofy said that he cried.Donald: Goofy said that cried.

+topic shift condition (+TS)

- Goofy coughs.Mickey: ‘Goofy coughed!’Minnie: Mickey said that he coughed.Donald: Mickey said that coughed.

- Goofy sings.Mickey: ‘Goofy sang!’Minnie: Mickey said that sang.Donald: Mickey said that he sang.

- Mickey sneezes.Goofy: ‘Mickey sneezed!’Minnie: Goofy said that he sneezed.Donald: Goofy said that sneezed.

- Mickey eatsGoofy: ‘Mickey ate!’Minnie: Goofy said that ate.Donald: Goofy said that he ate.

Distractor items:

- 5.

- Goofy: There are such pretty flowers here!Minnie: Goofy said there are pretty flowers here.Donald: Goofy said there are ugly flowers here.

- 6.

- Goofy: It’s hot here!Minnie: Goofy said that it’s cold here.Donald: Goofy said that it’s hot here.

- 7.

- Mickey: My favorite color is blue!Minnie: Mickey said that his favorite color is blue.Donald: Mickey said that his favorite color is red.

- 8.

- Mickey: I love eating cake!Minnie: Mickey said that he loves eating broccoli.Donald: Mickey said that he loves eating cake.

References

- Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 1998. Parametrizing AGR: Word order, V-movement and EPP-checking. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 16: 491–539. [Google Scholar]

- Argyri, Efrosyni, and Antonella Sorace. 2007. Crosslinguistic influence and language dominance in older bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition 10: 79. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, Jennifer, Liliana Sánchez, and Silvia Pérez-Cortes. 2017. Null subjects in the early acquisition of English by child heritage speakers of Spanish. In Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 11. Edited by Silvia Perpiñán, David Heap, Itziri Moreno-Villamar and Adriana Soto-Corominas. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 209–27. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, Pilar. 2011. Pro-drop and theories of pro in the minimalist program part 1: Consistent null subject languages and the pronominal-agr hypothesis. Language & Linguistics Compass 5: 551–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Paul. 1990. Subjectless sentences in child language. Linguistic Inquiry 21: 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, Helen, Gloria Schlisselberg, Dava Waltzman, and Dana McDaniel. 2006. Development of metalinguistic skill: Judging the grammaticality of sentences. Communication Disorders Quarterly 27: 213–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, José. 2008. Syntactic Variation: The Case of Spanish and Portuguese Subjects. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics 1: 415–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, José. 2013. Null Subjects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Ferrán, Nydia. 2007. A Bend in the Road: Subject Personal Pronoun Expression in Spanish after 30 Years of Sociolinguistic Research. Language and Linguistics Compass 1–6: 624–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascarelli, Mara. 2007. Subjects, Topics and the Interpretation of Referential Pro: An Interface Approach to the Linking of (Null) Pronouns. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 4: 691. [Google Scholar]

- Gathercole, Virginia. 2016. Factors Moderating Proficiency in Bilingual Speakers. In Bilingualism across the Lifespan: Factors Moderating Language Proficiency. Edited by E. Nicoladis and S. Montanari. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee, Fred, Elena Nicoladis, and Johanne Paradis. 1995. Language differentiation in early bilingual development. Journal of Child Language 22: 611–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, John. 2000. Case, inflection and subject licensing in child Catalan and Spanish. Journal of Child Language 27: 119–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, John. 2004. Subjects and interface delay in child Spanish and Catalan. Language 80: 40–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstead, John, Juliana De la Mora, Mariana Vega-Mendoza, and Blanca Flores. 2009. An Elicited Production Test of the Optional Infinitive Stage in Child Spanish. In Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition North America (GALANA 2008). Edited by Jean Crawford, Koichi Otaki and Masahiko Takahashi. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 1998. Studying bilinguals: Methodological and conceptual issues. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 1: 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacohen, Aviya, and Jeannette Schaeffer. 2007. Subject Realization in Early Hebrew/English Bilingual Acquisition: The Role of Crosslinguistic Influence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 10: 333–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haznedar, Belma. 2010. Transfer at the syntax–pragmatics interface: Pronominal subjects in bilingual Turkish. Second Language Research 26: 355–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, Judith. 1986. Functional compensation for /-s/ deletion in Puerto Rican Spanish. Language 62: 609–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulk, Aafke, and Nastascha Müller. 2000. Bilingual first language acquisition at the interface between syntax and pragmatics. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyams, Nina. 1986. Language Acquisition and the Theory of Parameters. Dordrecht: Reidel. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, Nina. 2011. Missing Subjects in Early Child Language. In Handbook of Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition. Edited by Jill de Villiers and Thomas Roeper. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 13–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, Nina, and Osvaldo Jaeggli. 1988. Morphological uniformity and the setting of the null subject parameter. Northeastern Linguistic Society 18: 238–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, Nina, and Kenneth Wexler. 1993. The grammatical basis of null subjects in child language. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 421–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, Nina, Victoria Mateu, Robyn Orfitelli, Michael Putnam, Jason Rothman, and Liliana Sánchez. 2014. Parameter Theory in Language Acquisition and Change: An Overview. In Contemporary Linguistic Parameters. Edited by Antonio Fábregas, Jaume Mateu and Michael Putnam. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Cristina Pierantozzi. 2010. Interpreting definite plural subjects: A comparison of German and Italian monolingual and bilingual children. In Proceedings of the 34th BUCLD. Edited by K. Franich, K. M. Iserman and L. L. Keil. Boston: Cascadilla Press, pp. 245–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Jason Rothman. 2016. Terminology matters! Why difference is not incompleteness and how early child bilinguals are heritage speakers. International Journal of Bilingualism 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2008. Feature-assembly in second language acquisition. In The Role of Features in Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Juana Liceras, Helmut Zobl and Helen Goodluck. Mahway: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 106–40. [Google Scholar]

- Liceras, Juana, Raquel Fernández Fuertes, and Anahí Alba de la Fuente. 2012. Overt subjects and copula omission in the Spanish and the English grammar of English–Spanish bilinguals: On the locus and directionality of interlinguistic influence. First Language 32: 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbers, Margaret Quesada, and Sarah Blackwell. 2009. The L2 Acquisition of null and overt Spanish subject pronouns: A pragmatic approach. In Selected Proceedings of the 11th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Edited by Joseph Collentine, Maryellen García, Barbara Lafford and Francisco Marcos Marín. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 117–30. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel, Jürgen M. 1989. Early differentiation of languages in bilingual children. In Bilingualism across the Life Span: Aspects of Acquisition, Maturity, and Loss. Edited by Kenneth Hyltenstam and Lorraine Obler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Montalbetti, Mario. 1984. After Binding. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Montrol, Silvina, and Kim Potowski. 2007. Command of gender agreement in school-age Spanish-English Bilingual Children. International Journal of Bilingualism 11: 301–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2004a. Subject and object expression in Spanish heritage speakers: A case of morphosyntactic convergence. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 125–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2004b. The Acquisition of Spanish: Morphosyntactic Development in Monolingual and Bilingual L1 Acquisition and Adult L2 Acquisition. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Natascha, and Aafke Hulk. 2001. Crosslinguistic Influence in bilingual acquisition: Italian and French as recipient languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 4: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfitelli, Robyn, and Nina Hyams. 2008. An experimental study of children’s comprehension of null subjects: Implications for grammatical/performance accounts. In BUCLD 32 Proceedings. Edited by Harvey Chan, Heather Jacob and Enkeleida Kapia. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 335–46. [Google Scholar]

- Orfitelli, Robyn, and Nina Hyams. 2012. Children’s Grammar of Null Subjects: Evidence from Comprehension. Linguistic Inquiry 43: 563–590. [Google Scholar]

- Paradis, Johanne. 2011. The impact of input factors on bilingual development. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 1: 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne, and Samuel Navarro. 2003. Subject realization and crosslinguistic interference in the bilingual acquisition of Spanish and English: What is the role of input? Journal of Child Language 30: 371–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, Elizabeth, Vera Gutierrez-Clellen, Aquiles Iglesias, Brian Goldstein, and Lisa Bedore. 2014. Bilingual English Spanish Assessment (BESA). San Rafael: AR Clinical Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, Acrisio, and Jason Rothman. 2009. Disentangling sources of incomplete acquisition: An explanation for competence divergence across heritage grammars. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 211–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, Maria. 2007. Heritage languages: In the “wild” and in the classroom. Language and Linguistics Compass 1: 368–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potowski, Kim. 2007. Characteristics of the Spanish grammar and sociolinguistic proficiency of dual immersion graduates. Spanish in Context 4: 187–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Michael, and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. What’s so incomplete about incomplete acquisition?—A prolegomenon to modeling heritage language grammars. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 3: 378–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team. 2012. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 1 January 2017).

- RAE, and ASALE. 2009. Nueva Gramática de la Lengua Española. Morfología y Sintaxis. Madrid: Espasa. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1986. Null objects in Italian and the theory of pro. Linguistic Inquiry 17: 501–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 2005. On the Grammatical Basis of Language Development: A Case Study. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 70–109. [Google Scholar]

- Roeper, Thomas. 1999. Universal bilingualism. Bilingualism, Language and Cognition 2: 169–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, Jason. 2009. Pragmatic deficits with syntactic consequences? L2 pronominal subjects and the syntax–pragmatics interface. Journal of Pragmatics 41: 951–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, Ellen, Nadine Rozell, and Adam Winsler. 2020. Academic and English language outcomes for DLLs as a function of school bilingual education model: The role of two-way immersion and home language support. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, Ludovica. 2005. The role of discourse pragmatics in the acquisition of subjects in Italian. Applied Psycholinguistics 26: 437–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, Ludovica. 2006. Referential cohesion in the narratives of bilingual English-Italian children and monolingual peers. Journal of Pragmatics 39: 1058–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serratrice, Ludovica. 2007. Cross-Linguistic Influence in the Interpretation of Anaphoric and Cataphoric Pronouns in English-Italian Bilingual Children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 10: 225–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Naomi, and Helen Cairns. 2012. The development of NP selection in school-age children: Reference and Spanish subject pronouns. Language Acquisition 19: 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella. 2004. Native language attrition and developmental instability at the syntax-discourse interface: Data, interpretations and Methods. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 7: 143–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Francesca Filiaci. 2006. Anaphora resolution in near-native speakers of Italian. Second Language Research 22: 339–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, and Ludovica Serratrice. 2009. Internal and external interfaces in bilingual language development: Beyond structural overlap. International Journal of Bilingualism 13: 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorace, Antonella, Ludovica Serratrice, Francesca Filiaci, and Michela Baldo. 2009. Discourse conditions on subject pronoun realization: Testing the linguistic intuitions of older bilingual children. Lingua 119: 460–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Guadalupe. 2000. Spanish for Native Speakers: AATSP Professional Development Series Handbook for Teachers K-16. New York: Harcourt College, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Valian, Virginia. 1991. Syntactic subjects in the early speech of American and Italian children. Cognition 40: 21–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Lisa, Nora Hellmold, Hyoun-A. Joo, Michael T. Putnam, Eleonora Rossi, Catherine Stafford, and Jospeh Salmons. 2015. New Structural Patterns in Moribund Grammar: Case Marking in Heritage German. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Other researchers have identified more detailed constraints. For instance, the overt pronoun constraint (OPC) (Montalbetti 1984) provides an account for the distribution of null and overt pronouns in subject position in null-subject languages. Additionally, (Lubbers and Blackwell 2009) outline a series of pragmatic rules associated with both null and overt subject pronouns in Spanish including salient referents, epistemic parentheticals, switch focus, contrastive focus, and pragmatic weight. For a review of other constraints, see (Flores-Ferrán 2007). |

| 2 | As an alternative, (Rizzi 2005) proposed yet another parameter model, different to the parameters referred to by (Hyams 1986, 2011), to account for the null subject stage called the root null subject parameter (RNS). The RNS parameter specifies that, in overt-subject languages, a subject may be null in the specifier of the root. According to (Hyams et al. 2014, p. 355), the RNS “assumes children’s grammars set an initial null-subject setting under pressure from a computational strategy favoring parametric values that reduce the load on the production system (null subjects are computationally less costly than overt subjects, by hypothesis).” |

| 3 | Other than Caribbean Spanish (Hochberg 1986; Camacho 2008), no significant differences have been shown to exist between varieties of Spanish in terms of the discourse pragmatic constraints that guide null and overt subject use for a review, see (Flores-Ferrán 2007). Therefore, the Spanish speakers from Spain seemed a suitable comparison group. |

| 4 | There were no trial items. To account for this, no item effects were found during the statistical analysis and accuracy on the filler items (which tested true/false understanding) was high in both languages as noted in Section 6. |

| 5 | The inclusion of only four filler items was made so that the task would not become too long for the children who were quite young. For this same reason, subject position was not tested or included as a variable in the experimental items. This would have increased the number of items and extended the study time for the children. |

| 6 | In Spanish, intonation and stress were not accounted for in the recordings, which was brought to the attention of the researcher later on. Emphasis on the overt pronoun could have led to a bias of over-acceptance of the overt subjects, but this was not the case as will be discussed further in Section 6 and Section 7. Therefore, intonation and stress did not seem to bias the results. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).