Abstract

This paper examines the interplay of phonological, morphological, and lexical variation focusing on adjectives in Japanese dialects. Previous studies of adjectives in the Niigata dialects of the Japanese language analyzed the ongoing changes in dialectal variation amongst the young generation of Japanese. In this paper, the data derived from the geolinguistic survey and dialect dictionaries are used to verify the estimated changes in phonological, morphological, and lexical variation. The variation of adjectives is examined by classifying forms with regard to the distinction between standard/dialectal forms. The phonological types of adjectives played a role in the interpretation of the phonological variation and change. Most changes of phonological types are phonologically explained but include change by analogy. The lexical variation is intertwined with phonological variation and morphological variation. The morphological distributions which vary according to the conjugation form are one example of lexical diffusion.

1. Introduction

The geolinguistic approach is useful to examine the variation and change of areal dialects. Linguistic maps or dialect maps are “visualizations of linguistic features or, more generally, of feature-based areal structures” (Rabanus 2018, p. 348). The typical linguistic map tends to visualize “single” linguistic features such as sounds, forms, and words of a language, but linguistic features do not exist separately but are intertwined. This paper aims to examine the interplay of phonological, morphological, and lexical variation of adjectives in Japanese dialects.

The Niigata dialects of the Japanese language are located on the border of eastern and western dialects. Fukushima (2006) analyzed the variation of adjectives in the Niigata dialects with the focus on lexical variation, and Fukushima (2018a) with the focus on phonological variation. Both analyzed the ongoing changes happening in dialectal variation of the young generation. In this paper, the data derived from the geolinguistic survey and dialect dictionaries are used to verify the estimated course of change.

2. Materials and Methods

The data for this paper are collected by the geolinguistic survey and the dialect dictionaries.

The first group of data includes the CS (College Students) data of the young generation, 180 female college students in Niigata, which was surveyed by the author in 2005 and 2006. All subjects in the CS survey gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Niigata Prefecture (No. 1624). Additional data are collected from nationwide linguistic atlases, specifically Grammar Atlas of Japanese Dialects (National Language Research Institute 1989–2006) and New Linguistic Atlas of Japan (Onishi 2016) (based on the survey of FPJD: the collaborative research project “Field-Research Project for Analyzing the Formation Process of Japanese Dialects”). These are the data of the elderly surveyed in 1980s and 2010s.

The second group of data is collected from two dialect dictionaries produced by Watanabe (2001) and Toyama (2008). The former is a dictionary of northern Niigata dialects based on Watanabe’s survey data, while the latter is a collection of dialectal words edited from many reports on Niigata dialects; some reports are dated back to the early 20th century, but most reports were published between 1946 and 2000. Both dictionaries show past and contemporary linguistic conditions. The data from Toyama (2008) are also used to draw linguistic maps because the entries have place names where they are used.

Linguistic maps are made using GIS software SIS, except Figure 7 (made using SEAL developed by the author and Figure 13 (whose base map was made using free GIS software Mandara). College students’ data are plotted at the location of a junior high school where they attended.

3. Special Phonological Features of Adjectives in Niigata Dialects

The dictionary of northern Niigata dialects (Watanabe 2001) features dozens of entries of adjectives used in Furumachi, downtown of Niigata city, which show interesting phonological features (Fukushima 2018a). Adjectives in Niigata dialects, especially two-syllable (three-mora) adjectives, often have a long vowel in the second last syllable (Example 1). On the other hand, some adjectives have a short vowel in the second last syllable followed by double consonants (Example 2).

| 1. | “Sweet” Standard Japanese amai Furumachi dialect a:me {ai>e} /a:Ce/ C=/m/ |

| 2. | “Deep” Standard Japanese fukai Furumachi dialect fukke {ai>e} /uCCe/ C=/k/ |

See the list of other adjectives involved (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of adjectives used in Furumachi, Niigata city.

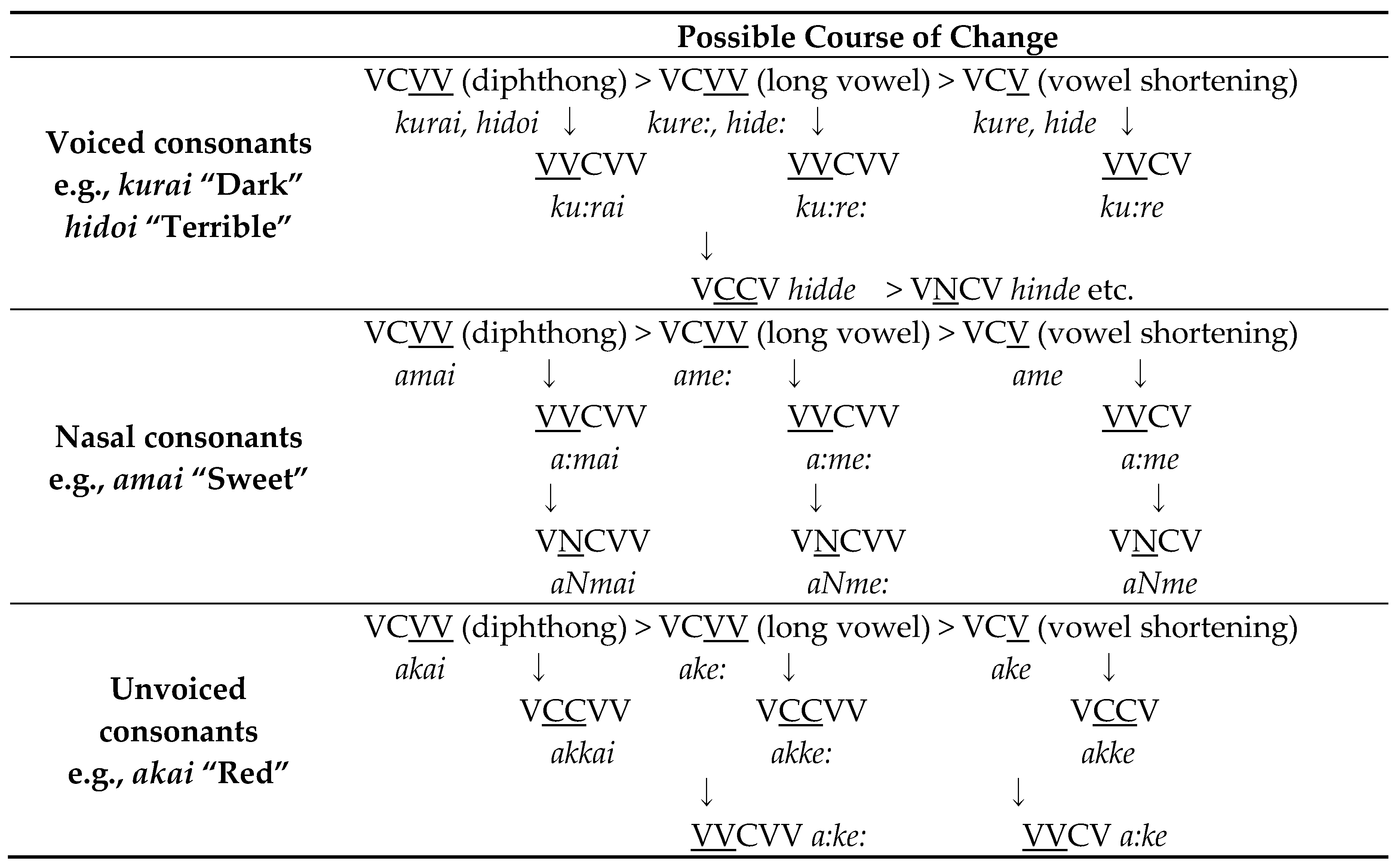

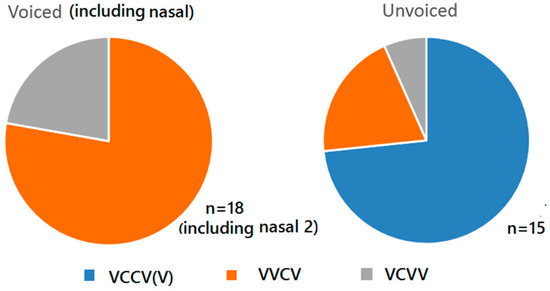

Whether the consonant in the last syllable is voiced or unvoiced seems to influence the choice of either type. As shown in Figure 1, the two pie graphs show different patterns according to whether the consonant involved is voiced or not. If the consonant is voiced, three-fourths of adjectives show the VVCV type (e.g., ku:re). If it is unvoiced, three-fourths of adjectives show either the VCCV or VCCVV type (e.g., kusse or futte:) but one-third of them have the VVCV type (e.g., ho:se).

Figure 1.

Phonological types of adjectives in Furumachi, Niigata: Watanabe data.

These types, VCCV(V) and VVCV, are distinguished as having “heavy syllables”. There is another “heavy syllable” type, VNCV such as amme: “sweet”, which is used in some Niigata dialects.

4. Phonological Variation of Adjectives in Niigata

The linguistic maps of adjectives are drawn based on the CS data. These maps show the use of adjectives by the young generation in Niigata. What change can be detected in their dialects?

The variation of adjectives in the Niigata dialects of the Japanese language is very complex because it consists of different kinds of word forms. Thus groupings are made based on whether the adjectives are standard (Group 1) or dialectal (Group 2) and the variation is then plotted for each group.

4.1. CS Map of the Adjective “Red”: akai

According to Figure 2A,B, the CS maps of akai, “red”, there are two groups of adjectives. Group 1 includes a standard form, akai, and its spoken form, ake: {ai>e:} (Figure 2A). Group 2 includes the VCCV and VCCVV forms, akke(:), akkai, and akkoi, and a VVCV form a:ke (Figure 2B). Figure 2B shows typical dialectal forms which are still maintained by the young generation and show interesting distributions. The form akke is widely distributed, and the form a:ke is found around Niigata city in the center of the akke distribution. Because of the distributions, the form a:ke is interpreted to be a form newer than akke.

Figure 2.

(A) Map (Group 1) of akai “red” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (B) Map (Group 2) of akai “red” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey.

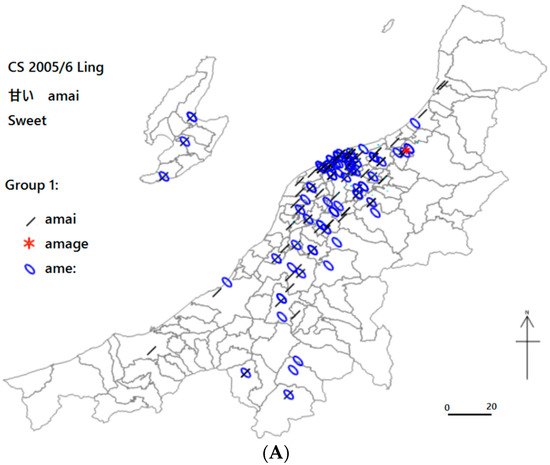

4.2. CS Map of the Adjective “Sweet”: amai

According to Figure 3A,B, the CS maps of amai, “sweet”, two groups of forms are also found. Group 1 includes a standard form, amai, and its spoken form, ame: {ai>e} (Figure 3A). The form amage is a related dialectal form changed from amagoi. Group 2 includes VNCVV forms, ammai and amme:, and VVCV forms, a:me and a:ma (Figure 3B). Figure 3B shows typical dialectal forms maintained by the youngergeneration of dialect speakers. While the form amme: shows a wide and thick distribution compared with akke (in Figure 2B), the form a:me has a larger distribution than a:ke (in Figure 2B). The form a:me seems to be newer than ammai/amme: but this will be discussed later.

Figure 3.

(A) Map (Group 1) of amai “sweet” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (B) Map (Group 2) of amai “sweet” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey.

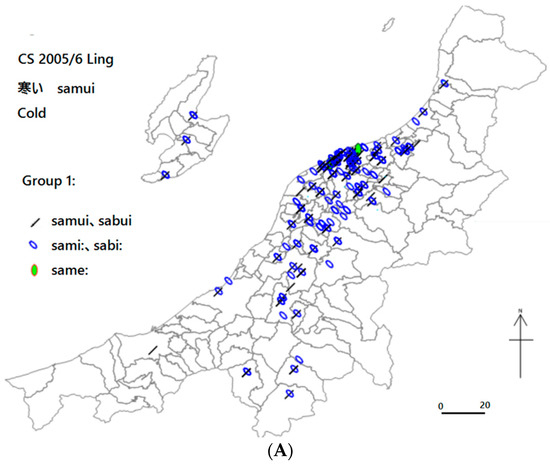

4.3. CS Map of the Adjective “Cold”: samui

According to Figure 4A,B, CS maps of “cold”, two groups of forms are also found. Group 1 includes a standard form, samui, and its spoken forms, sabui, sami:, sabi: and same: {ui>e or >i by analogy} (Figure 4A). Group 2 includes VNCV forms, sammu, sammi, sambi, and samme, and VVCV forms, sa:mu, sa:mi, sa:me, and sa:be (Figure 4B). Figure 4B again shows typical dialectal forms maintained by the younger generation of dialect speakers. The VVCV form sa:me has a thick distribution occupying the central area of peripheral VNCV forms. The form sa:me is also considered as a newer form, but this will be discussed later.

Figure 4.

(A) Map (Group 1) of samui “cold” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (B) Map (Group 2) of samui “cold” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey.

4.4. Discussion

As shown in Table 2, the situation of the Furumachi dialect and the distributions of CS maps described above indicated the following hypothesis (Fukushima 2018a):

Table 2.

The estimated change of phonological types of adjectives in Niigata dialects.

- The traditional Niigata dialects would have had three types of adjective forms:

- VCCV type for unvoiced consonants,

- VNCV type for nasal consonants, and

- VVCV type for other voiced consonants.

- Then the VVCV pattern with a long vowel in the second-last syllable widened its distribution even among the words with other consonants.

The change might have occurred first in the VNCV type and next in the VCCV type considering the size and density of the new distribution. According to the data, Niigata city must be the center of new changes, although the contemporary young people in that area tend to use standard Japanese; Figure 1 shows the results of early innovation in downtown Niigata.

However, the data from Toyama (2008) suggests a different hypothesis. First, the entries of adjectives in Toyama (2008) are classified, counted, and made into graphs like Figure 1 (See Figure 5). The difference from Figure 1 is that nasal consonants include forms of the VNCV(V) types, which are all variants of umai “good/tasty”. Voiced consonants have one form of the VCCV type; for example, hidde is changed from hidoi “terrible”; hidde further changed into hinde and hjande according to another set of CS data (Fukushima 2009).

Figure 5.

Phonological patterns of adjectives in Niigata: Toyama data.

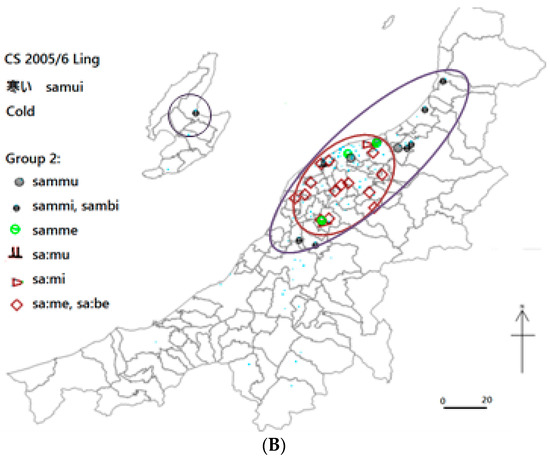

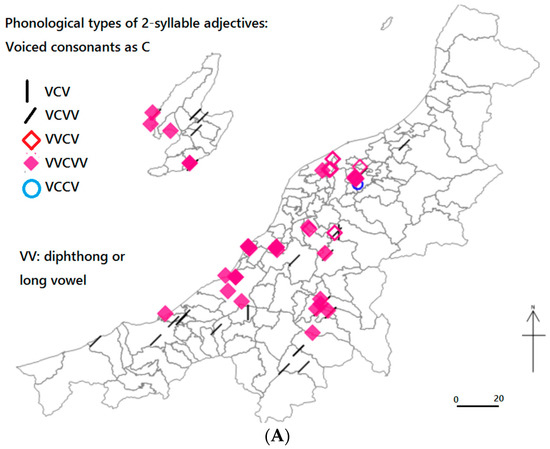

The classified results of adjectives in Toyama (2008) are then plotted on the map using SIS (see Figure 6A–C). In the case of voiced consonants, the VVCV(V) type is distributed in the center and western part of Echigo (the mainland part of Niigata). Interestingly the VVCV type is found in the area around Niigata city, while the VVCVV type is prevalent in a wider area. In the case of nasal consonants, the VVCV(V) type shows similar distributions as voiced consonants, but the VVCV type has larger distributions in the eastern part of Echigo. Also, the VNCV(V) type is found only in the western part of Echigo. In the case of unvoiced consonants, the VCCV(V) type is prevalent, while the VVCV(V) type is found in some part of Echigo.

Figure 6.

(A) Phonological types of two-syllable adjectives (voiced consonants as C): Toyama data. (B) Phonological types of two-syllable adjectives (nasal consonants as C): Toyama data. (C) Phonological types of two-syllable adjectives (unvoiced consonants as C): Toyama data.

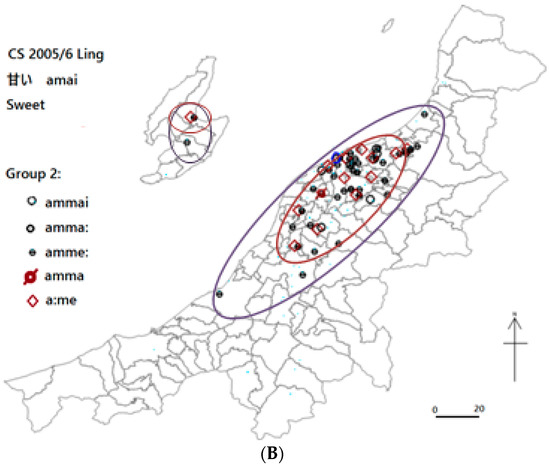

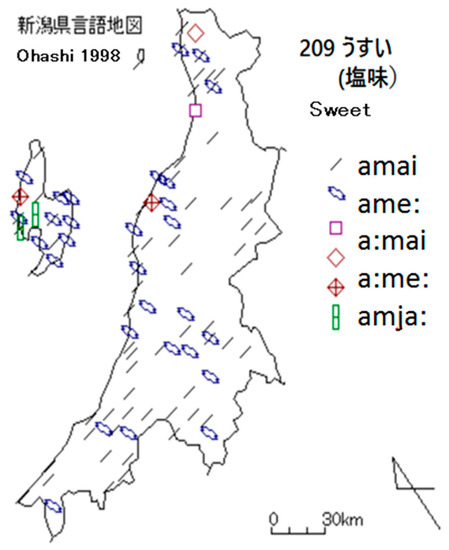

The distribution of nasal consonants as shown in Figure 6B is the problem. Is the VNCV type really old as shown in Table 2? There is another map concerning nasal consonants. Figure 7 is the map of amai “sweet, not salty” from Ohashi (1998), Linguistic Atlas of Niigata Prefecture. This map was redrawn using SEAL by the author. No VNCV(V) forms are found in this map of elderly people surveyed nearly thirty years ago.

Figure 7.

Map of amai “sweet, not salty” from Ohashi (1998).

Then how should we interpret the existence of many VNCV(V) forms in the young generation (Figure 3B)? We can think of two possible reasons. One reason is that emphatic expressions were obtained because of the CS questionnaire. The questions were: What do you say to express “It is COLD today”? What do you say to express “This is SWEET” after you lick sugar? What do you say to express “You are blushing (literally, your face is RED)”? Also, the examples printed on the questionnaire included VNCV forms. Another reason is that different forms can be used by one person to show different strengths. For example, a:me is stronger than ame: and amme: is stronger than a:me. Some college students made interesting remarks on the use of different forms of adjectives. One student stated, “I use different forms according to the sweetness. Thus amme: > amme > a:me > ame:”: here > is a symbol of inequality meaning “greater than”. Another student stated, “I use three different forms, sami:, samui, sa:me, for a change of feeling.”

With these ideas and the distributions of the maps in mind, we can think of the possible course of change in each case, as shown in Table 3. The change on the first line of each case is prevalent not only in Niigata but in other places too. The change on the second line, the vowel lengthening of the second-last syllable, is typical in Niigata and can occur at each stage of the change on the first line (e.g., kurai > ku:rai, ku:re > ku:re:, kure > ku:re; amai > a:mai, ame: > a:me:, and ame > a:me). The addition of a nasal consonant can only happen after this change (e.g., a:mai > ammai, a:me: >amme:, and a:me > amme). The change into a VCCV form in the case of voiced consonants (e.g., hidde) seems exceptional because it only happens to hidoi. The change into VVCV(V) forms in the case of unvoiced consonants (e.g., a:ke: and a:ke) would be a change by analogy rather than a phonological change since a VCCV(V) form would never seem to result in a VVCV(V) form.

Table 3.

The finalized hypothesis on the change of phonological types of adjectives in Niigata.

In the case of adjectives in Niigata, an interesting finding is that different forms can coexist and be chosen according to their strength.

5. Lexical and Morphological Variation of Adjectives in Niigata

5.1. Lexical Variation of the Adjective “Interesting”: Omoshiroi

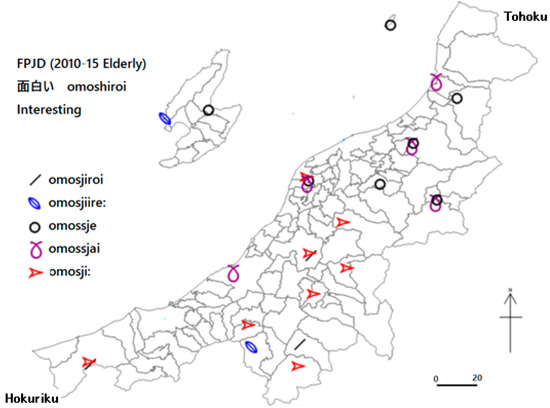

5.1.1. FPJD

The FPJD data shows the present dialectal situation of the elderly generation. The FPJD map of omoshiroi “interesting” (Figure 8) shows contrastive distributions of the eastern dialect forms and western dialect forms. The standard form omosjiroi and its spoken form omosjire are only found in the most southern part of Echigo and Sado Island. The forms omossje and omossjai used in the Tohoku area are found in the northern part of Echigo and Sado Island. The form omosji: used in the Hokuriku area is found in the southern part of Echigo. Omossjai has a peripheral distribution wider than omossje; thus omossje seems to have originated from omossjai. In addition, omosji: is considered to be advancing to the north into Niigata city.

Figure 8.

Lexical variation of omoshiroi “interesting” in Niigata: FPJD data.

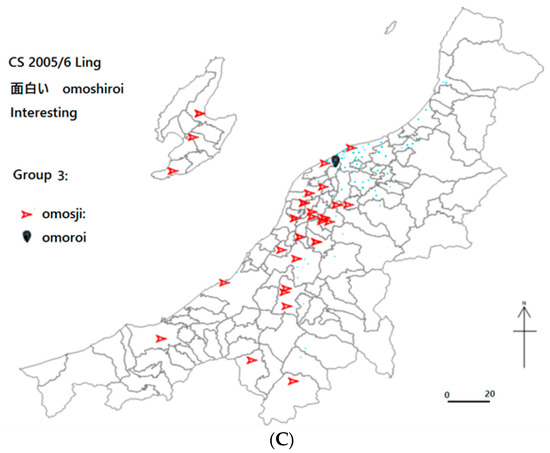

5.1.2. CS

The CS data shows the present dialectal situation of the young generation. The CS maps of omoshiroi “interesting” (Figure 9A–C) show three groups of words, the first two of which show distributions similar to Group 1 and 2 of “red”, “sweet”, and “cold”. That is, Group 1 is a standard form omosjiroi and its spoken form omosjire, and Group 2 is omossje and omosjoi. The form omosjoi which is not found in the FPJD map is distributed in the center of Echigo. The form omossjai which is found in the FPJD map is not found in the CS map. In addition to these, there are Group 3 words, which are omosji: and omoroi, both of which are western dialect words. My interpretation is that omosji: has been used in the southern part of Echigo for some time, and that it has expanded further into Niigata city.

Figure 9.

(A) Map (Group 1) of omoshiroi “interesting” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (B) Map (Group 2) of omoshiroi “interesting” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (C) Map (Group 3) of omoshiroi “interesting” in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey.

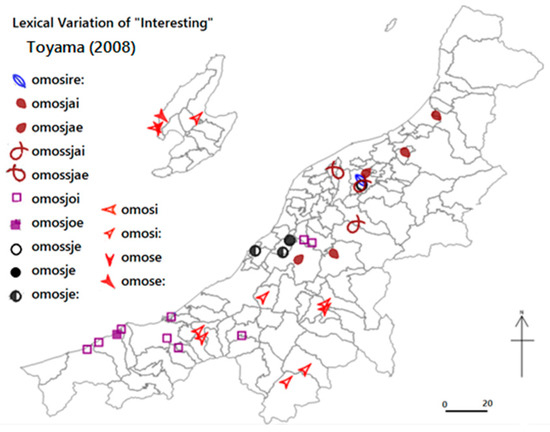

5.1.3. Toyama Data

The map of omoshiroi “interesting” based on Toyama (2008) seems to show the older distributions than the maps shown above (see Figure 10). Look at the contrast between omo(s)sjai in the eastern part of Echigo and omosjoi in the western part of Echigo (the i/e contrast is not clear in Niigata dialects; actually the pronunciation of the vowel is in-between). The form omo(s)sje, which is currently popular among the young generation, is only found in a small area. The form omosji: is found in the southern part of Echigo and Sado Island.

Figure 10.

Lexical variation of omoshiroi “interesting” in Niigata: Toyama data.

5.1.4. Discussion

The following course of change is considered based on the distributions of these maps. The form omosji: should be created by lexical or semantic analogy since most emotional adjectives in Japanese have a –sji: ending: e.g., uresji: (joyful), kanasji: (sad), and tanosji: (merry).

| Eastern part of Echigo | omo(s)sjai | > | omo(s)sje | > | omosji: |

| Western part of Echigo | omosjoi | > | omosji: | ||

| Sado Island | omo(s)sjai | > | omo(s)sje | > | omosji: |

Actually both forms omosjoi and omosji: are used in the adjoining Toyama Prefecture (in the west of Niigata), and the form omos(s)sje in the Tohoku area (in the northeast). They could have spread from outside the Niigata Prefecture, and the form omosji: is advancing to the north in Niigata2.

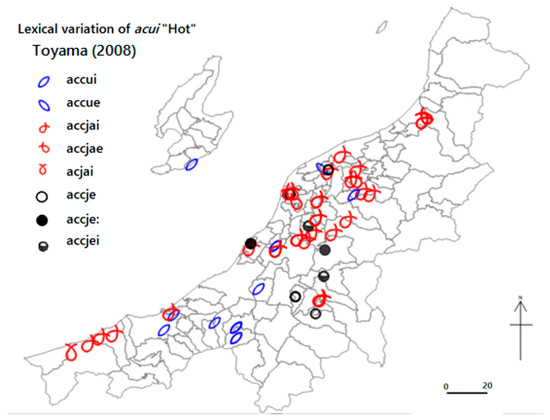

Just for your reference, the map of atsui “hot” based on Toyama (2008) is introduced (Figure 11). This map includes a(c)cjai, which has a larger distribution than omo(s)sjai, and is older, the form a(c)cje originated from it, and the form accui is expanding to the north.

Figure 11.

Lexical variation of atsui “hot” in Niigata: Toyama data.

5.2. Morphological Variation of the Adjective “Interesting” + Past Tense: omoshirokatta

5.2.1. CS

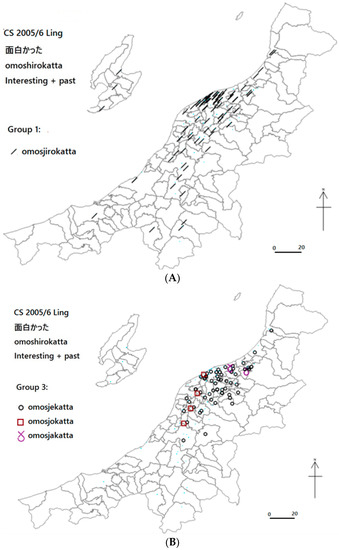

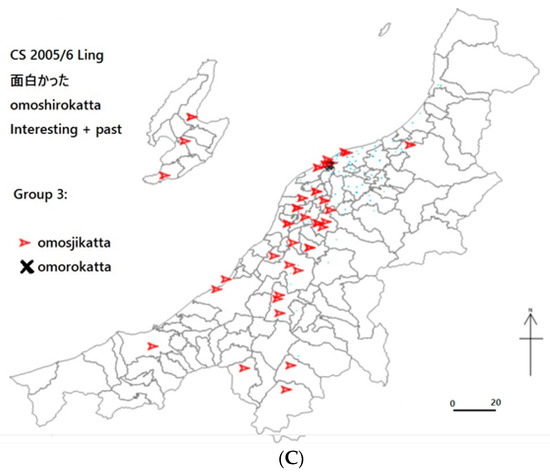

The CS maps of omoshirokatta “interesting” + past tense (Figure 12A–C) also show three groups of words. Group 1 is a standard form omosjirokatta, and Group 2 includes omossjekatta, omossjakatta, and omosjokatta. Unlike Figure 8B which has no omossjai, the form omosjakkata is distributed in the east of Niigata city. This might be a remnant of older conjugation forms. The form omosjokatta shows similar distributions as omosjoi in Figure 8B. There are also Group 3 words, which are omosjikatta and omorokatta, both western dialect words. It is interesting to note that omosjikatta in Figure 12C shows wider distributions than Figure 9C, especially in Niigata city, so that this word might have been introduced as this conjugation form in this area.

Figure 12.

(A) Map (Group 1) of omoshirokatta “interesting” + past tense in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (B) Map (Group 2) of omoshirokatta “interesting” + past tense in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (C) Map (Group 3) of omoshirokatta “interesting” + past tense in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey.

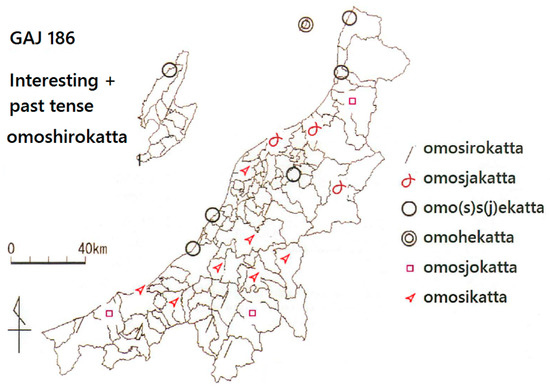

5.2.2. GAJ

Figure 13 is the map of omoshirokatta “interesting” + past tense from GAJ, surveyed in 1980s. The GAJ distributions look in between the CS maps and the Toyama map.

Figure 13.

Map of omoshirokatta “interesting” + past tense: GAJ data.

5.3. Morphological Variation of Adjective Omoshirokunai “Interesting” + Negative

CS

The CS maps of omoshirokunai “interesting” + negative (Figure 14A–C) again show three groups of words. Group 1 includes a standard form omosjirokunai and its spoken form omosjirokune, and Group 2 includes omossje(ku)nai/ne, omossjakunai/ne, and omosjo(ku)nai. Compared with Figure 8B, the use of Group 2 forms does not prevail here, but there is more variety. There are forms with -ku for every possibility but *omossjane is not found. Also, the form omossjakunai is distributed in the west of Niigata city, where omosjoi and omossjokatta are found in Figure 8B and Figure 11B. The dialectal form omosjai could have both omosjakunai/ne and omosjonai/ne as negative conjugation forms, as nagai “long” has nagakunai/ne and nagonai/ne. The latter form is the western dialectal style.

Figure 14.

(A) Map (Group 1) of omoshirokunai “interesting” + negative in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (B) Map (Group 2) of omoshirokunai “interesting” + negative in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey. (C) Map (Group 3) of omoshirokunai “interesting” + negative in Niigata: 2005/6 CS Survey.

5.4. Discussion

| A: omo(s)sje, omossjekatta, omo(s)sje(ku)nai/ne | |

| B: omosjakatta, omo(s)sjakunai | (There is neither*omossjai nor *omossjane.) |

| C: omo(s)sjoi, omossjokatta, omo(s)sjo(ku)nai/ne |

A has a fixed distribution, B sporadic, and C emerging in the young generation. Also considering the distributions in other maps, we can confirm the interpretation expressed in Section 5.1.4.

| Eastern part of Echigo | omo(s)sjai | > | omo(s)sje | > | > omosji: |

| Western part of Echigo | omosjoi | > | omosji: | ||

| Sado Island | omo(s)sjai | > | omo(s)sje | > | omosji: |

The Group 3 forms show different distributions according to the conjugation form. The change in morphology gradually occurs through conjugation forms of each word, which is an example of “lexical diffusion”.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the phonological, morphological, and lexical variation of adjectives in Japanese dialects were examined by classifying forms with regard to the distinction between standard/dialectal forms. The results show that both the geographical data from different surveys and the data from dialect dictionaries are effective to interpret the course of changes. The phonological types of adjectives played a role in the interpretation of the phonological variation and change. Most changes of phonological types are phonologically explained but include change by analogy. The lexical variation is intertwined with phonological variation and morphological variation. The morphological distributions vary according to the conjugation form. This is one example of lexical diffusion.

A major limitation of this study is that the interpretation on the variation and change of adjectives in Niigata dialects is still tentative. It is necessary to examine more data in order to consolidate the results of this study.

Funding

This research was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) 23242024, (C) 16K02688, and (C) 19K00555.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written based on (Fukushima 2018b), the presentation given at Komatsu Round-Table Conference on Geo-linguistics on 8 September 2018. Some part of interpretation was revised. I am grateful to the insights and comments by the commentator and other participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Fukushima, Chitsuko. 2006. Changing Dialects of the Young Generation in Niigata, Japan, with the Focus on Adjectives. In Japanische Beiträge zu Kultur und Sprache: Studia Iaponica Wolfgango Viereck emerito oblata. Studies in Asian Linguistics 68. Edited by Guido Oebel. Munich: Lincom GmbH, pp. 125–39. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima, Chitsuko. 2009. Niigata no joshitandaisei no hogen: jidosha-gakko, sorosoro, namara [Dialects of Female College Students in Niigata: Driving School, Gradually, and Namara]. Niigata no seikatsu-bunka [Life Culture in Niigata] 15: 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima, Chitsuko. 2018a. Variation and Change of Adjectives in Niigata Dialects. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on Asian Geolinguistics, Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia, May 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima, Chitsuko. 2018b. Interplay of Phonological, Morphological, and Lexical Variation: Adjectives in Niigata dialects. Paper presented at Komatsu Round-Table Conference on Geo-linguistics, Komatsu University, Komatsu, Japan, September 8. [Google Scholar]

- National Language Research Institute, ed. 1989–2006. Hogen Bumpo Zenkoku Chizu [Grammar Atlas of Japanese Dialects]; 6 vols. Tokyo: National Printing Bureau of Finance Ministry.

- Ohashi, Katsuo, ed. 1998. Niigata-Ken Gengo Chizu [Linguistic Atlas of Niigata Prefecture]. Niigata: Koshi Shoin. [Google Scholar]

- Onishi, Takuichiro, ed. 2016. Shin Nihon Gengo Chizu [New Linguistic Atlas of Japan: NLJ]. Tokyo: Asakura Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Rabanus, Stefan. 2018. 20 Dialect Maps. In The Handbook of Dialectology. Edited by Charles Boberg, John Nerbonne and Dominic Watt. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 348–67. [Google Scholar]

- Toyama, Masayasu, ed. 2008. Niigata-Ken Hogen Kago Shu [Collection of Words with Non-Standard Pronunciation in Niigata Dialects]. 2 vols. Niigata: Private edition. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Fumio. 2001. Niigataken Hogen Jiten: Kaetsu-Hen. [Dialect Dictionary of Niigata Prefecture: Kaetsu Region.]. Niigata: Nojima Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The change ui>e should be caused by analogy since ui does not generally change to e. Many adjectives in Japanese have an -ai ending, which often changes into -e. This causes the analogical change. |

| 2 | The form omosjiː seems to have been formed by lexical or semantic analogy since most emotional adjectives in Japanese have an -sjii ending: e.g., uresjii (joyful), kanasjii (sad), and tanosjii (merry). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).