Abstract

It has been widely argued that morphological competence, particularly functional morphology, represents the bottleneck of second language acquisition (Jensen et al. 2017; Lardiere 1998, 2005; Slabakova 2008, 2009, 2013). In this study, we explore three challenging aspects of the morphology of Spanish among advanced L1 Ashaninka—L2 Spanish speakers: (i) the acquisition of proclitics and enclitics with inflected verbs; (ii) the distribution of accusative clitics according to the thematic role of the direct object in anaphoric and doubling structures; and (iii) the distribution of clitic forms and their association with gender features. Our results show evidence of the L2 acquisition of clitic structures in L2 Spanish speakers, and no difference between native and L2 speakers regarding sensitivity to thematic roles. However, there are statistically significant differences between groups in the distribution of the gender specification of the clitic antecedents or doubled determiner phrases (DPs). We take these results as evidence in support of the view that morphological patterns can be acquired (proclitics vs. suffixes) as well as preferences for mapping thematic roles onto clitics, but subtle differences in the continuum of preferences for mapping gender features are more difficult to acquire.

1. Introduction

Morphological competence has been identified as the bottleneck of second language acquisition (Jensen et al. 2017; Lardiere 1998, 2005; Slabakova 2008, 2009, 2013). Slabakova (2008) argued that the main challenge for L2 acquisition is the mapping of functional features onto morphology. Proponents of this view have traditionally focused on difficulties in the process of assembly of syntactic features and their morphological representation. Assembly may be rendered especially difficult when the L1 lacks the overt morphology present in the L2, as is the case for tense among L1 Chinese–L2 English learners, especially if the L2 learners have other syntactic resources to convey temporal meaning, such as adverbial adjuncts (Lardiere 1998).

Second language acquisition of morphology may be further complicated when the L1 lacks a syntactic feature that lies at the interface of syntax, morphology and the lexicon in the L2, as is the case with noun gender marking among L1 English–L2 Spanish learners (Hawkins and Franceschina 2004). Even in cases in which the L1 and the L2 exhibit gender as a syntactic feature that triggers agreement between a noun and other categories, differences in gender feature values assigned to corresponding lexical items (a masculine noun in the L1 is feminine in the L2) may result in difficulties in L2 acquisition (Sabourin et al. 2006). Even among advanced L2 learners, evidence of difficulties with gender assignment can be found in the longer reaction times to grammaticality judgments than those of monolinguals (Kirova 2016). These differential results have been attributed to the fact that gender involves the assignment of features to a lexical item as well as the syntactic operation agreement. While L2 learners may be able to master syntactic agreement, its assignment presents challenges especially when gender feature values are non-congruent in L1 and L2 (Sabourin et al. 2006; Kirova 2016). Difficulties in the L2 acquisition of gender features affects not only nouns but also pronominal forms. In the case of accusative clitics, in addition to evidence of difficulties in the acquisition of gender among L2 learners (Grüter 2005; Mayer and Sánchez 2016), there is evidence from child monolingual acquisition of French that clitics marked for gender (third person) are more difficult to acquire than those not marked for it (first and second person) (Delage et al. 2016).

Difficulties in the integration of lexical items, morphemes, and syntactic features are not the only challenges for the development of morphological competence in a second language. Typological differences in morphological patterns also pose challenges in second language acquisition. Differences between agglutinative languages and synthetic ones have been argued to be at the base of difficulties in the acquisition of L2 morphology (Montrul 2001). In some cases, these differences include crosslinguistic differences in phonological patterns. As Abramsson (2003) notes, acquisition of word-final morphology may be affected by the lack of codas in L1 among Chinese L1–Swedish L2 learners. Difficulties in L2 acquisition of morphology in contexts of typological differences can be related to the role that processing of (morpho) syntactic patterns has in L2 acquisition (Pienemann 1998). To acquire morphological patterns that diverge from those in their L1, L2 learners need to be able to recognize them as part of a new morphological template (Freynik et al. 2017). On the basis of evidence from previous studies, at least two sources of difficulties that L2 learners have to overcome to develop morphological competence have emerged: (i) the integration of morphology and other language components (syntax, phonology, and the lexicon) and (ii) crosslinguistic differences in morphological patterns or templates. Determining the extent to which the development of morphological competence in a second language is affected by crosslinguistic differences in the integration of morphology and other language components and by differences in morphological templates, even among advanced early L2 learners, is the main goal of this paper.

Research on the acquisition of direct object argument markers in Spanish as a second language by speakers of Ashaninka presents the ideal situation to study both factors. Spanish and Ashaninka have gender marking in direct object morphemes and exhibit differences in their morphological templates. While in Ashaninka, subject markers are prefixes and object markers are suffixes, as shown in (1), Spanish requires syntactic proclitics with inflected verbs and enclitics with non-inflected verbs, as shown in (2) and (3) respectively.1

| 1. | No-kib-ak-e-ro |

| 1SG.A-wash-PERF-REAL-3F.O | |

| ‘I washed it.’ |

| 2. | Lo | lav-é |

| CL.3MSG | wash-PERF.1SG | |

| ‘I washed it.’ | ||

| 3. | Quier-o | ver-lo |

| want-1SG | see.INF-CL.3MSG | |

| ‘I want to see it.’ | ||

At the surface level, sentences such as (1) and (2) show the opposite order regarding argument marking; in Ashaninka, subject marking is pre-verbal while object marking is post-verbal. In Spanish, the direct object is a proclitic, and the subject is marked as a suffix. This inverse ordering of morphological markers should, in principle, present difficulties for second language acquisition as proposed by Pienemann (1998) if processing strategies in the L1 play a role in the recognition of morphological patterns in the L2. Furthermore, this surface order is altered in the case of the uninflected verb in (3)—the direct object is an enclitic, and there is no subject marking on the verb.

In addition to these differences, two other important distinctions between Ashaninka and Spanish in contact with Ashaninka must be noted, one related to the morphological expression of gender in direct object marking and the other one related to thematic roles. Contact varieties of Spanish exhibit gender agreement between determiners and nouns. However, unlike in other varieties of Peruvian Spanish where accusative clitics have a stricter correspondence between the clitic form and gender features of their referents (lo for masculine noun phrases (NPs) and la for feminine NPs), some Contact Spanish varieties exhibit a scalar system of accusative clitics (le > lo > la) in which le and lo may have masculine or feminine antecedents (Mayer 2017; Mayer and Sánchez 2016). Native dominant speakers of this type of Contact Spanish are the source of input for L2 learners of Ashaninka Spanish and exhibit a preference for le over lo for masculine referents and some uses of la for feminine referents, which remains available, although limited, in the input for L2 learners.

Concerning thematic structure, we assume a difference in the degree of affectedness of patient and theme objects (Næss 2004). In (2), the patient object undergoes a change, whereas in (3), the theme object remains unchanged. While, in most varieties of Spanish, thematic roles do not seem to be an important source of differentiation between le and lo/la, in Ashaninka, masculine themes and patients can be marked with either -ro (fem) or -ri (masc) (Payne 1981; Reed and Payne 1986; Mihas 2010, 2015) but there is a gender-neutral marker, -ni, for third person theme objects (Mihas 2015, p. 200). The existence of such distinction in Ashaninka could be the source of some form of transfer among the L2 learners.

Despite these differences, as we will see in the next subsection, both Ashaninka and Spanish allow for doubling of a strong pronoun or, in some cases, a DP, with an object marking morpheme (a suffix in Ashaninka, a clitic in Spanish), making the differences in morphological templates and the assembly of features the focus of the difference between the two languages.2

In this study, we explore three challenging aspects of the morphology of Spanish among advanced L1 Ashaninka–L2 Spanish speakers with an early age of acquisition of Spanish who live in a contact situation, as follows: (i) the acquisition of proclitics and enclitics with inflected verbs in doubling and non-doubling structures as they show evidence of the acquisition of a diverging morphological pattern; (ii) the distribution of clitic forms and their association with gender features, as evidence of the integration of morphological forms at the interface with the lexicon and syntax; and (iii) the distribution of accusative clitics according to the thematic role of the direct object, as it pertains to the integration of morphology and argument structure. Even if early advanced L2 learners living in a contact situation show difficulties in these three areas and also exhibit different patterns from those of Spanish-dominant simultaneous bilinguals who are their source of input, we will be able to determine the extent to which each aspect under study presents a challenge for L2 acquisition.

1.1. Theoretical Linguistic Background for Ashaninka and Spanish Languages

1.1.1. Ashaninka Morphosyntax

Ashaninka is part of the Arawakan language family. Regarding its case typology, it exhibits nominative-accusative alignment in transitive clauses and fluid transitivity or split intransitive alignment in intransitive clauses (Payne and Payne 2005; Mihas 2015, p. 5). The basic constituent order is either verb-subject (VS) or verb-object (VO) with verbal suffixes obligatorily marking agent/subject (A/S) and patient/object (P/O) arguments. While the subject of a transitive clause receives A-marking, the subject of an intransitive clause receives S-marking. Marking of both arguments is either pre- or post-verbally and is governed by their respective semantic roles. The basic word order for intransitive clauses is verb–intransitive subject, and for transitive clauses it is verb–object.

Nominative-accusative alignment in Ashaninka requires obligatory verbal agreement of both arguments in the main transitive clauses as shown in Examples (4). The A argument (transitive subject) is a prefix on the verb and the O argument (transitive object) a suffix (Mihas 2015). The transitive object markers -ri (M) and -ro (NM) are suffixes marked for person and gender with the non-masculine object marker as the default feminine marker (Mihas 2015, p. 200). Note that the semantic roles, agent (4a) and experiencer (4b), even with verbs of perception (4c) receive the same marking.

| 4. | a. | No-pichov-ak-e-ro | pichori | pichori | |||||

| 1SG.A-grind-PFV-REAL-3NM.O | |||||||||

| ‘I ground it [leaves] with my hands, pichori pichori ‘grinding action’.’ | |||||||||

| b. | No-ñ-i-ri | ||||||||

| 1SG.A-see-REAL-3M.O | |||||||||

| ‘I saw him.’ | |||||||||

| c. | No-yo-tz-i-ro | ||||||||

| 1SG.A-know-EP-REAL-3NM.O | |||||||||

| ‘I knew it.’ | |||||||||

However, transitivity is not fixed and is mostly determined by the lexical meaning of the verb root. Ashaninka makes generous use of valency increasing and decreasing suffixes with some verbal roots allowing for fluid transitivity which is expressed in morphology and syntax. Moreover, as shown in (5), ambitransitive verbal roots may or may not show the morphological marking of their increased or decreased value of valency (Mihas 2015, p. 194).

| 5. | a. | N-a-ak-i | kaniri | ||

| 1SG.S-take-PERF-REAL | manioc | ||||

| ‘I obtained manioc roots.’ | |||||

| b. | N-a-ak-i-ri | ||||

| 1SG.A-take-PERF-REAL-3M.O | |||||

| ‘I took him [as a spouse].’ | |||||

While subjects are marked obligatorily on the verb, object arguments receive verbal marking depending on grammatical function, i.e., semantic role (patient, theme) and information status. Object arguments can be crossreferenced by an overt pronoun, as in (6a), with demonstratives in the post-verbal (6b) and pre-verbal (6c) positions. As a general rule, overt coreferential DPs always appear to be right dislocated, as in (5a) (Mihas 2015, pp. 409, 199–200).

| 6. | a. | Y-ook-ai-t-an-ak-i-ri | irirori | i-piyatsa-t-a | |||

| 3M.A-abandon-IMP-EP-DIR-PFV-REAL-3M.O | 3M.FOC | 3M.S-disobey-EP-REAL | |||||

| ‘They abandoned him, too, [because] he disobeyed.’ | |||||||

| b. | Pi-yo-tz-i-ri | iyoka? | |||||

| 2A-know-EP-REAL-3M.O | DEM.NOM.M | ||||||

| ‘Do you know this one (masculine)?’ | |||||||

| c. | Rora | no-saa-tz-i | no-shipok-i-ri | ||||

| DEM.NOM | 1SG.S-sweat-EP-REAL | SG.A-bathe.with.herbs-REAL-3M.O | |||||

| ‘Those [patients] I steam-bathe; I bathe them with herbs.’ | |||||||

In ditransitive argument structures, the theme can be marked in two ways, with one of the gender-specifying object suffixes -ri or -ro, as in (7a), or with the gender-neutral specific theme marker, -ni, as in (7b) (Mihas 2015, pp. 200–2).

| 7. | a. | Iro | p-ak-e-na-ro | ||||||

| 3NM.TOP | give-PFV-REAL-1SG.R-3NM.T | ||||||||

| ‘She was the one who gave it to me.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Iroñaaka | no-tyank-i-ni-ri | aisatzi | no-tomi | saik-atsi-ri | ||||

| now | 1SG.A-send-REAL-3T-3M.R | also | 1SG.POSS-son | be.at-STAT-REL | |||||

| Irimashi-ki | |||||||||

| NAME-LOC | |||||||||

| ‘I sent it [money] to my son, who is living in Lima.’ | |||||||||

The suffixes -ri (M) and -ro (NM) are used to mark either of the two gender classes on some nouns, adjectives, demonstratives, third-person pronouns and verbal S and O agreements. While masculine gender is used to refer to mixed groups of people and animals, specific groups can receive gender-specific marking. A basic distinction in allocating gender on nouns is sex for human nouns and animacy for inanimates. For the latter, the animate/inanimate distinction is based on cultural assumptions related to their mythology, and inanimates are marked by the non-masculine default. Also, gender agreement is quite complex due to the existence of plenty of exceptions (cf. Mihas 2015, pp. 330–32).

In sum, Ashaninka marks transitive objects with bound morphemes in the form of verbal affixes, which are syncretically specified for person and gender. In addition, free personal pronouns occurring in either pre-verbal or post-verbal positions are used to mark information structure, but overt NPs are always post-verbal. As we will see in the next section, these structures have corresponding ones in Spanish. The existence of three common surface orders (pre- and post-verbal strong pronouns as well as doubled post-verbal NPs) in both languages may contribute significantly to the acquisition of Spanish clitic doubled and dislocated structures by Ashaninka–Spanish bilinguals. Thus, Ashaninka shares the following attributes with Spanish: (1) a set of features including number and gender mapped onto a bound morpheme; (2) the existence of overt pronouns co-occurring with bound argument-marking morphemes; and (3) the possibility of restructuring word order pragmatically by marking information structures with pre- and post-verbal overt pronouns co-occurring with verbal agreement, as well as by NP doubling.

1.1.2. Spanish Morphosyntax

Spanish is part of the Romance family. It is similar to Ashaninka with respect to nominative-accusative alignment and subject and object verbal agreement marking. Spanish has a set of optional subject pronouns and gender and number-specifying direct object clitics. Spanish clitics have been identified as morphological markers (Suñer 1988) at the phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and information structure interface (Belloro 2007; Mayer 2017; Ordóñez and Repetti 2006; Spencer and Luís 2012; Zwicky 1985). They play an important role in argument marking (Harris 1995).

Typically,3 clitic pronouns or direct object clitics are phonologically unstressed pronouns; they show gender and number features and are dependent on a verbal host. With single inflected verbs, they occur in anaphoric agreement as proclitics as in (8).

| 8. | Ella | lo | /la | v-ió | |

| PRO.3FSG | CL.3MSG | /CL.3FSG | see-PST.3SG | ||

| ‘She saw him/it, her/it.’ | |||||

In structures with inflected and uninflected verbs such as restructuring constructions, clitics can occur in either position, as enclitics attached to the non-finite verb, as in (9a), and as proclitics preceding the finite verb in the form of clitic climbing, as in (9b).

| 9. | a. | Ella | quiere | v-er.lo/la | |||

| PRO.3FSG | want-3SG | see-INF.CL.3MSG/CL.3FSG | |||||

| ‘She wants to see him/it, her/it.’ | |||||||

| b. | Ella | lo/la | quier-e | v-er | |||

| PRO.3FSG | CL.3MSG/CL.3FSG | want-3SG | see-INF | ||||

| ‘She wants to see him/it, her/it.’ | |||||||

Clitic doubling (CLD), as in (10), that is, co-occurrence of a clitic with a referential full DP is accepted in some varieties and restricted to pronominal DPs in most. In doubling constructions, strong pronouns or full DPs are usually preceded by the differential object marker a, also known as Kayne’s Generalization (Kayne 1975).

| 10. | Lo | v-i | a | él | / Juan |

| CL.3MSG | see-PST.1SG | DOM | PRO.3MSG | / Juan | |

| ‘I saw him, Juan.’ | |||||

Like Ashaninka, Spanish marks information structure by word order rearrangement in terms of clitic left dislocation (CLLD) (11a) and clitic right dislocation (CLRD) (11b).

| 11. | a. | A | Juan | lo | vi | ayer | ||||||

| DOM | Juan | CL.3MSG | see-PST.3SG | yesterday | ||||||||

| ‘As for Juan, I saw him yesterday.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | Lo | vi | ayer | a | Juan | |||||||

| CL.3MSG | see-PST.3SG | yesterday | DOM | Juan | ||||||||

| ‘I saw him, Juan, yesterday.’ | ||||||||||||

As shown above, Spanish exhibits a highly complex interaction of differential object marking (DOM) and feature-specifying clitics to identify the grammatical functions of the object arguments. The thematic roles of these arguments depend on the subcategorization frames of the predicate and play an important part in the conceptualization of its meaning (Dryer 1986; Jackendoff 1990; Andrews 2007; a.o.).

For the purpose of this study we are only concerned with the main thematic roles which include the agent (typically assigned to the external argument or subject); patient (typically assigned to internal arguments or direct objects) as the main active participatory roles with transitive verbs (e.g., kill) as in (12) where all patient objects [+human, +animate,−animate] undergo a change; and theme (also typically assigned to internal arguments or direct objects) with perception verbs (e.g., see) as in (13) where the direct object arguments [+human, +animate, −animate] remain unchanged exhibiting marginal to no participation in the verbal action. Both examples show no difference in case marking based on the semantic roles. They only differ with regard to animacy where human objects receive obligatory case marking, animate objects receive optional marking, and inanimate objects receive no case marking at all.

| 12. | Clara | mata | a | Juan | / (a) la | mosc-a / el | tiemp-o |

| Clara | kill.3SG | DOM | Juan | / (DOM) DET.FSG | fly-FSG / DET.MSG | time-MSG | |

| ‘Clara kills Juan / the fly / time.’ | |||||||

| 13. | Clara | ve | a | Juan / (a) | la | mosc-a / el | tiemp-o |

| Clara | see.3SG | DOM | Juan / (DOM) | DET.FSG | fly-FSG/DET.MSG | time-MSG | |

| ‘Clara sees Juan / the fly / time.’ | |||||||

One of the main characteristics that may result in differences in morphological marking of internal arguments is the affectedness of the object (Dalrymple and Nikolaeva 2011; Hopper and Thompson 1980; Mayer 2017; Næss 2004). Patient objects are directly affected by the verbal action through a volitional agent and manifest a visible change of state. The optionality of marking animate nonhuman objects and the lack of morphological marking of inanimates shows that affectedness is (a) gradient and (b) strongly correlated with the semantic features, animacy and definiteness of the object NP. However, unlike Ashaninka which distinguishes between patients and themes with different argument markers on ditransitive verbs, as shown in examples (7a and b), most varieties of Spanish do not exhibit sensitivity to semantic roles in the selection of a clitic form in doubling expressions. In most varieties, patients and themes do not receive specialized clitic forms in Spanish. As we will see below, this might not reflect the input that Ashaninka L1–L2 Spanish speakers receive from native speakers of Spanish in contact with Ashaninka as there seems to be some preference for forms like le for themes and lo for patients among them.

The complex combination of different morphosyntactic templates, feature-specifying clitics and differential morphological case-marking based on verbal lexical semantics in Spanish in contact with Ashaninka presents Ashaninka L2 learners with an intricate morphological and syntactic path of acquisition that may result in residual non-target forms even among advanced learners.

1.2. Research Questions and Hypothesis

Given the main differences between Ashaninka and Spanish with respect to the morphosyntactic patterns, feature specification and semantic roles involved in the marking of the internal arguments presented above, in this paper, we explore the following research questions, as they pertain to the oral production of advanced early L2 learners living in a contact situation:

- How do differences in morphological patterns between L1 and L2 affect the L2 acquisition of internal argument marking (Spanish cliticization)?

- Do gender features that require assembly at the interface of the lexicon, syntax and morphology present difficulties for the acquisition of clitic structures?

- Is the L2 acquisition of internal argument clitics affected by sensitivity to thematic roles in the L1?

We formulated the hypotheses below:

- Differences in morphological templates (suffixes vs. proclitics) should present difficulties in second language acquisition. If morphology, per se, is the bottleneck of second language acquisition, irrespectively of the integration or assembly of features from different components, we would expect that even at higher levels of proficiency, L2 learners will exhibit some residual difficulties with cliticization.

- Feature assembly that requires the interface of syntax, morphology and lexicon, such as the assembly of gender features in pronominal clitics, presents difficulties for second language learners, even if the L1 has such features. If the main challenge in second language acquisition of morphology stems from difficulties in the integration of different language components, we expect L2 learners to show difficulties with gender assembly.

- Mapping of semantic roles onto morphology should also be difficult in L2 acquisition, as it requires some level of integration of different language components, especially if the L1 exhibits some differences from the L2.

If our first hypothesis is correct, we expect to find significant differences between L2 learners and Spanish-dominant native speakers with respect to the availability of proclitics with inflected verbs. Support for our second hypothesis would come from differences between native and L2 speakers in the distribution of clitics. L2 learners should exhibit a higher frequency of clitics unmarked for gender and a lower frequency of clitics that correspond to the gender of their antecedents. Finally, support for our third hypothesis would come from differences in the mapping of semantic roles onto Spanish clitics between natives and L2 learners that reflect L1 patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

The data presented here are part of fieldwork data collected in 2016 in two native Ashaninka communities in Peru in the Satipo and Puerto Ocopa areas of the Junín province in the Amazonian region of Peru: Arizona Portillo and Puerto Ocopa.

2.1. Participants

For this study, we analyzed the oral production of dominant Spanish native speakers (N = 9) (SN) and advanced L1 Ashaninka–L2 Spanish speakers (N = 18) (L2) matched for proficiency (Australian National University, Dr. Mayer, ANU Ethics Protocol 2016/502, Record number: 8473 and Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Dr. Sánchez, Rutgers, IRB Protocol number: El7-168). Both groups were living in a contact situation at the time of the interviews. Participants in both groups scored 8 or higher out of 10 in the proficiency test. Of the total of 27 participants, 13 were drawn from Arizona Portillo and 14 from Puerto Ocopa.

Dominant Spanish speakers reported Spanish as their first and childhood language. Two of them stated that they had no knowledge of any other language, and three stated that they had some basic understanding of English. Four stated they had some very basic knowledge of Ashaninka and one participant had some knowledge of Yanesha. As shown in Table 1, seven out of the nine dominant Spanish native speakers came from Arizona Portillo and two from Puerto Ocopa, six females, and three males. Three participants, one female, and one male as well as the only older participant, a 67-year-old male, had primary education (Prim). Three females had secondary education (Sec), and two females and one male had higher education (HE). For the latter, HE refers to an Agricultural Technical Institute in the Puerto Ocopa Community, where students are taught in both languages, Spanish and Ashaninka.

Table 1.

Spanish native speakers (SN) by age, location, education, and gender.

The numbers of L2 Spanish participants were even across the two age groups and communities, with six from Arizona Portillo and twelve from Puerto Ocopa, as shown in Table 2. The age of acquisition of Spanish in this group ranged from 6 to 15 years old, and in some cases, this coincided with exposure to Spanish through the school system. Gender distribution was the same as for the SN group, albeit with doubled numbers, with twelve females and six males, distributed evenly across both age groups. The distribution of education was the reverse for the age groups. The younger generation had one male with primary education, three with secondary education—one female and two males—and five with higher education—four females and one male. The older generation included four females with primary education, four with secondary education—two females and two males—and a female with higher education. Higher education refers to the participants from the Agricultural Technical Institute in the Puerto Ocopa Community.

Table 2.

Advanced L2 Spanish speakers by age, location, education, and gender.

At the time of the data collection, all participants were living in their communities and were actively involved in maintaining the livelihood and safeguarding the security of their communities through nightly border controls. Except for three older participants, all others claimed to be able to read and write in Spanish, and very few younger L2 bilinguals, specifically in Puerto Ocopa, claimed to be able to read and write in Ashaninka.

Both communities are rural, but the Arizona Portillo community is relatively close to Satipo, which is the major trading town in the province. This community is quite small, with around 60 families, led by an indigenous leader who is a linguist and strong advocate for intercultural bilingual education. Most adults work either in Satipo or close to Satipo while tending to their fields after work. Different from most Ashaninka communities, they accept speakers of other indigenous languages into their community. Community bilingualism is supported by the community and the local primary school. Arizona Portillo is one of the very few Ashaninka communities where the students in the bilingual primary school are taught by an Ashaninka-speaking teacher. The community of Puerto Ocopa is quite large with around 200 families and very healthy community bilingualism. They have educational and medical infrastructure, the latter in the form of a small hospital and an ambulance. The local bilingual primary and secondary school is run by Quechua-speaking nuns who live in the convent that houses orphans and children sent to attend school from remote Central Amazonian communities. Ashaninka is not taught due to a lack of certified Ashaninka teachers, but it is spoken during recess and at home. The Agricultural Technical Institute is unique in its approach of combining technical knowledge about sustainable local agriculture and nursing with indigenous language and culture. Students study their subjects in both languages, Spanish in oral and written form and Ashaninka mostly in oral form, despite the availability of a unified alphabet.

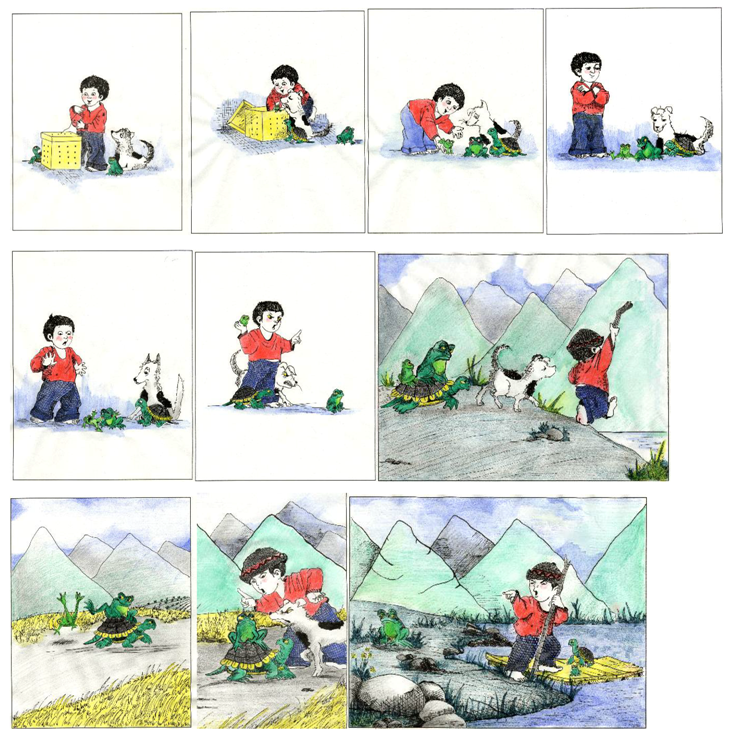

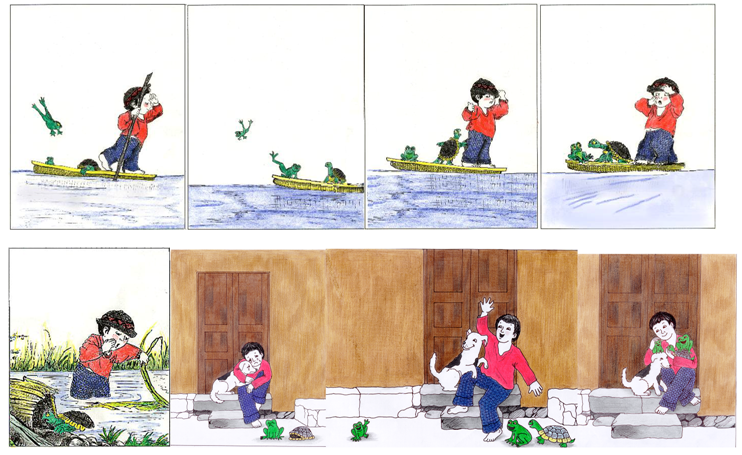

2.2. Instruments and Procedures

To investigate the research questions, we used a questionnaire about language history, preferences for language use and attitudes towards Ashaninka and Spanish, followed by a picture-based elicitation task, both orally administered and followed by a written Spanish proficiency test (see Appendix A for all instruments). The short Spanish proficiency test was adapted from the cloze test section of the DELE version used in Cuza et al. (2013). The biographic questionnaire and the oral narrative of the frog story based on the pictures were recorded. For this study, only the latter was transcribed using CHILDES in ELAN software (The Language Archive, Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, The Netherlands). All transitive verbs with clitics and null arguments were coded according to (i) morphological patterns (proclitics vs. enclitics); (ii) the gender of the antecedent or doubled DP; and (iii) the thematic role of the object. For this study, participants were divided into two groups: SN and L2 on the basis of the biographical data from the questionnaire. Both groups were matched for proficiency using the results of the language proficiency test with a cutoff point of 8 or higher out of 10 points. All participants except for three older illiterate people filled in the proficiency test themselves after the oral narration. Participants’ proficiency in Ashaninka was not tested.

3. Results

3.1. Acquisition of Morphological and Syntactic Patterns

Concerning the distribution of proclitics and enclitics, L2 acquirers showed no statistically significant differences from contact L1 speakers who were their source of input (Table 3). A chi-square test did not confirm independence of preference (χ2(2, N = 335) = 0.05, p = 0.97).

Table 3.

Proclitics vs. enclitics.

The following are examples of sentences with a proclitic and an enclitic produced by second language learners:

| 14. | Proclitics | ||||||

| Le | bot-ó | al | agua | ||||

| CL.3SG | throw-PST.3SG | LOC-DET.MSG | water | ||||

| ‘He threw him into the water.’ | |||||||

| 15. | Enclitics | |||||||||

| Y | el | niño | <(es)t-á> | [/] | (es)t-á | llev-ándo-le | ||||

| and | the | boy | be-3SG | be-3SG | carry-GERUND-CL.3SG | |||||

| ‘And the boy is bringing it.’ | ||||||||||

As we will see below, there were only two cases of reduplication of an internal argument in a restructuring context involving a proclitic and an enclitic (20) which was the only indication of some residual difficulty with cliticization (see the Discussion).

The distribution of clitic structures in the narratives of the two groups did not differ significantly either (Table 4). A chi-square test did not confirm independence of preference (χ2(4, N = 335) = 5.87, p = 0.20).

Table 4.

Clitic structures.

The group of L2 learners produced sentences with anaphoric clitics (16) as well as sentences with CLD (17), CLLD (18), CLRD (19) and two cases of reduplication which are exemplified in (20):

| 16. | Anaphoric | ||||||||

| El | perro | también | lo | mir-ó | amargo | ||||

| the | dog | also | CL.3MSG | see-PST.3SG | bitter | ||||

| ‘The dog too looked at him upset.’ | |||||||||

| 17. | CLD | ||||||||

| El | niño | le | alz-a | al | perr-it-o | ||||

| the | boy | CL.3SG | carry-3SG | DOM-DET.MSG | dog-DIM-MSG | ||||

| ‘The boy picks up the little dog.’ | |||||||||

| 18. | CLLD | ||||||||

| Al | otro | sap-it-o | le | habían | dejado | porque | |||

| DOM-DET.MSG | other | toad-DIM-MSG | CL.3SG | have | left-PARTIC behind | because | |||

| era | muy | gruñón | |||||||

| be.3.PST | very | grumpy | |||||||

| ‘They had left the other toad behind because he was very grumpy.’ | |||||||||

| 19. | CLRD | |||||||

| Aquí | le | está | carg-ado | la | tortug-a | al | sap-o.4 | |

| here | CL.3SG | be.3SG | carry-PARTIC | DET.FSG | turtle-FSG | DOM-DET.MSG | toad-MSG | |

| ‘Here, the turtle has carried the toad.’ | ||||||||

| 20. | Reduplication | |||||||

| Para | que | lo | pued-e | describir-le | ||||

| for | that | CL.3MSG | can-3SG | describe.CL.3SG | ||||

| ‘So that he can describe him.’ | ||||||||

Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to the distribution of the clitic forms, nor with respect to clitic omission, as shown in Table 5. A chi-square test did not confirm independence of preference (χ2(4, N = 334) = 2.20, p = 0.69).

Table 5.

Distribution of clitics and null pronouns.

We take this to indicate that even though the frequency of the feminine form la was very low in this task among native and L2 learners, it is not completely absent from the oral production of some individuals in both groups.

As in previous studies of Spanish in contact with indigenous languages such as Quechua and Shipibo in Peru based on data from oral narratives (Mayer and Sánchez 2016, 2017), the distribution of direct object clitics shows a hierarchical pattern in which the clitic le is more frequent, followed by lo, la and l’ before vowels, as the following examples from native speakers show:

| 21. | El | ñiño | le | ha | conseguido | a | los | dos, | a | los | |

| the | boy | CL.3SG | has | get-PARTIC | DOM | DET.MPL | two, | DOM | DET.MPL | ||

| perr-it-os, | la | ran-a | y | la | tortug-a | ||||||

| dog-DIM.MPL | DET.FSG | frog-FSG | and | DET.FSG | turtle-FSG | ||||||

| ‘The boy has gotten both of them, the little dogs, the frog and the turtle.’ | |||||||||||

| 22. | El | ñiño | lo | abr-ió | <el> | [//] | la | caj-a |

| the | boy | CL.3MSG | open-PST.3SG | DET.MSG | DET.FSG | box-FSG | ||

| ‘The boy opened the box.’ | ||||||||

| 23. | En | realidad | <las> | [//] | los | quiere | a | tod-os |

| in | reality | CL.3FPL | CL.3MPL | love-3SG | DOM | all-MPL | ||

| ‘In reality (s)he loves them all.’ | ||||||||

| 24. | La | tortug-a | l’ | está | molest-ando | al | sap-o |

| DET.FSG | turtle-FSG | CL.3SG | is-3SG | bother-GERUND | DOM-DET.MSG | toad-MSG | |

| ‘The turtle is bothering the toad.’ | |||||||

The preference for le has been attributed in some of those previous studies to the fact that the L1 of the substratum languages (Quechua and Shipibo) lacks gender. This is not the case for Ashaninka speakers as internal argument morphemes in Ashaninka are marked for gender. Different from Spanish though, feminine gender is marked in Ashaninka as the default gender, whereas masculine is the default in Spanish.

As mentioned above, among doubling structures, the most frequent was CLD with a higher frequency of le followed by lo and very low numbers of la and l’ among Spanish-dominant speakers and L2 learners (Table 6).

Table 6.

Clitics according to clitic doubling structure.

3.2. Acquisition of Gender

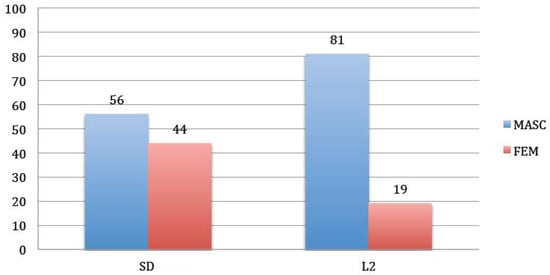

Even though, like SN speakers, L2 learners showed a preference for le with masculine antecedents, there were statistically significant differences between the two groups with respect to the distribution of the gender specification of the clitic antecedents and doubled DPs (χ2(1, N = 327) = 22.45, p = 0.0002). L2 learners had significantly more masculine antecedents and doubled DPs than SN natives and therefore, had a higher frequency of clitics with masculine antecedents than SNs (χ2(8, N = 327) = 28.86, p = 0.000), as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Gender of antecedents and doubled determiner phrases (DPs) of the clitic le in percentages.

It is important to highlight that some of the referents in the story that were meant to elicit feminine DPs, such as la tortuga ‘the.FEM turtle-FEM’ or la rana ‘the.FEM frog.FEM’, were produced sometimes by L2 learners as headed by a masculine determiner as in:

| 25. | Empez-ó | a | morder-le | a-l | ran-it-a |

| begin-PST.3SG | to | bite.INF-CL3.SG | DOM-DET.MSG | frog-DIM-FSG | |

| ‘(He) began to bite the little frog.’ (L2-AP50) | |||||

Notice that in (25), while feminine gender assignment is evidenced by the feminine suffix -a after the diminutive infix -it, the differential object marker shows the masculine form al. This suggests some residual difficulties in gender agreement inside the DP. As we will discuss below, this difficulty affected nouns with congruent gender assignment in Ashaninka and Spanish as well as nouns with non-congruent gender assignment in the two languages.

In terms of the antecedents of anaphoric clitics, SN speakers exhibited, as expected, a slight preference for lo/la (34) over le (32) with almost even numbers for lo for masculine (14) and feminine (15) antecedents and very low numbers for la with feminine (4) and masculine (1) DPs. As corroborated by (χ2(3, N = 86) = 9.7, p = 0.000), the distribution for L2 learners was significantly different with le (76) preferred over lo/la (52). The masculine clitic lo was strongly preferred for masculine referents (38) over feminine (9); the gender-specific la marked feminine (3) over masculine (2).

The following are examples of lo with masculine and feminine antecedents from Spanish-dominant speakers (26 and 27) and examples of le with masculine and feminine antecedents from L2 speakers (28 and 29):

| 26. | Lo + masc | |||||

| Lo | est-á | agarr-ando | ||||

| CL.3.MSG | be-3SG | grab-GERUND | ||||

| ‘(S/he) is grabbing him.’ | ||||||

| (Antecedent: el sapo ‘DET.MSG toad-MSG.’) | ||||||

| 27. | Lo + fem | |||||

| Vuelv-e, | lo | bot-a | ||||

| come back-3SG | CL.3MSG | throw out-3SG | ||||

| ‘Comes back and throws it out.’ | ||||||

| (Antecedent: la rana ‘DET.FSG frog-FSG.’) | ||||||

| 28. | Le + masc | |||||

| Le | met-e | en | la | caj-a | ||

| CL.3SG | put-3SG | PREP | DET.FSG | box-FSG | ||

| ‘He puts him in the box.’ | ||||||

| (Antecedent: el sapo ‘DET.MSG toad-MSG’) | ||||||

| 29. | Le + fem | |||||

| Quer-rá | morderle | no | s-é | |||

| want-FUT-3SG | bite-INF.CL3SG | not | know-1SG | |||

| ‘He might want to bite her; I don’t know.’ | ||||||

We take this to indicate that in this language contact situation, there is a continuum of the assembly of gender features and clitics in oral production that goes from the mapping in anaphoric structures of masculine and feminine features onto lo among the SN speakers to a preference for the unmarked clitic le among the L2 learners who produced a lower number of feminine antecedents overall. This seems to indicate that in this contact situation, the mapping of gender features onto clitics in oral production remained unstable, even among native speakers, but with a higher frequency of anaphoric le, the clitic unmarked for gender, among L2 learners.

Table 7 shows that the distribution of le with feminine antecedents in all structures was slightly lower among L2 learners than amongst SNs and that both the SNs and the L2 learners exhibited low numbers and low percentages of la with feminine antecedents or doubled DPs.

Table 7.

Clitics according to the gender of the antecedent or the doubled DP.

The following examples from L2 learners illustrate the distribution of each clitic with feminine and masculine antecedents or doubled DPs:

| 30. | Le + fem | ||||||

| El | niño | le | mir-a | la | caj-a | ||

| the | boy | CL.3SG | look-3SG | DET.FSG | box-FSG | ||

| ‘The boy looks at the box.’ | |||||||

| 31. | Le + masc | ||||||

| El | niñ-o | le | agarr-a | al | sap-o | ||

| the | boy-MSG | CL.3SG | grab-3SG | DOM-DET.MSG | toad-MSG | ||

| ‘The boy grabs the toad.’ | |||||||

| 32. | Lo + fem | ||||||

| Lo | abr-ió | la | caja | ||||

| CL.3MSG | open-PST-3SG | DET.FSG | box-FSG | ||||

| ‘(S)he opened the box.’ | |||||||

| 33. | Lo + masc | ||||||

| Y | la | tortuga | lo | renieg-a | al | sapo | |

| and | DET.FSG | turtle-FSG | CL.3MSG | scold-3SG | DOM-DET.MSG | toad-MSG | |

| ‘And the turtle scolds the toad.’ | |||||||

| 34. | La + fem | ||||||||

| Se | da cuenta | la | tortuga | más | allá | cuando | el | ||

| REFL.3SG | recognize-3SG | DET.FSG | turtle-FSG | more | there | when | DET.MSG | ||

| dueñ-o | est-aba | ahí | esper-ándo-la | ||||||

| owner-MSG | be-PST.3SG | there | wait-GERUND-CL.3FSG | ||||||

| ‘He recognises the turtle further away when the owner was there waiting for her.’ | |||||||||

| 35. | La + masc | ||||||

| La | ha | gust-a(d)o | el | niñ-o | un | sap-it-o | |

| CL.3FSG | have-3SG | like-PARTIC | DET.MSG | boy-MSG | INDEF.MSG | toad-DIM-MSG | |

| ‘The boy liked a toad.’ | |||||||

| 36. | L’ + fem | ||||||

| L’ | hecho | asust-ar | la | grand-e | |||

| CL.3FSG | do-PST-PARTIC | frighten-INF | DET.FSG | big-SG | |||

| ‘He frightened the big one.’ | |||||||

| 37. | L’ + masc | |||||||

| O | l’ | ha | mat-ado | ahí | ||||

| or | CL.3MSG | have-3SG | kill-PARTIC | there | ||||

| ‘Or he has killed him there.’ | ||||||||

We interpret these results as giving partial support for our second hypothesis in the sense that, while SNs and L2 learners showed unstable patterns of gender feature assignment to clitics, L2 learners showed a higher frequency of the unmarked clitic le in anaphoric contexts than SNs. They also showed a higher frequency of masculine antecedents than SNs, some of which can be attributed to the use of a default masculine determiner inside the DP, as exemplified in (25). Unlike cliticization, which did not seem problematic for either of the two groups, the mapping of gender features onto clitic forms remains subject to some residual variation in both groups in oral production.

3.3. Sensitivity to Thematic Roles

Concerning the third hypothesis, L2 acquirers did not differ from SNs in their sensitivity to thematic roles (χ2(6, N = 331) =3.21, p = 0.784) which indicates they have a similar distribution of preference of le for themes and patients.

Table 8 shows the distribution of clitics according to the theme role. This indicates that L2 Spanish learners showed a slight preference for lo over le in marking theme and also, one instance of the abbreviated form l’ was shown. Both groups did not use the feminine gender specific clitic la for the theme role.

Table 8.

Clitics according to thematic role (theme).

The examples below show the use of le as an enclitic to mark a masculine theme by an L2 acquirer in (38), and in (39), and the anaphoric lo referring to a masculine indefinite determiner by an SN speaker is shown.

| 38. | Le + theme | |||||||

| Este | el | perro | el | niño | está | observándole | ||

| this | DET.MSG | dog-MSG | DET.MSG | boy-MSG | be-3SG | watch-PARTIC-CL.3SG | ||

| ‘Ehem, the boy is watching the dog.’ | ||||||||

| 39. | Lo + theme | |||||||

| Allá | en | mi | pueblo | lo | llama-mos | bals-a | ||

| there | in | POSS | Village-MSG | CL.3MSG | call-1PL | raft-FSG | ||

| ‘There in my village we call it raft.’ | ||||||||

The distribution of clitics according to the patient role is shown in Table 9. In line with the previous result, L2 Spanish learners showed a clear preference for le over lo for the patient role with a lower number for the feminine gender specific la and a slightly higher percentage for the phonologically reduced form l’. SN speakers, on the other hand, exhibited only a slight preference for le over lo to mark the patient role.

Table 9.

Clitics according to thematic role (patient).

The examples below illustrate the use of two preferred clitics to mark the patient role by an L2 learner (40) and by a native speaker (41).

| 40. | Le + patient | |||||||

| La | tortuga | lo | ha | visto | como | le | ha | |

| DET.FSG | turtle-FSG | CL.3MSG | have-3SG | see-PARTIC | how | CL.3SG | have-3S | |

| empujado | ||||||||

| push-PARTIC | ||||||||

| ‘The turtle saw that he had pushed him.’ | ||||||||

| 41. | Lo + patient | |||||||

| Pero | el | sap-o | lo | mat-ó | ||||

| but | DET.MSG | toad-MSG | CL.3MSG | kill-PST.1SG | ||||

| ‘But the toad, I kill him.’ | ||||||||

In the distribution of thematic roles in anaphoric clitics, L2 Spanish learners showed a slightly higher preference for patient over theme roles than SN speakers, although both groups showed a higher frequency of patient roles, probably due to the nature of the actions depicted in the pictures (kick, bite, etc.):

| 42. | a. | SN | |||||||

| Patient (67%) > Theme (33%) | |||||||||

| b. | L2 | ||||||||

| Patient (72%) > Theme (28%) | |||||||||

The scalar systems for the distribution of thematic roles in doubling structures showed differences between both groups.

| 43. | a. | SN | |||||||

| Theme: CLD (23.6%) > CLLD (2.5%) > CLRD (0%) | |||||||||

| Patient: CLD (67.5%) > CLRD (10%) > CLLD (7.5%) | |||||||||

| b. | L2 | ||||||||

| Theme: CLD (23.7%) > CLRD (2.97%) > CLLD (1.98%) | |||||||||

| Patient: CLD (48.51%) > CLLD (21%) > CLRD (1.78%) | |||||||||

These differences, however, do not seem to affect the general preference in both groups for le over lo with both thematic roles. We take these results to be evidence in support of the view that morphological patterns can be acquired (proclitics vs. suffixes) as well as preferences for mapping thematic roles onto le and lo, but subtle differences in the continuum of preferences for mapping gender features are more difficult to acquire.

4. Discussion

The results do not support our first hypothesis. On the contrary, they show evidence of the acquisition of cliticization in the L2 Spanish of Ashaninka speakers with only two tokens of reduplication as an indication of possible residual difficulty with cliticization patterns.5 They indicate that advanced L2 learners do not exhibit residual transfer effects, such as suffixation of internal arguments, and only exhibit minimal evidence of compensatory strategies, such as reduplication, that allow them to mark internal arguments as pre- and post-verbal clitics. If L2 learners had experienced more difficulties in the acquisition of procliticization due to suffixation of internal arguments with inflected verbs in their L1, we would expect reduplication to be more frequent among advanced learners. Notice that, in Example (20), the proclitic and the enclitic are not identical, which leads us to think that the proclitic and the enclitic are not exact copies. Reduplication, rather than an actual process of syntactic copy and deletion (Chomsky 1993), seems to be a way of marking the internal argument of the lower verb in the clause below, even though cliticization has taken place. Of course, further research on this is needed to examine whether L2 learners with lower levels of proficiency exhibit more evidence of this strategy. If we assume that clitics in anaphoric and restructuring contexts are syntactic clitics that involve movement (Kayne 1975; Torrego 1996) and the ones in CLD structures are considered morphological agreement markers in Spanish (Mayer 2017; Sánchez and Zdrojewski 2013; Suñer 1988; Torrego 1998), then L1 Ashaninka–L2 Spanish advanced speakers show evidence in their oral production of having acquired both clitic movement and pre-verbal internal argument marking.

At first glance, these results seem to question the Bottleneck Hypothesis (Slabakova 2008) by challenging the notion that functional morphology, per se, is difficult to acquire. However, we would like to propose that there is an important difference between the acquisition of the morphosyntactic patterns of cliticization and the specification of features with which morphemes are associated. Advanced L2 learners showed ample evidence of procliticization, with inflected verbs and encliticization with non-finite forms used in the input. Our results are consistent with work that has shown evidence of successful acquisition of morphosyntactic patterns, such as clitic climbing (Duffield and White 1999; Pérez-Leroux et al. 2011). This supports the view that the acquisition of cliticization as a syntactic property is not affected by the lack of such processes in the L1 or by the existence of different morphological patterns.

Concerning the second hypothesis, according to which the assembly of gender features and the morphosyntactic properties of clitics should generate difficulties in L2 acquisition, our hypothesis was confirmed, although the answer to our research question was more complex than anticipated. The SN data revealed a situation in which SN speakers who serve as sources of input for L2 learners showed some instability in the gender marking of clitics, although they showed a scalar system, whereby le > lo > la. L2 learners also revealed a similar scalar system. L2 learners had higher levels of masculine antecedents in their overall production and evidence of masculine determiners with feminine nouns. This happened with non-congruent nouns in the L1 and the L2, such as mashero ‘toad’ (non-masculine) and sapo ‘toad’ (masculine), and even with nouns with congruent gender assignment, such as pirinto, obanto ‘frog’ (non-masculine in Ashaninka), and rana ‘frog’ (feminine in Spanish). These results do not support simple cross-language gender matching based on differing gender defaults in both languages. Similar to Spanish in contact with Quechua and Shipibo, which are both languages without gender (Mayer and Sánchez 2016, 2017), L1 Ashaninka–L2 Spanish learners’ data also showed a higher frequency of le unmarked for gender as anaphoric clitics than SN data. However, in doubling structures, L2 learners showed higher percentages of lo with masculine DPs than with feminine ones in comparison with SN speakers. This could be attributed to the higher percentage of masculine DPs in their narratives. Our findings are consistent with the evidence from previous L2 and L1 studies that have attributed difficulty with gender assignment to difficultygenerating a new lemma (Jiang 2000, p. 51) with the gender feature specification of nouns in the L2 (Franceschina 2001; Kirova 2016). Lemmas harbor the relevant semantic and syntactic specifications belonging to the phonetic form. It is possible that such specific grammatical information may be part of L2 learners’ lexical knowledge but not yet of their lexical competence6. L2 learners may be located at an intermediate stage where they match the L2 lexical form with the L1 lemma information, which usually lacks the language-specific morphological information of the L2 lexical item. In fact, it is also possible to conceive that the activation of the L1 lemma information may sometimes block the activation of the L2 lemma in production. In a context of language contact, SNs, despite being native speakers, may also experience some degree of variation when extracting, processing and integrating the syntactic, semantic and specific morphological information of a word with its concept that affects the mapping of gender features onto clitics. As mentioned in the introduction, evidence for this difficulty with third person clitics has also be found in French L1 monolingual acquisition (Delage et al. 2016).

No sensitivity to thematic roles was found in the distribution of anaphoric clitics, as shown in the scalar systems in (42) providing no evidence to support our third hypothesis. This could be because differences in internal argument marking between themes and patients in Ashaninka only take place in ditransitive structures and our data was limited to transitive structures. In doubling structures, CLD structures had higher percentages of patients than of themes in both groups (43). Numbers for the other doubling structures were too low for any meaningful comparisons to be drawn.

Overall, our findings suggest that among advanced L2 learners living in a contact situation, differences in morphological markings in the L1 and syntactic cliticization in the L2, and differences in thematic role sensitivity for internal argument marking, do not generate long-lasting, residual effects. On the other hand, the assembly of gender features with functional elements, such as clitics, which are at the interface of the lexicon, syntax, and morphology, reveal long-term, residual difficulties for L2 acquisition and could remain somewhat variable even among native speakers living in that same contact situation. We take this to indicate that the acquisition of morphological templates, per se, is not the main stumbling block for L2 acquisition. The mapping of features onto morphology that requires the formation of new lemmas in the L2 may be affected by blocking, which results in default masculine assignment to functional categories related to argument structure, even when the nouns heading the argument antecedent or the doubled argument are congruent in gender in the L1 and the L2. Further research is needed to determine the extent to which Spanish L2 speakers with low proficiency in Ashaninka, which was not tested here (a limitation of this study), and high proficiency in Spanish exhibit different patterns in gender marking.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Ashaninka communities and Caleb Cabello Chirisente and Nila Vigil Oliveros for access to the communities as well as Carolina Rodríguez Alzza in assisting with the transcription of the Ashaninka bilingual data. Finally, we would also like to thank three anonymous reviewers for their very valuable feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Instruments and materials used in this study.

____________________________________________________________________

- Oral narration of the Frog story (Mayer and Mayer 2003; adapted by Sánchez 2003)

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

- Ethnobiographic interview questions

___________________________________________________________________

Only for official use Questionnaire# ___

Project: “Case-marking and argument structure in Spanish in contact with Andean and Amazonian languages”

Questionnaire

Instructions:

Please answer the following questions as sincerely as possible. In some cases, you are asked to mark an x next to the appropriate answer; in others, you are asked to provide a brief answer. If there are questions that do not apply to you, please leave them in blank. The questionnaire is two pages long.

Bio Information

1. Initials _______

2. Age _________

3. Sex ________

4. Country and city of birth: ___________________________

Level of study

1. Elementary ____ Secondary ____ Technical or vocational ____College ____

2. Years of college studies

(please circle: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th Postgraduate)

3. Mayor: ____________________________________________________

4. Undecided (You may write a provisory major)

____________________________________________________________

Languages

Before answering, read the following:

Mother tongue is the language that you are exposed to and speak from when you are born until you are three years old. You may not be proficient in that language, but it is your mother tongue.

1. To which language were you exposed (languages you spoke) from 0–3?

____________________________________________________________________

2. Which language have you spoken since you were 3?

____________________________________________________________________

3. Were you exposed to other languages (other than your mother tongue) from 3–12? Which one(s)?

____________________________________________________________________

4. Mark where: (a) At home____ (b) In school____ (c) Another context_____________

5. Which language did you speak from 3 to 12?

____________________________________________________________

6. Mark where: (a) At home_____ (b) In school_____ (c) Another context_________

7. Which language do you consider to be your mother tongue (spoken from 0–3)?

___________________________________________________________________

8. Which language do you consider to be your second language? (the one you spoke and were addressed in after the age of 3).

____________________________________________________________________

9. Indicate the languages that you speak in the following situations:

a. At home _____________________________________________

b. At work _____________________________________________

c. With family and friends_________________________________

11. What do you think of

a. Speaking only Spanish

b. Speaking only Asháninka

c. Speaking Asháninka and Spanish

12. Do you think that Asháninka is appreciated in Peru?

__ Agree __Partially agree ___Disagree

Thanks for participating

____________________________________________________________________

- Spanish language proficiency test

____________________________________________________________________

Prueba de dominio (Proficiency test)

Va a escuchar unas oraciones y le voy a dar varias palabras. O, lea las oraciones abajo y escoja la que le parece mejor para cada oración.

Ejemplo:

O. Abrió la ventana y miró: en efecto, mucho _________________ salía de las casas.

a. zorro b. serpiente c. cuero d. fuego

1. Al oír del accidente de su amigo, Paco se puso _____________________.

a. alegre b. cansado c. hambriento d. triste

2. Aquí está tu café, Juanito. No te quemes, que está muy ___________________.

a. dulce b. amargo c. agrio d. caliente

3. Al romper los anteojos, Juan se asustó porque no podía __________________ sin ellos.

a. discurrir b. oír c. ver d. entender

4. ¡Pobrecita! Está resfriada y no puede ________________________________.

a. salir de casa b. recibir cartas c. respirar con dificultad d. leer las noticias

5. Era una noche oscura sin __________________.

a. estrellas b. camas c. lágrimas d. nubes

6. Para saber la hora, don Juan miró el _____________________.

a. calendario b. bolsillo c. estante d. reloj

7. Nos dijo mamá que era hora de comer y por eso ____________________________.

a. fuimos a nadar b.nos sentamos c. comenzamos a fumar d. nos acostamos pronto

8. ¡Cuidado con ese cuchillo o vas a _________________________ el dedo!

a. cortarte b. torcerte c. comerte d. quemarte

9. Sus amigos pudieron haberlo salvado, pero lo dejaron ______________________.

a. ganar b. parecer c. morir d. acabar

10. A la mujer no le gustó el cambio de domicilio pues no le gustaba _____________.

a. callejear b. el puente c. esa estación d. ese barrio

____________________________________________________________________

References

- Abney, Steven. 1987. The English noun phrase in its sentential aspect. Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, June 8. [Google Scholar]

- Abramsson, Niclas. 2003. Development and Recoverability of L2 Codas: A Longitudinal Study of Chinese-Swedish Interphonology. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 25: 313–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Avery D. 2007. The major functions of the noun phrase. In Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Edited by Timothy Shopen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 132–223. [Google Scholar]

- Belloro, Valeria. 2007. Spanish Clitic Doubling: A Study of the Syntax-Pragmatics Interface. Ph.D. dissertation, State University of New York, New York, NY, USA, October 26. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1993. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In The View from Building 20: Essays in Linguistics in Honor of Sylvain Bromberger. Edited by Ken Hale and Samuel J. Keyser. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cuza, Alejandro, Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux, and Liliana Sánchez. 2013. The role of semantic transfer in clitic drop among simultaneous and sequential Chinese-Spanish bilinguals. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 35: 93–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalrymple, Mary, and Irina Nikolaeva. 2011. Objects and Information Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delage, Hélène, Stephanie Durrleman, and Ulrich H. Frauenfelder. 2016. Disentangling sources of difficulty associated with the acquisition of accusative clitics in French. Lingua 180: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryer, Matthews S. 1986. Primary objects, secondary objects, and antidative. Language 62: 808–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, Nigel, and Lidia White. 1999. Assessing L2 knowledge of Spanish clitic placement: Converging methodologies. Second Language Research 15: 133–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschina, Florencia. 2001. Morphological or syntactic deficits in near-native speakers? An assessment of some current proposals. Second Language Research 17: 213–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freynik, Suzanne, Kira Gor, and Polly O’Rourke. 2017. L2 processing of Arabic derivational morphology. The Mental Lexicon 12: 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, Theres. 2005. Comprehension and production of French object clitics by child second language learners and children with specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics 26: 363–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, James. 1995. The morphology of Spanish clitics. In Evolution and Revolution in Linguistic Theory. Edited by Héctor Campos and Paula Kempchinsky. Washington: Georgetown University Press, pp. 168–97. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Roger, and Florencia Franceschina. 2004. Explaining the acquisition and non-acquisition of determiner-noun gender concord in French and Spanish. In The Acquisition of French in Different Contexts: Focus on Functional Categories. Edited by Philippe Prévost and Johanne Paradis. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 175–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul J., and Sandra A. Thompson. 1980. Transitivity in grammar and discourse. Language 56: 251–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackendoff, Ray. 1990. Semantic Structures. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Isabel N., Roumyana Slabakova, and Marit Westergaard. 2017. The Bottleneck Hypothesis in second language acquisition: A study of L1 Norwegian speakers’ knowledge of syntax and morphology in L2 English. In Proceedings of the 41st Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Maria LaMendola and Jennifer Scott. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 333–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Nan. 2000. Lexical representation and development in a second language. Applied Linguistics 21: 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayne, Richard S. 1975. French Syntax. The Transformational Cycle. Current Studies in Linguistics Series; Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kirova, Alena. 2016. Lexical and Morphological Aspects of Gender and Their Effect on the Acquisition of Gender Agreement in Second Language Learners. Ph.D. dissertation, The State University of New Jersey, Rutgers, NJ, USA, January. [Google Scholar]

- Lardiere, Donna. 1998. Dissociating syntax from morphology in a divergent L2 end-state grammar. Second Language Research 14: 359–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lardiere, Donna. 2005. On morphological competence. In Proceedings of the 7th Generative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition Conference (GASLA 2004). Edited by Laurent Dekydtspotter, Rex A. Sprouse and Audrey Liljestrand. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 178–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Elisabeth. 2017. Spanish Clitics on the Move, Variation in Time and Space. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Mercer, and Marianna Mayer. 2003. One Frog too Many. New York: Puffin. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, Elisabeth, and Liliana Sánchez. 2016. Object agreement marking and information structure along the Quechua-Spanish contact continuum. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics 29: 544–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Elisabeth, and Liliana Sánchez. 2017. Variability at the interfaces: Clitics in Bilingual and Monolingual Andean Spanish. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihas, Elena. 2010. Essentials of Ashéninka Perené Grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA, December. [Google Scholar]

- Mihas, Elena. 2015. A Grammar of Alto Perené (Arawak). Mouton Grammar Library. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvina. 2001. First-language-constrained variability in the second-language acquisition of argument-structure-changing morphology with causative verbs. Second Language Research 17: 144–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, Åshild. 2004. What markedness marks: The markedness problem with direct objects. Lingua 114: 1186–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, Francisco, and Lori Repetti. 2006. Stressed enclitics. In New Analyses in Romance Linguistics: Phonetics, Phonology and Dialectology. Edited by Jean-Pierre Y. Montreuil. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 167–81. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, David L. 1981. Phonology and Morphology of Axininca Campa. SIL Publications in Linguistics, 66. Dallas: SIL and University of Texas at Arlington. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, Judith. K., and David L. Payne. 2005. The pragmatics of split intransitivity in Ashéninka. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Etnolingüısticos 10: 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Leroux, Ana Teresa, Alejandro Cuza, and Danielle Thomas. 2011. Clitic placement in Spanish–English bilingual children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 14: 221–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienemann, Manfred. 1998. Language Processing and Second Language Development: Processability Theory. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, Judy, and David L. Payne. 1986. Asheninka (Campa) pronominals. In Pronominal Systems. Edited by Ursula Wiesemann. Tübingen: Günther Narr Verlag, pp. 323–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin, Laura, Laurie A. Stowe, and Ger J. de Haan. 2006. Transfer effects in learning a second language grammatical gender system. Second Language Research 22: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2003. Quechua-Spanish Bilingualism. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Liliana. 2015. Convergence in feature mapping: Evidentiality, Aspect and nominalizations in Quechua-Spanish bilinguals. In Sociolinguistic Change Across the Spanish-speaking World: Case Studies in Honor of Anna Maria Escobar. Edited by Kim Potowski and Talia Bugel. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Liliana, and Pablo Zdrojewski. 2013. Restricciones semánticas y pragmáticas al doblado de clíticos en el español de Buenos Aires y de Lima. La variación en la gramática del español actual. Lingüística 29: 271–320. [Google Scholar]

- Slabakova, Roumyana. 2008. Meaning in the Second Language. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Slabakova, Roumyana. 2009. Features or parameters: Which one makes second language acquisition easier, and more interesting to study? Second Language Research 25: 313–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabakova, Roumyana. 2013. What is easy and what is hard to acquire in a second language: A generative perspective. In Contemporary Approaches to Second Language Acquisition. Edited by M María del Pilar García Mayo, María Juncal Gutiérrez Mangado and María Martínez-Adrián. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Andrew, and Ana R. Luís. 2012. Clitics. An Introduction. Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suñer, Margarita. 1988. The role of agreement in clitic-doubled constructions. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 6: 391–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrego, Esther. 1996. On the nature of clitic doubling. In Evolution and Revolution in Linguistic Theory. Edited by Héctor Campos and Paula Kempchinsky. Washington: Georgetown University Press, pp. 399–418. [Google Scholar]

- Torrego, Esther. 1998. The Dependencies of Objects. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zwicky, Arnold M. 1985. Clitics and Particles. Language 61: 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | We use the following abbreviations: A = agent, CL = clitic, DEM = demonstrative. DET = determiner, DIM = diminutive, DIR = directional, DOM = differential object marking, DP = determiner phrase, EP = epenthetic, F/FEM = feminine, FOC = focus, FUT = future tense, GERUND = gerund, INDEF = indefinite, INF = infinitive, LOC = locative, M = masculine, NM = non-masculine, NOM = nominative, O = object, 1 = first person, 3 = third person, PARTIC = participle, PERF/PFV = perfective, PL = plural, POSS = possessive, PREP = preposition, PRO = pronoun, PST = past tense, R = recipient, REAL = Realis, REFL = reflexive, REL = relativizer, S = intransitive subject, SG = singular, STAT = stative, T = Theme, TOP = topic, PST = past tense. |

| 2 | We use the term DP as per the DP-hypothesis (Abney 1987) in the generative framework. It is usually labeled NP in other frameworks. |

| 3 | We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for bringing the stressed nature of accusative clitics in Rioplatense Spanish clitic clusters to our attention. |

| 4 | The verbal form está cargado is a form of past tense found also in other contact varieties of Spanish in Peru (Sánchez 2015). |

| 5 | Although clitic reduplication might be the result of residual L1 representations, it has also been attested in monolingual Spanish in non-contact varieties, as mentioned by an anonymous reviewer. |

| 6 | While speakers may have the ability to receptively associate lexemes and lemmas, which we understand as exhibiting knowledge of a word, lexical competence here is understood as the ability to activate words and associate lexemes and lemmas for receptive and productive tasks in a target manner. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).