Abstract

The focus in this corpus-based study is on a set of Spanish constructions formed with the verb of visual perception, ver ‘to See’, and a predicate adjective or participle. In addition to a clearly recognizable transitive schema, the set includes various instances featuring a reflexive clitic pronoun coreferential with the subject, some of which have been argued to evidence the grammaticalization of lexical ver into a univerbated semicopular verb (pronominal verse), meaning little more than ‘be’ in some examples, and proximate to the intransitive sense of English look in other cases. We trace the evolution of these constructions in data spanning the history of the Spanish language, from its recorded beginnings to the present. We establish the need to distinguish two constructional sources of change, namely, an old middle-reflexive and a younger reflexive passive. We draw attention to the “renewal” of the Latin deponent videri ‘appear, look, seem’, which can be said to have taken place in Spanish as a product of the passive-derived process of grammaticalization undergone by ver. And throughout the paper we address problems of analyzability, attributable to the superficially identical strings of words that characterize the constructional patterns with a reflexive morpheme.

1. Introduction

Spanish possesses a set of constructions in which the verb ver ‘to see’ co-occurs with a predicate participle or adjective. Some instances show a transitive clause, but many others contain a reflexive pronoun coreferential with the subject. Given the well-known multifunctionality of reflexive morphemes in Spanish, the constructions of interest have generated divergences and uncertainties regarding the correct analysis of their underlying structure.

The transitive schema is less problematic. It features a typically human subject, a direct object of animate or inanimate reference, and the predicate participle or adjective agreeing in number and gender with the object. Here, scholars debate whether the adjectival predicate functions as an (optional) adjunct or a (selected) object complement (Demonte & Masullo, 1999; NGLE, 2009, §38.7; Rodríguez Espiñeira, 2000, 2006):

| (1) | a. | Vi | a Ángela | dormida. | ||

| see.1sg.pfv | dom Ángela | sleep.ptcp.f.sg | ||||

| ‘I saw Ángela asleep.’ (Rodríguez Espiñeira, 2006, p. 119) | ||||||

| b. | No | veo | claras | sus | intenciones. | |

| not | see.1sg.prs | clear.f.pl | poss.pl | intention.f.pl.acc | ||

| ‘I don’t see his/her intentions being clear.’ (NGLE, 2009, §38.7h) | ||||||

Additionally, ver and the predicate participle or adjective appear in a variety of constructional patterns, which have in common the presence of a reflexive marker. As is known, in Spanish, and in other Romance languages, the original reflexive pronoun inherited from Latin evolved into a multifunctional type of clitic, serving to indicate pure reflexivity, to encode voice alternations—middle, passive, impersonal—and to create so-called “pronominal” verbs, lexical or grammatical units, in which the reflexive is integrated as a morphological component (see Sánchez López, 2002). This explains the distinct analyses the constructional patterns of ver have motivated, depending on their use.

- A reflexive clause:

| (2) | En este espejo | me | veo | borrosa. |

| in this mirror | refl.1sg | see.1sg.prs | blurry.f.sg | |

| ‘In this mirror I see myself blurry.’ (Morimoto & Pavón Lucero, 2007, p. 61) | ||||

- A complex predication, with a not fully grammaticalized semicopular verb, whose meaning retains a lexical feature of ‘perception’ akin to feel:

| (3) | Lucía | se | vio | obligada | a dejar su trabajo. |

| Lucía.nom | refl.3sg | see.3sg.pfv | oblige.ptcp.f.sg | to leave her job | |

| ‘Lucía felt/was obliged to leave her job.’ (NGLE, 2009, §38.5p) | |||||

- A construction favoring participles of change-of-state verbs (NGLE, 2009, §38.5p) and considered to be functionally equivalent (Yllera, 1980, p. 271) to the Spanish periphrastic passive (ser ‘be’ + past participle):

| (4) | La cantidad esperada | se | vio | multiplicada |

| the amount expected.f.sg.nom | refl | see.3sg.pfv | multiply.ptcp.f.sg | |

| por tres | ||||

| by three | ||||

| ‘The expected amount was multiplied by three.’ (NGLE, 2009, §38.5p) | ||||

- The expression of a state with a semicopular pronominal unit (verse ‘be’):

| (5) | De pronto | se | vio | rodeado | de toros bravos. |

| suddenly | refl | see.3sg.pfv | surround.ptcp.m.sg | by brave bulls | |

| ‘Suddenly he was surrounded by brave bulls.’ (DEUM, 1996, s.v. ver) | |||||

- A construction displaying another pronominal verse of semicopular character, whose meaning approximates that of English look:

| (6) | a. | El edificio | se | veía | ruinoso. | ||

| the building.m.sg.nom | refl | see.3sg.ipfv | ruinous.m.sg | ||||

| ‘The building looked ruinous.’ (Morimoto & Pavón Lucero, 2007, p. 62) | |||||||

| b. | ¡Te | ves | estupenda! | ||||

| refl.2sg | see.2sg.prs | marvellous.f.sg | |||||

| ‘You look great!’ (Morimoto & Pavón Lucero, 2007, p. 62) | |||||||

The corpus-based diachronic study carried out in the present work seeks to shed light on how this intricate network of structures and meanings developed over time. Anticipating the results of our research, we should mention that the historical evidence led us to separate constructions evolved out of the reflexive variant of the transitive clause, from those that link back to an original passive clause. The changes that took place in these two domains—two grammatical clines—belong to different epochs, relatively early in the first case, and much later in the second.

The mechanisms of change, too, turned out to be different. A process of analogical attraction between ver ‘see’ and hallar ‘find’, as we will argue, was involved in the development of semicopular verse ‘be’, whose source was the reflexive clause. On the other hand, the semicopular verse ‘look’ was the product of the elimination of the implicit experiencer of the passive clause from the conceptual structure of the predication—a product consonant with an apparent revival of the Latin deponent videri, as we will discuss.

Nevertheless, although the paths of evolution were distinct, their outputs converged in the rise of a grammaticalized semicopula, through the reanalysis of a sequence of two elements—a clitic and a lexical verb—into a single morphological unit (verse).

This said, we have to admit that the real usage data pose a serious challenge to the task of the analyst. In contrast to other processes of grammaticalization treated in the literature, the recategorized verse occurs in structures very similar to those in which the verb of perception continues to hold on to its lexical status. As time progresses, the problems of “analyzability”, understood as the degree to which the individual components of a structure are recognized (Amaral & Delicado Cantero, 2022, pp. 27–28), grow more acute because successive waves of change have given shape to a phenomenon of multiple “layering” (Hopper, 1991), and careful inspections of the discourse contexts are required to discern between syntactic patterns and semantic relations. This raises the question of how language users deal with the ambiguities. Our intention is to propose that successful communication does not critically rely on a full and adequate segmentation of sentence structures (cf. Pijpops & Van de Velde, 2016).

2. Materials and Methods

The dataset for this diachronic study was compiled from the electronically available Corpus Diacrónico del Español (CORDE), Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual (CREA), and Corpus del Español del Siglo XXI (CORPES XXI). The forms of Spanish ver we searched for, taking into account orthographic variations, were the first- and second-person singular and the third-person singular and plural, in three tenses of the indicative, namely, present, imperfect, and perfect past. The data obtained from this preliminary search—both with and without a reflexive morpheme—were then manually inspected to extract the relevant tokens of constructions that included a predicate participle or adjective.1

The dataset is intended to cover the recorded history of Spanish with examples pertaining to different centuries: 13th, 15th, 17th, 19th, and transition 20th–21st. Periods of five years were established for the samples preceding the contemporary phase of the language (1276–1280, 1476–1480, 1676–1680, 1876–1880, respectively). The original aim was to obtain a selection of approximately 200 constructional data, representative of each period. As it turns out, in all cases, either to complete the registers, or to ensure a diversity of genres, we retrieved data from additional texts.2 Finally, given the high number of documents gathered in CREA (20th century) and CORPES (21st century), for the exemplification of the contemporary phase we arbitrarily selected two years: 1975 and 2005.

The results of our search yielded a total of 1377 constructional tokens involving the Spanish verb ver ‘see’ and a predicate participle or adjective. Of these, 215 belong to the 13th century, 218 to the 15th century, 212 to the 17th century, 317 to the 19th century, and 415 to the transition period between the 20th and 21st centuries.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Transitive Construction

We begin our diachronic study with a brief discussion of the transitive construction, well documented from the earliest recordings of the Spanish language up to present day. As stated in the introduction, the transitive contains a human subject, in the role of a semantic experiencer, an animate or inanimate direct object, and a predicate adjective or adjectival participle agreeing in gender and number with the direct object.

| (7) | a. | quando | uio | abiertas | las puertas | de la carcel, | |||||

| when | see.3sg.pfv | open.ptcp.f.pl | the door.f.pl.acc | of the prison | |||||||

| saco el cuchillo e queries matar | |||||||||||

| ‘when he saw the doors of the prison open, he drew his knife and wanted | |||||||||||

| to kill himself’ | |||||||||||

| (1260, El Nuevo Testamento, corde) | |||||||||||

| b. | si | á | V. M. | le | ven | inclinado | |||||

| if | dom | Your Majesty | you.dat | see.3pl.prs | incline.ptcp.m.sg | ||||||

| al remedio de aquellos reynos | |||||||||||

| to.the remedy of those kingdoms | |||||||||||

| ‘if they see Your Majesty as being inclined toward the remedy | |||||||||||

| of those kingdoms’ | |||||||||||

| (1685, Gabriel Fernández de Villalobos, Desagravios de los indios, corde) | |||||||||||

| c. | quien más sufría esa venganza era yo, | porque | Milagros | ||||||||

| because | Milagros.nom | ||||||||||

| lo | veía | natural | |||||||||

| it.acc | see.3sg.ipfv | natural | |||||||||

| ‘the one who suffered that revenge the most was me, because Milagros | |||||||||||

| saw it as natural’ | |||||||||||

| (2005, Elvira Lindo, Una palabra tuya, corpes) | |||||||||||

Spanish sentences of this type have been examined in connection with the topic of “secondary predicates”, and controversy has hinged on whether the co-predicate should be analyzed as an (optional) adjunct or an (obligatory) object complement (Demonte & Masullo, 1999; NGLE, 2009, §38.7; Rodríguez Espiñeira, 2000, 2006). When cognitive verbs like considerar ‘examine, study’, estimar ‘esteem, respect’, or juzgar ‘judge’ appear in this pattern, the consensus is that an indissoluble relationship holds between the predicating complement and the verb, whose meaning is altered.3 Regarding ver ‘see’, however, opinions are more hesitant, precisely in view of the fact that the verb of visual perception conserves its basic sense in many cases (Demonte & Masullo, 1999, p. 2485; Rodríguez Espiñeira 2000, p. 60). This has motivated a proposal to distinguish two instantiations of the transitive schema: one in which ver denotes a visual experience and the participle or adjective is an adjunct predicate, as in (7a), and another, in which ver evokes a perception of mental character, as in (7b–7c), and joins the cognitive verbs in forming a clause with a participle or adjective functioning as an object complement (NGLE, 2009, §38.7h).4

In relation to this proposal, two observations are in order. First, the dual semantic behavior of ver is not limited to the transitive concerned. From Latin videre, its ancestor, Spanish ver has inherited the ability to move between the domain of physical sight and that of mental perception in many of its uses (e.g., Gaffiot, 1934, s.v. video), via a metaphorical mapping that is recurrent cross-linguistically (Sweetser, 1990).

Second, from a discursive point of view, it is not clear that the alleged optional vs. obligatory status of the adjectival predicate with ver has a bearing on how we interpret the message conveyed by the construction. Independently of whether ver keeps its visual meaning or displays a more cognitive/evaluative sense, the essential information of the clause appears to be contained in the participle or adjective.

As Boye and Harder (2007, 2012) have argued, when two predicating elements converge in a sentence, they compete for attention and set up a scenario in which the structurally secondary predicate may gain “primary discourse prominence”. The criterion of “addressability” discussed by the authors may help to illustrate what we are suggesting for the transitive construction under study; the natural reaction to the utterance Vi a María más flaca ‘I saw Mary more skinny’ will not be “when did you see her?” or “where did you see her?”, but rather “Skinnier? You’re worrying me. She isn’t ill, is she?” or something along these lines. Although the main verb continues to report a visual experience, the information it carries is backgrounded—to variable degrees dependent on the context (Boye, 2023)—in relation to the other predicate.

Significantly, according to Boye & Harder, the tendency of a verb to assume such an ancillary status in a specific type of construction, on a regular basis, prepares the ground for a potential process of grammaticalization to be suffered at a later date. Our diachronic study will give us the opportunity to verify this claim.

In the transitive construction with ver, the discursively prominent predicate tends to appear in the form of a past participle which expresses a resultative state. The nature of the state may be physical (armado ‘armed’, cansado ‘tired’, muerto ‘dead’, in relation to human beings, alumbrado ‘lit’, cortado ‘cut’, podrido ‘rotten’, with inanimate objects) or mental (afligido ‘distressed’, enojado ‘irritated’, preocupado ‘worried’); it may also refer to a broadly defined social condition (casado ‘married’, desposeído ‘dispossessed’, vencido ‘defeated’) or may indicate some kind of spatial relation (caído ‘fallen’, encerrado ‘locked up’, sentado ‘seated’). Adjectives suitable to designate an individual-level type of predication (alto ‘tall’, sabio ‘wise’, piadoso ‘pious’) are highly limited in their occurrences throughout the history. Depending on the nature of the denoted state, the lexical verb refers to a visual experience (‘see’) or evokes an inferential kind of mental perception (‘consider’). In addition, the transitive construction occasionally exhibits an evaluative adjective (‘hermoso ‘beautiful’, malo ‘bad’, igual ‘alike’), which has the effect of triggering a more subjective interpretation of ver (‘regard, deem’).

The ability to cover this range of semantic nuances was passed on from Latin videre to Spanish ver, as the following examples confirm:5

| (8) | a. | ut | desertum | tumulum | videt | |||||

| when | deserted.acc.m.sg | hill.acc.m.sg | see.3sg.prs | |||||||

| ‘when he saw the hill deserted’ (Liv. 31,42,9) | ||||||||||

| b. | Hannibalem | et | virtute | et | fortuna | superiorem | ||||

| Hannibal.acc | and | valor.abl | and | fortune.abl | high.comp.acc | |||||

| videt | ||||||||||

| see.3sg.prs | ||||||||||

| ‘he now sees Hannibal is his superior both in valor and fortune’ (Liv. 22,29,2) | ||||||||||

| c. | cum | sua […] | numina | laesa | uidet | |||||

| when | pos.pl | godhead.acc.n.pl | hurt.ptcp.acc.n.pl | see.3sg.prs | ||||||

| ‘when she sees […] her godhead wronged’ (Ov. Ep. 20,100) | ||||||||||

Over time, the use of transitive ver with abstract objects (deseo ‘wish’, eternidad ‘eternity’, honor ‘honor’, idea ‘idea’) and modal adjectives (difícil ‘difficult’, necesario ‘necessary’, probable ‘likely’) rises somewhat. But the predominance of stative predicates suggesting a degree of perceptible evidence remains stable.6

In sum, the oldest “layer” (Hopper, 1991) in the functional domain we are concerned with embraces the transitive construction, descending from Latin and still in force. Crucial to our understanding of what follows is the fact that the predicate participle or adjective tends to have primary discourse prominence, at the expense of the backgrounded lexical verb.

3.2. The Middle-Reflexive Construction and Grammaticalized Verse ‘Be’

3.2.1. Lexical Uses of Middle-Reflexive Ver

In this section we turn to the construction built with an animate, typically human, subject, in the experiencer’s role, a predicating participle or adjective, and an unstressed reflexive pronoun—a reflexive clitic7—coreferential with the subject. As these early examples illustrate, the experiencer takes note of his or her presence in a certain state:

| (9) | a. | se non entendien unos a otros & | se | ueyen | assi | |||

| refl.3pl | see.3pl.ipfv | so | ||||||

| demudados | ||||||||

| alter.ptcp.m.pl | ||||||||

| ‘they did not understand one another and thus felt bewildered’ | ||||||||

| (1280, Alfonso X, General Estoria. Cuarta parte, corde) | ||||||||

| b. | & pues que | se | el | uio | bien | apoderado | ||

| and after that | refl.3sg | he | see.3sg.pfv | well | empower.ptcp.m.sg | |||

| dio tornada pora Meca | ||||||||

| ‘and when he realized he was well empowered, he turned back toward Mecca’ | ||||||||

| (1270, Alfonso X, Estoria de Espanna, corde) | ||||||||

The origin of the construction goes back to Latin, where the reflexive analysis of the clause was supported by the distinction between the nominative subject and the accusative object, with which the adjectival predicate agreed:

| (10) | se | classe | hostium | circumfusos | videbant |

| refl.acc.pl | fleet.abl | enemy.gen | surround.ptcp.acc.pl | see.3pl.ipfv | |

| ‘they saw themselves surrounded by the enemies’ fleet’ (Cic. Tusc. 3, 66) | |||||

As compared to (10), the examples in (9) are less clear, because the predicate participle or adjective in Spanish no longer carries an accusative marker, and even in authentically reflexive clauses it is taken to agree with the (nominative) subject (Suárez Fernández, 1997, p. 141).8 In fact, the identification of “pure” reflexive clauses in Spanish constitutes a known problem (Benito Moreno, 2015, chap. 1; Sánchez López, 2002, pp. 72–79; Suárez Fernández, 1997, pp. 132–143). The formal device employed to verify reflexivity resides in checking whether the clause admits the emphatic phrase a sí mismo ‘himself’. When it does not, as it happens in multiple cases, a “middle voice” interpretation is proposed in some studies. On this view, the split representation of a single referential entity, characteristic of the reflexive clause, gives way to a more holistic construal, in which the subject initiates the designated verbal process and is simultaneously affected by it (Kemmer, 1993; Maldonado, 1999). At the syntactic level, the middle analysis implies that the reflexive clitic, stripped of its argumental function, converts into a kind of voice marker.

It is not easy to determine which analysis better fits the construction under study. The tendency among scholars has leant towards the reflexive option (Benito Moreno, 2015, p. 35, and references therein). Evidently, when the clause pictures a reflection of self (En este espejo me veo borrosa ‘In this mirror I see myself fuzzy’), it is the correct reading. But such cases are exceptions in real usage data. Generally, as suggested by various authors, a middle analysis is more adequate (Fernández Ramírez, 1986, p. 409; Suárez Fernández, 1997, p. 142; Yllera, 1980, p. 270). This is the position we have adopted in the present work.

As expected, the middle clauses from our corpus encompass participles or adjectives related to those found in the transitive constructions with an animate direct object: physical states (cansado ‘tired’, preñada ‘pregnant, harto ‘satiated), mental states (desesperado ‘desperate’, triste ‘sad’, enamorado ‘in love’, espantado ‘frightened’, sorprendido ‘surprised’), social conditions (cercado ‘besieged’, preso ‘imprisoned’, viudo ‘widowed’, socorrido ‘assisted’, acosado ‘harassed’), and spatial relations (encerrado ‘locked up’, rodeado ‘surrounded (by)’, ayuntados ‘gathered’, solo ‘alone’, tumbado ‘lying down’). Instances of all four semantic categories are registered from the earliest available examples up to the present.9 When processed as a middle construction, the sense of the lexical verb ver ‘see’ oscillates between eliciting a sensory experience or a more cognitive one, in accordance with the semantics of the predicated state. That is, in some cases, middle ver comes close to meaning ‘to feel’—verse desesperado, triste or arrepentido is to ‘feel’ despair, sadness, or remorse—whereas other predicates stimulate the idea of something being brought into one’s consciousness, as when the subject ‘realizes’ that he has been fatally wounded (se vio ferido de muerte), lost a battle (se vieron perdidos), or secured a position of power (se vio apoderado).

Our textual sources suggest that the middle construction with a predicate participle or adjective moved along a path of progressive entrenchment, yielding fewer tokens corresponding to the 13th century and manifesting a growth in productivity towards the end of the Middle Ages.10

3.2.2. Univerbation and Grammaticalization: Verse ‘To Be’

In the course of time, however, something happened to the middle construction, whereby these meanings were no longer recognized or were blurred. Support for the change comes from the 1780 edition of the Diccionario de la Lengua Española (‘Dictionary of the Spanish Language’),11 published by the Royal Spanish Academy where a special subentry of ver is introduced and defined in the following terms:

| (11) | verse. Hallarse constituido en algun estado; como: VERSE pobre, abatido, &c. |

| Esse, constitui. | |

| ‘verse. To find oneself constituted in some state; as: VERSE poor, depressed, etc. | |

| Be, be constituted’. |

The definition goes beyond putting on record another meaning of the verb of perception; it establishes the existence of a new coinage, a pronominal unit (verse), similar to hallarse ‘find oneself’ and equated with the Latin copula esse.

To gain insight into the change, we decided to execute a detailed comparative study of ver and hallar, whose results can only be briefly summarized here. According to our findings, the change in question was driven by a process of analogy, which led middle ver to assume the bleached meaning of hallarse ‘be’ after an extended period of competition between the two verbs.

More specifically, the historical data make manifest that, very early on, a semantic resemblance between ver and hallar ‘find’ has been perceived. To find is ‘to come upon’ either by accident or after a search (AHDEL, 1969, s.v. find), and one of the features the latter shares with the former is that the contact with the found object is typically visual.12 This explains the variation observed in constructions with a predicate adjective, both transitive (12) and middle (13):

| (12) | a. | Salyo Tisbe | e | vio | so | amygo | muerto |

| and | see.3sg.pfv | pos | friend.m.sg.acc | die.ptcp.m.sg | |||

| ‘Tisbe came out and saw her friend dead’ | |||||||

| (c 1200, Almerich, La fazienda de Ultra Mar, corde) | |||||||

| b. | llego a su tierra | & | fallo | ell | hermano | muerto | |

| and | find.3sg.pfv | the | brother.m.sg.acc | die.ptcp.m.sg | |||

| ‘he arrived in his land and found his brother dead’ | |||||||

| (c1280, Alfonso X, General Estoria. Cuarta parte, corde) | |||||||

| (13) | a. | como | se | vieron | cubiertos | de angustias | ||||

| because | refl.3pl | see.3pl.pfv | cover.ptcp.m.pl | of distress | ||||||

| ‘because they felt utterly distressed’ | ||||||||||

| (c1445–1480, Antón de Montoro, Cancionero, corde) | ||||||||||

| b. | El infançón | se | falló | mucho | arrepiso | |||||

| the nobleman.m.sg.nom | refl.3sg | find.3sg.pfv | much | repent.ptcp.m.sg | ||||||

| de lo que dicho avía | ||||||||||

| of that which said had | ||||||||||

| ‘The nobleman felt very sorry for what he had said’ | ||||||||||

| (1471–1476, Lope García de Salazar, Historia de las bienandanzas e fortunas, | ||||||||||

| corde) | ||||||||||

The “unmarked” choice, in terms of frequency, points to ver, but the competition on the part of hallar is facilitated by the fact that in these constructions the semantic contribution of the lexical verbs is slight. On occasion, the choice of hallar appears to be motivated by inherent components of its meaning (a notion of unexpectedness or an allusion to a previous inquiry), while ver is preferred in emotionally charged contexts.13 Yet, many times, the respective lexical nuances give the impression of having been neutralized. Through a process of analogical attraction (De Smet et al., 2018), hallar has become like ver in admitting experiencer subjects construed as more affected than canonical “finders”.

Nevertheless, in the transition period between Medieval and Classical Spanish (15th–16th centuries), middle hallar undergoes a notable change, which consists in the diffusion of its combinations with a locative complement, either spatial (fallose en la çibdat ‘he was in the city’: c1481–1482, Crónica de Enrique IV de Castilla 1454–1474, corde) or situational (se halló con él en muchas guerras ‘he was at his side in many wars’: p1504, Hernando de Baeza, Las cosas que pasaron entre los reyes de Granada, corde). This usage has the effect of impelling the new phrase hallarse presente ‘be present’ and the absolute formula se halló, meaning ‘he was there’.

Under our hypothesis, the habit of processing hallarse as signifying ‘be’ in all these locative/existential uses was extended to its middle construction with a predicate adjective, which was not only much less frequent but also conceptually close in expressing the subject’s presence ‘in’ some state (cf. se hallo solo ‘was alone’: 1600, Fray José Sigüenza, Segunda parte de la Historia de la Orden de San Jerónimo, corde vs. hallóse en soledad ‘was in [a state of] solitude’: 1528, Fray Antonio de Guevara, Libro áureo de Marco Aurelio, corde). What is possible to imagine, in turn, is that the new reading was expanded to middle ver, whose stronger experiential features had been dimmed as a result of its competition with hallarse in this type of construction, and which, moreover, had a long history of coupling with locative phrases as well.14

The evolutionary path we have traced helps to account for the 1780 dictionary entry reproduced above. Verse and hallarse, in constructions with a predicate participle or adjective, have been bleached to the point that they are felt to approximate Latin copular esse ‘be’, and, in consonance with this perception, the sequence of a reflexive voice marker and a lexical verb has been reanalyzed as a morphological unit (pronominal verse). In other words, a phenomenon of univerbation (Lehmann, 2020) has taken place, whose product, consisting of a primarily functional word, points to a process of grammaticalization rather than a (contentful) lexicalization (cf. Traugott & Trousdale, 2013, pp. 156–160).

Contemporary lexicographers continue to adhere to this view. Pronominal verse accompanied by a predicate adjective is defined in terms of hallarse,15 and pronominal hallarse signifies ‘to be’ in a certain state.16 Moreover, attesting to the role played by the locative/existential uses of hallar in the evolution of middle ver, pronominal verse is said to approximate hallarse ‘be’ in constructions where it appears with a locative complement.17

3.2.3. Problems of Analysis

Since Spanish possesses a number of verbs, both lexical (Sánchez López, 2002) and grammatical (Morimoto & Pavón Lucero, 2007), formed with a reflexive as an integral part of their morphological structure, the idea that verse might function as semicopular hallarse18 is not controversial. A major difficulty which those definitions do not reflect, however, is that the behavior of semicopular verse cannot be distinguished from that of middle ver. In principle (Lehmann, 2020), the process of univerbation which has taken place implies that the syntactic boundary existing between the voice clitic and the verb has been downgraded to a morphological boundary, but on the surface this is not perceptible, because Spanish clitics form a single phonological word with the preceding or following stressed verb. Neither are other structural adjustments in sight. A copular verb, by definition, needs to be accompanied by a predicating element, but in the construction in which verse originated the lexical middle verb was likewise characterized by the obligatory presence of a predicate participle or adjective carrying the main point of the utterance.

Our diachronic search yielded one piece of evidence for the bleaching process suffered by middle ver, associated with the 17th century, when in the data the phrase verse obligado ‘be obliged’, not registered in our earlier samples, emerges. The extension is significant, because obligado used to combine with either copular ser ‘be’ or copular estar ‘be’ (cf. Vañó Cerdá, 1982, pp. 272–273), so that the substitution of verse for the copulas clearly attests to the semantic erosion of middle ver.19

It is also possible to conjecture that the modal participle played a role in strengthening copular-like interpretations of verse in all occurrences of the constructional pattern with a human subject, considering that from the 17th century onward obligado predominates in terms of frequency.20

From this point of view, the innovative combination of verse with obligado may be treated as a symptom of semantic reanalysis (cf. Alba-Salas, 2020), but it does not necessarily embody a categorial change.

Beyond this one piece of evidence, it is far from clear that the situation at present corresponds to what lexicographers would have us believe. Some researchers state that verse with a predicate adjective always codes a state like hallarse (Suárez Fernández, 1997, p. 142), while others argue that it never does (Yllera, 1980, p. 271). Including verse obligado is alleged to conserve the lexical feature of middle ver ‘feel’ (NGLE, 2009, §35.5p). The discrepancies stem from a lack of structural cues for the distinction between middle ver and semicopular verse, and at the same time confirm the coexistence of distinct “layers” (Hopper, 1991). Depending on the specific contexts of use, and perhaps, too, on the individual speakers, the construction <Shum + refl + ver + adjectival predicate> is accessed in one way or the other.

Equally important to bear in mind is that, in this functional subdomain, ver alternates with the Spanish copulas ser and estar. Assuming that an area of variation implies more or less conscious choices, it may well be the case that grammaticalized verse continues to be associated with a feature of ‘affectedness’ retained from the experiential dimension of the middle voice construction. The motivation for choosing, for example, me veo obligado ‘I am (and feel) obliged’, instead of estoy obligado ‘I am obliged’, would gain sense from this perspective.

3.3. The Reflexive Passive Construction and Grammaticalized Verse ‘Look’

3.3.1. Emergence of the Reflexive Passive Construction

Our diachronic study made it possible to identify other changes that affected the construction of ver with a predicate participle or adjective, changes that occurred in a stepwise succession through time. In our corpus, signs of the first change emerge when, in the 17th century, next to the middle-reflexive construction with a human subject, various examples appear in which the subject is an inanimate entity, not capable of engaging in an act of self-perception. The condition allocated to the entity has been noticed by an experiencer, who remains implicit but may sometimes be recovered from the context. This is the case in (14), excerpted from a passage which narrates a mutiny on a ship and describes the death of the wounded captain, breathing his last breath with two cherished medallions in his grip. The crewmen who found him are the ones who saw the objects “bathed in blood”:

| (14) | entre estos dos refugios, abonos de su piedad, | que | después | se | ||

| which | later | refl | ||||

| vieron | bañados | en sangre, | dió su alma al Señor | |||

| see.3pl.pfv | bathe.ptcp.m.pl | in blood | ||||

| ‘between these two refuges, pledges of his piety, which afterward were | ||||||

| seen bathed in blood, he gave his soul to the Lord’ | ||||||

| (1676, fray Francisco de Santa Inés, Crónica de la provincia de San Gregorio | ||||||

| Magno en las Islas Filipinas, corde) | ||||||

The syntactic pattern illustrated in (14) corresponds to what is known as the “reflexive passive” (pasiva refleja) in Spanish grammars. As expected from a passive, the visual event to which the clause refers is staged from the perspective of the perceived entity. In contrast to the analytic passive (ser ‘be’ + participle), with which it competes in certain contexts, the reflexive structure has two distinguishing properties: it is limited to third-person subjects and is highly resistant to the expression of the demoted agent (Sánchez López, 2002; Zúñiga, 2023). Furthermore, in this case, the reflexive clitic is generally considered to have lost its pronominal features, though its precise categorial status is debated. We will treat it as a passive voice marker (Haspelmath, 1990).

The delayed presence of the reflexive passive in our corpus relates to the fact that this construction, though present since the recorded beginnings of Spanish, took time in establishing itself as a regular alternative to the analytic passive. Scholars have tended to associate the diffusion of the reflexive passive with the period of transition between Medieval and Classical Spanish (15th–16th cent.) (Cornillie & Mazzola, 2021; Enrique-Arias & Bouzouita, 2013; Melis & Peña-Alfaro, 2007).

What is clear, with respect to ver, is that the verb’s entrenched transitive and middle uses served as analogical models for the extension of the co-predicate pattern (participle or adjective) to the passive. The following pairs of examples will help to illustrate this. In (15a) and (16a), we have simple passives, focusing on the identity of the object of visual experience (peligros ‘dangers’; cometa ‘comet’); in (15b) and (16b), a predicate adjective is added, and the perspective shifts to the condition of the object as perceived by implicit experiencers:

| (15) | a. | con el ençendimiento | del amor | no | se | ven | ||||||||

| with the kindling | of love | not | refl | see.3pl.prs | ||||||||||

| los | peligros | |||||||||||||

| the | danger.m.pl.nom | |||||||||||||

| ’with the kindling of love, one does not see dangers’ | ||||||||||||||

| (lit. ‘dangers are not seen’) | ||||||||||||||

| (1514, Pedro Manuel de Urrea, La penitencia de amor, corde) | ||||||||||||||

| b. | se | veen | tan | claros | los | peligros | ||||||||

| refl | see.3pl.prs | so | clear.m.pl | the | danger.m.pl.nom | |||||||||

| de la christiandad | ||||||||||||||

| of the Christian.world | ||||||||||||||

| ’because the dangers facing Christians are seen as being so clear’ | ||||||||||||||

| (1524, Juan de Molina, Traducción de la Crónica de Aragón de Lucio | ||||||||||||||

| Marineo Siculo, corde) | ||||||||||||||

| (16) | a. | en otro tiempo | se | vio | otro | cometa | ||||||||

| in other time | refl | see.3sg.pfv | other | comet.m.sg.nom | ||||||||||

| en el yvierno | ||||||||||||||

| in the Winter | ||||||||||||||

| ‘on a different occasion, another comet was seen in the winter’ | ||||||||||||||

| (1578, José Micón, Diario y juicio del grande cometa, corde) | ||||||||||||||

| b. | aquel que […] apareció | y | se | vio | mayor | o | tan | |||||||

| that which appeared | and | refl | see.3sg.pfv | bigger | or | as | ||||||||

| grande | como el Sol | |||||||||||||

| big | as the sun | |||||||||||||

| ‘that [comet] which appeared and was seen to be bigger or as big as the sun’ | ||||||||||||||

| (1578, José Micón, Diario y juicio del grande cometa, corde) | ||||||||||||||

The transitive construction, which, as seen above, admitted both animate and inanimate direct objects, cleared the way for the occurrence of an inanimate passive subject, while the middle construction facilitated the production of another reflexive pattern with a predicating participle or adjective.21

As a consequence of the diffusion of this passive pattern, a new layer is added to the grammatical domain under study. Starting from the 17th century, our corpus data comprise transitive clauses, (partially) grammaticalized middle constructions, and reflexive passive structures (more on these below), which co-occur, extending over roughly equivalent portions of the sets of uses.22

Worthy of note is that the passive constructions documented in our corpus rarely feature an animate subject. This is in line with what has been observed about the general behavior of the reflexive passive in Spanish (Sánchez López, 2002, p. 54). On a first reading, the occasional examples with a human subject which do crop up are likely to be confused with instances of the middle. The distinction requires a careful inspection of the respective contexts, as in (17), where the description of the “bitten” Indians is more compatible with the sense that their condition is something seen by others rather than apprehended in an act of self-perception.

| (17) | aunque | se | ven | mordidos | muchos | indios | |||||

| although | refl | see.3pl.prs | bite.ptcp.m.pl | many | indian.m.pl.nom | ||||||

| en este sitio | de semejantes bestias, jamás peligran | ||||||||||

| in this place | by such beasts | ||||||||||

| ‘although many Indians are seen bitten by such beasts [snakes] in this location, they are never in danger’ | |||||||||||

| (1690, Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán, Historia de Guatemala o recordación | |||||||||||

| florida, corde) | |||||||||||

The reflexive passive thus critically differs from the one-participant middle construction in communicating an event involving two participants. The experiencer has been silenced for discursive purposes but is entailed.

3.3.2. Univerbation and Grammaticalization: Verse ‘To Look’

Our discussion of the passive up to this point has insisted on the presence of an implied experiencer. Quite transparent, on the other hand, is the potential of the reflexive passive to be used with the focus exclusively centered on the subject entity and its state, at the cost of the experiencer, who ceases to form part of the conceptualized scene. When this happens, the notion of a visual event fades, giving way to the representation of an entity which displays a certain property.

In Morimoto and Pavón Lucero’s (2007) synchronic study, some clauses built with ver and a predicate adjective are claimed to encode such representation. The authors comment that in cases like (18) the pronominal unit verse functions as a semicopular verb (Morimoto & Pavón Lucero, 2007, p. 63).

| (18) | a. | La ciudad | se | veía | desierta. | |

| the city.f.sg.nom | refl | see.3sg.ipfv | deserted.f.sg | |||

| ‘The city looked deserted.’ | ||||||

| b. | La niña | siempre | se | ve | soñolienta. | |

| the girl.f.sg.nom | always | refl | see.3sg.prs | sleepy.f.sg | ||

| ‘The girl always looks sleepy.’ | ||||||

To corroborate the process of semantic erosion suffered by ver, Morimoto and Pavón Lucero (2007, p. 63) show that it is the adjective converted in main predicate that selects the subject.

| (18’) | a. | {#La niña/La ciudad} se veía desierta. |

| b. | {La niña/#La ciudad} siempre se ve soñolienta. |

Unfortunately, the test proposed for the grammatical analysis of these clauses has little weight, considering that a parallel phenomenon of semantic compatibility occurs in the transitive clause, where ver retains its lexical value (cf. Veo {la ciudad/#la niña} desierta ‘I see {the city/#the girl} deserted’).

In their study, verse together with items like mostrarse ‘show itself’ and presentarse ‘present itself’ conform a subclass of non-aspectual semicopular verbs tied to a notion of “appearance”, defined by Nava Ruiz (1963) as “the way in which the attributed quality shows itself to the speaker’s eyes” (Morimoto & Pavón Lucero, 2007, p. 64). The authors also mention that, with verse, the relation established between the subject and the attribute typically emanates from a visual experience, so that the semicopular verb is held to contribute a feature of “evidentiality” to the semantics of the construction (Morimoto & Pavón Lucero, 2007, p. 64).

It is true that in data of use semicopular verse issued from the passive tends to combine with participles or adjectives that denote perceptible characteristics. The contemporary samples in our corpus confirmed this tendency. But when widening the search, one finds examples involving subjective evaluations applied to abstract entities.

| (19) | a. | Cierto es que | la línea | de argumentación | se | ve | ||||

| true is that | the line.f.sg.nom | of argumentation | refl | see.3sg.prs | ||||||

| algo | mecánica, | tosca | ||||||||

| something | mechanical.f.sg | rough.f.sg | ||||||||

| ‘It is true that the line of argument looks somewhat mechanical, rough’ | ||||||||||

| (2003, Mayol Miranda, “La Tecnocracia: el falso profeta de la Modernidad”, | ||||||||||

| corpes) | ||||||||||

| b. | La salida | al conflicto | se | ve | difícil | |||||

| the way.out.f.sg.nom | to.the conflict | refl | see.3sg.prs | difficult.f.sg | ||||||

| ‘The way out of the conflict looks difficult’. | ||||||||||

| (2004, El Mercurio, 2 June 2004, CORPES) | ||||||||||

In such cases, verse comes close to behaving like Spanish parecer ‘appear, look, seem’ (Fernández Leborans, 1999, §37.7; NGLE, 2009, §37.10d-e). The competition established between the two semicopular verbs is particularly strong in American Spanish (NGLE, 2009, §37.10e), but the latter continues to be preferred in contexts of strictly personal opinions or low commitments to the truth of the message. Indeed, parecer has been classified as an epistemic modal (Cornillie, 2007; Morimoto & Pavón Lucero, 2007).

Of typological interest is the fact that the historical trajectory of Spanish ver resembles that of the English transitive verb look in showing a phenomenon of “intersection” with intransitive seem type verbs, as discussed in Dixon (1991). Among these verbs are included appear, look and seem, which function as copulas (Dixon, 1991, p. 200) when they occur with an adjective. The author comments that, though similar in meaning, appear and look may imply visual observation of the attributed property, in contrast to seem, specialized in conveying inferences and more dubitative appraisals (Dixon, 1991, p. 202). Another characteristic of the seem type verbs is that they always involve the presence of an “arbiter”, typically understood as being the speaker (Dixon, 1991, p. 200).

In retrospect, it is possible to outline the evolutionary path along which passive ver turned into semicopular verse ‘look’. The functional shift was facilitated by the resistance of the reflexive passive to carry an explicit mention of the (demoted) experiencer. This made it easy to overlook or erase the presence of this participant in the visual event and, once removed from the scene, the passive subject—typically inanimate but sometimes animate—could then be reinterpreted as ‘offering to view’ a certain property. In this way, the right conditions were set for the vacant slot, open to a potential viewer, to be occupied by the speaker in the role of the implicit “arbiter”, to borrow Dixon’s terminology. The path leading from the experiencer of passive ver to the arbiter of verse ‘look’ may therefore be characterized as having involved a process of “subjectification” (e.g., Traugott, 1989). At the morphosyntactic level, the new reading promoted the coalescence of the passive voice marker and the verb into a morphological compound, accessed as a unit and introduced into the Spanish paradigm of semicopular verbs (univerbated verse). Over time, the connection to a visible property passed on from the source construction was loosened, allowing for the copular clause to extend to judgments of mere likelihood. In these extensions, the original meaning ‘offer to view’ slid into something more akin to ‘give the impression of’.

3.3.3. Expanding on the Evolutionary Path of the Reflexive Passive

What is important to highlight is that our qualitative analysis of the corpus data did not furnish solid evidence of an entrenched copular use until the 20th century. In the texts belonging to earlier periods (17th- and 19th-century samples), a passive reading remains available on a regular basis. This is especially true in contexts where the perfective form of the verb profiles the completion of a punctual event of perception, whose experiencer is susceptible of being recovered, as we saw in (14) above, or alludes to an indefinite group of individuals, as in this example from the 19th century:

| (20) | Dicha situación fué agravándose por días; […] y las fortunas | ||||

| and the fortune.f.pl.nom | |||||

| particulares | se | vieron | disminuidas | en un tercio de su valor | |

| private.f.pl | refl | see.3pl.pfv | reduce.ptcp.f.pl | in a third of their value | |

| en tan corto período de tiempo. | |||||

| in such short period of time | |||||

| ‘This situation grew worse as the days went by; […] and private fortunes | |||||

| were seen reduced to a third of their value in such a short period’ | |||||

| (1879, Francisco Carrasco y Guisasola, Excursión por las Repúblicas de Plata, corde) | |||||

More suited to suggest the semicopular use of verse ‘look’ are clauses with an imperfective aspectual contour. The 17th-century data of our corpus contain various instances pointing in that direction, the majority of which comes from the historical work of Fuentes y Guzmán.

| (21) | a. | es un valle | cuya | formación | y | asiento | |||||

| is a valley | whose | formation.f.sg.nom | and | setting.m.sg.nom | |||||||

| á la parte del Norte | se | ve | ceñido | ||||||||

| at the side of.the North | refl | see.3sg.prs | gird.ptcp.m.sg | ||||||||

| de inaccesibles serranías | |||||||||||

| by inaccessible mountains’ | |||||||||||

| ‘it is a valley whose formation and setting on the northern side is seen | |||||||||||

| (looks) girded by inaccessible mountains’ | |||||||||||

| (1690, Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán, Historia de Guatemala o | |||||||||||

| recordación florida, corde) | |||||||||||

| b. | y jamás | se | ve | el árbol | exhausto | ||||||

| and never | refl | see.3sg.prs | the tree.m.sg.nom | exhausted.m.sg | |||||||

| de flores | |||||||||||

| of flowers | |||||||||||

| ‘and the tree is never seen (never looks) exhausted of flowers’ | |||||||||||

| (1690, Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán, Historia de Guatemala o | |||||||||||

| recordación florida, corde) | |||||||||||

Typically, these clauses appear in passages where the author is engaged in the description of a site, a rite, or an object of colonial Guatemala for the benefit of the Spanish Crown. On first sight, a reading in terms of grammaticalized verse ‘look’ is available; actually, however, it turns out that Fuentes y Guzman reports personal observations of his native land. In other words, the speaker, who assumes the role of the implicit arbiter in the apparent copular clause, is simultaneously involved as the silenced experiencer who noted the condition of the passive subject. Under our proposal, clauses in which the roles of experiencer and arbiter converged in the person of the speaker acted as “bridging contexts” (Evans & Wilkins, 1998; Heine, 2002) in the evolution from passive ver to copular verse ‘look’.

As we indicated above, contemporary data do exhibit unequivocal outputs of this evolution. (22) is an example:

| (22) | Todo | se | ve | limpio, |

| everything.m.sg.nom | refl | see.3sg.prs | clean.m.sg | |

| huele a limpio y está insoportablemente ordenado. | ||||

| ‘Everything looks clean, smells clean, and is unbearably orderly.’ | ||||

| (2005, Jaime Bayly, Y de repente, un ángel, corpes) | ||||

Yet, in the absence of reliable formal clues, the task of separating copular clauses from passive ones is delicate. Beyond the exceptional cases in which an adverbial phrase modifies the event of perception (cf. [el cielo] que como todos los días se veía traslúcido ‘[the sky] that, like every day, looked translucent’: 2005, Maribel Barreto, Código Arapónga, corpes), the specific contexts of use need be examined in detail to determine whether or not an implied experiencer can be retrieved. This matters to the analyst, who, on the basis of the distinction, will identify the lexical nucleus of a reflexive passive or, alternatively, a pronominal semicopular unit. Language users, on the other hand, are not faced with this problem. They have a verbal element at their disposal, bleached to a certain extent but still connected to a vague notion of visual experience, which they freely employ when intending to allocate a property to an entity. For their communicative purposes, the relevance of discerning between experiencers and arbiters is very low indeed.

3.3.4. Extension of Verse ‘Look’ to the Second Person

Another signal that language users do not fully analyze the underlying grammatical structure of the sentences they produce and process (Pijpops & Van de Velde, 2016, and references therein) emerges from the extension of semicopular verse ‘look’ to second-person subjects.

| (23) | a. | Te | ves | muy linda. | Paliducha | pero | preciosa | ||

| refl.2sg | see.2sg.prs | very pretty.f.sg | paleish.f.sg | but | lovely.f.sg | ||||

| ‘You look very pretty. Paleish but lovely.’ | |||||||||

| (1975, Emilio Carballido, Las cartas de Mozart, crea) | |||||||||

| b. | ¡Tantos años! El tiempo no ha pasado por ti… | ||||||||

| Te | ves | entera, | como en nuestra época de oro. | ||||||

| refl.2sg | see.2sg.prs | whole.f.sg | as in our epoch of gold | ||||||

| ‘So many years! Time hasn’t passed for you…You look whole, | |||||||||

| like in our golden epoch.’ | |||||||||

| (2005, Eliseo Alberto, Esther en alguna parte o El romance de Lino y | |||||||||

| Larry Po, corpes) | |||||||||

This usage starts to gain visibility in data from the second half of the 20th century. The early instances of the construction show a limited range of adjectives (physical properties like cansado ‘tired’, joven ‘young’ or flaco ‘thin’, and, predominantly, evaluatives like hermoso ‘beautiful’, lindo ‘pretty’ or guapo ‘handsome’). In recent years, a striking diversification of lexical items and semantic types has taken place.23 Verifying the novelty of the second-person construction is the fact that it has barely been introduced in the 2014 edition of the Diccionario de la Lengua Española, with a note regarding its vitality in America.24 Indeed, the contemporary registers confirm the dialectal dimension of the change; peninsular Spanish employs the construction sparingly.

The anomalous character of the construction, from a syntactic point of view, resides in the discrepancy between form and meaning. The semantics of the clauses in (23) point to grammaticalized verse ‘look’ evolved out of the reflexive passive. However, the new structure cannot be linked directly to the passive, restricted, as we said, to third-person subjects. To account for its genesis, we have to suppose that language users created an extension modeled on the full paradigm of grammaticalized verse ‘be’ arisen from the middle-reflexive construction.25

The two semicopular verbs perform distinct functions which tie in with their distinct origins. One forms one-participant clauses with a human subject described simply as ‘being’ in a certain state; the other implies that the attribute predicated of the subject by the adjective or participle is apprehended from an external point of view. Nonetheless, on the surface, the constructions are identical, and they similarly serve to give prominence to a state of being or a quality of someone.

The ultimate change discussed in this paper finds a natural explanation in these resemblances. Second-person subjects are added to the domain of semicopular verse ‘look’, with the burden of elucidating meanings left up to the contexts of use.

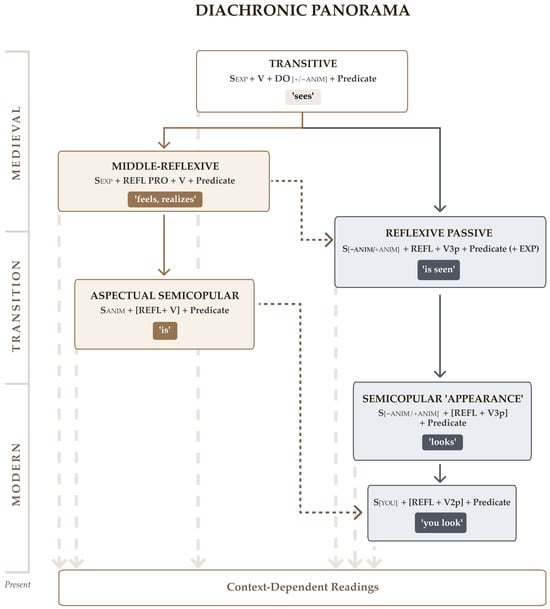

In Figure 1, we offer a synoptic view of the pathways we are proposing for the diachronic development of the constructions of ver with a predicate participle or adjective, in which we highlight the existence of two trajectories derived from the transitive clausal pattern: the middle-reflexive, on one hand, and the reflexive passive, on the other. Additionally, we show that the internal relations holding between the different constructional “layers” have come to form an intricate network of syntactic structures and semantic functions, dependent on the contexts of use for their disambiguation.

Figure 1.

The evolution of ver ‘see’ with a predicate participle or adjective.

3.4. A Renewal of Latin Videri?

Before we conclude our diachronic study, we wish to draw attention to a phenomenon of great interest, which has to do with the fact that the evolution of passive ver in Spanish generated a semicopular verb reminiscent of Latin videri.

As is known, in the mother language, active videre ‘see’ possessed an alternative “medio-passive” (Baños Baños, 2009, p. 386; Ernout & Thomas, 1972, §223) or “deponent” (Claflin, 1942; Stefanini, 1962, p. 177) form, treated as a separate entry in some dictionaries (e.g., Gaffiot, 1934). Syntactically, videri required some kind of complementation (Reinhardt, 2015), which could consist of an adjective that showed agreement with the subject (Pinkster, 2015, p. 208), hence the “copular” function attributed to videri in some grammars (Ernout & Thomas, 1972, §172; Pinkster, 2015, p. 208).

Semantically, the notions expressed by videri revolved around an idea of “appearance” (Claflin, 1942; Joffre, 1995, p. 138; Reinhardt, 2015). Depending on the context, its meanings—‘appear’, ‘look’, ‘seem’—ranged from that which is manifest to impressions of more doubtful nature (Reinhardt, 2015). The examples in (24) illustrate the behavior of copular videri, comparable to that of Spanish verse ‘look’.

| (24) | a. | hau | sordidae | uidentur | ambae | |

| not | dirty.nom.f.pl | see.3pl.prs.pass | both.nom.f.pl | |||

| ‘the two of them don’t seem dirty at all’ (Plaut. Bacc. 1124) | ||||||

| b. | Aliis | illud | indignum, | |||

| some.dat.pl | dem.nom.n.sg | shameful.nom.n.sg | ||||

| aliis | ridiculum | uidebatur | ||||

| other.dat.pl | ridiculous.nom.n.sg | see.3sg.ipfv.pass | ||||

| ‘Some found it distressing, others absurd’ (Cic. Verr. 1,1,19) | ||||||

| (lit. ‘To some it appeared…’) | ||||||

| c. | Peregrina | facies | uidetur | hominis. | ||

| foreign.nom.f.sg | figure.nom.f.sg | see.3sg.prs.pass | man.gen | |||

| atque | ignobilis | |||||

| and | unknown.nom.f.sg | |||||

| ‘The man’s face seems foreign and unknown’ (Plaut. Pseud. 964) | ||||||

Unlike Spanish verse, however, videri did not proceed from the passive use of active videre; the sense ‘be seen’ developed later (Claflin, 1942; Reinhardt, 2015; Stefanini, 1962, p. 177). Rather, the hypothesis is that the verb made its way into the Latin language as an inherited middle form, with homologues in ancient Greek and Sanskrit (Claflin, 1942).

Cross-linguistically, a middle marking on stimulus-based perception verbs, in constructions that designate relatively static processes, is not common (Kemmer, 1993, pp. 136, 145). However, if we take into account that Latin videri and its correspondents in other ancient languages are traceable to the Indo-European root *weid-, whose meaning involved ideas of visual perception and knowledge (Claflin, 1942, and references therein), the rise of middle videri ‘appear, look, seem’ suggests a shift in perspective resembling that which passive ver underwent in Spanish: the experiencer disappears from the scene and the original object of perception is construed as ‘offering to view’ a certain property.

On a first approach, the functional overlap displayed by videri and verse invites to speak of a “renewal” in the continuing history of the verb of perception, and to relate the observed phenomenon to the notion of the “cyclical” nature of linguistic change (Bouzouita et al., 2019; Mosegaard Hansen & Waltereit, 2025). From this vantage point, one would argue that the vanishment of deponent videri, in the transition period from Latin to Spanish, fostered the development of verse ‘look’, as a way of reviving the expression of meanings which the Romance heir of videre had lost.

However, in a recent work, Reinöhl and Himmelmann (2017) have put forward a series of claims about the inadequacy of such a teleological approach to language change. The authors propose, instead, that constructions deriving from similar sources can be expected to travel similar paths of grammaticalization and to end up covering almost identical functions. Considering the semantic relation holding between Latin videre and Spanish ver, it seems that the “principle of source determination” defended by Reinöhl & Himmelman provides a valuable alternative explanation for the change in question.

4. Conclusions

Lexical items, as reiterated in many studies, undergo processes of change not in isolation but within specific constructions. The evolution of Spanish ver ‘to see’ outlined in this paper adds another piece of evidence in support of this fact.

The prime source construction is one in which the transitive verb of visual or mental perception co-occurs with a predicate participle or adjective agreeing with the direct object, and in which the object’s presence in a certain state carries the main point of the utterance. As discussed in Boye and Harder (2007, 2012), when two predicating elements are parts of a complex linguistic message, they compete for attention and may propitiate a gain in prominence of the structurally dependent element, at the expense of the main verb. The backgrounded verb, associated with what the authors term “secondary discourse prominence”, continues to function as a lexical item but may lose some semantic contours by virtue of its low saliency. And when this ambiguous status repeats itself with sufficient frequency, the lexical verb is susceptible to undergoing grammaticalization, provided its semantics enable the development of a plainly ancillary function in relation to the predicate it accompanies. This happened to Spanish ver (<Latin videre), which had a long history of playing “second violin” (Boye & Harder, 2012, p. 7) in the transitive construction with an adjectival predicate inherited from its ancestor.

With the transitive construction as backdrop, Spanish ver is led to grammaticalize on two occasions—evidencing a case of polygrammaticalization (Elvira, 2015, §5.5; Heine, 2003, p. 590)—in close connection to voice operations. The middle-reflexive clause, of early date, which profiles an event of self-perception, triggers a process of change whereby the lexical verb loses its experiential meaning (‘feel’, ‘realize’) and transforms into a semicopular item serving to express the human subject’s ‘being’ in a certain state. On the other hand, the reflexive passive, whose noticeable diffusion in the language has been traced back to the transition period between Medieval and Classical Spanish, drives the lexical verb to adopt a semicopular function in clauses where the subject is construed as ‘giving the appearance or impression’ of some quality.

In both cases, the grammaticalization gives rise to a pronominal unit (semicopular verse), obtained from the condensation or “univerbation” (Lehmann, 2020) of a string of two elements—the voice clitic and the lexical verb—into a single word. In Spanish, clitics are prone to intervene in processes of morphologization (Sánchez López, 2002). Here, worthy of note is the way in which the distinct voice clitics, middle and passive, shaped the grammaticalized outputs: verse ‘be’ conserves from its middle source the one-participant character of the clauses it occurs in, while verse ‘look’ entails the presence of an external eye (the arbiter’s view), in consonance with the two-participant event passive clauses implicitly refer to.

With respect to the mechanisms of change, recent studies have emphasized the role analogy plays in extensions of meanings and syntactic patterns, based on perceived affinities with other coexisting words or constructions (e.g., Fischer, 2013). We identified such process in our comparative study of ver and hallar ‘find’, which had the effect of promoting the conversion of middle ver into semicopular verse ‘be’ under the influence of the locative/existential meaning developed by hallar.

Contrary to the incidence of “horizontal” links (Traugott, 2018) characteristic of analogy, a typical “vertical” pathway of grammaticalization was observed in the second case. It consisted of a shift in perspective, facilitated by verbs of perception in general (cf. Latin videre and English look), which eliminated the experiencer of the passive from the scene and produced a construction with its focus placed on how an entity ‘appears’ (to a potential viewer). Under our proposal, semicopular verse ‘look’ arose through the operation of “bridging contexts” (Evans & Wilkins, 1998; Heine, 2002) in which the speaker could be interpreted both as the experiencer of a visual event and the arbiter of a seem type clause (Dixon, 1991).

Ideally, of course, the recategorization of a lexical verb as a grammatical copula should exhibit changes in the morphosyntactic behavior of the item concerned, once the phase of “actualization” following the reanalysis has occurred (Amaral & Delicado Cantero, 2022, pp. 18–19). Unfortunately, the functional areas examined in this work, as we made clear during our exposition, provided little evidence in this regard. The constructions are superficially identical, and the structural distinctions to be spotted depend most of the time on subtle contextual clues. What prevails in contemporary Spanish is a situation of multiple “layering” (Hopper, 1991), extremely complex and, admittedly, rather hazy.

On the whole, the attested tokens of the pattern <S + refl + ver + adjectival predicate> strongly suggest that language users employ a construction stored as a chunk, that is, as an unanalyzed, or not fully parsed (Pijpops & Van de Velde, 2016), expression, which basically serves to link the subject to a state of being or a quality, independently of whether or not the denoted property was actually perceived (by the subject’s self or by someone else).

Stored as such, the constructional pattern represents a “marked” alternative for the encoding of a message that is regularly conveyed with the help of the copular verbs ser ‘be’ or estar ‘be’. The fact that in certain contexts speakers choose verse over the canonical copulas indicates that the grammaticalized outputs of Spanish ver are not completely devoid of meaning. They contain vestiges of their respective lexical sources which can be taken advantage of for discursive purposes. In this way, middle-derived verse ‘be’, as compared to simple estar, helps to confer a feature of affectedness to the human subject whose state of being is profiled, while passive-derived verse ‘look’, unlike the regular copulas, underscores the outward display of the attributed quality. The problem of teasing apart individual components of internal structures is not something language users battle with; this issue solely troubles syntacticians.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.; methodology, C.M., M.I.J.M. and M.A.V.; formal analysis, C.M., M.I.J.M. and M.A.V.; investigation, C.M., M.I.J.M. and M.A.V.; writing-original draft preparation, C.M.; writing-review and editing, C.M., M.I.J.M. and M.A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository. The original data presented in the study are openly available in [Real Academia Española, Corpus Diacrónico del Español] at [https://rae.es/banco-de-datos/corde], [Real Academia Española, Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual] at [https://rae.es/banco-de-datos/crea], and [Real Academia Española, Corpus del Español del Siglo XXI] at [https://rae.es/banco-de-datos/ corpes-xxi] accessed between 1 September 2024 and 1 September 2025.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers and to the editors of this volume for their critical and helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in the glosses of the Spanish examples:

| abl | ablative |

| acc | accusative |

| comp | comparative |

| dat | dative |

| dem | demonstrative |

| dom | differential object marking |

| f | feminine |

| gen | genitive |

| inf | infinitive |

| ipfv | imperfective |

| m | masculine |

| n | neuter |

| nom | nominative |

| pass | passive |

| pfv | perfective |

| pl | plural |

| poss | possessive |

| prs | present |

| ptcp | participle |

| refl | reflexive |

| sg | singular |

Notes

| 1 | We eliminated all instances where the predicate adjective or participle functioned as a modifier (Pero yo solo veo esta cara horrenda ‘But I only see this horrible face’: 1975, Luis Gasulla, Culminación de Montoya), or as a clear secondary predicate in satellite position (Sí…allí veo a mi don Juan, coronado de gloria y de laureles ‘Yes…over there I see my don Juan, crowned with glory and laurels: 1879, Alfredo Chavero, Los amores de Alarcón). See (Rodríguez Espiñeira, 2006). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | The additional texts from the 13th century are Almerich, La fazienda de Ultra Mar (c1200), Vidal Mayor (c1250), Fuero Juzgo (c1250–1260), El Evangelio de San Mateo (a1260), El Nuevo Testamento según el manuscrito escurialense I-j-6 (a1260), Los libros de los Macabeos (a1260), Alfonso X, Estoria de Espanna que fizo el muy noble rey don Alfonsso (c1270), and Alfonso X, General Estoria. Primera parte (1275). From the 15th century: Hernando del Pulgar, Letras (c1470–1485), Esopete ystoriado (a1482), Crónica de Enrique IV de Castilla 1454–1474 (1481–1482), Diego de San Pedro, Cárcel de amor (1482–1492), La corónica de Adramón (c1492), Antonio de Nebrija, Gramática castellana. BNM I2142 (1492), Diego Enríquez del Castillo, Crónica de Enrique IV (c1481–1502), and Fernando de Rojas, La Celestina (c1499–1502). From the 17th century: Alonso de Castillo Solórzano, La niña de los embustes, Teresa de Manzanares (1632), Antonio Panes, Escala Mística y Estímulo de Amor Divino (1675), Manuel Rodríguez, El Marañón y Amazonas (1684), Gabriel Fernández de Villalobos, Desagravios de los indios y reglas precisamente necesarias para jueces y ministros (1685), Francisco Bances Candamo, Por su rey y por su dama (c1687), Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán, Historia de Guatemala o recordación florida (1690), and Baltasar de Tobar, Compendio bulario índico (1695). Regarding the 19th century, an automatic filter was applied to reduce the number of occurrences of the mentioned verbal forms linked to the years 1876–1880. The sample was enriched with materials drawn from Diego Barros Arana, Historia general de Chile, III (1884), Clarín (Leopoldo Alas), La Regenta (1884–1885), José María de Pereda, Sotileza (1885–1888), and Luis Coloma, Pequeñeces (1891). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | For instance, in Spanish considerar means ‘examine, study’, but in combination with a predicating complement its meaning shifts to ‘hold an opinion’ about someone or something (Demonte & Masullo, 1999, p. 2498; Rodríguez Espiñeira, 2006, p. 119). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | The syntactic analysis of the object complement varies. Some scholars envisage a structure with three semantic arguments (S + DO + Predicate) (Rodríguez Espiñeira, 2006); others appeal to the existence of a “small clause’ (Demonte & Masullo, 1999, pp. 2501–2503). Space limitations prevent us from elaborating on this issue. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | For all the Latin examples cited in the text, we reproduce the Loeb translation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | The global picture of relative stability finds support in distributional data. With animate (typically human) direct objects, the predicates designating physical, mental, social, or locative states, as defined above, and well represented since the beginnings, conform the majority of instances across time. For example: 75% (81/108) in the 13th cent.; 87% (73/84) in the 17th cent.; 87% (98/113) in the 20th–21st cent. The other two categories, namely individual-level predicates and those expressing a subjective evaluation, which distance the transitive clause from a notion of perception, remain marginal. Note that the higher frequency of these two categories in the 13th century is due to a reiterated use (16 tokens) of the adjective hermoso ‘beautiful’. The inanimate direct objects, on the other hand, were organized in two broad semantic classes, labeled “concrete” and “abstract”, according to their capacity of being perceived with the senses (body-parts, physical things, places, elements of nature, products of speech) or less directly so (eventive nouns, concepts). In this case, the data reflect an increase in “abstract” referents: 9% (6/66) in the 13th cent.; 41% (17/41) in the 17th cent.; 57.5% (23/40) in the 20th–21sth cent. As for the predicate participles or adjectives, of very diverse nature, the data from modern Spanish (19th to 21st cent.) contain a more visible presence of modal adjectives (claro ‘clear’, probable ‘probable’, necesario ‘necessary’, fácil ‘easy’), in comparison to the single occurrence of verdadero ‘true’ from the 13th century, but these amount to just a handful of tokens within the universe of the transitive construction. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | For the clitic status of the unstressed pronouns of Spanish, see (Fernández Soriano, 1999, §19.5.3). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | In Late Latin, the coding of the predicative adjective in the nominate case grew more frequent, as part of the general evolution from the reflexive uses of the mother language to the middle forms of the Romance daughters (Stefanini, 1962, pp. 208–215; cf. Joffre, 1995, pp. 275–276). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Individual-level and evaluative predicates are, as in the transitive clauses, very rare, but gain a bit more visibility in modern Spanish with items like inútil ‘good-for-nothing’, capaz ‘competent’, espléndido ‘splendid’ or ridículo ‘ridiculous’. Of interest is that the semantic profile of the predicates involved in the middle construction will undergo a change at a later point in the history of the language (cf. infra, §3.2.3). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | This general assessment rests on the following distributional data: transitive (#174) vs. middle (#41 = 19%) in the 13th century; transitive (#139) vs. middle (#78 = 36%) in the 15th century. Owing to the rise of another constructional pattern, which will be the topic of Section 3.3, our postmedieval samples show a different configuration (cf. infra, note 21). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Available online: https://webfrl.rae.es/ntllet/SrvltGUILoginNtlletPub, accessed on 30 January 2025. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | This is made explicit in dictionary definitions of ‘find’ verbs in Spanish (cf. Ver por fin una cosa que se busca o averiguar dónde está ‘To finally see something one is looking for or to determine where it is’: Moliner, 1998, s.v. encontrar). And it underlies Dixon’s (1991, p. 125) subsumption of English find in the broader class of ‘attention’ verbs, to which see belongs. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | To exemplify, the use of hallar in (i) contrasts with the choice of experiential ver in (ii). In the former passage, Cyrus finds out about one of Isaiah’s ancient prophecies, in which God expressed the desire for the Persian king to lead the Jewish people back to Jerusalen so they could rebuild the divine temple. The second passage has Alexander the Great preparing his expedition against Darius, when he is shown one of Daniel’s prophecies foreshadowing the destruction of the Persian empire by a “Greek king”. The reaction is surprise in (i), as opposed to intense rejoicing in (ii).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Our reconstruction is the product of a comparative analysis of se vio and se halló (third-person singular, indicative, perfect past), in clauses showing a human subject, from the 13th to the 16th century. We retrieved, classified, and computed the different types of complements they appeared with. Of interest here are the predicate participles/adjectives, on the one hand, and the locative phrases, spatial or situational, on the other. Initially (13th and 14th cent.), se vio is found to attract locative phrases slightly more often (15/88 = 17%; 13/85 = 15%) than se halló (3/61 = 5%; 3/30 = 10%), but this situation changes in the following centuries (15th and 16th cent.): se vio + locative (61/205 = 30%; 74/281 = 26%) vs. se halló + locative (85/176 = 48%; 183/277 = 66%). Hence, our hypothesis is that the predominant locative/existential meaning developed by hallar in the transitional period between Medieval and Classical Spanish (15th–16th cent.) affected the reading of its uses with a participle or adjective, of low frequency (39/176 = 22%; 60/277 = 22%) in comparison to the pervasive locative phrases, and that the new reading, due to the competition of the two verbal items in this area of the grammar, influenced the way middle ver started to be processed in the same type of uses. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | DLE (n.d.), s.v. ver: #17 prnl. Hallarse en algún lugar, estado o situación. Verse allí. Verse pobre, abatido. Sin.: estar, hallarse, encontrarse (‘To find oneself in some place, state or situation. Verse there. Verse poor, depressed. Sin.: be, find oneself, find oneself’). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | DLE, s.v. hallar: #9 prnl. Encontrarse en cierto estado. Hallarse atado, perdido, alegre, enfermo. Sin.: estar, encontrarse (‘To find oneself in a certain state. Hallarse tied, lost, happy, sick. Sin: be, find oneself’). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | DLE, s.v. ver: #21 prnl. Estar o hallarse en un sitio o lance. Cuando se vieron en el puerto, no cabían de gozo. Sin.: estar, hallarse, encontrarse (‘To be or find oneself in a place or situation. When they were in the harbour, they were beside themselves with joy. Sin.: be, find oneself, find oneself’); cf. (Moliner, 1998, s.v. ver): #12 Estar de la manera que se expresa. Se ve en la cumbre de su carrera (‘To be the way it is expressed. He is at the top of his career’). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | Hallarse is categorized as a stative aspectual semicopula in Morimoto and Pavón Lucero (2007, p. 26). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | We studied the variation between ser, estar, and verse + obligado/a(s) in data from CORDE and CORPES XXI. The years 1480 to 1490 furnished no example of verse (0 in a total of 743 tokens). The later texts allowed us to catch a glimpse of the gradual encroachment of verse on the territory of the copulas: 1660–1690 (52/239 = 22%); 1880–1885 (175/454 = 39%); 2010 (337/547 = 62%). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | This is the change we announced in note 9. Obligado along with other semantically related modal participles, like necesitado ‘in need of’, constreñido ‘compelled, obliged’, compulsado ‘compelled’, precisado ‘forced, obliged’, and forzado ‘forced’ come to represent approximately a third of the middle tokens (17th cent.: 18/54 = 33%; 19th cent.: 68/174 = 37%; 20th–21st cent: 32/115 = 29%), with the other semantic classes discussed above covering the rest of the samples. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||