Abstract

LexTALE has emerged as a popular measure of language proficiency in research studies. While it has been widely validated for L2 learners across multiple languages, its applicability to heritage language learners (HLLs)—who often show distinct language development from L2ers—has not been established. Here, we evaluate the Spanish version of LexTALE (LexTALE-Esp) as a predictor of writing proficiency among college-aged HLLs in the United States. We show that LexTALE-Esp scores significantly correlate with ACTFL-rated functional writing levels and outperform self-assessment as a predictor of proficiency. Our results suggest that, despite concerns about HLLs’ limited experience with written texts in the heritage language, vocabulary-based tasks capture core aspects of written language ability. These findings indicate that vocabulary-based tests like LexTALE-Esp capture proficiency-relevant lexical knowledge across speaker profiles and may tap into dimensions of both core and extended language competence.

1. Introduction

Language proficiency, a multifaceted construct, lies at the heart of language acquisition research. The accurate measurement of proficiency holds significant implications across educational, pedagogical, linguistic, and theoretical domains. Employing appropriate assessment tools is not merely beneficial but essential for various aspects of the field, ranging from the development of robust linguistic theories to the effective placement of language learners. While the importance of accurately measuring language proficiency is widely recognized, the methods for doing so present various challenges. These challenges are particularly pronounced for heritage language learners (HLLs), who exhibit distinct acquisition patterns compared to traditional second language (L2) learners due to their early naturalistic exposure to the language in home settings. Comprehensive language proficiency assessments, such as those developed by ACTFL (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages) or the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, revolve around the notion of functional proficiency, or the ability to use language effectively in real-world contexts across various communicative tasks (ACTFL, 2024). However, these tests, despite their accuracy, often prove impractical for widespread implementation due to cost and the fact that they are time-consuming to administer. Consequently, researchers frequently resort to a myriad of alternative measures. Many of these alternatives, however, have not been rigorously validated against reliable standards, or in some cases, are known to be unreliable, such as self-ratings of language proficiency (Park et al., 2022). This situation underscores the need for efficient yet dependable assessment tools, and as Fairclough (2012, p. 122) emphasizes, “assessment measures [for HLL] need to be grounded in theories of individual and societal bilingualism.”

In response to this need, the LexTALE (Lexical Test for Advanced Learners of English) emerged as a promising alternative for measuring L2 proficiency in English (Lemhöfer & Broersma, 2012). This test offers a fast, cost-efficient, and reliable method of assessment based on vocabulary knowledge. Following its success, similar tests have been developed for at least seven additional languages. However, a significant gap remains in the literature: none of these tests have been validated for use with HLLs.

In line with Valdés (2005) who defined HLLs in the U.S. context, the present article defines heritage language learners as individuals who (a) grew up in a household where a language other than English was used, (b) may either speak or simply comprehend that language, and (c) consequently possess varying degrees of bilingual ability (p. 411)1. This definition highlights key characteristics that result in HLLs presenting a distinct acquisition and developmental trajectory compared to traditional L2 learners. While proficiency alone is not a definitive factor in distinguishing between L2 and HLLs, proficiency assessment tools that rely heavily on metalinguistic knowledge—such as grammaticality judgments—might work for L2 learners but not HLLs (Zyzik, 2016), a discrepancy that arises from the unique language learning experiences and exposure patterns characteristic of HLLs mentioned above.

LexTALE offers a better alternative that avoids tapping into metalinguistic knowledge but, being a vocabulary test that relies on reading words, it raises concerns for a different reason: HLLs often have limited experience with the written form of their heritage language. However, some research suggests that vocabulary tests can accurately reflect overall language proficiency, even for this population (Fairclough, 2011; Polinsky, 2006). This apparent contradiction warrants further investigation.

One useful lens for examining this tension is Hulstijn’s (2011, 2015, 2024) theory of Basic and Extended Language Cognition (BLC/ELC). According to this framework, BLC encompasses frequently used lexical and grammatical knowledge acquired through oral communication in everyday contexts, while ELC refers to less frequent, more academic language typically acquired through formal instruction. This distinction is particularly relevant for heritage speakers, who often exhibit strong BLC but limited ELC due to their home-based, oral exposure to the heritage language (Treffers-Daller, 2025; Zyzik, 2016). Hulstijn’s theory has been proposed as a useful framework for capturing the asymmetries in HL competence and for identifying pathways to developing more advanced abilities, especially in writing. Viewed through this lens, LexTALE can be understood as testing knowledge that lies at the intersection of BLC and ELC: while many of the lexical items fall within BLC due to their frequency, the written format and presence of low-frequency words also tap into ELC. As such, the theory helps explain why LexTALE has shown utility in differentiating proficiency levels in both L1 and L2 populations and offers a compelling rationale for testing its validity with heritage learners.

This article addresses the aforementioned gap in the literature by examining whether the LexTALE-ESP (the Spanish version of the LexTALE, Izura et al., 2014) accurately measures Spanish proficiency among HLLs. By doing so, we aim to contribute to the ongoing discussion on appropriate proficiency assessment tools for diverse language learner populations and to provide insights that may inform both research methodologies and educational practices in the field of heritage language studies.

2. LexTALE: A Multilingual Review

The English version of LexTALE was the first to be developed and validated, and it has served as the blueprint for subsequent versions in other languages. These later adaptations, including LexTALE-Esp, were designed to preserve the original test’s core format and underlying construct—lexical decision as a proxy for vocabulary knowledge—while adjusting for language-specific considerations such as cognate status, orthographic transparency, and corpus availability. For instance, the Spanish version draws from a subtitle corpus (Cuetos et al., 2012), while the English version relies on word frequency norms derived from native-speaker corpora (Lemhöfer & Broersma, 2012). Additionally, item counts may vary across versions (e.g., 60 items in English, 90 in Spanish) depending on test design and validation procedures. While the tests are not identical, they share a common goal: to provide a fast, low-cost measure of general lexical proficiency that can be adapted to a variety of learner populations and research contexts. In the following section, we first review the English version, followed by adaptations in other languages that reflect both shared principles and context-specific design choices.

The original LexTALE (Lemhöfer & Broersma, 2012), now widely adopted across SLA research with over 550 studies in the past decade (Puig-Mayenco et al., 2023), was designed as a quick and practical vocabulary test consisting of 60 lexical decision items. It was initially validated using the Quick Placement Test (QPT), a translation task, and TOEIC scores (for a subset of Korean participants). These validation tools, especially the QPT—a grammar- and vocabulary-focused multiple-choice test aligned with CEFR—tend to emphasize metalinguistic knowledge typically acquired in formal instruction. This may disadvantage HLLs, who often develop proficiency through naturalistic exposure in home and community settings. Additionally, the study found that LexTALE scores correlated more strongly with proficiency measures among L1 Dutch speakers than among L1 Korean speakers, highlighting how linguistic distance and speaker profile can influence test performance—an issue particularly relevant for the heterogeneous linguistic backgrounds of HLLs.

LexTALE-Esp (Izura et al., 2014) was developed following the general structure of the original English LexTALE, but with several modifications to improve test quality and cross-group validity. The authors began with a larger item pool (90 words and 90 nonwords), narrowing it down to 50 words and 30 nonwords based on psycholinguistic criteria and pilot data. Special attention was given to nonword selection: overly easy nonwords could allow test-takers to guess without knowing the language, while pseudohomophones could create ambiguity even for proficient speakers. The final version was validated with both L1 and L2 Spanish speakers, including graduate students at the University of Oviedo, Spain (L1) and L2 learners from institutions in Swansea and Antwerp, with a range of L1 backgrounds. These features make LexTALE-Esp structurally comparable to the English version, while accommodating the linguistic characteristics of Spanish and the diversity of its speaker populations.

LexTALE’s adaptations across multiple languages demonstrate its versatility as a proficiency assessment tool, with each version tailored to address language-specific characteristics and testing contexts. These cross-linguistic adaptations are particularly relevant when considering LexTALE’s potential application to heritage language assessment, as they illustrate how the test can be modified to accommodate different linguistic needs. Each validation process has employed diverse methodological approaches that warrant further examination. Table 1 reviews how LexTALE variants have been validated across different languages and speaker populations.

Table 1.

Overview of LexTALE adaptations across languages, including validation methods and the populations used in each version’s evaluation.

Themes such as bilingual profile of the test-takers, non-standard variety assessment, vocabulary selection, and validation across proficiency levels are all relevant to our study of heritage Spanish learners. By considering these factors, we aim to create a framework that allows us to understand why the LexTALE-ESP could serve as an accurate measure of Spanish proficiency in this unique population (or not), contributing to more effective and inclusive language assessment methods.

Test-taker characteristics shape how vocabulary tests like the LexTALE measure language proficiency, making it crucial to validate these instruments for specific populations. Studies consistently show that L1 speakers outperform L2 speakers on LexTALE tests across multiple languages (e.g., Arabic: Alzahrani, 2023; Spanish: Izura et al., 2014). However, it is important to recognize two distinct patterns of variability. First, even within L1 speakers, performance is not uniform—a study of Chinese speakers demonstrates that native speakers’ performance varies with age and literacy levels (Qi et al., 2024). Second, L2 speakers exhibit a broader spectrum of proficiency levels, with an additional layer of complexity: their performance variability is often influenced by their L1 background. As Lemhöfer and Broersma (2012) observed, the same LexTALE might show stronger or weaker correlations with proficiency scores depending on the subjects’ L1. These patterns highlight the need to consider specific population characteristics when validating vocabulary assessments.

While proficiency comparisons between L1 and L2 speakers present certain challenges, the complexity increases when examining heritage language speakers, especially in minority language contexts. The case of Sicilian offers particularly relevant insights for understanding heritage language contexts, including Spanish in the United States. In both situations, the minority language (Sicilian or Spanish) is primarily spoken at home while the majority language (Italian or English) dominates other domains. Research comparing Sicilian speakers in Sicily with those in diaspora demonstrates how linguistic context affects proficiency measurement (Kupisch et al., 2023). Notably, proficiency predictors differed between these groups: while Italian vocabulary test scores predicted Sicilian proficiency for both groups, Sicilian use at home was only predictive for the diaspora group. This difference likely arises from the homeland group’s broader exposure to Sicilian outside the home, whereas the diaspora group has limited exposure. Collectively, these findings emphasize the importance of considering the population’s specific characteristics when administering LexTALE. Factors like L1 background and daily use of the target language influence how LexTALE scores correlate with other proficiency measures.

Regarding vocabulary selection, word frequency and discrimination power form the foundation of item selection in LexTALE tests across languages. The selection process typically begins with frequency-based sampling from established corpora, where words are drawn from different frequency bands to ensure representation across proficiency levels. While high-frequency words are included, many versions of the test prioritize lower-frequency items to better discriminate between proficient and less-proficient speakers. However, frequency alone does not determine a word’s inclusion in the final test version. Items must also demonstrate adequate discrimination power, typically measured through point-biserial correlations, to effectively differentiate between high and low performers.

Beyond these fundamental criteria, LexTALE adaptations often incorporate language-specific considerations. Word type is carefully controlled, with most versions focusing on content words (nouns, adjectives, and verbs) while excluding proper nouns and multi-word expressions. The treatment of cognates varies across adaptations: while some versions specifically exclude cognates to ensure fairness across different language backgrounds, others carefully balance their inclusion. Similarly, orthographic overlap with translations in relevant contact languages may influence word selection, particularly in contexts where cross-linguistic influence is significant. For Spanish heritage speakers, these selection criteria raise important considerations. Given that HLLs often develop their Spanish vocabulary primarily through oral input in domestic contexts, the relationship between corpus frequency and actual word familiarity may differ from that of L2 learners who acquire Spanish through formal instruction.

Finally, the validation of LexTALE adaptations reflects both the challenges and opportunities in developing standardized proficiency measures across languages. While established standardized tests exist for some languages (e.g., TOEFL for English, DELE for Spanish, DELF for French), no single standardized measure is available across all languages for which LexTALE has been adapted. This variation in available validation tools has led to diverse approaches across adaptations, potentially affecting cross-language comparability while simultaneously demonstrating the test’s adaptability to different linguistic contexts.

A review of validation measures across LexTALE adaptations reveals three main approaches. The first relies on standardized proficiency tests, such as the Oxford Quick Placement Test for the original English version (Lemhöfer & Broersma, 2012) or institutional placement tests as seen in the Arabic adaptation (Alzahrani, 2023). The second approach employs direct language tasks, particularly translation tasks and cloze tests, as evidenced in several adaptations, including Malay (Lee et al., 2023) and Chinese (Wen et al., 2023). The third and most common approach across all versions incorporates self-assessment measures, ranging from general proficiency ratings on various scales (7-point to 11-point) to more specific evaluations of language use patterns and learning history.

For heritage language contexts, the choice of validation measure requires particular consideration. Traditional proficiency tests like the QPT, which were designed for L2 learners, often assess metalinguistic knowledge acquired through formal instruction. Such measures may not effectively capture HLLs’ language knowledge. More recent adaptations have begun to address similar challenges by incorporating alternative validation measures. For instance, the Sicilian version (Kupisch et al., 2023) emphasized language use patterns, while the Finnish adaptation (Salmela et al., 2021) included educational achievement metrics. These approaches suggest the need to identify validation measures that align with how HLLs acquire and use language.

3. Heritage Language Learners and Proficiency

Heritage language learners exhibit remarkable within-group diversity, shaped by a range of intersecting factors. Among these, proficiency stands out as both a defining characteristic and a dynamic outcome. It is central to many foundational definitions of HL speakers (e.g., Benmamoun et al., 2013; Valdés, 2005; Zyzik, 2016), yet it also emerges as a product of other influences, such as the context of acquisition, language use, educational experiences, and age of arrival: “students exhibit a wide range of dialects, relating to their many cultures of origin, varying length of residency in the United States, and the particular language, social class, and educational variables of their families and communities” (González Pino & Pino, 2005, p. 170). This interplay of factors underscores the complexity of proficiency within HL populations, making it a pivotal focus for researchers and educators alike.

While previous studies have shown that various LexTALE versions correlate significantly with independent proficiency measures in both L1 and L2 populations, their effectiveness for HLLs remains unexplored. This gap is particularly significant given that HLLs differ markedly from L2 speakers in their linguistic profiles—from phonology to morphosyntax to lexicon (Benmamoun et al., 2013)—and often use language varieties that diverge from the standardized forms typically represented in LexTALE tests (Shanley et al., 2025). Given these unique characteristics and the heterogeneous nature of HLLs, presenting a “puzzling range of possible outcomes,” (Ortega, 2009, p. 2) it becomes crucial to examine whether LexTALE can effectively assess HLL proficiency as it does for L1 and L2 speakers.

Several lines of research suggest that LexTALE could effectively assess HLLs’ proficiency levels. Early studies using yes/no vocabulary tasks with heritage speakers of Russian (Polinsky, 2006) and Spanish (Fairclough, 2011) found strong correlations between lexical knowledge and other proficiency measures, establishing vocabulary recognition as a reliable indicator of overall language competence. This finding has been reinforced by recent LexTALE validation studies including regional varieties: Zhou and Li (2021) demonstrated that LexPT can successfully assess speakers of different language varieties (European and Brazilian Portuguese)—a crucial consideration for heritage speakers who often use non-standard varieties—while Kupisch et al. (2023) found that LexTALE scores for heritage speakers of Sicilian correlated with their language use patterns. Further support comes from written and oral functional proficiency studies of heritage speakers across multiple languages (Gatti & O’Neill, 2018; Swender et al., 2014), which identified vocabulary knowledge as a key determinant of proficiency levels, particularly at the intermediate level where heritage speakers consistently showed lexical limitations in topics beyond daily communication. Collectively, these findings suggest that a vocabulary recognition task like LexTALE-Esp could be a valid instrument for measuring Spanish HLLs’ proficiency.

Despite these promising indicators, three critical factors warrant investigation before confirming LexTALE-Esp’s validity for HLLs. The first concern relates to the test’s reading-based format. HLLs typically complete their formal education in the majority language, resulting in limited literacy development in their heritage language (Carreira & Kagan, 2011; Jensen & Llosa, 2007). Although recent research with Spanish HLLs suggests that the gap between their oral and written abilities may be minimal (Gatti & Graves, 2020), the impact of literacy skills on LexTALE performance remains unclear. A second, more complex challenge lies in the linguistic variation among HLLs. Unlike monolingual contexts, heritage Spanish in the United States represents multiple varieties influenced by different countries of origin and extensive contact with English, leading to varied borrowing phenomena and dialectal features. While other LexTALE versions, such as the Portuguese adaptation, have successfully incorporated major varieties (Zhou & Li, 2021), the Spanish version was developed exclusively in Spain (Izura et al., 2014) without aiming for validity across different Spanish varieties and has yet to address this linguistic diversity. Third, the validation methods employed for certain LexTALE versions present challenges when applied to HLLs. Some tests were validated using self-assessed proficiency measures (e.g., Brysbaert, 2013; Chan & Chang, 2018; Izura et al., 2014), which are known to be unreliable indicators of proficiency in this population (Gatti & Graves, 2020; Gatti & O’Neill, 2017; Swender et al., 2014; Tomoschuk et al., 2019). Additionally, other studies relied on proficiency measures rooted in metalinguistic knowledge –such as the QPT for English—an approach that can be equally problematic for accurately assessing HLLs (Zyzik, 2016). These considerations underscore the necessity of empirically validating LexTALE-Esp specifically for HLLs before implementing it as a proficiency measure for this population.

Functional proficiency—the ability to communicate effectively in real-world situations through spontaneous, non-rehearsed interactions—provides an ideal framework for validating the LexTALE-Esp with HLLs. While previous LexTALE adaptations have relied heavily on standardized L2 proficiency tests, self-assessments, or metalinguistic tasks, these approaches may not adequately capture HLLs’ language knowledge. Our study employs the ACTFL Writing Proficiency Test (WPT) alongside the LexTALE-Esp for two key reasons. First, since the LexTALE-Esp is presented in written form, a writing proficiency test aligns better with the literacy skills being measured than an oral task would. Second, as we work with college-level learners, the WPT is particularly appropriate as it can effectively assess the written language development relevant for academic contexts. This approach is particularly appropriate for HLLs, whose language acquisition typically occurs through natural exposure rather than formal instruction. The WPT, a criterion-based tool, arrives at ratings by simultaneously evaluating function, context, text type, and accuracy, placing meaning at the center of assessment rather than metalinguistic knowledge—a key consideration when working with HLLs. Research has consistently validated the WPT’s effectiveness with HLLs, demonstrating that the tool can provide accurate proficiency ratings without discriminating against HLLs’ linguistic choices (Martin et al., 2013). While comparative studies have identified some performance differences between heritage and L2 learners at the same proficiency level—such as heritage speakers showing greater fluency in informal contexts (Kagan & Friedman, 2003) and more code-switching (Ilieva, 2012)—these differences do not affect the overall validity of the ratings.

4. The Study

The accurate measurement of language proficiency is crucial for both research and pedagogical purposes. Among available tools, vocabulary tests like LexTALE have gained prominence due to their practicality and reliability in estimating overall proficiency for grouping research participants. While researchers have begun applying the Spanish adaptation (LexTALE-Esp) to heritage language learners (e.g., Casper et al., 2024; Ortín, 2024), most LexTALE versions were developed and validated primarily with traditional L2 learners. The only exception has been the Sicilian adaptation, which explicitly included heritage speakers in its validation process (Kupisch et al., 2023). This gap is significant because the distinct language acquisition trajectories of L2 learners and HLLs may affect how accurately these tools capture proficiency.

The present study investigated whether vocabulary-based and self-reported measures of language proficiency are associated with functional writing performance among HLLs. Specifically, we asked:

- (1)

- To what extent do LexTALE-Esp scores and self-assessed proficiency correlate with ACTFL-rated writing proficiency in HLLs?

- (2)

- To what extent is LexTALE-Esp a stronger predictor of writing proficiency in HLLs than self-assessed proficiency when both are included in the same model?

To address these questions, we used ACTFL’s WPT as a benchmark of functional writing ability, given its holistic assessment of performance on real-world communicative tasks. If vocabulary knowledge, as assessed by LexTALE-Esp, is a strong indicator of language ability in HLLs, we would expect a significant positive association with WPT scores—potentially stronger than for self-assessment. Conversely, a weak or inconsistent relationship would suggest that vocabulary-based tests originally developed for L2 learners may not adequately reflect the competencies required for functional writing in this population.

Additionally, self-assessment is widely used due to its convenience, but its validity can be compromised by subjective bias or mismatches between perceived and actual skill—particularly among bilinguals who often have complex relationships with their heritage language (Tomoschuk et al., 2019). Comparing its predictive power to that of LexTALE-Esp offers insight into whether a vocabulary test may serve as a more reliable, low-cost alternative for assessing writing-related language proficiency among HLLs. Findings have implications for both research methodology and pedagogical practice.

5. Methods

5.1. Participants

All students enrolled in the Spanish as a Heritage Language track at an urban Hispanic-Serving Institution were recruited to participate (n = 126). Several students were excluded from the analysis for various reasons: absence from one or both data collection sessions, immigration to the U.S. after the age of 15, or having Cantonese as their heritage language. The final sample included 96 students who completed all tasks. The heritage track consists of a four-semester sequence, although only three courses are offered concurrently. At the time of data collection, the first, second, and fourth levels were taught. Students enroll in these courses to fulfill language requirements or to meet prerequisites for the Spanish BA, minor, or translation certificates. While all participants were formally enrolled in a heritage language course, their placement into specific levels was determined by an in-house placement test that does not always accurately reflect students’ prior coursework or actual proficiency. As a result, enrollment in higher-level courses (e.g., fourth semester) does not necessarily imply that students have completed multiple semesters of formal Spanish instruction.

5.2. Materials

5.2.1. Background Questionnaire

The first part involved a background questionnaire where students provided consent to participate in the study and supplied information about their age, gender, parental country(ies) of origin, languages spoken by their parents, age of arrival in the U.S., education in a Spanish-speaking country (if applicable), preferred languages, self-assessment of Spanish writing ability (via ACTFL can-do statements), and frequency of Spanish and English use in different contexts (home, work, school, friends). Full questionnaire is available in Appendix A.

While prior LexTALE studies have used a range of self-assessment formats—including 7- and 10-point scales—our use of an ACTFL-aligned 4-point scale reflects both the framework of the WPT and the U.S. instructional context in which our participants were situated. Given these differences in scale structure and learner population, we interpret self-assessment outcomes as meaningful primarily within-group, rather than for cross-study or cross-population comparisons. Although the reduced number of levels may limit the scale’s sensitivity—especially around sublevel transitions—recent work has shown that self-assessments are more reliable to distinguish between major levels, rather than sublevels (Tigchelaar et al., 2017).

5.2.2. LexTALE

Participants’ vocabulary knowledge was measured using the Lexical Test for Advanced learners of Spanish (Izura et al., 2014) via a lexical decision task. Participants saw a string of letters on the screen and were asked to decide whether this string was a real word in Spanish or not. The test included 12 practice trials and 90 lexical items (60 words and 30 pseudowords), was programmed on PsychopPy (adapted from Garrido & Casillas, 2024), and hosted on GitLab and delivered through Pavlovia.

5.2.3. Writing Proficiency Test (WPT)

The WPT is a timed, criterion-referenced assessment that provides a rating based on the 2024 ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines, ranging from Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, to Superior, with sublevels of Low, Mid, or High for all major levels except Superior. The test evaluates performance across five criteria: functions (what one can do with the language), context/content (contexts and topics on which the functions are performed), accuracy (precision of language in terms of comprehensibility), and text type (organization of language). The test was administered through the online platform from Language Testing International. The platform prevents students from using external aids (dictionaries, spell-check, etc.) by locking them out if they leave the browser.

5.3. Procedure

Students completed all tasks during class time in two sessions, either in a computer lab (for four in-person sections) or on their personal computers (for two online sections). The first session lasted 20 min and included a background questionnaire (administered via Qualtrics) and the LexTALE test (administered via the behavioral experiment platform Pavlovia). The second session lasted 75 min and involved the WPT, delivered through the official Language Testing International platform. All tests were proctored by one or more researchers.

5.4. Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R Version 4.5.0 using the DescTools, MASS, and ggplot2 packages. Significance was evaluated at α = 0.05. To examine whether LexTALE-Esp scores correlate with functional writing proficiency, we first computed Spearman’s rank-order correlations between LexTALE-Esp scores and WPT ratings. Spearman’s correlation was chosen due to the ordinal nature of the WPT proficiency levels. We then assessed whether self-reported proficiency exhibited similar correlations with WPT scores by computing the same correlation coefficient between self-assessed writing proficiency and WPT ratings. This allowed us to compare the relative strength of the relationships between each predictor and functional writing proficiency.

To further investigate the predictive value of LexTALE-Esp and self-assessment, we conducted an ordinal logistic regression analysis using WPT proficiency levels as the dependent variable. This model examined whether LexTALE-Esp scores significantly predicted WPT performance while controlling for self-reported proficiency. To determine the relative contribution of each predictor, we compared the full model—including both LexTALE-Esp and self-assessed proficiency—to reduced models where each predictor was entered separately.

Scoring the LexTALE-Esp

LexTALE-Esp scores were calculated following the standard lexical decision task scoring approach, which evaluates both word recognition accuracy and the ability to reject nonwords. This method, originally developed for LexTALE (Lemhöfer & Broersma, 2012) and adapted for Spanish as LexTALE-Esp (Izura et al., 2014), ensures that scores reflect lexical knowledge while accounting for response biases common in lexical decision tasks (Brysbaert, 2013). The score was computed using the following formula:

where Ncorrect real words represents the number of correctly identified real words, and Ncorrect nonwords represents the number of nonwords correctly rejected. The final score is the average of the accuracy on real words and nonwords, expressed as a percentage. This method ensures that both lexical recognition and lexical rejection contribute equally to the overall score.

Score = ((Ncorrect real words/Nreal words × 100) + (Ncorrect nonwords/Nnonwords × 100)) ÷ 2

6. Results

6.1. Demographic and Bilingual Profile

Most students were female (76.5%), with 22.6% male and 0.98% preferring not to disclose their gender. The mean age of participants was 20.3 years (SD = 2.3, range 18–33). Of the total participants, 23.5% were not born in the U.S., as indicated by a non-zero age of arrival in the U.S. Among this subgroup, the mean age of arrival was 7.21 years (SD = 4.53), with ages ranging from 1 year to 15 years. A total of 17.6% of participants reported attending school in a Spanish-speaking country. The countries represented include the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Puerto Rico, Peru, Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela. These findings highlight the diverse educational and immigration experiences within the sample.

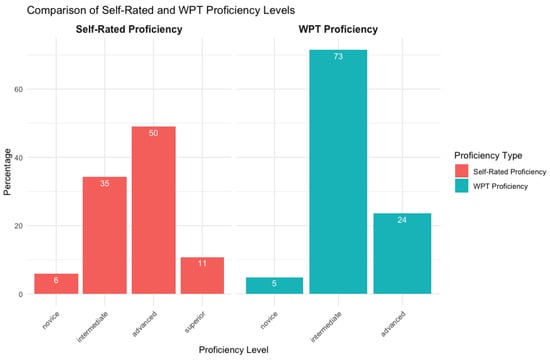

Participants self-rated their Spanish writing proficiency on a scale ranging from Novice to Superior using ACTFL Can-do Statements (see Appendix A). The average self-rated proficiency score was 2.65 (SD = 0.75) on a 4-point scale, with 1 representing Novice and 4 representing Superior. The most common proficiency level selected was Advanced, reported by 49.0% of participants, followed by Intermediate (34.3%), Superior (10.8%), and Novice (5.88%)2. These results suggest that most participants perceive themselves as having moderate to high proficiency in Spanish, with a small proportion identifying at the lowest or highest levels of the scale. This is in contrast with their WPT functional writing proficiency levels, which show that the vast majority are at the Intermediate level (73%), with only 5% at the Novice, 24% at the Advanced level, and none reaching Superior.

The linguistic diversity of participants’ families is reflected in the countries of origin of their parents. The most represented countries among mothers include the Dominican Republic (31 participants), Mexico (29 participants), and Ecuador (16 participants). Fathers’ countries of origin show a similar trend, with the largest groups coming from Mexico (29 participants), the Dominican Republic (27 participants), and Ecuador (15 participants). Other Spanish-speaking countries, such as Guatemala, Colombia, Peru, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Puerto Rico, were also represented. Notably, non-Spanish-speaking countries, including the United States, Guyana, and Haiti, contributed to participants’ linguistic diversity.

Table 2 presents the distribution of languages spoken by the parents of participants, reflecting the rich bilingual and multilingual environments many participants experienced growing up. The most reported language spoken by both mothers (72.55%) and fathers (63.73%) was Spanish, highlighting the strong influence of Spanish-speaking heritage within the sample. Additionally, a substantial proportion of parents (26.47% for both mothers and fathers) were reported to speak both English and Spanish, indicating bilingual proficiency.

Table 2.

Parental countries of origin.

Interestingly, only a small percentage of mothers (0.98%) and fathers (5.88%) were reported to speak exclusively English, suggesting that English-only households were relatively rare in this sample (see Table 3). These findings highlight the bilingual and Spanish-dominant environments shaping participants’ language development and use, providing valuable context for understanding their linguistic experiences.

Table 3.

Languages spoken by parents.

Participants reported their language preferences, showcasing the flexibility and variability in their bilingual language use. The majority of participants (58.8%) indicated that their language preference “depends on who they talk to,” highlighting the importance of social and situational factors in bilingual communication. Additionally, 26.5% of participants reported using both English and Spanish equally, indicating that the speakers in the sample perceive their bilingualism as mostly balanced. A smaller percentage of participants expressed a clear preference for either English (9.8%) or Spanish (4.9%). These findings underscore the dynamic nature of bilingual language preferences, influenced by both individual and contextual factors.

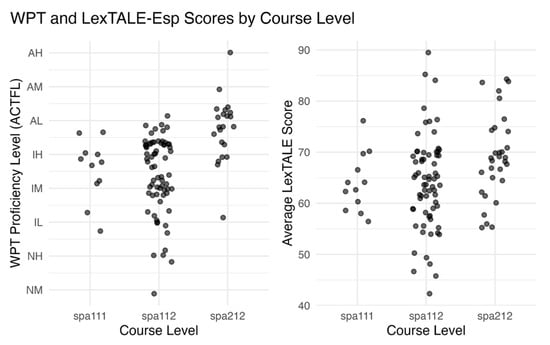

Although all participants were enrolled in one of three heritage language courses—corresponding to the first, second, and fourth levels of the track—their actual proficiency levels varied considerably, both in terms of vocabulary knowledge and functional writing ability. Figure 1 shows the distribution of LexTALE scores and WPT proficiency levels across course levels. As the plots illustrate, students placed in the same course displayed a wide range of proficiency outcomes, and students in higher-level courses did not consistently outperform those in lower-level ones.

Figure 1.

Distribution of WPT proficiency levels (left) and LexTALE-Esp scores (right) by course level in the heritage language program. SPA111 corresponds to the first semester, SPA112 to the second semester, and SPA212 to the fourth semester.

6.2. Distribution of LexTALE-Esp Scores Across WPT Proficiency Levels

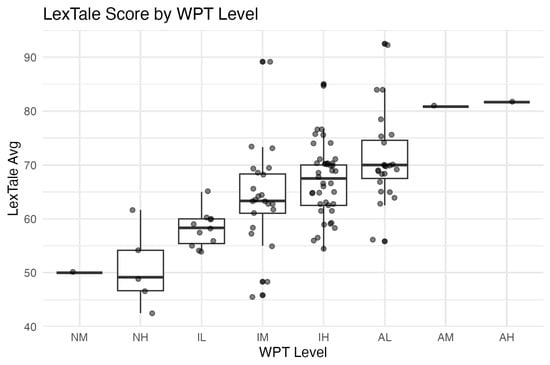

The relationship between LexTALE-Esp and WPT scores is examined through correlation and regression analyses in the following sections. Figure 2 presents the distribution of LexTALE-Esp scores across WPT levels. Each boxplot represents the spread of LexTALE-Esp scores within each proficiency category, with individual data points overlaid. The figure shows a general trend in which LexTALE-Esp scores increase with higher WPT proficiency levels, suggesting a positive relationship between vocabulary knowledge, as measured by LexTALE-Esp, and functional writing proficiency. However, some overlap exists between adjacent WPT levels, particularly in the Intermediate-Mid to Intermediate-High range, indicating that LexTALE-Esp scores alone may not fully differentiate between certain proficiency sublevels. The distribution of students across WPT proficiency levels is uneven, with the majority falling within the Intermediate-Mid to Advanced-Low range. In contrast, fewer students are classified at the Novice-Mid, Novice-High, and Advanced-Mid or Advanced-High levels, indicating that extreme proficiency levels—both lower and higher—are less represented in this sample.

Figure 2.

Distribution of LexTALE-Esp scores across WPT proficiency levels, with individual data points overlaid. Central horizontal line within each box indicates the median score, and boxes represent the interquartile range (i.e., the middle 50% of scores). Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range, and individual points outside this range represent potential outliers.

6.3. Strength of Association: LexTALE-Esp and Self-Assessment vs. WPT Ratings

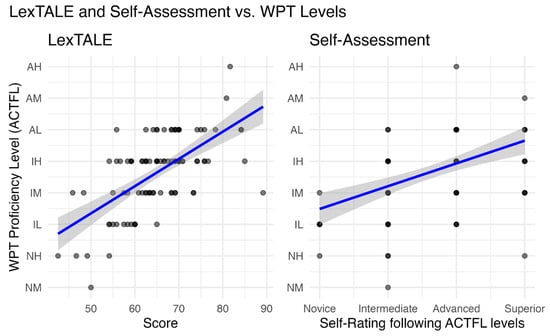

To independently assess the relationship between two different proficiency measures—LexTALE-Esp and self-assessment—and an externally rated indicator of functional writing proficiency, we computed separate Spearman’s rank-order correlations between each predictor and WPT ratings. Spearman’s correlation was selected because WPT proficiency levels are ordinal, representing ranked categories without assuming equal intervals. LexTALE-Esp scores showed a moderate-to-strong positive correlation with WPT ratings, ρ = 0.59, p < 0.001, indicating that individuals with higher LexTALE-Esp scores tended to be rated at higher levels of functional writing proficiency. In contrast, self-assessed proficiency showed a weaker but still significant correlation with WPT ratings, ρ = 0.48, p < 0.001, suggesting that while both measures are positively associated with writing proficiency, LexTALE-Esp aligns more closely with the external proficiency benchmark (see Figure 3 for a visual comparison of self-rated and WPT proficiency distributions).

Figure 3.

Comparison of self-rated Spanish proficiency and proficiency levels based on the Writing Proficiency Test (WPT). Percentages of participants for each level are displayed inside the bars.

6.4. Predictive Power: Evaluating LexTALE-Esp and Self-Assessment

While correlation assesses how closely two variables are related, regression evaluates their unique contributions to predicting an outcome. To determine whether LexTALE-Esp is a stronger predictor of functional writing proficiency than self-assessed proficiency, we conducted an ordinal logistic regression with WPT proficiency level as the dependent variable and both LexTALE-Esp scores and self-assessed proficiency as predictors. Because these measures were on different scales, we standardized both variables to allow direct comparison of their effects.

The model showed a good fit, with a McFadden’s R2 of 0.19, indicating that approximately 19% of the variance in WPT proficiency ratings was accounted for by the predictors. LexTALE-Esp significantly contributed to the model, β = 1.39, SE = 0.26, Wald χ2 = 29.24, p < 0.001. The odds ratio was Exp(β) = 4.01, 95% CI [2.42, 6.63], indicating that for every one standard deviation increase in LexTALE-Esp, participants were approximately four times more likely to be rated at a higher WPT level. Self-assessed proficiency also significantly predicted writing proficiency, β = 0.76, SE = 0.21, Wald χ2 = 12.96, p < 0.001, with an odds ratio of Exp(β) = 2.14, 95% CI [1.42, 3.24]. This means that for every one standard deviation increase in self-assessed proficiency, participants were more than twice as likely to be rated at a higher WPT level. These results suggest that both vocabulary knowledge and self-perceived ability are positively associated with functional writing proficiency, though LexTALE-Esp was the stronger predictor.

The patterns observed in Figure 4 visually support the regression findings. The LexTALE-Esp plot shows a strong positive relationship with WPT proficiency, with a steadily increasing trend and relatively low variance across levels, indicating a consistent alignment between vocabulary knowledge and functional writing proficiency. In contrast, the Self-Assessment plot also shows a positive trend but with greater variability and a less steep progression, suggesting that self-reported proficiency does not differentiate WPT levels as effectively. This visual representation reinforces the statistical results, where LexTALE-Esp emerged as a stronger predictor of writing proficiency than self-assessment among HLLs.

Figure 4.

Relationship between LexTALE-Esp and Self-Assessment scores with WPT proficiency levels. The blue line represents the trend for each predictor, with shaded areas indicating confidence intervals.

7. Discussions

This study aimed to assess whether LexTALE-Esp (Izura et al., 2014) is a measure of writing proficiency among Spanish HLLs. Answering this question is methodologically and pedagogically relevant because an increasing number of researchers are using this test with HLLs despite uncertainty about its efficacy for this notably heterogeneous population. To address this question, we evaluated how well two commonly used proficiency measures—LexTALE-Esp and self-assessed proficiency—align with functional writing ability among HLLs of Spanish. Specifically, we examined whether each measure correlated with ACTFL-rated WPT and whether LexTALE-Esp was a stronger predictor than self-assessment when both were considered simultaneously. The results revealed that both LexTALE-Esp and self-assessed proficiency were significantly and positively associated with WPT ratings. However, LexTALE-Esp demonstrated a stronger correlation with writing proficiency and emerged as the more robust predictor of functional writing proficiency. These findings suggest that vocabulary-based measures like LexTALE-Esp may offer a more accurate and objective estimate of functional writing ability in HLLs than self-reported proficiency, aligning with research showing that vocabulary size serves as a proxy for different proficiency measures among both native speakers and L2 learners. In the following sections, we discuss the implications of these findings for developing more appropriate assessment tools that account for the unique linguistic profiles of heritage language learners.

7.1. Understanding HLL Profile

Heritage language learners typically exhibit unpredictable linguistic development patterns (Fairclough, 2012), making it essential to understand the specific population being assessed. In our study at a Hispanic-Serving Institution in New York City, where approximately 50% of students are Hispanic, we found variation in Spanish proficiency levels. The majority of participants demonstrated Intermediate-Low to Advanced-Low proficiency, highlighting the heterogeneous nature of heritage language abilities. Our data also reveal a notable discrepancy between self-assessed and actual proficiency among heritage Spanish speakers. While the majority of participants (49.0%) rated themselves at the Advanced level and 10.8% considered themselves Superior, formal assessment through the WPT showed 73% were at the Intermediate level, with only 24% achieving Advanced proficiency and none reaching Superior. This pattern of overestimation aligns with established findings in heritage language research.

The tendency among HLLs to overestimate their proficiency has been consistently documented across multiple studies. Martin et al. (2013) found similar patterns in both Spanish and Russian heritage speakers, with half of Spanish Intermediate-level speakers self-assessing at Advanced, and all Russian Intermediate speakers claiming Advanced proficiency. Swender et al. (2014) similarly observed that while Advanced-level Russian heritage speakers were relatively accurate in their self-assessments (77% accuracy), those at other levels predominantly overestimated their abilities. Interestingly, Gatti and Graves (2020) identified a correlation between proficiency level and self-assessment accuracy, noting that higher proficiency speakers tend to be more accurate in evaluating their abilities. This phenomenon may explain why our self-assessment data showed greater distortion at intermediate levels and among those who rated themselves highest.

Understanding the linguistic profile of this population is therefore not only important for interpreting our findings, but also essential for evaluating the validity and applicability of the LexTALE-Esp as a proficiency measure for heritage speakers. These parallel findings from multiple studies suggest that the disparity between perceived and actual proficiency is a consistent characteristic across heritage language populations, highlighting the importance of objective assessment tools like LexTALE-Esp for research and educational purposes with this population.

7.2. LexTALE-Esp vs. Self-Assessment as Predictors of Writing Functional Proficiency

Our first research question examined whether LexTALE-Esp scores and self-assessed proficiency correlate with ACTFL-rated writing proficiency in Spanish HLLs. The analysis revealed that LexTALE-Esp scores showed a moderate-to-strong positive correlation with WPT ratings (ρ = 0.59, p < 0.001), indicating that individuals with higher vocabulary knowledge tended to achieve higher levels of functional writing proficiency. Self-assessed proficiency also correlated positively with WPT ratings, though more weakly (ρ = 0.48, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that while both measures are associated with writing proficiency, LexTALE-Esp provides a somewhat more accurate reflection of functional language abilities.

These correlation values are comparable to those reported in previous LexTALE validation studies. The original LexTALE-Esp (Izura et al., 2014) was validated against self-assessment measures, showing strong correlations (r = 0.82) across their combined sample, though with notable differences between L1 (r = 0.10) and L2 (r = 0.73) speakers. This disparity highlights the challenges in using self-assessment as a validation measure, particularly with heritage populations who may share characteristics with both L1 and L2 speakers. Similarly, Lemhöfer and Broersma (2012) demonstrated varying correlation patterns across different L1 backgrounds in their original English LexTALE study, with stronger correlations for Dutch participants than Korean participants.

Although our results indicate that LexTALE-Esp aligned more closely with WPT proficiency outcomes than self-assessed proficiency, we caution against dismissing the value of self-assessment more broadly. As research on L2 learners suggests (e.g., Ma & Winke, 2019; Winke et al., 2023), self-assessment can be a powerful pedagogical tool and a useful measure in low-stakes contexts, particularly when supported by training. However, prototypical heritage learners often operate in a narrower range of functional domains—successfully navigating home and community contexts while having limited exposure to academic or professional registers. This may lead to overestimation, especially when learners lack experience with tasks at the Advanced or Superior levels. Future studies could explore how self-assessment accuracy varies across populations and whether task-based or adaptive formats improve alignment in HL contexts.

Our second research question addressed whether LexTALE-Esp is a stronger predictor of writing proficiency than self-assessment when both are included in the same model. The ordinal logistic regression revealed that both measures significantly predicted WPT ratings, with LexTALE-Esp demonstrating moderately stronger predictive power. With an odds ratio of 4.01, each standard deviation increase in LexTALE-Esp scores made participants four times more likely to be rated at a higher WPT level, compared to the odds ratio of 2.14 for self-assessment. While this difference in predictive strength is noteworthy, it is important to acknowledge that the model explained approximately 19% of the variance in writing proficiency ratings, indicating that many other factors also contribute to functional writing ability.

A key contribution of our study lies in the methodological approach of validating LexTALE-Esp against the ACTFL Writing Proficiency Test, a criterion-referenced assessment of functional language ability. This extends beyond previous validations that primarily relied on other vocabulary measures, self-reports, or limited proficiency tests. For instance, Kupisch et al. (2023) validated LexSIC against another vocabulary measure (DIALANG), providing insights into the relationship between vocabulary knowledge across languages but not addressing functional language performance. Their findings with heritage speakers of Sicilian in the diaspora parallel our results with heritage Spanish speakers, reinforcing the potential utility of vocabulary tests for assessing proficiency in heritage populations. Similarly, while Zhou and Li (2021) attempted to validate LexPT against standardized proficiency tests (CAPLE and CELPE-Bras), their validation relied on participant-reported certification levels with acknowledged inconsistencies.

By demonstrating that vocabulary knowledge moderately predicts functional writing proficiency in heritage speakers, our findings suggest LexTALE-Esp as a potentially useful assessment tool for this population. The stronger predictive power of LexTALE-Esp compared to self-assessment suggests that objective vocabulary measures may better capture certain aspects of language competence in heritage speakers, whose self-evaluations might be influenced by factors such as language attitudes, identity considerations, and limited metalinguistic awareness.

7.3. Theoretical Implications of Vocabulary as a Proficiency Indicator in Heritage Learners

Our findings contribute to ongoing debates about the validity of vocabulary-based measures as indicators of overall language proficiency, particularly in HLLs. Vocabulary knowledge, as operationalized through LexTALE-Esp, significantly predicted writing proficiency in this population, supporting the notion that lexical knowledge plays a central role in functional language competence. This aligns with Hulstijn’s (2011, 2015, 2024) dual-component model of language proficiency, distinguishing between basic and extended language cognition. While ELC is typically more variable and associated with educational background, BLC, particularly in the lexical domain, is shared across speakers regardless of language dominance. Our results suggest that receptive vocabulary, as captured by LexTALE-Esp, constitutes a component of HLLs’ linguistic repertoire and may serve as a reliable proxy for broader proficiency—writing functional proficiency in the case of the present study.

Separating oral (naturalistic) and literate (schooled) language dimensions enables a more equitable and explanatory approach to studying both native and non-native speakers. Hulstijn (2024) redefines ELC as control of the written standard language taught in school and suggests that BLC is typically attained through massive early exposure to oral language. This distinction is particularly salient for HLLs, whose language experience often includes high levels of BLC but inconsistent access to ELC due to limited formal schooling in the heritage language.

Although our findings are theoretically consistent with aspects of BLC theory, our experiment was not designed to directly test or falsify the theory. Evaluating the full set of BLC predictions—such as the developmental trajectories of BLC and ELC or their neurocognitive underpinnings—remains beyond the scope of this study. Nevertheless, our results lend empirical support to the claim that lexical knowledge, as a core component of BLC, can meaningfully relate to functional writing abilities associated with ELC when including low-frequency lexical items such as in the case of LexTALE tests.

This understanding of the relationship between vocabulary and proficiency challenges the long-standing assumption that HLLs require entirely distinct assessment tools from L2 learners (Fairclough, 2012; Valdés, 1995). While heritage language learners often exhibit uneven development across modalities, the effectiveness of a vocabulary-based test in predicting writing performance suggests that certain tools designed for L2 populations may, with appropriate validation, be repurposed for HLLs. Indeed, Hulstijn (2010, 2011) argues that vocabulary knowledge—because it reflects explicit, decontextualized linguistic knowledge—may serve as a shared core indicator across populations. Our data lend empirical support to this view, particularly given that vocabulary scores explained more variance in writing proficiency than self-assessments, which are notoriously unreliable in HLL populations due to affective factors, educational experiences, and familiarity with language ideologies (Fairclough, 2012).

Still, vocabulary alone does not encompass the full range of language competence. LexTALE-Esp, like other receptive measures, captures breadth more than depth of vocabulary knowledge, and may underrepresent pragmatic and discourse-level abilities central to functional writing. The ability to produce coherent, grammatically accurate extended texts requires control of morphosyntax, textual cohesion, and genre-specific conventions—skills not directly tapped by lexical decision tasks. Yet the significant correlation between LexTALE-Esp and functional writing proficiency underscores that lexical access remains foundational: without sufficient vocabulary, advanced production is unlikely.

In theoretical terms, our findings call for a shift away from treating HLL proficiency as categorically different from L2 proficiency, and instead encourage more nuanced, multidimensional models grounded in actual language behavior. By showing that vocabulary knowledge serves as a meaningful predictor of functional writing ability, we contribute to a growing body of research that situates HLLs not as an outlier group, but as part of the broader continuum of bilingual development.

7.4. Practical Implications for Heritage Language Research and Pedagogy

Our findings have important implications for researchers studying heritage language populations. The LexTALE-Esp offers a quick alternative to more time-intensive proficiency assessments, making it particularly valuable for studies with large sample sizes or multiple testing sessions. However, researchers should use this measure with careful consideration of its limitations. While LexTALE-Esp shows correlations with writing proficiency across the sample, the overlap in scores across adjacent proficiency levels suggests caution when using it to separate participants into distinct proficiency groups. As Fairclough (2012) argues, assessments for HLLs must consider both what learners can do and where their gaps lie. Our study suggests that vocabulary-based tools like LexTALE-Esp may offer a valid starting point—particularly when used alongside other measures capturing productive language use. In practical terms, such tools are efficient, scalable, and capable of distinguishing among proficiency levels in large, heterogeneous populations.

While the scatterplot in Figure 2 might suggest that scores at 65% on LexTALE-Esp tend to align with Intermediate-Low or higher proficiency ratings on the WPT, we caution that these patterns are based on visual inspection and have not been statistically validated through cut-point analysis. For instance, participants with scores around 65% received WPT ratings spanning four sublevels—Intermediate-Low, Intermediate-Mid, Intermediate-High, and Advanced-Low (see Figure 2). While grouping individuals who differ by one sublevel might be acceptable depending on the research goal, differences of two or more sublevels represent meaningful disparities in functional language ability that LexTALE-Esp alone cannot capture. Researchers are therefore advised to use LexTALE-Esp in combination with other proficiency measures when finer-grained distinctions are required.

The efficacy of LexTALE-Esp with our predominantly Dominican, Mexican, and Ecuadorian heritage population also suggests its potential utility with heritage speakers from various Spanish-speaking backgrounds. However, researchers working with heritage speakers from other dialectal regions should consider potential variations in item familiarity based on regional vocabulary differences.

Also, findings on proficiency levels by course underscore the limitations of using course enrollment as a proxy for language proficiency in heritage language research. In our case, students were placed into courses based on an in-house placement system developed for administrative purposes, which has not undergone independent validation. As shown in Figure 1, students enrolled in the same course exhibited wide variability in both vocabulary knowledge and functional writing proficiency. We therefore caution researchers against relying on course level as a stand-in for proficiency unless the placement mechanism has been rigorously validated against external benchmarks.

The relationship between vocabulary knowledge and writing proficiency also has implications for instructional approaches. The finding that vocabulary recognition correlates strongly with functional writing ability suggests that vocabulary enrichment might be a particularly effective focus for heritage language instruction, especially for learners seeking to develop academic literacy skills. Instructors might use LexTALE-Esp scores to identify learners who would benefit from targeted vocabulary interventions and to track the effectiveness of such interventions over time.

7.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the current study suggest directions for future research. First, the distribution of participants across proficiency levels was uneven, with fewer participants at the Novice and higher Advanced levels. Future studies should aim to include more participants at these proficiency extremes to more fully evaluate LexTALE-Esp’s efficacy across the entire proficiency spectrum. That said, our sample reflects the actual distribution of heritage speakers enrolled at an urban public institution in New York City. While this may limit generalizability to other contexts, it offers strong ecological validity. We cannot artificially balance proficiency groups in a way that misrepresents the population we aim to serve—doing so would obscure the realities of the heritage learner landscape in similar educational settings.

Moreover, our study focused exclusively on the relationship between LexTALE-Esp and writing proficiency. Future research should examine how LexTALE-Esp scores correlate with other language skills, particularly speaking proficiency, given that oral language typically develops earlier and more robustly in heritage speakers. This would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how vocabulary knowledge relates to different aspects of heritage language competence. Moreover, other researchers could explore validating LexTALE versions in other languages using ACTFL-aligned tests, which are now available across multiple languages. A shared proficiency framework would enable more systematic cross-linguistic comparisons.

Finally, our results suggest that LexTALE-Esp captures meaningful distinctions between lower and higher proficiency bands—especially around the intermediate-mid threshold—but may be less sensitive for differentiating finer sublevels. Future studies should investigate the sensitivity of the test to developmental changes over time. Longitudinal designs that track both LexTALE-Esp scores and functional proficiency measures would help determine whether vocabulary tests can effectively capture language development in heritage speakers engaged in formal language study, as learners gain more experience with formal language instruction, potentially enhancing their metalinguistic awareness and ability to accurately self-assess.

8. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that LexTALE-Esp is a valid measure of proficiency for heritage speakers of Spanish, demonstrating stronger alignment with functional writing proficiency than self-assessment. These findings support the use of vocabulary-based assessments with heritage populations and contribute to our understanding of the relationship between lexical knowledge and functional language abilities in bilinguals with naturalistic acquisition patterns. Vocabulary knowledge, as assessed by LexTALE-Esp, offers a valuable—but partial—indicator of language proficiency. It is particularly helpful for broadly distinguishing learners around major proficiency levels but should be complemented by additional measures for finer diagnostic purposes (e.g., distinguishing between intermediate-high vs. advanced-low). As research on heritage languages continues to expand, the development and validation of appropriate assessment measures will be crucial for advancing our understanding of these unique bilingual populations. The LexTALE-Esp represents a promising tool in this endeavor, offering a practical and theoretically grounded approach to assessing Spanish heritage language proficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.-A. and A.G.; methodology, C.L.-A. and A.G.; formal analysis, C.L.-A.; investigation, C.L.-A.; data curation, C.L.-A.; writing—original draft preparation C.L.-A.; writing—review and editing, C.L.-A. and A.G.; visualization, C.L.-A.; project administration, C.L.-A. and A.G.; funding acquisition, C.L.-A. and A.G.; resources, C.L.-A.; supervision, C.L.-A. and A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Education, grant number P017A230023. Publication costs were supported by the Office for the Advancement of Research at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the CUNY Human Research Protection Program policies and procedures, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Graduate Center (protocol code 2024-0092-GC, 15 February 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be accessed at https://osf.io/x9bk4/.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Joseph V. Casillas for programming the LexTALE-Esp test and providing the scoring scripts that enabled our analyses. We also thank Syelle Graves for her administrative support throughout the project. Special thanks to Rocío Carranza Brito and Maria Julia Rossi for generously allowing us to collect data in their classes. Finally, we are deeply appreciative of all the students who participated in the study and made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HLL | Heritage language learner |

| WPT | Writing Proficiency Test |

| BLC | Basic language cognition |

| ELC | Extended language cognition |

| ACTFL | American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages |

Appendix A. Background Questionnaire

Tell us a bit about yourself:

- Your age:

- Your gender:(male, female, other, prefer not to respond)

- What’s the country of origin of each of your parents?(Mother _ Father _)

- What languages do your parents speak?(Mother _ Father _)

- If you were not born in the U.S., how old were you when you arrived in the U.S.? (Enter “0” if you were born in the U.S.)

- Have you attended school in a Spanish-speaking country or territory? (e.g., Puerto Rico, Mexico)(Yes/No)

- If yes, in what Spanish-speaking country or territory did you attend school?

- If yes, from what age to what age did you attend school in the Spanish-speaking country or territory?

- In general, which language do you prefer to use?(Span, Eng, both equally, it depends on who I talk to)

- Which statement best describes your writing ability in Spanish?(The four can-do statements that correspond to novice, intermediate, advanced, superior)

- I am able to produce most kinds of formal and informal correspondence, in-depth summaries, reports and research papers on a variety of social, academic, and professional topics. I can write about abstract issues with virtually no linguistic errors.

- I can write routine informal and some formal correspondence, as well as narratives, descriptions, and summaries of a factual nature. I can narrate and describe using the major time frames of past, present and future. I can elaborate to provide clarity.

- I have the ability to meet practical writing needs (i.e., I can write simple messages and letters, requests for information, and notes). I can ask and respond to simple questions in writing. I am able to communicate simple facts and ideas in a series of connected sentences on topics of personal interest.

- I am able to write words and phrases. I can write lists and short notes. I can fill in information on simple forms and documents.

- How often do you use each language in each situation? (possible answers: never, rarely, sometimes, often, always)

- Spanish at home

- English at home

- Spanish at work

- Spanish in school

- English in school

- Spanish with friends

- English with friends

Notes

| 1 | We distinguish between heritage speakers (who acquire Spanish in naturalistic environments) and learners (who enroll in courses to study their heritage language). Our study focused on Spanish heritage learners. While we believe our findings likely extend to heritage speakers in general, we want to acknowledge this theoretical distinction. |

| 2 | The ACTFL major proficiency levels—Novice, Intermediate, Advanced, Superior, and Distinguished—represent a progression from basic communication using learned phrases to highly sophisticated, abstract, and nuanced expression across a range of contexts. Distinguished level is not included in ratings for regular educational or research purposes. |

References

- ACTFL. (2024). ACTFL proficiency guidelines 2024. Available online: https://www.actfl.org/uploads/files/general/Resources-Publications/ACTFL_Proficiency_Guidelines_2024.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Alzahrani, A. (2023). LexArabic: A receptive vocabulary size test to estimate Arabic proficiency. Behavior Research Methods, 56(6), 5529–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, S., Badan, L., & Brysbaert, M. (2021). LexITA: A quick and reliable assessment tool for Italian L2 receptive vocabulary size. Applied Linguistics, 42(2), 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, E., Montrul, S., & Polinsky, M. (2013). Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics, 39(3–4), 129–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M. (2013). Lextale_FR a fast, free, and efficient test to measure language proficiency in French. Psychologica Belgica, 53(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, M., & Kagan, O. (2011). The results of the national heritage language survey: Implications for teaching, curriculum design, and professional development. Foreign Language Annals, 44(1), 40–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, R., Aguirre-Muñoz, Z., Spivey, M., & Bortfeld, H. (2024). Spanish–English bilingual heritage speakers processing of inanimate sentences. Frontiers in Language Sciences, 3, 1370569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, I. L., & Chang, C. (2018). LEXTALE_CH: A quick, character-based proficiency test for mandarin Chinese. In Proceedings of the annual boston university conference on language development. Cascadilla Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cuetos, F., González-Nosti, M., Barbón, A., & Brysbaert, M. (2012). SUBTLEX-ESP: Spanish word frequencies based on film subtitles. Psicológica, 32(2), 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, M. (2011). Testing the lexical recognition task with Spanish/English bilinguals in the United States. Language Testing, 28(2), 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, M. (2012). A working model for assessing Spanish heritage language learners’ language proficiency through a placement exam. Heritage Language Journal, 9(1), 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, P., & Brysbaert, M. (2017). Can Lextale-Esp discriminate between groups of highly proficient Catalan–Spanish bilinguals with different language dominances? Behavior Research Methods, 49(2), 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, J. J., & Casillas, J. V. (2024, February 26–27). Examining the LexTALE as a reliable measure of language proficiency [Conference presentation]. 14th SLISE–SLINKI Conference, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, A., & Graves, S. (2020). Are heritage speakers of Spanish significantly better at speaking than at writing? Results of an experiment on writing and speaking proficiencies—Actual and perceived. Foreign Language Annals, 53(4), 920–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, A., & O’Neill, T. (2017). Who are heritage writers? Language experiences and writing proficiency. Foreign Language Annals, 50(4), 734–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, A., & O’Neill, T. (2018). Writing proficiency profiles of heritage learners of Chinese, Korean, and Spanish. Foreign Language Annals, 51(4), 719–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Pino, B. G., & Pino, F. (2005). Issues in articulation for heritage language speakers. Hispania, 88(1), 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstijn, J. (2010). Chapter 9. Measuring second language proficiency. In E. Blom, & S. Unsworth (Eds.), Language learning & language teaching (Vol. 27, pp. 185–200). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstijn, J. (2011). Language proficiency in native and nonnative speakers: An agenda for research and suggestions for second-language assessment. Language Assessment Quarterly, 8(3), 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstijn, J. (2015). Language proficiency in native and non-native speakers: Theory and research (Vol. 41). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstijn, J. (2024). Predictions of individual differences in the acquisition of native and non-native languages: An update of BLC theory. Languages, 9(5), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, G. N. (2012). Hindi heritage language learners’ performance during OPIs: Characteristics and pedagogical implications. Heritage Language Journal, 9(2), 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izura, C., Cuetos, F., & Brysbaert, M. (2014). Lextale-Esp: A test to rapidly and efficiently assess the Spanish vocabulary size. Psicológica, 35(1), 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, L., & Llosa, L. (2007). Heritage language reading in the university: A survey of students’ experiences, strategies, and preferences. Heritage Language Journal, 5(1), 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, O., & Friedman, D. (2003). Using the OPI to place heritage speakers of Russian. Foreign Language Annals, 36(4), 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, T., Arona, S., Besler, A., Cruschina, S., Ferin, M., Gyllstad, H., & Venagli, I. (2023). LexSIC: A quick vocabulary test for dialect proficiency in Sicilian. Isogloss. Open Journal of Romance Linguistics, 9(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. T., Van Heuven, W. J. B., Price, J. M., & Leong, C. X. R. (2023). LexMAL: A quick and reliable lexical test for Malay speakers. Behavior Research Methods, 56(5), 4563–4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemhöfer, K., & Broersma, M. (2012). Introducing LexTALE: A quick and valid lexical test for advanced learners of English. Behavior Research Methods, 44(2), 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W., & Winke, P. (2019). Self-assessment: How reliable is it in assessing oral proficiency over time? Foreign Language Annals, 52(1), 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C., Swender, E., & Rivera-Martinez, M. (2013). Assessing the oral proficiency of heritage speakers according to the ACTFL proficiency guidelines 2012—Speaking. Heritage Language Journal, 10(2), 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L. (2009). Understanding second language acquisition. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Ortín, R. (2024). Spanish heritage speakers’ processing of lexical stress. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 62(2), 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. I., Solon, M., Dehghan-Chaleshtori, M., & Ghanbar, H. (2022). Proficiency reporting practices in research on second language acquisition: Have we made any progress? Language Learning, 72(1), 198–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (2006). Incomplete Acquisition: American Russian. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 14(2), 191–262. [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Mayenco, E., Chaouch-Orozco, A., Liu, H., & Martín-Villena, F. (2023). The LexTALE as a measure of L2 global proficiency: A cautionary tale based on a partial replication of Lemhöfer and Broersma (2012). Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 13(3), 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S., Teng, M. F., & Fu, A. (2024). LexCH: A quick and reliable receptive vocabulary size test for Chinese Learners. Applied Linguistics Review, 15(2), 643–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmela, R., Lehtonen, M., Garusi, S., & Bertram, R. (2021). Lexize: A test to quickly assess vocabulary knowledge in Finnish. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62(6), 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanley, A., Keller, M., Alexiadou, A., & Wiese, H. (2025). Linguistic dynamics in heritage speakers: Insights from the RUEG group. Language Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swender, E., Martin, C. L., Rivera-Martinez, M., & Kagan, O. E. (2014). Exploring oral proficiency profiles of heritage speakers of russian and Spanish. Foreign Language Annals, 47(3), 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigchelaar, M., Bowles, R. P., Winke, P., & Gass, S. (2017). Assessing the validity of ACTFL Can-Do Statements for spoken proficiency: A rasch analysis. Foreign Language Annals, 50(3), 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoschuk, B., Ferreira, V. S., & Gollan, T. H. (2019). When a seven is not a seven: Self-ratings of bilingual language proficiency differ between and within language populations. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 22(3), 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treffers-Daller, J. (2025). BLC and subordination in heritage speakers—Towards a new research agenda: Commentary on Hulstijn (2024). Languages, 10(5), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, G. (1995). The Teaching of minority languages as academic subjects: Pedagogical and theoretical challenges. The Modern Language Journal, 79(3), 299–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, G. (2005). Bilingualism, heritage language learners, and SLA research: Opportunities lost or seized? The Modern Language Journal, 89(3), 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]