Abstract

This study investigates the cognitive processing of Spanish idioms from a pragmatic perspective, with the goal of examining the idiom superiority effect. An eye-tracking experiment was conducted with 77 participants to assess how idiomaticity influences processing and whether heritage speakers align more with L1 or L2 patterns. Results show a processing advantage for idioms among L1 speakers, suggesting reduced cognitive load in later stages. Both heritage and L2 speakers showed longer reading times, but only L2 speakers benefited consistently from idiomaticity. Heritage speakers processed idioms more slowly, indicating difficulty with opacity despite early exposure. Findings support hybrid models of idiom processing and highlight the unique strategies of heritage speakers shaped by dual input sources.

1. Introduction

This study addresses two key questions regarding idioms: how they are interpreted and integrated into discourse assumptions, and how their processing varies depending on the speaker’s linguistic profile (L1, L2, and heritage speakers). In contrast to psycholinguistic approaches that remain more detached from communicative concerns, we aim to revisit idiom processing from a clearly pragmatic perspective, which views human communication and cognition as guided by the search for relevance (Sperber & Wilson, 1995). Regarding the different speaker profiles, defined either by learning processes (L2 speakers) or by a combination of acquisition and learning (heritage speakers), we examine whether all speakers rely on similar cognitive mechanisms to maximize the relevance of an utterance containing idioms and to construct a hypothesis about its intended meaning.

To answer both of these questions, we formulated research questions concerning the comprehension of idiomatic and non-idiomatic multiword units, tested through an experimental eye-tracking study on Spanish.

1.1. Idioms and Their Processing

Idioms exist along a compositional continuum that encompasses expressions differing in the degree to which their meaning can be derived from the individual processing of their components (Wray, 2002; Burger et al., 2007). A non-idiomatic unit such as lista secreta (“secret list”) (1) is interpreted through the syntactic and lexical relations established among its elements, yielding a meaning like “a written record of confidential character.” In contrast, the interpretation of a unified expression like lista negra (“blacklist”) (2) relies on retrieving an idiomatic meaning: “a list of individuals or entities considered dangerous or undesirable.”

Context: Ana y Pedro tienen un bar con karaoke en Madrid. A menudo la gente se emborracha y causa problemas. En el bar hay muchas peleas entre los clientes. Ana y Pedro han tomado nota de todo lo sucedido y han decidido limitar estrictamente la entrada de personas al bar.

(“Ana and Pedro run a karaoke bar in Madrid. People often get drunk and cause trouble. There are frequent fights among customers. Ana and Pedro have taken note of all incidents and have decided to strictly limit who is allowed to enter the bar.”)

(1) Ana y Pedro tienen una lista secreta. No dejan entrar a ninguna persona que haya causado problemas anteriormente.

(“Ana and Pedro have a secret list. They do not allow entry to anyone who has previously caused trouble.”)

(2) Ana y Pedro tienen una lista negra. No dejan entrar a ninguna persona que haya causado problemas anteriormente.

(“Ana and Pedro have a blacklist. They do not allow entry to anyone who has previously caused trouble.”)

In general, idiomatic processing has been explained through binary models that posit distinct retrieval patterns depending on whether the expression is idiomatic or non-idiomatic. Different models propose that idiomatic processing occurs either prior to, in parallel with, or after non-idiomatic processing (Lackner & Garrett, 1972; Foss & Jenkins, 1973; Swinney, 1976; Swinney & Cutler, 1979; Gibbs, 1980). These models converge on the prediction of an inherent superiority of idiomaticity, the idiom superiority effect, which is grounded in the idea that idioms require fewer computational operations due to the arbitrariness of their meaning in relation to the meanings of their individual components (Ortony et al., 1978; Swinney & Cutler, 1979; Gibbs, 1980; Gibbs & Gonzales, 1985; McGlone et al., 1994; Gibbs & Colston, 2007).

The hypothesis of an inherent superiority of idiomatic expressions has taken on more flexible forms. The ease of idiom processing appears to depend on several properties of the expression, which influence the relative cognitive cost of processing idiomatic versus non-idiomatic units (Cacciari & Glucksberg, 1991). Four properties have received particular attention (Multidetermined Model, Libben & Titone, 2008):

- Literalness, or the extent to which an idiom allows for an alternative literal interpretation;

- Transparency, or the degree to which the idiom’s meaning can be predicted from the meanings of its individual components;

- Familiarity, or the availability of the expression in the mental lexicon; and

- Frequency of use.

Theoretical arguments have been supported by various types of experimental studies. Overall, idioms have been shown to offer systematic processing advantages for L1 speakers (Ortony et al., 1978; Swinney & Cutler, 1979; Gibbs, 1980; Conklin & Schmitt, 2008; Carrol, 2021). The idiom superiority effect has been demonstrated by faster response times in lexical decision tasks (Ortony et al., 1978; Swinney & Cutler, 1979; Tabossi et al., 2009; Rommers et al., 2013; Carrol & Conklin, 2014), shorter total reading times in self-paced reading tasks (Gibbs, 1980; Conklin & Schmitt, 2008; Libben & Titone, 2008; Tremblay et al., 2011; Colombo, 2014), shorter total reading times, fewer regressions, and a higher tendency to skip the final words of idioms in eye-tracking experiments (Underwood et al., 2004; Siyanova-Chanturia et al., 2011; Carrol & Conklin, 2017, 2020). Eye-tracking data also show that figurative meanings are accessed faster when idioms are familiar, suggesting direct retrieval guided by context. Furthermore, idiomatic expressions are produced with fewer pauses and shorter durations for keywords.

The models above focus on idiom processing that is based on linguistic properties, contrasting idiomatic and non-idiomatic meanings. This study instead adopts a pragmatic approach based on Relevance Theory (Sperber & Wilson, 1995; Wilson & Carston, 2007), which posits that interpreting both types of expressions involves early inferential processes aimed at maximizing cognitive effects while minimizing effort. Rather than retrieving fixed meanings, speakers construct ad hoc concepts through contextual cues and communicative intent (Carston, 2012, 2016; Wilson, 2011, 2016; Vega-Moreno, 2001, 2003). The lexicon provides schematic guidance, and meaning is pragmatically reconstructed in real time (Escandell-Vidal, 2020). This inferential route is not necessarily more effortful than literal decoding. Contextual and discourse factors are crucial in guiding idiom interpretation and ensuring felicitous use (Beck & Weber, 2021; Noveck et al., 2023). Compared to models that propose distinct mechanisms for idiomatic and literal processing, Relevance Theory offers a unified inferential framework applicable to both. While its empirical predictions may overlap with those of other models, its explanatory advantage lies in accounting for variability in idiom processing across speaker profiles, familiarity levels, and discourse contexts, without positing separate representational systems or processing modules. In this sense, Relevance Theory allows for a cognitively economical explanation of how idiomatic meaning is integrated into utterance interpretation under varying processing conditions, assuming optimal relevance conditions, thus, highly idiomatic units are not expected to incur greater processing costs than non-idiomatic ones (research question 1).

1.2. The Processing of Idiomaticity and the Different Speaker Profiles

Most research on the processing of idiomaticity has been conducted with L1 speakers and primarily in relation to English. Understanding how heritage and L2 speakers process idioms is a crucial component of any theory of language, as it is reasonable to expect that these speaker profiles influence the way linguistic units are processed (Vanlancker-Sidtis, 2003; Underwood et al., 2004; Jiang & Nekrasova, 2007; Conklin & Schmitt, 2008; Siyanova-Chanturia et al., 2011; Carrol & Conklin, 2014, 2017; Beck & Weber, 2016; Cucchiarini et al., 2022; Cieślicka et al., 2021; Gridneva et al., 2023).

L2 and heritage speakers represent distinct profiles based on language acquisition order and linguistic environment (Fairclough & Loureda Lamas, 2025). In the present study, L2 speakers learn the language later and usually live in homoglossic contexts, where their L1 and majority language coincide. The heritage speakers acquire the language early but in heteroglossic settings, where their first language differs from the societal majority language (Moreno Fernández, 2024).

While L1 speakers generally process idioms more efficiently, L2 speakers, particularly those not yet at advanced proficiency, show greater variability and require more reading time with figurative or less transparent expressions (Siyanova-Chanturia et al., 2011; Gridneva et al., 2023). This processing advantage observed in L1 speakers can be further explained by Hulstijn’s (2019) Basic Language Cognition framework, which posits that highly frequent and conventionalized units belong to a shared lexical and grammatical repertoire that L1 speakers acquire naturally through oral exposure.

Eye-tracking studies reveal that L2 speakers rely more on inferential processes than direct lexical retrieval, leading to increased cognitive effort when constructing meaning in context. This highlights how idiom processing fluency depends on both linguistic competence and the ability to integrate contextual assumptions (Siyanova-Chanturia et al., 2011; Matlock & Heredia, 2002; Cieslicka, 2006). A further explanation lies in L2 speakers’ still-developing form-meaning mappings (VanPatten, 2004), which leads them to process lexical items individually rather than as holistic idiomatic units. Unlike L1 speakers, whose idiom processing is more automatized and implicit (Ellis, 2009), L2 users rely more on conscious, metapragmatic strategies, especially in early learning stages (Taguchi, 2008; DeKeyser, 1997; Clahsen & Felser, 2006). Automatization improves with proficiency and is associated with greater cognitive efficiency (Segalowitz & Hulstijn, 2005; Segalowitz, 2010). Additionally, the parasitic hypothesis (Hall, 2002) suggests that L2 speakers may activate L1 equivalents when encountering idioms, rather than processing them directly as unified expressions.

Another relevant question is whether L2 and heritage speakers differ in how they process idiomatic and non-idiomatic structures. Montrul (2006) and Montrul and Rodríguez Louro (2008) indicated that heritage speakers have an advantage over L2 speakers in certain syntactic and pragmatic domains, such as subject–verb agreement, the pragmatic use of null and overt pronouns, and greater flexibility in subject-verb word order. These studies suggest that, when controlling for proficiency level, significant differences between heritage and L2 speakers emerge in specific components of the grammatical system, though not necessarily across the board (Lynch, 2009).

Due to their early yet often inconsistent exposure to the language, heritage speakers develop a strategic but highly variable command of idiomaticity. This is shaped by factors such as cross-linguistic structural similarity, bilingual proficiency, age of acquisition, and degree of exposure to the heritage language (R. W. Langacker, 1987; Montrul, 2015; Polinsky, 2018). Studies have shown that heritage speakers tend to prefer semantically transparent, non-idiomatic forms and avoid highly opaque constructions (Boumans, 2006; Brehmer & Czachór, 2012; Polinsky, 2018), likely due to heuristic processing strategies that prioritize regularity and predictability. Given this profile, it is essential to investigate how heritage speakers handle idiomatic and opaque expressions in comparison to L1 and L2 speakers. Based on these factors, both heritage and L2 speakers are expected to require more processing effort than L1 speakers when dealing with idiomatic and non-idiomatic expressions (research question 2).

Additionally, given their preference for analytic and non-idiomatic constructions, heritage speakers are expected to experience greater processing difficulty than L2 speakers when confronted with familiar but opaque idiomatic expressions (research question 3). This prediction is supported by studies examining idiom processing across speaker profiles. For instance, in a self-paced reading study, Gridneva et al. (2023) found that both heritage and L2 speakers of Russian required significantly more time than L1 speakers to process idioms, regardless of their degree of English equivalence. These findings suggest that heritage speakers, like L2 speakers, rely on their dominant language while interpreting idioms, especially when idioms are familiar but semantically opaque. This reliance underscores the role of familiarity in idiom processing (Titone & Libben, 2014; Cronk & Schweigert, 1992).

2. Methodology

To answer research questions 1–3, an eye-tracking experiment comparing heritage, L1, and L2 speakers of Spanish during the reading of idioms and non-idioms was designed. The experiment approaches two factors: (1) the speaker group (heritage, L1, and L2 speakers) as a subject variable, and (2) idioms as the object variable. The object variable distinguishes between expressions that exhibit idiomatic strength and others that allow a more transparent, non-idiomatic interpretation. Since idioms display varying degrees of lexical fixedness and semantic opacity, this study investigates how different speaker groups approach their retrieval and comprehension.

2.1. Materials, Preliminary Validation Test, and Areas of Interest

Idioms were selected based on multiple criteria: (a) all expressions in Spanish have a direct idiomatic counterpart in English, the other language involved in the learning or acquisition context; (b) they are commonly used in Spanish language classrooms, confirmed through a questionnaire administered to Spanish instructors; and (c) they were pretested with a group of L1 Spanish speakers to select an unambiguous set of items. Special attention was given to controlling for degrees of idiomaticity: only expressions that were consistently rated as highly idiomatic (for idiom items) or fully compositional (for control items) were included, minimizing overlap along the idiomaticity continuum. In all idiomatic units, the structure consisted of two lexical elements: a noun and an adjective. The noun always preserved its literal meaning, while the adjective determined the idiomatic status of the expression, introducing a non-compositional reading for idiomatic items. Thus, the shift in meaning occurred at the level of the adjectival modifier, which triggered the idiomatic interpretation of the full phrase. The resulting six target expressions included both idiomatic and non-idioms alternatives. After the eye-tracking task, all participants completed a post-test assessing comprehension of the idiomatic units, confirming that the intended meaning was also accessible to all speaker groups.

To capture processing differences, eye-tracking data from four predefined areas of interest (AOI) were collected during a reading task (Holmqvist et al., 2011, p. 187):

- Full utterance: The full utterance, including the target expression (idiom/non-idiom). Example: Juan y Ana tienen una lista negra/lista secreta;

- Target expression: The word combination that functions as either an idiomatic unit or a non-idiomatic expression. Example: lista negra/lista secreta;

- Key lexical element: The component of the target expression that triggers idiomatic recognition. Example: lista;

- Complementary lexical element: The second lexical component that, together with the first element, forms the idiomatic or non-idiomatic unit. Example: negra/secreta.

By evaluating reading behavior across these areas, the study investigates how quickly idiomatic meaning is accessed and whether different speaker groups experience difficulties for idioms interpretation within the previously provided context.

2.2. Experimental Design and Measures

This study follows a 2 (idiomaticity: idiom vs. non-idiom) × 3 (speaker group: L1, L2, heritage speakers) mixed factorial design, with idiomaticity as a within-subjects variable and speaker group as a between-subjects variable.

A Latin square design was applied to control for potential confounding variables, such as word frequency and phrase length (Rayner, 2009). The experimental lists maintained a 1:2 ratio of target to filler sentences, with stimuli presented in a pseudo-randomized order (Arunachalam, 2013).

Three primary measures were examined:

- Total reading time (TRT): The cumulative fixation duration across all reading passes on the critical unit, representing overall processing effort.

- First-pass reading time (FRT): The duration of the initial encounter with the critical unit, reflecting the formation of an initial assumption.

- Re-reading time (RRT): The cumulative time spent revisiting the critical AOI after the first pass reading time, reflecting subsequent verification or revision of the initial assumption.

2.3. Participants

The study included 77 participants divided into three Spanish-speaking groups: 32 L1 speakers of Spanish, 25 learners of Spanish as a second language (L2), and 20 heritage speakers. The experiment was conducted at Nebrija University (Spain) in December 2024.

- The L1 speaker group consisted of 32 university students aged 18–25, with a gender distribution of 62% women and 38% men. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

- The L2 group included 25 university students in the same age range. All participants were from the United States and reported no Hispanic background. The gender distribution was 58% women and 42% men. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Their first language was English, and they held an officially certified B2 level in Spanish. At the time of the study, they were enrolled in C1-level Spanish courses. Although the participants were tested during a temporary academic stay of three months at Universidad Nebrija, all L2 speakers were permanent residents of the United States. Consequently, their linguistic background reflects the typical acquisition context for L2 learners in the United States, characterized by limited long-term immersion in natural Spanish-speaking environments and primarily classroom-based instruction.

- The heritage speaker group consisted of 20 participants born in the United States in the same age range, with 65% women and 35% men. Nearly 90% reported having two Hispanic parents, and 10% had only one parent of Hispanic origin. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Their first language was English, and they were enrolled in a C2-level Spanish course specifically designed for this speaker profile at the time of the study. All participants permanently resided in the United States and were temporarily enrolled in a three-month academic program at Universidad Nebrija. As a result, their exposure to Spanish reflects the typical linguistic environment of U.S.-based heritage speakers, who generally have not experienced long-term immersion in Spanish-speaking societies beyond this limited academic stay. Early exposure to Spanish was verified through a pre-screening questionnaire, which included information on home language use during childhood, the language spoken by parents, the age at which Spanish exposure began, and current usage patterns. All heritage speakers reported exposure to Spanish from birth or early childhood, with regular home use. In terms of current usage, the group was highly homogeneous: 93% reported actively using Spanish in academic or family contexts.

2.4. Apparatus and Procedure

The study employed an EyeLink 1000 Plus system by SR Research, manufactured in Ottawa, Canada, to record eye movements at 2000 Hz, with an accuracy of <0.15°. Stimuli were presented via the Experiment Builder software (version 2.6.11), and data collection spanned one week.

Participants read silently at their own pace, with the task duration not exceeding 10 min per person. Stimuli were displayed on a monitor, with chin rests used to minimize head movement. Participants were given task instructions and provided informed consent before the experiment. Calibration was conducted before and during the experiment to maintain measurement precision. Each participant completed a total of 13 stimulus blocks: 6 blocks containing discourse contexts, fillers and critical items related to the present study, 6 blocks from an unrelated experiment on encapsulation mechanisms in counter argumentative structures (not reported here), and 1 initial practice block. Post-experiment data cleaning and exportation were performed using the Data Viewer software (version 4.4.1).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To ensure robust data quality, extreme values were removed if the following criteria were met in the area corresponding to the full utterance (Pickering et al., 2000; Reichle et al., 2003):

- Track loss: First-pass reading time in the area of the full utterance = 0 ms.

- Fast reading observations: First-pass reading time in the area of the full utterance < 80 ms and second-pass reading time in AOI_1 < 80 ms.

- Slow reading observations: Total reading time in the area of the full utterance > 800 ms.

After exclusions, data from one participant were removed, leading to a final dataset of 463 observations, with one (0.2%) of all observations affected. Additive mixed models (Fahrmeir et al., 2013; Wood, 2017) were computed in R (version 4.3.2) (R Core Team, 2018) using the mgcv package (version 1.9-0). Two models were applied: The first model type, namely additive mixed models, contains all experimental conditions and their interaction with all AOI as independent variables. The dependent variable is set to be the reading time per word, modeling the three different reading times in separate models. Further, this type of model incorporates a nonlinear effect for flexible estimations of potential word length effects. Random effects (Diggle et al., 2002) were included to account for participant and item variability.

The primary model was used to obtain predictions for a fixed average character count per word, enabling investigation of variations in reading time in milliseconds and their interpretation in terms of predicted absolute and relative differences between conditions. The obtained percentage differences between conditions, alongside their respective standard errors, formed the primary descriptive basis for evaluating processing effort. According to Loureda et al. (2021), these effects were categorized as irrelevant (<±4%), medium (±4–10%), or large (>±10%).

The second type of model, namely linear mixed models, while containing the same random effects, estimates the associations between the experimental conditions on a letter level. Separate models are estimated for each AOI considered in this study. The reported p-values in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 in Section 3 are based on the computed marginal effects for the second model type, using a significance level of 0.05 to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Processing of Idioms and Non-Idioms in L1 Speakers

Isolating L1 speakers processing behavior allows for assessing the relative distance of L2 and heritage speakers from this baseline. Among L1 speakers, faster reading times were observed for the idiomatic unit, both when analyzed as a whole and when examining its individual components. However, the effects, ranging between −5.12% and +2.7%, do not reach statistical significance (cf. Table 1).

The total reading time of the utterance indicates whether difficulties arise in integrating an idiomatic expression into discourse processing. The data show no substantial or significant differences in idiomatic versus non-idiomatic expressions (differences below ±3%). The findings indicate that, under optimal relevance conditions, idiomaticity does not hinder processing in L1 speakers. Familiar idioms embedded in coherent contexts can be accessed efficiently through direct retrieval, requiring minimal inferential effort.

Table 1.

TRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1 speakers with percentage difference and p-values.

Table 1.

TRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1 speakers with percentage difference and p-values.

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-idiom | 288.00 (SE: 26.99) | 291.78 (SE: 26.79) | 320.02 (SE: 27.28) | 271.16 (SE: 26.99) |

| Idiom | 295.77 (SE: 27.19) | 280.91 (SE: 27.06) | 306.10 (SE: 27.32) | 257.28 (SE: 26.96) |

| Percentage difference | 2.70% | −3.73% | −4.35% | −5.12% |

| p-value | 0.565 | 0.643 | 0.360 | 0.940 |

During the first reading, readers perform tasks that lead to the recovery of an initial assumption, in which the decoded linguistic material is contextually enriched to the point that it can activate an inferential route (Rayner, 1998, p. 376). The reading times recorded during this first pass suggest that each component of the idiomatic units is processed more quickly than in comparable non-idiomatic units. However, these effects, ranging from −3.52% to −4.18%, do not reach significance in the mixed-effects models. No notable effects are observed for the expressions as a whole or for the complete utterance. In sum, no difficulties are observed in either local or discourse-level processing of idioms during the construction of an initial assumption (cf. Table 2).

Table 2.

FRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1 speakers with percentage difference and p-values.

Table 2.

FRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1 speakers with percentage difference and p-values.

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Comp. Lex. Element | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-idiom | 255.03 (SE: 19.82) | 210.76 (SE: 19.67) | 239.19 (SE: 20.07) | 223.85 (SE: 20.02) |

| Idiom | 253.92 (SE: 20.01) | 213.80 (SE: 19.89) | 229.19 (SE: 20.11) | 215.97 (SE: 19.81) |

| Percentage difference | −0.44% | 1.44% | −4.18% | −3.52% |

| p-value | 0.974 | 0.652 | 0.522 | 0.970 |

Finally, readers use re-reading time to reconsider the initial assumption in light of the available information, to confirm, revise, or discard it and thereby achieve relevant cognitive effects (Carrol & Conklin, 2014, p. 6). This measure reveals a lower degree of reanalysis when idiomaticity is present: between 4.88% and 10.6% less re-reading time for the individual words, and 17.01% less for the full expressions. Although the mixed-effects models do not yield statistically significant results, the differences appear consistent enough to suggest that idioms undergo less reanalysis than literal expressions.

When examining reanalysis at the level of the entire utterance, however, idioms trigger more processing effort than non-idiomatic expressions—over 27% more re-reading time. These efforts, nevertheless, are relatively moderate, as they do not result in any penalties in the total reading time (cf. Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 3.

RRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1 speakers with percentage difference and p-values.

Table 3.

RRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1 speakers with percentage difference and p-values.

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-idiom | 31.11 (SE: 15.31) | 79.32 (SE: 15.29) | 80.61 (SE: 15.26) | 44.15 (SE: 15.36) |

| Idiom | 39.73 (SE: 15.37) | 65.83 (SE: 15.26) | 76.68 (SE: 15.27) | 39.47 (SE: 15.26) |

| Percentage difference | 27.71% | −17.01% | −4.88% | −10.6% |

| p-value | 0.409 | 0.314 | 0.482 | 0.912 |

3.2. Processing of Idioms and Non-Idioms in L1, L2, and Heritage Speakers

A second key issue is how heritage and L2 speakers process non-idiomatic and idiomatic expressions in comparison to L1 speakers. Both L2 and heritage speakers require more total reading time for idiomatic and non-idiomatic units alike. Idioms, as complete expressions, are processed by L2 speakers in 21.7% more time than by L1 speakers. For heritage speakers, processing takes 31.81% more time compared to L1 speakers. These values are highly relevant and statistically significant. In the processing of non-idiomatic expressions, both L2 and heritage speakers also exhibit additional effort, ranging from 22.46% to 27.08%, with significant effects observed for L2 speakers and large effects for heritage speakers.

The integration of the expressions into the broader discourse also demands greater effort from both heritage and L2 speakers. For idioms, processing effort exceeds that of L1 speakers by 14.83% to 17.63%; for non-idiomatic expressions, by 9.56% to 26.05%. These differences are statistically significant in most cases (cf. Table 4).

Table 4.

TRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1, L2, and heritage speakers (LH) with percentage difference and p-values, grouped by idiomaticity.

Table 4.

TRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1, L2, and heritage speakers (LH) with percentage difference and p-values, grouped by idiomaticity.

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-idiom | L1 | 288.00 (SE: 26.99) | 291.78 (SE: 26.79) | 320.02 (SE: 27.28) | 271.16 (SE: 26.99) |

| L2 | 315.53 (SE: 29.15) | 370.79 (SE: 28.96) | 398.89 (SE: 29.43) | 350.15 (SE: 29.09) | |

| % diff. | 9.56% | 27.08% | 24.65% | 29.13% | |

| p-value | 0.251 | 0.018 | 0.071 | 0.025 | |

| L1 | 288.00 (SE: 26.99) | 291.78 (SE: 26.79) | 320.02 (SE: 27.28) | 271.16 (SE: 26.99) | |

| LH | 363.02 (SE: 31.40) | 357.30 (SE: 31.21) | 383.25 (SE: 31.67) | 338.71 (SE: 31.30) | |

| % diff. | 26.05% | 22.46% | 19.76% | 24.91% | |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.103 | 0.277 | 0.187 | |

| Idiom | L1 | 295.77 (SE: 27.19) | 280.91 (SE: 27.06) | 306.10 (SE: 27.32) | 257.28 (SE: 26.96) |

| L2 | 339.64 (SE: 29.24) | 341.87 (SE: 29.13) | 361.93 (SE: 29.35) | 323.27 (SE: 29.05) | |

| % diff. | 14.83% | 21.7% | 18.24% | 25.65% | |

| p-value | 0.039 | 0.021 | 0.109 | 0.017 | |

| L1 | 295.77 (SE: 27.19) | 280.91 (SE: 27.06) | 306.10 (SE: 27.32) | 257.28 (SE: 26.96) | |

| LH | 347.92 (SE: 31.43) | 370.26 (SE: 31.33) | 406.72 (SE: 31.52) | 335.19 (SE: 31.26) | |

| % diff. | 17.63% | 31.81% | 32.87% | 30.28% | |

| p-value | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.004 |

It is also necessary to consider whether there are differences between the processing patterns of heritage and L2 speakers. Two indicators support the claim that heritage speakers handle idiomaticity with greater difficulty. The first one is the total reading time for the full target expression. Heritage speakers process idioms less efficiently, requiring 8.3% more time than L2 speakers. While these differences are not statistically significant, they are consistent within the model. In terms of integrating idioms in a global assumption into their surrounding context, no meaningful differences are observed between the two groups (<3%) (cf. Table 5).

Table 5.

TRT (ms) of idioms in L2, and heritage speakers (LH) with percentage difference and p-values.

Table 5.

TRT (ms) of idioms in L2, and heritage speakers (LH) with percentage difference and p-values.

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 | 339.64 (SE: 29.24) | 341.87 (SE: 29.13) | 361.93 (SE: 29.35) | 323.27 (SE: 29.05) |

| LH | 347.92 (SE: 31.43) | 370.26 (SE: 31.33) | 406.72 (SE: 31.52) | 335.19 (SE: 31.26) |

| Percentage difference | 2.44% | 8.3% | 12.38% | 3.69% |

| p-value | 0.642 | 0.272 | 0.240 | 0.540 |

The second relevant indicator is the total reading time for each condition (idioms vs. non-idioms) within the same speaker group. The data reveal that both L1 and L2 speakers show a facilitation effect when processing idioms compared to non-idiomatic units. This favorable effect is observed either in the overall processing of the expression (L2) or at least in the key lexical element (L1). This local facilitation effect, however, is not observed in heritage speakers, who display slight increases in processing effort in the key lexical element (6.12%). Nonetheless, these local processing efforts are compensated when integrating idioms into full utterances: for heritage speakers, processing utterances containing idioms takes 4.16% less time than processing those with non-idiomatic expressions. This pattern contrasts with that of L2 speakers, who show increased effort (7.64%) when integrating an idiom into an utterance. In sum, heritage speakers handle local differences between idiomatic and non-idiomatic expressions less efficiently, but they manage discourse-level integration of idioms more effectively than L2 speakers (cf. Table 6).

Table 6.

TRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1, L2, and heritage speakers (LH) with percentage difference and p-values, grouped by speaker group.

Table 6.

TRT (ms) of idioms and non-idioms in L1, L2, and heritage speakers (LH) with percentage difference and p-values, grouped by speaker group.

| Full Utterance | Target Expression | Key Lexical Element | Compl. Lex. Element | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Non-idiom | 288.00 (SE: 26.99) | 291.78 (SE: 26.79) | 320.02 (SE: 27.28) | 271.16 (SE: 26.99) |

| Idiom | 295.77 (SE: 27.19) | 280.91 (SE: 27.06) | 306.10 (SE: 27.32) | 257.28 (SE: 26.96) | |

| % diff. | 2.7% | −3.73% | −4.35% | −5.12% | |

| p-value | 0.565 | 0.643 | 0.360 | 0.940 | |

| L2 | Non-idiom | 315.53 (SE: 29.15) | 370.79 (SE: 28.96) | 398.89 (SE: 29.43) | 350.15 (SE: 29.09) |

| Idiom | 339.64 (SE: 29.24) | 341.87 (SE: 29.13) | 361.93 (SE: 29.35) | 323.27 (SE: 29.05) | |

| % diff. | 7.64% | −7.8% | −9.27% | −7.68% | |

| p-value | 0.061 | 0.614 | 0.296 | 0.933 | |

| LH | Non-idiom | 363.02 (SE: 31.40) | 357.30 (SE: 31.21) | 383.25 (SE: 31.67) | 338.71 (SE: 31.30) |

| Idiom | 347.92 (SE: 31.43) | 370.26 (SE: 31.33) | 406.72 (SE: 31.52) | 335.19 (SE: 31.26) | |

| % diff. | −4.16% | 3.63% | 6.12% | −1.04% | |

| p-value | 0.459 | 0.072 | 0.294 | 0.060 |

3.3. Overview

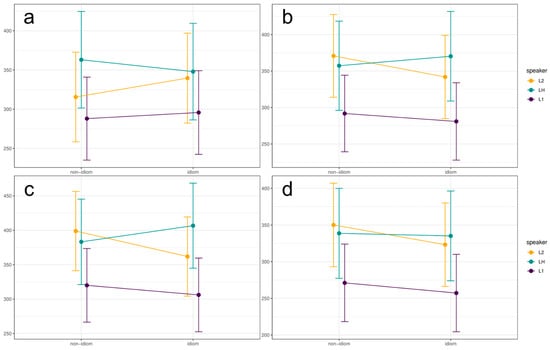

In relation to the research questions, several key processing patterns emerge (cf. Figure 1a–d). Firstly, regarding research question 1, the combined figure shows that idiomatic expressions do not consistently incur higher processing costs than their non-idiomatic counterparts, particularly among L1 speakers. This pattern aligns with the prediction that, under optimal relevance conditions, idiomatic units can be processed as efficiently as non-idiomatic ones. Secondly, in line with research question 2, both heritage and L2 speakers exhibit longer reading times than L1 speakers across all AOI, especially in the areas of the expression, reflecting greater processing effort for both idiomatic and non-idiomatic expressions. Finally, research question 3 is supported by the finding that heritage speakers face greater difficulties than L2 speakers when processing idiomatic expressions, especially in the segments directly involving idiom comprehension.

Figure 1.

(a–d) Predicted total reading times with 95% confidence intervals across speaker groups and expression types for each of the four areas of interest (AOI): (a) Full utterance; (b) Target expression; (c) Key lexical element; (d) Complementary lexical element.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. On the Processing of Idioms and Non-Idioms in L1 Speakers

According to the Multidetermined Model, idioms, particularly opaque ones like lista negra, are less effortful to process than their non-idiomatic counterparts (e.g., lista secreta) due to higher familiarity and frequency, and lower literalness and transparency. This claim is supported by our experimental results: L1 speakers showed slightly shorter total reading times for idiomatic expressions, providing an answer to research question 1. The processing advantage for idioms was evident both in the construction of mental representations and their integration into the broader utterance. These findings suggest that under optimal relevance conditions, non-literal meanings do not incur additional cognitive cost.

From a Relevance Theory perspective (Sperber & Wilson, 1995), these findings are explained by L1 speakers’ ability to directly access encoded meanings in conventional and opaque idioms. This allows them to retrieve structured concepts from the mental lexicon without relying on word-by-word compositional analysis, thus reducing inferential effort and speeding up interpretation. In supportive communicative contexts that meet expectations of relevance, this process becomes even more efficient, as interpretation involves minimal construction of ad hoc concepts and instead draws on stored figurative meanings (Carston, 2012; Wilson & Carston, 2007).

Idiomatic expressions support processing at two key stages: initial representation (first-pass) and reanalysis (re-reading). Among L1 speakers, idioms are accessed faster than non-idiomatic phrases, likely because they involve fewer computational operations than compositional interpretations. This supports models suggesting that idioms are recognized early and processed online based on lexical and contextual features (Libben & Titone, 2008). As Escandell-Vidal (2020) and Vega-Moreno (2003) note, lexical items offer procedural instructions rather than fixed meanings. In idioms, these instructions activate structured concepts holistically, minimizing inferential adjustment. Consequently, reanalysis becomes less necessary. Non-idiomatic expressions, by contrast, require integrating individual lexical meanings contextually, which increases cognitive effort and the likelihood of rereading when initial interpretations fall short of relevance. Thus, reduced rereading times for idioms reflect minimizes cognitive costs due to direct conceptual retrieval.

Taken together, the findings show no evidence that idiomatic units are harder to integrate into utterances than non-idiomatic expressions under the conditions tested. Theoretically, these results suggest a unified explanation for two observations: idiomatic expressions do not entail additional local effort, nor do they hinder discourse integration. This relative ease of processing challenges the assumption that literalness is preferable or even the default communicative strategy. The concept of relevance offers a coherent account in which idioms are processed similarly to other forms of figurative language, such as metaphor or hyperbole, via pragmatic enrichment (Carston, 2002; Wilson & Carston, 2007).

Idiom comprehension involves constructing context-specific, ad hoc concepts rather than retrieving fixed meanings. These adjusted concepts result from aligning encoded meaning with contextual assumptions and communicative goals (Wilson, 2011). For example, interpreting black humor requires generating a concept (black humor*) that includes implications like irony or morbidity not found in the literal meanings of its components. Processing can follow two cognitive routes: a top-down strategy that retrieves the idiom as a holistic unit, and a bottom-up approach involving compositional analysis. While the top-down route is more efficient and typically preferred, unfamiliar or variant idioms may demand a combination of both strategies (Vega-Moreno, 2003). In these cases, additional effort is justified by increased contextual or humorous relevance. Thus, idiom comprehension depends on inferential mechanisms shaped by factors such as familiarity, transparency, and context, rather than by fixed templates alone.

4.2. On the Processing of Idioms and Non-Idioms in L1, L2, and Heritage Speakers

The results indicate that, despite their differences, both L2 and heritage speakers exhibit greater processing effort than L1 speakers when dealing with both idiomatic and non-idiomatic expressions.

Relevance Theory offers a useful framework for interpreting the processing differences observed across speaker groups. Heritage and L2 speakers, often exposed to idiomatic language in more limited, fragmented, or instructional contexts, may lack fully lexicalized representations of idioms. Consequently, they rely more on context-driven inferential strategies to construct meaning, particularly when idioms are opaque or unfamiliar. This reliance increases cognitive effort, as ad hoc concepts must be assembled without the support of stored structured meanings, leading to slower reading and reduced processing efficiency. Unlike L1 speakers, who can retrieve idiomatic concepts more directly from the lexicon, heritage and L2 speakers face greater interpretive demands, especially in the absence of strong contextual cues (Libben & Titone, 2008).

In regard to research question 2: heritage and L2 speakers exhibit longer processing times compared to L1 speakers when interpreting both idiomatic and non-idiomatic expressions. These findings support the view that reduced exposure to idiomatic input and incomplete acquisition may limit the strategic handling of figurative language in these groups, in contrast to the more efficient and automatized processing observed in L1 speakers.

Heritage speakers show greater processing difficulties with idioms than L2 speakers. Two main types of difficulties are observed: firstly, increased local effort in the construction of idiomatic meaning; and secondly, no observable facilitation over L2 speakers when integrating idiomatic expressions into context. This supports previous claims that heritage speakers tend to favor non-idiomaticity and avoid semantic opacity (Boumans, 2006; Brehmer & Czachór, 2012; Polinsky, 2018). Moreover, the data respond to research question 3: given their preference for non-idiomatic and analytically structured forms, heritage speakers experience greater processing difficulties with familiar, opaque, and idiomatic units compared to L2 speakers.

L2 and heritage speakers display distinct processing strategies. L2, like L1 speakers, tend to recognize idiomatic units more efficiently but struggle with their contextual integration. Heritage speakers, by contrast, show stronger discourse-level integration but face challenges in decoding idiomatic meaning locally. These patterns reflect different acquisition trajectories: heritage speakers benefit from early, naturalistic exposure (Montrul, 2006; Montrul & Rodríguez Louro, 2008), enhancing top-down discourse strategies, while L2 learners rely more on explicit instruction and bottom-up lexical processing. This division aligns with models distinguishing between automatic and controlled processing (Ellis, 2009; Segalowitz, 2010). Relevance Theory provides a principled account of these patterns by distinguishing between lexicalized concepts and ad hoc concept construction (Carston, 2002; Wilson & Carston, 2007). While L2 speakers depend more on the direct retrieval of lexicalized idiomatic templates, heritage speakers often engage in online inferential adjustment to construct contextually appropriate ad hoc concepts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V.F., A.C., M.T., I.R.F. and Ó.L.L.; Data curation, A.C. and M.T.; Formal analysis, P.V.F., A.C. and M.T.; Investigation, P.V.F., A.C., M.T. and I.R.F.; Methodology, P.V.F., A.C., M.T. and I.R.F.; Project administration, P.V.F.; Supervision, P.V.F.; Validation, P.V.F. and Ó.L.L.; Visualization, A.C., M.T., I.R.F. and Ó.L.L.; Writing—original draft, P.V.F. and M.T.; Writing—review & editing, P.V.F., A.C., M.T., I.R.F. and Ó.L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved a non-invasive eye-tracking experiment without health-related or sensitive personal data, in accordance with national regulations and the internal ethical guidelines of Heidelberg University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the Open Science Framework (OSF) at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ZCMTD, accessed on 17 April 2025. The code of the statistical analysis is openly available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15648840, accessed on 17 April 2025.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the StaBLab advisory team and especially Lisa Kleinlein and Helen Alber of the Institute of Statistics, University of Munich, for providing the code for the statistical analysis of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arunachalam, S. (2013). Experimental methods for linguists. Language and Linguistics Compass, 7(4), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, S. D., & Weber, A. (2016). Bilingual and monolingual idiom processing is cut from the same cloth: The role of the L1 in literal and figurative meaning activation. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, S. D., & Weber, A. (2021). Phrasal learning is a horse apiece: No recognition memory advantages for idioms in L1 and L2 adult learners. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 591364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumans, L. (2006). The attributive possessive in Moroccan Arabic spoken by young bilinguals in the Netherlands and their peers in Morocco. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 9, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehmer, B., & Czachór, A. (2012). The formation and distribution of the analytic future tense in Polish–German bilinguals. In K. Braunmüller, & C. Gabriel (Eds.), Multilingual individuals and multilingual societies (pp. 297–314). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, H., Dobrovol’skij, D. O., Kühn, P., & Norrick, N. R. (Eds.). (2007). Phraseologie: Ein internationales handbuch zeitgenössischer forschung = Phraseology: An international handbook of contemporary research (Vols. 1 and 2). Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciari, C., & Glucksberg, S. (1991). Understanding idiomatic expressions: The contribution of word meanings. In G. Simpson (Ed.), Understanding word and sentence (pp. 217–240). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, G. (2021). Psycholinguistic approaches to figuration. In S. A. Soares da (Ed.), Figurative language–intersubjectivity and usage (pp. 307–338). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, G., & Conklin, K. (2014). Getting your wires crossed: Evidence for fast processing of L1 idioms in an L2. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 17(4), 784–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, G., & Conklin, K. (2017). Cross language lexical priming extends to formulaic units: Evidence from eye-tracking suggests that this idea ‘has legs’. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 20(2), 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrol, G., & Conklin, K. (2020). Is all formulaic language created equal? Unpacking the processing advantage for different types of formulaic sequences. Language and Speech, 63(1), 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carston, R. (Ed.). (2002). Thoughts and utterances: The pragmatics of explicit communication. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Carston, R. (2012). Relevance theory. In G. Russell, & D. Graff Fara (Eds.), Routledge companion to the philosophy of language (pp. 163–176). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carston, R. (2016). The heterogeneity of procedural meaning. Lingua, 175, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslicka, A. (2006). Literal salience in on-line processing of idiomatic expressions by second language learners. Second Language Research, 22, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieślicka, A. B., Heredia, R. R., & García, A. C. (2021). The(re)activation of idiomatic expressions (La(re)activación de expresiones idiomáticas). Studies in Psychology, 42(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clahsen, H., & Felser, C. (2006). Grammatical processing in language learners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 27(1), 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, L. (2014). The comprehension of ambiguous idioms in context. In C. Cacciari, & P. Tabossi (Eds.), Idioms: Processing, structure, and interpretation (pp. 163–200). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, K., & Schmitt, N. (2008). Formulaic sequences: Are they processed more quickly than nonformulaic language by native and nonnative speakers? Applied Linguistics, 29, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronk, B. C., & Schweigert, W. A. (1992). The comprehension of idioms: The effects of familiarity, literalness, and usage. Applied Psycholinguistics, 13(2), 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchiarini, C., Hubers, F., & Strik, H. (2022). Learning L2 idioms in a CALL environment: The role of practice intensity, modality, and idiom properties. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 863–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKeyser, R. M. (1997). Beyond explicit rule learning: Automatizing second language morphosyntax. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(2), 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diggle, P., Heagerty, P., Liang, K.-Y., & Zeger, S. (2002). Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R. (2009). Implicit and Explicit Learning, Knowledge and Instruction. In R. Ellis, S. Loewen, C. Elder, R. Erlam, J. Philp, & H. Reinders (Eds.), Implicit and explicit knowledge in second language learning, testing and teaching (pp. 3–26). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escandell-Vidal, M. V. (2020). Léxico, gramática y procesos cognitivos en la comunicación lingüística. In M. V. Escandell-Vidal, J. Amenós Pons, & A. K. Ahern (Eds.), Pragmática (pp. 39–59). Akal. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrmeir, L., Kneib, T., Lang, S., & Marx, B. (2013). Regression: Models, methods and applications. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, M., & Loureda Lamas, Ó. (2025). Spanish as a heritage language: A global perspective. In M. Lacorte (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of hispanic applied linguistics (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, D. J., & Jenkins, C. (1973). Some effects of context on the comprehension of ambiguous sentence. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R. W. (1980). Spilling the beans on understanding and memory for idioms in conversation. Memory & Cognition, 8, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R. W., & Colston, H. L. (2007). Psycholinguistic aspects of phraseology: American tradition. In H. Burger, D. Dobrovol’skij, P. Kühn, & N. R. Norrick (Eds.), Phraseologie: Ein internationales handbuch zeitgenössischer forschung = Phraseology: An international handbook of contemporary research (Vol. 2, pp. 819–836). Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R. W., & Gonzales, G. P. (1985). Syntactic frozenness in processing and remembering idioms. Cognition, 20(3), 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridneva, E. M., Ivanenko, A. A., Zdorova, N. S., & Grabovskaya, M. A. (2023). The processing of Russian idioms in heritage Russian speakers and L2 Russian learners. Linguistics and Intercultural Communication, 21(4), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. J. (2002). The automatic cognate form assumption: Evidence for the parasitic model of vocabulary development. International Review of Applied Linguistics (IRLA), 40(2), 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, K., Nyström, M., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., & van de Weijer, J. (2011). Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hulstijn, J. H. (2019). An individual-differences framework for comparing nonnative with native speakers: Perspectives from BLC theory. Language Learning, 69, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N., & Nekrasova, T. (2007). The processing of formulaic sequences by second language speakers. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, J., & Garrett, M. (1972). Resolving ambiguity: Effect of biasing context in the unattended ear. Cognition, 1, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langacker, R. W. (1987). Foundation of cognitive grammar (Vol. 1). Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Libben, M. R., & Titone, D. A. (2008). The multidetermined nature of idiom processing. Memory & Cognition, 36, 1103–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureda, Ó., Cruz, A., Recio Fernández, I., & Rudka, M. (2021). Comunicación, partículas discursivas y pragmática experimental. Arco Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, A. (2009). The linguistic similarities of Spanish heritage and second language learners. Foreign Language Annals, 41, 252–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlock, T., & Heredia, R. R. (2002). 11 Understanding phrasal verbs in monolinguals and bilinguals. Advances in Psychology, 134, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, M. S., Glucksberg, S., & Cacciari, C. (1994). Semantic productivity and idiom comprehension. Discourse Processes, 17, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2006). On the bilingual competence of Spanish heritage speakers: Syntax, lexical-semantics and processing. International Journal of Bilingualism, 10(1), 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S. (2015). The acquisition of heritage languages. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montrul, S., & Rodríguez Louro, C. (2008). Beyond the syntax of the null subject parameter: A look at the discourse-pragmatic distribution of null and overt subjects by L2 learners of Spanish. In The acquisition of syntax in Romance languages (pp. 401–418). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Fernández, F. (2024). Nociones sobre lenguas de herencia. Dirigidas al profesorado de español. In S. Bailini, M. V. Calvi, & E. Liverani (Eds.), El español como lengua de mediación en contextos educativos y profesionales. II congreso de Español como lengua extranjera en Italia (CELEI) (pp. 10–25). Instituto Cervantes. [Google Scholar]

- Noveck, I. A., Griffen, N., & Mazzarella, D. (2023). Taking stock of an idiom’s background assumptions: An alternative relevance theoretic account. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1117847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortony, A., Schallert, D. L., Reynolds, R. E., & Antos, S. J. (1978). Interpreting metaphors and idioms: Some effects of context on comprehension. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 17, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, M., Traxler, M. J., & Crocker, M. W. (2000). Ambiguity resolution in sentence processing: Evidence against frequency-based accounts. Journal of Memory and Language, 43(3), 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polinsky, M. (2018). Heritage languages and their speakers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. (1998). Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 124(3), 372–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayner, K. (2009). Eye movements and attention in reading, scene perception, and visual search. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62(8), 1457–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Reichle, E. D., Rayner, K., & Pollatsek, A. (2003). The E-Z reader model of eye-movement control in reading: Comparisons to other models. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 26(4), 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rommers, J., Dijkstra, T., & Bastiaansen, M. (2013). Context-dependent semantic processing in the human brain: Evidence from idiom comprehension. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 25(5), 762–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalowitz, N. (2010). Cognitive bases of second language fluency. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Segalowitz, N., & Hulstijn, J. (2005). Automaticity in bilingualism and second language learning. In J. F. Kroll, & A. M. B. De Groot (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches (pp. 371–388). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siyanova-Chanturia, A., Conklin, K., & Schmitt, N. (2011). Adding more fuel to the fire: An eye-tracking study of idiom processing by native and non-native speakers. Second language Research, 29(2), 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1995). Relevance: Communication and cognition (2nd ed.). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Swinney, D. (1976). Does context direct lexical access? Midwestern Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Swinney, D., & Cutler, A. (1979). The access and processing of idiomatic expressions. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabossi, P., Fanari, R., & Wolf, K. (2009). Why are idioms recognized fast? Memory & Cognition, 37, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, N. (2008). The effect of working memory, semantic access, and listening abilities on the comprehension of conversational implicatures in L2 English. Pragmatics & Cognition, 16(3), 517–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titone, D., & Libben, M. (2014). Time-dependent effects of decomposability, familiarity and literal plausibility on idiom priming: A cross-modal priming investigation. The Mental Lexicon, 9(3), 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, A., Derwing, B., Libben, G., & Westbury, C. (2011). Processing advantages of lexical bundles: Evidence from self-paced reading and sentence recall tasks. Language Learning, 61(2), 569–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, G., Schmitt, N., & Galpin, A. (2004). The eyes have it: An eye-movement study into the processing of formulaic sequences. In Schmitt (Ed.), Formulaic sequences: Acquisition, processing and use (pp. 153–172). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlancker-Sidtis, D. (2003). Auditory recognition of idioms by native and nonnative speakers of English: It takes one to know one. Applied Psycholinguistics, 24, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanPatten, B. (Ed.). (2004). Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Moreno, R. E. (2001). Representing and processing idioms. UCL Wording Papers in Linguistics, 13, 73–107. [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Moreno, R. E. (2003). Relevance Theory and the construction of idiom meaning. UCL Wording Papers in Linguistics, 15, 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D. (2011). The conceptual-procedural distinction: Past, present and future. In V. Escandell-Vidal, M. Leonetti, & A. Ahern (Eds.), Procedural meaning: Problems and perspectives (pp. 1–31). Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. (2016). Reassessing the conceptual-procedural distinction. Lingua, 175, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D., & Carston, R. (2007). A unitary approach to lexical pragmatics: Relevance, inference and ad hoc concepts. In R. Burton (Ed.), Pragmatics (pp. 230–259). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S. N. (2017). Generalized additive models: An introduction with R. Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, A. (2002). Formulaic language and the lexicon. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).