Abstract

Despite the increase in studies on Spanish as a heritage language (SHL), few focus on spelling, with research limited to the U.S. According to the adaptive control hypothesis, language production is governed by control processes, which adapt to the demands of real-world interactional contexts. In this article, these control processes are inferred from the interlingual spelling errors observed in Gibraltarian SHL speakers. The hypothesis is that the Gibraltar dense code-switching context will be manifested in a high number of interlingual misspellings in Spanish due to English interference. Misspellings were identified in the written productions of a sample of 80 Gibraltarian pre-college SHL students (N = 40 in Spanish; N = 40 in English), collected via availability tests and stored in the Dispolex dataset by the members of the project “Lenguas en contacto y disponibilidad léxica: la situación lingüística e intercultural de Ceuta y Gibraltar”. Gibraltarians’ Spanish misspellings were then compared with those found in the U.S. The high percentage of spelling errors in SHL students in Gibraltar might be explained in light of lower inhibitory control of interferences in dense code-switching interactional contexts.

1. Introduction

1.1. Spelling and Orthographic Processing: Cognitive and Linguistic Factors

In this study, we intended to expand our understanding of SHL speakers’ spelling competence since there are few empirical studies that address this issue despite the fact that spelling is “a major stumbling block for Spanish heritage language (SHL) learners” (Beaudrie, 2017, p. 596), with research limited to the U.S. context (Beaudrie, 2012; Carreira & Kagan, 2018; Llombart-Huesca, 2018, 2024; Belpoliti & Bermejo, 2019; Llombart-Huesca & Zyzik, 2019).

Although spelling is “an aspect of literacy that causes significant difficulties for Spanish heritage language learners” (Llombart-Huesca & Zyzik, 2019, p. 1), there is a lack of research on how these types of bilingual speakers process orthography. SHL speakers usually have an advantage in oral production and comprehension, but due to their lack of formal instruction in Spanish, they experience difficulties with reading, writing, and spelling (Burgo, 2015).

Spelling is defined as “the expression of orthographic knowledge regardless of the modality of output” (Tainturier & Rapp, 2001, p. 263). For Kilpatrick (2015), spelling is an index of orthographic knowledge, which proves that the learner knows the correct orthographic representation of a given word. Orthographic processing is “the ability to form, store, and access orthographic representations” (Cunnigham & Stanovich, 1993, p. 193), so it is associated with both linguistic and nonlinguistic cognitive skills (Bialystok, 2001), such as memory, attention, analytical capacity (Bialystok, 2004), problem-solving, and phonological, orthographic and morphological awareness. As spelling is a convention that needs to be learned, only speakers who are literate can rely on orthographic awareness and use it as a second information source to spell words (Dominiek, 2019).

In bilingual contexts, spelling also involves working memory (Bialystok et al., 2012), control monitoring, and interference suppression (Kerns et al., 2004). This bilingual flexibility and the ability to control transfer between languages can lead to other cognitive advantages, such as enhanced metalinguistic skills (Bialystok et al., 2014), which are crucial for literacy development.

According to the NSW Department of Education and Training (2007), students should be explicitly taught four types of knowledge to enable them to integrate spelling strategies in writing: phonological (how sounds correspond to letters), visual (how words look), morphemic (word meanings and spelling changes in different grammatical situations), and etymological (origins of words and their meanings). Phonological awareness, defined by Torgensen et al. (1994, p. 276) as “sensitivity to, or explicit awareness of, the phonological structure of the words in [a] language,” involves recognising and manipulating sounds in spoken words and includes different levels (e.g., word, syllable, and phoneme awareness) and skills (e.g., rhyming, blending, and segmenting sounds).

Based on the triple word form theory (Bahr et al., 2015), “students are capable of drawing on and coordinating phonological, orthographic, and morphological skills from quite early in their spelling development” (Daffern et al., 2015). The orthographic knowledge of words can be retrieved by literate speakers (Dominiek, 2019) in two ways: (1) by retrieving stored spellings from the orthographic lexicon through the lexical (or visual) route (Tainturier & Rapp, 2001) or (2) by converting phonological information into orthographic representations through the sub-lexical (or phonological) route. This dual-route model (Coltheart, 1978) implies both word-level and sub-word-level knowledge, the former for irregular (or sight) words without grapheme–phoneme correspondence rules and the latter for regularly spelled words through the phonological route.

Orthographic patterns are progressively learned (Apel, 2011) by means of “accumulated statistical knowledge about how letters typically combine in words” (Powell et al., 2014, p. 193). This statistical knowledge is necessary to learn the phonotactic rules of the language, that is, the strings of phonemes and letters that can be combined in a language. For example, in Spanish, it is incorrect to use the digraph <ll> at the end of a word, but it is very common in English (e.g., call, fall, install, etc.).

In line with the orthographic depth hypothesis (Katz & Frost, 1992), reading acquisition should be easier in orthographically shallow Spanish than in opaque English because of the more consistent mapping between letters and sounds in Spanish orthography. Ziegler and Goswami (2005) associated the orthographic consistency of a language with the dual-route model, so in a transparent language like Spanish, the child relies on the phoneme-to-grapheme relationships (sub-lexical or phonological route), but the opacity of the English language also demands the lexical (or visual) route.

1.2. Orthographic Transfer Between Languages: Cognitive Competition or Advantage?

In their research with bilingual speakers, Sun-Alperin and Wang (2011, p. 591) found that “orthographic patterns may be language specific, thereby not likely to transfer to spelling performance.” However, Zutell and Allen (1988), in their study on the effect of Spanish pronunciation and spelling on bilingual Hispanic children in the U.S., found that some of their spellings of English words were influenced by Spanish phonology, although more successful spellers differentiated between Spanish and English systems, so their English spelling errors showed little transfer from Spanish.

Kaushanskaya and Marian (2009) observed that English–Spanish bilinguals outperformed monolinguals in the reduction of interference during novel-word learning, as bilinguals’ knowledge of two languages facilitated vocabulary learning and shielded them from interference associated with cross-linguistic inconsistencies in letter-to-phoneme mappings. Phonological activation in English monolinguals differed from that in English–Spanish bilinguals because the latter were able to activate two phonological systems for the same orthographic input, including discrepant phonemes. This experience with mapping the same orthography onto two divergent phonological systems could have “modified the connectivity between English orthography and English phonology in English–Spanish bilinguals” (Kaushanskaya & Marian, 2009, p. 834).

Benmamoun et al. (2013, p. 132) do not focus on bilingual advantages in general but on heritage speakers in particular, who can experience some difficulties with “lexical retrieval, the use of codeswitching to fill lexical gaps, divergent pronunciation, morphological errors, avoidance of certain structures, and overuse of other structures due to transfer from the dominant language”.

Bilinguals’ cross-linguistic activation of lexical items with similar phonology and orthography may result in a competitive relationship between the phonological and orthographic features of each language (Van Heuven et al., 1998; Dijkstra & Van Heuven, 2002). For the study of this cognitive competition, Dean and Valdés Kroff (2017) employed eye tracking to investigate whether the interaction of orthographic–phonological mappings in bilinguals promoted interference and found that Spanish-dominant bilinguals were influenced by the orthographic mappings of their less-dominant language (English).

According to Brown (2000, p. 209), when acquiring/learning languages, six possible levels of difficulty may be encountered (Al-Sobhi, 2019), depending on the differences existing between the two systems (L1 and L2):

- 0.

- Transfer (positive transfer due to the lack of differences between L1 and L2);

- 1.

- Coalescence (the presence of two different items in L1 that correspond to one in L2);

- 2.

- Underdifferentiation (when one item exists in L1 but not in L2);

- 3.

- Reinterpretation (when one item in L1 exists in L2, but it is used differently);

- 4.

- Overdifferentiation (when one item exists in L2 but not in L1);

- 5.

- Split (the presence of two different items in L2, which correspond to only one in L1).

If these levels are applied to bilingual speakers of English (L1) and Spanish (L2), difficulties related to the inhibition of interferences between the two languages could affect levels 1 to 5 (Mariscal, 2021a):

- Coalescence: the phoneme /d/ may be represented by both <d> (door) and <dd> (teddy bear) in English but only by <d> (dinero) in Spanish;

- Underdifferentiation: the digraph <ph> does not exist in Spanish;

- Reinterpretation: although the spelling pattern <s+consonant> may be employed in both languages, it can be written at the beginning of the word in English, as in star and Spain, while in Spanish, it is compulsory to insert an <e> before <s>, as in estrella and España;

- Overdifferentiation: <ñ> is only present in the Spanish alphabet;

- Split: the phoneme /b/ never represents <v> in English, but in Spanish, it corresponds both to <b> and <v>.

In their research on orthographic processing in balanced bilingual children, Schröter and Schroeder (2016) identified cross-language evidence from cognates and false friends during a reading task and found that the sample of balanced bilingual children was more similar to bilingual adults than to child second-language learners when resolving orthographic ambiguity. The results show a processing advantage for cognates over controls in both languages, where the facilitation effect was not attributed to print exposure, that is, the amount of reading practice (Chetail, 2024), but to language proficiency.

However, other studies argue that print exposure has a positive impact on reading and language processes (Stanovich & West, 1989; Duursma et al., 2007; Mol & Bus, 2011; Niklas & Schneider, 2013; Chetail, 2024) because visual memory may favour vocabulary development (Pickering et al., 2023), which can also improve spelling skills.

1.3. Influence of the Interactional Context in Interference Control

Not only do linguistic and cognitive factors (Dominiek, 2019) intervene in bilingual acquisition, but also other social and educational parameters. As stated by Pearson (2007), one-quarter of children in potentially bilingual environments do not become bilingual, and this is attributed to five social elements: input, language status, access to literacy, family language use, and community support, including schooling.

From the matrix-based characterisation of heritage speakers (Valdés, 1997), these bilingual learners1 are also influenced by their “demographic characteristics, along with the extent and nature of heritage language usage in the family and the community” (Belpoliti & Bermejo, 2019, p. 11), which both impact their language proficiency (Said-Mohand, 2011), as well as by other variables, such as age of acquisition, birth order, origin of parents, and self-confidence (Silva-Corvalán, 2004).

Additionally, transfer normally occurs from the prestige language in society, which is, according to Serrano Zapata (2014), less prone to interference or borrowing (even if it is the speaker’s native language); the medium of instruction in schools affects the development of literacy in minority languages; and dialectal variations can be manifested in the phonetic spelling of words only learned in the oral form in informal contexts (Mariscal, 2022). If applied to orthographic processing, SHL students in Gibraltar must face several challenges (Mariscal, 2022, pp. 77–78), as linguistic input in Spanish is mainly oral, the only medium of instruction is English, and print exposure is mostly in the latter, with Spanish literacy delayed in formal schooling until middle school (Government of Gibraltar, 2025).

When referring to the cognitive demands of language control in bilingual speakers, Green and Abutalebi (2013) identify three different real-world interactional contexts —single-language, dual-language, and dense code-switching contexts— which determine the type of language control processes. Green and Abutalebi (2013) distinguish eight control processes: goal maintenance, conflict monitoring, interference suppression, salient cue detection, selective response inhibition, task disengagement, task engagement, and opportunistic planning. These processes would be imposed by the speaker’s interactional2 context: (1) in a single-language context, one language is used in one environment and the other in a second distinct environment; (2) in a dual-language context, both languages may be used in the same environment, but separately and with different speakers; and (3) in a dense code-switching context, speakers usually switch between languages for communicative purposes.

According to the adaptive control hypothesis (Green & Abutalebi, 2013), speakers in a dual-language context must face a “control dilemma” by monitoring conflict and suppressing interference to avoid switching to the other language and controlling “cross-language intrusion errors” (because there is a competitive relationship between languages). On the contrary, speakers in a dense code-switching context establish a cooperative relationship between the two systems and use them both simultaneously. Despite the influence that the interactional context may have on interference suppression, individual differences, such as those related to executive control processes, can also condition its control and suppression.

However, Lai and O’Brien (2020, p. 1) believe there is “fluidity in bilinguals’ interactional contexts”, so Green and Abutalebi’s (2013) distinction might not be evident in a multilingual society. For example, Gibraltar is a heterogeneous speech community where the three interactional contexts can be found. Monolingual speakers of English would be included in Green and Abutalebi’s (2013) single-language context (one language in one environment), whereas Spanish-English bilinguals, in general, and Spanish heritage speakers in particular, could participate in single-language, dual-language, and dense code-switching contexts.

The hypothesis is that the Gibraltar interactional context of language contact will be manifested in a large number of interlingual spelling errors due to interference. In line with previous research on bilingual spelling in Gibraltar and the use of both English and Spanish by SHL speakers for communication in different contexts (Mariscal, 2022), the results will now be compared with those in Beaudrie (2012) and Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019), who observed a limited presence of transfer in the U.S. context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample in Gibraltar

The study sample comprises 80 pre-college SHL students (age range: 14–16; sample A (N = 40) and sample B (N = 40)), who were all born in Gibraltar and spoke both English and Spanish from birth. The students were in their final year (Year 10) in two state comprehensive schools3 in the area.

Gibraltar is a small British overseas territory located in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula, where the English language interacts with Spanish. As Gibraltar belongs to the U.K., English is the only official language, while Spanish is labelled as a “foreign language” (Mariscal, 2019) despite part of its population acquiring oral Spanish at home from birth and regularly code-switching between English and Spanish in their interactions with other bilingual speakers.

This under-researched population in heritage language studies is constituted by both monolingual speakers of English and bilinguals, who speak English and Yanito (Levey, 2015), “a spoken Spanish-dominant variant, which incorporates English lexical and syntactic constituents as well as some unique local lexical items” (Levey, 2006, pp. 724–725), whose borrowings come from the linguistic diversity of this territory throughout the centuries (Macdonald, 2024). Yanito shares some oral features with Southern Spanish, such as seseo (/s/ replaces /θ/, as in [sapato]/zapato); ceceo (/θ/ replaces /s/, as in [cillón]/sillón); yeísmo (the pronunciation of /ʎ/ as /y/, as in [yover]/llover); the loss of /d/ in the intervocalic position ([enfadao]/enfadado); the aspiration of /s/ at the end of a syllable ([lo’ niño’]/los niños); the realisation of /x/ as [h] ([paha]/paja) and /tʃ/ as /ʃ/ ([noʃe]/noche); the confusion of /r/ and /l/ ([durce]/dulce); gemination (e.g., the doubling of /n/ in [canne]/carne); and the loss of final consonants ([perdí]/perdiz).

According to Pascual and Torres (2022, p. 39), bilinguals in Gibraltar should be considered SHL speakers for the following reasons (Mariscal, 2022, pp. 62–64):

- Spanish is not the prestige language of society;

- Although attitudes towards Spanish may vary, it is stigmatised by a number of speakers, who consider it only appropriate for informal contexts;

- Spanish is only employed when code-switched with English (Moyer, 1992; Goria, 2021; García Caba, 2022), which may be due to SHL speakers’ lack of competence in formal Spanish4 (Errico, 2015);

- In the educational field, children have more opportunities to develop their written skills in English since it is the only medium of instruction, as the Gibraltar education system is regulated by the British Curriculum (U.K. Government, 2013);

- The explicit teaching of Spanish does not begin until middle school (Year 3) when monolingual speakers of English begin to learn it as a foreign language;

- At the beginning of formal schooling, SHL children only acquire literacy in English, and instruction is also in English, so their input in Spanish, which is essentially oral and informal, is reduced;

- Interlingual transfer is mostly from English to Spanish and occurs as loans, calques, and other interferences.

2.2. Data Collection and Corpus Compilation

The corpus of misspellings in Spanish and English was obtained from the information stored by the members of the research project “Lenguas en contacto y disponibilidad léxica: la situación lingüística e intercultural de Ceuta y Gibraltar” (BFF2000–0511) in the Dispolex dataset, which had been collected through a lexical availability test administered to 266 Gibraltarian students (137 in Spanish and 129 in English). The tests, designed according to the methodological criteria of “Proyecto Panhispánico” (Samper Padilla, 2003), had been previously approved by the school headmaster. Before obtaining the informants’ verbal informed consent, both the participants and their parents were fully informed about the voluntary nature of the survey, the anonymity of the answers, and how the data would be used, although they did not know the research was associated with spelling competence to avoid conditioning their answers.

After signing an ethical form, we were given access to the Dispolex dataset, from which 80 anonymous tests were selected: 40 in Spanish (sample A) and 40 in English (sample B). The selection was based on two criteria: the informants were SHL speakers who were born in Gibraltar and spoke both English and Spanish from birth (early bilinguals). It was not possible to compare the results of the participants in each language as they had been surveyed either in Spanish or English by the members of the project “Lenguas en contacto y disponibilidad léxica: la situación lingüística e intercultural de Ceuta y Gibraltar”.

In bilingual contexts, lexical availability tests are used to assess productive vocabulary in the two language systems (Sánchez-Saus Laserna, 2019; Serrano Zapata, 2024). The test involved writing words belonging to 21 specific semantic categories called “centres of interest”, such as parts of the human body, clothes, furniture, food and drink, school, transport, animals, games and other leisure activities, jobs, colours, physical and personality features, and religion. The participants were given 2 min per centre of interest to complete the task. Benmamoun et al. (2013) and Pascual and Torres (2022) explain that although bilingual speakers’ lexical knowledge is often smaller in the heritage language, they frequently have sufficient vocabulary, but this is mainly acquired orally in informal contexts, which can lead to misspellings.

The misspellings in the written productions of samples A and B were compiled separately in two corpora and employed to make inferences of the underlying orthographic processes behind the errors in each language and identify interference between languages.

2.3. Taxonomy for the Classification of Spelling Errors in Gibraltar

For the classification of spelling errors in Spanish and English, they were divided into three main categories (Table 1): phonological, orthographic/graphic, and morphological errors reflected in spelling. This taxonomy is based on the triple word form theory (Bahr et al., 2015) and the dual-route model (Coltheart, 1978).

Table 1.

Taxonomy for the analysis of spelling errors in Gibraltar (adapted from Mariscal, 2022).

- Morphological errors reflected in spelling are those that reflect an incorrect word formation, such as errors in the representation of gender (e.g., *delphinas/delfines; *pimiento/pimienta; *plato/plata in “colours”; and *tizo/tiza) and/or number (e.g., *delfinoes/delfines) and the incorrect writing of prefixes, suffixes and verb endings, which may be intralingual or interlingual (e.g., *delfinoes is formed as in potatoes and tomatoes in English). Lexical errors in the wrong formation of words that do not manifest misspellings, such as *agotación/agotamiento, *cocinador/cocinero; *cafetenario/cafetería; *desesperadación/desesperación; *futbolador/futbolista; and *populación/población (Mariscal, 2022, pp. 122–130), have not been included since they do not include spelling errors.

To avoid a mere quantitative descriptive analysis, the misspellings are explained as in Llombart-Huesca (2018), as spelling may allow us “to see how the phonological, morphological, and syntactical information of words is stored in the learner’s mind” (Llombart-Huesca, 2018, p. 211).

The errors identified in Spanish (sample A) were compared with the misspellings in English (sample B) to find differences associated with the orthographic processing of each language system. The data in Spanish were then compared with the misspellings found by Beaudrie (2012) and Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) in SHL college students in the U.S. to identify whether Gibraltar interactional code-switching is manifested as interlingual spelling errors as a result of insufficient interference control.

2.4. Beaudrie’s (2012) Methodology

Beaudrie (2012) provided a quantitative analysis of the misspellings detected in the written productions of 100 SHL learners (age range: 18–22) born in the U.S. Most of the students were of Mexican origin and belonged to immigrant families. They were enrolled in a Spanish course for fluent Spanish speakers with basic writing proficiency at a major university in the U.S. Southwest. The purpose of the study was to identify the spelling difficulties of typical SHL learners in the U.S. context.

The corpus was obtained from two untimed essays written during class time, with free writing selected to assess students’ ability to spell familiar words in Spanish. The misspellings were divided into four categories. Transfer from the English language was only measured within category (b):

- words with inconsistent or complex phoneme-to-grapheme relationships;

- words with regular (or consistent) phoneme-to-grapheme relationships;

- misspellings involving syllables and word fragmentation;

- the incorrect use of accent marks.

2.5. Belpoliti and Bermejo’s (2019) Methodology

Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) presented a descriptive error analysis of a 200-essay corpus produced by 200 SHL college students (age range: 18–30). They were all Hispanic bilinguals enrolled in a Spanish course at the University of Houston at the time of data collection. Most of the participants were born in the U.S., their parents being immigrants from Mexico and other Latin American countries. They were fluent in English but with limited abilities in Spanish, “which they reported as the language of their home and family” (Belpoliti & Bermejo, 2019, p. 19).

The main objective of the research was to describe how SHL learners managed Spanish orthographic conventions and to what extent interference from English accounted for their misspellings. The misspellings were classified into three main categories:

- an incorrect phoneme-to-grapheme relationship;

- written accent issues;

- syllable/word segmentation.

Although the categories were all based on Beaudrie’s (2012) taxonomy, Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) decided to group two of Beaudrie’s categories (“misspellings of words with inconsistent or complex phoneme-to-grapheme relationships” and “misspellings of words with regular phoneme-to-grapheme relationships”) into one: “incorrect phoneme-to-grapheme relationship”.

As shown in Table 2, the informants’ different age ranges and types of tasks may influence the number and type of misspellings of SHL speakers in Gibraltar with respect to the U.S. However, the main objective of this research was not to assess the participants’ spelling competence but to determine the presence of interference in Gibraltar and compare it with the U.S. context.

Table 2.

Contrast between the methodologies of the three studies.

3. Analysis of Misspellings in SHL Speakers in Gibraltar and the U.S.

3.1. Spanish Misspellings in Gibraltar

The corpus in Spanish was formed by 9163 words, which included 1866 incorrect items (error percentage: 20.4%): 1558 orthographic/graphic errors (55%), 1094 phonological errors (38%), and 201 morphological errors reflected in spelling (7%).

The most problematic subcategories in Spanish are as follows: (2.2) errors with written accent marks (31.7%); (1.2) an incorrect phoneme-to-grapheme relationship in regularly spelled words (15%); (1.1) errors due to the phonetic spelling of the word (12.4%); (1.3) influence of oral features of Yanito (11%); (2.5) confusion with the spelling of similar words (10.9%), errors which are 87% interlingual and 13% intralingual; (2.1) the misspelling of irregular (or sight) words (5.6%); (2.4) incorrect use of capital letters (5.2%); and (3.3) other errors in word formation (4.1%). Spelling difficulties are not observed in the subcategories (2.3), (3.1), or (3.2).

The misspellings were divided into two different subcategories, depending on their orthographic processing: either phonological (of regularly spelled words) or visual (of irregularly spelled words). For example, the most difficult relationships involved the use of the graphemes <b>/<v> (*baso/vaso), <g>/<j> (*girafa/jirafa), and <h> (*orno/horno), which makes it necessary to resort to the lexical route due to its irregular spelling nature. In some cases (e.g., *girafa), spelling errors may be described both as intralingual (irregular spelling) and interlingual (giraffe in English).

Interference from the English language may be the cause of a very common error of Gibraltarian informants, consisting of writing <j> instead of the digraph <ll> to represent the phonemes /ʎ/ and /ʝ̞/ (e.g., *vijar/billar), possibly due to the application of grapho-phonetic patterns of English, as the correspondence between /dʒ/ and <j> in jacket– and the grapheme <h>, which is always silent in Spanish (not in English), is written as <j> in *zanajoria/zanahoria but especially <g> and >j> as <h> (e.g., *cahones/cajonera, *empuhar/empujar, *estruhar/estruhjar, *hamon/jamón, *herseis/jerséis, *orehas/orejas, *ohos/ojos, and *paharo/pájaro). This could also be linked to intralingual reasons related to the pronunciation of <h> as /x/ in Yanito, as in *jarto/harto and *ajogarse/ahogarse.

The vast majority of errors in words with consistent spelling in Spanish were interlingual, with interferences from English affecting, for example, the grapheme <ñ>, which does not exist in English (e.g., *ninios/niños, *pirania/piraña, *senialar/señalar, and *unias/uñas) but especially the writing of English digraphs instead of Spanish graphemes, such as <ff> (e.g., *caffeteria/cafetería, *differente/diferente, *frigoriffico/frigorífico, and *giraffa/jirafa), <ll> (e.g., *metallico/metálico) and <zz> (e.g., *pizzara/pizarra).

3.2. English Misspellings in Gibraltar

The corpus in English was formed by 14,415 words, which included 1052 incorrect items (error percentage: 7.3%). The number of spelling errors is similar in the three main categories: 588 phonological errors (37%), 532 orthographic/graphic errors (33%), and 476 morphological errors reflected in spelling (30%).

The most problematic subcategories in English are as follows: (3.3) other errors in word formation (27%), especially those in the writing of compound words; (1.1) errors due to the phonetic spelling of the word (19%); (1.2) an incorrect phoneme-to-grapheme relationship in regularly spelled words (17.4%); (2.1) the misspelling of irregular words (sight words) (11.4%); (2.5) confusion with the spelling of similar words (10%) (80% intralingual and 20% interlingual); and (2.3) errors with punctuation marks (9.3%), which involve the incorrect use of the hyphen in compound words. Spelling difficulties are not observed in the subcategories (1.3), (2.2), (2.4), (3.1), and (3.2).

The direction of transfer is mainly from English (the prestige language in Gibraltar) to Spanish since most of the errors (80%) are intralingual. On the contrary, in the Spanish corpus, 87% of spelling errors were interlingual, and only 13% were intralingual.

Other differences between sample A (in Spanish) and sample B (in English) are shown in Table 3. The mean of errors in Spanish was 46.7 and 26.3 in English, with a standard deviation of 15.3 in Spanish and 12.5 in English.

Table 3.

Contrast between the misspellings in Spanish and English in Gibraltar.

3.3. Spanish Misspellings Observed by Beaudrie (2012) and Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) in the U.S.

3.3.1. Beaudrie’s (2012) Corpus in the U.S.

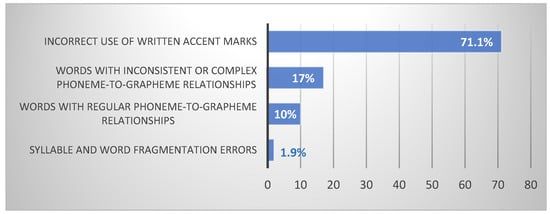

Beaudrie’s corpus included 21,322 words, which contained 2492 spelling errors (error percentage: 11.7%): 1771 accent errors (71.1%); 424 misspellings of words with inconsistent or complex phoneme-to-grapheme relationships (17%); 250 misspellings of words with regular phoneme-to-grapheme relationships (10%); and 47 syllable and word fragmentation errors (1.9%) (Figure 1). The subcategory “direct English transfer”, included in the category “words with regular phoneme-to-grapheme relationships”, only represented 2% of the informants’ errors.

Figure 1.

Misspellings by category in 100 SHL learners in the U.S. (Beaudrie, 2012).

The largest number of misspellings (71.1%) involved the incorrect use of written accent marks due to the omission of a required accent mark, as in *dificil/difícil. In the category “words with inconsistent or complex phoneme-to-grapheme relationships”, most spelling errors involved the misuse of the phonemes /s/ (*tristesa/tristeza) and /b/ (*vajar/bajar) and the silent grapheme <h> (*aber/haber). In the category “words with consistent phoneme-to-grapheme relationships”, vowels were more problematic than consonants, as in *divirtir/divertir and *encreíble/increíble, while difficulties were not observed in syllable and word fragmentation.

3.3.2. Belpoliti and Bermejo’s (2019) Corpus in the U.S.

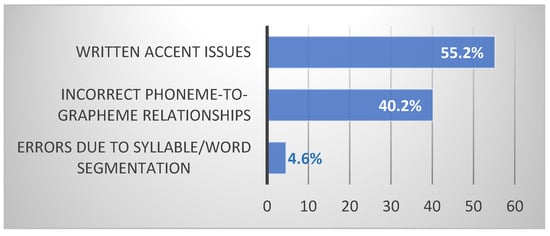

In a corpus of 34,829 words, Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) identified 5554 incorrect words (error percentage: 15.9%). The most problematic category was “written accent issues” (55.2%), followed by incorrect phoneme-to-grapheme relationships (40.2%)—most of them associated with the substitution of one grapheme by another—and errors due to syllable/word segmentation (4.6%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Misspellings by category in 200 SHL learners in the U.S. (Belpoliti & Bermejo, 2019).

Most of the errors (5148) were intralingual (92.7%), as in *asta/hasta, and only 406 were interlingual (7.3%), that is, based on interference from the English orthography, as in *technologico/tecnológico and *telephono/teléfono. According to Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019), the sample of SHL learners in the U.S. had more difficulty managing the standard Spanish writing system than controlling the transfer from the English language.

4. Discussion

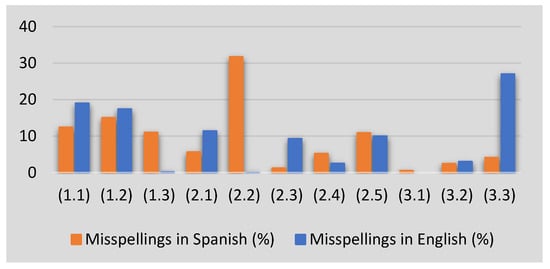

4.1. Comparison Between the Two Samples of SHL Speakers in Gibraltar

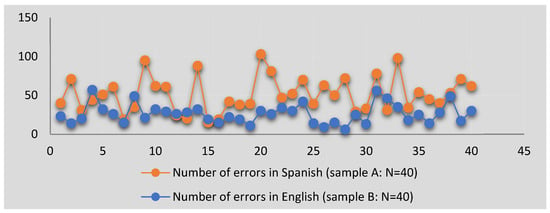

The data from the two Gibraltarian samples of SHL speakers show more spelling difficulties in Spanish, as reflected in the number of errors (Figure 3): 1866 in Spanish (mean: 46.7) and 1052 in English (mean: 26.3). The percentage of errors in Spanish is 20.4% versus only 7.3% in English, with a similar standard deviation in both samples (15.3 in sample A in Spanish and 12.5 in sample B in English).

Figure 3.

Misspellings in Spanish (sample A) and English (sample B) in Gibraltarian SHL speakers.

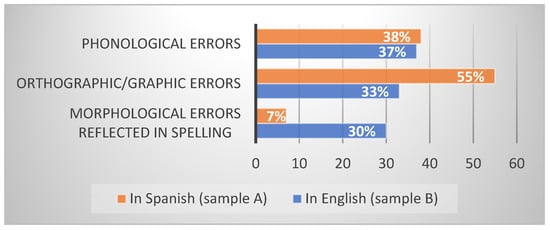

As shown in Figure 4, both samples have similar difficulties in the category “phonological errors”, which may be attributed to the fact that the students employ the phonological route to write words for the phonetic spelling of words whose written form (in Spanish and/or English) has not been stored in their mental lexicon. In Spanish, this could be explained by the lack of print exposure to this language and in English, by the opacity of its orthography, which favours the use of phonetic spelling to compensate for the students’ lack of spelling competence.

Figure 4.

Contrast of misspellings by category in Gibraltarian SHL speakers (%).

The percentage of errors in the category “orthographic/graphic errors” is higher in Spanish due to the lack of accent marks in their written productions, whereas in English, it corresponds to the number of misspellings in irregularly spelled words.

Morphological errors in English are associated with the writing of compound words, for which there are no specific rules in this language, so learners must store them in their mental lexicon through visual memory and then retrieve them through the visual route, as happens with irregular words.

With respect to subcategories (Figure 5), some differences in the number of misspellings in Spanish and English are related to the inherent characteristics of each orthography. For example, written accent marks (2.2) are not employed in English, and the use of hyphens (2.3) is more common in English; gender is not typically represented with morphemes in English (3.1), except for some words (e.g., lioness, hostess, and princess); and compound words in English (included in 3.3: “other errors in word formation”) do not follow the same spelling rules as in Spanish.

Figure 5.

Contrast of misspellings by subcategory in Gibraltarian SHL speakers (%).

The influence of the oral features of Yanito on spelling (1.3) is only present in Spanish but not transferred to the writing of English words, so interlingual transfer mostly comes from English (the prestige language) to Spanish, as reflected in the differences detected in the number of interlingual and intralingual errors in the subcategory “confusion with the spelling of similar words” (2.5): 87% interlingual and 13% intralingual in Spanish but 80% intralingual and 20% interlingual in English.

Other differences are manifested in the phonetic spelling of words (1.1) and the spelling of irregular (or sight) words (2.1), with more errors in English than in Spanish in the two subcategories. This could be explained by the opacity of the English language, which involves a bigger effort to memorise and then retrieve irregular words, for which the informants resort to both the visual and phonological routes.

If Brown’s levels of difficulty (2000) are applied to the orthographic processing of English (L1) and Spanish (L2) in Gibraltar, HSL learners have to inhibit transfer in levels 1 to 5:

- 0.

- Transfer: if we consider English as L1 and Spanish as L2, positive interlingual transfer may prevent the commission of some spelling errors in words whose orthographic processing is similar in English and Spanish, as in the use of the grapheme <g> to represent the phoneme /g/ (e.g., gato/gang); <l> for /l/ (león/lion); <m> for /m/ (mano/map); <n> for /n/ (nariz/nose); <p> for /p/ (padre/park); <r> for /r/ (rata/rat); <s> for /s/ (sol/sun); and <t> for /t/ (tijeras/task). However, omission errors also need to be considered in this research, as we agree with Llombart-Huesca (2018) that the lack of some misspellings in the corpus could be associated with the methodology used for the study and not with specific spelling difficulties;

- 1.

- Coalescence: the presence of two (or more) different items in English that correspond to only one in Spanish could be the reason for the writing of Spanish words with digraphs only present in English (e.g., <dd> in *buddismo/budismo; <ff> in *officina/oficina; <mm> in *programmador/programador; <ss> in *bessar/besar; <tt> in *attractivo/atractivo; and <zz> in *pizzarra/pizarra). This also happens with the phoneme /f/, only written as <f> (fiesta) in Spanish but as <f> (far), <ff> (affair), and <ph> (photograph) in English;

- 2.

- Underdifferentiation: the English phoneme /Ɵ/ is represented by the digraph <th> in English (e.g., Catholic, thing, and three), which does not exist in Spanish;

- 3.

- Reinterpretation: <h> is always a silent letter in Spanish (e.g., heredero and hora), whereas in English it is either silent (e.g., heir and hour) or represented by the grapheme <h> (e.g., house and harvest). The graphemes /k/ and /w/ can also be silent in English in words like know and write, although this never occurs in Spanish;

- 4.

- Overdifferentiation: the grapheme <ñ> exists in Spanish but not in English. This may be the reason for the writing of <ñ> as <ni> in *unias/uñas and *ninios/niños, as the informants avoid the use of this letter in Spanish words;

- 5.

- Split: the phoneme /b/ is never written as <v> in English, as <v> represents the phoneme /v/ (never /b/) in the language (e.g., vain). On the contrary, in Spanish, there are two graphemes for /b/: <b> and <v> (sometimes also <w>, as in Wenceslao and wagneriano).

4.2. Comparison Between SHL Speakers in Gibraltar and the U.S.

4.2.1. Contrast with Beaudrie’s (2012) Work in the U.S.

The percentage of errors in Spanish (sample A) in Gibraltar is double (20.4%) that of Beaudrie’s sample in the United States (11.7%). If the cognitive–linguistic processing of Spanish orthography is the same in both cases, these differences may respond to other social variables related to the social context of acquisition and use of Spanish.

In Beaudrie’s work, the subcategory “direct English transfer” is only mentioned as an example of “misspellings of words with regular phoneme-to-grapheme relationships” and is limited to cognates/false cognates with similar spellings in English and Spanish. Beaudrie gives *nervous/nerviosa as an example of a cognate and *differente/diferente as a false cognate. However, different and diferente are not false cognates, since they both come from Latin and have the same meaning, so what makes diferente difficult to spell is that the phoneme-to-grapheme relationship in English and Spanish is not the same. This demands different orthographic processing in each language, as the phoneme-to-grapheme relationship is consistent in Spanish (/f/ → <f>), which allows the phonetic spelling of the word, but is inconsistent in English (/f/ → <f>, <ff>, and <ph>). We agree with Whitley (1986: 2) that in these cases, for the comparison and contrast between the two orthographies, contrastive analysis is “one useful tool of linguistics applied to language instruction”.

The transfer from English orthography should, therefore, not be restricted to a specific category of misspellings, as it can affect Beaudrie’s categories (a), (b), and (c):

- misspellings of words with inconsistent or complex phoneme-to-grapheme relationships;

- misspellings of words with regular phoneme-to-grapheme relationships;

- misspellings involving syllable and word fragmentation errors.

According to Beaudrie, interlingual errors in Spanish by the transfer of English are mainly observed in consonant doubling, as in *cellular/celular and *illegal/ilegal. However, for the writing of *illegal, instead of ilegal, the morphological processing of the word is also involved, and consequently, it should be classified in the subcategory (3.3) of our taxonomy, as the insertion of the prefix il- to the base differs in each language. This could be the cause of spelling interferences and not the wrong use of the digraph <ll>. The lack of attention to the participation of morphology in orthographic processing is one of the main limitations of Beaudrie’s work, as exposed by Llombart-Huesca (2018).

Misspellings of this type affecting vowels (Llombart-Huesca, 2019) are also described by Beaudrie, as in *envitados/invitados and *encreíble/increíble, and attributed to the existence of a broader vowel system in English, which forces the learner to establish more complex grapho-phonemic relationships, so “students appear to be transferring English grapheme–phoneme correspondence patterns to Spanish” (Beaudrie, 2012, p. 142). These correspondences sometimes result in positive transfer, but other times, they cause errors through negative transfer. This happens because there are at least three possible categories of transfer between two languages (Whitley, 1986, pp. 3–4):

- Language A has a feature x matched rather closely by x in language B (convergence);

- Language A has a feature x that resembles x in B to some extent but differs in several details;

- Language A has a feature x which B lacks or which can be rendered only in terms of B’s y, which operates according to different principles.

Whitley’s types of transfer (2) and (3) are both manifested in Gibraltarian SHL students, whose interlingual errors are higher (87%) than those inherent to the spelling of Spanish (13%). On the contrary, in Beaudrie’s corpus, interlingual errors (included in the subcategory “direct English transfer”) only represented 2%.

Beaudrie (2012, p. 142) considers, as did Bialystok (2008), that this spelling transfer from English to Spanish is an expected finding since current models of bilingual literacy acquisition claim that “orthographic knowledge and literacy skills acquired in the first language transfer to a second language when the child learns to read and spell in that language.” However, Beaudrie does not mention that this transfer normally takes place in one direction—from the prestige language (A) to the non-prestigious one (B) (Serrano Zapata, 2014; Mariscal, 2022)—because B is more vulnerable to interference, loans, and calques, even if it is the speaker’s mother tongue (Serrano Zapata, 2014, 2024), as in the case of heritage languages (Irizarri, 2016; Mariscal, 2021b).

One of the most frequent misspellings in Beaudrie’s corpus involved the overuse of the grapheme <s> to represent the phoneme /s/ in Spanish, which is explained by Beaudrie as an example of the substitution of <c>/<z> for <s> and labelled as the misspelling of words with inconsistent or complex phoneme-to-grapheme relationships. However, it must be considered that the distinction between regularly/irregularly spelled words depends on the Spanish variety spoken by the informants. For example, for Beaudrie (2012: 139), *facina/fascina is an example of omissions in irregularly spelled words as happens in Latin America (Llombart-Huesca & Zyzik, 2019), the Canary Islands, and some areas of Andalusia, but in Castilian Spanish, this is a regularly spelled word because speakers distinguish between the phonemes /s/ and /θ/, while in Latin America, /s/ may correspond to three different graphemes: <c>, <s>, and <z>.

The aspiration of /s/ at the end of the syllable in Yanito could also be the cause of the incorrect writing of fascinante as *facinante by Gibraltarian informants, who use the phonological route for the phonetic spelling of words learned orally in their dialect. The phonetic spelling of words is the third cause of errors in Gibraltar’s sample (12.4%), followed by misspellings influenced by the inclusion of the oral diatopic features of the Spanish variety spoken in Gibraltar (11%), such as ceceo (/Ɵ/ for /s/), as in *bazos/vasos; seseo (/s/ for /Ɵ/), as in *abrasar/abrazar; yeísmo (the pronunciation of /ʎ/ as /y/), as in *caye/calle, which can also be explained as an error in an irregularly spelled word; the omission of /d/ in an intervocalic position (*deos/dedos); the replacement of /r/ by /l/ (e.g., *purpo/pulpo); the aspiration of /s/ at the end of syllable (e.g., *critiano/cristiano and *delfine/delfines); the realisation of /x/ for silent <h> ([paharos]/pájaros), and /tʃ/ as /ʃ/ ([noshe]/noche); the gemination (or doubling) of /n/ in [canne]/carne); and the loss of final consonants (e.g., *avestrú/avestruz). These examples show that when the Gibraltarian informants need to write vocabulary only stored in the oral form in their mental lexicon, they use their phonological skills for the encoding of such words.

Llombart-Huesca (2018, p. 216) remarks on the influence of phonology on spelling and attributes misspellings caused by phonetic spelling “to an accurate representation of the students’ linguistic variety […] because those are the words in their available input.” In this sense, exposure to the written form of words is critical for the successful development of early literacy in Spanish, and the delay of the explicit teaching of Spanish until middle school in Gibraltar is not contributing to this written exposure, as shown in the high percentage of spelling errors identified in the sample of Gibraltarian SHL speakers.

If a new word is not properly decoded in reading, “it is also not properly encoded in the reader’s mental lexicon, which will have negative consequences for future spelling and reading of this word, as well as for vocabulary expansion” (Llombart-Huesca, 2018, p. 216). This coincides with the results found by Benmamoun et al. (2013) and Pascual and Torres (2022), who point to the existence of smaller lexical knowledge in the heritage language in speakers whose vocabulary was acquired orally in informal contexts, not through print exposure.

Other misspellings found by Beaudrie as examples of the incorrect writing of inconsistent phoneme-to-grapheme relationships in Spanish are associated with the graphemes <h>, <b>/<v>, <r>/<rr>, <g>/<j>, and <y>/<ll>, which are also the most problematic graphemes in the Gibraltar sample. Whereas Beaudrie focuses on this type of error from an intralingual perspective, in Gibraltar, both intra- and interlingual errors are identified in the writing of regularly and irregularly spelled words. For example, misspellings by the interference of English are present in *gajina/gallina, *mochilla/mochila, *ohos/ojos, and *unias/uñas, where the students employ phoneme-to-grapheme relationships that are not correct in Spanish, so they transfer their spelling abilities in one language to the other, as in the research conducted by Zutell and Allen (1988).

As Beaudrie argues, the teaching of accent marks in Spanish needs to be reinforced, as this is the subcategory with the largest number of misspellings both in Beaudrie’s work (71.1%) and Gibraltar (31.7%), and explicit instruction on accent marks usage could be beneficial (Fernández Parera & Lynch, 2021).

4.2.2. Contrast with Belpoliti and Bermejo’s (2019) Work in the U.S.

As shown in Table 4, the percentage of errors in Spanish is double (20.4%) in Gibraltar (sample A) that of Beaudrie’s sample (11.7%) in the U.S., but the latter is similar to Belpoliti and Bermejo’s results (15.9%), and the main spelling difficulty (errors with written accent marks) coincides in the three samples.

Table 4.

Contrast between the results in Spanish in Gibraltar and the U.S.

Most of the errors in Belpoliti and Bermejo’s corpus were intralingual (92.7%), as in *asta/hasta, and only 7.3% were interlingual, as in *technologico/tecnológico and *telephono/teléfono, so this sample of SHL learners in the U.S. had more difficulty in managing the standard Spanish writing system, as manifested in the infrequent occurrence of interlingual errors, than in controlling the transfer from the English language. The percentage of interlingual misspellings is similar in Beaudrie’s (2012) research in the U.S. (2%) but not in Gibraltar, where the number of errors due to the interference of English is much higher (87%) than in the U.S., which demands more inhibitory control of transfer.

With respect to intralingual misspellings, we agree with Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019: 26) that Spanish “employs a shallow orthography with a relatively high level of consistency,” but as explained before, there is not always a one-to-one relationship between graphemes and phonemes in this language, which also depends on the oral variety of Spanish. As Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) studied SHL learners in the United States, the most problematic issue was the representation of the phoneme /s/, as in Beaudrie (2012) and Llombart-Huesca (2018), because seseo is characteristic of Spanish in the U.S. context.

Apart from the phoneme /s/, Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) found misspellings due to incorrect phoneme-to-grapheme relationships in the writing of <h> (*aber/haber and *habierto/abierto), <r>/<rr> (*mirrar/mirar), <g>/<j> (*hente/gente and *pajina/página), <b>/<v> (*govierno/gobierno), <qu> (*quando/cuando), and <y> (*major/mayor), as well as the omission of <u> in the digraph <qu> (*qien/quien).

Misspellings were not classified as intralingual/interlingual errors, thus presenting one of the main limitations of this work. Another limitation is the inclusion of regularly and irregularly spelled words in the same category since it does not favour the analysis of misspellings from a cognitive–linguistic approach, as they are all quantified as a whole, without making differences in the way they are processed in the brain, that is, whether through the visual or phonological routes.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study confirm the existence of a higher number of interlingual misspellings in Spanish in Gibraltar in comparison with the samples studied by Beaudrie (2012) and Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) in the U.S. Despite the similarities inherent to the cognitive–linguistic processing of Spanish orthography by SHL speakers in the two contexts, the Gibraltar interactional context of language contact may be conditioning interference suppression, according to the adaptive control hypothesis (Green & Abutalebi, 2013) and, consequently, the appearance of more interlingual spelling errors. The percentage of these errors is 87% in Gibraltar versus 2% (Beaudrie, 2012) and 7.3% (Belpoliti & Bermejo, 2019) in the U.S., with the transfer taking place from English to Spanish in the Gibraltarian sample but not vice versa.

Apart from this, the misspellings present in the Gibraltarian corpus coincide, in general terms, with those identified by Beaudrie (2012) and Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) in the U.S., although the percentage of errors in Gibraltar is higher (20.4%) than in Beaudrie’s (11.7%) and Belpoliti and Bermejo’s (15.9%) works. Accent marks were identified as the most common source of spelling errors both in Gibraltar and the U.S., a testament to the necessity for the more explicit teaching of the spelling rules that regulate the use of accent marks in Spanish in both contexts.

When conducting research on SHL speakers, it is necessary to take into consideration that the particularities of the phonetic features of the Spanish variety represent specific difficulties when learning to spell. For example, misspellings due to seseo were found by Beaudrie (2012) and Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019) in the U.S. However, in Gibraltar, not only seseo (*tisa/tiza) was reflected in the students’ phonetic spelling but also other diatopic features of Yanito, such as ceceo (*turqueza/turquesa), the replacement of /l/ for /r/ (*ombrigo/ombligo), the omission of /d/ in intervocalic position (*batio/batido), the aspiration of /s/ at the end of syllable (*burdeo/burdeos and *muculo/músculo), and the loss of final consonants (*ordenadó/ordenador).

Although Beaudrie’s (2012) and Belpoliti and Bermejo’s (2019) error analyses definitely contribute to research on SHL misspellings, and their division into categories and subcategories may be used as a reference for similar studies in the field, their explanation of spelling errors responds more to a quantitative approach than to the identification of the linguistic and cognitive factors that intervene in their appearance. This is what James (1998: 9) calls “collecting butterflies”, that is, classifying the errors depending on their superficial structure instead of identifying their psycholinguistic nature. For example, Beaudrie differentiates between consistent and inconsistent phoneme-to-grapheme relationships, but insufficient attention is paid to why those misspellings result in spelling difficulties, and Belpoliti and Bermejo limit this distinction to one category, where all the errors caused by incorrect phoneme-to-grapheme correspondences in Spanish are mixed.

Furthermore, both works focus on intralingual errors, and neither finds anything of special interest regarding the participation of spelling transfer from English in the informants’ errors, which is very frequent in Gibraltar. Another problem lies in the lack of data regarding the mean and the standard deviation of the spelling errors in their studies, which prevents our determination of whether spelling difficulties affected the whole sample or only specific students. In Gibraltar, the mean of spelling errors was 46.7, with a standard deviation of 15.3, which indicates some individual variation among the participants. The results demand more explicit teaching of Spanish orthography in school and increased exposure to materials in this language so that learners can store the written form of words in their mental lexicon, especially the ones with inconsistent phoneme-to-grapheme relationships and those that could lead to interferences.

Another limitation of these two error analyses is that SHL learners’ misspellings are compared to those previously found in monolingual speakers of Spanish, probably because little attention has been paid to bilingual spelling, in general, and to heritage speakers’ misspellings, in particular. It is also essential to keep in mind that the absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence. For example, we agree with Llombart-Huesca (2018) that the fact that the informants’ productions do not include errors in the use of dieresis cannot be explained simply as the lack of spelling difficulties in this issue as it could be linked to the infrequent writing of words with dieresis (e.g., pingüino) in the students’ essays, as well as the overuse of frequent words because of their limited vocabulary in Spanish. This is also a limitation of the current research since the corpus is only formed by commission errors, but it is not possible to know which omission errors were avoided by the informants in the lexical availability tests.

To provide a broader picture of how written words are encoded and decoded, an error analysis must pay attention not only to the number of misspellings but also to individual and social factors. Among individual ones, spelling success may depend on the learners’ vocabulary, phonological awareness, morphological competence, level of exposure to print, and memory, as spelling is “a process of conceptual development” (Newlands, 2011, p. 531). In this sense, spelling activities of contrastive analysis can help foster the learners’ metalinguistic knowledge of both languages and their metacognitive skills.

Some of the social variables that play an important role in the characterisation of heritage speakers include their demographic characteristics, language status, access to literacy in formal schooling, the origin of their parents, the diatopic variations in Spanish, and the demands of real-world interactional contexts (single, dual, or in the form of dense code-switching). Regarding the latter, more research is needed to study the role of interactional context in language control and interference suppression and how both parameters participate in SHL speakers’ orthographic processing. These bilingual speakers should be assessed in their two languages by employing both behavioural and neuroimaging methods.

For future research, the results from Gibraltar, an under-researched population in heritage language studies, need to be compared with the spelling errors of non-heritage speakers from the monolingual population of this British territory and with informants of the same age range, as in Beaudrie (2012) and Belpoliti and Bermejo (2019), because the age difference between the informants of Gibraltar and those of the U.S., as well as the type of tasks, could have influenced the higher number of errors in Gibraltar.

Funding

The funding of English Editing was requested to Vicerrectorado de Investigación y Transferencia, Cádiz University (Plan Propio de estímulo y apoyo a la Investigación y Transferencia 2025–2027, reference number PB2025-019).

Informed Consent Statement

Neither Institutional Review Board Statement nor Informed Consent Statement was necessary as the informants were not surveyed for the current research. Their misspellings were taken from the items already stored in the Dispolex dataset by the members of the research project “Lenguas en contacto y disponibilidad léxica: la situación lingüística e intercultural de Ceuta y Gibraltar” (BFF2000–0511)Authorisation to access the dataset was given to us by the PI of the project (Dr. Casas Gómez) after signing an ethical commitment for the appropriate use of the data.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analyses, interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | According to Loureda Lamas et al. (2023, pp. 28–29), “heritage speakers are those who acquire the language of their predecessors in two ways: early on, via communication at home and in immediate social circles, providing theman oral competence nearly on par with that of native speakers; and later, via educational contexts in which they acquire written skills and their initial linguistic input is reinforced.” |

| 2 | Green and Abutalebi (2013, p. 516) define interactional contexts as “the recurrent pattern of conversational exchanges within a community of speakers.” |

| 3 | In the U.K., a state comprehensive school is a non-selective secondary school funded by the government, which provides free education to children in the local area. |

| 4 | Some researchers describe a progressive decrease in the use of Spanish among the youngest generations (Chevasco, 2019), as the result of language shift “from a Spanish-speaking population to a policy of English-Only” (Rodríguez García & Goria, 2023, p. 116). |

References

- Al-Sobhi, B. (2019). The nitty-gritty of language learners’ errors—Contrastive analysis, error analysis and interlanguage. International Journal of Education & Literacy Studies, 7(3), 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K. (2011). What is orthographic knowledge? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 592–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, R. H., Silliman, E., Danzak, R., & Wilkinson, L. (2015). Bilingual spelling patterns in middle school: It is more than transfer. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 18(1), 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, S. M. (2012). A corpus-based study on the misspellings of Spanish heritage learners and their implications for teaching. Linguistics and Education, 23, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudrie, S. M. (2017). The teaching and learning of spelling in the Spanish heritage language classroom: Mastering written accent marks. Hispania, 100(4), 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belpoliti, F., & Bermejo, E. (2019). Spanish heritage learners’ emerging literacy: Empirical research and classroom practice [e-book]. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Benmamoun, E., Montrul, S., & Polinsky, M. (2013). Heritage languages and their speakers: Opportunities and challenges for linguistics. Theoretical Linguistics, 39(3–4), 129–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. (2001). Bilingualism in development: Language, literacy, and cognition. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. (2004). The impact of bilingualism on language and literacy development. In T. K. Bhatia, & W. C. Ritchie (Eds.), The handbook of bilingualism (pp. 577–601). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, E. (2008). Acquisition of literacy in bilingual children: A framework for research. Language Learning, 52(1), 159–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E., Craik, F., & Luk, G. (2012). Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciencies, 16(4), 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bialystok, E., Peets, K. F., & Moreno, S. (2014). Producing bilinguals through immersion education: Development of metalinguistic awareness. Applied Psycholinguistics, 35, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H. D. (2000). Principles of language learning and teaching. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Burgo, C. (2015). Current approaches to orthography instruction for Spanish heritage learners: An analysis of intermediate and advanced textbooks. Normas, 5, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, M., & Kagan, O. (2018). Heritage language education: A proposal for the next 50 years. Foreign Language Annals, 51(1), 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetail, F. (2024). Reading books: The positive impact of print exposure on written word recognition. Cognition, 251, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevasco, D. (2019). Contemporary bilingualism. Llanito and language policy in Gibraltar: A study. Editorial UCA. [Google Scholar]

- Coltheart, M. (1978). Lexical access in simple reading tasks. In G. Underwood (Ed.), Strategies of information processing (pp. 151–216). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cunnigham, A., & Stanovich, K. (1993). Children’s literacy environments and early word recognition subskills. Reading and Writing, 5(2), 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daffern, T., Mackenzie, N., & Hemmings, B. (2015). The development of a spelling assessment tool informed by triple word form theory. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 38(2), 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, C. A., & Valdés Kroff, J. R. (2017). Cross-linguistic orthographic effects in late Spanish/English bilinguals. Languages, 2(4), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T., & Van Heuven, W. J. (2002). The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 5(3), 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominiek, S. (2019). Orthography and cognition. In J. O. Östman, & J. Verschueren (Eds.), Handbook of pragmatics online (pp. 149–180). Handbook of Pragmatics 22. John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duursma, E., Romero-Contreras, S., Szuber, A., Proctor, P., Snow, C., August, D., & Calderón, M. (2007). The role of home literacy and language environment on bilinguals’ English and Spanish vocabulary development. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28(1), 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errico, E. (2015). Hace dos años para atrás que fui a Egipto… sobre algunas semejanzas entre el español de Gibraltar o yanito y el español de estados unidos. Confluenze, 7(2), 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Parera, A., & Lynch, A. (2021). The effects of explicit instruction on written accent mark usage in basic and intermediate Spanish heritage language courses. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching, 8(1), 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Caba, M. (2022). Estudio sociolingüístico del uso del español y el inglés en el code-switching escrito de Gibraltar. Études Romanes de Brno, 43(1), 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goria, E. (2021). The road to fusion: The evolution of bilingual speech across three generations of speakers in Gibraltar. International Journal of Bilingualism, 25(2), 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Gibraltar. (2025). Education system. Available online: https://www.gibraltar.gov.gi/education/education-system (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Green, D. W., & Abutalebi, J. (2013). Language control in bilinguals: The adaptive control hypothesis. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 25(5), 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarri, P. (2016). Spanish as a heritage language in the Netherlands: A cognitive linguistic exploration [Doctoral thesis, Radboud Universiteit]. Available online: https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/159312/159312.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- James, C. (1998). Error in language learning and use: Exploring error analysis. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, L., & Frost, R. (1992). The reading process is different for different orthographies: The orthographic depth hypothesis. Advances in Psychology, 94, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushanskaya, M., & Marian, V. (2009). Bilingualism reduces native-language interference during novel-word learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35(3), 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerns, J. G., Cohen, J. D., MacDonald, A. W., Cho, R. Y., Stenger, V. A., Aizenstein, H., & Carter, C. S. (2004). Anterior cingulate conflict monitoring and adjustments in control. Science, 303(5660), 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpatrick, D. A. (2015). Assessing, preventing, and overcoming reading difficulties. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, G., & O’Brien, B. A. (2020). Examining language switching and cognitive control through the adaptive control hypothesis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, D. (2006). Yanito. In K. Brown (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language & linguistics, 13 (pp. 724–725). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Levey, D. (2015). Yanito: Variedad, híbrido y Spanglish. In S. Betti, & D. Jorques (Eds.), Visiones europeas del Spanglish (pp. 75–85). Uno y Cero. [Google Scholar]

- Llombart-Huesca, A. (2018). Understanding the spelling errors of Spanish heritage language learners. Hispania, 101(2), 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llombart-Huesca, A. (2019). Phonological awareness and spelling of Spanish vowels in Spanish heritage language learners. Hispanic Studies Review, 4(1), 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Llombart-Huesca, A. (2024). Spelling in Spanish heritage language education. Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Llombart-Huesca, A., & Zyzik, E. (2019). Linguistic factors and the spelling ability of Spanish heritage language leaners. Frontiers in Education, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureda Lamas, O., Moreno Fernández, F., & Álvarez Mella, H. (2023). Spanish as a heritage language in Europe: A demolinguistic perspective. Journal of World Languages, 9(1), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, S. (2024). In defence of Llanito: Gibraltar in a state of linguistic transition. The Round Table, 113(3), 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariscal, A. (2019). ¿Puede hablarse realmente de una lengua extranjera en Gibraltar? In B. Heinsch, A. C. Lahuerta, M. N. Rodríguez, & A. J. Jiménez (Eds.), Investigación en multilingüismo: Innovación y nuevos retos (pp. 201–213). Universidad de Oviedo. [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal, A. (2021a). Categorización de los errores ortográficos en zonas de contacto lingüístico entre inglés y español (Vol. 159). Studien zur romanischen Sprachwissenschaft und interkulturellen Kommunikation. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Mariscal, A. (2021b). Presencia de rasgos lingüísticos característicos de las lenguas de herencia en las producciones escritas de hablantes bilingües de Gibraltar. Revista Nebrija de Lingüística Aplicada a la Enseñanza de las Lenguas, 15(30), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariscal, A. (2022). Bilingüismo y contacto lingüístico en la comunidad de Gibraltar a partir del análisis contrastivo y de errores (Vol. 179). Studien zur romanischen Sprachwissenschaft und interkulturellen Kommunikation. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, M. G. (1992). Analysis of code-switching in Gibraltar [Doctoral Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona]. Available online: http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/4918 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Newlands, M. (2011). Intentional spelling: Seven steps to eliminate guessing. The Reading Teacher, 64(7), 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F., & Schneider, W. (2013). Home literacy environment and the beginning of reading and spelling. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(1), 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSW Department of Education and Training. (2007). Writing and spelling strategies: Assisting students who have additional learning support needs. Disability Programs Directorate: Learning Assistance Program. Available online: https://cer.schools.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/doe/sws/schools/c/cer/localcontent/writingandspellingstrategies.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Pascual, D., & Torres, J. (Eds.). (2022). Aproximaciones al estudio del español como lengua de herencia [e-book]. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, B. (2007). Social factors in childhood bilingualism in the United States. Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, H. E., Peters, J. L., & Crewther, S. G. (2023). A role for visual memory in vocabulary development: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 33(4), 803–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, D., Stainthorp, R., & Stuart, M. (2014). Deficits in orthographic knowledge in children poor at rapid automatized naming (RAN) tasks? Scientific Studies of Reading, 18(3), 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez García, M., & Goria, E. (2023). Backflagging revisited: A case study on bueno in English-Spanish bilingual speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 215, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said-Mohand, A. (2011). The teaching of Spanish as a heritage language: Overview of what we need to know as educators. Porta Linguarum, 16, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper Padilla, J. A. (2003). El ‘proyecto panhispánico’ de disponibilidad léxica: Logros y estado actual». In VII Jornadas de lingüística (pp. 193–225). M. Casas (Dir.), & C. Varo (Coord.). Universidad de Cádiz. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Saus Laserna, M. (2019). Centros de interés y capacidad asociativa de las palabras (Vol. 56). Lingüística. Universidad de Sevilla. [Google Scholar]

- Schröter, P., & Schroeder, S. (2016). Orthographic processing in balanced bilingual children: Cross-language evidence from cognates and false friends. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 141, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano Zapata, M. (2014). Disponibilidad léxica en la provincia de Lleida: Estudio comparado de dos lenguas en contacto [Doctoral thesis, Universitat de Lleida]. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/285008 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Serrano Zapata, M. (2024). El castellano y el catalán en contacto: Efectos sobre el vocabulario. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Corvalán, C. (2004). Spanish in the southwest. In E. Finegan, & J. Rickford (Eds.), Language in the USA: Themes for the twenty-first century (pp. 205–229). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (1989). Exposure to print and orthographic processing. Reading Research Quarterly, 24(4), 402–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun-Alperin, M. K., & Wang, M. (2011). Cross-language transfer of phonological and orthographic processing skills from Spanish L1 to English L2. Reading and Writing, 24, 591–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tainturier, M. J., & Rapp, B. (2001). The spelling process. In B. Rapp (Ed.), The Handbook of cognitive neuropsychology: What deficits reveal about the human mind (pp. 263–289). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torgensen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (1994). Longitudinal studies of phonological processing and reading. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27(5), 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.K. Government. (2013). The national curriculum in England: Framework document. U.K. Department for Education. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425601/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Valdés, G. (1997). The Teaching of Spanish to Bilingual Spanish-Speaking Students: Outstanding Issues and Unanswered Questions. In M. Colombi, & F. Alarcón (Eds.), La enseñanza del español a hispanohablantes: Praxis y teoría (pp. 8–44). Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heuven, W. J., Dijkstra, T., & Grainger, J. (1998). Orthographic neighborhood effects in bilingual word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language, 39(3), 458–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, M. S. (1986). Spanish/English contrasts: A course in hispanic linguistics. Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, J., & Goswami, U. (2005). Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia, and skilled reading across languages: A psycholinguistic grain size theory. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zutell, J., & Allen, V. (1988). The English spelling strategies of Spanish-speaking bilingual children. TESOL Quarterly, 22(2), 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).