Abstract

One aspect of clausal embedding that has not received any specific attention in the literature is the question of whether and how derivational morphology may affect clausal selection properties of the respective bases. In this paper, I will focus on the role of German preverbs for clausal embedding. I will show that any parameter of clausal embedding can be affected by a preverb, though sometimes in a non-compositional way. Preverbs may affect presuppositions and entailments of their base verb, their selectional behavior with respect to clause types, their status as control or raising predicate and their potential for restructuring. Furthermore, preverbs may license or block neg-raising. The first part of the paper is dedicated to the demonstration of these effects with no specific preverb in mind. The second part discusses three specific preverb patterns with zu- ‘to’, ein- ‘in’ and er-, showing their specific clausal complementation properties. Preverbs influence clausal complementation by their impact on the argument structure/realization (in the case of control and restructuring) and on the lexical aspect of the base (in the case of certain interrogative complements and neg-raising).

Keywords:

preverb; particle verb; prefix verb; German; clausal selection; clause type; control; raising; neg-raising 1. Introduction

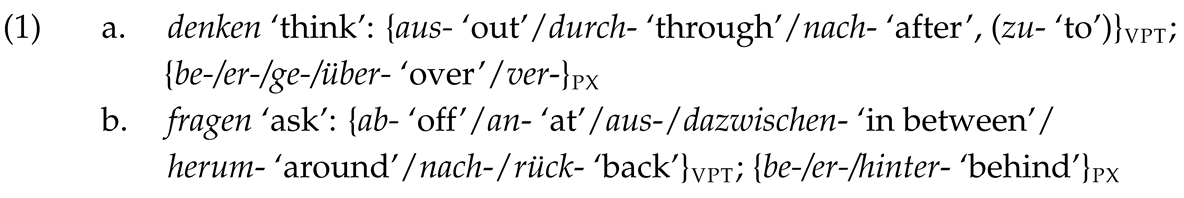

Two-thirds of German clause-embedding verbs (CEVs) are morphologically complex, involving verbal particles (vpt) and prefixes (px): The ZAS database on German clause-embedding predicates (Stiebels et al., 2024) lists 454 simple verbs (further 132 denominal simple verbs), 584 particle verbs and 483 prefix verbs.1 Whereas attitude predicates such as glauben ‘believe’ or wissen ‘know’ block any preverb derivation and verbs such as hoffen ‘hope’ and wollen ‘want’ are severely restricted in their combinatorial potential (attested derivatives: er-hoffen ‘hope for’; (darauf) hinaus-wollen ‘get at’), other CEVs can combine with a larger subset of the preverbs, for instance denken ‘think’ and fragen ‘ask’2:

The various derivatives of denken and fragen differ in their meaning, their argument structure and realization (see Section 2.1), and the selected clause types (see Section 3.2). In general, German complex verbs vary in their degree of idiomaticity, which is also the case for the derivatives of denken: whereas ge-denken ‘commemorate’ and ver-denken ‘hold sth against sb’ are highly idiomatic, durch-denken ‘think through’ is more or less transparent.3 The derivatives of fragen retain the inquisitive nature of their base but refer to different situations of inquiry/interrogation/questioning.

So far, the research on German preverbs has focused on their uses with non-CEVs. The potential role of the preverb for the clausal selection properties of CEVs has not been addressed in any substantial way, i.e., there is no systematic study investigating whether the preverb may affect parameters of clausal embedding (e.g., selected clause types, restructuring or control properties of CEVs that select infinitival complements). It is the goal of this paper to provide a first answer to the potential role of preverbs for clausal selection. A look across all preverbs used in complex CEVs of the ZAS database shows that preverbs may affect any parameter of clausal embedding in principle. Furthermore, specific preverb patterns come with a specific clausal selection profile, which will be demonstrated for three selected preverb patterns.

The research gap concerning the role of preverbs for clausal selection possibly results from various factors to be observed in the complex CEVs of the ZAS database: (i) many complex CEVs are more or less lexicalized and do not allow for a compositional analysis (like the cases mentioned above); (ii) many CEVs do not participate in the productive preverb patterns found in non-CEVs—at least in their clause-embedding uses; (iii) there is no obvious preverb pattern that stands out as having a systematic effect on clausal embedding. However, it will be shown in the following that any parameter of clausal embedding can be affected by a preverb.

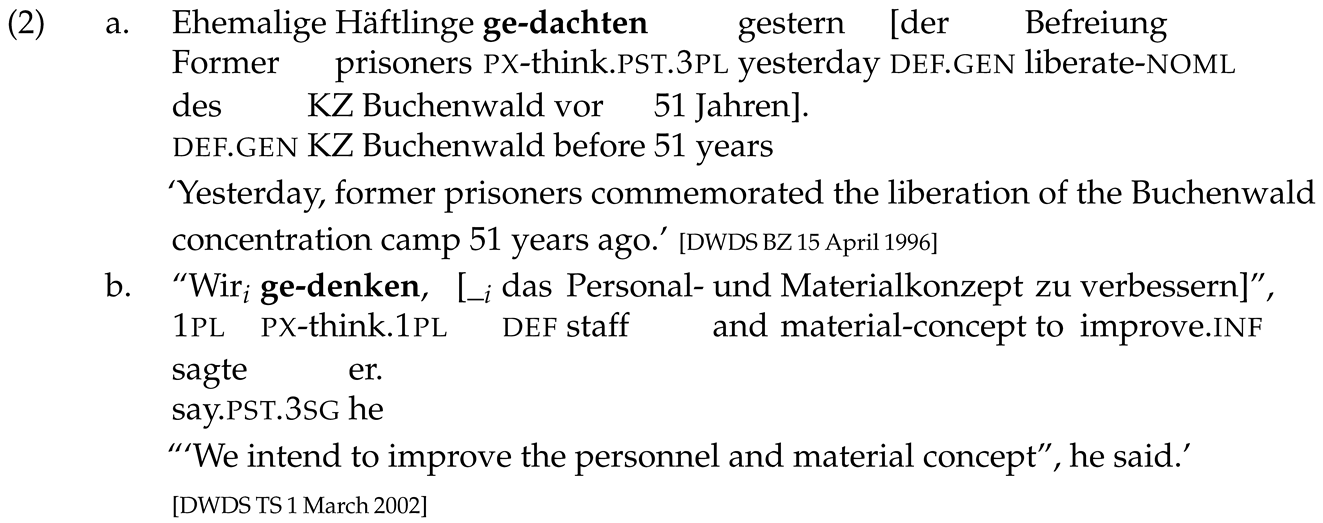

Another aspect that complicates the picture is the notorious polysemy of preverbs. All analyses that aim for a compositional analysis of transparent complex German verbs end up postulating separate entries for each preverb under study (see, for instance, Haselbach, 2011; Stiebels, 1996; Witt, 1998). These distinct entries reflect differences in the interpretation (and sometimes presuppositions) of the preverb and/or in the effects on the argument structure/realization and event structure of the base verb. There are also many instances of polysemous complex CEVs. For instance, ge-denken has the less frequent reading ‘intend’ besides the reading ‘commemorate’. The latter is mainly attested with nominalized complements in the genitive as in (2a), whereas the former selects infinitival complements as in (2b).4 This reading-dependent pattern of argument structure/realization and preferred selected clause types is typical for the majority of polysemous CEVs.

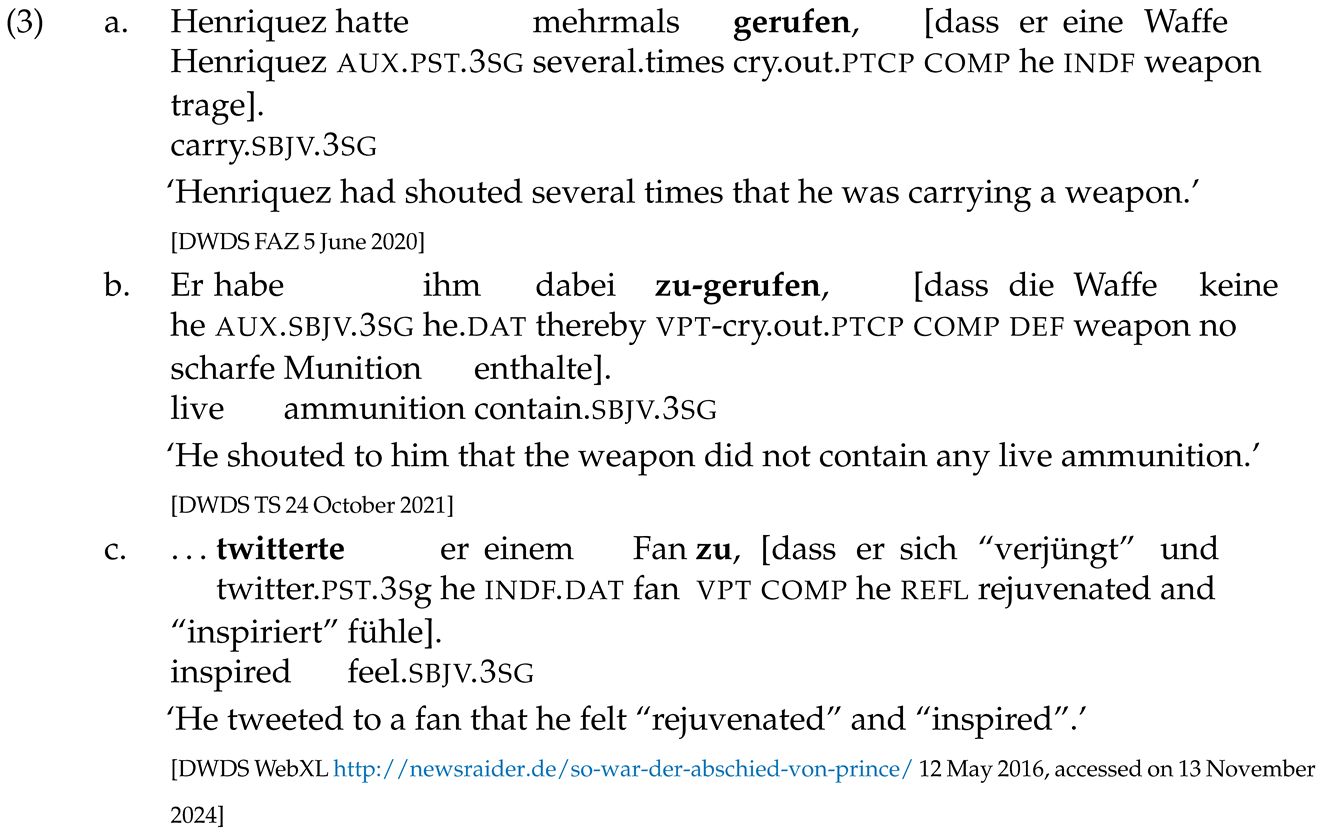

The preverb subpatterns found in CEVs usually involve only a small set of verbs—unlike the very productive patterns attested in non-CEVs (e.g., the prefix er- in its integration of a possessive relation: sich etwas er-tanzen ‘get sth by dancing’; the prefix ver- in its integration of a decremental object: ver-spielen ‘gamble away’; the other use of ver- in its specification of a deviant execution of an action: sich ver-spielen ‘play wrongly’; see Stiebels, 1996 for details). An example for a transparent CEV pattern is found with the verbal particle zu- ‘to’, which may be combined with verbs of speech/communication and certain sound emission verbs and conveys the transfer of information. The particle introduces an addressee argument in the dative; the derived verbs exhibit a clausal argument in addition. It is not decidable whether the clausal argument should be taken as an optional argument of the base verb or as being added by the particle zu-. In the former case, the optional clausal argument would be turned into an obligatory argument. Example (3a) illustrates the base verb rufen ‘cry out, shout’ and (3b) the derivative zu-rufen. The neologism twittern ‘twitter, tweet’, which can be used as a verb of communication, is also attested in this pattern (see (3c)). Note that zu-rufen (like other instances of this pattern) is not confined to finite clauses with the complementizer dass; it only excludes nominalized clausal complements (see Section 4.1).

One may raise the objection that the idiomaticity and the low productivity of preverbs in CEVs cannot reveal anything interesting for our understanding of clausal selection properties. Although one cannot account for the clause-embedding properties of idiomatic/lexicalized CEVs by looking at the meaning of its components, the meaning of an idiomatic CEV usually reflects its membership in a certain semantic class of verbs, which may exhibit specific clause-embedding properties. A case in point would be auf-hören ‘stop’ (lit. up-hear), which falls into the class of aspectual/phasal verbs, thus licensing its behavior as a raising and restructuring verb. A diachronic study of selected idiomatic verbs is beyond the scope of this paper (see, for instance, Jędrzejowski, 2015 for a diachronic study of certain subject raising verbs in German).

The paper is organized as follows: I will first address some general properties of German preverbs in Section 2. In Section 3, I will focus on the clausal selection properties that may be changed by a preverb, discussing both semantic (presuppositions and entailments, neg-raising) as well as syntactic aspects (clause type, raising, control, restructuring). Then, Section 4 will present three specific preverb patterns in more detail: The first pattern (certain particle verbs with zu-) represents one of the most transparent patterns involving verbs of communication. The second pattern (certain particle verbs with ein-) derives a class of CEVs similar to ‘convince’, though not being semantically equivalent in all respects. The third pattern (a small class of resultative verbs with the prefix er-) is chosen for illustration because it shows a subtle shift in the interpretation of interrogative complements.

Before I turn to the next section, I would like to briefly comment on my use of “productive/(semi-)productive” patterns and “niche” patterns in this paper. Productivity is a much debated concept (see, for instance, the overviews by Bauer, 2001, 2005; Dal & Namer, 2016). I will use “productive” in a qualitative sense (and not in a quantitative sense), making use of the notion “availability” (Carstairs-McCarthy’s (1992) translation of Corbin’s (1987) concept “disponibilité”). Productivity in derivational morphology is the extent to which a certain derivational process may be used for the creation of new words in a compositional manner5. Derivational morphemes differ in their application domain (the restrictions imposed on their bases). Many of the preverbs considered in this paper have a rather restricted application domain. I will use the label “niche” for preverb patterns that are restricted to a semantically narrowly defined class of base verbs (see Rainer, 2018 for a discussion of the concept “niche”).

2. General Properties of German Preverbs

Prefix and particle verbs differ in their morphosyntactic properties (with respect to the morphosyntactic separation of preverb and base verb and possible combinations with other preverbs; see Stiebels & Wunderlich, 1994), which, however, does not show any correlation with respect to clausal embedding. Properties that may affect clausal complementation mostly concern changes of argument structure and argument realization, and changes in lexical aspect induced by the preverb.

2.1. Argument Structure and Argument Realization

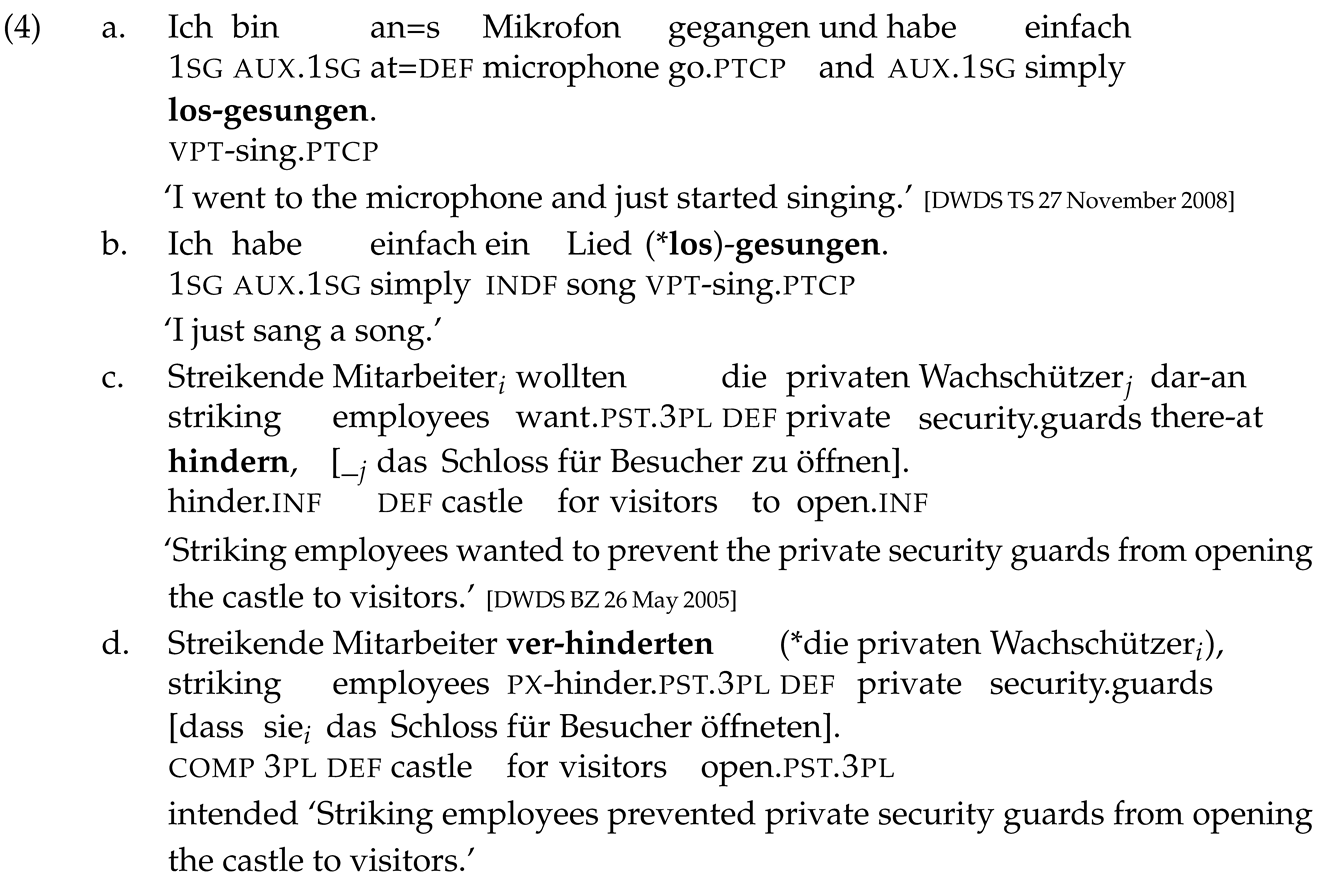

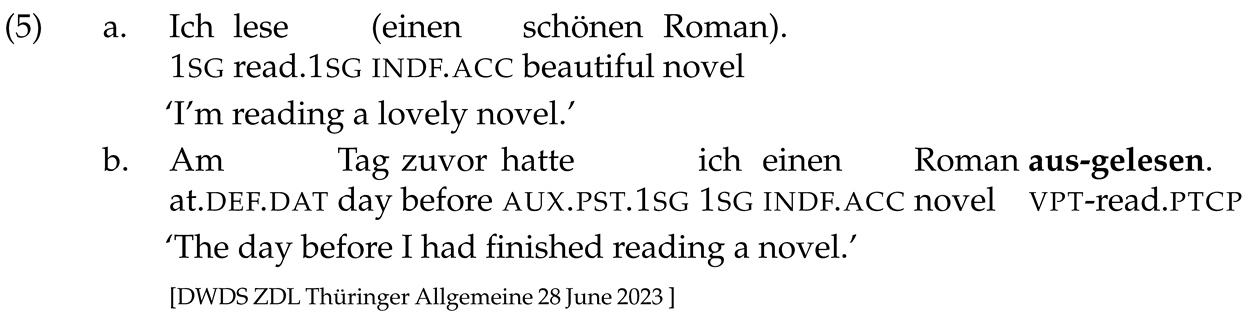

Many preverbs affect the argument structure of the base verb (McIntyre, 2007; Stiebels, 1996): (i) they may add new arguments, as evidenced by the examples in (2); (ii) they may block the realization of arguments, as in (4a/d); or (iii) they may turn optional arguments into obligatory arguments, as in (5b). The internal argument of singen ‘sing’ is blocked by the aspectual verbal particle los-, which refers to the initiation of an action (4a/b). Similarly, the prefix ver- blocks the realization of the internal argument of hindern ‘hinder’ in (4d).

The resulting obligatoriness of the internal argument in (5b) is very typical of preverbs that quantify over the event denoted by the base verb and its object (see Rossdeutscher, 2012 for the hidden quantificational force of aus- ‘out’). Example (5a) is atelic without the direct object and may allow both for a telic or atelic interpretation in combination with the direct object—depending on the temporal context. Example (5b) is necessarily telic.

Preverb patterns deriving the same argument structure may still differ in their argument realization/case pattern. Usually, preverb patterns come with a specific case pattern. In their transparent/productive uses, preverbs mostly derive verbs with canonical case (nom/acc with transitive and nom/acc/dat with ditransitive verbs); however, there are also patterns in which an oblique case is used. Table 1 illustrates the variation in case patterns with the derivatives of fragen ‘ask’; I follow the notation of the ZAS database. The order of the case markers in the third column reflects the argument hierarchy with the case of the lowest argument in the leftmost position and the case of the highest argument in the rightmost position. Oblique clausal arguments are marked as obl (with the specification of the concrete prepositional proform, e.g., nach for da-nach; ‘prof’ refers to the sentential proform es ‘it’; see Schwabe et al., 2016 for an overview on sentential proforms). Oblique individual arguments are marked as PP. Round brackets indicate the optionality of the argument. zero is used if the CEV does not assign any case to the clausal argument.6 In many cases, the oblique marking of the clausal argument (with a sentential proform) is optional.

Table 1.

Argument realization of preverb derivatives of fragen ‘ask’.

As Table 1 demonstrates, the derivatives of fragen differ in the case of the clausal argument (the leftmost case): it may be caseless (zero; e.g., with herum-/nach-fragen), it may receive structural accusative (e.g., with er-fragen) or it may be marked obliquely (e.g., with an-/aus-fragen). The addressee of the inquisitive speech act may be marked with the accusative (e.g., with be-fragen or aus-fragen) or with oblique case (e.g., with an-fragen, herum-fragen or nach-fragen).

2.2. Lexical Aspect

Since German does not exhibit a grammatical/viewpoint aspect, the aspectual contribution of German preverbs is restricted to lexical aspect/aktionsart. Many preverbs, especially those with a resultative meaning, derive telic verbs. This applies to cases like in (5b,6a), but also to the integration of a possessive relation induced by er- as in (6b). Replacing the temporal specification with a time-frame adverbial (see (6c)) demonstrates the telic nature of this er- pattern.

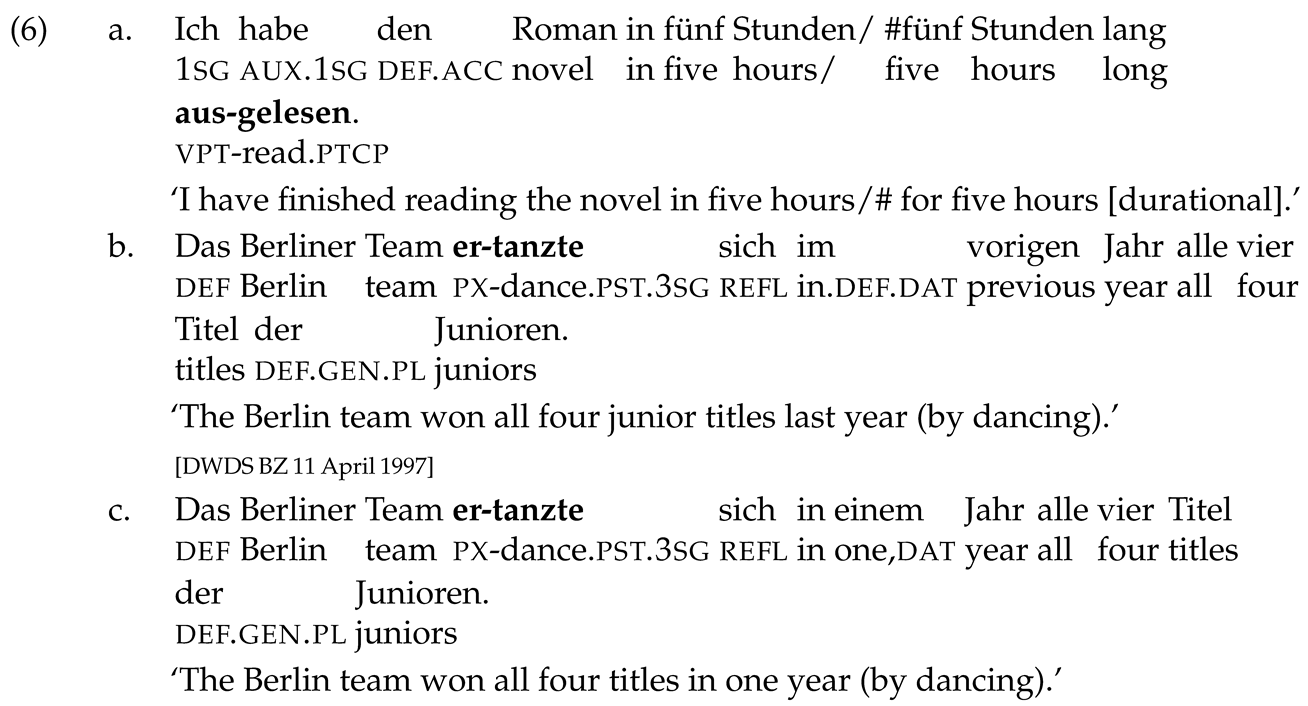

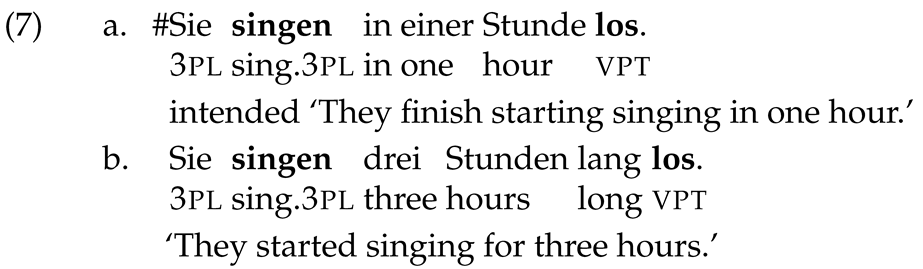

However, not all preverb patterns derive telic verbs. The los-pattern in (4a) is incompatible with time-frame adverbials (as specification of the duration of the event; see (7a)) and yields an iterative interpretation with durational adverbs (see (7b)); this is expected since the preverb picks out the initial phase of the activity denoted by the base verb. Example (7a) is acceptable under the interpretation that the time-frame adverbial specifies the time span after which singing starts.

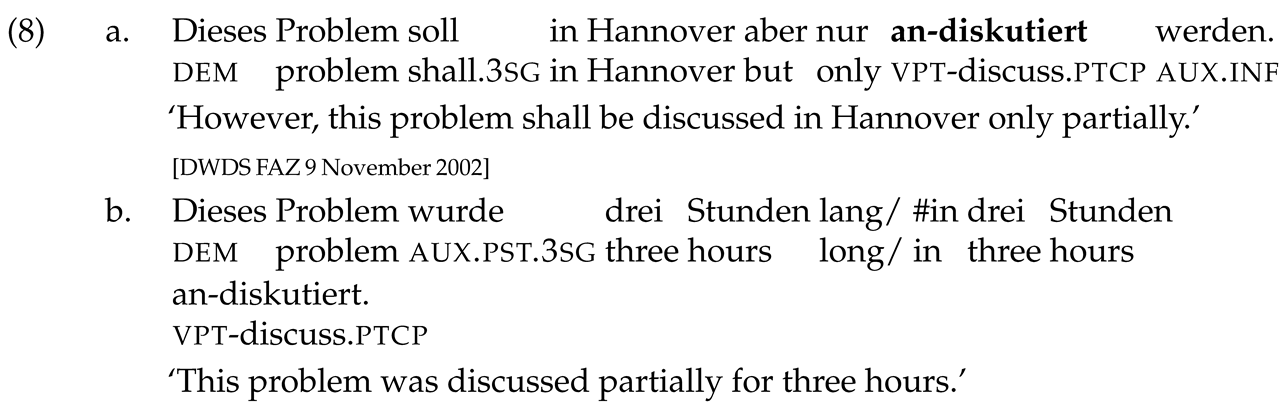

The third case for illustration is the use of the verbal particle an- as a partiality marker (Stiebels, 1996). This pattern signals that the event (was) terminated before its natural or expected culmination point. The verb diskutieren ‘discuss’ is an activity verb. The derivative an-diskutieren ‘discuss partially’ refers to a situation where only some but not all issues of the relevant topic are discussed; see (8a). The pattern is compatible with a durational adverb in an iterative reading as in (8b); the time-frame adverbial is not licit because there is no clear point in time at which a partial discussion of a problem has reached its expected culmination point.

2.3. Base Verbs

The various aspectual classes of verbs differ in their combinatorial potential with respect to preverbs. Preverb derivation is most productive with activity verbs or verbs that allow for an interpretation as activity verb (Stiebels, 1996), which is due to the fact that these verbs are dynamic and allow for a modification that specifies a culmination point, which is often provided by the preverb. Stative verbs, especially verbs denoting “Kimian states”, i.e., non-eventive states (Maienborn, 2003, 2008), block preverb derivation in most cases. Stative verbs denoting “Davidsonian states” (e.g., sitzen ‘sit’, liegen ‘lie’) are attested with preverbs. Achievement verbs are likewise very restricted in their combination with preverbs.

Preverbs play a major role in German deadjectival verbs because simple deadjectival verbs are small in number (e.g., reif-en ‘ripen’) and disfavored; with denominal verbs, the preference for complex over simple verbs is less strong. Complex CEVs also include deadjectival (especially with the prefixes ver- and er-) and denominal forms.

Turning now to the bases of complex CEVs, one can see that the class of derivationally flexible CEVs is not very large. According to the ZAS database of clause-embedding verbs, thirty-four CEVs occur with four or more preverbs: This flexible class of CEVs includes the already mentioned CEVs denken ‘think’ and fragen ‘ask’ (see (1)), the perception verbs sehen ‘see’ and hören ‘hear’, the causative verb lassen ‘let, make’ as well as a number of speech act verbs (fordern ‘request’, klagen ‘mourn’, reden ‘talk’, rufen ‘call’, sagen ‘say’, schwören ‘swear’, sprechen ‘speak’). Another subclass includes the highly frequent verbs bringen ‘bring’, geben ‘give’, gehen ‘go’, halten ‘hold’, kommen ‘come’, machen ‘make’, nehmen ‘take’, schieben ‘push’, setzen ‘put’, tun ‘do’ and ziehen ‘draw’, which in their basic uses typically do not select for clausal arguments. Complex CEVs derived from the latter group are mostly lexicalized/intransparent.

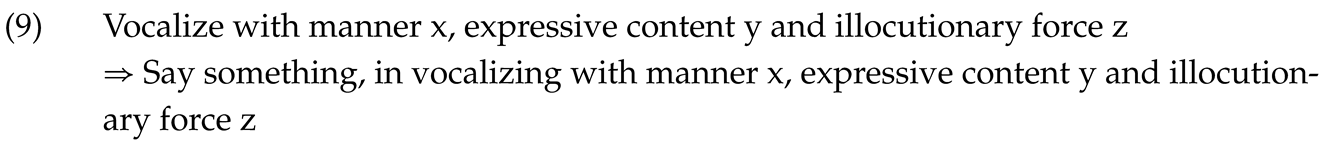

The transparent (semantically compositional) preverb patterns are usually found with CEVs that entered the language in recent times, e.g., neologisms such as twittern ‘tweet’, googeln ‘’ or posten ‘’. The class of CEVs is further enriched with manner of speaking verbs or sound emission verbs (Levin & Song, 1997; Troyke-Lekschas, 2013; Urban & Ruppenhofer, 2001; Zwicky, 1971) that are turned into clause-embedding speech act verbs. Not all sound emission verbs can be used as speech act verbs or verbs of communication. According to Urban and Ruppenhofer (2001), this is restricted to sound emission verbs that refer to sounds produced by animate entities and that, in addition, do not denote “imitative signature sounds” (e.g., oink). Wechsler (2017) proposed the following lexical rule for the derivation of speech act verbs from sound emission verbs; this rule merely adds the meaning component of speech:

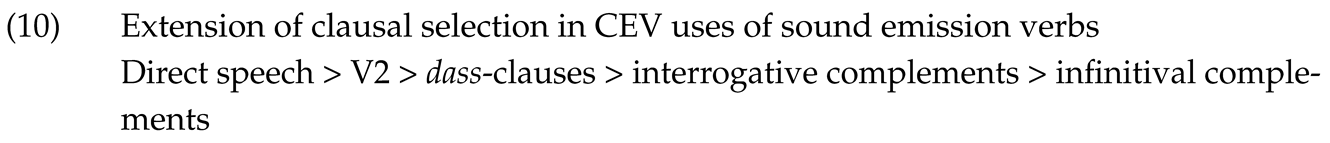

Wechsler (2017) argued against a coercion account of clause-embedding sound emission verbs, stating that that-clauses do not usually trigger a speech content reading (John signaled [that it was time to go]. ⇏ John spoke).7 Wechsler (2017) also claimed that the respective sound emission verbs cannot report questions. In her corpus study of German sound emission verbs, Troyke-Lekschas (2013) showed that there is a systematic pattern of extension of clausal selection (see (10)) for sound emission verbs that are turned into speech act verbs: These verbs first select syntactically less-integrated clause types (direct speech complements, often also verb-second (V2) clauses); later, they will add more integrated clause types (verb-final dass-clauses and interrogative complements (inter)); infinitival complements (inf) are the least common, as Table 2 demonstrates based on Troyke-Lekschas’ study of twenty-nine selected sound emission verbs8:

Table 2.

Clausal selection of 29 selected sound emission verbs (Troyke-Lekschas, 2013, p. 79).

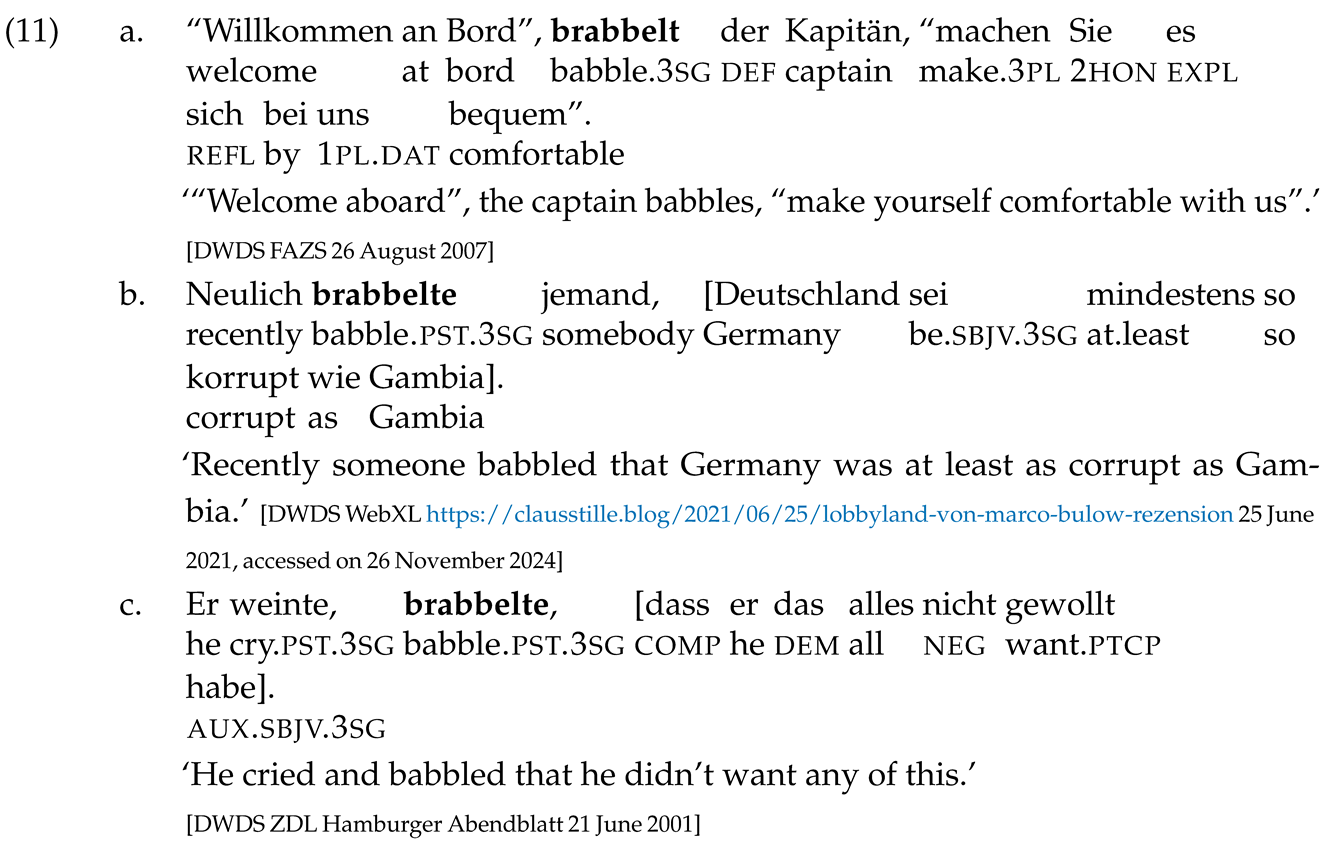

Table 3 shows the clausal selection patterns of some sound emission verbs from the ZAS database (‘✓’: occurrence of clause type is attested; ‘–’: occurrence is not attested): The verb brabbeln ‘babble’ is slightly more restricted than the other verbs in terms of attested clause types, only allowing direct speech complements as in (11a), V2-complements as in (11b) and dass-complements as in (11c).

Table 3.

Clausal selection of selected sound emission verbs according to ZAS database.

3. Impact of Preverbs on Clausal Selection

In this section, I want to illustrate that all parameters/properties of clausal complementation may be affected by preverb derivation. However, a word of caution is necessary because the various effects shown here are mostly predicate-specific (or confined to a very small class of CEVs). There is no outstanding transparent effect. In general, preverbs may extend the options for clausal embedding (=“feeding”), they may block a certain option (=“bleeding”) or they may leave the clausal selection properties of the base CEV unaffected. I will focus on the changes.

Preverbs may change the clausal selection properties of their verbal bases in various respects: they may change (i) admissible clause types, (ii) the use as raising predicate, (iii) control properties and readings, (iv) the option for restructuring, (v) the availability of neg-raising and (vi) presuppositions and entailments. Note that raising and neg-raising are confined to a small class of verbs. Therefore, no major feeding or bleeding effect induced by a preverb is expected here. I will start with a brief presentation of preverb-induced shifts in presuppositions and entailments (because they will also be relevant for explaining some of the properties discussed later); I will also briefly discuss focus sensitivity.

3.1. Presuppositions, Entailments, Focus-Sensitivity

Very few preverbs trigger presuppositions in combination with non-CEVs. The verbal particle wieder- ‘again’ triggers the common presuppositions of restitutive ‘again’; however, its distribution is rather restricted, given the parallel use of wieder as a syntactically flexible adverb (with a repetitive/restitutive interpretation; Fabricius-Hansen, 1983; Pittner, 2003; Stechow, 1996). However, wieder- does not play any relevant role with CEVs (it preferably combines with non-CEVs).

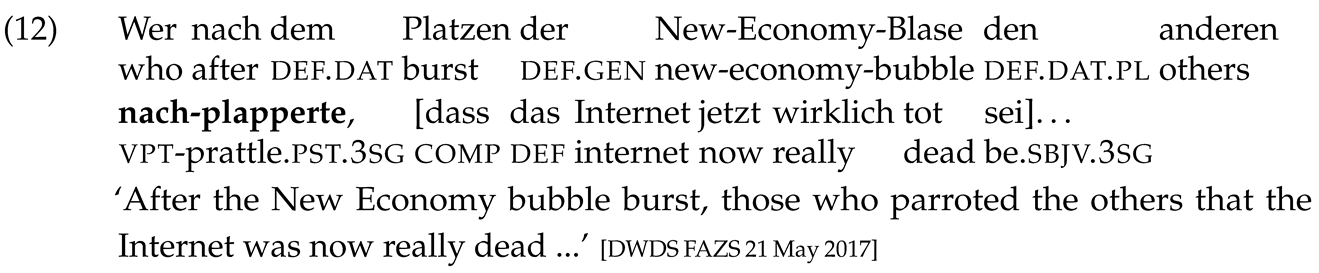

The other preverb carrying a presupposition is nach- ‘after’; it may introduce a succession relation between the asserted eventuality and another, presupposed one of the same type; see (Haselbach, 2011). However, its use with CEVs is quite restricted; the verb nach-plappern ‘repeat parrot-fashion’ would be a case in point. The added dative argument denotes the referent whose previous activity (expressed by the base verb) is presupposed, here prattling, as illustrated in (12).

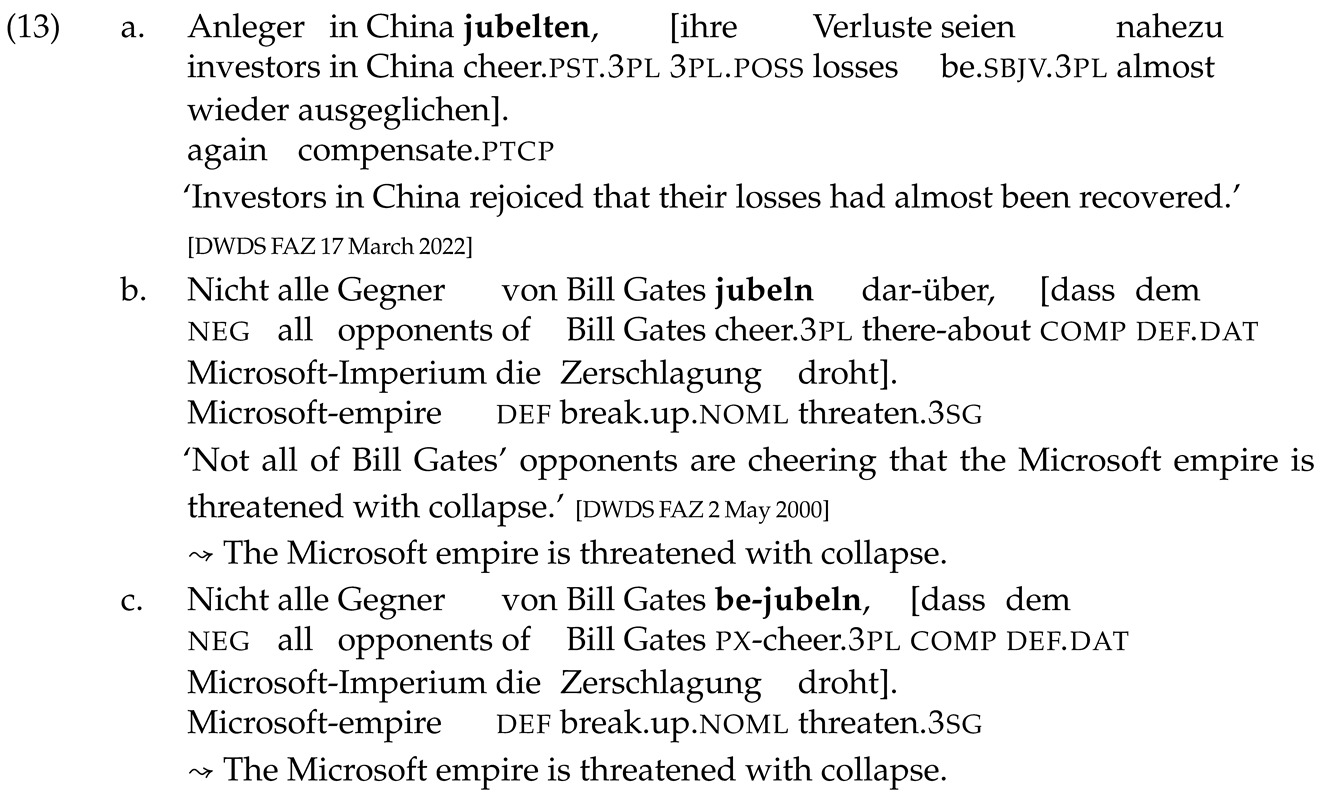

The aspect I would like to focus on in this section is the preverb’s impact on presuppositions and entailments of CEVs. Given the debate about the definition of factive verbs, which centers around the question of whether these are characterized solely by the negation projection diagnosis (Kiparsky & Kiparsky, 1970) or include the additional property of entailment of the proposition denoted by the clausal argument (see, for instance, Abrusán, 2011; Anand & Hacquard, 2014; Schlenker, 2010 and the discussion in Degen & Tonhauser, 2022 concerning the identification of factive predicates), I will use the notion of “factive verbs” only in combination with the established label “emotive-factive” verbs. Since these verbs are stative, they tend to block further preverb derivation. However, there is a preverb pattern that “creates” emotive-factive verbs. The verbs in question—manner of speaking verbs/certain sound emission verbs—typically allow for an assertive use and a derived use as an emotive-factive verb. Let me illustrate this with jubeln ‘cheer’. The assertive use can be demonstrated in combination with verb-second (V2) complements as in (13a); V2-complements are restricted to assertive predicates (see, e.g., Gärtner, 2002; Meinunger, 2004; Reis, 1997). Jubeln and similar verbs become projective under negation if the clausal argument is marked obliquely with the prepositional proform darüber ‘about’ as in (13b). The prefix be- may further derive the projective use of jubeln with its oblique argument. In line with its applicative-like use described in the literature (see, for instance, Brinkmann, 1997; Wunderlich, 1987; Zifonun, 1973), be- turns the oblique clausal argument into a direct object; the resulting verb is likewise projective under negation; see (13c).

There are further be-verbs with an equivalent behavior—not all of them being emotive-factive (e.g., be-trauern ‘mourn over’, be-staunen ‘be amazed at’, be-lächeln ‘smile at’, be-spötteln ‘make fun of’, be-klagen ‘bemoan’, be-jammern ‘bewail’).

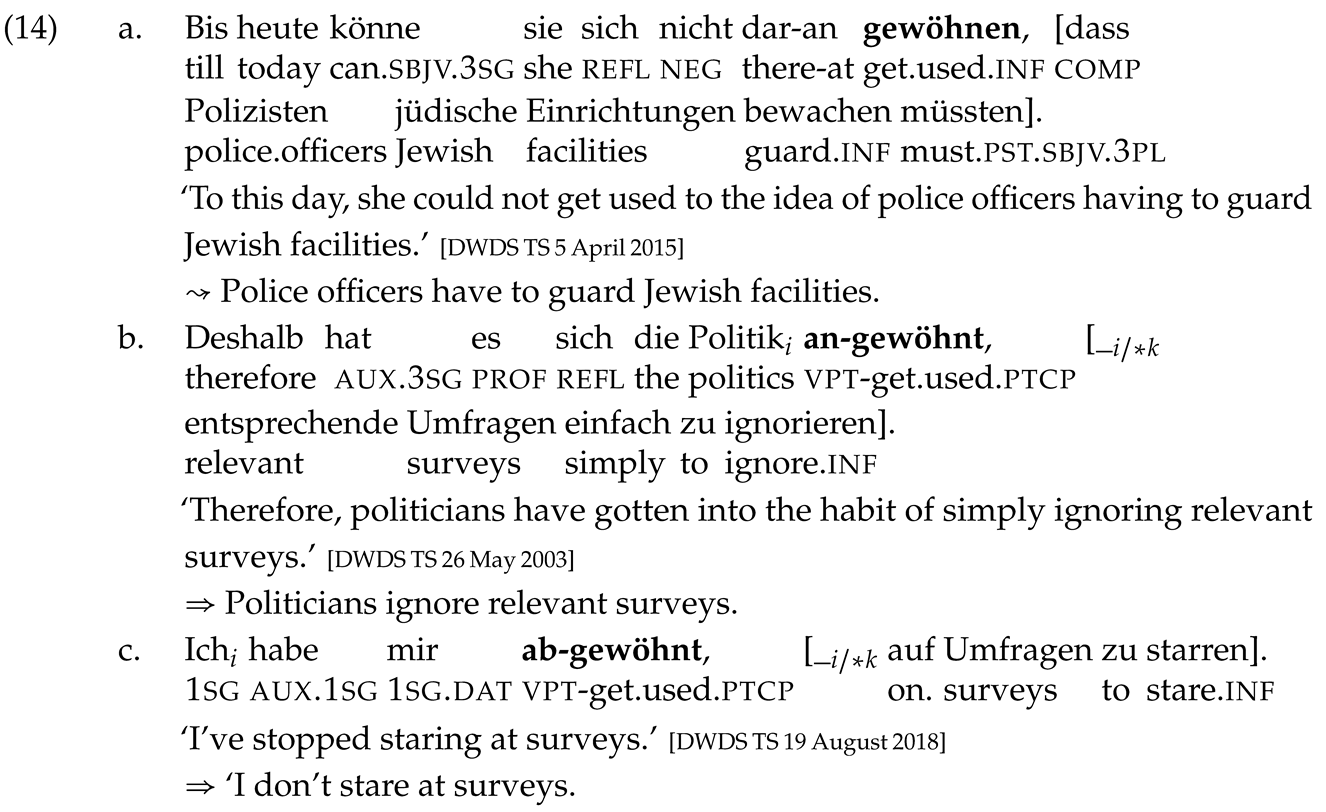

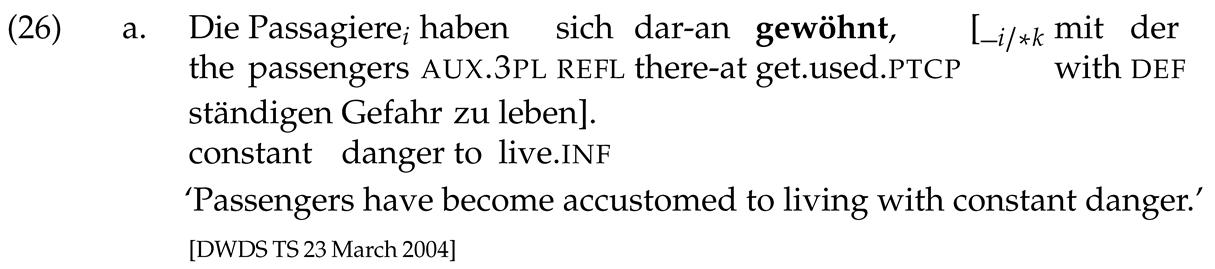

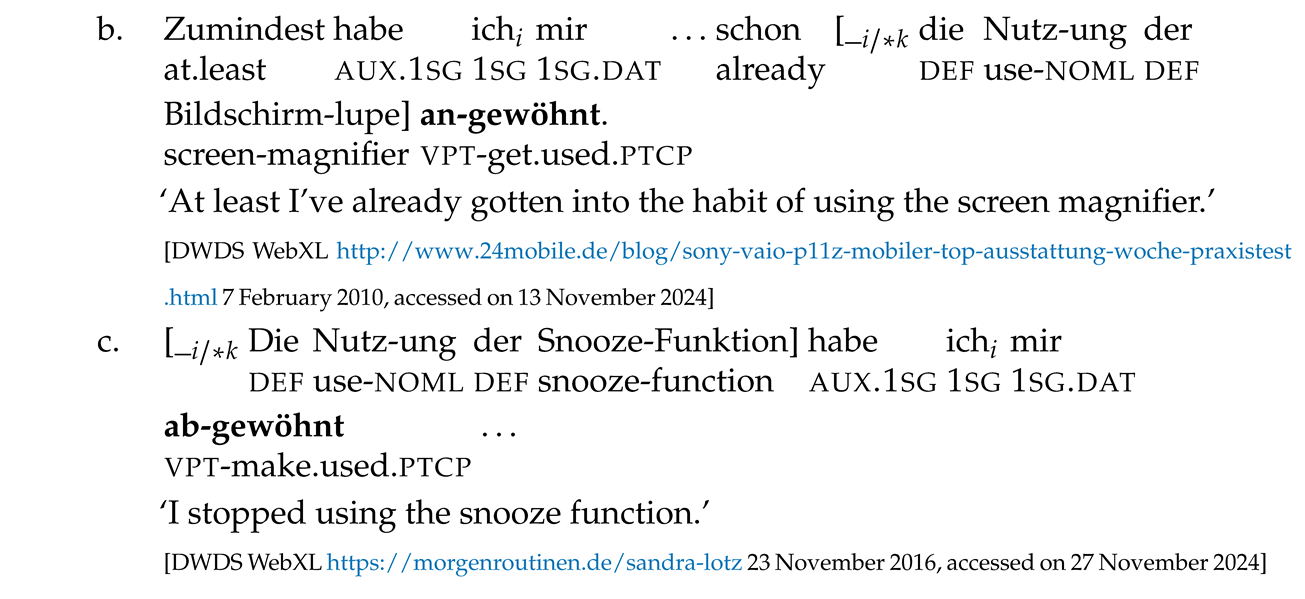

The loss of the neg-projection property can be illustrated with gewöhnen ‘get used to’ and its derivatives an-/ab-gewöhnen. The preverbs an- ‘at’/ab- ‘off’ turn the base verb (see (14a)) into an implicative verb (Karttunen, 1971): In their reflexive uses, an-gewöhnen and ab-gewöhnen refer to situations of acquiring or getting rid of habits (see (14b/c)). In their non-reflexive uses, they refer to situations in which the object referent is made to acquire or get rid of a habit. Note that the telic nature of the base verb (sich in X-Zeit an etwas gewöhnen ‘get used to something in X time’) is not shifted by the preverbs. The entailments of an-gewöhnen and ab-gewöhnen in affirmative use are illustrated in (14b/c), respectively. Under negation, this entailment does not hold.

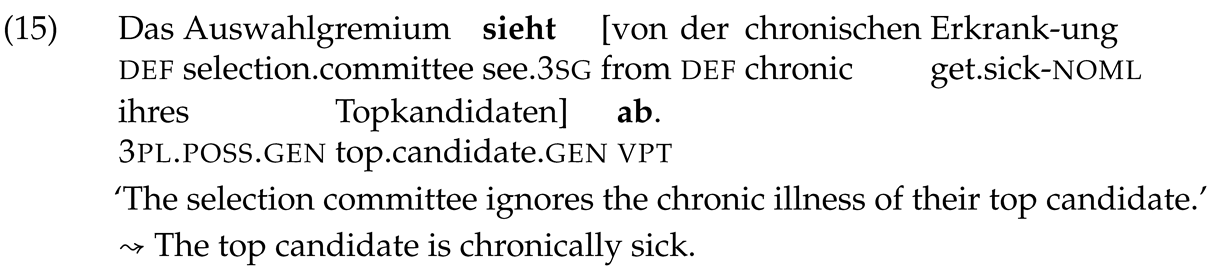

The particle ab- is also involved in another interesting case of shift between presupposition and entailment. The verb sehen ‘see’ is projective with finite complements. The derivative ab-sehen (off-see) has four readings, two of which are interesting here. If the clausal complement is marked obliquely with the proform da-von ‘from’, ab-sehen either obtains the projective reading ‘ignore’ or the implicative reading ‘refrain from’ (entailing ¬p in the affirmative use of CEV). The former is mainly attested with finite complements, the latter with infinitival complements. However, both readings are also attested with nominalized complements, which means that the clausal complement structure as such does not disambiguate the readings here. In its interpretation ‘ignore’, ab-sehen is mainly used in conditional sentences or as some more or less grammaticalized exclusion marker ab-gesehen (davon) ‘ignoring that’. Therefore, often, the concrete use of ab-sehen will disambiguate the two readings. However, one can also find cases in which the situation denoted by the nominalized clause determines the interpretation. Since the reading ‘refrain from’ selects for dynamic/eventive complements, examples in which the nominalized clause refers to a (result) state obtain the reading ‘ignore’, see (15). Note that, in addition, the reading ‘refrain from’ can only select complements that allow for a control reading; this is not possible in (15) because all arguments of Erkrankung are overtly saturated.

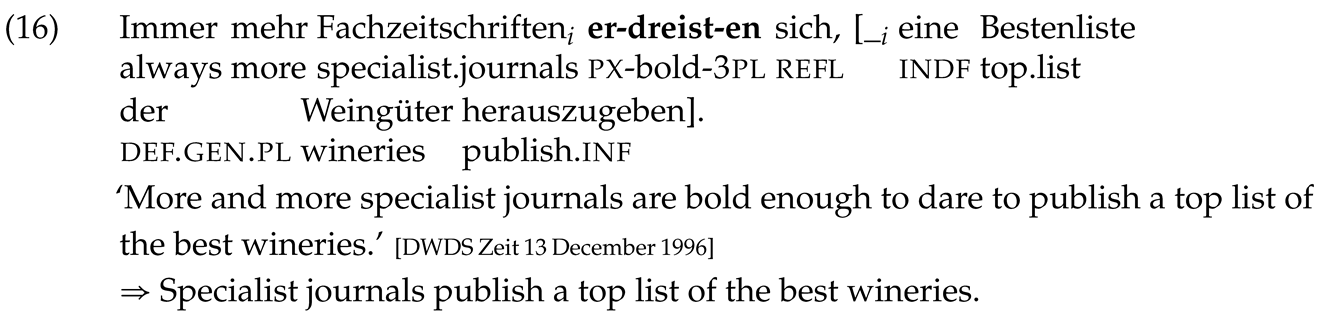

Apart from one niche pattern with the prefix er-, there is no systematic derivation of implicative verbs via preverbs. The verbs of this niche are deadjectival verbs (e.g., er-dreist-en px-bold-inf ‘have the audacity to do sth’, er-kühn-en px-brave-inf, er-blöd-en px-stupid-inf, er-frech-en px-cheeky-inf) and inherently reflexive; they only select infinitival complements. The base adjectives constitute a subclass of human propensity adjectives and refer to some kind of audacious character, which makes the subject referent dare to do what is denoted by the infinitival complement. Example (16) is an illustration for er-dreisten. Matrix negation cancels the entailment.

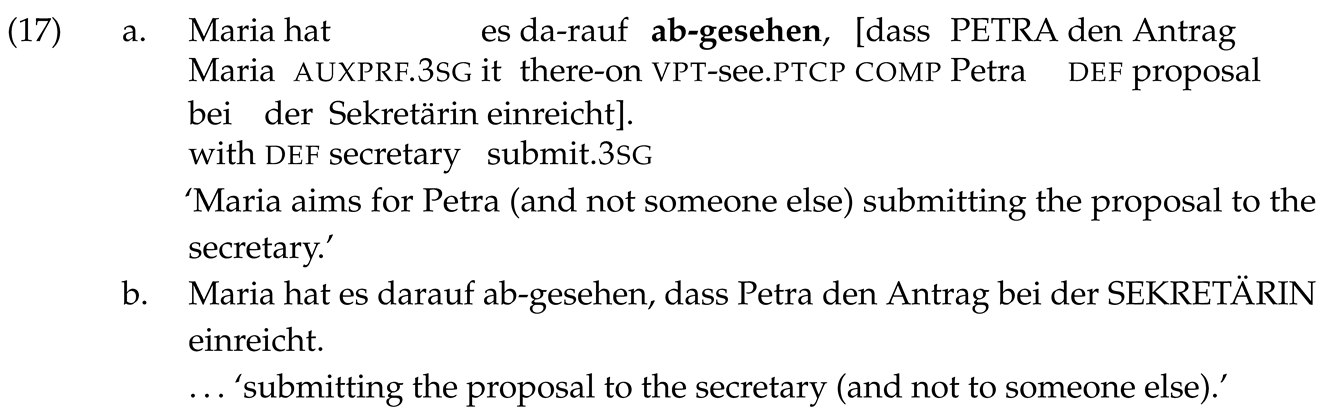

I would like to conclude this section with the illustration of a preverb-induced change in focus sensitivity (see Harner, 2016; Romero, 2015; Villalta, 2008), which is one of the many relevant semantic properties of attitudinal CEVs discussed in Özyıldız et al. (2023).

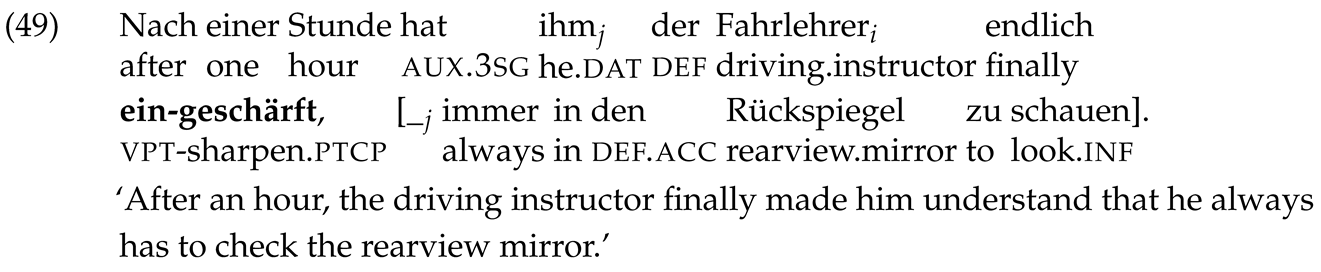

Unlike its base verb sehen ‘see’, the derivative ab-sehen has a reading that displays focus sensitivity and gradability. The reading ‘aim for’ is associated with a case pattern in which the clausal argument is obliquely marked with the proform dar-auf ‘on’. Focus sensitivity is typically demonstrated with a scenario like the following: Imagine a situation in which Maria has to submit a proposal to her department. She cannot hand in the proposal herself. She wants Petra to submit the proposal for her—not someone else. However, she does not care whether the proposal is submitted to the secretary or the head of the department. In this context, the focus on Petra as in (17a) is correct, whereas the focus on Sekretärin ‘secretary’ as in (17b) is false.

Furthermore, (es darauf) ab-sehen is gradable (es sehr darauf ab-sehen ‘very much aim for’).

3.2. Clause Type

German CEVs differ in their selection of clause types. The clausal complementation system of German can be classified according to two major parameters: (a) declarative vs. interrogative clausal complements and (b) finite vs. non-finite clausal complements. Finite declarative complements include verb-final clauses with the complementizer dass and embedded verb-second complements. Non-finite declarative complements include infinitival clauses (inf) and nominalized clauses (noml). Standard German only allows finite interrogative complement clauses (polar interrogatives with the complementizer ob ‘whether’ and WH-complements). Dass-clauses represent the default option, whereas V2-complements are the most restricted in German, which means that they have the strongest coercive potential (e.g., triggering a non-projective reading of bedauern ‘regret’ as ‘say with regret’). Nominalized clausal complements are subject to a syntactic and a semantic restriction: Syntactically, they must obtain case9, which means that a nominalized clause is excluded if the CEV does not assign a structural or oblique case to its clausal argument. Semantically, nominalized clauses are excluded with (coerced) speech act predicates if the clausal argument refers to the content of the utterance and not the topic of the utterance. Many German CEVs are quite flexible in terms of clause type selection; 428 of the CEVs listed in the ZAS database are attested with all clausal complement types. However, this will often involve distinct argument structures, argument realization patterns and/or polysemy.

The first parameter (declarative vs. interrogative complements) is relevant for the classification of CEVs as responsive, rogative and anti-rogative predicates. Responsive predicates allow declarative and interrogative complements, whereas rogative predicates are confined to interrogative complements and anti-rogative predicates to declarative complements. The relevant question here is whether a preverb or a preverb pattern may (systematically?) shift a verb from one class to another. There is a debate as to which semantic properties determine class membership of CEVs. White (2021) critically assesses proposals by Egré (2008) (responsive predicates correspond to the class of veridical predicates) and Uegaki and Sudo (2019) (anti-rogative predicates are non-veridical and preferential, i.e., show focus sensitivity in their clausal complement); he shows that corpus studies and judgment tasks do not provide a neat picture with respect to class membership.

Table 4 illustrates the attested clause types for fragen and its derivatives; it also includes the option for simple DP objects. All derivatives retain the possible selection of interrogative complements. (‘✓’: occurrence of clause type attested; ‘–’: occurrence not attested; ‘?’: attestations questionable;‘WH’: content question, ‘ob’: polar questions with ob).

Table 4.

Preverb derivatives of fragen ‘ask’.

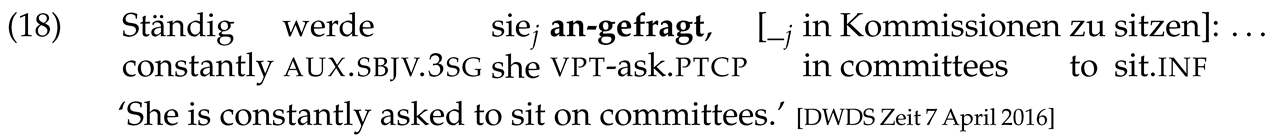

Two aspects are surprising: (i) the licensing of dass-complements with a question speech act predicate such as fragen (and derivatives) and (ii) the licensing of an infinitival complement with an-fragen. The latter, which should be ungrammatical due to the ban of WH-infinitives in Standard German, is explained with the meaning shift observed in an-fragen: from the inquire reading of fragen ‘ask’ to a request reading (a crosslinguistically common co-lexification; see François, 2008 for the notion of co-lexification and the CLICS database for ‘ask’ https://clics.clld.org/, accessed on 20 February 2025). Example (18) illustrates a relevant case:

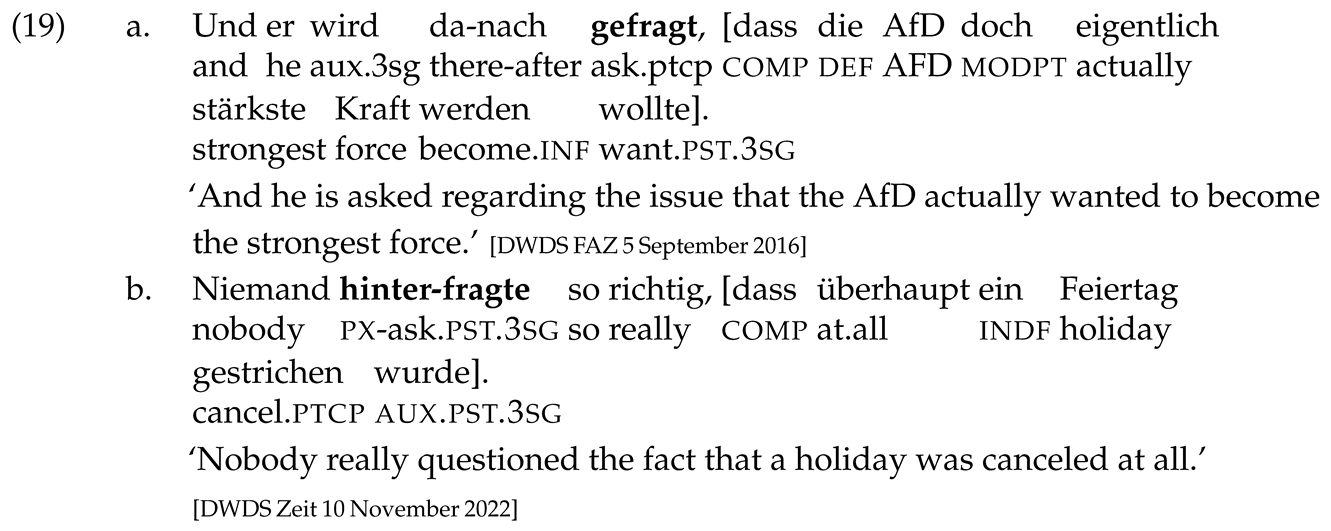

The licensing of declarative complements has its explanation in the shift of the propositional content: the dass-complement does not refer to the content of the question speech act but to its topic (see Bondarenko, 2021) for the distinction of content/topic of utterance and Elliott, 2017; Pietroski, 2000 for the same distinction under the label explanans/explanandum). This explanation is valid for (danach) fragen, hinter-fragen and (dazu) be-fragen. Example (19) provides relevant examples for fragen and hinter-fragen.

Er-fragen is different in that er- shifts the propositional content in a different way. The clausal complement of er-fragen denotes the answer to the question (see Section 4.3 for details).

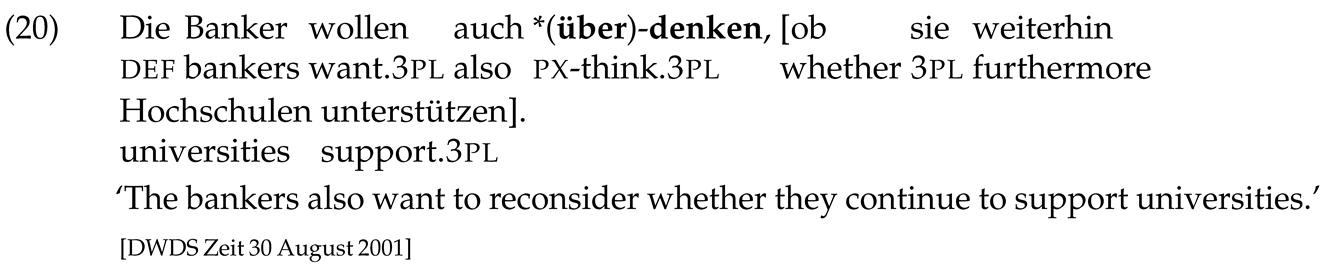

From the discussion in Özyıldız (2021), we know that lexical aspect may play a role for the licensing of interrogative complements. For instance, in its stative use/interpretation, the English think blocks interrogative complements, whereas in dynamic uses (e.g., in the progressive), interrogative complements are possible. German denken ‘think’ has a stative and a dynamic use; the latter is observed with the prepositional proform dar-an ‘at’. Many derivatives of denken are dynamic (e.g., be-denken ‘consider’, über-denken ‘think over’, durchpx-denken ‘think through’ and nach-denken ‘be thinking’) and thus license interrogative complements. Example (20) shows that the dropping of the prefix über- ‘over/about’ would result in ungrammaticality in the case of an interrogative complement.

Since most stative CEVs resist further preverb derivation, the pattern found in denken is not attested on a large-scale basis.

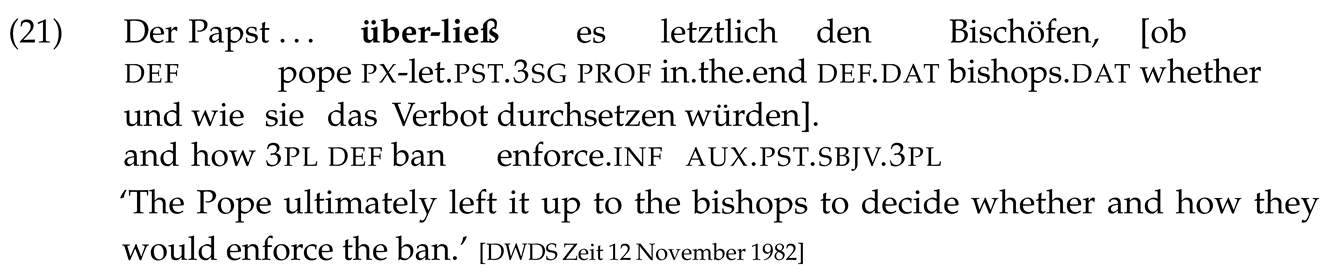

The shift from a responsive to a rogative selection pattern can be found with hören ‘hear’ and some of its derivatives: With finite complements, hören behaves as a responsive predicate. However, the two derivatives (sich) umvpt-hören ‘ask around’ and ver-hören ‘question sb’ only select interrogative complements given their purely inquisitive nature. With ver-hören, the clausal complement is optional. Similarly, sehen ‘see’ is shifted from a responsive to a rogative predicate with nach-sehen (after-see) in the reading ‘check’ and (mit) an-sehen (at-see) in its reading ‘stand and watch’. A further interesting case is causative/permissive lassen ‘make, let’, which does not select interrogative complements. Its derivative, überpx-lassen ‘leave it up to sb to do sth’, which obtains the permissive reading of granting options to someone, does select interrogative complements, as shown in (21):10

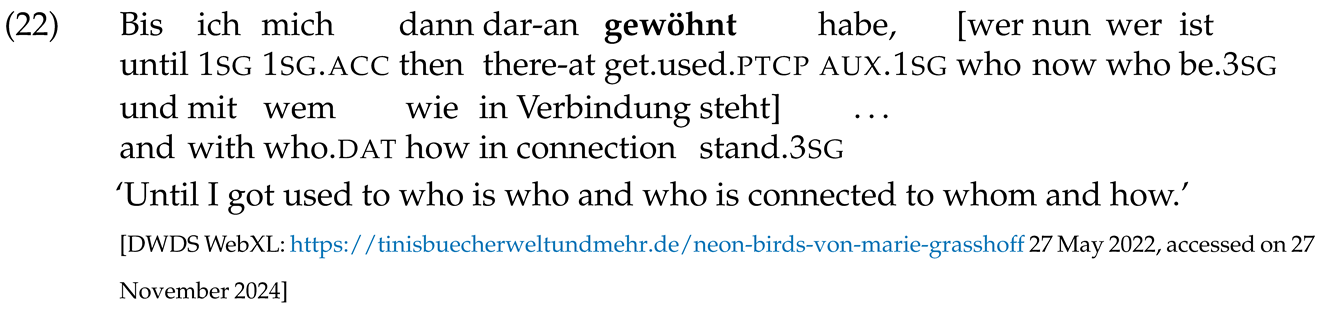

Gewöhnen ‘get/make used to’ shows a different type of shift with respect to interrogative complements; it only selects WH-interrogatives as in (22). The implicative derivatives ab-/an-gewöhnen block any type of interrogative complement.

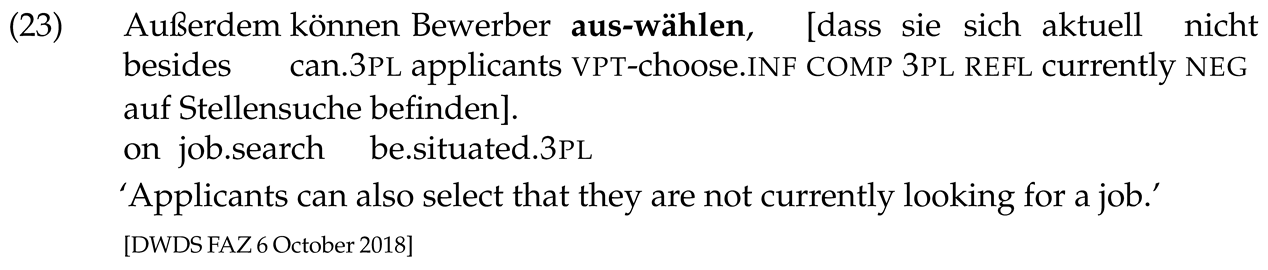

Among the 21 predicates of the ZAS database that would qualify as rogative predicates (attested with interrogative but not with finite declarative complements), only three (schwanken ‘vacillate, hesitate’, wählen ‘choose, select’, zaudern ‘hesitate, vacillate’) are morphologically simple and would allow preverb derivation in principle. However, only wählen is further derived with a preverb (e.g., aus-wählen ‘select (from)’). This derivative is attested with dass-complements:

The reasoning for this shift may lie in the fact that aus-wählen in contrast to wählen seems to have a stronger focus on the selection from alternative options. The clausal complement in (23) denotes the chosen option.

A further potential shift in clause type selection is a preverb-induced shift in finiteness. I will focus on the shift between infinitival complements and finite dass-complements. Infinitival complements represent clausal complements that are reduced along two dimensions: (i) the subject cannot be overtly realized, thus requiring a control or raising predicate as matrix predicate (see next subsection), and (ii) infinitival complements are very restricted in TMA specifications; anteriority can be marked with the infinitival auxiliaries haben/sein and modality with infinitival modals (e.g., können ‘can’, dürfen ‘be allowed’ and müssen ‘must’). However, it seems that German—in contrast to many other languages—is still an “infinitive-happy” language given the high number of CEVs with infinitival complements in the ZAS database. In contradiction to Wöllstein’s (2015) generalization that there is an implicational relational between the selection of infinitival complements and finite dass-complements (infinitival complement ⇒ dass-complement), one can find 43 predicates in the ZAS database that do not follow this pattern; they select infinitival complements without selecting finite dass-clauses. Many of these verbs are implicative verbs. Rapp et al. (2017), who studied the impact of three parameters for the selection of infinitival complements vs. dass-complements, found out that the parameter of “semantic control” represents the strongest factor for the selection of infinitival complements. For them, semantic control is a slightly weaker notion than “inherent control” (Stiebels, 2010). It reflects the preference for uses that exhibit co-reference between an argument of the CEV and the subject of the complement clause (even with dass-complements). The semantic factor behind this behavior—according to the authors—is the matrix subject’s responsibility for the situation denoted by the clausal complements (similar to Farkas’s 1988 responsibility relation RESP). The two other factors, temporal variability (dispreference for infinitival complements with CEVs that select temporarily variable complements) and variability in modality (dispreference for infinitival complements with CEVs that select complements with variable modality) have a lower predictive force for the finiteness of the clausal complement. In view of the observation that the selection of dass-clauses vs. infinitival clauses is less of a categorical nature but reflects preferences/tendencies according to these factors, shifts in finiteness may often go unnoticed. Preverbs affecting one or more of these three factors established by Rapp et al. (2017) may have an impact on the preferred clause type selection pattern. For example, many manner of speaker verbs disfavor infinitival complements. Schwatzen ‘chatter, prattle’ would be a representative instance. However, the derivative be-schwatzen ‘talk over’ receives a directive interpretation in combination with argument extension (‘talk sb into doing sth’), which licenses infinitival complements due to the added factors of semantic control, and temporal and modal invariability.

3.3. Control and Raising

CEVs combine with infinitival complements either as raising or control verbs. The class of raising predicates is small and more or less closed, whereas the class of control predicates is open. Since German raising verbs build a subset of obligatorily restructuring predicates (see Section 3.4), I use the notion of “raising verb” not in the strict syntactic sense (involving syntactic movement of the embedded subject), but as a label for the thematic property of the verbs (i) to license embedded impersonal verbs, (ii) to maintain the idiomatic interpretation of subject idioms (the cat seems to be out of the bag) and (iii) to not require a change in the model with embedded passives (Peter seems to be invited to the party). German only exhibits raising verbs, with no raising adjectives. There are simple (e.g., scheinen ‘seem’, modals) and morphologically complex raising verbs (e.g., the aspectual/phasal verbs an-fangen ‘start’ and auf-hören ‘stop’).

Some CEVs show a dual use as raising and control verb, e.g., phasal CEVs such as an-fangen and auf-hören, and the commissive speech act predicates drohen ‘threaten’ and ver-sprechen ‘promise’ (Heine & Miyashita, 2008; Reis, 2005). The verbal base of auf-hören is used as an AcI/ECM verb, whereas sprechen has no raising verb use. Other raising verbs such as scheinen (and other epistemic modals), pflegen and drohen either block a preverb derivation (e.g., epistemic müssen ‘must’), or their derivatives are no longer clause-embedding, or they at least lose their status as a raising verb (e.g., durch-scheinen ‘show through’). Table 5 shows some exemplary cases for the shift in the raising property (‘+’: raising, ‘–’: non-raising; ‘±’: verbs with a dual use as control and raising verb).

Table 5.

Examples for a change in the raising property.

Control verbs may be affected by preverb derivation along the various parameters of control (see Kiss, 2015; Landau, 2013; Stiebels, 2015) for an overview on complement control): (i) subject vs. object control, (ii) invariant (e.g., raten ‘advise’) vs. variable control (e.g., vorschlagen ‘propose’), (iii) exhaustive vs. non-exhaustive/partial control (Landau, 2001, 2015; Pearson, 2016) and (iv) inherent vs. structural control (Stiebels, 2007, 2010). Since preverbs may change the argument structure of their base, changes in controller choice are expected.

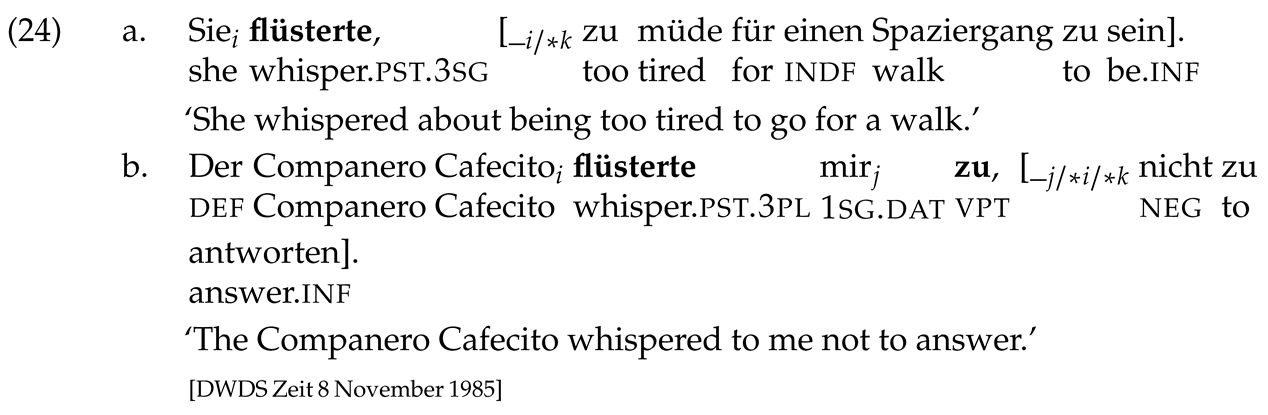

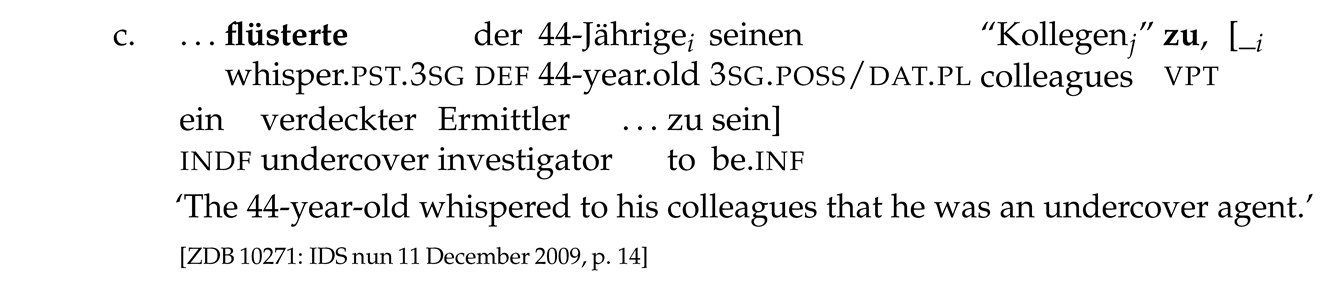

Argument extension induced by the preverb may change or add control readings. As illustrated above, the verbal particle zu adds a dative addressee argument in the transfer of information reading; the resulting verbs allow for variable control, as in semantically equivalent verbs; the pattern is illustrated for zu-flüstern. The base verb flüstern ‘whisper’ is not attested with infinitival complements, although an example such as (24a) with obligatory subject control seems acceptable. The object control reading of zu-flüstern ‘whisper to sb’ in (24b) results from a directive interpretation, which is the more prominent interpretation here. However, it is also possible to obtain a subject control reading as in (24c); here, the verb has the reading ‘narrate by whispering’.

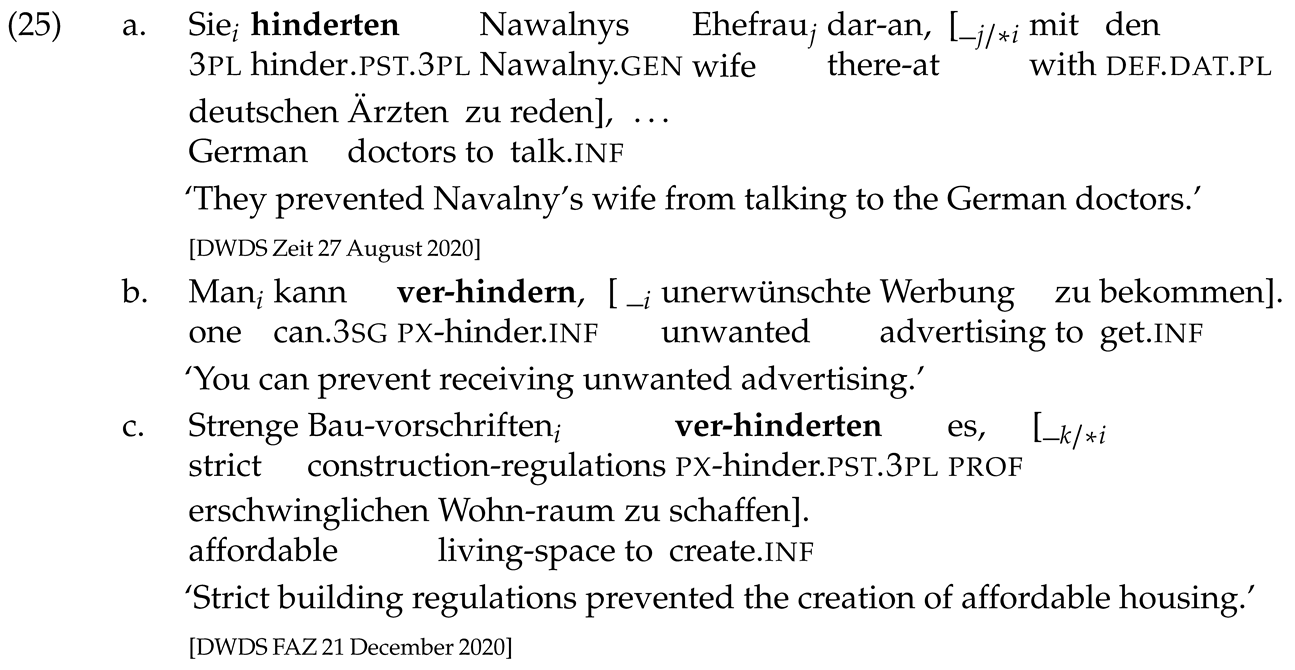

Since the formation of complex CEVs may also lead to the blocking of internal arguments, an object control verb can be affected by this blocking. The case of the object control verb hindern ‘hinder’ and its derivative ver-hindern shows that the blocking of the internal argument affects control in two possible ways: an obligatory control relation can be maintained if the embedded clause provides a control shift context, which allows the subject referent of ver-hindern to act as controller. Example (25a) illustrates the use of hindern as an object control predicate. In (25b), the shift to subject control is triggered by the recipient-oriented embedded verb bekommen ‘receive, get’. Alternatively, non-control/“arbitrary control” may emerge as in (25c). This is typically the case with inanimate subject referents. Arbitrary control in infinitival object clauses is very restricted in German.

The shift from structural control to inherent control can be demonstrated with the CEV gewöhnen ‘make/get used to’ and its derivatives. Many CEVs are structural control predicates, i.e., they do not require any co-reference between one of their arguments and an argument of the clausal complement outside of infinitival complements. In contrast, inherent control predicates require co-reference with all types of clausal complements; many object control verbs are inherent control predicates (Stiebels, 2010). The verb gewöhnen exhibits structural control (see (26a)), i.e., with clausal complement types other than infinitival complements no argument in the complement clause must be co-referential with the subject referent of the matrix verb (see (14a)). In contrast, an-gewöhnen and ab-gewöhnen are inherent control predicates, as the admissible readings with the nominalized complements in (26b/c) illustrate.

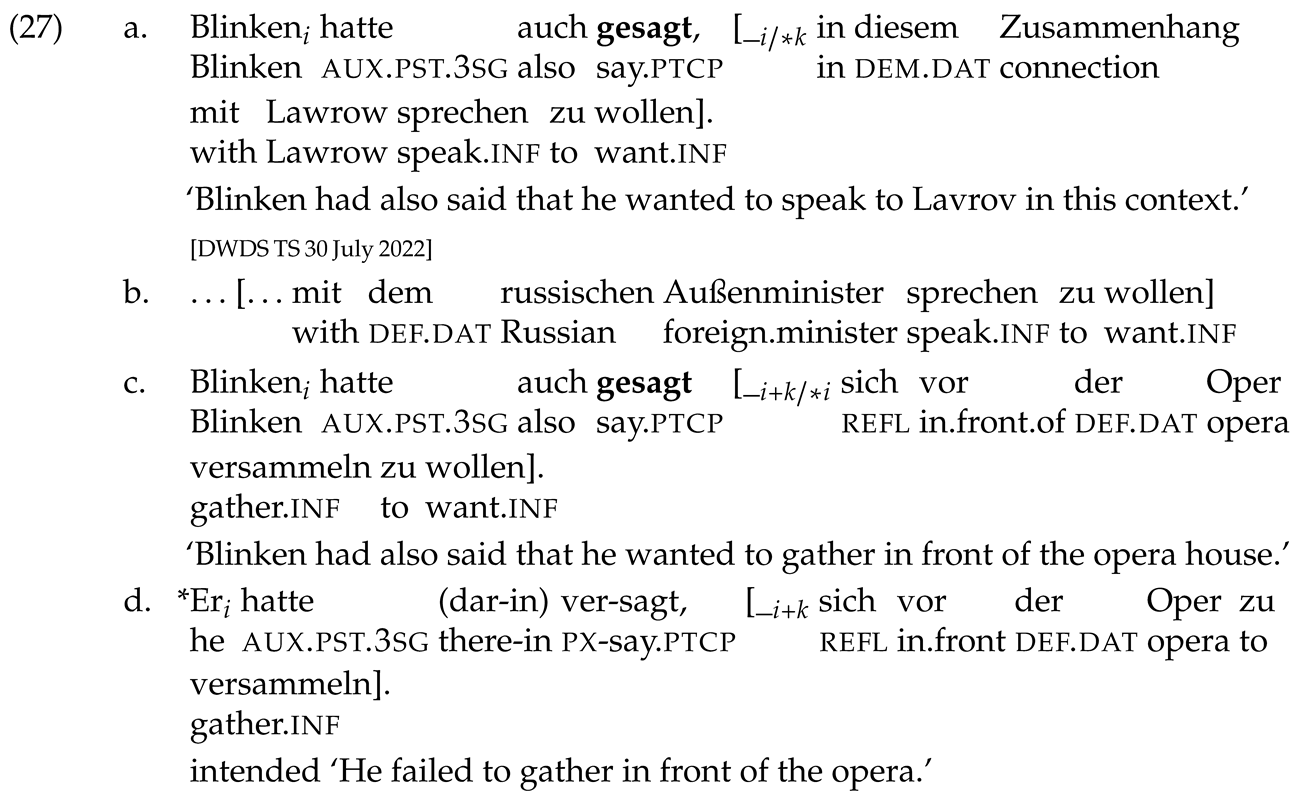

Since non-exhaustive/partial control is licensed by attitude predicates (Landau, 2015; Pearson, 2016), preverbs that would derive attitude predicates or turn attitude predicates into non-attitudinal CEVs would be the relevant candidates to show a corresponding shift in control readings. The shift from attitudinal to non-attitudinal CEVs can be observed with the prefix verb ver-sagen ‘fail, deny sb/oneself sth’ derived from sagen ‘say’. The opacity test shows that sagen is an attitude predicate: Referential substitution of the proper name Lavrov in (27a) with the expression ‘Russian foreign minister’ as in (27b) yields a different speech act content, which does not follow from (27a). Example (27c) shows that sagen may license partial control with embedded collective predicates (the referential index ‘i+k’). In contrast, ver-sagen ‘fail’ does not allow the embedding of collective predicates with singular subject referents and only licenses exhaustive control.

Note that ECM verbs may be turned into control verbs. The prefix er- turns the ECM verb lassen ‘make, let’ into an object control verb with inherent control (lassen may embed impersonal verbs, er-lassen does not). The verbal particle vor- ‘before’ turns the ECM verb sehen ‘see’ either into a subject control verb with inherent control (under the reading ‘take care (not to do)’) or into a verb with structural control (under the reading ‘plan’), which may exhibit subject control with animate referents or arbitrary control with inanimate subjects (see (32a)).

Table 6 summarizes the patterns mentioned above (SC: subject control, OC: object control, inh: inherent control, ARB: arbitrary control).

Table 6.

Examples for changes in control properties.

3.4. Restructuring

Restructuring (clause union) is also confined to a small class of clause-embedding verbs. Languages differ in their inventory of restructuring predicates (and their specific restructuring properties); however, they converge on some typical predicates such as modals and evidentials (‘seem’), aspectual/phasal predicates, causatives, verbs of motion and some other predicates (e.g., ‘know how’, ‘try’, certain implicatives, see the appendix in Wurmbrand, 2001).11 According to Cinque (2001, 2004), restructuring CEVs semantically match the content of certain functional heads.

German CEVs that select for infinitival complements differ as to whether they obligatorily require, optionally allow or generally exclude the restructuring/clause union of infinitival complement and matrix clauses (Bech, 1955; Haider, 2010; Wurmbrand, 2001). CEVs that select bare infinitival complements (without the prefix zu ‘to’) are obligatorily restructuring; this class includes modals, the future auxiliary, perception verbs (e.g., sehen ‘see’/hören ‘hear’) and the causative verb lassen ‘let/make’.12 In addition, some CEVs that select for infinitival complements marked with the prefix zu- are also obligatorily restructuring, e.g., the epistemic verb scheinen ‘seem’; the aspectuals an-fangen ‘start’, auf-hören ‘stop’, pflegen ‘use to’; and wissen in its reading ‘know how’. Quite interestingly, any preverb that combines with CEVs that select for bare infinitival complements shifts the type of the infinitival complement to one marked with zu-; this does not necessarily entail that the derived verb is no longer obligatorily restructuring given the existence of obligatorily restructuring CEVs that select zu-marked infinitival complements.

Restructuring is excluded with CEVs whose clausal argument is not in an acc-marked object position. Related to this restriction is the observation that restructuring is also excluded if the CEV exhibits a further internal acc-marked argument; with the exception of a few double accusative verbs (e.g., sehen, hören, lassen), the clausal argument of a CEV with an internal individual acc-marked argument is either overtly or covertly oblique. Preverb derivation of CEVs may thus affect restructuring due to two factors: (i) the preverb changes the argument realization of the clausal argument (from acc to oblique or vice versa) and/or (ii) the preverb adds a further internal acc-marked argument (e.g., auf-fordern ‘request’). Factor (i) also includes the addition of the sentential proform es, which ousts the clausal argument from its structural acc position.

I follow Haider (2010) in illustrating restructuring (more specifically, clustering) with VP topicalization13 as in (28a) and non-restructuring with structures in which the embedded predicate and the matrix predicate are separated by some XP, thus violating the “compactness” requirement (Bech, 1955); see (28b). These contexts allow to distinguish the three classes with respect to restructuring.

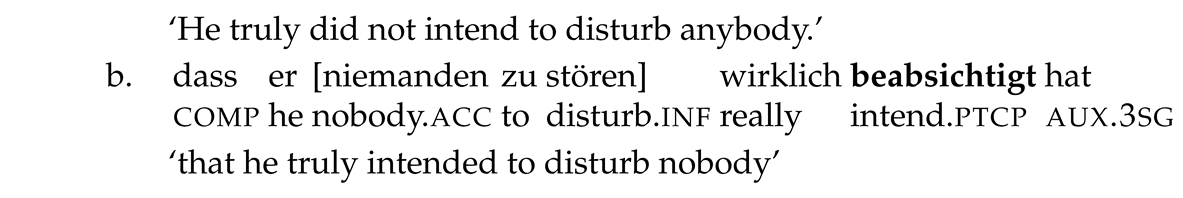

The shift from obligatory restructuring to non-restructuring can be demonstrated with wollen ‘want’ and its derivative (darauf) hinaus-wollen ‘get at’. Wollen disallows the violation of compactness, demonstrated in (29a) with the insertion of negation. Moreover, it also disallows extraposition of its infinitival complement as in (29b). Since the clausal argument of hinaus-wollen is oblique (marked with the prepositional proform hinaus ‘out’), extraposition is required as in (29c). Intraposing the infinitival complement as in (29d) is ungrammatical—with or without the further insertion of an intervening XP.

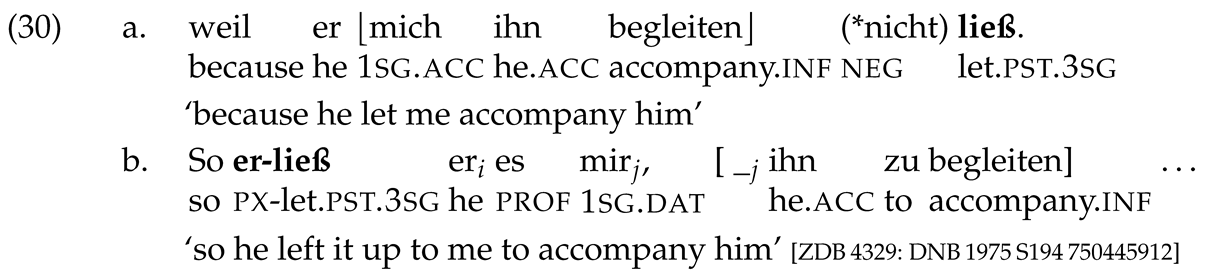

Almost parallel to (hinaus)-wollen, lassen ‘cause/let’ and its derivative er-lassen in the reading ‘let sb off V-ing’ differ in terms of restructuring. Example (30a) shows the compactness of the restructuring context with lassen. er-lassen does not allow restructuring due to the selected sentential proform es; it is usually attested with extraposition as in (30b).

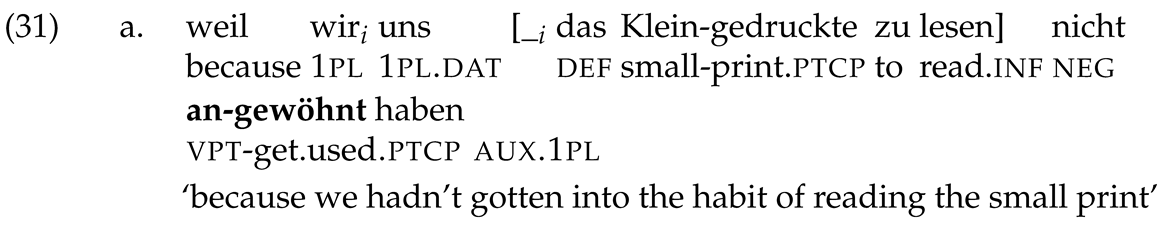

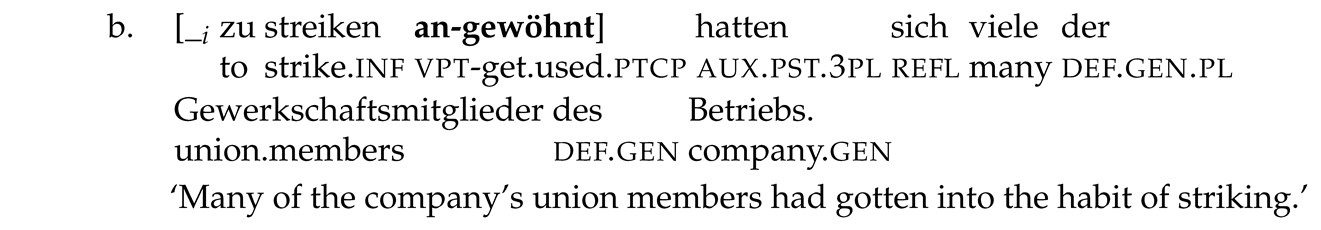

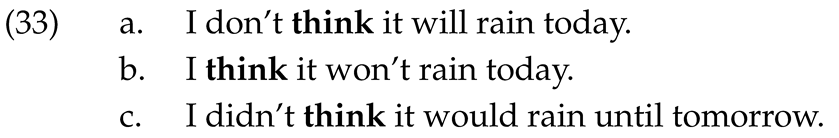

One can also observe that a preverb may turn a non-restructuring CEV into an optionally restructuring CEV; gewöhnen/an-gewöhnen represent a relevant instance. Due to the oblique realization of the clausal argument (sich dar-an gewöhnen), restructuring is excluded with the base verb gewöhnen. However, an-gewöhnen has an acc-marked clausal argument and, thus, allows non-restructuring (31a) as well as restructuring (31b) structures.

A shift from obligatory restructuring to optional restructuring can be observed with vor-sehen in its reading ‘plan’. Example (32a) illustrates non-restructuring, whereas (32b) illustrates restructuring.

Table 7 summarizes the patterns found so far (‘+’: obligatory restructuring; ‘–’: no restructuring; ‘±’ optional restructuring). The major triggering factor for changes is the change in argument realization.

Table 7.

Examples for a shift in restructuring (RS).

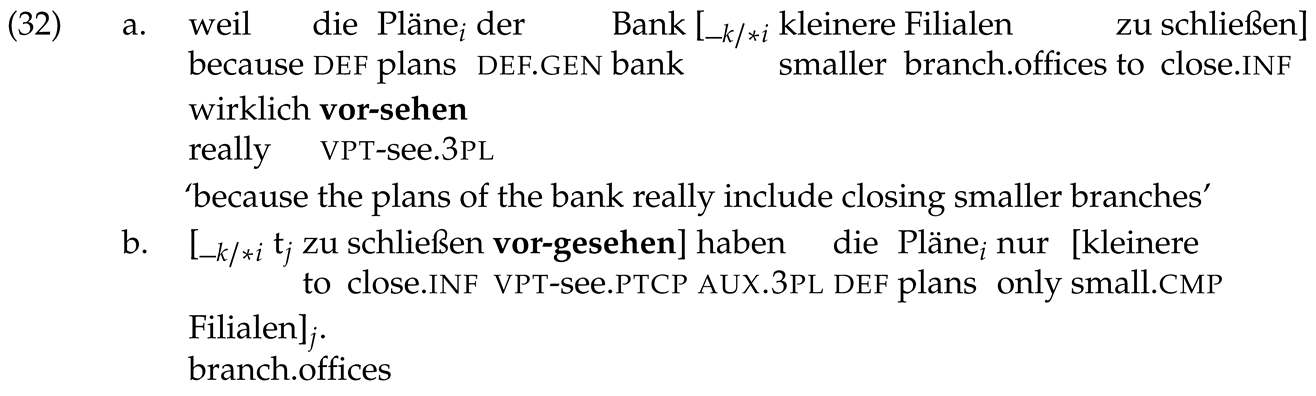

3.5. neg-Raising

Another property that is confined to a restricted class of CEVs is neg-raising (Collins & Postal, 2014; Fillmore, 1963; Horn, 1971). Negation of a neg-raising CEV allows for an interpretation in which the negation seems to take scope from the complement clause. Thus, (33a) may be interpreted like (33b). Furthermore, strict NPIs (e.g., until X) may be licensed in the complement clauses of negated neg-raisers as in (33c).

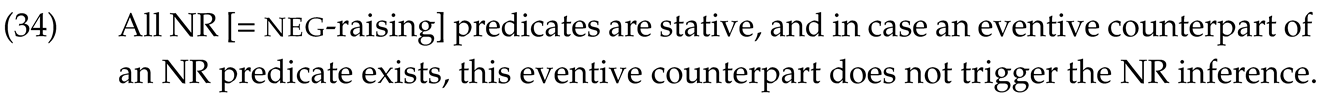

Recent studies (Bervoets, 2014; Jeretič & Özyıldıız, 2022; Özyıldız, 2021; Xiang, 2013) showed that the option for neg-raising may depend on the (lexical) aspect of the CEV. Following Bervoets (2014), Jeretič and Özyıldıız (2022, p. 134), formulate the following generalization:

The following pair of examples taken from Bervoets (2014) illustrates the blocking of neg-raising in the eventive interpretation of think, which is induced by progressive aspect as in (35b).

The aspectual condition is a necessary, but insufficient condition. Not all stative CEVs act as neg-raisers (e.g., emotive factives such as lieben ‘love’/hassen ‘hate’).

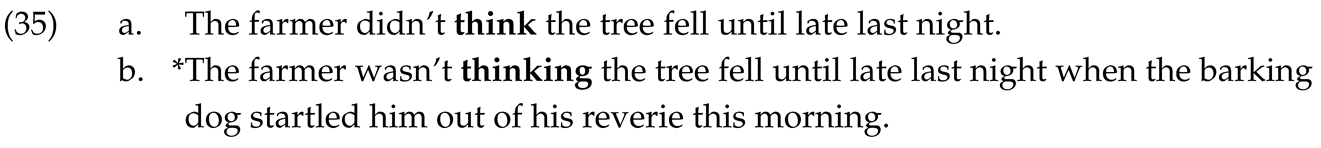

German denken ‘think’ is also a neg-raising predicate in its stative use (see (36a)).14 None of the preverb derivatives of denken retain its neg-raising property. Aus-denken ‘think up sth’, nach-denken ’be thinking about’, durch-denken ‘think sth through’ and be-denken ‘consider’ are all eventive (evidenced, for instance, by the combination with verbs relating a situation to the passing of time). I will illustrate this for nach-denken. Example (36b) shows that nach-denken does not have the neg-raising inference. Example (36c) shows that nach-denken passes the test for being dynamic/eventive.

According to the generalization first proposed by Zuber (1982), neg-raising CEVs are anti-rogative, i.e., they do not select interrogative clausal complements. The non-neg-raising derivatives of denken all allow for interrogative complements.

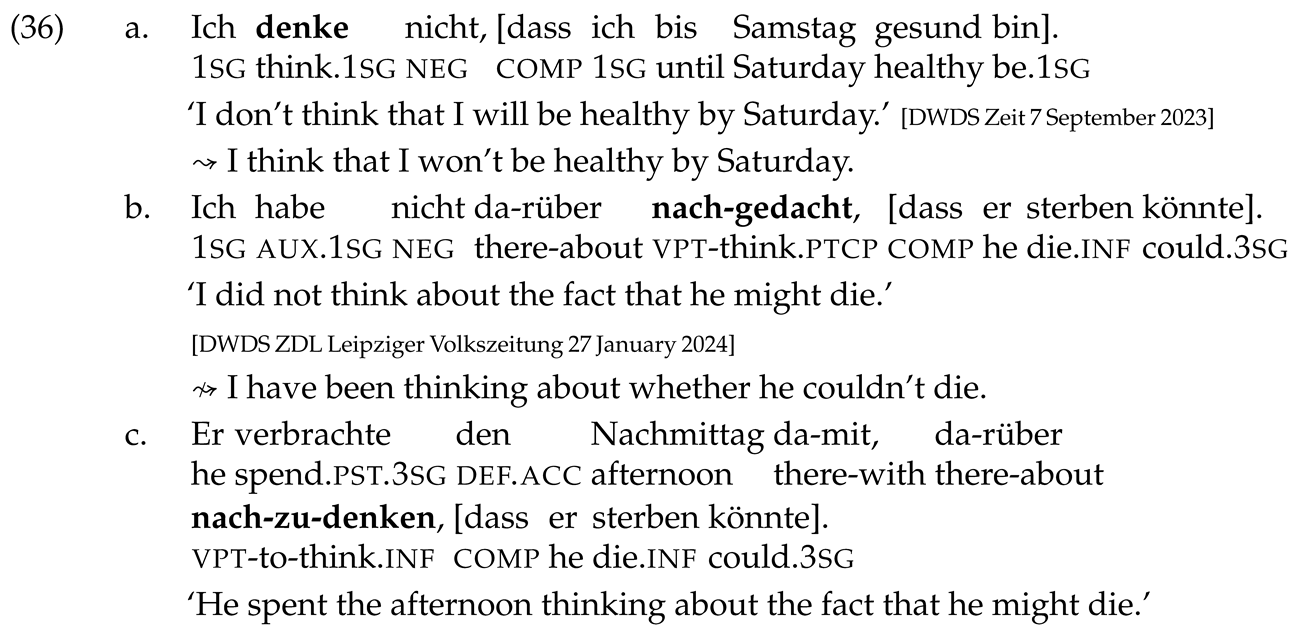

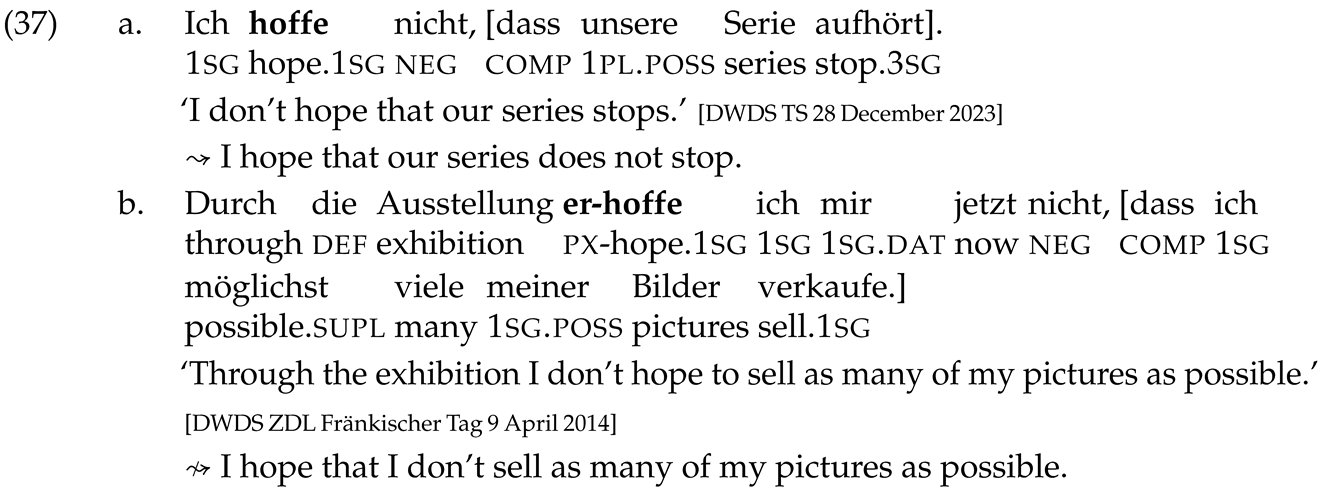

Another example of blocking of neg-raising by a preverb is er-hoffen ‘hope for’. German hoffen ‘hope’ is a restricted neg-raising CEV; neg-raising is attested here mainly with first person subjects (preferably in present tense) as in (37a). In an equivalent context (see (37b)), er-hoffen does not license neg-raising. Hoffen and er-hoffen are both stative; er- adds an inherently reflexive dative argument, yielding an interpretation that seems to further strengthen the preferential component of hoffen (for preferential predicates, see Anand & Hacquard, 2013; Harner, 2016; Uegaki & Sudo, 2019), which may explain the blocking of neg-raising.

One can also find cases in which a non-neg-raising CEV is turned into a neg-raising CEV. Er-warten would be a respective example, which is a neg-raising verb in its reading ‘expect’ (not in its reading ‘expect/demand from sb’; Stiebels, 2018). Its base verb warten ‘wait for sth’ is non-neg-raising due to its eventive character. The two verbs er-hoffen and er-warten show that the prefix er- can have opposite effects with respect to neg-raising.

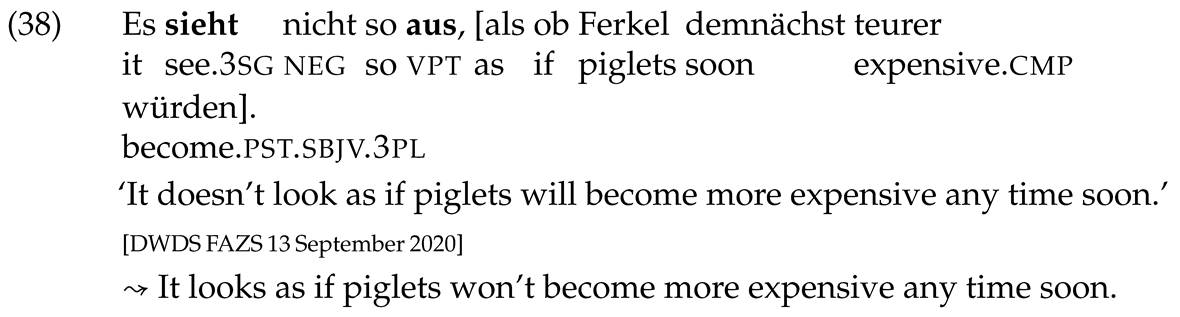

Another instance of feeding of neg-raising by a preverb can be found with aus-sehen ‘look like’ as in (38). Its base verb sehen ‘see’ does not belong to the class of neg-raisers.

Table 8 summarizes the patterns (‘±’: neg-raising is attested in a specific use of the CEV).

Table 8.

Examples for a shift of the neg-raising property (NR).

4. Specific Preverb Patterns in CEVs

In the previous sections, I have mentioned the following preverb patterns:

- Particle verbs with zu- ‘to’: addition of an addressee argument; transfer of information (see (3b)/(3c)/(24b)/(24c)).

- Deadjectival prefix verbs with er-: implicative verbs (see (16)).

- Prefix verbs with be-: applicative-like pattern licensing neg-projection; the clausal argument denotes the topic of utterance (see (13c)).

The three patterns differ in the size of the base verb class, with the zu-pattern exhibiting the largest domain of potential base verbs (verbs that may be used as verbs of communication) and the er-pattern the smallest domain (deadjectival verbs based on a subclass of adjectives denoting human propensity). I will further discuss the zu-pattern in Section 4.1 as a representative of a transparent pattern with a larger class of base verbs.

Although a full account of all relevant preverb patterns is beyond the scope of this paper (further research is necessary in order to account for all patterns), I would like to mention a few other patterns. The pattern I will discuss in Section 4.2 concerns a group of particle verbs with ein- that denote the attempted causation/induction of a belief state. The derived verbs are similar to ‘convince’ (German über-zeugen) but differ in the entailments regarding the belief state of the dative object referent. This preverb pattern is particularly interesting. Another (small) pattern I will focus on in Section 4.3 is a specific resultative pattern of er-; the interesting aspect here is the shift in propositional content.

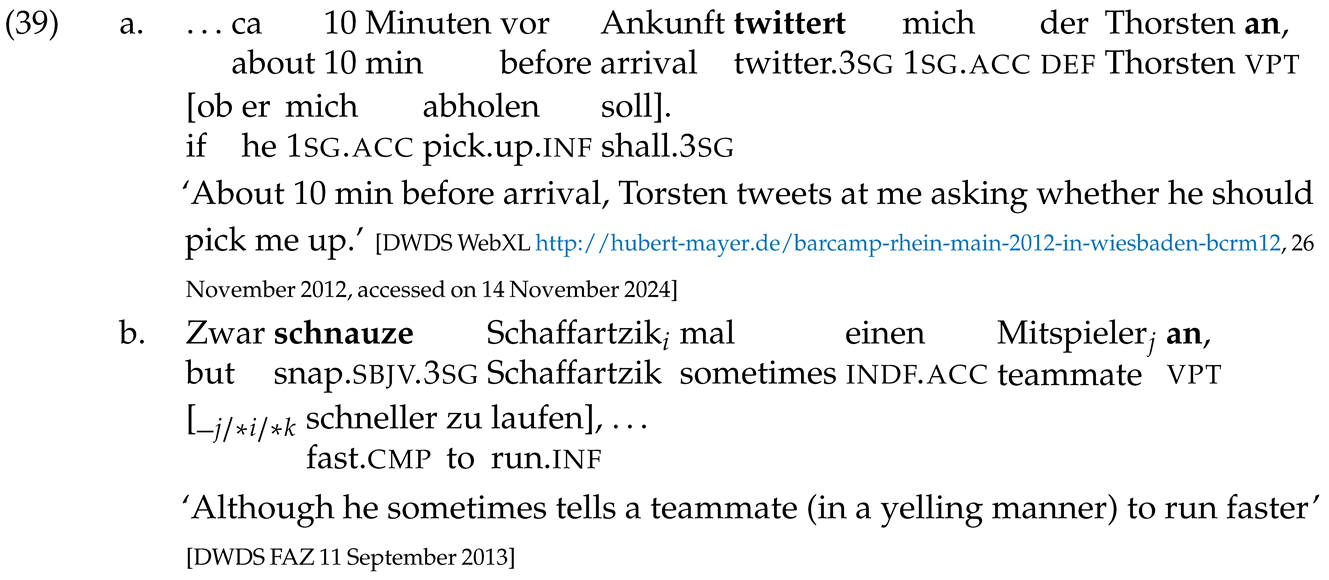

There is a pattern with the particle an- that has a larger overlap with the zu-pattern in terms of possible base verbs (manner of speaking verbs, certain sound emission verbs, general verbs of communication). Unlike the zu-pattern, the added goal argument is realized in the accusative. The preverb adds a directional meaning component (Stiebels, 1996). A further difference to the zu-pattern is the optionality of the clausal argument. With other base verbs, no clausal argument may be added (e.g., an-starren ‘stare at sth/sb’). Therefore, this is one of the few preverb patterns that is used both with CEVs and non-CEVs. These an-verbs also show some flexibility with respect to clause types. Example (39a) illustrates the verb an-twitter ‘send a tweet to’ with an interrogative complement and (39b) illustrates the verb an-schnauzen ‘yell at’ with an infinitival complement; these verbs display object control.

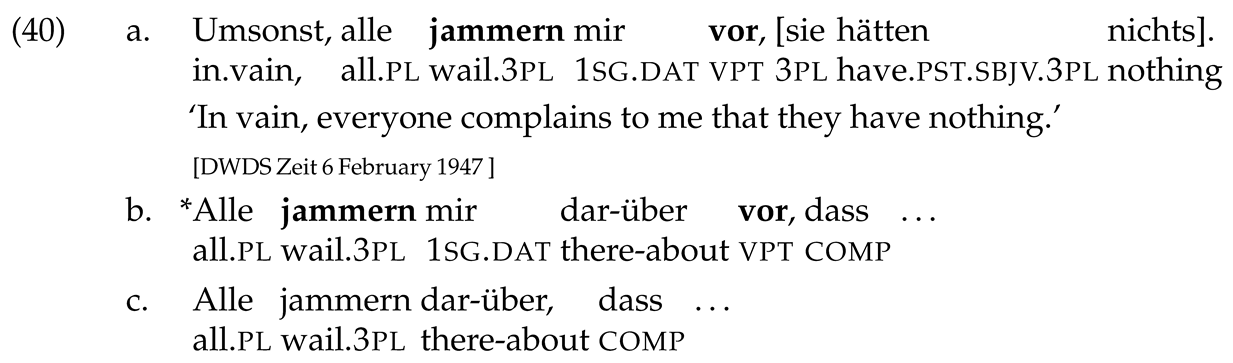

The final pattern to be mentioned involves two groups of verbs in combination with the verbal particle vor- ‘before, in front of’. There is a pattern of vor-verbs denoting deception and lying (e.g., vor-flunkern ‘tell sb a fib/fibs’, vor-lügen ‘lie to sb’, vor-schwindeln ‘lie to sb’, vor-täuschen ‘feign, fake’, vor-heucheln ‘feign, pretend’) in which the target of deception/lying is realized as dative NP/DP and introduced by the preverb. This other vor-pattern also introduces a dative argument and is attested with some sound emission verbs (e.g., vor-heulen ‘give sb a sob story’, vor-jammern ‘moan to sb’, vor-kreischen ‘screech in the presence of sb’), but also verbs like schwärmen ‘enthuse’ (vor-schwärmen ‘go into raptures over sb/sth’). The second vor-pattern is used as in (40a). The clausal argument has to refer to the content of the utterance. It is not possible to use these verbs with the sentential proform dar-über, which would trigger a shift in the propositional content to a topic of utterance reading (compare this to the simple verb jubeln ‘cheer’ in (13b)); (40b) is ungrammatical in contrast to the simple verb jammern in (40c).

The few vor-verbs of these two subgroups that are attested with infinitival complements exhibit subject control. Apart from the restriction to be used assertively, these vor-verbs and their base verbs do not differ in their clausal selection patterns.

4.1. Particle Verbs with zu-

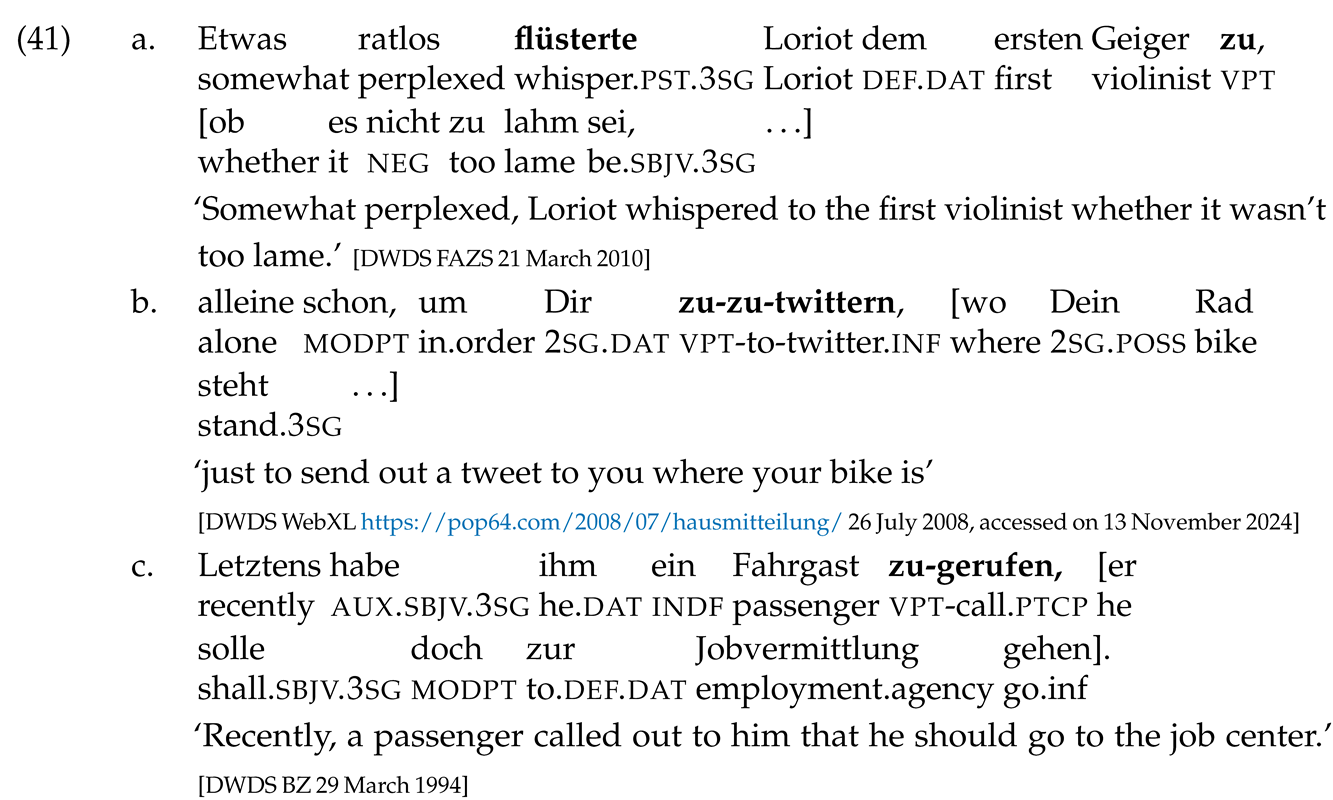

The CEV pattern with zu- was introduced with an example that demonstrates the selection of finite dass-clauses (see (3b)/(3c)). Recall that these verbs convey the transfer of information—with manner of speaking verbs, certain sound emission verbs and other verbs of communication as bases.15 I also showed that these verbs may take infinitival complements, exhibiting variable (structural) control (see (24b)/(24c)). This zu-pattern is quite flexible concerning the admissible clause types; the only restriction is the exclusion of nominalized complements since the clausal arguments refer to the content of an utterance, which blocks nominalized clauses. These verbs do not seem to license clausal arguments that refer to the topic of an utterance. Example (41a/b) illustrate interrogative complements and (41c) a V2-complement.

The pattern does not derive any raising or neg-raising verbs. Due to their assertive character, these verbs are not projective under negation.

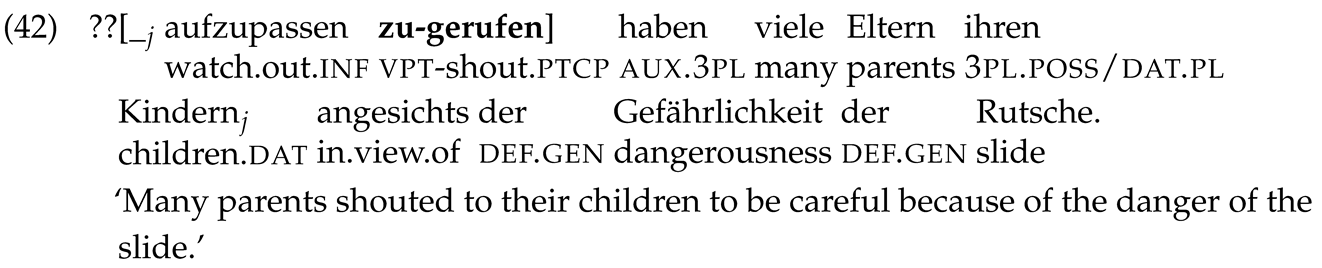

Although restructuring should be structurally possible, it seems to be disfavored. VP-topicalization, as in (42), seems highly marked and artificial. This may be due to the fact that infinitival complements as such are possible, though marked with this zu-pattern.

Table 9 summarizes the properties of this pattern (‘–’: structure is not possible, ‘?’ structure is questionable).

Table 9.

Properties of the zu-pattern.

4.2. Particle Verbs with ein-

Unlike other verbal particles, which show a transparent relation to a free lexical item, ein- is formally distinct from the corresponding preposition in ‘in’, both of which prototypically refer to interior neighborhood regions (see Olsen, 1998a, based on Wunderlich, 1993). This locative meaning is expectedly found with verbs of motion and (caused) change of location verbs. For further non-CEV patterns of ein-, I refer to the papers in Olsen (1998b).

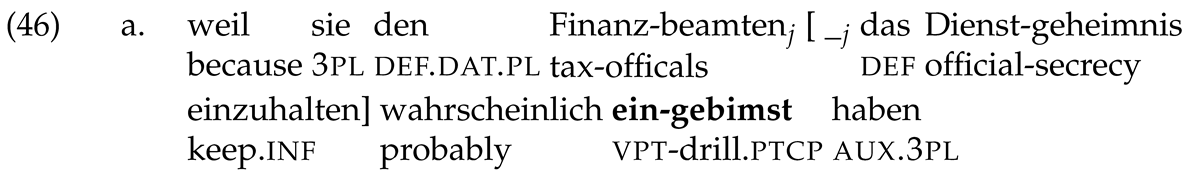

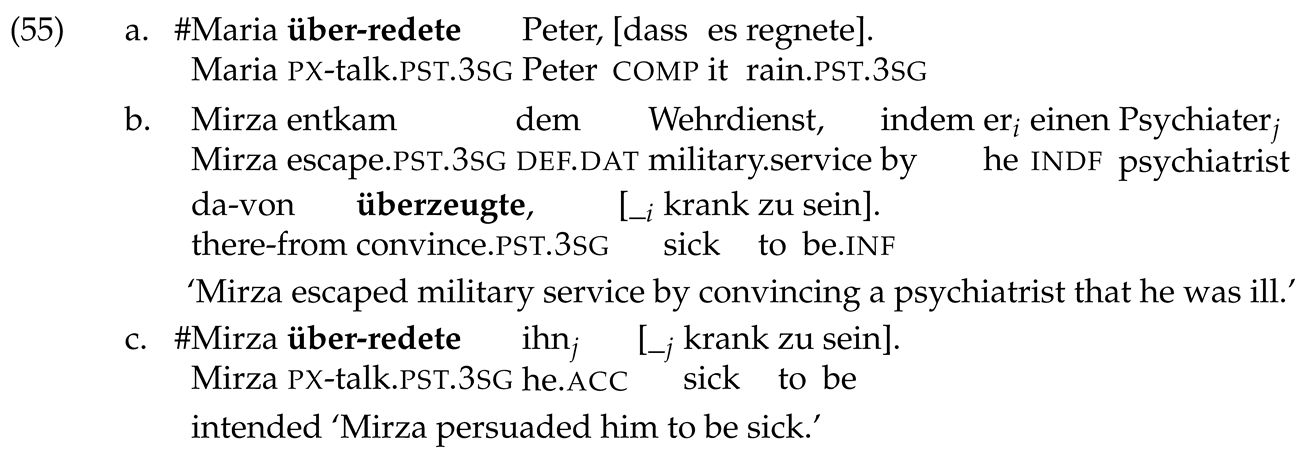

Not all CEVs derived with ein- fall under the pattern that I will illustrate in the following (e.g., sich ein-bilden ‘imagine’). The relevant semi-productive pattern derives CEVs that denote the (attempted) causation/induction of a belief state; sometimes, these verbs also obtain an epistemic interpretation (change of knowledge of the object referent). These ein-verbs are derived from verbal (e.g., ein-flüstern in-whisper), deadjectival (e.g., ein-schärf-en in-sharp-inf) as well as denominal bases (e.g., ein-trichter-n in-funnel-inf, ein-hämmer-n in-hammer-inf). The bases refer to the type of intense or extended manipulation (often in a metaphorical sense) that is used to establish the belief state in the object referent, which acts as a secondary attitude holder. These ein-verbs are canonically ditransitive (acc-dat-nom), thus differing from semantically similar verbs such as über-zeugen ‘convince’/über-reden ‘persuade’, which select an object referent in the accusative. Fehlisch (1998) mentions the denominal instances of these ein-verbs but discusses them only under the aspect of metaphorical extension and not with respect to their clausal selection properties; Witt (1998) focuses on the regular DP complements of these verbs. Note that there is a slight difference between the deverbal cases based on manner of speaking verbs (e.g., ein-reden (in-talk), ein-flüstern (in-whisper)) and the other ein-verbs. The latter show a stronger tendency for the clausal complements to refer to norms/rules/conventions, thus exhibiting some kind of hidden deontic modality.

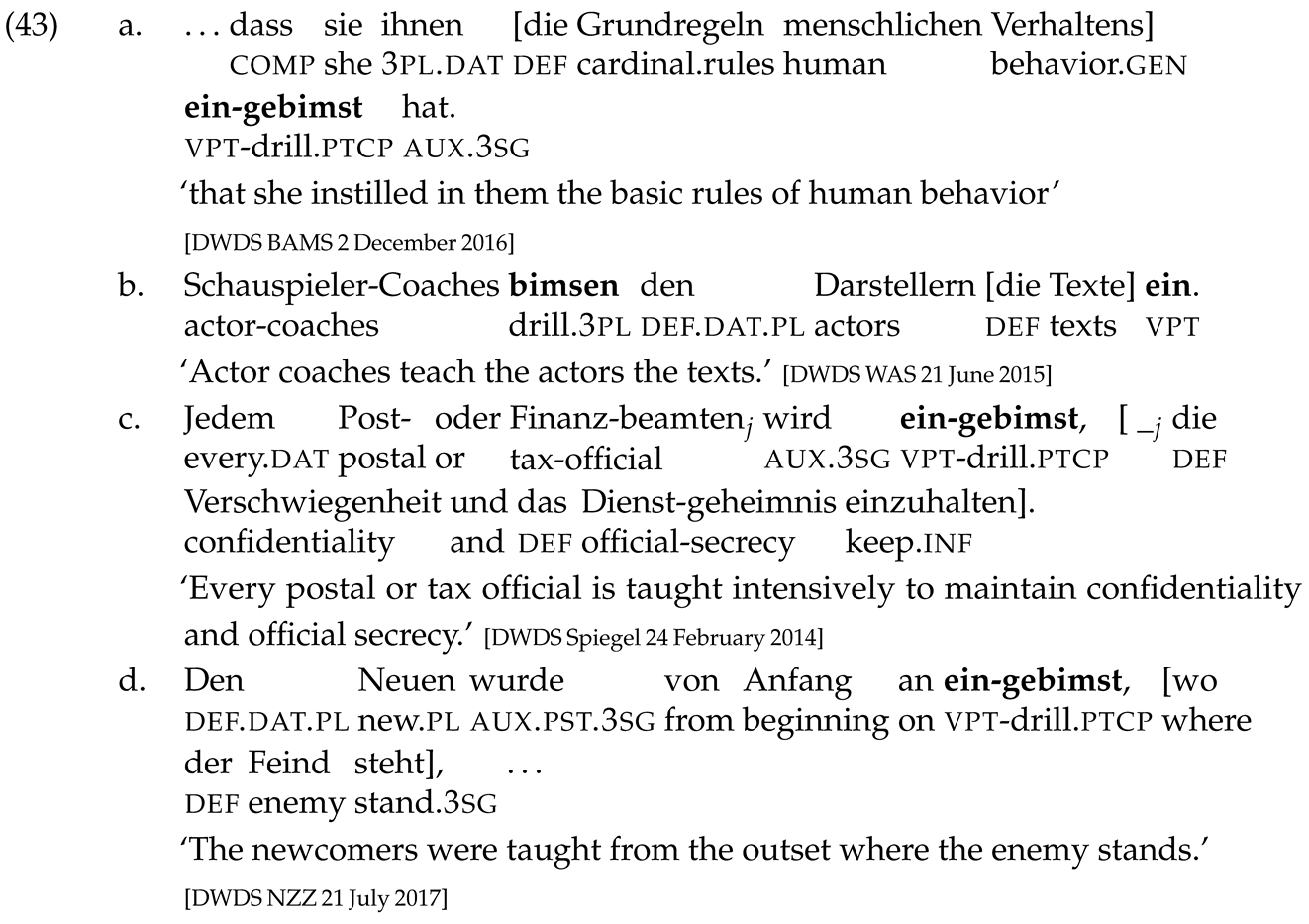

The basic properties of the pattern may be illustrated with the following examples: (43a–d) show uses of ein-bimsen ‘drum sth into sb’, which is derived from the verb bimsen ‘pumice, drill, bone up on sth’. It is attested with regular DP complements as in (43a/b) or clausal complements as in (43c/d). Note that the translations cannot do full justice to the specific contribution of ein-bimsen—the intensity of attempted manipulation.

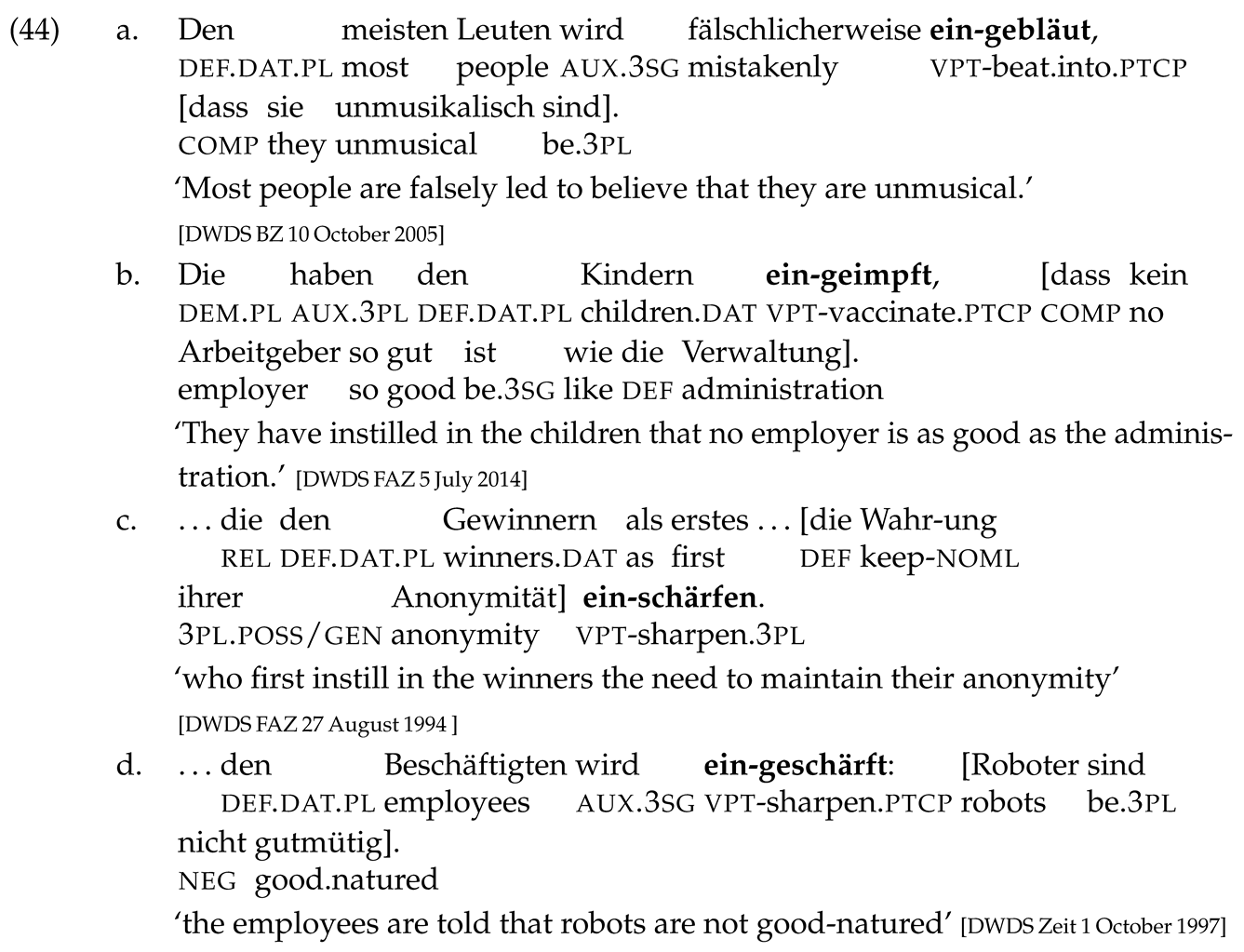

Besides infinitival complements as in (43c) and WH complements as in (43d), these ein-verbs most commonly occur with finite dass-complements as in (44a/b). Less common are nominalized complements as in (44c) and V2-complements as in (44d). All these data show that these ein-verbs are quite flexible in their complementation pattern.

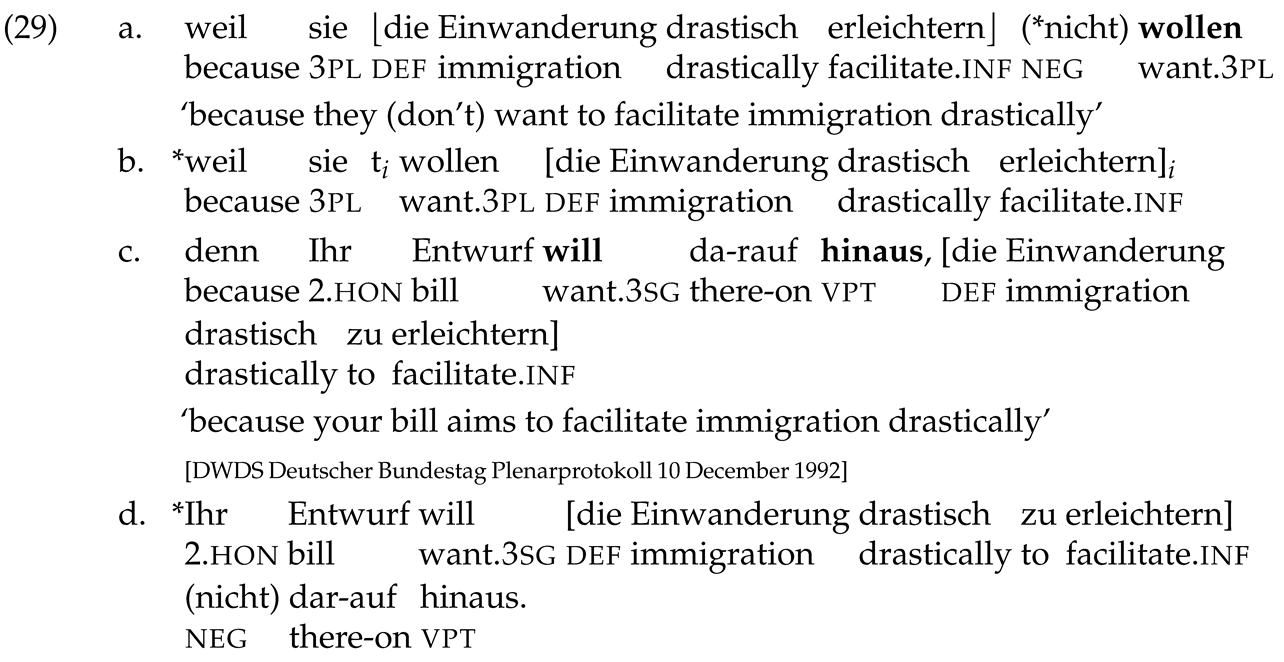

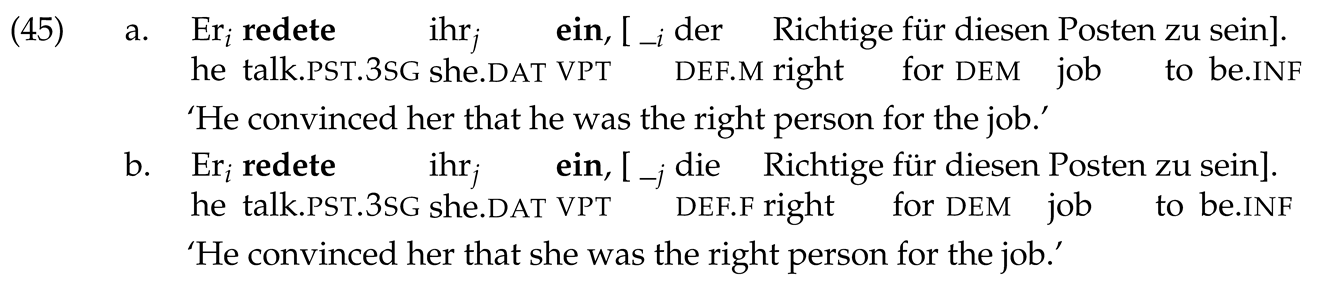

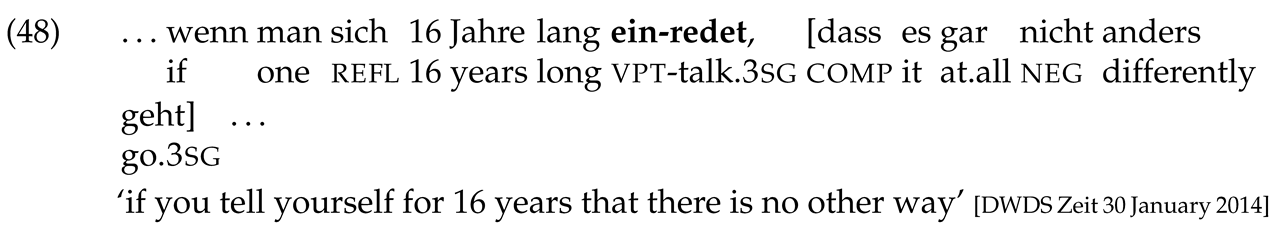

These verbs exhibit variable control with a strong tendency for object control, as shown in (43c) and (45b). Example (45a) shows that subject control is possible if this reading is enforced, e.g., by agreement (the definite masculine article). Moreover, they belong to the class of structural control predicates, as evidenced by the free reference of arguments in finite clausal complements (e.g., (43d), (44b/d)).

These verbs seem to disfavor (or even exclude) restructuring. Example (46a) shows a non-restructuring context (with an adverb intervening between the intraposed infinitival complement and the matrix verb); (43c) has already provided a context with extraposition. Example (46b) illustrates VP topicalization, which seems quite unacceptable. Structurally, restructuring should be possible. However, there seems to be clash between the preference for light VPs in topicalization and the requirement that infinitival complements of ein-verbs have to be specific enough to be acceptable.

None of these ein-verbs are used as raising or ECM verbs; furthermore, they do not allow neg-raising.

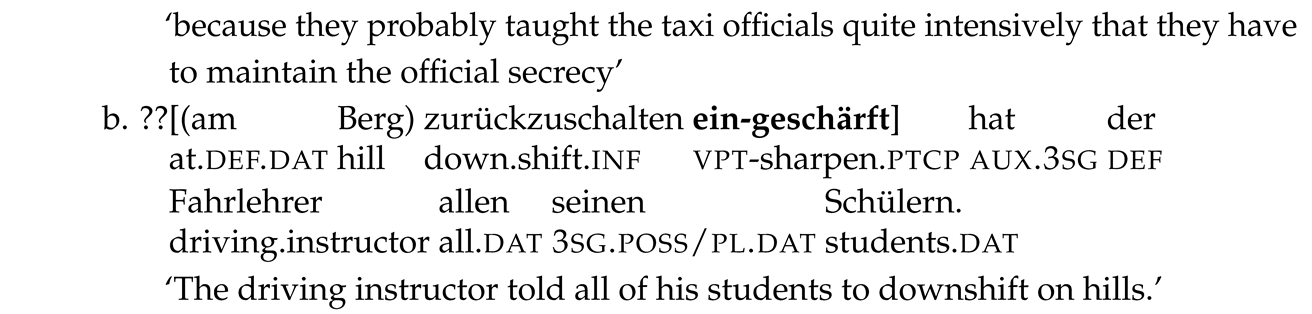

Generally, these verbs do not express a single act of manipulation but multiple/iterated acts of (attempted) manipulation of the relevant kind; this interpretation may be enforced with adverbial phrases such as ‘again and again’, see the corpus example in (47).

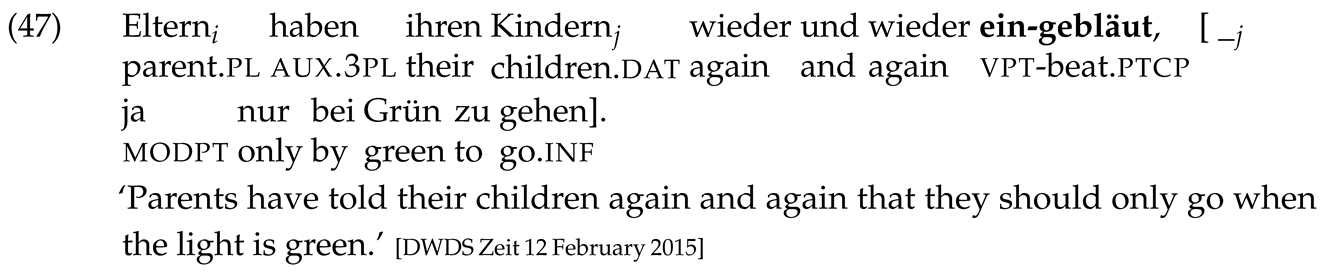

In line with this observation is the fact that these verbs may combine with durational adverbs as in (48); again, an iterative reading is induced.

With contextual support, these ein-verbs may also receive a telic interpretation:

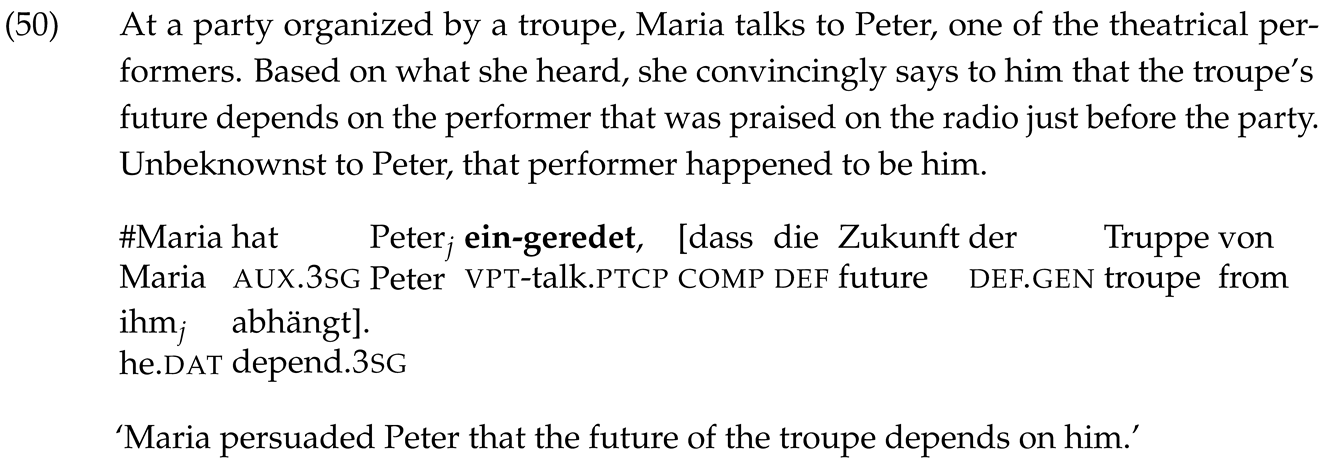

Parallel to über-reden ‘persuade’/über-zeugen ‘convince’, the object referents of these ein-verbs must be read de se (see Chierchia, 1989; Landau, 2015). In the context of (50) (taken from (Charnavel, 2019, p. 193)), which excludes a de se interpretation, these ein-verbs are not acceptable.

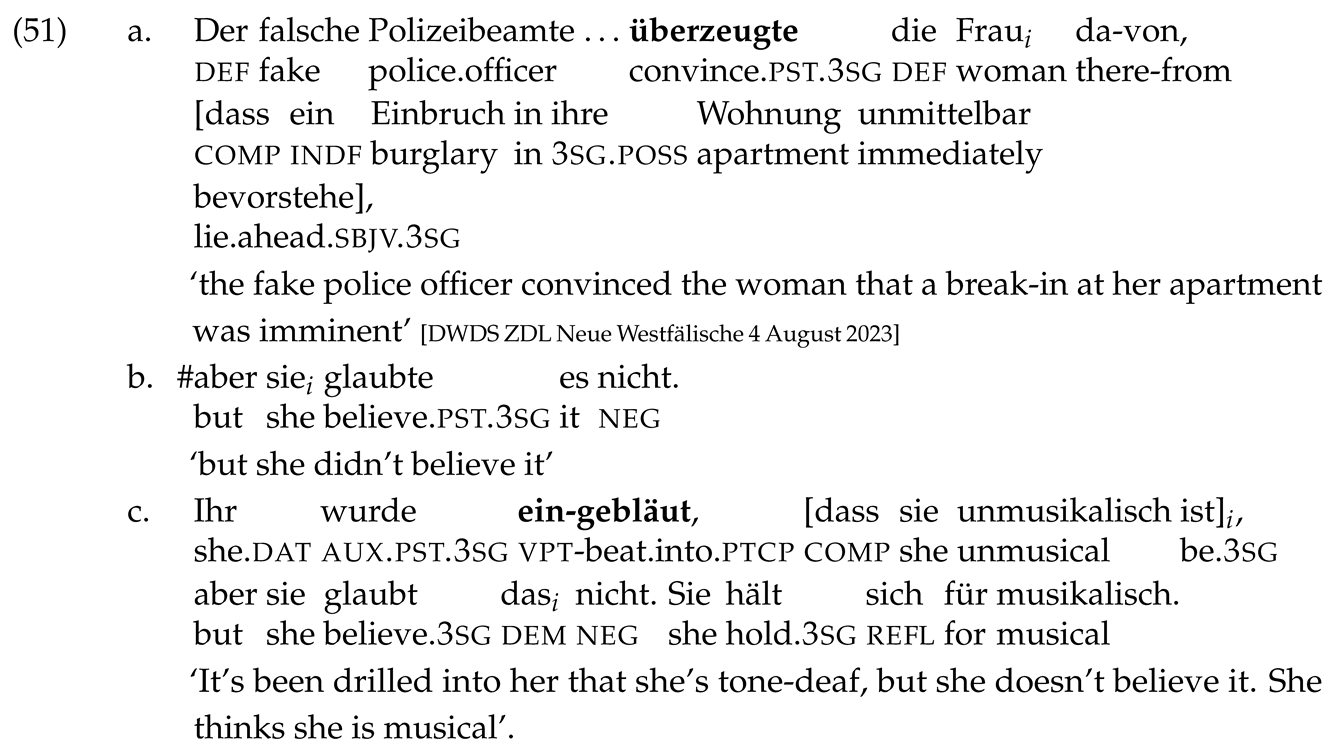

In contrast to über-zeugen ‘convince’, these verbs do not entail that the intended doxastic state (belief/knowledge) is instilled in the object referent. It is usually possible to continue the sentences with a statement that the object referent does not believe the proposition p (or has not learned the proposition p) without reaching a contradiction. This property classifies these verbs as a further subclass of “defeasible causative” verbs (Martin & Schäfer, 2012). Example (51a/b) demonstrate that it is semantically odd to continue (51a) with a sentence that states disbelief of the object referent in the case of über-zeugen (51b). For a verb such as ein-bläuen (and the other ein-verbs of that pattern), such a continuation is possible, as in (51c).

These ein-verbs are also not projective under negation:

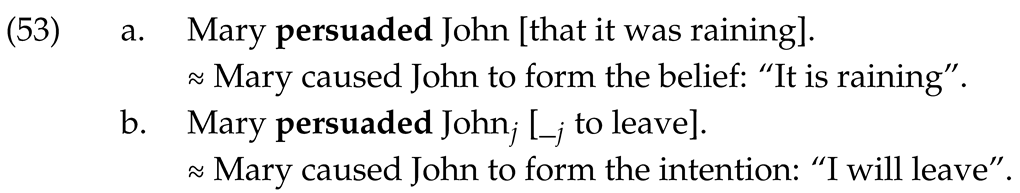

One final issue to be addressed is the question of whether these verbs participate in the belief–intent alternation (Grano, 2018; Jackendoff, 1985). The starting point is the observation for English that there is an interpretational difference with persuade (and also convince and certain other CEVs) depending on the type of clausal complement: Finite complements refer to beliefs as in (53a) and infinitival complements to intents as in (53b).

Example (54) shows that there is no entailment relation between the two readings.

Grano (2018) also showed that the verbs in question are not polysemous (using the Zeugma test) but select for a rational attitude complement, of which belief and intent are relevant instances.

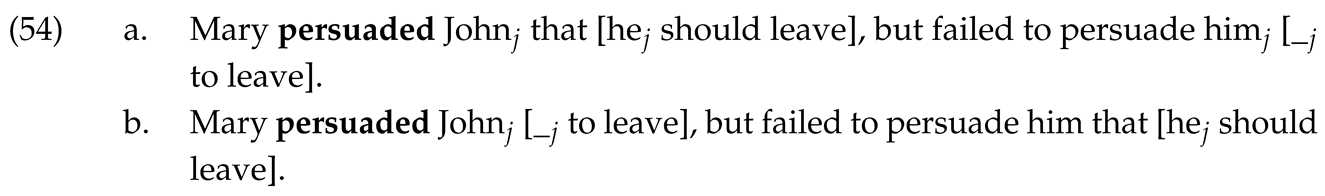

In contrast to English persuade, German über-reden ‘persuade’ does not participate in this alternation.16 Über-reden can only select actional (intent) complements. Example (55a) shows that the German equivalent of (53b) is unacceptable. German speakers would use über-zeugen ‘convince’ instead in such a context. Moreover, unlike über-zeugen, which may select for non-actional infinitival clauses as in (55b), such a complement is impossible for über-reden; (55c) could only receive the ironical reading that the person addressed by Mirza should pretend to be sick.

The ein-verbs parallel über-zeugen in allowing for both actional and non-actional infinitival complements (compare (45a) and (43c)). This means that the infinitival complement as such is not actional per se, but the default interpretation unless some embedded predicate triggers a different reading.17 Given that the ein-verbs are even slightly weaker than über-zeugen in terms of the intended and established belief states of the object referent, the intent reading with actional infinitival complements is more of an implicature that can be canceled.

Table 10 summarizes the properties of these ein-verbs (‘–’: structure is not possible, ‘?’ structure is questionable).

Table 10.

Properties of the ein-pattern.

4.3. Prefix Verbs with er-

The prefix er- has a very productive resultative use in non-CEVs, which was already illustrated above in (6b): the integration of a more or less abstract possessive relation. Besides this productive pattern, there are also several niche formations of er-. For instance, it is used as some type of resultative prefix in verbs of killing (e.g., er-würgen ‘strangle’, er-hängen ‘hang’) or as an inchoative marker (e.g., er-blühen ‘start blooming’, er-röten ‘flush, turn red’); see Stiebels (1996) for details.

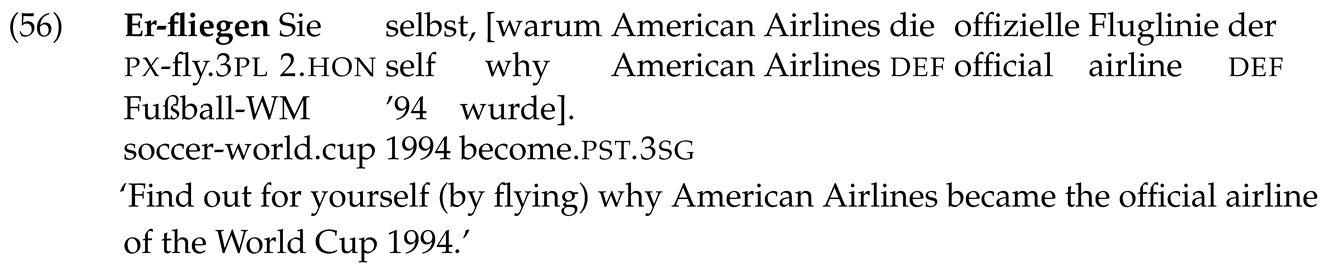

The example in (56) from an advertisement (reported in Stiebels, 1996, p. 129) demonstrates the extension of the resultative–possessive pattern to a reading in which the action denoted by the verb leads to an epistemic state (here, knowing the reasons for AA becoming an official airline in the World Cup 1994). However, this use is not attested frequently with non-CEVs as bases.

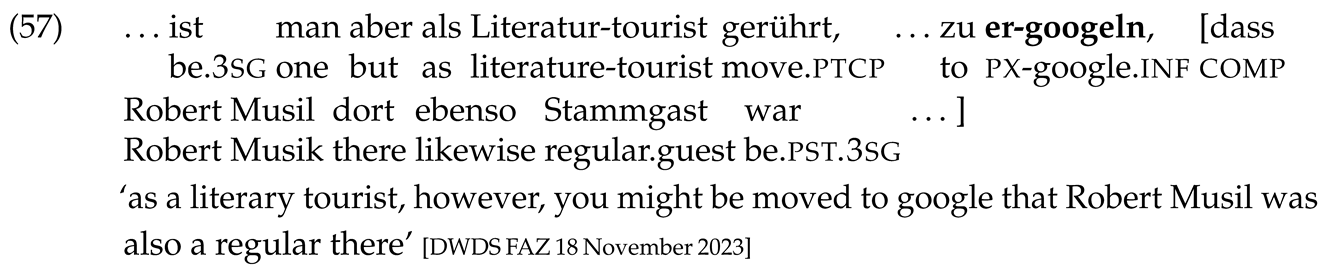

With CEVs, different, though related patterns emerge. The inchoative use is remotely related to the small class of implicative er-verbs mentioned in Section 3.1. The resultative–possessive use is related to a resultative use in CEVs, which can be found with verbs of inquiry/investigation. Example (57) illustrates a neologism with googeln ‘google’. Whereas googeln refers to the activity of doing internet searches and is mainly attested with interrogative complements, er-googeln exhibits a clausal argument that refers to the result of the internet search.

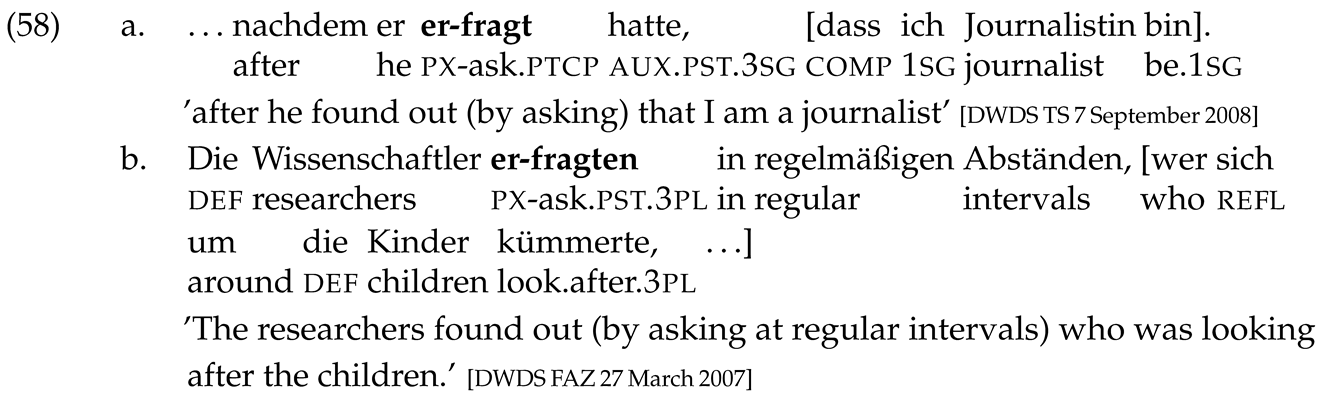

Similarly, er-forschen ‘explore’, er-fragen ‘enquire’, er-raten ‘guess’, er-lauschen (archaic) ‘listen’ and er-rechnen ‘calculate’ select for clausal complements that refer to the results of inquiry/investigation. This has the effect that these verbs—unlike most of their bases—may take dass-complements, illustrated in (58a) for fragen ‘ask’. Recall that fragen may take a dass-complement referring to the topic of inquiry (see (19a)). Example (58a) is different in that the clausal complement denotes the answer to the inquiry. This is also valid for WH-complements as in (58b); here, the interrogative complement has the use found in responsive verbs (e.g., discover who ...). Note that it is difficult to provide an elegant English translation of the examples that reflects the answering character of the clausal complement.

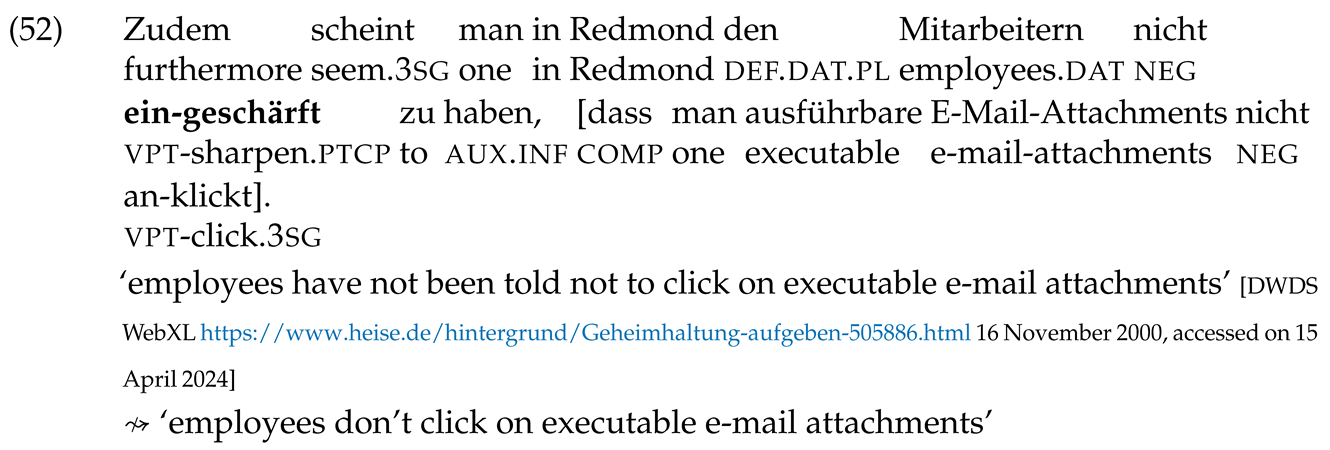

Besides dass-complements and interrogative complements, these verbs may also select nominalized clauses. The resultative nature of the prefix er- has the effect that the object (here, the clausal argument) is not optional—unlike their base verbs.

5. Conclusions

The preceding sections have demonstrated that German preverbs play an important role for clausal selection. They may affect, in principle, any semantic or syntactic dimension that is relevant for clausal embedding. In order to show this, I sometimes had to refer to highly idiomatic CEVs. This was specifically necessary for properties restricted to small and more or less closed classes of CEVs (raising verbs, neg-raising verbs). Diachronic studies could possibly reveal to what extent changes in meaning of the respective CEVs correlated with changes in syntactic properties of clausal embedding in previous stages.

That the shifts in clausal selection properties do not just represent a collection of lexicalized, erratic patterns could be demonstrated with the semi-productive (niche) patterns mentioned throughout the paper. Basic as well as derived verbs of speech/communication constitute the major base for preverb derivation in CEVs. With these verbs, only a subset of the potential changes in CEV properties can be observed (raising and neg-raising being excluded).

Some of the effects of preverb derivation occur as expected; this concerns mainly changes in argument structure/realization, which are relevant for control and restructuring. The changes in lexical aspect have a smaller effect (in the licensing of interrogative complements and in neg-raising). Other effects (e.g., regarding presuppositions and entailments) are hard to predict from what is known about preverbs in the non-CEV domain.

One aspect I did not specifically focus on in this paper is the role of the polysemy of the preverbs, which may already lead to distinct preverb patterns, and the polysemy of the derivatives. For instance, some derivatives of sehen ‘see’ are polysemous: ab-sehen (off-see) ‘ignore’, ‘refrain from’, ‘aim for’, ‘foresee’; nach-sehen (after-see) ‘check’, ‘not mind sb doing sth’; zu-sehen (to-see) ‘watch’, ‘see to it that’; vor-sehen (in.front.of-see) ‘plan’, ’take care not to do’. In the majority of cases, the readings correlate with distinct argument structures/argument realizations; often, the distinct readings also show a specific clausal selection pattern. It is worthwhile to study these cases of polysemy in more detail.

Another impression that one may obtain from the German preverb data and that would require a more systematic investigation is the observation that, sometimes, a simple verb and the corresponding preverb distinguish readings that are co-lexified in other languages. According to the CLICS database, ‘refuse’ and ‘deny’ (probably in the use deny sb sth) are often co-lexified. German distinguishes the two readings with (sich) weigern ‘refuse’ vs. (jemandem etwas) ver-weigern ‘deny sb sth’. Likewise, some of the derivatives of sehen ‘see’ exhibit readings that are reported as co-lexifications in other languages.

A relevant and interesting question is whether data from other languages will confirm the role of preverbs found with German CEVs or even show additional effects of derivational morphology for CEVs. The study of Slavic prefixes in complex CEVs seems to be a promising research topic given that these prefixes typically combine the lexical aspect with the viewpoint aspect; the latter is missing in German.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) as part of the subproject Optimal matches between clause-embedding predicates and their clausal complements in the

Research Unit 5175 Cyclic Optimization, funding no. STI 151/5-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers, the members of the project, Silvie Strauß and Xinran Yan, and the audiences of the workshop The aspectual architecture of the Slavic verb: analogies in other languages and other grammatical domains (Leipzig, November 2023) and the attendants of the poster session of the Mecore Closing Workshop (Constance, June 2024) for helpful comments and discussions. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Manfred Bierwisch (1930–2024), whose work and view on Lexical Semantics has been quite influential for me and who, though unbeknownst to him and rather indirectly, initiated the causal chain that made me end up writing a PhD thesis on complex verbs in German. Manfred was always very encouraging and helpful in the discussions we had.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations and interlinear glosses are used in this paper:

| Glosses | |||

| aux | Auxiliary | CEV | Clause-embedding verb |

| acc | Accusative | ZDB | ZAS database |

| comp | Complementizer | ||

| cmp | Comparative | DWDS | subcorpora: |

| dat | Dative | BZ | Berliner Zeitung |

| def | Definite | FAZ | Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung |

| dem | Demonstrative | FAZS | Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung |

| gen | Genitive | TS | Tagesspiegel |

| hon | Formal address | WebXL | Meta-corpus websites |

| (honorific pronoun) | |||

| indf | Indefinite | ZDL | Regional section of newspapers |

| inf | Infinitive | Zeit | Die Zeit |

| itj | Interjection | ||

| modpt | Modal particle | IDS (DeReKo) subcorpora: | |

| neg | Negation | mm | Mannheimer Morgen |

| noml | Nominalization | nun | Nürnberger Nachrichten |

| obl | Oblique case | ||

| prof | Sentential pro-form | ||

| pst | Past tense | ||

| ptcp | Participle | ||

| pl | Plural | ||

| poss | Possessive pronoun | ||

| px | Prefix | ||

| refl | Reflexive | ||

| rel | Relative pronoun | ||

| sg | Singular | ||

| sbjv | Subjunctive | ||

| supl | Superlative | ||

| vpt | Verbal particle | ||

Notes

| 1 | The ZAS database documents the clausal selection properties of 1807 predicates; these predicates were studied for attested clause types (finite dass-clauses, verb-second (V2) complements, interrogative complements and argument conditionals (Schwabe, 2015), infinitival complements, nominalized clausal complements and direct speech complements), verb mood in the complement clause, argument structure and argument realization of the clause-embedding predicate, controller and control shift in the case of control structures, and definiteness of nominalized clauses. The goal was to document these properties for all readings of the respective clause-embedding predicate. Attested forms were mainly taken from the DWDS corpus (https://www.dwds.de/, accessed on 20 February 2025) and the Mannheim German Reference corpus (DeReKo; https://www.ids-mannheim.de/en/digspra/corpus-linguistics/projects/corpus-development/, accessed on 19 November 2024), but see https://www.owid.de/plus/zasembed/docs/datacollection.html (accessed on 20 February 2025) for further information on data collection. The DWDS corpus is a collection of six meta-corpora, some “reference corpora” (balanced for genre and time periods), some newspaper corpora, some web corpora and some special corpora (see https://www.dwds.de/r (accessed on 20 February 2025) for a full list). Although the ZAS database already documents a very large class of clause-embedding predicates, it is by no means comprehensive. One can easily add further predicates, which, as far as I can see, would not change the picture of clausal selection properties. |

| 2 | Unlike verbal particles, which in most cases show a transparent relation to a free lexical item (adverb, preposition, adjective), verbal prefixes that do not relate to a preposition are rather opaque; therefore, I do not provide a translation for the opaque prefixes. |

| 3 | The prefix ge- is unproductive as a lexical/derivational morpheme. It is systematically used as a prosodically triggered prefix in the past participle. |

| 4 | In most cases, I will illustrate the patterns with corpus examples. Most examples are taken from the DWDS corpus or the ZAS database of clause-embedding predicates. The abbreviations for the subcorpora of the DWDS are given in the abbreviations section. If no corpus was specified, I created the example according to my native speaker judgments. I will sometimes simplify corpus examples that are too complex, leaving out words/phrases that are not relevant for the specific properties or interpretation of the respective CEV. The abbreviations for the glosses are listed in the appendix as well. I mark the covert subject of infinitival complements (=controllee, controlled argument) in a theory-neutral way with “_”. The specific formal syntactic representation is not relevant for the aspects addressed in this paper. |

| 5 | I include compositionality in the characterization of productivity in order to distinguish it from other “creative” uses of language, which may involve analogy, etc. |

| 6 | Evidence for zero case is taken from nominalized clausal complements. Unlike verbal projections, they cannot remain caseless. However, it is not always easy to decide whether a CEV excludes a nominalized clausal complement due to deficient case assignment or due to a semantic incompatibility of a nominalized clausal complement. There are pairs of semantically similar CEVs that differ in their case pattern: whereas sich weigern ‘refuse’ does not assign case to the clausal argument, ab-lehnen ‘refuse, reject’ assigns accusative to the clausal argument. The semantic similarity/equivalence of such minimal pairs makes a semantic explanation for the lack of a nominalized clausal complement less likely. |

| 7 | I agree that that-clauses (or dass-clauses in German) do not trigger a speech content reading. However, combining a non-CEV with a clausal complement usually leads to the effect that the meaning of the verb has to be shifted in order to allow it to be related to a proposition. |

| 8 | Troyke-Lekschas did not consider nominalized clausal complements (noml). |

| 9 | The case requirement for NPs has been attributed to a “case filter” (Chomsky, 1981) or a “visibility condition” for theta-marking (Chomsky, 1986); see also Markman (2010) for a historical overview on ensuing accounts for the distribution of NPs/DPs. |

| 10 | This is one of few cases in which an anti-rogative predicate is attested with an interrogative complement. Here, like in the other cases, it seems that there is a coerced reading involving a covert CEV sandwiched between the matrix CEV and the clausal complement, e.g., entscheiden ‘decide’, which licenses the interrogative complement. |

| 11 | Restructuring CEVs are not necessarily consistent in showing all relevant restructuring properties; see Wurmbrand (2001) for German. |