Abstract

A number of different language measures are used in child language acquisition studies. This raises the issue of comparability across tasks, and whether this comparability diverges depending on the specific language domain or the language population (e.g., monolinguals versus bilinguals). The current study investigates the comparability across tasks in the domains of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax in primary-school-aged sequential bilingual children with L1 Arabic/L2 English (N = 40, 5;7–12;2) and age-matched monolinguals (N = 40). We collected narrated speech samples to produce measures across language domains, and additional measures from separate vocabulary, morphology, and syntax assessments. Using a logistic regression analysis, we find a correspondence between syntax measures in monolinguals; however, we find no further correspondences in the other domains for monolinguals, and no correspondences at all in bilinguals. This suggests that assessment measures are highly task-dependent, and that a given assessment measure is not necessarily indicative of language as a whole, or even of language within a domain. We also find selective effects of age for monolinguals and both age and length of exposure (LOE) for bilinguals; in particular, while LOE predicts variation between the first and second language, age effects reflect underlying similarity across languages. We consider the implications of these effects for language assessments across populations.

1. Introduction

Different types of tasks use different metrics and measures to assess child language. This raises a key question of comparability across the different measures—that is, do they tap into the same underlying competence? This issue of comparability has important implications for the validity of different language assessments: if different assessments are designed to measure the same construct but produce different results, then the results cannot be linked to the intended construct (Devescovi & Caselli, 2007). This condition generalises across language assessments, but also across language experience: for example, two comparable tasks should produce similar results for monolinguals and similar results for bilinguals (Bedore & Peña, 2008; Armon-Lotem et al., 2015).

Many studies on monolinguals have investigated the relationship between tasks for assessing different constructs, e.g., the relationship between ‘lower-level’ vocabulary and grammar and ‘higher-level’ narrative macrostructure (Silva & Cain, 2019). These tasks tend to be normed with monolingual populations, without a formal comparison with bilinguals (Karem & Washington, 2021; Rothman et al., 2023); meanwhile, studies on bilinguals have focused more on relations between the assessments and individual difference factors (e.g., socio-economic status, home language) (Paradis, 2023; de Cat & Unsworth, 2023). Fewer studies have directly investigated the comparability of different measures within a single language domain (e.g., vocabulary, morphology, syntax), and for both monolingual and bilingual populations. In this study, we aim to address the issue of comparability by evaluating different language assessments which are designed to measure the same underlying linguistic competence in monolinguals and bilinguals.

For each language domain, we ask whether two tasks produce measures which correspond with each other for monolingual English-speaking children and for age-matched sequential bilingual children with L1 Arabic and L2 English. We compare the children’s behaviour on a series of (English) tasks across domains: the Renfrew Word Finding Test for vocabulary (Renfrew, 2023), TEGI morphology (Rice & Wexler, 2001), Colouring Book syntax (Pinto & Zuckerman, 2019), narrative Type–Token Frequency, VOCD, mean length of utterance, and syntactic complexity. Using logistic regression analyses, we find that the correspondence between tasks is generally absent—even within a language domain—for both populations. Rather, children’s behaviour is more consistently predicted by their age, or—for bilinguals—by their length of exposure to the second language (i.e., the language of assessment). This variability across tasks may be related to differences in how tasks measure the particular features, but are also associated with ceiling effects, particularly for monolinguals.

The article is organised as follows: in Section 2 we explore how children’s lexical, morphological, and syntactic proficiency has been measured in language acquisition research, as well as comparisons of children’s behaviour across tasks. Section 3 then explores these comparisons with bilingual populations. In Section 4, we present the current research questions and hypotheses, and Section 5 describes the participants and the different language tasks. In Section 6 and Section 7, we present the results and the discussion, and Section 8 concludes the study and raises possibilities for future research.

2. Language Assessment Measures

Approaches to language testing may be conceptualised as being on a continuum ranging from item-based tasks which aim to isolate discrete language skills or ‘single domains’ (such as vocabulary, morphology, and syntax), through to highly naturalistic language sampling, for example, recording the language used by children in conversation or free-play situations. Between these is narrative testing. Narrative testing may be described as ‘multi-domain’ testing. As in conversation and free play, children must simultaneously integrate aspects of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax within a single task; however, as with single-domain measures, potential content and structure can be purposefully targeted and, to some degree, controlled for.

To compare children’s behaviour on different assessments across language domains, the current study focuses on a single domain at a time and respective narrative tools/approaches to assessment. These approaches are outlined in the following sections for different language domains, followed by a review of previous comparisons across measures.

2.1. Single-Domain Testing

Multiple standardised and experimental tests of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax have been developed. These single-domain tests can be broadly classified as receptive or expressive (also categorised as comprehension and production, respectively). Receptive tests tap into the child’s understanding of the language target, and expressive, their production. The following sub-sections briefly outline options in each area.

2.1.1. Vocabulary

Standardised receptive options for primary-school-aged children include the British Picture Vocabulary Scale (BPVS; Dunn et al., 1997) and the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT; Dunn & Dunn, 2007). Receptive vocabulary tasks typically involve inferential reasoning and eliminating options from a test array that contains a closed set of possible responses. Correct responses on receptive tasks may also be possible via chance and/or weak or partial phonological or semantic word knowledge (Leonard, 2009).

Standardised expressive options include the Renfrew Expressive Vocabulary Test (Renfrew, 2023) and the Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT-3; Williams, 2019). Assessment typically involves asking children to name singular, pictorially represented concrete objects or action events without the above cues (Blom & Bosma, 2016; H. Cheung, 1996; S. Cheung et al., 2019). As standardised tasks test the same lexical items with each child, they are a generally reliable test of vocabulary proficiency across a participant cohort; however, this reliability may vary across cohorts with different acquisition experience.

For example, variation in the quantity of vocabulary in children’s linguistic input over the first 2 years of life was observed by Hart and Risley (1995) depending on socio-economic status (SES). This effect, which varied by up to 30 million words, has been widely cited as a source of variation by SES, with knock-on effects beyond vocabulary (Romeo et al., 2018; Golinkoff et al., 2019). However, the validity of this figure has been debated, depending on the operationalisation of linguistic input to children (Sperry et al., 2019; Dailey & Bergelson, 2022; Figueroa, 2024). In addition, the quantitative deficit-based framing of the issue has also been criticised for overgeneralising assumptions about development from Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) populations (for a review, see Kuchirko & Nayfeld, 2020). These critiques are beyond the scope of the current study, although we return to the issue of the linguistic input in Section 7.3.2. in the context of input in the second language.

2.1.2. Morphology

Tests of receptive morphology, independent of syntax, are limited particularly for early language development. For example, the standardised Test for Reception of Grammar (TROG-2; Bishop, 2003) may be used with children aged 4 years and above, and uses the same multiple-choice format outlined above for vocabulary. In the TROG-2, children select which of four images correspond with a sentence read aloud by the examiner, although only a small number of test items (e.g., those targeting plural noun inflections and negation) rely on accurate processing of morphological contrasts alone. Additional experimental measures have also been developed to assess tense morphology in 3-to-5-year-olds, with a similar forced-choice paradigm between dynamic event scenes (Carr & Johnston, 2001).

Expressive morphology (again, independent of syntax) is most commonly measured with elicitation tasks designed to provide obligatory contexts for use of a given morpheme (Berko, 1958; Blom & Bosma, 2016; Blom & Paradis, 2015; Chondrogianni & Marinis, 2011; Paradis & Blom, 2016; Snow & Hoefnagel-Hohle, 1978; Unsworth, 2016). Sentence cloze elicitation tasks feature in both the Word Structure sub-test of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—Fifth Edition (CELF-5; Wiig et al., 2017) and criterion-referenced tools like the Test of Early Grammatical Impairment (TEGI; Rice & Wexler, 2001), which create obligatory elicitation contexts as in (1):

This controlled elicitation context provides a direct test of a closed set of specific morphemes which may not occur naturally within samples of children’s spontaneous language. However, conversely, the controlled context may limit children to use of only the target morphemes and not reveal the true range of some children’s abilities. Furthermore, children may be successful in the controlled contexts due to the indirect modelling provided by sentence-cloze-type tasks, and because overall linguistic demands are reduced relative to natural discourse where children must integrate skills and knowledge across multiple linguistic levels (vocabulary, morphology, and syntax) (Botting, 2002).

| (1) | ‘this baby eats, this baby ___’ |

| (target = sleeps) |

2.1.3. Syntax

Standardised tests of syntax may also be classified as receptive or expressive. For example, the expressive task of sentence repetition (also described as sentence imitation) is used commonly in clinical contexts, with monolingual and bilingual populations (e.g., Chiat et al., 2013; Vinther, 2002). Sentence repetition has many advantages in that it is simple and quick to use, and target language structures can be constructed exactly as required (Chiat et al., 2013). The task draws on children’s ability to repeat verbatim what was just heard (Theodorou et al., 2017). However, this verbatim repetition still requires the language user to employ an analysis and reconstruction of the utterance rather than passively imitating the structure (Potter & Lombardi, 1990). These processes involve linguistic knowledge of the structure in question; however, they also rely on short-term memory, making it more difficult to disentangle the measurement of cognitive ability and language ability (Acheson & MacDonald, 2009; Polišenská et al., 2015).

Receptive assessments of children’s syntax may alleviate some of this cognitive load (the ‘production–comprehension asymmetry’; for a review see Valian, 2016). For example, picture selection is utilised in both standardised and experimental measures of children’s syntax, including the standardised Diagnostic Evaluation of Language Variation (DELV, Seymour et al., 2005), which involves a choice picture-matching task. For this task, which evaluates comprehension across a range of syntactic structures, participants are asked to choose the picture which best represents the sentence heard (Seymour et al., 2005).

Variation is also observed across picture selection tasks, however, which has been attributed to the specific demands of this task relative to other syntactic assessments (Adani, 2011; Pinto & Zuckerman, 2019; Marinis, 2010). In particular, subjects must hold a sentence in mind while comparing the sentence with the actions in a number of different pictures (Frizelle et al., 2019). Therefore, picture-selection tasks will be easier for individuals with greater memory capacity than for those with reduced memory capacity; thus—like for sentence repetition—working memory may prove a confounding variable (Marinis, 2010).

These demands may be mitigated in part by receptive tasks which use a version of the picture-selection task with just one picture for each test sentence (e.g., Adani, 2011; Friedmann et al., 2009; Roesch & Chondrogianni, 2016), thereby reducing the cognitive costs involved in processing multiple pictures per sentence. Instead of selecting between distinct pictures, such tasks involve a choice between items within the single picture, resulting in a lower processing demands due to fewer events in the task context (Pinto & Zuckerman, 2019; Gerard et al., 2018; Gerard, 2022). We therefore use this type of syntax assessment for the current study.

2.2. Narrative

Very broadly, children’s narratives or ‘stories’ can be personal or fictional. Fictional narrative tasks include both narrative generation and narrative retell. In retell tasks, e.g., ‘The Bus Story Test’ (Cowley & Glasgow, 1994) and the ‘Frog Stories’ (see Coughler et al., 2023), children are tasked with retelling a story immediately after an initial narration by the examiner. In generation (or elicitation) tasks, children are tasked with creating their own story; examples include the ‘Peter and the Cat’ Narrative Assessment (Leitão & Allan, 2003) and the Edmonton Narrative Norms Instrument (ENNI; Schneider et al., 2006). Within both types of tasks, narration may be supported by a series of illustrations or a wordless picture book, which control, to some degree, for content. This can be useful in reducing variation between subjects and enabling more valid comparisons to be made across a cohort, particularly for smaller speech samples (Rocca, 2007; Granger, 2011).

Relative to assessment targeting other linguistic domains, narrative generation ‘storytelling’ tasks have high clinical validity (e.g., in the identification of language disorder; Boerma et al., 2016; Henderson et al., 2018), and are most representative of the majority of spontaneous language used by children in naturalistic contexts (Peterson, 1990; Schneider et al., 2006). Storytelling, as an interaction pattern, is also more likely to be familiar to children from a range of cultural and linguistic backgrounds (Van Hell et al., 2003), making it particularly suitable for bilingual children. Narration also requires children to draw on and integrate the aforementioned linguistic features and domains of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax (Botting, 2002; Gillon et al., 2023) and can be efficiently used to assess for multiple linguistic features within a single task—i.e., it is a multi-domain assessment tool.

For the purposes of assessing across children and populations, fictional narrative generation may provide a good compromise between highly individualised but ecologically valid personal narratives elicited during free play or conversation, and highly controlled but decontextualised standardised and item-based assessment of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax.

Measures of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax may be elicited from narrative samples through completing a microstructural-level analysis. Common measures for vocabulary include Number of Different Words (NDW), Type–Token Ratio (TTR), and VOCD. Measures of morphology and syntax include mean length of utterance (MLU), percent grammatical utterances (PGU), and complexity index (CI). For this study, we include a comparison of TTR, VOCD, MLU, and CI, discussed further in Section 5.2.2.

Although the advantages are many and now well-documented, narrative elicitation techniques also have some limitations. More confident and extroverted children may be able to give fuller descriptions of the story pictures, therefore affording them higher scores. Typical developmental trajectories have not yet been established for all of the above measures, and opportunities for assessing comprehension or more complex sentence structures may be limited. Although language production measures can tap the underlying understanding of the target structures to some extent, they may not provide explicit presentation of the comprehension of sentence structures. Therefore, production tasks may not provide a full depiction of the individuals’ linguistic proficiency (Valian, 2016).

2.3. Relations Between Measures

With a range of tasks available for assessing proficiency in different language domains, a key question is comparability across measures—that is, are measures of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax elicited via targeted items within single-domain assessment comparable to those elicited via a multi-domain narrative assessment? This issue has been addressed for the domain of vocabulary in particular, and also for relations between different tasks across domains (Silva & Cain, 2019). However, fewer studies have directly investigated how measures of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax might differ based on the elicitation task type—that is, how standardised item-based testing such as that outlined in Section 2.1 versus more naturalistic narrative testing such as that outlined in Section 2.2 might impact results (Murphy et al., 2022).

In an early study, Ukrainetz and Blomquist (2002) investigated the concurrent relationship(s) between vocabulary measures obtained from four standardised, item-based vocabulary measures (the PPVT-3, the EVT, the ROWPVT, and the EOWPVT; see Section 2.1.1) and a three-part language sample for children aged almost 4 to 6 years. The language sample comprised conversation, expository and narrative elements; the latter elicited using a wordless picture book from the frog series (Mayer, 2003). The strength of relationships between each of the tests and the language sample vocabulary measure, NDW, ranged from weak to moderate. Across-assessment differences were attributed, in part, to the role of context in performance. This was not seen as undesirable; rather, findings highlighted the value of bringing together different types of vocabulary assessment in determining children’s ability to adapt to situational variation. Thus, different tasks may assess different aspects of a construct. Moving up linguistic levels, Guo et al. (2019) focused on the morphosyntactic level with a comparison of PGU calculated from ENNI (Schneider et al., 2006) transcripts and CELF-3/CELF-P Recalling Sentences (in Context) sub-test raw scores. Significant and strong positive correlations were reported for children aged 4 to 9 years, suggesting that grammar may be less susceptible to task and situational influences.

Looking across domains, a number of correspondences have been observed for different tasks. For example, Ebert and Scott (2014) investigated two groups, children aged 6 to 8 years and children aged 9 to 12 years. Children were from more diverse backgrounds, and language abilities ranged from very impaired to within the average range. Narratives were again obtained from the frog series. Standardised metrics were 11 norm-referenced sub-tests (e.g., the Formulating Sentences sub-test of the CELF-4) and categorised by the authors as word-, sentence-, or discourse-level. Different results were reported for the younger versus the older children. For the older children, the only significant correlation was for narrative sample TNW and discourse-level GORT (reading) comprehension scores, while for the younger children, narrative sample MLUs and subordination index (SI) were significantly correlated with multiple word- and sentence-level standard scores. Consistent with Guo et al. (2019), grammatical errors were also comparable across task types. Meanwhile, strong word-level skills supported a range of sentence-level tasks including sentence repetition and construction. Changing findings as a result of age were posited to be due to ceiling effects on the narrative task and highlighted the importance of selecting a task type that did not constrain children’s abilities. Owens and Pavelko (2017) subsequently compared MLUs, TNW, Clauses Per Sentence (CPS), and Words Per Sentence (WPS)—elicited via a conversational language sample—with the results of three CASL (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999) sub-tests for children aged ~3 to 7 years. Statistically significant relationships were reported for both MLUs and WPS and the Syntactic Construction (SC) sub-test.

Similarly, Murphy et al. (2022) compared vocabulary and grammar measures obtained from a narrative sample (the Test of Narrative Language, TNL; Gillam & Pearson, 2004) to those obtained from norm-referenced tests (including the PPVT and the TEGI Past Tense and Third Person Singular probes; see Section 2.1.2 above for a description) for children aged ~6 years. Significant relationships were reported for narrative sample MLUs, NDW, and PGU and all norm-referenced test scores; however, the strongest across-task relationships were for those using the PGU narrative measure. PGU may be particularly useful in capturing a range of syntactic and morphological difficulties and therefore potential language disorder.

Finally, Gillon et al. (2023) took a broader approach in comparing composite CELF-P2 core language scores, with a range of measures obtained from a novel, digitally presented oral narrative (story retell) task administered to 5-year-old children. Adding to the robustness of morphosyntactic measures, narrative error composite scores—omitted morphemes and word-level errors such as pronoun errors—were moderately correlated with the CELF-P2 scores.

3. Monolingual and Bilingual Differences

The studies outlined in the previous section differ in terms of participant cultural and linguistic background; however, this aspect was not specifically controlled for, and studies were overall skewed toward monolingual cohorts. Worldwide, more than 50% of children now speak two or more languages (Baker, 2011), meaning that a more nuanced understanding of bilingual children’s language test profiles is warranted. For example, comparable measures across tasks must be comparable across populations. The current study was therefore also interested in how an additional variable—bilingualism—might interact with task type and how this might vary or hold across the domains of vocabulary, morphology, and syntax.

Multiple studies (e.g., De Lamo White & Jin, 2011; Karem & Washington, 2021; Rothman et al., 2023) discuss the limitations and risks of using standardised assessments, normed on monolingual populations, with bilingual children. For example, standardised tests of vocabulary which limit bilingual children to use of just one language do not give credit for distributed vocabulary, i.e., where a word label is known in one language but not the other (Anaya et al., 2018). Numerous studies (e.g., Hadjadj et al., 2022) purport that narrative elicitation contexts are less likely to disadvantage bilingual learners in this way because they give more freedom to select from a range of suitable vocabulary. Scoring guidelines for standardised tests of morphology and syntax do not typically allow for cross-linguistic influences or dialectal variation, meaning that language differences may be wrongly interpreted as ‘errors’, resulting in lower scores in this domain also (Karem & Washington, 2021). The general format of item-based testing procedures—highly structured and based on the interaction pattern of pointing to pictures—may also be less familiar to some bilingual children, while storytelling tends to be common across languages (Laing & Kamhi, 2003). Furthermore, the majority of English tests do not include bilingual children in the norming sample (Ebert & Pham, 2017). Collectively, these factors may result in different patterns of across-task performance as a function of language-learning status (i.e., monolingual or bilingual).

A growing number of studies have compared bilingual children’s performance across task types (i.e., single-domain vs. multi-domain narrative). These have been primarily targeted at enhancing the ecological, criterion, and/or diagnostic validity (i.e., classification accuracy) of a range of narrative assessment measures (e.g., Wood et al., 2021; Bonifacci et al., 2020) for bilingual children with language disorder (LD) (e.g., Bonifacci et al., 2020). Few to none to date have used a two-group/four-factor design and compared monolingual and bilingual children on task type for vocabulary and morphosyntax measures specifically within the same study.

Focusing on bilingual children only, Wood et al. (2021) reported a strong positive correlation between NDW used by Spanish–English bilingual children during English retells of animated stories and PPVT-4 raw scores. A standardised expressive vocabulary test that would have allowed for more direct comparisons within the vocabulary domain was not administered. Ebert and Pham (2017) somewhat replicated Ebert and Scott’s (2014) findings with Spanish–English bilingual 5- to 12-year-olds. Moderate positive associations between standardised test results and narrative sample measures of vocabulary and morphosyntax were found for younger, but not older children.

Given the well-documented need for caution around use of standardised assessments with bilingual populations, these reported correlations across assessment type, and how they might vary as a function of age, are of much interest. This review of different language measures demonstrates how language tasks can vary greatly in terms of how the feature is measured. These differences can influence the specific measure of language outcomes, and therefore, divergent results may manifest depending on the language measure used. The current study aims to contribute to this understanding by directly comparing language measures and by investigating measures across domains as well as language populations.

4. The Current Study

4.1. Research Questions, Hypotheses, and Predictions

In this study, our general research question concerns the link between language measures and linguistic competence; in particular, to what extent do different measures of children’s language proficiency tap into the same underlying linguistic competence? We focus on semi-structured narratives and highly structured item-based assessments, and apply this general question to two key specific contexts:

- To what extent does the construct validity of semi-structured narratives vs. highly structured item-based assessments vary depending on the language domain (vocabulary, morphology, syntax)?

- To what extent does the correspondence (or lack thereof) between language assessments highlight a difference between language populations (sequential bilingual versus monolingual)?

To address these two questions, we will consider two sets of hypotheses and respective predictions.

4.1.1. Hypothesis Set 1: Language Domains

One hypothesis is that the different measures of children’s language proficiency in a particular domain do indeed measure the same underlying grammatical knowledge for both monolinguals and bilinguals. If so, this reliability may be observed in just one domain or for multiple domains. This predicts that—within a given domain—children’s proficiency on narrative measures will correspond with their proficiency on item-based measures. In particular:

- lexical diversity in a narrative task will predict lexical proficiency in the standardised Renfrew task, and

- measures of morphological complexity (e.g., MLU) in the narrative task will predict accuracy on the standardised TEGI task, and

- measures of syntactic complexity (e.g., complexity index) in the narrative task will predict children’s syntax comprehension in experimental tasks.

Alternatively, these measures of language proficiency measure the same knowledge for some domains, but not others—again, with the same pattern for monolinguals and bilinguals. In this case, we would predict one or two of the above associations, but not all three.

Finally, if the different assessments do not measure the same underlying knowledge for any language domain, then we predict none of the above relations between assessments—neither for monolinguals nor bilinguals.

4.1.2. Hypothesis Set 2: Language Populations

The above hypotheses may be true for monolingual language acquisition, sequential bilingual acquisition, or across both types of acquisition contexts. In these cases, we would predict the above correspondences for monolinguals, sequential bilinguals, or both populations, respectively. However, if the assessments do not measure the same underlying knowledge for either population, then none of the above correspondences are predicted for any of the three domains.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Participants

The participants were 40 typically developing sequential bilingual children (5;7–12;2, mean = 8;5.22, SD = 1;10.26) from L1 Arabic-speaking backgrounds acquiring English as an additional language, and 40 monolingual English-speaking children (5;3–10;6, mean = 8;5.26, SD = 1;7.10). Participants were residents in Northern Ireland and attended mainstream school with English as the language of instruction. Age of L2 onset for the bilingual children ranged from 5 months to 10 years old (mean = 4;10.08, SD = 2;7.03), and length of L2 exposure ranged from 7 months to 10;6 years (mean = 3;6.29, SD = 2;1.15). The bilingual participants spoke Arabic as a main language at home (as reported by their own parents or teachers), and they, or their parents, originated from thirteen different Arabic-speaking countries.

5.2. Procedures

To compare children’s behaviour across methodologies and language domains, we used item-based and narrative tasks across the three language domains (vocabulary, morphology, and syntax). We describe the item-based and narrative tasks in the following sections: these include three separate item-based tasks (i.e., one domain per task) and one narrative task which allowed for measures across domains. Children completed all four tasks in a single testing session with a constant order of presentation, with breaks taken as needed. The experimenter, a native speaker of Northern Ireland English, facilitated all four tasks across all participants.

5.2.1. Item-Based Tasks

Vocabulary

The item-based assessment for vocabulary was the Renfrew Word Finding Vocabulary Test (Renfrew, 1995). This is a standardised test evaluating children’s expressive vocabulary skills. This assessment employs a discrete, convergent, picture-naming method, which is a common instrument type used in evaluating children’s vocabulary size and involves testing responses to a sample of words which occur within a specific frequency range (Nippold, 2016; Read, 2007). The Word Finding Vocabulary Test comprises 50 line-drawn pictures of objects (nouns) arranged in order of difficulty. The pictures are shown to the participant one by one, and they are asked to name each item, after which responses are scored. The discrete approach employed by this assessment is selective and measures the individual’s knowledge of specific word meanings as independent constructs separate from other features of language competence and without contextual information (Read, 2000). Participants were scored as either correct (1) or incorrect (0) for each of the 50 lexical items tested. Each trial was entered into the dataset individually (i.e., not as an average or composite score).

Morphology

For morphology, we used the Test of Early Grammatical Impairment (TEGI; Rice & Wexler, 2001) to assess children’s production of the third person singular and regular and irregular past-tense morphology in English via elicitation. In particular, the TEGI assessment uses picture elicitation probes requiring participants to produce sentences using words with the target morphological features.

First, the third person singular probe evaluates the participants’ use of /-s/ or /-z/ on present-tense verbs. This probe includes a practice item followed by 10 test items. Each item shows a picture of a person who has a specific occupation (e.g., a teacher) and who is carrying out their job in the picture, with a prompt as in (2):

The target response in (2) includes a correct use of the third person singular, while incorrect uses include omission (e.g., ‘teach’) and incorrect forms (e.g., ‘teacher’). Responses were scored as correct (1) or incorrect (0) depending on whether the correct suffix was used.

| (2) | Investigator: Here is a teacher. Tell me what a teacher does. |

| Target response: A teacher teaches. |

Similarly, the past-tense probe evaluates the subject’s use of both regular (/-d/ or /-t/ final word phonemes) and irregular past-tense forms of verbs. This probe includes two practice items followed by 18 test items (10 regular, 8 irregular). Each item presents two pictures showing the same character but in two different scenarios: in the first, a character is doing an action; in the second, the character has completed the action. The past tense is elicited with a prompt as in (3):

As for the third person singular, participants’ responses were scored as either correct (1) or incorrect (0), and each trial was entered into the dataset individually.

| (3) | Investigator: Here, the girl jumps in the puddle. Now she is done. Tell me what she did. |

| Target response: She jumped in the puddle. |

Syntax

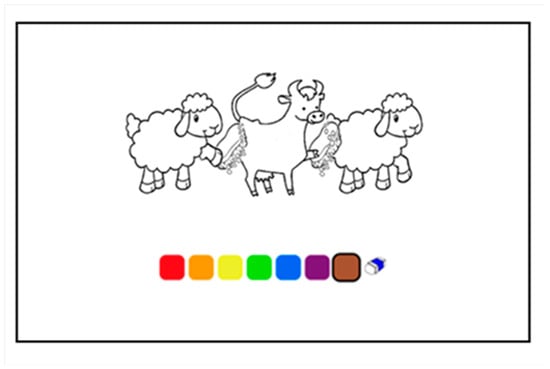

While the item-based tasks for vocabulary and morphology involved production measures, we used a comprehension measure to assess a range of syntactic structures: the Colouring Book Task, a digital colouring paradigm completed on a touchscreen PC (Pinto & Zuckerman, 2019; Zuckerman et al., 2016). In the Colouring Book Task, target structures are assessed by using the test sentence as a prompt to colour in a black and white picture; participants’ interpretations are then inferred based on how they colour in the pictures.

For each trial, children were presented with a black and white picture (Figure 1) with three animal characters performing the same action on each other, with one character as an agent (doing the action), and one as a patient (receiving the action), and one character as both an agent and patient.

Figure 1.

Sample item from the colouring task.

Children indicated their interpretations by colouring one character, based on the test sentences in (4) and (5).

The sentences in (4) and (5) vary in their clausal embedding (with embedding in (5)), and in canonical word order (with non-canonical order in (4b) and (5b)). This second contrast—between the (a) sentences and (b) sentences—is generally attributed to complexity (e.g., Bowerman, 1979; Caplan & Waters, 2002; Diessel, 2004; Lust et al., 2009; Norris & Ortega, 2009; Bulté & Housen, 2012; Boyle et al., 2013). However, this complexity across sentence types may be attributed to various sources, which may have features in common across the structures (e.g., Boyle et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2013; Snyder & Hyams, 2015; Friedmann et al., 2009). While the source of this complexity is beyond the scope of this study, the sentence conditions in (4) and (5) allow for two points of comparison:

| (4) | a. | Active voice: The cow washed the blue sheep. |

| b. | Passive voice: The cow was washed by the blue sheep. | |

| (5) | Experimenter: Something here is blue. | |

| [Child selects blue] | ||

| a. | Subject relative clause: There’s the sheep that washed the cow. | |

| b. | Object relative clause: There’s the sheep that the cow washed. | |

- Active/passive (in (4)) compared with subject/object relative clauses (in (5)), i.e., the sentence structure

- Simple structures ((4a) and (5a)) compared with complex structures ((4b) and (5b)), i.e., sentence complexity

The main test items consisted of 32 trials, with 8 items for each sentence structure (active voice, passive voice, subject relative clauses, object relative clauses). The test items were alternated with fillers comprising simple present-tense sentences with an animate subject and inanimate object, as in (6):

Participants were scored as either correct (1) or incorrect (0) for each of the trials, and each trial was entered into the dataset individually.

| (6) | a. Experimenter: Something here is blue. |

| [Child selects blue] | |

| b. It drives a bus. |

5.2.2. Narrative Task

To evaluate participants’ narrative language production, we used the Edmonton Narrative Norms Instrument (ENNI, Schneider et al., 2006)—a wordless picture narrative storytelling task. Preceding the main narrative task, participants completed a training story—a very short storytelling task—to facilitate their understanding for the narrative task. Participants were first instructed to only look at each picture one by one, and were given a few seconds to view each picture before moving on to the next one. Once the pictures were viewed, they were then presented to the children again, who were told that the examiner could not see the pictures and asked to tell the story. The children’s sentences were recorded and transcribed in the standard CHILDES format (MacWhinney, 2000) to collect assessment measures across language domains.

Vocabulary

Children’s vocabulary in the narrative speech samples was evaluated using two measures of lexical diversity, i.e., the degree of variation in the lexical items that children produced. The first of these, Type–Token Ratio (TTR), is based on a quantitative measure of the lexical types in the sample, i.e., unique vocabulary items, and tokens—the overall number of items, including repetitions. Types and tokens reflect different aspects of the sample: while type represents the variation in lexical items within the sample, token reflects the overall quantity of items. The Type–Token Ratio (TTR) therefore is the ratio of different types to the total number of tokens in a language sample, varying between 0 and 1, with greater lexical diversity reflected by values closer to 1. For example, a child who produces 100 tokens of the same type will have a lower TTR than a child who produces 100 tokens of different types.

This calculation of lexical diversity, however, can also be impacted by sample size. Specifically, a larger language sample with a larger number of tokens often results in lower values for the TTR, while samples containing smaller numbers of tokens often result in a higher TTR (Malvern et al., 2004; Richards, 1987). To address this concern with varied sample lengths, an additional measure—the VOCD lexical diversity measure—was also included in the analysis. VOCD—from “vocabulary diversity”—is based on an analysis of the probability of new vocabulary being introduced into longer samples of speech, yielding a mathematical model of how TTR varies with token size. Therefore, the key advantage of VOCD is that it is not a function of the number of words in the sample, as it represents how TTR varies over a range of token size (Malvern et al., 2004). For both TTR and VOCD, we used the kideval command in CLAN, which includes these calculations (MacWhinney, 2000). With one narrative speech sample per participant, we collected a single value for each participant for TTR, and a single value for VOCD. Note that this contrasts with the item-based assessments, which included a value for each trial of the assessment.

Morphology

While the item-based assessment allowed for elicited production of specific morphemes—the past tense and third person singular—these same morphemes were not consistently produced in the children’s narrative speech samples. To avoid floor effects for these specific morphemes, we therefore used the more comprehensive measure of mean length of utterance (MLU) as the narrative measure of children’s morphology. MLU was measured in the narrative speech samples as an average of the number of morphemes in each utterance, and was also calculated for each participant from the kideval command in CLAN (MacWhinney, 2000). As for each of the vocabulary measures, a single MLU value was produced for each participant.

Syntax

The final measure calculated from the narrative task was the production of complex sentence structures, as a measure of children’s syntax. This included subordinate clauses (relative, adverbial, and wh- clauses, and direct and indirect quotations) and non-finite clauses (infinitive, wh- infinitive, and gerund clauses). Complex sentence structures were analysed based on the ENNI complexity index, which views a complex sentence as one which contains an independent or main clause and one or more dependent clauses. Dependent clauses are subordinate or non-finite clauses with a verb.

To calculate the complexity index score for narrative production, the total number of clauses (independent and dependent) was divided by the number of independent clauses. For example, the complexity index score for a narrative with 13 independent clauses and 15 dependent clauses would be calculated as in Equation (1):

Examples of narrative utterances and complexity index scoring are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of complex and non-complex utterances from the narrative speech samples, with dependent clauses in bold.

As for vocabulary and morphology, the complexity index formula in Equation (1) produced a single measure for each participant. This resulted in a total of four individual measures for each participant from the narrative task, along with the accuracy values from each trial for the item-based tasks. To analyse these measures in the following sections, we ask whether the measures from the narrative tasks can predict children’s accuracy on the item-based tasks, for each language domain.

6. Results

In this section, we first describe the results of each task for monolinguals and bilinguals, followed by a correlation analysis across all tasks. This is followed by our regression analysis for each language domain. In summary, we find that the narrative measures generally do not predict measures on the item-based assessments, for any language domain—especially for bilinguals. Moreover, we find no correspondence by task type, i.e., children’s accuracy on item-based assessments is generally not predicted by other item-based assessments, with a similar result for the narratives. While some correspondences do emerge, the result is more nuanced, and we consider the implications across language domains in the discussion section.

6.1. Descriptive Statistics

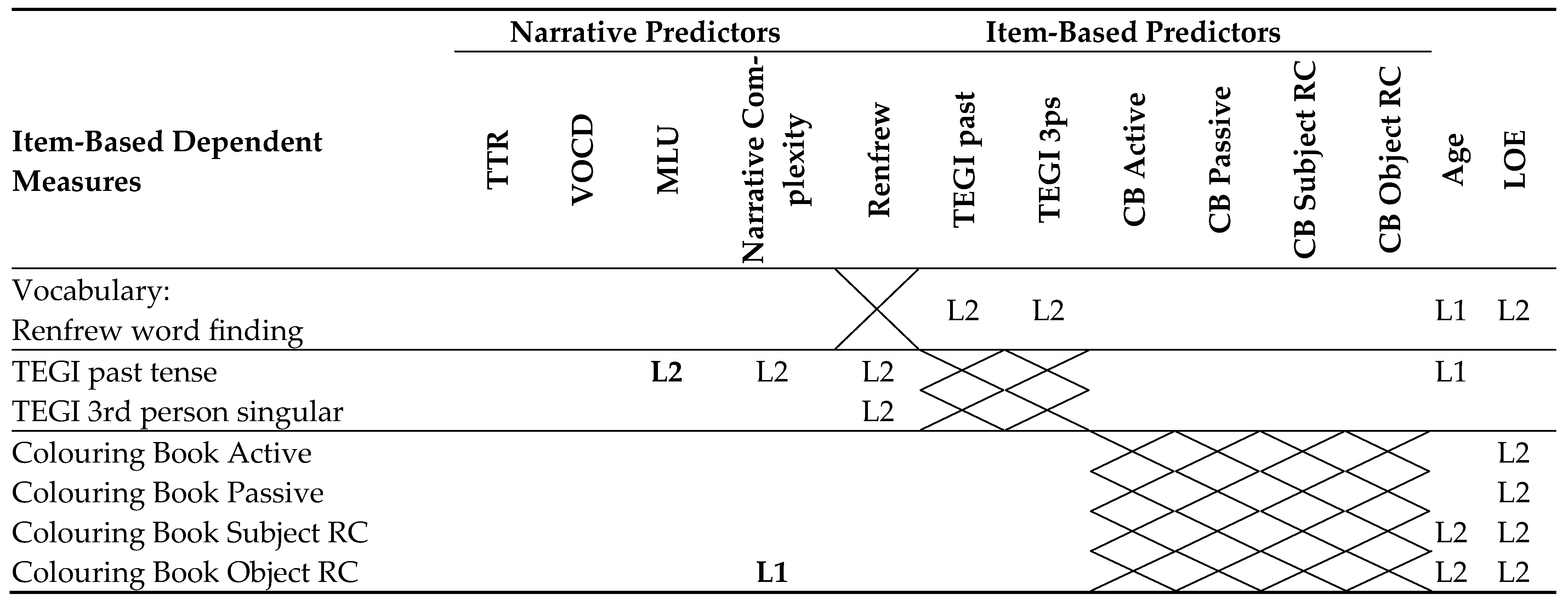

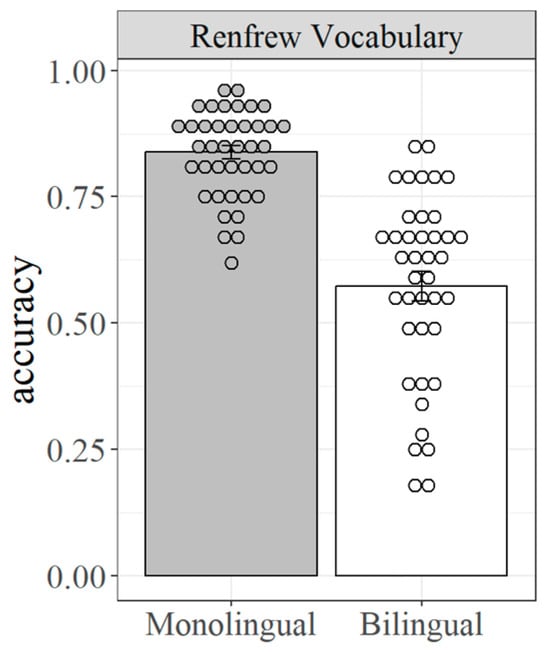

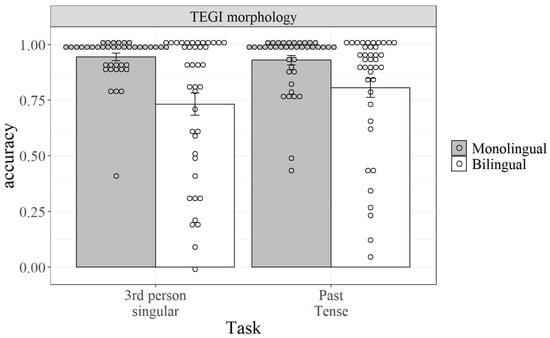

The results of each task for monolinguals and bilinguals are presented in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. Corresponding numerical values are provided in Appendix A.

Figure 2.

Accuracy for monolinguals and bilinguals on the Renfrew vocabulary task.

First, accuracy for monolinguals and bilinguals on the Renfrew vocabulary task is presented in Figure 2. As expected, accuracy is higher for monolinguals, with a broader distribution for bilinguals. Importantly, neither population is at floor or ceiling accuracy, which will allow for more meaningful comparisons with the other language measures.

Next, accuracy on the TEGI tasks is presented in Figure 3. This accuracy is generally higher for both populations than on the Renfrew vocabulary task, with largely ceiling accuracy for monolinguals. While this high accuracy is not unsurprising for monolinguals in the target age range (5;7–12;2), it should be taken into consideration for any correspondences in the regression analysis.

Figure 3.

Accuracy for monolinguals and bilinguals on the TEGI morphology task.

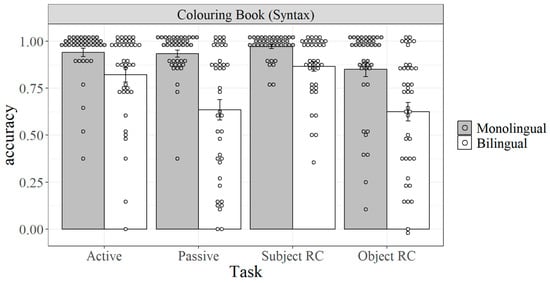

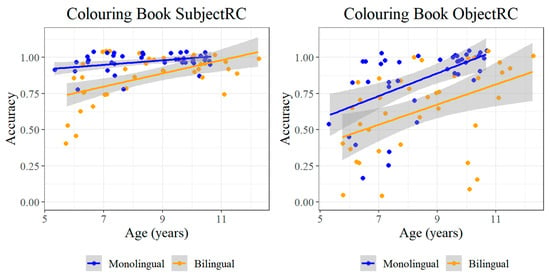

For the final item-based task, a broad range of variation is observed across populations on the Colouring Book Task as an assessment of children’s syntax (Figure 4). First, accuracy is generally at ceiling for monolinguals on all structures except for object relative clauses, meaning that the same caution as for the TEGI tasks should also be exercised for any correspondences for these structures in monolinguals.

Figure 4.

Accuracy on each syntactic structure for monolinguals and bilinguals in the Colouring Book Task.

In contrast, broader distributions are observed across all structures for bilinguals, along with lower accuracy. This contrast is especially apparent for the complex structures—passives and object relative clauses—despite the relatively lower accuracy on the latter for monolinguals.

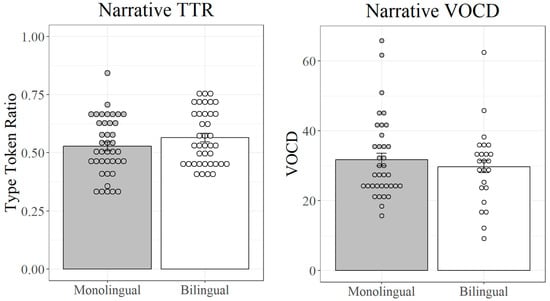

While clear contrasts emerged between monolinguals and bilinguals on the item-based tasks, the results for the narrative measures are more mixed. First, for both lexical diversity measures—TTR and VOCD—the same distribution is observed for both populations (Figure 5). While the results are broadly distributed for both measures, the similar distributions between monolinguals and bilinguals suggest that the variation involves processes which are not dependent on specific language experience—an unexpected result for vocabulary.

Figure 5.

Type–token ratio and VOCD for monolinguals and bilinguals in the narrative task.

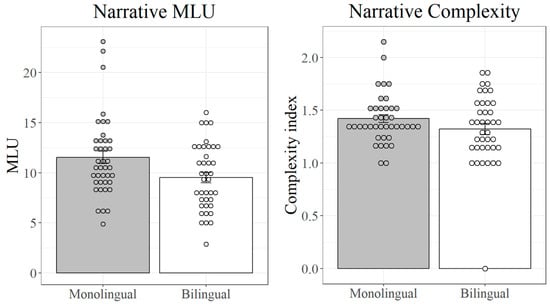

Finally, the narrative measure for morphology (MLU) and the measure for syntax (complexity based on embedded clauses) are both presented in Figure 6. Notably, the narrative complexity/syntax measure has the same distribution as for the measures of lexical diversity—i.e., with no difference between monolinguals and bilinguals. Rather, MLU stands out as the only narrative measure with a noticeable contrast between populations, although still with a broad enough range to allow for meaningful correspondences.

Figure 6.

MLU and complexity index for monolinguals and bilinguals in the narrative task.

6.2. Statistical Analysis

Before analysing children’s behaviour within each language domain, we conducted a correlation analysis to compare the different measures across tasks. These correlations are reported in Table 2 for monolinguals and Table 3 for bilinguals.

Table 2.

R correlation coefficients between age and language measures for monolinguals (cells with correspondences within domains are shaded).

Table 3.

R correlation coefficients between age and language measures for bilinguals (cells with correspondences within domains are shaded).

In addition to the task measures, we included children’s age as a continuous measure in the correlation analysis. As an indirect measure of overall language experience, including age as a factor may allow us to identify relations above and beyond this experience. Indeed, the correlation analysis in Table 2 and Table 3 revealed that many of the language measures were correlated with age both for monolinguals (Renfrew vocabulary; VOCD, TEGI past; and Colouring active, passive, subject relative clauses, and object relative clauses) and for bilinguals (TTR; TEGI past; and Colouring passive, subject relative clauses, and object relative clauses). However, several other correlations were observed both within and across domains, thus highlighting the need for a regression analysis to control for covarying factors.

We designed the regression analysis to determine the comparability between language measures, using logistic regression modelling with R (R Core Team, 2015) and lme4 (Bates et al., 2015). In particular, we aimed to establish whether the language measures from the item-based assessments (i.e., standardised and experimental tasks) were predicted by the narrative measure within the same language domain, over and above the measures in other domains. Thus, within-domain relations should be indicative of common processes in tasks within the same language domain, while cross-domain relations will identify common processes across tasks, independent of the domain. Finally, to address the correlations observed with age for both bilinguals and monolinguals, we included age as an additional factor in the analysis. The analysis is presented in the following sections, by language domain.

6.2.1. Logistic Regression Analyses for Vocabulary

With the logistic regression for vocabulary, we investigated whether children’s accuracy on the Renfrew Word Finding Vocabulary Task could be predicted by either of the narrative measures for lexical diversity. Each individual trial on the Renfrew task was entered into the model with a binary accuracy variable coded in the dataset as 1 (correct) or 0 (incorrect). The continuous narrative measures—Type–Token Ratio (TTR) and VOCD—were both calculated using CLAN and centred before being entered into the regression model.

In addition to the narrative measures, we included the following fixed effects:

- Monolingual/bilingual, to address our aim of investigating language measures across populations

- Age (in years, centred at 0), to assess the role of overall language experience as mentioned above

- The following measures from the other language domains (each centred at 0):

- ○

- Narrative MLU, as the narrative measure of morphological complexity

- ○

- Narrative embedded clauses, as the narrative measure of syntactic complexity

- ○

- Average accuracy on the TEGI (both past tense and 3rd person singular)

- ○

- Average accuracy on each of the four Colouring Book structures (active, passive, subject relative clause, and object relative clause)

We also included random effects of participant and item for the Renfrew vocabulary task to account for variation across individual participants and items, respectively. The results for this model are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Model for vocabulary (dependent measure = Renfrew vocabulary task accuracy).

The within-domain effects in Table 4 involve TTR and VOCD (in bold), which would indicate a correspondence between accuracy on the Renfrew vocabulary task and the narrative measures of lexical diversity. However, while the main effects of TTR and VOCD are both marginally significant—(β = −4.33, Z = −1.91, p = 0.061) and (β = 0.03, Z = 1.87, p = 0.061), respectively—both interactions with monolingual/bilingual are not significant. This suggests that the Renfrew task and narrative measures of lexical diversity measure different underlying processes, or that any shared processes play a relatively minor role in predicting children’s behaviour.

Meanwhile, other factors did predict children’s accuracy on the Renfrew task. Significant factors include age (β = −0.25, Z = −2.77, p = 0.006) and monolingual/bilingual (β = −2.58, Z = −7.16, p < 0.001), as well as an interaction between age and monolingual/bilingual (β = 0.58, Z = 3.20, p = 0.001); this suggests that the age effect is selective to one of the two populations. In addition, correspondences across domains are indicated by the interactions between the TEGI past tense and monolingual/bilingual (β = −3.97, Z = −2.14, p = 0.032) and between the Colouring Book active structure and monolingual/bilingual (β = −3.86, Z = −2.29, p = 0.022).

To explore these contrasts in main effects across populations, we conducted post hoc tests with the joint_tests function from the emmeans package in R (Lenth et al., 2022). The results of these tests are presented in Table 5, with significant effects in bold.

Table 5.

Vocabulary post hoc tests (dependent measure = Renfrew vocabulary task accuracy).

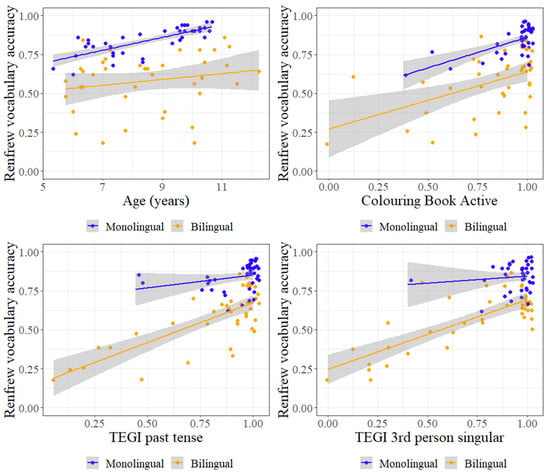

While the post hoc tests confirm the null effects for the narrative vocabulary measures, all three of the interactions in Table 4 are reflected in Table 5. Notably, the post hoc tests reveal different contrasts across populations. While Renfrew accuracy is predicted in monolinguals by age (F = 15.79, p < 0.001) and the Colouring Book active structure (F = 5.24, p = 0.022), accuracy in bilinguals is predicted by the TEGI past tense (F = 6.54, p = 0.011) and the TEGI 3rd person singular (F = 6.06, p = 0.014). These contrasting profiles are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Age, Colouring Book Active, TEGI past tense, and TEGI 3rd person singular by accuracy on the Renfrew vocabulary task for monolinguals and bilinguals.

All four of the graphs in Figure 7 clearly show the main effect of monolingual/bilingual, with a significantly higher accuracy observed for monolinguals. Meanwhile, the effects reported in Table 5 are also evident, most notably:

- Greater accuracy with age is observed for monolinguals, but not for bilinguals (top left plot).

- Greater accuracy is predicted by both TEGI tasks for bilinguals, but not monolinguals (bottom row plots).

These effects contrast with the correspondence for monolinguals in Table 5 between vocabulary and the Colouring Book Active structure. This relation was not expected, both conceptually and given that performance in monolinguals for the active structure was generally at ceiling (c.f. Figure 4). Figure 7 (top right plot) reveals that this relation for monolinguals is likely amplified by outliers.

In sum, there is a clear contrast between the profiles of monolinguals and bilinguals for the domain of vocabulary: for bilinguals, a correspondence was observed across item-based tasks—between the Renfrew vocabulary assessment and both TEGI tasks—while for monolinguals, the Renfrew accuracy was mainly predicted by age. This age effect for monolinguals but not bilinguals raises a key issue regarding the role of language experience/input: the factor of age reflects experience with English for monolinguals, but experience with multiple languages for bilinguals. Instead, experience with English is measured for bilinguals by a different factor—the length of exposure to English, measured as the difference between the current age and the age of initial English exposure. This measure is equal to age for monolinguals, meaning that age effects in monolinguals may be due to experience with English alone, or to experience with language in general. We revisit this distinction in Section 6.2.4, after exploring whether this same contrast is observed for other language domains.

6.2.2. Logistic Regression Analyses for Morphology

For morphology, the item-based tasks included the past-tense and 3rd-person-singular components of the TEGI. The narrative measure in this domain was MLU—a measure of morphological complexity which increases with a richer inflectional inventory. To compare these measures, we developed a logistic regression model with TEGI accuracy as a dependent measure, with each trial entered individually in the dataset as 1 (correct) or 0 (incorrect). To distinguish between the two tasks, we included a binary fixed effect of TEGI task (third person singular/past tense), while narrative MLU was included as the within-domain measure of morphological complexity, centred at 0.

As for vocabulary, we included the binary fixed-effect monolingual/bilingual to compare populations, and age as a continuous fixed effect centred at 0. We also included the following (centred) continuous measures:

- Narrative TTR and narrative VOCD, as narrative measures of lexical complexity

- Narrative embedded clauses, as the narrative measure of syntactic complexity

- Average accuracy on the Renfrew vocabulary task

- Average accuracy on each of the four Colouring Book structures (active, passive, subject relative clause, and object relative clause)

Finally, random effects of participant and item were included for the TEGI morphology task to account for variation across these factors. The full set of results for this model is reported in Appendix B, with the significant and marginal effects in Table 6.

Table 6.

Model for morphology (dependent measure = TEGI task accuracy); see also Appendix B.

While the main effect of MLU was not significant (β = 0.12, Z = 0.34, p = 0.732), there are two key interactions in Table 6 with narrative MLU (in bold). First, there is an interaction between MLU and monolingual/bilingual (β = −2.45, Z = −3.63, p < 0.001), suggesting that MLU predicted TEGI accuracy for just one of the populations. However, the three-way interaction between MLU, TEGI task, and monolingual/bilingual (β = 2.35, Z = 3.33, p = 0.001) suggests that this effect on TEGI accuracy is further limited to just one of the TEGI tasks.

Post hoc tests are needed to identify which task, and which population—not just for MLU but also for the other three-way interactions in Table 5, which suggest further relations than just the within-domain factor of MLU. We conducted these post hoc tests again with the joint_tests function from the R emmeans package (Lenth et al., 2022), by monolingual/bilingual and TEGI task; the results of these tests are presented in Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 7.

Morphology post hoc tests for monolinguals on the TEGI tasks.

Table 8.

Morphology post hoc tests for bilinguals on the TEGI tasks.

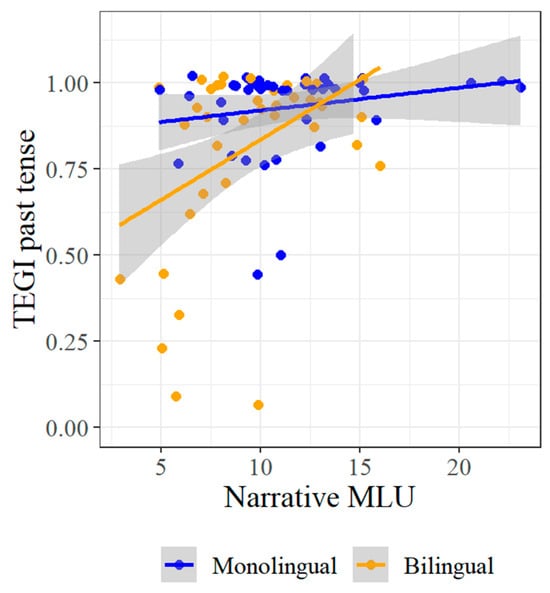

The first result to note in Table 7 and Table 8 is the significant effect of narrative MLU on TEGI past tense accuracy in both monolinguals (F = 5.23, p = 0.022) and bilinguals (F = 10.94, p = 0.001). While both effects are significant, we expected a difference between them based on the three-way interaction in Table 5 between MLU, TEGI task, and monolingual/bilingual. Indeed, Figure 8 reveals a stronger effect of MLU on TEGI past tense accuracy in bilinguals than in monolinguals—the latter of which was likely amplified by outliers with a higher MLU. Thus, a within-domain correspondence for morphology is clear for bilinguals, but less so for monolinguals. However, this correspondence must be interpreted in the context of the other significant effects in Table 7 and Table 8.

Figure 8.

TEGI past tense by Narrative MLU.

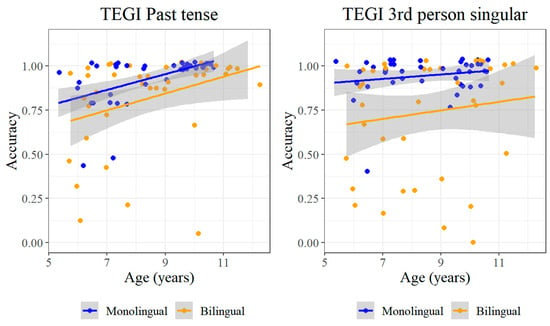

The first of these other effects bears a striking resemblance to the result for vocabulary—for monolinguals, age also predicts accuracy on the TEGI past tense (F = 12.31, p = 0.001). A marginal effect is also observed for bilinguals, however (F = 2.95, p = 0.086). This contrast is illustrated in Figure 9, which shows the same trend across both populations, but with more variation for bilinguals. Meanwhile, no age effect is observed in either population for the TEGI 3rd person singular.

Figure 9.

TEGI tasks by Age.

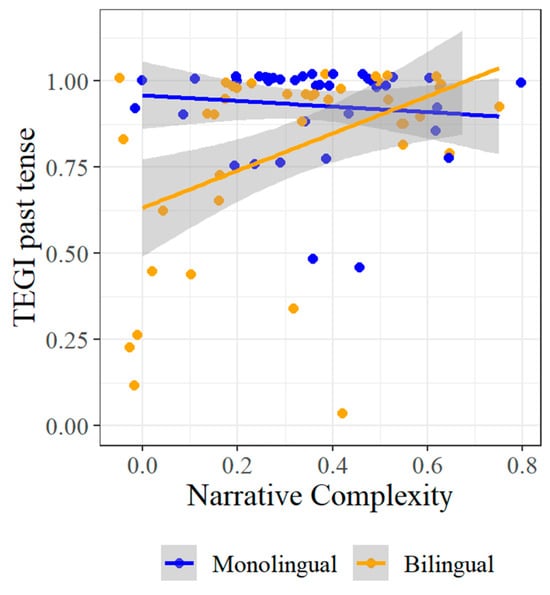

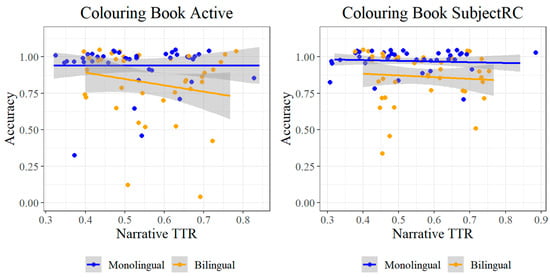

Next, while the prediction for a within-domain correspondence is borne out for morphology—particularly for bilinguals—effects are also observed for several cross-domain language measures. In particular, TEGI past tense accuracy was predicted by the narrative complexity measure in both monolinguals (F = 7.07, p = 0.008) and bilinguals (F = 7.32, p = 0.007), and by both narrative TTR (F = 7.94, p = 0.005) and narrative VOCD (F = 5.94, p = 0.015) in bilinguals.

The first of these—narrative complexity—patterns similarly to MLU (Figure 10). Moreover, like MLU, there is a clear effect for bilinguals, while the effect for monolinguals is more likely to be driven by outliers.

Figure 10.

TEGI past tense by Narrative Complexity.

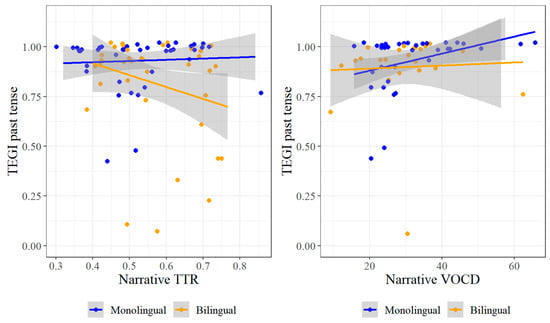

Next, while TEGI past tense accuracy is predicted in bilinguals by both narrative TTR and narrative VOCD, the interpretation of these effects is problematic, as illustrated by Figure 11. In particular, for both TTR and VOCD, higher values correspond with greater lexical diversity. However, the relation between TTR and the TEGI past tense for bilinguals in Figure 11 is negative: a higher TTR corresponds with lower TEGI accuracy. This relation is therefore more likely to reflect an issue with the assessment measure than a true relation, and we revisit this issue in the discussion. Meanwhile, no trend is apparent in Figure 11 between VOCD and the TEGI past tense for bilinguals, despite the significant effect.

Figure 11.

TEGI past tense by Narrative TTR and Narrative VOCD.

Finally, accuracy on both TEGI tasks is predicted by bilinguals’ accuracy on the Renfrew vocabulary task—past tense (F = 6.16, p = 0.013) and 3rd person singular (F = 8.55, p = 0.004). This relation is the same as the one observed for vocabulary above, where Renfrew accuracy for bilinguals was predicted by both TEGI tasks (Figure 7). Note, however, that while Renfrew accuracy was predicted only by the TEGI tasks, the TEGI past tense was also predicted by MLU and narrative complexity. Importantly, these effects provide further context to the correspondence above between morphology assessments; moreover, this context requires an analysis with measures across different language domains. The following section applies this analysis to the final language domain, syntax.

6.2.3. Logistic Regression Analyses for Syntax

For syntax, we used the Colouring Book Task described in Section 5.2.1 to assess children’s comprehension of the active voice, passive voice, subject relative clauses, and object relative clauses. Of these four structures, the passive voice and object relative clauses are expected to cause greater difficulty; this difficulty has been attributed to a range of sources (e.g., Adani, 2011; Friedmann et al., 2009; Gordon et al., 2001; Just & Carpenter, 1992; Van Dyke & Lewis, 2003; Lewis & Vasishth, 2005). Importantly, while we do not expect the exact same sources of difficulty for passives and object relative clauses, we do expect a lower accuracy in the Colouring Book Task for both of these structures than for actives and subject relative clauses.

To include all four structures in the same analysis with accuracy as the dependent measure, we constructed a similar regression model structure as for morphology above. However, to distinguish both between complexity (passives and object relative clauses compared to actives and subject relative clauses) and between structures (actives and passives compared to subject and object relative clauses), we expanded the single-factor “task” into these two separate binary fixed effects: Complex and Structure. As for vocabulary and morphology in the previous analyses, accuracy for each of these syntactic structures was entered for each trial as 1 (correct) or 0 (incorrect).

To compare assessments within the domain of syntax, we used the narrative measure of syntactic complexity based on the number of embedded clauses produced, as described in Section 5.2.2. The measure was calculated for each narrative and centred at 0.

Next, as for vocabulary and morphology, we included the binary fixed effect monolingual/bilingual to compare populations, and age as a continuous fixed effect centred at 0. We also included the following (centred) continuous measures:

- Narrative TTR and narrative VOCD, as narrative measures of lexical complexity

- Narrative MLU, as the narrative measure of morphological complexity

- Average accuracy on the Renfrew vocabulary task

- Average accuracy on the TEGI (both past tense and 3rd person singular)

Finally, random effects were included for participant and item in the Colouring Book Task, to account for variation across individual participants and items, respectively. The full set of results for this model is reported in Appendix B, with the significant and marginal effects in Table 9.

Table 9.

Model for syntax (dependent measure = Colouring Book Task accuracy); see also Appendix B.

Key effects to focus on in Table 9 for the within-domain (syntax) correspondence involve narrative complexity (in bold). For example, while the main effect of narrative complexity is not significant (β = 3.16, Z = 2.96, p = 0.286), there is a significant interaction between narrative complexity and monolingual/bilingual (β = −13.81, Z = −2.36, p = 0.018). This interaction suggests that this narrative complexity measure predicts accuracy on the Colouring Book Task for just one of the two populations; however, a further interaction arises between narrative complexity, Complex, and monolingual/bilingual (β = 12.00, Z = 1.99, p = 0.046). This second interaction indicates that the effect of narrative complexity is also selective to just complex or non-complex structures for this population, rather than all structures in the Colouring Book Task. Given that the narrative complexity measure is based on embedded clauses, we would predict this effect to result from a correspondence with complex rather than non-complex structures, although post hoc tests are required to confirm this prediction. The interactions with vocabulary and morphology measures in Table 9 also suggest that further correspondences are present across domains, which will be similarly clarified by the post hoc tests.

We conducted these post hoc tests again with the joint_tests function from the R emmeans package (Lenth et al., 2022), by monolingual/bilingual, Complex, and Structure, allowing us to isolate the effects across populations and the four Colouring Book structures (e.g., “Active” is Structure = Active/passive and Complex = non-complex); the results of these tests are presented in Table 10 and Table 11.

Table 10.

Syntax post hoc tests for monolinguals on the Colouring Book Task.

Table 11.

Syntax post hoc tests for bilinguals on the Colouring Book Task.

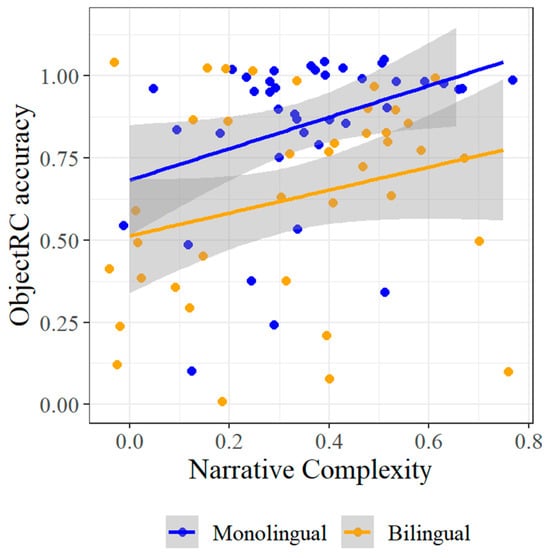

The first result to note in Table 10 and Table 11 is in relation to the effect of narrative complexity. Based on the three-way interaction in Table 9 between narrative complexity, Complex, and monolingual/bilingual, we expected this effect to be selective to just one population, for specific structures. Indeed, the effect of narrative complexity is observed only for monolinguals, in the object relative clause structure (F = 6.08, p = 0.014). This contrast between monolinguals and bilinguals is reflected in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Accuracy for object relative clauses by narrative complexity.

This effect of narrative complexity for monolinguals contrasts with the pattern observed for morphology, where narrative complexity predicted accuracy on the TEGI past tense for bilinguals. Moreover, the inverse result is also observed for age: while this measure predicted accuracy on the TEGI past tense for monolinguals, age does not predict monolinguals’ accuracy for any of the syntactic structures. Rather, accuracy in the syntactic domain is predicted by age for bilinguals—both for subject relative clauses (F = 5.38, p = 0.020) and object relative clauses (F = 4.15, p = 0.042). This contrast in age effects between monolinguals and bilinguals for subject and object relative clauses is illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Accuracy for subject and object relative clauses by Age.

For subject relative clauses, monolinguals’ ceiling performance can account for the lack of any age effect; this contrasts with bilinguals, who do show a subtle effect of age. Meanwhile, both populations appear to exhibit age effects for object relative clauses. The lack of a significant effect for monolinguals may therefore be due to collinearity with other predictors.

Table 10 and Table 11 contain four additional significant results. First, significant effects of narrative TTR are reported on monolinguals’ accuracy for both the active (F = 5.08, p = 0.024) and subject relative clause (F = 4.42, p = 0.036) structures. These effects are illustrated in Figure 14, and reflect the ceiling effect for both structures in monolinguals. They are therefore likely driven by outliers for both structures, rather than being meaningful effects.

Figure 14.

Accuracy for actives and subject relative clauses, by Narrative TTR.

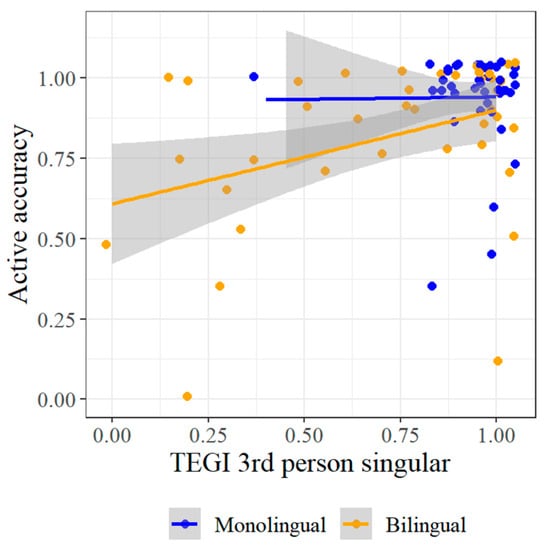

Finally, accuracy on the active structure is also predicted for monolinguals by the Renfrew vocabulary task and the TEGI 3rd person singular. The first of these was also observed with the Renfrew task as the dependent variable, in Figure 7 above, while the second is illustrated below in Figure 15. However, as for the relation with narrative TTR, the ceiling accuracy for monolinguals with the active structure suggests that these are not meaningful correspondences, and are likely driven by outliers.

Figure 15.

Accuracy for actives, by TEGI 3rd person singular.

In summary, for syntax, we observe a contrasting profile from the patterns for vocabulary and morphology: in particular, a within-domain correspondence is observed for monolinguals—between narrative complexity and object relative clauses—while accuracy for bilinguals is predicted only by age, for both subject and object relative clauses.

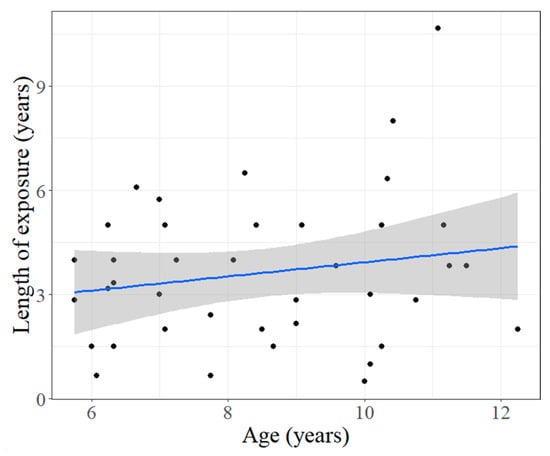

This age effect is unexpected for bilinguals, particularly in a context where no corresponding effect is observed for monolinguals. However, some additional context is missing from an effect of age. For monolinguals, age effects may reflect the role of different factors which develop in parallel. For example, while linguistic experience increases with age, so does the development of other domain-general cognitive processes which may interface with language. Meanwhile, age effects in bilinguals provide some opportunities to tease apart these factors: while age can reflect overall linguistic experience across multiple languages, experience with the second language—i.e., English in the current study—will depend on the length of exposure to the second language, rather than overall age. For monolinguals, these measures are one and the same. However, for bilinguals, these measures were not correlated (R = 0.18, p = 0.268), as illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Length of exposure to English for bilinguals, by age.

Thus, language measures which are more dependent on specific language experience should be predicted in bilinguals by the factor of length of exposure, while overall language experience will be more closely reflected by age. In the following section, we tease apart these effects by revisiting the analysis of each language domain for bilinguals, with the addition of length of exposure as a predicting factor.

6.2.4. Bilinguals Revisited: Length of Exposure

In the previous sections, we found that age did not predict accuracy in bilinguals for vocabulary and morphology, but an age effect was observed for subject and object relative clauses. However, this pattern must be interpretated in the context of the length of exposure (LOE). This context includes four possibilities:

- With no age effect (i.e., vocabulary and morphology), we may observe:

- an effect of LOE, suggesting that the assessment involves processes that depend on exposure to the specific language.

- no effect of LOE, suggesting that the assessment is not dependent on the input.

- With an age effect, we may observe:

- an effect of LOE, suggesting that the assessment involves processes that depend both on overall language experience (reflecting the effect of age) and on experience with the specific language (reflecting LOE).

- no effect of LOE, suggesting that the assessment depends entirely on overall language experience.

We tease apart these hypotheses in the following sections by comparing a model with LOE as a fixed effect to a model without LOE, for each language domain.

Vocabulary

For vocabulary, the models were identical to the one in Section 6.2.1, with two exceptions: first, as only the bilinguals were included in the analysis, monolingual/bilingual was not included as a fixed effect. Second, the LOE model included this factor as an additional fixed effect; this continuous measure was centred before being entered into the model.

There was a significant difference between the model with LOE and the model without LOE (χ2(1) = 12.166, p < 0.001), with a lower Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) for the model with LOE (865) than for the model without LOE (875). This suggests that children’s responses for the Renfrew vocabulary task were predicted by LOE, above and beyond the other measures. The results for this model are presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Model for vocabulary, with Length of Exposure (bilinguals only).

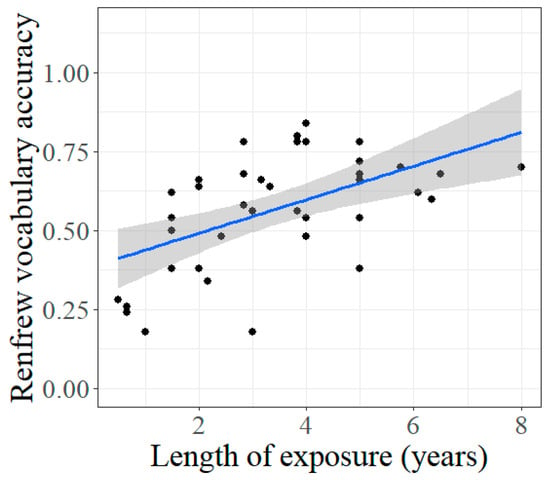

The key result in Table 12 is the strong effect of LOE (β = −0.43, Z = −3.88, p < 0.001), illustrated in Figure 17. With no additional effect of age, this suggests that the Renfrew task involves processes that are specific to English—an intuitive result for a vocabulary assessment. In contrast, the narrative measures for vocabulary—TTR and VOCD—remain non-significant, consistent with no within-domain correspondence for the vocabulary assessments. We return to the implications of this result in the discussion section.

Figure 17.

Renfrew vocabulary accuracy, by Length of exposure (LOE) for bilinguals.

Morphology

For morphology, the difference between the model with LOE and the model without LOE was not significant (χ2(2) = 3.70, p = 0.158), meaning that adding LOE as a fixed effect did not improve the model fit. Therefore, with no age effects observed in bilinguals in the original analysis for morphology, this suggests that accuracy on the TEGI morphology tasks for bilinguals is not related to language experience. Rather, as discussed in Section 6.2.2, these tasks were predicted for bilinguals by accuracy on the Renfrew vocabulary task, while the TEGI past tense was also predicted for bilinguals by the narrative measures for both morphology and syntax (i.e., the narrative measures of complexity). Note that Renfrew accuracy was predicted by LOE; we return to this contrast in the discussion section.

Syntax

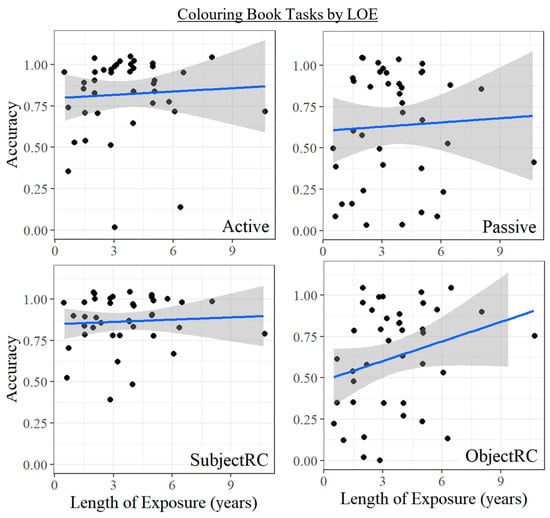

Finally, for syntax, there was a significant difference between the model with LOE and the model without LOE (χ2(4) = 26.19, p < 0.001), with a lower AIC for the model with LOE (637) than for the model without LOE (655). This suggests that children’s responses for the Colouring Book Task were predicted by LOE, above and beyond the other measures. As this model included the four different syntactic structures differentiated by the fixed effects Structure and Complex, we conducted post hoc tests by these factors using the joint_tests function in R (Lenth et al., 2022) to identify the relevant effects for each structure, as shown in Table 13. Notably, the effect of Length of Exposure in Table 13 is significant across all four syntactic structures. This result is illustrated in Figure 18.

Table 13.

Post hoc tests for bilinguals on the Colouring Book Task, with Length of Exposure.

Figure 18.

Accuracy for bilinguals on the Colouring Book Task, by Length of Exposure.

While the LOE effects appear to vary in Figure 18, the interactions were not significant between LOE and Structure (β = −0.49, Z = −1.29, p = 0.196), LOE and Complex (β = 0.14, Z = −0.38, p = 0.703), or LOE, Structure, and Complex (β = −0.04, Z = 0.10, p = 0.919). Meanwhile, in addition to LOE, subject and object relative clauses were also predicted by age. This combination of age and LOE effects for subject and object relative clauses is consistent with the hypothesis above that accuracy for these structures in the Colouring Book Task depends both on overall language experience (reflecting the effect of age) and on experience with the specific language (reflecting LOE). This contrasts with the Renfrew vocabulary task, which was predicted by LOE but not by age.

The results discussed in the previous sections are summarised in Table 14, with the two within-domain correspondences in bold. We consider the implications of these results in the final discussion section.

Table 14.

Summary for monolinguals (L1) and bilinguals (L2); within-domain effects in bold1.

7. Discussion

The aim of this research was to examine whether different measures of language proficiency generate comparable results, and also whether these results vary depending on the language domain (vocabulary, morphology, and syntax) and language population (sequential bilingual and monolingual). To answer this question, 40 sequential bilingual children and 40 monolingual primary-school-aged children completed three item-based language assessments—one for each language domain—and a narrative task which produced narrative language measures for each domain.

To compare different language measures across tasks and populations, we used the language assessment measures to predict children’s accuracy on the item-based assessments for each language domain. We found that the measures did not correspond within a given domain, with two exceptions:

- MLU predicted accuracy on the TEGI past tense for bilinguals. However, accuracy on this same assessment was also predicted by the syntactic measure of narrative complexity, as well as the average accuracy on the Renfrew vocabulary task.

- Narrative complexity predicted accuracy with object relative clauses for monolinguals. However, this effect was not also observed for bilinguals.

Children’s accuracy also was predicted by age, and—for bilinguals—by length of exposure to English, depending on the domain, above and beyond the effects observed for specific language assessment. In the following sections, we review these effects for each language domain and consider their implications for language assessment.

7.1. Vocabulary: Effects of English Language Experience

We assessed vocabulary with the Word Finding Vocabulary Test from the Renfrew Language Scales (Renfrew, 1995), and with two lexical diversity measures calculated from the participants’ narrative productions—TTR and VOCD. A key consideration for these vocabulary measures is the role of language experience. For monolinguals, this experience can be generally reflected by their age, which in turn predicted their accuracy on the Renfrew task. In contrast, age for bilinguals is more likely to represent language experience in both the L1 and the L2 than in just English (the L2). This contrast between age for monolinguals and age for bilinguals is supported by the significant effect of Length of Exposure (LOE) for bilinguals on Renfrew accuracy. As the populations were age-matched, the monolinguals had more exposure to English, which in turn predicts the difference in overall accuracy on the Renfrew task between monolinguals and bilinguals (Figure 2).