Abstract

Reusable launch vehicles are a key category of next-gen European launchers, as multiple companies are in advanced stages of study and are shifting towards the development of first demonstrators. A worldwide tendency to reduce the costs associated with satellite insertion into low Earth orbits can be observed, together with the existence of a niche in the future European launcher family for reusable small launch vehicles, known as microlaunchers. Multiple recovery methods exist for space launch vehicles; in this study, a return to launch site (RTLS) vertical-landing approach is being prioritized for the recovery of the first stage of a two-stage LOX/methane microlauncher. In 2023, INCAS, with support from the Romanian Nucleu Program, initiated a large study to address the prospect of developing a partially reusable microlauncher. A multidisciplinary optimization (MDO) environment has been developed, which is used in this paper to assess the implications of stage recovery versus the landing location (return to launch site versus downrange recovery) and state whether an RTLS can be feasible for small launchers. The paper will also present some key results from previous studies, such that a clear solution trade-off can be made, together with the quantitative assessment of how different vertical-landing techniques affect the microlauncher specifications.

1. Introduction

The space launch vehicle sector is one that is receiving growing attention in the European region, as investments continue to rise in the development of new launch capabilities. Modern launchers are engineered such that the associated costs of satellite insertion into low Earth orbit are as low as possible. This has led to the possibility of reusing major components of the same launch vehicle for multiple flights [1,2,3,4], with one of the best solutions being to recover the first stage. The way in which the launcher’s first stage is recovered must ensure that minimal damage occurs, such that the refurbishment process is cost- and time-effective. The recovery mission thus must provide a way to dissipate the energy (mainly kinetic, but also potential) associated with the conditions at stage separation.

Several approaches for the recovery mission exist, some of them in conceptual phases, while others have already been flight-proven [5]. Autonomous vertical-landing is seen as the baseline approach to the recovery of a first stage (or booster if the launch vehicle architecture contains it) and has already been successfully performed numerous times by the Falcon 9 launcher of SpaceX [6] and once by the New Glenn launcher of Blue Origin [7]. An interesting approach for stage recovery is that of horizontal landing techniques [8], but one of the major drawbacks is the need for a winged fuselage architecture for the first stage, which will significantly increase the mass and cost of the first stage [9].

It is clear that a knowledge gap associated with launcher reusability exists in the European zone, as no flight-proven reusable launchers exist. This extends to launch vehicles of all sizes; however, there are ongoing projects that address the reusability subject in the context of medium/large launch vehicles. The most important vehicles that are in advanced phases of development are MIURA 5 [10], CALLISTO [11], THEMIS [12], and SALTO [13]. At the small launch vehicles level (known also as microlaunchers), there are some ongoing projects related to RFA One, Orbex Prime, Maia, and Skykora XL [14].

In Romania, INCAS has received funding through the National Nucleu Program to develop a multidisciplinary optimization (MDO) environment that addresses the preliminary generation of reusable microlaunchers that could be used as starting blocks towards the development of a locally operated launch vehicle. If we consider the case of a vertical-landing recovery mission for the potential reusable microlauncher, one of two possible scenarios can be envisioned. The first one is that of a recovery from a secondary location (which is at a fairly high distance away from the launch site), and the second one is the recovery from the same location as the launch pad (or in very close vicinity).

For the first case, the recovery mission profile has a lower technical complexity associated, as the maneuvers needed for first-stage recovery are fairly simple (mostly ballistic trajectory, flip-over maneuver at apogee with the aid of the reaction control system, reentry and landing burns with the aid of the rocket engine and a possible aerodynamic guidance at low altitudes with the aid of a grid fin system). This type of recovery mission has been used as the basis for a previous study [15], where a partially reusable microlauncher concept has been developed that successfully inserts a 100 kg payload into a 400 km altitude, circular, polar low Earth orbit. The results from [15] will be used later in this paper (Section 5) to quantify the influence of the recovery location on the launcher.

The primary objective of the current study is to address the feasibility of using a RTLS first-stage recovery mission for a two-stage microlauncher. Feasibility analysis involves evaluating whether a proposed concept can be realistically implemented and justified in terms of performance and economic constraints.

The nominal main mission studied in this paper will be identical to that of paper [15] such that a clear constructive solution comparison and trade-off can be made, which will aid towards the formulation of a feasibility conclusion. To better understand the impact of the recovery mission, results obtained with the same multidisciplinary optimization tool (developed in INCAS for the Nucleu project) for the generation of a classical and expendable microlauncher concept will also be used [16].

The optimization case setup implemented in this paper will be as close as possible to that used in previous papers [15,16]. A two-stage constant-diameter architecture is implemented as it is seen as the most cost-effective and reduced complexity technical solution that can be used. If enough improvements are made in the materials and propulsion departments, one can imagine a single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) launch vehicle concept in the future, but at this time, only suborbital single-stage vehicles exist (ex. New Shepard [17]).

Regarding the propulsion aspect, the partially reusable microlauncher will consist of two stages with one rocket engine per stage, the liquid–propellant pair of choice being LOX/methane as it provides high thrust generation (higher specific impulse compared to LOX/kerosene [18]) with lower technical complexity (compared to LOX/hydrogen [19]).

The current study will provide scientific insight on the applicability of RTLS for the first stage of small reusable launch vehicle by realizing a quantitative assessment with the aid of an in-house MDO environment which will showcase the impact of this recovery method on key microlauncher design, mass and economic indicators.

2. The Multidisciplinary Optimization Framework

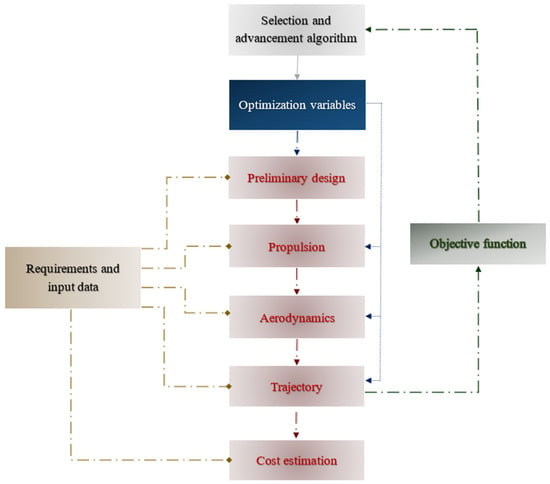

To generate a viable constructive design solution for a partially reusable small launch vehicle, we will use a multidisciplinary optimization algorithm written in Matlab version R2024a [20], with the algorithm previously presented in detail in paper [15]. The block diagram of the MDO algorithm is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

MDO algorithm block algorithm.

Besides the definition of the microlauncher concept (that minimizes an imposed objective function), all of its performances are evaluated during the disciplinary analyses realized across the MDO algorithm’s main five modules: Preliminary design, Propulsion, Aerodynamics, Trajectory, and Cost estimation. Of these five modules, only four are directly called during an iterative optimization process (first four), while the Cost estimation module is invoked only once the solution has converged (when the objective function no longer improves after a set number of iterations) to reduce the computational time. The detailed mathematical models employed within the five disciplines depicted in Figure 1 are presented in [15] and will be briefly mentioned here, with a focus on the differences that appear.

Each of the five main modules has been independently validated using publicly available data of launch vehicles (both expendable and reusable), rocket engines ranging from 30 kN to 8 MN, CFD investigations of typical launchers, orbital performance charts of small launchers (Falcons 1 and 1e), and cost databases. More details are given in [15,21].

As part of the Preliminary design module, the microlauncher configuration is dimensioned based on a bottom-up strategy where the critical components and assemblies are individually computed. By adding up all the individual contributions, the lower and upper structures can be obtained. The lower structure consists of two stages, with the first one being reusable, while the second one is expendable. The upper structure contains the payload (satellite), adapter, the VEB zone (vehicle equipment bay), and the fairing [22,23], which is jettisoned once the dynamic pressure decreases beneath a predefined threshold. The breakdown schemes of the two stages are drastically different; as for the recovery of the first stage, the following critical systems must be implemented: aerodynamic control system (ACS), extra-atmospheric flight control system (RCS using cold gas thrusters), enlarged interstage (to include the ACS and RCS), a foldable landing system, and a heat shield (to ensure that the atmospheric reentry does not structurally affect the integrity of the stage).

Within the second main module (Propulsion module), the performance of the liquid-propellant rocket engines is estimated. The throttle setting of the engine was set at a constant 100% rate to limit the number of optimization variables; thus, the propellant mass flow rate is constant. The main propulsive parameter needed to be evaluated during this assessment is the specific impulse, which is realized with the aid of in-house propulsive approximation functions derived from a thermochemical equilibrium study [15].

Within the Aerodynamics module, separate aerodynamic databases are generated for all microlauncher configurations that may appear during the main microlauncher mission (insertion of predefined payload into orbit), as well as for all the unique first-stage configurations that may appear during the recovery mission (eight different configurations [15]). Because the MDO tool implements a dynamic model with 3 degrees of freedom (3DOF) in the Trajectory module, only four aerodynamic force coefficients are assessed: the axial force coefficient (), the normal force coefficient (), the drag coefficient (), and the lift coefficient (). We have integrated an approach where the aerodatabase generation is split into a “clean configuration” contribution, and two external component contributions (aerodynamic control system and landing system) such that validated linearized models can be used for the axisymmetric launcher case [15], and CFD results are used for the 4 grid fin-based ACS and the four foldable-leg landing system [24,25].

Within the Trajectory module, two separate missions are simulated, with the recovery one being addressed only if the main mission’s reference trajectory ensures that stage separation is realized in adequate conditions. Inside the fourth module of the MDO, a 3DOF dynamic model is integrated, where only the translational motion is being simulated, as the launcher (or first stage in the case of the recovery mission) is considered a variable mass point. A model assuming a null bank angle

is used, and the six corresponding equations of motion are formulated in the quasi-velocity frame of reference. The aerodynamic angles

and

are treated as control parameters of the system, enabling the trajectory flight path angle

and the track angle

to be controlled via feedback loops schemes [15].

Within the Estimated cost module, system-level cost estimation relations are used to evaluate the development, production, and operations costs based on a mathematical model derived from TransCost [26] with additional corrections [27,28]. To better understand the economic implications of a microlauncher concept, the total cost per launch () is computed, together with a proposed final price per launch that a possible client could be charged with. As mentioned before, this main module is not called during the iterative process of solution optimization, but rather after solution convergence, as no output data from this module is needed inside the Objective function definition.

As seen in the block scheme presented in Figure 1, in addition to the five main modules that are used to discipline the performance of the launcher concept, four additional modules are needed so that the optimization process occurs.

Within the first additional module (Requirements and input data), various data are defined such as orbit requirements, constraints to be applied to the trajectory definition, design architecture (number of stages, fairing type, maximum stage fineness, etc.), imposed solution search space (lower and upper bounds of the optimization variable vector), launch site coordinates, maximum downrange of recovery location, fairing separation conditions, materials used for different components, and so on.

One important aspect related to the optimization process is the selection of Optimization variables. With the aid of the optimization variables (which are stored inside an optimization variable vector), the entire microlauncher concept and performance can be defined. The optimal partially reusable microlauncher concept is generated with the MDO tool developed by obtaining the best possible optimization variable vector. At MDO convergence, the solution proposed is seen as “optimal,” but in reality, this cannot be proven mathematically as no search algorithm is capable of providing a true optimum for large-dimensional complex problems such as the one of launch vehicle optimization [29,30].

The optimization vector can be seen as a collection of four different subsets, each being responsible for a separate optimization process (first-stage definition, second-stage definition, main mission definition, and recovery mission definition). The entire optimization variable vector structure is shown in Table 1, where a total of 23 distinct variables is needed to generate a partially reusable microlauncher solution that includes an RTLS vertical-landing recovery. Of these 23 variables, 10 are needed to define the microlauncher concept (weights and sizing, propulsive, aero characteristics, and cost estimates), 6 are needed for the reference trajectory definition of the main mission (payload insertion into orbit), and 7 are used to define the reference trajectory for the recovery mission. Compared to the downrange recovery (at a different location from the launch site) of the first stage studied in [15], it can be seen that another three optimization variables are needed (it was previously 20). This is because of an additional maneuver needed for the RTLS recovery mission profile, in the form of the boostback burn (details in Section 3.2). To reduce the optimal solution search space and improve numerical performance, a dimensionless formulation of the optimization variables was implemented wherever it was convenient (it can be seen from Table 1 that the rocket engines’ burn times are not subject to optimization; rather, the ratio between the thrust and weight (instantaneous) at the start of each engine).

Table 1.

Optimization variables used.

A critical aspect of the optimization process (which evolves over time) is the objective function employed, which is seen as the criterion by which the solution (numerical entries of the vector that incorporates the optimization variables) is selected and advanced. To correctly compare the first-stage RTLS and the downrange recovery missions’ impact on the microlauncher solution, the same objective function proposed in [15] is also being implemented in this study. The following formulation is thus implemented inside the MDO, where the most important selection parameter is the microlauncher mass at lift-off (between launchers that successfully accomplish both main and recovery missions):

with

being the microlauncher mass at lift-off,

being the main mission performance index,

being the recovery mission performance index, and

being the constraint index.

During the iterative optimization process,

decreases towards its minimum value, which correlates to a minimum value of

, while the terms

and

tend to null values (meaning a perfect payload orbit insertion and a perfect stage recovery). If there are no violated constraints, then

decreases to the value 1.

The main mission performance index is evaluated using [15]:

with

being parameters weights [30],

being the semimajor axis,

being the velocity (inertial),

being the flight path angle (FPA), and

being the inclination of the orbit.

In Equation (2), indices

denote target values (which are computed with respect to the predefined target orbit), while non-indexed parameters correspond to actual values obtained in the Trajectory module after the integration of equations of motion. More details can be obtained from [30] with respect to the methodology of obtaining the six classical orbital parameters from the position and velocity vectors of the 3DOF dynamic model. The weights associated with the parameters of Equation (2) are identical to the ones used in previous studies, as it was observed that using a higher order of magnitude weight for the flight path angle and orbit inclination (10 vs. 1) results in a faster convergence process.

The performance index for the recovery mission is assessed using [15]:

Here,

(measured in tons) denotes the propellant mass which remains unused at the time of first stage touchdown. It has a negative impact on the performance of the microlauncher concept due to the high amount of energy that has been used to transport this propellant from the ground up towards the first-stage separation location and then brought back to Earth. The second term

(measured in hm) quantifies the position error between the actual landing location and the prescribed landing location, which, in the case of an RTLS vertical recovery mission, is almost identical to the launch pad (it is considered identical in this study, but in reality, is in the close vicinity). This term is computed using the haversine distance [31]:

Here, index

corresponds to the desired landing location, and index 2 corresponds to the actual obtained landing location,

is Earth’s radius,

is the geocentric latitude and

is the geocentric longitude (relative).

The constraint index serves to assess the compliance of the microlauncher architecture or reference trajectories with imposed requirements and has the following form:

where

represent the total number of imposed constraints and

represents the individual performance index corresponding to the

th constraint. A comprehensive list of possible constrains are given in [15].

Whenever the

th constraint is satisfactory, the term

takes a value of 1 and does not negatively impact the objective function detailed in Equation (1). If for a particular set of optimization variables, the imposed constraint

is violated then

will have a numerical value greater than one and will negatively impact the objective function. The term

is computed using

where

is the imposed value of constraint

(details in Section 4.1),

is the obtained value of the constraint parameter (after all MDO main modules assessments), and

is a penalty factor (

for the main mission constraints and

for the constraints associated with the recovery mission [15]).

The Selection and advancement algorithm plays a crucial role, as it generates the numerical values inside the optimization variable vector required for performing the multidisciplinary analysis across the MDO algorithm’s’ five main modules. The literature reports numerous selection and advancement methods for optimization problems [29]; however, not all are applicable to space launch vehicle design.

Due to the complexity of the mathematical models within the MDO modules, the number of optimization variables can be substantial. Therefore, advancement methods capable of efficiently handling a high-dimensional variable space are necessary, with heuristic approaches being the most suitable. Thus, for the Selection and advancement algorithm, a classical genetic algorithm was implemented, being the most robust heuristic search algorithm [32,33] and widely used in the aerospace field [34,35], which yielded very good results in previous papers regarding launch vehicle optimizations [15,21,30].

3. Mission Profiles

The trajectory optimization process of the MDO algorithm is strictly dependent on the mission profiles implemented within the MDO algorithm’s Trajectory module (block scheme of the developed tool is shown in Figure 1) for both main and recovery missions, as different flight phases occur that use different formulations of the external force components (propulsive and aerodynamic). A short overview of the mission profiles will now be given. More details can be found in paper [15].

3.1. Main Mission

The primary mission of the reusable microlauncher is to deliver the payload (satellite) to a specified target orbit. The characteristics of the mission profile depend on the payload mass and the specified target orbit altitude. Because the primary categories of satellites that are inserted with the aid of microlaunchers are those of mini and microsatellites (10–100 kg) [36], they are usually reserved for Earth observation missions. The corresponding target orbits of interest are of low-altitude (ranging from 200 to 800 km, predominantly near the 400 km region) and high-inclination (polar or Sun-synchronous). Thus, the ascent trajectory of the microlauncher is often a direct ascent to orbit type (DATO). By using a DATO mission profile, the complexity of the rocket engines is lower (compared to a two-burn trajectory), as no successive restarts are needed for the upper stage (second stage in our case). Another advantage with respect to using a DATO trajectory is that of lower mission time, with the payload being anticipated to reach the target low Earth orbit in under 10 min from lift-off (in paper [30], the influence of LEO target altitude on the DATO mission time elapsed from lift-off has been analyzed, with the results showing a total mission time of approximately 6 min for a 200 km altitude, polar, circular, and orbit and around 10 min for a 600 km orbit of same specifications).

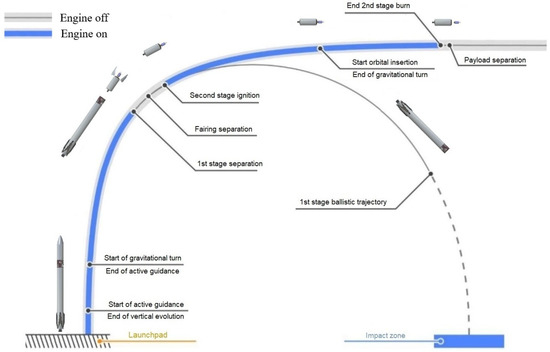

To better understand the maneuvers needed during the main mission of the microlauncher, the mission profile implemented inside the MDO tool is depicted in Figure 2, being identical to the one presented in paper [15]. For a simpler graphical representation, the recovery mission is not represented here, as it would obstruct some key flight phases and events. The recovery mission will be further defined in Section 3.2 as it is dependent on the location of stage recovery.

Figure 2.

Microlauncher main mission profile (DATO trajectory) [15].

When analyzing the mission profile presented in Figure 2, one can observe the existence of multiple key events and flight phases that must be incorporated into the MDO algorithm Trajectory module. A full list is given in Table 2, together with the corresponding microlauncher configuration major assemblies list and the situation of the engine (on = generates thrust; off = does not generate thrust).

Table 2.

Main mission profile, flight phase, and key events.

A complete definition of the main microlauncher mission can be achieved using just six optimization variables, as mentioned in Table 1. Two of them (

and

) directly dictate the duration of two flight phases mentioned in Table 2 (flight phase one and the time between phases four and six).

Two of them (

and

) quantify the time for which active guidance is implemented per stage (in reality achieved through the form of non-zero TVC deflection, but implemented inside the MDO tool as non-zero aerodynamic angles because of the 3DOF environment, where the launcher is a point of variable mass). During the active guidance phases, the thrust vector direction relative to the velocity vector is adjusted according to predefined feedback schemes [15,30].

During primary phases with active guidance, the following are implemented:

where

is a setting parameter,

is the angle of attack,

is the sideslip angle,

is the flight path angle, and

is the track angle.

For the orbital insertion maneuver, the aerodynamic angles (viewed as system control parameters) are computed using [15,30]

where

is the target orbit inclination,

and

are tuning parameters [15], and

is the orbit-related system command, obtained by enforcing the maximum reduction in orbital eccentricity within a minimal time frame. More details on the mathematical formulations needed to obtain

are given in [15,30].

The other two remaining variables of the main mission definition subset (

and

) are needed in relations (7).

3.2. Return to Launch Site Recovery Mission

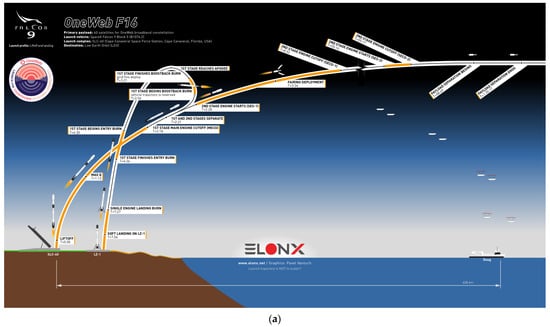

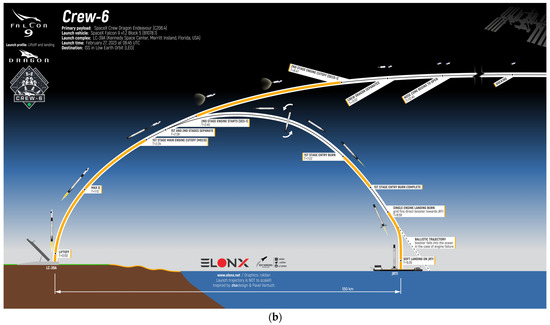

As depicted in Figure 2, the primary microlauncher mission does not take into account the first-stage propagation after separation. For a classical microlauncher case, where both stages are expendable, the first stage follows a ballistic trajectory towards the impact zone. In the context of a partially reusable microlauncher (where the first-stage assembly is recoverable while the second stage is expendable), the evolution of the first stage after separation is of great interest. In this paper, a focus on a return to launch site vertical-landing recovery mission and its implications is desired. The other main recovery method for the first stage is a downrange vertical-landing, where the landing location is at a significant distance from the launch site, which was previously studied in [15].

Nevertheless, a first-order grasp of the complexity of an RTLS recovery mission can be obtained when graphically presenting both types of recovery missions side by side, as in Figure 3 [37]. Here, the reference trajectories of the SpaceX Falcon 9 launch vehicle are depicted for the OneWeb F16 mission and for the Crew-6 mission.

Figure 3.

Recovery mission profiles [37]: (a) return to launch site; (b) downrange landing.

A similar recovery mission profile as the one depicted in Figure 3a is implemented inside the MDO tool developed. The full list of flight phases and key events of the recovery mission profile is presented in Table 3, together with the state of the additional system used to recover the first-stage configuration (Reaction Control System—RCS, Aerodynamic Control System—ACS, and Landing system).

Table 3.

RTLS mission profile, flight phase, and key events.

A total of 12 flight phases and key events are needed to successfully simulate an RTLS recovery mission, which is slightly higher compared to the downrange recovery mission studied in [15] (nine phases). The additional three phases are a direct consequence of the need to change the attitude of the first stage and burn additional propellant to return the stage towards the lift-off location (boostback burn). Nevertheless, the entire recovery mission is simulated using just seven optimization variables (last subset of Table 1).

The onset of the recovery mission is defined with reference to the separation of the first stage, which is found in Table 2 (event number 4). The first stage is separated when all the propellant allocated for the main mission is burned (the first-stage tanks still contain

, which is the recovery mission propellant mass). The start conditions of the first-stage assembly are obtained from the Trajectory module, and from this point onwards, the recovery mission is seen as an independent problem subject to optimization, where the propellant mass is indirectly minimized (while still respecting major imposed constraints such as maximum velocity or maximum deviation from vertical at touchdown).

Following stage separation, the stage experiences an initial ballistic trajectory up until the moment in which the stage is rotated such that the orientation of the first stage is towards the landing location (same as the lift-off location). The duration of the first ballistic phase is identical to the optimization variable

. During this phase, the flight path angle

naturally decreases due to the gravitational acceleration, while both aerodynamic angles

remain 0. The rotation maneuver is realized instantaneously with the aid of the RCS, where some quantity of pressurized nitrogen gas is expelled (the exact mass is computed based on the required impulse needed to rotate the stage [15]).

The boostback burn is performed until the flight path and track angles of the first stage increase to the desired target parameters

and

(both optimization variables). During this maneuver, the angle of attack

, which ensures that all of the thrust generated by the rocket engine is used to counter the horizontal velocity of the first stage, and if

, then the stage will continue its journey towards the launch site. Due to the natural angular velocity of Earth, lateral control must also be imposed (

), especially when launching towards the North Pole (for a polar orbit), as the exact location of the lift-off pad has slightly shifted and cannot be reached with only pitch channel control commands. This is realized with the aid of a relation similar to (7).

A secondary ballistic evolution then follows (with null

), and at the apogee, the RCS performs a flip-over maneuver. Additionally, at ballistic trajectory apogee, the ACS is deployed and can be used to modify the first-stage attitude (the altitude is still high, and the aero performance is very poor; thus, the grid fins are mainly not deflected).

Next, the third ballistic evolution occurs, but now

and

, as the orientation of the stage is nozzle front facing (as opposed to interstage front facing for the phases up to this point). At some point, when the altitude of the first stage drops below the threshold

, the reentry burn is initiated to both slow down the stage and to reduce the aerothermal loads acting on the surface of the stage. A heat shield is implemented during the MDO Preliminary design module (mathematical modeling is detailed in [15]), thus the heating part of the atmospheric reentry is considered to be of little interest at this point. The reentry burn ends once the propellant reserved for this maneuver is completely used, as determined by the optimization variable

.

After the reentry burn, an aerodynamic guidance phase occurs, comparable to a ballistic phase, during which the rocket engine is still tuned off, while the ACS is capable of deflecting the grid fins to slightly alter the attitude of the first stage if perturbations occur. During the 3DOF trajectory simulation, the grid fins were considered to be not deflected (but deployed, deflection = 0°); thus, only drag is being generated as no reference trajectory is yet defined that could need any lateral aerodynamic forces. It could be seen as a reserve of control authority, which could only be realistically evaluated in a 6DOF environment.

The landing burn starts at the moment the first stage drops below the threshold attitude

(optimization variable) and ends if either the altitude reaches 0, the vertical velocity of the configuration reaches zero (hover condition at very low altitude), or the propellant reserve has been exhausted. For the latter two cases, the equations of motion are further integrated until stage touchdown as the altitude reaches 0.

At this moment, the integrity of the stage is evaluated via addressing the velocity at landing together with the stage deviation from vertical, these values being compared to the ones imposed in the Requirements module. If all safety checks are passed, then a soft touchdown is obtained, and the corresponding constraint index

needed in relation (5) has a unitary value; thus, the Objective function is kept low.

4. Test Case and Results

The test case analyzed in this paper is considered as close as possible to the one studied in [15,16], such that a clear comparison can be made afterwards on the recovery mission impact on the microlauncher configuration.

4.1. Requirements and MDO Setup

The microlauncher’s main mission, optimized with the aid of the MDO algorithm, is the insertion of a 100 kg satellite into a 400 km altitude, circular, polar low Earth orbit, as it seems to be one of the best benchmarks that can be used. This is due to the increase in market demand for small satellite manufacturers to access low-altitude, high-inclination orbits, mainly for Earth observation missions. For this imposed orbit, the following target parameters are used in the definition of the main mission performance index (2):

- •

- Semimajor axis: ;

- •

- Orbit inclination: ;

- •

- Velocity (inertial): ;

- •

- Flight path angle: ;

For a circular orbit, the target eccentricity

has been replaced by two individual target parameters

and

, as it was discovered in [30] that using this formulation correlates to a reduction in convergence computational time. The Andøya Space Centre, found in Norway [38], has been considered as the reference launch and landing location in this study as it provides a clear launch corridor towards the north, has existing launch infrastructure, and has been used in the past for European-based space vehicles. The site has a longitude of

and latitude of

. For the launch direction, an initial track angle

was chosen [15,39].

Regarding the microlauncher architecture, a two-stage constant-diameter one is implemented in the current study, as it is seen as the most cost-effective and reduced complexity technical solution that can be used. Each stage will have one rocket engine, based on a LOX/methane propellant pair. The first stage will be recovered from the launch site, while the second stage is expendable and is not subjected to any further studies in this paper. In the future phases of the Nucleu project, a de-orbitation and stage fragmentation is envisioned, being performed with the aid of other in-house computational tools.

To enhance confidence in the proposed microlauncher concept, some safety margins are used during stage sizing, being 10% with respect to component length and 5% for second stage dry mass estimations (only for expendable concept). In addition, a propellant safety margin of 1% is considered for the reusable stage, which means that at touchdown, the first-stage tanks must have at least 1% of the overall propellant mass allocated for the recovery mission.

The fairing separation condition is based on a dynamic pressure formulation [15]. The optimal phase for fairing jettison is the coast period, as no thrust is being generated by the rocket engine; thus, the stability problem is minimal. This condition is somewhat restrictive, as it can force the reference trajectory to have suboptimal behavior, mainly because of the low duration of the coast phase. Thus, in this paper, the fairing separation is not strictly imposed to be realized during the coast flight, but rather when the dynamic pressure drops below the 500 Pa threshold (at this point, the altitude is very high).

The tuning parameters used for relations (7) and (8) are the following [15,30]:

Also, to ensure that the active guidance flight phases of the main mission are not over-evaluated, some restrictions are imposed for the aerodynamic angles (which are seen as control parameters in 3DOF environments, similar to the TVC deflection angles in 6DOF environments). Thus, the following intervals of operation are used [15]:

The imposed mission and launch vehicle constraints are very important as they dictate the path through which the optimal optimization variable vector is obtained. These constraints ensure that the payload is not damaged during the main mission of launcher (using data from payload user guides such as [40,41]), the vehicle is technical structurally feasible (maximum stage fineness ratios) and that the structural integrity of the recoverable stage is not affected during landing (soft touchdown standards [37]). A comprehensive list of all constraints is given in [15], the main ones implemented being:

- •

- Axial load factor below 11;

- •

- Normal load factor below 0.75;

- •

- Maximum stage fineness ratio of 10 (first stage w/o interstage) and 5 (second stage);

- •

- Rocket engine nozzle expansion ratios between 5 and 90;

- •

- Maximum landing velocity at first-stage touchdown of 3 m/s;

- •

- Maximum deviation from vertical position at first-stage touchdown of 2°.

The problem search space adopted is very important as it must be large enough such that the optimal solution is not excluded and is narrowed down iteratively during the optimization process. The bounds used are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Solution search space.

4.2. MDO-Proposed Microlauncher Concept

Regarding the convergence process of the MDO for the current setup, a total of 1152 genetic algorithm (ga) generations were needed. The size of the ga population was considered to be 10 times the number of optimization variables (thus 230 individuals) with an elite rate of 5%. The Matlab code (version R2024a) developed for the MDO algorithm is capable of parallel computing; thus, using a dedicated Intel i9-14900K workstation (24 CPU cores and 128 GB RAM), the total time needed to generate the best microlauncher concept was around 45 min (one iteration takes ~0.01 s to compute).

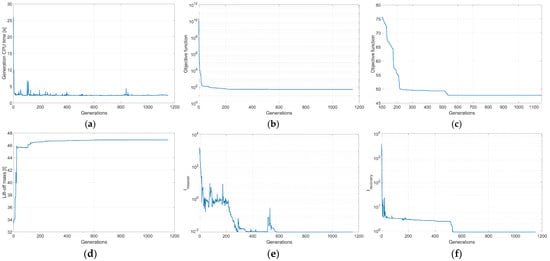

The entire MDO algorithm convergence process is depicted in Figure 4. Figure 4a depicts the CPU time needed for each generation of the genetic algorithm as the MDO advances the solution. The average duration was approximately 2.4 s per generation, with a clear spike during population initialization (first generation).

Figure 4.

MDO solution convergence: (a) generation CPU time; (b) objective function; (c) objective function (zoom); (d) microlauncher lift-off mass; (e) main mission performance index; (f) recovery mission performance index; (g) constraint index; (h) constraint index (zoom); (i) recovery mission allocated propellant mass (optimization variable number 17).

The evolution of the objective function as the number of generations increases can be seen in Figure 4b,c. The objective function values drop quickly in the initial several hundred generations, then gradually refine toward the optimal value.

By implementing the objective function as per Equation (1), the MDO process begins by assessing microlauncher concepts of reduced mass (

depicted in Figure 4d) to keep the numerical value

as low as possible. These microlauncher concepts are, of course, not feasible because the amount of propellant reserved for the main mission fails to achieve payload insertion into the designated target orbit (

has high values as seen in the first generations depicted in Figure 4e). Therefore, the MDO progressively adjusts the lift-off mass upwards (and sequentially the propellant mass) to gradually reduce the mission performance indices towards a null value. For example, the evolution of the recovery mission allocated propellant mass is depicted in Figure 4i.

The evolution of the recovery mission performance index

is illustrated in Figure 4f. This term is computed using Equations (3) and (4) and has a similar behavior to

. Its minimum value plateaus somewhat sooner than other terms that impact the objective function definition (at around generation 500), which implies that an improved solution could exist but has not yet been obtained. A further numerical assessment of this term will be realized during Section 4.3.

The last major parameter that appears in the formulation of the objective function is the constraint index

. The convergence process of this parameter is depicted in Figure 4g,h. The MDO appears to prioritize microlauncher configurations meeting all imposed constraints from the first generations, thereby focusing the 23-dimensional search space on the relevant region of the problem.

At the end of the MDO process (solution convergence is considered when no improvement has been reached after 100 consecutive generations [15,16]),

,

,

,

and

. The final set of optimization variables is numerically depicted in Table 5.

Table 5.

Final set of optimization variables for the reusable microlauncher concept.

It is important to note that no optimization method can ensure a true optimum for complex problems like the one addressed in this paper (microlauncher design optimization). Rather, the MDO tool seeks to produce highly performing designs that approach the optimum, even if mathematical proof of optimality is not possible.

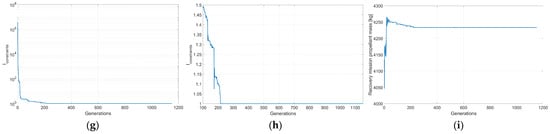

Having now access to the final optimization variables, one can generate the entire constructive solution of the microlauncher and its main performances. The main specifications of the microlauncher are given in Table 6, while Figure 5 presents the initial Matlab clean-configuration model alongside more comprehensive CAD representations (CATIA v5 software).

Table 6.

Specifications of the reusable microlauncher.

Figure 5.

Reusable microlauncher concept representations.

Table 7 presents the main weights and sizing aspects related to the upper structure of the reusable microlauncher concept. Because no initial assumptions were hardcoded for the payload shape and size, an intermediary cylindrical satellite was modeled (can also be seen in Figure 5), which provides enough clearance from the fairing (a 1.5 fineness ratio von Kármán ogive generation profile was implemented to ensure low drag implications).

Table 7.

Reusable microlauncher concept, upper structure weights, and sizing breakdown.

Next, the mass breakdown of the two stages is shown, being depicted in Table 8 for the expendable second stage and in Table 9 for the reusable first stage. For the case of the expendable stage, the stage exhibits a structural index (dry mass to total stage mass ratio) of roughly 11%, which is slightly conservative relative to the launchers currently in operation globally (below 10%). For the reusable first stage, the stage exhibits a structural index of approximately 16%, a significant increase in dry mass due to the additional components needed for stage recovery (which sums up to 2 tons in total and corresponds to almost half of the dry mass of the rest of the expendable concept components).

Table 8.

Mass breakdown of the second stage.

Table 9.

Mass breakdown of the first stage.

Of interest are also the propulsive data, Table 10 showcasing the engine-related performances of the first stage, while Table 11 presents the same data for the second stage (the data are extracted only for the microlauncher primary ascent mission). One can see the low-altitude influence on the rocket engine performance and the mean specific impulse of the first stage being 11% lower than for the second stage (310 compared to 349 s).

Table 10.

Primary propulsion characteristics of the first stage.

Table 11.

Primary propulsion characteristics of the second stage.

4.3. Reference Trajectories

In addition to the generation of the reusable microlauncher constructive solution, the MDO tool also provides a full mission analysis breakdown derived from the reference trajectories proposed (both for the main and recovery missions). The main mission (payload insertion into predefined orbit) is fully described with the aid of the key events and flight phases detailed in Table 12. The primary mission totals around 8 min from lift-off (492.7 s), showcasing the benefits of using a DATO profile.

Table 12.

Main mission analysis of the reusable microlauncher.

An additional key event that is presented in Table 12 is the maximum dynamic pressure moment (max q), which for the current microlauncher concept and reference trajectory occurs at approximately 10.8 km altitude, with a Mach number of approximately 2.2. At this moment, the mass of the microlauncher has significantly decreased to just 32.3 tons.

The altitude of first-stage separation is around 50 km, occurring at 74.66 s after lift-off. It can also be seen that the fairing jettison occurs after second stage ignition, meaning that the fairing is jettisoned during the secondary gravity turn. At payload separation (right before the satellite is decoupled from the upper structure), the microlauncher mass is 997.67 kg, corresponding to the second stage dry mass (782.39 kg) and the upper structure (without the fairing, which was previously separated—215.28 kg).

As mentioned before

, which corresponds to a fairly accurate orbit insertion (the ideal orbit insertion would correlate to

). The difference in imposed target parameters (mentioned in Section 4.1) obtained with the aid of the reference ascent trajectory is now presented in Table 13. The biggest deviation is that of orbit inclination, the obtained inclination being 90.00082° vs. the imposed 90°.

Table 13.

Errors in payload insertion for the main mission reference trajectory.

Up until this point, only details regarding the main mission have been provided. As mentioned before, in addition to optimizing the microlauncher’s main mission, the first-stage recovery mission (including the interstage) is also optimized. The first-stage recovery trajectory is indirectly optimized in the sense of minimizing the amount of propellant reserved and used during the recovery mission, based on the objective function formulation implemented in relation (1).

The amount of propellant reserved for the recovery mission can be directly computed from the optimization variable vector detailed in Table 5, being equal to

(4.2334 t, more precisely 4233.43 kg). From this total propellant mass, the following quantities are used during different flight phases:

- •

- Boostback maneuver: 3581.64 kg;

- •

- Reentry burn: 1.58 kg;

- •

- Landing burn: 605.17 kg;

- •

- Safety propellant mass: 42.33 kg (1% of );

- •

- Extra unused propellant: 2.71 kg.

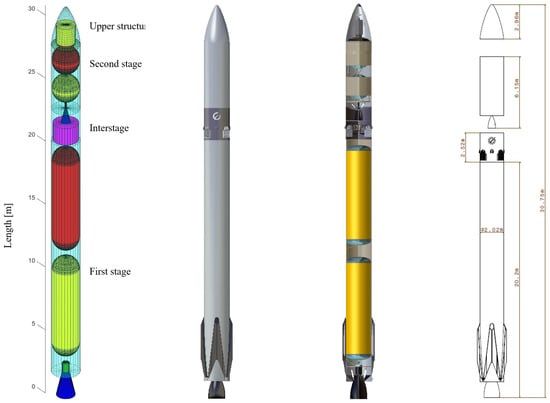

Analyzing the amount of propellant used on each phase, it can be seen that the boostback maneuver is the one that has the greatest impact on the quantity of propellant required during the first-stage RTLS recovery mission. This is understandable because at the time of stage separation, we have very strong initial conditions in the sense that the initial downrange (distance from launch site) is around 29.3 km, the initial velocity is 2.13 km/s, and the flight path angle is 52.71° (according to the data in Table 14). This correlates to a stage lateral velocity (in the direction opposite the launch site) of approximately 1.29 km/s. Thus, a significant amount of propellant is initially required to cancel this lateral velocity and reduce the downrange via the boostback burn.

Table 14.

RTLS recovery mission analysis for the reusable microlauncher.

The key flight phases and events that occur during the return to launch site recovery mission are presented in Table 14. The recovery mission totals approximately 7 min (414.96 s).

With the aim of reducing the propellant reserved for the recovery mission, the MDO chooses a reentry burn duration that is very small (where only 1.58 kg of propellant is used), thus most of the propellant mass available after the boostback maneuver is used during the landing burn (the optimization variable

as per Table 5).

This is mainly due to the fact that no constraints are imposed for the thermal loading or dynamic pressure aspects of atmospheric reentry, as such information is not yet available during preliminary conceptual design. This aspect will be further analyzed during advanced phases of design. For now, the addition of a heat shield (sized inside the Preliminary design module) is considered enough to successfully pass the reentry phase.

The value of 45.04 kg of propellant mass still on board the first stage at the time of touchdown is mostly due to the design requirements (1% safety margin). On top of this imposed value, a mass of approximately 2.71 kg of propellant was observed at solution convergence, which somewhat predicts that the global minimum has not yet been reached (this value could decrease to zero if further solution refinement is made, but the improvements would be very small). The 2.71 kg of extra propellant is quantified inside the

term (relation (3)) by the term

.

The other term that appears in the formulation of

is

which quantifies the landing position error with respect to the imposed landing site. At MDO solution convergence, a downrange (distance between the landing location and the launch location) of 87.4 m was obtained, being close to the imposed target (downrange = 0 m). However, it is observed that an “ideal” landing was not achieved. This is explainable by the fact that the considered control method on the yaw channel reached saturation.

During the recovery trajectory propagation, the RCS is used to rotate the first stage towards the imposed track angle

only after reaching a flight path angle

> 90 (to first fully cancel the lateral velocity of the first stage). Because the target flight path angle at the end of the boostback burn is

(details in Table 5), the amount of time in which the yaw channel (that modifies the track angle

) is very low, being in the few-second interval. The position error of 87 m indicates that an increased control authority is required if a fixed 0 m distance from the launch location to the landing location is desired, but is considered accurate enough at this stage, with the ACS being more than capable of correcting this error via small grid fin deflections.

As stated earlier at the beginning of Section 4.2, the value of the recovery mission performance index at convergence was

, which is computed with the aid of

and

06. Even though this value seems to be a high one (especially compared to the main mission performance index, which was

), this translates to an unused propellant mass of 2.71 kg (0.06% of total propellant mass reserved for stage recovery) and a positional landing error of 87.4 m, both of which are seen as reasonable for a preliminary conceptual design.

Regarding the constraint index, which appears in relation (1), it was mentioned earlier that, at MDO convergence,

. This means that all imposed constraints are respected (microlauncher main mission + first-stage recovery mission). At touchdown, the first-stage configuration velocity is 2.76 m/s (details in Table 14), while the deviation from vertical position is 0.13° (a 270° flight path angle is identical to the 90° flight path angle with which the microlauncher lifts off, but in opposite orientation—away from the ground vs. towards the ground).

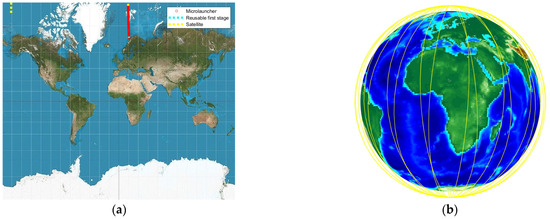

More insight is available if we decide to graphically present the reference trajectories in a 2D/3D environment. The most important representation is shown in Figure 6, depicting the altitude vs. downrange variation in the microlauncher during the main mission and the first stage during the recovery mission.

Figure 6.

Altitude vs. downrange representation: (a) microlauncher main mission + first-stage recovery mission; (b) recovery mission zoom.

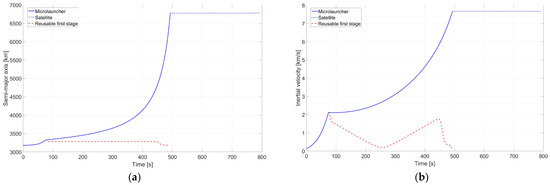

Additional parameters of interest variations are now depicted, showcasing the ones which influence the objective function score: semimajor axis (Figure 7a), inertial velocity (Figure 7b), flight path angle (Figure 7c), and orbit inclination (Figure 7d).

Figure 7.

MDO-proposed reference trajectories: (a) semimajor axis variation with time; (b) inertial velocity variation with time; (c) flight path angle variation with time; (d) orbit inclination variation with time.

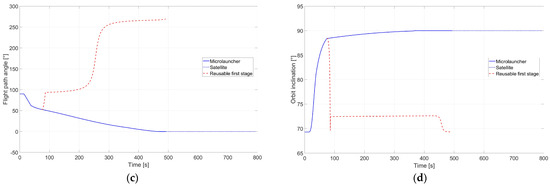

The quasi-constant behavior of the payload/satellite evolution after separation from the microlauncher, shown in Figure 7a–d, confirms the successful accomplishment of the main mission. Related to the satellite evolution, one can see in Figure 8b the full coverage that a polar LEO can have, justifying its popularity among Earth observation satellites. Additionally, the Mercator projection shown in Figure 8a also presents the evolution of the microlauncher and first stage during its missions.

Figure 8.

(a) Mercator projection; (b) satellite evolution (from insertion up to 24 h later).

4.4. Cost Estimates

One important aspect that must be assessed regarding the partially reusable microlauncher concept defined earlier in Section 4.3 is the estimation of all associated costs that occur during the effective operation of the launch vehicle. As mentioned earlier, the MDO algorithm comprises five primary disciplinary modules, with only four being actively used in the iterative optimization process.

The last main module (Cost Estimation) is executed post solution convergence to reduce the computational time of the MDO algorithm. Here, a list of development, production, and operation costs is provided, accompanied by an estimation of the overall costs (and corresponding price per launch) during its entire operational lifetime. A full list of input data used to generate the costs is given in [15], the main ones being the following:

- •

- Annual launch rate: 12 per year;

- •

- Operational lifetime: 20 years (required to determine the total number of launches necessary to amortize the development costs);

- •

- Number of first stage uses: Five (a refurbishment process occurs before each reflight);

- •

- Monetary evaluation of MYr (Man-Year): EUR 24,000 (based on Romanian salaries).

The full cost breakdown associated with the RTLS partially reusable microlauncher is given in Table 15.

Table 15.

Cost estimates of the partially reusable microlauncher.

From the cost data presented in Table 15, it can be observed that the development cost is very high, being around 1.2 billion euros. By using a 240-launch amortization period (one launch per month for 20 years), the costs are somewhat manageable, but still amount to around 47% of the total estimated cost per launch (EUR 5.02 M of 10.65 M).

The average production cost of the reusable microlauncher is almost a third of the cost associated with a brand-new launch vehicle (EUR 4.37 M vs. EUR 13.16 M), showcasing the economic benefit of reusing the first stage (which is much larger and more expensive compared to the second stage). Still, the production costs amount to approximately 41% of the total cost per launch.

The rest of the costs are given by the operations (EUR 680 k) and refurbishment (EUR 580 k) procedures, and amount to 12% of the total estimated cost per launch. Considering that the payload inserted into LEO is just 100 kg, the resulting payload cost per kg is EUR 106.5 k.

5. Reusability and Recovery Location Impact on the Microlauncher

During Section 4, a possible reusable microlauncher concept was generated for which the first stage is recovered via a return to launch site mission. This concept was analyzed in a standalone environment. To properly assess the feasibility of such a microlauncher, one must compare the constructive solution, its performances, and most importantly, the associated costs with those of a partially reusable microlauncher concept in which the first-stage assembly is recovered via an alternative recovery mission. In paper [15], a similar analysis to the one in the current paper was made for a downrange recovery microlauncher concept, while in [16] an expendable microlauncher having the same main mission was optimized. For the formulation of a valid conclusion, one must compare all three concepts.

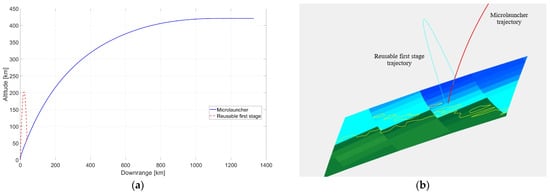

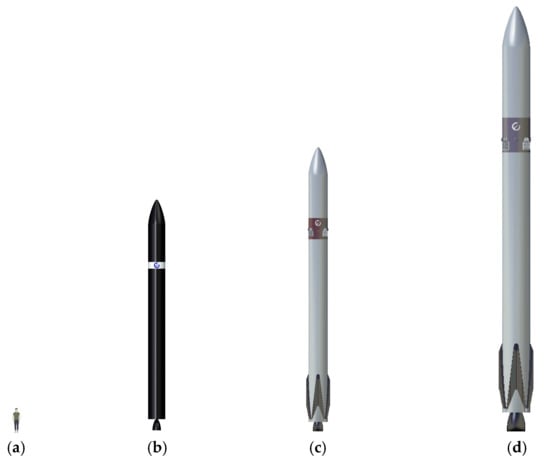

A graphical comparison (CAD models) is realized in Figure 9 for the three microlauncher concepts, which have been optimized to accomplish the main mission detailed in this paper (insertion of a 100 kg payload into a 400 km altitude, circular, polar low Earth orbit with a launch from Andøya Space Centre).

Figure 9.

Microlauncher concepts CAD comparison: (a) human for scale (1.8 m height); (b) expendable concept [16]; (c) downrange recovery concept [15]; (d) RTLS recovery concept (current paper).

An average human with a height of 1.8 m is also depicted in Figure 9 to better understand the scale of the microlaunchers. One can see the fact that the return to launch site recovery mission (RTLS) corresponds to a microlauncher concept that has much greater dimensions (and mass), making it fall more into the medium-sized launch vehicle category.

The next comparison which must be made is of course of the main specification associated with each microlauncher concept. These are presented in Table 16. A lot of valuable information related to the feasibility of a return to the launch site, partially reusable microlauncher, can be gathered by numerically comparing the data in Table 16.

Table 16.

Microlauncher concepts comparison, specifications.

A strong increase in lift-off mass can be seen between the three concepts analyzed. Between the expendable concept and the first reusable concept (downrange recovery mission for the first stage), the difference is around 60%, while between the last two concepts, the difference is around 216%. The main reason behind the steep increase in lift of mass is the need for extra propellant mass reserved for the recovery mission. This propellant mass was just shy of 200 kg for the downrange recovery concept, while for the return to launch site recovery microlauncher concept, the value jumps to 4.2 tons. Of interest for possible future papers is thus the investigation of the influence of maximum downrange (for the location of landing pad vs. launch pad) on the propellant mass needed to recover the first-stage assembly.

The mass difference in the microlauncher configurations will, of course, translate into different sizes of the main assemblies (upper structure, second stage, and first stage). As the first stage (without interstage) has a maximum fineness ratio implemented as a constraint (L/D ≤ 10), the higher propellant mass will translate first into a greater diameter and then into a higher stage length. One can see that the diameter of the expendable concept stage was just 1.22 m, while the reusability aspect of the launcher increased this value to 1.39 m (downrange recovery) and to a whopping 2.02 m (return to launch site recovery).

As the reusable concept increases in diameter and mass, the mass of any additional system needed for recovery (ACS, RCS, elongated interstage, landing system and heat shield) also increase, which means that more propellant mass must be used onboard the first stage and thus, the values keep adding up until the microlauncher concept cannot be considered “micro” anymore (mass increase has a snowball effect).

The escalating mass effect of the RTLS reusable microlauncher concept also translates into very powerful rocket engines that are needed to generate the desired thrust, values in the order of MN appearing for the first stage engine (1.18 MN as shown in Table 16). Because the biggest development costs are associated with engine development and testing [15,26], this will translate into a very high development amortization cost and, in the end, into a very high total cost per launch. One can observe from Table 16 that the total cost per launch is more than double for the RTLS reusable microlauncher compared to the downrange recovery microlauncher concept. Thus, from an economic point of view, a return to launch site first-stage recovery mission is not feasible for a microlauncher (at least not for a reduced number of launches per year as envisioned in this paper). For higher payload masses, the fact that Falcon 9 [6] still employs such a recovery method validates the feasibility of RTLS for medium and large launch vehicles.

The cost estimates depicted in Table 15 and Table 16 assume that the launch schedule envisioned for all of the microlauncher concepts is one launch per month. This value has been taken somewhat conservatively because of the low level of maturity reached by reusable launchers at the European level. By increasing the launch rate to 100 launches per year (by more than eight times), the R&D amortization per launch of the RTLS microlauncher concept drops to EUR 0.6 M, which decreases the total cost per launch to under EUR 5 M, a value which could justify its use versus the downrange recovery microlauncher concept. This would imply that RTLS could be feasible only for very high launch rates, in the order of at least two per week, which realistically is not achievable by most players in the launch sector market (except SpaceX).

Even though the RTLS recovery mission is not feasible to be implemented for a microlauncher concept due to higher costs (a typical one launch per month schedule), the downrange recovery has the potential to reduce to overall costs of small launch vehicles, the final cost per launch being 8% lower compared to an expendable concept (with five times first stage uses assumption).

6. Conclusions

This paper has investigated the possibility of implementing a return to launch site recovery mission of the first stage in the case of a partially reusable two-stage LOX/methane microlauncher. The microlauncher concept was generated with the aid of a multidisciplinary optimization (MDO) algorithm, which has yielded promising results in previous papers regarding expendable microlauncher concepts and reusable microlauncher concepts that employ a downrange recovery mission of the first stage [15,16].

The microlauncher optimization was realized considering a mass minimization objective function, in association with a main mission and recovery mission accomplishment. Several flight phases were modeled in a 3DOF environment for which details were given throughout the paper. Besides the constructive solution generation, the launch vehicle performances were presented, together with several visual representations for the reference trajectories that must be followed.

The final Section addresses the feasibility of an RTLS recovery mission for a microlauncher by means of direct performance comparison versus an expendable microlauncher and a partially reusable microlauncher in which a downrange recovery is implemented. Because of the high propellant mass needed to return the first stage towards the launch site (mainly during the boostback maneuver), the lift-off mass of the RTLS concept microlauncher is more than triple compared to the downrange recovery microlauncher (46.88 vs. 14.83 t) and five times more compared to the expendable concept (9.35 t).

The expected cost per launch is also double in the case of RTLS compared to the downrange recovery method (EUR 10.65 million vs. EUR 5.17 million) for the insertion of a 100 kg payload into a 400 km altitude, circular, polar low Earth orbit (with a launch from Andøya Space Centre). Thus, it is concluded that a return to the launch site recovery method is not economically feasible to be implemented for a microlauncher concept. This conclusion is valid only for launch vehicles of small mass and dimensions, as the snowball effect of the extra propellant mass needed for stage recovery has a multiplicative effect at this scale. The RTLS would be justified only if the launch rate were increased by a factor of at least eight compared to the downrange recovery microlauncher, assumption which is out of reach for most companies involved in the satellite launcher sector.

On the other hand, a partially reusable microlauncher concept for which the first stage is recovered from a secondary location (downrange recovery) is feasible, providing even lower costs than the expendable concept (EUR 51.7 vs. 55.1 k/kg).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-I.O., T.-P.A., O.-I.P., G.I., A.P. and I.B.; methodology, A.-I.O., T.-P.A., O.-I.P., G.I., A.P. and I.B.; software, A.-I.O., T.-P.A. and G.I.; validation, A.-I.O., T.-P.A., O.-I.P., G.I., A.P. and I.B.; formal analysis, A.-I.O. and T.-P.A.; investigation, A.-I.O. and T.-P.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-I.O.; writing—review and editing, A.-I.O., T.-P.A., O.-I.P., G.I., A.P. and I.B.; project administration, A.-I.O.; funding acquisition, A.-I.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work presented in this study has received funding from the Romanian Nucleu Program, project PN 23 17 07 02.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- De Concini, A.; Toth, J. The future of the European space sector. In How to Leverage Europe’s Technological Leadership and Boost Investments for Space Ventures; European Investment Bank: Luxembourg, 2019; Report for the European Commission. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresia, K.; Jentzsch, S.; Waxenegger-Wilfing, G.; Dos Santos Hahn, R.; Deeken, J.; Oschwald, M.; Mota, F. Multidisciplinary Design Optimization of Reusable Launch Vehicles for Different Propellants and Objectives. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2021, 58, 1017–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brevault, L.; Balesdent, M.; Hebbal, A. Multi-objective Multidisciplinary Design Optimization approach for partially Reusable Launch Vehicle design. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2020, 57, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brevault, L.; Balesdent, M.; Hebbal, A.; Patureau de Mirand, A. Surrogate Model-Based Multi-Objective MDO Approach for Partially Reusable Launch Vehicle Design. In Proceedings of the AIAA Science and Technology Forum and Exposition, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietlein, I.; Bussler, L.; Stappert, S.; Wilken, J.; Sippel, M. Overview of system study on recovery methods for reusable first stages of future European launchers. CEAS Space J. 2025, 17, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SpaceX. Falcon 9—First Orbital Class Rocket Capable of Reflight. Available online: https://www.spacex.com/vehicles/falcon-9/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Blue Origin. New Glenn NG-2 Mission. Available online: https://www.blueorigin.com/missions/ng-2 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Bussler, L.; Dietlein, I.; Sippel, M. Comparative analyses of European horizontal-landing reusable first stage concepts. CEAS Space J. 2025, 17, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilken, J.; Herberhold, M.; Sippel, M. Options for future European reusable booster stages: Evaluation and comparison of VTHL and VTVL costs. CEAS Space J. 2025, 17, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, P. Miura 5 The European and Reusable Microlauncher for CubeSats and Small Satellites. In Proceedings of the Small Satellites Conference, Logan, UT, USA, 1–6 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Frenoy, O.; Hiraiwa, T. Concept of Operations—CALLISTO Demonstrator. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference for Aeronautics and Space Sciences, Madrid, Spain, 1–4 July 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, J.; Hassin, J. Technology Acceleration Process for the THEMIS Low Cost and Reusable Prototype. In Proceedings of the 8th European Conference for Aeronautics and Space Sciences, Madrid, Spain, 1–4 July 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldyn, P.; Marwege, A.; Riehmer, J.; Klevanski, J.; Gülhan, A. Preliminary Design of Expendable and Reusable Mixed-Staged Launch Vehicles. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2025, 62, 955–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Space Economy. A Guide to Europe’s Commercial Launch Providers. Available online: https://newspaceeconomy.ca/2025/06/30/a-guide-to-europes-commercial-launch-companies/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Onel, A.-I.; Afilipoae, T.-P.; Popescu, O.-I.; Ichim, G.; Popescu, A. Multidisciplinary Design Optimization of a Two-Stage LOX/Methane Partially Reusable Microlauncher. Aerospace 2025, 12, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onel, A.I.; Afilipoae, T.P.; Popescu, O.I.; Popescu, A.; Pricop, M.V.; Bunescu, I.; Hothazie, M.V. Multidisciplinary design optimization of a two-stage LOX/methane microlauncher. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3315, 190006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue Origin. New Shepard. Available online: https://www.blueorigin.com/new-shepard (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Pempie, P.; Froehlich, T.; Vernin, H. LOX/methane and LOX/kerosene high thrust engine trade-off. In Proceedings of the 37th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 8–11 July 2001. AIAA Paper 2001-3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernin, H.; Pempie, P. LOX/CH4 and LOX/LH2 heavy launch vehicle comparison. In Proceedings of the 45th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Denver, CO, USA, 2–5 August 2009. AIAA Paper 2009-5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MathWorks. MATLAB Documentation. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/help/matlab/index.html (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Onel, A.I. Optimal Solutions for Small Launchers. Ph.D. Thesis, Polytechnic University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Castellini, F. Multidisciplinary Design Optimization for Expendable Launch Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico Di Milano, Milano, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kesteren, M.W.; Zandbergen, B.T.C. Design and Analysis of an Airborne, solid Propelled, Nanosatellite Launch Vehicle using Multidisciplinary Design Optimization. In Proceedings of the 6th European Conference for Aeronautics and Space Sciences, Krakow, Poland, 29 June–3 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Onel, A.I.; Ichim, G.; Matei, I.; Popescu, O.I.; Popescu, A.; Afilipoae, T.P. CFD Investigation of a Grid Fin Based Aerodynamic Control System for a Microlauncher Reusable First Stage. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference of Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics, Crete, Greece, 11–17 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Onel, A.I.; Ichim, G.; Matei, I.; Popescu, O.I.; Popescu, A. CFD Investigation on the Influence of a Folded Landing System for a Microlauncher Reusable First Stage. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference of Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics, Crete, Greece, 11–17 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, E.K. Handbook of Cost Engineering and Design of Space Transportation Systems; TransCostSystems: Ottobrunn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stappert, S.; Wilken, J.; Calabuig, G.J.D.; Sippel, M. Evaluation of Parametric Cost Estimation in the Preliminary Design Phase of Reusable Launch Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference for Aeronautics & Space Sciences (EUCASS), Lille, France, 1–27 June 2022. Paper EUCASS2022-4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenthe, N.T. SOLSTICE: Small Orbital Launch Systems, a Tentative Initial Cost Estimate. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Balesdent, M. Multidisciplinary Design Optimization of Launch Vehicles. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecole Centrale de Nantes, Nantes, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Onel, A.I.; Chelaru, T.V. Parametric Analysis of a Two-Stage Small Launcher Using a MDO Approach. INCAS Bull. 2022, 14, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Sabarish, B.A. Analysis of Distance Measures in Spatial Trajectory Data Clustering. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on Emerging Research Areas on “Computing & Communication Systems for a Fourth Industrial Revolution”, Kanjirapally, India, 14–16 December 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, F.; Ariffin, W.N.M.; Jusoh, M.S.; Putri, E.P. A Review of Genetic Algorithm: Operations and Applications. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 40, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoch, S.; Chauhan, S.S.; Kumar, V. A Review on Genetic Algorithm: Past, Present, and Future. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 8091–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence; Michigan Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäck, T. Evolutionary Algorithms in Theory and Practice: Evolution Strategies, Evolutionary Programming, Genetic Algorithms; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Clark, K.; Unwin, M.; Zackrisson, J.; Shiroma, W.A.; Akagi, J.M.; Maynard, K.; Garner, P.; Boccia, L.; Amendola, G.; et al. Antennas for Modern Small Satellites. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2009, 51, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElonX. Launch and Landing Profiles. Available online: https://www.elonx.net/launch-and-landing-profiles/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Andoya Space. Orbital Launch Services. Available online: https://andoyaspace.no/spaceport/ (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- OrbiterWiki. Launch Azimuth. Available online: https://www.orbiterwiki.org/wiki/Launch_Azimuth (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- SpaceX. Falcon User’s Guide Version 8-March 2025. Available online: https://www.spacex.com/assets/media/falcon-users-guide-2025-05-09.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Rocket Lab. Electron Payload User Guide Version 8.0; Rocket Lab: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://rocketlabcorp.com/assets/Rocket-Lab-Electron-Payload-User-Guide-8.0.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.