Abstract

This article proposes a method to diminish the horizontal position drift in the absence of GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System) signals experienced by the VNS (Visual Navigation System) installed onboard a UAV (Unmanned Air Vehicle) by supplementing its pose estimation non-linear optimizations with priors based on the outputs of the INS (Inertial Navigation System). The method is inspired by a PI (Proportional Integral) control loop, in which the attitude and altitude inertial outputs act as targets to ensure that the visual estimations do not deviate past certain thresholds from their inertial counterparts. The resulting IA-VNS (Inertially Assisted Visual Navigation System) achieves major reductions in the horizontal position drift inherent to the GNSS-Denied navigation of autonomous UAVs. Stochastic high-fidelity Monte Carlo simulations of two representative scenarios involving the loss of GNSS signals are employed to evaluate the results and to analyze their sensitivity to the terrain type overflown by the aircraft. The authors release the C++ implementation of both the navigation algorithms and the high-fidelity simulation as open-source software.

1. Mathematical Notation

Any variable with a hat accent refers to its (inertial) estimated value, and with a circular accent to its (visual) estimated value. In the case of vectors, which are displayed in bold (e.g., ), other employed symbols include the wide hat , which refers to the skew-symmetric form, the bar , which represents the vector homogeneous coordinates, and the double vertical bars , which refer to the norm. In the case of scalars, the vertical bars refer to the absolute value. When employing attitudes and rigid body poses (e.g., and ), the asterisk superindex refers to the conjugate, their concatenation and multiplication are represented by and , respectively, and and refer to the plus and minus operators.

This article includes various non-linear optimizations solved in the spaces of both rigid body rotations and full motions, instead of Euclidean spaces. Hence, it relies on the Lie algebra of the special orthogonal group of , known as , and that of the special Euclidean group of , represented by , in particular what refers to the groups actions, concatenations, perturbations, and Jacobians, as well as with their tangent spaces (the rotation vector and angular velocity for rotations, the transform vector and twist for motions). Refs. [1,2,3] are recommended as references.

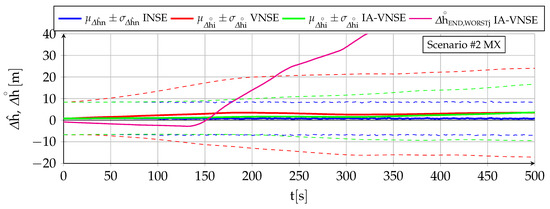

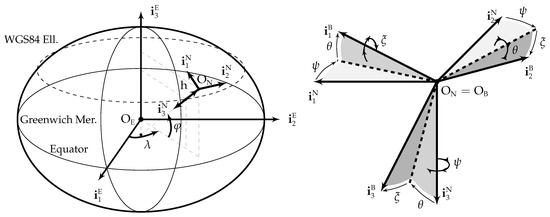

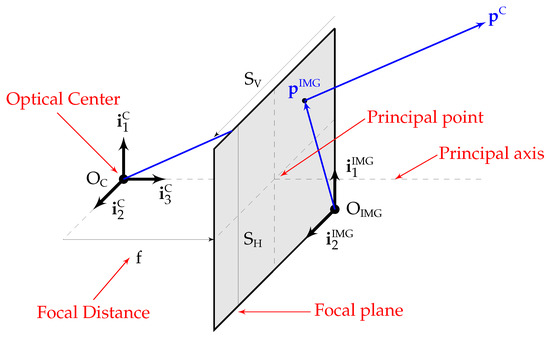

Five different reference frames are employed in this article: the ECEF frame (centered at the Earth center of mass , with pointing towards the geodetic North along the Earth rotation axis, contained in both the Equator and zero longitude planes, and orthogonal to and forming a right handed system), the NED frame (centered at the aircraft center of mass , with axes aligned with the geodetic North, East, and Down directions), the body frame (centered at the aircraft center of mass , with contained in the plane of symmetry of the aircraft pointing forward along a fixed direction, contained in the plane of symmetry of the aircraft, normal to and pointing downward, and orthogonal to both in such a way that they form a right hand system), the camera frame (centered at the optical center , defined in Appendix A, with located in the camera principal axis pointing forward, and parallel to the focal plane), and the image frame (two-dimensional frame centered at the sensor corner with axes parallel to the sensor borders). The first three frames are graphically depicted in Figure 1, while and can be visualized in Appendix A.

Figure 1.

ECEF (), NED (), and body () reference frames.

Superindexes are employed over vectors to specify the reference frame in which they are viewed (e.g., refers to ground velocity viewed in , while is the same vector but viewed in ). Subindexes may be employed to clarify the meaning of the variable or vector, such as in for air velocity instead of the ground velocity , in which case the subindex is either an acronym or its meaning is clearly explained when first introduced. Subindexes may also refer to a given component of a vector, e.g., refers to the second component of . In addition, where two reference frames appear as subindexes to a vector, it means that the vector goes from the first frame to the second. For example, refers to the angular velocity from the frame to the frame viewed in . Table 1 summarizes the notation employed in this article.

Table 1.

Mathematical notation.

In addition, there exist various indexes that appear as subindexes: n identifies a discrete time instant () for the inertial estimations, s () refers to the sensor outputs, i identifies an image or frame (), and k is employed for the keyframes used to generate the map or terrain structure. Other employed subindexes are l for the steps of the various iteration processes that take place, and j for the features and associated 3D points. With respect to superindexes, two stars represent the reprojection only solution, while two circles identify a target.

2. Introduction and Outline

This article focuses on the need to develop navigation systems capable of diminishing the position drift inherent to the flight in GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite System)-Denied conditions of an autonomous fixed wing aircraft so it has a higher probability of reaching the vicinity of a recovery point, from where it can be landed by remote control.

The article proposes a method that employs the inertial navigation outputs to improve the accuracy of VO (Visual Odometry) algorithms, which rely on the images of the Earth surface provided by a down looking camera rigidly attached to the aircraft structure, resulting in major improvements in horizontal position estimation accuracy over what can be achieved by standalone inertial or visual navigation systems. In contrast with most visual inertial methods found in the literature, which focus on short term GNSS-Denied navigation of ground vehicles, robots, and multi-rotors, the proposed algorithms are primarily intended for the long distance GNSS-Denied navigation of autonomous fixed wing aircraft.

Section 3 describes the article objectives, novelty, and main applications. When processing a new image, VO pipelines include a distinct phase known as pose optimization, pose refinement, or motion-only bundle adjustment, which estimates the camera pose (position plus attitude) based on previously estimated positions for the identified terrain features, both as ECEF 3D coordinates, as well as 2D coordinates of their projected location in the current image. Section 4 reviews the pose optimization algorithm when part of a standalone visual navigation system that can only rely on periodically generated images, while Section 5 proposes improvements to take advantage of the availability of aircraft pose estimations provided by an inertial navigation system.

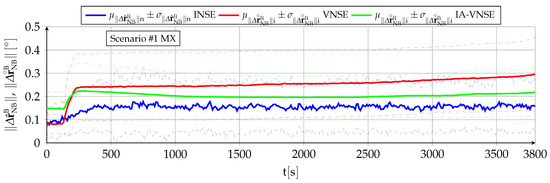

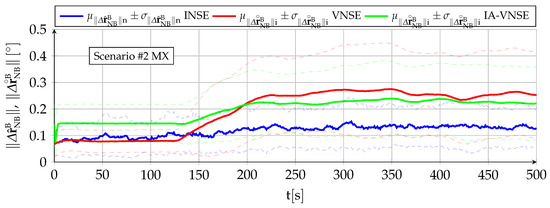

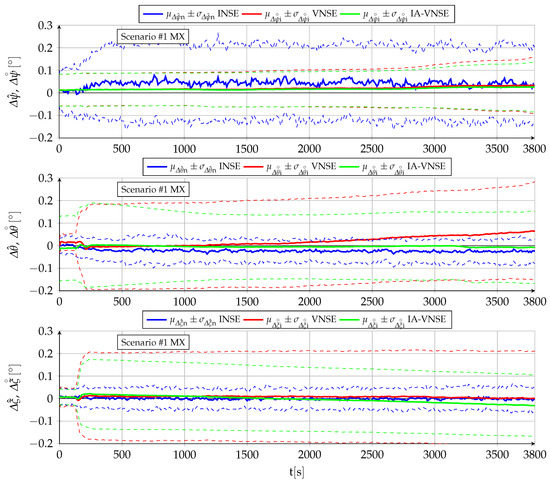

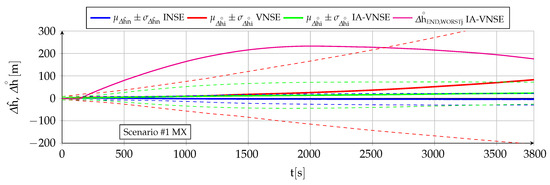

Section 6 introduces the stochastic high-fidelity simulation employed to evaluate the navigation results by means of Monte Carlo executions of two scenarios representative of the challenges of GNSS-Denied navigation. The results obtained when applying the proposed algorithms to these two GNSS-Denied scenarios are described in Section 7, comparing them with those achieved by standalone inertial and visual systems. Section 8 discusses the sensitivity of the estimations to the type of terrain overflown by the aircraft, as the terrain texture (or lack of) and its elevation relief are key factors on the ability of the visual algorithms to detect and track terrain features. Last, the results are summarized for convenience in Section 9, while Section 10 provides a short conclusion.

Following a list of acronyms, the article concludes with three appendices. Appendix A provides a detailed description of the concept of optical flow, which is indispensable for the pose optimization algorithms of Section 4 and Section 5. Appendix B contains an introduction to GNSS-Denied navigation and its challenges, together with reviews of the state-of-the-art in two of the most promising routes to diminish its negative effects, such as visual odometry (VO) and visual inertial odometry (VIO). Last, Appendix C describes the different algorithms within Semi-Direct Visual Odometry (SVO) [4,5], a publicly available VO pipeline employed in this article, both by itself in Section 4 when relying exclusively on the images, and in the proposed improvements of Section 5 taking advantage of the inertial estimations.

3. Objective, Novelty, and Application

The main objective of this article is to improve the GNSS-Denied navigation capabilities of autonomous aircraft, so in case GNSS signals become unavailable, they can continue their mission or safely fly to a predetermined recovery location. To do so, the proposed approach combines two different navigation algorithms, employing the outputs of an INS (Inertial Navigation System) specifically designed for the flight without GNSS signals of an autonomous fixed wing low SWaP (Size, Weight, and Power) aircraft [6] to diminish the horizontal position drift generated by a VNS (Visual Navigation System) that relies on an advanced visual odometry pipeline, such as SVO [4,5]. Note that the INS makes use of all onboard sensors except the camera, while the VNS relies exclusively on the images provided by the camera.

As shown in Section 7, each of the two systems by itself incurs in unrestricted and excessive horizontal position drift that renders them inappropriate for long term GNSS-Denied navigation, but for different reasons: while in the INS the drift is the result of integrating the bounded ground velocity estimations without absolute position observations, that of the VNS originates on the slow but continuous accumulation of estimation errors between consecutive frames. The two systems however differ in their estimations of the aircraft attitude and altitude, as they are bounded for the INS but also drift in the case of the VNS. The proposed approach modifies the VNS so in addition to the images it can also accept as inputs the INS bounded attitude and altitude outputs, converting it into an Inertially Assisted VNS or IA-VNS with vastly improved horizontal position estimation capabilities.

The VIO solutions listed in Appendix B are quite generic with respect to the platforms on which they are mounted, with most applications focused on ground vehicles, indoor robots, and multi-rotors, as well as with respect to the employed sensors, which are usually restricted to the gyroscopes and accelerometers, together with one or more cameras. This article focuses on an specific case (long distance GNSS-Denied turbulent flight of fixed wing aircraft), and, as such, is simultaneously more restrictive but also takes advantage of the sensors already present onboard these platforms, such as magnetometers, Pitot tube, and air vanes. In addition, and unlike the existing VIO packages, the proposed solution assumes that GNSS signals are present at the beginning of the flight. As described in detail in [6], these are key to the obtainment of the bounded attitude and altitude INS outputs on which the proposed IA-VNS relies.

The proposed method represents a novel approach to diminish the pose drift of a VO pipeline by supplementing its pose estimation non-linear optimizations with priors based on the bounded attitude and altitude outputs of a GNSS-Denied inertial filter. The method is inspired in a PI (Proportional Integral) control loop, in which the inertial attitude and altitude outputs act as targets to ensure that the visual estimations do not deviate in excess from their inertial counterparts, resulting in major reductions to not only the visual attitude and altitude estimation errors, but also to the drift in horizontal position.

This article proves that inertial and visual navigation systems can be combined in such a way that the resulting long term GNSS-Denied horizontal position drift is significantly smaller than what can be obtained by either system individually. In the case that GNSS signals become unavailable in mid flight, GNSS-Denied navigation is required for the platform to complete its mission or return to base without the absolute position and ground velocity observations provided by GNSS receivers. As shown in the following sections, the proposed system can significantly increase the possibilities of the aircraft safely reaching the vicinity of the intended recovery location, from where it can be landed by remote control.

4. Pose Optimization within Visual Odometry

Visual navigation, also known as visual odometry or VO, relies on images of the Earth’s surface generated by an onboard camera to incrementally estimate the aircraft pose (position plus attitude) based on the changes that its motion induces on the images, without the assistance of image databases or the observations of any other onboard sensors. As it does not rely on GNSS signals, it is considered an alternative to GNSS-Denied inertial navigation, although it also incurs in an unrestricted horizontal position drift. Appendix B.2 provides an overview of various VO pipelines within the broader context of the problems associated to GNSS-Denied navigation and the research paths most likely to diminish them (Appendix B).

This article employs SVO (Semi-Direct Visual Odometry) [4,5], a state-of-the-art publicly available VO pipeline, as a baseline on which to apply the proposed improvements based on the availability of inertial estimations of the aircraft pose. Although Appendix C describes the various threads and processes within SVO, the focus of the proposed improvements within Section 5 lies in the pose optimization phase, which is the only one described in detail in this article. Note that other VO pipelines also make use of similar pose optimization algorithms.

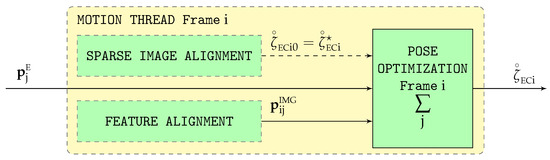

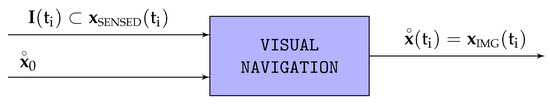

Graphically depicted in Figure 2, pose optimization is executed for every new frame i and estimates the pose between the ECEF () and camera () frames (). It requires the following inputs:

Figure 2.

Pose optimization flow diagram.

- The ECEF terrain 3D coordinates of all features j visible in the image () obtained by the structure optimization phase (Appendix C) corresponding to the previous image. These terrain 3D coordinates are known as the terrain map, and constitute a side product generated by VO pipelines.

- The 2D position of the same features j within the current image i () supplied by the previous feature alignment phase (Appendix C).

- The rough estimation of the ECEF to camera pose for the current frame i provided by the sparse image alignment phase (Appendix C), which acts as the initial value for the camera pose () to be refined by iteration.

The pose optimization algorithm, also known as pose refinement or motion-only bundle adjustment, estimates the camera pose by minimizing the reprojection error of the different features. Pose optimization relies exclusively on the information obtained from the images generated by the onboard camera, and is described in detail to act as a baseline on which to apply in Section 5 the proposed improvements enabled by the availability of additional pose estimations generated by an inertial navigation system or INS.

The reprojection error , a function of the estimated ECEF to camera pose for image i (), is defined in (1) as the sum for each feature terrain 3D point j of the norm of the difference between the camera projection of the ECEF coordinates transformed into the camera frame and the image coordinates . Note that represents the transformation of a point from frame B to frame A, as described in [1], and the camera projection is defined in Appendix A.

This problem can be solved by means of an iterative Gauss-Newton gradient descent process [1,7]. Given an initial camera pose estimation taken from the sparse image alignment result (, Figure 2), each iteration step l minimizes (2) and advances the estimated solution by means of (3) until the step diminution of the reprojection error falls below a given threshold . Note that represents the estimated tangent space incremental ECEF to camera pose (transform vector) viewed in the camera frame for image i and iteration l, and represent the plus and concatenation operators, and refers to the capitalized exponential function [1,3]. Additionally, note that, while and present in (1) and (2) are both positive scalars, the feature j reprojection error that appears in (2) is an vector.

Each represents the update to the camera pose viewed in the local camera frame , which is obtained by following the process described in [1,7], and results in (4), where (5) is the optical flow for image i, iteration step l, and feature j obtained in Appendix A:

In order to protect the resulting pose from the possible presence of outliers in either the feature terrain 3D points or their image projections , it is better to replace the above squared error or mean estimator by a more robust M-estimator, such as the bisquare or Tukey estimator [8,9]. The error to be minimized in each iteration step is then given by (6), where the Tukey error function can be found in [9].

A similar process to that employed above leads to the solution (7), where the Tukey weight function is also provided by [9]:

5. Proposed Pose Optimization within Visual Inertial Odometry

Lacking any absolute references, all visual odometry (VO) pipelines gradually accumulate errors in each of the six dimensions of the estimated ECEF to vehicle body pose . The resulting estimation error drift is described in Section 7 for the specific case of SVO, which is introduced in Appendix C, and whose pose optimization phase is described in Section 4.

This article proposes a method to improve the pose estimation capabilities of visual odometry pipelines by supplementing them with the outputs provided by an inertial navigation system. Taking the pose optimization algorithm of SVO (Section 4) as a baseline, this section describes the proposed improvements, while Section 7 explains the results obtained when applying the algorithms to two scenarios representative of GNSS-Denied navigation (Section 6).

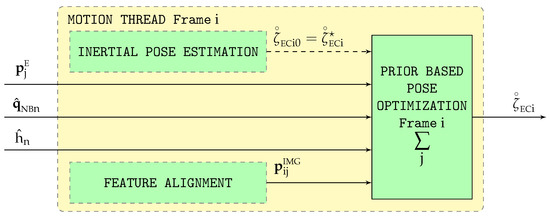

If accurate estimations of attitude and altitude can be provided by an inertial navigation system (INS) such as that described in [6], these can be employed to ensure that the visual estimations for body attitude and vertical position ( and , part of the body pose ) do not deviate in excess from their inertial counterparts and , improving their accuracy. This process is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Prior-based pose optimization flow diagram.

The inertial estimations () should not replace the visual ones () within SVO, as this would destabilize the visual pipeline preventing its convergence, but just act as anchors so the visual estimations oscillate freely as a result of the multiple SVO optimizations but without drifting from the vicinity of the anchors. This section shows how to modify the cost function within the iterative Gauss-Newton gradient descent pose optimization phase (Section 4) so it can take advantage of the inertial outputs. It is necessary to remark that, as indicated in Section 6, the inertial estimations (denoted by the subindex n) operate at a much higher rate than the visual ones (denoted by the subindex i).

5.1. Rationale for the Introduction of Priors

The prior based pose optimization process starts by executing exactly the same pose optimization described in Section 4, which seeks to obtain the ECEF to camera pose that minimizes the reprojection error (1). The iterative optimization results in a series of tangent space updates (7), where i identifies the image and l indicates the iteration step. The camera pose is then advanced per (3) until the step diminution of the reprojection error falls below a certain threshold .

The resulting ECEF to camera pose, , is marked with the superindex to indicate that it is the reprojection only solution, resulting in . Its concatenation with the constant body to camera pose results in the reprojected ECEF to body pose (note that a single asterisk superindex applied to a pose refers to its conjugate or inverse, and that the concatenation and multiplication operators are equivalent for rigid body poses):

The reprojected ECEF to body attitude and Cartesian coordinates can then be readily obtained from , which leads on one hand to the reprojected NED to body attitude , equivalent to the Euler angles (yaw, pitch, and bank angles, respectively), and on the other to the geodetic coordinates (longitude, latitude, and altitude) and ECEF to NED rotation .

Let us assume for the time being that the inertially estimated body attitude () or altitude () [6] enable the navigation system to conclude that it would be preferred if the visually optimized body attitude were closer to a certain target attitude identified by the superindex , , equivalent to the target Euler angles . Section 5.3 specifies when this assumption can be considered valid, as well as various alternatives to obtain the target attitude from and . The target NED to body attitude is converted into a target ECEF to camera attitude by means of the constant body to camera rotation and the original reprojected ECEF to NED rotation , incurring in a negligible error by not considering the attitude change of the NED frame as the iteration progresses. The concatenation and multiplication operators are equivalent for rigid body rotations:

Note that the objective is not for the resulting body attitude to equal the target , but to balance both objectives (minimization of the reprojection error of the various terrain 3D points and minimization of the attitude differences with the targets) without imposing any hard constraints on the pose (position plus attitude) of the aircraft.

5.2. Prior-Based Pose Optimization

The attitude adjustment error , a function of the estimated ECEF to camera attitude for image i (), is defined in (11) as the norm of the Euclidean difference between rotation vectors corresponding to the estimated and target ECEF to camera attitudes () [1,3]. Note that refers to the capitalized logarithmic function [1,3].

Its minimization can be solved by means of an iterative Gauss-Newton gradient descent process [1,7]. Given an initial rotation vector (attitude) estimation taken from the initial pose , each iteration step l minimizes (12) and advances the estimated solution by means of (3) until the step diminution of the attitude adjustment error falls below a given threshold . Note that represents the estimated tangent space incremental ECEF to camera attitude (rotation vector) viewed in the camera frame for image i and iteration l, and represent the plus and concatenation operators, and and refer to the capitalized exponential and logarithmic functions, respectively [1,3].

Each represents the update to the camera attitude given by the rotation vector viewed in the local camera frame , which is obtained by following the process described in [1,7] (in this process the Jacobian coincides with the identity matrix because the map coincides with the rotation vector itself), and results in (14), where (15) is the right Jacobian for image i and iteration step l provided by [1,3]. These references also provide an expression for the right Jacobian inverse . Note that while and present in (11) and (12) are both positive scalars, the adjustment error that appears in (14) is an vector.

The prior-based pose adjustment algorithm attempts to obtain the ECEF to camera pose that minimizes the reprojection error discussed in Appendix C combined with the weighted attitude adjustment error . The specific weight is discussed in Section 5.3. Inspired in [10], the main goal of the optimization algorithm is to minimize the reprojection error of the different terrain 3D points while simultaneously trying to be close to the attitude and altitude targets derived from the inertial filter.

Although the rotation vector can be directly obtained from the pose [1,3], merging the two algorithms requires a dimension change in the (15) Jacobian, as indicated by (17).

The application of the iterative process described in [10] results in the following solution, which combines the contributions from the two different optimization targets:

5.3. PI Control-Inspired Pose Adjustment Activation

Section 5.1 and Section 5.2 describe the attitude adjustment and its fusion with the default reprojection error minimization pose optimization algorithm, but they do not specify the conditions under which the adjustment is activated, how the target is determined, or the obtainment of its relative weight when applying the (16) joint optimization. These parameters are determined below in three different cases: an adjustment in which only pitch is controlled, an adjustment in which both pitch and bank angles are controlled, and a complete attitude adjustment.

5.3.1. Pitch Adjustment Activation

The attitude adjustment described in (11) through (15) can be converted into a pitch only () adjustment by forcing the yaw () and bank () angle targets to coincide in each optimization i with the outputs of the reprojection only optimization. The target geodetic coordinates () also coincide with the ones resulting from the reprojection only optimization.

When activated as explained below, the new ECEF to body pose target only differs in one out of six dimensions (the pitch) from the reprojection only optimum pose , and the difference is very small as its effects are intended to accumulate over many successive images. This does not mean however that the other five components do not vary, as the joint optimization process described in (16) through (20) freely optimizes within with six degrees of freedom to minimize the joint cost function that not only considers the reprojection error, but also the resulting pitch target.

The pitch adjustment aims for the visual estimations for altitude and pitch (in this order) not to deviate in excess from their inertially estimated counterparts and . It is inspired in a proportional integral (PI) control scheme [11,12,13,14] in which the geometric altitude adjustment error can be considered as the integral of the pitch adjustment error in the sense that any difference between adjusted pitch angles (the P control) slowly accumulate over time generating differences in adjusted altitude (the I control). In this context, adjustment error is understood as the difference between the visual and inertial estimations. In addition, the adjustment also depends on the rate of climb (ROC) adjustment error (to avoid noise, this is smoothed over the last 100 images or ) , which can be considered a second P control as ROC is the time derivative of the pressure altitude.

Note that the objective is not for the visual estimations to closely track the inertial ones, but only to avoid excessive deviations, so there exist lower thresholds , , and below which the adjustments are not activated. These thresholds are arbitrary but have been set taking into account the inertial navigation system (INS) accuracy and its sources of error, as described in [6]. If the absolute value of a certain adjustment error (difference between the visual and estimated states) is above its threshold, the visual inertial system can conclude with a high degree of confidence that the adjustment procedure can be applied; if below the threshold, the adjustment should not be employed as there is a significant risk that the true visual error (difference between the visual and actual states) may have the opposite sign, in which case the adjustment would be counterproductive.

As an example, let us consider a case in which the visual altitude is significantly higher than the inertial one , resulting in ; in this case the system concludes that the aircraft is “high” and applies a negative pitch adjustment to slowly decrease the body pitch visual estimation over many images, with these accumulating over time into a lower altitude that what would be the case if no adjustment were applied. On the other hand, if the absolute value of the adjustment error is below the threshold (), the adjustment should not be applied as there exists a significant risk that the aircraft is in fact “low” instead of “high” (when compared with the true altitude , not the the inertial one ), and a negative pitch adjustment would only exacerbate the situation. A similar reasoning applies for the adjustment pitch error, in which the visual inertial system reacts or not to correct perceived “nose-up” or “nose-down” visual estimations. The applied thresholds are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pitch and bank adjustment settings.

The pitch target to be applied for each image is given by (22), where the obtainment of the pitch adjustment is explained below based on its three components (25):

- The pitch adjustment due to altitude, , linearly varies between zero when the adjustment error is below the threshold to when the error is twice the threshold, as shown in (26). The adjustment is bounded at this value to avoid destabilizing SVO with pose adjustments that differ too much from their reprojection only optimum (9).

- The pitch adjustment due to pitch, , works similarly but employing instead of and instead of , while also relying on the same limit . In addition, is set to zero if its sign differs from that of , and reduced so the combined effect of both targets does not exceed the limit ().

- The pitch adjustment due to rate of climb, , also follows a similar scheme but employing instead of , instead of , and instead of . Additionally, it is multiplied by the ratio between and to limit its effects when the altitude estimated error is small. This adjustment can act in both directions, imposing bigger pitch adjustments if the altitude error is increasing or lower one if it is already diminishing.

If activated, the weight value required for the (16) joint optimization is determined by imposing that the weighted attitude error coincides with the reprojection error when evaluated before the first iteration, this is, it assigns the same weight to the two active components of the joint cost function (16).

5.3.2. Pitch and Bank Adjustment Activation

The previous scheme can be modified to also make use of the inertially estimated body bank angle within the framework established by the (11) through (15) attitude adjustment optimization:

Although the new body pose target only differs in two out of six dimensions (pitch and bank) from the optimum pose obtained by minimizing the reprojection error exclusively, all six degrees of freedom are allowed to vary when minimizing the joint cost function.

The determination of the pitch adjustment does not vary with respect to (25), and that of the bank adjustment relies on a linear adjustment between two values similar to any of the three components of (25), but relying on the bank angle adjustment error , as well as a threshold and maximum adjustment whose values are provided in Table 2. Note that the value of the threshold coincides with that of as the INS accuracy for both pitch and roll is similar according to [6].

5.3.3. Attitude Adjustment Activation

The use of the inertially estimated yaw angle is not recommended as the visual estimation (without any inertial inputs) is, in general, more accurate than its inertial counterpart , as discussed in Section 7. This can be traced on one side to the bigger influence that a yaw change has on the resulting optical flow when compared with those caused by pitch and bank changes, which makes the body yaw angle easier to track by visual systems when compared to the pitch and bank angles, and on the other to the inertial system relying on the gravity pointing down to control pitch and bank adjustments versus the less robust dependence on the Earth magnetic field and associated magnetometer readings used to estimate the aircraft heading [6].

For this reason, the attitude adjustment process described next has not been implemented, although it is included here as a suggestion for other applications in which the objective may be to adjust the vehicle attitude as a whole. The process relies on the inertially estimated attitude and the initial estimation provided by the reprojection only pose optimization process. Its difference is given by , where represents the minus operator and the superindex “Bi” indicates that it is viewed in the pose optimized body frame. This perturbation can be decoupled into a rotating direction and an angular displacement [1,3], resulting in .

Let us now consider that the visual inertial system decides to set an attitude target that differs by from its reprojection only solution , but rotating about the axis that leads towards its inertial estimation . The target attitude can then be obtained by Spherical Linear Interpolation (SLERP) [1,2], where is the ratio between the target rotation and the attitude error or estimated angular displacement:

5.4. Additional Modifications to SVO

In addition to the PI-inspired introduction of priors into the pose optimization phase, the availability of inertial estimations enable other minor modifications to the original SVO pipeline described in Appendix C. These include the addition of the current features to the structure optimization phase (so the pose adjustments introduced by the prior based pose optimization are not reverted), the replacement of the sparse image alignment phase by an inertial estimation of the input to the pose optimization process, and the use of the GNSS-based inertial distance estimations to obtain more accurate height and path angle values for the SVO initialization.

6. Testing: High-Fidelity Simulation and Scenarios

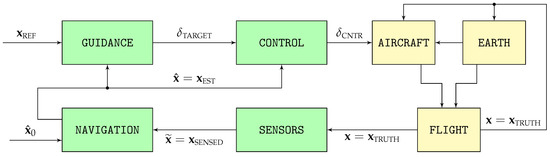

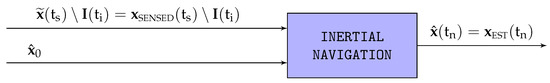

To evaluate the performance of the proposed visual navigation algorithms, this article relies on Monte Carlo simulations consisting of 100 runs each of two different scenarios based on the high fidelity stochastic flight simulator graphically depicted in Figure 4. Described in detail in [15] and with its open source C++ implementation available in [16], the simulator models the flight in varying weather and turbulent conditions of a fixed wing piston engine autonomous UAV.

Figure 4.

Components of the high-fidelity simulation.

The simulator consists of two distinct processes. The first, represented by the yellow blocks on the right of Figure 4, models the physics of flight and the interaction between the aircraft and its surroundings that results in the real aircraft trajectory ; the second, represented by the green blocks on the left, contains the aircraft systems in charge of ensuring that the resulting trajectory adheres as much as possible to the mission objectives. It includes the different sensors whose output comprise the sensed trajectory , the navigation system in charge of filtering it to obtain the estimated trajectory , the guidance system that converts the reference objectives into the control targets , and the control system that adjusts the position of the throttle and aerodynamic control surfaces so the estimated trajectory is as close as possible to the reference objectives . Table 3 provides the working frequencies employed for the different trajectories shown in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Table 3.

Working frequencies of the different systems and trajectory representations.

Figure 5.

INS flow diagram.

Figure 6.

VNS flow diagram.

Figure 7.

IA-VNS flow diagram.

All components of the flight simulator have been modeled with as few simplifications as possible to increase the realism of the results, as explained in [15,17]. With the exception of the aircraft performances and its control system, which are deterministic, all other simulator components are treated as stochastic and hence vary from one execution to the next, enhancing the significance of the Monte Carlo simulation results.

6.1. Camera

The flight simulator has the capability, when provided with the camera pose (the camera is positioned facing down and rigidly attached to the aircraft structure) with respect to the Earth at equally spaced time intervals, of generating images that resemble the view of the Earth surface that the camera would record if located at that particular pose. To do so, it relies on the Earth Viewer library, a modification to osgEarth [18] (which, in turn, relies on OpenSceneGraph [19]) capable of generating realistic Earth images as long as the camera height over the terrain is significantly higher than the vertical relief present in the image. A more detailed explanation of the image generation process is provided in [17].

It is assumed that the shutter speed is sufficiently high that all images are equally sharp, and that the image generation process is instantaneous. In addition, the camera ISO setting remains constant during the flight, and all generated images are noise free. The simulation also assumes that the visible spectrum radiation reaching all patches of the Earth surface remains constant, and the terrain is considered Lambertian [20], so its appearance at any given time does not vary with the viewing direction. The combined use of these assumptions implies that a given terrain object is represented with the same luminosity in all images, even as its relative pose (position and attitude) with respect to the camera varies. Geometrically, the simulation adopts a perspective projection or pinhole camera model [20], which, in addition, is perfectly calibrated and hence shows no distortion. The camera has a focal length of and a sensor with 768 by 1024 pixels.

6.2. Scenarios

Most visual inertial odometry (VIO) packages discussed in Appendix B include in their release articles an evaluation when applied to the EuRoC Micro Air Vehicle (MAV) datasets [21], and so do independent articles, such as [22]. These datasets contain perfectly synchronized stereo images, Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) measurements, and ground truth readings obtained with a laser, for 11 different indoor trajectories flown with a MAV, each with a duration in the order of two minutes and a total distance in the order of . This fact by itself indicates that the target application of exiting VIO implementations differs significantly from the main focus of this article, which is the long term flight of a fixed wing UAV in GNSS-Denied conditions, as there may exist accumulating errors that are completely non discernible after such short periods of time, but that grow non-linearly and have the capability of inducing significant pose errors when the aircraft remains aloft for long periods of time.

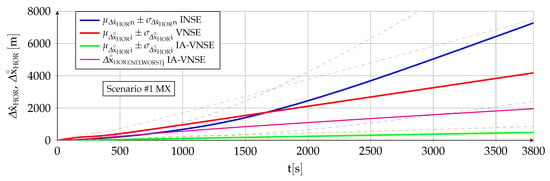

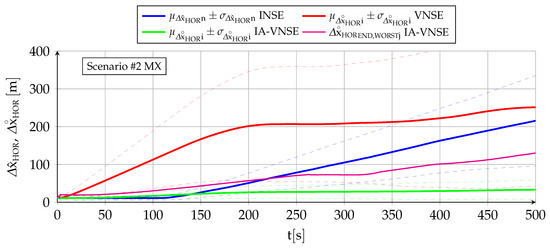

The algorithms introduced in this article are hence tested through simulation under two different scenarios designed to analyze the consequences of losing the GNSS signals for long periods of time. Although a short summary is included below, detailed descriptions of the mission, weather, and wind field employed in each scenario can be found in [15]. Most parameters comprising the scenario are defined stochastically, resulting in different values for every execution. Note that all results shown in Section 7 and Section 8 are based on Monte Carlo simulations comprising 100 runs of each scenario, testing the sensitivity of the proposed navigation algorithms to a wide variety of values in the parameters.

- Scenario #1 has been defined with the objective of adequately representing the challenges faced by an autonomous fixed wing UAV that suddenly cannot rely on GNSS and hence changes course to reach a predefined recovery location situated at approximately one hour of flight time. In the process, in addition to executing an altitude and airspeed adjustment, the autonomous aircraft faces significant weather and wind field changes that make its GNSS-Denied navigation even more challenging.With respect to the mission, the stochastic parameters include the initial airspeed, pressure altitude, and bearing (), their final values (), and the time at which each of the three maneuvers is initiated (turns are executed with a bank angle of , altitude changes employ an aerodynamic path angle of , and airspeed modifications are automatically executed by the control system as set-point changes). The scenario lasts for , while the GNSS signals are lost at .The wind field is also defined stochastically, as its two parameters (speed and bearing) are constant both at the beginning () and conclusion () of the scenario, with a linear transition in between. The specific times at which the wind change starts and concludes also vary stochastically among the different simulation runs. As described in [15], the turbulence remains strong throughout the whole scenario, but its specific values also vary stochastically from one execution to the next.A similar linear transition occurs with the temperature and pressure offsets that define the atmospheric properties [23], as they are constant both at the start () and end () of the flight. In contrast with the wind field, the specific times at which the two transitions start and conclude are not only stochastic but also different from each other.

- Scenario #2 represents the challenges involved in continuing with the original mission upon the loss of the GNSS signals, executing a series of continuous turn maneuvers over a relatively short period of time with no atmospheric or wind variations. As in scenario , the GNSS signals are lost at , but the scenario duration is shorter (). The initial airspeed and pressure altitude () are defined stochastically and do not change throughout the whole scenario; the bearing however changes a total of eight times between its initial and final values, with all intermediate bearing values, as well as the time for each turn varying stochastically from one execution to the next. Although the same turbulence is employed as in scenario , the wind and atmospheric parameters () remain constant throughout scenario .

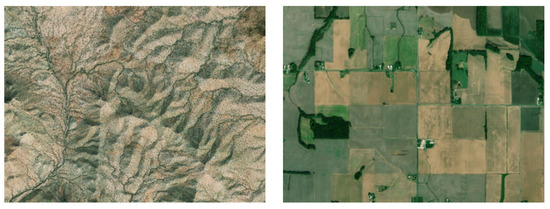

8. Influence of Terrain Type

The type of terrain overflown by the aircraft has a significant influence on the performance of the visual navigation algorithms, which can not operate unless the feature detector is capable of periodically locating features in the various keyframes, and which also requires the depth filter to correctly estimate the 3D terrain coordinates of each feature (Appendix C). The terrain texture (or lack of) and its elevation relief are, hence, the two most important characteristics in this regard. To evaluate its influence, each of the scenario #1 100 Monte Carlo runs are executed flying above four different zones or types of terrain, intended to represent a wide array of conditions; images representative of each zone as viewed by the onboard camera are included below. The use of terrains that differ in both their texture and vertical relief is intended to provide a more complete validation of the proposed algorithms. Note that the only variation among the different simulations is the terrain type, as all other parameters defining each scenario (mission, aircraft, sensors, weather, wind, turbulence, geophysics, initial estimations) are exactly the same for all simulation runs.

- The “desert” (DS) zone (left image within Figure 15) is located in the Sonoran desert of southern Arizona (USA) and northern Mexico. It is characterized by a combination of bajadas (broad slopes of debris) and isolated very steep mountain ranges. There is virtually no human infrastructure or flat terrain, as the bajadas have sustained slopes of up to . The altitude of the bajadas ranges from to above MSL, and the mountains reach up to above the surrounding terrain. Texture is abundant because of the cacti and the vegetation along the dry creeks.

Figure 15. Typical “desert” (DS) and “farm” (FM) terrain views.

Figure 15. Typical “desert” (DS) and “farm” (FM) terrain views. - The “farm” (FM) zone (right image within Figure 15) is located in the fertile farmland of southeastern Illinois and southwestern Indiana (USA). A significant percentage of the terrain is made of regular plots of farmland, but there also exists some woodland, farm houses, rivers, lots of little towns, and roads. It is mostly flat with an altitude above MSL between and , and altitude changes are mostly restricted to the few forested areas. Texture is non-existent in the farmlands, where extracting features is often impossible.

- The “forest” (FR) zone (left image within Figure 16) is located in the deciduous forestlands of Vermont and New Hampshire (USA). The terrain is made up of forests and woodland, with some clearcuts, small towns, and roads. There are virtually no flat areas, as the land is made up by hills and small to medium size mountains that are never very steep. The valleys range from to above MSL, while the tops of the mountains reach to . Features are plentiful in the woodlands.

Figure 16. Typical “forest” (FR) and “mix” (MX) terrain views.

Figure 16. Typical “forest” (FR) and “mix” (MX) terrain views. - The “mix” (MX) zone (right image within Figure 16) is located in northern Mississippi and extreme southwestern Tennessee (USA). Approximately half of the land consists of woodland in the hills, and the other half is made up by farmland in the valleys, with a few small towns and roads. Altitude changes are always present and the terrain is never flat, but they are smaller than in the DS and FR zones, with the altitude oscillating between and above MSL.

The short duration and continuous maneuvering of scenario #2 enables the use of two additional terrain types. These two zones are not employed in scenario #1 because the authors could not locate wide enough areas with a prevalence of this type of terrain (note that scenario #1 trajectories can conclude up to in any direction from its initial coordinates, but only for scenario #2).

- The “prairie” (PR) zone (left image within Figure 17) is located in the Everglades floodlands of southern Florida (USA). It consists of flat grasslands, swamps, and tree islands located a few meters above MSL, with the only human infrastructure being a few dirt roads and landing strips, but no settlements. Features may be difficult to obtain in some areas due to the lack of texture.

Figure 17. Typical “prairie” (PR) and “urban” (UR) terrain views.

Figure 17. Typical “prairie” (PR) and “urban” (UR) terrain views. - The “urban” (UR) zone (right image within Figure 17) is located in the Los Angeles metropolitan area (California, USA). It is composed by a combination of single family houses and commercial buildings separated by freeways and streets. There is some vegetation but no natural landscapes, and the terrain is flat and close to MSL.

The MX terrain zone is considered the most generic and hence employed to evaluate the visual algorithms in Section 7. Although scenario #2 also makes use of the four terrain types listed for scenario #1 (DS, FM, FR, and MX), it is worth noting that the variability of the terrain is significantly higher for scenario #1 because of the bigger land extension covered. The altitude relief, abundance or scarcity of features, land use diversity, and presence of rivers and mountains is, hence, more varied when executing a given run of scenario #1 over a certain type of terrain, than when executing the same run for scenario #2. From the point of view of the influence of the terrain on the visual navigation algorithms, scenario #1 should theoretically be more challenging than #2.

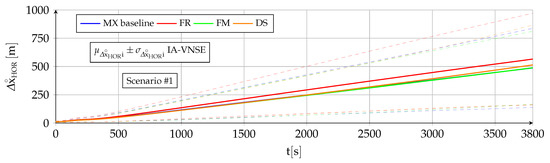

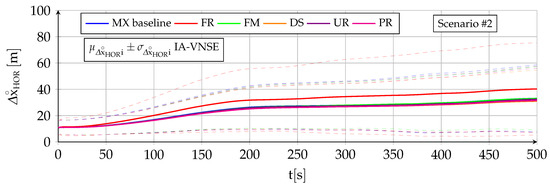

Table 7 and Figure 18 show the horizontal position IA-NVSE for scenario and all terrain types. Table 8 and Figure 19 do the same for scenario .

Table 7.

Influence of terrain type on final horizontal position IA-VNSE for scenario (100 runs). The most important metrics appear in bold.

Figure 18.

Influence of terrain type on horizontal position IA-VNSE for scenario (100 runs).

Table 8.

Influence of terrain type on final horizontal position IA-VNSE for scenario (100 runs). The most important metrics appear in bold.

Figure 19.

Influence of terrain type on horizontal position IA-VNSE for scenario (100 runs).

The influence of the terrain type on the horizontal position IA-VNSE is very small, with slim differences among the various evaluated terrains. The only terrain type that clearly deviates from the others is FR, with slight but consistently worse horizontal position estimations for both scenarios. This behavior stands out as the abundant texture and continuous smooth vertical relief of the FR terrain is a priori beneficial for the visual algorithms.

Although beneficial for the SVO pipeline, the more pronounced vertical relief of the FR terrain type breaches the flat terrain assumption of the initial homography (Appendix C), hampering its accuracy, and, hence, results in less precise initial estimations, including that of the scale. The IA-VNS has no means to compensate the initial scale errors, which remain approximately equal (percentage wise) for the full duration of both scenarios.

A similar but opposite reasoning is applicable to the FM type and in a lesser degree to the UR and PR types. Although a flat terrain in which all terrain features are located at a similar altitude is detrimental to the overall accuracy of SVO, and results in slightly worse body attitude and vertical position estimations, it is beneficial for the homography initialization and the scale determination, resulting in consistently more accurate horizontal position estimations.

9. Summary of Results

This article proposes a Semi-Direct Visual Odometry (SVO)-based Inertially Assisted Visual Navigation System (IA-VNS) installed onboard a fixed wing autonomous UAV that takes advantage of the GNSS-Denied estimations provided by an Inertial Navigation System (INS) to assist the visual pose optimization algorithms. The method is inspired in a Proportional Integral (PI) control loop, in which the inertial attitude and altitude outputs act as targets to ensure that the visual estimations do not deviate in excess from their inertial counterparts, resulting in major improvements when estimating the aircraft horizontal position without the use of GNSS signals. The results obtained when applying the proposed algorithms to high fidelity Monte Carlo simulations of two scenarios representative of the challenges of GNSS-Denied navigation indicate the following:

- The body attitude estimation shows significant quantitative improvements over a standalone Visual Navigation System (VNS) in both pitch and bank angle estimations, with no negative influence on the yaw angle estimations. A small amount of drift with time is present, and can not be fully eliminated. Body pitch and bank angle estimations do not deviate in excess from their INS counterparts, while the body yaw angle visual estimation is significantly more accurate than that obtained by the INS.

- The vertical position estimation shows major improvements over that of a standalone VNS, not only quantitatively but also qualitatively, as drift is fully eliminated. The visual estimation does not deviate in excess from the inertial one, which is bounded by atmospheric physics.

- The horizontal position estimation, whose improvement is the main objective of the proposed algorithm, shows major gains when compared to either the standalone VNS or the INS, although drift is still present.

In addition, although the terrain texture (or lack of) and its elevation relief are key factors for the visual odometry algorithms, their influence on the aircraft pose estimation results are slim, and the accuracy of the IA-VNS does not vary significantly among the various evaluated terrain types.

10. Conclusions

The proposed inertially assisted VNS (IA-VNS), which in addition to the images taken by an onboard camera also relies on the outputs of an INS specifically designed for the challenges faced by autonomous fixed wing aircraft that encounter GNSS-Denied conditions, possesses significant advantages in both accuracy and resilience when compared with a standalone VNS, the most important of which is a major reduction in its horizontal position drift independently of the terrain type overflown by the aircraft. The proposed IA-VNS can significantly increase the possibilities of the aircraft safely reaching the vicinity of the intended recovery location upon the loss of GNSS signals, from where it can be landed by remote control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.; methodology, E.G.; software, E.G.; validation, E.G.; formal analysis, E.G.; investigation, E.G.; resources, E.G.; data curation, E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.; writing—review and editing, A.B.; visualization, E.G.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has received funding from RoboCity2030-DIH-CM, Madrid Robotics Digital Innovation Hub, S2018/NMT-4331, funded by R&D Activity Programs in the Madrid Community and co-financed by the EU Structural Funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

An open source C++ implementation of the described algorithms can be found at [16].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BRIEF | Binary Robust Independent Elementary Features |

| DS | DeSert terrain type |

| DSO | Direct Sparse Odometry |

| ECEF | Earth Centered Earth Fixed |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| FAST | Features from Accelerated Segment Test |

| FM | FarM terrain type |

| FR | FoRest terrain type |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| IA-VNS | Inertially Assisted VNS |

| IA-VNSE | Inertially Assisted Visual Navigation System Error |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| INSE | Inertial Navigation System Error |

| iSAM | Incremental Smoothing And Mapping |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LSD | Large Scale Direct |

| MAV | Micro Air Vehicle |

| MSCKF | Multi State Constraint Kalman Filter |

| MSF | Multi-Sensor Fusion |

| MSL | Mean Sea Level |

| MX | MiX terrain type |

| NED | North East Down |

| NSE | Navigation System Error |

| OKVIS | Open Keyframe Visual Inertial SLAM |

| ORB | Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF |

| PI | Proportional Integral |

| PR | Praire terrain type |

| RANSAC | Random SAmple Consensus |

| ROC | Rate Of Climb |

| ROVIO | Robust Visual Inertial Odometry |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization And Mapping |

| SLERP | Spherical linear interpolation |

| SVO | Semi direct Visual Odometry |

| SWaP | Size, Weight, and Power |

| TAS | True Air Speed |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UR | Urban terrain type |

| USA | United States of America |

| VINS | Visual Inertial Navigation System |

| VIO | Visual Inertial Odometry |

| VNS | Visual Navigation System |

| VNSE | Visual Navigation System Error |

| VO | Visual Odometry |

| WGS84 | World Geodetic System 1984 |

Appendix A. Optical Flow

Consider a pinhole camera [24] (one that adopts an ideal perspective projection) such as that depicted in Figure A1. The image frame is a two-dimensional Cartesian reference frame whose axes are parallel to those of the camera frame (), and whose origin is located on the focal plane displaced a distance from the principal point so the coordinates and of any point in the image domain are always positive. The perspective projection map that converts points viewed in into is hence the following:

Consider also that the camera is moving with respect to the Earth while maintaining within its field of view a given point fixed to the Earth surface. The composition of positions and its time derivation, considering ECEF as , the camera frame as , and a frame with its origin in the terrain point that does not move with respect to , results in the following expression when viewed in :

Note that (A6) connects the point coordinates as viewed from the camera and their time derivative with the twist of the motion of the camera with respect to the Earth viewed in the or local frame, which is composed by its linear and angular velocities and [3].

Figure A1.

Frontal pinhole camera model.

The homogeneous camera coordinates are defined as the ratio between the camera coordinates and its third coordinate or depth , and represent an alternative view to of how the point is projected in the image. Its time derivative is hence:

Substituting both and within (A7) into (A8), rearranging terms, and considering the (A1, ) relationship between the image and the homogeneous camera coordinates, leads to the following expression for the optical flow [25] or variation of the point image coordinates:

Considering that the twist is the time derivative of the transform vector [3], the optical flow is defined as the derivative of the local frame ideal perspective projection of a point fixed to the spatial frame with respect to the element caused by a perturbation in its local tangent space:

Less formally, the optical flow Jacobian represents how the projection of a fixed point moves within the image as the camera pose varies. Note that the Jacobian only depends on the point camera (local) coordinates and the camera focal length, and that as all terms multiplying the linear twist component are divided by the image depth , the effect on the image of a bigger linear velocity can not be distinguished from that of a smaller depth.

Appendix C. Semi-Direct Visual Odometry

Semi-Direct Visual Odometry (SVO) [4,5] is a publicly available advanced combination of feature-based and direct VO techniques primarily intended towards the navigation of land robots, road vehicles, and multi-rotors, holding various advantages in terms of accuracy and speed over traditional VO algorithms. By combining the best characteristics of both approaches while avoiding their weaknesses, it obtains high accuracy and robustness with a limited computational budget. This section provides a short summary of the SVO pipeline, although the interested reader should refer to [4,5] for a more detailed description; the pose optimization phase is however described in depth (Section 4), as it is the focus of the proposed modifications described in Section 5.

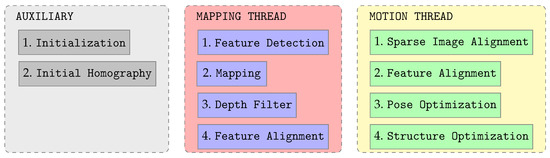

SVO initializes like a feature-based monocular method, requiring the height over the terrain to provide the scale (initialization), and using feature matching and RANSAC [75] based triangulation (initial homography) to obtain a first estimation of the terrain 3D position of the identified features. After initialization, the SVO pipeline for each new image can be divided into two different threads: the mapping thread, which generates terrain 3D points, and the motion thread, which estimates the camera motion (Figure A2).

Once initialized, the expensive feature detection process (mapping thread) that obtains the features does not occur in every frame but only once a sufficiently large motion has occurred since the last feature extraction. When processing each new frame, SVO initially behaves like a direct method, discarding the feature descriptors and skipping the matching process, and employing the luminosity values of small patches centered around every feature to (i) obtain a rough estimation of the camera pose (sparse image alignment, motion thread), followed by (ii) a relaxation of the epipolar restrictions to achieve a better estimation of the different features sub-pixel location in the new frame (feature alignment, motion thread), which introduces a reprojection residual that is exploited in the next steps. At this point, SVO once again behaves like a feature-based method, refining (iii) the camera pose (pose optimization, motion thread) and (iv) the terrain coordinates of the 3D points associated to each feature (structure optimization, motion thread) based on non-linear minimization of the reprojection error.

Figure A2.

SVO threads and processes.

In this way, SVO is capable of obtaining the accuracy of direct methods at a very high computational speed, due to only extracting features in selected frames, avoiding (for the most part) robust algorithms when tracking features, and only reconstructing the structure sparsely. The accuracy of SVO improves if the pixel displacement between consecutive frames is reduced (high frame rate), which is generally possible as the computational expenses associated to each frame are low.

None of the motion thread four non-linear optimization processes listed above makes use of RANSAC, and pose optimization is the only one that employs a robust M-estimator [8,9] instead of the traditional mean or squared error estimator. This has profound benefits in terms of computational speed but leaves the whole process vulnerable to the presence of outliers in either the features terrain or image positions. To prevent this, once a feature is detected in a given frame (note that the extraction process obtains pixel coordinates, not terrain 3D ones), it is immediately assigned with a depth filter (mapping thread) initialized with a large enough uncertainty around the average depth in the scene; in each subsequent frame, the feature 3D position is estimated by reprojection and the depth filter uncertainty reduced. Once the feature depth filter has converged, the detected feature and its associated 3D point become a map candidate, which it is not yet employed in the motion thread optimizations required to estimate the camera pose. The feature alignment process is however applied in the background to the map candidates, and it is only after several successful reprojections that a candidate is upgraded to a map 3D point and, hence, allowed to influence the motion result. This two step verification process that requires depth filter convergence and various successful reprojections before a 3D point is employed in the (mostly) non-robust optimizations is key to prevent outliers from contaminating the solution and reducing its accuracy.

References

- Gallo, E. The SO(3) and SE(3) Lie Algebras of Rigid Body Rotations and Motions and their Application to Discrete Integration, Gradient Descent Optimization, and State Estimation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12572v1. [Google Scholar]

- Sola, J. Quaternion Kinematics for the Error-State Kalman Filter. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.02508v1. [Google Scholar]

- Sola, J.; Deray, J.; Atchuthan, D. A Micro Lie Theory for State Estimation in Robotics. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.01537v9. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, C.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Fast Semi-Direct Monocular Visual Odometry. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gassner, M.; Werlberger, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Semidirect Visual Odometry for Monocular and Multicamera Systems. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 33, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, E.; Barrientos, A. Reduction of GNSS-Denied Inertial Navigation Errors for Fixed Wing Autonomous Unmanned Air Vehicles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Matthews, I. Lucas-Kanade 20 Years On: A Unifying Framework. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 56, 221–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, P.J. Robust Statistics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. Robust Regression. 2013. Available online: http://users.stat.umn.edu/~sandy/courses/8053/handouts/robust.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Baker, S.; Gross, R.; Matthews, I. Lucas-Kanade 20 Years On: A Unifying Framework: Part 4; Technical Report CMU-RI-TR-04-14; Carnegie Mellon University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, K. Modern Control Engineering, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall, 2002; Available online: https://scirp.org/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=123554 (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Skogestad, S.; Postlethwaite, I. Multivariable Feedback Control: Analysis and Design, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, B.L.; Lewis, F.L. Aircraft Control and Simulation, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, G.F.; Powell, J.D.; Workman, M. Digital Control of Dynamic Systems, 3rd ed.; Ellis-Kagle Press: Sunnyvale, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, E. Stochastic High Fidelity Simulation and Scenarios for Testing of Fixed Wing Autonomous GNSS-Denied Navigation Algorithms. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.00883v3. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, E. High Fidelity Flight Simulation for an Autonomous Low SWaP Fixed Wing UAV in GNSS-Denied Conditions. C++ Open Source Code. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/edugallogithub/gnssdenied_flight_simulation (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Gallo, E.; Barrientos, A. Customizable Stochastic High Fidelity Model of the Sensors and Camera onboard a Fixed Wing Autonomous Aircraft. Sensors 2022, 22, 5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- osgEarth. Available online: http://osgearth.org (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Open Scene Graph. Available online: http://openscenegraph.org (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Ma, Y.; Soatto, S.; Kosecka, J.; Sastry, S.S. An Invitation to 3-D Vision, From Images to Geometric Models; Imaging, Vision, and Graphics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Burri, M.; Nikolic, J.; Gohl, P.; Schneider, T.; Rehder, J.; Omari, S.; Achtelik, M.W.; Siegwart, R. The EuRoC MAV Datasets. IEEE Int. J. Robot. Res. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmerico, J.; Scaramuzza, D. A Benchmark Comparison of Monocular Visual-Inertial Odometry Algorithms for Flying Robots. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 2502–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, E. Quasi Static Atmospheric Model for Aircraft Trajectory Prediction and Flight Simulation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.10744v1. [Google Scholar]

- Hartley, R.; Zisserman, A. Multiple View Geometry in Computer Vision, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heeger, D.J. Notes on Motion Estimation. 1998. Available online: https://www.cns.nyu.edu/csh/csh04/Articles/carandinifix.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Hassanalian, M.; Abdelkefi, A. Classifications, Applications, and Design Challenges of Drones: A Review. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 91, 99–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijjahalli, S.; Sabatini, R.; Gardi, A. Advances in Intelligent and Autonomous Navigation Systems for Small UAS. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2020, 115, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.A. Aided Navigation, GPS with High Rate Sensors; Electronic Engineering Series; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, P.D. Principles of GNSS, Inertial, and Multisensor Integrated Navigation Systems; GNSS Technology and Application Series; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield, A.B. Fundamentals of High Accuracy Inertial Navigation; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Progress in Astronautics and Aeronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 1997; Volume 174. [Google Scholar]

- Elbanhawi, M.; Mohamed, A.; Clothier, R.; Palmer, J.; Simic, M.; Watkins, S. Enabling Technologies for Autonomous MAV Operations. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 91, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, R.; Moore, T.; Ramasamy, S. Global Navigation Satellite Systems Performance Analysis and Augmentation Strategies in Aviation. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2017, 95, 45–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippitt, C.; Schultz, A.; Procino, W. Vehicle Navigation: Autonomy Through GPS-Enabled and GPS-Denied Environments; State of the Art Report DSIAC-2020-1328; Defense Systems Information Analysis Center: Belcamp, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gyagenda, N.; Hatilima, J.V.; Roth, H.; Zhmud, V. A Review of GNSS Independent UAV Navigation Techniques. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2022, 152, 104069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.; Ramasamy, S.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R. UAV Navigation using Signals of Opportunity in Urban Environments: A Review. Energy Procedia 2017, 110, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluccia, A.; Ricciato, F.; Ricci, G. Positioning Based on Signals of Opportunity. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2014, 18, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.T.; Abdelkhalik, O.; Zekavat, S.A. A Weighted Measurement Fusion Kalman Filter Implementation for UAV Navigation. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2013, 28, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, A.; Akhloufi, M.A. A Review on Absolute Visual Localization for UAV. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 135, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goforth, H.; Lucey, S. GPS-Denied UAV Localization using Pre Existing Satellite Imagery. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, N. Geolocation of an Aircraft using Image Registration Coupling Modes for Autonomous Navigation. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.02875v1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. Augmented UAS Navigation in GPS Denied Terrain Environments using Synthetic Vision. Ph.D. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzza, D.; Fraundorfer, F. Visual Odometry Part 1: The First 30 Years and Fundamentals. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2011, 18, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraundorfer, F.; Scaramuzza, D. Visual Odometry Part 2: Matching, Robustness, Optimization, and Applications. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzza, D. Tutorial on Visual Odometry; Robotics & Perception Group, University of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramuzza, D. Visual Odometry and SLAM: Past, Present, and the Robust Perception Age; Robotics & Perception Group, University of Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cadena, C.; Carlone, L.; Carrillo, H.; Latif, Y.; Scaramuzza, D.; Neira, J.; Reid, I.; Leonard, J.J. Past, Present, and Future of Simultaneous Localization and Mapping: Towards the Robust Perception Age. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 1309–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Koltun, V.; Cremers, D. Direct Sparse Odometry. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 40, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, J.; Schops, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-SLAM: Large Scale Direct Monocular SLAM. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; pp. 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM: A Versatile and Accurate Monocular SLAM System. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2015, 31, 1147–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Tardos, J.D. ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R. Real-Time Accurate Visual SLAM with Place Recognition. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramuzza, D.; Zhang, Z. Visual-Inertial Odometry of Aerial Robots. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.03289v2. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G. Visual-Inertial Navigation: A Concise Review. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.02650v1. [Google Scholar]

- von Stumberg, L.; Usenko, V.; Cremers, D. Chapter 7—A Review and Quantitative Evaluation of Direct Visual Inertial Odometry. In Multimodal Scene Understanding; Yang, M.Y., Rosenhahn, B., Murino, V., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, X.; Du, M.; Li, X. Computer Vision Algorithms and Hardware Implementations: A Survey. Integr. VLSI J. 2019, 69, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaff, A.; Martin, D.; Garcia, F.; de la Escalera, A.; Maria, J. Survey of Computer Vision Algorithms and Applications for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 92, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourikis, A.I.; Roumeliotis, S.I. A Multi-State Constraint Kalman Filter for Vision-aided Inertial Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Rome, Italy, 10–14 April 2007; pp. 3565–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, S.; Furgale, P.; Rabaud, V.; Chli, M.; Konolige, K.; Siegwart, R. Keyframe Based Visual Inertial SLAM Using Nonlinear Optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics: Robotics: Science and Systems IX, Berlin, Germany, 24–28 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leutenegger, S.; Lynen, S.; Bosse, M.; Siegwart, R.; Furgale, P. Keyframe Based Visual Inertial SLAM Using Nonlinear Optimization. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2015, 34, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloesch, M.; Omari, S.; Hutter, M.; Siegwart, R. Robust Visual Inertial Odometry Using a Direct EKF Based Approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Li, P.; Shen, S. VINS-Mono: A Robust and Versatile Monocular Visual Inertial State Estimator. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2018, 34, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynen, S.; Achtelik, M.W.; Weiss, S.; Chli, M.; Siegwart, R. A Robust and Modular Multi Sensor Fusion Approach Applied to MAV Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 3923–3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faessler, M.; Fontana, F.; Forster, C.; Mueggler, E.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. Autonomous, Vision Based Flight and Live Dense 3D Mapping with a Quadrotor Micro Aerial Vehicle. J. Field Robot. 2015, 33, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Carlone, L.; Dellaert, F.; Scaramuzza, D. On Manifold Pre Integration for Real Time Visual Inertial Odometry. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2017, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaess, M.; Johannsson, H.; Roberts, R.; Ila, V.; Leonard, J.; Dellaert, F. iSAM2: Incremental Smoothing and Mapping Using the Bayes Tree. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2012, 31, 216–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur-Artal, R.; Montiel, J.M.M. Visual Inertial Monocular SLAM with Map Reuse. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.; Wang, S.; Wen, H.; Markham, A.; Trigoni, N. VINet: Visual-Inertial Odometry as a Sequence-to-Sequence Learning Problem. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2017. Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/11215 (accessed on 10 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.K.; Wu, K.; Hesch, J.A.; Nerurkar, E.D.; Roumeliotis, S.I. A Comparative Analysis of Tightly Coupled Monocular, Binocular, and Stereo VINS. In Proceedings of the EEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017; pp. 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Nuske, S.; Scherer, S. A Multi Sensor Fusion MAV State Estimation from Long Range Stereo, IMU, GPS, and Barometric Sensors. Sensors 2017, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solin, A.; Cortes, S.; Rahtu, E.; Kannala, J. PIVO: Probabilistic Inertial Visual Odometry for Occlusion Robust Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 12–15 March 2018; pp. 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, S.; Quenzel, J.; Krombach, N.; Behnke, S. Efficient Multi Camera Visual Inertial SLAM for Micro Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 9–14 October 2016; pp. 1616–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckenhoff, K.; Geneva, P.; Huang, G. Direct Visual Inertial Navigation with Analytical Preintegration. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Singapore, 29 May 2017–3 June 2017; pp. 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasdat, H.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Davison, A.J. Real Time Monocular SLAM: Why Filter? In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 2657–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. RANSAC Sample Consensus: A Paradigm for Model Fitting with Applications to Image Analysis and Automated Cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).