Abstract

Isoprene (C5H8), the most abundant biogenic volatile organic compound (400–600 Tg C yr−1), exerts complex NOx-dependent influence on tropospheric ozone, yet its representation remains absent in many climate models. This study aims to quantify isoprene’s impact on tropospheric chemical composition using the Russian Earth system model INM-CM6.0 with newly implemented isoprene oxidation chemistry. Two 12-year experiments (2008–2019) were conducted: a control run without isoprene and an experiment with the Mainz Isoprene Mechanism (MIM1: 44 reactions, 16 species). Results reveal a NOx-dependent two-layer vertical structure. In the tropical surface layer (0–5 km, 20° S–20° N), ozone decreases by 10–15 ppb through radical termination under low-NOx (<100 ppt), with 15–30% OH reduction and 30–60% CO increase. In the middle troposphere (8–12 km), ozone increases by 10–15 ppb through thermal decomposition of vertically transported PAN and MPAN. In subtropics (20–35°) with elevated NOx (>500 ppt), isoprene stimulates ozone formation at all altitudes (+3–12 ppb). Oxidation product distributions establish a spatial hierarchy: local (ISON, NALD: 0–5 km), regional (MPAN: to 8 km), and global (PAN: reaching high latitudes at 8–12 km). Comparison with CAMS, MERRA-2, and ERA5 reanalyses shows substantial improvement: tropical CO discrepancies decrease from 20–30% to 10–15%, OH by factors of 2–3, and ozone overestimation from 30–40% to 10–15%. These findings demonstrate that explicit isoprene chemistry is essential for accurate tropospheric composition simulation, particularly given the projected 21–57% emission increases by 2100 under climate warming.

1. Introduction

Tropospheric ozone (O3) plays a dual role in atmospheric processes: as a toxic air pollutant affecting human health and vegetation, it simultaneously acts as an important short-lived greenhouse gas with radiative forcing of approximately 0.4 W m−2 [1,2]. Unlike stratospheric ozone, which forms exclusively through photolysis of molecular oxygen, tropospheric O3 results from complex photochemical oxidation of carbon monoxide (CO) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the presence of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and hydroxyl radicals (OH) [3]. Understanding tropospheric ozone formation processes is critically important both for developing air quality control strategies and for climate projections, especially under changing anthropogenic and biogenic emissions.

Among volatile organic compounds, isoprene (C5H8, 2-methyl-1,3-butadiene) occupies a unique position. It is the most abundant biogenic VOC with global emissions of 400–600 Tg C yr−1, comparable to methane emissions and representing approximately half of all biogenic organic compound emissions [4,5]. While other biogenic VOCs—notably monoterpenes (α-pinene, β-pinene, limonene) and sesquiterpenes—contribute an additional ~100–150 Tg C yr−1 globally [4], and anthropogenic VOCs provide comparable amounts in polluted regions, isoprene dominates global biogenic emissions and exhibits the highest reactivity toward OH. Isoprene is emitted predominantly by deciduous trees in tropical and subtropical regions, with emissions strongly dependent on temperature and light intensity [6].

Beyond temperature and light, isoprene emissions and VOC-O3 interactions are modulated by multiple climatic stressors. Recent evidence demonstrates that compound climate extremes—combinations of heat, drought, and elevated ozone exposure—can significantly alter biogenic emission rates and atmospheric oxidation pathways [7]. Moreover, vegetation physiological responses to environmental stress modify VOC biosynthesis and emission patterns [8], while land-use changes fundamentally reshape the spatial distribution of biogenic emissions and their consequent impacts on tropospheric ozone formation [9]. These complex climate-vegetation-chemistry feedbacks introduce additional uncertainties into future biogenic emission projections, emphasizing the necessity of integrated Earth system models that couple dynamic vegetation responses with explicit atmospheric chemistry.

The high reactivity of isoprene toward OH (lifetime approximately 1–2 h) [10] combined with the magnitude of its emissions makes isoprene oxidation one of the central processes in tropospheric chemistry. Moreover, projected climate warming may increase biogenic isoprene emissions by 21–57% by the end of the 21st century [11,12], amplifying the importance of understanding its role in atmospheric processes. The influence of isoprene on tropospheric ozone formation is complex and, at first glance, contradictory, being determined by the atmospheric nitrogen oxide regime. Pioneering studies from the late 1980s [13,14] demonstrated that isoprene can both promote and suppress ozone formation depending on local NOx concentrations. Additionally, isoprene chemistry uniquely produces substantial quantities of peroxyacetyl nitrate (PAN) and methacryloyl peroxynitrate (MPAN)—long-lived nitrogen reservoir species that enable intercontinental NOx transport making isoprene representation a priority for climate models seeking to simulate tropospheric composition accurately.

Under low-NOx conditions (<100 ppt), typical of remote tropical forests in Amazonia, equatorial Africa, and Southeast Asia, isoprene oxidation leads to reduced ozone and OH concentrations through radical termination reactions. Peroxy radicals formed during isoprene oxidation (ISO2, MACRO2) react preferentially with hydroperoxy radicals (HO2), forming stable hydroperoxides without producing NO2—the key precursor for photochemical ozone [15,16]. Field campaigns GoAmazon2014/5 and OP3 documented surface ozone concentrations of only 10–20 ppb over tropical forests—significantly below background levels [17,18].

Conversely, in the presence of elevated NOx (>500 ppt), characteristic of subtropical and mid-latitude regions with anthropogenic influence, isoprene stimulates ozone formation. Under these conditions, peroxy radicals oxidize NO to NO2, initiating a productive photochemical ozone formation cycle without terminating radical chains [19,20]. Additional complexity arises from the formation of long-lived nitrogen reservoir species—PAN and MPAN—which enable vertical and horizontal NOx transport over hundreds to thousands of kilometers from emission sources [21,22]. Thermal decomposition of these compounds in the upper troposphere releases NO2 and leads to delayed ozone formation far from original sources [23].

Thus, isoprene creates spatially heterogeneous and vertically stratified impacts on tropospheric ozone, with characteristics determined by local chemical regimes and transport processes. Quantitative assessment of these effects on a global scale requires three-dimensional chemistry-climate models with explicit representation of detailed isoprene oxidation chemistry.

Recognition of the importance of isoprene chemistry led to the development of specialized chemical mechanisms for climate models. The Mainz Isoprene Mechanism 1 (MIM1), developed by Pöschl et al. [24] and refined by Geiger et al. [25], represents a reduced scheme of 44 reactions and 16 chemical species derived from the detailed Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM) while preserving key features of isoprene chemistry. The mechanism explicitly describes formation of major oxidation products—methacrolein (MACR), methyl vinyl ketone (MVK), and formaldehyde (HCHO)—as well as NOx reservoir species (PAN, MPAN, organic nitrates), enabling adequate reproduction of isoprene’s impact on O3, OH, and NOx at acceptable computational cost for global modeling.

MIM1 has been successfully implemented in several leading global models. The chemistry-climate model SOCOL has employed MIM1 since SOCOLv3 to describe tropospheric isoprene chemistry [26,27], substantially improving tropical ozone simulation. The MECCA module in the EMAC model supports both MIM1 and its advanced version MIM2 [28]. Model studies with MIM1 showed that explicit representation of isoprene chemistry alters tropospheric ozone by 5–50% depending on region and altitude [29,30], confirming the necessity of including this mechanism in climate models.

However, the Russian Earth system climate model INM-CM, successfully participating in the international CMIP6 project [31,32], has until now lacked explicit representation of biogenic volatile organic compound chemistry. The model’s chemical module included complete stratospheric chemistry and basic tropospheric schemes limited to methane and carbon monoxide oxidation, precluding correct simulation of photochemical ozone formation processes in regions with high biogenic emissions.

This study aims to quantitatively assess the impact of isoprene chemistry on the global spatial distribution of tropospheric ozone and identify the physicochemical mechanisms determining this impact across different latitudinal zones and atmospheric altitudes. To achieve this objective, the MIM1 mechanism was implemented in the atmospheric component of INM-CM, and two numerical experiments were conducted for the period 2008–2019: a control run without isoprene chemistry and an experiment with activated MIM1 mechanism.

Specific research objectives include the following: (1) assess changes in tropospheric ozone concentrations caused by inclusion of isoprene chemistry across different regions and altitudes; (2) identify the role of the NOx regime in determining the sign and magnitude of ozone anomalies; (3) analyze vertical distributions of isoprene and its oxidation products (MACR, PAN, MPAN) to explain mechanisms of ozone impact; and (4) evaluate the contribution of long-range transport of nitrogen reservoir species to ozone anomaly formation in regions remote from emission sources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. INM-CM6.0 Climate Model

This study employs the INM-CM6.0 Earth system climate model developed at the Institute of Numerical Mathematics of the Russian Academy of Sciences, comprising interacting components of atmosphere, ocean, sea ice, and land surface [31,33]. The atmospheric component operates at a horizontal resolution of 2° × 1.5° (longitude × latitude) with 73 vertical σ-levels extending from the top of the atmosphere (σ ≈ 0.0001, ~60 km altitude) to near the surface (σ = 0.993, ~7 m above ground at standard sea-level pressure). The σ-coordinate system (σ = p/p_surface) provides terrain-following discretization with 6 vertical levels within the planetary boundary layer (0–2 km), and 14 levels in the troposphere adequate for representing isoprene emission, oxidation chemistry, and vertical transport processes [31,33].

Prior to MIM1 implementation, the model’s chemical module included complete stratospheric chemistry (Ox, NOy, HOx, ClOx, BrOx families) and a basic tropospheric scheme for methane (CH4) and CO oxidation [34]. Photochemical rate constants are calculated online accounting for solar zenith angle, total ozone column, and cloudiness. INM-CM6.0 participates in the CMIP6 project and exhibits an equilibrium climate sensitivity of ~3.3 °C for CO2 doubling, within the range of CMIP6 ensemble mean values [32,33].

2.2. MIM1 Isoprene Oxidation Mechanism

To explicitly represent isoprene chemistry, the Mainz Isoprene Mechanism 1—a reduced tropospheric isoprene oxidation scheme developed for global models [24,25]—was implemented in INM-CM6.0. The mechanism comprises 16 chemical species (Table 1) and 44 reactions describing the main pathways of isoprene (C5H8) oxidation by OH, O3, and NO3, with formation of intermediate products and nitrogen reservoir species.

Table 1.

Major chemical species of the MIM1 mechanism added to INM-CM6.0 (a complete list with thermodynamic properties is in Appendix A).

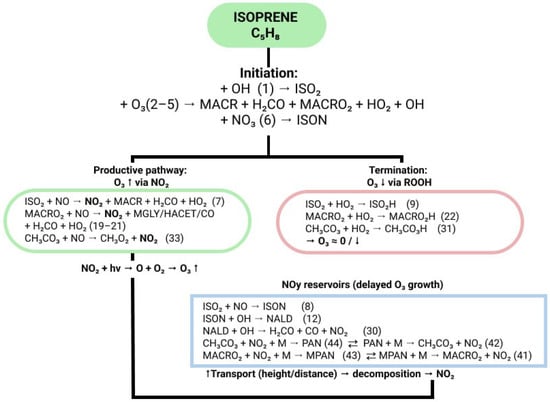

The interaction of these chemical species in MIM1 is realized through three principal reaction pathways that determine isoprene’s impact on tropospheric ozone (Figure 1): a productive ozone formation cycle via NO oxidation to NO2, a termination pathway through hydroperoxide formation, and formation of long-lived NOx reservoirs with subsequent transport and delayed NO2 release.

Figure 1.

Simplified scheme of the main reaction pathways in the MIM1 mechanism. Green highlights the productive O3 formation pathway through the NO2 cycle, red shows the termination pathway via hydroperoxide formation, and blue indicates formation of NOy reservoir species with subsequent transport and delayed NO2 release. Numbers in parentheses refer to reaction numbers in the complete MIM1 scheme. Complete reaction rate constants, temperature dependencies, and branching ratios for all 44 reactions are provided in Appendix B.

Table 1 summarizes the 16 chemical species added to INM-CM6.0 as part of the MIM1 isoprene oxidation mechanism and their functional roles. A complete listing of all chemical species in the INM-CM6.0 atmospheric chemistry module (including base tropospheric and stratospheric chemistry species as well as the 16 MIM1 additions) with molecular formulas, molecular weights, and thermodynamic properties is provided in Appendix A.

Isoprene oxidation is initiated predominantly via reaction with hydroxyl radical (reaction 1 in Figure 1, ~90% of total daytime C5H8 sink), forming the isoprene peroxy radical ISO2. Contributions from ozonolysis (reactions 2–5 in Figure 1) and nitrate radical oxidation (reaction 6 in Figure 1) account for ~10% and ~1%, respectively, with ozonolysis playing an important role in nighttime chemistry and leading to direct formation of MACR, formaldehyde (H2CO), and other carbonyl compounds. Oxidation via NO3 forms isoprene nitrate (ISON), providing nighttime NOx sequestration.

The subsequent fate of peroxy radicals ISO2 and MACRO2 depends critically on the atmospheric NOx regime and determines the sign of isoprene’s influence on tropospheric ozone. Under low-NOx conditions (<100 ppt), typical of remote tropical forests, reactions with hydroperoxy radical HO2 dominate (reactions 9, 22, 31 in Figure 1). The resulting hydroperoxides (ISO2H, MACRO2H, CH3CO3H) have atmospheric lifetimes of several hours to days—substantially longer than peroxy radical lifetimes (seconds)—and do not directly participate in the rapid NO-to-NO2 conversion required for efficient photochemical ozone production. While these hydroperoxides eventually photolyze to regenerate OH radicals, this occurs on timescales much longer than the isoprene oxidation cycle (~1–2 h) [19], effectively terminating the radical chain and resulting in net OH suppression under low-NOx conditions. Critically, these reactions do not produce NO2—the key photochemical ozone precursor—which explains the observed suppression of surface O3 in the tropics under high biogenic emissions.

In contrast, under elevated NOx conditions (>500 ppt), characteristic of subtropical and mid-latitude regions with anthropogenic influence, peroxy radicals preferentially oxidize NO to NO2 (reactions 7, 19–21, 33 in Figure 1). The resulting NO2 photolyzes to generate atomic oxygen O(3P), which recombines with molecular oxygen to form ozone. This productive cycle is further enhanced by OH regeneration through HO2 + NO reactions, sustaining the oxidation chain without termination. Consequently, isoprene becomes an efficient promoter of photochemical ozone formation under moderately polluted conditions.

A fundamentally important feature of the MIM1 mechanism is the explicit representation of nitrogen reservoir species—PAN and MPAN—formed through reversible reactions of acylperoxy radicals with NO2 (reactions 42–44 and 41–43 in Figure 1). These compounds are thermally stable at low upper tropospheric temperatures (PAN lifetime reaches several weeks at 250 K), enabling convective transport to 8–15 km altitude and horizontal transport over hundreds to thousands of kilometers. Upon subsequent warming or transport to warmer regions, thermal decomposition of PAN and MPAN releases NO2, providing delayed ozone formation in the middle and upper troposphere far from original isoprene emission sources. This mechanism of vertical and horizontal NOx redistribution through reservoir species is key to understanding the positive ozone anomalies in the middle troposphere identified in this study.

Additional NOx sequestration pathways are realized through ISON formation (reaction 8 in Figure 1) and its subsequent oxidation to form nitrooxy acetaldehyde (NALD) (reaction 12 in Figure 1). Unlike PAN and MPAN, these compounds are less stable and more rapidly recycle NO2 into the photochemical cycle through photolysis and oxidation (reaction 30), providing local NOx redistribution in the surface layer.

The MIM1 mechanism was integrated into the existing chemical solver of INM-CM6.0 without modifying the base numerical scheme. Reaction rate constants were updated from the original MIM1 formulation [33,34] using the latest JPL recommendations [35] where available, along with evaluated kinetic data from IUPAC and laboratory studies for reactions not covered by JPL. A complete listing of all chemical reactions in the INM-CM6.0 atmospheric chemistry module (including base tropospheric and stratospheric chemistry as well as the 44 MIM1 additions) with chemical equations, rate constant expressions, and literature sources is provided in Appendix B. Photolysis coefficients (for 8 photolysis reactions among the 44 MIM1 reactions) are calculated online at each time step accounting for solar zenith angle, total ozone column, altitude, and cloudiness. Addition of 16 new chemical species and 44 new reactions to the existing base chemistry increased the computational cost of the chemical module by ~15%, which is acceptable for long-term climate simulations.

2.3. Biogenic and Anthropogenic Emissions

Emissions of isoprene (C5H8), formaldehyde (HCHO), formic acid (HCOOH), and methanol (CH3OH) are prescribed from the ACCMIP (Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Model Intercomparison Project) database, developed to support CMIP5 climate research and IPCC AR5 [36]. Emission fields at 0.5° × 0.5° spatial resolution for the baseline year 2000 were interpolated to the model grid of 2° × 1.5° and prescribed as monthly climatological means.

Global isoprene emissions in the employed database total 503 Tg C yr−1, with pronounced geographical heterogeneity. Maximum fluxes (>5 mg m−2 day−1) are concentrated in tropical regions: the Amazon basin contributes ~32% of global emissions, equatorial Africa ~24%, and Southeast Asia ~18%. Subtropical and mid-latitudes (20–40°) provide an additional ~20%, with marked emission seasonality: summer fluxes exceed winter values by 50–100 fold at mid-latitudes. Formaldehyde (13 Tg yr−1) and formic acid (8 Tg yr−1) emissions include both direct biogenic sources and secondary photochemical formation from isoprene and other VOCs.

The use of fixed climatological emissions from the baseline year 2000 for the analyzed period 2008–2019 is justified by the experimental design. The primary objective is to isolate and quantitatively assess the impact of the MIM1 chemical mechanism on tropospheric ozone distribution, rather than to reproduce interannual variability of a specific historical period. Fixed emissions ensure experimental clarity by eliminating uncertainties associated with interannual variations in biogenic fluxes. Moreover, trends in global biogenic isoprene emissions over 2000–2019, estimated from GOME-2 and OMI satellite data, are less than 10% [37,38]—significantly smaller than typical emission inventory uncertainties ±50–100% [4,5]. Thus, using climatological emissions does not introduce substantial systematic errors in assessing qualitative and quantitative effects of isoprene chemistry implementation.

While this approach limits our ability to reproduce specific interannual anomalies observed in satellite data (e.g., El Niño-driven flux variations), it provides a robust assessment of the mean chemical effect of isoprene, which is the primary goal of this implementation study. Future work incorporating interactive emissions (see Section 4.4) will enable investigation of emission–climate feedbacks and interannual variability.

2.4. Experimental Design

To isolate the influence of isoprene chemistry on atmospheric composition, two 12-year numerical experiments (2008–2019) were conducted with identical model configurations, boundary conditions, and external radiative forcings. The experiments differed only in the presence or absence of the isoprene oxidation mechanism (Table 2).

Table 2.

Design of numerical experiments.

The first two years of each experiment (2008–2009) served as a spin-up period for atmospheric chemical equilibration. The relaxation time for tropospheric chemical fields is 6–12 months, determined by characteristic lifetimes of key tracers: isoprene (~2 h), oxidation products (~1 day), and NOx reservoirs (days to weeks). Results were analyzed for the ten-year period 2010–2019 with averaging to obtain climatological characteristics and minimize interannual variability effects.

The following variables were analyzed to quantitatively assess isoprene impact. Tropospheric ozone (O3) concentrations characterize isoprene’s influence on photochemical ozone formation. Hydroxyl radical concentrations reveal changes in atmospheric oxidizing capacity. Nitrogen oxides (NO, NO2, NO3) reflect impacts on the nitrogen cycle.

Isoprene oxidation products (MACR, MACRO2, ISO2H, and others) enable tracking of isoprene degradation pathways under different conditions. Nitrogen reservoir species (PAN, MPAN, organic nitrates) are essential for understanding long-range NOx transport.

Particular attention was devoted to regions with high biogenic emissions: Amazonian tropical forests, equatorial Africa, and Southeast Asia. Mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere during summer, when isoprene emissions reach maximum values, were also analyzed.

Isoprene’s impact was evaluated through several metrics. Absolute concentration differences were calculated as

Δ[X] = [X]MIM1 − [X]CTRL.

Relative changes were determined as

δ[X] = ([X]MIM1 − [X]cTRL)/[X]cTRL × 100%.

Vertical zonal-height cross-sections of concentrations were constructed to analyze altitude distribution of effects. Temporal dynamics were assessed through analysis of four representative months: January (Southern Hemisphere summer, maximum isoprene emissions in southern tropics), April (Northern Hemisphere spring, transition season), July (Northern Hemisphere summer, maximum emissions in northern subtropics and mid-latitudes), and October (Northern Hemisphere autumn, transition season). This approach reveals seasonal variability of effects associated with the annual cycle of biogenic emissions and changing photochemical conditions.

The quality of simulated atmospheric constituents was evaluated through comparison of MIM1 experiment results with satellite reanalyses and independent model calculations for 2010–2019.

2.5. Data Verification

For tropospheric ozone, three reanalyses were used: CAMS (Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, 0.75° resolution) [39], MERRA-2 (NASA Modern-Era Retrospective analysis, 0.5° × 0.625°) [40,41], and ERA5 (ECMWF Reanalysis v5, 0.25°) [42]. Using three independent datasets enables assessment of reference data uncertainty. Carbon monoxide and hydroxyl radical were verified against CAMS data and SOCOLv3 model results with the MIM1 mechanism [43]. SOCOLv3 was selected for OH verification due to the absence of global measurements of this radical and the need to verify correct MIM1 implementation.

All datasets were interpolated to the INM-CM6.0 vertical grid (73 levels) with climatological means calculated for 2010–2019. Latitude–height cross-sections were analyzed at four principal altitudes (2 km, 5 km, 15 km, 30 km).

Tracer selection was determined by their role in isoprene chemistry: CO as the final oxidation product of all organic compounds and an integral indicator of tropospheric chemistry, O3 as the product of the NOx photochemical cycle and the main research focus, and OH as the central component of the isoprene oxidation mechanism. Particular attention was devoted to tropical regions with high biogenic emissions and Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes during summer, where isoprene influence is most significant.

3. Results

3.1. Intermodal Comparison

Before analyzing isoprene’s influence, an intermodal comparison was conducted to assess the quality of simulated key atmospheric components. INM-CM results were compared with CAMS, MERRA-2, and ERA5 reanalyses, and with the SOCOL chemistry-climate model in which the MIM1 mechanism is already implemented. This approach enables evaluation of isoprene chemistry implementation effectiveness and identification of regions with best and worst agreement.

Carbon monoxide serves as an indicator of tropospheric chemistry quality. While CO is further oxidized to CO2 (CO + OH → CO2 + H), the relatively long atmospheric lifetime of CO (~1–2 months) makes it a useful tracer of tropospheric photochemical processes. Total atmospheric CO results from both direct emissions (biomass burning, fossil fuel combustion) and secondary formation from oxidation of CH4 and non-methane VOCs. In remote tropical regions with high biogenic emissions, isoprene oxidation provides a significant secondary source of CO.

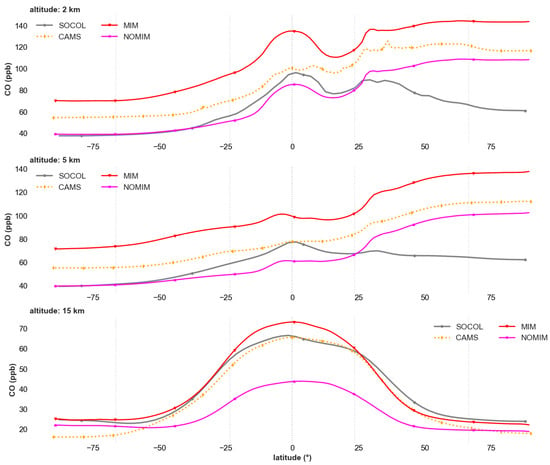

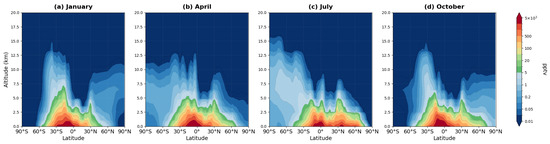

Latitudinal CO profiles at various altitudes (Figure 2) reveal regionally specific changes in INM-CM after incorporating isoprene chemistry, with improvements most pronounced in the tropical lower and middle troposphere where biogenic VOC emissions are highest.

Figure 2.

Latitudinal distribution of carbon monoxide (CO, ppb) at altitude levels of 2 km (upper panel), 5 km (second panel), 15 km (third panel). Shown are results from SOCOL (gray line), CAMS (orange dashed line), INM-CM with isoprene chemistry via MIM1 mechanism (red line), and baseline INM-CM without isoprene chemistry—NOMIM (pink line). Averaging period: 2010–2019.

At 2 km altitude, the MIM1 experiment substantially improves agreement with reanalyses in the tropics and subtropics (30° S–30° N), where concentrations of 100–140 ppb approach CAMS (80–120 ppb) and MERRA-2 values. This isoprene-derived CO represents approximately 15–30 ppb (~15–25% of total CO) in the tropical boundary layer. The baseline model version (NOMIM) systematically underestimates CO concentrations in this region by 20–30%, missing the secondary CO contribution from isoprene oxidation. However, in northern mid-latitudes (40–60° N), MIM1 overestimates concentrations (130–150 ppb) compared to CAMS and MERRA-2 (100–120 ppb), suggesting that the model may overestimate either biogenic emissions or secondary CO formation efficiency in this region, or that discrepancies in transport or primary emissions contribute to the bias.

At 5 km altitude, the pattern is similar: MIM1 substantially improves agreement with reanalyses in the tropics (±20°), where discrepancies decrease from 30–40% (NOMIM) to 10–15% (MIM1). In northern latitudes, systematic overestimation of 20–30% persists, consistent with the 2 km pattern. The SOCOL model demonstrates CO distributions similar to INM-CM MIM1 in the tropics (80–100 ppb), indicating comparable representation of secondary CO sources in models with explicit isoprene chemistry.

In the upper troposphere (15 km), MIM1 shows improved agreement with CAMS in the tropical zone (60–70 ppb), whereas NOMIM systematically underestimates concentrations by 15–20% (40–50 ppb). This improvement reflects efficient vertical transport of CO from isoprene oxidation products in the boundary layer to the upper troposphere via deep convection. In the subtropics and mid-latitudes, differences between model versions are smaller, as the contribution of locally produced isoprene-derived CO decreases with distance from major emission regions.

Overall, the inclusion of isoprene chemistry selectively improves CO simulation in regions and altitudes where biogenic VOC emissions contribute significantly to secondary CO formation (tropical lower and middle troposphere), while discrepancies persist in mid-latitudes, likely reflecting uncertainties in emissions inventories, transport, or other aspects of tropospheric chemistry beyond isoprene.

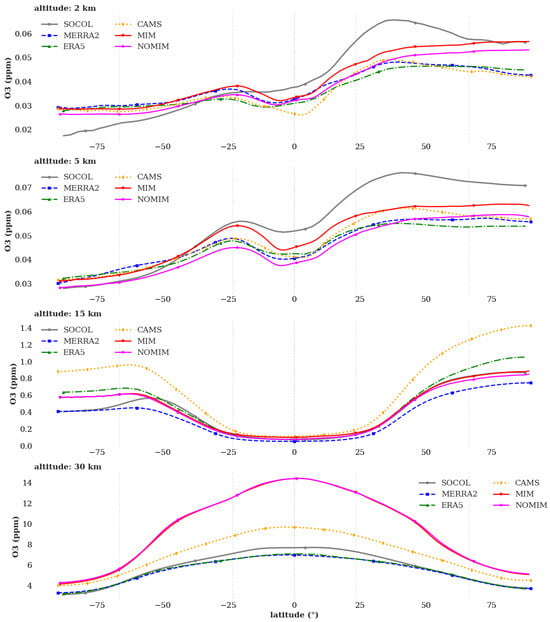

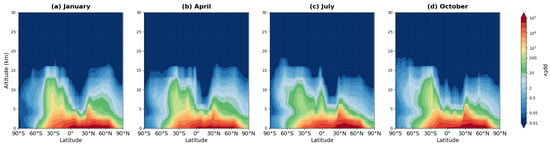

Latitudinal O3 profiles at various altitudes (Figure 3) demonstrate regionally specific changes in ozone simulation after implementing isoprene chemistry. The magnitude of isoprene-induced changes (typically 5–15 ppb in the lower and middle troposphere) is comparable to or smaller than the spread among reanalyses and models (10–20 ppb), indicating that while isoprene chemistry affects model performance, other uncertainties in emissions, transport, and chemistry remain significant.

Figure 3.

Latitudinal distribution of ozone (O3, ppm) at altitude levels of 2 km (upper panel), 5 km (second panel), 15 km (third panel), and 30 km (lower panel). Shown are results from SOCOL (gray line), MERRA-2 (blue dashed line), ERA5 (green dash-dot line), CAMS (orange dashed line), INM-CM with isoprene chemistry via MIM1 mechanism (red line), and baseline INM-CM without isoprene chemistry—NOMIM (pink line). Averaging period: 2010–2019.

At 2 km altitude, the MIM1 experiment improves tropical performance (20° S–20° N), where concentrations decrease from 45–55 ppb (NOMIM) to 35–45 ppb, moving closer to CAMS values (30–35 ppb) and SOCOL (30–40 ppb). This reduction in tropical ozone overestimation from 15–20 ppb to 5–10 ppb represents an improvement, though a systematic positive bias persists even with isoprene chemistry included. The remaining discrepancy likely reflects uncertainties in NOx emissions, boundary layer chemistry, or other tropospheric processes. In the subtropics (20–40°), isoprene inclusion leads to increased ozone concentrations (50–55 ppb versus 40–45 ppb in CAMS), amplifying disagreement with reanalyses and highlighting the need for further evaluation of the model’s NOx-VOC-O3 chemistry in this transition region.

At 5 km altitude, MIM1 shows improved agreement with SOCOL in the tropics (55–60 ppb), consistent with the expected effect of isoprene chemistry under low-NOx conditions. However, both MIM1 and NOMIM systematically overestimate concentrations in the subtropics of both hemispheres by 10–15% relative to CAMS, MERRA-2, and ERA5, suggesting that biases in this region are not primarily related to isoprene chemistry but may reflect issues with stratosphere-troposphere exchange, NOx chemistry, or other factors. In mid-latitudes (40–60°), both model versions show satisfactory agreement with CAMS, with discrepancies not exceeding 10%.

At 30 km altitude (lower stratosphere), both MIM1 and NOMIM show similar ozone distributions, as expected since isoprene chemistry operates only in the troposphere and does not directly affect stratospheric ozone. Both model versions systematically overestimate concentrations in the subtropics and mid-latitudes relative to some reanalyses and models. The similarity between MIM1 and NOMIM at this altitude confirms that the observed differences at lower altitudes are attributable to isoprene chemistry rather than other model changes. Best agreement across all model versions is observed in polar regions (>60°) at all altitudes, where discrepancies do not exceed 10%.

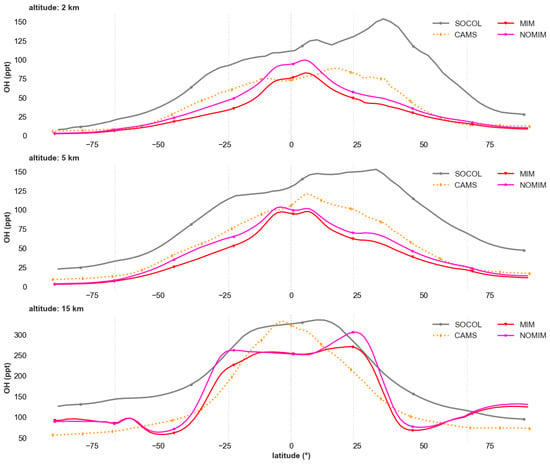

Latitudinal OH distribution at various altitudes (Figure 4) reveals substantial model improvement after incorporating isoprene chemistry, particularly in reducing systematic overestimation. The baseline NOMIM version systematically overestimates OH concentrations by factors of 2–4 relative to all models at all altitudes and latitudes, indicating fundamental deficiencies in simplified tropospheric chemistry that neglects major OH sinks from isoprene oxidation.

Figure 4.

Latitudinal distribution of hydroxyl radical (OH, ppt) at altitude levels of 2 km (upper panel), 5 km (second panel), 15 km (third panel). Shown are results from SOCOL (gray line), CAMS (orange dashed line), INM-CM with isoprene chemistry via MIM1 mechanism (red line), and baseline INM-CM without isoprene chemistry—NOMIM (pink line). Averaging period: 2010–2019.

At 2 km altitude, isoprene chemistry implementation reduces tropical OH concentrations from 100 ppt (NOMIM) to 50–80 ppt, bringing them closer to CAMS values (60–80 ppt) and SOCOL (50–100 ppt). In mid-latitudes (±30–60°), improvement is even more pronounced: MIM1 reduces concentrations from 100–150 ppt to 50–80 ppt, although slight overestimation of 20–30% relative to CAMS persists. Best agreement is achieved in the equatorial zone (10° S–10° N), where discrepancies with reanalyses and models do not exceed 15–20%.

At 5 km altitude, the pattern is similar: MIM1 reduces discrepancies with CAMS by factors of 2–3 across all latitudinal zones. Best agreement persists in the tropics and subtropics (30° S–30° N), where concentrations are 50–100 ppt versus 100–120 ppt in NOMIM. SOCOL shows distribution close to MIM1 in the tropics, but higher concentrations in northern mid-latitudes (100–150 ppt), reflecting differences in HOx chemistry representation.

In the upper troposphere (15 km), NOMIM demonstrates qualitatively different distribution compared to all reference data, with a maximum in northern mid-latitudes instead of the equatorial zone. Isoprene chemistry implementation corrects this structure: a characteristic tropical maximum form (250–270 ppt), close to SOCOL (300–350 ppt) and occupying an intermediate position relative to CAMS (300–350 ppt). In high latitudes (>60°), agreement is poorer, with persisting overestimation of 30–50%.

Intermodel comparison demonstrates selective INM-CM improvement after implementing isoprene chemistry, with the greatest progress in regions where biogenic VOC emissions are most significant. Substantial improvements were achieved in OH simulation (2–3 fold reduction in reanalysis discrepancies at all altitudes globally) and tropical CO (reduction in discrepancies from 30–40% to 10–15% in the lower and middle troposphere, 0–10 km, 30° S–30° N). The magnitude of OH improvement is notable, though the relative effect of isoprene on OH concentrations (30–50% reduction in the tropics) is smaller than its effect on secondary CO (40–100% increases in the tropical middle troposphere). However, CO overestimation in northern mid-latitudes (40–60°N) at 2–5 km persists in the MIM1 version, suggesting continued uncertainties in emissions inventories, transport processes, or other chemical mechanisms in this region. For ozone, improvement is selective and modest in magnitude: in the tropical lower troposphere (0–5 km, 20° S–20° N), overestimation decreases from 15–20 ppb to 5–10 ppb, though systematic positive bias persists. However, in the subtropical middle troposphere (5–12 km, 20–40°), ozone overestimation increases by 5–10 ppb, indicating that isoprene chemistry alone does not resolve all model biases and that uncertainties in NOx emissions, transport, and other chemical processes remain significant.

Regional analysis shows that best agreement with reanalyses is achieved in the tropical zone (20° S–20° N) at 0–8 km altitude for all examined components, where discrepancies with CAMS are 10–20%. Poorest agreement persists in northern mid-latitudes (40–60° N) for CO (20–30% overestimation at 0–5 km) and in the subtropical middle troposphere (5–12 km, 20–40°) for ozone (15–25% overestimation). In high latitudes (>60°), simulation quality is intermediate for all components.

The similarity of INM-CM MIM1 and SOCOL results in key regions (tropics, 0–10 km) indicates that both models produce comparable tropospheric composition when isoprene chemistry is included, though this comparison of absolute concentrations does not directly validate the isoprene mechanism implementation since the models differ in base chemistry, dynamics, and emissions. Persisting discrepancies between models at mid and high latitudes likely reflect differences in dynamical cores, transport parameterizations, HOx-NOx chemistry representation, and emissions inventories rather than isoprene chemistry specifically, defining directions for further INM-CM improvement.

This enables transition to the main scientific objective—analysis of physicochemical mechanisms of isoprene’s influence on the spatial distribution of tropospheric ozone and other atmospheric constituents.

3.2. Isoprene’s Influence on Tropospheric Chemical Composition

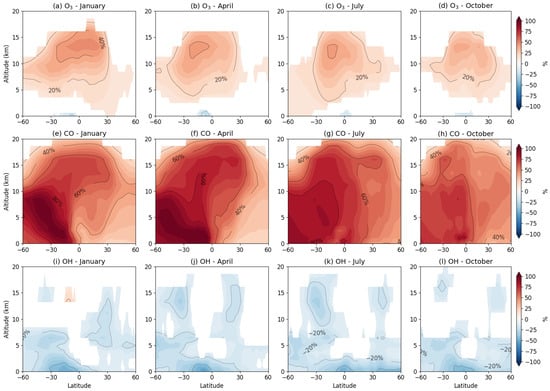

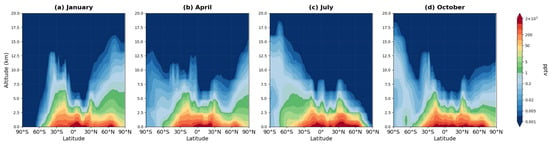

Inclusion of isoprene chemistry leads to coherent changes in ozone, carbon monoxide, and hydroxyl radical concentrations, reflecting an integrated complex of photochemical processes. Figure 5 presents relative changes in zonally averaged concentrations of these components for four representative months during 2010–2019.

Figure 5.

Relative changes in zonally averaged concentrations of (a–d) ozone O3, (e–h) carbon monoxide CO, and (i–l) hydroxyl radical OH upon inclusion of isoprene chemistry via the MIM1 mechanism for January, April, July, and October. Changes shown as percentages: Δ = (MIM1 − CTRL)/CTRL × 100%. Note that for CO, the large relative increases (40–100%) in the tropical middle and upper troposphere reflect isoprene’s substantial fractional contribution to secondary CO in regions with low background concentrations (~20–40 ppb), though absolute increases (~10–20 ppb) remain modest compared to boundary layer values (~15–30 ppb from total ~100–140 ppb).

In the tropical surface layer (0–5 km, 20° S–20° N), isoprene causes simultaneous reduction in ozone by 10–20% and hydroxyl radical by 15–30% (Figure 5a–d,i–l). These changes are causally linked: the initial isoprene oxidation reaction (C5H8 + OH → products) consumes OH, while the resulting isoprene peroxy radicals under low-NOx conditions react preferentially with HO2, terminating radical chains without NO2 formation. The result is suppression of the photochemical ozone formation cycle. Maximum intensity of these effects occurs in the equatorial zone (0–10°) during the respective hemisphere’s summer season, when biogenic emissions reach their highest values.

Concurrent with ozone and OH suppression in the surface layer, isoprene increases carbon monoxide concentrations by 30–60% in the same region (Figure 5e–h). This increase reflects isoprene’s role as a CO source through an oxidation chain: isoprene sequentially degrades via formaldehyde and methacrolein, ultimately forming carbon monoxide. Thus, in the tropical lower troposphere, isoprene acts as a consumer of oxidizing capacity (reducing O3 and OH) and a source of incomplete oxidation products (increasing CO).

In the middle troposphere (8–15 km), the pattern changes qualitatively (Figure 5a–d). Ozone increases by 10–20% in the subtropical belt (10–30°) of both hemispheres, while OH impact becomes weak and heterogeneous (changes less than 10%, Figure 5i–l). This change is linked to vertical transport of nitrogen reservoir species. In the surface layer, PAN and MPAN form during isoprene oxidation; having long lifetimes, they are transported by convection to the upper troposphere. There, at low temperatures, they thermally decompose, releasing NO2 and initiating photochemical ozone formation. This mechanism provides spatial separation: oxidizing capacity consumption in the tropical surface layer and delayed ozone formation in the subtropical middle troposphere.

CO concentrations show maximum relative changes (+60–100%) in the middle and upper troposphere (8–18 km) of the tropical belt (Figure 5e–h). Such high relative values result from two factors: (1) low background CO concentrations at these altitudes (20–40 ppb versus 100–140 ppb at the surface), making modest absolute increases appear large in relative terms; and (2) efficient vertical transport of isoprene oxidation products. In absolute terms, isoprene contributes approximately 15–30 ppb to total CO in the tropical boundary layer (~15–25% of total) and 10–20 ppb in the middle troposphere (30–60% of baseline values).

In subtropical latitudes (20–35°), isoprene causes ozone increases at all altitudes: from +5–10% at the surface to +15–20% in the middle troposphere (Figure 5a–d). This qualitative difference from the tropics is determined by the NOx regime. At NO concentrations > 500 ppt, isoprene peroxy radicals preferentially oxidize NO to NO2, regenerating OH and initiating a productive ozone formation cycle without radical termination. Consequently, in the subtropics, isoprene acts as an ozone formation catalyst rather than a suppressor. OH impact in the subtropics is minimal (changes less than 15%, Figure 5i–l), reflecting the balance between initial OH consumption during isoprene oxidation and its regeneration through subsequent reactions.

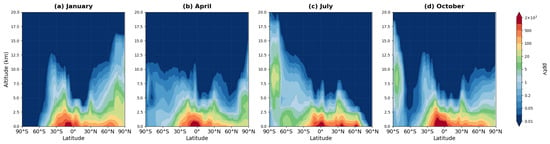

The inclusion of isoprene chemistry substantially alters the distribution of reactive nitrogen (NOy) in the troposphere through formation of organic nitrogen reservoir species (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relative changes in zonally averaged reactive nitrogen (NOy = NO + NO2 + NO3 + 2 × N2O5 + HNO3 + organic nitrates + PAN + MPAN) concentrations upon inclusion of isoprene chemistry via the MIM1 mechanism for January, April, July, and October. Changes shown as percentages: Δ = (MIM1 − CTRL)/CTRL × 100%. Positive values indicate NOy increases due to formation of nitrogen reservoir species (PAN, MPAN, ISON, NALD) from isoprene oxidation. Only statistically significant values (p < 0.05) are shaded. Averaging period: 2010–2019.

In the tropical lower troposphere (0–5 km, 20° S–20° N), NOy concentrations increase by 20–40% during peak emission seasons, reflecting formation of short-lived organic nitrates (ISON, NALD) and longer-lived reservoir species (PAN, MPAN) from isoprene oxidation. The largest relative NOy increases (40–60%) occur in the tropical middle troposphere (5–10 km), where PAN and MPAN accumulate after convective transport from the boundary layer. This vertical redistribution of reactive nitrogen fundamentally alters the local NOx-VOC-O3 photochemical regime: regions with elevated NOy from isoprene chemistry transition toward a more NOx-saturated regime where additional VOC emissions more efficiently produce ozone.

The seasonal pattern of NOy changes (Figure 6) closely follows the isoprene emission cycle, with maximum impacts during the respective summer hemisphere when biogenic emissions peak. This NOy redistribution mechanism—local sequestration near emission sources combined with long-range transport via PAN—explains the complex two-layer ozone response: surface suppression under low-NOx conditions and middle tropospheric enhancement through delayed NOx release after reservoir decomposition.

The spatial distribution of CO changes demonstrates clear localization in the tropical and subtropical belt (30° S–30° N) where biogenic emissions are concentrated (Figure 5b). In mid and high latitudes, isoprene’s impact on CO is minimal (less than 20%), contrasting with the broader distribution of ozone changes. This difference stems from isoprene’s influence on ozone in mid-latitudes being mediated by long-range transport of nitrogen reservoir species (PAN), whereas the CO contribution is determined by local isoprene oxidation with limited spatial extent.

Seasonal dynamics of all components coherently follow the annual cycle of biogenic emissions, with maximum effects in the Southern Hemisphere during January and in the Northern Hemisphere during July. Transition months (April and October) show relatively symmetric equatorial distributions with moderate intensity. However, seasonal variation amplitude differs among components: for CO and O3 it reaches factors of 1.5–2, whereas OH seasonal variability is less pronounced due to multiple sources and sinks unrelated to isoprene chemistry.

The vertical impact structure reflects differences in chemical properties and lifetimes of compounds. Isoprene (lifetime ~1–2 h) is destroyed in the surface layer where its impact is maximal. Primary oxidation products (formaldehyde, methacrolein) are transported to 5–8 km, providing a secondary CO source and intermediate ozone impact. Long-lived NOx reservoirs (PAN, MPAN) reach 12–15 km altitude, where they determine maximum positive ozone impact through thermal decomposition and NO2 release.

Isoprene’s impact on tropospheric chemical composition is determined by three key factors: (1) NOx concentrations (determining the sign of ozone impact—suppression under low-NOx, enhancement under elevated-NOx); (2) vertical transport of nitrogen reservoir species (providing spatial separation between surface impacts and middle tropospheric effects); and (3) seasonality of biogenic emissions (defining temporal dynamics). This integrated understanding of isoprene’s multi-component, altitude-dependent, and regime-specific effects is essential for accurate tropospheric chemistry simulation in climate models.

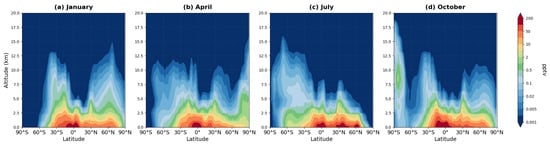

3.3. Vertical Distribution of Isoprene and Its Oxidation Products

The spatial distribution of isoprene (C5H8) and its oxidation products—PAN and MPAN—demonstrates substantial differences in vertical structure that determine the character of isoprene’s influence on ozone.

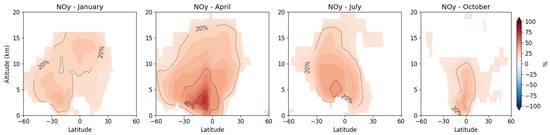

3.3.1. Isoprene

Figure 7 shows the zonally averaged vertical distribution of isoprene mixing ratios for four representative months during the 2008–2019 period.

Figure 7.

Zonally averaged latitude–altitude distribution of isoprene (C5H8) mixing ratio (pptv) simulated by the MIM model, averaged over 2008–2019 for (a) January, (b) April, (c) July, and (d) October.

Isoprene exhibits pronounced localization in the lower troposphere over tropical and subtropical regions. Maximum mixing ratios (1500–2000 pptv) occur near the surface in the equatorial zone (10° S–10° N, panels a–d). A key feature is the sharp exponential decrease in concentrations with altitude: by 5 km, mixing ratios decline to 200–300 pptv, and above 6 km they become negligibly small (less 10 pptv). This reflects isoprene’s short atmospheric lifetime (on the order of a few hours) and rapid chemical oxidation.

The latitudinal distribution demonstrates an equatorially symmetric structure with gradual decrease toward the poles: from maximum values in the tropics to near-zero concentrations (less than 1 pptv) at high latitudes. Seasonal variations are evident across all panels, with enhanced concentrations during the respective summer hemisphere (panel a shows Southern Hemisphere summer maximum, panel (c) shows Northern Hemisphere summer maximum), consistent with vegetation activity patterns. The hemispheric asymmetry in panels (b) and (d) reflects the interhemispheric differences in land distribution and biogenic emissions sources.

3.3.2. Role of Nitrogen Reservoir Species (PAN, MPAN, ISON, NALD)

A key mechanism by which isoprene influences middle tropospheric ozone involves nitrogen reservoir species—PAN, MPAN, ISON, and NALD. These compounds differ in their atmospheric lifetimes and consequently in their spatial scales of impact. Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 present the vertical distributions of these species.

Figure 8.

Zonally averaged latitude-altitude distribution of PAN mixing ratio (pptv, logarithmic scale) simulated by the MIM model, averaged over 2008–2019 for (a) January, (b) April, (c) July, and (d) October.

Figure 9.

Zonally averaged latitude-altitude distribution of MPAN mixing ratio (pptv, logarithmic scale) simulated by the MIM model, averaged over 2008–2019 for (a) January, (b) April, (c) July, and (d) October.

Figure 10.

Zonally averaged latitude-altitude distribution of ISON mixing ratio (pptv, logarithmic scale) simulated by the MIM model, averaged over 2008–2019 for (a) January, (b) April, (c) July, and (d) October.

Figure 11.

Zonally averaged latitude-altitude distribution of NALD mixing ratio (pptv, logarithmic scale) simulated by the MIM model, averaged over 2008–2019 for (a) January, (b) April, (c) July, and (d) October.

PAN exhibits a qualitatively different vertical structure compared to isoprene. While both species show maximum mixing ratios near the surface in tropical regions where formation occurs (50,000–100,000 pptv for PAN, panels a–d), PAN extends to much greater altitudes than isoprene due to its longer atmospheric lifetime. Substantial PAN concentrations (1000–10,000 pptv) persist up to 8–12 km altitude, with detectable amounts reaching 15–18 km. This extended vertical distribution contrasts sharply with isoprene, which is largely confined below 5–6 km due to rapid oxidation (lifetime ~1–2 h).

MPAN occupies an intermediate position between highly reactive isoprene and stable PAN. Maximum concentrations (1000–2000 pptv) are localized in the tropical belt at 4–8 km altitude—substantially lower than PAN maxima. Vertical penetration of MPAN is limited: by 12–15 km, concentrations decrease to 20–200 pptv (panels a–d). The latitudinal distribution of MPAN is significantly narrower than that of PAN: substantial concentrations (above 500 pptv) are confined primarily to the tropical belt (20° S–20° N), reflecting shorter lifetime and more limited transport range compared to PAN. Seasonal patterns show enhanced concentrations in the respective summer hemisphere, with clear hemispheric asymmetry in panels (a) and (c).

Isoprene nitrate represents a highly reactive product of isoprene oxidation and occupies an intermediate position between isoprene itself and more stable reservoir species (PAN, MPAN). Maximum ISON concentrations (800–2000 pptv) occur in the lower troposphere (0–5 km) over tropical and subtropical regions. In January (panel a), the highest values appear in the Southern Hemisphere (20° S–10° N), while in July (panel c) they shift to the Northern Hemisphere (0–40° N), reflecting the seasonality of biogenic isoprene emissions. Vertical penetration is limited: above 5 km, concentrations decrease by more than fivefold (to <200 pptv). This distribution indicates a short ISON lifetime (hours to days) and tight coupling to zones of isoprene and NOx emissions.

Nitroxy aldehyde (NALD), formed through further oxidation of ISON, exhibits even lower stability. Maximum concentrations (40–200 pptv) are observed in the surface layer (0–2 km) over tropical and subtropical forests (panels a, c). By 3–5 km altitude, values decrease several-fold (to 5–20 pptv), indicating extremely limited vertical transport. The latitudinal distribution of NALD is narrower than that of ISON: significant concentrations are found almost exclusively in regions with high biogenic isoprene emissions (20° S–20° N in panel a, 20–40° N in panel c). This distribution underscores the local character of NALD and its role in rapid NO2 recycling within the photochemical cycle.

The comparison of vertical distributions of isoprene and nitrogen reservoir species explains the observed two-layer structure of ozone impacts. In the lower troposphere (0–5 km), high concentrations of isoprene and short-lived products (ISON, NALD) under low-NOx conditions lead to ozone suppression through radical termination reactions. Isoprene itself does not reach higher altitudes due to rapid oxidation.

In the middle troposphere (8–15 km), isoprene is absent, but high concentrations of PAN and moderate concentrations of MPAN persist. Thermal decomposition of these compounds releases NO2 far from emission sources and at altitudes where NOx concentrations would otherwise be low. This creates favorable conditions for efficient photochemical ozone production. Thus, isoprene influences middle tropospheric ozone indirectly through long-lived nitrogen reservoir species.

The differentiation of reservoir species by their spatial scales—local (ISON, NALD), regional (MPAN), and global (PAN)—determines the spatial structure of isoprene’s impact: from local suppression of surface ozone in the tropics to global influence on middle tropospheric ozone through long-range PAN transport.

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms of Isoprene’s Impact on Tropospheric Ozone

The numerical experiments quantitatively reproduce the NOx-dependent two-layer structure of isoprene’s influence on tropospheric ozone described in previous observational and modeling studies. The key finding is that isoprene’s net effect on atmospheric composition depends critically on the local NOx regime, which varies systematically with latitude, altitude, and proximity to anthropogenic emission sources.

The model reproduces the radical termination pathway under pristine conditions, with OH reductions of 15–30% and surface O3 reductions of 10–15 ppb quantitatively consistent with field observations. The GoAmazon2014/5 campaign documented RO2 + HO2 to RO2 + NO reaction ratios of approximately 10:1 over Amazonia [17], confirming model estimates of termination reaction dominance. The OP3 campaign measured surface ozone concentrations of 10–20 ppb over Southeast Asian tropical forests [18], matching the model’s low-NOx ozone suppression. This validation against independent observations provides confidence that the MIM1 mechanism correctly represents the chemical regime in remote biogenic-emission-dominated regions.

In contrast, the model shows ozone enhancement at all altitudes in subtropical regions, reflecting the productive photochemical cycle where isoprene peroxy radicals efficiently oxidize NO to NO2 with OH regeneration. The transition between ozone suppression and formation regimes occurs at NO ~100–500 ppt [19], consistent with the observed spatial structure in our results. This threshold has important implications for future air quality: as anthropogenic NOx emissions continue to evolve regionally, the net ozone impact of biogenic VOC emissions will shift, with declining NOx in polluted regions potentially enhancing isoprene’s ozone-suppressing effect.

The model reproduces the critical role of long-lived nitrogen reservoirs in redistributing reactive nitrogen vertically and horizontally. PAN lifetime increases from several hours at 298 K to several weeks at 250 K [21], enabling transport distances of 5000–10,000 km at characteristic jet stream velocities (~30 m/s). Airborne measurements show that PAN comprises 50–80% of reactive nitrogen in the upper troposphere over continents [22], confirming that this transport pathway is quantitatively significant. Our results show that this mechanism produces positive ozone anomalies (+10–15 ppb) in the middle troposphere even in regions where surface ozone is suppressed, fundamentally altering the vertical distribution of ozone compared to simulations without explicit isoprene chemistry.

The contrasting responses across different chemical regimes demonstrate that simplified parameterizations of biogenic VOC chemistry (e.g., lumping isoprene with other VOCs or treating it as methane-equivalent) will systematically misrepresent tropospheric ozone distribution. The magnitude of isoprene-induced changes (10–50% for O3, 30–100% for CO, 15–30% for OH depending on region) is comparable to anthropogenic perturbations and must be explicitly represented for accurate air quality and climate projections. Moreover, the NOx-dependence implies that isoprene’s net effect will change as anthropogenic emissions evolve, requiring coupled simulation of both emission classes rather than independent treatment.

4.2. Role of Nitrogen Reservoir Species in Spatial Transport

The use of fixed climatological species vertical distribution reveals a hierarchy of impact scales. ISON and NALD are characterized by surface layer localization (0–5 km) and narrow latitudinal distribution (20° S–20° N), corresponding to lifetimes of hours to days. These compounds provide rapid local NO2 recycling into the photochemical cycle near emission sources.

MPAN demonstrates intermediate distribution with maxima at 4–8 km altitude and significant concentrations within the tropical belt (20° S–20° N). Limited vertical penetration (concentrations decrease more than fivefold by 12 km) and narrow latitudinal distribution indicate MPAN’s regional impact scale.

PAN exhibits qualitatively different distribution. Maximum concentrations localize at 8–12 km altitude, while significant concentrations (3–5 × 1012 molecules cm−3) occur even at high latitudes (>60°) in the middle troposphere. This distribution far beyond isoprene emission zones indicates global-scale reactive nitrogen transport via PAN.

Quantitative estimates confirm long-range transport efficiency. With PAN lifetime ~2–4 weeks in the upper troposphere and characteristic subtropical jet stream transport velocities (~30 m s−1), transport distances reach 5000–10,000 km, comparable to intercontinental scales. ARCTAS and PAMARCMiP airborne campaigns documented episodes of elevated PAN concentrations (1–2 ppb) in the Arctic troposphere linked to mid-latitude transport [44].

The HTAP model ensemble estimated PAN’s contribution to intercontinental NOy transport at 20–40% in mid-latitudes [23]. Our results agree with these estimates: positive ozone anomalies in the high-latitude middle troposphere (+3–5 ppb) with virtually complete isoprene absence in these regions indicate transport of tropical emission influence via reservoir species.

Seasonal transport dynamics follow the biogenic emission cycle with characteristic time lag. Maximum PAN concentrations in the mid-latitude upper troposphere occur 1–2 months after tropical isoprene emission maxima, corresponding to characteristic convective vertical transport time and subsequent horizontal transport.

Differences in MPAN and PAN vertical distributions are explained by thermal stability differences. The MPAN decomposition rate constant at middle tropospheric temperatures (~250 K) is approximately an order of magnitude higher than for PAN [45], limiting MPAN vertical penetration and consequently its impact radius.

While we did not perform dedicated sensitivity experiments with artificially disabled transport (which would require substantial model modifications), the spatial patterns of reservoir species distributions (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10) provide clear evidence for the relative importance of transport versus local chemistry. The sharp latitudinal confinement of ISON and NALD (substantial concentrations only within 20° S–20° N) versus the hemispheric-scale distribution of PAN (significant concentrations at 60°+ latitude) demonstrates the transport scale hierarchy.

Quantitative estimates of transport contributions can be inferred from the vertical structure: in the tropical lower troposphere (0–5 km), where isoprene concentrations are maximum and PAN/MPAN form locally, the O3 response is dominated by local termination chemistry (10–15 ppb decrease). In contrast, the middle tropospheric O3 enhancement (+10–15 ppb at 8–12 km) occurs at altitudes where isoprene itself is absent (Figure 6), unambiguously indicating that this effect is transport-mediated rather than local. The high-latitude middle tropospheric O3 anomalies (+3–5 ppb at >60° latitude), occurring thousands of kilometers from isoprene emission sources, provide further evidence for long-range transport influence.

Future sensitivity studies could employ tagged tracers or artificial suppression of vertical transport to more rigorously partition local versus transport contributions, though the current results clearly demonstrate both mechanisms are quantitatively important.

4.3. Comparison with Observations and Other Models

The identified two-layer structure of isoprene’s impact on ozone is consistent with independent modeling studies that have explicitly evaluated isoprene effects. The SOCOL chemistry-climate model with MIM1 shows surface ozone reduction of 8–12 ppb in the tropics and increase of 10–12 ppb in the middle troposphere [26], quantitatively matching our results (10–15 ppb). The CMIP6 model ensemble median is 10 ± 5 ppb for positive middle tropospheric anomalies [46]. This agreement in the magnitude and spatial pattern of isoprene’s impact across different models provides confidence that the MIM1 mechanism reproduces key features of isoprene chemistry, though model-to-model variations in the precise magnitude of effects reflect differences in emissions, meteorology, and background chemical composition.

Intermodel comparison with CAMS, MERRA-2, and ERA5 reanalyses demonstrates improved atmospheric chemical composition simulation after MIM1 implementation. For carbon monoxide, tropical discrepancies with CAMS decrease from 20–30% (baseline version without isoprene) to 10–15% (version with MIM1). For hydroxyl radical, improvement is most significant: discrepancies decrease by factors of 2–3 at all altitudes, reflecting isoprene’s critical role in HOx radical balance in the tropics.

For ozone, improvement is selective and modest in magnitude: in the tropical lower troposphere (0–5 km, 20° S–20° N), overestimation decreases from 15–20 ppb to 5–10 ppb (a 50% reduction), though systematic positive bias persists. However, in the subtropical middle troposphere (5–12 km, 20–40°), ozone overestimation increases by 5–10 ppb, indicating that isoprene chemistry alone does not resolve all model biases and that uncertainties in NOx emissions, transport, and other chemical processes remain significant. This indicates the need for refinement of NOx chemistry representation in the transition zone between tropical and subtropical regimes.

Field observations confirm key mechanisms. The GoAmazon2014/5 campaign documented RO2 + HO2 to RO2 + NO reaction ratios of approximately 10:1 under low-NOx conditions over Amazonia [17], consistent with model estimates of termination reaction dominance. PAN measurements during the ARCTAS campaign showed concentrations of 1–2 ppb in the Arctic middle troposphere [44], quantitatively corresponding to model values of 3–5 × 1012 molecules cm−3 (~0.12–0.20 ppb at standard conditions).

Remaining observational discrepancies are partially attributable to model spatial resolution limitations (2° × 1.5° ≈ 150–200 km). Fine-scale NOx gradients near cities and emission hotspots are unresolved, leading to spatial averaging effects that can systematically bias simulated chemistry. Regional modeling studies [47] suggest that coarse resolution may underestimate subtropical O3 production by 10–20% due to nonlinear chemistry: averaging high-NOx (urban) and low-NOx (rural) conditions produces different ozone yields than simulating them separately. This “subgrid NOx gradient effect” likely contributes to our model’s overestimation in the subtropical middle troposphere (5–10 ppb, Figure 3).

Rigorous assessment of resolution impacts would require nested high-resolution simulations (e.g., 0.5° regional domains) or development of subgrid parameterizations that account for NOx-VOC nonlinearities, both of which are beyond the scope of this global implementation study. Regional models with ~10 km resolution show stronger localization of isoprene effects near emission sources and reduced spatial averaging artifacts [47], suggesting that future high-resolution global simulations may partially resolve current subtropical discrepancies.

Seasonal dynamics are qualitatively reproduced correctly: impact maxima follow biogenic emission maxima with characteristic interhemispheric shift. However, seasonal variation amplitude in the model is somewhat higher than observed, potentially related to using fixed emission fields without accounting for interannual variability.

4.4. Study Limitations and Prospects

This study implements only isoprene chemistry, the most abundant and reactive biogenic VOC (400–600 Tg C yr−1 [4,5]). However, monoterpenes (~100–150 Tg C yr−1) and anthropogenic VOCs also contribute significantly to tropospheric photochemistry. Isoprene was prioritized due to its emission dominance, highest reactivity (lifetime ~1–2 h vs. hours-days for terpenes [10]), and unique production of long-lived nitrogen reservoirs (PAN, MPAN) enabling intercontinental NOx transport [21,22,23]. Future INM-CM versions should include these additional VOC classes for comprehensive tropospheric chemistry representation, particularly for SOA formation and regional air quality applications.

The MIM1 mechanism does not include intramolecular peroxy radical isomerization via hydrogen atom transfer [48,49], which can increase OH yield by 20–40% in clean atmospheres [16]. More advanced mechanisms (MIM2, LIM1) include these processes and show better agreement with chamber experiments. Future comparison with detailed mechanisms including isomerization pathways would quantify simplification effects on predicted ozone, particularly in low-NOx tropical regions [48,49].

Using climatological emissions from year 2000 was justified by the experimental design to isolate the chemical mechanism impact. Satellite-derived trends in global isoprene emissions over 2000–2019 are <10% [37,38]—significantly smaller than typical inventory uncertainties of ±50–100% [4,5]. Thus, fixed emissions do not introduce substantial systematic errors for assessing mean chemical effects, though this limits reproduction of specific interannual anomalies such as El Niño-driven variations. Given emission uncertainties, our reported O3 changes (10–15 ppb) have a likely range of ±30–50%, though the qualitative two-layer structure and NOx-dependence are robust features confirmed by independent observations [17,18]. The 10-year averaging (2010–2019) encompasses various ENSO phases; statistical significance testing (p < 0.05, Figure 5) confirms robustness despite interannual variability. Future work with interactive emissions via MEGAN2.1 [4] will enable investigation of emission-climate feedbacks.

The study does not include aerosol interactions. Isoprene oxidation produces low-volatility compounds serving as secondary organic aerosol precursors (~70 Tg yr−1 [50]), which affect radiative balance and could modify climate forcing by 43% [51]. Isoprene-derived aerosols may also alter photolysis rates, creating negative feedbacks on ozone production. Coupling with aerosol and photolysis modules to quantify these chemistry-radiation feedbacks is planned for future versions.

Model spatial resolution (2° × 1.5° ≈ 150–200 km) limits representation of fine-scale NOx gradients near cities. Spatial averaging of high-NOx (urban) and low-NOx (rural) conditions produces different ozone yields than simulating them separately due to nonlinear chemistry, potentially underestimating subtropical O3 production by 10–20% [47]. Rigorous assessment would require nested high-resolution simulations, beyond this global implementation study’s scope.

Projected biogenic emission increases of 21–57% by 2100 under warming scenarios [11,12] amplify the importance of correct isoprene chemistry representation. Linear extrapolation suggests tropospheric ozone changes of +2–8 ppb in subtropics and −2–8 ppb in tropical lower troposphere by 2100, though nonlinear interactions with changing NOx, circulation, and humidity may substantially modify these estimates. Comprehensive assessment requires climate scenario calculations with interactive biogenic emissions.

5. Conclusions

Numerical experiments with the INM-CM climate model for 2010–2019 quantitatively confirmed the NOx-dependent two-layer vertical structure of isoprene’s influence on tropospheric ozone for the Russian climate model [15,16]. Implementation of the MIM1 isoprene oxidation mechanism reproduced ozone reduction of 10–15 ppb in the tropical surface layer (0–5 km) through peroxy radical termination reactions with HO2 and increase of 10–15 ppb in the middle troposphere (8–12 km) through thermal decomposition of vertically transported PAN and MPAN reservoirs [21]. These results quantitatively agree with independent SOCOL model estimates [26] and the CMIP6 ensemble median [46], confirming correct isoprene chemistry implementation in INM-CM.

Regional impact specificity, determined by nitrogen oxide concentrations, was reproduced consistently with observational data. In remote tropical forests with low NOx (<100 ppt), the model reproduces photochemical ozone formation suppression and atmospheric oxidizing capacity reduction (OH by 15–30%), agreeing with GoAmazon2014/5 [17] and OP3 [18,52] campaign measurements. In subtropics with moderate NOx (>500 ppt), the model shows ozone formation stimulation at all altitudes (+3–12 ppb), corresponding to field observations over anthropogenically influenced regions [20,53].

Analysis of isoprene oxidation product vertical distributions in INM-CM reproduced the established impact scale hierarchy: local (ISON, NALD in surface layer), regional (MPAN to 8 km), and global (PAN in middle troposphere to high latitudes) [45]. Model PAN distribution with maxima of 15–18 × 1012 molecules cm−3 at 8–12 km altitude and significant high-latitude concentrations agrees with ARCTAS airborne measurements [44] and confirms efficient intercontinental reactive nitrogen transport via biogenic reservoir species [23].

Intermodal comparison with CAMS, MERRA-2, ERA5 reanalyses and SOCOL demonstrates substantial tropospheric chemical composition simulation improvement after MIM1 implementation. Discrepancies with tropical carbon monoxide observations decrease from 20–30% to 10–15%. For hydroxyl radical, discrepancies decrease by factors of 2–3 at all altitudes. For ozone, tropical lower tropospheric concentration overestimation decreases from 30–40% to 10–15%. These improvements confirm that explicit isoprene chemistry representation is necessary for correct tropospheric atmospheric composition simulation in climate models [29,30].

The study’s main contribution is quantitative assessment of isoprene’s influence on tropospheric chemical composition as applied to the Russian Earth system model INM-CM. Isoprene was found to change ozone concentrations by 10–50% depending on region and altitude, carbon monoxide by 30–100% in the tropics, and hydroxyl radical by 15–30% in the low-latitude surface layer. These changes are comparable in magnitude to anthropogenic impacts and must be accounted for when using INM-CM for air quality assessment and climate projections [1,2].

Projected biogenic isoprene emission increases of 21–57% by the end of the 21st century due to climate warming [11,12] make the obtained results relevant for long-term climate projections. Correct reproduction of basic isoprene influence mechanisms in INM-CM provides a foundation for assessing future tropospheric chemical composition changes. Priority directions for future chemical module development include: (1) implementation of interactive biogenic emissions linked to prognostic meteorological fields [4]; (2) expansion to include monoterpene and anthropogenic VOC chemistry for comprehensive tropospheric photochemistry representation; (3) coupling with aerosol modules to represent secondary organic aerosol formation from VOC oxidation [50,51]; and (4) transition to more detailed isoprene oxidation mechanisms (MIM2, LIM1) accounting for peroxy radical isomerization [48,49]. These developments are essential for accounting climate-biogenic emission feedbacks and complete representation of biosphere-atmosphere interactions.

This study completes the first stage of non-methane VOC chemistry integration into the Russian Earth system model [31,32] and provides a scientific basis for further improvement of tropospheric photochemistry and biosphere-atmosphere interaction representation in the context of changing climate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; Methodology, A.O., M.T. and S.S.; Software, A.B. and S.S.; Validation, S.S.; Formal analysis, A.O., M.T. and S.S.; Investigation, A.O., M.T. and S.S.; Resources, S.S.; Data curation, A.O., M.T. and S.S.; Writing—original draft, A.O., M.T. and S.S.; Writing—review & editing, S.S.; Visualization, A.O. and M.T.; Supervision, A.B. and S.S.; Project administration, A.B. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grant no. 23-77-30008 from the Russian Science Foundation. A seamless mechanism for calculating chemical reaction rates in the troposphere and stratosphere was developed as part of a state task from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education to the Russian State Hydrometeorological University (project FSZU-2023-0002). The influence of stratospheric processes on the troposphere was studied as part of RSF project 24-17-00230.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Complete List of Chemical Species in INM-CM6.0

Table A1.

Chemical species in the INM-CM6.0 chemistry module. The model includes complete stratospheric chemistry (Ox, NOy, HOx, ClOx, BrOx families) and tropospheric chemistry with methane, carbon monoxide, and isoprene oxidation. Species added specifically for the MIM1 isoprene mechanism are highlighted in bold.

Table A1.

Chemical species in the INM-CM6.0 chemistry module. The model includes complete stratospheric chemistry (Ox, NOy, HOx, ClOx, BrOx families) and tropospheric chemistry with methane, carbon monoxide, and isoprene oxidation. Species added specifically for the MIM1 isoprene mechanism are highlighted in bold.

| Family | Species |

|---|---|

| Base chemistry (Pre-MIM1 Implementation) | |

| Oxygen Nitrogen Hydrogen Carbon Chlorine Bromine Halocarbons | O, O(1D), O3 N, NO, NO2, NO3, N2O, N2O5, HNO3, HO2NO2 H, OH, HO2, H2O, H2O2 CO, CO2, CH4, CH3O2, CH3OOH, H2CO Cl, Cl2, ClO, OClO, ClONO, Cl2O2, HCl, HOCl, ClONO2 Br, BrCl, BrO, HBr, HOBr, BrONO2 CCl4, CFCl3, CF2Cl2, CH3Cl, CH3CCl3, CHClF2, C2Cl3F3, C2Cl2F4, C2ClF5, CF2ClBr, CF3Br, CH3Br, C2H3FCl2 |

| MIM1 (This Study) | |

| Substrate Peroxy radicals Carbonyl products Hydroperoxides NOx reservoirs Acetyl species Other | C5H8 (isoprene) ISO2, MACRO2 MACR, HACET, MGLY ISO2H, MACRO2H PAN, MPAN, ISON, NALD CH3CO3, CH3CO3H, CH3COOH HCOOH (formic acid) |

Appendix B. Complete Chemical Mechanism with Rate Constants

Table A2.

The MIM1 isoprene oxidation mechanism implemented in INM-CM6.0 comprises 44 reactions (reactions 77–113 and 127–128 in the complete mechanism). Rate constants were updated from the original MIM1 formulation [33,34] using JPL recommendations where available [35]. Two-body rate constants are given as k = A × exp (−E/R × T), three-body rate constants follow the Troe formalism.

Table A2.

The MIM1 isoprene oxidation mechanism implemented in INM-CM6.0 comprises 44 reactions (reactions 77–113 and 127–128 in the complete mechanism). Rate constants were updated from the original MIM1 formulation [33,34] using JPL recommendations where available [35]. Two-body rate constants are given as k = A × exp (−E/R × T), three-body rate constants follow the Troe formalism.

| No. | Reagents | Products | A (cm3/(mol·c)) | E/R (K) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | O + O3 | O2 + O2 | 8.00 × 10−12 | 2060 | ||

| 2 | O(1D) + N2 | O + N2 | 2.15 × 10−11 | −110 | ||

| 3 | O(1D) + O2 | O + O2 | 3.30 × 10−11 | −55 | ||

| 4 | O(1D) + O3 | O2 + O2 | 1.20 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 5 | H2O + O(1D) | OH + OH | 1.63 × 10−10 | −60 | ||

| 6 | H2 + O(1D) | OH + H | 1.20 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 7 | CH4 + O(1D) | CH3 + OH | 1.31 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 8 | CH4 + O(1D) | H2 + H2CO | 0.09 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 9 | CH4 + O(1D) | H + CH3O | 0.35 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 10 | H + O3 | OH + O2 | 1.40 × 10−10 | 470 | ||

| 11 | H2 + OH | H2O + H | 2.80 × 10−12 | 1800 | ||

| 12 | OH + O3 | HO2 + O2 | 1.70 × 10−12 | 940 | ||

| 13 | OH + O | H + O2 | 1.80 × 10−11 | −180 | ||

| 14 | OH + OH | H2O + O | 1.80 × 10−12 | 0 | ||

| 15 | HO2 + O | OH + O2 | 3.00 × 10−11 | −200 | ||

| 16 | HO2 + O3 | OH + O2 | 1.00 × 10−14 | 490 | ||

| 17 | H + HO2 | OH + OH | 7.20 × 10−11 | 0 | ||

| 18 | H + HO2 | H2 + O2 | 6.90 × 10−12 | 0 | ||

| 19 | H + HO2 | H2O + O | 1.60 × 10−12 | 0 | ||

| 20 | OH + HO2 | H2O + O2 | 4.80 × 10−11 | −250 | ||

| 21 | HO2 + HO2 | H2O2 + O2 | 3.00 × 10−13 | −460 | ||

| 22 | HO2 + HO2 | H2O2 + O2 | 2.10 × 10−33 | −920 | ||

| 23 | OH + H2O2 | H2O + HO2 | 1.80 × 10−12 | 0 | ||

| 24 | O + H2O2 | OH + HO2 | 1.40 × 10−12 | 2000 | ||

| 25 | NO + O3 | NO2 + O2 | 3.00 × 10−12 | 1500 | ||

| 26 | NO + HO2 | OH + NO2 | 3.30 × 10−12 | −270 | ||

| 27 | NO2 + O | NO + O2 | 5.10 × 10−12 | −210 | ||

| 28 | NO2 + O3 | NO3 + O2 | 1.20 × 10−13 | 2450 | ||

| 29 | NO3 + O | O2 + NO2 | 1.00 × 10−11 | 0 | ||

| 30 | NO + NO3 | NO2 + NO2 | 1.50 × 10−11 | −170 | ||

| 31 | HNO3 + OH | NO3 + H2O | 2.40 × 10−14 | −460 | ||

| 32 | OH + HO2NO2 | H2O + NO2 | 1.30 × 10−12 | −380 | ||

| 33 | N + O2 | NO + O | 1.50 × 10−11 | 3600 | ||

| 34 | N + NO | N2 + O | 2.10 × 10−11 | −100 | ||

| 35 | N + NO2 | N2O + O | 5.80 × 10−12 | −220 | ||

| 36 | N2O + O(1D) | NO + NO | 7.25 × 10−11 | −20 | ||

| 37 | N2O + O(1D) | N2 + O2 | 4.63 × 10−11 | −20 | ||

| 38 | CL + O3 | CLO + O2 | 2.30 × 10−11 | 200 | ||

| 39 | CL + H2 | HCL + H | 3.05 × 10−11 | 2270 | ||

| 40 | CL + HO2 | HCL + O2 | 1.40 × 10−11 | −270 | ||

| 41 | CL + HO2 | OH + CLO | 3.60 × 10−11 | 375 | ||

| 42 | CL + H2O2 | HCL + HO2 | 1.10 × 10−11 | 980 | ||

| 43 | CLO + O | CL + O2 | 2.80 × 10−11 | −85 | ||

| 44 | CLO + OH | CL + HO2 | 7.40 × 10−12 | −270 | ||

| 45 | CLO + OH | HCL + O2 | 6.00 × 10−13 | −230 | ||

| 46 | CLO + HO2 | HOCL + O2 | 2.60 × 10−12 | −290 | ||

| 47 | CLO + NO | CL + NO2 | 6.40 × 10−12 | −290 | ||

| 48 | CLO + CLO | CL + OCLO | 3.50 × 10−13 | 1370 | ||

| 49 | CLO + CLO | CL + CLOO | 3.00 × 10−11 | 2450 | ||

| 50 | CLO + CLO | CL2 + O2 | 1.00 × 10−12 | 1590 | ||

| 51 | HCL + OH | CL + H2O | 1.80 × 10−12 | 250 | ||

| 52 | HOCL + OH | H2O + CLO | 3.00 × 10−12 | 500 | ||

| 53 | O + CLONO2 | CLO + NO3 | 3.60 × 10−12 | 840 | ||

| 54 | OH + CLONO2 | HOCL + NO3 | 1.20 × 10−12 | 330 | ||

| 55 | CLONO2 + CL | CL2 + NO3 | 6.50 × 10−12 | −135 | ||

| 56 | CCL4 + O(1D) | CL + CL | 3.30 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 57 | C2H3FCL2 + O(1D) | CL + CL | 2.60 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 58 | O(1D) + CHCLF2 | CL + products | 1.00 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 59 | O(1D) + CF2CL2 | CLO + CL | 1.40 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 60 | O(1D) + CFCL3 | CLO + CL | 2.30 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 61 | O(1D) + C2CL3F3 | CL + CL | 2.00 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 62 | O(1D) + C2CL2F4 | CL + CL | 1.30 × 10−10 | 0 | ||

| 63 | O(1D) + C2CLF5 | CL + products | 5.00 × 10−11 | 0 | ||

| 64 | OH + CH3CCL3 | CL + CL | 1.64 × 10−12 | 1520 | ||

| 65 | CHCLF2 + OH | CL + H2O | 1.05 × 10−12 | 1600 | ||

| 66 | OH + CH3CL | H2O + CL | 2.40 × 10−12 | 1250 | ||

| 67 | CO + OH | CO2 + H | 1.50 × 10−13 | 0 | ||

| 68 | CH4 + OH | CH3 + H2O | 2.45 × 10−12 | 1775 | ||