Abstract

This paper presents test results of the performance comparison of 5G standalone (SA) and non-standalone (NSA) networks in the context of gathering data of remote sensors and machines. The study evaluates key network characteristics such as latency, throughput, jitter and packet loss (for UDP protocol only) using standardized tests to gain insights into the impact of these factors on real-time and data-intensive communication. In addition, a range of communication protocols including OPC UA, Modbus, MQTT, AMQP, CoAP, EtherCAT and gRPC were tested to assess their efficiency, scalability and suitability with different send data sizes. By conducting experiments in a controlled hardware environment, we have analyzed the impact of the 5G architecture on protocol behavior and measured the transmission performance at different data sizes and connection configurations. Particular attention is paid to protocol overhead, data transfer rates and responsiveness, which are crucial for industrial automation and IoT deployments. The results show that SA networks consistently offer lower latency and more stable performance, where robust and low-latency data transfer is essential. In contrast, lightweight IoT protocols such as MQTT and CoAP demonstrate reliable operation in both SA and NSA environments due to their low overhead and adaptability. These insights are equally important for time-critical industrial protocols such as EtherCAT and OPC UA, where stability and responsiveness are crucial for automation and control. The study highlights current limitations of 5G networks in supporting both remote sensing and industrial use cases, while providing guidance for selecting the most suitable communication protocols depending on network infrastructure and application requirements. Moreover, the results indicate directions for configuring and optimizing future 5G networks to better meet the demands of remote sensing systems and Industry 4.0 environments.

1. Introduction

The advent of 5G technology has opened new horizons for wireless data transfer, offering enhanced privacy, improved security, reduced latency and significantly higher throughput [1]. As diverse research domains and industrial sectors increasingly depend on wirelessly connected sensors, systems, machines and other components, the need for trusted and resilient wireless communication has become paramount. Both 5G network topologies—standalone (SA) and non-standalone (NSA) configurations—are expected to serve as the backbone of this digital transformation, enabling seamless data exchange across industrial processes and smart devices [2].

Beyond industrial automation, next-generation wireless networks are tightly linked with the broader field of remote sensing and unmanned systems. Emerging paradigms such as flying ad hoc networks (FANETs) demonstrate how UAVs can act as mobile communication nodes, extending coverage and enabling integration with 5G/6G networks [3]. Reliable communication also underpins real-time kinematic (RTK) positioning, where wireless transmission delays and synchronization challenges remain critical to ensuring high-precision navigation in autonomous driving, UAVs and smart robotics [4]. In parallel, aerial remote sensing platforms coupled with real-time satellite communication have shown the necessity of robust, low-latency data transfer for emergency response scenarios, where the rapid relay of large volumes of sensor data is essential [5]. Moreover, the fusion of remote sensing technologies with AI-based monitoring solutions—ranging from road infrastructure management to natural disaster assessment—underscores the importance of scalable, high-bandwidth communication infrastructures [6]. Taken together, these advances highlight that 5G SA and NSA networks are not only enablers of industrial IoT protocols but also critical elements in the integration of sensing, positioning and emergency communication systems.

A crucial aspect of this change is the performance of the various communication protocols. Traditional protocols like OPC Unified Architecture (OPC UA) and Modbus are well-established for handling automation tasks [7]. However, newer IoT-focused protocols such as Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP) and Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) provide lightweight alternatives optimized for low-power devices with limited capabilities [8]. Protocols such as EtherCAT are essential for real-time control systems where precision and minimal jitter are critical [9]. With the increasing complexity of networked systems, the need for robust, scalable and efficient communication is becoming more urgent [10]. In the next paragraphs, the literature review focuses on crucial areas such as 5G networks, industrial communication protocols, IoT communication protocols, High-Bandwidth Communication Protocols and Industrial and IoT Communication Protocol Performance in 5G Networks.

1.1. Contributions of This Work

Unlike many existing 5G performance studies that focus primarily on generic throughput metrics or consumer-oriented downlink performance, this work provides a protocol-level comparative analysis of both real-time industrial communication protocols (EtherCAT and OPC UA) and lightweight IoT protocols (MQTT, AMQP, CoAP and gRPC) under identical 5G SA and NSA network conditions. A key distinguishing aspect of this study is its explicit focus on uplink performance, which is critical for industrial automation, distributed sensing and machine-to-machine communication, yet remains underrepresented in the 5G literature. Furthermore, by relating protocol-specific throughput to iPerf3 baseline measurements, the study quantifies protocol efficiency relative to the available 5G uplink capacity, providing practical insights for protocol selection in industrial and IIoT deployments.

1.2. 5G Networks (SA vs. NSA Architecture)

The 5G standalone (SA) and non-standalone (NSA) architectures differ significantly in key performance areas. SA, with its independent 5G core, offers lower latency compared to NSA, which relies on the 4G core and therefore has higher latency. In terms of throughput, SA enables higher data speeds by fully utilizing 5G capabilities, while NSA is limited by its reliance on the 4G core. Reliability is also stronger in SA, thanks to advanced features such as network slicing and Network Function Virtualization (NFV), which are ideal for critical applications; reliability in SA is also higher. However, these features are standardized but not yet widely deployed in current commercial and private networks. NSA offers less consistent performance with its hybrid 4G/5G infrastructure. In addition, SA is more scalable and supports a larger number of IoT devices and various applications with better resource management, while NSA struggles to meet these requirements due to its 4G limitations. Researchers pointed to a gap in understanding the potential of SA in industrial IoT and machine-to-machine communications, where low latency and high reliability are crucial. While NSA is widely researched, it is recognized to have limitations in terms of scalability and latency that could hinder future industrial deployment [11,12,13].

From an architectural perspective, the primary distinction between 5G NSA and SA lies in the handling of the control and user planes. In NSA deployments, control plane signaling is located in the LTE Evolved Packet Core (EPC), while user plane data is transmitted over 5G. This hybrid operation introduces additional signaling steps and interfaces between LTE and 5G, which increase end-to-end latency and jitter, particularly for uplink communication. In contrast, 5G SA utilizes a native 5G Core (5GC) for both control and user planes, enabling more direct routing, reduced signaling overhead and improved stability. These architectural differences are especially relevant for industrial and IIoT applications, where data is predominantly generated at the network edge and transmitted upstream toward controllers, edge servers, or cloud platforms. While advanced 5G features such as network slicing and ultra-reliable low-latency communication (URLLC) are conceptually associated with SA deployments, their practical availability remains limited in current networks. Even without full URLLC support, the SA architecture offers benefits for latency-sensitive and uplink-oriented communication needs [11,14].

1.3. Industrial Communication Protocols Overview

In industrial applications, the use of Ethernet-based communication protocols is widespread, with Modbus, EtherCAT and OPC UA being the fundamental protocols driving industrial digitization and connectivity, especially in real-time applications. EtherCAT is indispensable for industrial digitalization and real-time connectivity. Its unique summation frame method enables fast, on-the-fly data processing that offers low latency and high efficiency. This makes EtherCAT ideal for time-critical applications such as motion control, and outperforms other protocols such as Modbus and OPC UA in ensuring precise real-time communication [15].

As the backbone of industrial communication, they enable the smooth exchange of data between machines and systems. However, their suitability for time-critical and business-critical processes varies. Modbus (TCP version) does not have built-in security features despite its widespread use. While secure versions exist, they often require robust channels to ensure message delivery and prevent attacks such as message tampering, which limits their effectiveness in critical real-time environments. This is mainly because it was developed in 1999, and not much has been done to improve it. On the other hand, OPC UA, which has security at its core, offers robust features such as message signing and encryption (Sign and SignAndEncrypt modes). This makes it much more suitable for business-critical real-time applications that require a high level of data integrity and authenticity. Nevertheless, problems can occur with OPC UA, such as sequence number overflows, that must be carefully managed to avoid disruption [16].

1.4. IoT Communication Protocols

In the context of IoT applications, MQTT, AMQP and CoAP are key protocols designed for the lightweight communication requirements of resource-constrained devices. Each protocol offers distinct advantages for seamless data exchange between a range of IoT devices while minimizing resource consumption.

MQTT is widely recognized for its simplicity and efficiency, especially in environments with limited bandwidth and processing power. MQTT uses a publish-subscribe model that reduces overhead by transmitting only the necessary messages between clients and servers. Its minimal footprint makes it ideal for scenarios such as smart homes and portable devices [17,18]. However, security remains a problem with MQTT, especially in mission-critical environments. Although encryption and authentication can be layered on top of the protocol, this can increase the cost of data processing [17].

AMQP is another major player in the IoT and has been developed to provide more comprehensive features such as message queuing and delivery guarantees. AMQP is favored for its ability to guarantee message delivery in unreliable networks and support multiple QoS (Quality of Service) levels, making it suitable for applications that require high reliability, such as industrial IoT and smart grid systems. Recent studies show that AMQP, especially when combined with newer transport protocols such as QUIC, can achieve lower latency and better performance in high-packet-loss scenarios, making it a strong candidate for IoT communication over lossy networks [15,19].

CoAP is tailored to very lightweight devices and works over UDP to offer a simple, REST-based communication model like HTTP. The design of CoAP is extremely efficient for constrained devices such as sensors as it minimizes the amount of data transferred. CoAP’s message structure supports both reliable and unreliable transmission modes, allowing flexibility in scenarios where data transmission must be guaranteed or where low overhead is a priority [15,19].

While these protocols excel in certain areas, there is a noticeable gap in comprehensive experiments testing their performance in 5G networks. Evaluating MQTT, AMQP and CoAP in 5G environments would provide valuable insights into how these protocols address the challenges of high-speed, low-latency communications, especially in mission-critical applications where reliability and speed are paramount. Such experiments are crucial to understanding how these protocols can be optimized for the next generation of IoT connectivity.

1.5. High-Bandwidth Communication Protocols Overview

High-bandwidth communication protocols such as google Remote Procedure Call (gRPC) are essential for processing high data throughput, especially in advanced network infrastructures such as 5G. HTTP/2’s multiplexing, stream prioritization and resource saving features are critical for optimizing data-intensive applications such as 360-degree video streaming, where smooth and efficient data transmission is required even under fluctuating network conditions [20,21]. Similarly, gRPC, with its efficient binary serialization and low-latency design, is increasingly used in distributed systems that require real-time communication and high throughput [20].

Testing these protocols over 5G networks, especially in standalone (SA) and non-standalone (NSA) configurations, is crucial to evaluating their performance in high-speed, low-latency environments. As 5G promises to support ultra-reliable low-latency communications (URLLC), testing gRPC in 5G SA and NSA scenarios will provide insights into its ability to handle mission-critical applications and IoT data processing in real-time. Such experiments are important to validate the efficiency of these protocols under the dynamic and demanding conditions of 5G networks.

1.6. Communication Protocol Performance in 5G Networks

This study is focused on the use of 5G in NSA and SA networks and its impact on network latency and throughput. Several studies report improved performance in 5G standalone configurations compared to non-standalone deployments [22]. Protocols such as MQTT, AMQP and CoAP are particularly effective in NSA environments for lightweight applications, but their performance needs to be tested under full 5G SA to meet ultra-reliable low latency communication (uRLLC) standards [23]. Latency and packet loss are especially critical for time-critical applications such as industrial automation and robotics. A study of 5G-enabled smart cities has shown that while 5G can support high-throughput applications such as video streaming, there are performance variations due to environmental and geographical factors [22]. These variations impact how protocols perform under different network loads. Standard tools such as Ping and iPerf3 (version 3.20, ESnet, Berkeley, CA, USA) are crucial for understanding network performance. Ping provides important latency measurements, while iPerf3 measures throughput, jitter and packet loss. Together, these tools offer a comprehensive assessment of the performance of protocols in different 5G configurations [14,24].

In summary, although individual studies offer valuable insights, further research is needed on protocol performance in 5G SA and NSA environments to ensure their reliability for industrial applications. Therefore, in this paper, we evaluated the performance of a wide range of industrial and IoT protocols, including Modbus, EtherCAT, OPC UA, MQTT, AMQP, CoAP and gRPC, when deployed over 5G SA and NSA networks. Benchmarking these protocols in terms of latency, throughput and discussion on scalability will enable a comprehensive comparison that takes into account the key performance metrics for industrial and IoT applications. The results will shed light on how different 5G architectures affect protocol behavior and provide guidance to industry in selecting the most suitable communication technologies for their specific requirements.

2. Related Work

Recent research on 5G networks has primarily focused on architectural and radio-level performance differences between standalone (SA) and non-standalone (NSA) deployments. Several studies report that SA provides lower latency, improves stability and better supports latency-sensitive services because of its native 5G core and simplified control and user plane architecture [11,12,14]. However, these works mainly concentrate on general network indicators such as latency and quality of experience, and therefore do not analyze how application-layer communication protocols behave over SA and NSA networks.

Measurement-oriented studies using Ping and iPerf have been widely adopted to characterize 5G performance in terms of latency, throughput, jitter and packet loss [22,24,25]. These tools provide important baseline figures for network capacity, yet they do not quantify protocol overhead or relate application-level performance to the available uplink bandwidth, which is crucial for industrial and IoT data flows.

There is a real-world comparison of private 5G SA and public 5G NSA, which investigated ultra-low latency Networked Music Performance (NMP) over both architectures (SA and NSA). Using real-time UDP audio streams, it showed that a private SA network with edge computing can achieve stable latencies around 22 ms with packet loss below 1%, whereas a public NSA network exhibits substantially higher latency (35–70 ms) and frequent packet-loss bursts, making it unsuitable for time-critical applications. While this work provides one of the most detailed experimental SA versus NSA evaluations in a real-time uplink dominated scenario, it is limited to a single UDP-based audio stream and does not evaluate industrial or IoT communication protocols or their efficiency relative to the available 5G uplink capacity [13].

In parallel, a large body of literature investigates IoT protocols such as MQTT, AMQP and CoAP with respect to scalability, reliability and security [8,15,18,19,20]. Similarly, industrial communication protocols such as OPC UA and EtherCAT have been studied for determinism, robustness and integration into Industry 4.0 environments [9,16]. However, these works are typically conducted over wired networks or generic wireless links, and do not consider the differences between 5G SA and NSA architectures, nor do they provide a quantitative comparison against the achievable 5G uplink throughput.

Overall, despite extensive research on 5G network performance, IoT protocols and industrial communication, there remains a lack of a unified experimental framework that evaluates multiple industrial and IoT protocols over both 5G SA and NSA networks, with a specific focus on uplink behavior, UDP reliability, and protocol efficiency relative to the available 5G capacity. This gap is addressed by the present study and is shown in comparison Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of related work on 5G SA and NSA networks for industrial and IoT communications.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Network and Hardware Setup

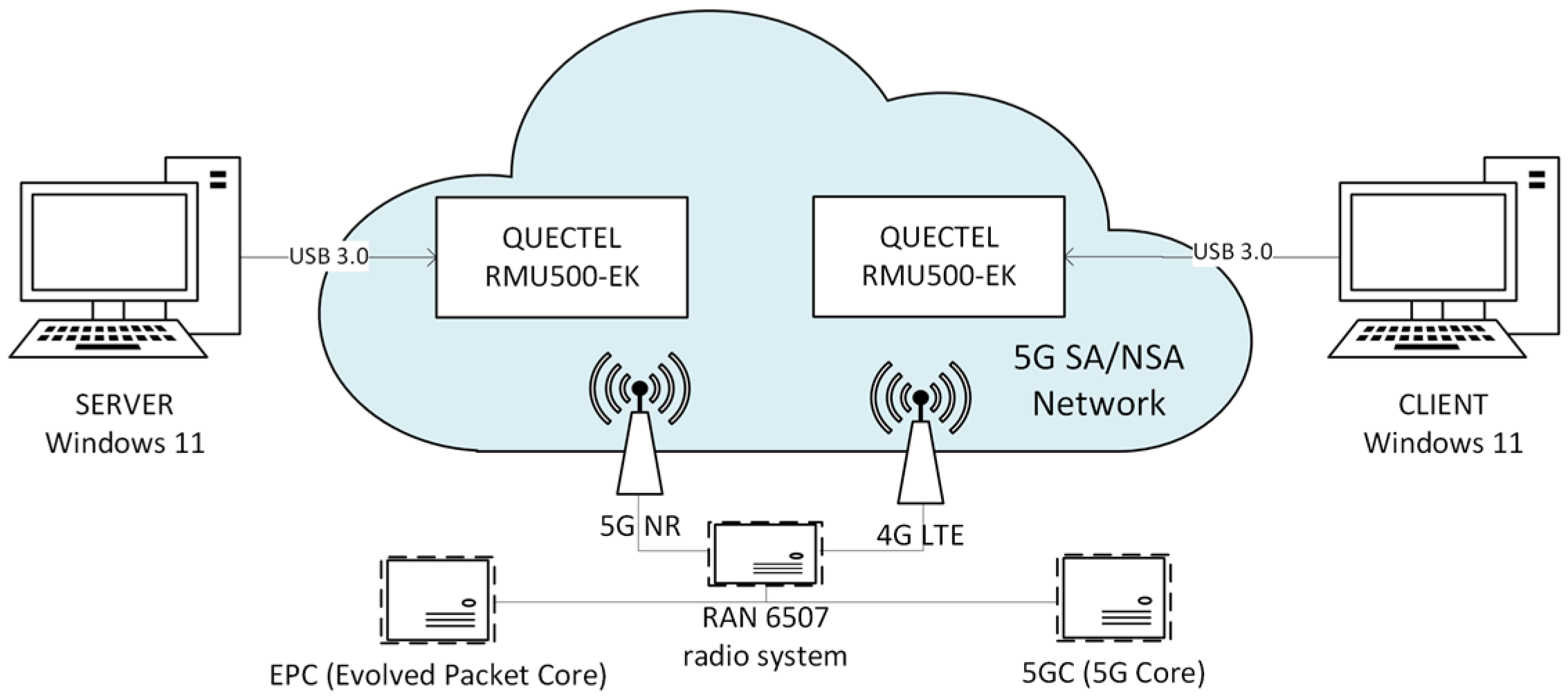

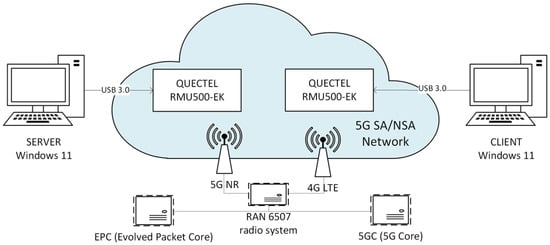

The hardware has been set up so that all tests can be carried out using the same 5G hardware. The server and client with Windows operating system installed, suitable Python (version 3.13, Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) libraries for testing different communication protocols and test programs, are connected to individual RMU500-EK (Quectel, Shanghai, China) 5G modems via USB 3.0. Both 5G modems have installed M2M MultiSIM (Telekom Slovenije, Ljubljana, Slovenia) cards and are set up so that they have a static IP in the 5G SA and NSA network and can be pinged from each other (Figure 1). This setup provides a robust and reproducible environment for evaluating network performance and protocol-specific behavior under consistent 5G network conditions.

Figure 1.

5G network with an integrated server and client connected to a RMU500-EK 5G modem.

We used the QUECTEL RMU500-EK 5G modem connected to a PC for testing, using its USB plug-and-play setup for easy integration without additional configuration. Based on the features listed below, the modem is suitable for our industrial testing on the 5G network.

Key specifications of the modem:

- ▪

- 5G NSA and SA support: Flexible for both non-standalone and standalone 5G tests.

- ▪

- High throughput: Up to 4.5 Gbps download and 2.5 Gbps upload speeds, ideal for high-bandwidth tasks.

- ▪

- USB 3.1 Interface: Fast, stable data transfer for industrial and IoT use.

- ▪

- Low latency: Critical for real-time, mission-critical applications.

- ▪

- MIMO technology: Ensures better signal quality and reliability.

3.1.1. Non-Standalone (NSA) Mode Network Hardware

The installed 5G public network, set up by a national telecommunications operator, Telekom Slovenije d.d., utilizes the 3.5 GHz frequency band (N78) with the following equipment:

- ▪

- ERRICSSON RAN 6507 radio system (Ericsson, Stockholm, Sweden).

- ▪

- ERRICSSON 5G-network cell (Ericsson, Stockholm, Sweden).

- ▪

- ERRICSSON 4G-network cell (Ericsson, Stockholm, Sweden).

The measured signal strength of the two 5G modems was 77 and 79 dBm, which means that the signal strength was excellent.

3.1.2. Non-Standalone (NSA) Mode Network

The standalone 5G network was private, meaning that the number of users on the network and data traffic were limited and not affected by the population using the network. The public network, on the other hand, is more robust and can generally handle larger data transmission loads. The private SA network was also set up by a national telecommunications operator Telekom Slovenije d.d. and also uses the 3.5 GHz frequency band (N78) with the following equipment:

- ▪

- ERRICSSON RAN 6507 radio system (Ericsson, Stockholm, Sweden).

- ▪

- ERRICSSON 5G-network cell (Ericsson, Stockholm, Sweden).

The main difference was that 5G SA uses a private core network that manages connectivity, mobility, authentication and data routing between private devices. This was also done to test the benefits of using private networks for industrial use compared to using public networks, and to identify which features need to be changed to provide a better 5G network for industrial use. The measured signal strength of the two 5G modems was 79 and 81 dBm, which means that the signal strength was good to excellent.

3.2. Protocols and Measurement Metrics

Based on the literature research and the most commonly used communication protocols, we decided to first perform tests to determine the latency and throughput of 5G SA and NSA using the standard test tools, Ping and iPerf3 (Tests 1 and 2). The tests of the communication protocols were then carried out, with all tests listed in Table 2 from 3 to 9. In most cases, the server and client used the same Python (version 3.13, Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) libraries. Exceptions are noted where this was not possible.

Table 2.

Tests and used protocols and corresponding python libraries or software.

A Ping latency test (Test 1) measures how long a data packet takes to get to a target device and back, known as the Round-Trip Time (RTT), shown as response time in Section 4. The Ping command was used for this, and the results are given in milliseconds (ms). Low latency means faster response times on the network, which is important for real-time applications such as games and video calls.

The iPerf3 test (Test 2—Similar tests with iPerf3 were performed in non-public 5G networks and are used for comparison [25]), which shows the maximum throughput of a network between a server and a client, was performed five times to calculate the throughput in bps (bytes per second) by varying the following parameters:

- ▪

- Duration: The entire test period lasted 60 s, while measurement of throughput time was performed every second.

- ▪

- Protocol: TCP and UDP (iPerf3 with constant-bit-rate traffic to evaluate packet loss under increasing network load).

- ▪

- Parallel streams: 1–10,12,16, 20, 24.

The selected payload size and scaling strategy were designed to reflect representative data exchange patterns in industrial automation and IoT systems. In typical machine-to-machine and IoT communication, the transmitted data includes binary status signals, numerical sensor values such as temperature, pressure or torque, structured messages (e.g., JSON-formatted telemetry) and aggregated datasets generated by machines or edge devices. A base variable size of 1024 bytes allows the representation of both compact control information and structured process data, while the gradual increase in the number of transmitted variables emulates realistic scenarios ranging from periodic sensor updates to larger batched or aggregated transmissions. The upper payload limit corresponds to the largest data packets commonly encountered in industrial communication outside of continuous media streaming, enabling evaluation of protocol scalability and network behavior under increasing data volumes.

The test of the communication protocols (tests 3–9) was performed with the following parameters and measurements.

- ▪

- Size of each variable sent from the client to the server: 1024 bytes.

- ▪

- Increasing the number of variables sent from 1 to 250 with an increment of 1. This means that the data sent is 1024 bytes for the first iteration and 256,000 bytes for the 250th. If during the test, the time to send data was larger than 50 s, the test was stopped.

- ▪

- The tests continued to 500 sent variables if the results of the first 250 variables were under 5 s, stable and without data loss.

- ▪

- The metrics for the individual communication protocols were determined on the basis of latency and throughput measurements.

Latency measurement represents the time it takes for data to be sent from the server and for a confirmation message to be received, indicating that the data was successfully transmitted. This process is illustrated in the following Equation (1). Latency is calculated as the total round-trip delay for data transactions based on the standards ITU-T G.114 [26] and ISO/IEC 7498-1 [27].

where L is the total latency (in seconds), Lwrite,i is the latency for writing the i-th chunk of data, Lread,i is the latency for reading the i-th chunk of data and n is the total number of chunks. Throughput is calculated by using Equation (2).

where T is the throughput (in bits per second), D is the total amount of data transmitted (in bytes), the factor 8 converts bytes to bits and L is the total latency (in milliseconds). Throughput is measured in bits per second (bps) and follows the data transmission guidelines in standards RFC 6349 [28] and ISO/IEC 15802-3 [29]. Each test related to the communication protocols was performed 10 independent times to obtain statistically representative results. Tests 3–9 results will be shown as a single representative run to illustrate temporal behavior and variability, while all reported average upload speeds and quantitative comparisons are computed from the full set of repeated measurements. However, when presenting the visual results, we decided to show the graph of a single test to illustrate the data noise in practice, as this is important to notice and visualize.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Basic Performance on NSA and SA Network

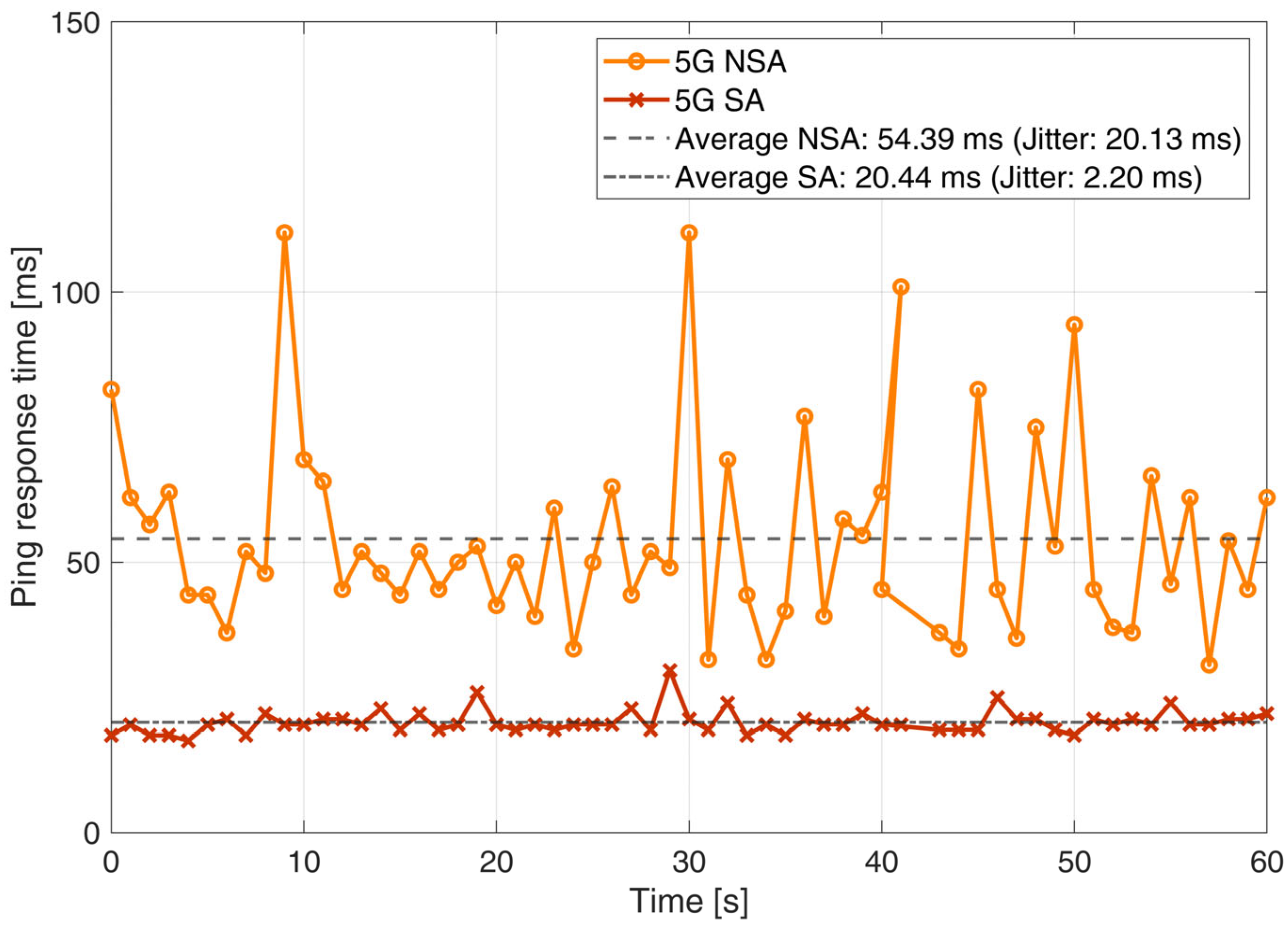

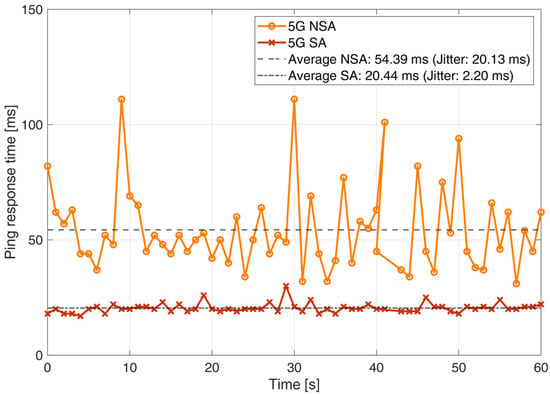

As described in the methodology, we first performed Ping (Test 1) and iPerf 3 (Test 2) tests to determine the latency difference between the public NSA and the private SA network. In Figure 2, the result clearly shows the difference between the public 5G NSA and the private 5G SA network. The time it takes for the signal to reach and return to the target device is, on average, 54.39 ms for 5G NSA and 20.44 ms for the SA network. This is an enormous difference (more than 250%), which can play a decisive role if one technology is to be preferred over the other. Jitter is also almost 10 times higher in 5G NSA mode, and spikes occasionally occur with a delay of more than 50 ms between the median and the spike value. When performing Ping tests on Google servers, the Ping time was typically 40% of the measured time when testing the Ping between IoT devices. This indicates that intra-network latency is more affected by the NSA and SA architecture than uplink/downlink interactions with cloud-based endpoints.

Figure 2.

Round-trip latency (Ping RTT) measured between two IoT devices over 5G SA and 5G NSA networks.

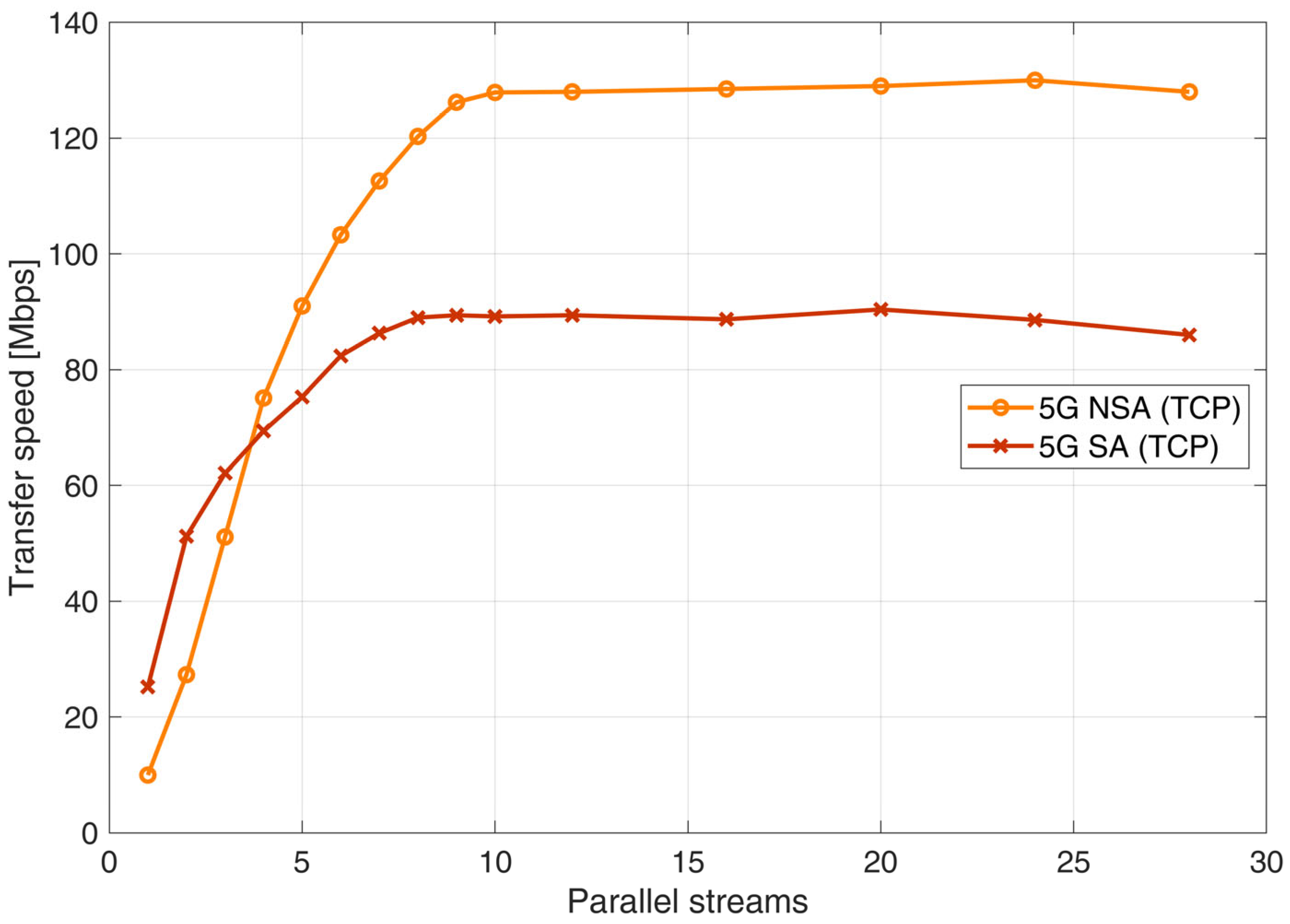

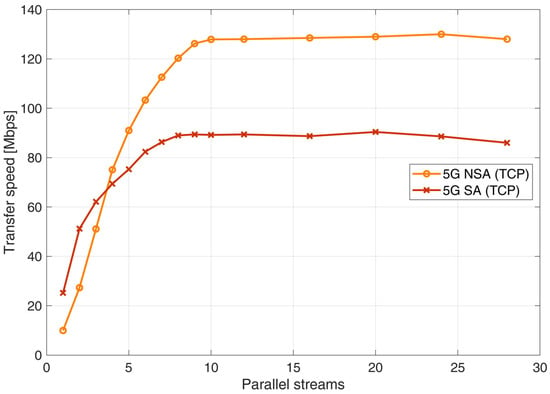

The second test (iPerf3) was performed to determine the maximum possible transmission bandwidth between two IoT or IIoT devices. We tested the TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) that ensures reliable delivery, and the UDP (User Datagram Protocol) that is more prone to data loss. Here, we do not test the data exchange between the IoT device and the cloud services, as we know that in both cases, the download speed is around 1000 Mbps and the upload speed is 100 Mbps (the 10:1 ratio for download speed is standard for telephone networks, as the majority of users are downloading content, not sending it). The results in Figure 3 show two important findings.

Figure 3.

Maximum achievable uplink throughput measured using iPerf3 in 5G NSA and 5G SA networks.

The first point is that the maximum bandwidth of the public 5G NSA network is 130 Mbps, while that of the 5G SA network is 90 Mbps. The observed difference reflects the architectural characteristics of NSA and SA deployments, as described in Section 1.2. In the future, as higher frequencies are adopted and the 5G core is optimized—particularly improving the download-to-upload ratio from the current 10:1 toward the 1:1 ratio needed for industrial applications—overall bandwidth is expected to increase. However, NSA may still remain slightly faster due to its dual-channel design.

Another important finding is that the upload speed correlates with the number of parallel streams used in the data transfer. After using 10 parallel streams, the maximum bandwidth is reached. This is also a specific setting of the mobile network that needs to be changed in the future (based on multiple apps uploading and downloading data), as this blocks the full potential of the 5G network when using a specific communication protocol, and only the maximum bandwidth of a single stream can be achieved (as shown in the following sections).

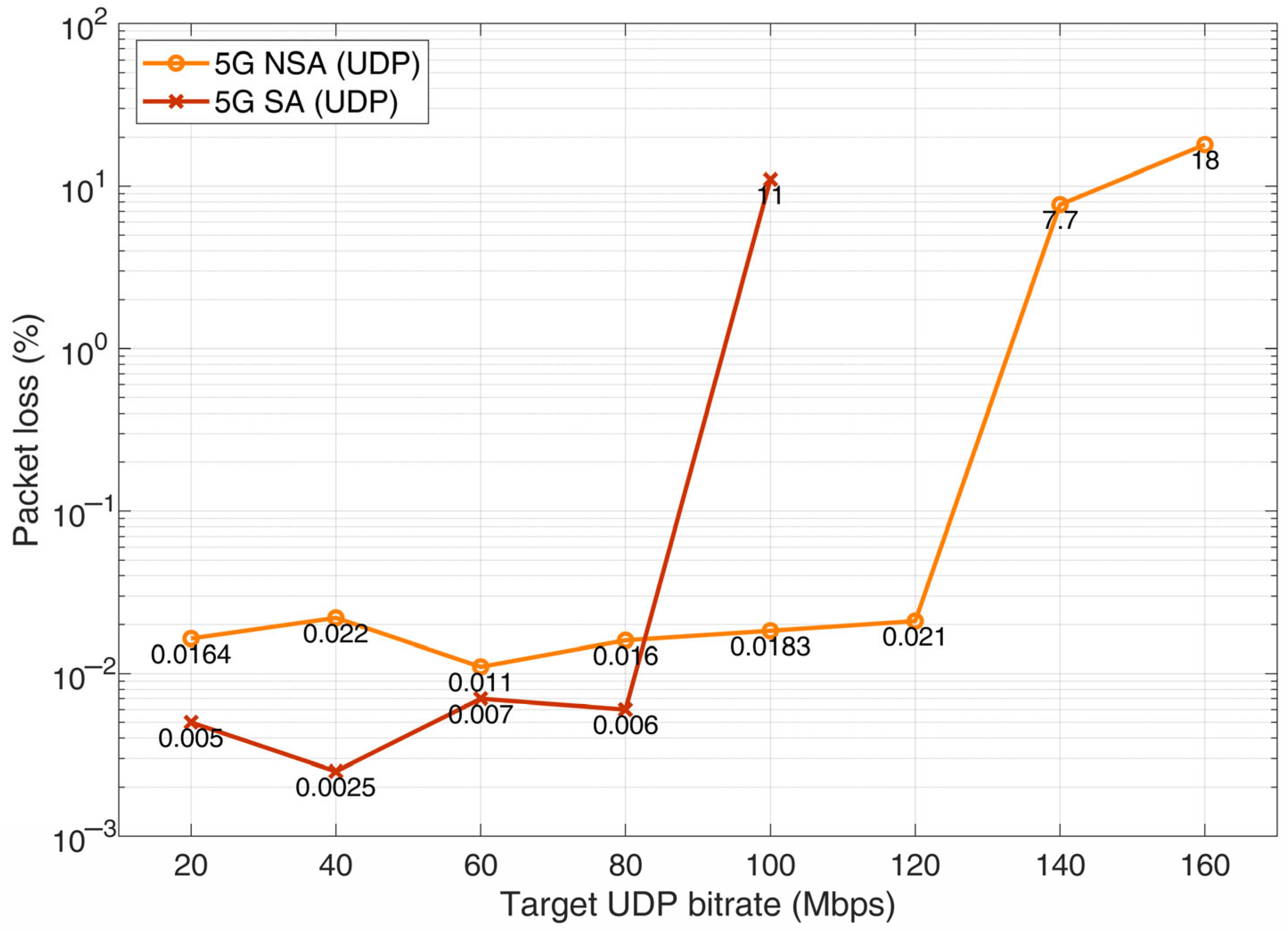

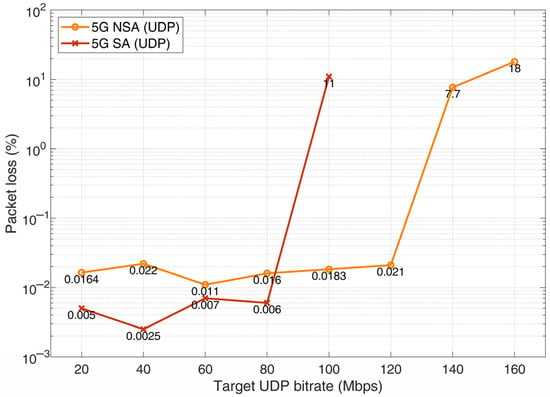

In addition to TCP throughput measurements, UDP packet loss was evaluated to assess network behavior under increasing uplink load (Figure 4) where each test was performed for 5 min. UDP tests were performed using iPerf3 by progressively increasing the target bitrate until network saturation was reached. Figure 4 shows the measured packet loss for 5G NSA and 5G SA configurations as a function of the target UDP bitrate.

Figure 4.

DP packet loss versus target uplink bitrate for 5G NSA and 5G SA networks. The logarithmic packet-loss axis highlights the low-loss region and the sharp increase in losses near network saturation.

At low and moderate bitrates (20–120 Mbps), both architectures exhibit very low packet loss (<0.03%), indicating stable uplink operation. However, once the offered load approaches the effective uplink capacity, a sharp increase in packet loss is observed. In the public 5G NSA network, packet loss rises abruptly beyond 140 Mbps, reaching 7.7% at 140 Mbps and 18% at 160 Mbps. In contrast, the private 5G SA network maintains extremely low loss up to 80 Mbps, followed by a sudden increase to 11% at 100 Mbps.

This behavior highlights the threshold-based nature of UDP performance in 5G networks and confirms that while SA provides superior reliability at low and moderate loads, both architectures experience rapid degradation once network capacity is exceeded.

4.2. Industrial Communication Protocols Results

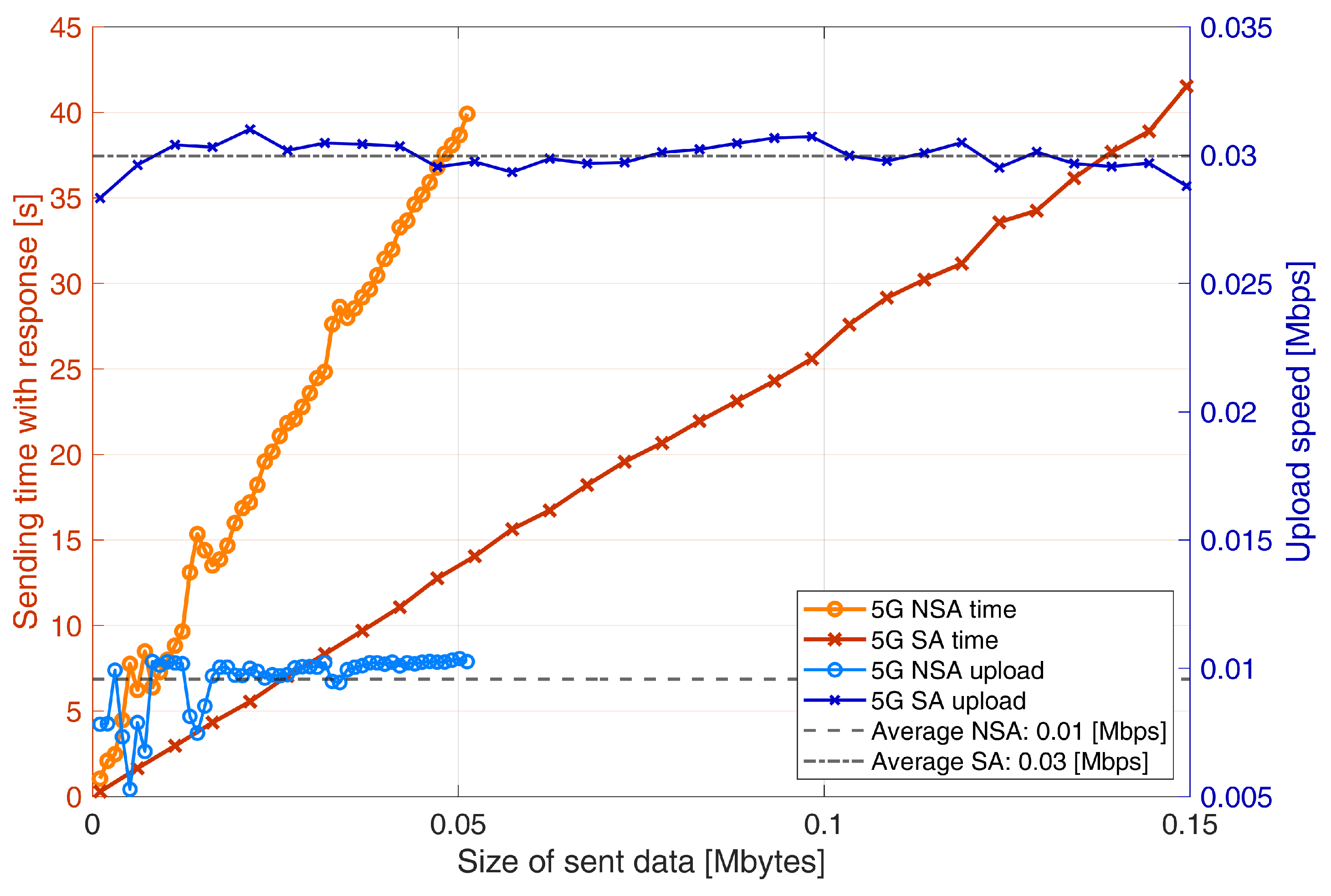

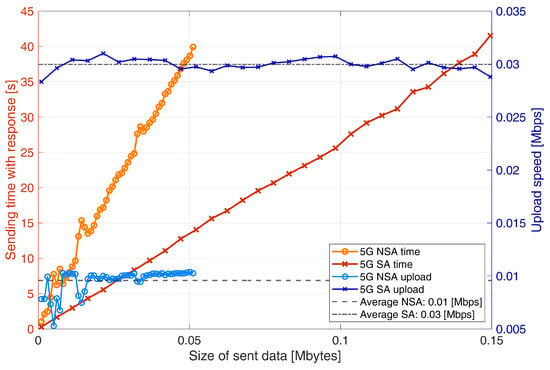

The following are the results of the tests of the communication protocols for sending data from the client to the server, where in each test, the data size was increased by 1024 bits. First, we tested the Modbus communication protocol, and the results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Uplink transmission time (left axis) and upload throughput (right axis) versus payload size for the Modbus TCP protocol over 5G NSA and 5G SA networks (representative run).

The main disadvantage of the old Modbus protocol is a significant overhead, i.e., to send a small amount of data, the transmission itself must send many times more raw data. As you would expect, the time taken to send data and receive the data accepted by the server increases linearly with the amount of data (5G NSA time and 5G SA time).

However, it is noticeable that the NSA network only achieves a bandwidth of 0.01 Mbps (Average NSA) and an SA of 0.03 Mbps (Average SA). When testing the NSA network, the test was aborted after the size of the data sent reached 0.05 Mbytes (it took more than 40 s to send data and receive the message that the data had been received). Based on the results, we can clearly say that the Modbus protocol has a large overhead and is suitable for the transmission of sensor data, which can be 1 or 0 or other smaller data sets, and not for larger data such as images. Since the NSA has a high Ping value, this also has a strong influence on the Modbus results.

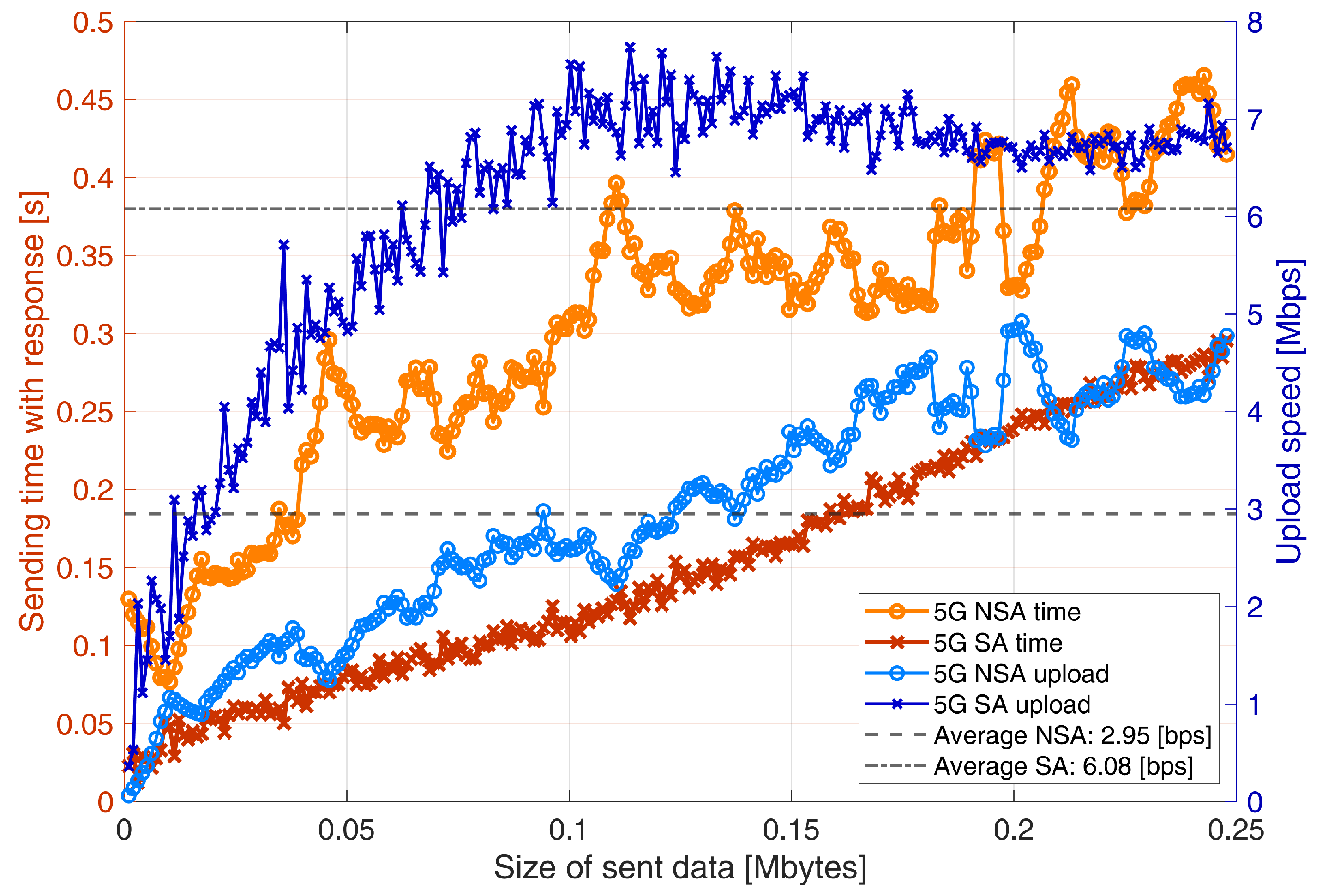

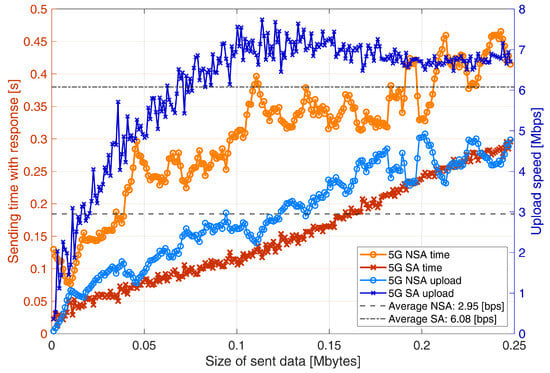

The next test was carried out with the EtherCAT industrial protocol, which is newer than Modbus. The results in Figure 6 show the advantage of the SA network with lower latency for faster data transfer from client to server. The average upload rate was 2.95 Mbps for NSA and 6.08 Mbps for SA, which is about 30% of the potential bandwidth we achieved on both networks during the iPerf3 tests with a parallel port. This protocol therefore consumes much less overhead and is suitable for transmitting larger industrial data volumes.

Figure 6.

Uplink transmission time and upload throughput versus payload size for the EtherCAT protocol over 5G NSA and 5G SA networks (representative run).

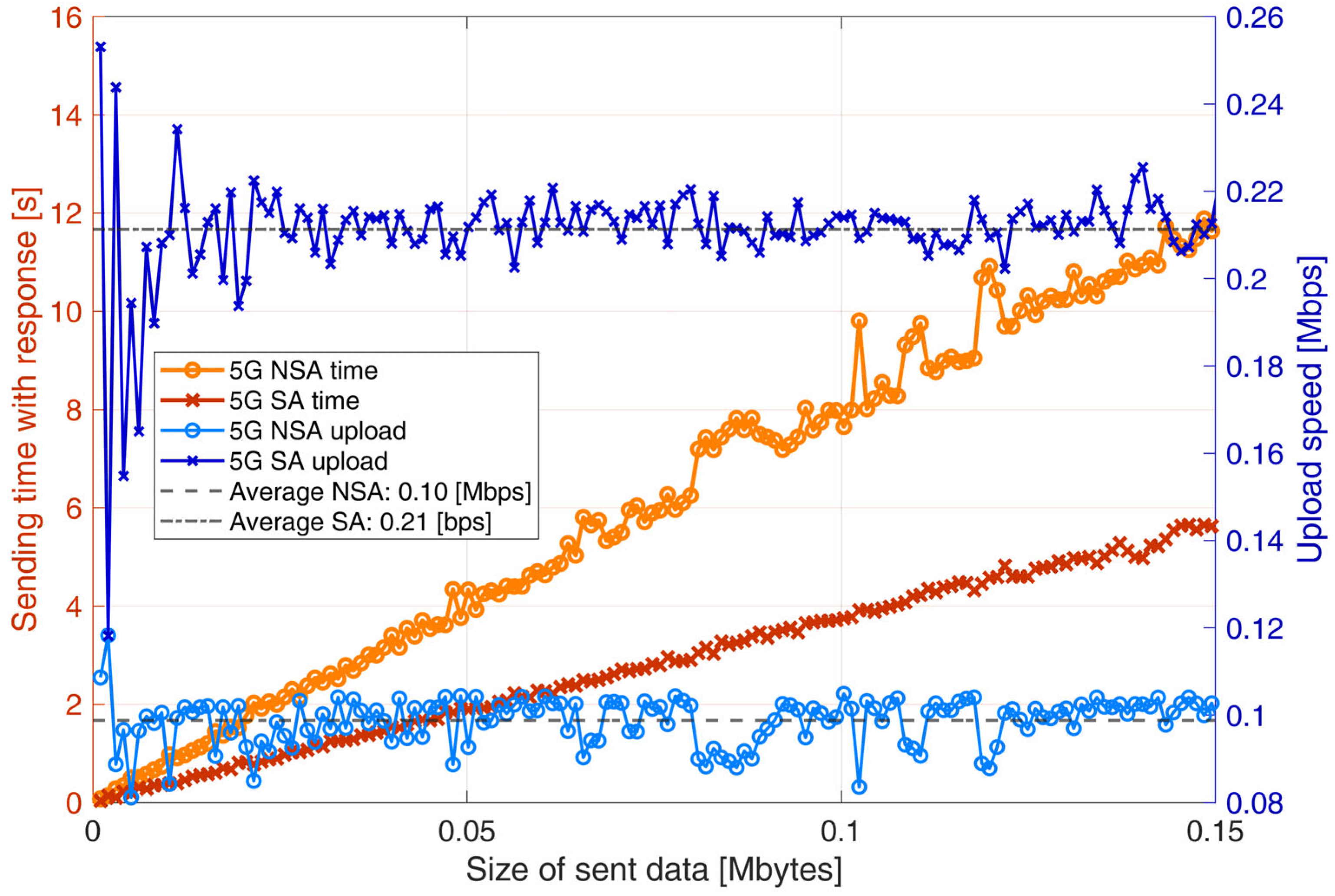

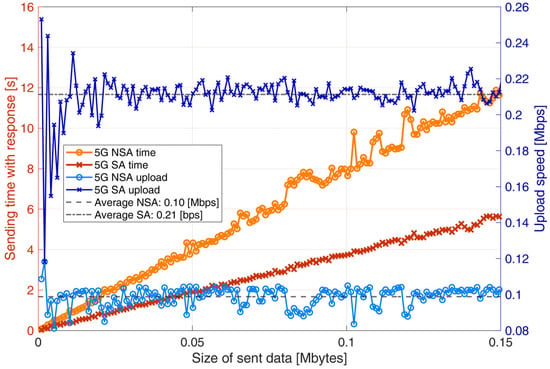

The last industry protocol tested was OPC UA. The data transmission time is also linear to the amount of data sent and reaches 0.1 Mbit/s for the NSA network and 0.21 Mbit/s for the SA network as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Uplink transmission time and upload throughput versus payload size for the OPC UA protocol over 5G NSA and 5G SA networks (representative run).

In the case of the 5G SA network, the upload speed increases almost linearly as the size of the transmitted data increases, up to around 0.1 MBytes. Beyond this threshold, the upload speed tends to stabilize, indicating that the network has reached a saturation point in terms of its ability to efficiently process larger amounts of data under the observed conditions. A similar trend can be observed for the 5G NSA network, although the results appear much more irregular. This increased variability is due to the higher jitter measured in the NSA setup (20.13 ms), which, combined with the operational characteristics of the OPC UA communication protocol, results in a noisy data set. The delays caused by the jitter in NSA mode disrupt the time-dependent nature of OPC UA transactions, resulting in fluctuations in the measured upload speeds.

Compared to EtherCAT, it is slower because it involves a greater overhead when sending data and is not intended for real-time control. The large overhead can be attributed to the additional functionality of OPC UA communication, which includes advanced security features such as inscription and user identification.

4.3. Lightweight IoT Communication Protocols

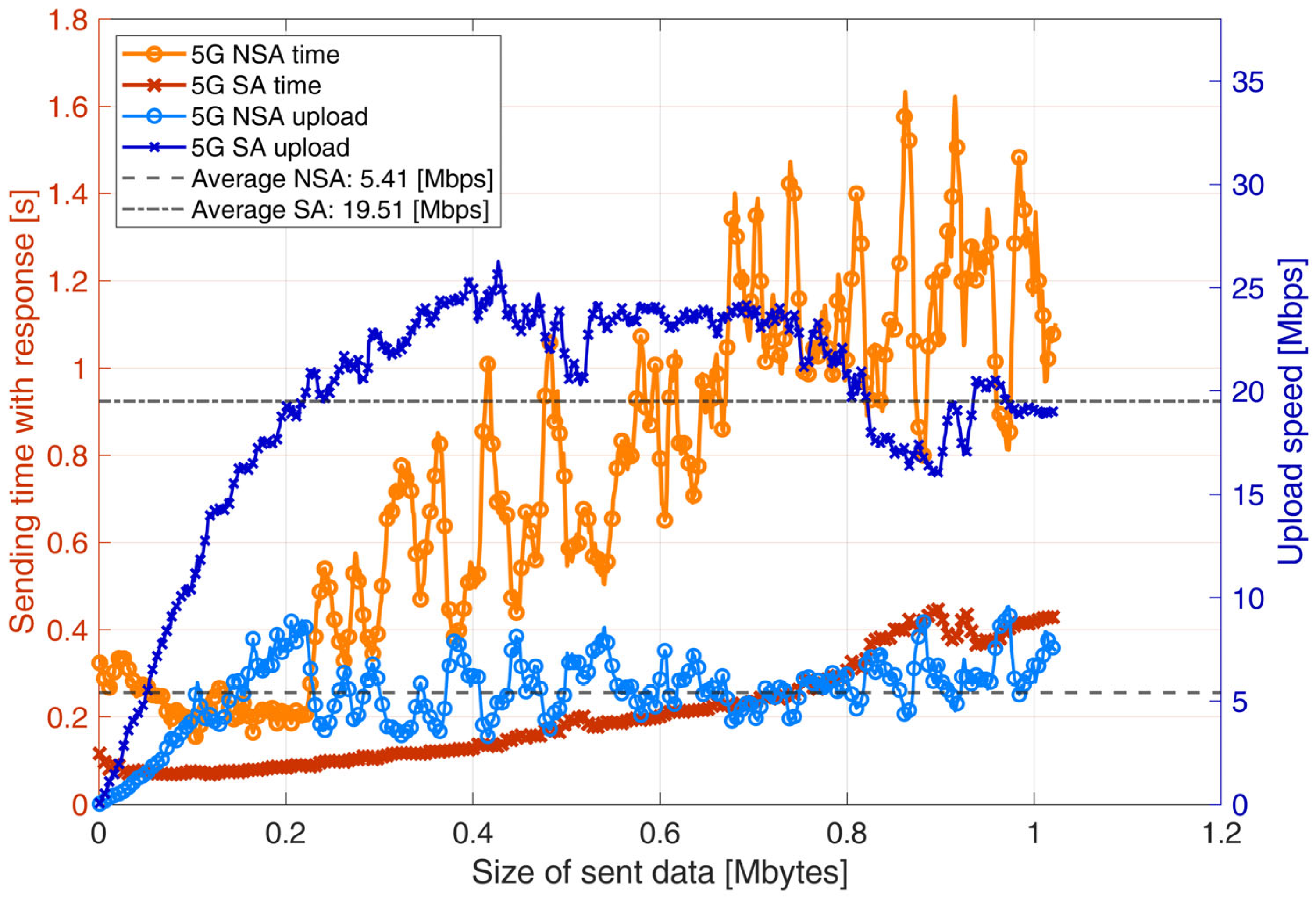

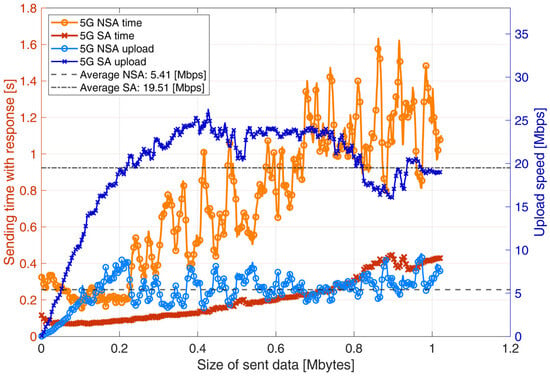

The next group of communication protocols consists of three protocols developed and commonly used for IoT communication. The MQTT communication protocol, which is also the most commonly used protocol in IoT due to its low overhead, clearly shows its advantages over others when used over a 5G NSA or SA network. The average upload speed of 5.41 Mbps for the NSA network and 19.51 Mbps for the SA network clearly shows that the entire communication stream is used with minimal overhead, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Uplink transmission time and upload throughput versus payload size for the MQTT protocol over 5G NSA and 5G SA networks (representative run).

This means MQTT’s integrated security is not that sophisticated, which means it must be used with caution based on where and why it is used. The only drawback is that when sending smaller datasets, the entire upload channel is not fully utilized. However, even in such cases, it remains faster than almost all communication protocols, with only EtherCAT being faster. Of course, this also means that MQTT lacks built-in sophisticated security, requiring careful consideration depending on its intended use and environment. The AMQP communication protocol evolved relatively smoothly with some fluctuations, as can be seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

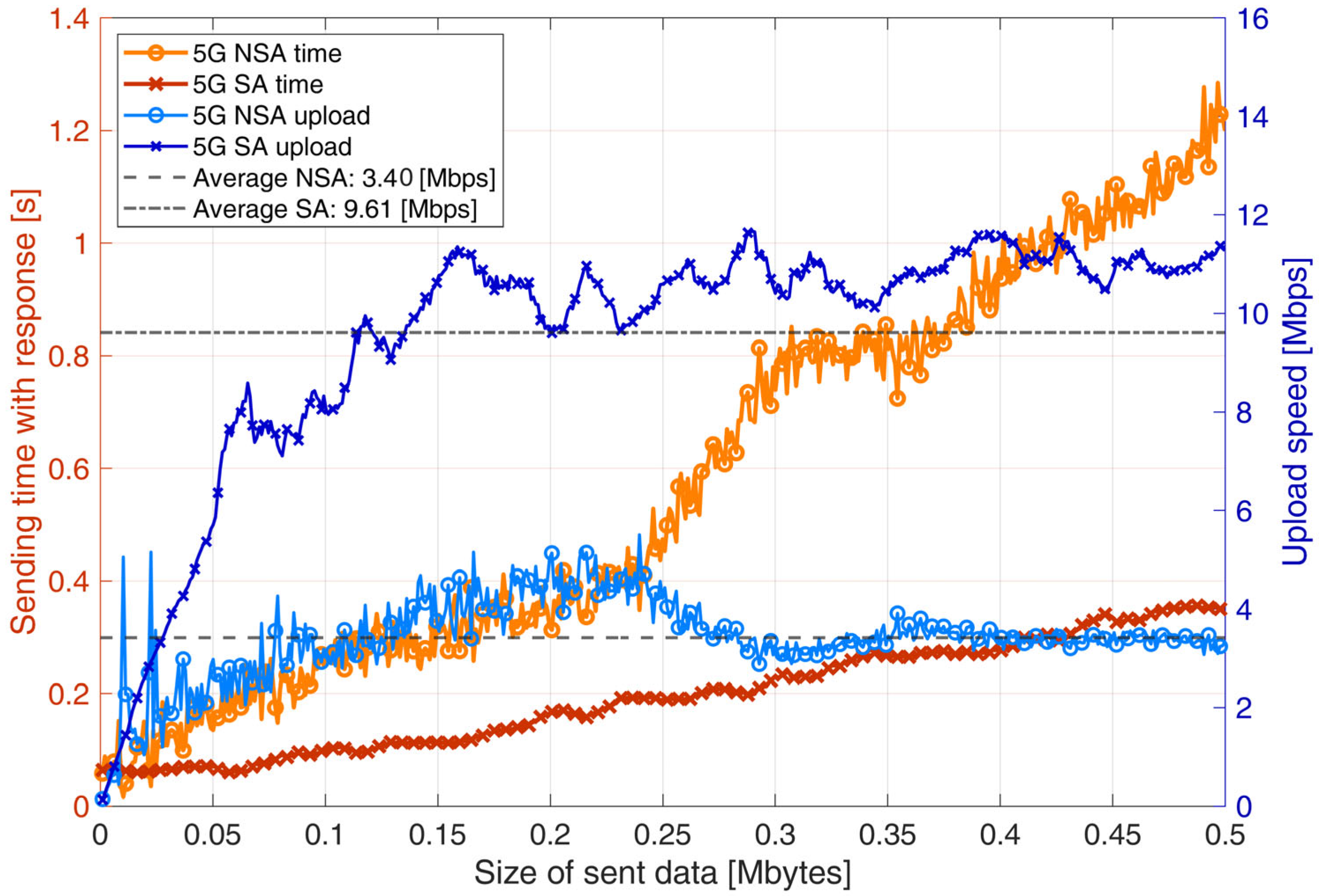

Uplink transmission time and upload throughput versus payload size for the AMQP over 5G NSA and 5G SA networks (representative run).

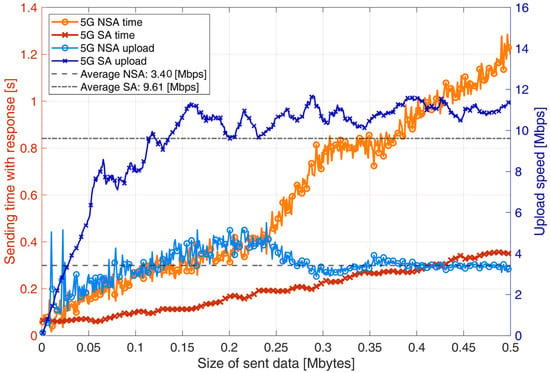

The relationship between the time to send data and the amount of data is considered linear after conducting several experiments. The maximum upload speed for NSA is 3.40 Mbps and 9.61 Mbps for SA. The protocol had the second highest throughput of all tested protocols, which means that it has a low overhead. It is clear from the graph that sending larger amounts of data with this communication protocol enables faster upload speeds than sending smaller amounts of data.

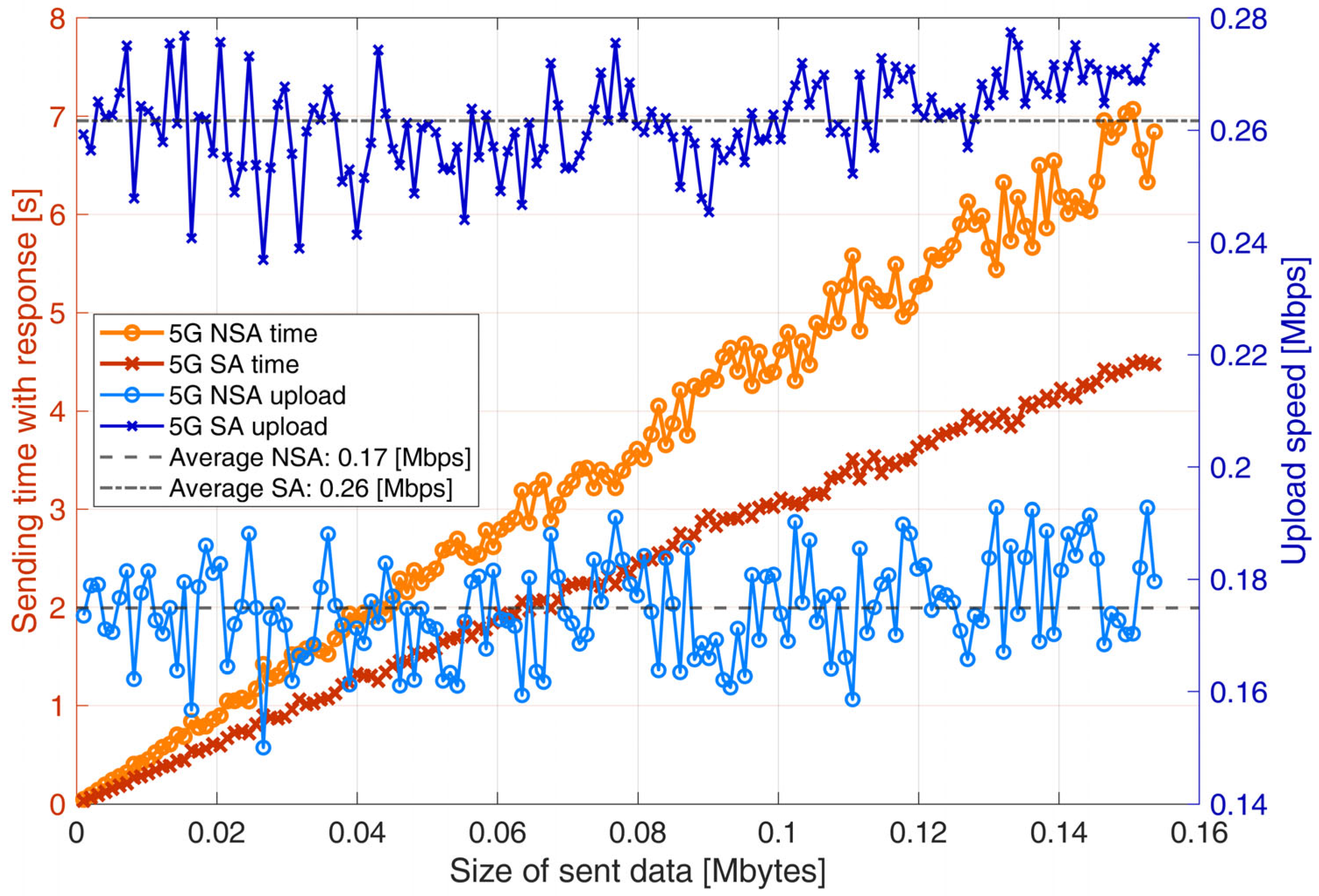

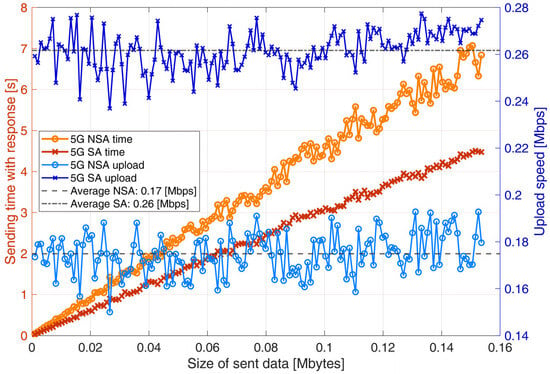

Of the communication protocols examined, CoAP showed the most consistent and predictable performance. As shown in Figure 10, the relationship between the transmission time and the size of the transmitted data shows a clear linear trend for both 5G NSA and 5G SA network configurations.

Figure 10.

Uplink transmission time and upload throughput versus payload size for the CoAP protocol over 5G NSA and 5G SA networks (representative run).

This indicates a stable transmission process with minimal fluctuations, further confirming the reliability of CoAP in time-critical applications. In addition, the measured upload speeds remain largely unaffected by the amount of data transmitted. The average upload speeds were 0.17 Mbps for the 5G-NSA network and 0.26 Mbps for the 5G-SA network, highlighting CoAP’s ability to maintain constant throughput regardless of payload size or transmission frequency.

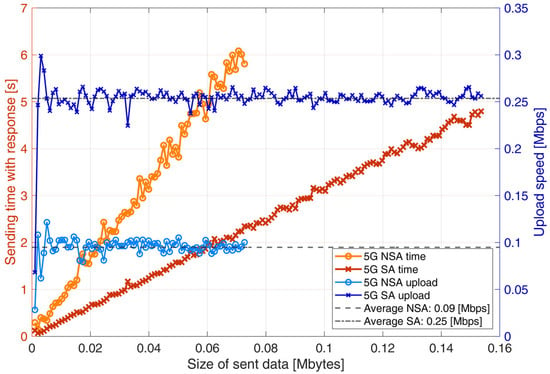

4.4. High-Bandwidth Communication Protocols Results

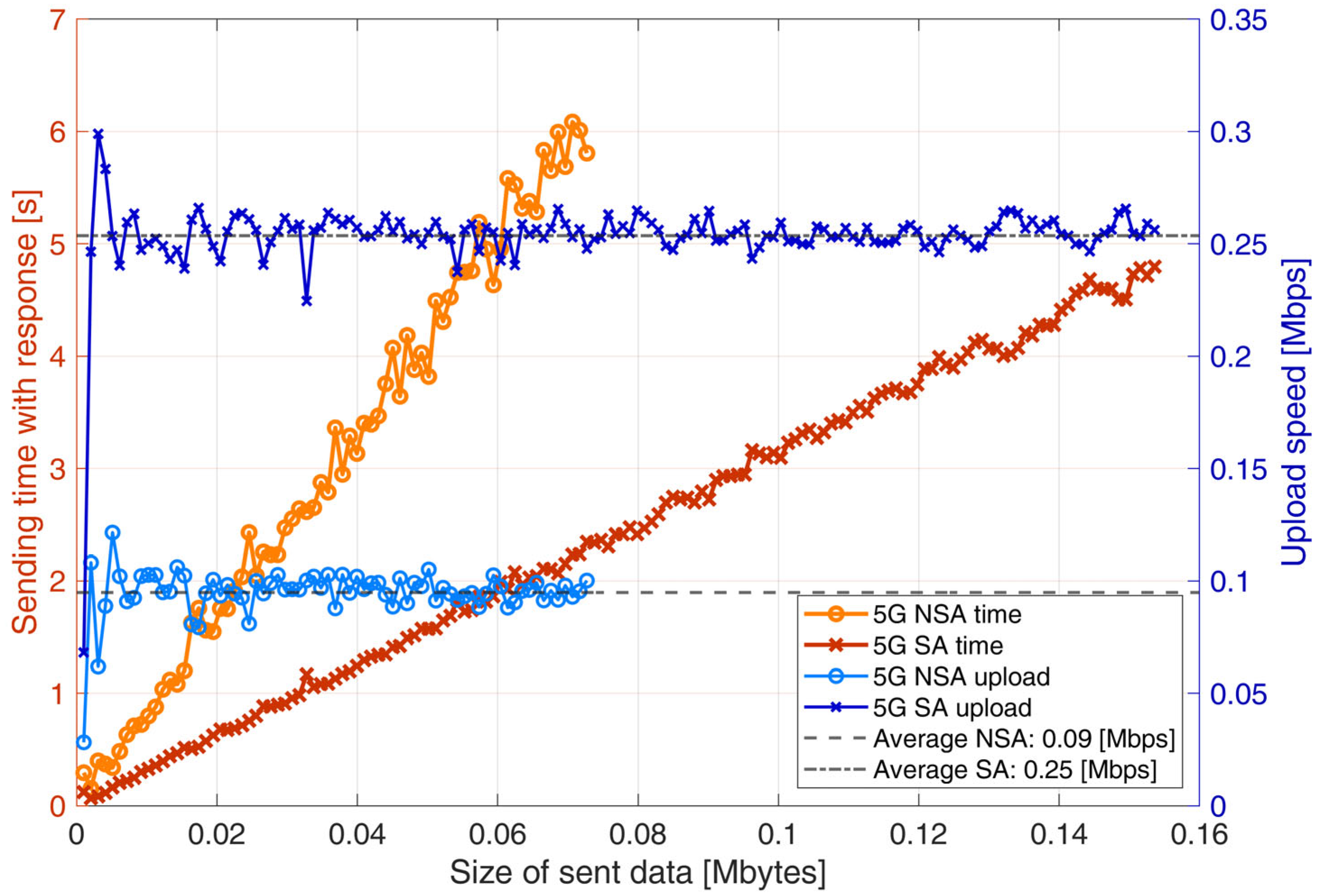

In this section, only the gRPC protocol was tested and used for comparison with others. The characteristics of the protocol (shown in Figure 11) are similar to those of CoAP and show a linear correlation between the size of the data sent and the sending time, regardless of the data size (as with MQTT or CoAP). The maximum upload speed is 0.09 Mbit/s for the NSA network and 0.25 Mbit/s for the SA network. There is minimal noise detected, which means that communication is not influenced by changing latency (Ping), especially in the 5G NSA network. The upload speeds are constant and not influenced by the sent packet size.

Figure 11.

Uplink transmission time and upload throughput versus payload size for the gRPC protocol over 5G NSA and 5G SA networks (representative run).

5. Discussion

The tests conducted show significant differences in the characteristics and performance of industrial and IoT communication protocols when used over 5G SA and NSA networks. The performance differences between the various protocols are due to fundamental differences in data overhead, transmission methods and dependence on network latency.

An important observation is the influence of Ping latency on the upload measurements. The results show that higher latency in NSA networks significantly degrades performance, especially for high overhead protocols such as Modbus and OPC UA. This is because higher round-trip times delay the acknowledgment signals, resulting in slower data exchange. In contrast, the lower latency in 5G SA networks enables more efficient communication, especially for EtherCAT and MQTT, which have strong performance advantages due to their lean transmission protocols and minimal overhead.

The UDP packet loss measurements complement the TCP throughput results by revealing the reliability limits of both 5G architectures under increasing load. While TCP throughput indicates the maximum sustainable data rate, UDP measurements expose the threshold behavior once network capacity is approached. In both configurations, very low packet loss was observed at low and moderate bitrates; however, a sharp increase in loss occurred once the offered UDP load exceeded the effective uplink capacity. The public 5G NSA network exhibited a higher loss onset at elevated bitrates but more pronounced degradation under congestion, whereas the private 5G SA network maintained superior reliability at low loads but experienced an abrupt collapse once its capacity limit was reached. These results highlight that UDP-based applications are particularly sensitive to operating close to network saturation.

5.1. Strengths and Weaknesses of IoT and Industrial Protocols

Industrial communication protocols, including Modbus, EtherCAT and OPC UA, are designed for robustness and deterministic communication rather than speed. Modbus has a significant overhead that makes it unsuitable for large data transfers, although it remains reliable for a small amount of data, i.e., sensor status updates. EtherCAT, on the other hand, uses low-latency communication to achieve higher throughput and is therefore well suited for real-time control systems. OPC UA includes security features such as encryption and user authentication, which contributes to its lower performance. While these security features make it robust for industrial automation, they introduce an overhead that reduces its suitability for high-speed data transfers. IoT communication protocols such as MQTT, AMQP and CoAP emphasize lean and efficient data transmission. MQTT is characterized by minimal overhead and exceptional performance over both NSA and SA networks, achieving the highest upload speeds. However, it lacks built-in security, so additional security measures are required when used in industrial applications. CoAP has stable and predictable performance, making it a good candidate for resource-constrained IoT applications, while AMQP has strong scalability characteristics for larger data volumes.

5.2. Impact of NSA and SA 5G Networks on Protocol Performance and Scalability

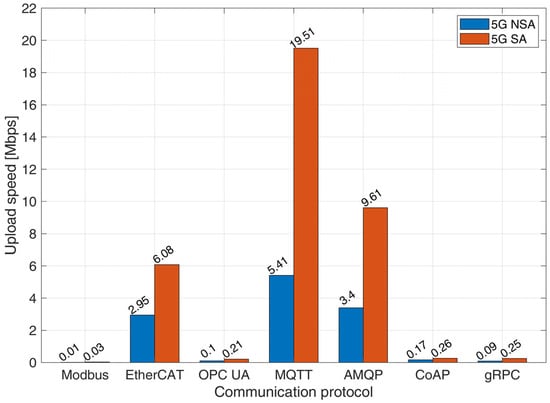

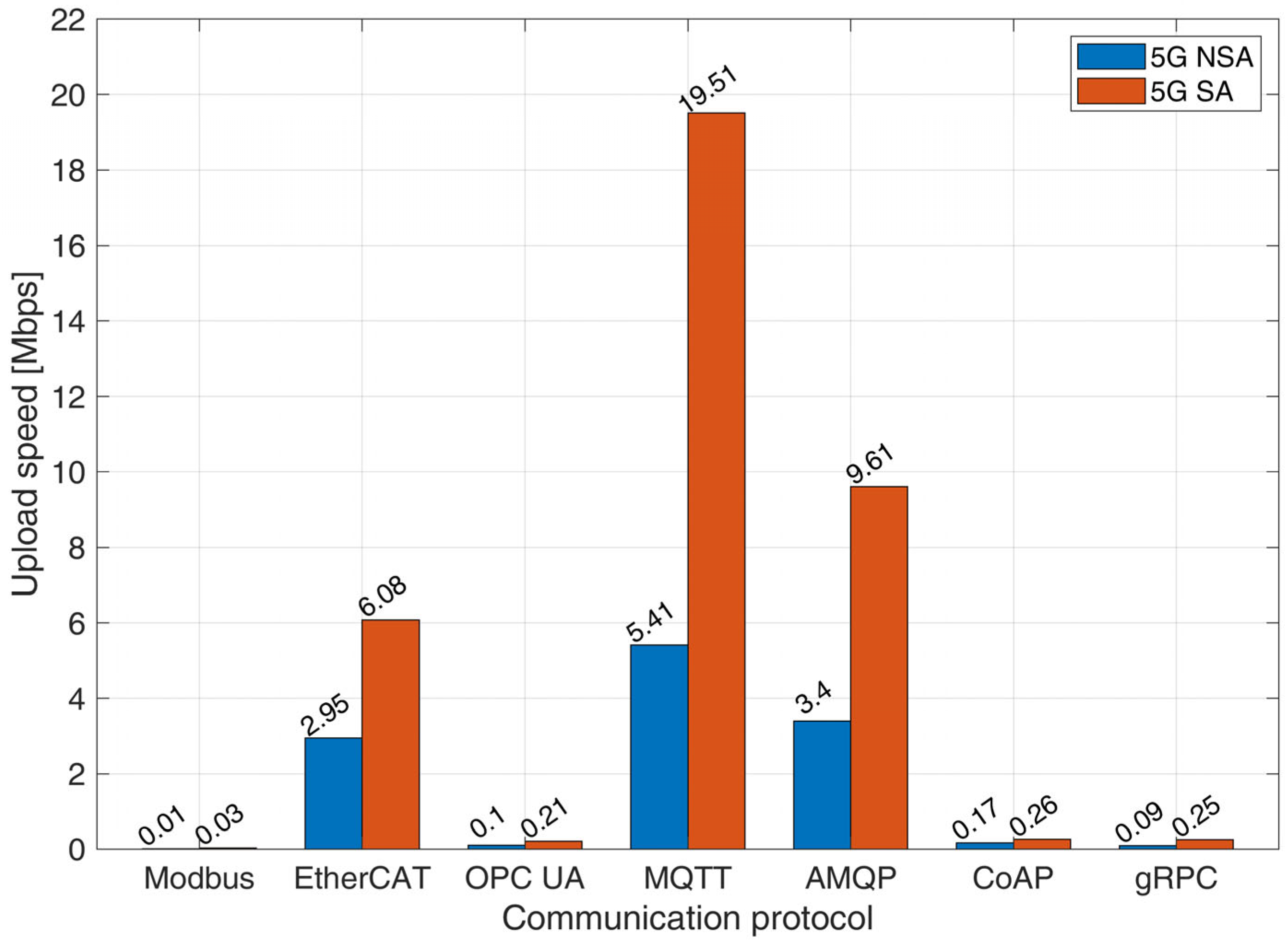

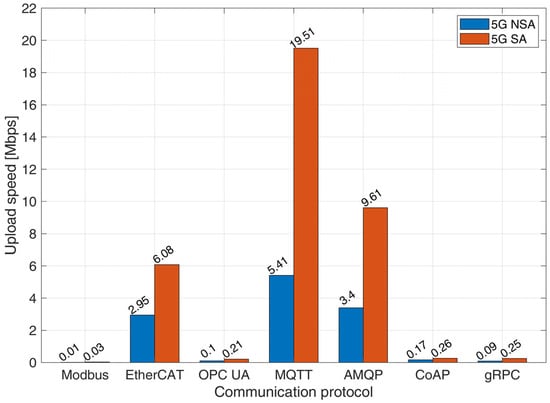

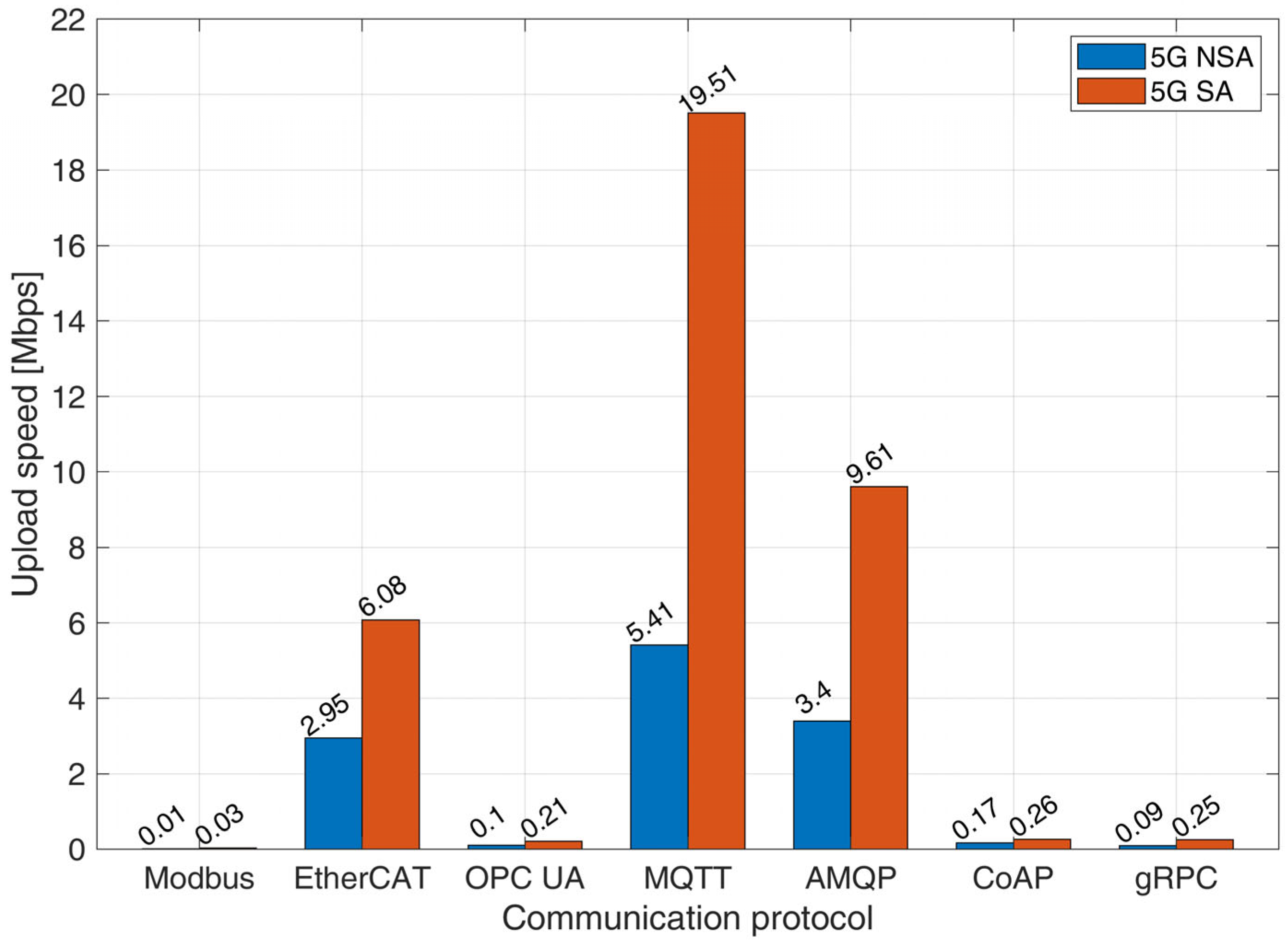

In this section, we evaluate the performance of tested industrial communication protocols in terms of upload speed and upload throughput (iPerf3 test) over standalone (SA) and non-standalone (NSA) 5G networks. Figure 12 shows the quantitative results and highlighted huge differences between the selected communication protocols when compared against each other, and with baseline throughput measurements obtained using iPerf3.

Figure 12.

Mean values are computed from 10 repeated runs; corresponding standard deviations are provided in Table 3.

Figure 12.

Mean values are computed from 10 repeated runs; corresponding standard deviations are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation of uplink upload speed for all tested communication protocols over 5G NSA and SA networks (n = 10).

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation of uplink upload speed for all tested communication protocols over 5G NSA and SA networks (n = 10).

| Protocol | Network | Mean Upload Speed (Mbps) | Std. Deviation (Mbps) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modbus | NSA | 0.01 | 0.0011 |

| SA | 0.03 | 0.0006 | |

| EtherCAT | NSA | 2.95 | 1.2305 |

| SA | 6.08 | 1.4469 | |

| OPC UA | NSA | 0.10 | 0.0054 |

| SA | 0.21 | 0.0121 | |

| MQTT | NSA | 5.41 | 1.7731 |

| SA | 19.51 | 5.5217 | |

| AMQP | NSA | 3.40 | 0.7671 |

| SA | 9.61 | 2.4594 | |

| CoAP | NSA | 0.17 | 0.0078 |

| SA | 0.26 | 0.0081 | |

| gRPC | NSA | 0.09 | 0.0111 |

| SA | 0.25 | 0.0170 |

The latency improvement observed in 5G SA is primarily attributed to architectural simplification, including the use of a native 5G core with unified control and user planes, which reduces signaling overhead and queuing delays compared to NSA deployments.

It should be emphasized that the present analysis intentionally focuses on uplink performance, as industrial and IIoT systems predominantly generate data at the edge and transmit it toward controllers, edge servers or cloud platforms. In contrast, many consumer-oriented 5G studies emphasize downlink throughput, which is less representative of industrial data exchange patterns. The results demonstrate that protocol behavior and efficiency over the uplink differ substantially between 5G SA and NSA configurations, underscoring the importance of considering uplink characteristics when designing wireless industrial communication systems.

Reference upload speeds measured with iPerf3 were 130 Mbps for NSA and 90 Mbps for SA configurations. These values represent the theoretical upper bounds in our experimental setup and provide a baseline for protocol efficiency.

Of the protocols tested, MQTT showed the highest throughput in both the NSA and SA configurations, reaching 5.41 Mbit/s and 19.51 Mbit/s, respectively. Measured against the iPerf3 baseline, MQTT consumed 4.17% of the available NSA bandwidth and 21.68% of the SA bandwidth. This highlights the lightweight design and efficiency of MQTT over wireless networks. AMQP followed NSA with 3.41 Mbps and SA with 9.61 Mbps, representing 2.55% and 10.77% of the available throughput respectively. Similarly, EtherCAT achieved 2.95 Mbit/s (NSA) and 6.08 Mbit/s (SA), which corresponds to an efficiency of 2.27% and 6.76%, respectively.

OPC UA, CoAP and gRPC showed moderate throughput values. OPC UA achieved 0.10 Mbps on NSA and 0.21 Mbps on SA (0.08% and 0.23%), while CoAP achieved 0.18 Mbps and 0.26 Mbps (0.13% and 0.29%). gRPC showed 0.09 Mbps and 0.25 Mbps, corresponding to an efficiency of 0.07% and 0.28%. Modbus, a serial protocol, showed the lowest upload performance with 0.01 Mbit/s (NSA) and 0.03 Mbit/s (SA), corresponding to only 0.008% and 0.033% of the available bandwidth.

A general trend observed across all protocols is a consistent improvement in upload throughput when switching from NSA to SA configuration. The relative improvement varies depending on the protocol. For example, MQTT improved by ~260%, AMQP by ~327% and EtherCAT by ~106%. Even lower throughput protocols such as gRPC and OPC UA showed improvements of ~178% and ~110%, respectively.

These results show that the 5G SA architecture enables significantly higher performance at the protocol level, especially for protocols optimized for low overhead and asynchronous communication. The results are important for the deployment of remote sensing and Industry 4.0 solutions and further 5G hardware development, where communication efficiency has a direct impact on real-time control and data acquisition.

It is important to emphasize that the 5G network for industrial applications is still under development, regardless of whether it is deployed in NSA or SA mode. The key findings of this study, which are crucial for the future development and adaptation of private 5G networks, show that this wireless communication requires a different upload/download ratio and even lower latency than can currently be achieved with private SA 5G networks. These improvements are necessary to provide the industry with a wireless communication technology that supports both horizontal and vertical data exchange for real-time mission-critical process control as well as less demanding industrial applications.

6. Conclusions

The growing adoption of 5G networks in industrial automation, remote sensing and Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) applications has increased the demand for reliable, low-latency and efficient wireless data transfer. Both standalone (SA) and non-standalone (NSA) 5G architectures are considered key enablers for wireless industrial communication, but their practical impact on application layer communication protocols remains insufficiently understood. While existing studies mainly focus on generic network level metrics or downlink performance, there is a lack of experimental work that systematically evaluates how different industrial and IoT communication protocols perform over 5G SA and NSA networks under realistic uplink conditions.

To address this gap, the objective of this paper was to experimentally benchmark a broad range of industrial, IoT and high-bandwidth communication protocols, including Modbus, EtherCAT, OPC UA, MQTT, AMQP, CoAP and gRPC—over both 5G SA and NSA architectures using a unified and reproducible test setup. The study specifically examined uplink performance, protocol overhead, latency sensitivity, throughput efficiency, and UDP reliability and related protocol results to baseline network capacity measurements obtained using iPerf tools. This approach enables a direct assessment of how architectural differences between 5G SA and NSA networks influence communication protocol behavior and suitability.

The results clearly show that different communication protocols work optimally under certain conditions. EtherCAT is the most suitable protocol for industrial real-time control due to its low overhead and efficient data exchange, especially when used over a 5G SA network. OPC UA remains a preferred option for secure industrial communication despite its lower performance, as its built-in encryption and authentication mechanisms provide a higher level of protection. MQTT proves to be the most efficient IoT protocol due to its minimal overhead and high throughput. However, it requires additional security measures when used in critical applications. AMQP exhibits high scalability when processing larger amounts of data, making it a viable option for cloud-based messaging and distributed systems. CoAP offers stable and predictable performance, making it well-suited for resource-constrained IoT applications.

The impact of SA and NSA networks on protocol behavior is significant. SA networks offer lower latency and improved stability, which benefits latency-sensitive industrial and real-time IoT applications. NSA networks, on the other hand, offer higher overall bandwidth by utilizing the LTE infrastructure and are therefore better suited for non-time-critical applications. Protocols with significant overhead, such as OPC UA and Modbus, struggle in NSA networks due to increased latency, while lightweight protocols such as MQTT and CoAP maintain their efficiency in both environments.

The results also show that 5G networks for remote sensor sensing and industrial applications are still evolving, whether in NSA or SA mode. A key insight for the future development of private 5G networks is that this type of wireless communication requires a different upload/download ratio and even lower latency than what current private SA 5G networks can achieve. These improvements are essential to enable reliable wireless communication for real-time mission-critical process control and efficient horizontal and vertical data exchange in industrial environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; Methodology, M.P.; Software, M.P. and M.Š.; Validation, M.P.; Formal analysis, M.P.; Investigation, M.P. and M.Š.; Resources, M.P.; Data curation, M.P.; Writing—original draft, M.P.; Writing—review & editing, M.P., M.Š. and N.H.; Visualization, M.P., M.Š. and N.H.; Supervision, N.H.; Project administration, N.H.; Funding acquisition, N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency—ARIS, research project J2-4470 and research program P2-0248. This research was funded and implemented within the framework of the European Union under the Horizon Europe Grants N°101087348 (INNO2MARE) and N°101058693 (STAGE), and the NextGenerationEU project GREENTECH.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rachakonda, L.P.; Siddula, M.; Sathya, V. A comprehensive study on IoT privacy and security challenges with focus on spectrum sharing in Next-Generation networks (5G/6G/beyond). High-Confid. Comput. 2024, 4, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessi, C.C.; Gavrielides, A.; Solina, V.; Qiu, R.; Nicoletti, L.; Li, D. 5G and Beyond 5G Technologies Enabling Industry 5.0: Network Applications for Robotics. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasandideh, F.; da Costa, J.P.J.; Kunst, R.; Islam, N.; Hardjawana, W.; de Freitas, E.P. A Review of Flying Ad Hoc Networks: Key Characteristics, Applications, and Wireless Technologies. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, X. An Effective Scheme for Modeling and Compensating Differential Age Errors in Real-Time Kinematic Positioning. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Xu, C.; Tang, S.; Huang, Y.; Qi, W.; Xiao, Z. Performance Analysis of an Aerial Remote Sensing Platform Based on Real-Time Satellite Communication and Its Application in Natural Disaster Emergency Response. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, N.; Losa, M. Road Detection, Monitoring, and Maintenance Using Remotely Sensed Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.; Oregui, X.; Ojer, M. Edge architecture for the automation and control of flexible manufacturing lines. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 237, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerodimos, A.; Maglaras, L.; Ferrag, M.A.; Ayres, N.; Kantzavelou, I. IoT: Communication protocols and security threats. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zezulka, F.; Marcon, P.; Bradac, Z.; Arm, J.; Benesl, T. Time-Sensitive Networking as the Communication Future of Industry 4.0. IFAC-Pap. 2019, 52, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabkhot, M.M.; Ferreira, P.; Eaton, W.; Lohse, N. Estimating adaptation effort in industry 4.0-enabled systems: Introducing two complexity indices with an evolvable network graph approach. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 40, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehmi, H.; Amr, M.F.; Bahnasse, A.; Talea, M. 5G Network: Analysis and Compare 5G NSA/5G SA. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 203, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahj, J.N.M.; Ogudo, K.A.; Boonzaaier, L. A hybrid analytical concept to QoE index evaluation: Enhancing eMBB service detection in 5G SA networks. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2024, 221, 103765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchet, L.; Casari, P. Assessing a Private 5G SA and a Public 5G NSA Architecture for Networked Music Performances. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Symposium on the Internet of Sounds, Pisa, Italy, 26--27 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozis, E.Z.G.; Sagias, N.C.; Batistatos, M.C.; Kourtis, M.A.; Xilouris, G.K.; Kourtis, A. Enhancing 5G performance: A standalone system platform with customizable features. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2024, 187, 155515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, F.; Gohar, M.; Alquhayz, H.; Koh, S.J.; Choi, J.G. Performance evaluation of AMQP over QUIC in the internet-of-thing networks. J. King Saud. Univ. -Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreier, J.; Puys, M.; Potet, M.L.; Lafourcade, P.; Roch, J.L. Formally and practically verifying flow properties in industrial systems. Comput. Secur. 2019, 86, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombate, Y.; Houngue, P.; Ouya, S. Securing MQTT: Unveiling vulnerabilities and innovating cyber range solutions. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 241, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, M.; Moon, A.H. A novel lightweight multi-factor authentication scheme for MQTT-based IoT applications. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2024, 110, 105088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouadghiri, M.; Aghoutane, B.; El Farissi, N. Communication model in the Internet Of Things. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 177, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, N.; Hill, J.H. A generalized approach to real-time, non-intrusive instrumentation and monitoring of standards-based distributed middleware. J. Syst. Archit. 2021, 117, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Bui, D.T.; Tran, T.L.; Truong, C.T.; Truong, T.H. Scalable and resilient 360-degree-video adaptive streaming over HTTP/2 against sudden network drops. Comput. Commun. 2024, 216, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Costa, B.; Forkan, A.R.M.; Kang, Y.-B.; Marti, F.; McCarthy, C.; Ghaderi, H.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Jayaraman, P.P. 5G enabled smart cities: A real-world evaluation and analysis of 5G using a pilot smart city application. Internet Things 2024, 28, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muteba, K.F.; Djouani, K.; Olwal, T. 5G NB-IoT: Design, Considerations, Solutions and Challenges. In Procedia Computer Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Olesen, K.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Pedersen, G.F.; Fan, W. Single-port measurement scheme: An alternative approach to system calibration for 5G massive MIMO base station conformance testing. Measurement 2023, 220, 113083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, T.; Hermann, J.; Dietrich, F.; Kuhn, C.; Angos, M.; Jooste, J.L.; Palm, D. Measurement and comparison of data rate and time delay of end-devices in licensed sub-6 GHz 5G standalone non-public networks. Procedia CIRP 2022, 107, 1132–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union. ITU-T Series G: Transmission Systems and Media, Digital Systems and Networks; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/IEC 7498-1:1994; Information Technology—Open Systems Interconnection—Basic Reference Model: The Basic Model. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994.

- Constantine, B.; Forget, G.; Geib, R.; Schrage, R. Framework for TCP Throughput Testing. Internet Eng. Task Force 2011, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 15802-3:1998; Information Technology—Telecommunications and Information Exchange Between Systems—Local and Metropolitan Area Networks—Common Specifications—Part 3: Media Access Control (MAC) Bridges. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland; International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.