Abstract

The study of the forest in rainy environments of the Dominican Republic reveals the presence of four types of vegetation formations, clearly differentiated from each other in terms of their floristic and biogeographical composition, and also significantly different from the rainforests of Cuba. This leads us to propose two new alliances and four plant associations located in northern mountain areas exposed to moisture-laden winds from the Atlantic: All. Rondeletio ochraceae-Clusion roseae (Ass. Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum motanae; Ass. Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae); and All. Rondeletio ochraceae-Didymopanion tremuli (Ass. Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis; Hyeronimo dominguensis-Magnolietum hamorii). We pay special attention to the description of cloud forest types, since they have a high rate of endemic species, and therefore there are endemic habitats, which need special protective actions. Therefore, we apply the Shannon diversity index to characteristic, companion, non-endemic, and endemic species. As result, the association Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae has a Shannon_T = 2.4 and a value of Shannon_E = 0, whereas the other 3 associations have a better conservation status with Shannon values in all cases > 0: This is due to a worse conservation status of the Eastern Cordillera, in comparison with the Central Cordillera and Sierra de Bhaoruco. Due to human activity, some areas are very poorly conserved, as evidenced by the diversity index and the presence of endemic tree and plant elements. The worst conserved in terms of the relationship between characteristic plants vegetation (cloud forest) in areas with high rainfall are in the Dominican Republic, along with its floristic diversity and state of conservation. This study has made it possible to significantly increase the botanical knowledge of this important habitat.

1. Introduction

The territory of the Dominican Republic (DR), with an extension of 48,198 km2 including the small adjacent islands, accounts for over two thirds of the territory of Hispaniola, an island located between parallels 17–19° N in the group of the Greater Antilles. Most previous botanical studies have concentrated predominantly on the flora, for example the work of García et al. [1] in the Sierra de Bahoruco, and highlight the abundant rainfall of up to 4000 mm and the very high rate of endemic species. There are also other studies by several authors on the cloud forest in the Cordillera Central, Septentrional, and Oriental ranges [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. All these works, together with previous studies carried out by ourselves [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], have enabled us to undertake the present work. All the aforementioned studies focus attention on the knowledge of the flora, with only passing references to the vegetation. There are studies of this type in the neighboring islands such as Cuba [31,32] giving similar physiognomic aspects between the two islands, but with high floristic differences. Consequently, our objective is to discern whether the existing vegetation on both islands is the same or different and, secondly, to study the cloud forest in the Dominican Republic applying the phytosociological method. Not having phytosociological studies on the cloud forest, we have only been able to use some floristic publications, and some works on vegetation, but of physiognomic type, in which the distribution of the species is revealed. These works, which together with those of ours in which we made the distribution of more than 1500 endemic species, have helped us to tackle this work of the cloud forest. Once the plant communities were described, we completed an analysis of species diversity. For this, we used the Shannon index to the different groups of species of each phytosociological table (characteristics, companions, non-endemics, and endemics), to see the state of conservation.

So, the main aim of this work is to determine the forest vegetation (cloud forest) in areas with high rainfall in the Dominican Republic, along with its floristic diversity and conservation status.

2. Results

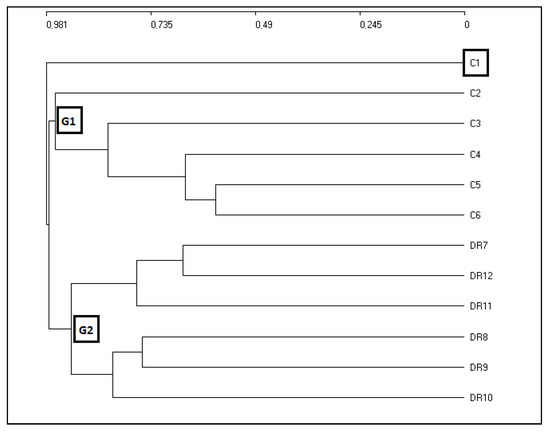

The results of the analysis of Jaccard distances (Figure 1), applied to six plant communities in Cuba and six in the DR, show that the six communities described in Cuba by [31,32,33,34,35,36,37] can be separated into the community C1 and the group G1 (C2, C3, C4, C5, C6). C1 is differentiated from the rest in terms of its floristic, structural, and ecological composition, as this is a pinewood of Pinus maestrensis Bise growing in rainy environments but on highly oligotrophic soils, in common with the other communities in group G1, which is floristically significantly different from group G2. There are very significant floristic differences between Cuba and the DR which can be observed analyzing Table 1 and Table 2, with 173 species present in the samplings in the DR but not in Cuba, whereas the samplings in Cuba reveal 139 plants that are absent from the DR. Establishing the floristic differentiation between both islands is essential for current phytosociological studies. In group G2, which includes 32 of our own relevés and those one of [9,10] (DR7, DR8, DR9, DR10, DR11, DR12), the communities can be seen to form a group for the DR representing different types of forests; these formations are a series of plant communities in very rainy environments in the Dominican Republic (DR) located in the Sierra de Bahoruco and the Cordillera Central and Oriental ranges, with rainfall of over 2000 mm. Group G2 is broken down into two subgroups of plant communities DR7-DR11-DR12 and DR8-DR9-DR10, as the first three correspond to areas with acid substrates and rainy environments in the Cordillera Central range, whereas the second subgroup contains communities growing on different kinds of substrates and in hyper-humid environments. We therefore focused on the analysis of 17 of our own samplings to which we apply a Euclidean distance cluster analysis and an ordination analysis (DCA), both of which perfectly separate the sampling groups. We carried out this analysis to establish the different forests groups, and then to establish the phytosociological tables.

Figure 1.

Jaccard distance cluster. Cluster analysis for the associations of Cuba and the Dominican Republic (DR). The six communities described in Cuba by [31,32,33,34,35,36,37] are separated into the community C1 and group G1 (C2, C3, C4, C5, C6). G2 includes 32 of our own relevés and those one of [9,10] from the Dominican Republic (DR) (DR7, DR8, DR9, DR10, DR11, DR12).

Table 1.

Plant species found in Cuba [31,32] but not present in the relevés from the Dominican Republic.

Table 2.

Plant species found with our studies in the Dominican Republic (DR) and not present in the relevés from Cuba [31,32].

2.1. Phytosociological Study

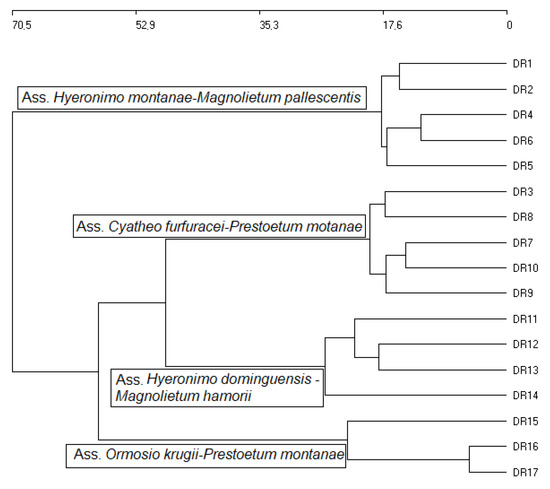

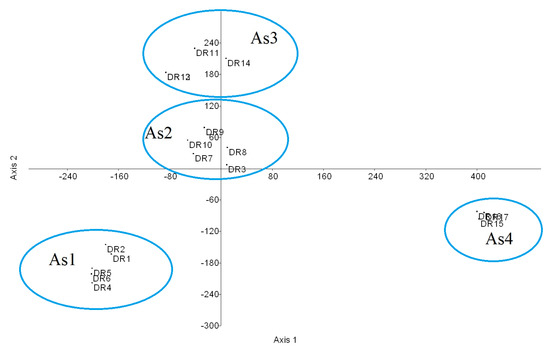

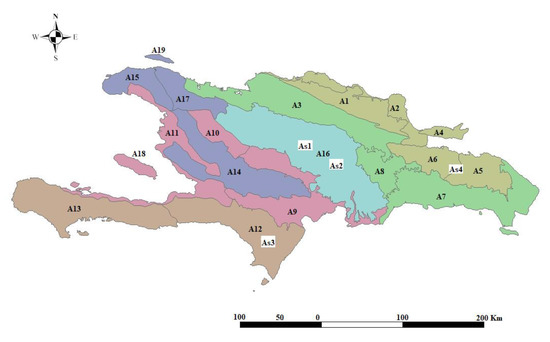

The statistical analysis of the samplings from the DR reveals the existence of four forest plant associations (Figure 2): As1 Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis nova hoc loco (Appendix A, Table A1, rel. DR1, DR2, DR4, DR5, DR6; typus rel. DR4), growing at altitudes of between 1300 and 1500 m on siliceous substrates in the Cordillera Central range (central biogeographical district), and in rainy environments with a humid ombrotype and a mesotropical thermotype [16,23,38,39]. These forests contact in hyper-humid areas with forests of Prestoea montana (Grah.) Nichol, and have a high floristic diversity with 21 trees, eight climbing species, and five epiphytes, and a high rate of endemisms (14 species); at higher altitudes, above the sea of clouds, the cloud forest of Magnolia pallescens contacts the pine forest of Pinus occidentalis, association Dendropemom phycnophylli-Pinetum occidentalis [22]. As2 Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum montanae nova hoc loco (Appendix A, Table A2, rel. DR3, DR7, DR8, DR9, DR10; typus rel. DR3) is a plant community dominated by Prestoea montana, always found in hyper-humid environments, generally in very rainy and shady gorges, contacting with the previous association towards areas that are somewhat less rainy and more exposed to sun and wind. It also has a high diversity, with 40 tree and 25 epiphyte species. Due to the catenal contact between both associations, As1 and As2 have common species: therefore, they are statistically close (Figure 3). Indeed, the total diversity of the 4 associations is shown in the H’ index values, as well as in the analysis of the phytosociological tables. As3 Hyeronimo dominguensis-Magnolietum hamorii nova hoc loco (Appendix A, Table A3, rel. DR11, DR12, DR13, DR14; typus rel. DR11) represents forests of Magnolia in the Sierra de Bahoruco, which develop on calcareous substrates in humid environments at altitudes of around 1200–1300 m in a humid ombrotype and a mesotropical thermotype, with a high number of tree (25) and epiphyte (14) species; in this case the cloud forest connects with the pine forest belonging to the Cocotrino scopari-Pinetum occidentalis association. As4 Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae nova hoc loco (Appendix A, Table A4 rel. DR15, DR16, DR17; typus rel. DR16), an association characterized by a high diversity of trees (27 species), and a lower number of endemic species than the previous associations. The four associations present a clear floristic and biogeographical differentiation (Figure 4) [17,18,40]. The biogeographic strength and the high floristic and ecological differentiation allow us to establish the four plant associations, despite not having a greater number of inventories. However, these associations present a high number of endemisms, which allows us to treat them as endemic habitats of interest for conservation. In the synthetic analysis (Table 3) the great floristic differentiation between the 4 plant communities can be seen, with the floristic differences among them being 25.7% (As1), 40.6% (As2), 20.7% (As3), and 36.6% (As4): these floristic differences between the 4 associations have been selected from the synthetic table.

Figure 2.

Cluster analysis for the Dominican Republic (DR) relevés. Euclidean distance using Ward’s method separating the four associations (Ass.) found in DR relevés.

Figure 3.

Detrended correspondence analysis (DCA). DCA analysis confirming the separation of the four associations (As1 Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis; As2 Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum montanae; As3 Hyeronimo dominguensis-Magnolietum hamorii; As4 Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae) found in Dominican Republic (DR) relevés.

Figure 4.

Biogeographical distribution of the associations in the study. As1: Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis (A16: central district). As2: Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum montanae (A16: central district). As3: Hyeronimo dominguensis-Magnolietum hamorii (A12: Bahoruco district). As4: Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae (A5: eastern district) (from Cano–Ortiz et al., modified [28]).

Table 3.

Synthetic table of the four new associations considered in this study.

The four associations described are included in the phytosociological classes Cyrillo-Weinmannietea pinntae Borhidi 1996 and Ocoteo-Cyrilletea rceniflorae Borhidi 1996. Due to the high floristic and biogeographical differentiation between Hispaniola and Cuba (Table 1 and Table 2), these associations cannot be included in any of the alliances described for the island of Cuba. We therefore propose two new alliances: All. Rondeletio ochraceae-Clusion roseae, in which the alliance species are Rondeletia ochracea, Turpinia occidentalis, Clusia rosea, Mikania cordifolia, Alchornea latifolia, and Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum motanae as the type association; and all. Rondeletio ochraceae-Didymopanion tremuli, with the species Rondeletia ochracea, Didymopanax tremulus, Psychotria guadalupensis, and Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis as the type association.

2.2. Conservation Status of the Associations

The analysis of the floristic diversity of the relevés shows a predominance of Shannon_T diversity (total diversity) over the diversity of non-endemic and endemic species, except in the samplings DR15, DR16, and DR17: They have a relative coincidence between Shannon_T and Shannon_Ne due to the low rate of endemic species, with only two species: Bactris plumeriana and Clidemia umbellata.

The diversity rate for characteristic species (Shannon_Ca) tends to be high compared to companion species (Shannon_Co), except in DR3, which has a value of Shannon_Co = 1.099 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Shannon diversity by 17 relevé from Dominican Republic (DR).

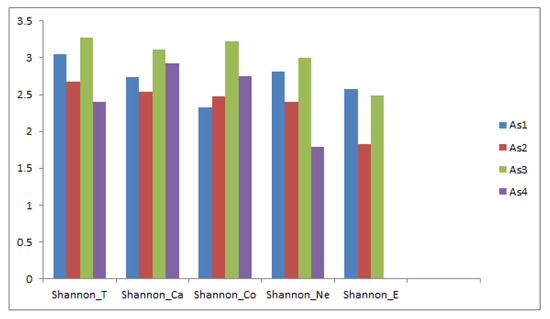

In the comparative analysis of the diversity among the four associations using the average diversity values for each relevé, it can be seen that association As4 has a Shannon_E = 0 due to an almost total lack of endemic species. This association also has low values for total diversity and non-endemic species, with 44.2% trees, 22.9% shrubs, 13.1% climbing plants, and 16.3% herbs, as it appears from the study of biotypes of the phytosociological table; whereas the other associations have a greater diversity. The Shannon_Ca value is higher than the Shannon_Co in the four associations except for As3; however, the values are similar due to a tendency to ingression by companion species from neighbouring communities (Table 5, Figure 5).

Table 5.

Diversity analysis of each of the four plant associations.

Figure 5.

Shannon diversity values (T, Ca, Co, Ne, E) (Shannon_T = total diversity; Shannon_Ca = characteristic community species diversity; Shannon_Co = companion community species diversity; Shannon_Ne = non-endemic species diversity; Shannon_E = endemic species diversity). As1: Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis. As2: Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum motanae. As3: Hyeronimo dominguensis-Magnolietum hamorii. As4: Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae.

3. Discussion

Although the diversity of the Caribbean territories has high diversity and a high rate of endemism [27], this diversity is similar to that existing in neighboring territories in South America (Colombia, Venezuela) [41,42]. There is a great difference of botanical families among the territories of Amazonia, Orinoco, and the Caribbean, but sharing families such as Buxaceae, Achatocarpaceae, and Nelumbonaceae [43], or Melastomataceae [20]: territories that present similar vegetation from the physiognomic point of view, but very different in its floristic composition [44,45,46,47].

On the island of Hispaniola, in all cases there is a high diversity of trees, among which it is particularly worth noting the endemics Magnolia pallescens Urb. & Ekm., Hyeronima montana A. Liogier, Magnolia hamorii Howard, Hyeronima domingensis Urb., Malpighia macracantha Ekm. & Nied., and Bactris plumeriana Mart. These are therefore plant communities with an endemic character that require protection measures. But it is also very important to know the dynamics of the species that characterize these plant communities, as some of them, when introduced into new geographical areas with different modalities and for different purposes, can invade the local communities, causing significant ecological damage [48]. It is evident that native species (N) have a larger distribution area, and are capable of using different ecological niches. Therefore, in the face of climatic, anthropic, and other kinds of changes, these species can expand relegating other more stenoic ones, as occurs with the endemic ones. Although all four associations are of great interest to conservation, the two best conserved associations have the highest rate of endemics, and are precisely the ones located in the Bahoruco–Hottense and central biogeographical sectors [19,21], which concurs with the previous floristic studies [1,3,11,49]. However, the areas exposed to greater environmental impact, as is the case of biogeographical sectors such as the Cordillera Oriental range which are subjected to significant human pressure, have less floristic diversity and a lower number of endemic species. No significant differences can be seen between the relevés in the Shannon diversity index, whose values range between DR3 with indexes of Sh = 2.451, and DR12 with higher values of Sh = 3.972 (Table 4); this does not imply that DR3 is poorly conserved [27], but simply that there is an almost complete predominance of the faithful species Prestoea montana, which has a high cover and very few companion species. However, relevé DR12 contains many individuals with low cover and a high rate of companion species. The low rate of endemisms in As4 represented by relevés DR15, DR16, and DR17 in the Cordillera Oriental range is the result of significant anthropic action owing to population density.

All these results are according to Cano Ortiz et al. [50].

Syntaxonomical Checklist for the Cloud Forest of Hispaniola

- Cyrillo-Weinmannietea pinntae Borhidi 1996

- Cyrillo-Weinmannietalia pinnatae Borhdi 1996

- Rondeletio ochraceae-Clusion roseae Cano, Cano–Ortiz & Veloz all. nova hoc loco

- Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum motanae Cano, Cano–Ortiz & Veloz ass. nova hoc loco

- Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae Cano, Cano–Ortiz & Veloz ass. nova hoc loco

- Ocoteo-Cyrilletea racemiflorae Borhidi 1996

- Ocoteo cuneatae-Magnolietalia cubensis Borhidi & Muñiz in Borhidi 1996

- Rondeletio ochraceae-Didymopanion tremuli Cano, Cano–Ortiz & Veloz all. nova hoc loco

- Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis Cano, Cano–Ortiz & Veloz ass. nova hoc loco

- Hyeronimo dominguensis-Magnolietum hamorii Cano, Cano–Ortiz & Veloz ass. nova hoc loco

4. Materials and Methods

Study Area

The island of Hispaniola, with an area of 76,484 km2, and Cuba, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico are the largest islands in the Caribbean region. The geological origin of the mountains on the island dates from the Cretaceous and Oligocene–Miocene era, with the exception of the intramountain valleys formed during the Quaternary period due to the deposit of materials [51]. There is a predominance of calcareous materials with a karstic character, marbles, limestones, and Quaternary deposit materials, and a large central nucleus of siliceous materials with serpentine outcrops [20,21,22]. The island has a mountainous relief with several mountain chains such as the Oriental, Central, and Septentrional ranges, and sierras such as Bahoruco and Niebla. The steep slopes, the lack of access in certain areas, and the strong anthropic action in others pose a great difficulty for the study of these territories. The northwest-southwest orientation of the mountains and the prevailing direction of the Atlantic winds explains the existence of a permanent sea of clouds, which gives rise to high rainfall on north-northeast-facing slopes. All inventories carried out are located on slopes ranging between 15–40% and are exposed to the humid winds of the Atlantic Ocean. For the coverage in %, the dominant species of the tree vegetation have been taken into account: a study we carried out during three years of sampling (June 2005–June-July 2006 and 2007) as part of our participation in three AECI projects.

This study is focused on the humid-hyper-humid forests in the Dominican Republic (DR) on the island of Hispaniola. Vegetation samples were taken in areas of high rainfall such as the Cordillera Central and Oriental ranges and the Sierra de Bahoruco, selecting sampling plots with an area of 500–2000 m2. Due to the scarcity of vegetation studies, we analyzed the previous works in territories of Cuba [31,32,37]. For the dynamic-catenal landscape study we took into account the criteria of [52,53]. An Excel© table was created with 483 rows (species) × 12 columns (tables containing 67 relevés: 35 for Cuba and 32 for Dominican Republic) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Plant communities studied and number of relevés for each.

A statistical treatment (clustering) was applied to separate the communities described for Cuba from those of Hispaniola. The flora of the 67 relevés of Cuba and Hispaniola allows us to establish a clear floristic differentiation between both islands. The statistical treatment was done by adapting the Van der Maarel conversion [54] and substituting the abundance–dominance indexes with synthetic indexes with the following equivalence: I = 3, II = 4, III = 5, IV = 6, V = 7. Once the indexes were converted, a cluster analysis was applied using the Jaccard distance, marking the distance between the associations studied. After separating the forests in the Dominican Republic (DR) from those of Cuba based on the Jaccard distance, an Excel© table was created with the vegetation relevés from the DR, and a Euclidean distance cluster analysis and a DCA were applied to obtain the different types of forests present in the DR. For this study, the statistical packages PAST (PAleontological STatistics software package for education and data analysis, v. 2.17c. Paleontological Museum, University of Oslo, Sars gate1, 0562 Oslo, Norway)© (Palaeontological Association,) and CAP3 (Community Analysis Package, PISCES Conservation Ltd. IRC House, The Square, Pennington, Lymington Hants., SO41 8GN United Kingdom)© were used.

Regarding the statistical analysis, we used 6 plant associations described in rainy environments in Cuba with a total of 35 relevés (Table 6) and 6 plant communities in the Dominican Republic with a total of 32 relevés, among which 17 were made by us. With the 12 plant communities, we made a synthetic table and, as we previously mentioned, we transformed the synthetic indices with Van der Maarel [54], with the aim of applying a cluster analysis. The Euclidean distance was not chosen since it was only used to see the similarity between two territories (Cuba and the Dominican Republic). Subsequently, an Excel© table was made exclusively with the 17 inventories carried out in the field, and we had already applied Euclidean distance, since we wanted to see the separation between the cloud forest communities, which we confirmed with a DCA analysis.

Once the 4 types of forests were separated, the phytosociological tables and the synthetic table were elaborated: this reflects the floristic difference between the 4 plant associations. For the inclusion of associations in their biogeographic units, we followed Cano–Ortiz et al. [28].

To differentiate some plant communities from others, we followed the phytosociological method of Braun–Blanquet [55] and Gehu and Rivas–Martínez [56], and we used the dynamic-chain studies by Rivas–Martínez [53]. The great floristic differentiation between the districts and biogeographical sectors established in Cano et al. [21] and Cano–Ortiz et al. [28], also with field work, is essential for the phytosociological study.

The criterion for separating syntaxa of different ranks is the distribution and ecology of the species. Obviously the most stenoic species characterize syntaxa of lower rank and the eurioics to higher syntaxonomic ranks; thus, the associations present a district or biogeographic sector distribution, while the higher rank syntaxa have a subprovince, province, superprovince, subregion, and biogeographic region distribution. For this reason, we based our investigation on previous biogeography studies carried out by us [20,21,28]. For the proposal of new syntaxa, the ICPN (International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature) is followed [57].

The floristic study of phytosociological relevés has been verified with the work of Liogier [58] and with the herbarium specimens of the Jardín Botánico Nacional Dr. Rafael M. Moscoso of Santo Domingo (JBSD—acronym according to Thiers [59]), where the new collected specimens are also preserved.

Once the description of the 4 plant associations were made, we planned to find out the degree of conservation: for this we chose to apply the Shannon–Webeaver index or the H’ index. This measures specific diversity applying the method revealed by Cano–Ortiz et al. [29], which takes into account the relationship between the total diversity of species, the diversity of characteristics and companions. In this relationship, it is clear that each community will be better conserved, and the less its diversity of companions and the greater its diversity of characteristics, the closer it will be to total diversity. To calculate the H index, the statistical package PAST (PAleontological STatistics)© was used [60].

5. Conclusions

This study in the Dominican Republic reveals the existence of different types of rainforest that are clearly differentiated by their floristic, biogeographical, and bioclimatic composition. This broadleaved forest or rainforest is frequent in the Sierra de Bahoruco and the Cordillera Central, Septentrional, and Oriental ranges due to the increased rainfall in these areas caused by the impact of moisture-laden Atlantic winds. Differences in soil and biogeography have conditioned a rich and different flora. The Cordillera Central range—geologically the oldest, and with a siliceous character—is home to rainforests of Magnolia pallescens and forests of Prestoea montana (As1 and As2) in humid–hyper-humid areas; whereas the associations As3 in Bahoruco and As4 in the Cordillera Oriental range also develop in humid environments but on soil substrates. This leads us to propose four new syntaxa with the rank of association and two new alliances.

Considering the published works on Cuba, Venezuela, and Colombia already reported in the references, there are differences between these territories and the Dominican Republic. The study on the degree of conservation of the four described associations reveals a low diversity compared to other territories (Cuba, Venezuela, Colombia). Within the study territory (Dominican Republic), As4 is the worst conserved due to strong anthropic action, which has affected the rate of endemism with a Shannon_E value = 0. This association presents 27 characteristic tree species and 2 epiphytic species, of which only one is endemic, compared to 31 companion species of shrubs, herbs, and climbers.

These differences in terms of diversity and conservation status are due to the strong anthropic action that some territories present, such as the Eastern Cordillera (Dominican Republic), being this is an area dedicated mainly to livestock and agriculture, which caused deforestation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.O., C.M.M., and E.C.; data curation, A.C.O., C.M.M., and E.C.; formal analysis, A.C.O. and E.C.; funding acquisition, E.C.; investigation, A.C.O. and E.C.; methodology, A.C.O., C.M.M., and E.C.; project administration, E.C.; resources, A.C.O., C.M.M., C.J.P.G., R.Q.C., J.C.P.F., and E.C.; software, J.C.P.F. and E.C.; supervision, C.M.M. and E.C.; validation, A.C.O., C.M.M., C.J.P.G., R.Q.C., J.C.P.F., and E.C.; visualization, A.C.O., C.M.M., and E.C.; writing—original draft, A.C.O., C.M.M., and E.C.; writing—review & editing, A.C.O., C.M.M., C.J.P.G., R.Q.C., J.C.P.F., and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This investigation was carried out with financial resources of the research group RNM: 211 of the Junta de Andalucia (Spain) and with an AECI project.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the anonymous reviewers and to the Editor for their help in improving our paper. We are also very grateful to Pru Brooke Turner (MA Cantab.) for the English translation of this article and to the University of INTEC and to the Jardín Botánico Nacional de Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) for their most valuable support. This manuscript has been released as a Pre-Print at: Biorxiv 543892; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/543892 2019.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Association Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis.

Table A1.

Association Hyeronimo montanae-Magnolietum pallescentis.

| N° rel. | 4 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° order | DR1 | DR2 | DR4 | DR5 | DR6 | |||

| Altitude | 1481 | 1474 | 1473 | 1441 | 1465 | |||

| Area in m2 × 10 | 200 | 100 | 200 | 50 | 200 | |||

| Cover ratio In % | 100 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Xn in m. | 15 | 15 | 10 | 4 | 20 | |||

| Characteristics of the association and higher units | Family | Biotype | Status | |||||

| Magnolia pallescens Urb. & Ekm. | Magnoliaceae | A | E | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Cyathea furfuracea Baker | Cyatheaceae | A | N | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Chionanthus domingensis Lam. | Oleaceae | A | N | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Gonocalyx tetrapterus A. Liogier | Ericaceae | Tr | E | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Hyeronima montana A. Liogier | Euphorbiaceae | A | E | + | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Didymopanax tremulus Krug. & Urb. | Araliaceae | A | E | 5 | 2 | 3 | - | 5 |

| Persea oblongifolia Kopp. | Lauraceae | A | E | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Arthrostylidium multispicatum Pilger | Poaceae | Tr | E | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Rondeletia ochracea Urb. | Rubiaceae | A | E | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Alsophila minor (D.C. Eaton) R.M. Tryon | Cyatheaceae | A | N | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Tabebuia vinosa A. Gentry | Bignoniaceae | A | E | 1 | + | 1 | 1 | + |

| Ditta maestrensis Borhidi | Euphorbiaceae | A | N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Smilax populnea Kunt var. horrida O.E. Schulz | Smilacaceae | Tr | N | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | + |

| Ilex macfadyenii (Walp.) Rehder | Aquifoliaceae | A | N | 1 | 3 | + | + | + |

| Clusia clusioides (Griseb.) D’Arcy | Clusiaceae | A | N | + | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Cyrilla racemiflora L. | Cyrillaceae | A | N | 2 | 2 | 3 | - | 2 |

| Vaccinium racemosum (Vahl) Wilbur & Luteyn | Ericaceae | Tr | N | 2 | 3 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Cinnamomum alainii (C.K. Allen) A. Liogier | Lauraceae | A | E | - | + | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Marcgravia rubra A. Liogier | Marcgraviaceae | Tr | E | 1 | 1 | 2 | - | 2 |

| Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R. Br. | Myrsinaceae | A | N | 1 | 2 | + | + | - |

| Pinguicula casabitoana J. Jiménez | Lentibulariaceae | Ep | E | + | + | 1 | - | - |

| Vriesea sintenisii (Baker) L.B. Smith & Pitt. | Bromeliaceae | Ep | N | - | - | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Ocotea nemodaphne Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | + | 1 | - | - | 2 |

| Brunellia comocladifolia H. & B. | Brunelliaceae | A | N | 1 | + | - | - | - |

| Ocotea leucoxylon (Sw.) Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | 1 | - | - | - | + |

| Schradera subsessilis Steyermark | Rubiaceae | Tr | N | 1 | - | 2 | - | - |

| Mikania venosa A. Liogier | Asteraceae | Tr | E | - | 2 | - | - | + |

| Chaetocarpus domingensis Proctor | Euphorbiaceae | A | E | - | - | 1 | - | + |

| Odontadenia polyneura (urb.) Wood. | Apocynaceae | Tr | E | - | - | - | + | + |

| Myrsine nubicola A. Liogier | Myrsinaceae | A | E | + | - | - | - | - |

| Prestoea montana (Grah.) Nichol | Arecaceae | A | N | - | 2 | - | - | - |

| Weinmannia pinnata L. | Cunoniaceae | A | N | - | + | - | - | - |

| Odontosoria uncinella (Kunze) Fée | Polypodiaceae | Tr | N | - | + | - | - | - |

| Persea krugii Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | - | - | - | 1 | - |

| Epidendrum carpophorum Barb. Rodr. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + | - |

| Pleurothallis domingensis Cogn. | Orchidaceae | Ep | E | - | - | - | + | - |

| Byrsonima lucida (Mill.) L.c. rich. | Malpighiaceae | A | N | - | - | - | + | - |

| Dilomilis montana (Sw.) Summerh. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + | - |

| Companions species | ||||||||

| Styrax ochraceus Urb. | Styracaceae | Ar | E | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Palicourea alpina (Sw.) DC. | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | + |

| Torralbasia cuneifolia (C. Wright) Krug. & Urb. | Celastraceae | Ar | N | - | + | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Macrocarpaea domingensis Urb. | Gentianaceae | Ar | E | 1 | - | + | 1 | 2 |

| Psychotria domingensis Jacq. | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | + |

| Polygala fuertesii (Urb.) Blake | Polygalaceae | Ar | E | 1 | - | 2 | 5 | - |

| Psychotria guadalupensis (DC.) Howard | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | + | 3 | - | - | + |

| Baccharis myrsinites (Lam.) Pers. | Asteraceae | Ar | N | - | - | 1 | 1 | + |

| Bocconia frutescens L. | Papaveraceae | Ar | N | + | - | - | - | - |

| Clidemia umbellata (Miller) L.O. Wms. | Melastomataceae | Ar | N | + | - | - | - | - |

| Vernonia buxifolia (Cass.) Less. | Asteraceae | Ar | N | + | - | - | - | - |

| Cestrum coelophlebium O. E. Schulz | Solanaceae | Ar | E | - | + | - | - | - |

| Lyonia alainii W. Judd. | Ericaceae | Ar | E | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Clidemia hirta (L.) D. don | Melastomataceae | Ar | N | - | - | + | - | - |

| Renealmia jamaicensis (Gaertn.) Horan var. puberula (Gagn.) Maas | Zingiberaceae | H | N | + | 3 | 1 | 1 | + |

| Lobelia rotundifolia Juss. | Campanulaceae | H | E | 1 | - | 1 | - | + |

| Gleychenia bifida (Willd.) Spreng. | Gleycheniaceae | H | N | 2 | - | 1 | - | |

| Blechnum occidentale L. | Blechnaceae | H | N | + | - | 1 | - | + |

| Lycopodium clavatum L. | Lycopodiaceae | H | N | - | - | 1 | - | + |

| Peperomia hernandifolia (Vahl) A. Dietr. | Piperaceae | H | N | - | - | - | + | - |

| Lycopodium cernuum L. | Lycopodiaceae | H | N | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Odontosoria aculeata (L.) J. Sm. | Polypodiaceae | H | N | - | - | - | + | - |

| Isachne rigidifolia (Poir.) Urb. | Poaceae | H | N | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Machaerina cubensis (Kük.) T. Koyama | Cyperaceae | H | N | - | - | - | - | + |

Sites sampled. DR1—Casabito. Ébano Verde (19340280E/2105321N). DR2—Casabito (19340299E/2105967N). DR4—Casabito. Ébano Verde (19340283N/2106095N). DR5—Casabito. Ébano Verde (19340288E/2106283N). DR6—Palmerito. Ébano Verde (19340165E/2106429N). Tree = A; Shrub = Ar; Climber = Tr; Epiphyte = Ep; Herb = H; Native = N; Endemic = E; Xn = Average height of the dominant species.

Table A2.

Association Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum motanae.

Table A2.

Association Cyatheo furfuracei-Prestoetum motanae.

| N° rel. | 6 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 17 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° order | DR3 | DR7 | DR8 | DR9 | DR10 | ||||

| Altitude | 1097 | 1373 | 1377 | 1251 | 1200 | ||||

| Area in m2× 10 | 200 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 50 | ||||

| Cover ratio In % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Xn in m. | 20 | 9 | 9 | 15 | 7 | ||||

| Characteristics of the association and higher units | Family | Biotype | Status | ||||||

| Prestoea montana (Grah.) Nichol | Arecaceae | A | N | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| Arthrostylidium multispicatum Pilger | Poaceae | Tr | E | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Cyathea furfuracea Baker | Cyatheaceae | A | N | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | + | |

| Dendropanax arboreus (L.) Dcne & Planch. | Araliaceae | A | N | 2 | - | + | + | + | |

| 3Alsophila minor (D.C. Eaton) R.M. Tryon | Cyatheaceae | A | N | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | |

| Ocotea leucoxylon (Sw.) Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | - | + | + | + | + | |

| Coccoloba wrightii Lindau | Polygnonaceae | A | N | - | 1 | + | 2 | + | |

| Alchornea latifolia Sw. | Euphorbiaceae | A | N | 2 | + | - | 1 | - | |

| Turpinia occidentalis (Sw.) G. Don | Staphyleaceae | A | N | - | - | + | 2 | 1 | |

| Brunellia comocladifolia H. & B. | Brunelliaceae | A | N | 2 | - | - | - | + | |

| Byrsonima lucida (Mill.) L.c. Rich. | Malpighiaceae | A | N | - | 1 | - | - | + | |

| Calyptrantes selleanus Urb. & Ekm. | Myrtaceae | A | E | - | - | - | - | + | |

| Cecropia screberiana Miq. | Moraceae | A | N | 2 | - | 2 | - | - | |

| Dichaea glauca (Sw.) Lindley | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | + | - | + | 1 | |

| Epidendrum anceps Jacq. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Epidendrum jamaicense Lindl | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Epidendrum ramosum Jacq. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | + | + | - | |

| Epidendrum ramosum Jacq. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Grammitis asplenifolia (L.) Proctor | Grammitidaceae | Ep | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Guatteria blainii (Griseb.) Urb. | Annonaceae | A | N | - | + | - | - | + | |

| Guzmania monostrachya (Sw.) Rusby | Bromeliaceae | Ep | N | - | + | + | - | - | |

| Malpighia macracantha Ekm. & Nied. | Malpighiaceae | A | E | - | - | - | 2 | - | |

| Jacquiniella globosa (Jacq.) Schlechter | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Didymopanax tremulus Krug. & Urb. | Araliaceae | A | E | 1 | - | - | - | - | |

| Miconia mirabilis (Aubl.) L.O. Willians | Melastomataceae | A | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Exostema elliptica Griseb. | Rubiaceae | A | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Microgramma piloselloides L. | Polypodiaceae | Ep | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Camparettia falcata Poepp. & Endl. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Antrophyum lanceolatum (L.) Kaulf. | Adiantaceae | Ep | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R. Br. | Myrsinaceae | A | N | - | + | - | - | + | |

| Niphidium crassifolium (L.) Lell. | Polypodiaceae | Ep | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Oncidium variegatum (Sw.) Sw. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Ophioglossum palmatum L. | Ophioglossaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Phlebodium aureum (L.) J. Smith | Polypodiaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Pleurothallis domingensis Cogn. | Orchidaceae | Ep | E | - | + | - | - | + | |

| Pothuya nudicaulis (L.) Regel | Bromeliaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Rondeletia ochracea Urb. | Rubiaceae | A | E | - | + | - | 3 | - | |

| Companions species | |||||||||

| Myrcia splendens (Sw.) DC. | Myrtaceae | Ar | N | - | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |

| Psychotria domingensis Jacq. | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | - | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Tabebuia bullata A. Gentry | Bignoniaceae | Ar | E | 1 | - | + | + | + | |

| Blechnum tuerckheimii A. Brause | Blechnaceae | H | E | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | - | |

| Psychotria guadalupensis (DC.) Howard | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | - | 3 | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Renealmia jamaicensis (Gaertn.) Horan var. puberula (Gagn.) Maas | Zingiberaceae | H | N | - | 2 | 2 | - | + | |

| Mikania venosa A. Liogier | Asteraceae | Tr | E | - | - | + | + | 2 | |

| Sagraea fuertesii (Cogn.in Urb.) Alain | Melastomataceae | Ar | E | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | |

| Senecio lucens (Poir) Urb. | Asteraceae | Tr | E | - | - | + | 2 | 1 | |

| Smilax havanensis Jacq. | Smilacaceae | Tr | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Solanum crotonoides Lam. | Solanaceae | Ar | N | - | 1 | - | - | + | |

| Solanum virgatum Lam. | Solanaceae | Ar | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Stigmaphyllon emarginatum (L.) A. Juss. | Malpighiaceae | Tr | N | - | - | - | - | + | |

| Uncinia hamata (L.) Urb. | Cyperaceae | H | N | - | + | + | + | - | |

| Vaccinium racemosum (Vahl) Wilbur & Luteyn | Ericaceae | Tr | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Vitis tiliifolia H. & B. ex Willd. | Vitaceae | Tr | N | - | - | - | - | + | |

| Vittaria lineata (L.) Smith | Pteridaceae | Ep | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Blechnum occidentale L. | Blechnaceae | H | N | - | 1 | 2 | - | + | |

| Cestrum coelophlebium O. E. Schulz | Solanaceae | Ar | E | - | - | - | 1 | + | |

| Cestrum inclusum Urb. | Solanaceae | Ar | E | - | - | 5 | - | - | |

| Cissampelos pareira L. | Menispermiaceae | Tr | N | 1 | - | + | - | - | |

| Commelina elegans Kunth | Commelinaceae | H | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Daphnosis crassifolia (Poir.) Meiss. | Thymelaeaceae | Ar | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Diplazium hastile (Christ.) C. Chr. | Athyriaceae | H | N | - | - | 2 | - | - | |

| Diplazium hians Kuntze | Athyriaceae | H | N | - | - | - | 2 | - | |

| Gleychenia bifida (Willd.) Spreng. | Gleycheniaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - | - | + | |

| Gomedesia lindeniana Berg. | Myrtaceae | Ar | N | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Gyrotaenia myriocarpa Griseb. | Urticaceae | Ar | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Hyptis americana (Poir.) Briq. | Lamiaceae | Ar | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Ichnanthus pallens (Sw.) Munro | Poaceae | H | N | - | 1 | + | + | - | |

| Ipomoea furcyensis Urb. | Convolvulaceae | Tr | E | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Lasianthus lanceolatus (Griseb.) Gómez Maza | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | - | 1 | - | - | - | |

| Lobelia robusta Graham | Campanulaceae | Ar | E | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Lobelia rotundifolia Juss. | Campanulaceae | H | E | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Odontadenia polyneura (urb.) Wood. | Apocynaceae | Tr | E | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Odontosoria uncinella (Kunze) Fée | Polypodiaceae | Tr | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Olyra latifolia L. | Poaceae | H | N | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Palicourea alpina (Sw.) DC. | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | - | + | - | - | + | |

| Peperomia hernandifolia (Vahl) A. Dietr. | Piperaceae | H | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Pilea geminata Urb. | Urticaceae | H | E | - | - | 2 | - | - | |

| Polypodium loriceum L. | Polypodiaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + | - | |

| Pothomorphe peltata (L.) Miquel | Piperaceae | Ar | N | - | - | + | - | - | |

| Mucuna urens (L.) Fawc. & Rendle | Fabaceae | Tr | N | - | + | - | - | - | |

| Myrcia deflexa (Poir) DC. | Myrtaceae | Ar | N | - | - | - | 1 | + | |

Sites sampled. DR3—Río Jatubei (19341984E/2105891N). DR7—Camino Casabito al Arroyazo (10339971E/2105962N). DR8—Bajada Casabito al Centro Fernándo Dominguez (19339590E/2105699N). DR9—Casabito-Arroyazo (Ébano Verde) (19339203E/2105784N). DR10—Near Arroyazo (19339203E/2105785N). Tree = A; Shrub = Ar; Climber = Tr; Epiphyte = Ep; Herb = H; Native = N; Endemic = E; Xn = Average height of the dominant species.

Table A3.

Association Hyeronimo dominguensis-Magnolietum hamorii.

Table A3.

Association Hyeronimo dominguensis-Magnolietum hamorii.

| N° rel. | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° order | DR11 | DR12 | DR13 | DR14 | |||

| Altitude | 1207 | 1239 | 1233 | 1140 | |||

| Area in m2× 10 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | |||

| Cover ratio In % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Xn in m. | 25 | 15 | 20 | 15 | |||

| Characteristics of the association and higher units | Family | Biotype | Status | ||||

| Magnolia hamorii Howard | Magnoliaceae | A | E | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Hyeronima domingensis Urb. | Euphorbiaceae | A | E | 5 | 2 | 5 | + |

| Cyathea fulgens C. Chr. | Cyatheaceae | A | N | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R. Br. | Myrsinaceae | A | N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Didymopanax tremulus Krug. & Urb. | Araliaceae | A | E | + | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Brunellia comocladifolia H. & B. | Brunelliaceae | A | N | 2 | 1 | - | - |

| Prestoea montana (Grah.) Nichol | Arecaceae | A | N | + | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Beilschmiedia pendula (Sw.) Hemsl. | Lauraceae | A | N | 2 | - | 1 | - |

| Ocotea leucoxylon (Sw.) Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | - | 1 | 1 | + |

| Calyptrantes selleanus Urb. & Ekm. | Myrtaceae | A | E | + | 1 | 1 | - |

| Weinmannia pinnata L. | Cunoniaceae | A | N | 2 | 2 | 2 | - |

| Pleurothalis ruscifolia (Jaq.) R. Br. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | 1 | 2 | 2 | - |

| Elleanthus cephalotus Garay & Sweet | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | 2 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Elaphoglossum crinitum (L.) C. Chr. | Lomariopsidaceae | Ep | N | 1 | 1 | + | - |

| Columnea sanguinea Urb. | Gesneriaceae | ArEp | N | 1 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Elaphoglossum latifolium (Sw.) J. Sm. | Lomariopsidaceae | Ep | N | 2 | 2 | 2 | - |

| Miconia prasina (Sw.) DC. | Melastomataceae | A | N | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Rondeletia ochracea Urb. | Rubiaceae | A | E | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Alchornea latifolia Sw. | Euphorbiaceae | A | N | 1 | - | - | + |

| Dendropanax arboreus (L.) Dcne & Planch. | Araliaceae | A | N | 1 | - | - | - |

| Miconia mirabilis (Aubl.) L.O. Willians | Melastomataceae | A | N | - | 1 | - | + |

| Epidendrum ramosum Jacq. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | 2 | + |

| Ophioglossum palmatum L. | Ophioglossaceae | Ep | N | + | 1 | - | - |

| Ocotea acarina C.K. Allen | Lauraceae | A | E | - | - | 2 | 1 |

| Chionanthus domingensis Lam. | Oleaceae | A | N | - | - | 2 | - |

| Ocotea nemodaphne Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | - | 1 | - | - |

| Ilex macfadyenii (Walp.) Rehder | Aquifoliaceae | A | N | - | 1 | - | - |

| Niphidium crassifolium (L.) Lell. | Polypodiaceae | Ep | N | 2 | - | - | - |

| Polypodium loriceum L. | Polypodiaceae | Ep | N | 1 | - | - | - |

| Epidendrum jamaicense Lindl | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | 2 | - | - |

| Phlebodium aureum (L.) J. Smith | Polypodiaceae | Ep | N | 1 | - | - | - |

| Dichaea glauca (Sw.) Lindley | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | 2 | - | - |

| Epidendrum carpophorum Barb. Rodr. | Orchidaceae | Ep. | N | - | - | 1 | - |

| Ocotea floribunda (Sw.) Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | - | - | - | 1 |

| Anacheilium cochleatum (L.) Hoffm. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | - | - | + |

| Ocotea patens (Sw.) Nees | Lauraceae | A | N | - | - | - | + |

| Guarea guidonea Sleumer | Meliaceae | A | N | 1 | - | - | - |

| Maxillaria coccinea (Jacq.) L.O. Wms. | Orchidaceae | Ep | N | - | 2 | - | - |

| Ocotea foeniculacea Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | - | 1 | - | - |

| Cecropia screberiana Miq. | Moraceae | A | N | - | - | - | 1 |

| Beilschmiedia pendula (Sw.) Hemsl. | Lauraceae | A | N | - | - | - | 1 |

| Companions species | |||||||

| Psychotria domingensis Jacq. | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Mikania venosa A. Liogier | Asteraceae | Tr | E | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Gomedesia lindeniana Berg. | Myrtaceae | Ar | N | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Lasianthus bahorucanus Zanoni | Rubiaceae | H | E | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Columnea domingensis (Urb.) Wiehler | Gesneriaceae | Ar | E | 2 | 1 | + | 1 |

| Odontosoria uncinella (Kunze) Fée | Polypodiaceae | Tr | N | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Mecranium ovatum Cog. | Melastomataceae | Ar | E | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vriesea tuercheimii (Mez.) L.B. Smith | Bromeliaceae | H | E | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Nephrolepis biserrata (Sw.) Schott | Lomariopsidaceae | H | N | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Peperomia hernandifolia (Vahl) A. Dietr. | Piperaceae | H | N | + | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Psychotria guadalupensis (DC.) Howard | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | 2 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Myrcia deflexa (Poir) DC. | Myrtaceae | Ar | N | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Lomariposis sorbifolia (L.) Feé | Lomariopsidaceae | H | N | 1 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Hedyosmum domingense Urb. | Chloranthaceae | Ar | E | - | 1 | 1 | + |

| Lomariposis sorbifolia (L.) Feé | Lomariopsidaceae | H | N | 2 | 2 | - | 1 |

| Renealmia jamaicensis (Gaertn.) Horan var. puberula (Gagn.) Maas | Zingiberaceae | H | N | 2 | 1 | 2 | - |

| Vaccinium racemosum (Vahl) Wilbur & Luteyn | Ericaceae | Tr | N | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Macrocarpaea domingensis Urb. | Gentianaceae | Ar | E | - | 2 | 1 | - |

| Polygala fuertesii (Urb.) Blake | Polygalaceae | Ar | E | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Arthrostylidium multispicatum Pilger | Poaceae | Tr | E | 3 | 2 | - | - |

| Torralbasia cuneifolia (C. Wright) Krug. & Urb. | Celastraceae | Ar | N | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Mucuna urens (L.) Fawc. & Rendle | Fabaceae | Tr | N | 1 | - | - | 2 |

| Schlegelia brachyantha Griseb. | Schlegeliaceae | Tr | N | 1 | - | - | + |

| Meriania involucrata (Desv.) Naud. | Melastomataceae | Ar | E | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Hypolepis hispaniolica Mason | Polypodiaceae | Tr | E | - | 2 | - | 1 |

| Arthrostylidium sarmentosum Pilger | Poaceae | Tr | N | - | 2 | 2 | - |

| Blechneum fragile (Liebm.) Morton & Lellinger | Blechnaceae | H | N | - | 2 | 2 | - |

| Ilex tuerckheimii Loes. | Aquifoliaceae | Ar | E | - | - | + | - |

| Cordia dependens Urb. & Ekm. | Boraginaceae | Ar | E | - | - | - | + |

| Passiflora rubra L. | Passifloraceae | Tr | N | - | - | - | + |

| Eupatorium odoratum L. | Asteraceae | Ar | N | - | - | - | + |

| Mikania cordifolia (L.) Willd. | Asteraceae | Tr | N | - | - | - | 1 |

| Psychotria liogieri Sateyerm | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | - | - | - | + |

| Marattia kaulfussii J. Smith | Marattiaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - | - |

| Asplenium radicans L. | Aspleniaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - | - |

| Smilax domingensis Willd. | Smilacaceae | Tr | N | + | - | - | - |

| Leandra limoides (Urb.) W. Judd & Skean | Melastomataceae | Ar | E | - | 1 | - | - |

| Hillia parasitica Jacq. | Rubiaceae | Tr | N | - | 2 | - | - |

| Cestrum daphnoides Griseb. | Solanaceae | Ar | E | - | 1 | - | - |

| Tibouchina longifolia (Vahl) Baill. | Melastomataceae | Ar | N | - | 1 | - | - |

| Clidemia umbellata (Miller) L.O. Wms. | Melastomataceae | Ar | N | - | - | - | + |

| Schradera subsessilis Steyermark | Rubiaceae | Tr | E | 1 | - | - | - |

| Marcgravia rubra A. Liogier | Marcgraviaceae | Tr | E | - | - | 1 | - |

| Lobelia rotundifolia Juss. | Campanulaceae | H | E | - | 1 | - | - |

| Blechnum occidentale L. | Blechnaceae | H | N | - | - | - | + |

| Cissampelos pareira L. | Menispermiaceae | Tr | N | - | - | - | + |

| Myrcia splendens (Sw.) DC. | Myrtaceae | Ar | N | - | - | - | 3 |

| Ichnanthus pallens (Sw.) Munro | Poaceae | H | N | - | - | - | 1 |

| Sagraea fuertesii (Cogn.in Urb.) Alain | Melastomataceae | Ar | E | - | 1 | - | - |

Sites sampled. DR11—Sierra Bahoruco. El Cachote (19267592E/2002124N). DR12—Sierra Bahoruco. El Cachote (19268161E/2002764N). DR13—Sierra Bahoruco. Prox. el Cachote (19268152E/2002964N). DR14—Km. 3 del poblado Cachote (19268736E/2000217N). Tree = A; Shrub = Ar; Climber = Tr; Epiphyte = Ep; Herb = H; Native = N; Endemic = E; Xn = Average height of the dominant species.

Table A4.

Association Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae.

Table A4.

Association Ormosio krugii-Prestoetum montanae.

| N° rel. | 13 | 15a | 15b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° order | DR15 | DR16 | DR17 | |||

| Altitude | 519 | 541 | 530 | |||

| Area in m2× 10 | 200 | 200 | 200 | |||

| Cover ratio In % | 75 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Xn inm. | 15 | 12 | 15 | |||

| Characteristics of the association and higher units | Family | Biotype | Status | |||

| Prestoea montana (Grah.) Nichol | Arecaceae | A | N | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Cecropia screberiana Miq. | Moraceae | A | N | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Alchornea latifolia Sw. | Euphorbiaceae | A | N | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Miconia mirabilis (Aubl.) L.O. Willians | Melastomataceae | A | N | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Miconia prasina (Sw.) DC. | Melastomataceae | A | N | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Guarea guidonea Sleumer | Meliaceae | A | N | + | 4 | 4 |

| Cyathea arborea (L.) J.E. Smith | Cyatheaceae | A | N | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Turpinia occidentalis (Sw.) G. Don | Staphyleaceae | A | N | 1 | + | 1 |

| Clusia rosea Jacq. | Clusiaceae | A | N | 1 | + | + |

| Ocotea globosa (Aubl.) Schlecht. & Cham. | Lauraceae | A | N | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Casearea arborea (L.C. Rich.) Urb. | Flacourtiaceae | A | N | 1 | 1 | + |

| Oreopanax capitatus (Jacq.) Decne. & Planch. | Araliaceae | A | N | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Didymopanax morototoni (Aubl.) Decne. & Planch | Araliaceae | A | N | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Byrsonima spicata (Cav.) Kunth | Malpighiaceae | A | N | + | 1 | 1 |

| Buchenavia tetraphylla (Aubl.) R. A. Howard | Combretaceae | A | N | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sloanea berteriana Choisy | Elaeocarpaceae | A | N | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ormosia krugii Urb. | Fabaceae | A | N | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Miconia serrulata (DC.) Naud. | Melastomataceae | A | N | + | + | 1 |

| Bactris plumeriana Mart. | Arecaceae | A | E | - | 1 | 1 |

| Myrsine coriacea (Sw.) R. Br. | Myrsinaceae | A | N | 1 | 1 | - |

| Ocotea leucoxylon (Sw.) Mez | Lauraceae | A | N | - | 2 | 2 |

| Inga fagifolia (L.) Willd. ex Benth. | Mimosaceae | A | N | - | + | + |

| Inga vera Willd. | Mimosaceae | A | N | - | + | + |

| Cupania americana L. | Sapindaceae | A | N | 2 | - | - |

| Hirtella triandra Sw. | Chrysobalanaceae | A | N | + | - | - |

| Miconia racemosa (Aubl.) DC. | Melastomataceae | A | N | 1 | - | - |

| Zantoxylum martinicensis (Lam.) DC. | Rutaceae | A | N | 1 | - | - |

| Guzmania monostrachya (Sw.) Rusby | Bromeliaceae | Ep | N | + | - | - |

| Microgramma piloselloides L. | Polypodiaceae | Ep | N | + | - | - |

| Companions species | ||||||

| Cnemidaria horrida (L.) K. Presl | Cyatheaceae | Ar | N | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Pytirogramma calomelanos (L.) Link | Polypodiaceae | H | N | 1 | + | + |

| Ipomoea tiliacea (Willd.) Choisy | Convolvulaceae | Tr | N | + | 2 | 2 |

| Mucuna urens (L.) Fawc. & Rendle | Fabaceae | Tr | N | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Solanum torvum Sw. | Solanaceae | Ar | N | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Mikania cordifolia (L.) Willd. | Asteraceae | Tr | N | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Psychotria domingensis Jacq. | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | - | 2 | 1 |

| Pothomorphe peltata (L.) Miquel | Piperaceae | Ar | N | - | 2 | 2 |

| Tibouchina longifolia (Vahl) Baill. | Melastomataceae | Ar | N | 1 | - | + |

| Nepsera aquatica (Aubl.) Naud. | Melastomataceae | Ar | N | 1 | - | + |

| Syngonium podophyllum Schott | Araceae | Tr | N | 2 | + | - |

| Urera baccifera (L.) Gaud. | Urticaceae | Ar | N | - | 2 | 2 |

| Psychotria uliginosa Sw. | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | - | 2 | 2 |

| Coccocypselum herbaceum Aubl. | Rubiaceae | H | N | + | - | - |

| Piper adunculum L. | Piperaceae | Ar | N | 1 | - | - |

| Cissus verticillata (L.) Nicholson & Farris | Vitaceae | Tr | N | 1 | - | - |

| Neurolaena lobata (L.) Cass. | Asteraceae | H | N | + | - | - |

| Triunfetta semitriloba Jacq. | Tiliaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - |

| Clidemia umbellata (Miller) L.O. Wms. | Melastomataceae | Ar | E | 1 | - | - |

| Gleychenia bifida (Willd.) Spreng. | Gleycheniaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - |

| Lycopodium clavatum L. | Lycopodiaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - |

| Ichnanthus pallens (Sw.) Munro | Poaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - |

| Nephrolepis multiflora (Roxb.) Jarret | Lomariopsidaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - |

| Smilax domingensis Willd. | Smilacaceae | Tr | N | + | - | - |

| Mimosa pudica L. | Mimosaceae | H | N | 1 | - | - |

| Palicourea crocea (Sw.) Schultes | Rubiaceae | Ar | N | 1 | - | - |

| Urena lobata L. | Malvaceae | Ar | N | 1 | - | - |

| Hedychium coronarium Koen. | Zingiberaceae | H | I | 1 | - | - |

| Solanum jamaicense Mill. | Solanaceae | Ar | N | 1 | - | - |

| Entada gigas (L.) Fawc. & Rendle | Fabaceae | Tr | N | + | - | - |

Sites sampled: DR15—El Trece (eastern range) (19Q0489524/2092418). DR16—Dieciseis de Mitche (19Q0486735/2092513). DR17—Near Dieciseis de Mitche (19Q0486736/2092514). Tree = A; Shrub = Ar; Climber = Tr; Epiphyte = Ep; Herb = H; Native = N; Endemic = E; Introduced = I; Xn = Average height of the dominant species.

References

- García, R.; Mejía, M.; Peguero, B.; Jiménez, F. Flora endémica de la sierra de Bahoruco, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 2001, 12, 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Ángeles, I.; Clase, T.; Peguero, B. Flora y vegetación del Parque Nacional El Choco, Sosúa, provincia Puerto Plata, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 2005, 14, 10–55. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, A.; Jiménez, F.; Höner, D.; Zanoni, T. La flora y la vegetación de la loma Barbacoa, Cordillera Central, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 1997, 9, 84–116. [Google Scholar]

- Höner, D.; Jiménez, F. Flora vascular y vegetación de la loma la Herradura (Cordillera Oriental), República Dominicana. Moscosoa 1994, 8, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- May, T. Regeneración de la Vegetación arbórea y arbustiva en un terreno de cultivos abandonado durante 12 años en la zona de bosques húmedos montanos (Reserva Científica Ébano Verde, Cordillera Central, República Dominicana). Moscosoa 1994, 8, 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- May, T. Fases tempranas de la sucesión en un bosque nublado de Magnolia pallescens después de un incendio (Loma Casabito, Reserva Científica de Ebano Verde, Cordillera Central, República Dominicana). Moscosoa 1997, 9, 117–144. [Google Scholar]

- May, T. Tres años de obervaciones fenológicas en el bosque nublado de Casabito (Reserva científica Ebano Verde, Cordillera Central, República Dominicana). Moscosoa 1998, 10, 164–178. [Google Scholar]

- May, T. Respuesta de la vegeteción en un calimetal de Dicranopteris pectinata después de un fuego, en la parte oriental de la Cordillera Central, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 2000, 11, 113–132. [Google Scholar]

- May, T. Composition, structure and diversity in broadleaved cloud forests in the Ebano Verde scientific reserve (Cordillera Central range, Dominican Republic). Moscosoa 2007, 15, 156–176. [Google Scholar]

- May, T.; Peguero, B. Vegetación y flora de la loma el Mogote, Jarabacoa, Cordillera Central, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 2000, 11, 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, M.; García, R.; Jiménez, F. Sub-región fitogeográfica Barbacoa-Casabito: Riqueza florística y su importancia en la conservación de la flora de la isla Española. Moscosoa 2000, 11, 57–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, M.; Jiménez, F. Flora y vegetación de la loma la Humeadora, Cordillera Central, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 1998, 10, 10–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía, M.; Pimentel, J.; García, R. Árboles y Arbustos de la región Cársica de los Haitises, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 2011, 17, 90–114. [Google Scholar]

- Veloz, A. Flora y vegetación del Monte Jota, Sierra de Bahoruco, Provincia Independencia, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 2007, 15, 206–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hager, J.; Zanoni, T. La vegetación natural de la República Dominicana: Una nueva clasificación. Moscosoa 1993, 7, 39–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Navarro, G.; Penas, A.; Costa, M. Biogeographic map. of Sourh America. A preliminary survey. Int. J. Geobot. Res. 2011, 1, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, T. La flora y la vegetación de loma Diego de Ocampo, Cordillera Septentrional, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 1990, 6, 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni, T.; Mejía, M.M.; Pimentel, J.D.; García, R.G. La flora y vegetación de los Haitises, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 1990, 6, 46–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, E.; Cano Ortiz, A. Establishment of biogeographic areas by distributing endemic flora and habitats (Dominican Republic, Haiti, R.). In Global Advances in Biogeography; Stevens., L., Ed.; InTechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Veloz Ramirez, A.; Cano Ortiz, A.; Esteban Ruiz, F.J. Distribution of Central American melastomataceae: Biogeographical análisis of the Caribbean Islands. Acta Bot. Gall. 2009, 156, 527–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cano, E.; Veloz Ramirez, A.; Cano Ortiz, A. Contribution to the biogeography of the Hispaniola (Dominican Republic, Haiti). Acta Bot. Gall. 2010, 157, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Veloz Ramirez, A.; Cano Ortiz, A. Phytosociological study of the Pinus occidentalis forests in the Dominican Republic. Plant Biosyst. 2011, 145, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Cano Ortiz, A.; Del Río González, S.; Alatorre Cobos, J.; Veloz, A. Bioclimatic map of the Dominican Republic. Plant Soc. 2012, 49, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Cano Ortiz, A.; Veloz, A. Contribution to the knowledge of the edaphoxerophilous communities of the Samana Peninsula (Dominican Republic). Plant Soc. 2015, 52, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Veloz, A. Contribution to the knowledge of the plant communities of the Caribbean-Cibensean sector in the Dominican Republic. Acta Bot. Gall. 2012, 159, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Spampinato, G.; Veloz, A.; Cano, E. Vegetation of the dry bioclimatic areas in the Dominican Republic. Plant Biosyst. 2015, 149, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Cano, E. Distribution patterns of endemic flora to define hotspots on Hispaniola. Syst. Biodivers. 2016, 14, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Cano, E. Biogeographical Areas of Hispaniola (Dominican Republic, Republic of Haiti). In Plant Ecology—Traditional Approaches to Recent Trends; Yousaf, Z., Ed.; InthechOpen: London, UK, 2017; pp. 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Bartolomé Esteban, C.; Quinto-Canas, R.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Del Río González, S.; Cano, E. Advances in the knowledge of the vegetation of Hispaniola (Caribbean Central America). In Vegetation; Sebata, A., Ed.; InthechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Del Río González, S.; Cano, E. Diversity and conservation status of mangrove communities in two areas of Mesocaribea biogeographic region. Curr. Sci. India 2018, 115, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhidi, A. Phytogeography and Vegetation Ecology of Cuba; Academiai Kiado: Budapest, Hungary, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Borhidi, A. Phytogeography and Vegetation Ecology of Cuba; Academiai Kiado: Budapest, Hungary, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Samek, V. Regiones Fitogeográficas de Cuba; Serie No 15; Academia de Ciencias de Cuba: Havana, Cuba, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, O.J. Estudio sinecológico de las pluvisilvas submontanas sobre rocas del complejo metamórfico. Foresta Veracruzana 2005, 7, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, O.J.; Acosta Cantillo, F. Fitocenosis en los bosques siempre verdes de Cuba Oriental. I. Ocoteo-Phoebietum elongatae en los mogotes de la grán meseta de Guantánamo. Foresta Veracruzana 2010, 12, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, O.J.; Acosta Cantillo, F. Fitocenosis en los bosques siempre verdes de Cuba Oriental. II. Guareo guidoniae-Zanthoxyletum martinicensis en Sagua Baracoa. Foresta Veracruzana 2010, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, O.J.; Acosta Cantillo, F. Fitocenosis en los bosques siempre verdes de Cuba Oriental. III. Pruno-Guareetum guidoniae en la sierra Maestra. Foresta Veracruzana 2011, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Sinopsis biogeográfica, bioclimática y vegetacional de América del Norte. Fitosociologia 2004, 41, 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Loidi, J. Bioclimatology of the Iberian Peninsula. Itinera Geobot. 1999, 13, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo, A.E.; Francis, J.K.; Frangi, J.L. Prestoea Montana (R. Graham) Nichols. Sierra Palm; US Department of Agriculte, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experimental Station: New Orleans, LA, USA, 1998; pp. 420–450. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Ch, J.O. La biodiversidad de Colombia: Significado y distribución regional. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. Ex. Fis. Nat. 2015, 39, 176–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, W. Flora and Vegetation des Avila-National Parks Venezuela (Kuestenkordillere) unter Besonderer Beruecksichtigung der Nebelwaldstufe; Dissertationes Botanicae: Stuttgard, Germany, 1998.

- Rangel-Churio, J.O. La riqueza de las plantas con flores de Colombia. Caldasia 2015, 37, 279–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuatrecasas, J. Aspectos de la vegetación natural de Colombia. Rev. Acad. Col. Cs. Ex. Fis. Nat. 1958, 7, 306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann, R.W. Bosques andinos del sur de Ecuador, clasificación, regeneración y uso. Rev. Peru. Biol. 2005, 12, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleef, A.M. The Vegetation of the Páramos of the Colombian Cordillera Oriental; Dissertationes Botanicae: Stuttgard, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Cleef, A.M.; Rangel-Churio, J.O.; Van der Hammen, T.; Jaramillo, M.R. La Vegetación de las Selvas del Transecto Butirica; Van der Hammen, T., Ruiz, P.M., Eds.; Studies on Tropical Andean Ecosystems: Vaduz, Liechtenstein, 1984; Volume 2, pp. 267–406. [Google Scholar]

- Musarella, C.M. Solanum torvum Sw. (Solanaceae): A new alien species for Europe. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2020, 67, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, R.; Mejía, M.; Zanoni, T. Composición florística y principales asociaciones vegetales en la Reserva Científica de Evano Verde, Cordillera Central, República Dominicana. Moscosoa 1994, 8, 86–130. [Google Scholar]

- Cano Ortiz, A.; Musarella, C.M.; Quinto Canas, R.; Piñar Fuentes, J.C.; Pinto Gomes, C.J.; Cano, E. The cloud forest in the Dominican Republic: Diversity and conservation status. bioRxiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollat, H.; Wagner, B.M.; Cepek, P.; Weiss, W. Mapa Geológico de la República Dominicana 1:250,000; Die Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe: Hannover, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Sánchez Mata, D.; Costa, M. North American boreal and western temperate forest vegetation. Syntaxonomical synopsis ot the potential natural plant communities of North America, II. Itinera Geobot. 1999, 12, 5–326. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Notions on dynamic-catenal phytosocilogy as a basis of landscape science. Plant Biosyst. 2005, 139, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Maarel, E. Transformation of cover-abundance values in phytosociology and its effects on community similarity. Vegetatio 1979, 39, 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Fitosociología: Bases Para el Estudio de las Comunidades Vegetales; Blume: Madrid, Spain, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Gehu, J.M.; Rivas Martínez, S. Nociones Fondamentales de Phytosocilogie; Dierschke, H., Ed.; Syntaxonomie: Cramer, Vaduz, 1981; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, H.E.; Moravecm, H.; Theurillat, J.P. International Code of Phytosociological Nomenclature. J. Veg. Sc. 2000, 11, 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liogier, A.H. La Flora de la Española; Jardín Botánico Nacional Dr. Rafael Ma. Moscoso: Santo Dominogo, República Dominicana, 1996–2000; Volume I-IX. [Google Scholar]

- Thiers, B. Index Herbariorum: A Global Directory of Public Herbaria; New York Botanical Garden’s Virtual Herbarium. Available online: http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/ (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Paul, D.R. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).