Abstract

Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn, known as bracken fern, is considered a poisonous plant due to its toxic substances. This species contains toxic substances and enzymes: thiaminase and an anti-thiamine substance, which cause thiamine deficiency syndrome. Prunasin induces acute cyanide poisoning. Ptaquiloside causes haematuria, retinal atrophy, immunodeficiency, and lymphoproliferative disorders. It also induces carcinogenesis in livestock, and in animals and human cell lines. Ptaquiloside has been found in the milk of cattle, goats, and sheep that grazed on P. aquilinum in pastures. Ptaquiloside is water-soluble and washes away from the plants into the soil with rainwater. It has been found in streams and groundwater wells. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified bracken fern as a Group 2B carcinogen. However, P. aquilinum has long been used as a folk remedy in various regions. Several studies have identified its medicinal value and bioactive compounds with potential pharmacological activity. Pterosin B and its analogues exhibit anti-osteoarthritis, anti-Alzheimer’s disease, neuroprotective, anti-cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, anti-diabetic, and smooth muscle relaxant properties. Ptaquiloside also induces apoptosis in certain human cancer cell lines and acts as an anticancer agent. Therefore, pterosins and ptaquiloside have therapeutic properties. Other compounds, including some flavonoids and polysaccharides, act as antimicrobial, antifungal, and immunomodulatory agents. Based on their structures, it is possible to develop medicines with these therapeutic properties, particularly those containing pterosins and ptaquiloside. However, more research is needed on their use in medicinal treatments.

1. Introduction

Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn, commonly called bracken or eagle fern, belongs to the Dennstaedtiaceae family. The genus of the Pteridium contains about 20 species, including P. aquilinum [1,2,3,4]. It is one of the oldest fern genera, with fossils dating back to the Eocene period, which occurred between 55 and 33.9 million years ago [5,6]. Pteridium aquilinum is a diploid species with 2n = 108 chromosomes [3,7]. Triploid cytotype populations of P. aquilinum with 2n = 162 chromosomes have also been recorded in various parts of Europe [8,9]. This species exhibits significant genetic diversity and phenotypic plasticity in different geographical regions and is divided into up to 12 subspecies [3,4,7]. It adapts to various environmental conditions, including temperature (low to high), rainfall, humidity, light irradiation, nutrition, soil types, and pH [7,10,11,12]. Due to its genetic diversity and adaptability, P. aquilinum is widely distributed in Europe, North Africa, Eastern Asia, and North and Central America [3,7]. This species thrives in open habitats, such as abandoned agricultural fields, areas burned by fire, grasslands including pastures, and coniferous and deciduous woodlands. It often forms monospecific stands [7,13,14,15] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pteridium aquilinum stand.

As a fern species, the life cycle of P. aquilinum contains a large sporophyte (diploid) phase and a very small prothallium (gametophyte) phase. The prothallium is haploid and develops from spores produced by the sporophyte. The heart-shaped prothallium measures 2–5 mm in width. It produces male and female reproductive organs that generate sperm and egg cells, respectively. After featurization of the sperm and egg, the resulting diploid zygote develops into an embryo. The embryo then grows into a sporophyte [7,16,17]. The sporophyte is the dominant phase of its life cycle. It is commonly referred to as a fern and has the following structures: Fiddleheads grow directly from underground rhizomes and develop into leaves called fronds. The fronds are attached to the rhizomes by long stipes (petioles). The fronds grow between 0.3 and 3 m long. They are bipinnate and divided into pinnae (leaflets). The pinnae are further divided into pinnules. Fertile fronds produce spores in sori (sporangia), which are located on the underside of the pinnules. A single frond can produce up to 300 million spores per year [7,16,17,18]. In cold regions with harsh winters, such as Northern Europe and Eastern Asia, the fronds wither during the winter months. Their extensive, horizontal rhizomes creep underground. These rhizomes can grow up to 5 m long and 0.5 to 4 cm in diameter. They accumulate nutrients, including starch, and contribute to vegetative reproduction. Fine roots arise from the rhizomes. Sporophytes have relatively long lifespans, and their rhizomes can last up to 70 years [7,17] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pteridium aquilinum. (A): Fiddleheads, (B): Frond, (C): Sori (Sporangia).

Pteridium aquilinum has been widely used as food and in folk medicine for a long time [19,20,21,22]. The ancient Greek pharmacologist Pedanius Dioscorides referred to P. aquilinum and several other ferns as having medicinal value in his book “De materia medica”, a pharmacopoeia of medicinal plants [23]. Decoctions made from the rhizomes of P. aquilinum have been used to treat diabetes and chronic disorders of the spleen and stomach. They have also been used to treat malaria and as deworming agents [24,25,26,27,28]. Decoctions made from the rhizome nodules have been used to treat rickets in children, as well as wounds, eczema, dermatitis, and coughs. They have also been used as a laxative [7,19,27]. Due to their antipyretic and diuretic properties, the fronds and rhizomes of this plant have been used to treat hepatitis [29,30]. The plant has also been used as an abortifacient for domestic animals [28,31]. The rhizomes of P. aquilinum contain about 45% starch. For this reason, they have been used as a food source. The rhizomes can be ground into flour and used as an ingredient in bread, cakes, and beer brewing [26,32,33,34,35,36]. The fiddleheads of P. aquilinum have been used as a vegetable in traditional dishes [34,36,37]. They are still available at local markets in East Asia, including China, Korea, and Japan. After proper preparation, they can be eaten as a vegetable or used as an ingredient in cooking. The starch from the rhizomes is also used to make traditional cakes (Figure 3) [29,38].

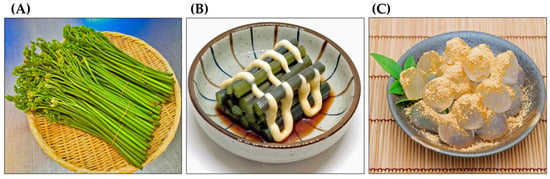

Figure 3.

Pteridium aquilinum as food. (A): Fiddleheads at local markets, (B): Boiled fiddleheads with a dressing served as a vegetable, (C): A sweet cake made from the rhizome starch and soybean powder.

Pteridium aquilinum was used as livestock feed. Dried fronds were used as cattle silage. They were mixed with hay and straw to feed horses and mules. Fresh fronds were used to feed pigs [7,26]. Since the late 19th century, the toxicity of P. aquilinum to livestock has been suspected intermittently [39]. Feeding on P. aquilinum or grazing in fields containing P. aquilinum often causes serious illness or death in livestock. Horses and sheep experience an acute thiamine deficiency, while cattle experience enzootic haematuria. Sheep become blind. Upper alimentary carcinoma occurs in cattle and sheep [7,32,40,41]. Extensive research has identified several toxic substances in P. aquilinum. One of these is ptaquiloside, a nor-sesquiterpene with highly cyanogenic properties. In vivo, it is metabolized into ptaquiloside dienone, which binds to DNA bases, such as adenine and guanine. This binding results in the cleavage and fragmentation of DNA strands. These breaks in DNA strands can induce cancer [42] (Figure 4).

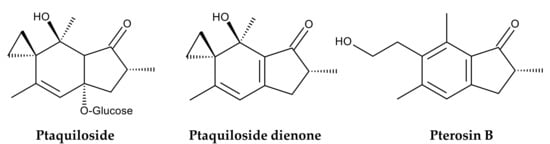

Figure 4.

Compounds identified in Pteridium aquilinum.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified bracken fern as a Group 2B carcinogen based on experimental evidence, indicating that P. aquilinum is possibly carcinogenic to humans [43]. Therefore, P. aquilinum is currently recognized as a poisonous species that threatens not only free-ranging animals but also humans who consume dairy products from livestock that feed on the ferns [41,44,45,46]. However, extracts of P. aquilinum have been shown to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in certain human cancer cell lines [47]. Ptaquiloside also exhibited selective toxicity against human cancer cells compared to noncancer cells [48]. Furthermore, pterosin B, a degradation product of ptaquiloside (Figure 4), suppresses chondrocyte hypertrophy and protects cartilage from osteoarthritis in human cells [49] (Figure 4). Therefore, both pterosin B and ptaquiloside have therapeutic properties. This plant also contains several compounds, including some polysaccharides and flavonoids with antimicrobial, antioxidant, pesticidal, and herbicidal properties [38]. Additionally, donepezil, a substituted indanone, structural analog of pterosin B, has been approved for treating Alzheimer’s disease in the UK and USA [50]. Although consuming P. aquilinum is toxic, medicines with these therapeutic properties can be developed based on the structures of these compounds. Therefore, it is worthwhile to summarize the bioactive compounds identified in P. aquilinum. This review discusses the toxicology and pharmacology of P. aquilinum and related compounds, as well as their modes of action. A combination of online search engines was used to search the literature: Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. The following terms were searched in relation to Pteridium and/or ptaquiloside: toxicity, pharmacology, fodder, livestock, botany, genetic diversity, habitat, ethnobotany, active compound, carcinogen, cyanogenesis, pterosin, analogue, metabolism, mode of action, occurrence, contamination, and environment. We included these research papers as thoroughly as possible. However, we excluded papers with unclear methods.

2. Toxicology

The toxic effects of consuming P. aquilinum, also known as “bracken poisoning” include thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, acute cyanide poisoning, retinal atrophy called as bright blindness, bovine enzootic haematuria, and carcinoma of the upper alimentary tract and other organs [7,32]. However, different animals exhibit different symptoms. In cattle, symptoms of bracken poisoning were observed after they consumed P. aquilinum for three months. These symptoms included bovine enzootic haematuria, bladder tumors, and haemorrhages from the kidneys, mucous membranes, and skin. Other symptoms were leukopenia, hyperplasia of the bile ducts, and fibrous tissue proliferation in the liver [51,52,53,54,55]. In sheep, retinal atrophy was caused by consuming P. aquilinum for four months. This is due to stenosis of blood vessels and degeneration of the rods, cones and outer nuclear layer of the retina [56]. Other symptoms include bone marrow suppression, immunosuppression, urinary tract neoplasia, and thiamine deficiency [57]. In horses, the most apparent symptom of bracken poisoning was thiamine deficiency caused by consuming P. aquilinum for three months [58,59,60]. In rats, consuming P. aquilinum resulted in enlarged and congested livers, renal anemia of kidney, haemorrhages, and bladder tumors [61,62]. Other symptoms include mild edema in the brain, increased intestinal secretions, and degenerative changes in hepatocytes in the liver [63]. In mice, the administration of aqueous extracts of P. aquilinum reduced natural killer (NK) cell activity and cellular immune responses and induced lung carcinogenesis [64,65]. Bracken poisoning has also been observed in other animals, including rabbits, pigs, and guinea pigs [66,67,68,69,70]. As mentioned in the “Introduction”, the young fronds or fiddleheads, of P. aquilinum are used as a vegetable in traditional East Asian cuisine. It is believed that adequate treatments, such as soaking the fiddleheads in boiling water containing wood ash or sodium bicarbonate, remove their poisonous properties [71,72,73]. The following components have been identified as the cause of “bracken poisoning”.

2.1. Anti-Thiamine Factors

Thiamine (vitamin B1) is an essential nutrient that maintains proper cellular function in humans and animals. It acts as a coenzyme in the metabolism of proteins, fats, and carbohydrates and plays a role in the central and peripheral nervous systems [74]. Thiamine deficiency leads to Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, and cardiovascular and neurological complications. These complications include heart failure, neuropathy, ataxia, paralysis, and delirium [75]. Descriptions of thiamine deficiency in horses were reported more than 70 years ago. Affected horses exhibited weight loss, ataxia, convulsions, and bradycardia after consuming P. aquilinium. Death typically occurs within two to ten days of symptom onset [59,60,76,77]. Consuming P. aquilinum has also been reported to cause thiamine deficiency in other animals including pigs, rats, and sheep [46,58,78].

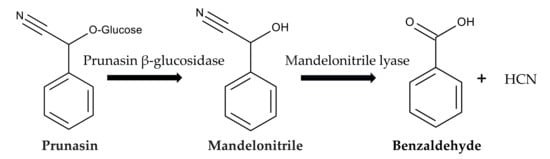

Pteridium aquilinium contains two types of thiaminase: thiaminase I and thiaminase II. Thiaminase I is more active than thiaminase II in P. aquilinium [79]. Thiaminase I (thiamine pyridinylase, EC 2.5.1.2) catalyzes the following reaction: thiamine + pyridine → heteropyrithiamine + 5-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole [80]. Thiaminase II (aminopyrimidine aminohydrolase, EC 3.5.99.2) catalyzes the following reaction: thiamine + H2O → 5-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole + 4-amino-2-methyl-5-pyrimidinemethanol + H+ [81]. Therefore, consuming P. aquilinum results in reduced thiamine levels due to the degradation of thiamine by thiaminases I and II. This can lead to thiamine deficiency syndromes. Additionally, the extracts of P. aquilinum exhibited anti-thiamine activity in vitro by reducing thiamine concentrations. The active constituent was identified as 5-O-caffeoylshikimic acid [82]. This compound may be responsible for the anti-thiamine activity of the P. aquilinum extracts. However, its role in causing thiamine deficiency remains unclear (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Anti-thiamine factors of Pteridium aquilinum.

2.2. Cyanogenic Factor

Pteridium aquilinium contains prunasin, a cyanogenic glycoside or a mandelonitrile glycoside [83,84,85]. Cyanogenic glycosides are toxic, and consuming these compounds has been linked to the development of various diseases due to their production of hydrogen cyanide (HCN). Hydrogen cyanide is produced through enzymatic degradation caused by plant β-glycosidases following wounding of plant tissues or by bacterial activity in the animal gut.

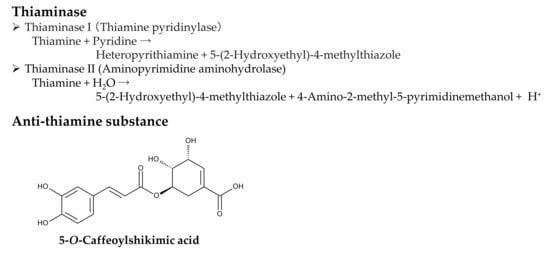

After ingesting P. aquilinium, prunasin is actively absorbed by sodium-dependent monosaccharide transporters embedded in their jejunal epithelial tissue of animals [86,87]. Then, prunasin β-glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.118) breaks it down into D-glucose and mandelonitrile. Mandelonitrile is further catalyzed by mandelonitrile lyase (EC 4.1.2.10), which produces benzaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide [88,89]. The generated hydrogen cyanide causes acute cyanide poisoning. Symptoms include low blood pressure, rapid pulse, rapid breathing, convulsions, twitching, dizziness, stupor, headaches, mental confusion, vomiting, and diarrhea [86,87] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Prunasin cyanogenesis.

The concentration of prunasin in P. aquilinium was found to range from 10.4 to 61.3 mg (0.04 to 0.21 mmol) per g of fresh plant tissue [85]. Based on the metabolic pathway [88,89], one prunasin molecule (molar mass, 295.291 g) can release one hydrogen cyanide molecule (molar mass, 27.0253 g). Therefore, the maximum theoretical production rate of hydrogen cyanide is 5.7 mg (0.21 mmol) per g of fresh plant tissue.

The concentration of prunasin in the other blacken species P. arachnoideum was 1.8–107.7 mg (0.006–0.36 mmol) per g of dry tissue. The maximum liberation rate of hydrogen cyanide was measured at 47.9 μg per min per g of dry tissue [90]. This equates to 2.9 mg (0.11 mmol) of hydrogen cyanide released per g of dry tissue in one hour. Based on the metabolic pathway [88,89] and prunasin concentration, the maximum theoretical production rate of hydrogen cyanide is calculated to be 9.7 mg (0.36 mmol) per g of dry plant tissue. Therefore, 29.8% of the maximum rate (calculated as 2.9 mg out of 9.7 mg) was released within one hour. Applying this release rate to P. aquilinium, which has a maximum theoretical rate of 5.7 mg (0.21 mmol) hydrogen cyanide per g of fresh plant tissue, as described in the previous paragraph, results in the release of 1.7 mg of hydrogen cyanide per g of fresh tissue in one hour. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) established an acute reference dose (ARfD) of 20 μg of cyanide per kg of body weight [91]. This level causes acute health effects regardless of the food source [91,92]. Therefore, consuming P. aquilinium potentially releases enough hydrogen cyanide to cause cyanide poisoning.

Additionally, prunasin cyanogenesis increased the mortality rate of the sawfly larvae Strongylogaster impressata and Strongylogaster multicincta when they fed on P. aquilinium [83]. Prunasin cyanogenesis also reduced the activity of adults of the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria [84]. Therefore, prunasin may also act as a defense mechanism against herbivorous insects.

2.3. Carcinogenic Factor

2.3.1. Identification of Ptaquiloside as a Carcinogenic Factor

Studies have shown that cattle that consume P. aquilinum develop bladder carcinoma [68,93]. Oral administration of P. aquilinum to rats has been shown to induce tumors in their urinary bladders and intestines [94,95,96]. Applying an extract of urine from cattle fed P. aquilinum to the skin of mice resulted in the growth of papilloma-type excrescences [97]. These findings indicate that P. aquilinum contains certain carcinogenic substances. For over 20 years, phytochemical studies have been carried out to identify the carcinogens in several blacken species.

Boiling water extracts of P. aquilinum were found to induce tumors in the urinary bladder and ileum of rats [72]. Ptaquiloside, an illudane-type nor-sesquiterpene glucoside, was then isolated from these boiling water extracts and identified as a carcinogenic compound [98,99] (Figure 4). Oral administration of ptaquiloside to rats has been shown to cause tumors in their urinary bladders, mammary glands, and intestines [61,100]. Intravenous and catheter administration of ptaquiloside to sheep has been shown to induce retinal atrophy [56]. Intraperitoneal administration of ptaquiloside to mice induced B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders and early-stage urothelial lesions [101]. Oral administration of ptaquiloside reduced natural killer (NK) cell activity and cellular immune responses in mice [102,103]. Additionally, a histological investigation revealed that the chronic symptom of bovine enzootic haematuria is accompanied by the development of multiple bladder tumors [54,104]. Therefore, ptaquiloside can cause retinal atrophy, lymphoproliferative disorders, immunosuppressive effects, bovine enzootic haematuria, and cancer.

Ptaquiloside has been found in several other bracken species, including Pteridium esculentum and Pteridium revolutum. These species are native to the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia and the South Pacific, including New Zealand and Australia [105,106,107]. Ptaquiloside has also been found in Pteridium arachnoideum and Pteridium caudatum, which are native to Mexico and tropical and subtropical America [108,109,110,111]. The concentration of ptaquiloside in these bracken species was similar to that in P. aquilinum and depended on harvest time and location. Based on these findings, it is possible that the remaining bracken species contain ptaquiloside as well. Ptaquiloside has also been found in species from other fern families, including several Pteris and Onychium species belonging to the Pteridaceae family [112,113,114]. Some ancient ferns may have acquired the ptaquiloside metabolic pathway before their families evolved. However, the evolutionary process of fern species that contain ptaquiloside remains unclear.

2.3.2. Occurrence of Ptaquiloside

The concentration of ptaquiloside in P. aquilinium plants varied from that reported in the literature. The concentration of ptaquiloside in the fronds ranged from 0.03 to 13.3 mg per g of dry plant tissue [115,116,117,118,119]. The ptaquiloside concentration in the rhizomes was reported to be between 0.007 and 0.657 mg per g of dry plant tissue [108,115]. The ptaquiloside concentration in the spores was determined to be 0.003 mg per g of dry plant tissue [120]. Significant regional variation in ptaquiloside concentration was observed in P. aquilinium populations in the UK [121,122]. Pteridium aquilinium collected in Denmark has a higher concentration of ptaquiloside than that collected in Sweden and Finland [122]. These results imply that climate and/or geographic factors may influence the production of ptaquiloside in P. aquilinium. The stage of development of the fronds also affects the concentration. Young fronds contain more ptaquiloside than mature ones [115,119,123]. The production of ptaquiloside is affected by the availability of nutrients, particularly phosphate, in the soil. A high concentration of phosphate in the soil increases the production [117]. Therefore, reported differences in ptaquiloside concentration may be due to variations in harvesting time, location, and nutrient conditions. The method used to determine the concentration also affects the results [115,116,117,118,119].

Jersey-Holstein half-breed cows were fed 6 kg of fresh P. aquilinum daily. The ptaquiloside content of this feed ranged from 2400 to 10,000 mg. Ptaquiloside was detected in their milk 38 h after feeding. A milk sample from daily milking of 20 L contained 8.6% of the total ptaquiloside intake [124,125]. However, this estimate is quite high compared to others. The ptaquiloside concentration in milk from a dairy farm was estimated to be around 1.5, 1.8, and 1.9 μg per L for cattle, goats and sheep, respectively [126]. Ptaquiloside was also detected in the milk of goats and sheep that frequently grazed on P. aquilinum in several pastures in southern Italy. Concentrations of ptaquiloside ranged from the detection limit to 3.14 μg per L for goats and from the detection limit to 1.63 μg per L for sheep [127]. Although the concentration of ptaquiloside in milk varies by source, these animals excrete a certain amount of ptaquiloside into their milk by consuming P. aquilinum. Since ptaquiloside is carcinogenic, it is important to determine its potential toxicological effects in dairy products.

Due to its water solubility, ptaquiloside in P. aquilinum fronds is easily washed away by rain and leaches into the soil and groundwater. In Danish forests dominated by P. aquilinum, the concentration of ptaquiloside in the soil of the forest floor was 1600 mg per m2. A single rainfall event washed 13.2 mg per m2 (2.5 mg per L) of ptaquiloside into the soil. The concentration of ptaquiloside in soil water was measured between 4.4 and 4.8 μg per L [123,128]. In a small stream draining a P. aquilinum-infested catchment area in the UK, the ptaquiloside concentration was up to 0.06 μg per L. During storm events, this concentration increased to 2.2 μg per L [129]. The concentration of ptaquiloside in groundwater wells (ranging from 8 to 40 m deep) in regions dominated by P. aquilinum in Denmark, Sweden, and Spain was determined. Six of the seven wells containing ptaquiloside were used for drinking water, with concentrations ranging from 0.27 to 0.75 μg per L [130]. Ptaquiloside was detected at all the water abstraction sites examined in Northern Ireland, where P. aquilinum is prevalent. The highest concentration found was 0.67 μg per L in drinking water [131]. Further research is needed to determine the potential toxicological effects of ptaquiloside in drinking water in areas where P. aquilinum grows abundantly.

2.3.3. Metabolism of Ptaquiloside

Ptaquilosin, the aglycone of ptaquiloside, was synthesized artificially from dimethyl (1R,2R)-cyclopentane-1,2-dicarboxylate in 20 steps with a total yielding of 2.9% [132]. However, the biosynthesis of ptaquiloside is not fully understood. It may be synthesized from farnesyl pyrophosphate, which is a precursor of sesquiterpenes. Farnesyl pyrophosphate undergoes cyclization, oxidative cleavage, and glycosylation [133]. The spirocyclopropane ring in ptaquiloside makes the compound susceptible to reactions such as ring opening, rearrangement, and addition [134].

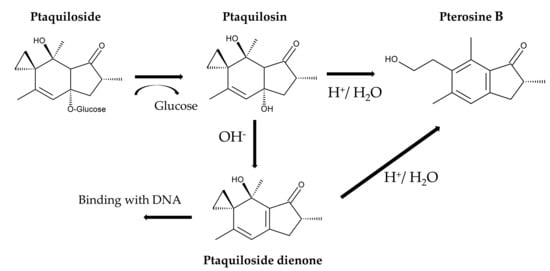

Ptaquiloside degradation in water is pH-dependent [135]. Under neutral conditions, ptaquiloside is relatively stable. Under alkaline conditions, ptaquiloside is attacked by OH− and breaks down into ptaquilosin and glucose. Ptaquilosin then converts into a dienone intermediate, which is highly unstable. This intermediate either covalently binds to DNA molecules or forms pterosin B with water [39,133,136]. Under acidic conditions, protonation and tautomerization occur in the ptaquiloside molecule. The cyclopropane ring of ptaquiloside undergoes nucleophilic attack by H+, which leads to aromatization with glucose elimination, and ring opening of the spirocyclopropane. This results in the formation of pterosin B. This process does not produce a dienone intermediate [41,137,138]. Ptaquiloside degradation was slow at pH 5.5 and increased below pH 4.3. The half-life of ptaquiloside was 170 min at pH 2.0 [139,140]. Additionally, ptaquiloside was metabolized into pterosin B in fresh cattle rumen solution [137] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Ptaquiloside metabolism.

The concentrations of pterosin in the fronds were determined by LC-MS to confirm the metabolism of ptaquiloside in P. aquilinum. The concentrations of ptaquiloside and pterosin B in P. aquilinum fronds were between 0 and 6.3 and between 0 and 0.45 mg per g of dry plant tissue, respectively [119]. Another study using LC-MS quantification found ptaquiloside concentrations ranging from 0 to 13.7 mg per g of dry plant tissue and pterosin B concentrations ranging from 0.004 to 0.73 mg per g of dry plant tissue. The recovery rate for both compounds during the determination process was over 86% [118]. These results suggest the metabolism of ptaquiloside into pterosin B in P. aquilinum fronds. However, the concentrations of these compounds and their ratio vary depending on the sampling location [118,119].

When 0.21 mg of ptaquiloside per kg of body weight were administrated intravenously to cattle, the concentration of ptaquiloside in their plasma decreased rapidly, and fell below the detection limit after 12 h. Conversely, ptaquiloside was detected in their urine shortly after administration. Most of the ptaquiloside excreted into the urine occurred within the first four hours after administration [137]. These results suggest that ptaquiloside is quickly excreted into the urine after entering the bloodstream. When cattle were administrated P. aquilinum powder orally at a dose of 1.6 mg of ptaquiloside per kg of body weight, pterosin B was detected in their plasma 10 min afterward and remained detectable up to 12 h later. The maximum concentration of pterosin B in the plasma was 39.7 μg per L at one hour after administration. Shortly after administration, pterosin B was also detected in the urine of cattle. Up to 7% of the pterosin B equivalent of ptaquiloside was excreted into the urine within 24 h after administration. Ptaquiloside was not detected in the plasma and urine at any time [137]. These findings from the oral administration of P. aquilinum powder suggest that ptaquiloside is rapidly metabolized into pterosin B and not absorbed into the bloodstream. The produced pterosin B may then be quickly absorbed into the bloodstream and excreted in the urine. However, only 7% of the equivalent amount of ptaquiloside was excreted in the urine as pterosin B. The rest is likely metabolized into other compounds, such as ptaquiloside diene, and absorbed by certain organs in cattle. The complete metabolism of ptaquiloside in animals following the oral administration of Peridium aquilinum remains unclear.

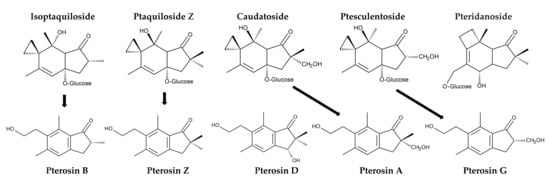

Additionally, P. aquilinum was found to contain several other illudane-type sesquiterpene glucosides, including isoptaquiloside, ptaquiloside Z (methylptaquiloside), caudatoside, and ptesculentoside. It also contains the protoilludane-type sesquiterpene glucoside pteridanoside [109,118,138,141,142,143]. Their corresponding pterosins, pterosin B, pterosin Z, pterosin A, and pterosin G, were identified [118,138,144]. Pterosin D, a C3-hydroxylated form of pterosin Z, was also identified [145]. However, information on the metabolism and biological activities of these analogues is limited (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Ptaquiloside and pterosin analogues identified in Pteridium aquilinum.

2.3.4. Mode of Action of Ptaquiloside

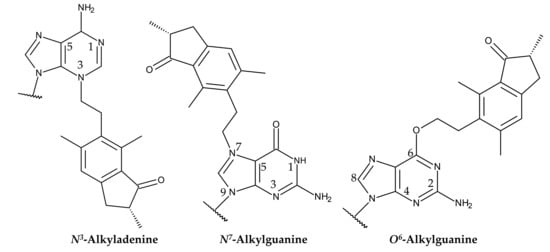

Ptaquiloside contains a spirocyclopropane moiety adjacent to a hydroxy group within its cyclohexene unit. The spirocyclopropane moiety is electrophilic and highly reactive [134]. The carcinogenicity of ptaquiloside is attributed to its dienone metabolites with a spirocyclopropane ring [45,133,136,146]. Ptaquiloside dinene induces alkylation of heterocyclic ribonucleotide bases, particularly adenine and guanine. This results in the formation of N3-alkyladenine and N7-alkylguanine adducts, respectively [147,148]. The formation of O6-alkylguanine adducts has also recently been reported. This alkylation is resistant to the DNA repair enzyme O6-alkylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) [146] (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Structures of alkylated adenine and guanine formed in a reaction with ptaquiloside dienone.

The alkylation is followed by adducted DNA hydrolysis, spontaneous depurination and DNA chain cleavage at the resulting abasic sites via a β-elimination response [136,146]. DNA chain cleavage occurs selectively at the adenine site during the initial response period. Subsequently, cleavage occurs at the guanine site of the DNA strands at a later time [148,149]. The most favorable abasic sites, indicating A, on DNA strands were found to be the base sequences 5′-AAATA and 5′-ATATA [148,149,150]. These abasic sites of the DNA strands can be mutagenic, resulting in the induction of carcinogenesis [45,133,136,146,151].

Ptaquiloside can also target and reduce the functionality of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells [102,152]. These cells are involved in immune function and eliminate infected viral, neoplastic and damaged cells by inducing apoptosis in target cells [153,154]. A reduction in cytotoxic immune function increases the risk of oncogenic viral infection. Mutagenic agents can also accelerate carcinogenesis [155,156]. Ptaquiloside promotes the development of papillomavirus-related cancers of the upper digestive tract, oropharynx, and oral cavity in vivo [157,158]. Therefore, ptaquiloside may work with papillomavirus to induce carcinogenesis. These findings suggest that ptaquiloside induces carcinogenesis by accelerating virus oncogenesis and alkylating DNA. This occurs by reducing the functionality of immune cells, such as natural killer cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. However, the mechanism of ptaquiloside on the reduction in the functionality of these cells remains unclear.

3. Pharmacology

As mentioned in the “Introduction”, P. aquilinum has been used in traditional folk medicines [19,20,21,22]. Several studies have identified its medicinal value and bioactive compounds with potential pharmacological activity.

3.1. Antimicrobial and Antiviral Properties

Oral administration of 400–800 mg per kg of body weight of methanol extracts of P. aquilinum fronds to malaria-infected mice demonstrated an antimalarial effect, reducing Plasmodium berghei parasites by 8.7–79.5% [159]. In an in vitro assay, aqueous ethanol extracts of P. aquilinum rhizomes exhibited SARS-CoV-2 viral growth inhibitory activity with an EC50 of 7.43 μg per mL [160].

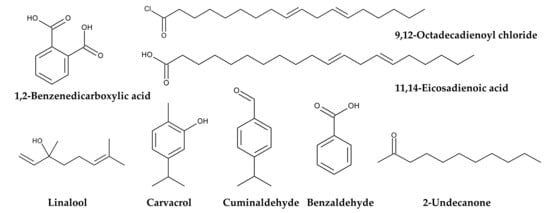

Ethanol, petroleum ether, and/or n-hexane extracts of P. aquilinum fronds exhibited antimicrobial activity against the following bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, and Enterobacter aerogenes [161,162]. Methanol extracts of P. aquilinum fronds exhibited antifungal activity against Candida albicans and Aspergillus niger, and antibacterial activity against S. aureus, Salmonella typhimurium, E. coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The active components identified in the extracts were 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, 9,12-octadecadienoyl chloride, and 11,14-eicosadienoic acid [163]. Essential oil obtained from P. aquilinum fronds exhibited antibacterial activity against Erwinia amylovora, Pectobacterium carotovorum, and Pseudomonas savastanoi. The major components and their respective masses were linalool (10.29%), carvacrol (8.15%), benzaldehyde (5.95%), 2-undecanone (5.32%), and cuminaldehyde (4.57%) [164] (Figure 10). Therefore, the extracts have antimicrobial and antiviral activities, as well as anti-malaria and anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities.

Figure 10.

Antimicrobial compounds identified in Pteridium aquilinum.

3.2. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Properties

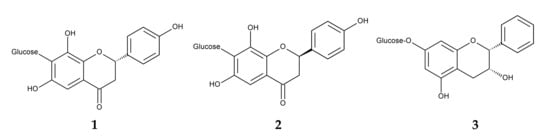

Flavonoid-rich extracts from the fronds of P. aquilinum have demonstrated antioxidant activity [165]. Several flavonoids have been isolated from fronds of P. aquilinum, including the newly identified (S)-4′,6,8-trihydroxyflavanone-7-C-glucoside, (R)-4′,6,8-trihydroxyflavanone-7-C-glucoside, and distenin-7-O-β-d-glucoside. These flavonoids exhibited anti-inflammatory activity [166] (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Anti-inflammatory compounds identified in Pteridium aquilinum. 1: (S)-4′,6,8-Trihydroxyflavanone-7-C-glucoside, 2: (R)-4′,6,8-Trihydroxyflavanone-7-C-glucoside, 3: Distenin-7-O-β-d-glucoside.

The fronds of P. aquilinum contain polysaccharides with antioxidant properties. One such polysaccharide consists of the following sugars and their respective masses: glucose (58.1%), galactose (18.7%), rhamnose (10.2%), mannose (6.8%), and arabinose (6.1%). This polysaccharide has an average molecular weight of 458,000 Da. At a concentration of 800 μg per mL, this polysaccharide exhibited 83.1% DPPH radical scavenging activity in vitro [167]. Another polysaccharide consists of the following sugars at the indicated ratios: mannose (4.81), galactose (4.57), xylose (3.33), fucose (3.26), arabinose (1.58), and rhamnose (1.00). Its average molecular weight is 214,000 Da. This polysaccharide exhibited 98.8% DPPH radical scavenging activity at a concentration of 2000 μg per mL. It also demonstrated significant immunomodulatory activity. It induced the proliferation of mouse monocyte macrophages (RAW264.7) at concentrations ranging from 12.5 to 200 μg per mL, which indicates its immunomodulatory activity [168]. Therefore, these polysaccharides possess antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties. However, the active principles in the flavonoid-rich extracts responsible for the antioxidant activity remain unclear.

3.3. Antidepressant Property

Oral administration of flavonoid-rich P. aquilinum extracts produced antidepressant-like effects in mice. The extracts significantly reduced stress-induced immobility time and increased activity time. The extracts increased serotonin and dopamine levels in the hippocampus of the mice. The extracts also exhibited antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, protecting against neuroinflammation and oxidative damage caused by the underlying factors of chronic stress and depression [169]. Therefore, the extracts have antidepressant properties. However, the active principles among the flavonoids remain unclear.

3.4. Antidiarrheal Property

Oral administration of 245–735 mg per kg of body weight of methanol extracts from P. aquilinum fronds reduced castor oil-induced diarrhea in mice by 74.2–80.5% [170]. The active principles in the methanol extracts that are responsible for the antidiarrheal activity are unclear.

3.5. Anticancer Effects and Ptaquiloside

Dichloromethane extracts from P. aquilinum fronds induced apoptosis in human cancer cell lines, including transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), embryonal carcinoma (NTERA2), and breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) cells. The extracts also induced cell cycle arrest between the G2 and M phases in these cells [47]. Ptaquiloside exhibited anticancer activity against several human cancer cell lines, including colon tumor (HCT116), pancreatic carcinoma (MIA PaCa-2), and neuroblastoma (SK-N-AS) cells. The IC50 values for cytotoxicity against these cancer cells range from 22 to 70 μM. However, ptaquiloside exhibited lower cytotoxic activity against non-cancer human retinal epithelial (ARPE-19) cells, with IC50 values exceeding 100 μM [48]. These results suggest that P. aquilinum extracts and ptaquiloside may have anticancer properties. However, as described in Section 2.3, ptaquiloside is carcinogenic. Further investigation is needed regarding their use in medicinal treatments. This includes determining the appropriate ptaquiloside concentration, identifying the cancer cell lines to which it will be applied, and assessing its safety.

3.6. Pterosin Pharmacology

The ptaquiloside metabolite pterosin B has been reported to exhibit no significant carcinogenic or cytotoxic activity [171,172,173]. Pterosin B and its analogues have demonstrated several pharmacological properties that could be useful in treating osteoarthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, and diabetes. These compounds have also exhibited neuroprotective and smooth muscle relaxant properties.

3.6.1. Anti-Osteoarthritis Property

Osteoarthritis is a common and debilitating joint disorder, affecting over 350 million people worldwide. It is characterized by inflammation, thinning of the articular cartilage, formation of osteophytes, and changes to the subchondral bone [174,175]. Salt-inducible kinase 3 (Sik3) promotes the development of osteoarthritic cartilage in humans [176]. Therefore, Sik3 is a potential target for osteoarthritis treatment. Pterosin B suppressed the Sik3 signaling pathway and inhibited the hypertrophy in human chondrocytes, thereby protecting cartilage from osteoarthritis in vitro [49]. Pterosin B also suppressed the expression of hypertrophy markers, including matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13) and type X collagen, in human osteoarthritic cartilage cells [177]. These findings suggest that pterosin B protects osteoarthritic cartilage by suppressing Sik3 signaling, expression of MMP13, and accumulation of type X collagen. Therefore, pterosin B could be a therapeutic candidate for treating osteoarthritis.

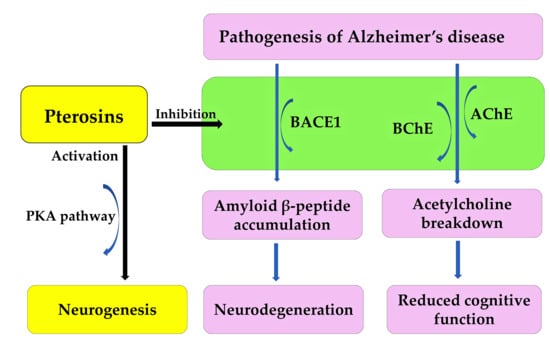

3.6.2. Anti-Alzheimer’s Diseases and Neuroprotective Properties

Alzheimer’s disease is an irreversible, age-related brain disorder, affecting over 55 million people worldwide. It is characterized by memory impairment, behavioral disturbances, and cognitive dysfunction. The accumulation and oligomerization of the amyloid β-peptide in the brain play a significant role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease [178,179]. The overproduction of the amyloid β-peptide is induced by the β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1), which is followed by oligomerization. This process leads to neurodegeneration [180]. Increased BACE1 activity increases the risk of traumatic brain injury, cardiovascular events, and stroke [181]. Therefore, BACE1 is a potential therapeutic target, and BACE1 inhibitors are a possible treatment for Alzheimer’s disease [182]. Decreased levels of acetylcholine in the brain also play a significant role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease [179,183]. Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter involved in cognitive processes. It is broken down by acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE). This breakdown results in a loss of cognitive function [179,183]. These enzymes are also therapeutic targets for treating the cognitive deficits associated with the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease [184].

Pterosin B demonstrated high blood–brain barrier permeability and significantly reduced the secretion of amyloid β-peptide from neuroblastoma cells. It inhibited the activities of BACE1, AChE, and BChE, with respective IC50 values of 29.6, 16.2, and 48.1 μM. Pterosin B is a noncompetitive inhibitor of human BACE1 and BChE, and a mixed-type inhibitor of human AChE. It binds to the active sites of these enzymes [185]. Pterosin B has been shown to have significant neuroprotective activity against glutamate excitotoxicity [173], and to improve cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease by reducing neuroinflammation [186]. Therefore, pterosin B can target multiple therapeutic agents, including BACE1, AChE, and BChE. It can also protect against neuroinflammation during the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Pterosin B analogues, such as pterosin A and Z, inhibited BACE1, AChE and/or BChE activity. However, pterosin B exhibited the greatest inhibitory activity [185]. Additionally, pterosin D significantly improved the cognition and memory of 5xFAD Alzheimer’s model mice by activating the protein kinase A (PKA) pathway [187]. PKA is involved in memory formation and neurogenesis [188]. Together, these findings suggest that pterosin B and its analogues could be used to treat the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Pterosin B acts as an anti-Alzheimer’s disease agent.

3.6.3. Anti-Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy Property

Pterosin B reduced hypertrophy related genes expression, protein synthesis and cell size in a rat embryonic heart-derived cell line (H9c2 cells). Under angiotensin II stimulation, pterosin B reduced the activation of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor by inhibiting the phosphorylation of the PKC-ERK-NF-κB pathway. This pathway consists of protein kinase C (PKC), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [189]. Angiotensin II increases blood pressure and induces cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and arteriosclerosis [190]. These results suggest that pterosin B can inactivate the angiotensin receptor and protect against these conditions. Therefore, pterosin B is a potential therapeutic candidate for treating cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and arteriosclerosis.

3.6.4. Anti-Diabetic Property

Oral administration of pterosin A to diabetic mice improved their hyperglycemia and glucose intolerance, while decreasing their serum insulin levels and insulin resistance. Pterosin A increased AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and GLUT4 translocation from the cytosol to the membrane in skeletal muscles, while decreasing phosphoenolpyruvate carboxyl kinase (PEPCK) expression in the livers of these mice. In human hepatic cells, pterosin A increased intracellular glycogen levels and decreased PEPCK expression and glycogen synthase. In cultured human muscle cells, pterosin A increased glucose uptake and AMPK phosphorylation [191]. Therefore, pterosin A may inhibit glycogenesis in the liver while promoting glucose consumption in muscles. Pterosin A protects rat pancreatic insulin-secreting (RINm5F) cells against oxidative stress and palmitate-induced damage via the AMPK signaling pathway [192]. These results suggest that pterosin A may be an effective therapeutic option for treating diabetes.

3.6.5. Smooth Muscle Relaxant Property

Pterosin Z exhibited smooth muscle relaxant activity by inhibiting calcium influx in potassium-depolarized guinea pig ileum tissues in a concentration-dependent manner, with an EC50 of 1.3 μM. This treatment resulted in muscle relaxation in the tissues [193]. Smooth muscle relaxants relieve tightness and spasms in involuntary muscles in the digestive, respiratory, vascular, and urinary systems. These medications are used to treat conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, high blood pressure, asthma, and cramps [194]. Therefore, pterosin Z has a smooth muscle relaxant property.

4. Conclusions

Pteridium aquilinum contains several toxic enzymes and substances. Thiaminase I and II, and an anti-thiamine substance cause thiamine deficiency syndrome. Prunasin induces acute cyanide poisoning. Ptaquiloside causes haematuria, retinal atrophy, immunodeficiency, and lymphoproliferative disorders, and cancer in livestock, and/or animals and human cell lines. Ptaquiloside was found not only found in P. aquilinum and other Pteridium species, but also in the milk of livestock that grazed P. aquilinum in pastures and in the drinking water of areas where P. aquilinum grows abundantly.

Pteridium aquilinum also contains several pharmacologically active substances. Pterosin B and its analogues exhibit anti-osteoarthritis, anti-Alzheimer’s disease, neuroprotective, anti-cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, anti-diabetic, and/or smooth muscle relaxant properties. Ptaquiloside is not only carcinogenic, but also induces apoptosis and suppresses carcinogenesis in certain human cancer cell lines. Other compounds act as antimicrobial, antifungal, and immunomodulatory agents. Based on their structures, medicines with these therapeutic properties can be developed, particularly those containing pterosins and ptaquiloside. Further investigation is needed regarding their use in medicinal treatments. This includes determining the appropriate concentration, identifying the cell lines to which they will be applied, and evaluating their safety in vitro and in vivo conditions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kew Royal Botanical Garden. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:17210060-1 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- EPPO Global Database. Pteridium aquilinum. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/PTEAQ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Thomson, J.A. Towards a taxonomic revision of Pteridium (Dennstaedtiaceae). Telopea 2004, 10, 793–803. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Dong, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Wen, J.; Schneider, H. How many species of bracken (Pteridium) are there? Assessing the Chinese brackens using molecular evidence. Taxon 2014, 63, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartsburd, P.B.; Perrie, L.R.; Brownsey, P.; Shepherd, L.D.; Shang, H.; Barrington, D.S.; Sundue, M.A. New insights into the evolution of the fern family Dennstaedtiaceae from an expanded molecular phylogeny and morphological analysis. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020, 150, 106881. [Google Scholar]

- Dinan, L.; Lafont, F.; Lafont, R. The distribution of phytoecdysteroids among terrestrial vascular plants: A comparison of two databases and discussion of the implications for plant/insect interactions and plant protection. Plants 2023, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrs, R.H.; Watt, A.S. Biological flora of the British isles: Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. J. Ecol. 2006, 94, 1272–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, E.; Wolf, P.G.; Rumsey, F.J.; Robson, D.J.; Ranker, T.A.; Challinor, S.M. Spatial distribution and reproductive behaviour of a triploid bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) clone in Britain. Ann. Bot. 1993, 72, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekrt, L.; Podroužek, J.; Hornych, O.; Košnar, J.; Koutecký, P. Cytotypes of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) in Europe: Widespread diploids and scattered triploids of likely multiple origin. Flora 2021, 274, 151725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, J.C.; Werth, C.R. A study of spatial features of clones in a population of bracken fern, Pteridium aquilinum (Dennstaedtiaceae). Am. J. Bot. 1993, 80, 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, H.; Sierra, L.M. Pteridium aquilinum: A threat to biodiversity and human and animal health. In Ferns: Biotechnology, Propagation, Medicinal Uses and Environmental Regulation; Marimuthu, J., Fernández, H., Kumar, A., Thangaiahm, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 697–713. [Google Scholar]

- Štefanić, E.; Japundžić-Palenkić, B.; Antunović, S.; Gantner, V.; Zima, D. Botanical characteristics, toxicity and control of bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn). Zb. Veleuc. Rij. 2022, 10, 467–478. [Google Scholar]

- de Silva, Ú.S.R.D.; Matos, D.M.D.S. The invasion of Pteridium aquilinum and the impoverishment of the seed bank in fire prone areas of Brazilian Atlantic forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 2006, 15, 3035–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.S.; Marrs, R.H.; Pakeman, R.J.; Le Duc, M.G. Factors affecting the restoration of heathland and acid grassland on Pteridium aquilinum—Infested land across the United Kingdom: A multisite study. Restor. Ecol. 2008, 16, 553–562. [Google Scholar]

- Amouzgar, L.; Ghorbani, J.; Shokri, M.; Marrs, R.H.; Alday, J.G. Pteridium aquilinum performance is driven by climate, soil and land-use in Southwest Asia. Folia Geobot. 2020, 55, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utah State University. Western Bracken Fern. Available online: https://extension.usu.edu/rangeplants/forbs-herbaceous/western-brackenfern (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- PreachBio. Pteridium aquilinum (bracken fern): Structure, Life Cycle, and Ecological Impact of a Widespread Fern Species. Available online: https://www.preachbio.com/2025/02/pteridium-aquilinum-bracken-fern.html (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Zenkteler, E.; Michalak, K.M.; Nowak, O. Characteristics of indusia and sori in the two subspecies of Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. occurring in Poland. Biodiv. Res. Conserv. 2022, 67, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rymer, L. The history and ethnobotany of bracken. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1976, 73, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwosu, M.O. Ethnobotanical studies on some pteridophytes of southern Nigeria. Econ. Bot. 2002, 56, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, E.; Ichim, M.C. Turning meadow weeds into valuable species for the Romanian ethnomedicine while complying with the environmentally friendly farming requirements of the European Union’s common agricultural policy. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhao, G.; Shama, Z.; Ge, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J. Modeling the future of a wild edible fern under climate change: Distribution and cultivation zones of Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum in the Dadu—Min River Region. Plants 2025, 14, 2123. [Google Scholar]

- Dioscorides. De Materia Medica. Available online: https://ia802907.us.archive.org/16/items/de-materia-medica/scribd-download.com_dioscorides-de-materia-medica.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Mannan, M.M.; Maridass, M.; Victor, B. A review on the potential uses of ferns. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2008, 12, 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, H.K.; Sen, K.; Mukhopadhyay, R. Pteridophytes: Evolutionary boon as medicinal plants. Plant Genet. Res. 2016, 14, 328–355. [Google Scholar]

- Madeja, J.; Harmata, K.; Kołaczek, P.; Karpińska-Kołaczek, M.; Piątek, K.; Naks, P. Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn), mistletoe (Viscum album (L.)) and bladder-nut (Staphylea pinnata (L.))—Mysterious plants with unusual applications. Cultural and ethnobotanical studies. Cultural and ethnobotanical studies. In Plants and Culture: Seeds of the Cultural Heritage of Europe; Morel, J.M., Mercur, A.M., Eds.; EDIPUGLIA: Brussels, Belgium, 2009; pp. 2007–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ibadullayeva, S.; Shiraliyeva, G.S.; Askerova, N.A.; Mammadova, H.C. Pteridophytes: Ethnobotanical use and active chemical composition. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2022, 21, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwiloh, B.I.; Monago-Ighorodje, C.C.; Onwubiko, G.N. Analyses of bioactive compounds in fiddleheads of Pteridium aquilinum L. Kuhn collected from Khana, Southern Nigeria, using gas chromatography-flame ionization detector. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran, X.R.; Geo Vigila, A.V.; Zhang, S.Z.; Feng, S.X.; Liao, W. A review of the use of pteridophytes for treating human ailments. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2018, 19, 85–119. [Google Scholar]

- Giri, P.; Kumari, P.; Sharma, P.; Uniyal, P.L. Ethnomedicinal uses of pteridophytes for treating various human ailments in India. New Vistas Indian Flora 2021, 2, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Viegi, L.; Pieroni, A.; Guarrera, P.M.; Vangelisti, R. A review of plants used in folk veterinary medicine in Italy as basis for a databank. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 89, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, J. A biological hazard of our age: Bracken fern [Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn]—A review. Acta Vet. Hung. 2009, 57, 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov, E.V.; Svetashev, V.I. Edible far Eastern ferns as a dietary dource of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Foods 2021, 10, 1220. [Google Scholar]

- Osawa, Y. Ethnobotanical review of traditional use of wild food plants in Japan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2024, 20, 100. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Zhang, T.; Ren, H.; Zhao, W.; Hong, S.; Ge, Y.; Li, X.; Corke, H. Structural and physicochemical properties of bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) starch. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1201357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useful Tropical Plants Database. Pteridium aquilinum. Available online: https://tropical.theferns.info/viewtropical.php?id=Pteridium+aquilinum (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Wujisguleng, W.; Long, C. Food uses of ferns in China: A review. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Mika, O.J.; Navratilova, Z.; Killi, U.K.; Tlustoš, P.; Patočka, J. Health and environmental hazards of the toxic Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn (bracken fern). Plants 2024, 13, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, K.; Haldar, S.; Boland, W.; Venkatesan, R. Chemical ecology of bracken ferns. In Ferns: Ecology, Importance to Humans and Threats; Nowicki, L., Kowalska, A., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 58–96. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.L.; Lauren, D.R.; Prakash, A.S. Bracken fern (Pteridium) toxicity in animal and human health. In Bracken Fern: Toxicity, Biology and Control; Taylor, J.A., Smith, R.T., Eds.; IBG: Aberystwyth, UK, 2000; pp. 76–85. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa, R.G.; Bastos, M.M.; Oliveira, P.A.; Lopes, C. Bracken-associated human and animal health hazards: Chemical, biological and pathological evidence. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 203, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigoshi, H.; Tanaka, H.; Hirokawa, J.; Mizuta, K.; Yamada, K. Synthesis of analogs of a bracken ultimate carcinogen and their DNA cleaving activities. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 6647–6650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. List of Classifications, Bracken Fern. Available online: https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Avendaño, M. Human carcinogenesis and bracken fern: A review of the evidence. Curr. Medi. Chem. 2002, 9, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, R.M.G.; Povey, A.; Medeiros-Fonseca, B.; Ramwell, C.; O’Driscoll, C.; Williams, D.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Fletcher, M.T.; O’Connor, P.; et al. Sixty years of research on bracken fern (Pteridium spp.) toxins: Environmental exposure, health risks and recommendations for bracken fern control. Environ. Res. 2024, 257, 119274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waret-Szkuta, A.; Jégou, L.; Lucas, M.N.; Gaide, N.; Morvan, H.; Martineau, G.P. A case of eagle fern (Pteridium aquilinum) poisoning on a pig farm. Porc. Health Manag. 2021, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudsari, M.T.; Bahrami, A.R.; Dehghani, H.; Iranshahi, M.; Matin, M.M.; Mahmoudi, M. Bracken-fern extracts induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in certain cancer cell lines. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2012, 13, 6047–6053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.; Allison, S.J.; Phillips, R.M.; Linley, P.A.; Wright, C.W. An efficient method for the isolation of toxins from Pteridium aquilinum and evaluation of ptaquiloside against cancer and non-cancer cells. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahara, Y.; Takemori, H.; Okada, M.; Kosai, A.; Yamashita, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Fujita, K.; Itoh, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Fuchino, H.; et al. Pterosin B prevents chondrocyte hypertrophy and osteoarthritis in mice by inhibiting Sik3. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, L. Outsmarting Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Br. 1998, 34, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.D.; Xu, L.R.; Wen, L.J.; Ma, W.L.; You, S.Z.; He, K.R.; Yang, K.X. Studies on experimental bovine bracken poisoning. Acta Vet Zootech. Sin. 1984, 15, 235–239. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.L. Bracken fern (genus Pteridium) toxicity—A global problem. In Poisonous Plants and Related Toxins; Acamovic, T., Stewart, C.S., Pennycott, T.W., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 224–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell, M.P. Bracken poisoning. Cattle Pract. 2004, 12, 205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, T.; Pinto, C.; Peleteiro, M.C. Urinary bladder lesions in bovine enzootic haematuria. J. Comp. Pathol. 2006, 134, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plessers, E.; Pardon, B.; Deprez, P.; De Backer, P.; Croubels, S. Acute hemorrhagic syndrome by bracken poisoning in cattle in Belgium. Vlaams Diergeneeskd. Tijdschr. 2013, 82, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hirono, I.; Ito, M.; Yagyu, S.; Haga, M.; Wakamatsu, K.; Kishikawa, T.; Nishikawa, O.; Yamada, K.; Ojika, M.; Kigoshi, H. Reproduction of progressive retinal degeneration (bright blindness) in sheep by administration of ptaquiloside contained in bracken. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1993, 55, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegelmeier, B.L.; Field, R.; Panter, K.E.; Hall, J.O.; Welch, K.D.; Pfister, J.A.; Gardner, D.R.; Lee, S.T.; Colegate, S.; Davis, T.Z.; et al. Selected poisonous plants affecting animal and human health. In Haschek and Rousseaux’s Handbook of Toxicologic Pathology, 3rd ed.; Haschek, W.M., Rousseaux, C.G., Wallig, M.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 1259–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, W.C. Bracken Thiaminase—Mediated neurotoxic syndromes. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1976, 73, 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- Riet-Correa, F.; Saures, M.P.; del Mendez, M.C. Intoxications of horses in Brazil. Cienc. Rural 1998, 28, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloni, F.; Cortinovis, C. Plants poisonous to horses in Europe. Equine Vet. Educ. 2015, 27, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Hirono, I.; Fujimoto, M.; Yamada, K.; Yoshida, Y.; Ikagawa, M. Induction of tumors in ACI rats given a diet containing ptaquiloside, a bracken carcinogen. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1987, 79, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, D.S.T.; Joshi, H.C.; Kumar, M.; Singh, G.K. Pathological studies on brackenfern (Pteris aquilina) induced haematuria in calves and rats. Ind. J. Anim. Sci. 1990, 60, 654–656. [Google Scholar]

- Gounalan, S.; Somwanshi, R.; Kumar, R.; Dash, S.; Devi, V. Clinico-pathological effects of bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) feeding in laboratory rats. Ind. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 69, 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, A.O.; Furlan, M.S.; Sakai, M.; Fukumasu, H.; Hueza, I.M.; Haraguchi, M.; Górniak, S.L. Immunomodulatory effects of Pteridium aquilinum on natural killer cell activity and select aspects of the cellular immune response of mice. J. Immunotoxicol. 2009, 6, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caniceiro, B.D.; Latorre, A.O.; Fukumasu, H.; Sanches, D.S.; Haraguchi, M.; Gorniak, S.L. Immunosuppressive effects of Pteridium aquilinum enhance susceptibility to urethane-induced lung carcinogenesis. J. Immunotoxicol. 2015, 12, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.C.; Widdop, B.; Harding, J.D.J. Experimental poisoning by bracken rhizomes in pigs. Vet. Rec. 1972, 90, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringuier, P.P.; Piaton, E.; Berger, N.; Debruyne, F.; Perrin, P.; Schalken, J.; Devonec, M. Bracken fern-induced bladder tumors in guinea pigs. A model for human neoplasia. Am. J. Pathol. 1995, 147, 858. [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick, G.R. Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum)—Toxic effects and toxic constituents. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1989, 46, 147–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khrishna, L.; Dawra, R.K. Bracken fern induced carcinoma in guinea pigs. Indian J. Vet. Pathol. 1994, 18, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gounalan, S.; Somwanshi, R.; Kataria, M.; Bisht, G.S.; Smith, B.L.; Lauren, D.R. Effect of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) and dryopteris (Dryopteris juxtaposita) fern toxicity in laboratory rabbits. Ind. J. Exp. Biol. 1999, 37, 980–985. [Google Scholar]

- Hirono, I.; Shibuya, C.; Shimizu, M.; Fushimi, K. Carcinogenic activity of processed bracken used as human food. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1972, 48, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirono, I.; Ushimaru, Y.; Kato, K.; Mori, H.; Sasaoka, I. Carcinogenicity of boiling water extract of bracken, Pteridium aquilinum. Jan. J. Cancer Res. 1978, 69, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Shin, S.L. Functional activities of ferns for human health. In Working with Ferns: Issues and Applications; Kumar, A., Fernández, H., Revilla, M.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- Fattal-Valevski, A. Thiamine (vitamin B1). J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 16, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mrowicka, M.; Mrowicki, J.; Dragan, G.; Majsterek, I. The importance of thiamine (vitamin B1) in humans. Biosci. Rep. 2023, 43, BSR20230374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, H.E.; Evans, E.T.; Evans, J.W.C. The production of “bracken staggers” in the horse and its treatment by B1 therapy. Vet. Rec. 1949, 61, 549–550. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, E.T.; Evans, W.C.; Roberts, H.E. Studies on bracken poisoning in the horse. Brit. Vet. J. 1951, 107, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.C.; Evans, I.A.; Humphreys, D.J.; Lewin, B.; Davies, W.E.J.; Axford, R.F.E. Induction of thiamine deficiency in sheep, with lesions similar to those of cerebrocortical necrosis. J. Comp. Pathol. 1975, 85, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P. Thiaminase activities and thiamine content of Pteridium aquilinum, Equisetum ramossisimum, Malva parviflora, Pennisetum clandestinum and Medicago sativa. J. Vet. Res. 1984, 56, 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- MetaCyc. Aminopyrimidine Aminohydrolase. Available online: https://biocyc.org/META/substring-search?type=NIL&object=3.5.99.2 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- MetaCyc. Thiamine Pyridinylase. Available online: https://biocyc.org/META/substring-search?type=NIL&object=2.5.1.2 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Fukuoka, M. Chemical and toxicological studies on bracken fern, Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum. VI. Isolation of 5-O-caffeoylshikimic acid as an antithiamine factor. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1982, 30, 3219–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, I.; Nafus, D.; Pimentel, D. Effects of cyanogenesis in bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) on associated insects. Ecol. Entomol. 1984, 9, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Driver, G.; Finch, S.; Swain, T.; Bernays, E. Seasonal variation in secondary plant compounds in relation to the palatability of Pteridium aquilinum. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1977, 5, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Oliveros, A. A method for the practical quantification and kinetic evaluation of cyanogenesis in plant material. Application to Pteridium aquilinum and Passiflora capsularis. Phytochem. Anal. 2000, 11, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressey, P.; Reeve, J. Metabolism of cyanogenic glycosides: A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartanti, D.; Cahyani, A.N. Plant cyanogenic glycosides: An overview. J. Farm. Il. Kes. 2020, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- MetaCyc. Prunasin β-Glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.118). Available online: https://biocyc.org/META/substring-search?type=NIL&object=3.2.1.118 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- MetaCyc. Mandelonitrile Lyase (EC 4.1.2.10). Available online: https://biocyc.org/META/substring-search?type=NIL&object=4.1.2.10 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Oliveros-Bastidas, A. Kinetics of the natural evolution of hydrogen cyanide in plants in neotropical Pteridium arachnoideum and its ecological significance. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Available online: https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2903/j.efsa.2017.5004 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- National Institutes of Health. Acute Exposure Guideline Levels for Selected Airborne Chemicals: Hydrogen Cyanide. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207601/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Rosenberger, G. Adlerfarn (Pteris aquilina)-die Ursache des sog. Stallrotes der Rinder Haematuria vesicalis bovis chronica. Dtsch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 1960, 8, 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, I.A.; Mason, J. Carcinogenic activity of bracken. Nature 1965, 208, 913–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pamakcu, A.M.; Price, J.M. Introduction of urinary bladder cancer in rats by feeding bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1969, 43, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Hirono, I.; Shibuya, C.; Fushimi, K.; Haga, M. Studies on carcinogenic properties of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum). J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1970, 45, 179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, R.; Vrigasov, A.; Antonov, A.; Dimitrov, A. Versuche zur Feststellung der Anwesenheit kanzerogener Stoffe im Harn der mit Heu aus Hamaturiegebieten gefutterten Kuhe. Wien. Tierarztl. Monantsschr. 1963, 50, 589–595. [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, H.; Ojika, M.; Wakamatsu, K.; Yamada, K.; Hirono, I.; Matsushita, K. Ptaquiloside, a novel norsesquiterpene glucoside from bracken (Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum). Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 4117–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoeven, J.C.M.; Lagerweij, W.J.; Posthumus, M.A.; Van Veldhuizen, A.; Holterman, H.A.J. Aquilide A, a new mutagenic compound isolated from bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum). Carcinogenesis 1983, 4, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirono, I.; Yamada, K.; Niwa, N.; Shizuri, M.; Ojika, M.; Hasaka, S.; Yamaji, T.; Wakamatsu, K.; Kigashi, H.; Nuyama, K.; et al. Separation of carcinogenicfraction of bracken fern. Cancer Lett. 1984, 21, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, R.M.G.; Oliveira, P.A.; Vilanova, M.; Bastos, M.M.; Lopes, C.C.; Lopes, C. Ptaquiloside-induced, B-cell lymphoproliferative and early-stage urothelial lesions in mice. Toxicon 2011, 58, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorre, A.O.; Caniceiro, B.D.; Wysocki, H.L., Jr.; Haraguchi, M.; Gardner, D.R.; Górniak, S.L. Selenium reverses Pteridium aquilinum-induced immunotoxic effects. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, A.O.; Caniceiro, B.D.; Fukumasu, H.; Gardner, D.R.; Lopes, F.M.; Wysochi, H.L., Jr.; Da Silva, T.C.; Haraguchi, M.; Bressan, F.F.; Górniak, S.L. Ptaquiloside reduces NK cell activities by enhancing metallothionein expression, which is prevented by selenium. Toxicology 2013, 304, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, T.; Naydan, D.; Nunes, T.; Pinto, C.; Peleteiro, M.C. Immunohistochemical evaluation of vascular urinary bladder tumors from cows with enzootic hematuria. Vet. Pathol. 2009, 46, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, M.P.; Lauren, D.R. Determination of ptaquiloside in bracken fern (Pteridium esculentum). J. Chromatogr. A 1991, 538, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.L.; Seawright, A.A.; Ng, J.C.; Hertle, A.T.; Thomson, J.A.; Bostock, P.D. Concentration of ptaquiloside, a major carcinogen in bracken fern (Pteridium spp.), from eastern Australia and from a cultivated worldwide collection held in Sydney, Australia. Nat. Toxins 1994, 2, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, M.T.; Reichmann, K.G.; Brock, I.J.; McKenzie, R.A.; Blaney, B.J. Residue potential of norsesquiterpene glycosides in tissues of cattle fed Austral bracken (Pteridium esculentum). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8518–8523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Jaimes-Espinoza, R. Comparative dynamics of ptaquiloside and pterosin B in the two varieties (caudatum and arachnoideum) of neotropical bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum L. Kuhn). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1995, 23, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, U.F.; Sakagami, Y.; Alonso-Amelot, M.; Ojika, M. Pteridanoside, the first protoilludane sesquiterpene glucoside as a toxic component of the neotropical bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum var. caudatum. Tetrahedron 1999, 55, 12295–12300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, D.D.S.F.; Keller, K.M.; Soto-Blanco, B. Ptaquiloside and pterosin B levels in mature green fronds and sprouts of Pteridium arachnoideum. Toxins 2020, 12, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Salazar, M.; Muñoz-Arrieta, R.; Chacón-Villalobos, A. Stability study of ptaquiloside biotoxin from P. esculentum var. Arachnoideum in bovine milk and artisanal dairy-food products. Food Res. Int. 2024, 192, 114756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somvanshi, R.; Lauren, D.R.; Smith, B.L.; Dawra, R.K.; Sharma, O.P.; Sharma, V.K.; Singh, A.K.; Gangwar, N.K. Estimation of the fern toxin, ptaquiloside, in certain Indian ferns other than bracken. Curr. Sci. 2006, 91, 1547–1552. [Google Scholar]

- Pathania, S.; Kumar, P.; Singh, S.; Khatoon, S.; Rawat, A.K.S.; Punetha, N.; Jensen, D.J.; Lauren, D.R.; Somvanshi, R. Detection of ptaquiloside and quercetin in certain Indian ferns. Curr. Sci. 2012, 102, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre, L.S.; Martínez, O.G.; Gardner, D.R.; Barbeito, C.G.; Micheloud, J.F. Determination of ptaquiloside in ten species of Pteris in northwestern Argentina. Toxicon 2023, 233, 107260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Pérez-Mena, M.; Calcagno, M.P.; Jaimes-Espinoza, R. Quantitation of pterosins A and B, and ptaquiloside, the main carcinogen of Pteridium aquilinum (L. Kuhn), by high pressure liquid chromatography. Phytochem. Anal. 1992, 3, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Brandt, K.K.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Ovesen, R.G.; Sørensen, J. Microbial degradation and impact of bracken toxin ptaquiloside on microbial communities in soil. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccone, C.; Cavoski, I.; Costi, R.; Sarais, G.; Caboni, P.; Traversa, A.; Miano, T.M. Ptaquiloside in Pteridium aquilinum subsp. aquilinum and corresponding soils from the South of Italy: Influence of physical and chemical features of soils on its occurrence. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 496, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisielius, V.; Lindqvist, D.N.; Thygesen, M.B.; Rodamer, M.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Rasmussen, L.H. Fast LC-MS quantification of ptesculentoside, caudatoside, ptaquiloside and corresponding pterosins in bracken ferns. J. Chromatogr. B 2020, 1138, 121966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.H. Presence of the carcinogen ptaquiloside in fern-based food products and traditional medicine: Four cases of human exposure. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.H.; Schmidt, B.; Sheffield, E. Ptaquiloside in bracken spores from Britain. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 2539–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.H.; Donnelly, E.; Strobel, B.W.; Holm, P.E.; Hansen, H.C.B. Land management of bracken needs to account for bracken carcinogens—A case study from Britain. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 151, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisielius, V.; Markussen, B.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Rasmussen, L.H. Geographical distribution of caudatoside and ptaquiloside in bracken ferns in Northern Europe. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jorgensen, D.B.; Diamantopoulos, E.; Kisielius, V.; Rosenfjeld, M.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Strobel, B.W.; Hansen, H.C.B. Bracken growth, toxin production and transfer from plant to soil: A 2-year monitoring study. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Castillo, U.; Smith, B.L.; Lauren, D.R. Bracken ptaquiloside in milk. Nature 1996, 382, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Castillo, U.; Smith, B.L.; Lauren, D.R. Excretion, through milk, of ptaquiloside in bracken-fed cows. A quantitative assessment. Le Lait 1998, 78, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesco, B.; Giorgio, B.; Rosario, N.; Saverio, R.F.; Francesco, D.G.; Romano, M.; Sante, R. A new, very sensitive method of assessment of ptaquiloside, the major bracken carcinogen in the milk of farm animals. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgilio, A.; Sinisi, A.; Russo, V.; Gerardo, S.; Santoro, A.; Galeone, A.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Roperto, F. Ptaquiloside, the major carcinogen of bracken fern, in the pooled raw milk of healthy sheep and goats: An underestimated, global concern of food safety. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 4886–4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Jorgensen, D.B.; Holbak, M.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Abrahamsen, P.; Diamantopoulos, E. Modeling the environmental fate of bracken toxin ptaquiloside: Production, release and transport in the rhizosphere. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 170658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clauson-Kaas, F.; Ramwell, C.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Strobel, B.W. Ptaquiloside from bracken in stream water at base flow and during storm events. Water Res. 2016, 106, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrbic, N.; Kisielius, V.; Pedersen, A.K.; Christensen, S.C.B.; Hedegaard, M.J.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Rasmussen, L.H. Occurrence of carcinogenic illudane glycosides in drinking water wells. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, C.; Ramwell, C.; Harhen, B.; Morrison, L.; Clauson-Kaas, F.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Campbell, G.; Sheahan, J.; Misstear, B.; Xiao, L. Ptaquiloside in Irish bracken ferns and receiving waters, with implications for land managers. Molecules 2016, 21, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kigoshi, H.; Imamura, Y.; Mizuta, K.; Niwa, H.; Yamada, K. Total synthesis of natural (−)-ptaquilosin, the aglycon of a potent bracken carcinogen ptaquiloside and the (+)-enantiomer, and their DNA cleaving activities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 3056–3065. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter, J. The norsesquiterpene glycoside ptaquiloside as a poisonous, carcinogenic component of certain ferns. Molecules 2022, 27, 6662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessjohann, L.A.; Brandt, W.; Thiemann, T. Biosynthesis and metabolism of cyclopropane rings in natural compounds. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 1625–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Domingo, L.R.; Alonso-Amelot, M.E. A DFT study of the conversion of ptaquiloside, a bracken fern carcinogen, to pterosin B in neutral and acidic aqueous medium. ChemistrySelect 2017, 2, 8178–8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, D.M.; Baird, M.S. Carcinogenic effects of ptaquiloside in bracken fern and related compounds. Br. J. Cancer 2000, 83, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranha, P.C.D.R.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Wolf-Jäckel, G.A.; Jensen, H.M.E.; Hansen, H.C.B.; Friis, C. Fate of ptaquiloside—A bracken fern toxin—In cattle. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218628. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, P.J.; Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Roberts, S.A.; Povey, A.C. The role of bracken fern illudanes in bracken fern-induced toxicities. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2019, 782, 108276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojika, M.; Wakamatsu, K.; Niwa, H.; Yamada, K. Ptaquiloside, a potent carcinogen isolated from bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum var. Latiusculum: Structure elucidation based on chemical and spectral evidence, and reactions with amino acids, nucleosides, and nucleotides. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 5261−5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Luis, K.B.; Hansen, P.B.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Hansen, H.C.B. Kinetics of ptaquiloside hydrolysis in aqueous solution. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25, 2623–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, U.F.; Wilkins, A.L.; Lauren, D.R.; Smith, B.L.; Towers, N.R.; Alonso-Amelot, M.E.; Jaimes-Espinoza, R. Isoptaquiloside and caudatoside, illudane-type sesquiterpene glucosides from Pteridium aquilinum var. caudatum. Phytochemistry 1997, 44, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, U.F.; Ojika, M.; Alonso-Amelot, M.; Sakagami, Y. Ptaquiloside Z, a new toxic unstable sesquiterpene glucoside from the neotropical bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum var. caudatum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1998, 6, 2229–2233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Nagao, T.; Matoba, M.; Koyama, K.; Natori, S.; Murakami, T.; Saiki, Y. Chemical assay of ptaquiloside, the carcinogen of Pteridium aquilinum, and the distribution of related compounds in the Pteridaceae. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1605–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikino, H.; Takahashi, T.; Takemoto, T. Structure of pteroside A and C, glycosides of Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1972, 20, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikino, H.; Takahashi, T.; Takemoto, T. Structure of pteroside Z and D, glycosides of Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1971, 19, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, F.; Noone, H.; Dickman, M.J.; Allen, E.; Mulcrone, W.D.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Hansen, H.C.B.; O’Connor, P.J.; Povey, A.C.; Williams, D.M. Bracken fern carcinogen, ptaquiloside, forms a guanine O6-adduct in DNA. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojika, M.; Sugimoto, K.; Okazaki, T.; Yamada, K. Modification and Cleavage of DNA by ptaquiloside. A new potent carcinogen isolated from bracken fern. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1989, 22, 1775–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushida, T.; Uesugi, M.; Sugiura, Y.; Kigoshi, H.; Tanaka, H.; Hirokawa, J.; Ojika, M.; Yamada, K. DNA damage by ptaquiloside, a potent bracken carcinogen: Detection of selective strand breaks and identification of DNA cleavage products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, V.L.; Molineux, I.J.; Kaplan, D.J.; Swenson, D.H.; Hurley, L.H. Reaction of the antitumor antibiotic CC-1065 with DNA. Location of the site of thermally induced strand breakage and analysis of DNA sequence specificity. Biochemistry 1985, 24, 6228–6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, L.H.; Warpehoski, M.A.; Lee, C.S.; McGovren, J.P.; Scahill, T.A.; Kelly, R.C.; Mitchell, M.A.; Wicnienski, N.A.; Gebhard, I. Sequence specificity of DNA alkylation by the unnatural enantiomer of CC-1065 and its synthetic analogs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4633–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]