Abstract

Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae and Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis are the causal agents of bacterial canker in cherry and walnut blight, respectively, which cause significant production losses worldwide. These diseases have traditionally been controlled by copper-based agrochemicals and, more recently, antibiotics. However, the prolonged use of these compounds has led to the emergence of resistant bacterial strains. The search for new, efficient, and environmentally friendly biocontrol alternatives has intensified. Phages are promising candidates due to their ability to specifically infect and lyse bacterial pathogens. Endolysin enzymes are responsible for bacterial cell wall degradation, and although they have been extensively studied in medical and veterinary contexts, their application in agriculture remains limited. In this study, 17 putative endolysins were identified from bacteriophages infecting X. arboricola pv. juglandis and P. syringae pv. syringae. Based on conserved domain analyses, 12 were classified as glycosidases, four as amidases, and one as an endopeptidase. From these, a recombinant amidase (LysP) and a recombinant glycosidase (LysX) were expressed in E. coli, purified, and evaluated as pure enzymes. Both endolysins exhibited significant antimicrobial activity, reducing P. syringae pv. syringae viability by 62–78.3% and X. arboricola pv. juglandis viability by 51.5–53.1%, respectively. These findings highlight these recombinant endolysins as promising candidates for the development of biocontrol strategies against bacterial plant pathogens.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, the Chilean agricultural industry has experienced significant development that has positioned Chile as one of the largest exporters of raw materials in the southern hemisphere [1,2]. During 2021, fresh and dry fruits dominated world exports [2,3]. In the case of fresh fruits, the cherry emerged as the main exported species, generating revenues of USD 393 million, while the walnut was positioned as the leading species in exports of dried fruits, contributing with USD 215 million [4]. The growth of the agricultural industry faces several challenges in maintaining its global competitive edge, including the phytosanitary status of plants. In this context, despite the efforts of public and private organizations to ensure the improvement and protection of various export plant species, productivity losses associated with crops remain a challenge.

Cherry trees (Prunus avium L.) are infected by phytopathogenic microorganisms like fungi, pseudofungi, viruses, bacteria, including phytoplasmas, and nematodes [5]. The main cause of production losses is the bacterial canker caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Bacterial canker usually affects young trees, and it has been reported that in extreme cases it could cause the death of over 50% of the trees in an orchard [6]. In the case of adult trees, defense responses are triggered by the secretion of dark gum. These secretions, known as gummosis, usually manifest around areas of necrosis with a distinctive fermentation odor. These secretions usually manifest around areas of necrosis or cankers in the wood [5,7]. However, the progression of the infection generates a decrease in the quality of the fruit and, over time, death of the branch or, in extreme cases, the death of the entire tree. Walnut trees (Juglans regia L.) are infected by various phytopathogenic microorganisms, such as fungi, nematodes, viruses and bacteria [8]. However, the walnut blight caused by Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis is the most relevant bacterial disease due to the production losses associated with it [9], causing production losses up to 50% [10]. The infection enters the walnut tree through natural openings (stomata and lenticels) and wounds [8]. Additionally, in mature nuts, the infection can discolor the shell and pulp of the nuts, leading to their premature fall.

Currently, the main strategy to contain the diseases caused by phytopathogenic bacteria is based on cultural management and the use of copper-containing agrochemicals or antibiotics [11,12]. The use of these agrochemicals over the last decades has led to a reduction in the effectiveness of treatments, due to the selection of bacterial strains resistant to copper, antibiotics or both [13,14,15]. The loss of effectiveness of current treatments has driven new research looking for alternatives to control these phytopathogenic microorganisms. Numerous studies have reported a wide variety of organisms and biological compounds that demonstrate antimicrobial capacity [16,17,18], with bacteriophages standing out among them. Due to their outstanding lysis capacity, bacteriophages are recognized as ideal candidates for various strategies to control pathogenic bacteria (phage therapy) in several fields, including human medicine, veterinary and agricultural industries [19,20]. Despite this, bacteriophages have shown several disadvantages. The most relevant is the development of bacterial resistance to bacteriophages, which can be acquired by bacteria through different mechanisms [21].

Due to advances in research and increased knowledge of bacteriophage biology, phage proteins known as endolysins have been developed as potential candidates for biocontrol strategies. Endolysins are proteins produced by bacteriophages that destroy the bacterial envelope during the final stage of the phage replication cycle, leading to cell lysis [21]. This mechanism involves the hydrolysis of peptidoglycan in the bacterial cell wall, resulting in the release of the bacterial cell’s internal contents [22]. Due to their ability to degrade peptidoglycan, endolysins are considered excellent therapeutic agents, with studies demonstrating their potential in human and animal medical applications to control bacterial infections, including those caused by antibiotic-resistant strains [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. However, there is limited research in agriculture, where phage endolysins could serve as potential candidates for biocontrol strategies against pathogenic bacteria that infect crops of economic importance. In the present study, it is reported for the first time the identification, recombinant expression, and bactericidal evaluation of endolysins derived from bacteriophages infecting the phytopathogenic bacteria X. arboricola pv. juglandis and P. syringae pv. syringae. Within these phages, three families of endolysins were identified: 12 classified as glycosidases, four as amidases, and one as an endopeptidase. The in vitro antimicrobial activity of two selected enzymes (one amidase and one glycosidase) against P. syringae pv. syringae and X. arboricola pv. juglandis was then evaluated. The tested endolysins were found to reduce the viability of P. syringae pv. syringae in the range of 62–78.3%, and that of X. arboricola pv. juglandis by 51.5–53.1%, respectively.

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Characterization of Genes Encoding Endolysins

Genomic analysis of 16 bacteriophages led to the identification of 25 putative endolysin-encoding genes (Table 1). Sequence analysis revealed that eight of these genes could not be functionally assigned; therefore, subsequent analyses focused on the remaining 17 genes. Among them, 12 encoded endolysins belong to the glycosidase family, four to the amidase family, and one to the endopeptidase family. The endolysins were grouped based on their catalytic domains, reflecting the diversity of peptidoglycan-binding and cleavage mechanisms (amidase, glycosidase, and endopeptidase) present in the analyzed phage genomes (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1.

Summary of hypothetical genes encoding different endolysin families in P. syringae pv. syringae and X. arboricola pv. juglandis bacteriophages.

Among the detected endolysins, two with potential antimicrobial activity were selected based on selection criteria, including an identity value ≥ 75% and coverage ≥ 80% [30]; the presence of specific lytic domains was confirmed using InterPro v97.0 [31], which identified either lysozyme domains (IPR023346) or N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase domains (IPR036505). Accordingly, LysX, a glucosidase derived from phage Xaj4.1, and LysP, an amidase derived from phage Pss63, were selected for further analysis.

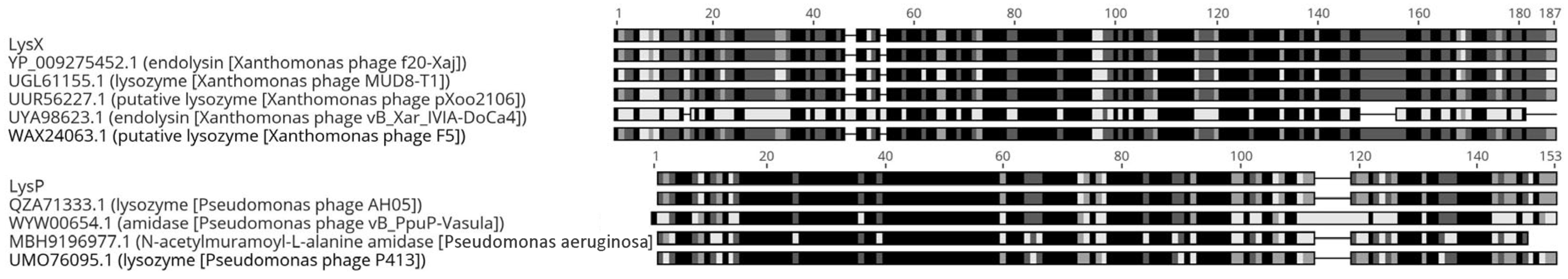

The endolysin LysX showed 100% identity and 100% coverage in its amino acid sequence with the glucosidase family of Xanthomonas phage f20-Xaj, according to the BLASTP alignment. In addition, LysX shared sequence identity with other phages, including Xanthomonas phage F5 (97%), Xanthomonas phage pXoo2106 (95%), Xanthomonas phage MUD8-T1 (81%), and Xanthomonas phage vB_Xar_IVIA-DoCa4 (46%) (Figure 1, top panel). LysX has a length of 185 amino acids, corresponding to an approximate molecular mass of 21.8 kDa. In silico analysis predicted the presence of an endolysin_R21-like domain (residues 27–169), with putative catalytic residues located at amino acids E(37), D(46), and T(52).

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence similarity between the identified endolysins LysX (top) and LysP (bottom) and the homologous protein identified by BLASTP (version 2.15.0). Each row corresponds to a protein sequence, and the horizontal axis indicates the amino acid position. Shaded blocks represent the degree of identity between sequences: black indicates complete identity, gray indicates different levels of similarity, and white represents non-conserved regions or gaps. Continuous dark blocks highlight highly conserved regions among the analyzed endolysins.

Similarly, the LysP sequence showed 100% identity and 100% coverage with the endolysin of Pseudomonas phage AH05. In addition, LysP displayed sequence similarity with several other endolysins, including those from Pseudomonas phage Pf1 ERZ-2017 (88%), Pseudomonas phage P413 (82%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (65%), and Pseudomonas phage vB_PpuP-Vasula (64%) (Figure 1, bottom panel). LysP has a length of 146 amino acids, with a theoretical molecular mass of 17.6 kDa. In addition, analysis indicated the presence of an amidase_2 domain (residues 13–133), including predicted Zn-binding, substrate-binding, and amidase catalytic sites.

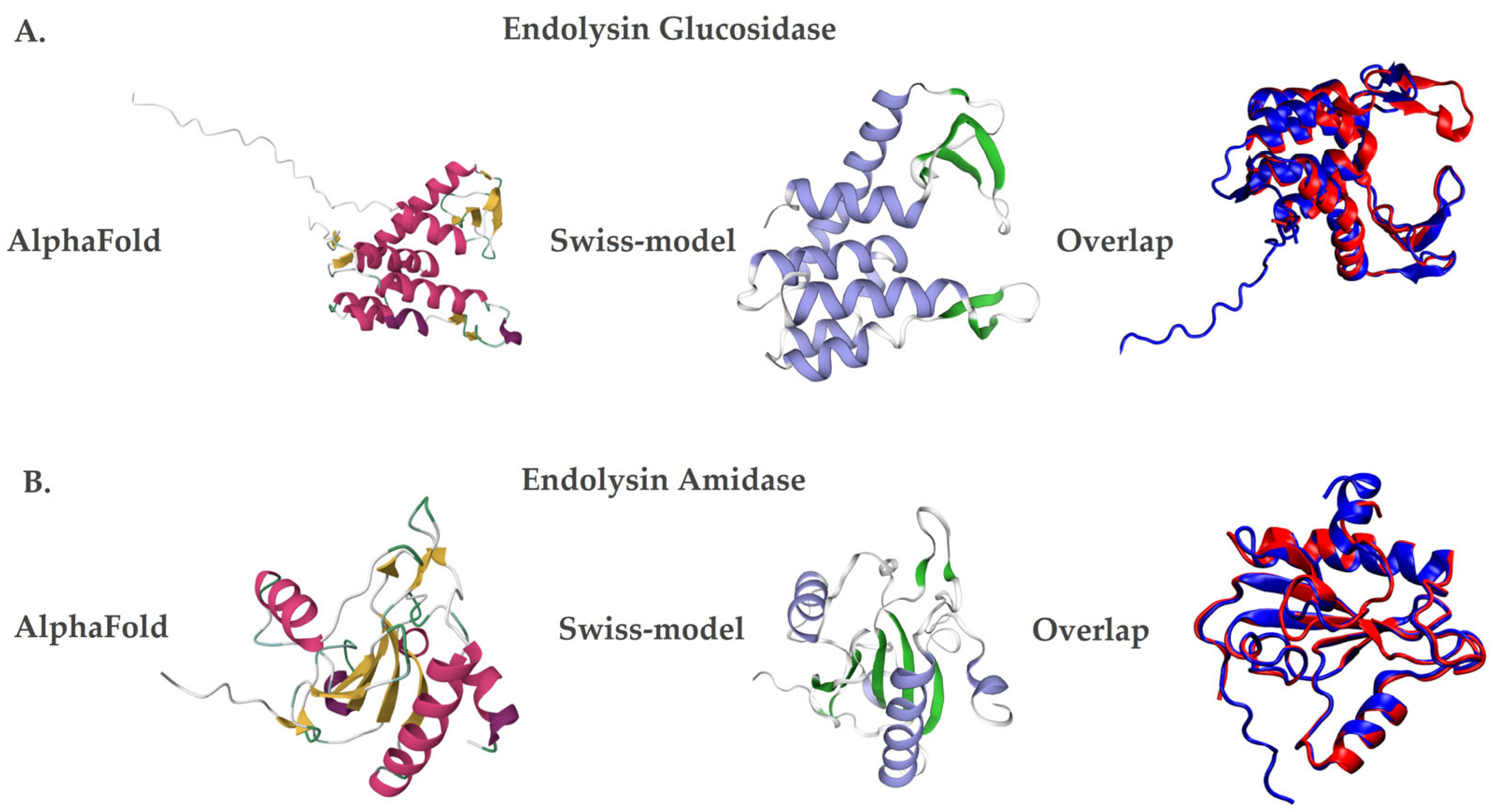

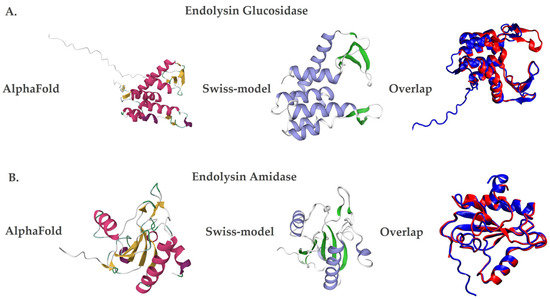

Additionally, the three-dimensional structural models of the endolysins LysX and LysP were generated using AlphaFold [32], based on artificial intelligence, and Swiss-Model [33], through homology. Both methods showed similar structures, but with differences in the number of secondary structures. In the case of LysX, the AlphaFold [32] predicted seven alpha helices and eight beta sheets, while the Swiss-Model [33] predicted six alpha helices and five beta sheets (Figure 2A). Similarly, for LysP, the AlphaFold showed five alpha helices and ten beta sheets, while Swiss-Model identified four alpha helices and seven beta sheets (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional structural models of the endolysins LysX and LysP. Protein structures were predicted using AlphaFold (left panels; red and yellow color scheme) and Swiss-Model (middle panels; violet and green color scheme). Structural superposition of both models is shown in the right panels (blue for AlphaFold and red for Swiss-Model). (A) LysX, a glucosidase-like endolysin derived from X. arboricola pv. juglandis phage 4.1. (B) LysP, an amidase-like endolysin derived from P. syringae pv. syringae phage 63.

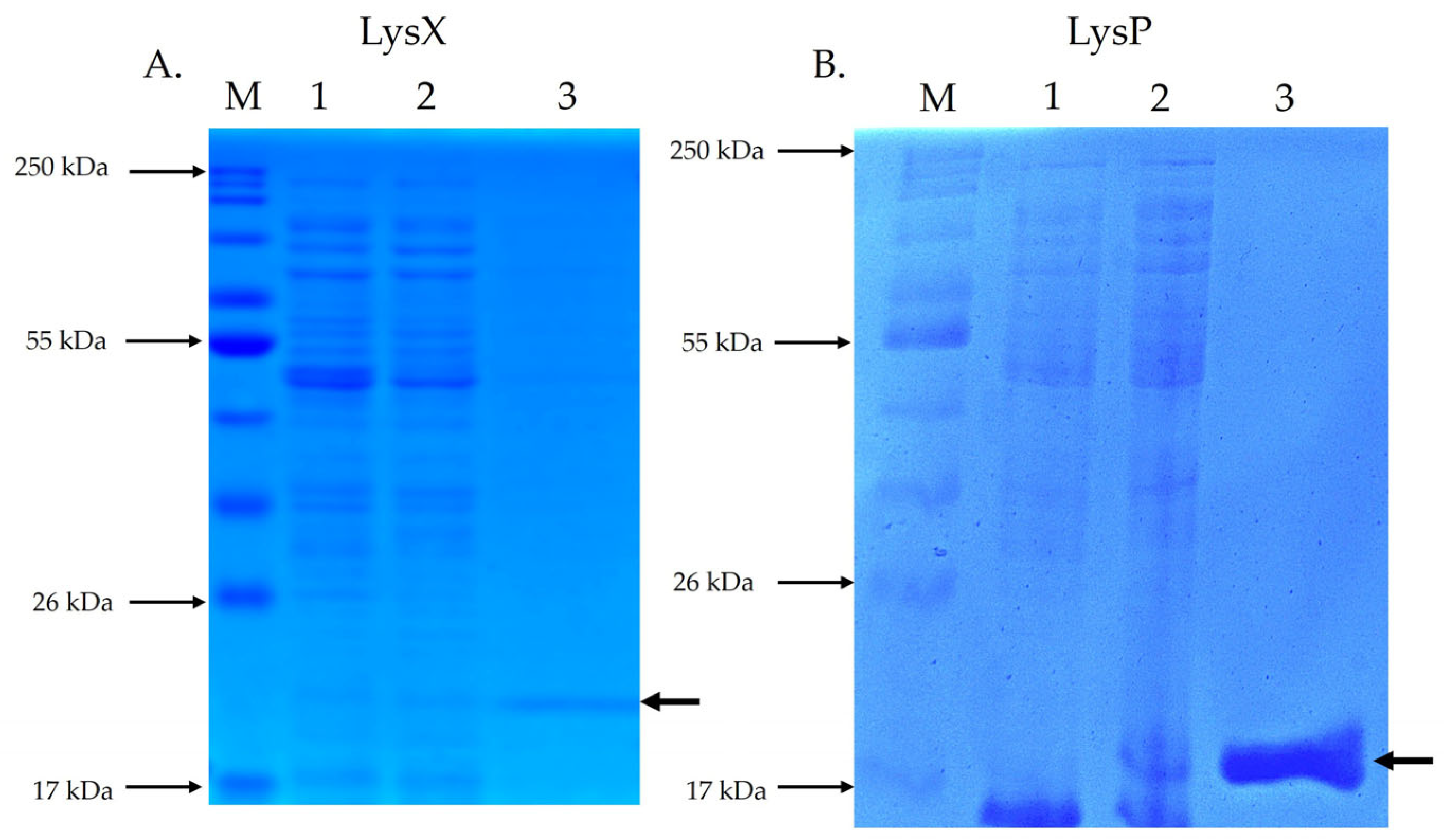

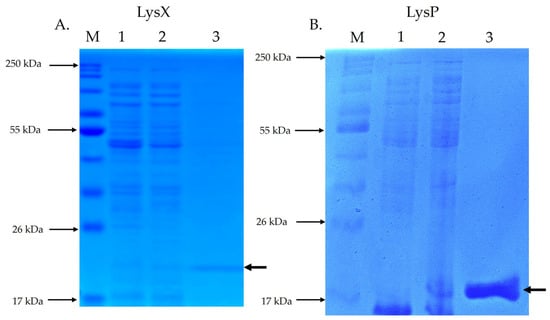

SDS-PAGE analysis of endolysin LysX (Figure 3A) revealed a protein band with electrophoretic homogeneity at the expected size of 21.8 kDa. Similarly, SDS-PAGE analysis of endolysin LysP (Figure 3B) showed a protein band with electrophoretic homogeneity at the expected size of 17.6 kDa.

Figure 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant endolysins LysX and LysP. The electrophoretic profile of total and purified proteins was evaluated by SDS-PAGE. M: molecular size marker; Lane 1: total protein without IPTG induction; Lane 2: total protein with IPTG induction; Lane 3: purified endolysin. The arrow indicates the position of the recombinant endolysin. (A) shows the SDS-PAGE of LysX (21.8 kDa), while (B) shows the SDS-PAGE of LysP (17.6 kDa).

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity of Recombinant LysX and LysP Proteins

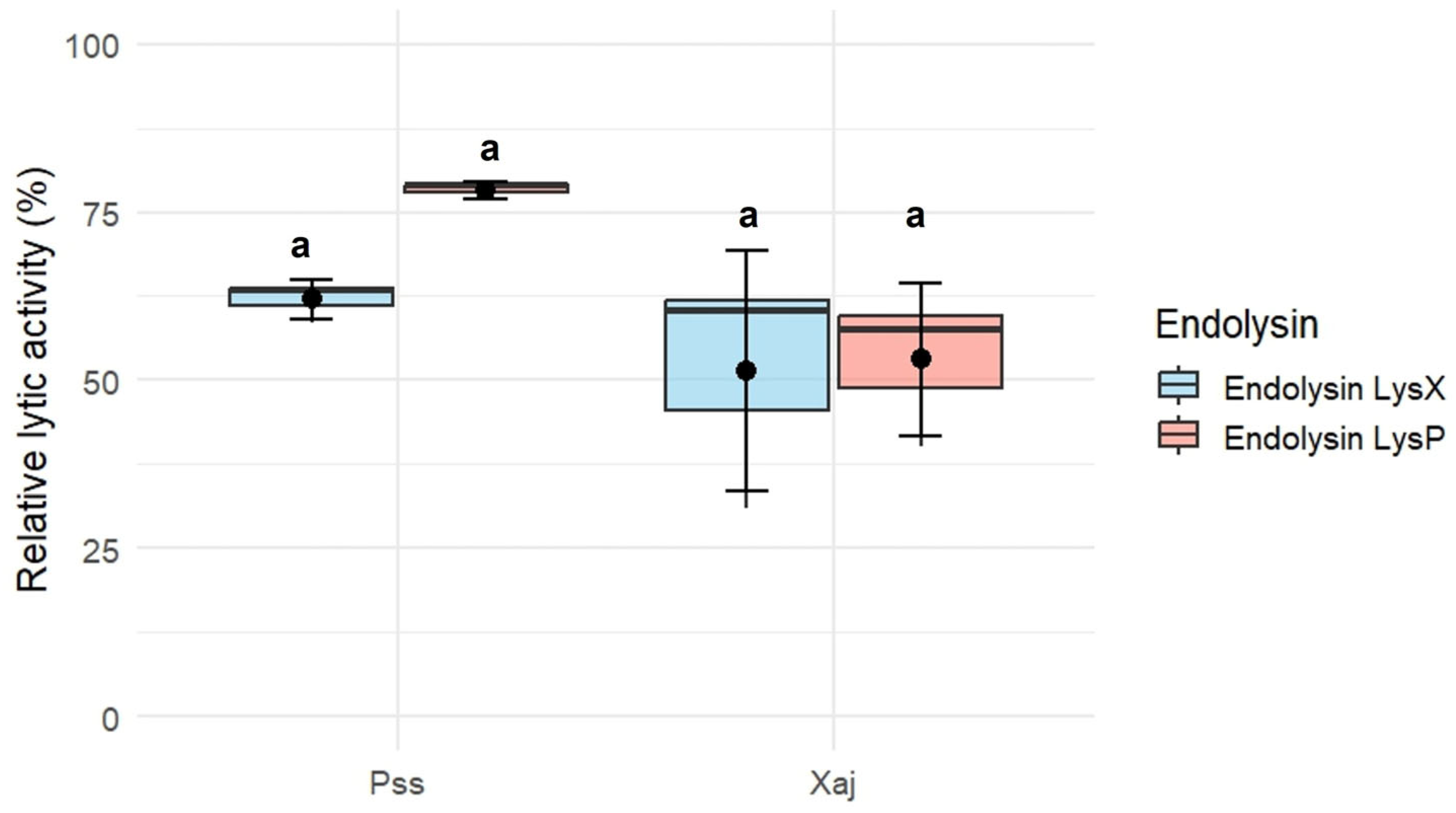

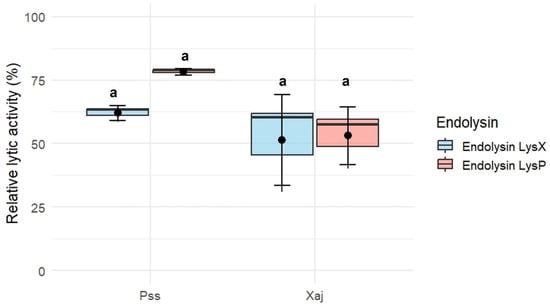

The endolysins LysX and LysP exhibited lytic activity against P. syringae pv. syringae S2 and X. arboricola pv. juglandis 66a (Figure 4). Using a concentration of 10 µg/mL for each endolysin, the relative lytic activity of LysX was 62 ± 2.99% against P. syringae pv. syringae S2 and 51.5 ± 17.9% against X. arboricola pv. juglandis 66a. In the case of LysP, the relative lytic activity was 78.3 ± 1.26% against P. syringae pv. syringae S2 and 53.1 ± 11.3% against X. arboricola pv. juglandis 66a.

Figure 4.

Lytic activity against P. syringae pv. syringae (Pss) strain S2 and X. arboricola pv. juglandis (Xaj) strain 66a of recombinant endolysin LysX and LysP (10 µg/mL). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM, n = 3). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05), whereas shared letters (e.g., “a”) denote groups that are not significantly different, as determined by the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test.

2.3. Characterization of Recombinant Endolysin LysX and LysP

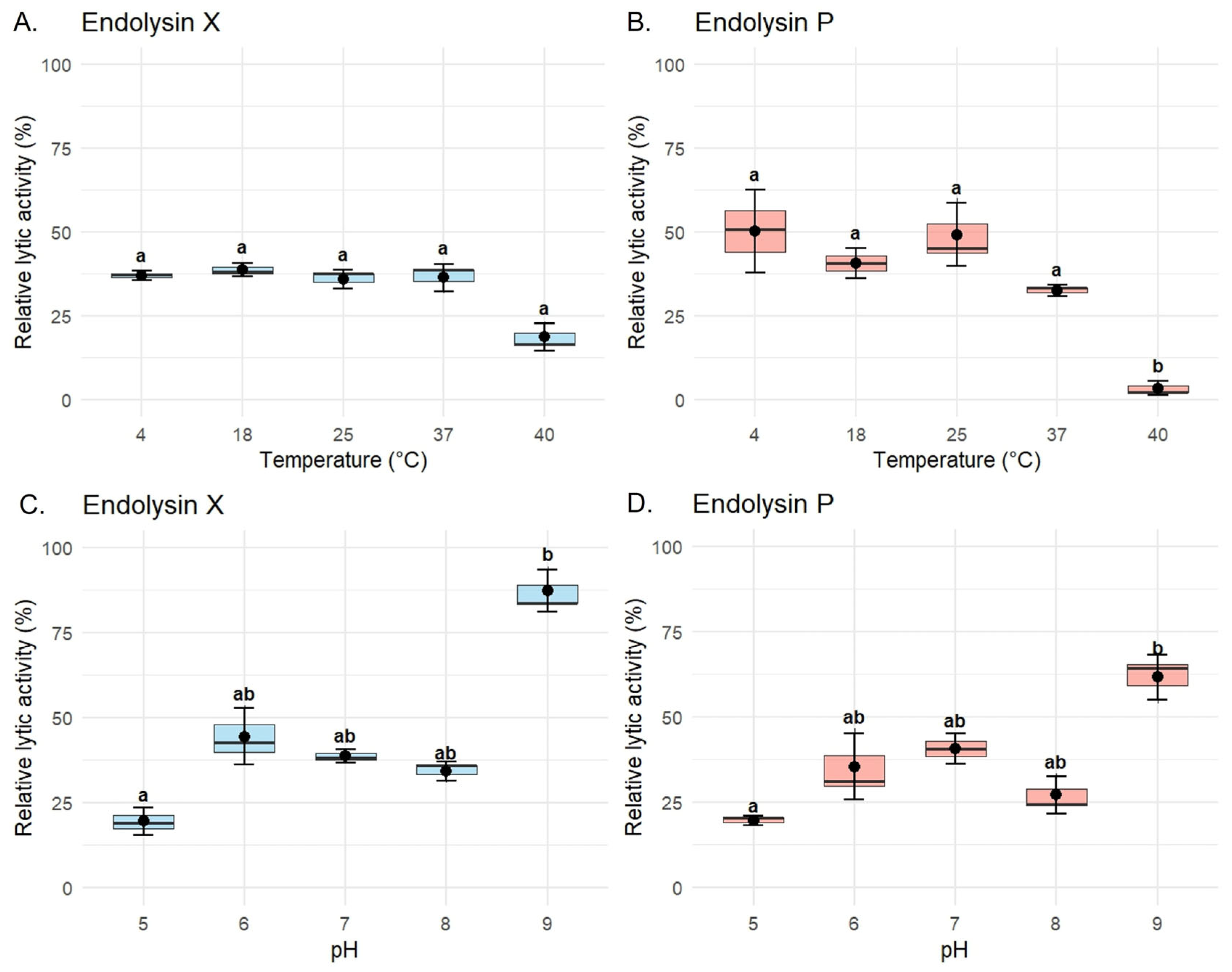

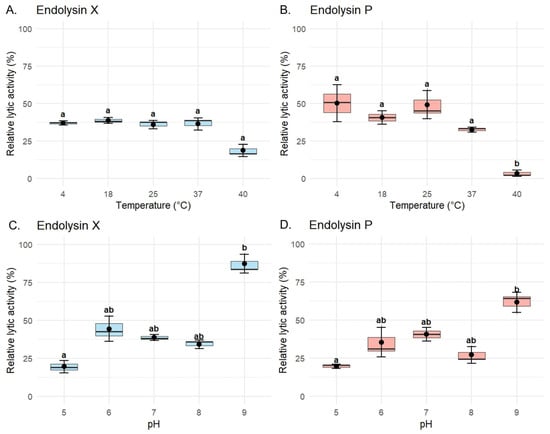

To evaluate the biochemical stability of the recombinant endolysins, assays were performed specifically using P. syringae pv. syringae strain P63. LysX maintained stable lytic activity across the tested temperature range against this host, ranging from 36.9 ± 1.42% at 4 °C to 38.8 ± 1.95% at 18 °C. Slight reductions were observed at 25 °C (36.0 ± 2.76%) and 37 °C (36.4 ± 4.08%), while a more pronounced decrease occurred at 40 °C (18.7 ± 4.05%). However, this reduction did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5A). In contrast, LysP exhibited a marked temperature-dependent variation in lytic activity against the same host. The highest activity was observed at 4 °C (50.2 ± 12.4%) and 25 °C (49.2 ± 9.4%), followed by 18 °C (40.6 ± 4.55%). Activity decreased substantially at 37 °C (32.5 ± 1.7%) and dropped drastically at 40 °C (3.44 ± 2.0%), where the loss of activity was statistically significant compared to all other conditions (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Thermostability and pH dependence of the lytic activity of recombinant endolysins LysX and LysP. Lytic activity assays for characterization were performed against P. syringae pv. syringae strain P63 using a final concentration of 10 µg/mL of purified enzyme. (A,B) Lytic activity profiles of LysX (A) and LysP (B) after incubation at different temperatures (4, 18, 25, 37, and 40 °C). (C,D) Lytic activity profiles of LysX (C) and LysP (D) under varying pH conditions (pH 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, and 9.0). Normality and homogeneity of variances were evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. For statistically significant comparisons (p < 0.05), differences among groups were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05), whereas shared letters (e.g., “ab”) indicate groups that are not significantly different. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (n = 3).

In the case of endolysin X, significant differences were also detected between pH 5 (19.5 ± 4.08%) and pH 9 (87.2 ± 6.07%), as well as between pH 8 (34.1 ± 2.89%) and pH 9, highlighting its enhanced activity under alkaline conditions (Figure 5C). At intermediate pH values, the activity was 44.4 ± 8.28% at pH 6, 38.8 ± 1.95% at pH 7, and 34.1 ± 2.89% at pH 8. For endolysin P, the highest activity was observed at pH 9 (61.6 ± 6.72%), with significant differences compared to pH 5 (19.5 ± 1.41%), as shown in Figure 5D. Intermediate values included 35.3 ± 9.68% at pH 6, 40.6 ± 4.55% at pH 7, and 27.1 ± 5.39% at pH 8, indicating a general trend of increased activity towards alkaline conditions, despite a slight decrease observed at pH 8.

3. Discussion

Analysis of the bacteriophage genomes for endolysin genes revealed that genome size does not correlate with the number of endolysin genes present. In the case of the genomic comparison of X. arboricola pv. juglandis bacteriophages, it was observed that, despite the similarity between these genomes, no relationship was observed with the number of genes identified as coding endolysins. The search for endolysins genes in X. arboricola pv. juglandis and P. syringae pv. syringae bacteriophage’s genomes was performed using different bioinformatics programs, complementing the information to effectively determine the required protein. Of the 25 identified genes, eight could not be assigned a putative function due to the strict adherence to selected parameters, even if some exhibited relevant functions. On the other hand, if these sequences of proteins were analyzed with other bioinformatics programs, it would be possible to find unique properties or determine that they belong to families that have not yet been characterized [34]. These sequences may represent novel lytic enzymes or members of uncharacterized families, underscoring the potential of phage genomes as a reservoir for discovering innovative antimicrobial tools. Of the 17 potential endolysins that met the parameters established for their identification, those that fulfilled the criteria described by Oliveira et al. [30], as well as on the concordance of their identified domains with hydrolytic activity, were one amidase family endolysin (LysP) and one glucosidase family endolysin (LysX). The antimicrobial potential of the enzymes was evaluated against X. arboricola pv. juglandis and P. syringae pv. syringae. Both endolysins demonstrated broad cross-genus activity, proving effective against both Xanthomonas and Pseudomonas strains. These results indicate that the recombinant endolysins possess lytic activity within or exceeding the ranges previously reported in the literature. Against X. arboricola pv. juglandis, the efficiency of LysP and LysX ranged from 51.5 ± 17.9% to 53.1 ± 11.3%, which is comparable to the efficiencies described by Wu et al. [35] against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (19–74%). When tested against P. syringae pv. syringae, the observed efficiencies ranged from 62 ± 2.99% to 78.3 ± 1.26%, exceeding the values reported by Abdelrahman et al. [36] for P. aeruginosa (52.3%), and comparable to those described by Ni et al. [37] against P. syringae pv. actinidiae (68.1%). These findings indicate that these recombinant endolysins perform at a level equal to or even superior to those reported previously, supporting their potential as novel bactericidal agents.

The physicochemical characterization revealed important differences between the two enzymes. Endolysin P was more sensitive to elevated temperatures, showing a marked decrease in activity from 50.2 ± 12.4% to 3.44 ± 2.00%, corresponding to an approximately 14.6-fold reduction when incubated at 40 °C compared to lower temperatures. In contrast, endolysin X maintained higher stability across the tested temperature range. Both enzymes exhibited maximal lytic activity under alkaline conditions (pH 9), with activity levels exceeding 60% (X: 87.2 ± 6.72% and P: 61.6 ± 6.07%). Conversely, their lowest activity was observed under acidic conditions (pH 5), decreasing to values below 20% (X: 19.5 ± 4.08% and P: 19.5 ± 1.41%), representing an approximately four-fold reduction relative to activity at pH 9. These results are consistent with in silico analyses performed using the Compute pI/Mw (ProtParam) tool from the ExPASy Server [38], which predicted isoelectric points of 9.07 for LysP and 9.04 for LysX, suggesting that these enzymes are more stable and functionally active under conditions close to their theoretical pI.

These findings suggest that these recombinant endolysins perform at levels comparable to those reported previously, supporting their role as novel bactericidal candidates. Furthermore, their observed cross-genus activity against Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas highlights their potential as a versatile biocontrol strategy for addressing multiple economically significant plant pathogens in a commercial context.

Despite the promising antimicrobial properties observed, the large-scale application of purified endolysins is currently hindered by significant economic limitations, primarily the high costs associated with protein purification. In this study, purified enzymes were utilized to establish fundamental biochemical parameters; however, the use of non-purified lysates or enriched crude extracts represents a highly promising and cost-effective alternative for future field-scale applications. To this end, alternative production strategies must be explored. For instance, plant-based expression systems have emerged as efficient platforms for scalable protein production, offering a viable route for generating endolysin-enriched crude extracts for sustainable agricultural use [39,40,41].

In conclusion, the biochemical characterization and lytic efficiency demonstrated by LysX and LysP in vitro position these endolysins as promising candidates for the control of P. syringae and X. arboricola. However, it is recognized that the transition from laboratory assays to agricultural application requires evaluating these molecules in the complex environment of the plant phyllosphere. Future research will focus on in planta trials using detached leaves and fruits to assess how factors such as UV radiation, humidity, and leaf surface interactions may influence their stability and antimicrobial performance. This study provides the fundamental basis for developing new, sustainable biocontrol strategies against bacterial diseases in fruit trees.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Isolates, Bacteriophages, and Growth Conditions

The characteristics of the bacterial isolates used in this work are summarized in Table 2. P. syringae pv. syringae isolate P63, P. syringae pv. syringae isolate S2, X. arboricola pv. juglandis strain 4.1 and X. arboricola pv. juglandis isolate 66a are wild-type isolates previously characterized in the Plant Biology and Agro-food Systems Innovation Laboratory (BVISA), INTA, University of Chile. All isolates were cultured in solid or liquid Luria–Bertani (LB) media (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Phytopathogenic bacteria were incubated at 28 °C, whereas Escherichia coli was grown at 37 °C. Additionally, a total of 16 bacteriophages infecting P. syringae pv. syringae and X. arboricola pv. juglandis were used. These bacteriophages were isolated from environmental samples, such as irrigation canals and wastewater, between years 2015 and 2019, and form part of the collection available in the laboratory BVISA, INTA, University of Chile. Phage genomes were sequenced by an external service at Macrogen (Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Table 2.

Bacterial isolates used in this study.

4.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

The bacteriophage genomes were assembled and annotated using the bioinformatics programs Patric V3.33.16 [42] and Geneious V11.0.18+10 [43] for a preliminary characterization of genes encoding endolysins in each genome. The NCBI Basic Local Alignment Search Tool Protein (BLASTp) [44] was used to identify endolysin-coding sequences from the P. syringae pv. syringae and X. arboricola pv. juglandis phage genomes, using an identity value ≥ 75% and coverage ≥ 80% as parameters [30]. Furthermore, the presence of specific lytic domains was confirmed using InterPro v97.0 [31]. Putative endolysin genes were further classified into glycosidase (EC 3.2.1.17), amidase (EC 3.5.1.28), and endopeptidase (EC 3.4.16.-) families based on conserved domain analysis using InterPro and manual inspection of catalytic motifs. A comprehensive characterization of these genomic findings, including domain identifiers and sequence coverage for each identified gene, is presented in Supplementary Table S1. Predicted catalytic and binding residues were identified by aligning the deduced amino acid sequences with characterized endolysins from public databases.

The theoretical isoelectric point and molecular weight of the endolysins were determined using the Compute pI/Mw tool from the ExPASy server [38]. Additionally, AlphaFold V2.1.2 [32] and Swiss-Model [33] were employed to obtain two three-dimensional structural models. The secondary-structure content (number of α-helices and β-sheets) of the predicted models was assessed by structural inspection and compared across the generated models.

4.3. Vector Construction and Endolysin Expression

The endolysin LysX, encoded in the X. arboricola pv. juglandis phage 4.1 genome, was amplified by PCR using the primers Glu4.1F (5′-CGATCGCCATGGGAGGAAACCAGCAGCAGAACCAA-3′) and Glu4.1R (5′-ACCTTCTCGAGTCCTCCTCCCTTCACTTGGGGTTT-3′), which were designed in our laboratory. The forward primer contains an NcoI restriction site, while the reverse primer incorporates an XhoI restriction site. The resulting PCR product (586 bp) was purified and digested with NcoI and XhoI.

Similarly, the endolysin LysP, encoded in the P. syringae pv. syringae phage 63 genome, was amplified using primers Am63F (5′-CGATCGCCATGGGAGGAGCCAAGGTTCAATTCAA-3′) and Am63R (5′-ACCTTCTCGAGTCCTCCTCCGAGGCCGACCGTT-3′), which were designed in our laboratory. The resulting 489 bp PCR fragment was purified and digested with NcoI and XhoI.

Gene amplification was performed under an initial denaturation step at 98 °C for 30 s, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 98°C for 10 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, ending with an extension at 72 °C for 2 min. For amplification, the high-fidelity enzyme Q5® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) was used.

The amplified genes were cloned into the expression vector pET21d (Novagen®, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and the insertion of the endolysin gene was verified using the universal primers T7 promoter and T7 terminator. The resulting pET21d-derived plasmids, containing the endolysin gene LysX or LysP, were denominated pLysX (5933 bp) and pLysP (5819 bp), respectively. These plasmids were independently transformed by thermal shock in the E. coli T7 Express lysY strain (New England Biolabs, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmids containing the endolysin genes were sent to the Sequencing and Omics Technologies Unit of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile for sequencing to verify both the insertion and the orientation of the genes.

The expression of the endolysin genes was carried out in exponential cultures (OD600 ≈ 0.5) of the transformed E. coli T7 Express lysY strain. Protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG, and the cells were harvested after two hours of induction at 37 °C for endolysin LysP, and at 20 °C for endolysin LysX. Following cell disruption by ultrasonication, both endolysins were purified using the His-Spin Protein Miniprep™ kit (Symo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). The electrophoretic homogeneity and expected molecular weights for each purified fraction (21.8 kDa for LysX and 17.6 kDa for LysP) were independently verified by 15% SDS-PAGE. A negative control was included, in which the expression of the endolysins was not induced.

To halt bacterial growth, cultures were incubated on ice for 20 min, followed by centrifugation. The resulting pellet was resuspended in His-Binding buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.7; 300 mM sodium chloride; 10 mM imidazole; 0.03% Triton X-100) (Symo Research, USA) supplemented with 0.1 mM protease inhibitors. Cell disruption was performed using an ultrasonic cell disruptor (UCD-250 Series, BioBase, Jinan, China), applying 2 s pulses with 3 s intervals for a total of 5 min, while maintaining the samples on ice. Finally, the lysate was centrifuged at 10,000× g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.2 µm pore-size membrane filter. Endolysins were purified using the His-Spin Protein Miniprep™ kit (Symo Research, USA) based on the C-terminal 6xHis-tag. Total protein extracts from induced and non-induced E. coli cultures were analyzed by 15% SDS-PAGE alongside purified endolysin fractions. Samples were prepared by mixing with loading buffer and boiling for 5 min prior to electrophoresis. Protein concentrations were determined using the Qubit Protein BR Assay (Invitrogen™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA).

4.4. Antimicrobial Activity Assay of Endolysin

Although CFU counting is a direct measure of viability, monitoring OD600 nm reduction is a widely accepted high-throughput method for initial endolysin characterization and kinetic analysis of cell wall degradation [45,46,47,48].

P. syringae pv. syringae S2 and X. arboricola pv. juglandis 66a bacterial cultures grew until reaching an OD600 of 0.4. To destabilize the bacterial membrane, cells were treated with 0.05% triton X-100 prior to the addition of endolysins. Bactericidal activity was evaluated by incubating the bacteria separately with each endolysin for 1 h at 25 °C. The lytic activity of the endolysins was determined using the formula described by Ding et al. [49]:

Relative lytic activity (%) = (OD_600 control − OD_600 endolysins)/(OD_600 control) × 100

For all lytic activity and characterization assays, purified endolysins were used at a final concentration of 10 µg/mL. Each experiment was performed in triplicate (n = 3) to ensure reproducibility and statistical robustness.

4.5. Characterization of Endolysin LysX and LysP

For the characterization of the endolysins, their stability under different pH and temperature conditions was evaluated. For pH stability, 50 mM Tris-HCl solutions adjusted to pH values ranging from 5 to 9 were prepared, and the endolysins were incubated with each buffer for 30 min at 4 °C. Similarly, for thermal stability, the endolysins were exposed to different temperatures (4, 18, 25, 37 and 40 °C) for 30 min in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer at pH 7.0. In both assays, after the incubation period, the endolysins were incubated with the bacteria for 1 h at 25 °C, and their lytic activity was determined using the previously described formula. For thermal and pH stability assays, the lytic activity of endolysins was evaluated against P. syringae pv. syringae strain P63.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

The data did not meet the assumption of normality; non-parametric analyses were applied. Differences among groups were assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction. Results were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

This study identified and characterized two recombinant endolysins, LysP and LysX, derived from phage genomes, which demonstrated promising antimicrobial activity against X. arboricola pv. juglandis and P. syringae pv. syringae. Both enzymes exhibited distinct physicochemical properties: LysX showed higher thermal stability and maintained activity under varying conditions, whereas LysP was more sensitive to high temperatures. Additionally, both endolysins displayed optimal lytic activity under alkaline conditions (pH 9) and reduced activity in acidic environments (pH 5), consistent with their predicted isoelectric points. When compared with previous studies, the efficiencies observed in this work were within or exceeded the range reported for other phage-derived endolysins, supporting their potential as effective bactericidal agents. Nevertheless, challenges remain regarding their large-scale application, mainly due to the high costs of protein purification. Alternative production platforms, such as plant-based expression systems, could provide viable and scalable solutions for implementation.

Overall, these findings contribute to the growing evidence supporting the application of phage endolysins as sustainable and environmentally friendly antimicrobial agents. Their demonstrated efficacy against key phytopathogenic bacteria highlights their potential as innovative tools for crop protection and reinforces the necessity of optimizing their stability and large-scale production. Moreover, the characterization of endolysins with distinct catalytic mechanisms—specifically the glycosidase LysX and the amidase LysP—facilitates the development of synergistic enzymatic cocktails. Such multi-target approaches could significantly enhance lytic potency while providing a robust strategy to mitigate the emergence of bacterial resistance in agricultural ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants15030431/s1, Table S1: Identification and characterization of endolysins encoded in the genomes of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae and Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis bacteriophages. The rows highlighted in blue are the endolysins encoded in the bacteriophages of P. syringae pv. syringae and X. arboricola pv. juglandis bacteriophages that were selected for subsequent expression.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D., A.Z. and G.H.; methodology, B.D., C.I.-D., C.G., C.J.B. and N.T.; software, B.D. and M.A.-A.; validation, P.C., N.F. and A.Z.; formal analysis, B.D.; investigation, B.D., P.C., G.H. and A.B.; resources, C.J.B., N.F. and GH.; data curation, B.D.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.; writing—review and editing, G.H., A.Z. and N.F.; visualization, B.D. and M.A.-A.; supervision, G.H. and A.B.; project administration, B.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo” (ANID), Chile, under grant VIU24P0065.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- López Hidalgo, S.A. Análisis de las Exportaciones Chilenas de Fruta Fresca a los Principales Mercados Mundiales en la Última Década; Universidad Austral de Chile: Valdivia, Chile, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Subrei-ProChile. Liderazgo Exportador de Chile en 2021; Subrei-ProChile: Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pefaur, J. Evolución de la Fruticultura Chilena en los Últimos 20 Años; ODEPA: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pefaur, J. Boletín de Fruta, Agosto 2023; ODEPA: Santiago, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gamalier, L. Cáncer Bacterial del Cerezo: Epidemiologia de la Enfermedad y Estrategias de Control. Boletín INIA 2020, 420, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, P.A.; Lolas, C.M.; Labra, L.E. Cerezos: Principales enfermedades presentes en la región del Maule. Boletín INIA 2006, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, F.; Beltrán, M.F.; Millas, P.; Moreno, Z.; Hinrichsen, P.; Meza, P.; Sagredo, B. Genome sequence resources of Pseudomonas syringae strains isolated from sweet cherry orchards in Chile. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2022, 35, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, A.M. Manual del Manejo Orgánico del Nogal. Boletín INIA 2022, 454. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.S.; Cheon, W.; Lee, Y.; Kwon, H.T.; Seo, S.T.; Balaraju, K.; Jeon, Y. Identification and characterization of Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis causing bacterial blight of walnuts in Korea. Plant Pathol. J. 2021, 37, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, C.B.; Alvarez, A.M. Principales enfermedades del nogal en Chile: Peste negra, pudrición radicular y del cuello. Tierra Adentro 2003, 48, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Osdaghi, E.; Behlau, F.; Köhl, J.; Jones, J.B.; Aubertot, J.N. Thirteen decades of antimicrobial copper compounds applied in agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus, S.G.; Osorio, N.V.; France, I.R. Cáncer bacteriano en cerezos: Opciones de control de cancros. Boletín INIA 2019, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Aprile, F.; Heredia-Ponce, Z.; Cazorla, F.M.; de Vicente, A.; Gutiérrez-Barranquero, J.A. A Large Tn7-like transposon confers hyperresistance to copper in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e02528-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, M.F.; Osorio, V.; Lemus, S.G.; Millas, O.P.; France, I.A.; Correa, F.; Sagredo, D.B. Bacterial community associated with canker disease from sweet cherry orchards of central valley of Chile presents high resistance to copper. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 81, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuera, G.; González-Escalona, N.; Véliz, C.; Vera, F.; Romero, J. Draft genome sequences of four Xanthomonas arboricola pv. juglandis strains associated with walnut blight in Chile. Genome Announc. 2015, 3, e01160-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Chen, R.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Black, D.S.; Walsh, W.R.; Kumar, N. A New era of antibiotics: The clinical potential of antimicrobial peptides. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkar, Z.; Bagasra, O.; Gene Pace, D. Bacteriophage Therapy: A potential solution for the antibiotic resistance crisis. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2014, 8, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Kessler, M.G.C.; Marchán-Rivadeneira, M.R.; Han, Y. Combating antimicrobial resistance in the post-genomic era: Rapid antibiotic discovery. Molecules 2023, 28, 4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, L.K.; Silva, E.C.; Campos, W.F.; Del Fiol, F.S.; Vila, M.; Dąbrowska, K.; Krylov, V.N.; Balcão, V.M. Biotechnological applications of bacteriophages: State of the art. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 212–213, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, A.; Woolston, J.; Sulakvelidze, A. Phage biocontrol applications in food production and processing. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 40, 267–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Majkowska-Skrobek, G.; Maciejewska, B.; Delattre, A.-S.; Lavigne, R. Learning from bacteriophages—Advantages and limitations of phage and phage-encoded protein applications. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2012, 13, 699–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, S.; Gao, T.; Mao, Z.; Shen, Y.; Pan, Z.; Guo, C.; Yu, Y.; Yao, H. Identification of a novel broad-spectrum endolysin, Ply0643, with high antibacterial activity in mouse models of streptococcal bacteriaemia and mastitis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 143, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.; Proença, D.; Cantante, C.; Silva, F.A.; Leandro, C.; Lourenço, S.; Milheiriço, C.; De Lencastre, H.; Cavaco-Silva, P.; Pimentel, M.; et al. Novel chimerical endolysins with broad antimicrobial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Drug Resist. 2012, 18, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, D.W.; Jin, J.S.; Kim, J. Antimicrobial activity of LysSS, a novel phage endolysin, against Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Zeng, Z.; Mai, K.; Yang, Y.; Feng, J.; Bai, Y.; Sun, B.; Xie, Q.; Tong, Y.; Ma, J. Preliminary treatment of bovine mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus, with Trx-SA1, recombinant endolysin of S. aureus bacteriophage IME-SA1. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 191, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Yang, R.; Fan, K.; Dong, H.; Gao, C.; Wang, S.; Yu, L.; Cheng, Z.; Lei, L. External lysis of Escherichia coli by a bacteriophage endolysin modified with hydrophobic amino acids. AMB Express 2019, 9, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, C.; Song, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Feng, X. The broad-spectrum endolysin LySP2 improves chick survival after Salmonella pullorum infection. Viruses 2023, 15, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoopes, J.T.; Stark, C.J.; Kim, H.A.; Sussman, D.J.; Donovan, D.M.; Nelson, D.C. Use of a bacteriophage lysin, PlyC, as an enzyme disinfectant against Streptococcus equi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1388–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junjappa, R.P.; Desai, S.N.; Roy, P.; Narasimhaswamy, N.; Raj, J.R.M.; Durgaiah, M.; Vipra, A.; Bhat, U.R.; Satyanarayana, S.K.; Shankara, N.; et al. Efficacy of anti-staphylococcal protein P128 for the treatment of canine pyoderma: Potential applications. Vet. Res. Commun. 2013, 37, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.; Melo, L.D.R.; Santos, S.B.; Nóbrega, F.L.; Ferreira, E.C.; Cerca, N.; Azeredo, J.; Kluskens, L.D. Molecular aspects and comparative genomics of bacteriophage endolysins. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 4558–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, M.; Chang, H.Y.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; Kandasaamy, S.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Qureshi, M.; Raj, S.; et al. The interpro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D344–D354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; De Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfull, G.F.; Hendrix, R.W. Bacteriophages and their genomes. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Ahmed, T.; Yang, Y.; Loh, B.; Leptihn, S.; Yan, C.; Chen, J.; Li, B. The holin-endolysin lysis system of the Op2-like Phage X2 infecting Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Viruses 2021, 13, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, F.; Gangakhedkar, R.; Nair, G.; El-Didamony, G.; Askora, A.; Jain, V.; El-Shibiny, A. Pseudomonas phage ZCPS1 endolysin as a potential therapeutic agent. Viruses 2023, 15, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Wang, L.; Deng, B.; Jiu, S.; Ma, C.; Zhang, C.; Almeida, A.; Wang, D.; Xu, W.; Wang, S. Characterization of a lytic bacteriophage against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae and its endolysin. Viruses 2021, 13, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In The Proteomics Protocols Handbook; Walker, J.M., Ed.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, M.J.B.; Burnett, A.C. Therapeutic recombinant protein production in plants: Challenges and opportunities. Plants People Planet 2020, 2, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, R.J.; Young, M.T.; Scofield, S. Optimising expression and extraction of recombinant proteins in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1043478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulshreshtha, A.; Sharma, S.; Padilla, C.S.; Mandadi, K.K. Plant-based expression platforms to produce high-value metabolites and proteins. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1043478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, R.D.; Assaf, R.; Brettin, T.; Conrad, N.; Cucinell, C.; Davis, J.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dickerman, A.; Dietrich, E.M.; Kenyon, R.W.; et al. Introducing the bacterial and viral bioinformatics resource center (BV-BRC): A resource combining PATRIC, IRD and ViPR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D678–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?CMD=Web&PAGE_TYPE=BlastHome (accessed on 19 November 2022).

- Shen, K.; Shu, M.; Zhong, C.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, S.; Pan, H.; Wang, S.; Wu, G. Characterization of a broad-spectrum endolysin RLysJNwz and its utility against Salmonella in foods. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 3229–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Qi, Q.; Lu, X. Characterization of Salmonella endolysin XFII produced by recombinant Escherichia coli and its application combined with chitosan in lysing Gram-negative bacteria. Microb. Cell Factories 2022, 21, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Y.; Lwin, S.Z.C.; El-Telbany, M.; Masuda, Y.; Honjoh, K.I.; Miyamoto, T. Characterization of two novel endolysins from bacteriophage PEF1 and evaluation of their combined effects on the control of Enterococcus faecalis planktonic and biofilm cells. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor Mohammadi, T.; Lin, Y.; Maung, A.T.; Shen, C.; Zhao, J.; El-Telbany, M.; Zayda, M.; Masuda, Y.; Honjoh, K.; Miyamoto, T. Characterization and antibacterial activity of highly thermo- and PH-stable endolysin LysCPQ7 and its application as a biocontrol agent against Clostridium perfringens in milk and cheese. Food Control 2024, 156, 110157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. An endolysin LysSE24 by bacteriophage LPSE1 confers specific bactericidal activity against multidrug-resistant Salmonella strains. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.