Abstract

The influence of crown illumination on leaf damage of horse chestnut species (Aesculus hippocastanum L., Aesculus glabra Willd, Aesculus flava Aiton, Aesculus pavia L., Aesculus × carnea Hayne, Aesculus parviflora Walter, Aesculus chinensis Bunge) affected by ohrid leaf miner (Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dymić) was studied using some accessions from the arboretum botanical tree collection. A. hippocastanum, A. glabra, A. flava had the lowest chl a content in the foliage on the sunlit side of the crown, while in A. pavia, A. parviflora and A. chinensis this indicator was the highest. The chl a content in the leaves of A. hippocastanum and A. flava under shaded conditions was 1.3 and 2.4 times higher than in the sunlit part, while in A. pavia, A. parviflora and A. chinensis the chl a content on the shaded side was 1.2, 1.6 and 1.3 times lower. The quantitative content of chl b in the sunlit part of the crown in A. hippocastanum and A. flava was significantly higher than in the other species. Moreover, while A. flava and A. parviflora had the highest chl b content in the foliage of the shaded part of the crown, A. glabra and A. × carnea had the lowest. Similarly, differences in proline levels were found in the leaves of different horse chestnut species on the sunny side of the crown. Higher proline levels in less infested species were identified. Water content imbalances due to feeding by leaf miners were most characteristic of the severely affected species. Chlorophyll fluorescence determination revealed high photochemical activity with an effective defense system in resistant species, while non-resistant species exhibited weak defense mechanisms in both sunlight and shade. To assess horse chestnut species the hyperspectral analysis indices (DSWI and SIPI) were also successfully applied. Changes in chl a and chl b content, proline levels, and leaf water-holding properties can be used to assess the resistance of horse chestnut species using classical physiological and biochemical methods. Hyperspectral analysis indices (DSWI and SIPI) can also be successfully applied.

1. Introduction

The horse chestnut is a very common ornamental tree, widely used in landscaping in many cities around the world. Its popularity is due to its beautiful blooms, tolerance to urban growth factors, and longevity.

Species of the genus Aesculus vary in susceptibility to ohrid leaf miner (Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimič), with the horse chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum L. being the primary host of this pest [1]. The feeding of the larvae of this leaf miner and the gnawing of passages in the leaf tissues causes premature leaf fall of Aesculus hippocastanum L. [2]. A number of other Aesculus species are also susceptible to C. ohridella, such as Aesculus turbinata Blume, Aesculus sylvatica Bartram, Aesculus pavia L., Aesculus flava Aiton, and Aesculus glabra Wild [3,4,5]. Horse chestnuts species resistant to the ohrid leaf miner include Aesculus indica (Wall. ex Camb.) Hook, Aesculus californica (Spach) Nutt., Aesculus parviflora Walter, Aesculus assamica Griff. [6,7], Aesculus × carnea Hayne, Aesculus parviflora and Aesculus chinensis [5,8].

Changes in pigment levels, particularly the levels of chlorophylls a and b and their ratios, are crucial for understanding the mechanisms of plant adaptation to stress. A decrease in the quantitative content of photosynthetic pigments under various stress conditions can reduce the rate of carbon assimilation and the formation of photosynthetic products [9]. Chlorophyll fluorescence is known to be used as an indicator of physiological processes [10]. Carotenoids have antioxidant properties and play an important role in plant adaptation to adverse environmental factors [11]. At higher light levels or in response to biotic stress, carotenoid concentrations may increase, as zeaxanthin, formed in the xanthophyll cycle, is synthesized in plants to reduce the negative impact of ROS [12].

Carbohydrates produced during photosynthesis are an essential and attractive nutrient for phytophagous insects [13], and plants containing higher amounts of carbohydrates are more susceptible to pests, including the horse chestnut leaf miner [14]. Thus, the maximum amount of carbohydrates was found in the leaves of three horse chestnut species: A. hippocastanum, A. glabra, and A. flava, which are most susceptible to the orchid leaf miner—54.1; 46.3; and 42.7%, respectively. The lowest amount of carbohydrates in the leaves of such a leaf miner-resistant horse chestnut species as A. chinensis was observed [5]. It has been suggested that pests may interact with plants through visual stimuli [15,16]. Green leaf blades of host plants are readily colonized by herbivorous insects, whose larvae and caterpillars feed on leaf tissue [17]. Female horse chestnut leaf miners lay eggs on leaves with a large proportion of green surface because such leaves have more food for the growth and development of larvae [18].

Tree canopies exhibit different illumination patterns, and leaves developing under these conditions exhibit differences in morphology and biochemistry [19]. Thus, leaf biomass and area are positively correlated with daily photon irradiance [20].

The water balance of infected leaves can change depending on the intensity of infection [21]. Biotic stress also alters proline content, for example, in Ulmus [22] and Populus [23]. In the aboveground parts of plants, proline content often serves as a marker of osmotic stress after insect damage, for example, in Melolontha melolontha [24], in which its content was shown to increase during the feeding of insect larvae. Additionally, higher proline levels increase the NADP+/NADPH ratio, enhancing the synthesis of phenolic compounds directly involved in plant defense [25].

Methods for remote monitoring of plant health are currently being actively developed. Important areas of this development are based on identifying relationships between plant parameters and their optical characteristics. Key methods of optical remote monitoring include measuring chlorophyll fluorescence, RGB imaging, and analyzing the spectral characteristics of light reflected by plants [26]. This method is based on differences in reflectivity, which manifests itself in variability in the optical properties of plants [27,28]. The chlorophyll and photochemical reflectance indices, as well as water content, appear promising for this purpose. The chlorophyll index is closely related to the chlorophyll content of leaf tissues and can serve as a measure of the capacity of the photosynthetic apparatus and the potential ability of the plant to absorb solar radiation [29]. These indices have found application in characterizing stress conditions caused by mineral nutrient and moisture deficiencies [28,30].

Thus, we believe that the study of physiological and biochemical parameters allows us to assess the condition of horse chestnut species affected by the leaf miner, differing in their resistance to the pest (Aesculus hippocastanum L., Aesculus glabra Willd, Aesculus flava Aiton, Aesculus pavia L., Aesculus × carnea Hayne, Aesculus parviflora Walter, Aesculus chinensis Bunge). It was also necessary to find out that the illumination of the crown can influence both the number of pests and the physiological state of plants affected by this pest. This factor may be the reason for the decrease in the decorative properties of plants in urban environments. Thus, the aim of the study was to evaluate the influence of crown sunny illumination on changes in biochemical processes associated with foliage damage by the ohrid leaf miner in various horse chestnut species.

2. Results

2.1. Determination of the Second Generation Population of C. ohridella

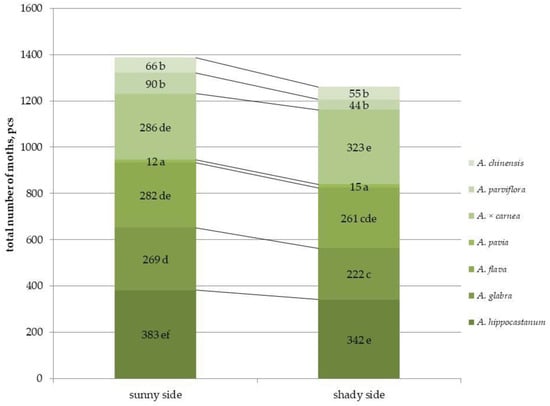

The study revealed differences in the abundance of the horse chestnut leaf miner on different horse chestnut species in the second generation (Figure 1 and Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Total abundance of second-generation C. ohridella moths on leaves of different horse chestnut species, under conditions of varying sunlit illumination. Values are presented as mean ± standard error at α = 0.05 according to ANOVA tests. Letters indicate significant differences were determined (α = 0.05).

Differences in the number of leaf miners in traps on parts of the crown with different illumination were observed only for a few species, namely A. hippocastanum, A. glabra, and A. parviflora. These species showed significant reductions in moth abundance by 1.1, 1.2, and 2 times, respectively. However, no differences were found between the sunlit and shaded parts of the crown in other species. Among all species, the highest number of leaf miners was observed in A. hippocastanum (an average of 382 males per trap), which was 30 times more than A. pavia, which had the lowest number of moths per trap (an average of 12 males per trap). A. parviflora and A. chinensis also showed the lowest number of leaf miners in traps, 90 and 66 moths, respectively. Thus, the most affected species, regardless of crown illumination, were A. hippocastanum; A. glabra; A. flava and A. × carnea, and the least affected species included A. pavia; A. parviflora and A. chinensis. The results obtained were confirmed by the number of mines per leaf (Figure 1 and Figure S1). For example, in A. hippocastanum, the number of mines reached 78, while in A. parviflora and A. chinensis, virtually no mines were found on the leaf (1 mine per leaf) (Figure S2). Duncan’s test for pairwise comparisons revealed statistically significant differences between plants species damaged by leaf miner (Table S1).

Parasitic wasps were found on the leaves in the most affected horse chestnut species, A. hippocastanum, at all stages of damage (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Parasitic wasps (Pteromalidae sp.) on the A. hippocastanum leaf surface (left) and on the mines (right), formed by the caterpillar of the ohrid leaf miner (C. ohridella).

2.2. Determination of Photosynthetic Pigment Content

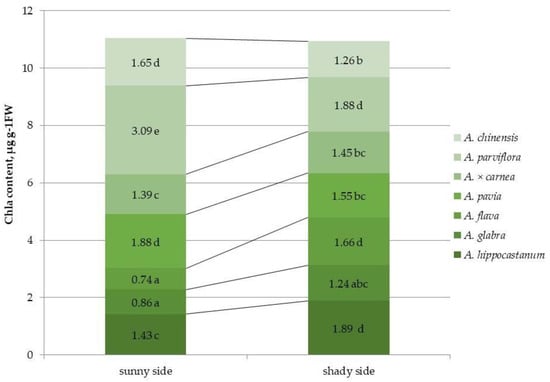

Different horse chestnut species have been evaluated for their photosynthetic pigment content under different light conditions (Figure 3 and Figure S3). The species most affected by the leaf miner, namely A. hippocastanum, A. glabra, and A. flava, had the lowest quantitative content of chl a on the sunlit side, while the least affected species, A. pavia, A. parviflora, and A. chinensis, had the highest value. In A. × carnea, the value of the indicator was average. It was found that the chl a content in A. hippocastanum and A. flava under shaded conditions was 1.3 and 2.4 times higher than in the sunlit part of crown, while in A. pavia, A. parviflora, and A. chinensis, the chl a content was 1.2, 1.6 and 1.3 times less than on the sunny side.

Figure 3.

Chlorophyll a (chl a) content in leaves of different horse chestnut species affected by C. ohridella under varying foliage illumination conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard error at α = 0.05 according to ANOVA tests. Letters indicate significant differences were determined (α = 0.05).

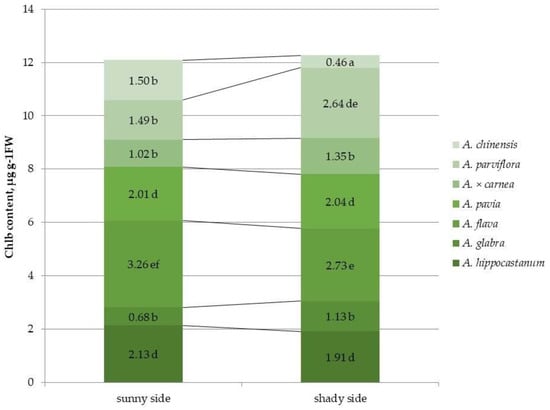

In contrast to the chl a content, the chl b content in the heavily affected species, A. hippocastanum and A. flava, was significantly higher than in the other species in the illuminated part of the crown. (Figure 4 and Figure S4). Moreover, in A. flava and A. parviflora, the highest amount of chl b was noted in the leaves of the shaded part of the crown, and in A. glabra and A. × carnea this indicator had the lowest value. In contrast to chl a, an increase in the concentration of chl b under shading was found only in A. parviflora. The remaining species showed either a reliable decrease in this indicator, as in A. hippocastanum, A. flava and A. chinensis (by 1.1, 1.2 and 3.3 times, respectively), or the content of chl b did not differ depending on the illumination of the crown, as in A. glabra, A. pavia and A. × carnea.

Figure 4.

Chlorophyll b (chl b) content in leaves of different horse chestnut species affected by C. ohridella under varying foliage illumination conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard error at α = 0.05 according to ANOVA tests. Letters indicate significant differences were determined (α = 0.05).

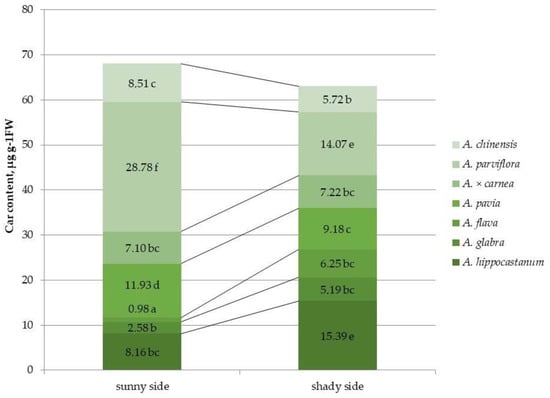

The carotenoid content in the species A. hippocastanum, A. glabra and A. flava was 1.9, 2.01 and 3 times higher, respectively, under shaded crown conditions compared to the sunlit side (Figure 5 and Figure S5). The remaining species, except A. × carnea, showed a significant decrease in this parameter under shaded conditions. The carotenoid content of A. parviflora in illuminated canopy conditions was the highest and 11.1 and 8.6 times higher than the lowest values in A. glabra and A. flava, respectively. A. parviflora also had the highest carotenoid concentration under shaded conditions, but in that case, A. hippocastanum can also be noted with a similar value for this parameter.

Figure 5.

Carotenoid (car) content in leaves of different horse chestnut species affected by C. ohridella under varying foliage illumination conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard error at α = 0.05 according to ANOVA tests. Letters indicate significant differences were determined (α = 0.05).

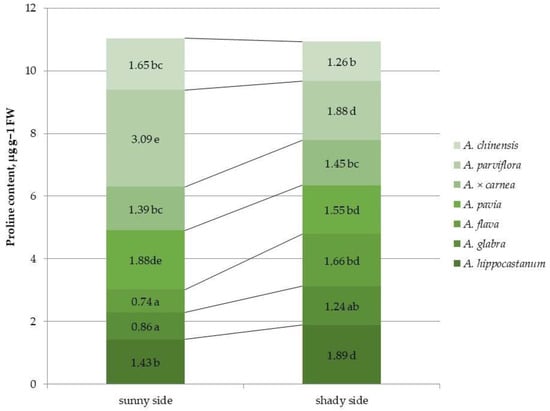

2.3. Determination of Proline Content

Differences in proline content were observed between horse chestnut species (Figure 6 and Figure S6).

Figure 6.

Proline content in leaves of different horse chestnut species affected by C. ohridella under varying foliage illumination conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard error at α = 0.05, according to ANOVA tests. Letters indicate significant differences were determined (α = 0.05).

Among all of the species, the highest proline content under sunlit crown conditions was shown in A. pavia and A. parviflora, and the lowest in A. glabra and A. flava. Under shaded canopy conditions, A. parviflora also showed the highest proline content, which was approximately equal to that of A. hippocastanum. A significant increase in proline content under shaded conditions was found in the species A. hippocastanum and A. flava (1.3 and 2.24 times, respectively). The proline content in leaves decreased in species, such as A. parviflora, A. pavia and A. chinensis (by 1.6, 1.2, 1.3 times, respectively), under shaded conditions compared to the sunlit side.

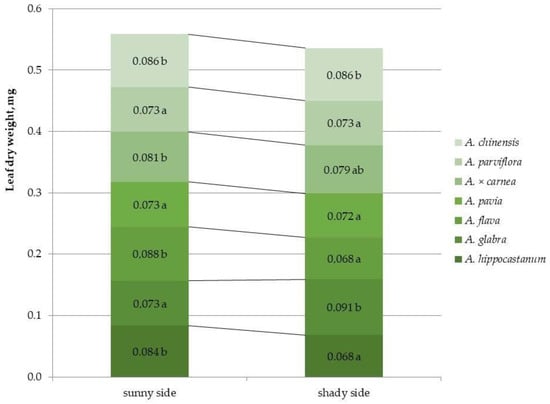

2.4. Determination of Dry Leaf Biomass

For most species, crown illumination did not affect the dry leaf biomass index, with the exception of A. hippocastanum and A. flava, which showed a decrease in this index under shaded conditions (by 1.2 and 1.3 times, respectively) and A. glabra, for which the dry biomass value under crown shaded conditions increased by 1.2 times (Figure 7 and Figure S7).

Figure 7.

Dry biomass of leaves of different horse chestnut species affected by C. ohridella under varying foliage illumination conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard error at α = 0.05 according to ANOVA tests. Letters indicate significant differences were determined (α = 0.05).

Among all species, the highest value of this characteristic under sunlit crown conditions was shown by A. flava, and under shaded crown conditions the highest index was noted for A. glabra, A. × carnea and A. chinensis.

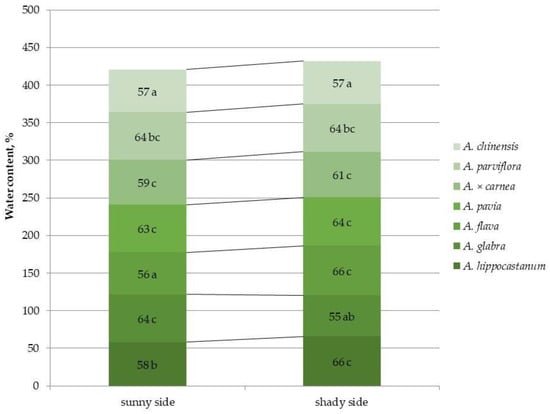

2.5. Detection of Water Content in Leaves of Different Horse Chestnut Species

An important parameter characterizing the water status under abiotic stress is the water content of plant tissues. Leaf water content was calculated based on the fresh and dry biomass of leaves (Figure 8 and Figure S8).

Figure 8.

Leaf water content in different horse chestnut species affected by C. ohridella under varying foliage illumination conditions. Values are presented as mean ± standard error at α = 0.05, according to ANOVA tests. Letters indicate significant differences were determined (α = 0.05).

Among all horse chestnut species A. flava and A. chinensis exhibited the lowest water content on the sunny side of the crown. The highest leaf water content under shaded conditions was found in A. hippocastanum and A. flava. No significant differences were found in this indicator for most species under different lighting conditions. In the highly affected species A. hippocastanum and A. flava, a 1.1-fold increase in leaf water content was observed under shaded conditions, while A. glabra showed a 1.2-fold decrease in this parameter under shaded conditions.

A strong correlation between the number of mines and the number of moths in traps (r = 0.8) was revealed the potential relationship between these parameters. On the other hand, we have shown a negative correlation between the number of leaf miners in traps and chl a content (r = −0.3). Chl a content decreased accordingly with plant damage caused by leaf miners. A weak negative correlation was also found between the chl b content and numbers of leaf mines (r = −0.3). In addition, there were no relationships between chl b and the number of leaf miners in traps and plant dry biomass, accordingly. A negative correlation was found between the number of mines, leaf miner numbers in traps and the quantitative carotenoid content (r = −0.2 and −0.3) or water content (r = −0.18 and −0.1) (Table S2).

2.6. Determination of Hyperspectral Indicators

Using hyperspectral analysis, some of the most common indices reflecting the physiological states of the plant were studied (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hyperspectral indices reflecting the physiological state of horse chestnut trees.

To assess the possibilities of analyzing photographs obtained with an optical camera under the same lighting conditions, an analysis was carried out of the RSB indices of images of the surface of leaves of various types of horse chestnut taken with an optical camera under artificial halogen lighting.

Thus, no significant difference was found between horse chestnut species in the NDWI index, regardless of crown illumination. However, changes were already detected between the species in the DSWI index. This index decreased in A. glabra (from 3.284 to 2.866) and A. pavia (from 2.97 to 2.4160). Nevertheless, in one of the least affected species, specifically A. chinensis, the index value increased from 2.786 to 3.364 under shaded conditions. The highest DSWI value was found in A. chinensis under crown shaded conditions and amounted to 3.364, while the lowest index was shown in A. parviflora (1.888) under shaded conditions.

One of the key indicators characterizing the efficiency of the plant photosynthetic apparatus is the chlorophyll index. A decrease in the SIPI photochemical index in some affected horse chestnut species was found under conditions of reduced foliage illumination, from 1.403 to 1.218 in A. glabra and from 1.365 to 1.248 in A. pavia. This index increased with crown shading only in two species, A. × carnea (from 1.157 to 1.211) and A. chinensis (from 1.331 to 1.418).

2.7. Determination of Leaf Chlorophyll Fluorescence

Based on chlorophyll fluorescence measurements, a comparative analysis can be conducted and a clear ranking of the tolerance of various horse chestnut species to light stress can be developed (Table 2 and Table 3). All studied species exhibited characteristics of photoinhibition to varying degrees, as their key indicator of photosystem health, Fv/Fm, was below the optimal level. However, their ability to cope with this stress varied significantly.

Table 2.

Chlorophyll fluorescence indices of leaves of different horse chestnut species under sunlit conditions.

Table 3.

Chlorophyll fluorescence indices of leaves of different horse chestnut species under shading conditions.

A. chinensis and A. parviflora proved to be the most adapted and efficient species. Their photosynthetic apparatus demonstrates a balanced balance: in sunlight, they exhibit the highest values of both potential efficiency (Fv/Fm) and actual productivity (ETR). This success is due to powerful defense mechanisms—the ability to actively dissipate excess light energy as heat (high NPQ and Y(NPQ) values), which minimizes damage (their Y(NO) value is the lowest). It is important that these species also maintain leadership in shady conditions, which indicates their high plasticity and ability to work productively in different light conditions.

The group of horse chestnut species with moderate tolerance to leaf miner includes A. × carnea, A. pavia and A. glabra. Their photosynthetic apparatus is functional but experiences significant stress. Their defense systems are moderately developed, resulting in moderate levels of damage. When exposed to shade, their productivity significantly decreases, indicating a narrower range of adaptation compared to the leading species.

The least resilient and most vulnerable species were A. flava and, especially, A. hippocastanum. The photosynthetic apparatus of these species is severely impaired. They are unable to effectively defend themselves against excess light, as evidenced by the weakest photoprotection indices (NPQ, Y(NPQ)). Consequently, they suffer the greatest losses—demonstrating an extremely high proportion of uselessly dissipated energy (Y(NO)), which not only is not used for photosynthesis but also aggravates damage. This is reflected in very low productivity both in the light and, critically, in the shade. Particularly significant is the sharp decline in A. hippocastanum activity in the shade, indicating the inability of its photosystem to function under limited energy conditions.

3. Discussion

The crowns of mature trees can have both shaded and sun-exposed areas, creating different living conditions for organisms [19]. Larvae of leaf-eating pests (Spodoptera frugiperda and Spodoptera litura) are exposed to sunlight during feeding. Light intensity affects only the development of male leaf-eating insect larvae, while changes in the development of both male and female larvae have been demonstrated in Ostrinia furnacalis and Chilo suppressalis. Developmental stages of these insect species were significantly delayed in complete darkness [31]. For example, we previously showed that crown sunlight illumination in A. hippocastanum affected the abundance and population density of C. ohridella during the growing season [32]. As a result, the highest pest abundance was observed on the sunlit side of the tree crown, and the lowest on the shaded side. This may be due to the larger food supply, both due to the high carbohydrate content and the large cell surface area of the palisade parenchyma and lower epidermis. In a study of horse chestnut species collection, a higher number of miners were also found in traps in the illuminated part of the A. hippocastanum crown (an average of 382 males per trap). This is consistent with our previous studies conducted in 2024 on this collection of horse chestnut species [5]. In a study of a collection of horse chestnut species, a higher number of miners were also found in traps of A. hippocastanum on the sunlit side of the crown. Fewer moths were also found on the shaded side of the crown for two species, A. glabra and A. parviflora, while for other species, pest abundance was equal on both the sunlit and shaded sides. It was also shown that the species most affected, regardless of crown sunlight illumination, were A. hippocastanum, A. glabra, A. flava and A. × carnea, while the least affected species included A. pavia, A. parviflora and A. chinensis.

The chemical composition of host plant leaves significantly influences insect behavior [14,33]. Moreover, the chemical composition itself can vary under different illumination conditions [19]. The amount of pigments in the leaves determines the color of these organs and serves as a visual signal that facilitates the detection of the host plant by adult Lepidoptera [16]. It was found that leaf mining by larvae causes changes in the volatile compounds of the affected leaves, which prevents other individuals from laying eggs on the same leaves, which may facilitate the search for new green leaves by other females of the horse-chestnut leaf miner [34]. Thus, it was previously found that the total chlorophyll content in the leaves of A. × neglecta, which is completely resistant to C. ohridella, was significantly higher than that of A. turbinata, which is infested by this pest [14]. Similarly, higher chlorophyll levels in A. hippocastanum leaves coincided with a period when it was less colonized by the horse chestnut leaf miner. A. hippocastanum, A. glabra, and A. flava had the lowest quantitative content of chl a on the sunlit side, and in the least affected species by the leaf miner, A. pavia, A. parviflora and A. chinensis, this indicator was the highest. Under shaded conditions, A. hippocastanum and A. flava showed an increased content of chl a compared to the illuminated part, while in the less affected species, A. pavia, A. parviflora and A. chinensis, the content of chl a was lower. However, the opposite situation was observed for the chl b: in A. hippocastanum and A. flava, in the sunlit crown part, the value of this indicator was significantly higher than in other species. This fact may be due to the fact that the changes in the chlorophyll content in the leaves discovered in the present study may be associated with a disruption in the biosynthesis or accelerated degradation of chlorophyll a and the accumulation of chlorophyll b [35]. Differences in the amount of carotenoids between horse chestnut species have also been shown previously. Thus, the carotenoid content in the leaves of A. × neglecta was significantly higher than in the susceptible species A. turbinata [14]. In our study, the highest carotenoid content was also shown in the resistant species A. parviflora, regardless of lighting conditions.

Moreover, a study of chlorophyll fluorescence indices revealed two opposing types of adaptation. Resilient species successfully combine high photochemical activity with an effective defense system, allowing them to minimize damage and maintain productivity under various conditions. Conversely, susceptible species have weak defense mechanisms; their photosynthetic apparatus operates inefficiently, and is chronically damaged, making them vulnerable in both sunlight and shade.

Biotic stress alters the quantitative content of not only pigments, but also proline and phenolic compounds, for example, in Fabaceae species [23]. It was shown that the amount of proline doubled in leaves after aphid (Chaitophorus nassonowi) infestation [36]. Under shade conditions, soybean plants showed an increase in total proline and some antioxidant content, indicating increased stress [37]. Lackner, S. and co-authors [24] showed that leaves with higher proline levels are preferred by Lymantria dispar, while, other studies have not found an increase in proline levels in Populus tremula after infestation by the sponge moth [36]. The lowest proline content was observed in species, such as A. parviflora, A. pavia and A. chinensis, which may be due to lower stress conditions and, accordingly, lower proline synthesis. In our study, a significant increase in proline content under shaded conditions was found in the most affected species A. hippocastanum and A. flava, which is consistent with another study [24]. Under shaded conditions, proline content in leaves decreased in the least populated species A. parviflora, A. pavia, and A. chinensis. The highest proline content, regardless of light conditions, among all species was observed in A. parviflora. This may be due to the fact that higher proline levels enhance the synthesis of phenolic compounds that are involved in plant defense [38,39]. Despite this, a positive effect of proline on the development of populations of some insects, such as aphids, has been shown [36].

Hydraulic conductivity, plant water status, and stomatal conductance underlie plant–insect interactions [39]. Changes in xylem fibers [40] and changes in hydraulic conductivity can also be associated with insect damage [41]. In A. chinensis, the lowest water content was found on the sunny side of the crown compared to other species. As a result, it can be noted that heavily infested A. hippocastanum and A. flava showed an increase in leaf water content under shaded conditions. Thus, no significant differences were shown between horse chestnut species under lighting conditions, but they were shown under shading conditions. This may be due to the fact that leaf miners disrupt the water-holding properties of the leaf by feeding on both the surface and deeper living tissues, which, in turn, leads to an increase in plant transpiration [42]. The decrease in raw biomass and changes in water content in general are due to a disruption in water exchange [43]. For example, leaves on the sunny side of the canopy had higher fresh weight per unit area, as well as dry weight, leaf blade thickness, vein and stomatal density, net photosynthetic rate, and stomata conductance compared to leaves on the shaded crown side [44,45]. The hydraulic conductance of leaves exposed to sunlight increased almost fourfold compared to the minimum values in the shadow [45]. The present planting is located within a dense arboretum, where other plants of the damaged species are absent. However, when studying open spaces, in addition to the characteristics of the species, the nature of the foliage lighting, and ecological and climatic conditions, it is necessary to take into account that adults overcome ranges from 7.9 to 12.6 km on average [46] and environmental factors, such as tree position relative to wind directions, may have an impact.

Hyperspectral imaging sensors are effective methods for detecting changes in plant health [47]. Changes in reflectance are caused by the biophysical and biochemical properties of plant tissue. Under stress, tissue color, leaf shape, and transpiration rate can change, as can the interaction of solar radiation with plants [48]. NDVI is a dimensionless index that characterizes vegetation as the difference between visible and near-infrared radiation. This index is one of the most commonly used for monitoring vegetation dynamics at regional and global scales [49]. However, in our case, the NDVI index did not reveal significant differences between horse chestnut species, making it unsuitable for detailed classification of tree species by water content.

The next index analyzed is the DSWI, which characterizes plant stress caused by water deficit and damage [50]. The sensitivity of the DSWI index to tree species differentiation was demonstrated in a previous study [50] on conifers (pine, spruce) and deciduous trees (hornbeam, oak). Our study also demonstrated differences between horse chestnut species, with the highest index demonstrated by most species and the lowest by A. × carnea and A. parviflora, regardless of lighting conditions. This index allowed us to distinguish between plant species regardless of crown lighting conditions.

The last of the three indices studied was the SIPI (structure-insensitive pigment index), which reflects the efficiency with which a plant can utilize incoming light for photosynthesis. Moreover, the greatest differences were found in the illuminated part of the crown. SIPI was highest in some severely affected horse chestnut species (A. glabra, A. flava, and A. pavia), while the lowest was found in A. hippocastanum, A. chinensis, A. × carnea, and A. parviflora. Therefore, this index can be used to evaluate plants, but not in shaded conditions, where the differences would be insignificant.

A high negative correlation was observed between the DSWI and SIPI coefficients and the chl a content in the sunlit part of the crown (r = −0.5 and below). However, a high positive correlation was found between the Fv/Fm and NPQ indices and the chl a content (r = 0.5 and above). Under shaded conditions, a negative correlation was found between the chl a content and the hyperspectral analysis indices and chlorophyll fluorescence indices (Table S1).

Interestingly, a weak positive correlation (r = 0.2–0.4) was observed between the DSWI, SIPI, and Y(NPQ) coefficients and the chl b content in the illuminated part of the crown. In all other cases, a weak negative correlation (r = −0.06–0.5) was found between the chl b content and the hyperspectral analysis indices and chlorophyll fluorescence indices (Table S3).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Place of Research and Plant Material

Collection of Aesculus species (Aesculus hippocastanum L., Aesculus glabra Willd, Aesculus flava Aiton, Aesculus pavia L., Aesculus × carnea Hayne, Aesculus parviflora Walter, Aesculus chinensis Bunge) in the arboretum territory in the Main Botanical Garden (MBG) of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) in Moscow (55.838° N, 37.588° E) was analyzed [51,52,53]. The Aesculus species trees in the arboretum’s collection range in age from 10 to 80 years old, so we selected freestanding trees with a clearly defined, open space on the south side to avoid shading. The collection is located in the center of a mixed forest, dominated by common oak and separated from other stands of horse chestnut and other species known to be susceptible to the ohrid leaf miner. The foliage beneath the trees is not cleared, and no treatments are carried out due to a ban on chemical treatments. Three trees of each of the seven species affected by the horse chestnut leaf miner were selected for the study (Aesculus chinensis Bunge). Only two young trees, relatively recently planted in the arboretum’s collection, were used in the experiments. In the year 2024, monitoring of plants was carried out, including an analysis of the number of the second generation of the horse chestnut leaf miner.

4.2. Estimation of Horse Chestnut Miner Abundance Using Pheromone Traps

Delta sticky pheromone traps with dispensers impregnated with the synthesized sex pheromone of female moths (Pheromon, Moscow, Russia) were hung on horse chestnut trees in different parts of the crown. The second generation of adults in the foliage of the horse chestnut collection was counted from July to August. Traps in three biological replicates on two to three trees were attached to horizontal branches of the outer part of the horse chestnut crown at a height of 1.5–2 m from the ground [31]. Sticky plates in the traps were extracted once.

Pheromone insect counting traps were attached to the branches of three trees of the each species being studied (one trap on each of the three trees of the same species, one on the sunny and one on the shaded side). One trap was hung 1.5–2 m above the ground, and the other on the opposite side of the tree. The distance between the trees was 2–3 m. In this study, the abundance of the generation of males of the horse chestnut leaf miner was investigated. Sticky plates in the traps were extracted once. A schematic representation of the arrangement of traps for capturing adult male ohrid leaf miner moths in the crowns of horse chestnut trees used in this study reflects the choice of location based on spatial orientation relative to cardinal directions to account for solar illumination when selecting isolated trees (Figure S9).

4.3. Morphometric Indicators

To determine the water content of leaves of seven horse chestnut species affected by C. ohridella, averaged 0.2 g samples were collected. Leaf biomass was determined gravimetrically using the Sartorius Analytical A200S (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). To determine dry biomass, leaves were dried at 65 °C to constant weight. Each experimental variant was performed in three biological replicates.

where RWC—relative water content (%), FW and DW—fresh and dry biomass of root or shoot part of seedling, respectively (mg).

RWC = [(FW − DW)/FW] × 100%

4.4. Determination of Leaf Pigment Content

The photosynthetic pigment content (chlorophylls a (chl a), and b (chl b) and carotenoids (Car)) were determined by extracting pigments from leaves with 96% ethyl alcohol [54]. The degree of solution absorption (optical density) for chlorophylls a and b, and carotenoids was determined using Genesys 20 spectrophotometer (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a wavelength of 665, 649 and 471 nm, respectively. Each experimental variant was performed in two analytical and three biological replicates. The pigment content (µg g−1 FW) was calculated by the formulas [55]:

where: C—pigment concentrations; D—optical density; V—extract volume; and n—leaf fresh weight [56].

Cchl a = 13.70D665 − 5.76 D649;

Cchl b = 25.80 D649 − 7.60 D665;

Ccar = (1000D471 × 2.13Cchl a − 97.64Cchl b)/209

A = C × V/1000 × n

4.5. Detection of Leaf Proline Content

Extraction and determination of free proline were performed according to Bates et al. (1973) with minor modifications [57]. A weighed sample of plant material weighing 0.1 g was triturated in liquid nitrogen. The ground material was transferred into test tubes and filled with 4 mL of distilled water. Test tubes with weighed samples were brought to a boil three times, cooling each time. The resulting extract was filtered into measuring tubes. The resulting extract was adjusted to the desired volume (6–7 mL) and then used for analysis. Tubes with 1 mL extract, 1 mL glacial acetic acid, 1 mL ninhydrin reagent (1.25 g ninhydrin, 20 mL 6M H3PO4, 30 mL CH3COOH) were incubated for 1 h in a boiling water bath. Instead of the extract, 1 mL of distilled water was added to the control sample. The optical density of the obtained colored solutions was measured on a PD-303 spectrophotometer (Apel, Saitama, Japan) against the control at a wavelength of 520 nm. Each experimental variant was performed in two analytical and three biological replicates. The proline content was calculated using the calibration curve according to the formula:

where: C—proline concentration, µM g−1 fresh weight, E—optical density, k—coefficient calculated from the calibration curve, V—extract volume, mL, W—sample weight, g.

C = Ek × V/(W × 1000),

4.6. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Characteristics

Chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics were determined on the leaf surface. Seedlings were kept in a dusky place for 30 min before the measurements. Modulated fluorescence was recorded with a portable chlorophyll fluorometer, the blue version Junior-PAM (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). This version is emitted between 400 and 500 nm with a maximum around 445 nm and is equipped with a far-red LED with maximal emission around 745 nm and an emission range from 675 to 800 nm. The least fluorescence value (F0) was measured for 30 min in dusky-adapted leaves using light of <0.1 µM photons/(m−2 s−1), the maximum fluorescence value (Fm) was recorded at 1000 µM photons/(m−2 s−1) photosynthetic photon flux density in the same leaves. The intensity of light driving photosynthesis (actinic radiation) (PAR)—190 µM photons/(m−2 s−1). The greater changeable fluorescence value (Fv = Fm − F0), the maximum photochemical quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm), the effective photochemical quantum yield of photosystem II (Y(II)), the electron transport rate, and µmol electrons/(m−2 s−1) (ETR = Y(II) × PAR × 0.84 × 0.5) were registered for dusky-adapted leaves. Each treatment was concluded with the use of three single leaves as three replications [58].

4.7. Determination of Hyperspectral Indices

The data were obtained using hyperspectral imaging (HSI) with the hyperspectral research Module M.Gk. Synergotron hyperspectral camera (Zolotoi Shar, Moscow, Russia). The Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) was determined using the following formula, where R is the hyperspectral measurement

NDWI = (R842 − R560)/(R840 − R560)

Disease Stress Water Index (DSWI) was determined using the following formula, where R is the hyperspectral measurement

DSWI = R550/R680

Structure Insensitive Pigment Index (SIPI) was determined using the following formula, where R is the hyperspectral measurement

SIPI = (R842 − R470)/(R842 − R705)

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical processing of experimental data was performed using parametric Student’s t-test and Fisher’s exact tests. Calculations were performed in the Statistica v. 12.0 PL (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA) program. Mean values ± SEM according to ANOVA at α = 0.05 are presented.

5. Conclusions

The most susceptible species were A. hippocastanum, A. glabra, A. flava, and A. × carnea, while the least susceptible were A. pavia, A. parviflora, and A. chinensis, regardless of crown illumination.

In the leaves of A. hippocastanum, A. glabra, and A. flava, the quantitative content of chl a was lowest on the illuminated side, while in the species least affected by leaf miners—A. pavia, A. parviflora, and A. chinensis—this indicator was highest. The opposite situation was observed for chl b.

The lowest proline content was observed in species, such as A. parviflora, A. pavia, and A. chinensis, which may be due to greater resistance to stress conditions, which resulted in lower proline synthesis. Impairment of leaf water-retention capacity due to leaf miner feeding is most characteristic of species heavily affected by leaf miners.

Hyperspectral analysis indices, DSWI and SIPI, were also successfully applied to assess injury to horse chestnut trees by the ohrid leaf miner. This opens the prospect of remote damage assessment when monitoring the condition of urban trees.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants15010086/s1, Table S1: Correlation between Hyperspectral Indices and Chlorophyll Content title; Table S2. Correlation between chestnut species, illumination and physiological and biochemical parameters; Table S3. Correlation between Hyperspectral Indices and Chlorophyll Content; Additional orthodox histograms are presented in the Materials Supplement Figures S1–S9.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.R.B.; methodology, L.R.B. and E.N.B.; validation, L.R.B. and E.N.B.; formal analysis, L.R.B., O.V.S., E.N.B. and A.A.G.; investigation, L.R.B., O.V.S., H.I.R., G.N.R. and E.N.B.; resources, O.V.S., E.N.B. and A.A.G.; data curation, L.R.B., O.V.S., H.I.R., G.N.R., E.N.B. and A.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.R.B.; writing—review and editing, L.R.B., E.N.B. and A.A.G.; visualization, E.N.B. and A.A.G.; supervision, E.N.B. and A.A.G.; project administration, E.N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially supported by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation: State Assignment No. 122042700044–6 (IPPRAS: H.I.R., G.N.R.), 124030100058-4 (MBG RAS: L.R.B., O.V.S., E.N.B.), FGUM-2025-0003 (All-Russia Research Institute of Agricultural Biotechnology: L.R.B., E.N.B., A.A.G.). Authors pay the APC from their own funds.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Vyacheslav V. Latushkin and the Center for Shared Equipment Use of the Independent NPO Institute for Development Strategies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| chl a | Chlorophyll a |

| chl b | Chlorophyll b |

| DSWI | Disease Water Stress Index |

| SIPI | Structure Insensitive Pigment Index |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index |

| F0 | Fluorescence value |

| PAR | The intensity of light driving photosynthesis (actinic radiation) |

| Fv | The greater changeable fluorescence value |

| Fm | The maximum fluorescence value |

| Y(II) | The quantum efficiency of PS II photochemistry |

| ETR | The electron transport rate |

| Car | Carotenoids |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| NAD+/NADP+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| RWC | Water content |

| FW | Fresh biomass of root or shoot part of seedling |

| DW | Dry biomass of root or shoot part of seedling |

| LED | Light-Emitting Diode |

| Fv/Fm | Maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) |

| NPQ | The regulated energy dissipation in PS II |

| Y(NPQ) | The quantum efficiency of regulated energy dissipation in PS II |

| Y(NO) | The quantum efficiency of non-regulated energy dissipation in PS II |

| r | Correlation |

References

- Prada, D.; Velloza, T.M.; Toorop, P.E.; Pridchar, H.W. Genetic population structure in horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum L.): Effect of human-mediated expansion in Europe. Plant Spec. Biol. 2011, 26, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freise, J.F.; Heitland, W. Neue Aspekte zur Biologie und Ökologie der Roßkastanien-Miniermotte, Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimic (1986) (Lep. Gracillariidae), einem neuartigen Schädling an Aesculus hippocastanum. Mitt. Dtsch. Ges. Allg. Angew. Entomol. 2001, 13, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kenis, M.; Girardoz, S.; Avtzis, N.; Kamata, N. Finding the area of origin of the horse-chestnut leaf miner: A Challenge. In Proceedings of the IUFRO Kanazawa 2003 Forest Insect Population Dynamics and Host Influences, Kanazawa, Japan, 14–19 September 2003; pp. 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ferracini, C.; Curir, P.; Dolci, M.; Lanzotti, V.; Alma, A. Aesculus pavia foliar saponins: Defensive role against the leafminer Cameraria ohridella. Pest Man. Sci. 2010, 66, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoutdinova, L.R.; Shelepova, O.V.; Konovalova, L.N.; Tkachenko, O.B.; Gulevich, A.A.; Baranova, E.N.; Mitrofanova, I.V. Susceptibility of different Aesculus species to the horse chestnut leaf miner moth: Chemical composition and morphological features of leaves. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2024, 5, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straw, N.A.; Tilbury, C. Host plants of the horse-chestnut leaf-miner (Cameraria ohridella), and the rapid spread of the moth in the UK 2002–2005. Arboricult. J. 2006, 29, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Costa, L.; Koricheva, J.; Straw, N.; Simmonds, M.J.S. Oviposition patterns and larval damage by the invasive horse-chestnut leaf miner Cameraria ohridella on different species of Aesculus. Ecol. Entomol. 2013, 38, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irzykowska, L.; Werner, M.; Bocianowski, J.; Karolewski, Z.; Frużyńska-Jóźwiak, D. Genetic variation of horse chestnut and red horse chestnut and susceptibility on Erysiphe flexuosa and Cameraria ohridella. Biologia 2013, 68, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popitanu, C.; Lupitu, A.; Copolovici, L.; Bungău, S.; Niinemets, Ü.; Copolovici, D.M. Induced volatile emissions, photosynthetic characteristics, and pigment content in Juglans regia leaves infected with the Erineum-forming mite Aceria erinea. Forests 2021, 12, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holoborodko, K.; Seliutina, O.; Alexeyeva, A.; Brygadyrenko, V.; Ivanko, I.; Shulman, M.; Pakhomov, O.; Loza, I.; Sytnyk, S.; Lovynska, V.; et al. The impact of Cameraria ohridella (Lepidoptera, Gracillariidae) on the state of Aesculus hippocastanum photosynthetic apparatus in the urban environment. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2022, 13, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralvarez-Marin, A.; Bourdelande, J.L.; Querol, E.; Padros, E. The role of proline residues in the dynamics of transmembrane helices: The case of bacteriorhodopsin. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2006, 23, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Stewart, J.J.; López-Pozo, M.; Polutchko, S.K.; Adams, W.W. Zeaxanthin, a molecule for photoprotection in many different environments. Molecules 2020, 25, 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.L.; Joern, A. Dietary selection and nutritional regulation in a common mixed-feeding insect herbivore. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2013, 148, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterska, M.; Bandurska, H.; Wysłouch, J.; Molińska-Glura, M.; Moliński, K. Chemical composition of horse-chestnut (Aesculus) leaves and their susceptibility to chestnut leaf miner Cameraria ohridella Deschka & Dimić. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2017, 39, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-Yadun, S.; Gould, K.S. Role of Anthocyanins in plant defence. In Anthocyanins; Winefield, C., Davies, K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kočíková, L.; Miklisová, D.; Čanády, A.; Panigaj, L. Is colour an important factor influencing the behavior of butterflies (Lepidoptera: Hesperioidea, Papilionoidea)? Europ. J. Entomol. 2012, 109, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgou, P.; Buschmann, C.; Manetas, Y. Red leaf color as a warning signal against insect herbivory: Honest or mimetic? Flora 2008, 203, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johne, A.B.; Weissbecker, B.; Schütz, S. Reduzierung der Eiablage von C. ohridella (Deschka & Dimic) durch repellents. Nachr. Deut. Pflanz. 2006, 58, 260–261. [Google Scholar]

- Jagiełło, R.; Baraniak, E.; Guzicka, M.; Karolewski, P.; Łukowski, A.; Giertych, M.J. One step closer to understanding the ecology of Cameraria ohridella (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae): The effects of light conditions. Eur. J. Entomol. 2019, 116, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Niinemets, Ü.; Poorter, L.; Wright, I.J.; Villar, R. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): A meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 565–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, F.; Ghirardelli, L.A.; Nardini, A.; Salleo, S. Impact of the leaf miner Cameraria ohridella on photosynthesis, water relations and hydraulics of Aesculus hippocastanum leaves. Trees 2003, 17, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmieć, K.; Rubinowska, K.; Michałek, W.; Sytykiewicz, H. The effect of galling aphids feeding on photosynthesis photochemistry of elm trees (Ulmus sp.). Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movahedi, A.; Almasi, Z.Y.A.; Wei, H.; Rutland, P.; Sun, W.; Mousavi, M.; Li, D.; Zhuge, Q. Plant secondary metabolites with an overview of Populus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackner, S.; Lackus, N.D.; Paetz, C.; Köllner, T.G.; Unsicker, S.B. Aboveground phytochemical responses to belowground herbivory in poplar trees and the consequence for leaf herbivore preference. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 3293–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caretto, S.; Linsalata, V.; Colella, G.; Mita, G.; Lattanzio, V. Carbon fluxes between primary metabolism and phenolic pathway in plant tissues under stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 26378–26394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.; Kim, J.; Yu, J.-K.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, D.-W.; Kim, K.-H.; Lee, C.W.; Chung, Y.S. Review: Cost-effective unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) platform for field plant breeding application. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, I.Y.; Shishkonakova, E.A.; Prudnikova, E.Y.; Vindeker, G.V.; Grubina, P.G. About effect of weeds on spectral reflectance properties of winter wheat canopy. Sel’skokhozyaistvennaya Biol. 2020, 55, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpanev, A.M.; Smuk, V.V. Changes in the spectral characteristics of cultivated and weed plants under the influence of mineral fertilizers in agrocenoses of the North-West of Russia. Sovr. Probl. DZZ Kosm. 2022, 19, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shpanev, A.M.; Rusakov, D.V. Application of spectral indices to assess the influence of crop weeds and nitrogen nutrition on the activity of the photosynthetic apparatus of plants and the yield of winter triticale. Sovr. Probl. DZZ Kosm. 2024, 21, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoutdinova, L.R.; Tkacheva, E.V.; Konovalova, L.N.; Tkachenko, O.B.; Olekhnovich, L.S.; Gulevich, A.A.; Baranova, E.N.; Shelepova, O.V. Effect of sun exposure of the horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum L.) on the occurrence and number of Cameraria ohridella (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae). Forests 2023, 14, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.T.; Wu, X.; Luo, Z.B.; Tang, L.D.; Gao, J.Y.; Zang, L.S. Light intensity differentially mediates the life cycle of lepidopteran leaf feeders and stem borers. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4216–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Costa, L.E. Resistance and Susceptibility to the Invasive Leaf Miner Cameraria ohridella Within the Genus Aesculus. Ph.D. Thesis, University of London, London, UK, 2014; pp. 495–505. [Google Scholar]

- Johne, A.B.; Weissbecker, B.; Schütz, S. Volatile emissions from Aesculus hippocastanum induced by mining of larval stages of Cameraria ohridella influence oviposition by conspecific females. J. Chem. Ecol. 2006, 32, 2303–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terashima, I.; Hanba, Y.T.; Tazoe, Y.; Vyas, P.; Yano, S. Irradiance and phenotype: Comparative eco-development of sun and shade leaves in relation to photosynthetic CO2 diffusion. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastierovič, F.; Kalyniukova, A.; Hradecký, J.; Dvořák, O.; Vítámvás, J.; Mogilicherla, K.; Tomášková, I. Biochemical responses in Populus tremula: Defending against sucking and leaf-chewing insect herbivores. Plants 2024, 13, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.B.; Rawale, G.B.; Pradhan, A.; Uthappa, A.R.; Kakade, V.D.; Morade, A.S.; Reddy, K.S. Optimizing tree shade gradients in Emblica officinalis-based agroforestry systems: Impacts on soybean physio-biochemical traits and yield under degraded soils. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Salh, P.K.; Singh, B. Role of defence enzymes and phenolics in resistance of wheat crop (Triticum aestivum L.) towards aphid complex. J. Plant Interact. 2017, 12, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.H.; Li, X.H.; Xue, W.J.; Yang, H.Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Yu, Y.S.; Yang, U.Z. Impacts of four biochemicals on population development of Aphis gossypii Glover. J.-Yangzhou Univ. Agric. Life Sci. Ed. 2005, 26, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gely, C.; Laurance, S.G.W.; Stork, N.E. How do herbivorous insects respond to drought stress in trees? Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillabrand, R.M.; Hacke, U.G.; Lieffers, V.J. Defoliation constrains xylem and phloem functionality. Tree Physiol. 2019, 39, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ruiz, J.M.; Cochard, H.; Delzon, S.; Boivin, T.; Burlett, R.; Cailleret, M.; Corso, D.; Delmas, C.E.L.; De Caceres, M.; Diaz-Espejo, A.; et al. Plant hydraulics at the heart of plant, crops and ecosystem functions in the face of climate change. New Phytol. 2024, 241, 984–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, F.; Trifilò, P.; Gullo, M.A.L. Does citrus leaf miner impair hydraulics and fitness of citrus host plants? Tree Physiol. 2013, 33, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellin, A.; Õunapuu, E.; Kupper, P. Effects of light intensity and duration on leaf hydraulic conductance and distribution of resistance in shoots of silver birch (Betula pendula). Physiol. Plant. 2008, 134, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Õunapuu-Pikas, E.; Sellin, A. Plasticity and light sensitivity of leaf hydraulic conductance to fast changes in irradiance in common hazel (Corylus avellana L.). Plant Sci. 2020, 290, 110299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augustin, S.; Guichard, S.; Heitland, W.; Freise, J.; Svatoš, A.; Gilbert, M. Monitoring and dispersal of the invading Gracillariidae Cameraria ohridella. J. Appl. Entomol. 2009, 133, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niakan, M.; Ahmadi, A. Effects of foliar spraying kinetin on growth parameters and photosynthesis of tomato under different levels of drought stress. Iran J. Plant Physiol. 2014, 4, 939–947. [Google Scholar]

- Che’Ya, N.N.; Mohidem, N.A.; Roslin, N.A.; Saberioon, M.; Tarmidi, M.Z.; Arif Shah, J.; Fazlil Ilahi, W.F.; Man, N. Mobile computing for pest and disease management using spectral signature analysis: A Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandi, S.S. Natural UV Radiation in Enhancing Survival Value and Quality of Plants; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ashok, A.; Rani, H.P.; Jayakumar, K.V. Monitoring of dynamic wetland changes using NDVI and NDWI based Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 23, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochenek, Z.; Ziolkowski, D.; Bartold, M.; Orlowska, K.; Ochtyra, A. Monitoring forest biodiversity and the impact of climate on forest environment using high-resolution satellite images. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 51, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, J.W. A Revision of the American Hippocastanaceae-II. Brittonia 1957, 9, 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, J.W. Studies in the Hippocastanaceae, V. Species of the Old World. Brittonia 1960, 12, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlyk, A.A. Definition of a Chlorophyll and Carotenoids in Extracts of Green Leaves. In Biochemical Methods in Physiology of Plants; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987, 148, 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Bogoutdinova, L.R.; Khaliluev, M.R.; Chaban, I.A.; Gulevich, A.A.; Shelepova, O.V.; Baranova, E.N. Salt tolerance assessment of different tomato varieties at the seedling stage. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelepova, O.V.; Baranova, E.N.; Sudarikov, K.A.; Savostyanova, L.I.; Mitrofanova, I.V. Parameters of photosynthetic activity as markers of biotic stress in Chrysanthemum coreanunum (H. Lév. & Vaniot) Nakai ex T. Mori. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 72, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.