Abstract

×Trititrigia cziczinii Tzvelev is a promising crop developed through distant hybridization between Elytrigia intermedia (Host) Nevski (=Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth & D.R. Dewey) and Triticum aestivum L., followed by backcrossing with wheat. This study elucidates the genomic composition of this hybrid and its parental taxa using molecular phylogenetic analysis of nuclear (ITS, ETS) and chloroplast (trnK–rps16, ndhF) DNA markers, complemented by Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) of the 18S–ITS1–5.8S rDNA region. Results from Sanger sequencing revealed that the primary nuclear ribosomal DNA (rDNA) of the hybrid originates from Triticum aestivum; a finding strongly supported by both Bayesian inference and Maximum Likelihood analyses. Chloroplast DNA data unequivocally indicate maternal inheritance from T. aestivum. In contrast, ETS sequence analysis showed phylogenetic affinity to Elytrigia intermedia, suggesting complex genomic reorganization or chimeric sequence formation in the hybrid. NGS data corroborate the dominance of T. aestivum-like ribotypes in the hybrid’s rDNA pool, with only a minor fraction identical to the main ribotype of E. intermedia. Genetic structure analysis further revealed geographic heterogeneity in the genomic composition of E. intermedia populations. The predominance of the wheat genome in ×T. cziczinii is likely a consequence of stabilizing backcrosses and illustrates a case of rDNA elimination from one parental genome during hybridization. This research underscores the complex genomic dynamics in artificial hybrids and the utility of multi-marker phylogenetic approaches for clarifying their origins.

1. Introduction

As is well known, interspecific and intergeneric hybridization is widespread in angiosperms. For a long time, evidence of a species’ hybrid origin was considered to be the presence of morphological traits shared by other species growing nearby, or an intermediate state of some morphological traits between the putative parents. After it became possible to study molecular traits and compare genomic regions, it was discovered that in some plants, the DNA sequence of the compared region contains traits (nucleotides) from two different species, indicating that the plant is a hybrid. However, sometimes the presence or intermediate state of the parental morphological traits is weakly expressed or completely absent.

The study of hybrids at the genetic level is of great importance. The genetic pattern of hybrids can be complex, as it can be represented by two parental subgenomes, but sometimes the subgenome of one parent can be eliminated. Furthermore, a hybrid can undergo backcrosses with one (or both) parents, and such introgression processes influence the genomic constitution.

A better understanding of the structure of hybrid genomes can be achieved by studying artificial hybrids obtained specifically. Distant hybridization has very broad potential for harnessing the genomic potential of wild relatives to improve existing crop varieties and develop new ones for agricultural production. There is currently a tendency to crossbreed in a narrow range of varieties used as source material in wheat breeding. Continuing this trend leads to genetic erosion: loss of genetic diversity, including genes and entire gene complexes that are characteristic of plants adapted to certain environmental conditions [1,2,3]. This leads to the impoverishment of the genetic base of the agricultural crop varieties used and developed [1]. N. I. Vavilov recommended involving both geographically distant wheat accessions and wild-growing relatives in selection to expand the wheat gene pool [4].

For our molecular phylogenetic analysis, we took ×Trititrigia cziczinii Tzvelev (tribe Hordeeae Martinov = Triticeae Dumort.), cultivar “In Memory of Lyubimova”. It is known that this variety was created as a result of intergeneric hybridization of couch grass Elytrigia intermedia (Host) Nevski (=Thinopyrum intermedium (Host) Barkworth & D.R. Dewey) and Triticum aestivum L. with subsequent backcrosses with Triticum aestivum. According to morphological features, it occupies an intermediate position between the parent taxa with a bias towards wheat features [5,6,7]. Its genome contains 56 chromosomes (42 from wheat and 14 from couch grass) [6]. A distinctive feature of this variety is the intensive growth of new shoots after ripening and harvesting of a grain, which allows, under favorable conditions, for obtaining both a grain harvest and a green mass harvest during the growing season [6]. In addition, it has a high content of protein and gluten in the grains [5]. It is resistant to fusarium, smut, and brown rust [6]. All these features allow us to consider this hybrid a promising agricultural crop, and it is important to know in detail its genome composition.

We used for an analysis the nuclear ITS1–5.8S rDNA–ITS2, 18S rDNA–ITS1–5.8S rDNA, and 3′-ETS regions as well as chloroplast trnK–rps16 and ndhF sequences. The level of their variation is suitable for evolutionary studies at the species level; ITS and trnK–rps16 spacers are often applied for DNA barcoding [8,9]. ITS sequences, despite their susceptibility to homogenization, have often been used for phylogenetic reconstruction in complicated and highly hybridized groups for almost a quarter of a century [10,11,12,13]. External transcribed spacer (ETS) of rDNA is closely related to ITS, evolves at a similar rate and is regarded as a useful tool for phylogenetic analysis though is used less frequently [14]. Chloroplast sequences are mostly inherited uniparentally through the maternal line [15,16]. Thus, these sequences can be used for phylogenetic reconstruction of the barley tribe species (Hordeeae) where hybridization is widely distributed and is one of the main evolutionary pathways [17,18,19,20]. Chloroplast sequences trnK–rps16 and ndhF usually evolve more slowly than ITS, but they are invaluable for constructing independent phylogenies in the case of introgressive hybridization. In addition, NGS technologies now make it possible to obtain the entire pool of the marker sequences, including hidden ones left over from ancient hybridization processes and not detectable by other methods, including cloning. For example, intragenomic polymorphism of different sequences was studied in genera Hordeum L., Nepenthes L., and Abies Mill. [21,22,23].

Given the above, our aim was to establish the possible genomic combination of the hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii and compare it with those of their parental taxa using marker sequences of the nuclear and chloroplast genomes.

2. Results

2.1. Sanger Sequencing Data

A list of the studied species is given in Table 1. The region ITS1–5.8S rDNA–ITS2 contains 613 aligned positions. Analysis of ITS sequences that were obtained by Sanger method clearly indicated the origin of the main rDNA in ×Trititrigia cziczinii from Triticum aestivum. Triticum durum Desf. also fell within this subclade (PP = 1, BS = 100) (Figure 1). The subclade of ×Trititrigia cziczinii, Triticum aestivum, and T. durum is sister to Elymus komarovii (Nevski) Tzvelev in moderately supported clade (PP = 0.86, BS = 73).

Table 1.

List of the Hordeeae species used in the study.

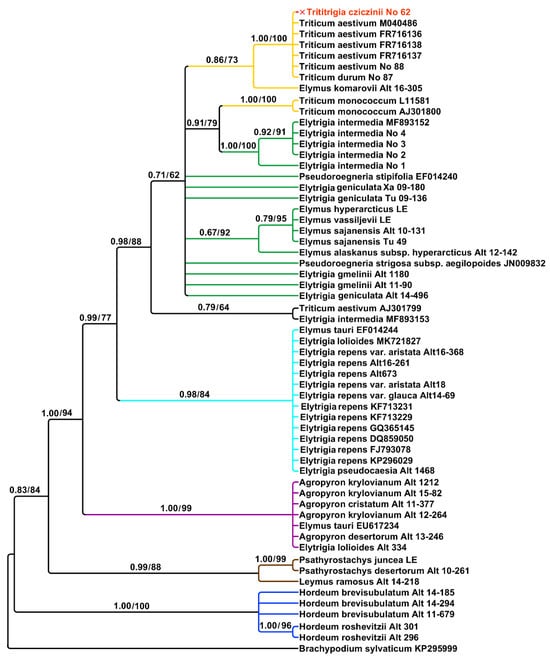

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii, parental taxa, and allied genera according to the ITS data (Sanger method). The first index near the tree nodes is the posterior probability in Bayesian inference, the second is bootstrap value calculated by Maximum Likelihood analysis.

The tree is moderately to strongly supported (Figure 1). According to the ITS data, not only different genera but also rDNA sequences of the different genomes formed separate clades. Diploid Triticum monococcum L. fell outside the ×Trititrigia Tzvelev + T. aestivum clade and was monophyletic with samples of Elytrigia intermedia (PP = 0.91, BS = 79). Studied samples of Triticum and ×Trititrigia cziczinii form one large clade with Arctic species of Elymus, Elytrigia gmelinii, and Pseudoroegneria stipifolia (PP = 0.71, BS = 62). Arctic species of Elymus form a weakly to moderately supported subclade (PP = 0.67, BS = 92). Triticum aestivum and Elytrigia intermedia from Genbank form a separate clade (PP = 0.79, BS = 64). Elytrigia repens (L.) Nevski (=Elymus repens (L.) Gould) forms a strongly supported clade with Elytrigia lolioides (Kar. & Kir.) Nevski, E. pseudocaesia (Pacz.) Prokudin, and Elymus tauri (Boiss. & Balansa) Melderis (PP = 0.98, BS = 84). Studied samples of Agropyron krylovianum Schischk., A. cristatum (L.) Gaertn., and A. desertorum (Fisch. ex Link) Schult. are placed in a maximally supported clade with the samples of Elytrigia lolioides and Elymus tauri (PP = 1, BS = 0.99) probably forming a clade of P-genome. Samples of Psathyrostachys Nevski are monophyletic with Leymus Hochst. (PP = 0.99, BS = 88), studied samples of the genus Hordeum L. (subgenus Critesion (Raf.) Tzvelev) are also monophyletic (PP = 1, BS = 100).

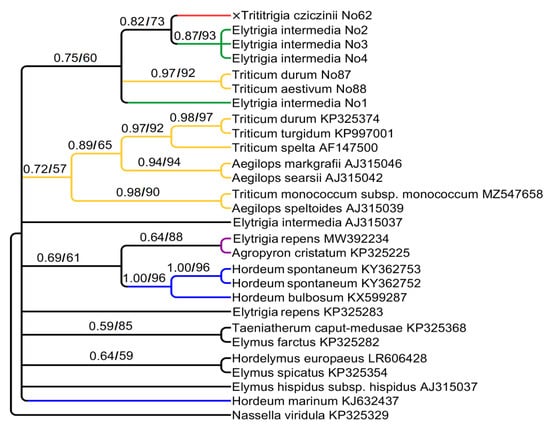

We analyzed 3′-ETS of 18S rDNA. Its alignment consists of 303 positions. The ETS tree (Figure 2) is less supported than the previous one. Unexpectedly, ETS sequences of ×Trititrigia cziczinii turned to be sister to Elytrigia intermedia (PP = 0.82, BS = 73). ETS sequence of Triticum aestivum groups with T. durum (PP = 0.97, BS = 92) and does not group with ×Trititrigia cziczinii. Other Triticum samples from Genbank database fall into a clade with Aegilops L. according to ETS data. Additionally, Elytrigia repens groups with Agropyron cristatum (probably P-genome). ETS sequences of Hordeum species enter three different clades on the tree.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii, parental taxa, and allied genera according to the ETS data (Sanger method). The first index is the posterior probability in Bayesian inference, the second is bootstrap value calculated by Maximum Likelihood analysis.

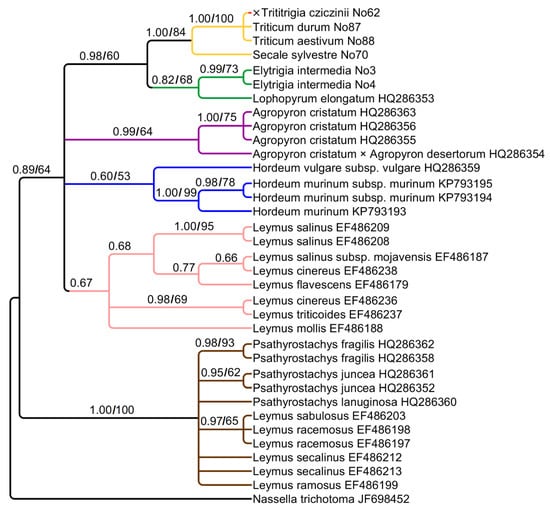

For independent assessment of phylogeny, we analyzed two chloroplast regions: trnK–rps16 and ndhF. Chloroplast sequences trnK–rps16 have 711 aligned positions. They form weakly to strongly supported clades (Figure 3). ×Trititrigia cziczinii has maternal genome of Triticum aestivum (PP = 1, BS = 100) falling into a clade with Secale sylvestre Host (PP = 1, BS = 84). The clade containing ×Trititrigia + Triticum + Secale L. is sister to the clade of Elytrigia intermedia + Lophopyrum elongatum (Host) Á. Löve (PP = 0.98, BS = 60).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii, its parental taxa, and allied genera according to the trnK–rps16 data (Sanger method). The first index is the posterior probability in Bayesian inference, the second is bootstrap value calculated by Maximum Likelihood analysis. When only one index is shown on the tree, it is the posterior probability index.

There are the clades that comprise Agropyron Gaertn. (PP = 0.99, BS = 64), Hordeum (PP = 60, BS = 53), and Leymus (PP = 0.67) that form large clade along with Triticum and Elytrigia intermedia (PP = 0.89, BS = 64). The genus Psathyrostachys forms the second large clade (PP = 1, BS = 100). This clade also includes some species of the genus Leymus from the complexes L. racemosus (Lam.) Tzvelev and L. sabulosus (M.Bieb.) Tzvelev.

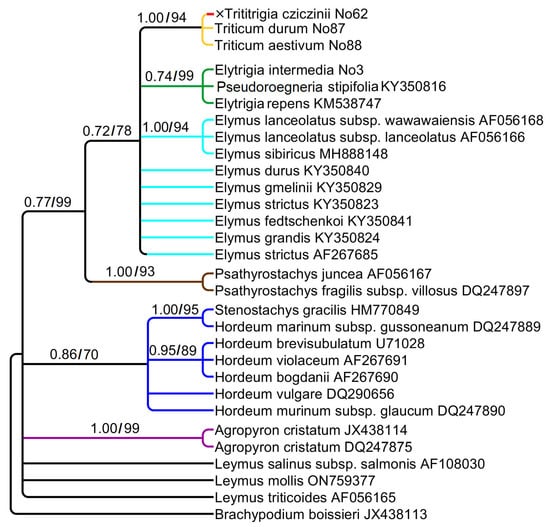

The studied sequences of ndhF comprise 663 aligned positions. The phylogenetic tree based on ndhF sequence data is rather similar to the trnK–rps16 tree but less supported (Figure 4). ×Trititrigia cziczinii has the chloroplast sequences of Triticum aestivum and Triticum durum (PP = 1, BS = 94). Elytrigia intermedia forms a clade with Pseudoroegneria stipifolia and Elytrigia repens (PP = 0.74, BS = 99). Species of the genus Elymus occupy an uncertain position in the large clade Triticum + Elytrigia + Elymus. The genus Psathyrostachys has a sister position to this clade (PP = 0.77, BS = 99).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii parental taxa, and allied genera according to the ndhF data (Sanger method). The first index is the posterior probability in Bayesian inference, the second is bootstrap calculated by Maximum Likelihood analysis.

Stenostachys gracilis (Hook.f.) Connor falls into a clade with the species of Hordeum (PP = 0.86, BS = 70) and is monophyletic with Hordeum marinum Huds. subsp. gussoneanum (Parl.) Thell. (PP = 1, BS = 95) possibly revealing H-genome. Some ndhF sequences of the genus Leymus have an uncertain position on the tree.

2.2. NGS Data, Ribotype Network and Tree

For more precise tracking hybridization events, we built a network of the ITS 1 ribotypes obtained by NGS analysis. The alignment of 257 sequences consists of 346 positions. Major ribotypes (more than 1% per rDNA pool) are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of the major ribotypes of hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii and parental species.

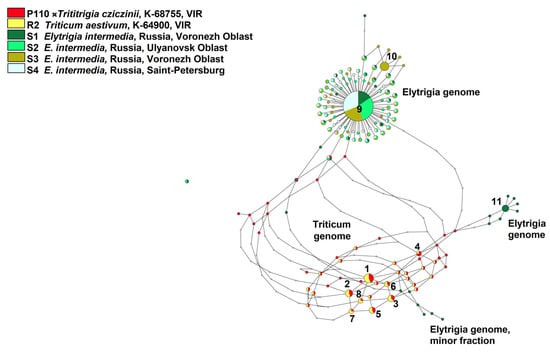

Ribotype network made by statistical parsimony method shows that the major ribotypes of ×Trititrigia cziczinii belongs to Triticum aestivum (Figure 5) and are identical to its major ribotypes. In this case, we considered ribotypes with more than 1% of reads per the rDNA pool of the sample as major ones. The most part of the studied rDNA from ×T. cziczinii is related to T. aestivum.

Figure 5.

Ribotype network of the artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii and its parental taxa based on NGS data built by Statistical Parsimony algorithm. The diameter of the circles is proportional to the percentage of the major ribotype to the total number of reads in the sample.

Only a minor fraction of ×T. cziczinii ribotypes (64 reads) is identical to the main ribotype of all studied Elytrigia intermedia samples (1990 reads, 25% of the whole rDNA pool; 4225 reads, 49%; 3792 reads, 41%, and 4392 reads, 53%, respectively). The second major ribotype of E. intermedia from Voronezh Oblast, sample S1 (600 reads, 8%) is rather distantly related to other ribotypes of the studied E. intermedia. The ribotypes of E. intermedia sample S1 also form a small subnetwork that is more closely related to Triticum-ribotypes than the main ribotype of E. intermedia. Additionally, E. intermedia sample S3 from Voronezh Oblast has a specific second major ribotype (1326 reads, 14%) that is closely related to the main ribotypes of all studied E. intermedia.

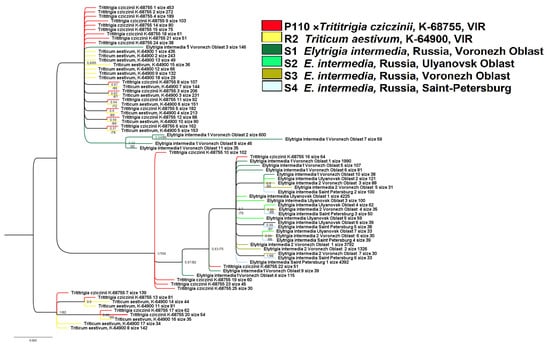

The phylogenetic tree of the studied ribotypes splits into three large clades (Figure 6). In this case, we set a threshold of 30 reads per rDNA pool. The first clade unites major ribotypes of ×T. cziczinii with these of Triticum aestivum (PP = 0.8, BS = 66).

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree of the studied ITS 1 ribotypes depicting origin of the artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii. The first index on the tree node is a posterior probability (Bayesian inference); the second is a bootstrap value (ML method).

Ribotypes of Elytrigia intermedia S1 (Voronezh Oblast) occupy an uncertain position within this clade. A separate subgroup within this large clade is formed by ribotypes of E. intermedia S1 (PP = 0.99, BS = 95) including the second major ribotype (600 reads). The next large clade (PP = 1, BS = 100) on the ribotype tree comprises the most part of the ribotypes of E. intermedia and some ribotypes of ×Trititrigia cziczinii. Only two ribotypes of ×T. cziczinii fall into subclade 7) with E. intermedia ribotypes, other ribotypes of ×T. cziczinii form a polytomy. The third small clade consists of the ribotypes of ×T. cziczinii and Triticum aestivum (PP = 1, BS = 82).

2.3. NGS Data, Ribotype Composition of the Studied Samples

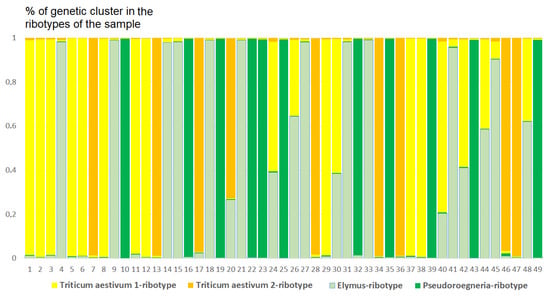

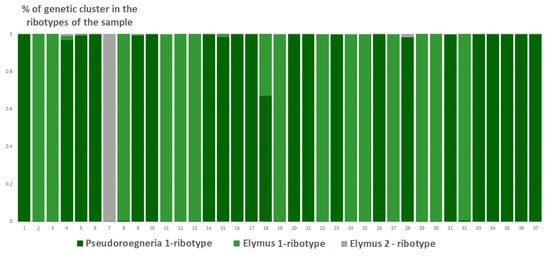

Analysis of the ribotype sets in studied samples performed by Structure software clustering revealed different quantities of the possible ancestral ribotypes in ×Trititrigia cziczinii (Figure 7). An estimated number of genetic clusters reflects ribotype composition within a given sample, and not between samples.

Figure 7.

Genetic clustering of ×Trititrigia cziczinii (K = 4). The genetic clusters correspond to the probable ancestral ribotypes within the studied sample. They are named after the most similar sequences from the Genbank database. The number of columns corresponds to the number of ribotypes within the sample.

The studied sample of ×Trititrigia cziczinii has four estimated ancestral ribotypes (K = 4) in its rDNA. Two estimated ancestral ribotypes belong to T. aestivum-group, and one belongs to Pseudoroegneria (Nevski) Á. Löve (=diploid Elytrigia); the most similar species to Pseudoroegneria-ribotype is P. stipifolia. The fourth ancestral ribotype is Elymus-like, the most similar to ×Elyhordeum kirbyi M.P.Wilcox and Elymus caninus L.

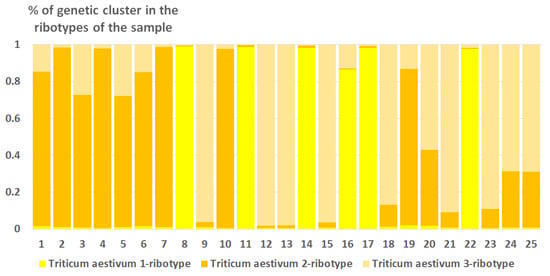

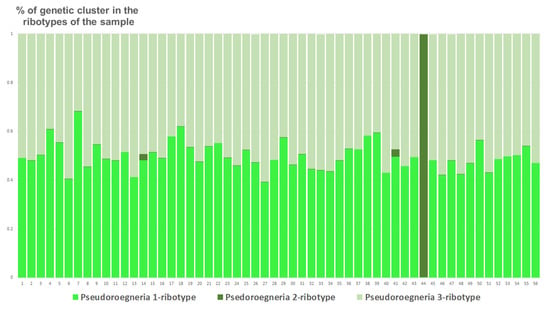

Ribosomal DNA of Triticum aestivum consists of three estimated ancestral ribotypes (K = 3); all of them belong to the T. aestivum-ribotype family (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Genetic clustering of Triticum aestivum (K = 3). The genetic clusters correspond to the probable ancestral ribotypes within the studied sample. They are named after the most similar sequences from the Genbank database. The number of columns corresponds to the number of ribotypes within the sample.

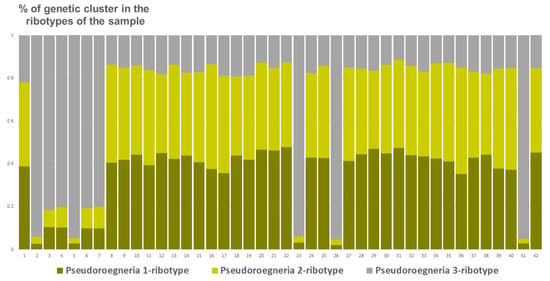

Studied Elytrigia intermedia samples differ in the number of estimated ancestral ribotypes. The first estimated ancestral ribotype of the first sample of E. intermedia from Voronezh Oblast (S1) belongs to Pseudoroegneria-ribotype group (K = 3); the closest species is diploid Pseudoroegneria stipifolia (Figure 9). The second estimated ancestral ribotype of E. intermedia S1 is similar to those of Elymus nevskii Tzvelev and ×Elyhordeum kirbyi (Figure 9). The third probable ancestral ribotype is similar to ×Elyhordeum kirbyi and Elymus caninus ITS sequences (Figure 9). Two studied samples of Elytrigia intermedia, S2 and S3 from Ulyanovsk and Voronezh Oblast, Russia, respectively, have three estimated ancestral ribotypes in their rDNA (K = 3 for both samples, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11). All these ribotypes belong to the Pseudoroegneria-ribotype family.

Figure 9.

Genetic clustering of Elytrigia intermedia, from Voronezh Oblast, Russia, sample S1 (K = 3). The genetic clusters correspond to the probable ancestral ribotypes within the studied sample. They are named after the most similar sequences from the Genbank database. The number of columns corresponds to the number of ribotypes within the sample.

Figure 10.

Genetic clustering of Elytrigia intermedia, sample S2 from Ulyanovsk Oblast, Russia (K = 3). The genetic clusters correspond to the probable ancestral ribotypes within the studied sample. They are named after the most similar sequences from the Genbank database. The number of columns corresponds to the number of ribotypes within the sample.

Figure 11.

Genetic clustering of Elytrigia intermedia, from Voronezh Oblast, Russia, sample S3 (K = 3). The genetic clusters correspond to the probable ancestral ribotypes within the studied sample. They are named after the most similar sequences from the Genbank database. The number of columns corresponds to the number of ribotypes within the sample.

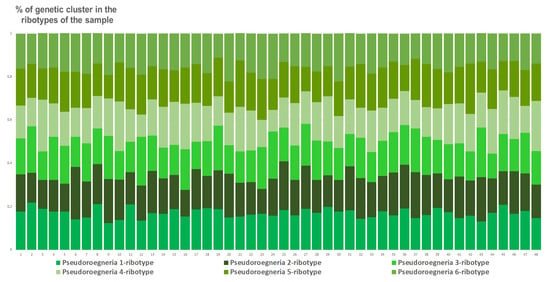

The sample of E. intermedia from St. Petersburg, Russia, has the most structure of the estimated ancestral ribotypes. It contains six estimated ancestral ribotypes (K = 6). They all are similar to Pseudoroegneria (mostly P. stipifolia) (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Genetic clustering of Elytrigia intermedia, from St. Petersburg, Russia, sample S4 (K = 6). The genetic clusters correspond to the probable ancestral ribotypes within the studied sample. They are named after the most similar sequences from the Genbank database. The number of columns corresponds to the number of ribotypes within the sample.

3. Discussion

According to modern data, distant hybridization, accompanying polyploidization, is one of the most important directions of plant evolution. Recent molecular phylogenetic studies indicated that all contemporary flowering plants have undergone several acts of polyploidization in their evolutionary history [26,27]. The grass family, for example, passed through at least three rounds of polyploidization affecting main clades of the grasses [28]. Furthermore, intergeneric (and probably even intertribal) hybridization between the species occurred on the border of the tribes of Pooideae subfamily—former tribes Poeae and Aveneae [29,30,31,32,33]. The genera Deschampsia P.Beauv., Vahlodea Fr., Aira L., and Avenula (Dumort.) Dumort. (members of subtribe Airinae Fr.) could originate from intercrossing between relatives of Avena L. (Aveneae chloroplast group—[30,33]) and species from the tribe Poeae s. str. related to Festuca L. [29,32]. The genus Psathyrostachys, a member of the important tribe Hordeeae, probably hybridized (or accessed genes via horizontal transfer) with Bromus L. from allied tribe Bromeae Dumort. [16,20]. Thus, the grass species are very complex systems containing different genomes received from distantly related taxa, and these genomes can be in a state of balance. Our study can shed more light on the events of distant hybridization whereas morphological features can be hidden due to prolonged introgression.

The history of studying the genomic structure of the wheat tribe goes back decades. According to cytogenetic data, the species of Triticum (wheat) consist mainly of three subgenomes—A, B, and D [34,35,36]. D-genome was probably inherited from Aegilops tauschii Coss. [25,37,38,39,40,41]. Diploid wheat T. urartu Thumanjan ex Gandiljan was a donor of A-genome whereas some unidentified Aegilops species gave origin to B-genome [25]. Triticum aestivum, parental species for ×Trititrigia cziczinii, is hexaploid with the genome structure ABD [20,34,35,42,43]. The genus Elytrigia is taxonomically complicated; some species were transferred from this genus to other genera [17,18,43,44]. It was divided into several genera according to its genomic structure: Pseudoroegneria (St), Lophopyrum Á. Löve (E), Thinopyrum Á. Löve (J), Elytrigia (EJSt), and Elymus (StH) [17]. Dewey [18] treated Elytrigia s. l. as three independent genera: Pseudoroegneria (St), Thinopyrum (E or J), and Elytrigia (StX). Some studies identified similarity between E and J-genomes [45,46,47,48]. In addition, some researchers treated Elytrigia repens, a type species of the genus as Elymus repens since it has StStStStHH genomes [43,44,49,50]. As a result, the position of the genus Elytrigia turns out to be more complex and confusing than in the old systems built on morphological criteria. However, in this case, it seems to us more correct to use the morphological criterion to determine the boundaries of the genus Elytrigia. At the same time, we acknowledge some taxonomic clarifications, particularly concerning diploids (Pseudoroegneria). As for morphology, the species of the genus Elytrigia s. l. have glumes keeled at the upper part; sessile spikelets, a dent at the base of the glume, and their inflorescences are erect. Diploid species that now belong to Pseudoroegneria differ by their caespitose form. Elytrigia intermedia, a parent for ×Trititrigia cziczinii, is a hexaploid species with ESt genome combination [24].

The hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii studied by us is artificial, meaning that we can clearly identify the parental taxa and the genomic contribution of each. According to NGS data (ITS1 sequences), it is the ribotypes of Triticum aestivum that are most represented in the rDNA of the hybrid (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Ribosomal DNA of T. aestivum, in turn, originated from Triticum s. str. (A-genome from T. urartu) based on our analysis and not from a hypothetical progenitor from the genus Aegilops. The dominance of Triticum aestivum rDNA in the hybrid is probably due to backcrosses with this species undertaken by breeders to stabilize the genome of the distant hybrid. Mechanisms of selection between rDNA from different genomes have not yet been fully studied. According to modern data, nucleolar dominance involves various mechanisms of intranuclear regulation, primarily selective methylation of rDNA loci [25]. Dysploidy in plants (i.e., chromosome elimination in complex distant hybrids) can occur in two different ways [51]. In the artificial hybrids of two evolutionary different large clades, as occurs in hybrids Triticum × Zea L., loss of all maize chromosomes takes place during the first few embryonic divisions [52]. In octoploid hybrids of rye and wheat (triticale), all rye chromosomes remain, and the loss of chromosomes of Triticum goes on for several generations [53]. In the case of ×Trititrigia, chromosomes of Triticum are predominant (42 in the stabilized cultivar, [6]) and thus can determine genomic constitution of the hybrid. The change in the length of the IGS in the rDNA of the hybrid genome also plays a role [54,55]. Previous studies established the dominance of the A-genome in artificial and natural wheat polyploids [25]. Our result also supports AFLP data that clearly indicated predominance of the wheat genome in the genotype of ×Trititrigia cziczinii [56].

On the contrary, only a minor fraction of rDNA of ×Trititrigia cziczinii is identical to the main ribotype of Elytrigia intermedia, the other parent (Figure 5 and Figure 6). According to NGS analysis, E. intermedia has St-genome as the main in its rDNA. Most probably, it was inherited from diploid species of Pseudoroegneria; for example, European P. stipifolia. We found other minor ribotypes that do not belong to the St-genome only in E. intermedia, sample S1 (Voronezh Oblast, Russia). This sample of E. intermedia was collected from the slopes of the bank of the Khoper River in contrast to the samples collected on chalk outcrops (S2) and a steppe slope (S3). They are closer to the ribotypes of Triticum aestivum than to those of Pseudoroegneria on the phylogenetic trees (Figure 5 and Figure 6) but NCBI search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term= (accessed on 23 June 2025)) results give the greatest similarity to the sequence of tetraploid (2n = 28) Elymus nevskii. We can assume that the second major ribotype of Elytrigia intermedia is a St-genome variant from some polyploid species of Elymus and from diploid Pseudoroegneria since Elytrigia/Elymus clade is itself sister to the clade of Triticum s. l. + Secale in recent phylogenies [20]. We can interpret this finding as the trace of introgression in one of the populations of E. intermedia.

Chloroplast sequence data clearly shows that the hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii has the maternal genome of Triticum aestivum (Figure 3 and Figure 4). This may be due to the way this artificial hybrid was stabilized: it was obtained through repeated introgressive crosses with Triticum aestivum to secure beneficial traits [5,6,57]. Nevertheless, surprisingly, analysis of ETS sequences revealed the proximity of ×T. cziczinii to Elytrigia intermedia (Figure 2). This is probably caused by significant reorganization of rDNA in the genome of the artificial hybrid and, as a consequence, the formation of chimeric sequences in some regions of rDNA. Selective amplification of minor rDNA sequences due to primer specificity may also play a role. This interesting fact tells us that Elytrigia-related sequences can retain important functions in a complex genome of the hybrid. Maternal genome of Elytrigia intermedia may have different origins either from Pseudoroegneria or from Lophopyrum species [24,58]. Our data do not contradict these findings.

Speaking of the relationships between ×Trititrigia cziczinii, parental species and allied taxa, we can find many traces of hybridization in the tribe Hordeeae as well as the clades that more or less correspond to the main genera taken into our work. Species of the genus Pseudoroegneria are not very close to polyploid Elytrigia and Elymus on the ITS tree (Figure 1). Thus, rDNA of Elytrigia intermedia is probably changed compared with its putative donor, Pseudoroegneria. The group of Arctic and Siberian species of Elymus (E. hyperarcticus (Polun.) Tzvelev, E. sajanensis (Nevski) Tzvelev) forms a separate subclade on the tree (Figure 1) being a Eurasian subgroup 3 of Leo et al. [59]. This also points to the independent capture of St-genome in the genus Elymus and possible polyphyletic origin of Elymus and Elytrigia species. Elytrigia repens and E. pseudocaesia from Altai Mountains, Russia, form a distinct clade, and that most likely proves the separate origin of Elytigia repens and its affinity group. We also found a P-genome line that corresponds to the genus Agropyron. Elytrigia lolioides and Elymus tauri, surprisingly, also fell within this clade (Figure 1). Elytrigia lolioides is a tetraploid species with 2n = 28 ([60], for the Russian samples) or hexaploid, 2n = 42 [61]. P-genome sequences of E. lolioides were not found in the previous works [24]. We probably observe here more complicated and changing genome constitution in E. lolioides because other studies revealed an H-genome in this species instead of P [24]. Previous research considered Elymus tauri as a diploid with a St-genome specific to Pseudoroegneria tauri (Boiss. & Balansa) Á. Löve [24,62,63,64]. Nuclear rDNA shows the genus Psathyrostachys as the genome donor for Leymus, genome Ns (Figure 1). Chloroplast sequences trnK–rps16 show division of the genus into two groups based on the maternal genome (Figure 3). Leymus secalinus (Georgi) Tzvelev and related species—L. racemosus (Lam.) Tzvelev and L. sabulosus (M.Bieb.) Tzvelev share genome Ns. Leymus salina (M.E.Jones) Á. Löve with allied species—L. cinereus (Scribn. & Merr.) Á. Löve, L. flavescens (Scribn. & J.G.Sm.) Pilg., L. mollis (Trin.) Pilg., and L. triticoides (Buckley) Pilg. have a distant maternal genome, Xm [65]. It is interesting that rDNA of Russian samples of Leymus arenarius Hochst. can carry both Xm and Ns genomes [66].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

Samples of the artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii were taken from collection of the Federal Research Center N. I. Vavilov All-Russian Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (VIR). Samples of the parental taxa we obtained from collection of the Komarov Botanical Institute of the RAS (LE). In addition, we analyzed some marker sequences of the genera of the Hordeeae tribe from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term= (accessed on 23 June 2025)) These taxa are related to the studied species and can represent main lines of the tribe evolution. Studied samples are shown in Table 1.

4.2. DNA Extraction, Amplification, and Sanger Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from dried leaf and seed material using a Qiagen Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). Some marker regions were amplified and sequenced by the Sanger method. ITS1–5.8S rDNA–ITS2 region was amplified according to the following cycle: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 1 min, followed by 35 cycles of 98 °C for 15 s, 56 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final elongation of 72 °C for 5 min using ITS 1P [67] and ITS 4 [68] primers. Chloroplast fragment trnK–rps16 was amplified under the similar conditions using rps16–4547mod [69] and trnK5′r [70] primers but annealing temperature was 55 °C. Chloroplast gene ndhF was obtained with primers ndhF_F_mod and ndhF_R [[71], with modifications] according the same time parameters as the previous regions, and annealing temperature was 52–54 °C. Nuclear region 3′-ETS was amplified with primers ETS-2F and 18S_start_R_primer [14]. PCR protocol was with the same time parameters, and annealing temperature was 63 °C. The sequencing was performed at the Center for the collective use of scientific equipment “Cellular and molecular technologies for the study of plants and fungi” of the Komarov Botanical Institute, St. Petersburg, according to the standard protocol provided with a BigDyeTM Terminator Kit ver. 3.1 set of reagents on the ABI PRIZM 3100 sequencer (168 Third Avenue, Waltham, MA USA).

4.3. Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of the Sequences Obtained by the Sanger Method

Chromatograms were analyzed with Chromas Lite version 2.01 (Technelysium Co. South Brisbane QLD 4101, Australia) and then the sequences were aligned with the aid of the Muscle algorithm [72] included in MEGA XI [73]. The best evolutionary models for each dataset were computed with the aid of jModeltest program v. 2.1.10 [74]. We took each of the data sets separately in Mr. Bayes 3.2.2 [75]: 1–1.5 million iterations, the first 25% of trees were excluded as “burn-in”. Evolutionary models were GTR + I + G for ITS and ETS data, TVM + G for trnK–rps16, and TVM + I for ndhF sequence data. Maximum likelihood analysis was performed by IQ-TREE 2.3.6 [76], with ultrafast bootstrap option, 1000 iterations and the same evolutionary models as in Bayesian inference.

4.4. Next-Generation Sequencing

For amplification of ITS1 rDNA, the following conditions were used: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, followed by 25 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and a final elongation of 72 °C for 5 min using ITS 1P [67] and ITS 2 [68] primers. PCR products were purified using AMPureXP (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The libraries for sequencing were prepared according to the manufacturer’s MiSeq Reagent Kit Preparation Guide (Illumina) (https://www.illumina.com/products/by-type/sequencing-kits/cluster-gen-sequencing-reagents/miseq-reagent-kit-v3.html (accessed on 15 May 2025)). They were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using a MiSeq® Reagent Kit v3 (600 cycles) with paired-end reading (2 × 300) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The fragments were amplified and sequenced at the Center for Shared Use “Genomic Technologies, Proteomics, and Cell Biology” of the All-Russian Research Institute of Agricultural Microbiology.

4.5. Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of NGS Data

The obtained pool of raw sequences was trimmed by Trimmomatic [77] included in Unipro Ugene [78] as follows: PE reads; sliding window trimming with size 4 and quality threshold 12; and minimal read length 130. Then, paired sequences were combined and dereplicated and sorted by vsearch 2.7.1 [79]. The resulting sequences formed ribotypes in the whole pool of genomic rDNA; they were sorted according to their frequency. For our analysis, we established a threshold of 10 reads per pool of rDNA. The sequences were aligned using MEGA v. 11.0.13 [73]; a ribotype network was built in TCS 1.2.1 [80] by statistical parsimony method and then visualized in TCS BU [81]. In addition, we constructed a phylogenetic tree of the obtained ribotypes by Bayesian and Maximum Likelihood methods using GTR + G model. Bayesian analysis was conducted with 2–5 millions of generations by Mr. Bayes 3.2.2 [75]. ML analysis was conducted with the aid of IQ-TREE 2.3.6 [76]. In this case, we set a threshold of 30 reads per rDNA pool.

The artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii as well as its parental species are polyploids. Thus, their rDNA fraction is inherited from different parental taxa and forms different families of ribotypes. The rDNA polymorphism depicts the probable origin of the ribotypes within a sample from ancestral taxa similar to that when geographic differentiation is revealed by analyzing gene sequences of different samples of a species. In this case, we can reveal the origin of ribotypes in the sample corresponding to different subgenomes. To analyze the ribotype pattern of each sample separately, we conducted a model-based clustering method using the program Structure 2.3 [82]. The sequence files in fasta-format were converted to the Structure input files by R script for diploid organisms https://sites.google.com/site/thebantalab/tutorials#h.e9y185vac91q (accessed on 23 June 2025). We tested the rDNA pool of each sample obtained via NGS for revealing single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that can be phylogenetically significant. The genetic clusters computed by Structure more or less correspond to the ribotypes of the sample and reflect probable ancestral taxa that gave origin to the ribotypes of the studied species. Each run of Structure 2.3 [82] was carried out as follows: burn-in period of 10,000 replicates, 50,000 MCMC replicates after burn-in, 3 iterations of each burn-in computing, and K (number of hypothetic ancestral population) was set from 2 to 8. Then, we calculated the correct number of K with the aid of Evanno test [83] implemented in StructureHarvester Python Script for Python 3.13 [84]. The resulting K is a number of hypothetical ancestral ribotypes that are present in ×Trititrigia cziczinii; mostly, they represent the major ribotypes with their derivatives, but also some minor ribotypes. Results of the clustering were visualized in MS Excel 2016. We analyzed the ribotype pool of each sample separately; ribotypes within the samples are shown on the Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

5. Conclusions

Our phylogenetic study performed with different DNA markers clarified the genome structure of the artificial intergeneric hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii. The predominant genome in the hybrid genome set is that of Triticum aestivum. This is consistent with the data obtained using the AFLP method. Such a pattern most likely originated due to backcrosses between early progenies of the artificial hybrid ×Trititrigia cziczinii and the parent species Triticum aestivum. Furthermore, here we see a remarkable example of rDNA elimination in one of the genomes during highly distant hybridization acts. Our data also demonstrate geographic heterogeneity in the genomic composition of one of the parental taxa, Elytrigia intermedia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.G. and N.N.N.; methodology, A.A.G., N.N.N. and A.V.R.; software, N.N.N. and A.A.G.; validation, N.N.N., A.A.G., N.S.L. and A.V.R.; formal analysis, A.A.G., N.N.N. and V.S.S.; investigation, A.A.G., N.N.N. and A.V.R.; resources, E.V.Z. and N.S.L.; data curation, A.A.G., A.V.T. and A.V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.G., N.N.N., V.S.S. and A.V.R.; writing—review and editing, A.A.G., V.S.S., A.V.T. and A.V.R.; visualization, V.S.S., A.A.G. and N.N.N.; supervision, A.V.R. and V.S.S.; project administration, A.V.R. and V.S.S.; funding acquisition, A.A.G. and N.N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by Russian Science Foundation (project No. 25-24-00349).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to A.G. Pinaev and all researchers of the Center for Shared Use “Genomic Technologies, Proteomics and Cell Biology” of the All-Russian Research Institute of Agricultural Microbiology for next-generation sequencing, to E. E. Krapivskaya for sequencing by the Sanger method at the Center for the collective use of scientific equipment “Cellular and molecular technologies for the study of plants and fungi”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rodionova, N.A.; Soldatov, V.N.; Merezhko, V.E.; Yarosh, N.P.; Kobylyansky, V.D. Oat. In Cultivated Flora of the USSR; Soldatov, V.N., Kobylyansky, V.D., Eds.; Kolos: Moscow, Russia, 1994; p. 367. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- van de Wouw, M.; Kik, C.; van Hintum, T.; van Treuren, R.; Visse, B. Genetic erosion in crops: Concept, research results and challenges. Plant Gen. Res. 2009, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, C.K.; Brush, S.; Costich, D.E.; Curry, H.A.; de Haan, S.; Engels, J.M.M.; Guarino, L.; Hoban, S.; Mercer, K.L.; Miller, A.J.; et al. Crop genetic erosion: Understanding and responding to loss of crop diversity. New Phytol. 2021, 233, 84–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilov, N.I. The importance of interspecific and intergeneric hybridization in selection and evolution. Proc. AS USSR Ser. Biol. 1938, 3, 543–563. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Loshakova, P.O.; Pogost, A.A.; Vainshenker, T.S.; Ivanova, L.P. Distant hybrids of ×Trititrigia with Elytrigia intermedia and Elymus farctus. Int. Res. J. 2022, 11, 9. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachuga, Y.; Meskhi, B.; Pakhomov, V.; Semenikhina, Y.; Kambulov, S.; Rudoy, D.; Maltseva, T. Experience in the Cultivation of a New Perennial Cereal Crop—Trititrigia in the Conditions of South of the Rostov Region. Agriculture 2023, 13, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevorkyan, M.M.; Babosha, A.V.; Loshakova, P.O.; Pogost, A.A.; Komarova, G.I.; Wineshenker, T.S.; Upelniek, V.P. The leaf surface micromorphology of plants obtained from crosses between Elymus farctus and the stable form × Trititrigia cziczinii × wheat cultivar ‘Botanicheskaya 3’. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72, 3543–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, P.M.; Graham, S.W.; Little, D.P. Choosing and using a plant DNA barcode. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Ge, X.-J.; Zhou, S.-L.; Gao, L.-M.; Fu, C.-X.; Chen, S.-L. Plant DNA barcoding in China. J. Syst. Evol. 2011, 49, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, B.G.; Sanderson, M.J.; Porter, J.M.; Wojciechowski, M.F.; Campbell, C.S.; Donoghue, M.J. The ITS Region of Nuclear Ribosomal DNA: A Valuable Source of Evidence on Angiosperm Phylogeny. Ann. Mis. Bot. Gard. 1995, 82, 247–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrer, J.; Krak, K.; Chrtek, J. Intra-individual polymorphism in diploid and apomictic polyploid hawkweeds (Hieracium, Lactuceae, Asteraceae): Disentangling phylogenetic signal, reticulation, and noise. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochorová, J.; Garcia, S.; Gálvez, F.; Symonová, R.; Kovařík, A. Evolutionary trends in animal ribosomal DNA loci: Introduction to a new online database. Chromosoma 2018, 127, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.D.P.N.; Riina, R.; Valduga, E.; Caruzo, M.B.R. A new species of Croton (Euphorbiaceae) endemic to the Brazilian Pampa and its phylogenetic affinities. Plant Syst. Evol. 2022, 308, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelchenko, D.O.; Krinitsina, A.A.; Kasianov, A.S.; Speranskaya, A.S.; Chesnokova, O.V.; Polevova, S.V.; Severova, E.E. Assessment of ITS1, ITS2, 5’-ETS, and trnL-F DNA Barcodes for Metabarcoding of Poaceae Pollen. Diversity 2022, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, T. Utility of low-copy nuclear gene sequences in plant phylogenetics. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 37, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, N.; Brassac, J.; Kilian, B.; Blattner, F.R. Dated tribe-wide whole chloroplast genome phylogeny indicates recurrent hybridizations within Triticeae. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löve, Á. Conspectus of the Triticeae. Feddes Repert. 1984, 95, 425–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, D.R. The genomic system of classification as a guide to intergeneric hybridization with the perennial Triticeae. In Gene Manipulation in Plant Improvement; Gustafson, J.P., Ed.; Plenum Publishing Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 209–280. [Google Scholar]

- Mason-Gamer, R.J. Phylogeny of a genomically diverse group of Elymus (Poaceae) allopolyploids reveals multiple levels of reticulation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason-Gamer, R.J.; White, D.M. The phylogeny of the Triticeae: Resolution and phylogenetic conflict based on genomewide nuclear loci. Am. J. Bot. 2024, 111, e16404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassac, J.; Blattner, F.R. Species-Level Phylogeny and Polyploid Relationships in Hordeum (Poaceae) Inferred by Next-Generation Sequencing and In Silico Cloning of Multiple Nuclear Loci. Syst. Biol. 2015, 64, 792–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.; Forest, F.; Barraclough, T.; Rosindell, J.; Bellot, S.; Cowan, R.; Golos, M.; Jebb, M.; Cheek, M. A phylogenomic analysis of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae). Mol. Phyl. Evol. 2020, 144, 106668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyama, Y.; Hirota, S.K.; Matsuo, A.; Tsunamoto, Y.; Mitsuyuki, C.; Shimura, A.; Okano, K. Complementary combination of multiplex high-throughput DNA sequencing for molecular phylogeny. Ecol. Res. 2022, 37, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fan, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.-Q.; Sha, L.-N.; Wang, Y.; Kang, H.-Y.; Zeng, J.; Yu, X.-F.; Zhou, Y.-H. Phylogeny and maternal donors of Elytrigia Desv. sensu lato (Triticeae; Poaceae) inferred from nuclear internal-transcribed spacer and trnL-F sequences. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Fa, C.; Yi, C.; Shi, Q.; Su, H.; Liu, C.; Yuan, J.; Liu, D.; et al. New insights on the evolution of nucleolar dominance in newly resynthesized hexaploid wheat Triticum zhukovskyi. Plant J. 2023, 115, 1298–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Peer, Y.; Mizrachi, E.; Marchal1, K. The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nature Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.-Q.; Lian, L.; Wang, W. The Molecular Phylogeny of Land Plants: Progress and Future Prospects. Diversity 2022, 14, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Xu, S.; Nevo, E.; Zeng, F.; Deng, F.; Catalán, P.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.-H. Genomic and evolutionary evidence for drought adaptation of allopolyploid Brachypodium hybridum. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 2924–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanar, A.; Castroviejo, S.; Catalán, P. Phylogeny of the tribe Aveneae (Pooideae, Poaceae) inferred from plastid trnT-F and nuclear ITS sequences. Am. J. Bot. 2007, 94, 1554–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarela, J.M.; Bull, R.D.; Paradis, M.J.; Ebata, S.N.; Peterson, P.M.; Soreng, R.J.; Paszko, B. Molecular phylogenetics of cool-season grasses in the subtribes Agrostidinae, Anthoxanthinae, Aveninae, Brizinae, Calothecinae, Koeleriinae and Phalaridinae (Poaceae, Pooideae, Poeae, Poeae chloroplast group 1). PhytoKeys 2017, 87, 1–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberá, P.; Soreng, R.J.; Peterson, P.M.; Romaschenko, K.; Quintanar, A.; Aedo, C. Molecular phylogenetic analysis resolves Trisetum (Poaceae: Pooideae: Koeleriinae) polyphyletic: Evidence for a new genus, Sibirotrisetum and resurrection of Acrospelion. J. Syst. Evol. 2020, 58, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkach, N.; Schneider, J.; Döring, E.; Wölk, A.; Hochbach, A.; Nissen, J.; Winterfeld, G.; Meyer, S.; Gabriel, J.; Hoffmann, M.H.; et al. Phylogenetic lineages and the role of hybridization as driving force of evolution in grass supertribe Poodae. Taxon 2020, 69, 234–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soreng, R.J.; Peterson, P.M.; Zuloaga, F.O.; Romaschenko, K.; Clark, L.G.; Teisher, J.K.; Gillespie, L.J.; Barberá, P.; Welker, C.A.D.; Kellogg, E.A.; et al. A worldwide phylogenetic classification of the Poaceae (Gramineae) III: An update. J. Syst. Evol. 2022, 60, 476–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, H. Genome analyses bei Triticum and Aegilops. Cytologia 1930, 1, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, H. Discovery of DD analyser, one of the ancestors of T. vulgare. Agric. Hort. 1944, 19, 889–890. [Google Scholar]

- Kihara, H. Maturation division in F1 hybrids between Triticum dicoccoides × Aegilops squarrosa. Kromosomo 1946, 1, 6–11, (In Japanese with English summary). [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, N. Studies in the cytology of cereals. J. Genet. 1940, 39, 437–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, B.S.; Kimber, G. Giemsa C-banding and the evolution of wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 4086–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, B.L.; Lookhart, G.L.; Mak, A.; Cooper, D.B. Sequences of purothionins and their inheritance in diploid, tetraploid, and hexaploid wheats. J. Hered. 1982, 73, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Yi, S.; Yong-Hong, D. Internal Transcribed Spacer Region of rDNA in Common Wheat and Its Genome Origins. Acta Agron. Sin. 2009, 35, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loginova, D.B.; Silkova, O.G. The Genome of Bread Wheat Triticum aestivum L.: Unique Structural and Functional Properties. Rus. J. Genet. 2018, 54, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.; Yang, J. Biosystematics of Triticeae: Volume I. Triticum-Aegilops Complex; Agriculture Press of China: Beijing, China, 2013; 265p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.; Yang, J. Biosystematics of Triticeae: Volume V. Genera: Campeiostachys, Elymus, Pascopyrum, Lophopyrum, Trichopyrum, Hordelymus, Festucopsis, Peridictyon, and Psammopyrum; Agriculture Press of China: Beijing, China, 2013; 516p. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.H. The circumscription and genomic evolution of Elytrigia Sensu Lato (Poaceae: Triticeae). In Proceedings of the 4th Wheat Genomics and Molecular Breeding China; Nanjing Agricultural University: Nanjing, China, 2013; pp. 105–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cauderon, Y.; Saigne, B. New interspecific and intergeneric hybrids involving Agropyron. Wheat Inffoem Serv. 1961, 12, 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Dvořák, J. Chromosome differentiation in polyploidy species of Elytrigia, with special reference to the evolution of diploid-like chromosome pairing in polyploidy species. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 1981, 23, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.W.; Wang, R.R.C. Genome analysis of Elytrigia caespitosa, Lophopyrum nodosum, Pseudoroegneria eniculata ssp. scythica, and Thinopyrum intermedium (Triticeae: Gramineae). Genome 1993, 36, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.R.C.; von Bothmer, R.; Dvořák, J.; Fedak, G.; Linde-Laursen, I.; Muramatsu, M. Genome symbols in the Triticeae (Poaceae). In Proceedings of the 2nd International Triticeae Symposium, Logan, UT, USA, 20–24 June 1994; Wang, R.R.C., Jensen, K.B., Jaussi, C., Eds.; Utah State University: Logan, UT, USA, 1994; pp. 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vershinin, A.; Svitashev, S.; Gummesson, P.O.; von Salomon, B.; von Bothmer, R.; Bryngelsson, T. Characterization of a family of tandemly repeated DNA sequences in Triticeae. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1994, 89, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assadi, M.; Runemark, H. Hybridization, genomic constitution, and generic delimitation in Elymus s. l. (Poaceae: Triticeae). Plant Syst. Evol. 1995, 194, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, A.V. Changes in Genomes and Karyotypes during Speciation and Progressive Evolution of Plants. Rus. J. Gen. 2025, 61, 464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurie, D.A.; Bennett, M.D. The timing of chromosome elimination in hexaploid wheat × maize crosses. Genome 1989, 32, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtushenko, E.V.; Lipikhina, Y.A.; Stepochkin, P.I.; Vershinin, A.V. Cytogenetic and molecular characteristics of rye genome in octoploid Triticale (×Triticosecale Wittmack). Comp. Cytogenet. 2019, 13, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.J.; Pikaard, C.S. Transcriptional analysis of nucleolar dominance in polyploid plants: Biased expression/silencing of progenitor rRNA genes is developmentally regulated in Brassica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 3442–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.J.; Comai, L.; Pikaard, C.S. Gene dosage and stochastic effects determine the severity and direction of uniparental ribosomal RNA gene silencing (nucleolar dominance) in Arabidopsis allopolyploids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 14891–14896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonova, A.A.; Boris, K.V.; Dedova, L.V.; Melnik, V.A.; Ivanova, L.P.; Kuzmina, N.P.; Zavgorodniy, S.V.; Upelniek, V.P. Genome polymorphism of the synthetic species ×Trititrigia cziczinii Tsvel. inferred from AFLP analysis. Vavilov J. Gen. Sel. 2018, 22, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, L.P.; Shchuklina, O.A.; Voronchikhina, I.N.; Voronchikhin, V.V.; Zavgorodny, S.V.; Enzekrey, E.S.; Komkova, A.D.; Upelniek, V.P. Prospects for use the new trititrigia crop (×Trititrigia cziczinii Tzvel.) in feed production. Lump Prod. 2020, 10, 1316. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Fan, X.; Sha, L.N.; Kang, H.Y.; Zhang, H.Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.L.; Yang, R.W.; Zhou, Y.H. Nucleotide polymorphism pattern and multiple maternal origin in Thinopyrum intermedium inferred by trnH-psbA sequences. Biol. Plant. 2012, 56, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, J.; Bengtsson, T.; Morales, A.; Carlsson, A.S.; von Bothmer, R. Genetic structure analyses reveal multiple origins of Elymus sensu stricto (Poaceae). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasskaya, N.A.; Plaksina, T.I. Chromosome numbers of certain vascular plants in Zhiguli State Reserve. Bot. Zhurn. 1995, 80, 100–101. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sha, L.; Fan, X.; Kang, H.; Zhang, H.; Sun, G.; Zhang, L.; et al. Genome constitution and evolution of Elytrigia lolioides inferred from Acc1, EF-G, ITS, TrnL-F sequences and GISH. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.Q.; Fan, X.; Zhang, C.; Ding, C.B.; Wang, X.L.; Zhou, Y.H. Phylogenetic relationships of species in Pseudoroegneria (Poaceae: Triticeae) and related genera inferred from nuclear rDNA ITS (internal transcribed spacer) sequences. Biologia 2008, 634, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Chen, W.J.; Yan, H.; Wang, Y.; Kang, H.Y.; Zhang, H.Q.; Zhou, Y.H.; Sun, G.L.; Sha, L.N.; Fan, X. Evolutionary patterns of plastome uncover diploid-polyploid maternal relationships in Triticeae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020, 149, 106838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroupin, P.Y.; Yurkina, A.I.; Kocheshkova, A.A.; Ulyanov, D.S.; Karlov, G.I.; Divashuk, M.G. Comparative assessment of the copy number of satellite repeats in the genome of Triticeae species. Vavilov J. Gen. Sel. 2023, 27, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culumber, C.M.; Larson, S.R.; Jensen, K.B.; Jones, T.A. Genetic structure of Eurasian and North American Leymus (Triticeae) wildryes assessed by chloroplast DNA sequences and AFLP profiles. Plant Syst. Evol. 2011, 294, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punina, E.O.; Gnutikov, A.A.; Nosov, N.N.; Shneyer, V.S.; Rodionov, A.V. Hybrid Origin of ×Leymotrigia bergrothii (Poaceae) as Revealed by Analysis of the Internal Transcribed Spacer ITS1 and trnL Sequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgway, K.P.; Duck, J.M.; Young, J.P.W. Identification of roots from grass swards using PCR-RFLP and FFLP of the plastid trnL (UAA) intron. BMC Ecol. 2003, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A., Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, W.J.; Wurdack, K.J.; Zimmer, E.A.; Weigt, L.A.; Janzen, D.H. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 8369–8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.A.; Soltis, D.E. Phylogenetic inference in Saxifragaceae sensu stricto and Gilia (Polemoniaceae) using matK sequences. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 1995, 82, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, R.G.; Sweere, J.A. Combining Data in Phylogenetic Systematics: An Empirical Approach Using Three Molecular Data Sets in the Solanaceae. Syst. Biol. 1994, 43, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M. Unipro UGENE: A unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahe, F. VSEARCH: A versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, M.; Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. TCS: A computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 1657–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Múrias dos Santos, A.; Cabezas, M.P.; Tavares, A.I.; Xavier, R.; Branco, M. tcsBU: A tool to extend TCS network layout and visualization. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 627–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 2000, 155, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, D.A.; von Holdt, B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Res. 2012, 4, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.