Abstract

Minthostachys verticillata (Griseb.) Epling, commonly known as peperina, is an aromatic species endemic to Argentina and traditionally used for gastrointestinal ailments. Despite its extensive folkloric use and inclusion in the Argentine Pharmacopoeia, its aqueous extract (the most commonly consumed preparation) has been described in terms of major phytochemical groups, and, currently, no studies have investigated its effects on key intestinal epithelial mechanisms. This plant is also employed in the production of beverages and herbal blends, and its massive consumption highlights the importance of its scientific study. Here, the aqueous extract of M. verticillata was characterized by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, leading to the identification of fourteen polyphenolic compounds. In intestinal cell models, the extract displayed high IC50 values, supporting its safety, and exhibited concentration-dependent bioactivity. In HT-29 cells, it modulated NF-κB activation induced by TNF-α and reduced LPS-stimulated IL-8 production. Pretreatment of Caco-2 monolayers prevented the decrease in transepithelial electrical resistance, increased FITC–dextran permeability, and nitric oxide production triggered by an inflammatory cocktail. Additionally, the extract inhibited HT-29 cell migration. These results demonstrate that M. verticillata aqueous extract exerts anti-inflammatory, barrier-protective, and anti-migratory effects in vitro, providing novel insights into how its polyphenolic composition may underlie these biological activities, supporting its traditional use and potential applications in intestinal health.

1. Introduction

The intestinal barrier prevents the entry of pathogenic microorganisms and toxic luminal substances while regulating, at the same time, the absorption of nutrients, electrolytes, and water from the lumen into circulation. Barrier functions are maintained by a complex multilayer system, which includes an external physical barrier and an inner functional immunological component [1,2]. Intestinal chronic inflammatory disorders, such as inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), impair barrier function, which results in elevated intestinal permeability and increased passage of harmful substances from the lumen [3]. Strong evidence suggests the involvement of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in the pathogenesis of IBD, a transcription factor which regulates numerous genes that participate in immunological and inflammatory response pathways. Alterations in NF-κB activation have been consistently reported in inflamed colonic tissue of patients with IBD, and several genetic factors contribute to this dysregulation. Variants that enhance NF-κB signaling include alterations in NF-κB target genes, such as those encoding interleukins (IL) 12 and 23 [4]. Additionally, mutations in NF-κB–stimulating immune receptors, such as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2), are strongly associated with Crohn’s disease, leading to impaired microbial recognition and contributing indirectly to the chronic inflammatory cycle [5]. In addition, IBD has been linked to an increased production of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) which in turn could be associated with changes in relative abundance or diversity in gut microbiota (dysbiosis). LPS are bacterial surface glycolipids, produced by Gram-negative bacteria, and have been identified as a promoter of diverse inflammatory pathways implicated in the development of IBD. Their potent inflammatory response is mediated mainly by their interaction with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4), determining cytokine cascades (through NF-κB and mTOR/STAT3 pathways) and caspase activation (through NLRP3 inflammasome) in a way that contributes to altered gut permeability, leading to a self-sustaining cycle of inflammation [6].

IBD patients are at a higher risk of developing gastrointestinal cancers due to chronic inflammation and immunosuppressive treatments. Given that the inflammatory environment in IBD resembles that of cancer, with both conditions sharing key mediators such as cytokines and pathways linked to inflammation and oxidative stress, effective control of these processes is essential to reduce the risk of cancer development. Hence, primary prevention strategies often involve inflammation control, achieved with drugs like 5-aminosalicylic acid (mesalazine). In this context, prevention is critical since the coexistence of IBD and cancer makes their treatments even more challenging [7,8].

Due to the chronic nature of these intestinal diseases, inconsistent treatment outcomes of current pharmacological treatments, and related serious side effects, there is a need to seek alternative treatment options [9] and study their molecular mechanism of action.

Among natural options, plant aqueous extracts such as infusions and decoctions, are widely consumed. They are rich in ubiquitous secondary metabolites, like polyphenols, and their intake has been associated with plenty of health benefits [10]. Polyphenols have been proposed as potential intestinal permeability modulators, although the mechanisms involved are not yet fully elucidated. Their activity seems to be attributed to multiple mechanisms, which may also depend upon the type and amount of compounds considered. The results from in vitro studies have shown the capacity of polyphenols to increase the expression and/or production of numerous tight junction proteins and to reduce the release of several interleukins/cytokines [11].

Minthostachys verticillata (Griseb.) Epling (Mv) is a medicinal plant belonging to the mint family (Lamiaceae) and is the only species that grows in Argentina. It is commonly known as ‘peperina’; its aroma is similar to mint and it is used mainly in infusion as a digestive, sedative, spasmolytic, antidiarrheic, and antiemetic and also to reduce colics and flatulence. Furthermore, this plant finds application in the food industry for the production of liqueurs, refreshing beverages, and herbal blends (comprising Ilex paraguariensis mixed with local herbs, used to prepare ‘mate’, the traditional Argentine infusion). It is also commercially available for medicinal and aromatic purposes across various regions of the country [12,13]. Therefore, the massive consumption of its aqueous extract makes its characterization and study important. In addition, it is worth emphasizing that this particular species has been officially recognized and included in the National Argentine Pharmacopoeia [14].

Despite the extensive traditional use of Mv as an aqueous infusion, current scientific evidence is largely restricted to studies on the essential oil [15,16,17,18]. Notably, the composition of the aqueous extract has been described in terms of major phytochemical groups. While Bravi et al. (2025) [19] studied silver nanoparticles synthesized with the aqueous extract as a surface disinfectant, reporting flavonoids and tannins acting as particle reducers and stabilizers, this work was oriented toward technological rather than pharmacological applications. Thus, a more exhaustive phytochemical profile is still needed to support mechanistic studies and advance research on its therapeutic potential. The aqueous extract has been evaluated in animal models closely related to IBD and IBS, describing its overall anti-inflammatory outcomes. These include reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and in inducible enzymes such as COX-2 and iNOS [20]. However, the specific epithelial pathways and molecular targets underlying these effects, including those related to intestinal permeability, remain unknown. This gap underscores the need for mechanistic, cell-based studies focused specifically on the aqueous extract, which is the form traditionally consumed by the population.

Hence, the aim of the present work was to characterize the phytochemical composition of the Mv aqueous extract and to investigate its effects on key intestinal epithelial mechanisms, including inflammatory signaling, barrier function, and cell migration, using in vitro intestinal models.

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Profile

The assignment of the main components in the Mv extract is presented for the first time in Table 1.

Table 1.

Phytochemical analysis of Minthostachys verticillata aqueous extract.

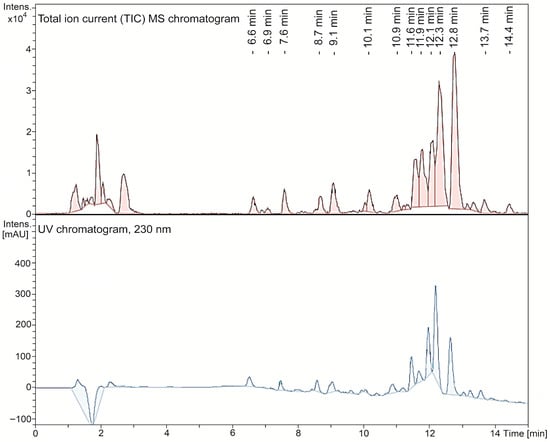

Polyphenols predominate in the aqueous extract. A typical HPLC chromatogram of the aqueous Mv extract, obtained with the mass spectrometry detector (total ionic current) and with the ultraviolet detector at 230 nm, is shown in Figure 1. Compounds such as salvianolic acid D, rosmarinic acid, 3-caffeoylquinic acid (chlorogenic acid), 4-caffeoylquinic acid, methyl caffeate dimer, yunnaneic acid F, salvianolic acid B/E isomer 2, isomelitric acid A (caffeoylrosmarinic acid), sagerinic acid, salvianolic acid B, salvianolic acid A and rabdosiin can be considered as caffeic acid derivatives, mostly oligomers. Flavonoids such as rutin and quercetine-3-O-glucoside were additionally found in the extract. Most of these compounds are reported in other species of the genus Minthostachys [23] or other members of the Lamiaceae family (Lamiales order), but in none of them in the same combination [21,22,24,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37]. It is important to note that the composition of this aqueous extract was completely different from that of the essential oil of the same species, described in the literature, where the presence of monoterpenes (or monoterpenoids) has been reported, including pulegone (63.4%), menthone (15.9%), and limonene (2.1%), together with other minor components such as α-pinene (0.18%), β-pinene (0.3%), and 1,8-cineole (0.1%), in a gas chromatography analysis [15]. These differences are expected, due to the methods of production, by decoction in this case, and by hydrodistillation in the case of the essential oil.

Figure 1.

Total ion current mass spectrometry chromatogram and ultraviolet chromatogram at 230 nm of the aqueous Minthostachys verticillata extract.

2.2. Cytotoxicity

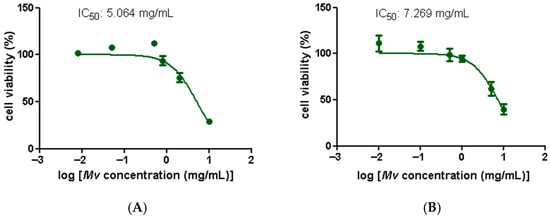

Figure 2 displays Mv extract cytotoxicity curves for human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines HT29 (A) and Caco-2 (B). Mv reduced the number of viable cells in a dose-dependent manner and IC50 values were similar in both cell lines. Since high IC50 values indicate low cytotoxicity, these results suggest a favorable safety profile for the aqueous extract, which is consistent with its traditional oral use.

Figure 2.

Effect of M. verticillata aqueous extract on the cell viability of the intestinal cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2 determined by the MTT assay. (A) Cytotoxicity curve in the HT-29 cell line. (B) Cytotoxicity curve in the Caco-2 cell line. Dose-response curves with IC50 values are shown. Data represent the mean ± SEM of independent experiments. Small error bars are not visible.

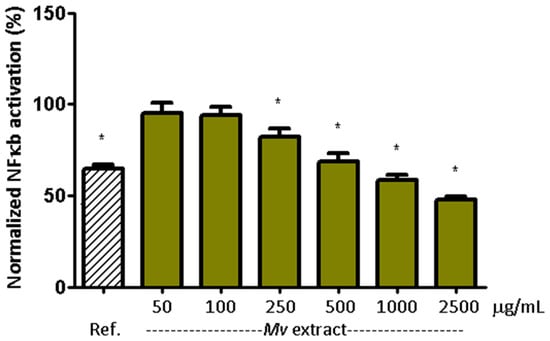

2.3. NF-κB Pathway Modulation

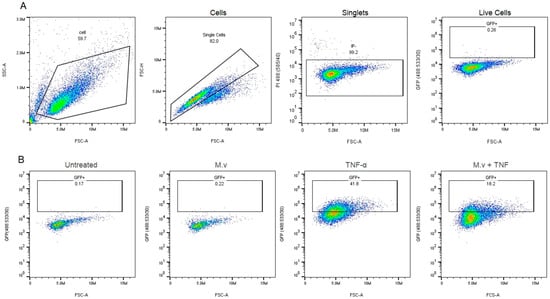

Figure 3 shows the effect of the Mv extract on NF-κB activation in HT-29 reporter cells. The increase in NF-κB signaling induced by TNF-α (10 ng/mL) was reduced by the reference inhibitor (BAY 11-7082, 10 µM) [38] and by Mv pretreatment in a concentration dependent manner. Values were normalized to the positive (TNF-α) and negative (unstimulated) controls. Representative flow cytometry images for NF-κB modulation assays are shown in Appendix A (Figure A1).

Figure 3.

Modulation of TNF-α-induced NF-κB signaling in HT-29-NF-κB-hrGFP. Cells were treated with different concentrations of Mv extract for 3 h and 1 ng/mL of TNF-α for 24 h. NF-κB activation and cell viability were evaluated by flow cytometry. As a response control, BAY 11-7082 (10 μM) was used. In all cases, cell viability was over 90%. For each treatment group, deviation from the theoretical value (100%) was evaluated using a one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test. * p < 0.05 compared with 100% as the theoretical value. Ref. corresponds to BAY 11-7082 [38].

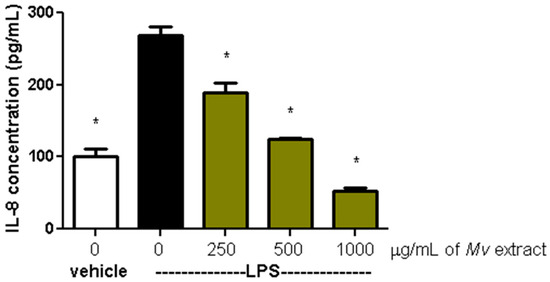

2.4. IL-8 Production

The production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-8 in HT-29 cells, induced by LPS (100 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of Mv extract, is shown in Figure 4. In comparison to cells treated only with LPS, a concentration-dependent reduction in IL-8 release was observed when exposed to the aqueous extract.

Figure 4.

Effect of Mv aqueous extract on the production of IL-8 in HT-29 cells induced by LPS. One-way ANOVA analysis (Dunnett’s post-test) compared with LPS control, * p < 0.05.

Taken together, the findings presented in Section 2.3 and Section 2.4 suggest that Mv attenuates the inflammatory response induced by TNF-α and LPS.

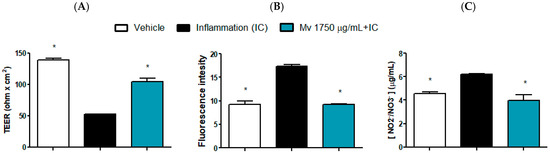

2.5. Intestinal Barrier Functionality

Barrier-related endpoints were evaluated using a single, non-cytotoxic concentration of the extract. This concentration was selected to ensure sub-toxic exposure [39] and to enable the integrated assessment of multiple parameters of epithelial function under biologically relevant conditions, rather than focusing on concentration–response characterization for individual markers [40]. Caco-2 and HT-29 models exhibit analogous inflammatory signaling responses [41], supporting the use of either line to investigate barrier and inflammatory endpoints in vitro. Hence, modulatory concentrations observed in HT-29 cells serves as a valid reference to select the concentration for studies in Caco-2 cells. The results in Caco-2 cells on transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER), the passage of FITC-dextran and nitrite/nitrate production in inflammatory condition is shown in Figure 5A–C respectively, where the effect of the Mv extract on these parameters can be observed. The inflammatory cocktail (IC) reduced almost 3-fold the normal TEER, nearly duplicated the passage of FITC-dextran and augmented around 50% the production of nitrite/nitrate. These alterations were prevented by pretreatment with Mv extract indicating its ability to enhance epithelial barrier functionality, prevent an increase in permeability and display an anti-inflammatory response. The Mv extract alone did not show any significant differences from the control group in any of these assays.

Figure 5.

Mv effect on intestinal epithelial barrier functionality. TEER (A), FITC-D paracellular permeability (B) and NO production (C). Caco-2 cells were seeded in transwell plates, polarized and challenged with an inflammatory cocktail (IC: TNF-α + IL-1β + IFN-ɣ) with or without a 3 h pretreatment with Mv. After 24 h, barrier functionality was assessed. Results are expressed as the Mean ± SEM values. One-way ANOVA analysis (Dunnett’s post-test) compared with the IC group, * p < 0.05.

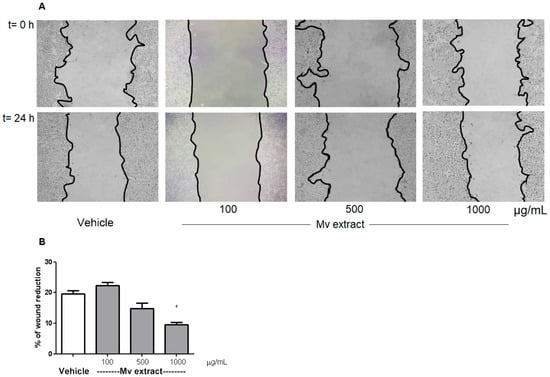

2.6. In Vitro Cell Migration

Figure 6 illustrates the scratch assay results conducted on HT-29 cells. Cell migration was hindered at the highest concentrations of Mv, as evidenced by reduced wound area closure when compared to the control cells after a 24-h treatment period.

Figure 6.

Scratch assay in HT-29 cell line. (A) Representative images of wound areas at 0 and 24 h after wounding, following treatment with different concentrations of Mv aqueous extract or with fresh medium (vehicle control). (B) Quantification of wound closure. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-test compared with vehicle group; * p < 0.05.

3. Discussion

In recent years, interest in medicinal plants for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders has increased, not only as sources of new bioactive chemical entities but also as multitarget interventions for complex diseases. In this context, this study provides mechanistic insights that have not been previously described for the biological activity of the traditional Mv aqueous extract, which differs in chemical profile and bioactivity from the essential oil that has dominated previous research. Although in vivo studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity of the aqueous extract [20], inhibition of the NF-κB pathway and protection of gut barrier function are identified in this work as key epithelial mechanisms underlying its effects. By characterizing the phytochemical composition of the aqueous extract and linking it to epithelial responses, this work addresses a significant gap in the literature and highlights the biological relevance of the traditionally consumed preparation. The observed effects are relevant considering the central role of these processes in intestinal homeostasis and in the pathogenesis of the increasingly prevalent chronic inflammatory bowel disorders.

The extract reduced NF-κB activation induced by TNF-α and IL-8 secretion induced by LPS. LPS and TNF-α both activate inflammatory signaling, but through distinct upstream receptors and partially overlapping downstream cascades. LPS binds to TLR4 on the epithelial cell surface, triggering signals that lead to the activation of several transcription factors, including NF-κB. This results in the production of multiple pro-inflammatory mediators, such as IL-8, amplifying mucosal inflammation. On the other hand, TNF-α acts through its receptor TNFR, recruiting adaptor proteins which also converge on the activation of the Inhibitor of κB Kinase (IKK) complex and the subsequent nuclear translocation of NF-κB [4]. In intestinal pathophysiology, although the etiology varies, NF-κB signaling represents a convergent point that contributes to chronic inflammation, epithelial barrier disruption, and increased permeability [4,42], supporting the relevance of targeting this pathway. Taking into account both stimuli-induced signaling events, the extract may limit inflammatory amplification and maintain barrier homeostasis. Besides, the ability of the extract to attenuate LPS-responsive pathways is particularly relevant, given their central role in driving mucosal inflammation and barrier disruption in IBD.

On the other hand, the extract also influenced cellular functions related to inflammation-driven processes. Anti-inflammatory responses can affect cell migration by altering the extracellular environment and the signals that cells receive [43], as observed in the scratch assay in HT-29 cells, where the Mv aqueous extract prevented migration, a crucial factor in the context of cancer. Since chronic intestinal inflammation is a recognized driver of epithelial transformation and colorectal cancer development [7,8], the ability of the Mv aqueous extract to attenuate inflammatory pathways together with limiting migration supports its potential role as a modulator of inflammation-associated tumorigenic mechanisms. Given that cell viability remained above 90% at all tested concentrations, the reduction in wound closure induced by Mv could be attributed to modulation of signaling pathways involved in cell migration (e.g., cytoskeleton dynamics, adhesion molecules), rather than cytotoxicity. Several polyphenols present in the Mv aqueous extract have reported anti-migratory and anti-invasive potential in diverse tumour cell lines by modulating multiple cellular pathways. Hence, these mechanisms may underlie the reduced wound closure observed in this work. Salvianolic acid B inhibits EMT and stabilizes the cytoskeleton by binding β-actin [44], and also suppresses migration and invasion via the RECK/STAT3 axis [45]. Salvianolic acid A reduces MMP-2 and EMT markers via Raf/MEK/ERK signaling [46]. Rutin attenuated ROS generation and modulating redox-sensitive signaling pathways that govern cytoskeletal remodeling and cell–matrix adhesion [47], and by suppressing MMP-2 and key pathways such as STAT3, Wnt, and PI3K/Akt [48,49]. Rosmarinic acid regulates key migratory pathways, targeting the ADAM-17/EGFR/Akt/GSK-3β axis, likely decreasing MMP-2/MMP-9 expression [50] and activating AMPK [51]. Chlorogenic acids isomers (3- and 4-caffeoylquinic acids) modulates VEGFR2, ERK1/2, and Akt signaling, binds annexin A2, inhibits MMP expression and pro-migratory PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, ultimately reducing oxidative stress and extracellular matrix remodeling [52]. Quercetin-3-O-glucoside reduces motility by blocking EGFR signaling [53]. Overall, these findings suggest that the extract’s impact on cell migration likely reflects the combined action of multiple constituents, acting on complementary pathways.

The results in Caco-2 monolayers further reinforce the promising ability of the extract to influence the inflammatory response and intestinal barrier function. Pretreatment with the extract prevented the inflammatory cocktail–induced decrease in TEER and increase in FITC–dextran flux across the monolayers, indicating a potential protective effect on barrier function and suggesting that the extract may strengthen epithelial cohesion and limit permeability increases. Additionally, Caco-2 cells pre-treated with the extract exhibited a decrease in nitrite/nitrate release in the supernatant indicating an anti-inflammatory response. Together, these results suggest that the aqueous extract enhances epithelial cohesion and limits inflammation-induced permeability, two processes highly relevant to the pathophysiology of IBD and IBS.

Although the aqueous extract of M. verticillata is the form most widely consumed and traditionally used, its chemical composition has been far less explored than that of the essential oil. This study highlights that the aqueous extract differs markedly from the essential oil [16] and reveals a promising polyphenolic profile with potential relevance for gastrointestinal disorders. In this context, plant extracts from Lamiaceae and other families that share caffeic acid derivatives and flavonoid polyphenols with Mv have shown anti-inflammatory effects, improvements in intestinal barrier function and NF-κB inhibition [32,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Other studies have evaluated pure compounds that are also present in Mv. In this regard, caffeic acid targets COX-2 and its product prostaglandin E2, as well as the biosynthesis of IL-8 and IL-1β, and it inhibits the formation of advanced glycation end products, exhibiting antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in cellular and in vivo contexts [60,61]. Salvianolic acid B shows anti-inflammatory effects and NF-κB regulation [62,63,64]. The main targets of the flavonoid rutin, a prebiotic agent, include inhibition of cyclooxygenase, NF-κB, and Nrf-2 pathways, attenuating oxidative stress and improving barrier function and immunity [65,66,67,68,69]. Therefore, although these data could support the plausibility of the effects observed in the present work, the biological activity of the extract is likely to result from the integrated and potentially synergistic action of its complex mixture of constituents rather than from a single isolated compound, underscoring the importance of studying whole extracts.

Overall, the ability of Mv aqueous extract to modulate the NF-κB–related inflammatory signaling, improve intestinal barrier function, and limit migration is highly relevant, as these interconnected epithelial mechanisms play central roles in the pathophysiology of chronic intestinal disorders, where epithelial dysfunction is a key perpetuating factor. This modulatory capacity provides a mechanistic framework that is consistent with its traditional digestive use and, along with the previously reported in vivo effects [20], supports the therapeutic potential of this widely consumed preparation. It further highlights the relevance of its polyphenolic composition in mediating its biological activity on the digestive system and reinforces the importance of exploring whole extracts as complementary strategies. Thus, these results position the extract as a promising candidate for future translational investigations in inflammation and barrier-related intestinal disorders.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Drugs and Materials

Culture media, fetal bovine serum (FBS), and cell culture reagents were provided from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA), GE Healthcare (Chicago, IL, USA), and Greiner (Kremsmünster, Austria). Plasticware was obtained from Corning Inc. (Corning, NY, USA). IL-1β was purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), Griess reagent and TNF-α were obtained from Sigma (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Unless otherwise indicated, all other chemical reagents employed were of the highest available grade and acquired from Sigma.

4.2. Plant Material and Extract Preparation

The aerial parts (leaves, stems and flowers/fruits) of Minthostachys verticillata (Griseb.) Epling, ‘peperina’, were collected in Instituto de Recursos Biológicos, Plantas Medicinales y Aromáticas, Hurlingham, Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina and identified by agronomist Hernan Bach. A voucher specimen (H. G. Bach. 738) was stored in Herbario de Farmacobotánica (BAF), Facultad de Farmacia y Bioquímica, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. The plant material was grounded into a fine powder and a decoction was prepared following the corresponding Farmacopea Argentina 7th ed. monograph [70]. The extract was concentrated, lyophilized and stored at 4 °C (Yield: 38%).

To perform the different assays, stock solutions of the extract were prepared in sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and then filtered through a 0.22 µm membrane. Subsequently, the concentrations of interest were prepared in the culture medium corresponding to each test.

4.3. Phytochemical Profiling of the Extract

HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS analyses were performed employing an Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a binary pump (model G1312B), an automatic injector (model G1367D), a degasser (model G1379B), and a photodiode array detector (model G1315C) registering the chromatograms at 230 nm and 330 nm. The system was coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer Bruker micrOTOF-QII (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) with an electrospray ionization source (ESI).

A Phenomenex Luna C18 column (150 mm × 2 mm, 3 μm particle size, 100 Å pore size), with a mobile phase of water: formic acid (98:2 v/v) (A) and methanol: formic acid (98:2 v/v) (B), a 0.2 mL/min flow rate and a 20 μL injection volume was used in the study. A multistep gradient was used, starting with 10% B at 0 min, 40% B at 2 min, 60% B at 10 min, 75% B at 12 min, 10% B at 12,4 min up to a total running time of 18 min. The ionization conditions were 200 °C and 3.5 kV for the capillary temperature and voltage, respectively. Nitrogen was employed as nebulizer gas, with a pressure of 3.5 bar, and as drying gas with a flow of 7.0 L/min. The mass scan range was 100–1000 m/z in negative mode. Data was acquired and processed with the Bruker Compass Data Analysis software V. 4.0. The assignment of the main components in the M. verticillata extract was achieved by comparison of their retention times and UV spectra with those of authentic standards and by comparison of their mass spectrum and fragmentation with literature.

4.4. Cell Lines and Culture Medium

HT-29 NF-κB reporter cell line (HT29-NF-κB-hrGFP) [41] were cultured in RPMI1640 (Life Technologies), HT-29 (ATCC HTB-38) and Caco-2 (ATCC HTB-37) cells were cultured in DMEM glutaMAX™ (Life Technologies, USA). Unless otherwise indicated, all culture media were supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Life Technologies). Cells were propagated in 25 or 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere to reach approximately 80% confluence. Afterwards, cells were trypsinized, their concentration was adjusted by manual cell counting with Neubauer chamber and were used for various experimental purposes. Less than twenty cell culture passages were made in all described assays.

4.5. Cytotoxicity Assay

Cytotoxicity was determined by the 3-(4,5-dimethyl- thiazole-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) colorimetric assay [71]. Briefly, 4 × 104 HT-29 cells or 3 × 104 Caco-2 cells per well were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After removing culture supernatants, Mv extract (0.01–10.00 mg/mL) in media supplemented with 10% FBS were added and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Then, the medium was changed and the cells were incubated with 0.1 mL MTT 0.5 mg/mL under normal culture conditions for 3 h. The resulting formazan precipitate was dissolved in DMSO:isopropanol (1:1, 100 µL per well) and measured at 570 nm with a microtiter plate reader to assess cell viability. Non-linear regression graphs were plotted and the 50% cytotoxic concentration (IC50) values were calculated. Every IC50 is the average of at least three independent determinations.

All assays were conducted using Mv concentrations that did not compromise cell line viability. To ensure the absence of toxicity, concentrations below the IC50 were employed.

4.6. Modulation of NF-κB Pathway

The modulation effect of the NF-κB pathway on HT29-NF-κB-hrGFP was analyzed [41]. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 3 × 104 cell/well and after 24 h, cells were preincubated for 3 hs with Mv at final concentrations of 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000, 2500 µg/mL. Each concentration was assayed in triplicate. Afterwards, TNF-α was added (concentration per well: 1 ng/mL), and cells were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. At the end of the incubation time, supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C for later IL-8 quantification. Cells were trypsinized and analyzed by flow cytometry to quantify NF-κB activation. Propidium Iodide (PI) was added to analyze cell viability. A BD Accuri™C6 (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) flow cytometer was used and BD Accuri™C6 software V1.0.264.21 was used for data acquisition. GFP and PI fluorescence emissions were detected using band-pass filters 533/30 and 585/40, respectively. For each sample, 10,000 counts gated on an FSC versus SSC dot plot, excluding doublets, were recorded. Only single living cells (cells that excluded PI) were considered. Cells without treatment and cells treated only with the stimulus or the different extracts were included in the assay but not for statistical analysis. BAY 11-7082 (10 μM) [38], an inhibitor of the translocation of the transcription factor to the nucleus, was used as a reference drug. Groups included: (i) Vehicle control (unstimulated cells), (ii) TNF-α control (positive control for NF-κB activation), (iii) Mv aqueous extract, and (iv) BAY 11-7082 (10 µM) as a reference drug for NF-κB inhibition. NF-κB activation was normalized by assigning the fluorescence values of the vehicle control as 0% response and those of the TNF-α control as 100% response. At least three independent experiments were performed.

4.7. IL-8 Production by LPS

HT-29 cells were cultured in 48-well plates with a seeding density of 6 × 104 cell/well and incubated for 24 hs. Cells were preincubated for 3 hs with M. verticillata at final concentrations of 250, 500, 1000 µg/mL. Cells were then activated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 24 h. At the end of the incubation time supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C until the IL-8 quantification was performed. At least three independent experiments were carried out. IL-8 was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Elisa Max™ Deluxe Set Human IL-8, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Absorbance was read at 450 and 570 nm within 15 min using a Multiskan FC microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). The absorbance at 570 nm was subtracted from the one at 450 nm. Each concentration was assayed in triplicate within one experiment, and at least three independent experiments were performed.

4.8. Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER)

Caco-2 cells were seeded in 12-well transwell plates (polycarbonate membrane with 0.4 µm pore size) at a concentration of 1 × 105 cell/well and incubated for 21 days to achieve cell polarization. The volume of medium maintained on both sides of the transwell was 500 µL and was renewed every 48 h. A TEER value of 200–300 Ω.cm2 was considered to prove intact Caco-2 monolayers with well-developed tight junctions.

Four groups were evaluated: normal (untreated control), Mv extract control, inflammatory cocktail (IC) control and IC with Mv extract (3 hs pretreatment). Each group was analyzed in triplicate per experiment. The concentration of Mv per well was 1750 µg/mL, selected based on preliminary MTT assays in Caco-2 cells and corresponding to one-quarter of the IC50, thus ensuring a strictly sub-toxic range and minimizing potential interference from cellular stress, as recommended for functional barrier assays [38]. Given that Caco-2 and HT-29 cells share similar responses to common inflammatory stimuli [40], the modulatory concentrations of the NF-κB signaling pathway identified in HT-29 cells was considered a valid reference for Caco-2 barrier assays. Membrane injury was induced in both chambers by IC which was composed of 50 ng/mL of each cytokine (IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1β) per well. TEER measurements were carried out before any treatment was made (basal) and 24 h after IC was added to the corresponding groups, according to a previous reported protocol [72] with minor modifications. Briefly, culture medium was aspirated and stored at −80 °C for further nitric oxide production measurement, then Caco-2 cell monolayers were rinsed with 500 µL of PBS. A volume of 0.7 mL of PBS was transferred to the apical side and 2.1 mL to the basolateral chamber. Using the MilliCell®-ERS volt-ohm meter (Merck Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) the resistance of an electrical current between electrodes was measured by immersing the electrode at a 90° angle, with the longer tip in the basolateral chamber and the other in the apical one. Caution was required to avoid touching the cell monolayer with the electrode. The resistance value from each well was corrected by the basal and multiplied by the insert membrane area, so that the results were expressed as Ω.cm2. Measurements were recorded at RT and three independent repetitions were made. Cells were manipulated in a biosafety hood to maintain sterility.

Upon completion of the test, both sides of the monolayers were washed three times with PBS before continuing with the assay described in the next section.

4.9. Fluorescein Isothiocyanate-Dextran (FITC-D) Assay

The Caco-2 polarized monolayers were employed for this experiment following a previously reported protocol [73] with minor modifications to measure the paracellular permeability. Following the three washes with sterile PBS, a volume of 200 µL of a 0.2 mg/mL FITC-D (4000 KDa MW, Sigma) solution prepared in DMEM glutaMAXTM culture medium without phenol red, was transferred to the apical side of each transwell. In the basolateral chamber, 800 µL of the same culture medium was added. Cells were incubated in a humidified incubator for 4 h. Time elapsed, and an aliquot of each transwell was taken from the basal side of each transwell. To make a blank reading, DMEM glutaMAXTM without phenol red was employed. Fluorescence was measured using a VarioskanTM Lux (SkanIt RE 5.0 software, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) fluorometer microplate reader, selecting 490 nm and 520 nm as excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively.

4.10. Nitric Oxide (NO) Production Measurement

NO production by nitric oxide synthases (NOS) activity was indirectly determined in the collected cultured Caco-2 (Section 4.8) media using the Griess reaction [74]. This reaction measures NO2- ion, a breakdown product of NO. A volume of 50 μL of supernatant was transferred to a 96-well plate, and the same quantity of Griess reagent was added. A calibration curve using NaNO2 was built. The reaction was carried out in the dark for 20 min at RT, and absorbance was measured at 562 nm using a Multiskan FC microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

4.11. Scratch Assay

HT-29 cell lines were tested through the scratch assay [75] to determine the capacity of these cells for wound closure through migration. Cells were seeded at a concentration of 6 × 105 cell/well into 12-well plates for 24 h incubation. The scratch wounds were made using a sterile 0.2 mL pipette tip. Cell monolayers were subsequently rinsed three times with PBS for debris removal, followed by incubation with Mv extract (100, 500, 10,000 µg/mL) in medium or fresh medium for 24 h. At least three independent determinations were made. The wound areas were photographed by an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) at 0 and 24 h. The effect of samples on wound closure was analyzed using ImageJ software, version 1.53t and the percentage in each group was calculated with respect to time zero. At least three independent experiments were carried out.

4.12. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using the Instant statistical package GraphPad Prism software, V. 5.04 [76] and R software, V. 3.5.1 [77]. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance of differences between groups was assessed by means of analysis of variance (one way ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test. For comparisons against a hypothetical value (100%), a one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied. p values of 0.05 were considered significant. Randomization and blinding of groups were conducted in all the experiments.

5. Conclusions

These findings offer an encouraging outlook for understanding the effects of the aqueous extract of Minthostachys verticillata on intestinal function and its potential therapeutic relevance. The extract showed a complex polyphenolic profile and exerted anti-inflammatory, barrier-protective, and anti-migratory effects in intestinal cell models, providing a mechanistic basis for its traditional gastrointestinal use. Furthermore, given the growing interest in functional foods, these results highlight its potential as a natural source of intestinal health-promoting agents and provide a basis for future research and product development. However, additional non-clinical and clinical studies will be necessary to confirm and expand the scope of these findings.

Author Contributions

A.G.R.-B.: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation; H.J.P.: methodology, conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft prep-aration; M.C.M.: formal analysis, writing-review and editing; K.P.: methodology, investigation, writing-review and editing; R.P.: methodology, investigation, writing-review and editing; H.B.: methodology, resources; S.B.G.: project administration, resources, funding acquisition, methodology, investigation, conceptualization, writing-review and editing; M.B.-F.: funding acquisition, methodology, conceptualization, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Universidad de Buenos Aires (Grant number: UBACyT 20020220200155BA) and FOCEM (MERCOSUR Structural Convergence Fund), COF 03/11. The acquisition of the BD Accuri™C6 (BD Bioscience, USA) flow cytometer was carried out with the funding of ANII (EQL_2013_X_1_2). MB-F and RP are members of the SNI (National Research System, Uruguay) and researchers of PEDECIBA.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors claim no conflict of interest with the publication of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADAM-17 | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 17 |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| BAY 11-7082 | NF-κB translocation inhibitor |

| Caco-2 | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ERK-1/2 | Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 beta |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| HT-29 | Human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line |

| HT29-NF-κB-hrGFP | Human epithelial NF-κB reporter cell line |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IBS | Inflammatory bowel syndrome |

| IC | Inflammatory cocktail (IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1β) |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IKK | Inhibitor of κB Kinase |

| IL-1β/8/12/23 | Interleukin-1β/8/12/23 |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase |

| MMP-2/9 | Matrix metalloproteinases-2/9 |

| Nrf-2 | Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| Mv | Minthostachys verticillata |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor pyrin domain 3 |

| NOD-2 | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| RAF | Rapidly Accelerated Fibrosarcoma quinase |

| RECK | Reversion-inducing Cysteine-rich Protein with Kazal Motifs |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TLR-4 | Toll–like receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TNFR | TNF-α receptor |

| VEGR-2 | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 |

| Wnt | Wingless/Integrated |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Effect of M. verticillata on the HT-29 reporter cell line: NF-κB activation (GFP fluorescence emissions) evaluated by flow cytometry. (A) Example of gating strategy: A total of 10,000 events in the singlet gate were recorded. FSC vs. SSC was used to exclude debris. Then, a singlet gate was used to exclude doublets and aggregates (FSC-A vs. FSC-H). A gate for live cells (propidium iodide (PI) negative) was used to exclude dead cells; then, GFP+ cells were determined. (B) Representative dot plots of GFP expression in live single cells without treatment, treated with Mv (1000 µg/mL), TNF-α, or Mv (1000 µg/mL) + TNF-α.

References

- Bischoff, S.C.; Barbara, G.; Buurman, W.; Ockhuizen, T.; Schulzke, J.D.; Serino, M.; Tilg, H.; Watson, A.; Wells, J.M. Intestinal permeability—A new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.J.; Zheng, L.; Campbell, E.L.; Saeedi, B.; Scholz, C.C.; Bayless, A.J.; Wilson, K.E.; Glover, L.E.; Kominsky, D.J.; Magnuson, A.; et al. Crosstalk between microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and intestinal epithelial HIF augments tissue barrier function. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, H. Increased Intestinal Permeability and Decreased Barrier Function: Does It Really Influence the Risk of Inflammation? Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2016, 1, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, J.J.; Seaby, E.G.; Beattie, R.M.; Ennis, S. NOD2 in Crohn’s Disease-Unfinished Business. J Crohn’s Colitis 2023, 17, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelli, M.; Franza, L.; Pignataro, G.; Ojetti, V.; Covino, M.; Piccioni, A.; Gasbarrini, A.; Franceschi, F. Interaction between Lipopolysaccharide and Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrad, J.E.; Lichtiger, S.; Yajnik, V. Inflammatory bowel disease and cancer: The role of inflammation, immunosuppression, and cancer treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 4794–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laredo, V.; García-Mateo, S.; Martínez-Domínguez, S.J.; López de la Cruz, J.; Gargallo-Puyuelo, C.J.; Gomollón, F. Risk of Cancer in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Keys for Patient Management. Cancers 2023, 15, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Dhawan, P.; Srivastava, A.S.; Singh, A.B. Inflammatory bowel disease: Therapeutic limitations and prospective of the stem cell therapy. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, G.J. Phenolic-enriched foods: Sources and processing for enhanced health benefits. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, S.; Del Bo’, C.; Marino, M.; Gargari, G.; Cherubini, A.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; Hidalgo-Liberona, N.; Peron, G.; González-Dominguez, R.; Kroon, P.; et al. Polyphenols and Intestinal Permeability: Rationale and Future Perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1816–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.; Desmarchelier, C. Plantas Medicinales Autóctonas de la Argentina. Bases Científicas para su Aplicación en Atención Primaria de Salud, 1st ed.; Corpus: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2015; pp. 495–498. [Google Scholar]

- Puentes, J.P.; Arenas, P.M.; Hurrell, A. Lamiaceae medicinales y aromáticas comercializadas en el Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Bonplandia 2020, 29, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Permanente Farmacopea Argentina. Peperina Mynthostachys. In Farmacopea Argentina, 6th ed.; Ministerio de Salud y Medio Ambiente: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1978; pp. 736–738. [Google Scholar]

- Cariddi, L.; Escobar, F.; Moser, M.; Panero, A.; Alaniz, F.; Zygadlo, J.; Sabini, L.; Maldonado, A. Monoterpenes isolated from Minthostachys verticillata (Griseb.) Epling essential oil modulates immediate-type hypersensitivity responses in vitro and in vivo. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 1687–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, F.M.; Sabini, M.C.; Cariddi, L.N.; Sabini, L.I.; Mañas, F.; Cristofolini, A.; Bagnis, G.; Gallucci, M.N.; Cavaglieri, L.R. Safety assessment of essential oil from Minthostachys verticillata (Griseb.) Epling (peperina): 90-days oral subchronic toxicity study in rats. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montironi, I.D.; Campra, N.A.; Arsaute, S.; Cecchini, M.E.; Raviolo, J.M.; Vanden Braber, N.; Barrios, B.; Montenegro, M.; Correa, S.; Grosso, M.C.; et al. Minthostachys verticillata Griseb (Epling.) (Lamiaceae) essential oil orally administered modulates gastrointestinal immunological and oxidative parameters in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 290, 115078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsaute, S.; Reinoso, E.B.; Cecchini, M.E.; Montironi, I.D.; Roma, D.A.; DÉramo, F.; Moressi, M.; Decara, L.; Macchiavelli, J.; Ariño, A.; et al. Effects of intramammary infusion of Minthostachys verticillata essential oil in cows at drying-off on microbiological and immunological parameters, and milk quality during the subsequent lactation. Vet. Res. Commun. 2025, 49, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, V.S.; Silvero C, M.J.; Bustos, P.S.; Luján, M.C.; Ortega, M.G.; Becerra, M.C. Silver nanoparticle disinfectant synthesized with aqueous extract of Minthostachys verticillata (Griseb.) Epling (Lamiaceae). Microb. Pathog. 2025, 208, 107990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Basso, A.; Carranza, A.; Zainutti, V.M.; Bach, H.; Gorzalczany, S.B. Pharmacological activity of peperina (Minthostachys verticillata) on gastrointestinal tract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 269, 113712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Miao, J.; Sun, W.; Huang, J.; Li, D.; Li, S.; Tong, L.; Sun, G. Simultaneous determination and pharmacokinetic study of four phenolic acids in rat plasma using UFLC–MS/MS after intravenous administration of salvianolic acid for injection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 134, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, L.; Dong, X.; Li, X.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, G. Rapid separation and identification of phenolic and diterpenoid constituents from Radix Salvia miltiorrhizae by high-performance liquid chromatography diode-array detection, electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry and electrospray ionization quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 21, 1855–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, I.; Russo, D.; Chiummiento, L.; Fernandez, E.; Choudhary, A.; Monné, M.; Milella, L.; Rai, D.K. Phytochemicals of Minthostachys diffusa Epling and their health-promoting bioactivities. Foods 2020, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Velamuri, R.; Fagan, J.; Schaefer, J. Full-spectrum analysis of bioactive compounds in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) as influenced by different extraction methods. Molecules 2020, 25, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, L.; Goya, L.; Lecumberri, E. LC/MS characterization of phenolic constituents of mate (Ilex paraguariensis, St. Hil.) and its antioxidant activity compared to commonly consumed beverages. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, M.N.; Knight, S.; Kuhnert, N. Discriminating between the six isomers of dicaffeoylquinic acid by LC-MSn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3821–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandradevan, M.; Simoh, S.; Mediani, A.; Ismail, N.H.; Ismail, I.S.; Abas, F. UHPLC-ESI-Orbitrap-MS analysis of biologically active extracts from Gynura procumbens (Lour.) Merr. and Cleome gynandra L. leaves. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 3238561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Dueñas, M.; Dias, M.I.; Sousa, M.J.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Ferreira, I.C. Phenolic profiles of cultivated, in vitro cultured and commercial samples of Melissa officinalis L. infusions. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, A.F.; Pereira, O.R.; Fernandes, Â.; Calhelha, R.C.; Silva, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C.; Cardoso, S.M. Phytochemical composition and bioactive effects of Salvia africana, Salvia officinalis ‘Icterina’ and Salvia mexicana aqueous extracts. Molecules 2019, 24, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Liang, Q.L.; Luo, G.A.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Jiang, Z.H. Multi-component HPLC fingerprinting of Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae and its LC-MS-MS identification. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 53, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghouti, M.; Martins-Gomes, C.; Schäfer, J.; Santos, J.A.; Bunzel, M.; Nunes, F.M.; Silva, A.M. Chemical characterization and bioactivity of extracts from Thymus mastichina: A Thymus with a distinct salvianolic acid composition. Antioxidants 2019, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kindl, M.; Bucar, F.; Jelić, D.; Brajša, K.; Blažeković, B.; Vladimir-Knežević, S. Comparative study of polyphenolic composition and anti-inflammatory activity of Thymus species. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, O.R.; Peres, A.M.; Silva, A.M.; Domingues, M.R.; Cardoso, S.M. Simultaneous characterization and quantification of phenolic compounds in Thymus x citriodorus using a validated HPLC–UV and ESI–MS combined method. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuengchamnong, N.; Krittasilp, K.; Ingkaninan, K. Characterisation of phenolic antioxidants in aqueous extract of Orthosiphon grandiflorus tea by LC–ESI-MS/MS coupled to DPPH assay. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegkas, A.; Milosević Ifantis, T.; Barda, C.; Samara, P.; Tsitsilonis, O.; Skaltsa, H. Antiproliferative activity of (−)-rabdosiin isolated from Ocimum sanctum L. Medicines 2019, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifan, A.; Wolfram, E.; Esslinger, N.; Grubelnik, A.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Minceva, M.; Luca, S.V. Globoidnan A, rabdosiin and globoidnan B as new phenolic markers in European-sourced comfrey (Symphytum officinale L.) root samples. Phytochem. Anal. 2021, 32, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, A.S.; Petersen, M. Production of caffeic, chlorogenic and rosmarinic acids in plants and suspension cultures of Glechoma hederacea. Phytochem. Lett. 2014, 10, cxi–cxvii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Rhee, M.H.; Kim, E.; Cho, J.Y. BAY 11-7082 is a broad-spectrum inhibitor with anti-inflammatory activity against multiple targets. Mediators Inflamm. 2012, 2012, 416036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nunzio, M.; Valli, V.; Tomás-Cobos, L.; Tomás-Chisbert, T.; Murgui-Bosch, L.; Danesi, F.; Bordoni, A. Is cytotoxicity a determinant of the different in vitro and in vivo effects of bioactives? BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panaro, M.A.; Carofiglio, V.; Acquafredda, A.; Cavallo, P.; Cianciulli, A. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol occur via inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-κB activation in Caco-2 and SW480 human colon cancer cells. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastropietro, G.; Tiscornia, I.; Perelmuter, K.; Astrada, S.; Bollati-Fogolín, M. HT-29 and Caco-2 reporter cell lines for functional studies of nuclear factor kappa B activation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 860534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cui, L.H.; Wang, X.H.; Yan, Z.H.; Li, C.; Gong, S.D.; Zheng, Y.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y. Modulation of inflammation by toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-kappa B in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guak, H.; Krawczyk, C.M. Implications of cellular metabolism for immune cell migration. Immunology 2020, 161, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhai, W.; Fan, M.; Wu, J.; Wang, C. Salvianolic Acid B Significantly Suppresses the Migration of Melanoma Cells via Direct Interaction with β-Actin. Molecules 2024, 29, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Hu, C.; Yang, B.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, Z. Salvianolic acid B targets mortalin and inhibits the migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma via the RECK/STAT3 pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, S.; Liu, D.; Tang, C.; Yang, W. Anticancer Effects of Salvianolic Acid A through Multiple Signaling Pathways (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 32, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Sghaier, M.; Pagano, A.; Mousslim, M.; Ammari, Y.; Kovacic, H.; Luis, J. Rutin Inhibits Proliferation, Attenuates Superoxide Production and Decreases Adhesion and Migration of Human Cancerous Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 1972–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.O.A.; Anwar, S.; Rahmani, A.H. The Potential Role of Rutin, a Flavonoid, in the Management of Cancer through Modulation of Cell Signaling Pathways. Open Life Sci. 2025, 20, 20251181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, A.; Maleki, N.; Bohlouli, S.; Kouhsoltani, M.; Sharifi, S.; Maleki Dizaj, S. Molecular Mechanisms of Anticancer Effect of Rutin. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 2500–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, J.; Quan, J.; Xiang, D. Rosmarinic Acid Inhibits Proliferation and Migration, Promotes Apoptosis and Enhances Cisplatin Sensitivity of Melanoma Cells through Inhibiting ADAM17/EGFR/AKT/GSK3β Axis. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 3065–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.H.; Kee, J.Y.; Hong, S.H. Rosmarinic Acid Activates AMPK to Inhibit Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, V.; Taine, E.G.; Meng, D.; Cui, T.; Tan, W. Chlorogenic Acid: A Systematic Review on the Biological Functions, Mechanistic Actions, and Therapeutic Potentials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Han, S.I.; Yun, J.H.; Kim, J.H. Quercetin 3-O-Glucoside Suppresses Epidermal Growth Factor-Induced Migration by Inhibiting EGFR Signaling in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Tumour Biol. 2015, 36, 9385–9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddy, P.G.; Dunlop, K.; Warford, J.; Samson, M.L.; Jones, Q.R.; Rupasinghe, H.V.; Robertson, G.S. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of the flavonoid-enriched fraction AF4 in a mouse model of hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivellini, A.; Lucchesini, M.; Maggini, R.; Mosadegh, H.; Villamarin, T.S.S.; Vernieri, P.; Mensuali-Sodi, A.; Pardossi, A. Lamiaceae phenols as multifaceted compounds: Bioactivity, industrial prospects and role of “positive-stress”. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 83, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.G.; Tran, P.T.; Lee, J.H.; Min, B.S.; Kim, J.A. Anti-inflammatory activity of caffeic acid derivatives isolated from the roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshamy, S.; Abdel Motaal, A.; Abdel-Halim, M.; Medhat, D.; Handoussa, H. Potential neuroprotective activity of Mentha longifolia L. in aluminum chloride-induced rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, X.; Wang, L.; Zhan, P.; He, W.; Tian, H.; Liu, J. Thyme (Thymus quinquecostatus Celak) Polyphenol-Rich Extract (TPE) Alleviates HFD-Induced Liver Injury in Mice by Inactivating the TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway through the Gut–Liver Axis. Foods 2023, 12, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; He, W.; Tian, H.; Zhan, P.; Liu, J. Thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) polyphenols ameliorate DSS-induced ulcerative colitis of mice by mitigating intestinal barrier damage, regulating gut microbiota, and suppressing TLR4/NF-κB-NLRP3 inflammasome pathways. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzaiene, N.N.; Jaziri, S.K.; Kovacic, H.; Chekir-Ghedira, L.; Ghedira, K.; Luis, J. The effects of caffeic, coumaric and ferulic acids on proliferation, superoxide production, adhesion and migration of human tumor cells in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 766, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, D.; Zieliński, H.; Laparra-Llopis, J.M.; Szawara-Nowak, D.; Honke, J.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A. Caffeic acid modulates processes associated with intestinal inflammation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Mo, Z. Inhibitory effects of salvianolic acid B on the high glucose-induced mesangial proliferation via NF-κB-dependent pathway. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.; Du, M.; Ding, J.; Liu, P. Salvianolic acid B attenuates the inflammatory response in atherosclerosis by regulating MAPKs/NF-κB signaling pathways in LDLR-/-mice and RAW264. 7 cells. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2022, 36, 03946320221079468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Shao, C.; Zhou, H.; Yu, L.; Bao, Y.; Mao, Q.; Yang, J.; Wan, H. Salvianolic acid B inhibits atherosclerosis and TNF-α-induced inflammation by regulating NF-κB/NLRP3 signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2023, 119, 155002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, R.; Singh, M.; Gautam, S.; Rawat, J.K.; Saraf, S.A.; Kaithwas, G. Rutin attenuates intestinal toxicity induced by Methotrexate linked with anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2016, 16, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.L.; Wei, J.; Bi, L.Q. Rutin attenuates oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokine level in adjuvant induced rheumatoid arthritis via inhibition of NF-κB. Pharmacology 2017, 100, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Kumar, A.; Singh, D.P.; Bishnoi, M.; Nag, T.C. Ameliorative potential of rutin in combination with nimesulide in STZ model of diabetic neuropathy: Targeting Nrf2/HO-1/NF-κB and COX signalling pathway. Inflammopharmacology 2018, 26, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, B.; Zhuang, S.; He, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, C. Effects of different levels of rutin on growth performance, immunity, intestinal barrier and antioxidant capacity of broilers. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 21, 1390–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhai, Y.; Zhou, W.; Qiao, Y.; Guan, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Peng, L. Intestinal Flora Mediates Antiobesity Effect of Rutin in High-Fat-Diet Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Permanente Farmacopea Argentina. 1050. Formas Farmacéuticas. In Farmacopea Argentina, 7th ed.; Ministerio de Salud de la Nación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2013; Volume 4, pp. 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, S.; Carreras, T.; Castro, R.; Perelmuter, K.; Giorgi, V.; Vila, A.; Rosales, A.; Pazos, M.; Moyna, G.; Carrera, I.; et al. A comparative study of supercritical fluid and ethanol extracts of cannabis inflorescences: Chemical profile and biological activity. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2022, 179, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, J.C.; Cho, J.; Bolling, B.W. Aronia berry inhibits disruption of Caco-2 intestinal barrier function. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 688, 108409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, D.; Rancan, S.; Orso, G.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Brun, P.; Giron, M.C.; Montopoli, M. Boswellia serrata Preserves Intestinal Epithelial Barrier from Oxidative and Inflammatory Damage. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.S.; Haj, F.G.; Lee, M.; Kang, I.; Zhang, G.; Lee, Y. Laminaria japonica Extract Enhances Intestinal Barrier Function by Altering Inflammatory Response and Tight Junction-Related Protein in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Caco-2 Cells. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiyamoorthy, J.; Sudhakarn, N. In vitro Cytotoxicity and Apoptotic Assay in HT-29 Cell Line Using Ficus hispida Linn: Leaves Extract. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2018, 13, S756–S761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GraphPad Prism, version 5.04 for Windows; GraphPad Software, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2025.

- R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.