Overexpression of a Xylem-Dominant Expressing BTB Gene, PtrBTB82, Influences Cambial Activity and SCW Synthesis in Populus trichocarpa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Characterization of PtrBTB Genes in P. trichocarpa

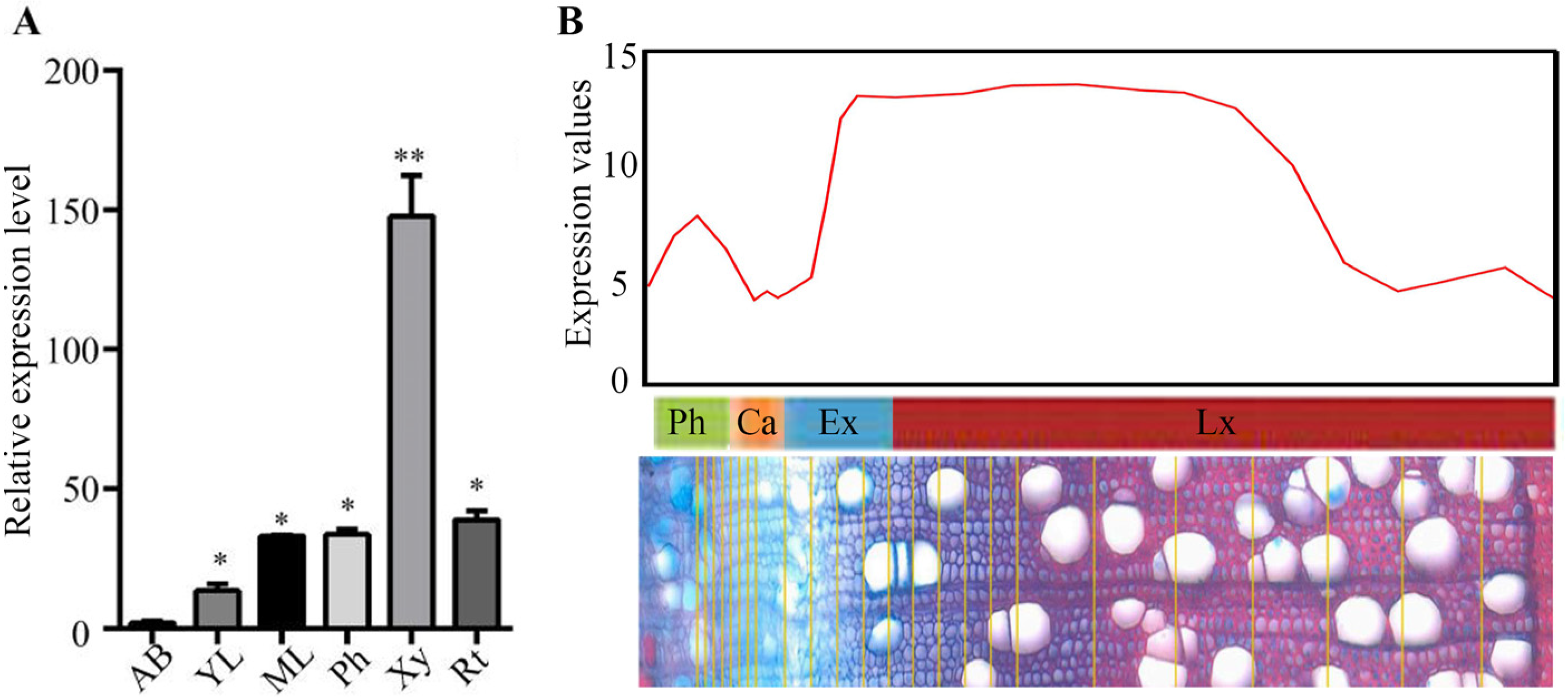

2.2. Promoter Activity of PtrBTB82 Gene in ProPtrBTB82::GUS Transgenic Populus

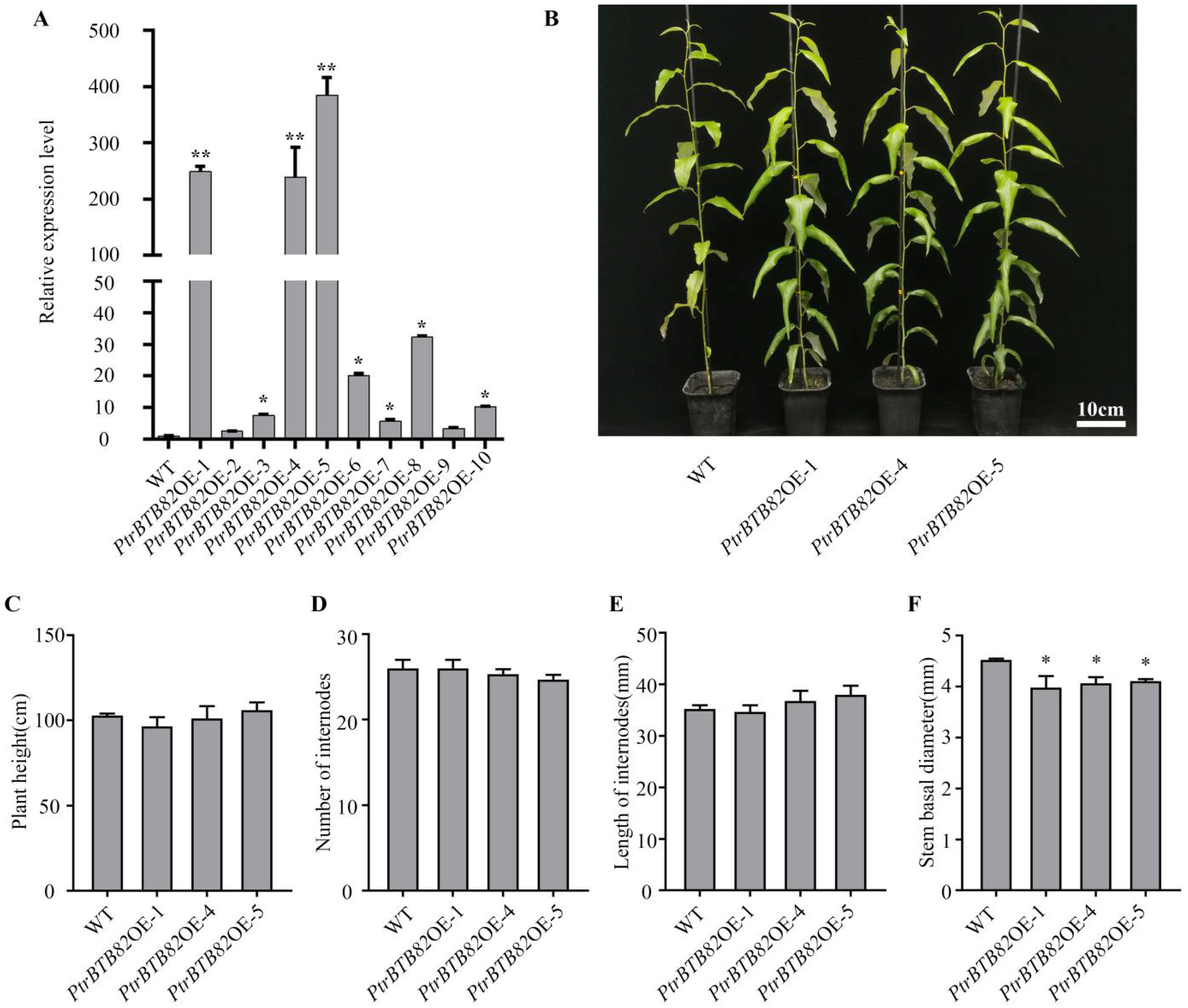

2.3. Phenotypes of PtrBTB82-Overexpressing P. trichocarpa

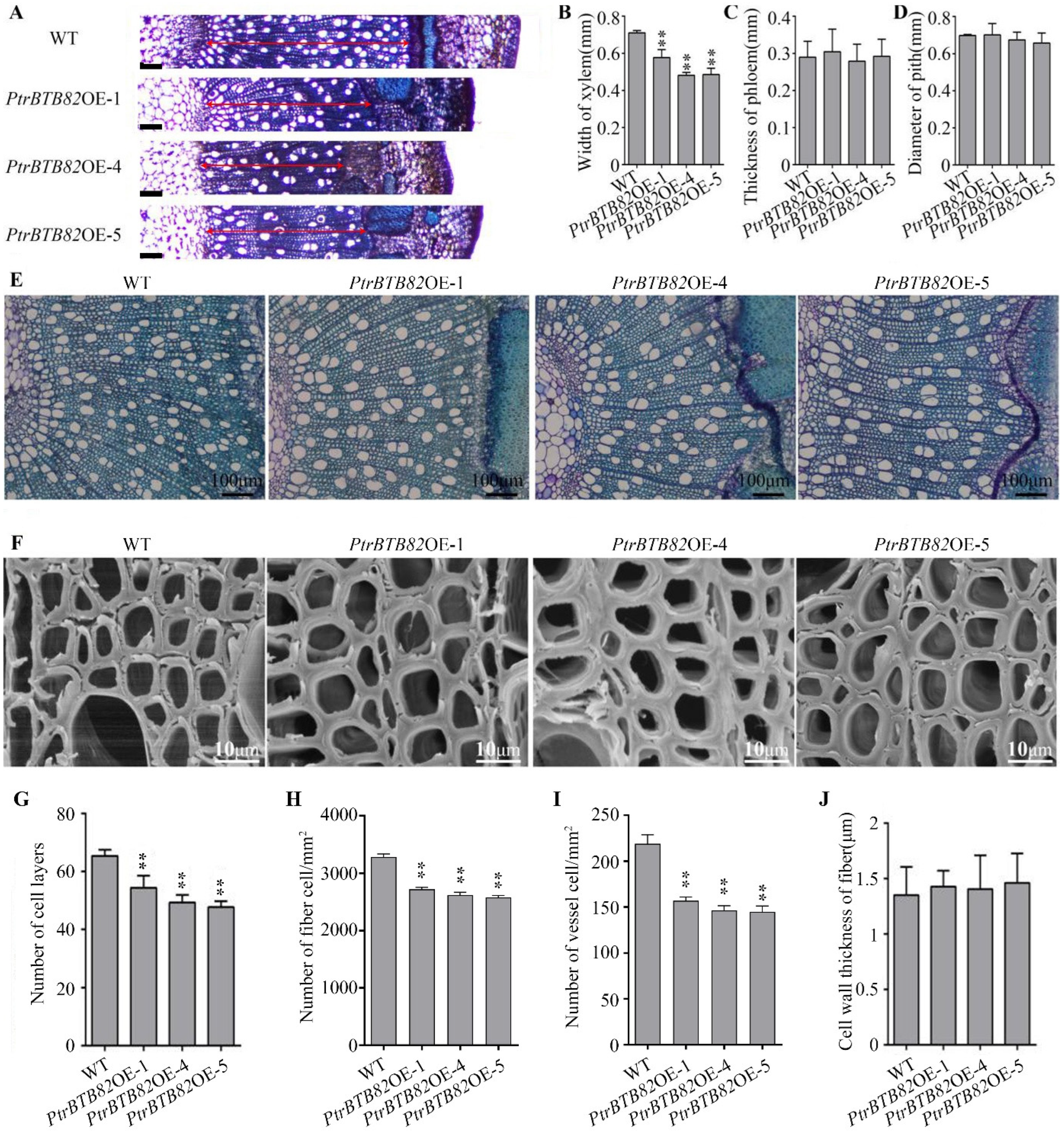

2.4. Overexpression of PtrBTB82 Decreases Xylem Width and Cambium Activity

2.5. Overexpression of PtrBTB82 Alters Wood Chemical Composition in Poplar

2.6. Expression of the Genes Associated with Cambium Activity in PtrBTB82-Overexpressing Poplars

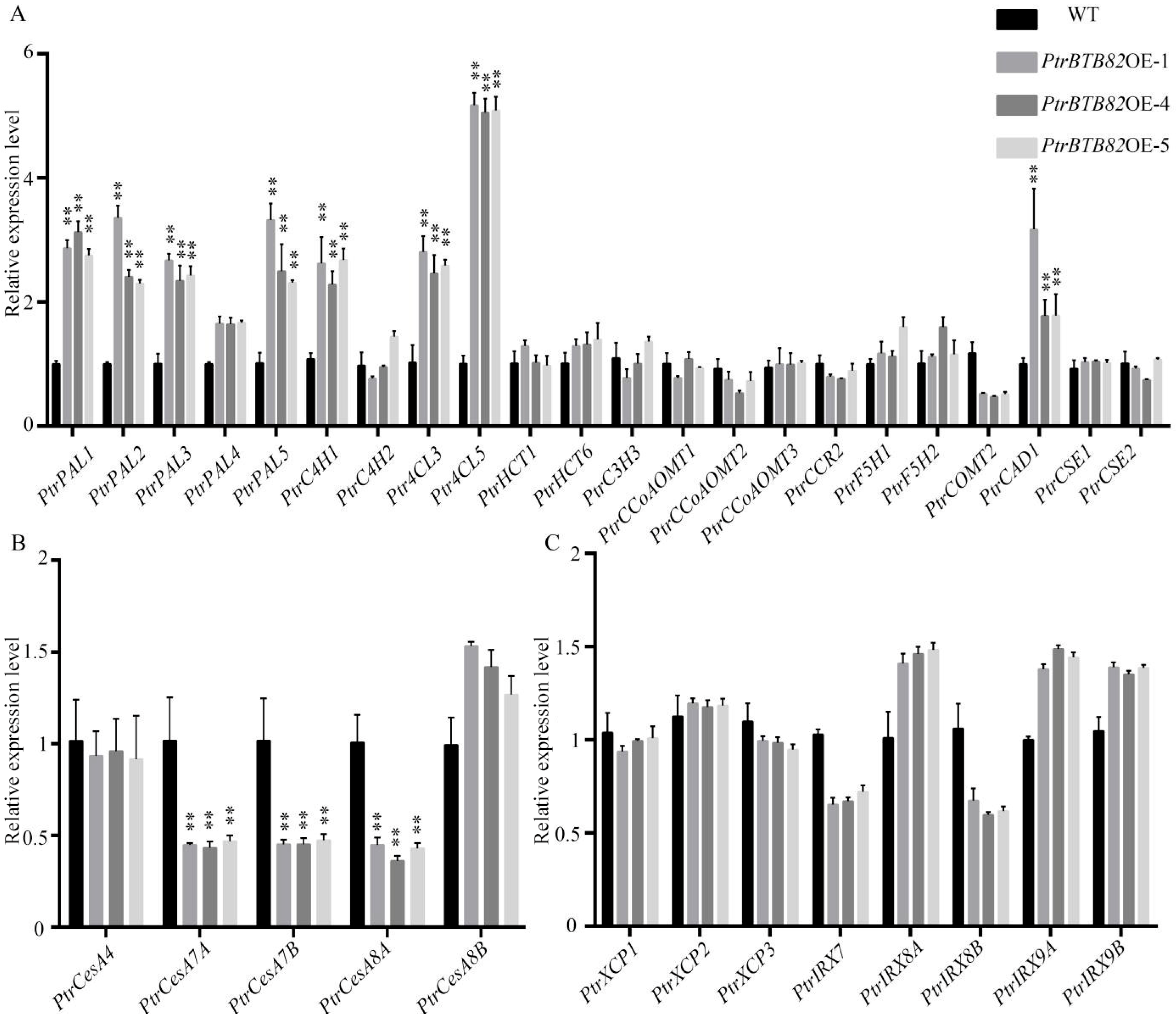

2.7. Expression of Lignin, Cellulose and Semi-Cellulose Synthesis Genes in PtrBTB82-Overexpressing Poplars

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Identification of the BTB Family Genes in P. trichocarpa

4.3. Construction of the BTB Family Phylogenetic Tree, Gene Structure and Motif Analysis

4.4. Analysis of Electronic Expression Data

4.5. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

4.6. Vector Constructs

4.7. Generation of Transgenic P. trichocarpa

4.8. GUS Staining

4.9. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

4.10. Histological Staining and Microscopy Analyses

4.11. Wood Composition Assay

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luo, L.; Li, L. Molecular understanding of wood formation in trees. For. Res. 2022, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Li, Q.; Lu, M.; Zhou, G.; Chai, G. Vascular cambium: The source of wood formation. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 700928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouwentak, C.A. Cambial activity as dependent on the presence of growth hormone and the non-resting condition of stems. Protoplasma 1941, 36, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.W. Auxin response factors. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1014–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Shen, Y.; He, F.; Fu, X.; Yu, H.; Lu, W.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Fan, D.; Wang, H.C. Auxin-mediated Aux/IAA-ARF-HB signaling cascade regulates secondary xylem development in Populus. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 752–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, C.L.; Schuetz, M.; Yu, Q.; Mattsson, J. Dynamics of MONOPTEROS and PIN-FORMED1 expression during leaf vein pattern formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007, 49, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto-Kitano, M.; Kusumoto, T.; Tarkowski, P.; Kinoshita-Tsujimura, K.; Václavíková, K.; Miyawaki, K.; Kakimoto, T. Cytokinins are central regulators of cambial activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 20027–20031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, S.; Antti, H.; Uddestrand, I.; Moritz, T.; Sundberg, B. Cross-talk between gibberellin and auxin in development of Populus wood: Gibberellin stimulates polar auxin transport and has a common transcriptome with auxin. Plant J. 2007, 52, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorce, C.; Giovannelli, A.; Sebastiani, L.; Anfodillo, T. Hormonal signals involved in the regulation of cambial activity, xylogenesis and vessel patterning in trees. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghighat, M.; Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.-H. WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX genes are crucial for normal vascular organization and wood formation in poplar. Plant Sci. 2024, 346, 112138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etchells, J.P.; Provost, C.M.; Mishra, L.; Turner, S.R. WOX4 and WOX14 act downstream of the PXY receptor kinase to regulate plant vascular proliferation independently of any role in vascular organisation. Development 2013, 140, 2224–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerville, C. Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006, 22, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Abid, M.; Xie, X.; Fu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Lin, H. Harnessing unconventional monomers to tailor lignin structures for lignocellulosic biomass valorization. For. Res. 2024, 4, e004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, W.S.; O’Neill, M.A. Biochemical control of xylan biosynthesis—Which end is up? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008, 11, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Lampugnani, E.R.; Picard, K.L.; Song, L.; Wu, A.-M.; Farion, I.M.; Zhao, J.; Ford, K.; Doblin, M.S.; Bacic, A. Asparagus IRX9, IRX10, and IRX14A are components of an active xylan backbone synthase complex that forms in the Golgi apparatus. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Cheng, H.; Zhu, S.; Cheng, J.; Ji, H.; Zhang, B.; Cao, S.; Wang, C.; Tong, G.; Zhen, C. Functional understanding of secondary cell wall cellulose synthases in Populus trichocarpa via the Cas9/gRNA-induced gene knockouts. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 1478–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, S.; Caffall, K.H.; Freshour, G.; Hilley, M.T.; Bauer, S.; Poindexter, P.; Hahn, M.G.; Mohnen, D.; Somerville, C. The Arabidopsis irregular xylem8 mutant is deficient in glucuronoxylan and homogalacturonan, which are essential for secondary cell wall integrity. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrett, O.M.; Dupree, P. Covalent interactions between lignin and hemicelluloses in plant secondary cell walls. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Ye, Z.-H. Secondary cell walls: Biosynthesis, patterned deposition and transcriptional regulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Gao, J.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Lin, Y.-C.J.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.P.; Chiang, V.L. MYB transcription factor161 mediates feedback regulation of secondary wall-associated NAC-Domain1 family genes for wood formation. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 1389–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; McCarthy, R.L.; Lee, C.; Ye, Z.-H. Dissection of the transcriptional program regulating secondary wall biosynthesis during wood formation in poplar. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 1452–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Yamaguchi, M.; Endo, H.; Rejab, N.A.; Ohtani, M. NAC-MYB-based transcriptional regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis in land plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 288. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.; Bhargava, A.; Qiang, W.; Friedmann, M.C.; Forneris, N.; Savidge, R.A.; Johnson, L.A.; Mansfield, S.D.; Ellis, B.E.; Douglas, C.J. The Class II KNOX gene KNAT7 negatively regulates secondary wall formation in Arabidopsis and is functionally conserved in Populus. New Phytol. 2012, 194, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Wang, C.; Sun, W.; Yan, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, B.; Guo, G.; Bi, C. OsWRKY12 negatively regulates the drought-stress tolerance and secondary cell wall biosynthesis by targeting different downstream transcription factor genes in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 212, 108794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gao, J.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Sulis, D.B.; Wang, J.P.; Chiang, V.L. Dimerization of PtrMYB074 and PtrWRKY19 mediates transcriptional activation of PtrbHLH186 for secondary xylem development in Populus trichocarpa. New phytol. 2022, 234, 918–933. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Yao, L.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Sang, Y.L.; Liu, L.-J. The transcription factor PagLBD4 represses cell differentiation and secondary cell wall biosynthesis in Populus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 214, 108924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaharbakhshi, E.; Jemc, J.C. Broad-complex, tramtrack, and bric-à-brac (BTB) proteins: Critical regulators of development. Genesis 2016, 54, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stogios, P.J.; Downs, G.S.; Jauhal, J.J.; Nandra, S.K.; Privé, G.G. Sequence and structural analysis of BTB domain proteins. Genome Biol. 2005, 6, R82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-Y.; Chen, R.-H. Cullin 3 ubiquitin ligases in cancer biology: Functions and therapeutic implications. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hepworth, S.R.; Zhang, Y.; McKim, S.; Li, X.; Haughn, G.W. BLADE-ON-PETIOLE–dependent signaling controls leaf and floral patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1434–1448. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.-F.; An, J.-P.; Liu, X.; Su, L.; You, C.-X.; Hao, Y.-J. The nitrate-responsive protein MdBT2 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by interacting with the MdMYB1 transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 890–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.P.; Zhang, X.W.; You, C.X.; Bi, S.Q.; Wang, X.F.; Hao, Y.J. MdWRKY40 promotes wounding-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in association with MdMYB1 and undergoes MdBT2-mediated degradation. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misra, A.; McKnight, T.D.; Mandadi, K.K. Bromodomain proteins GTE9 and GTE11 are essential for specific BT2-mediated sugar and ABA responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2018, 96, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandadi, K.K.; Misra, A.; Ren, S.; McKnight, T.D. BT2, a BTB protein, mediates multiple responses to nutrients, stresses, and hormones in Arabidopsis. Plant physiol. 2009, 150, 1930–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.L.; Zhu, B.Z.; Shao, Y.; Lin, X.J.; Wang, X.G.; Gao, H.Y.; Xie, Y.H.; Li, Y.C.; Luo, Y.B. Molecular cloning and characterization of ETHYLENE OVERPRODUCER 1-LIKE 1 gene, LeEOL1, from tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) fruit. DNA Seq. 2007, 18, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.-L.; Li, H.-L.; Qiao, Z.-W.; Zhang, J.-C.; Sun, W.-J.; Wang, C.-K.; Yang, K.; You, C.-X.; Hao, Y.-J. The BTB-TAZ protein MdBT2 negatively regulates the drought stress response by interacting with the transcription factor MdNAC143 in apple. Plant Sci. 2020, 301, 110689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škiljaica, A.; Lechner, E.; Jagić, M.; Majsec, K.; Malenica, N.; Genschik, P.; Bauer, N. The protein turnover of Arabidopsis BPM1 is involved in regulation of flowering time and abiotic stress response. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 102, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, N.; Škiljaica, A.; Malenica, N.; Razdorov, G.; Klasić, M.; Juranić, M.; Močibob, M.; Sprunck, S.; Dresselhaus, T.; Leljak Levanić, D. The MATH-BTB protein TaMAB2 accumulates in ubiquitin-containing foci and interacts with the translation initiation machinery in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigoyen, S.; Ramasamy, M.; Misra, A.; McKnight, T.D.; Mandadi, K.K. A BTB-TAZ protein is required for gene activation by Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S multimerized enhancers. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Pedmale, U.V.; Morrow, J.; Sachdev, S.; Lechner, E.; Tang, X.; Zheng, N.; Hannink, M.; Genschik, P.; Liscum, E. Modulation of phototropic responsiveness in Arabidopsis through ubiquitination of phototropin 1 by the CUL3-Ring E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL3NPH3. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3627–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Pan, Y.; Su, C.; Zhang, X. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the BTB domain-containing protein gene family in tomato. Genes Genom. 2018, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalmani, A.; Huang, Y.-B.; Chen, Y.-B.; Muhammad, I.; Li, B.-B.; Ullah, U.; Jing, X.-Q.; Bhanbhro, N.; Liu, W.-T.; Li, W.-Q. The highly interactive BTB domain targeting other functional domains to diversify the function of BTB proteins in rice growth and development. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 1311–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, H.; Bernhardt, A.; Dieterle, M.; Hano, P.; Mutlu, A.; Estelle, M.; Genschik, P.; Hellmann, H. Arabidopsis AtCUL3a and AtCUL3b form complexes with members of the BTB/POZ-MATH protein family. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.; Dai, X.; Li, Q.; Wei, M. Genome-wide characterization of the BTB gene family in poplar and expression analysis in response to hormones and biotic/abiotic stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, R.; Liu, X.; Li, R.; Du, L. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of the BTB domain-containing protein gene family in poplar. Biochem. Genet. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Song, D.; Zhang, R.; Luo, L.; Cao, S.; Huang, C.; Sun, J.; Gui, J.; Li, L. A xylem-produced peptide PtrCLE20 inhibits vascular cambium activity in Populus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; He, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, L. Two MADS-box genes regulate vascular cambium activity and secondary growth by modulating auxin homeostasis in Populus. Plant Commun. 2021, 2, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhai, R.; Lin, J.; Wang, Z.; Meng, D.; Li, M.; Mao, Y.; Gao, B.; Ma, H.; Zhang, B. Cell-type-specific PtrWOX4a and PtrVCS2 form a regulatory nexus with a histone modification system for stem cambium development in Populus trichocarpa. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Lu, M.; Zhuang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Kong, Y.; Chai, G. Dual regulation of xylem formation by an auxin-mediated PaC3H17-PaMYB199 module in Populus. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1545–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.X.; Guo, W.; Song, X.Q.; Liu, Y.L.; Xue, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, J.J.; Lu, M.Z.; Zhao, S.T. PagJAZ5 regulates cambium activity through coordinately modulating cytokinin concentration and signaling in poplar. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 1455–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, Y.; Guo, Y.; Shou, H.; Du, J. PagDET2 promotes cambium cell division and xylem differentiation in poplar stem. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 923530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, L.; Zheng, L. Lignins: Biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-W.; Guan, S.; Burlingame, A.L.; Wang, Z.-Y. The CDG1 kinase mediates brassinosteroid signal transduction from BRI1 receptor kinase to BSU1 phosphatase and GSK3-like kinase BIN2. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Nam, K.H. Regulation of brassinosteroid signaling by a GSK3/SHAGGY-like kinase. Science 2002, 295, 1299–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Cho, H.; Noh, J.; Qi, J.; Jung, H.-J.; Nam, H.; Lee, S.; Hwang, D.; Greb, T.; Hwang, I. BIL1-mediated MP phosphorylation integrates PXY and cytokinin signalling in secondary growth. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucukoglu, M.; Nilsson, J.; Zheng, B.; Chaabouni, S.; Nilsson, O. WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX 4 (WOX 4)-like genes regulate cambial cell division activity and secondary growth in Populus trees. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Kondo, Y.; Fukuda, H. TDIF peptide signaling regulates vascular stem cell proliferation via the WOX4 homeobox gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2618–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Z.D.; Peralta, P.N.; Mitchell, P.; Chiang, V.L.; Kelley, S.S.; Edmunds, C.W.; Peszlen, I.M. Anatomy and chemistry of Populus trichocarpa with genetically modified lignin content. BioResources 2019, 14, 5729–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Murata, K.; Yamazaki, M.; Onosato, K.; Miyao, A.; Hirochika, H. Three distinct rice cellulose synthase catalytic subunit genes required for cellulose synthesis in the secondary wall. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Li, L.; Sun, Y.-H.; Chiang, V.L. The cellulose synthase gene superfamily and biochemical functions of xylem-specific cellulose synthase-like genes in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, R.; Morrison, W.H., III; Freshour, G.D.; Hahn, M.G.; Ye, Z.-H. Expression of a mutant form of cellulose synthase AtCesA7 causes dominant negative effect on cellulose biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, S.R.; Somerville, C.R. Collapsed xylem phenotype of Arabidopsis identifies mutants deficient in cellulose deposition in the secondary cell wall. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 689–701. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, P.; Pfaff, S.A.; Zhao, W.; Debnath, D.; Vojvodin, C.S.; Liu, C.J.; Cosgrove, D.J.; Wang, T. Emergence of lignin-carbohydrate interactions during plant stem maturation visualized by solid-state NMR. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 8010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhen, C.; Xu, W.; Wang, C.; Cheng, Y. Simple, rapid and efficient transformation of genotype Nisqually-1: A basic tool for the first sequenced model tree. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedasyam, A.; Plott, C.; Hossain, M.S.; Lovell, J.T.; Grimwood, J.; Jenkins, J.W.; Daum, C.; Barry, K.; Carlson, J.; Shu, S. JGI Plant Gene Atlas: An updateable transcriptome resource to improve functional gene descriptions across the plant kingdom. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 8383–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundell, D.; Street, N.R.; Kumar, M.; Mellerowicz, E.J.; Kucukoglu, M.; Johnsson, C.; Kumar, V.; Mannapperuma, C.; Delhomme, N.; Nilsson, O. AspWood: High-spatial-resolution transcriptome profiles reveal uncharacterized modularity of wood formation in Populus tremula. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1585–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.E.; Martin, T.M.; Pauly, M. Comprehensive compositional analysis of plant cell walls (lignocellulosic biomass) part I: Lignin. J. Vis. Exp. 2010, 37, 1745. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, C.E.; Martin, T.M.; Pauly, M. Comprehensive compositional analysis of plant cell walls (lignocellulosic biomass) part II: Carbohydrates. J. Vis. Exp. 2010, 37, 1837. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, S.; Yao, H.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Li, C.; Cheng, Y. Overexpression of a Xylem-Dominant Expressing BTB Gene, PtrBTB82, Influences Cambial Activity and SCW Synthesis in Populus trichocarpa. Plants 2026, 15, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010068

Zhu S, Yao H, Liu J, Zhao X, Cheng J, Wang C, Xu W, Li C, Cheng Y. Overexpression of a Xylem-Dominant Expressing BTB Gene, PtrBTB82, Influences Cambial Activity and SCW Synthesis in Populus trichocarpa. Plants. 2026; 15(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Siran, Hongtao Yao, Jiayi Liu, Xiao Zhao, Jiyao Cheng, Chong Wang, Wenjing Xu, Chunming Li, and Yuxiang Cheng. 2026. "Overexpression of a Xylem-Dominant Expressing BTB Gene, PtrBTB82, Influences Cambial Activity and SCW Synthesis in Populus trichocarpa" Plants 15, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010068

APA StyleZhu, S., Yao, H., Liu, J., Zhao, X., Cheng, J., Wang, C., Xu, W., Li, C., & Cheng, Y. (2026). Overexpression of a Xylem-Dominant Expressing BTB Gene, PtrBTB82, Influences Cambial Activity and SCW Synthesis in Populus trichocarpa. Plants, 15(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010068